Abstract

The one‐electron reduction of the nonheme iron(III)‐hydroperoxo complex, [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ (L5 2=N‐methyl‐N,N’,N’‐tris(2‐pyridylmethyl)ethane‐1,2‐diamine), carried out at −70 °C results in the release of dioxygen and in the formation of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ following a bimolecular process. This reaction can be performed either with cobaltocene as chemical reductant, or electrochemically. These experimental observations are consistent with the disproportionation of the hydroperoxo group in the putative FeII(OOH) intermediate generated upon reduction of the FeIII(OOH) starting complex. One plausible mechanistic scenario is that this disproportionation reaction follows an O−O heterolytic cleavage pathway via a FeIV‐oxo species.

The one‐electron reduction of a nonheme FeIII(OOH) intermediate results in the release of the FeII(OH) complex and O2, following a bimolecular reaction consistent with the disproportionation of the hydroperoxo ligand in a putative FeII(OOH) species. One plausible mechanistic scenario is that this disproportionation reaction follows an O−O heterolytic cleavage pathway via a FeIV‐oxo species.

Introduction

Oxygen is used as direct oxidant by heme and nonheme oxygenases to carry out a variety of biochemical transformations of organic metabolites. Thanks to extensive studies, the mechanism by which cytochromes P450 activate dioxygen to transfer one oxygen atom to their substrate while releasing the other as water has been precisely determined and serves as a paradigm. Along their catalytic cycle, these enzymes first generate a FeIII‐superoxo (FeIII(OO⋅)) intermediate resulting from coordination of O2 to the reduced FeII active site. Electron and proton transfer to this FeIII(OO⋅) species yields a FeIII‐hydroperoxo (FeIII(OOH)) complex which evolves via heterolytic O−O cleavage into Compound I, a formally FeV‐oxo (FeV(O)) as the catalytic active species for the target reaction, frequently being an oxygen atom transfer to the substrate.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] A similar Compound I is generated following the heterolytic activation of hydrogen peroxide by heme catalase but it is directed towards the oxidation of a second equivalent of H2O2, leading to an overall disproportionation of hydrogen peroxide into dioxygen and water. [4] In contrast, the exact mechanism of nonheme Mn Catalases is precluded due to their fast kinetics, but it is admitted that their dinuclear active site cycles between the MnII 2 and MnIII 2 states for H2O2 removal, even though higher oxidation states are accessible. [5] Nonetheless, the implication of higher valent intermediates is supported by studies with synthetic functional models of Mn Catalases.[ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] Therefore, it is not surprising that disproportionation of hydrogen peroxide is a common competitive reaction in H2O2‐dependent hydrocarbon oxidations catalyzed by metal complexes.[ 9 , 10 , 11 ]

It is now well‐documented that the reaction of nonheme iron complexes with hydrogen peroxide generates FeIII(OOH) intermediates.[ 12 , 13 , 14 ] Studies performed with (N4 )FeIII(OOH) complexes have demonstrated that the heterolytic O−O cleavage is favored when the tetradentate N4 ligand leaves two cis labile positions in the coordination sphere of the metal center,[ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ] thus leading to cis‐FeV(O)(OH) species,[ 19 , 20 , 21 ] which are efficient metal‐based oxidants. [22] In contrast, (N5 )FeIII(OOH) intermediates evolve via homolytic O−O cleavage yielding FeIV(O)+OH⋅ species.[ 11 , 23 , 24 , 25 ] Interestingly, several studies report that the reduction of (N4 )FeIII‐hydroperoxo, (N4 )FeIII‐alkylperoxo [26] or (N4 )FeIII‐peroxo binding a non‐redox cation [27] (where N4 is a macrocyclic ligand of the tetramethylcyclam family) generates a (N4 )FeIV(O) species, suggesting an heterolytic cleavage occurs after reduction. Along the same line, indirect evidence for inter‐related FeII(OOH) / FeIV(O)(OH) species have also been reported.[ 28 , 29 , 30 ]

We have analyzed both the one‐electron chemical and electrochemical reduction of the non‐porphyrinic [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ intermediate stabilized at −70 °C (L5 2=N‐methyl‐N,N’,N’‐tris(2‐pyridylmethyl)ethane‐1,2‐diamine, Figure 1), and report in this paper that it leads to the release of O2 and the formation of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ in a bimolecular process. This reaction formally corresponds to the disproportionation of the hydroperoxo group, which suggests that the transient FeII(OOH) species generated upon reduction of the FeIII(OOH) complex evolves via heterolytic O−O cleavage. Alternative mechanistic scenarios following the initial electron transfer are discussed.

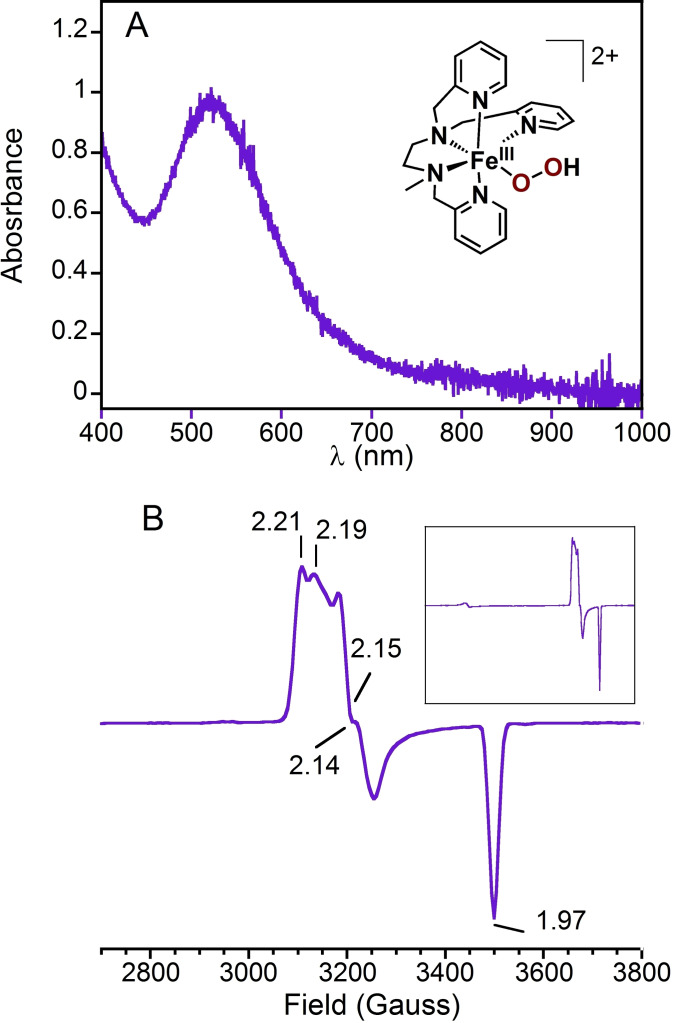

Figure 1.

(A) Electronic absorption spectrum of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)](PF6)2 with its schematical representation (1 mM, PrCN+0.2 M TBAPF6 at −70 °C). (B) X‐band EPR spectrum of the same sample recorded at 90 K. The inset shows the full spectral range (0–5000 Gauss). The complete assignment is given in the Supporting Information, Figure S1. Microwave frequency 9.65 GHz, microwave power 1.0 mW, modulation amplitude 8 G, gain 50 dB, modulation frequency 100 kHz.

Results and Discussion

In order to investigate the redox properties of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+, the complex was prepared and isolated following the method we reported previously (Supporting Information, Experimental Section).[ 23 , 31 ] [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ was formed in MeOH following reaction of [FeIICl(L5 2)](PF6) with an excess (100 equiv.) of H2O2, and precipitated at −80 °C upon addition of cold Et2O. The purple solid, [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)](PF6)2, was isolated by removing the solvent and the excess of H2O2 via a cannula equipped with a glass filter. The obtained solid was carefully washed with a large volume of cold Et2O and redissolved in butyronitrile (PrCN) at −80 °C yielding stock solutions with concentrations ranging between 1 and 4 mM as quantified by both the hydroperoxo‐to‐FeIII charge transfer band centered at 530 nm (1000 M−1 cm−1)[ 12 , 32 ] and double integration of the X band EPR signal of this low spin (S=1/2) complex (Figure 1 and Supporting Information, Figure S1 for assignment). All experiments were performed at low temperature (<−50 °C) to minimize the degradation of the FeIII(OOH) intermediate.

The cyclic voltammogram (CV) of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ exhibits a cathodic peak at E p,c=−0.20 V vs. SCE (Figure 2), a value consistent with the reduction potential measured for the similar [FeIII(OOH)(TPEN)]2+ complex, E p,c=‐0.08 V vs. SCE.[ 33 , 34 , 35 ] A second cathodic peak is observed at −0.94 V vs. SCE, which is assigned to the reduction of O2 into O2⋅− (Supporting Information, Figure S2). Interestingly, comparison between the CVs of independently prepared samples reveals that the intensity of the cathodic peak of O2 is dependent on the intensity of the [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ peak (Supporting Information, Figure S2), thus indicating that the presence of O2 is a consequence of the reduction of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+. On the reverse scan, the anodic peak detected at E p,a=0.62 V vs. SCE is assigned to the oxidation of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+, in agreement with the CV of [FeII(MeCN)(L5 2)]2+ recorded under alkaline conditions (Supporting Information, Figure S3) and reported data.[ 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 ] Note that the [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ oxidation wave is observed only when the sample is first scanned towards negative potentials (Figure 2 and Supporting Information, Figure S2A). Hence, [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ and O2 are formed as a result of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ reduction.

Figure 2.

Cyclic Voltammogram of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)](PF6)2 (1 mM) in PrCN+0.2 M TBAPF6 at −70 °C, 0.1 V s−1. The arrows indicate the initial direction of the scan.

To confirm this hypothesis, this reaction was carried out using cobaltocene (E°′=−0.95 V vs. SCE) [39] as a single electron reductant and followed by UV‐visible spectroscopy (Figure 3A). Immediately after the introduction of cobaltocene (1 equiv. vs. Fe), the 530‐nm band rapidly decreased in intensity and vanished while an absorption at ca. 390 nm progressively developed (Figure 3A). This 390‐nm band is assigned to a t2g(FeII)‐to‐π*(pyridine) charge transfer transition consistent with the formation of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ (Supporting Information, Figure S3A). Aliquots from this reaction mixture were taken and analyzed by X‐band EPR spectroscopy in parallel mode detection. The progressive formation of O2 following the reduction of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ was confirmed by detecting its characteristic signature over the 0–5000 G spectral window (Figure 3B and Supporting Information, Figure S4). [40] UV/vis experiments indicate that the complete reduction of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ requires 1 equivalent of reductant. As seen in Figure 3A, the extinction of the FeIII(OOH) LMCT at 530 nm is achieved before the MLCT of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ at 390 nm stops developing. This observation indicates that the reduction of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ is faster than the formation of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+, and as a result, of O2, and suggests that these species are formed in a secondary step (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) UV‐visible monitoring of the reaction of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)](PF6)2 (−50 °C, 0.15 mM in PrCN/MeCN 1 : 1, blue trace) with 1 equiv. Co(Cp)2 (black to grey to red trace). The inset shows the time traces of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ disappearance at 530 nm (blue) and [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ formation at 390 nm (red). (B) Parallel mode X‐band EPR spectra at 10 K of aliquots taken from the same reaction mixture (with corresponding color lines). Microwave frequency 9.38 GHz, microwave power 2.0 mW, modulation amplitude 8 G, gain 50 dB, modulation frequency 100 kHz, temperature 10 K. Experiments were done in the presence of 2 equivalents of potassium tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate to avoid cobaltocenium precipitation.

O2 production was also confirmed by locating a fluorescent probe in the headspace of a UV‐visible cuvette (Supporting Information, Figure S5). Introduction of cobaltocene in a solution of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ led to a decrease of the fluorescence lifetime of the probe chromophore. This observation indicates that the triplet excited state of the chromophore is quenched by reaction with the triplet state of released dioxygen. Performing the reaction by introducing only 0.5 equiv. reductant vs. the initial amount of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ intermediate followed by another portion of 0.5 equiv. reductant after the initial release of O2 resulted in the production of a second identical amount of O2.

To summarize, the 1 : 1 reaction between [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ and the one electron reductant results in the formation of O2 and [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ (equation 1):

| (1) |

Formally, the generation of O2 and HO− (i. e. [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+) corresponds to the disproportionation of the hydroperoxo ligand upon reduction of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+.

Alternatively, addition of cobaltocene to [FeIII(OO)(L5 2)]+ (obtained by deprotonation of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+, see Supporting Information, Experimental Section)[ 33 , 41 , 42 ] led to the disappearance of the iron‐peroxo complex but did not lead to the evolution of O2 (Supporting Information, Figure S6), [43] in agreement with the fact that protons are needed to achieve the disproportionation.

With [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ being susceptible to exogenous ligand exchange in solution (Supporting Information, Figure S3), its amount is difficult to determine. Hence, in order to validate the stoichiometry of the reaction written in Equation (1) we estimated the quantity of O2 produced by simulating the CV of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ (Supporting Information, Electrochemical Methodology and Figure S16). [44] To obtain this information the overall reaction described in Equation (1) was decomposed into electrochemical and chemical steps (Eq.s 2 and 3). The O2/O2⋅− redox couple, which is expected to contribute to the global current, was considered as well (Eq. 4).

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

A good agreement between the experimental CV and the simulation resulting from equations 2–4 (Supporting Information, Figure S16) supports this series of reactions and confirms the global reaction (Eq. (1)) in which the one electron reduction of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ generates one equivalent of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ and half an equivalent of O2.

Further support for the reaction in Equation (1) was obtained by analyzing the absorbance vs. time trace at 390 nm (Figure 3A, inset). This trace representing the formation of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+, was fitted to second‐order kinetics, as suggested by Equation (1), and to first order kinetics for comparison. As shown in Supporting Information, Figure S7, the agreement with the second order rate law is excellent, whereas first‐order kinetics appear inconsistent.

Monitoring this reaction at lower T (−60 °C) and different initial concentrations of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ confirmed that the formation of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ is a second order reaction (Supporting Information, Figure S8). Additionally, the observation that the complete reduction of the FeIII(OOH) intermediate occurs before the formation of the FeII(OH) complex is achieved (compare blue and red traces in Figure 3A, inset) suggests that after the one‐electron reduction process, the generated [FeII(OOH)(L5 2)]+ engages in a global bimolecular rate determining reaction to produce O2 and [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+. Overall, these observations also imply that the O−O bond of the peroxide must be cleaved heterolytically at one point to ultimately produce the FeII(OH) complex.

Two alternative mechanisms can be evoked to account for the disproportionation of the peroxide. Either a dimerization step of the generated FeII(OOH) occurs first, followed by O−O bond cleavage; or the O−O bond cleavage occurs in the early steps of the mechanism yielding a high‐valent iron‐oxo species which reacts in a bimolecular process in the later stages.

In proposition A (Scheme 1 A and Supporting Information, Figure S9), the FeII(OOH) species would engage in a rate‐determining bimolecular reaction to form a (speculative) diferrous species with μ‐1,2‐peroxo and μ‐1,1‐hydroperoxo bridging ligands which would release a hydroxide and generate a (μ‐1,2‐peroxo)diferric intermediate. This latter intermediate would finally release O2 and two FeII(OH) complexes. Such a mechanistic scenario is reminiscent to that of Mn Catalases with two metal centers cycling between the +II and +III oxidation states.

Scheme 1.

Possible mechanisms accounting for the disproportionation reaction of the peroxo group without (A) or with (B) accumulation of a high‐valent iron‐oxo intermediate.

In this proposition, the uncommon μ‐1,1 binding mode of one peroxo ligand has recently been observed in the Nonheme N‐Oxygenase CmlI. [45] A key intermediate in the catalytic cycle of Δ9 Desaturase has also been proposed to display such a motif. [46]

Alternatively, in proposition B (Scheme 1 B and Supporting Information, Figure S10), the heterolytic cleavage of the putative FeII(OOH) intermediate would result in the formation of FeIV(O) and an OH− which we propose to bind the high valent metal center upon substitution of one of the (L5 2) pyridine groups. The nascent [FeIV(O)(OH)(L5 2)]+ would then engage in a rate‐determining reaction to form a (μ‐1,2‐peroxo)diferric intermediate, which would produce O2 and two equivalents of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]2+ in the final step.

For this latter proposition, which relies on the formation of a FeIV(O)(OH) intermediate upon reduction of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+, consistent examples can be found in the literature. Bang et al. [47] and Bae et al. [48] demonstrated that the reduction of [FeIII(OO)(TMC)]+‐Mn+ (where Mn+ is a hard Lewis acid) led to [FeIV(O)(TMC)]2+ upon heterolytic cleavage of the peroxo group. Heterolytic O−O cleavage of FeII‐H2O2 adducts was shown to be promoted by the presence of a general base which shuttles the proximal proton to the distal oxygen to generate FeIV(O) while releasing H2O.[ 49 , 50 , 51 ] Paine and coworkers also proposed the formation of a reactive FeIV(O)(OH) species from a putative FeII(OOH) intermediate formed by oxygenation of the [(TpPh2)FeII(benzilate)] complex and decarboxylation of benzilate. [28] Another key feature of this mechanism is the formation of the O−O bond between the two FeIV(O)(OH) entities to yield a peroxo‐bridged diiron(III) intermediate. A reversible equilibrium between such type of intermediates has been reported by Kodera et al.[ 52 , 53 ] Furthermore, formation of O−O bonds between two FeIV(O) units in a hexanuclear iron complex supported on a stannoxane core was proposed by Ray and coworkers. [54] These authors suggested that the O−O bond was readily formed via radical coupling yielding a peroxo bridged diiron(III) species. A radical coupling step has also been proposed in the case of O2 production catalyzed by a ruthenium complex. [55]

Using both of these mechanisms, we performed a complete kinetic analysis based on the decay of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ at 530 nm and the formation of [FeII(OH)(L5 2)]+ at 390 nm (Supporting Information, Figures S9 & S10). The results obtained are consistent with both propositions. In each mechanism, only the species which is engaged in the bimolecular rate determining step accumulates to a significant amount i.e. FeII(OOH) in the first case (Supporting Information, Figure S9) and the FeIV(O)(OH) complex in the second case (Supporting Information, Figure S10).

A closer inspection of the UV‐visible monitoring of the reaction in the NIR region reveals the growth and decay of a broad absorption around 900 nm with an apparent extinction coefficient of ca. 250 M−1 cm−1 (Supporting Information, Figure S11). To our knowledge, no FeII(OOH) species has been spectroscopically characterized yet and only one FeIV(O)(OH) complex, namely [FeIV(O)(TMC)(OH)]+, has been reported.[ 56 , 57 ] This complex exhibited two weak absorptions at 830 (100 M−1 cm−1) and 1060 nm (110 M−1 cm−1), which is similar to what we observed. Based on proposition B, implying the transient formation of a FeIV(O)(OH) species, we could extract by a global kinetic fit species spectra corresponding to the initial FeIII(OOH) complex, the final FeII(OH) and the proposed transient FeIV(O)(OH) species, supporting the heme catalase‐based mechanism as the most likely scenario. Note that [FeIV(O)(L5 2)]2+, namely the FeIV(O) species supported by the pentadentate L5 2 ligand, displays an absorption band at 730 nm (300 M−1 cm−1) and a much longer lifetime than the fast decaying species observed at 900 nm. Thus, this latter species cannot be formulated to be the same.

While the stoichiometry of the global disproportionation of the peroxide has been demonstrated, there is still a question regarding the exact mechanism. An important progress would be to determine whether a high valent iron‐oxo species indeed forms upon heterolytic cleavage of the O−O bond, by intercepting it with a substrate. Additionally, confirming (with labelling studies for example) that the O−O bond formation results from coupling between two iron‐oxo species would be significant. However, these studies are made difficult by the instability of the reagent and the stoichiometric nature of the reaction.

Conclusion

The chemical and electrochemical single‐electron reduction of [FeIII(OOH)(L5 2)]2+ at low temperature (−50 °C–−70 °C) yields a putative FeII(OOH) species which disproportionates to give one equivalent of FeII(OH) complex and half an equivalent of O2, indicating that the FeII(OOH) species evolves via heterolytic O−O cleavage. To account for the global reaction, two kinetically valuable alternative mechanisms can be envisioned. One involves dinuclear FeII 2 and FeIII 2 species as key intermediates, in a mechanism which is reminiscent of Mn Catalases. The other one involves the generation of a FeIV(O)(OH) intermediate and the coupling between two equivalents of this latter species to release O2. This latter proposition is supported by the transient formation of a chromophore which we tentatively assign to such high valent iron(IV)‐oxo species. The determination of the exact mechanism requires to identify the precise nature of this intermediate. Studies in that direction are under investigation in our laboratories.

Experimental Section

Experimental procedures for the generation of reaction intermediates and their chemical reduction; description of the analytical techniques used; detailed methodology for the simulation of the CVs.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the LABEX CHARMMMAT (ANR‐11‐LABX‐0039). Dr Zakaria Halime is thanked for his kind help.

A. Bohn, K. Sénéchal-David, J.-N. Rebilly, C. Herrero, W. Leibl, E. Anxolabéhère-Mallart, F. Banse, Chem. Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202201600.

Contributor Information

Dr. Elodie Anxolabéhère‐Mallart, Email: elodie.anxolabehere@u-paris.fr.

Prof. Frédéric Banse, Email: frederic.banse@universite-paris-saclay.fr.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Meunier B., de Visser S. P., Shaik S., Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3947–3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Denisov I. G., Makris T. M., Sligar S. G., Schlichting I., Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2253–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Poulos T. L., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3919–3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nicholls P., Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 525, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Signorella S., Hureau C., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abashkin Y. G., Burt S. K., J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 2708–2711. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abashkin Y. G., Burt S. K., Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 1425–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Merlini M. L., Britovsek G. J. P., Swart M., Belanzoni P., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2944–2958. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zondervan C., Hage R., Feringa Ben L., Chem. Commun. 1997, 419–420. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dong J. J., Unjaroen D., Mecozzi F., Harvey E. C., Saisaha P., Pijper D., de Boer J. W., Alsters P., Feringa B. L., Browne W. R., ChemSusChem 2013, 6, 1774–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen J., Draksharapu A., Angelone D., Unjaroen D., Padamati S. K., Hage R., Swart M., Duboc C., Browne W. R., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 9665–9674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Girerd J.-J., Banse F., Simaan A. J., Struct. Bond. 2000, 97, 145–177. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Costas M., Mehn M. P., Jensen M. P., Que L., Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 939–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bryliakov K. P., Talsi E. P., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 276, 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen K., Que L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6327–6337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen K., Costas M., Kim J., Tipton A. K., Que L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 3026–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oloo W. N., Fielding A. J., Que L. Jr., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 6438–6441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prat I., Company A., Postils V., Ribas X., Que L. Jr., Luis J. M., Costas M., Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 6724–6738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu S., Veach J. J., Oloo W. N., Peters K. C., Wang J., Perry R. H., Que L., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 8701–8704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prat I., Mathieson J. S., Güell M., Ribas X., Luis J. M., Cronin L., Costas M., Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 788–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Borrell M., Andris E., Navrátil R., Roithová J., Costas M., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 901–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olivo G., Cussó O., Borrell M., Costas M., J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 22, 425–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thibon A., Jollet V., Ribal C., Sénéchal-David K., Billon L., Sorokin A. B., Banse F., Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 2715–2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Faponle A. S., Quesne M. G., Sastri C. V., Banse F., de Visser S. P., Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 1221–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rebilly J.-N., Zhang W., Herrero C., Dridi H., Sénéchal-David K., Guillot R., Banse F., Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bang S., Park S., Lee Y.-M., Hong S., Cho K.-B., Nam W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7843–7847; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 7977–7981. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee Y.-M., Bang S., Kim Y. M., Cho J., Hong S., Nomura T., Ogura T., Troeppner O., Ivanović-Burmazović I., Sarangi R., et al., Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3917–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paria S., Que L. Jr., Paine T. K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 11129–11132; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 11325–11328. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Paria S., Chatterjee S., Paine T. K., Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 2810–2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chatterjee S., Paine T. K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9338–9342; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 9470–9474. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Martinho M., Dorlet P., Rivière E., Thibon A., Ribal C., Banse F., Girerd J.-J., Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 3182–3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Simaan A. J., Döpner S., Banse F., Bourcier S., Bouchoux G., Boussac A., Hildebrandt P., Girerd J.-J., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 2000, 1627–1633. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ségaud N., Anxolabéhère-Mallart E., Sénéchal-David K., Acosta-Rueda L., Robert M., Banse F., Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 639–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.From a simple electrostatic model based on the Born equation, it can be shown that the redox potential value of similar species increases with their size, as observed when going from L5 2 (Me substituent) to TPEN (pyridyl substituent). see Ref. [35].

- 35. Simaan J., Poussereau S., Blondin G., Girerd J. J., Defaye D., Philouze C., Guilhem J., Tchertanov L., Inorg. Chim. Acta 2000, 299, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ségaud N., Rebilly J.-N., Sénéchal-David K., Guillot R., Billon L., Baltaze J.-P., Farjon J., Reinaud O., Banse F., Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 691–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Comba P., Wadepohl H., Waleska A., Aust. J. Chem. 2014, 67, 398–404. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Herrero C., Quaranta A., Sircoglou M., Sénéchal-David K., Baron A., Marín I. M., Buron C., Baltaze J.-P., Leibl W., Aukauloo A., et al., Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 2323–2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Connelly N. G., Geiger W. E., Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 877–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hagen W. R., Biomolecular EPR Spectroscopy, CRC Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Simaan A. J., Banse F., Mialane P., Boussac A., Un S., Kargar-Grisel T., Bouchoux G., Girerd J. J., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 993–996. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Simaan A. J., Banse F., Girerd J.-J., Wieghardt K., Bill E., Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 6538–6540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.This reaction and its products were not analyzed further.

- 44.The amount of dissolved dioxygen could not be estimated by analysis of the fluorescence quenching due to our particular experimental condions. See Supporting Information for details.

- 45. Jasniewski A. J., Komor A. J., Lipscomb J. D., Que L. Jr., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10472–10485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chalupský J., Rokob T. A., Kurashige Y., Yanai T., Solomon E. I., Rulíšek L., Srnec M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15977–15991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bang S., Lee Y.-M., Hong S., Cho K.-B., Nishida Y., Seo M. S., Sarangi R., Fukuzumi S., Nam W., Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 934–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bae S. H., Lee Y.-M., Fukuzumi S., Nam W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 801–805; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 819–823. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li F., England J., Que L. Jr., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2134–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cheaib K., Mubarak M. Q. E., Sénéchal-David K., Herrero C., Guillot R., Clémancey M., Latour J.-M., de Visser S. P., Mahy J.-P., Banse F., et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 854–858; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 864–868. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bohn A., Chinaux-Chaix C., Cheaib K., Guillot R., Herrero C., Sénéchal-David K., Rebilly J.-N., Banse F., Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 17045–17051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kodera M., Kawahara Y., Hitomi Y., Nomura T., Ogura T., Kobayashi Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13236–13239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kodera M., Tsuji T., Yasunaga T., Kawahara Y., Hirano T., Hitomi Y., Nomura T., Ogura T., Kobayashi Y., Sajith P. K., Shiota Y., Yoshizawa K., Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 2282–2292. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kundu S., Matito E., Walleck S., Pfaff F. F., Heims F., Rábay B., Luis J. M., Company A., Braun B., Glaser T., Ray K., Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 2787–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Romain S., Bozoglian F., Sala X., Llobet A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2768–2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jackson T. A., Rohde J.-U., Seo M. S., Sastri C. V., DeHont R., Stubna A., Ohta T., Kitagawa T., Münck E., Nam W., Que L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12394–12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Klein J. E. M. N., Draksharapu A., Shokri A., Cramer C. J., Que L., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 5373–5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.