Abstract

Background:

Dental caries is the most common oral disease of mankind; however, there are limited data on the oral status of adolescents in northern Nigeria. Recently, the World Health Organization set the global caries goal as significant caries (SiC) index score of <3. This study was designed to appraise the magnitude of the disease among adolescents in northern Nigeria.

Objectives:

The objective of the study was to determine the prevalence, pattern, and severity of caries among 10–12-year-old adolescents in Kano, Nigeria.

Materials and Methods:

Six hundred and ninety-four school-aged children were selected through a multi-stage sampling of 10–12-year-old children in Kano and examined for dental caries using the WHO protocols. Data analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 20 Inc. Chicago IL, USA).

Results:

The prevalence of caries was 22.9% with mean DMFT and SiC scores of 0.5 (±1.2) and 3.7 respectively. DMFT >0 ranged from 1 to 8. Tooth 85 (the right mandibular second primary molar) and tooth 36 (left mandibular permanent first molar) had the highest caries count for primary and permanent teeth respectively. More lesions occurred on the left mandible in primary and permanent teeth. The second primary molars and the first permanent molars were most affected by the disease.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of dental caries was low among male adolescents in Kano as evidenced by the low mean DMFT/dmft scores; however, the condition exceeded the recommended WHO thresholds. Caries occurred more frequently on teeth 85 and 36.

Keywords: Adolescent, caries, DMFT, SiC/DMFT ratio, SiC index

Introduction

Dental caries refers to the bacterial-acid dissolution of dental hard tissues, from acid produced from bacterial metabolism on refined sugar diets.[1] Also commonly referred to as tooth decay, caries occurs on all tooth surfaces, but more frequently on the occlusal pits and fissures of molars and premolars.[2] Caries is preventable and reversible in its early stages; however, it presents with restorative challenges in the late stages, leading to infections, eventual tooth loss, and poor quality of life.[3]

The incidence of caries had declined in the past decade due to the introduction of fluoride in community water and dentifrices; yet, the disease still exhibits an uneven distribution pattern in all populations.[4,5] The burden of caries disease is skewed towards population groups of low-income families, medically and developmentally compromised children, and socially vulnerable groups, such as adolescents.[6] Adolescents, especially boys, are at high risk for developing caries due to their more frequent outdoors, between-meal snacking, and high sugar consumption.[7]

Northern Nigeria is a predominantly Muslim society and one in which every child is expected to enroll into a form of Islamic education at a point in life. One group of Islamic schoolchildren is “the Almajirai” or male migrant-pupils, who constitute a significant proportion of the adolescent population.[8] These children spend long unsupervised hours on the streets for fending activities between classes and do not benefit from social welfare services, making them high risk for diseases including caries.[9,10]

The age of 12 is one of the WHO-recognized index age-groups for international comparisons and surveillance of disease trends. Caries at this stage of development suggests poor oral health and predicts future disease on more teeth.[10] Caries experience for index ages is reported using the Decayed Missing and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index, that is, the mean of the sum of the decayed, missing, and filled teeth of the population.[11] The significant caries (SiC) index or the mean one-third of the highest DMFTs is used when the focus is on the minority with the highest caries experience.[12] The current world oral health goal is based on an SiC score of ≤3 in all populations.[13] More recently, the SiC index/DMFT ratio has been used to determine caries severity in population studies.[14,15]

Nearly all available oral health data from Nigeria for adolescents have been based on studies conducted in southern Nigeria.[15,16,17,18,19,20] Northern Nigeria differs distinctly from southern Nigeria in religion, culture, geography, diet, and available dental professionals, among several factors that can impact oral health outcomes.[21] While a few studies have used the SiC index to describe caries in Nigeria, the use of the SiC index/DMFT ratio is not as common, likewise oral health studies involving the Almajirai.[14,19,22] The present study was therefore undertaken to determine the prevalence and severity of dental caries among 10–12-year old males in Kano, Northern Nigeria, and to observe its pattern of occurrence.

Materials and Methods

Study design and protocols

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study of male school-aged children in conventional public and qur′anic schools in Kano, northern Nigeria. Four public schools and two qur′anic schools from two local government areas (one urban and one rural) were selected by systematic random sampling from the list of schools and local governments in Kano state. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Committee for Research and Ethics, Ministry of Health, Kano State, Nigeria. Informed consent was obtained from the School Authorities and the children’s caregivers. With assured confidentiality, all participants gave assent in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All the children benefitted from a free dental education and consultation.

The inclusion criteria, boys 10–12 years of age, who attended either a public primary or qur′anic school, gave assent and parental consent for the research. Children with physical or mental incapacity to participate in the study were excluded.

Sample size determination

The sample size was calculated to be 341 using the formula for descriptive cross-sectional studies.[23]

Study design and protocols

Dental examinations were conducted using individually wrapped and sterilized sets of reusable plane mouth mirrors, wooden spatula, dental explorers, and dry disposable gauze-pads in accordance with the guidelines of the WHO. The children were examined while comfortably seated on a chair in their classrooms while using a light emitting diode (LED) light bulb coupled to the head and directed towards the mouth to provide proper illumination.

Each child was examined for dental caries after drying the teeth with dry sterile gauze-pads and using blunt dental probes and plane mirrors to assess for caries using both the DMFT following the WHO criteria.

DMFT/dmft is the sum of the number of decayed, missing due to caries, and filled teeth in the permanent/primary teeth. The mean number of DMFT/dmft is the sum of individual DMFT values divided by the sum of the population. The SiC index is the mean DMFT of the one-third of the study group with the highest caries score; the index is used as a complement to the mean DMFT value. To calculate SiC index, sort the individuals according to their DMFT, then select one-third of the population with the highest caries values, and then calculate the mean DMFT for this subgroup.

The DMFT, mean DMFT, SiC index, and SiC index/DMFT ratio for deciduous and permanent teeth were calculated for the study population. Data analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA).

Results

Six hundred and ninety-four male adolescents participated in this study: 366 (52.7%) Almajirai and 328 (47.3%) public-school children; their mean age was 11.2 (±0.8) years [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the adolescents

| Almajirai | Public school | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents | 366 (52.7%) | 328 (47.3%) | 694 |

| Age | |||

| 10 | 166 | 0 | 166 |

| 11 | 114 | 90 | 204 |

| 12 | 86 | 238 | 324 |

| Mean age (±SD) | 10.8 (±0.8) | 11.7 (±0.4) | 11.2 (±0.8) |

The prevalence of dental caries was 22.9% with combined mean DMFT and SiC scores of 0.5 (±1.2) and 3.7, respectively. The prevalence of caries in the 12-year olds was 20.7%. The decayed (D) component of the DMFT is 282 out of 289 (97.7%) of the DMFT [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of caries experienced according to the type of adolescents and age group

| Adolescents | N | CP | Prev (%) | D+d | M+m | F+f | Combine DMFT | Mean DMFT | SiC | SiC index/DMFT ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almajirai | 366 | 93 | 25.4 | 282 | 5 | 3 | 289 | 0.6 ± 1.3 | 3.6 | 6.0 |

| Public school | 328 | 66 | 20.1 | 149 | 3 | 0 | 152 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 4.2 | 10.5 |

| Total | 694 | 159 | 22.9 | 431 | 8 | 3 | 441 | 0.5 ± 1.2 | 3.7 | 7.4 |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||||||

| 10 | 166 | 43 | 25.9 | 105 | 2 | 1 | 108 | 0.6 ± 1.4 | 3.3 | 5.5 |

| 11 | 204 | 49 | 24.0 | 263 | 3 | 1 | 267 | 0.5 ± 1.1 | 4.2 | 8.4 |

| 12 | 324 | 67 | 20.7 | 411 | 8 | 2 | 421 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 4.1 | 10.25 |

CP = caries present, Prev.= prevalence, D=decayed permanent teeth, d=decayed primary teeth, M=missing permanent teeth, m=missing primary teeth, F=filled permanent teeth, f=filled primary teeth, DMFT=decayed, missing, and filled teeth, SiC=significant caries index

DMFT >0 ranged from 1 to 8, with the majority of adolescents (n=77% or 48.4%) having a DMFT of =1, whereas 9 (5.6%) adolescents had a DMFT of ≥5 [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The distribution of DMFT scores among the adolescents

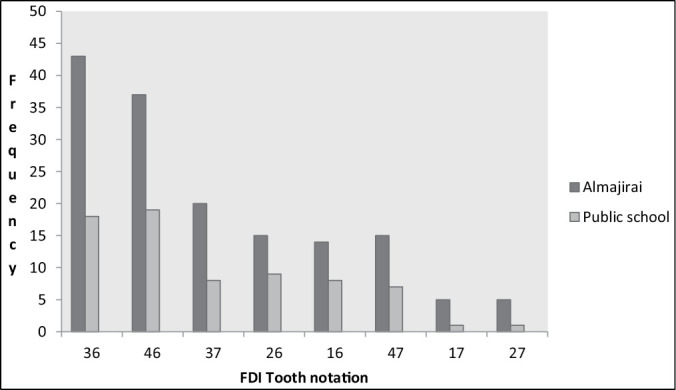

Tooth 85 (or the right mandibular second primary molar) had the highest caries count (n=31; 17.7%) in the primary teeth [Figure 2], whereas tooth 36 (left mandibular permanent first molar) had the highest count (n=61; 27.1%) in the permanent teeth [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Distribution of dental caries on the primary teeth

Figure 3.

Distribution of dental caries on the permanent teeth

The higher proportion of lesions occurred on the left mandibular primary and permanent teeth. The second primary molars and the first permanent molars were comparatively more commonly affected by the disease [Table 3].

Table 3.

Caries distribution on the quadrants of the jaws

| Primary teeth | Maxilla | Mandible | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Left | Right | n | % | Left | Right | n | % | ||

| Primary canine | 5 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| First primary molar | 16 | 9 | 25 | 34.2 | 26 | 20 | 46 | 64.8 | 71 |

| Second primary molar | 23 | 18 | 41 | 41.4 | 31 | 27 | 58 | 58.6 | 99 |

| 44 | 27 | 71 | 40.6 | 57 | 47 | 104 | 59.4 | 175 | |

| P-value | 0.526 | 0.754 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Permanent teeth | Maxilla | Mandible | Total | ||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

| Left | Right | n | % | Left | Right | n | % | ||

|

| |||||||||

| First permanent molar | 24 | 22 | 46 | 28.2 | 61 | 56 | 117 | 71.8 | 163 |

| Second permanent molar | 6 | 6 | 12 | 19.4 | 28 | 22 | 50 | 80.6 | 62 |

| 30 | 28 | 58 | 25.8 | 89 | 78 | 167 | 74.2 | 225 | |

| P-value | 0.893 | 0.754 | |||||||

Discussion

This study provides information on the prevalence, severity, and pattern of presentation of dental caries in a representative sample of 10–12- years-olds in Kano, northern Nigeria. The participants in this study were made up of an almost equal number of school children from both qur′anic and conventional public schools to create for a balanced profile of the adolescent population in Kano state.

The prevalence of dental caries in the study population was low and comparable to the findings of previous regional Nigerian and global studies [seen in Table 4], which placed Nigeria in the low caries category.[16,17,18,19,20] While the findings suggest a uniform caries prevalence among adolescents in Nigeria in different regions, it is however lower than the 54.4% reported in Enugu, Nigeria.[15] This difference in prevalence values may have been due to sampling technique variations, differences in lifestyle, diet, or may represent the true caries prevalence between both the populations.

Table 4.

Caries prevalence studies for 12-year olds and computed SiC index/DMFT ratios

| Authors (years) | Location | Caries prevalence (%) | Mean DMFT | SiC | SiC/DMFT ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okeigbemen (2004)[16] | Benin, Nigeria | 33.0 | 0.51 | — | — |

| Adekoya-Sofowora et al. (2006)[17] | Ife, Nigeria | 13.9 | 0.14 | — | — |

| Agbelusi and Jeboda (2006)[18] | Lagos, Nigeria | 24.6 | 0.46 | — | — |

| Braimoh et al. (2014)[19] | Port Harcourt, | 15.4 | 0.21 | — | — |

| Nigeria | |||||

| Akaji et al. (2021)[15] | Enugu, Nigeria | 54.4 | 1.17 ± 0.27 | 2.57 | 2.2 |

| Cypriano et al. (2008)[24] | Brazil | 93.1 | 5.54 | 9.62 | 1.7 |

| Nurelhuda et al. (2009)[25] | Sudan | 30.5 | 0.42 | 1.4 | 3.3 |

| Shafie Zadeh et al. (2011)[26] | Tehran, Iran | 64.6 | 1.36 ± 0.86 | — | — |

| Gokalp et al. (2010)[27] | Turkey | 61.1 | 1.9 ± 2.2 | 4.33 | 2.3 |

| Vizzotto et al. (2013)[28] | Brazil | 23.0 | 0.84 ± 1.31 | — | — |

| Bhayat and Ahmad (2014)[29] | Saudi Arabia | 57.2 | 1.53 ± 1.88 | 3.63 ± 1.66 | 2.4 |

| Ndanu et al. (2015)[30] | Accra, Ghana | 17.4 | 1.138 ± 0.476 | — | — |

| Elías-Boneta et al. (2016)[31] | Puerto Rico | 69.0 | 2.5 ± 0.12 | 5.6 ± 0.12 | 2.2 |

| Poudyal et al. (2015)[32] | India | — | 1.45 | 2.85 | 1.9 |

| Andegiorgish et al. (2017)[33] | Eritrea | 78.0 | 2.50 ± 2.21 | 4.97 ± 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Riatto et al. (2018)[34] | Spain | — | 1.6 ± 2.6 | 3.2 | 2.0 |

The overall and individual mean DMFT scores from this study place the population in the “very low” category, corroborating previous studies on the oral health status of Nigeria.[6] The SiC scores are, however, higher than those from previously reported Nigerian studies, which may indicate a more severe form of the disease in Kano.[15,20] This finding also highlights that the SiC scores of this population exceed the recommended 2015 global oral health goals thresholds, similar to the experience of their peers in developed countries such as Spain, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey.[27,29,34] Concerted efforts, especially in oral hygiene education and preventive intervention towards children and adolescents, are therefore required to reverse the disease trend in this and similar populations.

In this study, though the Almajirai had comparatively higher caries prevalence and mean DMFT scores, it was the public-school children who possessed higher SiC and SiC index/DMFT ratio scores. The trend supports the recommendation to combine caries indices (DMFT with SiC) for more meaningful interpretations of the disease distribution.[11,12]

Idowu et al.[22] had reported poorer oral health indices for the Almajirai with respect to their private-school peers based on the DMFT index alone. The higher SiC index/DMFT ratio of this population compared with similar adolescents in Enugu, Nigeria and Korea suggests a more severe form of caries in Kano.[14,15] The findings of this study may be considered as reflective of the comparatively poor level of oral health practice of adolescents as well as the status of the dental health system previously reported for northern Nigeria.[9,21,22]

The highest proportion of the DMFT was from the decayed (D) component and portrays the high level of untreated disease and low treatment experience in the population. This finding is similar to the reports from other developing countries, where there are often treatment challenges from ignorance, poverty, and limited dental personnel and services.[15,19,21] Dental treatments, which are considered to be relatively expensive for the average Nigerian, are often better patronized where social incentives are available, as is the case in the developed countries.[35]

The molar teeth in this study were most commonly affected by caries, similar to the findings of other researchers.[15,19,36,37,38] The uneven surface of pits and fissures of molars allow for cariogenic food particles and plaque to be easily retained; furthermore, access for effective oral hygiene can be challenging for posterior teeth, increasing their vulnerability to dental caries. On the contrary, incisors and canines have smooth labial and lingual surfaces and therefore exhibit low retention to cariogenic food particles and plaque and so have surfaces that are less likely to have caries attack.[39,40]

This study also observed that mandibular molars, specifically the mandibular second primary molar and mandibular first permanent molars, were frequently more affected by caries, similar to the observations of some previous studies.[39,40] Mandibular molars often act as stagnation points for food and debris, and they also have a comparatively faster progression for caries.[19] The early eruption of the first permanent molar teeth and comparatively longer exposure to the cariogenic environment increase their vulnerability to caries.[19] An appreciation of the pattern of caries presentation and distribution in this population affords stakeholders with the needed data to execute preventive interventions such as the pre-emptive sealing of the pits and fissures of molar teeth from the age of 6 years, as well as with the evidence to advocate for preventive policies in child oral health.

Conclusion

The prevalence of dental caries in 10–12-year-old adolescents in Kano, northern Nigeria appears low using the DMFT index alone. However, on further scrutiny, high caries severity and SiC scores that exceeded the recommended current oral health benchmarks were observed. The common sites for caries were the mandibular molars, specifically the second primary molars and the first permanent molars.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Touger-Decker R, van Loveren C. Sugars and dental caries. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:881–92S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.4.881S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batchelor PA, Sheiham A. Grouping of tooth surfaces by susceptibility to caries: A study in 5-16 year-old children. BMC Oral Health. 2004;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fejerskov O, Nyvad B, Kidd E, editors. Dental Caries: The Disease and Its Clinical Management. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piovesan C, Mendes FM, Antunes JL, Ardenghi TM. Inequalities in the distribution of dental caries among 12-year-old Brazilian schoolchildren. Braz Oral Res. 2011;25:69–75. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242011000100012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schill H, Wölfle UC, Hickel R, Krämer N, Standl M, Heinrich J, et al. Distribution and polarization of caries in adolescent populations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:4878. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:661–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical Affairs Committee, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on adolescent oral health care. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gbigbidje DL. The phenomenon of Almajiri system of education in northern Nigeria. Int J Arts Soc Sci Res. 2021;4:242–51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idowu EA, Afolabi AO, Nwhator SO. Oral health knowledge and practice of 12 to 14-year-old Almajaris in Nigeria: A problem of definition and a call to action. J Public Health Policy. 2016;37:226–43. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2016.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen PE, Baez RJ. World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. 5th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. pp. 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sajadi FS, Mosharafian S, Torabi M, Hajmohamadi S. Evaluation of DMFT index and significant caries index in 12-year-old students in Sirjan Kerman. J Isfahan Dent Sch. 2014;10:290–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee R, Banerjee B. Significant caries index: A better indicator for dental caries. Int J Public Health. 2019;9:59. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bratthall D. Introducing the significant caries index together with a proposal for a new global oral health goal for 12-year-olds. Int Dent J. 2000;50:378–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HN, Han DH, Jun EJ, Kim SY, Jeong SH, Kim JB. The decline in dental caries among Korean children aged 8 and 12 years from 2000 to 2012 focusing SiC index and DMFT BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0188-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akaji EA, Ikechebelu QU, Osadolor OO. Assessing dental caries and related factors in 12-year-old Nigerian school children: Report from a southeastern state. Eur J Gen Dent. 2020;9:11–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okeigbemen SA. The prevalence of dental caries among 12 to 15-year-old school children in Nigeria: Report of a local survey and campaign. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adekoya-Sofowora CA, Nasir WO, Oginni AO, Taiwo M. Dental caries in 12-year-old suburban Nigerian school children. Afr Health Sci. 2006;6:145–50. doi: 10.5555/afhs.2006.6.3.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agbelusi GA, Jeboda SO. Oral health status of 12-year-old Nigerian children. West Afr J Med. 2006;25:195–8. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v25i3.28277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braimoh OB, Umanah AU, Ilochonwu NA. Caries distribution, prevalence, and treatment needs among 12–15-year-old secondary school students in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. J Dent 2014. 2014:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olatosi OO, Oyapero A, Onyejaka NK. Disparities in caries experience and socio-behavioural risk indicators among private school children in Lagos, Nigeria. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clin Integr. 2020;20:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adeniyi AA, Sofola OO, Kalliecharan RV. An appraisal of the oral health care system in Nigeria. Int Dent J. 2012;62:292–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2012.00122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Idowu EA, Afolabi AO, Umesi DC. Dental caries experience and restorative need among 12–14 year old Almajiris and private school children in Kano. Odontostomatol Trop. 2017;40:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasiulevičius V, Šapoka V, Filipavičiūtė R. Sample size calculation in epidemiological studies. Gerontologija. 2006;7:225–31. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cypriano S, Hoffmann RH, de Sousa Mda L, Wada RS. Dental caries experience in 12-year-old schoolchildren in southeastern Brazil. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008;16:286–92. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572008000400011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nurelhuda NM, Trovik TA, Ali RW, Ahmed MF. Oral health status of 12-year-old school children in Khartoum State, The Sudan: A school-based survey. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shafie Zadeh N, Soleimani F, Askarizadeh N, Mokhtari S, Fatehi R. Dental status and DMFT index in 12 year old children of public care centers in Tehran. Iran Rehabil J. 2011;9:51–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gokalp S, Dogan BG, Tekçiçek M. Prevalence and severity of dental caries in 12 year old Turkish children and related factors. Med J Islam World Acad Sci. 2013;21:11–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vizzotto D, Paiano HM, Rudey AC, Lovera AK, Hagemann P, Gazolla T. DMFT index of 12 year-old students of public schools participating in the Project of Education for Working for Health. Rev Bras Odonto. 2013;10:245–51. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhayat A, Ahmad MS. Oral health status of 12-year-old male schoolchildren in Medina, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20:732–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ndanu TA, Aryeetey R, Sackeyfio J, Otoo G, Lartey A. Oral hygiene practices and caries prevalence among 9–15 years old Ghanaian school children. J Nutr Health Sci. 2015;2:104–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elías-Boneta AR, Crespo Kebler K, Gierbolini CC, Toro Vizcarrondo CE, Psoter WJ. Dental caries prevalence of twelve year olds in Puerto Rico. Commun Dent Health. 2003;20:171–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poudyal S, Rao A, Shenoy R, Priya H. Dental caries experience using the significant caries index among 12 year old school children in Karnataka, India. Int J Adv Res. 2015;3:308–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andegiorgish AK, Weldemariam BW, Kifle MM, Mebrahtu FG, Zewde HK, Tewelde MG, et al. Prevalence of dental caries and associated factors among 12 years old students in Eritrea. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17:169. doi: 10.1186/s12903-017-0465-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riatto SG, Montero J, Pérez DR, Castaño-Séiquer A, Dib A. Oral health status of syrian children in the Refugee Center of Melilla, Spain. Int J Dent. 2018;2018:2637508. doi: 10.1155/2018/2637508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vujicic M, Buchmueller T, Klein R. Dental care presents the highest level of financial barriers, compared to other types of health care services. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:2176–82. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adeniyi AA, Agbaje O, Onigbinde O, Ashiwaju O, Ogunbanjo O, Orebanjo O, et al. Prevalence and pattern of dental caries among a sample of Nigerian public primary school children. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2012;10:267–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eigbobo JO, Etim SS. The pattern of dental caries in children in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2015;5:20–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Umesi-Koleoso DC. Dental caries pattern of first and second permanent molars and treatment needs among adolescents in Lagos. Niger Dent J. 2007;15:78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Darwish M, El Ansari W, Bener A. Prevalence of dental caries among 12-14 year old children in Qatar. Saudi Dent J. 2014;26:115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elfrink ME, Veerkamp JS, Kalsbeek H. Caries pattern in primary molars in Dutch 5-year-old children. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2006;7:236–40. doi: 10.1007/BF03262558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]