Abstract

Background

Although androgen deprivation therapy has known cardiovascular risks, it is unclear if its duration is related to cardiovascular risks. This study thus aimed to investigate the associations between gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist use duration and cardiovascular risks.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included adult patients with prostate cancer receiving GnRH agonists in Hong Kong during 1999–2021. Patients who switched to GnRH antagonists, underwent bilateral orchidectomy, had <6 months of GnRH agonist, prior myocardial infarction (MI), or prior stroke was excluded. All patients were followed up until September 2021 for a composite endpoint of MI and stroke. Multivariable competing‐risk regression using the Fine‐Gray subdistribution model was used, with mortality from any cause as the competing event.

Results

In total, 4038 patients were analyzed (median age 74.9 years old, interquartile range (IQR) 68.7–80.8 years old). Over a median follow‐up of 4.1 years (IQR 2.1–7.5 years), longer GnRH agonists use was associated with higher risk of the endpoint (sub‐hazard ratio per year 1.04 [1.01–1.06], p = 0.001), with those using GnRH agonists for ≥2 years having an estimated 23% increase in the sub‐hazard of the endpoint (sub‐hazard ratio 1.23 [1.04–1.46], p = 0.017).

Conclusion

Longer GnRH agonist use may be associated with greater cardiovascular risks.

Keywords: androgen deprivation therapy, cardio‐oncology, cohort, prostate cancer

1. INTRODUCTION

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is a pillar in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer (PCa). Despite the anticancer benefits of ADT, its associated cardiovascular risks have been under scrutiny since Keating et al. showed that gonadotropin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist use was associated with increased risks of myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death. 1 While studies have found prolonged ADT to be efficacious in high‐risk disease in terms of PCa outcomes, 2 little is known about the association between ADT duration and cardiovascular events. A 2021 scientific statement by the American Heart Association also recommended further research into the effects of the duration of hormonal therapies on cardiovascular outcomes. 3 This study thus aimed to investigate the association between GnRH agonist use duration and cardiovascular risks.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong– New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline. Patient consent was not needed as deidentified data were used. Data were obtained from the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS), a population‐based electronic database of patients attending public healthcare institutions in Hong Kong. Diagnoses were recorded by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth revision (ICD‐9) codes (Table S1) regardless of the year of entry, as ICD‐10 codes have not been implemented to date. CDARS has been used in previous studies and shown to have good coding accuracy. 4 , 5 , 6

Patients aged ≥18 years old with PCa who received any GnRH agonist (leuprorelin, triptorelin, or goserelin) during December 1999 and March 2021 were included. Patients who switched to GnRH antagonists, underwent bilateral orchidectomy, had <6 months of GnRH agonist, prior myocardial infarction (MI), or prior stroke were excluded. The endpoint was a composite of MI and stroke. Patients were followed up until September 31, 2021.

Continuous variables were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). To account for the high mortality rate, competing‐risk analysis with Fine‐Gray sub‐distribution model was performed, with mortality from any cause as the competing event. Univariable competing‐risk regression was performed for age, comorbidity, and medication use to identify significant confounders (p < 0.10). Multivariable competing‐risk regression adjusting for identified significant covariates was used to assess the association between GnRH agonist use duration and risk of the endpoint, using sub‐hazard ratios (SHR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) as summary statistics. GnRH agonist use duration was analyzed both as a continuous variable, and as a categorical variable with two years as the cut‐off which was chosen as the DART01/05 trial evaluated late cardiotoxicity of ADT up to two years. 7 All p‐values were two‐sided, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed on Stata (v16.1, StataCorp LLC).

3. RESULTS

Initially, 6871 patients were identified; 4038 were analyzed after applying the exclusion criteria (Figure S1; median age 74.9 years old, IQR 68.7–80.8 years old; median duration of GnRH agonist use 2.7 years, IQR 1.6–4.5 years), whose baseline characteristics were summarized in Table S2.

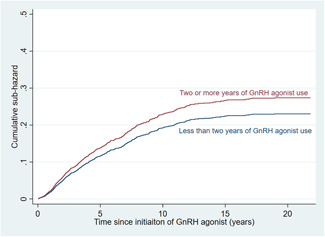

Over a median follow‐up of 4.1 years (IQR 2.1–7.5 years), the endpoint occurred in 735 patients (18.2%; 347 (8.6%) had MI, 380 (9.4%) had stroke, and 8 (0.2%) had both); 1623 (40.2%) died without having had the endpoint. Results of univariable analysis were summarized in Table S3, with longer use of GnRH agonists showing a nominal association with the risk of the endpoint (SHR per year of GnRH agonist use 1.02 [1.00–1.04], p = 0.067). In multivariable analysis adjusting for significant covariates, longer use of GnRH agonists was associated with higher risk of the endpoint (SHR 1.04 [1.01–1.06], p = 0.001), with those using GnRH agonists for ≥2 years (N = 2667, 66.1%) having an estimated 23% increase in the sub‐hazard of the endpoint (SHR 1.23 [1.04–1.46], p = 0.017; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative sub‐hazard curve showing that patients with ≥2 years of gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist use had significantly higher risk of the endpoint than those with <2 years of GnRH agonist use (sub‐hazard ratio 1.23 [1.04–1.46], p = 0.017). [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

Studies that investigated the link between ADT duration and cardiovascular risks present a mixed picture. A secondary analysis of randomized controlled trials by D'Amico and colleagues observed that patients on 6–8 months of ADT did not have significantly different cardiovascular risks compared to those on 3 months of ADT. 8 Meanwhile, another more recent study by Gong and colleagues showed that >6 months of ADT was associated with higher risks of cardiovascular death and worse cardiorespiratory fitness compared to short‐term use (<6 months). 9 In that study, interestingly, the median duration of ADT in patients with >6 months of ADT was 28 months, which was substantially longer than what D'Amico and colleagues included as the group with longer ADT duration (6–8 months of ADT), 8 and closer to our subgroup of at least 2 years of ADT. It is thus possible that significant differences in cardiovascular risks only become apparent with longer durations of ADT, and further studies of longer ADT durations are needed to verify our findings.

Whilst some have briefly investigated the effects of longer‐term ADT in observational cohorts, the effects of competing events (e.g. mortality) were not accounted for, which probably contributed to the associations between longer ADT durations ADT and reduced cardiovascular risks in some reports. 10 , 11 Recognizing the bias that competing events may cause, our study addressed the effects of mortality as a competing event, observing that long‐term (≥2 year) GnRH agonist use was associated with significantly higher cardiovascular risks. Given the population‐based nature of our data, these findings may reflect real‐world practice. Clinically, these findings should prompt clinicians to consider intensifying cardiovascular monitoring in patients on prolonged GnRH agonist therapy, such as ≥2 years. Our findings also facilitate better risk‐benefit analysis of increasing ADT duration, a gap in the evidence that has been recognized to be a research priority. 3 Further studies are warranted to better delineate the time‐dependency of ADT‐related cardiotoxicity.

Nonetheless, this study was limited by its observational nature, predisposing to residual confounding. Specifically, metastatic patients may use androgen receptor signaling inhibitors which are associated with cardiovascular events. Nevertheless, the multivariable adjustment included these agents, partially addressing this limitation. The retrospective nature also barred any meaningful study of cardiac biomarkers, as the inclusion of any such measurement would have resulted in significant bias by indication, selecting for patients who had worse cardiovascular outcomes. Furthermore, cancer staging data was unavailable. These should be considered in future studies. Lastly, diagnostic data could not be adjudicated; nonetheless, diagnostic codes were input by treating clinicians independent of the authors, and previous studies of CDARS have shown good coding accuracy, especially for cardiovascular outcomes. 5

5. CONCLUSIONS

Longer GnRH agonist use may be associated with increased cardiovascular risk, underscoring the need for studies investigating the time‐dependency of ADT‐related cardiotoxicity. These findings should be considered in shared decision‐making in the treatment of PCa.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DISCLOSURES

No material from other sources was used. This is not a registered study as it is not a clinical trial.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

No funding was obtained for this study. ECD is funded in part through the Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute (P30 CA008748). GT is in part supported by the Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (Project number: TJYXZDXK‐029A).

Chan JSK, Tang P, Hui JMH, et al. Association between duration of gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist use and cardiovascular risks: A population‐based competing‐risk analysis. The Prostate. 2022;82:1477‐1480. 10.1002/pros.24423

Jeffrey Shi Kai Chan and Pias Tang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Gary Tse, Email: gary.tse@kmms.ac.uk.

Chi Fai Ng, Email: ngcf@surgery.cuhk.edu.hk.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All underlying data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Keating NL, O'Malley AJ, Smith MR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(27):4448‐4456. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schaeffer E, Srinivas S, Antonarakis ES, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: prostate cancer, version 1.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(2):134‐143. 10.6004/JNCCN.2021.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Okwuosa TM, Morgans A, Rhee JW, et al. Impact of hormonal therapies for treatment of hormone‐dependent cancers (breast and prostate) on the cardiovascular system: effects and modifications: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Genomic Precis Med. 2021;14(3):E000082. 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chan JSK, Zhou J, Lee S, et al. Fragmented QRS is independently predictive of long‐term adverse clinical outcomes in asian patients hospitalized for heart failure: a retrospective cohort study. Front Cardiovasc Med . 2021;1634. 10.3389/FCVM.2021.738417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5. Wong AYS, Root A, Douglas IJ, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes associated with use of clarithromycin: population based study. BMJ . 2016;352. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. Chan JSK, Satti DI, Lee YHA, et al. High visit‐to‐visit cholesterol variability predicts heart failure and adverse cardiovascular events: a population‐based cohort study. Eur J Prev Cardiol . 2022. 10.1093/EURJPC/ZWAC097 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7. Zapatero A, Guerrero A, Maldonado X, et al. Late radiation and cardiovascular adverse effects after androgen deprivation and high‐dose radiation therapy in prostate cancer: results from the DART 01/05 randomized phase 3 trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(2):341‐348. 10.1016/J.IJROBP.2016.06.2445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'amico AV, Denham JW, Crook J, et al. Influence of androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer on the frequency and timing of fatal myocardial infarctions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2420‐2425. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gong J, Payne D, Caron J, et al. Reduced cardiorespiratory fitness and increased cardiovascular mortality after prolonged androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. JACC CardioOncology. 2020;2(4):553‐563. 10.1016/J.JACCAO.2020.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alibhai SMH, Duong‐Hua M, Sutradhar R, et al. Impact of androgen deprivation therapy on cardiovascular disease and diabetes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3452‐3458. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okubo M, Nakayama H, Itonaga T, et al. Impact of the duration of hormonal therapy following radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(1):255‐259. 10.3892/OL.2015.3216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

All underlying data are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.