Abstract

Acalabrutinib is a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor approved to treat adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic lymphoma, or previously treated mantle cell lymphoma. As the bioavailability of the acalabrutinib capsule (AC) depends on gastric pH for solubility and is impaired by acid‐suppressing therapies, coadministration with proton‐pump inhibitors (PPIs) is not recommended. Three studies in healthy subjects (N = 30, N = 66, N = 20) evaluated the pharmacokinetics (PKs), pharmacodynamics (PDs), safety, and tolerability of acalabrutinib maleate tablet (AT) formulated with pH‐independent release. Subjects were administered AT or AC (orally, fasted state), AT in a fed state, or AT in the presence of a PPI, and AT or AC via nasogastric (NG) route. Acalabrutinib exposures (geometric mean [% coefficient of variation, CV]) were comparable for AT versus AC (AUCinf 567.8 ng h/mL [36.9] vs 572.2 ng h/mL [38.2], Cmax 537.2 ng/mL [42.6] vs 535.7 ng/mL [58.4], respectively); similar results were observed for acalabrutinib's active metabolite (ACP‐5862) and for AT‐NG versus AC‐NG. The geometric mean Cmax for acalabrutinib was lower when AT was administered in the fed versus the fasted state (Cmax 255.6 ng/mL [%CV, 46.5] vs 504.9 ng/mL [49.9]); AUCs were similar. For AT + PPI, geometric mean Cmax was lower (371.9 ng/mL [%CV, 81.4] vs 504.9 ng/mL [49.9]) and AUCinf was higher (AUCinf 694.1 ng h/mL [39.7] vs 559.5 ng h/mL [34.6]) than AT alone. AT and AC were similar in BTK occupancy. Most adverse events were mild with no new safety concerns. Acalabrutinib formulations were comparable and AT could be coadministered with PPIs, food, or via NG tube without affecting the PKs or PDs.

Keywords: acalabrutinib capsule, acalabrutinib tablet, bioequivalence, food effect, proton‐pump inhibitor, relative bioavailability

Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) is an essential regulator of many aspects of normal B‐cell development, including differentiation, proliferation, maturation, cell migration, and cell death. 1 , 2 BTK loss does not result in a significant phenotype that impairs survival in mouse models. 3 BTK does influence B cells via multiple signaling nodes, 4 therefore BTK inhibition has been investigated as a potential therapy for B‐cell malignancies with great success. 1 Acalabrutinib is a next‐generation BTK inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of adult patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) that has been treated with at least one prior therapy. Acalabrutinib is also approved in the European Union in the treatment of adult patients with CLL. Acalabrutinib is a more selective, potent covalent BTK inhibitor with minimal off‐target effects on tyrosine‐protein kinase, epidermal growth factor receptor, and interleukin‐2‐inducible T‐cell kinase signaling. 2 , 5 The metabolism of acalabrutinib, via the action of cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A), leads to the generation of the major active metabolite ACP‐5862. 6 , 7 The mean exposure of ACP‐5862 is 2‐ to 3‐fold higher than acalabrutinib with 50% less potency with respect to BTK inhibition. 6 , 8 The activity of acalabrutinib is therefore based on contributions from both acalabrutinib and the active metabolite ACP‐5862.

Acalabrutinib exhibits linear pharmacokinetics (PKs) across a dose range of 75–250 mg (0.75–2.5 times the approved recommended single dose) and exhibits dose‐proportionality. 9 Dose‐ and schedule‐dependent inhibition of BTK‐receptor occupancy at steady‐state trough levels supports administration of acalabrutinib at a dose of 100 mg twice daily (BID). 10

Acalabrutinib is a Biopharmaceutical Classification System class II drug (high permeability, low solubility) that displays reduced solubility at higher pH. 11 By covalently inhibiting the gastric parietal cell proton pump (H+/K+‐adenosine triphosphatase), proton‐pump inhibitors (PPIs) regulate gastric acid secretion and increase gastric pH. 12 , 13 Consistent with the physiochemical properties of the acalabrutinib capsule (AC), coadministration with 40 mg omeprazole for 5 days led to a 43% decrease in the area under the curve (AUC) for AC and a 72% reduction in maximum concentration (Cmax) relative to subjects treated with AC alone (AstraZeneca, South San Francisco, CA, unpublished data on file). Because PPIs can exhibit a prolonged pharmacodynamic (PD) effect (lasting >24 hours after administration), 14 , 15 coadministration of AC with PPIs is not recommended.

Similarly, histamine‐H2 receptor antagonists, which inhibit stomach acid production, 16 increase the pH within the stomach and reduce the bioavailability of AC. Coadministration of histamine‐H2 receptors with acalabrutinib requires staggered dosing to separate the medications.

To overcome issues with bioavailability of AC (free base) when coadministered with PPIs, the maleate salt of acalabrutinib was formulated as a tablet that showed pH‐independent release. The 100‐mg acalabrutinib tablet (AT) is, therefore, predicted to mitigate the impact of a PPI on the PK and therefore the bioavailability of acalabrutinib. Additionally, many patients are unable to swallow or have difficulty swallowing capsules and require alternative methods to deliver acalabrutinib. Therefore, a suspension of AT in water was assessed via a nasogastric (NG) or oral route delivery to enable the use of acalabrutinib in patients who are unable to swallow capsules (or tablets), regardless of cotreatment with PPIs.

Herein, we report on ELEVATE‐PLUS, 17 a series of three phase 1, open‐label, single‐dose, randomized, crossover studies in healthy volunteers to evaluate the relative bioavailability (ie, establish bioequivalence [BE]), PPI (rabeprazole) effect, food effect of AT (administered orally or as a suspension via NG tube), PD analysis of target occupancy, and assessment of safety data.

Methods

The study protocols were approved by institutional review boards (IRBs) as follows: for NCT04768985 (PAREXEL Early Phase Clinical Unit, Baltimore, Maryland), IRBs were Aspire IRB, Santee, California, and wcgIRB, Puyallup, Washington, and study sites were located in Glendale, California, Brooklyn, Maryland, and Salt Lake City, Utah; for NCT04488016 (PAREXEL Early Phase Clinical Unit), the IRB was wcgIRB; and for NCT04564040 (Parexel International GmbH, Berlin, Germany), the IRB was Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales Berlin (State Office of Health and Social Affairs Berlin), Berlin, Germany.

All subjects (healthy and free of diagnosed cancer) provided written informed consent. These studies were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles originating in the Declaration of Helsinki and are consistent with the International Conference on Harmonisation/Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. The studies are registered with ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04768985 (other study no. D8223C00013), NCT04488016 (other study nos. D8220C00018, ACE‐HV‐115), and NCT04564040 (other study no. D8223C00005).

Subjects

Healthy male and female subjects between 18 and 55 years of age were included in these studies. Key inclusion criteria included suitable veins for cannulation or repeated venipuncture, a body mass index (BMI) of 18.5–30 kg/m2, weight between 50 and 100 kg at screening, understanding of study procedures and ability to comply with the protocol, willingness and ability to swallow all study drugs, and willingness and ability to consume a standardized FDA‐recommended high‐calorie, high‐fat breakfast, if applicable.

Key exclusion criteria included the presence of gastrointestinal, hepatic, or renal disease as judged by the investigator, or any condition known to interfere with the absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion of drugs, evidence of ongoing systemic infection, known contraindications to the use of capsules/tablets, prior treatment with acalabrutinib, a clinically significant illness, medical or surgical procedure, or trauma within 30 days of the first dose of the study drug, any prior treatment with another new chemical entity within 90 days of the first dose of the study drug, use of St. John's wort or other CYP3A‐inducing compounds within 3 weeks of the first dose of the study drug, or use of any prescribed or nonprescribed medication within 2 weeks of the first dose of the study drug.

Study Design

Subject randomization was assigned sequentially as subjects became eligible to participate in the study and was performed prior to the first day of dosing.

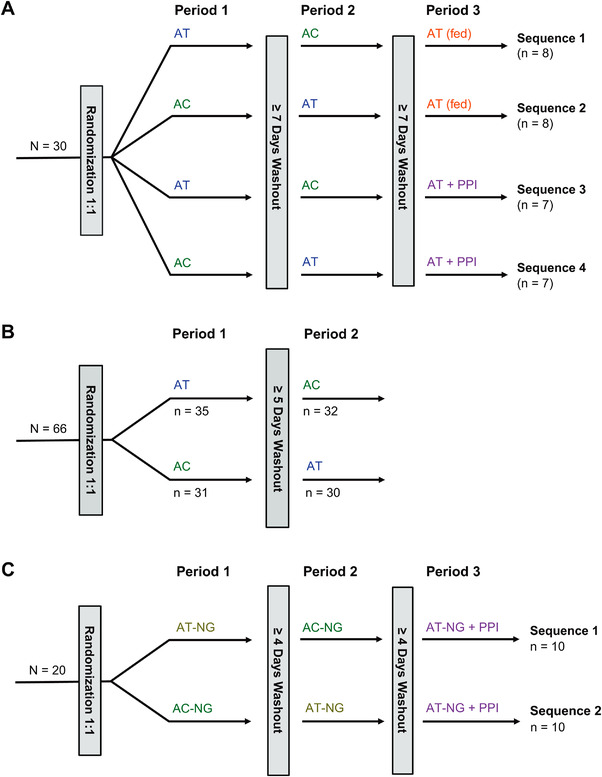

In the relative bioavailability study (study 1; NCT04488016), each subject was randomized to receive one of four treatment sequences (Figure 1A). Subjects were randomized to receive either 100 mg AT followed by 100 mg AC or 100 mg AC followed by 100 mg AT during periods 1 and 2; both treatments were administered in a fasted (>10 hours) state. In treatment period 3, subjects received either 100 mg AT in a fed state (sequence 1 or 2) or AT plus a PPI (20 mg rabeprazole in a fasted state 2 hours before administration of AT; sequence 3 or 4). Subjects receiving AT plus PPI on day 1 had received prior administration of rabeprazole 20 mg BID with meals on days −3, −2, and −1. Subjects who received AT with food (ie, AT [fed]) consumed a high‐calorie, high‐fat meal (800–1000 calories; 50% of total caloric content, respectively, per FDA guidance recommendations for food‐effect bioavailability and fed BE studies), 30 minutes prior to administration of 100 mg AT. The high‐calorie, high‐fat meal consisted of two eggs fried in butter, two slices of bacon, one buttered English muffin, 112 g of hash‐browned potatoes, and ≈240 mL of whole milk.

Figure 1.

Study designs. (A) Study 1 design: to assess the effect of a PPI or food on the bioavailability of AT. (B) Study 2 design: to assess the bioequivalence between AC and AT. (C) Study 3 design: to assess the PK of AT suspension administered via NG tube in the presence or absence of a PPI. Treatments: AT, 100‐mg AT, fasted state; AC, 100‐mg AC, fasted state; AT (fed), 100‐mg AT, fed state; AT + PPI, 100‐mg AT + prior treatment with 20‐mg rabeprazole (PPI); AT‐NG, 100‐mg AT suspension in water administered via NG tube; AC‐NG, 100‐mg AC in a Coca‐Cola + simethicone suspension administered via NG tube; AT‐NG + PPI, 100‐mg AT suspension in water administered via NG tube (AT‐NG) + prior treatment with 20‐mg rabeprazole tablet (PPI). AC, acalabrutinib capsule; AT, acalabrutinib maleate tablet; NG, nasogastric; PPI, proton‐pump inhibitor; PK, pharmacokinetics.

In the BE study (study 2; NCT04768985), subjects received the two different formulations of acalabrutinib, 100 mg AT or 100 mg AC, in a fasted state. Participants were randomly assigned to receive AT followed by AC or AC followed by AT, with ≥5 days between treatments (Figure 1B).

In a study to assess AT administered via NG tube in the presence of a PPI, study 3 (NCT04564040), subjects were randomly assigned to receive one of two acalabrutinib suspension treatment sequences: AT‐NG (100 mg AT suspension in water) followed by treatment AC‐NG (100‐mg AC suspension in a Coca‐Cola simethicone suspension; Coca‐Cola was used to facilitate solubility of the AC free base and simethicone was used to reduce foaming) or AC‐NG followed by AT‐NG; both treatments were administered through an NG tube with ≥4 days between treatments. After a second washout period, all participants then received AT‐NG in the presence of a PPI (AT‐NG + PPI). This treatment consisted of rabeprazole tablet (20 mg BID) with standard‐diet meals on days −3, −2, and −1 and a single dose on the morning of day 1 (fasted) at 2 hours prior to NG tube administration of 100‐mg AT suspension in water (Figure 1C).

The AT‐NG suspension was prepared by adding a 100‐mg AT to a bottle and then adding 15 mL of room‐temperature water, followed by agitation for 150 seconds until the tablet was fully disintegrated. The NG tube and enteral syringe were flushed with 15 mL of water before administration of the entire suspension directly to the enteral syringe from the bottle. The bottle was rinsed twice with further aliquots of 15 mL of water and these were added to the enteral syringe. Finally, the NG tube was flushed with 15 mL of water. The AT‐NG suspension was dosed within 60 minutes of adding the water to the tablet and was stored at room temperature.

To prepare the AC‐NG suspension, the 100‐mg AC was opened and the contents were transferred to a bottle, then 100 mL of degassed, room‐temperature Coca‐Cola was added to the bottle, followed by 3 drops of Infacol simethicone suspension (or equivalent to 0.15 mL of a 40 mg/mL aqueous simethicone suspension; only simethicone suspensions that do not contain weak carboxylic acids can be used). The bottle was agitated for 20 seconds. The NG tube and enteral syringe were flushed with 15 mL of water before administering the entire suspension directly to the enteral syringe from the bottle. The bottle was rinsed with 30 mL of water, the rinse was added to the enteral syringe, and the NG tube was flushed with 15 mL of water. The AC‐NG suspension was dosed within 3 hours of adding the Coca‐Cola to the capsule contents and was stored at room temperature.

Pharmacokinetic Assessments

Blood samples were collected on day 1 at predose and at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours postdose, on day 2 at 24 hours postdose (all studies), and on day 3 at 48 hours postdose (study 2 only). Plasma concentrations of acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 were determined using previously developed and validated methods based on liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. 18 The nominal ranges of quantitation were 1–1000 ng/mL for plasma acalabrutinib and 5–5000 ng/mL for plasma ACP‐5862.

PK parameters were computed using the linear up log down method for noncompartmental analysis, implemented in Phoenix WinNonlin (version 8.1, Certara, Princeton, New Jersey). For all three studies, PK assessment parameters for acalabrutinib were Cmax, area under the plasma concentration–time curve up to the last measurable concentration (AUClast), and area under the plasma concentration–time curve to infinite time (AUCinf). For all three studies, PK parameters of Cmax, AUClast, and AUCinf were also assessed for ACP‐5862. Additional PK parameters assessed for all three studies for both acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 were half‐life (t½) and time to reach maximum concentration (tmax). Apparent oral clearance (CL/F) was assessed for acalabrutinib (parent) only across all studies. Metabolite‐to‐parent compound ratios (M/P) for Cmax, AUClast, and AUCinf were also assessed.

Pharmacodynamics

BTK target occupancy (BTK‐TO) was measured for AT and AC, across all assessments, using a validated enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay in isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells, as previously described. 19 Whole‐blood samples were collected for the measurement of BTK‐TO in isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells on day 1 at predose and at 4 and 12 hours postdose (all studies), and on day 2 at 24 hours postdose (studies BE and NG only) during treatment periods 1, 2, and 3.

Safety Assessments

Safety and tolerability endpoints included assessment of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs, laboratory assessments (ie, hematology, clinical chemistry, coagulation, and urinalysis), physical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG), and vital signs (ie, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pulse rate, respiratory rate, and body temperature). AEs were classified by system organ class and preferred term using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 23.0 or later.

Statistical Analyses

Sample Size

For all the studies, the number of healthy subjects included was based on the need to ensure collection of adequate data while exposing as few subjects as possible to all study procedures.

For study 1 (NCT04488016), intended enrollment was 28 healthy subjects (7 per sequence group) to ensure that at least 24 evaluable subjects were available at the end of the study (at least 12 subjects each for assessing the effect of a PPI and food on the relative bioavailability), assuming a 20% dropout rate. Assuming a within‐subject coefficient of variation (CV) of 30% and an up to 50% decrease in acalabrutinib exposure with a PPI, the study would have >90% power to detect the predefined bounds of the 90% confidence interval (CI) of the AUC geometric mean ratio (GMR). Boundaries were based on data indicating that a <2‐fold change in acalabrutinib exposure neither alters the risk–benefit ratio of acalabrutinib nor requires dose adjustments. 20

For study 2 (NCT04768985), based on the established BE range of 80%–125% for Cmax and AUCinf for acalabrutinib, a within‐subject CV of 30%, and a true GMR of 0.95, 52 evaluable subjects were needed to achieve a power of 90%. Approximately 64 subjects (≈32 per treatment sequence, after accounting for dropouts) were randomly assigned to treatment in order to have at least 52 evaluable subjects (26 per sequence) at the end of study treatment.

For study 3 (NCT04564040), intended enrollment was 20 healthy subjects (10 per sequence group) to ensure that at least 16 evaluable subjects were available at the end of the study, assuming a 20% dropout rate. An evaluable sample size of 16 would have >80% power to compare the PK of 100 mg AT‐NG with that of 100 mg AC‐NG with a 90%CI for AUC GMR within 70%–143%, assuming that the true GMR was 0.95 and the within‐subject CV was 30%. Additionally, the study would provide >90% power to assess the effect of PPI on the PK of 100 mg AT‐NG, using bounds as described previously for study 1.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters

The PK analysis set consisted of all subjects in the safety analysis set who had at least one quantifiable postdose concentration and no protocol deviations or AEs that would impact analysis of the PK data set. Exposure of acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 following administration of acalabrutinib (AC or AT) in the presence and absence of a PPI, and in a fasted and fed state, is summarized.

Proton‐Pump Inhibitor Effect

To evaluate the effect of the PPI rabeprazole on the PK profiles of acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 after dosing with AT/AT‐NG, the PK parameters for acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 were compared between treatments with and without a PPI using a linear mixed‐effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) model.

Food Effect

To evaluate the effect of food (a high‐calorie, high‐fat meal) on the PK parameters for acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 after dosing with AT, the PK parameters for acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 were compared between the AT (fed) and AT (fasted) treatment, using the same ANOVA model.

Relative Bioavailability

To assess the relative bioavailability of AT/AT‐NG compared with AC/AC‐NG, both in a fasted state, the PK parameters of acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 were compared between the two treatments. The analysis was performed using a linear mixed‐effects ANOVA model using the natural logarithm of Cmax, AUCinf, and AUClast as response variables, sequence, period, and treatment as fixed effects, and subject nested within sequence as the random effect. Transformed back from the logarithmic scale, geometric means and geometric two‐sided 95%CIs for Cmax, AUCinf, and AUClast were estimated and are presented.

Pharmacodynamics

The PD analysis set consisted of all subjects in the safety analysis set and those who had at least one BTK‐TO value postdose (study 1) and all subjects in the PK analysis set (studies 2 and 3). The results of BTK‐TO were analyzed using an unpaired, two‐tailed t‐test to assess for statistically significant differences between treatments.

Safety

Safety data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The safety analysis set included all subjects who received any dose of study drug during treatment period 1 and for whom postdose safety data were available. The safety analysis set was used to present all demographic and disposition data, unless otherwise specified.

Results

Subject Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 30 subjects in study 1, 66 subjects in study 2, and 20 subjects in study 3 were enrolled and randomly assigned to a treatment sequence. Generally, the baseline characteristics were similar across studies (Table S1). In study 1, among the 30 subjects who were randomly assigned to one of four treatment sequences, 30 received treatment and 29 subjects completed the study (Figure 1A). In study 2, among the 66 subjects who were randomly assigned 1:1 to one of two treatment sequences of AT and AC, 65 subjects completed treatment with AT and 63 completed treatment with AC (Figure 1B). In study 3, a total of 20 subjects were randomly assigned 1:1 to a study treatment sequence and all subjects completed treatment (Figure 1C).

In study 1, the median age was 42 years (range 25–55 years) and most subjects were male (83.3%) and white (50.0%) or black (46.7%). There were no unusual observations for height, weight, or BMI and no noteworthy differences in baseline demographics were observed across treatment sequences. In study 2, the median age was 36 years (range 18–56 years). Most subjects were male (93.9%) and either white (50.0%) or black (43.9%). In study 3, the median age was 35 years (range 20–54 years) and only males participated, all of whom were white.

Pharmacokinetics

Bioequivalence: AT Versus AC

A summary and statistical comparison of the PK parameters between the AT and AC for acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 are presented in Table 1. In study 1 (NCT04488016), there was a <10% difference in Cmax and AUC for both acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 across both acalabrutinib formulations, with 90%CIs for GMRs falling nearly within the 80%–125% BE margin (Table 2). The arithmetic mean plasma concentration–time profiles for acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 following administration of AT or AC are presented in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 Exposure Following Administration With AT Versus AC, and the Tablet in the Presence or Absence of a PPI or Food

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter (unit) | Statistics | AC (n = 30) | AT (n = 29) | AT (fed) (n = 14) | AT + PPI (n = 14) | AT (n = 65) | AC (n = 63) | AC‐NG (n = 20) | AT‐NG (n = 20) | AT‐NG + PPI (n = 20) |

| Acalabrutinib | ||||||||||

| Cmax (ng/mL) | Arithmetic mean (SD) | 582.8 (227.6) | 559.8 (254.7) | 281.3 (139.6) | 459.6 (285.9) | 581.6 (231.0) | 606.8 (281.0) | 602.5 (259.2) | 609.0 (321.0) | 562.3 (316.8) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | Geometric mean (CV%) | 541.6 (41.1) | 504.9 (49.9) | 255.6 (46.5) | 371.9 (81.4) | 537.2 (42.6) | 535.7 (58.4) | 550.0 (46.7) | 547.3 (48.1) | 490.4 (58.9) |

| AUCinf (h ng/mL) | Arithmetic mean (SD) | 587.6 (150.5) | 591.2 (205.8) | 536.8 (97.9) | 742.0 (284.4) | 603.7 (215.6) | 610.6 (223.3) | 527.0 (135.7) | 602.7 (197.9) | 699.0 (227.3) |

| AUCinf (h ng/mL) | Geometric mean (CV%) | 569.9 (25.6) | 559.5 (34.6) | 528.7 (18.2) | 694.1 (39.7) | 567.8 (36.9) | 572.2 (38.2) | 511.2 (25.6) | 572.8 (33.9) | 664.8 (33.9) |

| AUClast (h ng/mL) | Arithmetic mean (SD) | 583.0 (147.1) | 587.9 (205.2) | 533.9 (98.1) | 718.9 (288.9) | 599.5 (213.6) | 605.8 (223.7) | 523.9 (135.4) | 600.0 (197.6) | 695.0 (226.8) |

| AUClast (h ng/mL) | Geometric mean (CV%) | 565.7 (25.4) | 556.2 (34.7) | 525.7 (18.3) | 669.7 (40.5) | 563.9 (36.9) | 566.8 (38.6) | 508.1 (25.6) | 570.0 (34.0) | 660.7 (34.0) |

| tmax (h) | Median (range) | 0.8 (0.5–2.0) | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | 2.0 (0.3–4.0) | 1.0 (0.2–3.0) | 0.5 (0.2–3.0) | 0.6 (0.5–4.0) | 0.3 (0.2–0.8) | 0.5 (0.2–0.8) | 0.5 (0.3–1.0) |

| t1/2λ (h) | Mean (SD) | 2.0 (2.0) | 1.5 (0.63) | 1.3 (0.40) | 2.9 (2.3) | 1.6 (1.2) | 2.2 (2.8) | 1.5 (0.7) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.9 (1.3) |

| ACP‐5862 | ||||||||||

| Cmax (ng/mL) | Arithmetic mean (SD) | 566.8 (195.2) | 580.1 (219.8) | 376.6 (127.2) | 410.9 (191.1) | 496.9 (148.6) | 495.2 (168.0) | 499.6 (112.1) | 493.3 (161.6) | 429.3 (146.1) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | Geometric mean (CV%) | 533.7 (37.2) | 538.5 (42.2) | 358.4 (33.2) | 365.3 (56.5) | 476.6 (29.8) | 459.9 (45.1) | 487.4 (23.4) | 471.9 (30.3) | 405.3 (37.2) |

| AUCinf (h ng/mL) | Arithmetic mean (SD) | 1668 (380.1) | 1720 (414.3) | 1666 (267.0) | 1850 (539.1) | 1546 (446.3) | 1520 (424.3) | 1610 (363.1) | 1619 (370.6) | 1642 (422.0) |

| AUCinf (h ng/mL) | Geometric mean (CV%) | 1625 (24.1) | 1672 (24.8) | 1644 (17.1) | 1783 (28.7) | 1488 (28.6) | 1460 (30.0) | 1574 (22.0) | 1579 (23.4) | 1594 (25.2) |

| AUClast (h ng/mL) | Arithmetic mean (SD) | 1576 (365.6) | 1623 (400.3) | 1553 (253.2) | 1722 (517.5) | 1454 (427.9) | 1435 (414.5) | 1533 (353.1) | 1548 (355.0) | 1560 (406.0) |

| AUClast (h ng/mL) | Geometric mean (CV%) | 1534 (24.6) | 1575 (25.9) | 1532 (17.4) | 1656 (29.6) | 1396 (29.4) | 1374 (31.6) | 1496 (22.8) | 1510 (23.4) | 1513 (25.6) |

| tmax (h) | Median (range) | 1.0 (0.3–3.0) | 0.8 (0.5–3.0) | 3.0 (1.0–4.0) | 1.8 (0.5–6.0) | 0.8 (0.5–4.0) | 1.0 (0.5–4.0) | 0.5 (0.5–2.0) | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) |

| t1/2λz (h) | Mean (SD) | 7.8 (1.6) | 8.2 (1.3) | 7.9 (1.4) | 7.8 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.7) | 7.0 (1.9) | 6.7 (1.1) | 6.4 (1.1) | 6.8 (0.8) |

| M/P‐AUCinf | Geometric mean (CV%) | 2.8 (21.1) | 2.9 (25.3) | 3.0 (17.9) | 2.5 (22.3) | 2.6 (26.6) | 2.5 (30.6) | 3.0 (19.7) | 2.7 (23.5) | 2.4 (22.7) |

| M/P‐Cmax | Geometric mean (CV%) | 1.0 (27.7) | 1.0 (32.1) | 1.4 (30.2) | 1.0 (37.9) | 0.9 (32.3) | 0.8 (43.0) | 0.9 (29.8) | 0.8 (28.7) | 0.8 (28.0) |

AC, acalabrutinib capsule (100 mg); AT, acalabrutinib maleate tablet (100 mg); AUCinf, area under the plasma concentration–time curve to infinite time; AUClast, area under the plasma concentration–time curve up to the last measurable concentration; Cmax, maximum concentration; CL/F, apparent oral clearance; M/P, metabolite‐to‐parent ratio; NA, not available; NG, nasogastric; PPI, proton‐pump inhibitor; SD, standard deviation; tmax, median time to maximum concentration; t1/2, median elimination half‐life.

Table 2.

Comparative Bioavailability of Acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 Following Administration With AT, With or Without Food or in the Presence or Absence of a PPI (Study 1) AT Versus AC (study 2), and AT‐NG in the Presence or Absence of a PPI (Study 3)

| Clinical Trial | Treatment | Acalabrutinib AUClast N; GMR (90%CI) | Acalabrutinib AUCinf N; GMR (90%CI) | Acalabrutinib Cmax N; GMR (90%CI) | ACP‐5862 AUClast N; GMR (90%CI) | ACP‐5862 AUCinf N; GMR (90%CI) | ACP‐5862 Cmax N; GMR (90%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Test: AT fed | 14; 97.7 (87.2–109.5) | 14; 97.7 | 14; 46.0 (35.9–59.0) | 14; 100.1 (95.5–104.9) | 14; 101.7 | 14; 63.9 (54.2–75.5) |

| Ref: AT fasted | (87.2–109.5) | (96.9–106.7) | |||||

| Study 1 | Test: AT + PPI | 14; 113.9 (101.4–128.0) | 14; 117.4 | 14; 76.4 (54.9–106.3) | 14; 99.4 (90.8–108.8) | 14; 100.7 | 14; 69.8 (51.3–94.9) |

| Ref: AT | (105.4–130.8) | (93.3–108.8) | |||||

| Study 1 | Test: AT fasted Ref: AC fasted | 29; 98.1 (91.8–104.8) | 29; 97.9 (91.6–104.6) | 29; 91.0 (79.4–103.1) | 29; 103.3 (99.9–106.9) | 29; 103.6 (100.1–107.3) | 29; 99.8 (91.9–108.4) |

| Study 2 | Test: AT fasted | 63; 98.8 (93.6–104.2) | 63; 98.6 | 63; 100.4 (90.8–111.0) | 63; 101.8 (98.2–105.5) | 63; 101.5 | 63; 103.7 (95.7–112.3) |

| Ref: AC fasted | (93.4–104.0) | (98.2–105.0) | |||||

| NG study and study 2 a | Test: AT‐NG | 101.1 (87.1–117.4) | 100.9 | 101.9 (85.2–121.8) | 108.2 (96.2–121.6) | 106.2 | 99.0 (87.4–112.1) |

| Ref: AT fasted | (86.9–117.1) | (94.6–119.1) | |||||

| Study 3 | Test: AT‐NG + PPI | 16; 115.9 | 16; 116.1 | 16; 89.6 | 19; 100.2 | 19; 100.9 | 19; 85.9 |

| Ref: AT‐NG | (96.1–139.8) | (96.3–139.9) | (67.6–118.8) | (88.0–114.2) | (88.7–114.8) | (71.9–102.6) | |

| Study 3 | Test: AT‐NG | 20; 112.2 | 20; 112.0 | 20; 99.5 | 20; 100.9 | 20; 100.4 | 20; 96.8 |

| Ref: AC‐NG | (105.3–119.5) | (105.2–119.3) | (84.3–117.4) | (98.7–103.2) | (98.2–102.6) | (88.1–106.4) |

AC fasted: 100‐mg AC, fasted state; AT fasted: 100‐mg AT, fasted state; AT (fed): 100‐mg AT, fed state; AT + PPI: 100‐mg AT + 20‐mg rabeprazole (PPI); AT‐NG: 100‐mg AT suspension in water administered via NG tube; AT‐NG + PPI: 100‐mg AT suspension in water administered via NG tube + 20‐mg rabeprazole tablet pretreatment (PPI).

Statistical assessments of GMRs and two‐sided 90%CI estimation were performed using analysis of variance linear model ANOVA and the natural logarithm of AUCinf, Cmax, and AUClast as the response variables for acalabrutinib and its metabolite ACP‐5862, respectively.

AC, acalabrutinib capsule; ANOVA, analysis of variance linear model; AT, acalabrutinib maleate tablet; AUCinf, area under the plasma concentration–time curve to infinite time; AUClast, area under the plasma concentration–time curve up to the last measurable concentration; Cmax, maximum concentration; CI, confidence interval; GMR, geometric mean ratio; PK, pharmacokinetics; PPI, proton‐pump inhibitor.

The reference AT‐fasted PK parameters are from study 2 and the test AT‐NG PK parameter data are from study 3.

Figure 2.

Plasma concentrations of (A) acalabrutinib and (B) its major pharmacologically active metabolite, ACP‐5862, in the three studies. Data are presented as arithmetic means. Plots are truncated to show data up to 12 hours due to the limited additional information provided by the 24‐hour concentration measurement, especially for acalabrutinib with a half‐life of ≈2–3 hours (with the majority of samples being below the limit of quantification). AT, AT, including treatment A in study 2; AC, AC, including treatment B in study 2; AT + PPI, AT + PPI (rabeprazole), including treatment D in study 1; AT (fed), acalabrutinib tablet, fed state, including treatment C in study 1; AT‐NG, acalabrutinib tablet with nasogastric tube administration, including treatment A in study 3; AC, acalabrutinib capsule; AT, acalabrutinib maleate tablet; NG, nasogastric; PPI, proton‐pump inhibitor.

The results of study 2 were consistent with those of study 1. The geometric mean PK exposures (Cmax and AUCs) of acalabrutinib were nearly identical between the two formulations (AT versus AC), with a Cmax of 537.2 versus 535.7 ng/mL, respectively, and an AUCinf of 567.8 versus 572.2 ng h/mL, respectively (Table 1; study 2). Accordingly, the systemic exposures between AT and AC had GMRs of 98.6% for AUCinf and 100.4% for Cmax for acalabrutinib (Table 2). Moreover, all 90%CIs for GMRs were within the 80%–125% BE margin (Table 2). Similar results were observed for the metabolite ACP‐5862: a <5% difference in Cmax and AUC across both formulations, with all 90%CIs for GMRs falling within the 80%–125% BE margin (Table 2). The tmax for acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 was similar following administration of both AT and AC (Table 1). The M/P ratios (ie, M/P‐Cmax and M/P‐AUCinf) were also comparable between AT and AC (Table 1).

The Effect of Proton‐Pump Inhibitors

The arithmetic mean plasma concentration–time profiles for acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 following administration of AT in the presence or absence of the PPI, rabeprazole, are shown in Figure 2. A summary and statistical comparison between the PK parameters for AT in the presence or absence of a PPI for both acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 are presented in Table 1.

Following oral administration of AT with a PPI (study 1), the geometric mean acalabrutinib Cmax was lower (≈24%) with a slightly higher AUC (≈14%) than it was after administration of AT alone. Similar results were observed for ACP‐5862: a slight decrease in Cmax (≈30%) and no effect on AUC (Tables 1 and 2). Likewise, following coadministration of PPI and AT‐NG (study 3), the acalabrutinib geometric mean Cmax was lower (≈10%) with a slightly higher AUC (≈16%) than it was after administration of AT alone. Similar results were observed for ACP‐5862 with a slight decrease in Cmax (≈14%) and no effect on AUC (Tables 1 and 2).

The median acalabrutinib tmax value following oral administration of AT in the presence of a PPI was slightly greater than in the absence of the PPI. Comparable results for tmax were also observed for ACP‐5862 following administration of AT in the absence or presence of a PPI (Table 1; study 1). The M/P ratios (ie, M/P‐Cmax and M/P‐AUCinf) were comparable between AT in the absence or presence of a PPI (Table 1).

The Effect of Food

The arithmetic mean plasma concentration–time profiles for acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 following administration of AT in the presence or absence of food (high‐fat diet) are presented in Figure 2. A summary and statistical comparison between the PK parameters for AT in the presence or absence of food for both acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 are presented in Table 1.

The geometric mean Cmax for acalabrutinib following administration of AT was lower (≈54%), in a fed state versus a fasted state, while geometric mean AUCs for acalabrutinib were comparable (Tables 1 and 2). Similar results were also observed for ACP‐5862 (ie, Cmax was 36% lower and AUC was comparable in both the fed and fasted states; Tables 1 and 2).

The tmax for acalabrutinib was shorter following administration of AT in a fasted state compared to a fed state (median [range] 0.7 hours [0.3–1.5 hours] vs 2.0 hours [0.3–4.0 hours]; Table 1). Similar changes in tmax were observed for ACP‐5862, thus the M/P ratios (ie, M/P‐Cmax and M/P‐AUC) were comparable for AT in the fed versus fasted states (Table 1).

AT‐NG Versus AT

The systemic exposures (Cmax and AUC) of acalabrutinib were similar when AT was administered as a suspension via NG tube (AT‐NG; study 3, NCT04564040), compared to oral administration of AT (fasted state; study 2 [NCT04768985]); there was a 1.9% difference in geometric mean exposures with the 90%CI contained entirely within the predefined range of 80%–125% BE margin. Similar results were observed for ACP‐5862, with similar Cmax (≈10% difference) and AUC (≈16% difference) across the AT‐NG and AT oral formulation (Table 2).

Additionally, in study 3 (NCT04564040), the relative bioavailability was similar following AT‐NG versus AC‐NG. The GMRs for Cmax and AUCs were ≈100% and 112% for acalabrutinib and ≈97% and 100% for ACP‐5862, respectively; the corresponding 90%CIs were within the 80%–125% BE margin (Table 2).

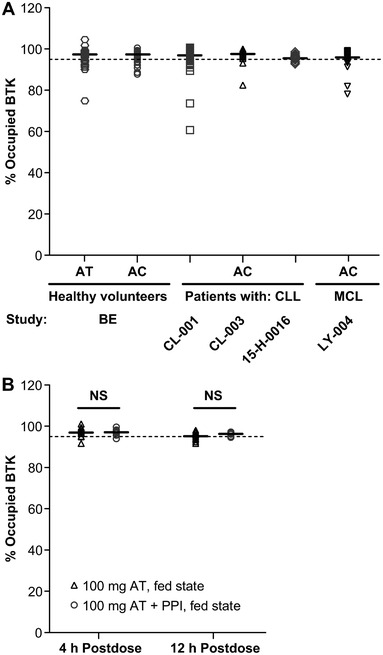

Pharmacodynamics

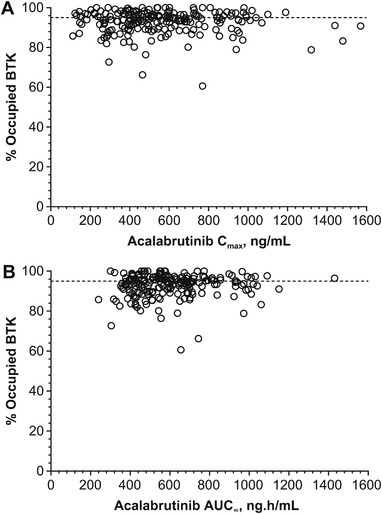

The BTK‐TO was comparable across the two formulations (AT vs AC), with median values >95% occupancy (Figure 3A). There were no differences in BTK‐TO following administration of AT with or without a PPI or food; the median BTK‐TO values were >96% across treatments at 4 hours postdose (range of arithmetic means 96.1%–96.4%) and >88% across treatments at 12 hours postdose (range 88.1%–89.8%; Figure 3B). PD analysis of BTK receptor occupancy versus Cmax and AUC following administration of acalabrutinib demonstrated that BTK‐TO is unaffected by lower Cmax (Figure 4A, B). Overall, BTK occupancy following administration of AT in healthy subjects was comparable to that observed for 100 mg AC administered BID in subjects with CLL or MCL.

Figure 3.

(A) Pharmacodynamics of BTK receptor occupancy following administration of acalabrutinib: comparison of AT to AC (across several studies). Shown horizontal error bar indicates median for each data set. Dotted line indicates 95% BTK‐TO. (B) Pharmacodynamics of BTK receptor occupancy following administration of acalabrutinib (fed state) in the absence or presence of a PPI (study 1). Dots represent patient samples; solid horizontal lines represent median values. Significance was determined using an unpaired, two‐tailed t‐test. AC, acalabrutinib capsule; AT, acalabrutinib maleate tablet; BTK, Bruton tyrosine kinase; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; NS, not significant; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Figure 4.

Pharmacodynamics of BTK receptor occupancy versus (A) Cmax and (B) AUC, following administration of acalabrutinib. Data pooled across all three studies are presented. Dotted line indicates 95% BTK‐TO. AUC, area under the curve; BTK, Bruton tyrosine kinase; Cmax, maximum concentration; TO, total occupancy.

Safety

Across all three studies that evaluated the PK of acalabrutinib formulations (ie, AT and AC when administered orally or as a suspension via an NG tube, in the absence or presence of a PPI or food), treatment regimens were well tolerated, with no new safety concerns observed. Overall, 30% of subjects in study 1, 17% in study 2, and 40% in study 3 experienced at least one AE.

In study 1, the only AE reported in more than one subject was headache (n = 2, 6.9% in the AT treatment group; Table S2). In study 2, comparing acalabrutinib formulations, 15.4% (10/65) and 4.8% (3/63) of participants in the AT and AC treatment groups, respectively, experienced an AE (both 100 mg, fasted state; Table S2). All AEs were grade 1, with the exception of one grade 2 AE of dizziness following administration of AT. The most frequently reported AE (n = 5) was headache (AT, 5/65 [7.7%] subjects; AC, 0/63). Likewise, in study 3, most AEs were experienced by only one subject each, with the exception of fatigue (n = 3, 15%) and oropharyngeal pain (n = 2, 10%) both in treatment group AT‐NG (100 mg AT suspension in water administered via NG tube; Table S2). All AEs in study 3 were grade 1.

No serious AEs occurred, and there were no AEs that resulted in death. Two subjects discontinued study drug due to an AE; both were in study 1 and experienced the AE after treatment with AT (moderate rash pruritic, n = 1 in sequence 1; mild alanine aminotransferase increased, n = 1 in sequence 2).

The incidence of AEs in terms of relatedness and intensity between treatments was similar. All AEs reported across these three studies were of mild intensity, with a few exceptions (moderate‐intensity AEs included dizziness [n = 1] with AT treatment in study 2, headache [n = 2] with AT treatment in study 1, and rash pruritic [n = 1] with AC treatment in study 1). Almost all AEs resolved without intervention by the end of the studies (with one exception: AE of fever in study 3).

Discussion

These studies conducted in healthy human subjects demonstrate that the PK, PD, safety, and tolerability of 100 mg AT yielded similar results to that of 100 mg AC, within the limited dosing duration. Although the studies have some limitations related to the numbers of subjects for safety data analysis and the inability to make some statistical comparisons, descriptive comparisons can be made. The results suggest the lack of a clinically relevant impact of a PPI or food on the exposure of acalabrutinib and its active metabolite (ACP‐5862) following administration of AT with or without a PPI and in a fed or fasted state.

The PK, safety, and tolerability of AT were assessed in comparison with AC in two studies, study 1 and study 2. Following the positive results from study 1 (<10% difference in systemic exposures), the formally powered study 2 was conducted to establish the BE between 100 mg AT and 100 mg AC. In study 2, the geometric mean PK exposures (Cmax and AUClast or AUCinf) of acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 were similar (<4% difference) following administration of AT and AC, with the 90%CIs for GMRs contained within the BE bounds of 80% and 125%. The results of the BE analysis were further supported by the PD assessment, which showed that the BTK‐TOs at 4 and 12 hours postdose were comparable (with median BTK‐TO approximately of ≥95%) between the two formulations.

The new AT was formulated with a pH‐independent release, compared with the previous capsule formulation (ie, AC), and was predicted to limit or eliminate the impact of PPIs on acalabrutinib bioavailability. In study 1, the effect of a PPI was evaluated by comparing the PK of acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 following a single oral 100‐mg dose of AT, administered with and without 20 mg rabeprazole. Rabeprazole was selected as the PPI based on its rapid onset of action, thereby allowing for a shorter time needed to achieve maximum suppression of gastric pH (eg, 3 days for rabeprazole vs 5 days for omeprazole). 21 Furthermore, rabeprazole is metabolized mainly via a nonenzymatic pathway, and CYP P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) and CYP3A4 are only partly involved in its metabolism. Therefore, the inhibitory effect on gastric acid secretion of rabeprazole is less influenced by the CYP2C19 phenotype or genotype status, unlike other commonly used PPIs such as omeprazole. Finally, the use of rabeprazole is consistent with current FDA guidance on the criteria for selecting a PPI for the evaluation of pH‐dependent interactions. Overall, rabeprazole, administered as a BID regimen, was expected to provide a consistent suppression of acidity and a rapid onset, and was considered appropriate for the current study.

A slight increase in acalabrutinib AUC (≈14% to 17% difference in geometric means) was noted following coadministration of rabeprazole with AT. This may potentially be attributed to the following factors: (1) PPIs (including rabeprazole and omeprazole) have been reported to result in increased gastric retention (reflected by the slight increase in acalabrutinib tmax), while keeping a relatively fast emptying rate. This may increase the transit time of acalabrutinib in the absorption window, leading to greater absorption as compared to acalabrutinib administered without PPI. This is different from the acalabrutinib absorption kinetics observed following coadministration with a high‐fat diet, wherein the increased gastric retention is accompanied by a slower gastric emptying (reflected by the greater increase in acalabrutinib tmax), 22 which may lead to increased first‐pass metabolism thereby negating any increase in AUC. (2) Rabeprazole has been reported to be a weak inhibitor of CYP3A in vitro (similar to omeprazole), while acalabrutinib is predominantly metabolized by CYP3A. The rabeprazole‐mediated CYP3A‐inhibitory effect is not clinically relevant, but it may explain the slightly higher AUC noted for acalabrutinib in the current study. Given that acalabrutinib has a wide therapeutic window, with doses as high as 400 mg daily being tested in the phase 1 study, an increase in exposure of up to 2‐fold can be expected to be safe and well tolerated. 20 Consequently, any potential increase in acalabrutinib exposures following coadministration with PPIs is not considered clinically relevant.

Overall, based on the PK variability (>29% for Cmax and >17% for AUC), similar BTK‐TO across treatment arms, and a wide therapeutic window, the decrease in the rate of exposure (≈24% decrease in Cmax), with minimal to no change in the extent of exposure (up to ≈17% increase in AUC), is not considered clinically significant. Thus, it is proposed that AT can be taken regardless of acid‐reducing agents.

The current commercial AC can be given with food or on an empty stomach. In healthy subjects, administration of a 75‐mg dose of AC with a high‐fat, high‐calorie meal (918 calories, 59 g of carbohydrate, 59 g of fat, and 39 g of protein) did not affect the AUC compared to dosing under fasted conditions (AstraZeneca, South San Francisco, California; unpublished data on file). However, the Cmax was decreased by 73% and the tmax was delayed 1–2 hours (AstraZeneca, South San Francisco, California; unpublished data on file). Consistent with these observations for the commercial AC formulation, the Cmax was also lower for both acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 in the fed state compared with the fasted state (47.5% and 40.4% decrease, respectively); and the AUCinf values for acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 for AT were similar in the fed and fasted states. There were no differences in BTK‐TO following administration of AT with or without food (study 1). Both acalabrutinib and its active metabolite, ACP‐5862, bind covalently to BTK. Once covalently bound by acalabrutinib or ACP‐5862, an individual BTK protein is permanently inactivated, and the return of functional activity requires new BTK protein synthesis. Therefore, BTK occupancy is more likely to be dependent on maintaining acalabrutinib/ACP‐5862 exposures (as represented by AUC or minimum plasma concentration) above a threshold (eg, half‐maximal inhibitory concentration [IC50]) rather than on the highest exposures (ie, Cmax) achieved during a dosing interval. This rationale is supported by the similarity in BTK occupancy observed across the treatment arms, which showed a decrease in Cmax (in the presence of food or a PPI) with no change in AUC. Thus, the new tablet formulation of acalabrutinib, AT, may have greater flexibility relative to being taken with or without food.

To support the clinical evaluation of acalabrutinib in patients who require NG delivery, as well as coadministration with PPIs, study 3 was conducted. The results demonstrate that the PK and PD of acalabrutinib and ACP‐5862 were similar following NG administration of AT suspension in water, in the presence or absence of a PPI, versus administration of the AC suspension in flat (degassed) Coca‐Cola (ie, AC‐NG). It was shown that the PK and BTK‐TO following AC‐NG, in the presence or absence of a PPI, were comparable to PK and BTK‐TO of 100 mg AC administered orally (data to be published separately). Therefore, the results of the current study support switching subjects receiving AC‐NG (or AC) to AT‐NG, regardless of concomitant PPI use.

Most AEs reported in this study were mild and resolved without treatment. In study 2 and 3, all AEs were grade 1, with the exception of one grade 2 AE of dizziness following administration of AT in study 2. In study 1, AEs were mild in intensity, with the exception of two (6.9%) subjects with an AE of headache in the AT group and one (3.3%) subject with an AE of rash pruritic in the AC group; both of these AEs were moderate in intensity. While fewer headaches occurred with oral administration of AT in the presence of food or a PPI compared to with AT alone (in study 1, there were two headaches in the AT group and no headaches in the AC, AT‐fed, or AT + PPI groups), fewer subjects were examined for the administration of AT in a fed state or with a PPI (14 subjects in each group vs 29 subjects in the AT fasted group). While coadministration of a PPI reduced Cmax, headache numbers for AT‐NG did not differ based on the absence or presence of a PPI (in each group, one subject [5.0%] reported headache). No safety or tolerability concerns were observed using a dose of 100 mg of AT (either orally or as suspension administered via NG tube) and study drug discontinuations due to AEs were rare (n = 2/116 participants across all studies).

Limitations of these studies include the small number of healthy subjects analyzed after single‐dose administration for safety, as well as the relatively young age of the volunteers (aged 18–55 years) compared with the typically older age of patients impacted by CLL, for example the median age of CLL diagnosis is 72 years. 23 In addition, the studies enrolled a greater proportion of subjects who were black (relative to the typical North American population demographics) and men. However, age, sex, and race (Caucasian vs African American) do not impact the PK of acalabrutinib or ACP‐5862, 24 therefore the PK results can be generalized across the population.

Finally, in the current studies, BTK occupancy was measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from healthy volunteers, which are not the target tissue or population. We previously reported near‐complete BTK occupancy in lymph nodes, bone marrow, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with hematological malignancies with AC 100 mg BID dosing. 10 Acalabrutinib maleate dissociates rapidly during the fast dissolution of AT and releases acalabrutinib free base. Therefore, the same active moiety (acalabrutinib free base) is absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract for both products (AC and AT) and is subsequently available systemically to exert its pharmacological activity. Given the similar PK between the two formulations (AC vs AT) and between healthy subjects and patients with hematological malignancies, 24 the acalabrutinib PK‐driven BTK occupancy observed in the current studies can be extrapolated to the target tissue and indicated population(s).

Conclusions

The existing formulation of 100 mg AC is approved for the treatment of patients with CLL, SLL, and MCL who have been treated with at least one prior therapy. However, based on its pH‐dependent solubility, the current AC label includes the recommendation that patients avoid coadministration with PPIs and that dosing should be staggered with H2‐receptor antagonists and antacids. Patients often require PPIs for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux or peptic ulcer disease, thus limiting the use of AC as a treatment option.

The efficacy of 100 mg AC is well established based on previously conducted clinical studies in the approved indications. Based on the BE between the 100 mg AT and 100 mg AC formulations and their comparable BTK receptor occupancy, it is anticipated that 100 mg AT (regardless of concomitant PPI use) will achieve the same efficacy as the approved 100 mg AC formulation.

Acalabrutinib has a well‐characterized safety and tolerability profile that has been observed following dosing with the AC formulation, as summarized based on a population of over 1000 patients with hematologic malignancies. 20 , 24 Based on their BE, lack of safety and tolerability concerns observed in the current studies, and the established exposure‐safety relationship, it can be anticipated that the safety profile for 100 mg AT will be the same as that of the approved 100‐mg AC formulation.

While the risk–benefit ratios of the approved and proposed acalabrutinib formulations are expected to be the same, the proposed AT formulation offers a greater benefit to the overall patient population: 100 mg AT has sufficient solubility across the physiologic pH range to overcome the label restrictions on PPI use and acid‐reducing agents, allowing a broader patient population to benefit from this product and supporting simplification of their medication regimen (ie, no staggering of dose is needed with H2‐receptor antagonists and antacids). Additionally, the film coating of AT facilitates easy swallowing and a 50% reduced volume compared with the AC formulation. Moreover, AT can be easily suspended in a small amount of water to allow for NG dosing in patients unable to swallow tablets.

In conclusion, the clinical benefit–risk profile for acalabrutinib is anticipated to be similar between the current commercial capsule formulation (ie, AC) and the new acalabrutinib maleate tablet (ie, AT). However, the 100‐mg AT formulation mitigates the effect of pH on acalabrutinib/ACP‐5862 systemic exposures, allowing a broader patient population to benefit from this product.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: SS, JM, LZ, JW, XP, MM. Data acquisition: SS, AdJ, HLM, LZ. Analysis and interpretation of data: SS, AdJ, LZ, JW, XP, DR, NKC. Writing review and/or revision of the manuscript: All authors reviewed all drafts of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Funding

This study was funded by AstraZeneca, Cambridge, England, UK.

Disclosures

Shringi Sharma, Xavier Pepin, Harini Burri, Nataliya Kuptsova‐Clarkson, Ting Yu, Michal Majewski, James Mann, Louise Sheridan, and Helen Tomkinson are employees of AstraZeneca and own stock in AstraZeneca. Lianqing Zheng, Holly L. MacArthur, and Veerendra Munugalavadla are employees of AstraZeneca and own stock in AstraZeneca and Gilead Sciences. Anouk de Jong is an employee of Acerta Pharma (a member of the AstraZeneca Group). John C Byrd serves as an advisor for AstraZeneca. Richard R. Furman serves on advisory boards for AstraZeneca. Joseph A. Ware was an employee of Acerta Pharma (a member of the AstraZeneca Group) at the time the study was conducted and owns stock in AstraZeneca and Vincerx Pharma. David Ramies was an employee of AstraZeneca.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all subjects for their participation, as well as the Parexel Early Phase Clinical Unit, Parexel International GmbH, Covance Laboratories, Inc., and the Covance Clinical Research Unit for their assistance. Medical writing and editorial support, conducted in accordance with Good Publication Practice 3 and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors guidelines, were provided by Tarah M. Connolly, PhD, of Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc., Newtown, PA, and funded by AstraZeneca, Gaithersburg, MD.

[Corrections added on 15 September 2022, after first online publication: Corrections to “Subject Demographics and Baseline Characteristics” have been applied in this version].

References

- 1. Wu J, Liu C, Tsui ST, Liu D. Second‐generation inhibitors of Bruton tyrosine kinase. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9(1):80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barf T, Covey T, Izumi R, et al. Acalabrutinib (ACP‐196): a covalent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor with a differentiated selectivity and in vivo potency profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;363(2):240‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nyhoff LE, Clark ES, Barron BL, Bonami RH, Khan WN, Kendall PL. Bruton's tyrosine kinase is not essential for B cell survival beyond early developmental stages. J Immunol. 2018;200(7):2352‐2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wen T, Wang J, Shi Y, Qian H, Liu P. Inhibitors targeting Bruton's tyrosine kinase in cancers: drug development advances. Leukemia. 2021;35(2):312‐332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Awan FT, Schuh A, Brown JR, et al. Acalabrutinib monotherapy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who are intolerant to ibrutinib. Blood Adv. 2019;3(9):1553‐1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou D, Podoll T, Xu Y, et al. Evaluation of the drug‐drug interaction potential of acalabrutinib and its active metabolite, ACP‐5862, using a physiologically‐based pharmacokinetic modeling approach. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2019;8(7):489‐499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Podoll T, Pearson PG, Evarts J, et al. Bioavailability, biotransformation, and excretion of the covalent bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor acalabrutinib in rats, dogs, and humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2019;47(2):145‐154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaptein A, Podoll T, de Bruin G, et al. Preclinical pharmacological profiling of ACP‐5862, the major metabolite of the covalent BTK inhibitor acalabrutinib, displays intrinsic BTK inhibitory activity Cancer Res. 2019;79:2194. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edlund H, Lee SK, Andrew MA, Slatter JG, Aksenov S, Al‐Huniti N. Population pharmacokinetics of the BTK inhibitor acalabrutinib and its active metabolite in healthy volunteers and patients with B‐cell malignancies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58(5):659‐672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sun C, Nierman P, Kendall EK, et al. Clinical and biological implications of target occupancy in CLL treated with the BTK inhibitor acalabrutinib. Blood. 2020;136(1):93‐105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pepin XJH, Sanderson NJ, Blanazs A, Grover S, Ingallinera TG, Mann JC. Bridging in vitro dissolution and in vivo exposure for acalabrutinib. Part I. Mechanistic modelling of drug product dissolution to derive a P‐PSD for PBPK model input. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2019;142:421‐434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pace F, Pallotta S, Casalini S, Porro GB. A review of rabeprazole in the treatment of acid‐related diseases. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(3):363‐379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morelli G, Chen H, Rossiter G, Rege B, Lu Y. An open‐label, parallel, multiple‐dose study comparing the pharmacokinetics and gastric acid suppression of rabeprazole extended‐release with esomeprazole 40 mg and rabeprazole delayed‐release 20 mg in healthy volunteers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(7):845‐854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robinson M. New‐generation proton pump inhibitors: overcoming the limitations of early‐generation agents. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13(suppl 1):S43‐S47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Segregur D, Flanagan T, Mann J, et al. Impact of acid‐reducing agents on gastrointestinal physiology and design of biorelevant dissolution tests to reflect these changes. J Pharm Sci. 2019;108(11):3461‐3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feldman M. Comparison of the effects of over‐the‐counter famotidine and calcium carbonate antacid on postprandial gastric acid. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;275(18):1428‐1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sharma S, Pepin X, Burri H, et al. New acalabrutinib formulation enables co‐administration with proton pump inhibitors and dosing in patients unable to swallow capsules (ELEVATE‐PLUS). Blood. 2021;138:4365. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu Y, Izumi R, Nguyen H, et al. Evaluation of the pharmacokinetics and safety of a single dose of acalabrutinib in subjects with hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;62(6):812‐822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alsadhan A, Cheung J, Gulrajani M, et al. Pharmacodynamic analysis of BTK inhibition in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with acalabrutinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(12):2800‐2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Edlund H, Buil‐Bruna N, Vishwanathan K, et al. Exposure‐response analysis of acalabrutinib and its active metabolite, ACP‐5862, in patients with B‐cell malignancies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(5):2284‐2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ohning GV, Walsh JH, Pisegna JR, Murthy A, Barth J, Kovacs TO. Rabeprazole is superior to omeprazole for the inhibition of peptone meal‐stimulated gastric acid secretion in Helicobacter pylori‐negative subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(9):1109‐1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weitschies W, Friedrich C, Wedemeyer RS, et al. Bioavailability of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid from extended release tablets depends on intragastric tablet deposition and gastric emptying. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;70(2):641‐648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2020 update on diagnosis, risk stratification and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(11):1266‐1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Edlund H, Bellanti F, Liu H, et al. Improved characterization of the pharmacokinetics of acalabrutinib and its pharmacologically active metabolite, ACP‐5862, in patients with B‐cell malignancies and in healthy subjects using a population pharmacokinetic approach. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(2):846‐852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information