Abstract

Background

Polyneuritis cranialis (PNC) with the disease characteristics of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) in addition to both ocular and bulbar weakness in the absence of limb paralysis or ataxia is defined as an unusual variant of GBS. As evidence of central nervous system (CNS) involvement, visual impairment is an unusual finding complicating with GBS spectrum disorders and has never been reported in patients with PNC.

Methods

We describe a very rare case who clinically presented with progressive multiple cranial nerve palsy and visual impairment. Furthermore, a literature search of concurrent GBS and optic neuritis (ON) as well as PNC attributed to GBS was conducted.

Results

A diagnosis of PNC was considered due to the typical clinical characteristics as well as the presence of cerebrospinal fluid cytoalbumin dissociation and serum antibodies against gangliosides. The clinical manifestations and the bilateral optic nerve involvement in brain magnetic resonance imaging further suggested possible optic neuritis (ON). The patient received treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin followed by short-term use of corticosteroids and finally achieved a full recovery. Thirty-two previously reported cases (17 women, mean age 40) of concurrent GBS and ON and 20 cases of PNC (5 women, mean age 40) were analyzed. We further provided a comprehensive discussion on the potential etiologies, clinical features, therapeutic strategies, and prognosis.

Conclusions

This rare case with the co-occurrence of PNC and visual impairment and the related literature review may help clinicians advance the understanding of GBS spectrum disorders and make appropriate diagnoses and treatment decisions for the rare variants and CNS complications of GBS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10072-022-06580-0.

Keywords: Guillain-Barré syndrome, Polyneuritis cranialis, Optic neuritis, Anti-ganglioside antibodies, Wakerley classification, Literature review

Introduction

Polyneuritis cranialis (PNC) is used to describe a clinical pattern restricted to concurrent involvement of multiple cranial nerves (CN) with various etiologies [1]. A recent Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) classification system proposed that PNC with both ocular and bulbar weakness in the absence of limb paralysis or ataxia in addition to the characteristics of GBS is defined as a rare variant of GBS [2, 3]. As evidence of central nervous system (CNS) involvement, visual impairment is an unusual finding complicating with GBS spectrum disorders [4–6] and has never been reported in patients with PNC. Herein, we report a rare case with a clinical presentation of PNC and visual impairment possibly attributed to optic neuritis (ON) concurrently. Importantly, we further reviewed previously reported cases of concurrent GBS and ON, as well as cases of PNC attributed to GBS, to provide a comprehensive picture of the rare variant/CNS complication of GBS.

Methods

We present the case of a 54-year-old male patient with co-occurrence of PNC and possible ON. Furthermore, a literature search of concurrent GBS and ON, as well as PNC attributed to GBS, was conducted in PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science between 1960 and December 2021. Non-English-language publications or studies with insufficient clinical data were excluded. All cases were summarized and analyzed.

Results

Case presentation

A 54-year-old Chinese male with no remarkable medical history was admitted to our hospital for progressive visual loss and diplopia accompanied by headache and vomiting for 4 days. His headache was distending and nonthrobbing, and located in the frontal area. Nine days prior to admission, he had a cough and low-grade fever, suggestive of an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). On admission, he was afebrile and fully conscious. Initial neurologic examination revealed bilateral and partial external ophthalmoparesis in horizontal and vertical gaze (especially a limitation on horizontal movement) along with binocular horizontal and vertical diplopia in the absence of nystagmus. His visual acuity (VA) was 6/50 in the right eye and 6/30 in the left eye with a normal fundus. His pupils were 3 mm in diameter with a sluggish pupillary response. Additionally, bilateral absence of color vision was also revealed. All other cranial nerves were normal. The motor examination showed normal tone and bulk, but deep tendon reflexes were not elicited in all limbs. No sensory symptoms, ataxia, or meningeal irritation signs were noted.

His symptoms continued to deteriorate and he complained of severe dizziness and nasal voice on the 3rd day of admission. Bilateral complete ophthalmoplegia with fixed eyes, absent pupillary reflexes, and left facial palsy were present. One day later, his facial palsy progressed bilaterally, and he experienced difficulty in swallowing, chewing, and vocalizing and was unable to protrude the tongue. He was nearly blind. Comprehensively, he showed bilateral CN II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, IX, X, and XII involvement with no limb weakness, sensory disturbance, or ataxia.

Laboratory tests for complete blood count, routine biochemical tests, thyroid function, tumor markers, antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and paraneoplastic antibodies were unremarkable. On the 5th day after the neurological event, the CSF examination revealed a normal pressure, obvious cytoalbumin dissociation (white cell count of 2 × 106 cells/l and protein content of 172 mg/dl), and negative cytology and culture; a repeated CSF test on the 13th day produced similar results. No pathogenic organism was detected in the serum or CSF using metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) (the 5th day and 13th day after onset). Furthermore, we tested for serum and CSF antibodies against gangliosides, Ranvier node, CNS demyelinating disease (including anti-AQP4, -MOG, and -MBP antibodies), and IgG oligoclonal bands. Serum anti-GM1 and anti-GD1a IgG antibodies were positive, whereas normal results were obtained for other serum and CSF antibodies.

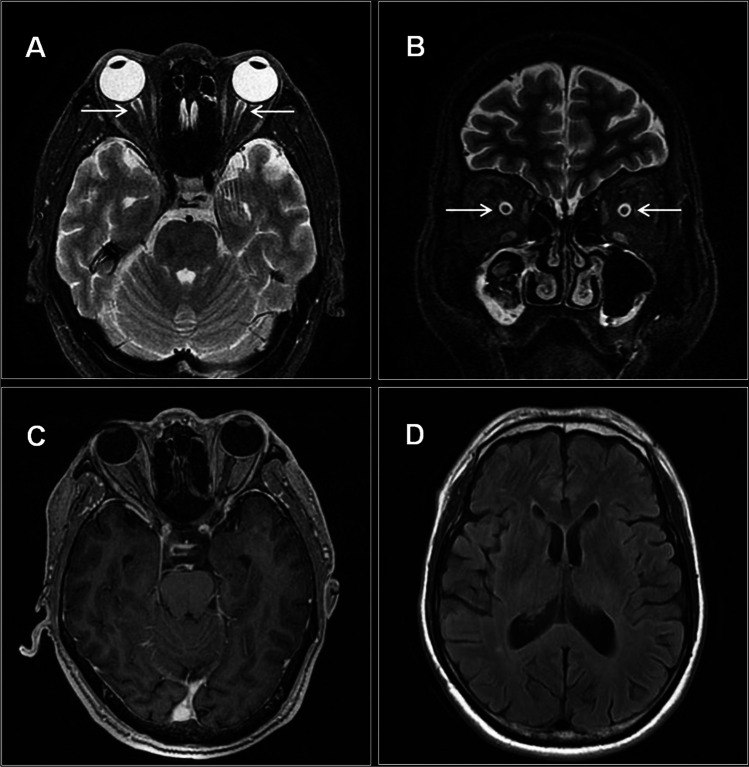

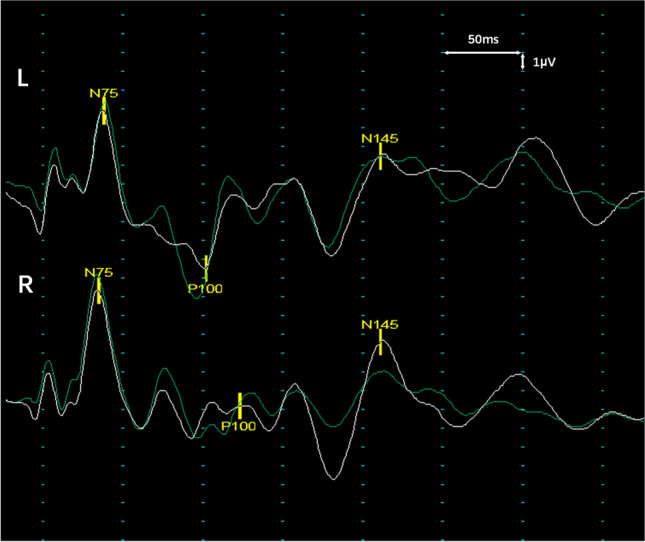

The results of electronic nasopharyngoscopy and computed tomography angiography were normal. His visual evoked potential (VEP) revealed a bilateral severe delayed P100 latency (left eye: 152 ms; right eye: 173 ms) with discrete amplitude (Fig. 1). A series of nerve conduction studies (NCS) indicated a mild prolonged distal motor latency and slower sensory conduction velocity of the median nerve, decreased persistence of the F-waves of the ulnar nerve, and absent H-waves of the tibial nerve (only the left limbs were examined). In addition, the blink reflex showed absent bilateral R1 and R2 responses, whereas facial nerve conduction studies were normal. Brain and spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) disclosed slight sheath edema in the bilateral optic nerves without gadolinium enhancement and other abnormalities were unremarkable (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Representative waveforms of the VEP. Checkerboard-stimulation VEP shows bilateral severe prolonged P100 latency with discrete amplitude, 11 days after neurological event initiation

Fig. 2.

Brain MRI of the present case. A, B Axial and coronal MR images show slightly increased signals (arrows) in the bilateral optic nerves without enhancement (C). D No other abnormalities are noted by brain MRI

According to typical clinical manifestations (presentations due to the damage of multiple CNs, including ocular and pharyngeal weakness; acute onset with areflexia; and no limb weakness or ataxia), CSF cytoalbumin dissociation, and the presence of IgG anti-GM1 and GD1a antibodies, PNC, a rare variant of GBS, was suspected. Furthermore, based on the clinical manifestations and the abnormalities revealed by MRI, the visual impairment in the present case was possibly attributed to ON. The bilateral delayed P100 latencies in VEP may be helpful to further support the diagnosis. The patient received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment for 5 days (0.4 g/kg/day) and his clinical symptoms resolved remarkably, especially neurological symptoms other than the visual impairment. On the 23rd day after onset when he requested discharge, his VA recovered to 6/24 in the right eye and 6/20 in the left eye and he only experienced mild residual other neurological symptoms. Then he received corticosteroid treatment (intravenous dexamethasone 10 mg/day) for 10 days in a local hospital, followed by a tapering course of oral steroids. He had almost completely recovered at the 1-month follow-up after discharge with bilateral VA recovering to 6/6. At a telephone follow-up 1 year later, he reported normal vision, limb strength, and activities of daily living.

Literature review

A total of 32 patients with concurrent GBS and ON were included in the literature review. The mean age was 40 years (range, 7–81 years) for 15 (47%) males and 17 (53%) females. Most patients had symptomatic antecedent infections and Mycoplasma pneumoniae was the most common pathogenic microorganism. Symptoms of ON may occur synchronously with (18, 56%), earlier (6, 19%), or later (8, 25%) than other neurological symptoms. Bilateral ON was observed in 24 (75%) patients and 25 (78%) patients showed severe visual loss (VA of 20/200 or worse in the affected eye). IgG anti-GQ1b antibodies (8, 47%) and IgG anti-GM1 (4, 23%) antibodies were the most common serum antibodies against gangliosides in the documented cases. Twenty-nine of 32 patients received immunotherapy, mainly including steroids, IVIG, and plasma exchange (PE). For ON, 47% of the patients had a poor prognosis (VA no better than 20/40 in the affected eye), whereas most patients had a favorable prognosis (full recovery or almost normal) for other neurological symptoms (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables S1–S2).

Table 1.

Cases of concurrent GBS and ON collected in the literature

| Case | Age/sex | Wakerley classification | Antecedent illness (identified pathogens) | Side of the ON | Severe visual loss | Time lag between ON and other neurological deficits | Serum antibodies to gangliosides | MRI findings of optic nerves | Immunotherapy | Poor recovery of ON (time after onset) | Outcome of other neurological symptoms (time after onset) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [26] | 62/M | UC | ND (negative) | R | + | 2 weeks (ON → others) | ND | NL | 1st (ON): steroids; 2nd (GBS): ACTH | − (12 days) | CR (TU) |

| 2 [27] | 17/F | Classic GBS | URTI (ND) | BI | − | 2 weeks (others → ON) | ND | ND | Steroids | − (TU) | CR (TU) |

| 3 [28] | 18/F | Classic MFS | Pelvic abscess (ND) | BI | + | Simultaneous | ND | ND | ACTH | + (3 months) | CR (3 months) |

| 4 [29] | 76/F | GBS/MFS overlap | ND (EBV) | BI | + | Simultaneous | ND | NL | No | − (1 year and 2 months) | CR (TU) |

| 5 [30] | 18/M | Classic GBS | Leukemia | BI | + | Simultaneous | ND | ND | Anti-leukemic therapy | + (died, 4 weeks) | Died (4 weeks) |

| 6 [31] | 28/F | Classic GBS | URTI (M. pneumoniae) | BI | + | 20 days (others → ON) | ND | NL | 1st: PE → PR, but ON appeared; 2nd: steroids | + (several months) | Nearly normal (several months) |

| 7 [32] | 22/M | Classic GBS | IRTI (M. pneumoniae) | BI | + | 11 days (others → ON) | ND | NL | 1st: IVIG → PR, but ON appeared; 2nd: steroids | + (26 days) | PR (26 days) |

| 8 [33] | 57/F | MFS/PCB overlap | URTI (negative) | BI | − | Simultaneous | IgG anti-GQ1b | NL | IVIG | − (2 months) | CR (2 months) |

| 9 [34] | 53/M | Classic GBS | ND (M. pneumoniae) | BI | + | 5 days (ON → others) | ND | NL | PE, steroids | + (2 months) | PR (2 months) |

| 10 [35] | 23/F | Classic MFS | ND (negative) | L | + | Simultaneous | IgG anti-GM1, GQ1b | NL | 1st: PE → CR, but relapsed 8 months later; 2nd: PE | − (14 months) | CR (14 months) |

| 11 [36] | 69/M | Classic GBS | URTI (M. pneumoniae) | BI | + | 10 days (ON → others) | ND | ND | 1st: steroids → PR, but other neurological symptoms occurred; 2nd: IVIG | − (46 days) | PR (46 days) |

| 12 [22] | 68/M | Classic GBS | URTI (CMV) | BI | + | Simultaneous | IgG anti-GQ1b, GT1a | NL | 1st: IVIG → PR excepted for ON; 2nd: steroids | + (6 months) | Could walk 1 km without support (6 months) |

| 13 [25] | 49/F | UC | URTI (EBV) | R | + | Simultaneous | ND | NL | Steroids → other deficits deteriorated, and then IVIG | + (35 days) | Can walk without support (35 days) |

| 14 [37] | 62/F | Classic MFS | Fever (negative) | BI | + | Simultaneous | ND | NL | No | + (6 weeks) | CR (6 weeks) |

| 15 [38] | 28/F | Classic GBS | Measles | BI | + | 4 days (others → ON) | ND | NL | Steroids | + (3 months) | ND |

| 16 [39] | 31/M | MFS/PCB overlap | Fever and GI (negative) | R | − | 2 days (ON → others) | IgG anti-GQ1b | NL | IVIG | − (TU) | CR (TU) |

| 17 [40] | 56/M | Classic GBS | Fever and GI (possible C. jejuni) | BI | − | 6 weeks (others → ON) | IgG anti-GD1a | NL | IVIG | − (8 months) | CR (8 months) |

| 18 [4] | 50/M | Classic GBS | URTI (negative) | BI | + | Simultaneous | IgG anti-GM1 | Abn | Ist: IVIG with steroids → ON worsen and other neurological deficits improved; 2nd: steroids followed by PE | + (5 months) | CR (3 months) |

| 19 [41] | 33/M | UCa | IRTI (negative) | R | + | Simultaneous possibly | IgG anti-GQ1b, GT1a | Abn | Steroids | − (3 weeks) | CR (1 week) |

| 20 [42] | 81/F | Classic MFS | ND (negative) | R | − | Simultaneous | IgG anti-GQ1b | NL | No | − (8 weeks) | CR (8 weeks) |

| 21 [43] | 45/F | UCa | URTI (M. pneumoniae) | BI | + | 3 days (others → ON) | IgG anti-GM1 | Abn | Steroids, IVIG, azathioprine | + (6 months) | PR (6 months) |

| 22 [23] | 33/M | GBS/MFS overlap | GI (negative) | L | − | Simultaneous | IgG anti-GQ1b | Abn | 1st: IVIG → ON worsen and other neurological deficits improved; 2nd: steroids | − (about 2 weeks) | Significant improvement (9 days) |

| 23 [44] | 14/M | Classic GBS | URTI (negative) | BI | + | 3 days (ON → others) | Negative | NL | Steroids followed by IVIG | − (following weeks) | CR (following weeks) |

| 24 [45] | 39/F | UCa | URTI (M. pneumoniae) | BI | + | Simultaneous | ND | Abn | Steroids → NE, and then PE | + (8 months) | CR (about 2 weeks) |

| 25 [46] | 19/F | Classic GBS | URTI (ND) | BI | + | Simultaneous | Negative | Abn | IVIG | − (5 months) | Nearly CR (1 month) |

| 26 [47] | 21/M | Classic GBS | Leptospirosis (Leptospira) | BI | + | Almost simultaneous | ND | NL | IVIG, and then PE | + (TU) | PR (TU) |

| 27 [48] | 43/F | Classic GBS | URTI (ND) | BI | − | 8 days (ON → others) | ND | NL | IVIG followed by steroids | − (3 weeks) | PR (3 weeks) |

| 28 [49] | 12/F | UCa | URTI (M. pneumoniae) | BI | + | 16 days (others → ON) | IgM anti-Gal-C | Abn | Steroids | − (10 days) | CR (10 days) |

| 29 [50] | 73/M | Acute ophthalmoparesis | GI (ND) | BI | + | Simultaneous | IgG anti-GQ1b | NL | Steroids, IVIG | − (about 1 month) | CR (about 1 month) |

| 30 [24] | 14/F | Classic GBS | No (M. pneumoniae) | BI | + | Simultaneous | Negative | Abn | 1st: steroids → NE expected for ON; 2nd: PE, IVIG → NE; 3rd: steroids → NE; 4th: rituximab | − (3 years) | PR (3 years) |

| 31 [24] | 7/F | Classic GBS | URTI (M. pneumoniae) | R | + | ND (others → ON) | Negative | ND | IVIG → NE, and then steroids | + (11 months) | CR (11 months) |

| 32 present case | 54/M | PNC | URTI (negative) | BI | + | Simultaneous | IgG anti-GM1, GD1a | Abn | IVIG, and then steroids | − (2 months) | CR (2 months) |

Abn, abnormal; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CR, complete remission; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal illness; IRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; MFS, Miller-Fisher syndrome; ND, not described; NE, not effective; NL, normal; ON, optic neuritis; PCB, pharyngeal-cervical-brachial weakness; PE, plasma exchange; PR, partial remission; TU, time unknown; UC, uncertain; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; L, left; R, right; BI, bilateral; M, male; F, female

aThese cases may be classified into “pure sensory variant” which were described in the diagnostic framework reported by Shahrizaila et al. [7] yet not included in the classification framework proposed by Wakerley and Yuki [2]

Twenty cases of PNC attributed to GBS have been reported. The median age was 40 years (range, 6–67 years) with a male predominance (75% male and 25% female). Facial weakness, normal tendon reflexes, and significant asymmetry were accounting for 70%, 50%, and 22% of cases documented respectively. IgG anti-GQ1b antibodies (47% in the described patients) were the most frequent anti-ganglioside antibodies detected in PNC patients, followed by IgG anti-GT1a and IgG anti-GD1a antibodies. Abnormalities in NCS for limbs were observed in 32% of the cases that were clearly described. Eight patients received monotreatment with IVIG, 2 with steroids, and 3 received the treatment of both IVIG and steroids. All patients displayed clinical improvement without respiratory muscle weakness even though 6 received no special treatment, and full recovery occurred in more than half of the cases (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S3).

Table 2.

Cases with PNC attributed to GBS collected in the literature

| Case | Age/sex | Antecedent illness (identified pathogens) | Initial symptoms (ocular/bulbar/others) | Cranial nerve involved | Significant asymmetry | Deep tendon reflexes | CSF: cell count (μl)/protein (mg/dl) (days after onset) | Serum anti-ganglioside antibodies | EDX for limbs (days) | EDX for cranial nerves (days) | Treatment | Outcome (time after onset) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [51] | 39/M | No (ND) | Bulbar | III, V, VII, IX, X | Yes | Absent | 0/105 (TU) | ND | NL(TU) | ND | Steroids | CR (within months) |

| 2 [52] | 41/F | Post-partum (NL) | Bulbar | III, IV, VI, VII, IX, X | No | Absent | CAD + (TU) | ND | NL (TU) | ND | No | PR (2 weeks) |

| 3 [53] | 36/F | URTI (ND) | Ocular | III, IV, VI, VII, IX, X | No | Absent | 2/82 (TU) | ND | NL (TU) | ND | Steroids | CR (3 months) |

| 4 [54] | 48/M | URTI (ND) | Ocular | III, IV, VI, VII, IX, X, XI, XII | No | Normal | 0/43 [7] | IgG anti-GT1a | NL (TU) | Abn (TU) | Immunoadsorption therapy, steroids, IVIG | CR (10 months) |

| 5 [55] | 67/F | URTI (ND) | Ocular | III, IV, VI, VII, IX, X | No | ND | 2/70 [10] | ND | Abn [13] | NL [13] | No | CR (3 weeks) |

| 6 [55] | 33/M | URTI (ND) | Ocular and bulbar | III, V, VI, VII, IX, X | No | Normal | 0/118.5 [9] | ND | Abn [12] | ND | IVIG | CR (6 weeks) |

| 7 [55] | 47/M | URTI (ND) | Facial weakness | III, VI, VII, IX, X | No | Absent | 0/15.7 [7] | IgG anti-GQ1b | NL (TU) | ND | No | PR (9 weeks) |

| 8 [56] | 10/M | Fever (negative) | Ocular and bulbar | III, IV, V, VI, VII, IX, X, XII | Yes | Normal | CAD- (TU) | Negative | NL (TU) | Abn (TU) | IVIG | PR (over months) |

| 9 [57] | 52/M | URTI (negative) | Ocular | III, VI, VII, IX, X | No | Normal | 0/78 (TN) | IgG anti-GQ1b | Abn (TU) | ND | IVIG | CR (8 weeks) |

| 10 [58] | 48/M | GI (ND) | Ocular and bulbar | III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII | No | Normal | CAD- (TU) | IgG anti-GQ1b | NL [3, 17] | Abn [3, 17] | IVIG | PR (11 weeks) |

| 11 [59] | 20/M | No (ND) | Ocular and bulbar | III, VI, VI, IX, X | No | Normal | CAD- [7]; -/96[14] | Negative | NL [8] | ND | IVIG | CR (5 months) |

| 12 [60] | 21/M | No (ND) | Bulbar | III, IV, VI, VII, IX, X | ND | Absent | ND | IgG anti-GQ1b, GT1a | NL [2] | NL [2] | No | CR (7 weeks) |

| 13 [60] | 18/M | GI (ND) | Ocular and bulbar | III, IV, VI, IX, X | ND | Normal | CAD- [7] | Ig G anti-GT1a | NL [18] | NL [8] | No | CR (6 weeks) |

| 14 [61] | 6/Fa | URTI (Streptococcus pyogenes) | Ocular and bulbar | VI, IX, X | No | ND | 0/78 (TU) | Negative | ND | ND | IVIG, steroids | CR (1 month) |

| 15 [62] | 22/M | GI (ND) | Ocular and Bulbar | III, IX, X | No | Absent | CAD- (TU) | Ig G anti-GQ1b | NL (TU) | ND | No | PR (by weeks) |

| 16 [63] | 60/F | No (ND) | Bulbar | III, IV, V, VI, IX, X, XII | Yes | Decreased | CAD- (TU) | Ig G anti-GQ1b | NL (TU) | ND | IVIG | PR (3 months) |

| 17 [64] | 62/M | GI (negative) | Sensory disturbance in limbs | III, VII, IX, X, XII | No | Normal | 1/40 (TU) | IgG anti-GQ1b, GD1a, GT1b | Abn (TU) | ND | IVIG | PR (47 days) |

| 18 [65] | 55/M | COVID-19 | Ocular and bulbar | III, V, IX, X, XII | No | Decrease | CAD- (TU) | Negative | Abn (TU) | ND | IVIG | PR (TU) |

| 19 [66] | 60/M | URTI (Francisella tularensis) | Facial weakness | III, IV, VI, VII, IX, X | Yes | Normal | 0.6/31 (TU) | Negative | NL [11] | Abn [11] | Steroids, IVIG, | Significant improvement (about 6 weeks) |

| 20 (present case) | 54/M | URTI (negative) | Ocular | II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, IX, X, XII | No | Absent |

2/172 [5] 2/217 [13] |

IgG anti-GM1, GD1a | Abn [11] | Abn [17] | IVIG, Steroids | Almost CR (2 months) |

This is an updated literature review based on a previous review published in 2015 [3] and we identified 9 new cases of PNC between 2015 and December 2021. The diagnosis of PNC attributed to GBS strictly conformed to the definition of PNC proposed by Wakerley and Yuki [2], and patients with any ataxia or limb weakness were excluded. According to the diagnostic criteria, in this literature analysis we excluded 4 cases reported in a previous literature review of PNC [3]

Abn, abnormal; CAD, cytoalbumin dissociation; CR, complete remission; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; EDX, electrodiagnostic study; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal illness; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; ND, not described; NL, normal; PE, plasma exchange; PNC, polyneuritis cranialis; PR, partial remission; TU, time unknown; UC, uncertain; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; M, male; F, female

aA 10-year-old sister of the patient who may also be considered PNC was not included in the analysis due to the insufficient details

Discussion

The optic nerves are considered a part of the CNS which are almost invariably spared in PNC and seldom involved in GBS spectrum disorders [4]. Convergent evidence has suggested that anti-ganglioside antibodies play important roles in GBS spectrum disorders, and subtypes/clinical symptoms of GBS are usually associated with specific anti-ganglioside antibodies which may be attributed to the relatively high expression of target glycolipids in different nerve tissues of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), including CNs [7]. For example, the characteristic distribution of GQ1b (highly expressed in CN III, IV, and VI) and GT1a (highly expressed in CN IX, X, and XII) in CNs is compatible with the clinical association between anti-GQ1b antibodies and ocular palsy [8], and the association between anti-GT1a antibodies and bulbar palsy [9]. Notably, some gangliosides (i.e., GQ1b and GM1 gangliosides) are also relatively enriched in the optic nerves that are considered parts of the CNS [10]. Hence, one could speculate that the common antigenic ganglioside epitopes shared by both the optic nerves and PNS may be activated through infection-induced molecular mimicry, leading to the co-occurrence of GBS and ON [11, 12]. This hypothesis was supported by the results of our literature analysis, which showed that the majority of tested patients with concurrent GBS and ON carried IgG anti-GQ1b or anti-GM1 antibodies. Furthermore, the symptoms of ON and GBS occurred simultaneously or sequentially in a short time, and most patients had a history of antecedent infections without pleocytosis in the CSF, suggesting a post-infectious immune-mediated etiology in most cases. Notably, our patient presented with bilateral and severe visual loss, monophasic course, and no detection of antibodies related to CNS demyelinating diseases, consistent with the characteristics of most published cases with concurrent ON and GBS and other post-infectious ON [13, 14].

In addition to post-infectious ON, some other etiologies are also responsible for visual impairment complicating with GBS, such as increased intracranial pressure [6] and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome [5]. Nevertheless, these causes should not be considered in the present case given the normal CSF pressure and unremarkable MRI findings beyond the optic nerves. Furthermore, since neither optic edema nor contrast enhancement of the optic nerve sheath (especially the feature of “tram-tracks”), the sclera, or extraocular muscles was observed [13, 15], the diagnosis of optic perineuritis should not be supported. Overall, according to the evidence of the history and paraclinical tests, we believed that it was reasonable to diagnose the patient with possible ON.

PNC is considered a rare entity that lies at the borderland between GBS and MFS [2]. Our results of an updated literature analysis based on a previous review [3] indicated that patients with PNC are more likely to present with atypical GBS characteristics than patients with other variants, including a significantly higher proportion of normal tendon reflex, significant asymmetry, and facial weakness [2, 16]. These findings, along with a relatively benign clinical process and good prognosis even without any immunotherapy in all cases, further supported PNC as a separate subtype of GBS rather than an overlap of distinct subtypes. IgG anti-GQ1b antibodies were the relatively frequent types of anti-ganglioside antibodies detected in patients with PNC, whereas our case was positive for serum IgG anti-GM1 and anti-GD1a antibodies. It should be noted that anti-ganglioside antibodies are not necessary for the diagnosis of PNC due to insufficient specificity, and previous studies have reported various cases with anti-ganglioside antibody positivity but atypical clinical manifestations [17–19]. Given the rare frequency of PNC attributed to GBS, further studies are warranted to determine the exact role of the PNC variant in GBS spectrum disorders.

The most effective treatment protocol for concurrent GBS and ON remains uncertain, according to the potential conflicting therapeutic requirements of patients with GBS or ON [7, 20, 21]. The severe visual disability of our case finally benefitted from corticosteroids following IVIG, suggesting that the traditional immunotherapies for GBS (mainly PE and IVIG) may be not sufficient for these patients, which is also supported by previous studies [22–24]. On the other hand, corticosteroids may delay the clinical recovery of patients with GBS [20] and lead to the aggravation of limb weakness in some cases with concurrent GBS and ON [24, 25]. Therefore, early and individualized treatment is essential depending on the appearance and development of symptoms, and the use of corticosteroids may be necessary especially in patients with a severe visual impairment considering that approximately half of the patients with concurrent GBS and ON had a relatively poor prognosis for visual impairment.

Some limitations should be addressed. First, our patient did not undergo examinations of the visual field due to his very poor eyesight and lack of coordination. An optical coherence tomography examination was also not completed because the patient declined. Second, despite a prior URTI, the etiology of this case remained unclear, although mNGS for detecting pathogens was performed twice. Third, anti-ganglioside antibodies were only determined qualitatively without longitudinal observation of antibody titers. Nevertheless, we believed that the diagnosis should not be affected. Finally, only publications in English were included in the literature review and some data in a portion of previous publications were not available, which inevitably affected the results.

Conclusions

In this article, we reported a very rare case with a presentation of concurrent PNC and visual impairment possibly attributed to ON, and further systemically reviewed historical reported cases of concurrent GBS and ON as well as PNC respectively. The case report and literature review contribute to our understanding of GBS spectrum disorders and facilitate appropriate diagnosis and treatment decisions for the rare variant/CNS complications of GBS.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Bitao Bu, Dr. Xian Zhang, and Dr. Bo Chen for the suggestions into the study.

Author contribution

WZ designed the study. HL and WZ conducted literature review and drafted the manuscript. HL, BH, and NT collected data. ZL, BH, NT, SX, and WZ made substantial contributions to conception and interpretation of data. ZL and WZ revised the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2021CFB382) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81801146).

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Declarations

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Informed consent

Written informed consent for publication of clinical details was obtained from the patient and/or the family.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carroll CG, Campbell WW. Multiple cranial neuropathies. Semin Neurol. 2009;29(1):53–65. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1124023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wakerley BR, Yuki N. Polyneuritis cranialis–subtype of Guillain-Barré syndrome? Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(11):664. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakerley BR, Yuki N. Polyneuritis cranialis: oculopharyngeal subtype of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Neurol. 2015;262(9):2001–2012. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7678-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biotti D, Vignal C, Sharshar T, Gout O, McCoy AN, Miller NR. Blindness, weakness, and tingling. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57(6):565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen A, Kim J, Henderson G, Berkowitz A. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Clin Neurosci: official J Neurosurg Soc Aust. 2015;22(5):914–916. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doxaki C, Papadopoulou E, Maniadaki I, Tsakalis NG, Palikaras K, Vorgia P. Case report: intracranial hypertension secondary to Guillain-Barre syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:608695. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.608695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shahrizaila N, Lehmann HC, Kuwabara S. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet (London, England) 2021;397(10280):1214–1228. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00517-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahrizaila N, Yuki N. Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis and Fisher syndrome: anti-GQ1b antibody syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(5):576–583. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koga M, Yoshino H, Morimatsu M, Yuki N. Anti-GT1a IgG in Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72(6):767–771. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiba A, Kusunoki S, Obata H, Machinami R, Kanazawa I. Ganglioside composition of the human cranial nerves, with special reference to pathophysiology of Miller Fisher syndrome. Brain Res. 1997;745(1–2):32–36. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuki N. Infectious origins of, and molecular mimicry in, Guillain-Barré and Fisher syndromes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(01)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshino H, Maeda Y, King M, Cartwright MJ, Richards DW, Ariga T, et al. Sulfated glucuronyl glycolipids and gangliosides in the optic nerve of humans. Neurology. 1993;43(2):408–411. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Sethi P, Duvesh R, Sethi HS, Naik M, Rai HK. Optic perineuritis BMJ open ophthalmology. 2021;6(1):e000745. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2021-000745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petzold A, Fraser CL, Abegg M, Alroughani R, Alshowaeir D, Alvarenga R, et al. Diagnosis and classification of optic neuritis. The Lancet Neurol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(22)00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie JS, Donaldson L, Margolin E. Optic perineuritis: a Canadian case series and literature review. J Neurol Sci. 2021;430:120035. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2021.120035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudulagunta SR, Sodalagunta MB, Sepehrar M, Khorram H, Bangalore Raja SK, Kothandapani S, et al (2015) Guillain-Barré syndrome: clinical profile and management. German Med Sci 13:Doc16. 10.3205/000220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Tan CY, Razali SNO, Goh KJ, Shahrizaila N. Determining the utility of the Guillain-Barré syndrome classification criteria. J Clin Neurol (Seoul, Korea) 2021;17(2):273–282. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2021.17.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodrigo-Rey S, Gutiérrez-Ortiz C, Muñoz S, Ortiz-Castillo JV, Siatkowski RM. What did he eat? Surv Ophthalmol. 2021;66(5):892–896. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oomura M, Uchida Y, Sakurai K, Toyoda T, Okita K, Matsukawa N. Miller Fisher syndrome mimicking Tolosa-Hunt syndrome. Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 2018;57(18):2735–2738. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.0604-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes RA, Brassington R, Gunn AA, van Doorn PA. Corticosteroids for Guillain-Barré syndrome. The Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. 2016;10(10):Cd001446. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001446.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toosy AT, Mason DF, Miller DH. Optic neuritis. The Lancet Neurology. 2014;13(1):83–99. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Igarashi O, Fujioka T, Kishi M, Normoto N, Iwasaki Y, Kurihara T. Guillain-Barré syndrome with optic neuritis and cytomegalovirus infection. J Peripheral Nerv System : JPNS. 2005;10(3):340–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.10313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lubomski M, Tisch S. An unusual presentation of Miller Fisher syndrome with optic neuropathy. Intern Med J. 2016;46(8):986–987. doi: 10.1111/imj.13151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen EW, Ryan MM, Leventer RJ. Guillain-Barré syndrome with optic neuritis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jpc.15656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.An JY, Yoon B, Kim JS, Song IU, Lee KS, Kim YI. Guillain-Barré syndrome with optic neuritis and a focal lesion in the central white matter following Epstein-Barr virus infection. Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 2008;47(17):1539–1542. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nikoskelainen E, Riekkinen P. Retrobulbar neuritis as an early symptom of Guillain-Barre syndrome. Report Case Acta ophthalmologica. 1972;50(1):111–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1972.tb05647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Behan PO, Lessell S, Roche M. Optic neuritis in the Landry-Guillain-Barré-Strohl syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60(1):58–59. doi: 10.1136/bjo.60.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams B, Ghosh TN, Stockley RA. Ophthalmoplegia, amblyopia, and diffuse encephalomyelitis associated with pelvic abscess. BMJ. 1979;1(6161):453. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6161.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toshniwal P. Demyelinating optic neuropathy with Miller-Fisher syndrome The case for overlap syndromes with central and peripheral demyelination. J Neurol. 1987;234(5):353–8. doi: 10.1007/bf00314295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phanthumchinda K, Intragumtornchai T, Kasantikul V. Guillain-Barré syndrome and optic neuropathy in acute leukemia. Neurology. 1988;38(8):1324–1326. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.8.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadkarni N, Lisak RP. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) with bilateral optic neuritis and central white matter disease. Neurology. 1993;43(4):842–843. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson RD, Ohlrich GD, Pender MP. Guillain-Barré syndrome and optic neuritis after Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Aust N Z J Med. 1998;28(4):481–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1998.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colding-Jørgensen E, Vissing J. Visual impairment in anti-GQ1b positive Miller Fisher syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103(4):259–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfausler B, Engelhardt K, Kampfl A, Spiss H, Taferner E, Schmutzhard E. Post-infectious central and peripheral nervous system diseases complicating Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection Report of three cases and review of the literature. Europ J Neurol. 2022;9(1):93–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan JW. Optic neuritis in anti-GQ1b positive recurrent Miller Fisher syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(9):1185–1186. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.9.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ginestal RC, Plaza JF, Callejo JM, Rodríguez-Espinosa N, Fernández-Ruiz LC, Masjuán J. Bilateral optic neuritis and Guillain-Barré syndrome following an acute Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Neurol. 2004;251(6):767–768. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lolekha P, Phanthumchinda K. Optic neuritis in a patient with Miller-Fisher syndrome. J Med Ass Thai Chot Thangphaet. 2008;91(12):1909–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomiyasu K, Ishiyama M, Kato K, Komura M, Ohnuma E, Inamasu J, et al. Bilateral retrobulbar optic neuritis, Guillain-Barré syndrome and asymptomatic central white matter lesions following adult measles infection. Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 2009;48(5):377–381. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robbins MS, Roth S, Swerdlow ML, Bieri P, Herskovitz S. Optic neuritis and palatal dysarthria as presenting features of post-infectious GQ1b antibody syndrome. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111(5):465–466. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neuwirth C, Mojon D, Weber M. GD1a-associated pure motor Guillain-Barré syndrome with hyperreflexia and bilateral papillitis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2010;11(3):114–119. doi: 10.1097/CND.0b013e3181cc21de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biotti D, Boucher S, Ong E, Tilikete C, Vighetto A. Optic neuritis as a possible phenotype of anti-GQ1b/GT1a antibody syndrome. J Neurol. 2013;260(11):2890–2891. doi: 10.1007/s00415-013-7094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamotte G, Laballe R, Dupuy B. Bilateral eyelid retraction, loss of vision, ophthalmoplegia: an atypical triad in anti-GQ1b syndrome. Revue Neurologique. 2014;170(6–7):469–470. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benedetti L, Franciotta D, Beronio A, Delucchi S, Capellini C, Del Sette M. Meningoencephalitis-like onset of post-infectious AQP4-IgG-positive optic neuritis complicated by GM1-IgG-positive acute polyneuropathy. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 2015;21(2):246–248. doi: 10.1177/1352458514524294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Incecik F, Herguner OM, Besen S, Yar K, Altunbasak S. Guillain-Barré syndrome with hyperreflexia and bilateral papillitis in a child. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2016;11(1):71–73. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.181264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baheerathan A, Ross Russell A, Bremner F, Farmer SF. A rare case of bilateral optic neuritis and Guillain-Barré syndrome post Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Neuro-ophthalmology (Aeolus Press) 2017;41(1):41–47. doi: 10.1080/01658107.2016.1237975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dayal AM, Kimpinski K, Fraser JA. Optic neuritis in Guillain-Barre syndrome. The Canadian J Neurol Sci Le J Canadien des Sci Neurol. 2017;44(4):449–451. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2016.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.KobawakaGamage KK, Fernando H. Leptospirosis complicated with Guillain Barre syndrome, papillitis and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura; a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):691. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3616-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wen HJ. Acute bilateral vision deficit as the initial symptom in Guillain-Barre syndrome: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(3):2712–2716. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsunaga M, Kodama Y, Maruyama S, Miyazono A, Seki S, Tanabe T, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome and optic neuritis after Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Brain Develop. 2018;40(5):439–442. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao T, Deng Y, Ding Y, Zhang R, Zhou C, Lin W. Anti-GQ1b antibody syndrome presenting with visual deterioration as the initial symptom: a case report. Medicine. 2020;99(4):e18805. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000018805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henderson R, Gilroy J, Huber P, Meyer JS. Landry-Guillain-Barr'e syndrome with cranial nerve involvement (polyneuritis cranialis) Harper Hosp Bull. 1964;22:59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banerji NK. Acute polyneuritis cranialis with total external ophthalmoplegia and areflexia. Ulst Med J. 1971;40(1):14–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McFarland HR. Polyneuritis cranialis as the sole manifestation of the Guillain-Barré syndrome. Mo Med. 1976;73(5):227–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamashita H, Koga M, Morimatsu M, Yuki N. Polyneuritis cranialis related to anti-GT1 a IgG antibody. J Neurol. 2001;248(1):65–66. doi: 10.1007/s004150170273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lyu RK, Chen ST. Acute multiple cranial neuropathy: a variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome? Muscle Nerve. 2004;30(4):433–436. doi: 10.1002/mus.20136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pavone P, Incorpora G, Romantshika O, Ruggieri M. Polyneuritis cranialis: full recovery after intravenous immunoglobulins. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;37(3):209–211. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edvardsson B, Persson S. Polyneuritis cranialis presenting with anti-GQ1b IgG antibody. J Neurol Sci. 2009;281(1–2):125–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.02.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu JY, Jung HY, Kim CH, Kim HS, Kim MO. Multiple cranial neuropathies without limb involvements: Guillain-Barre syndrome variant? Ann Rehabil Med. 2013;37(5):740–744. doi: 10.5535/arm.2013.37.5.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dosi R, Ambaliya A, Patel N, Shah M, Patell R. Acute multiple cranial neuropathy: an oculopharyngeal variant of Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Australas Med J. 2014;7(9):376–378. doi: 10.4066/amj.2014.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim JK, Kim BJ, Shin HY, Shin KJ, Nam TS, Oh J, et al. Acute bulbar palsy as a variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Neurology. 2016;86(8):742–747. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000002256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pellegrini F, Wang M, Romeo N, Lee AG. Bilateral sixth nerve palsy and nasal voice in two sisters as a variant of Guillan-Barré syndrome. Neuro-ophthalmology (Aeolus Press) 2018;42(5):306–308. doi: 10.1080/01658107.2017.1420085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wakerley BR, Hamada S, Tashiro K, Moriwaka F, Yuki N. Overlap of acute mydriasis and acute pharyngeal weakness associated with anti-GQ1b antibodies. Muscle Nerve. 2018;57(1):E94–E95. doi: 10.1002/mus.25767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ju H, Im K, Roh H. A case of polyneuritis cranialis with the initial symptom of isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy. J Clin Neurol (Seoul, Korea) 2020;16(4):702–703. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2020.16.4.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arakawa M, Yamazaki M, Toda Y, Ozawa A, Kimura K. An oculopharyngeal subtype of Guillain-Barré syndrome sparing the trochlear and abducens nerves. Internal Med (Tokyo, Japan) 2020;59(9):1215–1217. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.3395-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Assini A, Benedetti L, Di Maio S, Schirinzi E, Del Sette M. New clinical manifestation of COVID-19 related Guillain-Barrè syndrome highly responsive to intravenous immunoglobulins: two Italian cases. Neurol Sci : official J Italian Neurol Soc Italian Soc Clin Neurophys. 2020;41(7):1657–1658. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04484-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blech B, Christiansen M, Asbury K, Orenstein R, Ross M, Grill M. Polyneuritis cranialis after acute tularemia infection: a case study. Muscle Nerve. 2020;61(1):E1–e2. doi: 10.1002/mus.26725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.