Abstract

The present work reports the fabrication of ultra-high strength microsand proppants (100 mesh) through a polymer nanocomposite dual coating approach and gives insight into their thermo-mechanical reinforcements. The dual coating can be of 3D-cross-linked poly(styrene-methyl methacrylate)/divinylbenzene) (PS-PMMA/DVB) porous network and thermally cross-linked epoxy with graphene nanosheets. The inner layer of PS-PMMA/DVB was prepared using bulk polymerization of styrene (S) and methyl methacrylate (MMA) at 70 °C with a free radical initiator azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN). The outer layer was prepared by mixing epoxy resin, a cross-linker, and commercial graphene (CG) followed by thermally curing the mixture. The dual-coated microsand proppants exhibited enhanced mechanical characteristics of elastic modulus (E) as high as 7.78 GPa, hardness (H) of 0.35 GPa, and fracture toughness (Kc) of 3.19 MPa m1/2 along with largely improved thermal properties. Moreover, the dual-coated microsand proppants exhibit a very high-stress resistance up to 14000 psi, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the highest stress resistance value attained for the modified sand-based proppants so far.

Keywords: Microsand proppants, Polymer networks, Nanocomposites, Epoxy, Graphene, Hydraulic fracturing

Microsand proppants; Polymer networks; Nanocomposites; Epoxy; Graphene; Hydraulic fracturing.

1. Introduction

Proppant is a crucial material that helps keep the hydraulic fractures open; which allows the continuous extraction of hydrocarbons from the formations [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. Frac sand is the most common type of proppant used in the oil and gas industry [5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. However, due to their brittle properties, they are only used in wells with relatively low pressure [14, 15, 16]. The frac sand can only tolerate up to 6000 psi closure stress and above this value the sand cracks and generates fine particles that could flow back into the formations, hence lowering the hydrocarbon production rate. To avoid this problem, sand particles must be suitably modified to withstand higher pressures [13, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21]. In this context, numerous surface modification techniques and coating methods were then used to improve the stress tolerance and flow rate of frac sand at the wellbore [10, 13, 19, 22, 23, 24]. The advantages of these coatings include trapping the broken grains in the coated layer and therefore alleviating the proppant flow-back into the bore well [17, 25, 26, 27].

One of the most common approaches to surface modification of sand particles is by using resins [28]. For instance, epoxy, vinyl, polyurethane, polyesters, and furan are the widely employed resins to coat the frac sand. Due to their chemical inertness and higher mechanical characteristics [20, 21, 29, 30, 31]. Despite the advantages of surface modification of frac sand with resin, it can only increase its stress resistance by up to 7500 psi [28]. Moreover, when the resin-coated proppants (RCPs) are employed in high-temperature wells, they tend to aggregate due to softening of the resin layer and adversely affect the well's conductivity [32, 33, 34]. These long-standing drawbacks of RCPs are partly resolved by coating the frac sand with polymer nanocomposites [35, 36, 37]. Due to their mechanical properties, the combination of these materials with other nanofillers such as carbon nanotube, graphene, and graphene oxide (GO) has been able to improve the thermo-mechanical stabilities of the proppants [28, 35, 38, 39].

For instance, CNT and GO incorporated urethane modified RCPs showed significant enhancement in the stress resistance values [31]. In the continued efforts of improving the stress resistance of RCPs, we have recently introduced a multiple polymer nanocomposite coating approach onto the macro frac sand particles (70/40 mesh sized and derived from Saudi Arabian deserts) [40, 41]. Previously, we developed a unique dual-coating technique for polymer nanocomposites using CG and an epoxy layer on macrosand (40/70 mesh) particles. Notably, the results of the study revealed that the modified macrosand with polystyrene-polymethyl methacrylate copolymer/graphene composite and epoxy/graphene composite exhibited a stress resistance of 10000 psi. On the other hand, the modified macrosand with porous copolymer network and epoxy/graphene composite showed a resistance of up to 12000 psi [40, 41].

Herein, we want to investigate the influence of the size of sand particles on the mechanical characteristics of the dual-coated sand proppants. Through the use of microsand particles with a size of 100 mesh, polymer nanocomposites dual-coated sand proppants were prepared. Their thermo-mechanical properties and the ultimate stress resistance values were also investigated in comparison to macrosand particles with a size of 70/40 mesh. Furthermore, proppants with reduced specific gravity values are highly preferred as they can be easily suspended in fracturing fluid. Therefore, this work also aims to develop a proppant with high-stress resistance and low specific gravity values.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Styrene (Mw = 104.15 g/mol, >99% purity), and methyl methacrylate (Mw = 100.12 g/mol, 99% purity) monomers were procured from Aldrich. Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) was purchased from Aldrich. The microsand (100 mesh), epoxy resin (Jana, Razeen LR 1100), and curing agent (Jana, Raceencure 931) is provided by Saudi Aramco. The CG (XGnP) was obtained from XG Sciences.

2.2. Preparation of dual polymer nanocomposite layers

The 3D-PS-PMMA/DVB layer was prepared by following our previous methods [40, 41]. Briefly, 1:1 wt% of S and MMA and DVB (10 wt%) were mixed. Followed by adding 0.01 wt% of the initiator to the mixture and the temperature was raised to 70 °C. After the polymerization is completed, PS-PMMA/DVB films were washed with hot ethanol and dried. The preparation of the Epoxy-CG nanocomposite film was carried out by mixing epoxy resin and curing agent in 4:1 wt% along with 0.1 wt% of CG. The mixture was then vigorously stirred and subsequently cured at 150 °C for 5 min. The dual (3D-PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) nanocomposite layer was prepared by a layer-by-layer preparation film of respective individual films.

2.3. Preparation of dual-coated microsand proppants

The dual-coated microsand proppant was prepared by using 100 mesh sand particles with a sequential coating of 3D-PS-PMMA/DVB and Epoxy-CG nanocomposite. The microsand particles were initially mixed with a mixture of co-monomers (S and MMA) along with an initiator (AIBN) and subsequently heated to form the first porous polymer layer. Then, the first layer of coated microsand particles was added with a mixture of epoxy, cure, and CG and heated to 150 °C for the second layer of curing. As an exemplary system, 300 g of microsand particles were mixed with 10 ml of the co-monomer mixture (5 ml of S and MMA each) along with 1 ml of DVB and 0.01 g of AIBN under constant stirring and subsequently polymerized at 70 °C for 12 h. Then, the 3D-PS-PMMA/DVB coated microsand particles (300 g) were mixed with 10 ml of resin (8 ml of epoxy and 2 ml of resin cure) and cured at 150 °C for 5 min. The proppants are prone to form clumps when mixed with resin and subsequent curing process at high-temperature. Yet, the clump formation can be successfully overcome by the continuous stirring of proppant particles during mixing and curing at high-temperature conditions. The polymer and resin dual coating film thicknesses were controlled with the amount of monomer mixture added to the microsand and the amount of the resin added to the polymer-coated microsand proppants and the stirring rate while mixing each component with micorsand particles. The microsand particles are added to a maximum amount of either monomer mixture or resin until there's no clump formation during the polymerization or resin curing process. Notably, this process is highly suitable for mass production as we have achieved 10 kg of proppants' production in each batch at a laboratory scale.

2.4. Characterizations

The samples were characterized using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR), X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRD), Thermo-Gravimetric Analyses (TGA), nano-indentation, Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM), and crush tests. To measure the FT-IR spectra, the Thermo Scientific Nicolet-iS10 instrument was used. The spectral measurements were carried out in ATR mode within the wave number range of 4000–500 cm−1. To measure the XRD, Rigaku MiniFlex 600 instrument was used. The XRD patterns were obtained using Cu Kα radiation (1.54 A°) in the range of 5–80°. The TGA curves were used to evaluate the degradation temperatures (Tdeg) of the samples using Hitachi STA7200 [[42], [43], [44]]. Elastic modulus (E), and hardness (H), of the samples, are measured by using the Nanointender (NanoTest™ system) using Berkovich indenter. FE-SEM (FEI Inspect S50) was used to monitor the morphologies of the proppant samples. The sample preparation for the SEM observations can be found elsewhere [45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50]. To record the images, an accelerating voltage of 2 kV was applied.

2.5. Crush test

The crush tests for the microsand proppant samples were subjected to a hydraulic load frame that can handle a pressure of 15000 psi. The applied stress for the crush tests ranged from 3000 psi to 14000 psi. The proppants are allowed to crush at a given pressure for 2 min. After the process, the samples were sieved (100 mesh sieve as the size of the fines is typically less than 100 mesh in than size.) for the generated fines and weighed. From the initial weight of the proppants and amount of the generated fines, the fines fine is calculated using Eq. (1).

| (1) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Dual-coated microsand proppants via sequential coating

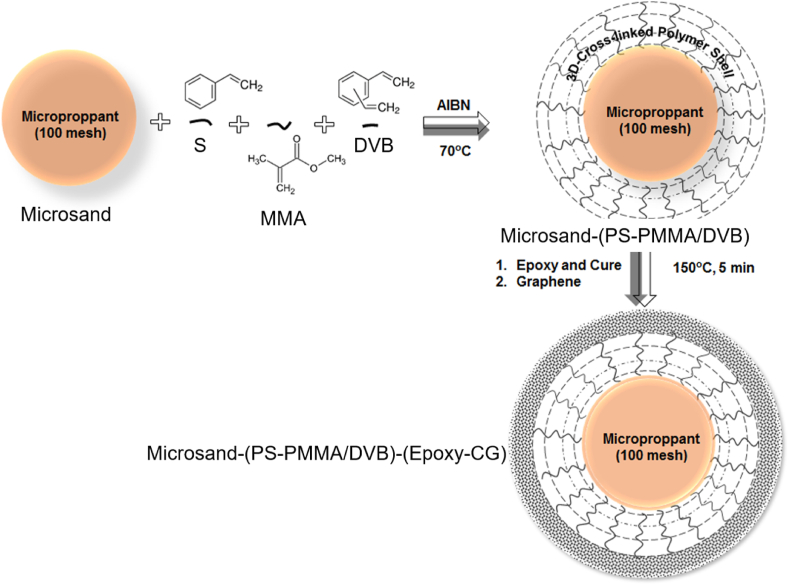

The preparation method of a microsand-(PS-PMMALDVB)-(Epoxy-CG) proppant using two coating layers is shown in Scheme 1. Typically, the first layer of the proppant is prepared by, a well-mixing of microsand with a co-monomer mixture of S and MMA, a cross-linker of DVB and AIBN initiator. After the mixture is sufficiently heated, the AIBN will undergo radical decomposition. The initiator radicals were used to convert the co-monomer and cross-linker molecules to their respective free radicals. Afterward, the co-monomer and cross-linker free radicals are turned into radical donors to other co-monomer and cross-linker molecules. This process led to the random copolymerization between S, MMA, and cross-linking with DVB. This has resulted in a 3D-cross-linked network of PS-PMMA/DVB onto the microsand particles. The detailed mechanism of 3D-porous network formation can be found in our previous reports [41, 51]. The second layer of the proppant is then prepared by mixing the porous polymer network modified microsand proppants with the epoxy resin and a resin cured with CG and then cured at high temperatures for a few minutes.

Scheme 1.

Sequential preparation scheme for dual-coated microsand proppants.

3.2. FE-SEM

The size and the morphology of the microsand-(PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) were then assessed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Figure 1)The FE-SEM images of the samples show that they are more similar to the microsand-(PS-PMMA/DVB) and unmodified microsand samples at different magnifications. The polymer coating is visible from the images as the surfaces of the coated samples appear smooth while that of unmodified samples are rough. As evident from the images the dual-coating unaffected the original morphology of the microsand particles as they retain their original sphericity and roundness of >0.6. The retention of sphericity and roundness of the microsand proppants is vital for their high proppant-pack porosity. The retention of these two features can help improve the flow conductivity of the fluids in the downhole conditions at high temperatures and pressure.

Figure 1.

FE-SEM images of microsand proppants in comparison to unmodified ones at different magnifications.

3.3. FT-IR spectra and XRD patterns

The chemical interaction between the two layers and microsand was demonstrated by FT-IR spectroscopy as shown in Figure 2a. For the microsand sample, the peaks detected at 1082 cm−1 and 1175which cm−1 were assigned to the Si–O–Si bond of sand particles. The peak found at 1632 cm−1 corresponds to H–O–H stretching and peaks around 750 cm−1 correspond to Si–O symmetric stretching. The peak at 3450 cm−1 corresponds to the O–H peak of SiO2 and absorbed moisture. The peaks that are detected at 750 cm−1 were assigned to asymmetric stretching of C–C–O group in MA, and at 1116 cm−1 that corresponds to stretching mode of C–O–C. The peak at 1408 cm−1, and 2916 cm−1 are assigned to bending and stretching modes of the –CH3 group, respectively. The peak at 1646 cm−1 corresponds to stretching mode of C C bond in the PS and the peak at 1758 cm−1 corresponds to C=O in the PMMA. These peaks confirm the successful formation of 3D-PS-PMMA/DVB layer onto the microsand. Similarly, the peaks that are identified at 2958 cm−1 and 2865 cm−1 (corresponds to C–H stretch vibrations of –CH2) correspond to graphene in the second nanocomposite layer. The stretching mode of C O and C–O of epoxy were detected at 1750 and 1450 cm−1 respectively. The measured FT-IR spectra indicated that the microsand samples are well coated with the respective polymer network and nanocomposites. The successful interaction between microsand and (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) was demonstrated by FT-IR spectroscopy as shown in Figure 2a. The appearance of peaks at 1646, and 1750 cm−1 are indicative of the successful formation of the 3D-PS-PMMA/DVB layer on the microsand particles.

Figure 2.

(a) and (b) FT-IR spectra, XRD patterns of coated microsand proppants in comparison to unmodified microsand respectively.

XRD patterns for unmodified microsand, PS-PMMA/DVB (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG), and epoxy-coated samples are shown in Figure 2b. The peaks at 21°, 26.5°, 42°, 44°, 51°, 58°, 68°, and 77° and those peaks correspond quartz phase of SiO2. For the unmodified microsand, there were two major peaks observed one is at 21° (100) and the other is at 26.5°. When the PS-PMMA/DVB is coated with sand, the intensity of the 100 peaks is slightly reduced. It should be noted that the 100 peaks' intensity is lower for the samples with the epoxy composites onto the 3D-PS-PMMA/DVB layer. Similarly, the other peaks were also observed to decrease with the coating dual lateral-layer while the intensity of the 101 peaks remained almost the same. This reduction in the minor peaks’ intensities is attributed to the well surface coverage of the dual-layers onto the microsand surfaces. Similarly, the decrease in the peak intensity of 100 of the dual coatings suggests good surface coverage of the proppants. At the same time, the constant intensity of the 101 peaks indicated that the core sand particles remain unchanged.

3.4. Thermal and nanomechanical properties

The TGA results of unmodified microsand and microsand modified with PS-PMMA/DVB, (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG), and epoxy coating layers are shown in Figure 3a. The degradation temperature (Tdeg) of the coating layers was determined and the values are summarized in Table 1. Tdeg values were evaluated using differential thermal curves (DTA) for the samples that are showing clear degradation steps while for the samples that show no clear degradation, the temperature at which 50% of the material decomposition is attained was considered to be its Tdeg [52]. As shown in Figure 3a, the Tdeg for microsand-PS-PMMA/DVB is determined to be 350 °C while that of microsand-(PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) was found to increase to 370 °C. At the same time, the Tdeg for microsand-epoxy is found to be only 345 °C The observed thermal stability values are found to be much higher than that of various other resin systems including furan [53], phenolic [54], polyurethane [33, 53], polyurethane-carbon nanostructure composites [38] reported in the literature (Table 1). This thermal stability enhancement of the dual-coated microsand proppants can be accredited to the improved thermal stability of the Epoxy-CG composite layer which is in turn credited to the thermal stability of graphene nanosheets. A synergistic increase in the Tdeg was observed with the Epoxy-CG composite layer along with the 3D-PS-PMMA/DVB layer onto microsand particles. This particular enhancement in the thermal stability of the dual-coated microsand proppants is indicative of their potential applicability under high-temperature downhole conditions.

Figure 3.

(a) TGA curves for coated microsand proppants in comparison to unmodified microsand. (b). E and H values of different coating layers.

Table 1.

Summary of Tdeg and Nano-mechanical values of coated microsand proppants.

| Thermal stability |

Nano-mechanical of dual-layer |

Ref. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tdeg (°C) | E (GPa) | H (GPa) | ||

| (PS-PMMA/DVB) | 350 | 7.24 | 0.298 | This work |

| (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) | 370 | 7.78 | 0.35 | This work |

| Epoxy | 345 | 4.23 | 0.21 | This work |

| Furan Resin | 190 | – | – | [53] |

| Polyurethane | 121 | – | – | [33, 53] |

| Polyurethane-Multiwalled-Carbon Nanotube (MWCNT) | 280 | – | – | [38] |

| Polyurethane-MWCNT-Graphene | 300 | – | – | [37] |

| Phenolic Resin | 147 | – | – | [54] |

Nano-indentation technique was used to determine the E and H for the coating layers. The calculated E and H values of PS-PMMA/DVB, (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG), and Epoxy, are shown in Figure 3b. E and H values are measured to be 7.2 and 0.298 GPa, respectively for PS-PMMA/DVB matrix. These values are much higher than that of the linear PS-PMMA copolymer matrix [41, 51]. These enhancements in the nanomechanical properties are accredited to the 3D-nanonetwork formation of PS-PMMA/DVB. Furthermore, the E and H values for the dual-layer of (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) are found to be 7.78 GPa and 0.35 GPa respectively that is even higher than that of PS-PMMA/DVB and epoxy alone. Note that the E and H values for the Epoxy layer are only 4.23 and 0.21 GPa, respectively. The synergistic nanomechanical enhancement in the dual-layer of (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) can be due to the enhanced surface interaction of the porous layer of PS-PMMA/DVB with the Epoxy-CG bulk layer. The Epoxy-CG layer would infuse into the porous PS-PMMA/DVB layer at an elevated temperature while coating and thus increase the mechanical stability of the dual-coated microsand proppants. These results are in line with the thermal stability of the microsand proppants as well. In addition, this increment in the nano-mechanical characteristics can also be attributed to the enhanced crosslinking of CG to the epoxy matrix. Based on obtained results, the dual-layer of (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) would be the ideal modification for the microsand based proppants for HT-HP conditions. The current study reports the mechanical data that are measured at room temperature while it is important to study the effect of temperature on the mechanical properties to evaluate the practical applicability of the coated proppants in High-Temperature High-Pressure (HT-HP) downhole conditions. Our initial study showed that the dual-coated microproppants retained their mechanical properties up to 150 °C under high pressure and high salinity conditions.

Fracture toughness (Kc) is yet another parameter that indicates the resistance of a material to a fracture when enduring a crack. The Kc can be calculated using Eq. (2) [55].

| (2) |

Where in αi is a constant and that is intender specific. For Berkovich intender, the value is 0.016, P is peak indentation load and C is the cracking length. The calculated Kc value for the PS-PMMA/DVB layer is 2.21 MPa⋅m1/2. Very interestingly, this value is considerably higher than that of PS-PMMA which is only 1.80 MPa⋅m1/2 [41]. This increment can be accredited to the 3D network of the PS-PMMA/DVB. Meanwhile, it can be noted that the Kc values for the PS, PMMA, Epoxy-CG, and Epoxy layers are only 1.00 MPa⋅m1/2, and 1.08 MPa⋅m1/2, 1.90 MPa⋅m1/2, and 0.6 MPa⋅m1/2, respectively. The higher Kc value of Epoxy-CG in comparison to Epoxy can be due to the shearing effects of the graphene within the Epoxy. Remarkably, the Kc of the dual-coating layers (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) is found to be 3.19 MPa⋅m1/2. This value is approximately three folds higher in comparison to that of sandstone (1.27 MPa⋅m1/2) [41]. Based on these results, it can be clearly said that the dual-layer of highly toughened 3D-(PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) showed a synergistic increment in the coating's fracture toughness.

3.5. Crush tests

Figure 4 shows crush test results of the dual-coated microsand proppants as a function of closure stress (3000–14,000 psi) in comparison to the unmodified and mono-layer PS-PMMA/DVB and Epoxy coated counterparts. As shown in Figure 4a, the unmodified microsand produced 20% fine at an applied stress of 10,000 psi. Whereas for the PS-PMMA/DVB mono-layer coated microsand, fine production was considerably reduced to 15%. This observation is serving as direct evidence for the increased stress tolerance for the coated microsand. Furthermore, when the dual-coating of (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy), was applied to the microsand, the fine production reached a minimum of only 2.0% while with a dual nanocomposite coating of (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG), the fine production is only 1.0% (10,000 psi). As evident from Figure 4a and b, the dual-coated (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) exhibited a maximum stress resistance of 14,000 psi as the fine production of only <5 wt%. The very high closure stress resistance of the dual-coated microsand proppants is accredited to the synergistic mechanical reinforcement of the dual-coated layers. These observations are in line with the nanomechanical and fracture toughness characteristics of the dual-coated microsand proppants.

Figure 4.

(a) % fine production of microsand proppant samples in comparison to unmodified and mono-layered counterparts at closure stress of 10000 psi. (b) % fine production of microsand-((PS-PMMA/DVB-(Epoxy-CG)) sample as a function of closure stress from 3000 psi to 14000 psi.

In our previous work, it was shown that the first layer of (PS-PMMA/DVB) is a 3D-crosslinked microporous network with an approximate pore size of 2 nm [56]. Whereas the second coating layer of epoxy-CG composite is bulk and non-porous. Therefore, coating a bulk layer (epoxy-CG) onto a porous networked layer (PS-PMMA/DVB) resulted in an interfusion of the two coating layers. This has resulted in the improved stress resistance of the microsand proppants. It is clear that the prepared microsand-(PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) proppants with a stress resistance of 14000 psi would be potential candidates for hydraulic fracturing operations under HT-HP conditions.

Table 2 summarizes different coated sand proppants with their respective stress resistance values and specific gravity values. In proppant industries, materials with lower specific gravity are preferred so that they can easily be suspended in fracturing fluids. The specific gravity of the microsand-(PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) proppant is found to be 1.29 g/cm3, while that of the unmodified microsand is 1.50 g/cm3. The dual-coated microsand proppants with a decreased specific gravity are an obvious advantage to be employed in fracturing fluids with a lower settling rate. Taking into consideration of the lower specific gravity and extremely high-stress resistance value, the dual-coated (3D-PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) microsand proppants can be a potential alternative to the traditional RCPs (resin-coated proppants) in the HT-HP wells. Interestingly, the overall cost involved in the dual-coated proppants preparation is ranging from $1- $3/Kg which makes the reported method highly competitive in comparison to other similar products in the market. Nevertheless, the current method is limited to two-step fabrication and proppants are necessarily to be pre-made to inject into the well.

Table 2.

Summary of stress resistance for various coated sand proppants in comparison to RCPs.

4. Conclusion

The dual-coated microsand proppants with 3D-PS-PMMA/DVB and Epoxy-CG composite layers were successfully prepared. The FE-SEM images clearly showed that the original morphology of the microsand is retained for the dual-coated proppants. As evident from the FT-IR spectra and XRD patterns, dual-coated microsand proppants are successfully prepared. The TGA results revealed that the thermal stability of the (PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) is as high as 370 °C. Moreover, the Elastic modulus, Hardness, and fracture toughness values for the dual-coated layers are also found to be as high as 7.78 GPa, 0.35 GPa, and 3.19 MPa m1/2 respectively. More interestingly, the stress resistance of the dual-layer of (3D-PS-PMMA/DVB)-(Epoxy-CG) coated microsand proppants reached up to 14000 psi with a fine production of only 5.2% with a decreased specific gravity of 1.29 g/cm3. To the best of our knowledge, this is the highest reported value so far for the coated sand-based proppants. In addition, preliminary results showed that the dual-coated microsand proppants have appreciable suspension ability in the frac fluid and exhibit good conductivity. Therefore, these thermo-mechanically reinforced dual-coated microsand particles with a very high-stress resistance and reduced specific gravity values can be potential proppants in hydraulic fracturing operations in HT-HP wells.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Mohan Raj Krishnan: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Haneen Omar: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Yazeed Aldawsari, Bayan Al Shikh Zien, Tasneem Kattash: Performed the experiments.

Wengang Li, Edreese H. Alsharaeh: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the continued support from AlFaisal University and its Office of Research.

Contributor Information

Wengang Li, Email: wengang.li@aramco.com.

Edreese H. Alsharaeh, Email: ealsharaeh@alfaisal.edu.

References

- 1.Belyadi H., Fathi E., Belyadi F. In: Hydraulic Fracturing in Unconventional Reservoirs. Belyadi H., Fathi E., Belyadi F., editors. Gulf Professional Publishing; Boston: 2017. Chapter six - proppant characteristics and application design; pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Campos V., Sansone E.C., Silva G.F.B.L. Hydraulic fracturing proppants. Cerâmica. 2018;64:219–229. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y. The university of Texas at Austin; 2006. Settling and Hydrodynamic Retardation of Proppants in Hydraulic Fractures. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallegos T.J., Varela B.A. US Geological Survey Reston; VA: 2015. Trends in Hydraulic Fracturing Distributions and Treatment Fluids, Additives, Proppants, and Water Volumes Applied to wells Drilled in the United States from 1947 through 2010: Data Analysis and Comparison to the Literature. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hellmann J.R., Scheetz B.E., Luscher W.G., Hartwich D.G., Koseski R.P. Proppants for shale gas and oil recovery. Am. Ceram. Soc. Bull. 2014;93:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jianguang W., Xiaofeng Z., Xiaofei F., Yinghe C., Fan B. Experimental investigation of long-term fracture conductivity filled with quartz sand: mixing proppants and closing pressure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:32394–32402. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fink J.K. In: Hydraulic Fracturing Chemicals and Fluids Technology. Fink J.K., editor. Gulf Professional Publishing; 2013. Chapter 18 - proppants; pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard G.C., Fast C.R. SOCIETY OF PETROLEUM ENGINEERS OF AIME; NEW YORK: 1970. Hydraulic Fracturing; p. 210. 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Poollen H., Tinsley J.M., Saunders C.D. Hydraulic fracturing-fracture flow capacity vs well productivity. Transactions of the AIME. 1958;213:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu L., Zhang G., Ge J., Liao K., Jiang P., Pei H., Li X. Surface modified proppants used for porppant flowback control in hydraulic fracturing. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016;507:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kothamasu R., Choudhary Y.K., Kurubaran M.K. OnePetro; 2012. Comparative Study of Different Sand Samples and Potential for Hydraulic-Fracturing Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goyal S., Raghuraman A., Aou K., Aguirre-Vargas F., Medina J.C., Tan R., Hickman D. OnePetro; 2017. Smart Proppants with Multiple Down Hole Functionalities. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aolin H., Jibal C. Recent advances in coated proppants and its flowback control technologies. Drill. Prod. Technol. 1999;3 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tschapek M., Wasowksi C., Falasca S. Character and change in the hydrophilic properties of quartz sand. Z. für Pflanzenernährung Bodenkunde. 1983;146:295–301. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gidley J., Penny G., McDaniel R. Effect of proppant failure and fines migration on conductivity of propped fractures. SPE Prod. Facil. 1995;10:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun H., He B., Xu H., Zhou F., Zhang M., Li H., Yin G., Chen S., Xu X., Li B. Experimental investigation on the fracture conductivity behavior of quartz sand and ceramic mixed proppants. ACS Omega. 2022;7:10243–10254. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c06828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoveidavianpoor M., Gharibi A. Application of polymers for coating of proppant in hydraulic fracturing of subterraneous formations: a comprehensive review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015;24:197–209. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fjaestad D., Tomac I. Experimental investigation of sand proppant particles flow and transport regimes through narrow slots. Powder Technol. 2019;343:495–511. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao W., He S., Jie J. Evaluation on long-term flow conductivity of coated proppants. Nat. Gas. Ind. 2007;27:100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman L.R., Terracina J.M., McCabe M.A., Nguyen P.D. Vol. 7. 1992. Application of Curable Resin-Coated Proppants, SPE-20640-PA; pp. 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gawish A.A., Elsayed S.K., Elgibaly A.A., Heikal M.A. Comprehensive study on improving proppant flow-back control using resin coated and rod-shaped proppant in Egyptian fractured wells. Petrol. Coal. 2020;62 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen P., Dewprashad B., Weaver J. Society of Petroleum Engineers; 1998. A New Approach for Enhancing Fracture Conductivity. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pangilinan K.D., de Leon A.C.C., Advincula R.C. Polymers for proppants used in hydraulic fracturing. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2016;145:154–160. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabatabaei M., Dahi Taleghani A., Cai Y., Santos L., Alem N. 2020. Surface Modification of Proppant Using Hydrophobic Coating to Enhance Long-Term Production, SPE-196067-PA; p. 12. Preprint. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen P.D., Weaver J.D. Chemical hooks keep proppant in place. Oil Gas J. 1997;95 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shrey S., Mokhtari M., Farmer W.R. SPE-191826-18ERM-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers; SPE: 2018. Modifying proppant surface with nano-roughness coating to enhance fracture conductivity; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raysoni N., Weaver J.D. SPE-150669-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers; SPE: 2012. Long-Term proppant performance; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michael F.M., Krishnan M.R., Li W., Alsharaeh E.H. A review on polymer-nanofiller composites in developing coated sand proppants for hydraulic fracturing. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020;83 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dewprashad B., Abass H.H., Meadows D.L., Weaver J.D., Bennett B.J. SPE-26523-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, SPE; 1993. A method to select resin-coated proppants; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan F., Li F.-X., Tian S.-C., Sheng M., Khan W., Shi A.-P., Zhou Y., Xu Q. Hydrophobic epoxy resin coated proppants with ultra-high self-suspension ability and enhanced liquid conductivity. Petrol. Sci. 2021;18:1753–1759. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian T., Muhsan A., Htwe L., Mohamed N., Hussein O. IOP Publishing; 2020. Urethane Based Nanocomposite Coated Proppants for Improved Crush Resistance during Hydraulic Fracturing. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palisch T., Duenckel R., Wilson B. New technology yields ultrahigh-strength proppant. SPE Prod. Oper. 2015;30:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horadam W., Venkat N., Tran T., Bai L., Josyula K., Mehta V. Leaching studies on Novolac resin-coated proppants-performance, stability, product safety, and environmental health considerations. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018;135 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duenckel R.J., Barree R.D., Drylie S., O’Connell L.G., Abney K.L., Conway M.W., Moore N., Chen F. SPE-187451-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers, SPE; 2017. Proppants- what 30 Years of study has taught us; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haque M.H., Saini R.K., Sayed M.A. OTC-29572-MS, Offshore Technology Conference. OTC; 2019. Nano-composite resin coated proppant for hydraulic fracturing; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manogran J.S. IRC; 2021. Ultra-Thin Nanocomposite Layers Coated Proppant for Improved Compression Strength. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alzanam A.A.A., Muhsan A.S. OnePetro; 2021. Resin-based Nanocomposites Coated Proppants as Scale Inhibitor Carrier and Slowly Releasing Container. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alzanam A.A.A., Ishtiaq U., Muhsan A.S., Mohamed N.M. A multiwalled carbon nanotube-based polyurethane nanocomposite-coated sand/proppant for improved mechanical strength and flowback control in hydraulic fracturing applications. ACS Omega. 2021;6:20768–20778. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c01639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramlan A.S., Zin R.M., Abu Bakar N.F., Othman N.H., Jarni H.H., Hussain M.H., Mohd Najib N.I., Zakran M.Z. Characterisation of graphene oxide-coated sand for potential use as proppant in hydraulic fracturing. Arabian J. Geosci. 2022;15:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krishnan M.R., Aldawsari Y., Michael F.M., Li W., Alsharaeh E.H. Mechanically reinforced polystyrene-polymethyl methacrylate copolymer-graphene and Epoxy-Graphene composites dual-coated sand proppants for hydraulic fracture operations. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2021;196 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krishnan M.R., Aldawsari Y., Michael F.M., Li W., Alsharaeh E.H. 3D-Polystyrene-polymethyl methacrylate/divinyl benzene networks-Epoxy-Graphene nanocomposites dual-coated sand as high strength proppants for hydraulic fracture operations. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021;88 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Almohsin A., Michal F., Alsharaeh E., Bataweel M., Krishnan M. SPE-198664-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers; Dubai, UAE: 2019. Self-healing PAM composite hydrogel for water shutoff at high temperatures: thermal and rheological investigations; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keishnan M.R., Michael F.M., Almohsin A.M., Alsharaeh E.H. OTC-30123-MS. Offshore Technology Conference, OTC; 2020. Thermal and rheological investigations on N,N’-Methylenebis acrylamide cross-linked polyacrylamide nanocomposite hydrogels for water shutoff applications; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krishnan M., Michal F., Alsoughayer S., Almohsin A., Alsharaeh E. SPE-198033-MS. Society of Petroleum Engineers; Mishref, Kuwait: 2019. Thermodynamic and kinetic investigation of water absorption by PAM composite hydrogel; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chien Y.-C., Huang L.-Y., Yang K.-C., Krishnan M.R., Hung W.-S., Tsai J.-C., Ho R.-M. Fabrication of metallic nanonetworks via templated electroless plating as hydrogenation catalyst. Emerg. Mater. 2021;4:493–501. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krishnan M.R., Lu K., Chiu W., Chen I., Lin J., Lo T., Georgopanos P., Avgeropoulos A., Lee M., Ho R. Directed self-assembly of star-block copolymers by topographic nanopatterns through nucleation and growth mechanism. Small. 2018;14 doi: 10.1002/smll.201704005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krishnan M.R., Chien Y.-C., Cheng C.-F., Ho R.-M. Fabrication of mesoporous polystyrene films with controlled porosity and pore size by solvent annealing for templated syntheses. Langmuir. 2017;33:8428–8435. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b02195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krishnan M.R., Samitsu S., Fujii Y., Ichinose I. Hydrophilic polymer nanofibre networks for rapid removal of aromatic compounds from water. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:9393–9396. doi: 10.1039/c4cc01786b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michael F.M., Krishnan M.R., Fathima A., Busaleh A., Almohsin A., Alsharaeh E.H. Zirconia/graphene nanocomposites effect on the enhancement of thermo-mechanical stability of polymer hydrogels. Mater. Today Commun. 2019;21 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samitsu S., Zhang R., Peng X., Krishnan M.R., Fujii Y., Ichinose I. Flash freezing route to mesoporous polymer nanofibre networks. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2653. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krishnan M.R., Aldawsari Y.F., Alsharaeh E.H. Three-dimensionally cross-linked styrene-methyl methacrylate-divinyl benzene terpolymer networks for organic solvents and crude oil absorption. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tiwari A., Hihara L. Thermal stability and thermokinetics studies on silicone ceramer coatings: Part 1-inert atmosphere parameters. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2009;94:1754–1771. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liang F., Sayed M., Al-Muntasheri G.A., Chang F.F., Li L. A comprehensive review on proppant technologies. Petroleum. 2016;2:26–39. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zoveidavianpoor M., Gharibi A., bin Jaafar M.Z. Experimental characterization of a new high-strength ultra-lightweight composite proppant derived from renewable resources. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2018;170:1038–1047. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anstis G.R., Chantikul P., Lawn B.R., Marshall D.B. A critical evaluation of indentation techniques for measuring fracture toughness: I, direct crack measurements. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1981;64:533–538. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krishnan M.R., Aldawsari Y.F., Alsharaeh E.H. Three-dimensionally cross-linked styrene-methyl methacrylate-divinyl benzene terpolymer networks for organic solvents and crude oil absorption. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020 n/a. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krishnan M.R., Aldawsari Y., Michael F.M., Li W., Alsharaeh E.H. Mechanically reinforced polystyrene-polymethyl methacrylate copolymer-graphene and Epoxy-Graphene composites dual-coated sand proppants for hydraulic fracture operations. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2021;196 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.