The desire for routine cardiac stress testing in asymptomatic kidney transplant candidates is strong. Cardiovascular causes remain the leading cause of death for kidney failure patients due to traditional and kidney-specific risk factors. The burden of asymptomatic coronary artery disease (CAD) in this high-risk cohort is excessive, with reported prevalence between 37% and 53% for at least one coronary artery to have a minimum 50% stenosis (1), and post-transplant immunosuppression has cardiometabolic side effects. Therefore, advocates for routine cardiac stress testing pretransplantation justify the strategy by claiming it can: (1) improve counseling and the decision-making process for patients and professionals, (2) facilitate intervention on asymptomatic lesions to reduce risk of peri- or postoperative harm, and/or (3) exclude very high-risk candidates from transplantation surgery to prevent wastage of a valuable resource due to early mortality risk. However, arguments have challenged these assertions (2), and the subsequent publication of ISCHEMIA-CKD provides further validation to support a laissez-faire approach.

ISCHEMIA-CKD is a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) that enrolled 777 patients with advanced kidney disease (defined as an eGFR of <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or receipt of dialysis) and moderate or severe myocardial ischemia (3). After a median follow-up of 2.2 years, the investigators did not find any evidence that an initial invasive strategy compared with an initial conservative strategy reduced the risk of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction or angina-related health status. However, the invasive strategy was associated with higher incidence of stroke and higher incidence of death or initiation of dialysis compared with the conservative strategy.

Combining ISCHEMIA-CKD with other revascularization RCTs, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis pooled empirical data from 14 studies that included 14,877 patients with 64,678 patient-years of follow-up (4). The principal findings of this review demonstrated routine revascularization was not associated with improved survival but rather with reduced risk of nonprocedural myocardial infarction, unstable angina, and greater freedom from angina at the expense of higher rates of procedural myocardial infarction. Data for coronary intervention after kidney transplantation are limited but appear safe in small case series (5).

ISCHEMIA-CKD is a landmark study for kidney patients, but its publication has not satisfied cardiac test enthusiasts, and the trial data have been probed and dissected vociferously to find crumbs of contention. Some critics argue the trial population was low risk (surprising considering observed 3-year event rates were 36.4% and 36.7% per arms) and highly selective (approximately two recruits per center per year), whereas others highlight differential effect sizes observed for study participants with severe ischemia favoring invasive intervention. Only 13% of study participants were on a kidney transplant waiting list, and this is a legitimate critique, although the trial was not designed to address this particular question. However, there are other interesting observations buried within ISCHEMIA-CKD. Half of study participants randomized to the invasive strategy group did not undergo revascularization, most frequently because they did not have obstructive CAD despite positive stress tests. ISCHEMIA-CKD has successfully provided clarity about the failure of invasive strategies for people with advanced CKD or kidney failure with asymptomatic CAD and the failure of noninvasive stress test characteristics as a screening tool to facilitate those ineffective interventions. Others have determined an antithetical conclusion from ISCHEMIA-CKD and other relevant RCTs (see Table 1), which reflects the dogmatism many clinicians have on this issue.

Table 1.

Published studies of coronary intervention in kidney disease/failure patients

| Study | Number (CKD/Overall) | CKD Definition | Cardiac Risk at Baseline | Primary End Point | Stress Test | Intervention | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangalore (2020) (3) | 777/777 | eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or kidney failure (53%) | Moderate or severe ischemia defined by site investigators using trial-defined criteria | Composite of all-cause mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction | Site dependent (nuclear imaging, stress echo, cardiac MRI, or exercise test) | Coronary angiogram within 30-days of randomization with PCI or CABG as indicated | No benefit, some harm |

| Frye (2009) (16) | 443/2368 | eGFR between 30 and 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | Coronary artery disease defined by angiography (≥50% stenosis of a major epicardial coronary artery+positive stress test or ≥70% stenosis of a major epicardial coronary artery+classic angina) | All-cause mortality | None | PCI or CABG within 4 weeks of randomization as clinically indicated | No benefit |

| Boden (2007) (17) | 320/2287 | eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (only 16 had eGFR <30) | Coronary artery stenosis of at least 70% in at least one proximal epicardial coronary artery and objective evidence of myocardial ischemia or at least one coronary stenosis of at least 80% and classic angina without provocative testing | Composite of all-cause mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction | Ischemic changes on EKG or inducible ischemia on exercise or pharmacologic vasodilator stress | Target lesion PCI attempted, and complete revascularization performed if clinically appropriate | No benefit |

| Manske (1999) (18) | 26/26 | CKD stage 5 or kidney failure on dialysis (27%) | Coronary artery stenosis ≥75% in one or more coronary arteries, atypical or no chest pain, and left ventricular ejection fraction >35% | Composite of unstable angina, myocardial infarction or cardiovascular-related death | Gated-blood-pool radionuclide scan | PCI or CABG as clinically indicated | Benefit |

PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; EKG, electrocardiogram.

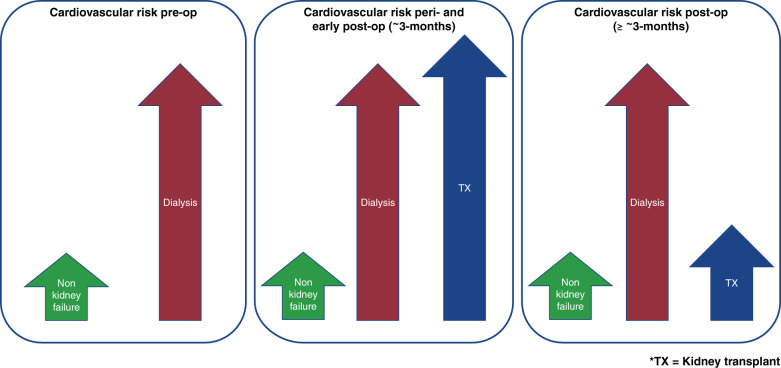

The fundamental question is what is in the best interest of kidney failure patients? For most people with kidney failure, in the absence of major contraindications and regardless of baseline demographics, kidney transplantation is the best form of therapy because it lowers all-cause and cardiovascular mortality compared with treatment options such as dialysis (6). Impaired kidney function is a strong independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (7), and a spectrum of disorders with overlapping cardiovascular and kidney disease are associated with impaired kidney function. Experimental evidence suggests hemodialysis leads to transient declines in both cerebral blood flow (which correlates with interdialytic cognitive dysfunction) (8) and renal blood flow (which correlates with myocardial injury) (9). If intradialytic circulatory stress is associated with reduced perfusion in multiple vulnerable organs, then dialysis is clearly a modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Removing the need for dialysis with a working kidney transplant abrogates this risk and contributes to survival benefits (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dynamic risk of major adverse cardiovascular events for kidney failure patients versus the general population before, during, and after kidney transplant surgery.

The clinical challenge is translating population-level evidence to high-risk individuals for personalized decision making. Although kidney transplantation is the best form of therapy for many kidney failure patients, some are more likely to suffer harm than receive benefit. However, determination of eligibility can lack objectivity and be maligned by perception bias. Although decision making is easy in the presence of absolute or relative contraindications, subjective discernments that negatively influence decision making are harder to overcome. Doctrinaire views of cardiovascular risk impede access to kidney transplantation, and subjective assessments are inferior to objective tools. For example, subjective appraisal of functional capacity before noncardiac surgery has poor sensitivity or predictive capacity for death or myocardial infarction within 30 days of surgery (10). In contrast, the Duke Activity Status Index, a standardized questionnaire correlated with gold-standard measures of functional capacity, demonstrates significant adjusted associations with a primary outcome of death or myocardial infarction by 30 days post surgery in the same study (10). The caveat is that the Duke Activity Status Index has not been validated in the context of kidney transplantation, and exercise tolerance declines with advancing renal dysfunction, which limits interpretation of functional ability.

Arguments can be passionately construed both for and against cardiac screening in asymptomatic kidney transplant candidates, but for many, there is significant confusion about the ultimate objective with cardiac testing. Many clinicians cite regulatory pressures rather than perceived patient benefit for their incongruous practice (11). Advocates of cardiac testing argue symptoms of significant CAD are masked by poor exercise tolerance that could manifest after the stress of kidney transplant surgery, exacerbated in the context of primary nonfunction or delayed graft function. However, recent epidemiologic analyses using propensity-scored cohorts suggest cardiac screening does not predict major adverse cardiovascular events after kidney transplantation (12). This clinical equipoise should set the stage for an RCT purposefully designed and adequately powered to determine whether cardiac screening asymptomatic kidney transplant candidates has any clinical benefit. However, logistical challenges and methodologic constraints make this an incredibly challenging study to design and/or execute, with considerable costs and numbers required for adequate statistical power. Even if viable in theory, the biggest obstacle in practice will be selection bias. Persuading apprehensive clinicians to recruit kidney failure patients reflective of real-world cohorts will be a significant challenge. This bias has been demonstrated in clinical trials recruiting kidney failure patients, with participants in multicenter dialysis studies shown to be younger, less comorbid, and with lower mortality rates compared with real-world cohorts (13). Therefore, prejudiced enrolment skewed toward lower-risk candidates will diminish any trial outcome and fail to win over skeptics. Ambitious studies such as CARSK (http://www.carsk.org) are welcomed and may shed light on the utility of surveillance cardiac testing after joining the waiting list, but the key obstacle for high-risk candidates is joining the waiting list in the first place.

The aim of doing something underlies the purpose for which we do it or the result that we intend to achieve. As we debate the purpose of cardiac stress testing asymptomatic kidney transplant candidates, we must remind ourselves what aim we are striving to achieve. If our aim is to optimize outcomes for people receiving kidney transplants, then this timorous attitude will restrict access to transplantation. However, if our aim is to optimize outcomes for people living with kidney failure, then this bold attitude will broaden access to transplantation. On the balance of probabilities, more kidney transplant candidates will benefit than come to harm with a laissez-faire approach to cardiac testing. To be clear, this is not a recommendation for reckless behavior and cavalier transplant activity. Suitability for kidney transplant surgery is important but must be fit for purpose. Assessing, validating, and incorporating objective measures to assess fitness for transplant surgery, tailored to a kidney failure cohort, must override subjective bias.

For high-risk cardiometabolic kidney transplant candidates, communication of the risks and benefits of kidney transplantation versus the alternative therapy option of dialysis must acknowledge probabilities and uncertainties. Improved risk communication is essential but requires a supportive regulatory environment where calculated risk is embraced to avoid cautious risk aversion (14). Although post-transplant outcomes may be affected by increased risk from kidney transplant candidates with significant cardiometabolic burden, we are ignoring the risk for these high-risk individuals who are denied access to kidney transplantation. As highlighted in a recent perspective, “we perceive greater risk in acts of commission than in acts of omission; if a patient dies during or after transplantation, it’s the doctor’s responsibility; if the patient dies from organ failure while awaiting a transplant, we can blame the indifference of the universe” (15). The simple truth is the best treatment for most kidney failure patients with asymptomatic CAD is transplantation, regardless of underlying risk factor characteristics and/or duration. Obstacles to that goal that are based on dogma rather than evidence, such as cardiac testing in the absence of significant symptoms, should therefore be abolished.

Disclosures

A. Sharif reports consultancy agreements with Hansa Pharamaceuticals; research funding from Chiesi Pharmaceuticals; honoraria from Chiesi Pharamaceuticals and Napp Pharmaceuticals; has attended advisory board meetings for Atara Biotheraputics, Boeringher Ingelheim/Lilly Alliance, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals; and received speakers’ fees for meetings/symposia hosted by Astellas, Chiesi, and Novartis.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

The content of this article reflects the personal experience and views of the author(s) and should not be considered medical advice or recommendation. The content does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or Kidney360. Responsibility for the information and views expressed herein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

See related debate, “Routine Cardiac Stress Testing in Potential Kidney Transplant Candidates Is Only Appropriate in Symptomatic Individuals: CON,” and commentary, “Routine Cardiac Stress Testing in Potential Kidney Transplant Candidates Is Only Appropriate in Symptomatic Individuals: COMMENTARY,” on pages 2013–2016 and 2017–2018, respectively.

Author Contributions

A. Sharif was responsible for conceptualization, wrote the original draft of the manuscript, and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hart A, Weir MR, Kasiske BL: Cardiovascular risk assessment in kidney transplantation. Kidney Int 87: 527–534, 2015. 10.1038/ki.2014.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharif A: The argument for abolishing cardiac screening of asymptomatic kidney transplant candidates. Am J Kidney Dis 75: 946–954, 2020. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bangalore S, Maron DJ, O’Brien SM, Fleg JL, Kretov EI, Briguori C, Kaul U, Reynolds HR, Mazurek T, Sidhu MS, Berger JS, Mathew RO, Bockeria O, Broderick S, Pracon R, Herzog CA, Huang Z, Stone GW, Boden WE, Newman JD, Ali ZA, Mark DB, Spertus JA, Alexander KP, Chaitman BR, Chertow GM, Hochman JS; ISCHEMIA-CKD Research Group : Management of coronary disease in patients with advanced kidney disease. N Engl J Med 382: 1608–1618, 2020. 10.1056/NEJMoa1915925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangalore S, Maron DJ, Stone GW, Hochman JS: Routine revascularization versus initial medical therapy for stable ischemic heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Circulation 142: 841–857, 2020. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paizis IA, Mantzouratou PD, Tzanis GS, Melexopoulou CA, Darema MN, Boletis JN, Barbetseas JD: Coronary artery disease in renal transplant recipients: An angiographic study. Hellenic J Cardiol 61: 199–203, 2020. 10.1016/j.hjc.2018.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK: Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med 341: 1725–1730, 1999. 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, Gansevoort RT; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: A collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375: 2073–2081, 2010. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Findlay MD, Dawson J, Dickie DA, Forbes KP, McGlynn D, Quinn T, Mark PB: Investigating the relationship between cerebral blood flow and cognitive function in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 147–158, 2019. 10.1681/ASN.2018050462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marants R, Qirjazi E, Grant CJ, Lee TY, McIntyre CW: Renal perfusion during hemodialysis: Intradialytic blood flow decline and effects of dialysate cooling. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 1086–1095, 2019. 10.1681/ASN.2018121194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wijeysundera DN, Pearse RM, Shulman MA, Abbott TEF, Torres E, Ambosta A, Croal BL, Granton JT, Thorpe KE, Grocott MPW, Farrington C, Myles PS, Cuthbertson BH; METS Study Investigators : Assessment of functional capacity before major non-cardiac surgery: An international, prospective cohort study. Lancet 391: 2631–2640, 2018. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31131-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng XS, Mathew RO, Parasuraman R, Tantisattamo E, Levea SL, Kapoor R, Dadhania DM, Rangaswami J: Coronary Artery Disease Screening of Asymptomatic Kidney Transplant Candidates: A Web-Based Survey of Practice Patterns in the United States. Kidney Med 2: 505–507, 2020. 10.1016/j.xkme.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nimmo A, Forsyth J, Oniscu G, Robb M, Watson C, Fotheringham J, Roderick PJ, Ravanan R, Taylor DM: A propensity score matched analysis indicates screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease does not predict cardiac events in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int 99: 431–442, 2021. 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smyth B, Haber A, Trongtrakul K, Hawley C, Perkovic V, Woodward M, Jardine M: Representativeness of randomized clinical trial cohorts in end-stage kidney disease: A meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 179: 1316–1324, 2019. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharif A, Montgomery RA: Regulating the risk-reward trade-off in transplantation. Am J Transplant 20: 2282–2283, 2020. 10.1111/ajt.15882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montgomery RA: Getting comfortable with risk. N Engl J Med 381: 1606–1607, 2019. 10.1056/NEJMp1906872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frye RL, August P, Brooks MM, Hardison RM, Kelsey SF, MacGregor JM, Orchard TJ, Chaitman BR, Genuth SM, Goldberg SH, Hlatky MA, Jones TLZ, Molitch ME, Nesto RW, Sako EY, Sobel BE; The Bari 2D Study Group : A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 360: 2503–2515, 2009. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, Knudtson M, Dada M, Casperson P, Harris CL, Chaitman BR, Shaw L, Gosselin G, Nawaz S, Title LM, Gau G, Blaustein AS, Booth DC, Bates ER, Spertus JA, Berman DS, Mancini GBJ, Weintraub WS; COURAGE Trial Research Group: Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 356: 1503–1516, 2007. 10.1056/NEJMoa070829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manske CL, Wang Y, Rector T, Wilson RF, White CW: Coronary revascularisation in insulin-dependent diabetic patients with chronic renal failure. Lancet 340: 998–1002, 1992. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93010-k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]