Abstract

Highly‐efficient and selective one‐pot/two‐step modular double addition of different highly polar organometallic reagents (RLi/RMgX) to nitriles en route to asymmetric tertiary alcohols (without the need for isolation/purification of any halfway reaction intermediate) has been studied, for the first time, in the absence of external/additional organic solvents (neat conditions), at room temperature and under air/moisture (no protecting atmosphere is required), which are generally forbidden reaction conditions in the field of highly‐reactive organolithium/organomagnesium reagents. The one‐pot modular tandem protocol demonstrated high chemoselectivity with a broad range of nitriles, as no side reactions (Li/halogen exchange, ortho‐lithiations or benzylic metalations) were detected. Finally, this protocol could be scaled up, thus proving that this environmentally friendly methodology is amenable for a possible applied synthesis of asymmetric tertiary alcohols under bench type reaction conditions and in the absence of external organic solvents.

Keywords: alcohols, green chemistry, neat conditions, nitriles, organolithium reagents

Under neat conditions: The aerobic and room temperature compatible double addition of s‐block organometallic reagents into nitriles, in the absence of any external organic solvent, is reported. Thus, direct conversion of nitriles into asymmetric tertiary alcohols is achieved through a one‐pot/two‐steps modular process, without tedious and energy consuming halfway isolation/purification steps needed.

Introduction

In the last decade, the constantly growing chemical portfolio of highly‐polar s‐block organometallic reagents [specially for the case of organolithium (RLi) and Grignard (RMgX) derivatives] [1] has been able to expand its influence into previously forbidden synthetic fields, ranging from homogenous catalysis [2] to sustainable chemistry. [3] This change of paradigm is directly related with new findings, reported by different research groups worldwide, [4] which refuted the well‐established wisdom related with the fact that organolithium/organomagnesium chemistry should always be performed under strict, tedious and energy‐consuming Schlenk‐type reactions conditions, usually requiring low temperature (−78 °C), inert atmosphere (N2 or Ar) and meticulously dried, toxic and non‐biorenewable volatile organic solvents (ethereal compounds). [1] In this field, our research group and others have demonstrated that both organolithium and Grignard reagents can make their synthetic job even under greener and bench‐type conditions by fine‐tuning of the reaction parameters under study,[ 4 , 5 ] such as the solvent employed [in most cases protic and sustainable solvents like water, glycerol or deep eutectic solvents (DESs) are tolerated]. Going one step further, and bearing in mind the following phrase (coined by P. T. Anastas and J. C. Warner, usually considered the fathers of the Green Chemistry concept): “The best solvent is no solvent”, [6] Feringa and coworkers firstly described the possibility to promote a more sustainable, faster and scalable direct Pd‐catalyzed coupling of organolithium compounds without the need of any external/additional organic solvents. [7] In this vein, and following this “solventless” idea, we have successfully extended this s‐block‐based sustainable methodology to the addition of RLi/RMgX reagents into cyclic carbonates. [8]

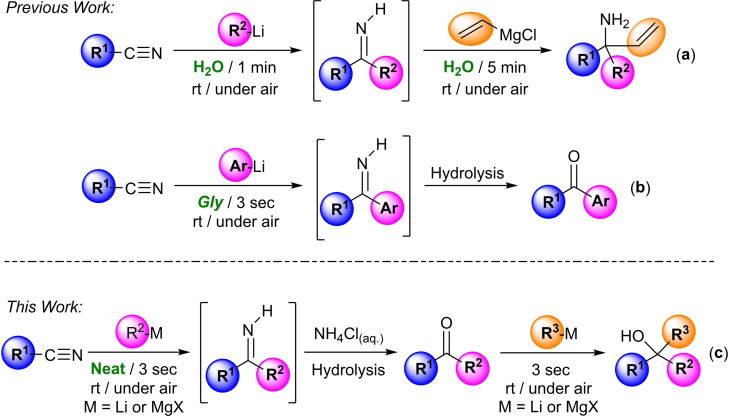

Aside from the Green Chemistry point of view, the previous studies on the use of polar organometallic compounds in the aforementioned unconventional and biorenewable reaction media (water, glycerol or DESs) also revealed that, in some cases, unique chemoselectivities and enhanced performances can be accomplished under these non‐Schlenk‐type conditions.[ 4 , 5 ] In this sense, Capriati and co‐workers recently reported the sequential double addition of highly‐polar reagents (RLi/RMgX) to nitriles which, in contrast to classical methods (that require inert atmospheres, dried organic solvents and low temperatures), proceeds quickly, efficiently and chemoselectively at room temperature, under air and using water as the only reaction media, thus giving rise to the desired tertiary carbinamines in yields up to 98 % (Scheme 1a). [4d] Taking into account this idea and building on our recent findings on the nucleophilic addition of organolithium reagents (RLi) to aromatic nitriles in water or glycerol to produce the corresponding ketones (Scheme 1b), [5b] we present the first successful modular double addition of different organolithium/Grignard reagents at room temperature, under air and in the absence of any external/additional organic solvent (apart from the commercially‐available solution of the either RLi or RMgX reagents employed) into nitriles, giving rise to non‐symmetrical and highly‐substituted tertiary alcohols (see Scheme 1c). The overall transformation takes place in a sequential and modular one‐pot fashion (without the need of any halfway isolation/purification of reaction intermediates) and involves the following three steps: i) fast and selective RLi/RMgX‐addition into the starting nitriles; ii) hydrolyzation of the lithium/magnesium imide; and iii) chemoselective and fast addition of RLi/RMgX reagents into transiently preformed ketones. Moreover, this sequential and modular double‐addition route provides selective access to either ketones or non‐symmetrical tertiary alcohols, which are often considered components of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), natural products, agrochemicals or synthetic materials. [9]

Scheme 1.

Design of one‐pot tandem combinations that rely on the addition of polar s‐block reagents (RLi/RMgX) into nitriles in protic and sustainable reaction media [water or glycerol (Gly)] or in the absence of external/additional organic solvents, working at room temperature and under air.

Results and Discussion

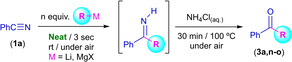

To start with our investigations, we selected, as a model process to study, the reaction between commercially available benzonitrile (1a) and MeLi, in the presence of air/moisture, at room temperature and, for the first time, in the absence of any additional/external organic solvent, this is by using directly the commercially available MeLi solution (diethyl ether) as solvent (Scheme 2). [10] Surprisingly, by using only one equivalent of MeLi, benzonitrile (1a, 0.5 mmol) was converted into imine 2a in quantitative conversion (99 %) after only 3 s of reaction. At this point, we would like to mention that, in this case and for the first time in this chemistry, we are not using an excess of the organolithium reagents (1 : 1 stoichiometry is employed). However, in the vast majority of the previously reported works in this field,[ 4 , 5 ] excess of the RLi reagents (2–3 equivalents) is mandatory to achieve good final yields of the desired products. Subsequent addition of a saturated aqueous solution of NH4Cl at room temperature to the reaction media allows the complete conversion of imine 2a into the desired acetophenone (3a) after three hours of stirring at room temperature. In order to speed up this hydrolyzing process, heating of the reaction medium at 100 °C permits full conversion into ketone 3a after only 30 min of reaction. Pleasingly, the reaction could also be scaled‐up by reacting 10 mmol of 1a with 1 equivalent of MeLi, thus forming acetophenone (3a) in quantitative yield (99 %). [11]

Scheme 2.

One‐pot combination of the selective and fast addition of MeLi into benzonitrile (1a) under air, at room temperature and in the absence of any additional/external solvent with the concomitant hydrolysis of imine (2a) into acetophenone 3a.

Once established the best conditions for the addition of MeLi into Ph−C≡N (1a) with no additional solvents, the scope of suitable and commercially‐available nitriles was explored (Scheme 3). To our delight, the optimized reaction conditions (room temperature, under air/moisture and 1 : 1 stoichiometry) for the synthesis of acetophenone (3a) could be successfully applied to a variety of aromatic nitriles (1a–j), giving rise to a diversity of aromatic methyl ketones 3a–j in good (65 %) to quantitative (99 %) yields, thus indicating the generality of this reaction. In this vein, when the phenyl group of the aromatic nitrile is substituted with an electron‐donating group [like methyl (1b–d, 98–85 %) or methoxy substituents (1e–g, 94–81 %)] the yields of the corresponding ketones 3b–g only suffer a small erosion, finding a similar trend when the phenyl group is replaced by a naphthyl substituent (1h, 90 %). Conversely, when electron‐withdrawing groups are present in para‐position of the phenyl group (Br in 1i and CF3 in 1j) the yields of the final ketones 3i–j decreased considerably (70 % and 65 %, respectively). At this point, it is important to note that although electronic properties of these substituents in the aromatic ring produce a considerable decrease in the yield of the final ketones, the presence of ortho‐substituents in the starting nitriles (1d and 1g) have only a modest effect. Importantly, we always observed total chemoselectivity for the process under study (even working at room temperature, in the presence of air/moisture and in a 1 : 1 stoichiometry), as possible competing processes with the addition reaction of RLi reagents to nitriles, [12] like: i) metalation of benzylic position in substrates 3b–d (i. e., lateral lithiation); ii) directed‐ortho‐metalation (DoM) processes in nitriles containing MeO (1e–g) or CF3 (1j) groups; and iii) Li‐halogen exchange processes in nitrile 1i; were not detected. Regarding the physical state of the starting nitriles, it is important to mention that our protocol is not only applicable to liquid nitriles (e. g., 1a–d) but also to solid nitriles (like 1e–g) maintaining in all cases good to excellent yields. Trying to push our methodology to its limits, we decided to extend our studies to heteroaromatic (1k–l) or aliphatic (1m) nitriles. In both cases, lower yields were obtained for the desired ketones 3k–m. These results are in good agreement with our previous studies in the addition of RLi reagents into aliphatic nitriles in protic solvents (water or glycerol). [5b] Finally, aromatic nitriles containing NH2 or OH groups in para‐position, like 4‐hydroxybenzonitrile or 4‐aminobenzonitrile (which are sparingly soluble solids due to the strength of the intermolecular aggregation of these compounds) are not good candidates for our addition process.

Scheme 3.

One‐pot protocol for the synthesis of methyl ketones 3a–m using different nitriles (1a–m) and 1 equivalent of MeLi under air, at room temperature and in the absence of any additional/external solvent.

Next, and to have a full picture of our one‐pot process for the synthesis of aromatic ketones, we decided to examine the addition of other highly‐polar s‐block organometallic reagents (RLi/RMgX) into commercially available benzonitrile (1a), under the previously optimized reaction conditions (in the presence of air/moisture, at room temperature and in the absence of any additional/external organic solvents, Table 1). We initiated our studies by using other commercially available and aliphatic organolithium reagents such as EtLi and n‐BuLi. Thus, for the specific case of EtLi and using 1 : 1 stoichiometric condition, we observed a dramatic decrease in the yield of the final propiophenone (3n, 15 %, entry 2 in Table 1). To try to explain this experimental observation, we should put first the focus on the concentration of the commercially available solution of EtLi employed. In this sense, the higher concentration of the commercially available solution of MeLi (1.6 M) allows us to use a smaller volume of the ethereal solvent (Et2O, 0.313 mL) while for the diluted version of the commercially solution of EtLi (0.5 M), we need to increase the volume of the hydrocarbon‐based solvent employed up to three times (benzene/cyclohexane, 1 mL). In the same line, we could invoke the capability of the ethereal solvent present in the commercial solution of MeLi to break down the oligomeric species (usually present in RLi compounds) into more reactive monomeric organometallic species. In the case of EtLi, to try to increase the yield of the desired propiophenone (3n, 79 %), it is mandatory to move to a 2 : 1 stoichiometry (entry 3, Table 1). In good agreement with the experimental observation that higher concentrated RLi solutions are preferred in our one‐pot tandem protocol, we found that just 1 equivalent of a highly‐concentrated commercially available solution of n‐BuLi (2.5 M) is capable to trigger the formation of the ketone 3o in good yield (74 %, entry 4, Table 1). Again, we could increase the reaction yield for ketone 3o just by using two equivalents of n‐BuLi (86 %, entry 5, Table 1). Moreover, we demonstrated that our one‐pot tandem protocol (in the absence of any external/additional organic solvent) also tolerates the use of aromatic (PhLi ; entry 6, Table 1) or heteroaromatic (2‐thienyl lithium; entry 7, Table 1) organolithium reagents, giving rise to the corresponding ketones in good yields (60–84 %). The intermediate imine bearing the 2‐thienyl group (3q) requires 4 h of acidic hydrolysis, probably due to the mayor stability of this compound. Similarly, trimethylsilyl‐containing organolithium reagents [(CH3)3SiCH2Li; entry 8, Table 1] can be also employed in our protocol (1 : 3 stoichiometry is needed), although we observed a spontaneous Si−C cleavage under the hydrolyzing reaction conditions, [13] thus giving rise to the acetophenone (3a) in 58 % yield. For highly steric demanding and reactive organolithium reagents (i. e., t‐BuLi), no addition reaction into benzonitrile (1a) was observed. Finally, one of the most important advantages of this new protocol (performed in the absence of external solvents) is related with the fact that Grignard reagents (n‐BuMgCl; entry 9, Table 2) can be successfully added to benzonitrile (1a), working at room temperature and under air. This finding overpasses one of the most important drawbacks of our previously reported methodology in glycerol, [5b] in which Grignard reagents (RMgX) were not capable to trigger their addition reaction into nitriles.

Table 1.

Addition of organolithium/Grignard reagents (RLi/RMgX) to benzonitrile (1a) under air, at room temperature and in the absence of any additional/external solvent.[a]

|

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entry |

R‐Li[b] |

Equiv. |

Ketone |

Yield [%][c] |

|

1 |

MeLi |

1 |

3a |

99 |

|

2 |

EtLi |

1 |

3n |

15 |

|

3 |

EtLi |

2 |

3n |

79 |

|

4 |

n‐BuLi |

1 |

3o |

74 |

|

5 |

n‐BuLi |

2 |

3o |

86 |

|

6 |

PhLi |

1 |

3p |

60 |

|

7 |

2‐thienylLi |

1 |

3q |

84 |

|

8 |

(CH3)3SiCH2Li |

3 |

3a |

58 |

|

9 |

n‐BuMgCl |

3 |

3o |

61 |

[a] General conditions: reactions performed under air/moisture, at room temperature and in the absence of external organic solvents, using 0.5 mmol of benzonitrile (1a). [b] Commercial solution of MeLi (1.6 M in diethyl ether), EtLi (0.5 M in benzene/cyclohexane), n‐BuLi (2.5 M in hexanes), PhLi (1.9 M in n‐Bu2O), 2‐thienyl lithium [1 M in tetrahydrofuran (THF)/hexanes], (CH3)3SiCH2Li (1 M in pentane) and n‐BuMgCl (2 M in Et2O) were employed. [c] Yields determined by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy using trimethoxybenzene as internal standard (0.5 mmol) (see Supporting Information).

Table 2.

One‐pot/two‐step modular double addition of different organolithium or organomagnesium reagents to benzonitrile (1a) under air, at room temperature and in the absence of any additional solvent.[a]

|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entry |

R1Li[b] |

Equiv. |

3a,n–q [%][c] |

R2Li[b] |

Equiv. |

4a–j [%][c] |

|

1 |

MeLi |

1 |

3a (99) |

n‐BuLi |

1 |

4a (52) |

|

2 |

MeLi |

1 |

3a (99) |

n‐BuLi |

2 |

4a (56) |

|

3 |

MeLi |

1 |

3a (99) |

n‐BuLi |

3 |

4a (68) |

|

4 |

MeLi |

1 |

3a (99) |

EtLi |

3 |

4b (52) |

|

5 |

EtLi |

2 |

3n (79) |

n‐BuLi |

3 |

4c (38) |

|

6 |

EtLi |

2 |

3n (79) |

MeLi |

3 |

4b (45) |

|

7 |

n‐BuLi |

2 |

3o (86) |

MeLi |

3 |

4a (66) |

|

8 |

n‐BuLi |

2 |

3o (86) |

EtLi |

3 |

4c (74) |

|

9 |

MeLi |

1 |

3a (99) |

TMSCH2Li |

3 |

4d (52) |

|

10 |

EtLi |

2 |

3n (79) |

TMSCH2Li |

3 |

4e (76) |

|

11 |

n‐BuLi |

2 |

3o (86) |

TMSCH2Li |

3 |

4f (54) |

|

12 |

MeLi |

1 |

3a (99) |

ThienLi |

3 |

4g (56) |

|

13 |

EtLi |

2 |

3n (79) |

ThienLi |

3 |

4h (51) |

|

14 |

n‐BuLi |

2 |

3o (86) |

ThienLi |

3 |

4i (65) |

|

15 |

ThienLi |

1 |

3q (84) |

MeLi |

3 |

4g (55) |

|

16 |

ThienLi |

1 |

3q (84) |

EtLi |

3 |

4h (30) |

|

17 |

ThienLi |

1 |

3q (84) |

n‐BuLi |

3 |

4i (24) |

|

18 |

MeLi |

1 |

3a (99) |

i‐PrMgCl2Li |

3 |

4j (25) |

[a] General conditions: reactions performed under air/moisture, at room temperature and in the absence of external organic solvents, using 0.5 mmol of benzonitrile (1a). [b] Commercial solution of MeLi (1.6 M in diethyl ether), EtLi (0.5 M in benzene/cyclohexane), n‐BuLi (2.5 M in hexanes), TMSCH2Li [TMS=(CH3)3Si; 1 M in pentane], ThienLi (Thien=2‐thienyl; 1 M in THF/hexanes), and i‐PrMgCl2Li (1.3 M in THF) were employed. [c] Yields determined by 1H NMR using trimethoxybenzene as internal standard (0.5 mmol) (see Supporting Information).

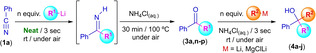

Recently, we have demonstrated the possibility to design one‐pot tandem protocols in which one of the steps is based on the fast and chemoselective addition of RLi reagents into transiently formed ketones,[ 4g , 5a , 5i ] under air/moisture and at room temperature, by using protic and sustainable solvents (water or DESs) as green reaction media, giving rise to the desired highly substituted tertiary alcohols (without any isolation or halfway purification step needed). In the light of these results, and taking into account that our new protocol allows us to trigger the quantitative conversion of benzonitrile (1a) into acetophenone (3a) when MeLi (1 equiv., Scheme 2) is added at room temperature, under air and in the absence of any additional/external solvent, we envisioned a modular combination of this first step with a subsequent chemoselective and fast addition of other RLi/RMgX reagent, thus opening the door to the straightforward and selective synthesis of a library of non‐symmetrical tertiary alcohols, via a one‐pot/two‐step modular tandem protocol under greener reaction conditions and in the absence of any external/additional organic solvent (Table 2). Generally, the double addition of RLi/RMgX reagents into carbonyl compounds is restricted to ester, giving rise to the corresponding symmetric alcohols. [5g] However, our one‐pot tandem protocol overpasses this limitation, allowing us the direct, modular and more sustainable synthesis of tertiary alcohols containing three different substituents in its structure [with general formula RR1R2C(OH)], without the need of any halfway isolation/purification steps (Table 2).

Thus, we initiated our studies by exploring the combination of the aforementioned addition of MeLi into benzonitrile (1a), under air/moisture, at room temperature and in the absence of external/additional solvents followed by the subsequent hydrolysis of the imine intermediate (entry 1, Table 2). After reaching room temperature and without any isolation/purification steps, one equivalent of n‐BuLi was directly added to the obtained aqueous reaction media. Remarkably, the almost instantaneous and chemoselective formation of the non‐symmetric tertiary alcohol 4a was observed, finding a significantly improved yield of 68 % when three equivalents of n‐BuLi were employed (compare entries 1–3 in Table 2). At this point, we would like to highlight that, for the first time in this chemistry, we have been able to promote the addition of a RLi reagent into acetophenone (3a) in an acidic aqueous media (pH=4.6 for a saturated aqueous solution of NH4Cl). By replacing MeLi in the first step of the one‐pot/two‐step modular protocol by other organolithium reagents like EtLi (entries 5–6, Table 2) or n‐BuLi (entry 7–8, Table 2), we observed lower to similar conversions of the final tertiary alcohols 4a–c, even if non‐quantitative conversion of benzonitrile (1a) into the intermediate ketones 3n,o was detected (79 % and 86 %, respectively). However, we should mention that, in all the cases under study, formation of the non‐symmetric tertiary alcohols 4a–c occurs chemoselectively, with no side products observed in the crude reaction mixture (only unreacted starting materials). At this point, we should mention that, not only aliphatic and primary RLi reagents but also heteroaromatic [like 2‐thienyl lithium (ThienLi); entries 12–17, Table 2] or silylated [TMSCH2Li (TMS=(CH3)3Si; entries 9–11, Table 2) organolithium reagents can be employed in our one‐pot tandem modular protocol in the absence of external/additional organic solvents, working at room temperature and under air. Finally, we decided to study the scope of our one‐pot/two‐steps tandem protocol in terms of the nature of the polar organometallic reagent employed in the second step. In this sense, and although neutral Grignard reagents (like MeMgCl, H2C=CHMgBr or PhMgBr) are not capable to promote their addition into acetophenone (3a) when an acidic saturated solution of NH4Cl is used as reaction media, [14] we found (for the first time in this field) that a highly nucleophilic anionic magnesiate,[ 2b , 15 ] in this case the prototypical Turbo‐Grignard i‐PrMgCl2Li (firstly reported by Knochel), [16] is capable of promoting its addition into acetophenone (3a) giving rise to the tertiary alcohol 4j even in an acidic reaction media (saturated NH4Cl aqueous solution).

Once we have set the best reaction conditions for our unprecedented one‐pot/two‐step process that allows selective conversion of benzonitrile (1a) into non‐symmetric tertiary alcohols through modular addition of RLi/RMgX reagents: i) under air/moisture; ii) at room temperature; and iii) without the addition of any external/additional organic solvent, we decided to focus our attention on the study of the nature of the starting aromatic nitriles (Scheme 4). Thus, we observed a moderate increase of the final yield of the non‐symmetric alcohols 4k,n when the starting aromatic nitriles are substituted with an electron‐donating group in para‐position [Me (4k, 71 %) or MeO (4n, 80 %)]. However, no effect on the yield of alcohols 4l,o was observed when the same electron‐donating groups are present in the meta‐position of the aromatic ring [Me (4l, 66 %) or MeO (4o, 67 %)]. Contrastingly, when the phenyl group is substituted in ortho‐position with a methyl group (4m), the yield decreased up to 38 %, probably due to the steric hindrance of this methyl substituent. In this vein, when the aromatic ring contains a methoxy group in the ortho‐position, we detected an increase in the yield of alcohol 4p (84 %). This experimental observation seems to indicate that the inductive effect of the MeO group is dominant over both the conjugative and the steric effects of this group in ortho‐position. For the specific case of aromatic rings containing electron‐withdrawing groups, like Br (4q) or CF3 (4r) in para‐position, slight decrease in yields of the final alcohols was observed (57 % and 49 %, respectively). At this point and after all these studies, it is important to mention that no side reactions like: i) Li/halogen exchange (Br in 4q); ii) directed ortho‐lithiations (MeO in 4p–o or CF3 in 4r); and iii) benzylic metalations (Me groups in 4k–m) were detected in any of these one‐pot/two‐step protocols, thus demonstrating the high chemoselectivity of our modular double addition reaction.

Scheme 4.

One‐pot/two‐steps modular double addition of MeLi and n‐BuLi reagents to different aromatic nitriles (1a–j) under air, at room temperature and in the absence of any additional/external solvent.

For completeness of our study, we demonstrated that replacing of phenyl group in the starting nitriles by a naphthyl substituent (1h) did not affect the yield of the final non‐symmetric alcohol 4s (68 %). Finally, we assayed on a larger scale of the corresponding reaction between benzonitrile (1a, 10 mmol), 1 equiv. of MeLi, and 3 equiv. of n‐BuLi, following the described one‐pot/two‐step protocol and achieving a yield of 64 %, very similar to that obtained using a smaller scale. This proves the potential of this process to obtain tertiary alcohols on the gram scale.

Conclusion

In summary, this work has demonstrated that selective one‐pot/two‐step modular double addition of organolithium/organomagnesium reagents into nitriles (without any halfway isolation/purification steps needed), can be carried out under bench‐type and sustainable reaction conditions (presence of air/moisture, room temperature and in the absence of any external organic solvent) en route to either aromatic ketones or asymmetric tertiary alcohols. Moreover, it is important to mention the high chemoselectivity of our tandem synthetic protocol which is compatible with a variety of functional groups in the starting nitriles, without observing any undesired side reactions typically associated with the use of highly polar organolithium reagents. Finally, by using a scaled‐up synthetic protocol, we proved the possible use of our methodology as a new and more environmentally friendly tool for the applied synthesis of highly‐substituted and asymmetric tertiary alcohols.

Experimental Section

General considerations

All reagents were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Methyl lithium (1.6 M in diethyl ether), n‐butyl lithium (2.5 M solution in hexanes), ethyl lithium (0.5 M in cyclohexane/benzene), phenyl lithium [1.9 M in di(n‐butyl)ether], 2‐thienyl lithium (1 M in THF/hexanes), (CH3)3SiCH2Li (1 M in pentane), n‐butyl magnesium chloride (2 M in THF) and i‐PrMgCl2Li (1.3 M in THF) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Concentrations of all organolithium reagents were established by titration with l‐menthol, [17] and the concentration of Grignard reagents were determined by titrating against iodine. [18]

Infrared spectra were recorded on a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer, using an ATR (Attenuated total reflection) accessory. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance Neo 400 spectrometer operating at 400.13 MHz for 1H, 100.62 MHz for 13C and 376 MHz for 19F. All 13C and 19F spectra were proton decoupled. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were referenced against the appropriate solvent signal. 19F NMR spectra were referenced against CFCl3. Characterisation details, including 1H, 19F and 13C{1H} NMR spectra, for compounds 3a–q and 4a–s are included in the Supporting Information.

Synthesis of ketones 3a–q

Syntheses were performed under air and at room temperature. A glass tube was charged with the appropriate nitrile (1a–m, 0.5 mmol) and the corresponding organolithium/organomagnesium reagent was added with a vigorous stirring. After 3 s of stirring, the reaction was quenched with 2 mL of a saturated solution of NH4Cl and then heated to 100 °C for 30 min (4 h for compound 3q). After reaching room temperature, 5 mL of distilled water was added, and the mixture was extracted with 2‐MeTHF (3×5 mL). The combined organic phases were dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and the solvent was concentrated in vacuo. Yields of the reaction crudes were determined by 1H NMR using 1,3,5‐trimethoxybenzene as internal standard (0.5 mmol). Separation and purification of every compound was carried out using TLC (Thin Layer Chromatography) glass plate silica (employing hexane:ethyl acetate mixtures). All reactions were done in triplicate to ensure good reproducibility of obtained yields.

Synthesis of tertiary alcohols 4a–s

Syntheses were performed under air and at room temperature. A glass tube was charged with the appropriate nitrile (1a–j, 0.5 mmol) and the corresponding lithium reagent was added with a vigorous stirring. After 3 s of stirring, the reaction was quenched with 2 mL of a saturated solution of NH4Cl and then heated to 100 °C for 30 min. After reaching room temperature, 3 equivalents of the second organolithium/organomagnesium reagent were added and then the mixture was extracted with 2‐MeTHF (3×5 mL). The combined organic phases were dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and the solvent was concentrated in vacuo. Yields of the reaction crudes were determined by 1H NMR using 1,3,5‐trimethoxybenzene as internal standard (0.5 mmol). Separation and purification of every compound was carried out using TLC glass plate silica (employing hexane:ethyl acetate mixtures). All reactions were done in triplicate to ensure good reproducibility of obtained yields.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

J.G.A. thanks MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (Project numbers CTQ2016‐75986‐P, RED2018‐102387‐T and PID2020‐113473GB‐I00) for financial support. D. E., F. C.‐H., B.P‐C., and A. A. acknowledge financial support from MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (Project numbers PID2020‐117353GB‐I00 and RED2018‐102387‐T) and the Universidad Castilla‐La Mancha (Project number 2021‐GRIN‐30992). D. E. thanks the Junta de Comunidades de Castilla‐La Mancha and EU for financial support through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF; project SBPLY/19/180501/000137).

In memory of Prof. Dr. Fernando Aznar, a pioneer in the study of organometallic chemistry at the University of Oviedo.

D. Elorriaga, F. Carrillo-Hermosilla, B. Parra-Cadenas, A. Antiñolo, J. García-Álvarez, ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202201348.

Contributor Information

Dr. David Elorriaga, Email: david.elorriaga@uclm.es.

Prof. Dr. Fernando Carrillo‐Hermosilla, Email: fernando.carrillo@uclm.es.

Dr. Joaquín García‐Álvarez, Email: garciajoaquin@uniovi.es.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.

References

- 1.For selected reviews/books dealing with organolithium chemistry, see:

- 1a. Clayden J., in Organolithiums: selectivity for synthesis, Pergamon, Oxford, 2002; [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Rappoport Z., Marek I., in The chemistry of organolithium compounds, Wiley, Chichester, 2005; [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Capriati V., Perna F. M., Salomone A., Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 14204–14210; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d. Wietelmann U., Klett J., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2018, 644, 194–204. For selected reviews/books dealing with organomagnesium chemistry, see: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1e. Garst J. F., Soriaga M. P., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004, 248, 623–652; [Google Scholar]

- 1f. The Chemistry of Organomagnesium Compounds, (Eds.: Rappoport Z., Marek I.), Patai Series, Wiley, Chichester, 2008; [Google Scholar]

- 1g. Seyferth D., Organometallics 2009, 28, 1598–1600. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Leitao E., Jurca T., Manners I., Nat. Chem. 2013, 5, 817–829; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Gil-Negrete J. M., Hevia E., Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 1982–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For recent reviews which cover the use of RLi/RMgX reagents under “greener” reaction conditions see:

- 3a. García-Álvarez J., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 31, 5147–5157; [Google Scholar]

- 3b. García-Álvarez J., Hevia E., Capriati V., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 31, 6779–6799; [Google Scholar]

- 3c. García-Álvarez J., Hevia E., Capriati V., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 14854–14863; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Hevia E., Chimia 2020, 74, 681–688; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3e. Gentner T. X., Mulvey R. E., Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 9331–9348; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 9247–9262; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3f. Perna F. M., Vitale P., Capriati V., Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 30, 100487; [Google Scholar]

- 3g. García-Garrido S. E., Presa Soto A., Hevia E., García-Álvarez J., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 31, 3116–3130. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For selected works in this field, see:

- 4a. Vidal C., García-Álvarez J., Hernán-Gómez A., Kennedy A. R., Hevia E., Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 6079–6083; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 5969–5973; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Cicco L., Sblendorio S., Mansueto R., Perna F. M., Salomone A., Florio S., Capriati V., Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 1192–1199; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Vidal C., García-Álvarez J., Hernán-Gómez A., Kennedy A. R., Hevia E., Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 16379–16382; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 16145–16148; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Dilauro G., Dell'Aera M., Vitale P., Capriati V., Perna F. M., Angew. Chem. 2017, 126, 10334–10337; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10200–10203; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4e. Mulks F. F., Bole L. J., Davin L., Hernán-Gómez A., Kennedy A., García-Alvarez J., Hevia E., Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 19183–19188; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 19021–19026; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4f. Dilauro G., Quivelli A. F., Vitale P., Capriati V., Perna F. M., Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 1799–1802; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1813–1816; [Google Scholar]

- 4g. Elorriaga D., Rodríguez-Álvarez M. J., Ríos-Lombardía N., Morís F., Presa Soto A., González-Sabín J., Hevia E., García-Álvarez J., Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 8932–8935; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4h. Dilauro G., Azzollini C. S., Vitale P., Salomone A., Perna F. M., Capriati V., Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 10726–10730; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 10632–10636; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4i. Elorriaga D., Parra-Cadenas B., Antiñolo A., Carrillo-Hermosilla F., García-Álvarez J., Green Chem. 2022, 24, 800–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.See for example:

- 5a. Cicco L., Rodríguez-Álvarez M. J., Perna F. M., García-Álvarez J., Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3069–3077; [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Rodríguez-Álvarez M. J., García-Álvarez J., Uzelac M., Fairley M., O'Hara C. T., Hevia E., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 1720–1725; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Sánchez-Condado A., Carriedo G. A., Presa Soto A., Rodríguez-Álvarez M. J., García-Álvarez J., Hevia E., ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 3134–3143; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Ghinato S., Dilauro G., Perna F. M., Capriati V., Blangetti M., Prandi C., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 7741–7744; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5e. Cicco L., Salomone A., Vitale P., Ríos-Lombardía N., González-Sabín J., García-Álvarez J., Perna F. M., Capriati V., ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 3583–3588; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5f. Cicco L., Fombona-Pascual A., Sánchez-Condado A., Carriedo G. A., Perna F. M., Capriati V., Presa Soto A., García-Álvarez J., ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4967–4973; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5g. Quivelli A. F., D'Addato G., Vitale P., García-Álvarez J., Perna F. M., Capriati V., Tetrahedron 2021, 81, 131898; [Google Scholar]

- 5h. Ghinato S., Territo D., Maranzana A., Capriati V., Blangetti M., Prandi C., Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 2868–2874; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5i. Ramos-Martín M., Lecuna R., Cicco L., Vitale P., Capriati V., Ríos-Lombardía N., González-Sabín J., Presa-Soto A., García-Álvarez J., Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 13534–13537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anastas P. T., Warner J. C. in Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, Oxford, University Press, New York, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinxterhuis E. B., Giannerini M., Hornillos V., Feringa B. L., Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elorriaga D., de la Cruz F., Rodríguez-Álvarez M. J., Lara-Sánchez A., Castro-Osma J. A., García-Álvarez J., ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 2084–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. de Vries J. G., Important Pharmaceuticals and Intermediates, in Quaternary Stereocenters: Challenges and Solutions for Organic Synthesis (Eds. Christoffers J., Baro A.), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005, pp. 25–50; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Nicolaou K. C., Montagnon T. in Molecules that Changed the World, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2008; [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Gooßen L. J., Rudolphi F., Oppel C., Rodríguez N., Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 7211–7214; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3043–3045; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9d. Rajitha C., Dubey P. K., Sunku V., Piedrafita F. J., Veeramaneni V. R., Pal M., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 4887–4896; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9e. Lutter F. H., Grokenberger L., Hofmayer M. S., Knochel P., Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 8241–8245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For a complete perspective on this field, see the following background studies on the synthesis of lithium ketimides under Schlenk-type conditions:

- 10a. Clegg W., Snaith R., Shearer H. M. M., Wade K., Whitehead G., J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1983, 1309–1317; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Reed D., Barr D., Mulvey R. E., Snaith R., J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1986, 557–564; [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Clegg W., Snaith R., Wade K., Inorg. Chem. 1988, 27, 3861–3862; [Google Scholar]

- 10d. Barr D., Clegg W., Mulvey R. E., Snaith R., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1989, 57–58; [Google Scholar]

- 10e. Gregory K., Schleyer P. v. R., Snaith R., Adv. Inorg. Chem. 1991, 37, 47–142. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Recently, Prandi, Capriati et al. have reported the synthesis of ketones by the addition of organolithium reagents into aromatic amides, see Ref. [5h].

- 12.Regarding the possible competing processes in the addition of RLi reagents to nitriles, it is important to mention that, in conventional organic solvents and under Schlenk-type conditions, lithium imides with C−H groups attached to the C=N carbon atoms can rearrange to a η 3-aza-allyl complex: Andrews P. C., Armstrong D. R., McGregor M., Mulvey R. E., Reed D., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1989, 1341–1342. [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Peterson D. J., J. Org. Chem. 1968, 33, 780–784; [Google Scholar]

- 13b. van Staden L. F., Gravestock D., Ager D. J., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002, 31, 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.This lack of reactivity is consistent with our previous studies in the addition of Grignard reagents to transiently formed ketones in other one-pot tandem protocols in water (see References [5a] and [5i]).

- 15.Lithium magnesiates exhibit greater nucleophilic reactivities than neutral magnesium reagents:

- 15a. Mulvey R. E., Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 6676–6693; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15b. Harrison-Marchand A., Mongin F., Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 7470–7562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krasovskiy A., Knochel P., Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 3396–3399; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 3333–3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Watson S. C., Eastham J. F., J. Organomet. Chem. 1967, 9, 165–168; [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Lin H.-S., Paquette L. A., Synth. Commun. 2007, 24, 2503–2506. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krasovskiy A., Knochel P., Synthesis 2006, 5, 890–891. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.