Abstract

Organizational reputation can be seriously damaged after a self-inflicted or externally induced crisis. Studies have tested the restoring and protective effects of various crisis communication strategies. For this paper, we compared the effects on organizational reputation dependent on (a) crisis type and (b) crisis communication strategy used. We combined six strategies in a stepwise manner, showing which ones are most effective in which type of crisis in an experimental online setting. Respondents were randomly assigned to questionnaires with varying combinations of (b) in a different sequence of (a) rating the organization for three points in time. Using a diverse sample, we show that organizational reputation improves significantly only after combining at least five strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1057/s41299-022-00156-6.

Keywords: Organizational reputation, Crisis communication, Crisis management, Experiment

Introduction

Just as society, many organizations experience being in an externally induced crisis at the moment. While for some the situation is aggravated by internal shortcomings or boundary conditions that now become critical, all must communicate to their stakeholders. These are shareholders, clients, prospective clients, employees, and members of the organizational networks and the local community an enterprise is situated in. A crisis not only influences an organization’s current situation, but also its long-term survival, which makes the right reactional choice and communication strategies crucial (Coombs and Holladay 2002). Since the effectiveness of the crisis communication strategies has received equivocal support in research (for a qualitative overview, see Table 1 below), further investigations are called for (Tkalac Verčič et al. 2019). The need for this may be heightened as the public becomes more demanding, regulations more intense and communication quicker due to digitalization (Yakut and Bayraktaroglu 2021). Testing which combination of six available communication strategies best (re-)improves organizational reputation in (a) self-inflicted and (b) externally induced crises is the aim of the current paper. Using a diverse sample, we test this as a stage model in an experimental online setting for two organizations in different industries. To our knowledge, this is one of the most comprehensive tests done so far.

Table 1.

The effectiveness of corporate responses during a crisis: a qualitative overview

| Publication | Objective | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Dean (2004) | Testing the impact of the reputation for social responsibility on overall regard of the customers | Reacting in a fair and compassionate way leads to higher regard than not doing so or trying to avoid taking blame. |

| Dardis and Haigh (2009) | Benoit´s five image restoration strategies (“reducing offensiveness of the event,” “denial,” “evasion of responsibility,” “corrective action,” and “mortification”) were tested regarding restoration of the organizational image after a crisis | „Reducing offensiveness of the event“ was better than the other strategies in a crisis situation where customers were faced with product issues. |

| De Blasio and Veale (2009) | Testing crisis response strategies from defensive to accommodative as continuum | In contrast to highly defensive strategies, accommodating responses had higher impacts on trust levels and image, suggesting less damage on organizational reputation. Neutral strategies, apology and excuse had no significant effect. |

| Kim et al. (2009) | Meta-analysis of several strategies | Denial and bolstering are used extensively, the former is the least effective regarding the outcome. Apology was most effective, followed by mortification, corrective action, and bolstering. |

| Claeys and Cauberghe (2012) | Testing the impact of timing of crisis disclosure on the effect of the response strategies | Stealing thunder vs. not stealing thunder are contrasted. In the latter case, reputation restoring strategies like apologies should be used in addition to providing information. |

| van der Meer and Verhoeven (2014) | Investigating the impact of communicating emotions in organizational responses to crisis situations |

Communicating negative emotions resulting from a crisis (like shame and regret) positively impacts evaluations of organizational reputation. Crisis response strategies aiming at rebuilding (compensation, apology) are better than diminishing (justification, excuse) strategies. |

| Claeys et al. (2016) | Investigating the impact of self-disclosure of incriminating information before this is done by media | Organizational self-diclosure of negative information before the media does so leads to less attention of the public to the latter. That way, the impact is reduced, independent of active or passive organizational involvement in the crisis. Thus, information should be given. |

| Kiambi and Shafer (2016) | Three crisis response strategies (apology, sympathy, compensation) were tested for an organization with high crisis responsibility | Results suggest that stakeholders prefer an apology instead of compensations. Better reputational before a crisis leads to better outcomes of postcrisis evaluations. Highlighting past achievements is suggested for these organizations. |

| Ma and Zhan (2016) | Meta-analysis regarding the impact of attributed crisis responsibility on reputation and which response strategies are protective | Attributed responsibility has a strongly negative impact on organizational reputation. Responses matched to the attributed responsibility are more protective than mismatched responses, no response, and information (aimed at public protection) only. However, the degree of protection is not as strong as the association between responsibility and reputation, suggesting that more than clarifications of responsibility is required. |

| Ferguson et al. (2018) | The perception of 15 image repair strategies was tested based on a sample of close to 800 public relations professionals | Compensation, corrective action, and mortification were ranked highest independent of organizational responsibility or culpability, and across different types of crises. This suggests not only a general set of recommendable strategies, but also implies a hierarchy that remains to be tested. |

| Gribas et al. (2018) | Providing a guide for practitioners on when to use which strategy; differentiating between types of crises | Compensation, corrective action, and mortification are applicable and effective general strategies to use, the remaining ones depend on the causes of the crisis and its context. Denial, blame shifting, attacking the accuser, differentiation, bolstering, and provocation are not recommended on principle. For managerial failure crises, accident, minimization, defeasibility, and transcendence should be avoided. In natural disaster crisis types, transcendence, accident, minimization, and defeasibility can be added to the recommended strategies. For systemic crises, defeasibility is not recommended, while transcendence, accident, and minimization are suggested |

| Schoofs et al. (2019) | Extending the focus on organizational crisis responsibility via investigating the role of stakeholder empathy | Empathy of stakeholders with the organization, especially in victim crises, is beneficial for reputation and leads to less reputational damage. Empathy can be the result of an apology strategy |

| Ma (2020) | Investigating the impact of crisis response strategies dependent on consumer-brand identification | Consumer-brand identification improves the effectiveness of strategies, especially when shared defining attributes remain untouched by the crisis. Moreover, compensation is more effective than apology in reducing negative customer reactions |

According to Jaques (2009), organizational crisis management began to be studied in the 1980s and can be understood as incident response and/or element of managerial processes, depending on the way crisis is defined. This also leads to differences in defining crisis communication (Jaques 2009), which we define as communicative reaction to a crisis, more specifically the “public statements made after crisis” (Coombs 1995, p. 447). For this paper, we only assess situations after a crisis already happened and characterize crisis as “a sudden and unexpected event that threatens to disrupt an organization’s operations and poses both a financial and a reputational threat” (Coombs 2007, p. 164).

In and after a crisis, the public’s perception of an organization is affected by four variables and their interrelatedness: (1) the type of the crisis, (2) the quality of the evidence, (3) the damage done, and (4) past performance. Depending on the combination of these aspects, the stakeholders’ evaluations of the crisis differ (Coombs 1995). Moreover, the relationship with the organization as, e.g., shareholder, employee, client, etc. must be considered. Therefore, adapting organizational reactions is suggested (Bundy and Pfarrer 2015; Coombs 1995), leading to crisis communication or crisis response strategies. Examining the latter in detail is the focus of the paper and done for two organizations with a moderately positive reputation, with similar damages in both types of crises investigated, and reports about it that have the same credibility. As the quality of the evidence (2), the damage done (3) and past performance (4) are kept identical, we focus on (1) in this article.

Theoretical Background

Crisis Evaluation

The bases for the evaluation of a crisis are described in various theoretical approaches. Applying a symbolic-relational perspective on crisis communication, those that provide the most important theoretical foundations to base adequate organizational reactions on are Image Repair Theory, Attribution Theory, Framing Theory, the Situational Theory of Publics, and Situational Crisis Communication Theory (Schwarz 2019). Image Repair (or: Restoration) Theory assumes that something the organization is responsible for occurred that may harm or has already marred the organization’s image and lists five possible actions (denial, evasion, reduction of the offense, corrective action, mortification) (Benoit 1997), without going into detail regarding applicability aspects (Anderson-Meli and Koshy 2020). Attribution Theory is the “study of perceived causation” (Kelley and Michela 1980, p. 458) of behavior and/or events, as the beliefs held about causation influence the reactions – in our case a crisis. Framing Theory is concerned with the presentation (framing) of messages and their effect on the public (Chong and Druckman 2007). The Situational Theory of Publics focuses on the degree of information seeking behavior in case of events (here: crises), which can be linked to emotions aroused that lead to the formation of a public (Aldoory et al. 2010). Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) is rooted in Attribution Theory and focuses on maximizing “the reputational protection afforded by postcrisis communication” (Coombs 2007, p. 163) by basing recommendations on empirical evidence on the factors influencing stakeholder perceptions. Our study, therefore, draws mainly on SCCT as theoretical foundation.

Types of Crises

Certain types of organizational crises are best reacted to with defined communication contents and subsequent actions (Holladay 2010), which have also been demonstrated for brands (Dutta and Pullig 2011). Thus, identifying the crisis type or frame (Holladay 2010) is of utmost importance before deciding on the communication strategy (combination).

There are many classifications of crisis, for example, regarding origin: internal/external, intent: intentional/unintentional, results: severe/non-severe, victims: specific/unspecific, etc. (Coombs 1995). We differentiate between the origin of the crisis: external and internal, and also cover the intentional/unintentional dimension. Both have a high impact on perceived organizational responsibility for crisis. The latter is minimal in case the organization itself is a victim, low should the crisis have been an accident caused by forces that were not easily foreseeable, and high in case the crisis is perceived as having been preventable and the organization’s fault (Coombs 2006, 2017; Holladay 2010). Based on these reflections, Coombs (2012) created three clusters of crises dependent on organizational responsibility starting with (a) the organization being a victim, for example, of a natural disaster, continuing with (b) accidents, for example, due to technical errors, and ending up with (c) preventable crises that occurred, for example, due to human error.

Severity of the crisis, relationship history (Coombs 2006), prior reputation, and crisis history (Eaddy 2021) have an influence on stakeholders’ perception of organizational responsibility (Coombs 2006; Holladay 2010). The higher the damage resultant from a crisis, the higher stakeholders tend to rate organizational responsibility (Coombs 2006; Ye and Ki 2018). SCCT states initial crisis responsibility, crisis history, and prior relational reputation as influencing elements for reputational threat (Coombs 2007). If not properly managed, a fundamentally negative outcome of organizational crises can be loss of reputational capital (Claeys and Cauberghe 2015; Coombs 2007; Dutta and Pullig 2011).

Organizational Reputation

For Herbig and Milewicz (1993, p. 18), reputation is the “estimation of the consistency over time of an attribute of an entity.” As organizations are connected to many attributes like products and brands, the quality of these, their strategy, etc., they can have several reputations (or dimensions of reputation [Abratt and Kleyn 2012; Walker 2010]), together with an overall one (Herbig and Milewicz 1993). In research, the latter as well as the brand reputation are the focus. Additionally, antecedents of organizational reputation (like company size and age) plus consequences (e.g., customer loyalty) have been distinguished (Ali et al. 2015). However, there is no definition of organizational reputation all agree on, as a brief overview by Tkalak Verčič et al. (2016) shows, and no shared theoretical foundation (Bromley 2002).

Following Barnett et al. (2006), organizational reputation equals “observers’ collective judgement of a corporation based on assessments of the financial, social, and environmental impacts attributed to the corporation over time” (p. 34). Models have also tried to combine the basic elements influencing corporate reputation as antecedents, listing financial, social, and communication aspects together with firm characteristics like size and age (Ali et al. 2015).

The basis of stakeholder evaluations is developed through their interactions with the organization (Herbig and Milewicz 1993) and its elements (attributes), but also employees and organizational communication material (Abratt and Kleyn 2012). The standing of an organization is communicated to the stakeholders via signals (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). As interactions occurs over time (Abratt and Kleyn 2012), reputation is connected to past-based, future-extrapolated expectations of stakeholders of what the organization stands for in their perception. Corporate reputation is connected to (personal) experiences with and perceptions of the organization, but also a collective term (Wepener and Boshoff 2015). The amount of information shared by other (ideally influential) stakeholders influences the degree an organization is known (Rindova et al. 2005). Therefore, stakeholder management should cover all interest groups.

In this context, it is important to note that reputation is stakeholder dependent (Walker 2010). Based on which attribute of the organization is relevant for different stakeholders, the ecosystem they evaluate differs (Maden et al. 2012), which may lead to divergent beliefs and, thus, action bases regarding organizational reputation. However, the result of their evaluation can be similar as the criteria are evaluated differently by the stakeholders (Tkalac Verčič and Verčič 2007), which highlights the importance of managing all reputational elements.

The Benefits of a Good Corporate Reputation

Research interest in organizational reputation is high (Abratt and Kleyn 2012). As intangible asset (Vidaver-Cohen 2007) composed of: prominence and perceived product/service quality (Rindova et al. 2005) or: emotional appeal, corporate performance, social engagement, being perceived as good employer, and service points (Wepener and Boshoff 2015), it positively influences organizational performance e.g., via client loyalty and willingness to pay price premiums, which are linked to satisfaction and lower perceived transaction costs based on trust in stable product and service quality, lower buyer risk, etc. (Rindova et al. 2005; Vidaver-Cohen 2007). The impact on purchasing intentions is highly relevant (Yakut and Bayraktaroglu 2021). This creates a self-reinforcing cycle and points to the necessity of reputation management, as expectations must be met in a permanent fashion (Herbig and Milewicz 1993). In case this does not happen, or the organization violates the expectations created, a negative impact on reputation is likely (Coombs 2007). Restoring a harmed or lost reputation can be very difficult (Abratt and Kleyn 2012) and costly regarding time and resources (Herbig and Milewicz 1993).

Positive reputations are intangible assets (Vidaver-Cohen 2007) and vital for the success of the organization (Kay 1995; Wepener and Boshoff 2015). Though there is no final definition available for reputation that all scholars agree on (see for example Tkalac Verčič et al. 2016), most assume that stakeholders do have a perception of the organization that (a) might differ between interest groups (Tkalac Verčič et al. 2016) and (b) forms the basis for deciding on own actions regarding the organization (Maden et al. 2012).

Organizational Reputation and Organizational Crisis

A crisis has immediate and long-term effects on organizations’ performance and reputation (Tkalac Verčič et al. 2019). As mentioned above, organizational reputation is influenced by direct and indirect experiences with the organization (and its elements and attributes) plus informational signals received about the organization (Fombrun and Shanley 1990). Organizational reputation is a resource (Abratt and Kleyn 2012) that can and should be actively managed as a good reputation is linked to positive internal and external outcomes as for example employer attractiveness (Bankins and Waterhouse 2019), but there are no guarantees (Page and Fearn 2005). Organizational reputation affects current and future crisis perception. The more unlike than past situations the current emergency (Coombs 2004), and the better the pre-crisis reputation, the more the organization can build upon (Claeys and Cauberghe 2015). Evidence suggests positive predispositions towards organizations are less prone to major changes after receiving crisis related news (Claeys and Cauberghe 2015; Coombs and Holladay 2014) than for example ambivalent predispositions (Mariconda and Lurati 2015). Taken together, literature highlights (a) to generally invest in corporate reputation, to (b) use it wisely in crisis situations and to (c) adequately respond to the aspects of reputation that are endangered by the crisis.

Crisis Communication Strategies

Crisis communication or crisis response strategies are “what management says and does after a crisis” (Coombs 2007, p. 170). In an organizational context, it encompasses “the collection, processing, and dissemination of information required to address a crisis situation” (Coombs 2010, p. 20) since the response should be adequate to stakeholder needs (Brummette and Sisco 2015). This means it must be modified depending on the type of the situation, the degree of organizational responsibility and the impact on the organizational reputation (Coombs 2006). This adaptation aims at creating the best possible outcome for the organization (for an overview see, e.g., Fediuk et al. 2010). This can be simplified into (a) not changing or (b) returning to or (c) developing a (more) positive mindset.

As Cheng (2018) notes, scholars developed crisis management suggestions as not many organizations never encounter a crisis. A crisis may change stakeholder perception about an organization, its situation and future, potentially requiring mental adjustments. This can depend on the reputational dimension affected, which should be considered in the organizations’ response (Sohn and Lariscy 2014).

Crisis communication can be described as an element of sense making (Pearson and Clair 1998; Weick 1995; Weick et al. 2005) since crisis perception is also socially constructed (Pearson and Clair 1998; Schwarz 2019). Like in change management1 (Böhnisch 1979; Christensen 2014), stakeholder reaction depends on the amount of clear, transparent information that allows personal evaluation and subsequent behavioral response (Aldoory et al. 2010; Auger 2014; Böhnisch 1979), which very much depends on the emotions elicited (Brummette and Sisco 2015; McDonald et al. 2010) as reactions to aspects described above (see Sect. “Types of Crises”) (Breitsohl and Garrod 2016 [for negative emotions]; Coombs 2007).

Systematizing research up to 1995 (Coombs 1995), the strategies for crisis communication can be categorized as

Nonexistence Strategies aimed at declaring there was no crisis using denial, clarification, attack, and/or intimidation,

Distance Strategies employing excuses or justifications to weaken perceived links between the crisis and the organization,

Integration Strategies focusing on improving corporate image by bolstering, transcending the perspective and praising others,

Mortification Strategies showing remorse to win back approval by remediation, repentance and/or rectification, and

Suffering Strategies depicting the organization as victim of external forces.

In Situational Crisis Communication Theory, the suggested strategies depend on the level of responsibility taken on by the organization (Coombs 2006, 2007) and can be clustered in:

Denial strategies (deny, attack accuse, use a scapegoat) to be used in case the organization is seen or can be seen as victim of the crisis,

Diminishing strategies (excuse, justify) in case the crisis was an accident, and

Deal strategies (express concern, regret, compassion, ingratiation, apology) should the crisis have been preventable, or actions leading to it even intentional.

The strategies have been partly renamed and refined by splitting up deal strategies into responses targeted at rebuilding (by compensating, giving an apology) and bolstering reputation (by reminding of past good works, ingratiation of stakeholders, and depicting the organization as victim) (Coombs 2017), building on former ideas (Coombs 2006). A further way to group the strategies is to place their elements on a continuum ranging from defensive to accommodative, which should be employed depending on crisis responsibility (Coombs 1998).

Regarding use of communication strategies, there are some general suggestions: Most basically, the crisis communication strategy should match the situation and be adapted to the organization’s responsibility level (Coombs 2006, 2007). Moreover, the degree and aspects of the potential or actual reputational damage must be considered, preferably per stakeholder group (Rhee and Valdez 2009). In addition, crisis information should be given by the organization itself, ideally before externally discovered (Claeys et al. 2016; Coombs 2015). Nevertheless, only providing information has the least effect on re-establishing organizational reputation after a crisis (Coombs and Holladay 2008) but can be employed in case organizational responsibility is inexistent or very low and the prior relationship with the stakeholders is at least neutral (Coombs 2007).

Denial strategies may be effective in low-responsibility situations (but also with high reputational threat) (Claeys and Cauberghe 2012). Defensiveness might rather harm reputation (Ye and Ki 2018) in case there is an unfavorable public pre-crisis opinion about the organization and/or a negative crisis history, which call for accommodative strategies (Coombs and Holladay 2001). Therefore, diminishing strategies should only be employed in case the perceived crisis responsibility is very low, and denial only in situations of misinformation. Adding bolstering is possible in any case (Coombs 2017).

Deal strategies have been intensively discussed in literature. Expressing shame and regret as emotional signals can have a positive effect on reputation via reducing negative stakeholder emotions and creating higher acceptance for communication issued by the organization (van der Meer and Verhoeven 2014). Researchers report that some strategies may be comparable, so e.g., apology, excuse, and a “no comment” strategy can yield the same results (De Blasio and Veale 2009). Even paradoxical effects have been described in the context of denial and apology/transparent communication. Counterintuitively, denial can be more effective than apology even in case of strong evidence of the organization’s guilt, making honesty and transparency potentially more harmful at least in the short term (Fuoli et al. 2017). Also, the degree of apology, which can range from being perceived as insincere and pressured to fully transparent and aiming at compensation, must be considered (Lwin et al. 2017) just as intercultural aspects for international organizations (Li 2017). All of this is relevant for practice as giving an apology might have unintended legal effects (Coombs and Holladay 2008). However, an apology should be added to the ethical base response (required when there are victims) in case the organization’s responsibility is perceived as high (Coombs 2017). Ethical reactions in a crisis are also necessary in case a threat is posed to stakeholders (Coombs 2007).

Nevertheless, apology should not be the default due to the legal aspects mentioned (Coombs and Holladay 2008) and since response strategies “seem to produce different effects in different crisis situations” (Tkalac Verčič et al. 2019, p. 35). Fully assuming responsibility is not always necessary as “expressing remorse, taking corrective action, and offering compensation” (Bentley 2018, p. 227) might be sufficient, especially when the organization is not completely accountable. Moreover, the reaction depends on the degree the crisis affects, for example, core parts of the organizational image (Kim et al. 2017). McDonald and colleagues suggest controllability of the crisis as best predictor for stakeholder reactions and express the idea of a hierarchy of strategies (McDonald et al. 2010). Thus, recommendations to the effectiveness of specific strategies remain equivocal, especially regarding information, sympathy, apology, and compensations. Considering timing together with content is a solution suggested (Claeys and Cauberghe 2012). However, not all statements issued by the company are also presented fully in mass media (Bowen and Zheng 2015).

As indicated above, the impact and effectiveness of the strategies employed by companies have resulted in mixed findings. A qualitative overview is provided in Table 1.

To expand the theoretical basis of the assumption of a hierarchy of strategies (McDonald et al 2010, Ferguson et al. 2018) and the implications of the research described, our study tests combinations of crisis response strategies in form of a stage model. As Coombs and Holladay (2008) have shown, providing information only has the least effect to improve organizational reputation after a crisis, and is advisable only in case organizational responsibility is negligible and the preceding stakeholder relationship at least impartial (Coombs 2007). Therefore, we use information as stage one. Based on legal recommendations (Coombs and Holladay 2008) and especially for cases when the organization might not be fully accountable (Bentley 2018), an action not implying responsibility (i.e., an apology) is advised for. Therefore, we use the expression of regret as stage 2, preceding apologies as stage 3. Apologies are advised for when there are victims and/or the responsibility of the organization is seen as high (Coombs 2017). Adding compensations is a recommendation in those cases (Bentley 2018), making it stage 4. Starting here, a higher level of commitment is required from the organization. This is mainly monetary for stage 4 and proceeds to include efforts to investigate and implement remedies so that control (stage 5) is gained over the situation. Only after having succeeded, this can be communicated. Stage 6 requires that additional investments in aspects of, e.g., corporate social responsibility, that have already been made before the crisis, indicating a long-standing financial commitment.

Hypotheses

So far, literature suggests that (a) there is no single best response strategy and (b) the choice is context dependent. However, for organizations in crisis this is no real help as they must react quickly, ideally without delays due to trial and error. Certainly, starting with rather basic strategies and then expanding the crisis response set is a possibility, but knowing beforehand how to design the crisis response portfolio would not only save time but also aid in protecting organizational reputation. Therefore, we formulate a stage model and put the hypotheses into specific situational contexts.

Based on the studies on organizational crisis communication, all starts with (1) information. Expressing (2) regret and giving an (3) apology as well as announcing (4) compensations and ensuring to have (5) control over the situation can be added, just as referring and highlighting (6) good deeds in the past. Forming a stage model, this paper aims at testing the impact of the cumulation of these strategies on organizational reputation at three points in time: before, directly after a crisis, and after the organization’s response using specific strategies for externally induced as well as self-inflicted crises. Employing more strategies is assumed to cover the needs of more stakeholder groups. Based on the literature, we thus assume a higher impact of combined strategies and differences regarding the type of crisis as well as time of measurement. Thus, we define the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a

There is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating between the three measurement time points for externally induced crises.

Hypothesis 1b

There is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating between the three measurement time points for self-inflicted crises.

Hypothesis 2a

There is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating concerning the number of strategies used for crisis communication in externally induced crises.

Hypothesis 2b

There is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating concerning the number of strategies used for crisis communication in self-inflicted crises.

Hypothesis 3

There is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating concerning type of crisis (externally induced vs. self-inflicted).

Methods

For testing the hypotheses, an experimental online setting using a questionnaire was chosen. Identical questionnaires were developed for two fictional crisis scenarios (externally induced and self-inflicted) and two hypothetical organizations. The externally induced crisis was either a natural disaster or a global economic downturn, so organizational perceived responsibility is minimal, while the self-inflicted one (management misconduct in both cases) would have been preventable, so responsibility is high (Coombs 2017).

Participants each replied to an online questionnaire comprising of two parts, each referring to one of the two organizations, thus covering both organizations in each questionnaire. When the crisis was externally induced for the first organization, the crisis was self-inflicted for the second organization and vice versa. Both parts were subdivided in three sections: In the first section, the organization was described and had to be rated. In the second, there was a press release about the organization and a crisis. After reading this, the organization had to be rated again. In the third section, a press release of the organization reacting to the press statement was presented. After reading this, the organization had to be rated again. The scales for rating the organization remained the same throughout the questionnaire. In all situational contexts studied, the crisis was unintentional, though potentially foreseeable in the internal cases. To maximally reduce the possibility of participants guessing the hypotheses, a between-participants experimental design and vignettes were used, and not, e.g., a sequential design. This basic structure was randomly varied regarding which organization was presented in which part of the questionnaire, and which organization faced which type of crisis. Each questionnaire, thus, covered both organizations and both types of crises (externally induced and self-inflicted). Moreover, the reactions of the organizations were designed as vignettes, differing in the number of crisis communication strategies employed. In each questionnaire, this was set to be identical: If in part one, the organization used two strategies for responding to the press release regarding crisis type A, then the same two strategies would be used by the other organization in part two for reacting to the press release regarding crisis type B (see Appendix A). The ecological validity of the cues used in the experiment was achieved by (a) clearly differentiating the situations and strategies, (b) ensuring that all information necessary to rate the situation were available, and (c) sufficient similarity of the vignettes each respondent had to reply to (as the types of crisis differed, but the response strategies used were identical) (Kihlstrom 2021). There were no stakeholder roles assigned to the respondents, e.g., shareholder, to ensure personal responses, and there was no variation regarding communication channel the company used.

In Table 2, the six strategies this experiment investigated are listed. They are referred to as number of strategies and strategy number interchangeably in the text.

Table 2.

Strategies used for crisis communication

| No. of strategies (= Strategy No.) | Including |

|---|---|

| 1 | Information (I) |

| 2 | I + expressing regret (ER) |

| 3 | I + ER + apology (A) |

| 4 | I + ER + A + compensations (C) |

| 5 | I + ER + A + C + expressing control (EC) |

| 6 | I + ER + A + C + EC + highlighting good deeds done in the past |

Participants accessed the questionnaire online and anonymously, randomly being assigned to the sequence of the organizations and crisis types as well as response vignettes. Regarding demographic data, sex and age were asked for.

Participants

A sample of 239 participants (179 female), consisting of various occupational groups, ranging from students to retirees, was used. The average age was 31.25 years (SD = 14.28). We did not ask participants to take on or chose a role (client, shareholder, employee, etc.) as the aim was not to differentiate between stakeholder groups, thus making the sample represent the lay public.

Plots

Below, we describe the plots used in the questionnaires. All elements were completely fictional and positive to neutral regarding social approval (Bundy and Pfarrer 2015). We opted to describe nonexistent companies to ensure comparability and reduce bias based on prior knowledge. Moreover, we did not examine different organizational types (Schwarz 2019), an element that can be added to the general evaluation criteria put forward by (Coombs 1995), but only studied companies.

CloudsWool

One of the fictional companies, named CloudsWool (translation by the authors), is a producer of high-quality clothes, 100% out of finest natural fiber, strictly controlled and sourced from India, Peru, and Australia. Production takes place in India, where the company employs experienced workers and ensures good working conditions due to the non-toxic nature of the products. Having been started in 1985, it sells its products in the German speaking parts of Europe.

As plot for the externally induced crisis CloudsWool had to cope with a flood after a dam broke in the region of India where it had a production facility. The water had deluged the facility which led to the result that 1012 people were killed, leaving some others not capable of working again. In the self-inflicted crisis, the facility had been recently bought, not checked enough, and collapsed due to construction defects that had been discovered lately, but not immediately fixed. Also in this plot, 1012 people were killed, and several others would not be capable of working again.

LivingEvolving

The other fictional organization, LivingEvolving (translation by the authors), was founded in 1953 and offers flats, houses, and luxury realty for rent in good locations in Austria and Germany. All properties are regularly renovated and optimized, ensuring the promise of the company: to ensure a feel-good character and give room for evolving. In the plot for the externally induced crisis, LivingEvolving is hit by a current economic crisis, forcing it to sell property to meet loan claims, making thousands worry about their rental contract. Moreover, the shareholders suffer big losses. In the self-inflicted crisis, LivingEvolving had committed tax fraud, forcing massive repayments that make a very quick selling of property necessary. Again, thousands worry about their rental contracts and shareholders suffer big losses.

Measures

As mentioned above, respondents had to rate the companies at three points in time, resulting in a total of 6 times per questionnaire as two different organizations and crisis types were covered in each. We used a scale with eight questions based on the Reputation Quotient SM (Fombrun et al. 2013). All six dimensions (Emotional Appeal, Products and Services, Vision and Leadership, Workplace Environment, Social and Environmental Responsibility, Financial Performance) were covered, but the scale needed to be shortened from 20 to 8 items to fit to the time requirements and the experimental study design, plus translated into German. The dimensions include items that partly require knowledge about the company that we did not provide (e.g., having excellent leadership, likely having good employees, or supporting good causes) or that is nonexistent (e.g., the company tendentially outperforming competitors) as we used fictional examples. Thus, these items were excluded. We used

All 3 items for Emotional Appeal, e.g., “I trust this company,”

Company X “[o]ffers high quality products and services” for Products and Services,

Company X “[h]as a clear vision for its [literally: the] future” for Vision and Leadership,

“Looks like a good company to work for” [literally: I assess company X to be a good employer] for Workplace Environment,

Company X “[i]s an environmentally responsible company” for Social and Environmental Responsibility.

Instead of the items on having a record of profitability, being perceived as a low-risk investment, outperforming competitors and likely having growth prospects, we created “I would invest money in this company” for Financial Performance.

Respondents had to rate the items on 10-point scales ranging from completely disagree to completely agree.

Regarding demographics, age, and sex were asked for.

Cronbach’s Alpha for the scale was between 0.93 and 0.96 for the items depending on the measurement time point and kind of crisis as well as respective company.

Results

First, the questionnaires were grouped according to number of crisis communication strategies used, resulting in six groups. For these, age and sex of the respondents was checked for comparability.

After this, single-factor ANOVAs with multiple group comparison were calculated to check for differences regarding the type of crisis, number of communication strategies plus point in time. This was done separately for externally induced and self-inflicted crisis, covering hypotheses 1 and 2. T tests were used to check which type of crisis most harmed the rating and to answer hypothesis 3.

Externally Induced Crises

In general, organizational reputation is worse after the crisis (second measurement) than before (first measurement), improves at the third measurement (after the organization’s press release), but does not reach initial values (see Fig. 1). The differences between the measurement time points is significant with Greenhouse–Geisser F(1.79, 424.95) = 91.63; p < 0.001 (including Bonferroni adjustment) and Wilks’ Lambda at 0.63, F(2, 237) = 70.32, p < 0.001, multivariate η2 = 0.37.

Fig. 1.

Ratings before the crisis (measure 1), after the crisis (measure 2), and after crisis communication (measure 3) for externally induced crises

Hypothesis 1a (There is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating between the three measurement time points for externally induced crises) is, thus, supported.

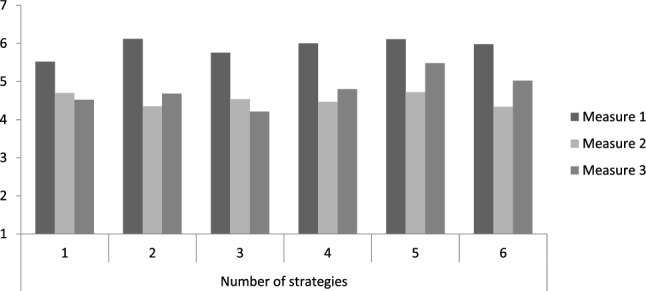

In a next step, the effects of the number of crisis communication strategies used on organizational reputation were tested (see Fig. 2). A unidimensional ANOVA with measurement repetition comparing the outcomes per point in time per number of strategies had a p value of 0.040 for strategy 1 and a value of p < 0.001 for using 2–6 strategies. Using Wilks Lambda, the results for 2–6 strategies stay at p values < 0.001 while p for strategy 1 is not significant (p = 0.085). Pairwise comparisons of the three points in time (with Bonferroni-correction) yielded no significant differences between the measurement points for strategy 1 (ps > 0.082; n = 38). The p values for the others are shown in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Organizational reputation for measurement points and number of crisis communication strategies for externally induced crises

Table 3.

p values for differences between points in time for different numbers of strategies for externally induced crises

| Number of strategies |

p values Time 1–2 |

p values Time 2–3 |

p values Time 1–3 |

n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | < .001 | .504 | < .001 | 40 |

| 3 | < .001 | .237 | < .001 | 40 |

| 4 | < .001 | .153 | < .001 | 40 |

| 5 | < .001 | .004 | .047 | 41 |

| 6 | < .001 | .014 | .001 | 40 |

Only using five or six crisis communication strategies led to significant improvements in ratings between the second measurement (after the crisis) and the third measurement (after the organization’s press release). However, for all six crisis communication strategies organizational reputation was rated significantly lower after the press release compared to the situation before the crisis.

Results of the Spearman correlation indicated that there was a significant positive association between the number of strategies and improvement of organizational reputation (time 2–3), (rs(237) = 0.262, p < 0.001).

Hypothesis 2a (there is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating concerning the number of strategies used for crisis communication in externally induced crises) is, thus, partly supported.

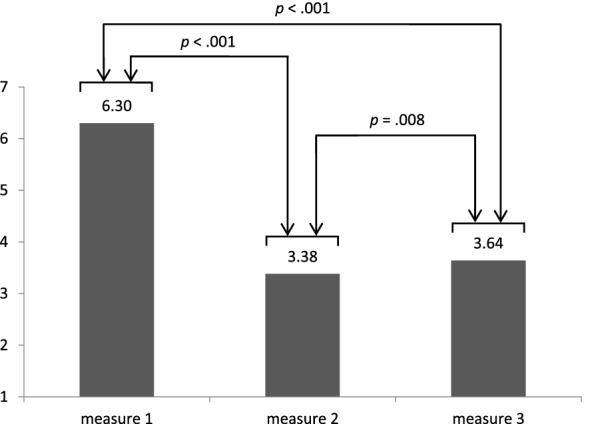

Self-inflicted Crises

Organizational reputation is worse after the crisis (second measurement) than before (first measurement) but remains at lower levels than at baseline after the organization’s press release (third measurement) (see Fig. 3). The differences between the measurement time points is significant with Greenhouse–Geisser F(1.70, 403.97) = 406.15; p < 0.001 (including Bonferroni adjustment) and Wilks’ Lambda at 0.29, F(2, 237) = 285.91, p < 0.001, multivariate η2 = 0.71.

Fig. 3.

Ratings before the crisis (measure 1), after the crisis (measure 2), and after crisis communication (measure 3) for self-inflicted crises

Hypothesis 1b (there is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating between the three measurement time points for self-inflicted crises) is, thus, supported.

Subsequently, the effects of the number of crisis communication strategies used on organizational reputation were tested (see Fig. 4). A unidimensional ANOVA with measurement repetition comparing the outcomes per point in time per number of strategies had a p value of < 0.001 for any number of strategies used. Using Wilks’ Lambda, the results remain at p < 0.001 for all numbers of strategies employed. Then, a unidimensional ANOVA with measurement repetition comparing the three points in time per number of strategies was done (with Bonferroni correction). The p-values are shown in Table 4.

Fig. 4.

Organizational reputation for measurement points and number of crisis communication strategies for self-inflicted crises

Table 4.

p values for differences between points in time for different numbers of strategies for self-inflicted crises

| Number of strategies |

p values Time 1–2 |

p values Time 2–3 |

p values Time 1–3 |

n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | < .001 | .585 | < .001 | 38 |

| 2 | < .001 | .688 | < .001 | 40 |

| 3 | < .001 | .564 | < .001 | 40 |

| 4 | < .001 | .080 | < .001 | 40 |

| 5 | < .001 | .009 | < .001 | 41 |

| 6 | < .001 | .007 | < .001 | 40 |

Like the results for externally induced crises, only using five or six crisis communication strategies led to significant improvements in ratings between the second measurement (after the crisis) and the third measurement (after the organization’s press release). However, for all six crisis communication strategies organizational reputation was rated significantly lower after the press release compared to the situation before the crisis.

Results of the Spearman correlation indicated that there was a significant positive association between the number of strategies and improvement of organizational reputation (time 2–3), (rs(237) = 0.298, p < 0.001).

Hypothesis 2b (there is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating concerning the number of strategies used for crisis communication in self-inflicted crises) is, thus, partly supported.

Harmfulness of Crisis Type

To see whether there is a difference in measurement-point differences before the crisis and after the crisis (measures 1–2) between the two crisis types independent of the company, we conducted a paired samples’ t test. The results indicated that the mean decrease for self-inflicted crises (M = 2.92, SD = 1.94) was significantly greater than the mean decrease for externally induced crises (M = 1.40, SD = 1.83), t(238) = 10.63, p < 0.001.

We also calculated differences in measurement-point differences 1–2 between the two crisis types separately for each company, using independent samples’ t tests. In the case of CloudsWool the mean decrease for the self-inflicted crisis (M = 2.79, SD = 2.02) was significantly greater than the mean decrease for the externally induced crisis (M = 1.21, SD = 2.03), t(237) = 6.01, p < 0.001. For LivingEvolving the mean decrease for the self-inflicted crisis (M = 3.03, SD = 1.87) was also significantly greater than the mean decrease for the externally induced crisis (M = 1.61, SD = 1.56), t(237) = 6.35, p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 3 (there is a significant difference regarding organizational reputation rating concerning type of crisis) is, thus, supported.

Discussion and Conclusion

The aim of the study was to tests which combination of crisis communication strategies is required to improve organizational reputation after a (a) self-inflicted and (b) externally induced crisis, which are known to have different impacts on customer perception (Yakut and Bayraktaroglu 2021). Using an experimental online setting with a diverse sample, we asked respondents to rate combinations of up to six strategies at three points in time for two different companies. Each respondent covered both organizations and both types of crises, both employing a similar number of strategies in their crisis response.

There was a significant difference between the three measurement time points regarding organizational reputation for both types of crises. This indicates that the experimental setting successfully manipulated the perception of the organizations and supports hypothesis 1a and 1b – any crisis leads to different evaluations of the organization, and organizational responses have an impact. The results show that the respondents understood and processed the cues available to them (Kihlstrom 2021) and that organizational reputation improves significantly only after combining at least five strategies – irrespective of the type of crisis, so hypothesis 2a and 2b are partly confirmed. The reputational damage done by self-inflicted crises is higher, supporting hypothesis 3. However, though reputation could be improved from the second to the third measurement, it did not rise to or above baseline level in any context.

While some research found no effect of strategies (Ki and Brown 2013), potentially because the crisis felt too close to the sample (Claeys and Cauberghe 2014; Claeys et al. 2016), our results indicate that there is something that can be done, namely combining strategies. Starting with the cumulative effect of using five crisis communication strategies, the outcomes of crisis communication on organizational reputation were improved. As stage five was expressing control and stage six was referring to good deeds in the past, however, this result also shows that reactions to crises are challenging especially in externally induced crisis situations and/or for small and medium-sized enterprises.

The amount of guilt on the side of the organization needs to be considered when choosing the strategy (Dutta and Pullig 2011), so corrective action for example is only helpful in case this is truly necessary (Coombs 2007). In the experiment this paper reports on, the cumulative impact of strategies is tested. As expected, self-inflicted crises lead to higher loss in reputational capital. While paradox effects have been shown for apologies (Fuoli et al. 2017), the results here show that irrespective of the type of crisis, the cumulative effect of at least five strategies is required to improve organizational reputation. This finding is especially relevant for companies finding themselves in externally induced crises. Though not responsible, the degree of action required is very high and should not be overlooked in favor of investing resources to solve the crisis. In addition to their relevance for organizational crisis managers and internal resource allocation, the result may be helpful for shareholders trying to assess whether an organization is doing enough to alleviate the effects of a crisis and, thus, (still) a safe investment. The same may hold true for employees who are contemplating the impact of a potential reputational (and subsequent financial) loss of their current employer regarding their internal and external career prospects.

Finally, the findings underline the protective effect of positive pre-crisis reputation (Claeys and Cauberghe 2015). It has been debated whether this is only a buffer, meaning the reputational losses in crises are comparable for all organizations, but those with better prior reputational basis are left with more after the deduction (Claeys and Cauberghe 2015; Kiambi and Shafer 2016). Still, re-gaining a positive reputation seems to be easier for those who started on one (Claeys and Cauberghe 2015; Coombs and Holladay 2014) as stakeholders’ perception of organizational crisis responsibility is lower (Claeys and Cauberghe 2015).

Limitations

In the present paper, we studied two fictional organizations (both privately owned companies) together with two direct stakeholders for each in a crisis context, not the complete ecosystem. Still, this already results in a more comprehensive picture about systemic effects and can inform companies in various crisis situations, even in traumatizing conditions as is the case in recessions (see LivingEvolving in the economic crisis) or situations like the COVID-19 pandemic. However, in these instances, the strategies that proved most effective in the experiment may be hard to adopt as so much is unforeseeable. Also, we did not check for the influence of different communication media or channels (Coombs 2017).

By testing strategy combinations, we checked for strategy impact and required scope of the response bundle at the same time, but not whether and which strategies not yielding significant results might be excluded. Thus, future research needs to analyze whether expressing control over the situation and highlighting good deeds done in the past suffice or need to be combined with the other possible strategies.

Moreover, the study differs from others by having chosen a diverse adult sample, not a heterogenic one regarding age and/or occupation. In addition, respondents’ perceived closeness to or experiences with the crisis scenario investigated can have an effect (Aldoory et al. 2010; Claeys and Cauberghe 2014). However, there are studies that specifically use crisis scenarios in experimental settings that feel very close to the participants whose reactions then do not differ between the strategies (Ki and Brown 2013). Thus, a diverse sample is more likely to comprise people with and without feelings of closeness to the situation and might more realistically depict the general population.

The ecological validity of an experiment refers to the extent to which it is generalizable to real world settings, which depends on whether the same cues employed in the experiment are present outside of the lab (Kihlstrom 2021). For the study reported here, this would be the case regarding the cues employed because these are representative for and available in real world situations (Highhouse 2009; Kihlstrom 2021). Moreover, the focus was on underlying issues, the effect of crisis response strategies and their combination on (re)improving reputation, not on designing a typical crisis situation (Highhouse 2009). Nevertheless, in a non-experimental situation, ratings of organizations and their behavior in crises are often only done for one, but not two organizations. We addressed this limitation with the between-participants experimental design and vignettes, plus by varying the order of presenting the companies.

Implications and Future Research

The study showed that (1) a high number of crisis communication strategies are necessary to significantly improve organizational reputation after a crisis. (2) Within these strategies, mainly expressing control over the situation and highlighting good deeds in the past added to the credibility and, thus, effectiveness of organizational crisis communication and subsequent promotion of organizational reputation. Whether these two strategies would suffice or need to be combined with the others to reach a significant impact needs to be investigated. What could not be tested is if organizations lose their credibility in case they afterwards do not follow through, i.e., not fulfill their promises. This might be done using case studies based on existing companies and their crisis management. Future research is needed here as the aftermath of an organizational crisis regarding stakeholder management is very often not reported publicly. Even if, however, the interaction with media might be improved (Choi 2012). What has been tested very recently is the impact brand fans can have (Lim and Brown-Devlin 2021). We did not differentiate between stakeholder groups, so future research might assign roles to the respondents (client, shareholder, employee, etc.) and distinguish between communication channels. Here, press statements were used. As several authors highlighted (Holladay and Coombs 2013; Schultz et al. 2011), the communication medium can be more important than the content transported. Nevertheless, it can be expected to have an influence due to perceived sincerity (Yakut and Bayraktaroglu 2021). Thus, future research might relate the effectiveness of the strategies to the medium chosen, though a lot can be drawn from communication theory. However, various informational sources, their credibility and strategy may be fruitful for further research (Ye and Ki 2018).

Paying attention to and using the potential of social media and not only traditional ones is highly suggested for crisis communication (Roshan et al. 2016; Bukar et al. 2020; Xu 2020). However, when opting for a dual use and when choosing social media channels, the target group and its use of and relationship to the channels (extent of use, attitudes towards and expectations of messages provided in the channel) must be considered (Eriksson and Olsson 2016). Using the same message for different channels is not recommended (Park and Avery 2018). When comparing the outcomes of traditional vs. social media use in crisis communication, a meta-analysis found that the latter was connected to customers perceiving a lower crisis responsibility, especially in college student samples and for fictional organizations, while age and gender (percentage of females) were not of influence. Moreover, the meta-analysis found social media was better for accidents than for crises that could have been prevented (Xu 2020). Thus, type of crisis, intended effect, and demographics of the target group should play a role in choosing the adequate communication channel (Park and Avery 2018), including on whether and how to engage in dialog (Zhao et al. 2019; Bukar et al. 2020).

Moreover, testing the impact of opinions of influencers like in brand research (Singh et al. 2020) might lead to interesting results, just as differentiating between stakeholders’ information needs and preferences (Cheng 2018). Shareholders for example will have other demands as clients, while the latter will likely be more interested in the organizations’ crisis behavior than the public. As company spokesperson and respondent gender similarity have an effect in crisis communication reactions (Crijns et al. 2017), influencer gender might be checked for, as well. In addition, more cultural comparisons are required (Luoma-aho et al. 2017; Schwarz 2019; Ulmer and Pyle 2016) as in today’s world messages often must target a global audience (Griffin Padgett et al. 2013; Ulmer and Pyle 2016).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Biographies

Elisabeth Nöhammer

(equals: Noehammer) studied management, socio-economics (both Master) at Johannes Kepler University, Linz, Austria, and health sciences (Doctorate) at UMIT, Hall in Tirol/Austria. In her research and teaching as Assistant Professor, she combines these fields and has a specific interest in human behavior in different settings and contexts. In addition to exploring interdependencies, one of her aims is to provide evidence-based guidelines for improving settings towards sustainability. For this, Elisabeth studies organizations (companies, hospitals, and universities) and their stakeholders on the structural, organizational, group and individual level, applying both quantitative and qualitative research methods.

Robert Schorn

is an Assistant Professor at University UMIT, Hall in Tirol/Austria. He studied business administration (Master and Doctorate) as well as psychology (Master) at the University of Innsbruck. Robert teaches strategic marketing, consumer psychology, organizational psychology and quantitative research methods from undergraduate to advanced levels. His research interests lie in the field of business psychology. He is also interested in non-conscious effects in consumer psychology where he works in the area of potential, risks, and prevention of consumer manipulation in order to provide the basis for company policies, as well as political decision making, to avoid the misuse of influencing techniques.

Nina Becker

earned her Master’s degree at the Institute of Psychology at UMIT. Her main research interests revolve around the domain of organizational psychology. In the last few years her research has focused on organizational crises and the different kinds of crisis communication.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Just as crisis is “a specific, unexpected, non-routine event or series of events that creates high levels of uncertainty and a significant or perceived threat to high priority goals” (Seeger et al. 1998, p. 233. In: Seeger, M. W., Sellnow, T. L., & Ulmer, R. R. [2003]. Communication and organizational crisis. Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 7), organizational change is a potentially harmful, specific non-routine event (or process) that might come unexpected for individuals or groups.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abratt R, Kleyn N. Corporate identity, corporate branding and corporate reputations: Reconciliation and integration. European Journal of Marketing. 2012;46(7/8):1048–1063. doi: 10.1108/03090561211230197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldoory L, Kim J-N, Tindall N. The influence of perceived shared risk in crisis communication: Elaborating the situational theory of publics. Public Relations Review. 2010;36(2):134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali R, Lynch R, Melewar TC, Jin Z. The moderating influences on the relationship of corporate reputation with its antecedents and consequences: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Research. 2015;68(5):1105–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Meli, L., and Koshy, S. 2020. A new public relations crisis communication model (1 ed.).

- Auger GA. Trust me, trust me not: An experimental analysis of the effect of transparency on organizations. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2014;26(4):325–343. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2014.908722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bankins S, Waterhouse J. Organizational identity, image, and reputation: Examining the influence on perceptions of employer attractiveness in public sector organizations. International Journal of Public Administration. 2019;42(3):218–229. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2018.1423572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett ML, Jermier JM, Lafferty BA. Corporate reputation: The definitional landscape. Corporate Reputation Review. 2006;9(1):26–38. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit WL. Image repair discourse and crisis communication. Public Relations Review. 1997;23(2):177–187. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(97)90023-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley JM. What counts as an apology? Exploring stakeholder perceptions in a hypothetical organizational crisis. Management Communication Quarterly. 2018;32:232. doi: 10.1177/0893318917722635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Böhnisch WR. Personale Widerstände bei der Durchsetzung von Innovationen. Stuttgart: Poeschel; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SA, Zheng Y. Auto recall crisis, framing, and ethical response: Toyota's missteps. Public Relations Review. 2015;41(1):40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breitsohl J, Garrod B. Assessing tourists' cognitive, emotional and behavioural reactions to an unethical destination incident. Tourism Management. 2016;54:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2015.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley D. Comparing corporate reputations: League tables, quotients, benchmarks, or case studies? Corporate Reputation Review. 2002;5(1):35–50. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brummette J, Sisco HF. Using Twitter as a means of coping with emotions and uncontrollable crises. Public Relations Review. 2015;41(1):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bukar Umar Ali, Jabar Marzanah A, Sidi Fatimah, Nor Rozi Nor Haizan Binti, Abdullah Salfarina, Othman Mohamed. Crisis informatics in the context of social media crisis communication: Theoretical models, taxonomy, and open issues. IEEE Access. 2020;8:185842–185869. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3030184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bundy J, Pfarrer MD. A burden of responsibility: The role of social approval at the onset of a crisis. Academy of Management Review. 2015;40(3):345–369. doi: 10.5465/amr.2013.0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. How social media is changing crisis communication strategies: Evidence from the updated literature. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2018;26(1):58–68. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. A content analysis of BP's press releases dealing with crisis. Public Relations Review. 2012;38(3):422–429. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chong D, Druckman JN. Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science. 2007;10:103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M. Communication as a strategic tool in change processes. International Journal of Business Communication. 2014;51(4):359–385. doi: 10.1177/2329488414525442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys A-S, Cauberghe V. Crisis response and crisis timing strategies, two sides of the same coin. Public Relations Review. 2012;38(1):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys A-S, Cauberghe V. What makes crisis response strategies work? The impact of crisis involvement and message framing. Journal of Business Research. 2014;67(2):182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys A-S, Cauberghe V. The role of a favorable pre-crisis reputation in protecting organizations during crises. Public Relations Review. 2015;41(1):64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys A-S, Cauberghe V, Pandelaere M. Is old news no news? The impact of self-disclosure by organizations in crisis. Journal of Business Research. 2016;69(10):3963–3970. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT. Choosing the right words: The development of guidelines for the selection of "appropriate" crisis-response strategies. Management Communication Quarterly. 1995;8:476. doi: 10.1177/0893318995008004003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT. An analytic framework for crisis situations: Better responses from a better understanding of the situation. Journal of Public Relations Research. 1998;10(3):177–191. doi: 10.1207/s1532754xjprr1003_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT. Impact of past crises on current crisis communication: Insights from situational crisis communication theory. The Journal of Business Communication. 2004;41(3):265–289. doi: 10.1177/0021943604265607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT. The protective powers of crisis response strategies: Managing reputational assets during a crisis. Journal of Promotion Management. 2006;12(3–4):241–260. doi: 10.1300/J057v12n03_13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review. 2007;10(3):163–176. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W.T. 2010. Parameters for crisis communication. The handbook of crisis communication (pp. 17–53).

- Coombs WT. Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding. 3. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT. The value of communication during a crisis: Insights from strategic communication research. Business Horizons. 2015;58:148. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2014.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W.T. 2017. Revising situational crisis communication theory: The influences of social media on crisis communication theory and practice (1 ed.).

- Coombs WT, Holladay SJ. An Extended examination of the crisis situations: A fusion of the relational management and symbolic approaches. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2001;13(4):321–340. doi: 10.1207/S1532754XJPRR1304_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT, Holladay SJ. Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly. 2002;16(2):165–186. doi: 10.1177/089331802237233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT, Holladay SJ. Comparing apology to equivalent crisis response strategies: Clarifying apology's role and value in crisis communication. Public Relations Review. 2008;34(3):252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs WT, Holladay SJ. How publics react to crisis communication efforts. Journal of Communication Management. 2014;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- Crijns H, Claeys A-S, Cauberghe V, Hudders L. Who says what during crises? A study about the interplay between gender similarity with the spokesperson and crisis response strategy. Journal of Business Research. 2017;79:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dardis Frank, Haigh Michel M. Prescribing versus describing: Testing image restoration strategies in a crisis situation. Corporate Communications: An International Journal. 2009;14(1):101–118. doi: 10.1108/13563280910931108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean Dwane Hal. Consumer reaction to negative publicity: Effects of corporate reputation, response, and responsibility for a crisis event. The Journal of Business Communication. 2004;41(2):192–211. doi: 10.1177/0021943603261748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Blasio A, Veale R. Why say sorry? Influencing consumer perceptions post organizational crises. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ) 2009;17:83. doi: 10.1016/j.ausmj.2009.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Pullig C. Effectiveness of corporate responses to brand crises: The role of crisis type and response strategies. Journal of Business Research. 2011;64(12):1281–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eaddy LL. Unearthing the facets of crisis history in crisis communication: A conceptual framework and introduction of the crisis history salience scale. International Journal of Business Communication. 2021 doi: 10.1177/2329488420988769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson Mats, Olsson Eva-Karin. Facebook and Twitter in crisis communication: A comparative study of crisis communication professionals and citizens. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2016;24(4):198–208. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fediuk, T.A., Pace, K.M., and Botero, I.C. 2010. Crisis response effectiveness: Methodological considerations for advancement in empirical investigation into response impact. The handbook of crisis communication, pp. 221–242.

- Ferguson, D. P., Wallace, J. D., and Chandler, R. C. 2018. Hierarchical consistency of strategies in image repair theory: PR practitioners’ perceptions of effective and preferred crisis communication strategies. Journal of Public Relations Research 30 (5–6): 251–272. 10.1080/1062726X.2018.1545129.

- Fombrun C, Gardberg NA, Sever JM. The reputation quotient SM: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. Journal of Brand Management. 2013;7(4):241–255. doi: 10.1057/bm.2000.10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun C, Shanley M. What's in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal. 1990;33(2):233–258. doi: 10.2307/256324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuoli M, van de Weijer J, Paradis C. Denial outperforms apology in repairing organizational trust despite strong evidence of guilt. Public Relations Review. 2017;43(4):645–660. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gribas J, DiSanza J, Legge N, Hartman KL. Organizational image repair tactics and crisis type: Implications for crisis response strategy effectiveness. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research. 2018;1(2):225–252. doi: 10.30658/jicrcr.1.2.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin Padgett DR, Cheng SS, Parekh V. The quest for transparency and accountability: Communicating responsibly to stakeholders in crises. Asian Social Science. 2013;9:44. doi: 10.5539/ass.v9n9p31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Highhouse Scott. Designing experiments that generalize. Organizational Research Methods. 2009;12(3):554–566. doi: 10.1177/1094428107300396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herbig P, Milewicz J. The relationship of reputation and credibility to brand success. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 1993;10(3):18–24. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000002601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holladay, S.J. 2010. Are they practicing what we are preaching? An investigation of crisis communication strategies in the media coverage of chemical accidents. The handbook of crisis communication, pp. 159–180.

- Holladay SJ, Coombs WT. Successful prevention may not be enough: A case study of how managing a threat triggers a threat. Public Relations Review. 2013;39(5):451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaques T. Issue and crisis management: Quicksand in the definitional landscape. Public Relations Review. 2009;35(3):280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, J. 1995. Foundations of corporate success: how business strategies add value: Oxford Paperbacks.

- Kelley HH, Michela JL. Attribution theory and research. Annual Review of Psychology. 1980;31(1):457–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ki E-J, Brown KA. The effects of crisis response strategies on relationship quality outcomes. The Journal of Business Communication. 2013;50(4):403–420. [Google Scholar]

- Kiambi DM, Shafer A. Corporate crisis communication: Examining the interplay of reputation and crisis response strategies. Mass Communication and Society. 2016;19(2):127–148. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2015.1066013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kihlstrom John F. Ecological validity and “ecological validity”. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2021;16(2):466–471. doi: 10.1177/1745691620966791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Sora, Avery Elizabeth Johnson, Lariscy Ruthann W. Are crisis communicators practicing what we preach?: An evaluation of crisis response strategy analyzed in public relations research from 1991 to 2009. Public Relations Review. 2009;35(4):446–448. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Choi SM, Atkinson L. Congruence effects of corporate associations and crisis issue on crisis communication strategies. Social Behavior and Personality. 2017;45:1098. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. Apology as a crisis response strategy: A genre-based analysis of intercultural corporate apologies. International Journal of Linguistics and Communication. 2017;5(1):73–83. doi: 10.15640/ijlc.v5n1a8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HS, Brown-Devlin N. The value of brand fans during a crisis: Exploring the roles of response strategy, source, and brand identification. International Journal of Business Communication. 2021 doi: 10.1177/2329488421999699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma-aho V, Moreno A, Verhoeven P. Crisis response strategies in Finland and Spain. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2017;25:231. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lwin MO, Pang A, Loh J-Q, Peh MH-Y, Rodriguez SA, Zelani NHB. Is saying ‘sorry’ enough? Examining the effects of apology typologies by organizations on consumer responses. Asian Journal of Communication. 2017;27(1):49–64. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2016.1247462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L. How the interplay of consumer-brand identification and crises influences the effectiveness of corporate response strategies. International Journal of Business Communication. 2020 doi: 10.1177/2329488419898222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Zhan Mengqi. Effects of attributed responsibility and response strategies on organizational reputation: A meta-analysis of situational crisis communication theory research.". Journal of Public Relations Research. 2016;28:102–119. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2016.1166367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maden C, Arıkan E, Telci EE, Kantur D. Linking corporate social responsibility to corporate reputation: A study on understanding behavioral consequences. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2012;58:655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.1043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mariconda S, Lurati F. Ambivalence and reputation stability: An experimental investigation on the effects of new information. Corporate Reputation Review. 2015;18(2):87–98. doi: 10.1057/crr.2015.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald LM, Sparks B, Glendon AI. Stakeholder reactions to company crisis communication and causes. Public Relations Review. 2010;36(3):263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Page G, Fearn H. Corporate reputation: What do consumers really care about? Journal of Advertising Research. 2005;45(3):305. doi: 10.1017/S0021849905050361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park Sejin, Avery Elizabeth Johnson. Effects of media channel, crisis type and demographics on audience intent to follow instructing information during crisis. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2018;26(1):69–78. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, C., and Clair, J. 1998. Reframing crisis management. Academy of management review.

- Rhee M, Valdez ME. Contextual factors surrounding reputation damage with potential implications for reputation repair. Academy of Management Review. 2009;34(1):146–168. doi: 10.5465/amr.2009.35713324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rindova VP, Williamson IO, Petkova AP, Sever JM. Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Academy of Management Journal. 2005;48(6):1033–1049. doi: 10.5465/amj.2005.19573108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roshan Mina, Warren Matthew, Carr Rodney. Understanding the use of social media by organisations for crisis communication. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;63:350–361. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]