Abstract

We aimed to estimate the impact of social isolation on cognitive function and mental health among older adults during the two-year-and-a-half COVID-19 period. Pubmed Central, Medline, CINAHL Plus and PsychINFO were searched between March 1, 2020, and September 30, 2022. We included all studies that assessed proportions of older adults with the mean or the median with a minimum age above 60 reporting worsening cognitive function and mental health. Thirty-two studies from 18 countries met the eligibility criteria for meta-analyses. We found that the proportions of older adults with dementia who experienced worsening cognitive impairment and exacerbation or new onset of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) were approximately twice larger than that of older adults with HC experiencing SCD and worsening mental health. Stage of dementia, care options, and severity of mobility restriction measures did not yield significant differences in the number of older adults with dementia reporting worsening cognitive impairment and BPSD, while the length of isolation did for BPSD but not cognitive impairment. Our study highlights the impact of social isolation on cognitive function and mental health among older adults. Public health strategies should prioritize efforts to promote healthy lifestyles and proactive assessments.

Keywords: Dementia, Cognitive impairment, Cognitive decline, Mental health, Older adults, COVID-19, Isolation

1. Introduction

Non-pharmaceutical interventions, including social and physical isolation to protect older adults from fatal COVID-19 infection have been associated with deterioration of physical, cognitive, and mental health (National Council on Aging, 2021, World Health Organization, 2021b). Loneliness arising from long periods of isolation can increase the risk of developing dementia, cognitive decline, mental health disorders, and other chronic diseases including cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and diabetes (World Health Organization, 2021b). Approximately 28.6% and 31.2% of the older adults were found to experience loneliness and social isolation respectively during the first 10 months since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, causing worsening mental health (Su et al., 2022). Since the presence of mental health issues is associated with deterioration of cognitive health (Mental Health Coordinating Council, 2015), worsening cognitive function and mental health were reported during isolation in both older adults with dementia (Azevedo et al., 2021, Borelli et al., 2021, Borges-Machado et al., 2020, Rainero et al., 2021, Tsapanou et al., 2021, van Maurik et al., 2020), and older adults with healthy cognition (HC) (Maggi et al., 2021b).

Dementia is a clinical syndrome associated with loss of memory, language, problem-solving and other abilities that severely interferes with daily life, creating significant burdens not only for older adults with dementia but also their caregivers (Brodaty and Donkin, 2009, Cheng, 2017, Sörensen and Conwell, 2011), and national health systems (Department of Health, 2015, Dharmarajan and Gunturu, 2009, Ikeda et al., 2021, Shon and Yoon, 2021). Global estimates suggest that the incidence of dementia will increase from 10 million new cases every year in 2020–78 million and 139 million by 2030 and 2050, respectively (Alzheimer's Disease International, n.d.). Between 2015 and 2050, the number of older adults with dementia is expected to increase by 264%, 223%, 227%, and 116% in low-income countries (LICs), lower-middle-income countries (LMICs), upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), and high-income countries (HICs), respectively (Prince Martin et al., 2015). Since there are limited treatments for dementia, timely diagnosis significantly contributes to minimizing poor health outcomes (World Health Organization, 2019, Robinson et al., 2015). Considerable evidence supports timely diagnosis as potentially providing opportunities for early interventions and dementia risk reduction (Dubois et al., 2016, Wolff et al., 2020). However, due to strict public health restrictions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, discontinuity of health and social care caused delays in assessment, diagnosis, and treatments and also aggravated cognitive decline, causing faster progression of dementia symptoms (Giebel et al., 2021, Giebel et al., 2021; Macchi et al., 2021; Spalletta et al., 2020).

To date, there has been emerging evidence on dementia and the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported an association between dementia and mortality of COVID-19 (Dadras et al., 2022, Hariyanto et al., 2021, July and Pranata, 2021, Liu et al., 2020, Saragih et al., 2021, Tahira et al., 2021), or loneliness during isolation associated with increased risk of dementia (Lazzari and Rabottini, 2021). Other reviews addressed the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and isolation on older adults with Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia, including physical deterioration and accelerated ageing (Lebrasseur et al., 2021), changes in neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia (Gaigher et al., 2022, Lebrasseur et al., 2021, Manca et al., 2020, Numbers and Brodaty, 2021, Sánchez-García et al., 2022, Simonetti et al., 2020, Suárez-González et al., 2021), worsening cognitive health (Giebel et al., 2022, Suárez-González et al., 2021), as well as new-onset dementia during the first year of COVID-19 isolation (Suárez-González et al., 2021). Although, worsening or new-onset cognitive impairment and subjective mental health deterioration are considered a precursor to dementia, proportions of older adults with dementia and HC experiencing these symptoms for the two-year-and-a-half pandemic period is not well understood. Changes in cognition are commonly measured by subjective cognitive decline (SCD). Although self-reported experience may not be regarded as one of the objective diagnostic tests by healthcare professionals, SCD is an appropriate and recommended assessment to investigate the earliest noticeable symptoms of dementia for older adults with HC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018, Parfenov et al., 2020). Changes in cognition were also measured for older adults with dementia in community and care homes during strict pandemic restrictions (Suárez-González et al., 2021). Subjective mental health deterioration, on the other hand, is used to investigate mental health conditions (Wang et al., 2020), including worsening symptoms of BPSD among older adults with dementia (Garvin, 2021), and worsening mental health among older adults with HC (Robb et al., 2020). Lack of timely and proper diagnosis and management of cognitive decline may result in more advanced stages of dementia. It is hypothesized that worsening cognitive function and mental health deterioration are parts of the hidden iceberg that impact the overall health and wellbeing of the aging population and their families while accelerating incremental demand for healthcare services and national healthcare spending. Since each country’s public health measures were dissimilar to contain the COVID-19 outbreak, it is also hypothesized that the influence of these contextual factors might have led to differences in these reported outcomes.

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the impact of social isolation from COVID-19-related public health measures on subjective worsening of cognitive function and subjective mental health deterioration among older adults with dementia and HC during the two-year-and-a-half pandemic period between March 2020 and September 2022. We considered the impact of the sudden and drastic changes from COVID-19 public health policies on social restrictions as the minimum period of social isolation. Since the start of the pandemic, most countries have implemented restrictions on mobility to reduce the spread of COVID-19, as acting early and decisively was associated with the number of newly confirmed cases (Oh et al., 2021). These restrictions include limited community mobility and congestion reduction in healthcare utilization (Fakir and Bharati, 2021). Older adults who lived at home faced social isolation from physical distancing and lockdown measures preventing them from regular activities, while those in residential care facilities faced isolation from regular family visits (World Health Organization, 2020). Social isolation is the absence or the condition of having inadequate social contacts, which may lead to loneliness (World Health Organization, 2021b). Enforced prolonged conditions of social isolation from COVID-19 policies were reported as one of the two main factors causing worsening neuropsychiatric symptoms in addition to COVID-19 infection (Manca et al., 2020). To investigate studied outcomes for specific population characteristics and sources of heterogeneity, we did subgroup analyses by contextual factors, including length of isolation, stage of dementia, care options, and severity of mobility restrictions. We also did a critical appraisal of the evidence and meta-analysis.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (Cochrane, 2021b). Pubmed Central, Medline, CINAHL Plus and PsychINFO were searched between March 1, 2020, and September 30, 2022. We used the following Medical Subject Heading terms for cognitive function and mental health (“dementia,” “Alzheimer,” and “cognitive”), for disease outbreak (“pandemic,” “outbreak,” and “epidemic”), for older adults (“aged”, “older”, and “senior”). Our search strategies were broad to capture a wide range of articles that would have fit into our analysis framework. A detailed description of the searches is listed in the supplementary table A.

The supplementary table B presents the comprehensive eligibility criteria based on PICO. The inclusion criteria were: original observational studies published in peer-review journals with either cohort, case control or quantitative-based cross-sectional study design; written in English; participants with the mean or the median with a minimum age above 60 years (World Health Organization, 2021a) living in community (either at private or residential care facilities); and being exposed to social isolation as stated by research authors. Social isolation from COVID-19-related public health measures is defined as limited or no social and physical activities due to mobility restrictions. The minimum period of the isolation is considered as right after the sudden and drastic changes from COVID-19 public health policies on social restrictions.; studies with primary data on proportions of participants with subjective worsening of cognitive function and subjective deterioration of mental health from social isolation. We excluded studies that were case reports, case series, and of any design that reported qualitative data; participants exposed to social isolation with the mean or the median with a minimum age below 60; participants being hospitalized; and reported unclear data or different measures from percent proportions of worsening cognitive impairment and worsening BPSD in older adults with dementia, and SCD and worsening mental health in older adults with HC; and participants whose cognitive function and mental health deteriorated for reasons other than social isolation from COVID-19 public health measures stated by research authors.

Two review authors (PP and KL or PP and YC) inspected all identified references independently based on assignments, and critically determined potentially eligible studies for inclusion. Initially, titles and abstracts of the identified studies were independently screened and assessed against eligibility criteria. Then, potentially eligible studies were further evaluated, with two authors (PP and KL or PP and YC) independently reviewing selected full articles regarding the abovementioned criteria. Finally, the third reviewer (SN, MH, HS, or MH) resolved all disagreements.

2.2. Data analysis

Two review authors (PP and KL or PP and YC) independently completed a standardized checklist for each included study. The items on the checklist included: article title, first author’s name, year of publication, study period, country of study, sample size, age, gender, study design, data collection method, outcome assessment reference, symptom of mental health (for HC), and reported proportions of subjective worsening of cognitive function and subjective mental health deterioration. We also categorized factors that might have influenced worsening cognitive function and mental health deterioration, such as length of isolation, stage of dementia, care options, and severity of mobility restriction measures.

A classification of our study populations and outcomes is provided in supplementary figure A. Worsening cognitive impairment (Suárez-González et al., 2021) and SCD (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018, Jessen et al., 2014, Parfenov et al., 2020) were assessed by a self-reported experience questionnaire which measures subjective worsening cognitive function in older adults with dementia and with HC to estimate the impact of social isolation. Subjective mental health deterioration was also assessed by a self-reported questionnaire (Wang et al., 2020). We separately categorized worsening BPSD in older adults with dementia from worsening mental health in older adults with HC. In our study, “Worsening BPSD” is a self-reported experience of worsening of at least one behavioral or psychological symptom such as agitation, anxiety, depression, and delusion in older adults with dementia (Cohen et al., 2020), while “Worsening mental health” is a self-reported experience of worsening mental health conditions in older adults with HC (Robb et al., 2020). For “Worsening mental health”, we collected data on symptoms of mental conditions. We included studies undertaking structured or semi-structured interviews with informal caregivers. Proportional meta-analysis was conducted to calculate the pooled proportion from an individual proportion of each study and synthesize the evidence. We reported the findings as the percentage. One type of using proportion is to accumulate the number of incidences indicating how often including identifying new cases that the disease develops. Proportional meta-analysis was considered appropriate when estimating global disease burden from the syntheses of the single group data (Barker et al., 2021).

During the pandemic, mobility restrictions impacted older adults’ physical and social activities, which led to worsening cognitive function and mental health. Therefore, we also categorized the included studies by unhealthy lifestyle factors (i.e., limited social activities, limited physical activity, ineffective management of depression and postponement of clinical appointments) of older adults with dementia and HC (World Health Organization, 2019).

2.3. Quality evaluation

Many studies might have encountered logistic difficulties while conducting primary research during the pandemic. Since any insights generated during this period are valuable, we appraised the quality of included studies only after the final selection. In order to examine the quality of our included studies, we used the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) for non-RCT (Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2021), and Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) for quantitative cross-sectional studies (Downes et al., 2016). Two reviewers (PP and KL or PP and YC) assessed quality of the included studies independently before reaching consensus. Then, the third reviewers (KL or YC) resolved all disagreements.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We used R to conduct data analyses. Due to a high level of heterogeneity among populations (Barendregt et al., 2013), random-effects meta-analysis models with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were employed to estimate pooled percent proportions of subjective worsening of cognitive function and subjective mental health deterioration in older adults with dementia and HC. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochrane’s scale for heterogeneity with I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of variation among included studies. I2 of more than 75% indicates substantial heterogeneity (Higgins et al., 2003). We conducted subgroup meta-analyses when there were at least 4 studies per subgroup (Rongwei et al., 2010). Differences between subgroups of proportional meta-analyses were compared using Chi2 test (Barker et al., 2021). Subgroup differences with p-values< 0.10 were treated as statistically significant subgroup effects (Richardson, 2019). To investigate publication bias, we used the Egger test of bias with p < 0.05 indicating significant publication bias (Egger et al., 1997). As recommended by Cochrane, we also used tests for funnel plot asymmetry when there were at least 10 studies in the meta-analyses (Cochrane, 2021a).

2.4.1. Older adults with dementia

We conducted subgroup meta-analyses by length of isolation, stage of dementia, care options, and severity of mobility restriction measures for worsening cognitive impairment and BPSD of older adults with dementia. We stratified length of isolation into three subgroups: ≤ 60 days, 61–120 days, and > 120 days as 60-day lockdown was proposed as an effective duration to contain the spread of COVID-19 (López and Rodó, 2020). We identified the stage of dementia into three groups: Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), mild to moderate dementia, and severe dementia, based on cognitive assessment scores of the studied populations. We classified care options into private facilities - homecare and residential care facilities. We also stratified severity levels of public health and social measures implemented by each country using a scale developed by the WHO (1-least severe to 5-most severe) (World Health Organization, 2022).

We did sensitivity analyses to confirm that meta-analyses were not influenced by outliers and studies with high risk of bias. We identified outliers from studies with a strong influence on outcomes and a high contribution to overall heterogeneity with a meta-regression using the metafor package. We identified studies with medium-high and high risks of bias from quality evaluation consensus. We used the Egger test and funnel plots to investigate publication bias.

2.4.2. Older adults with healthy cognition (HC)

We conducted a subgroup meta-analysis of worsening mental health by symptoms of mental disorder, including worsening depression, worsening anxiety, and worsening overall mental health. We did not conduct a subgroup meta-analysis of SCD due to the limited number of included studies.

Due to the limited number of included studies, we used only the Egger test to investigate publication bias. We did sensitivity analyses for the meta-analysis of SCD but not for worsening mental health for the same reason.

3. Result

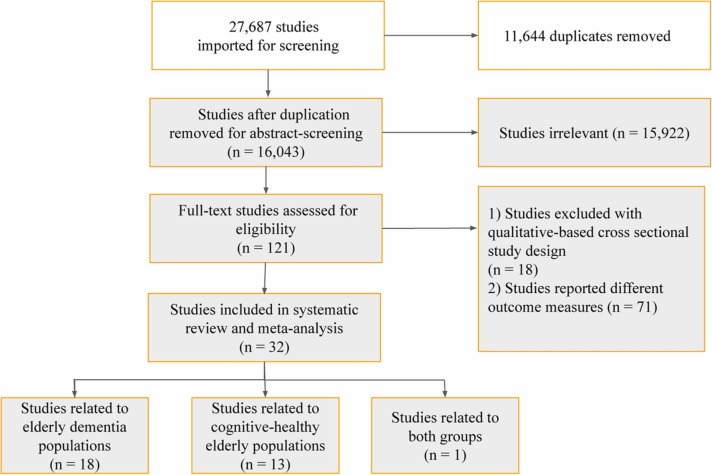

Our search yielded 27,687 studies (PubMed Central 23,324, Medline 2940, CINAHL Plus 1404, PsycINFO 19), as shown in supplementary table A. A total of 11,644 duplicate studies were removed, leaving 16,043 studies for title and abstract screening. After title and abstract screening, we then excluded 15,922 studies that did not meet eligibility criteria. Therefore, 121 studies were included for full-text screening. After removing 18 studies with qualitative-cross sectional study design and 71 studies that reported outcome measures other than the proportion of those with subjective worsening of cognitive function and mental health deterioration, 32 studies were included in the meta-analysis ( Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA report of inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

3.1. Study characteristics

Study characteristics are provided in supplementary table C-E. Among 32 studies, 18 addressed the impact of social isolation on older adults with dementia, 13 focused on older adults with HC, and one was related to both dementia and HC groups. Among the 19 studies on older adults with dementia, only eight investigated outcomes by stage of dementia. Of these 19 studies referring to older adults with dementia, 16 highlighted limited social activities as a lifestyle risk factor, one highlighted postponement of clinical appointments, one highlighted limited physical activity, and one highlighted overall lifestyle change. Among the 14 studies referring to older adults with HC, six highlighted limited social activities as a lifestyle risk factor, four highlighted ineffective management of depression, two highlighted limited physical activities, one highlighted both limited social activities and limited physical activities, and one highlighted overall changes in lifestyle. The study that referred to both groups highlighted limited social activities as a lifestyle risk factor.

Included studies involved 18 countries in three regions (Europe, Asia Pacific and Latin America). Twenty-eight studies were conducted in high-income countries (HICs), while four were conducted in upper-middle-income countries (UMICs). Italy had the highest number of eligible studies (nine studies), followed by the United Kingdom (four studies) and Japan (four studies), and France (three studies). The rest were conducted in Argentina, Brazil, China, Finland, Greece, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Turkey, Spain, Austria, Argentina-Brazil-Chile, and Australia-Germany-Netherlands-Spain (one study each). Among 19 studies referring to older adults with dementia, 13 were conducted in countries with high severity of mobility restrictions, while six were conducted in countries with low- to medium severity.

Among 32 studies, 28 were cross-sectional quantitative studies, while the rest (four studies) comprised cohort designs. Twelve studies were published in 2020, 13 studies were published in 2021, and seven studies were published in 2022. Of 32 studies, 20 were conducted between March–July 2020, two were conducted between August–December 2020, and five were conducted between March-December 2020. Meanwhile, three studies were conducted between January–June 2021 and one was conducted between August 2020–June 2021. No studies were conducted between July 2021-September 2022. One study reported data from two periods of March-July 2020 and July-December 2021.

Among 32 studies, one investigated two groups residing in private and residential care facilities covering two periods of March-July 2020 and July-December 2021. The rest (31 studies) investigated individual groups residing in private facilities receiving homecare. Among 19 studies investigating older adults with dementia, seven studies addressed < =60 days of social isolation from their study periods, nine studies addressed 61–120 days, two studies addressed > 120 days, and one addressed two periods of 61–120 days and > 120 days. Among 14 studies investigating older adults with HC, four addressed < =60 days of social isolation, three addressed 61–120 days, six addressed > 120 days, and one did not state the study period.

3.2. Impact of COVID-19-related isolation

A summary of included studies with corresponding percent proportions of worsening cognitive impairment and BPSD among older adults with dementia is provided in supplementary table F, and a summary of included studies with corresponding percent proportions of SCD and worsening mental health among older adults with HC is provided in supplementary table G.

3.2.1. Older adults with dementia

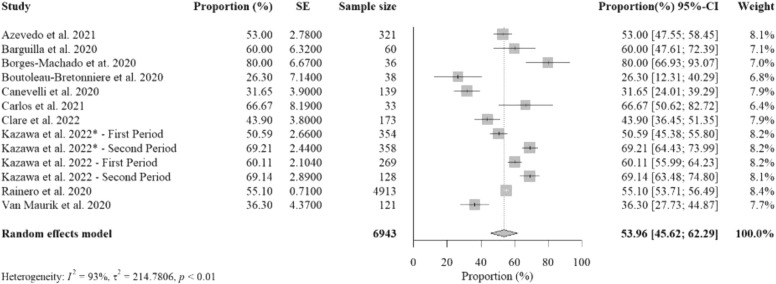

3.2.1.1. Worsening cognitive impairment

Ten studies (13 studied groups) reported data on percent proportions of older adults with dementia experiencing worsening cognitive impairment from social isolation with a total sample size of 6943. The pooled percent proportion was 53.96% [95%CI: 45.62%− 62.29%, p-value< 0.01] ( Fig. 2). Studies that reported the highest percent proportions were from Portugal (Borges-Machado et al., 2020), Italy (Carlos et al., 2021), and Spain (Barguilla et al., 2020), due to limited social activities. Another study from Japan (Kazawa et al., 2022) reported ones of the highest proportions from both groups who resided in private and residential care facilities, possibly due to more prolonged isolation than other studies until the second period of July-December 2021. Of the 10 studies, data from seven studies were collected by structured telephone interviews, while two used paper-based surveys and one used online survey. Of those seven studies using structured telephone interviews, five was performed with informal caregivers, one was performed with dementia patients, and one was with either informal caregivers or dementia patients. In addition, two studies that used paper-based surveys were conducted with informal caregivers, while one with online survey was conducted with formal caregivers.

Fig. 2.

The overall random-effects pooled percent proportion of worsening cognitive impairment among older adults with dementia.

Studies that investigated older adults with more than 120-day length of isolation reported the highest pooled percent proportion (60.94%) than those with 61–120-day length of isolation (56.07%) and those with less than 60-day length of isolation (44.76%) (supplementary figure B.1). Studies that investigated older adults with severe dementia reported the highest pooled percent proportion (65.93%) than those with MCI (58.68%) and mild-to-moderate dementia (57.90%) (supplementary figure B.2). Studies that investigated older adults residing in private facilities reported a lower pooled percent proportion (52.80%) than those residing in residential care facilities (59.93%) (supplementary figure B.3). Studied countries with high severity of mobility restriction measures also reported a slightly lower pooled percent proportion (51.86%) than those in countries with low-medium severity restrictions (57.28%) (supplementary figure B.4).

There were no statistically significant subgroup differences for length of isolation (p = 0.41), severity of dementia (p = 0.48), care options (p = 0.50), and severity of mobility restrictions (p = 0.49) (supplementary table H.1).

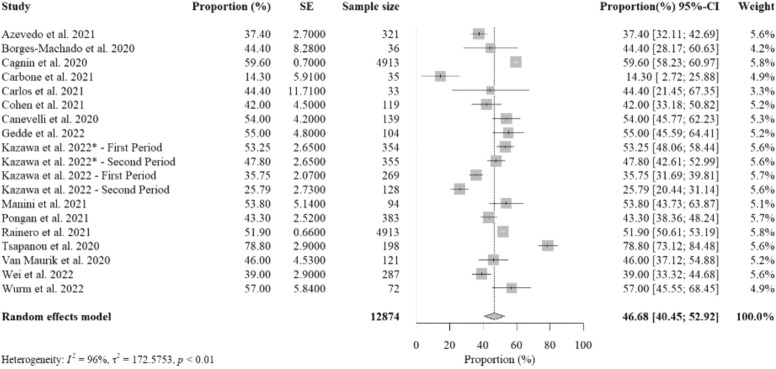

3.2.1.2. Worsening BPSD

Sixteen studies (19 studied groups) reported data on the percent proportions of older adults with dementia experiencing worsening BPSD from social isolation with a total sample size of 12,874. The pooled percent proportion was 46.68% [95%CI: 40.45%− 52.92%, p-value< 0.01] ( Fig. 3). Included studies that addressed the highest percent proportions were from Greece (Tsapanou et al., 2021), and Italy (Cagnin et al., 2020, Manini et al., 2021), due to limited social activities, and Austria (Wurm et al., 2022), due to limited physical activity. Postponements of clinical appointments (Gedde et al., 2022), and change of overall lifestyle (Kazawa et al., 2022) also contributed to worsening BPSD in studied populations. Of the 16 studies, nine were conducted by structured telephone interviews, six used online or paper-based surveys, and one used structured interview at a clinic. Of the nine studies conducted by structured telephone interviews, seven interviewed informal caregivers, one interviewed dementia patients, and one interviewed either dementia patients or informal caregivers. Of the six studies conducted by survey, four were with informal caregivers, one was with dementia patients, and one was with formal caregivers. One study using structured interviews at the clinic was conducted with informal caregivers.

Fig. 3.

The overall random-effects pooled percent proportion of worsening behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) among older adults with dementia.

Studies that investigated older adults with less than the 60-day length of isolation reported the highest pooled percent proportion (52.80%) than those with 61–120-day length of isolation (46.58%) and those with more than 120-day length of isolation (37.54%) (supplementary figure C.1). Studies that investigated older adults with MCI reported the highest pooled percent proportion (55.78%) than those with severe dementia (44.35%) and mild-to-moderate dementia (41.84%) (supplementary figure C.2). Studies that investigated older adults residing in residential care facilities reported a higher pooled percent proportion (50.52%) than those in private facilities (46.18%) (supplementary figure C.3). Studied countries with high severity of mobility restriction measures also reported a slightly lower pooled percent proportion (45.47%) than those in countries with low-medium severity restrictions (49.16%) (supplementary figure C.4).

There were no statistically significant subgroup differences for severity of dementia (p = 0.43), care options (p = 0.33), severity of mobility restrictions (p = 0.48), but there was a significant subgroup difference for length of isolation (p = 0.07) (supplementary table H.2).

3.2.2. Older adults with HC

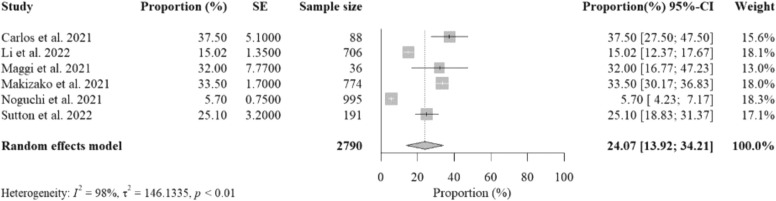

3.2.2.1. Worsening cognitive decline

Six studies reported data on the percent proportions of older adults with HC experiencing SCD from social isolation with a total sample size of 2790. The pooled percent proportion was 24.07% [95%CI: 13.92%− 34.21%, p-value< 0.01] ( Fig. 4). Included studies that reported the highest percent proportions were from Italy (Maggi et al., 2021b), due to ineffective management of depression, the UK (Bailey et al., 2021), due to limited social activities, and Japan (Makizako et al., 2021), due to limited physical activity. Strict mobility restrictions during study implementation were reported as the cause of these unhealthy lifestyles. Data collection methods varied among the six studies, including structured telephone interviews, mail surveys, and web-based surveys.

Fig. 4.

The overall random-effects pooled percent proportions of subjective cognitive decline (SCD) among older adults with healthy cognition (HC) (Noguchi et al., 2021, Sutton et al., 2022).

3.2.2.2. Worsening mental health

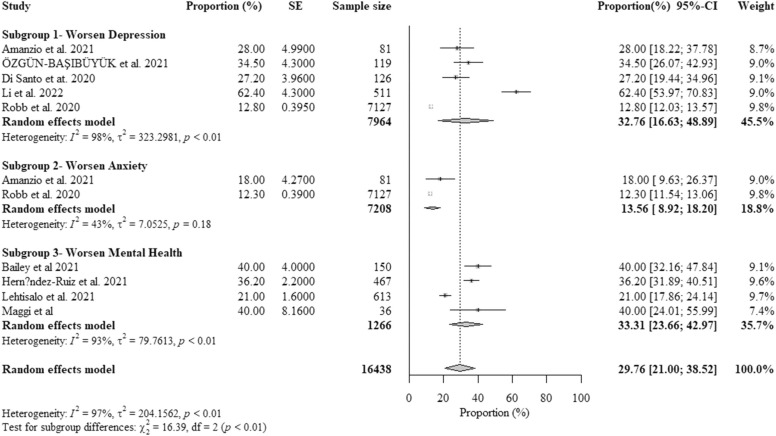

Nine studies reported data on the percent proportions of older adults with HC experiencing worsening mental health from COVID-19-related isolation. The pooled percent proportion was 29.76% [95%CI: 21.00%− 38.52%, p-value< 0.01] ( Fig. 5). Included studies that reported the highest percent proportions were from China (Li et al., 2022b), due to limited physical activity, followed by the UK (Robb et al., 2020), due to limited social activities, and Italy (Maggi et al., 2021a), due to ineffective management of depression and mental health.

Fig. 5.

The overall random-effects pooled percent proportion of worsening mental health among older adults with healthy cognition (HC) (Özgün-Başıbüyük et al., 2021).

Older adults with HC reported higher pooled percent proportions of worsening depression (32.76%) and worsening overall mental health (33.31%) than a pooled percent proportion of worsening anxiety (13.56%). There was a statistically significant subgroup difference for symptoms of mental illness (p < 0.01) (Fig. 5).

3.3. Quality assessment

The results of the quality assessment are shown in supplementary table I. Among the 28 quantitative-based cross-sectional studies, 11 studies (39.29%) showed low risk of selection and information bias, 11 studies (39.29%) showed moderate risk from either low selection or information bias, and six studies (21.42%) showed high risk of both selection and information bias. In most studies, serious risk of bias was due to limitations in study population selection and study design during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions (i.e., voluntary participation, self-completed questionnaires by participants, self-developed questions by researchers). Among four cohort studies, three studies (75.00%) showed medium-low risk (low selection and comparability bias but high outcome bias), while one study (25.00%) showed medium-high risk (low comparability bias but high selection and outcome bias). All cohort studies presented high outcome bias due to remote structured interviews held during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. Of those, one study reported high selection bias due to the high percentage of study population drop-offs. In total, among all 32 included studies in our systematic review and meta-analysis, seven studies (21.86%) presented either medium-high or high risk of overall bias.

3.4. Heterogeneity, publication bias and sensitivity analysis

The heterogeneity (I2) ranged from 90.0% to 99.0%, indicating considerable heterogeneity (Cochrane, 2021a). However, we found no evidence of publication bias from funnel plots (supplementary figure D) and Eggar’s test for the pooled percent proportions of worsening cognitive impairment (p = 0.77) and worsening BPSD (p = 0.08) among older adults with dementia (supplementary figure E.1-E.2). We also found no evidence of publication bias from a pooled percent proportion of SCD (p = 0.11) (supplementary figure E.3), while evidence of publication bias was found from a pooled percent proportion of worsening mental health (p < 0.01) (supplementary figure E.4).

Sensitivity analysis of worsening cognitive impairment and BPSD among older adults with dementia showed that excluding studies with outliers (supplementary figure F-G, respectively) or those with high risk of bias (supplementary table I), resulted in marginal differences in pooled percent proportions and heterogeneity (supplementary table J.1-J.2). There were also no statistically significant subgroup differences in worsening cognitive impairment and BPSD among older adults with dementia without outliers and studies with high risk of bias for length of isolation, severity of dementia, care options, and severity of mobility restriction measures (supplementary table H.1-H.2). Sensitivity analysis of SCD among older adults with HC showed that excluding studies either with outliers or high risk of bias resulted in marginal differences in pooled percent proportion and heterogeneity (supplementary table K).

4. Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, subjective worsening of cognitive function and mental health deterioration was found to be common among older adults with dementia and HC during social isolation. We found that proportions of older adults with dementia who experienced worsening cognitive impairment and exacerbation or new onset of BPSD during the two-year-and-a-half period of social isolation from COVID-19-related public health measures were approximately twice larger than that of older adults with HC experiencing SCD and worsening mental health. We found that approximately half (53.96%) of older adults with dementia experienced worsening cognitive impairment, while nearly a quarter (24.07%) of older adults with HC experienced SCD during social isolation. We also found that approximately half (46.68%) of older adults with dementia experienced worsening BPSD, while approximately a quarter (29.76%) of older adults with HC experienced worsening mental health.

This study’s findings highlight how vulnerable older adults are to physical and psychological isolation, especially those with dementia. As dementia patients are most often deprived of short-term memory, the inability to adjust to new norms is likely the main driver of the above-mentioned findings. We found that a higher number of older adults with dementia residing in residential care facilities reported worsening cognitive impairment and BPSD (59.93% and 50.52%) than those in private facilities (52.80% and 46.18%). We also found that a higher number of older adults with severe dementia reported worsening cognitive impairment (65.93%) and BPSD (44.35%) than those with mild-to-moderate dementia on worsening cognitive impairment (57.90%) and BPSD (41.84%). The severity of mobility restriction was not necessarily the cause of the increasing number of older adults with dementia who reported worsening cognitive impairment and BPSD or new onset of these symptoms during isolation. The more extended period of isolation was also not necessarily the cause of the increasing number of older adults with dementia who reported worsening BPSD but was with worsening cognitive impairment. More than half of the older adults with dementia (52.80%) experiencing worsening BPSD during the first 60-day period of isolation was possibly an outcome of the sudden and drastic changes of the COVID-19 public health policies on social restrictions. However, although not significantly associated with the proportion of worsening BPSD, this duration of confinement was found to be correlated with the severity of symptoms among older adults with dementia (Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2020). Most included studies addressed how critical social activities are to maintain a healthy lifestyle and prevent cognitive decline for older adults with dementia.

This study also found a large proportion of older adults with MCI experiencing worsening cognitive impairment (58.68%) and worsening BPSD (55.78%) during isolation. MCI, an early sign of worsening memory problems, can potentially increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia. Typically, annual conversion rates from MCI to dementia range from 5% to 10% (Mitchell and Shiri-Feshki, 2009) to 10–15% (Mayo Clinic, 2022; Mitchell and Shiri-Feshki, 2009). The rate can increase to 23.8% in low-middle-income countries (LMICs) (McGrattan et al., 2022). Such accelerated proportions in studied populations with MCI may provide interesting clues on which social factors and lifestyle changes during the pandemic significantly affect the cognitive and mental health of older adults with MCI at a similar level as those with dementia.

Meanwhile, nearly one-quarter of older adults with HC reported SCD and worsening mental health during social isolation. We found a statistically significant subgroup difference for symptoms of mental health, meaning that this factor modified the percent proportion of worsening mental health among this population. Worsening depression was the most reported symptom (32.76%) compared to other symptoms, which is higher than the previous global estimation of approximately 15% of older adults with depression before the pandemic by WHO (World Health Organization, 2017). Although depressive symptoms and SCD can be seen as independent factors of cognitive decline, co-occurrence of SCD and depression has a combined effect on the risk of dementia (Jessen et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2021). Clinically, depression often masks and mimics dementia, leading to more complicated care needs and increased caregiver burden. For cognitive decline, limited social activities was the primary cause of SCD for older adults with HC (Bailey et al., 2021, Carlos et al., 2021), while limited physical activities (Makizako et al., 2021), and limited management of depression (Maggi et al., 2021b) were also significant causes. For worsening of mental health, limited social activities was again the primary cause for older adults with HC (Bailey et al., 2021), while ineffective management of depression (Amanzio et al., 2021, Di Santo et al., 2020, Maggi et al., 2021b, Robb et al., 2020), limited physical activities (Li et al., 2022b), and change of overall lifestyles (Lehtisalo et al., 2021) were found to be additional causes. However, exposure to lifestyle risk factors on their own are not direct causes of dementia but rather factors that increase the chance of developing dementia (Alzheimer Society, 2022).

We also observed substantial heterogeneity in meta-analysis estimates but no publication bias in most studies except the meta-analysis of worsening mental health among older adults with HC. Substantial heterogeneity was suspected from differences among studies including settings, types of participants, and methodological differences. Publication bias was suspected, perhaps, due to larger outcomes from smaller studies (Sterne et al., 2000), and the possibility of cultural differences in reporting worsening mental health. We believe that the heterogeneity of assessment tools and differing choices in the way of reporting data could explain the variability in percent proportions.

4.1. Comparison with other studies

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis on pooled percent proportions of subjective worsening cognitive function and mental health among older adults with dementia and HC during the two-year-and-a-half pandemic period. One rapid systematic review investigated changes in cognition and BPSD and new-onsets of dementia during the first year of COVID-19 isolation (Suárez-González et al., 2021). This study reported worsening in cognition ranging from 20% to 80%, while worsening in BPSD was estimated as 22–75% of the total population. Another meta-analysis published in 2021 investigated the pooled prevalence of new-onsets of dementia in the populations of 8239 aged above 50 years from the included studies mainly in the previous 5 years (Lazzari and Rabottini, 2021). They found that the risk of developing dementia because of loneliness during the prolonged isolation period was 49–60% higher than in those who were not lonely and isolated. Meanwhile, one systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of the elderly population from database inception to 2 June 2021, with a pooled increase in neuropsychiatric inventory score (NPI) before and during the pandemic as a study measure (Soysal et al., 2022). NPI is one of the most used scales to assess the presence and severity of NPS (Musa et al., 2017). The meta-analysis addressed worsening NPS from the average score of NPI increased by 3.85 points from 420 participants of the 7 included studies, with reported worsening in depression, anxiety, agitation, irritability, and apathy as the most common NPS during the lockdown. Increased scores of more than 2.77–3.18 indicate clinically significant differences (Mao et al., 2015). During the pandemic, another review also addressed apathy, anxiety, and agitation as the most frequently NPS causing by prolonged isolation (Simonetti et al., 2020).

As other pandemics can occur again in the future, how to best implement effective physical distancing measures while promoting healthy lifestyles to prevent further cognitive decline and worsening mental health need to be investigated. Although staying isolated was effective in protecting older adults from COVID-19 infections (Chu et al., 2021, Jawaid, 2020), especially those living in care homes (Numbers and Brodaty, 2021), these measures were also disruptive to their physical, cognitive, and mental health.

4.2. Strengths and limitations of this review

The main strength of this systematic review was the use of a comprehensive search strategy from the beginning of the implementation of public health restrictions between March 1, 2020, and September 30, 2022. This review followed an appraisal process that is recommended by Cochrane to assess the risk of bias of included studies. However, our research has some limitations.

First, although there were sufficient studies for meta-analyses of worsening cognitive impairment and BPSD among older adults with dementia, we included a small number of studies in two meta-analyses of pooled percent proportions of SCD (6 studies) and worsening mental health (2–5 studies for each subgroup) among older adults with HC. Excluded studies reported different measures, including prevalence and clinical outcome measures. As a result, subgroup meta-analyses were limited to older adults with dementia.

Second, worsening outcomes reported by included studies during this two-year-and-a-half pandemic period may not ideally separate the typical natural course of dementia from an exclusive impact from social isolation from COVID-19-related public health measures. Although our search covered the two-year-and-a-half period between March 2020 and September 2022, the majority of included studies reported outcomes in the first year of the pandemic (29 studies, 90.63%), especially those 21 studies reported within the first 6-month period (65.63%). Since worsening neuropsychiatric conditions and dementia are deteriorated gradually over time, this unusual and short period does not seem to reflect the natural course of dementia. We also limited the evidence we have reviewed to studies that converge toward the impact of social isolation from COVID-19-related public health measures, as stated in their study objectives.

Third, a lack of reported proportions by characteristics of older adults, including age and gender, are the limitation to conducting other subgroup meta-analyses. For example, only one study reported proportions of worsening SCD among older adults with HC aged 70–79 and > 80 (Li et al., 2022a), while none reported separated proportions between gender. As annual age-specific incident rates or percent proportions of dementia range from 0.1% at age 60–64–8.6% at age 95, the figures were addressed either similar in men and women or marginally larger in women (Hugo and Ganguli, 2014). In addition, although there is more gender vulnerability toward dementia for women (Mielke, 2018), causing a higher prevalence of dementia in women than men, it does not apply to the incident rate or percent proportion at which new dementia occurs as the higher prevalence is associated with a longer life expectancy in women (Hugo and Ganguli, 2014). Therefore, it is relatively reasonable to not including age and gender into factors for subgroup meta-analyses. Furthermore, most studies did not identify older adults with psychiatric or severe depressive disorders in the exclusion criteria, except two studies (Barguilla et al., 2020, Carlos et al., 2021) for worsening cognitive impairment and one study (Carlos et al., 2021) for SCD. Although these two meta-analyses did not perfectly differentiate outcomes from this group, it is in line with investigating incidence of dementia for an index of the risk of new cases in overall older population with dementia (Hugo and Ganguli, 2014).

Forth, most of the included studies were periodically investigated. Therefore, the findings could represent the impact of a specific study period, while the outcomes varied depending on individual experiences and cultural differences in reporting subjective outcomes. We observed that these subjective measures were mostly used in high-income countries to follow-up disease progression during strict mobility restrictions to protect older adults before receiving COVID-19 vaccination. However, we would encourage future research to investigate long-term outcomes by using clinical assessment by healthcare professionals in health and social care facilities and continuing to use proactive subjective assessments in the community.

Fifth, the included studies were conducted in different countries where COVID-19-related public health measures and environments were variable. We would encourage future research to investigate the impact of social isolation on worsening cognitive function and mental health deterioration associated with lifestyle risk factors in the individual countries. We also encourage using proactive subjective assessments prior to evidence-based clinical assessments to address the potential risks of dementia in LMICs where 60% of the global dementia population is located (Prince Martin et al., 2015).

Furthermore, although the questions were adopted from well-established assessment scales, there were some sources of information bias from data collection methods using self-developed questionnaires and structured telephone interviews. We also observed heterogeneity of assessment tools and choices of reported data which could manifest as variability in percent proportions. The possibility of cultural differences and different judgements of caregivers and older adults in reporting worsening cognitive function and mental health may also lead to social-desirability bias in our study. Since all studies were conducted during the pandemic period, we included these articles conducted in different countries for comparison with quality assessment and sensitivity analysis.

4.3. Policy implications

Our findings support the WHO’s recommendation on adopting healthy lifestyles to delay or prevent cognitive decline and dementia (World Health Organization, 2019). This study has proven that isolation and mobility restrictions made maintaining healthy lifestyles challenging and should encourage policymakers to balance the risk and benefits of isolation for older adults. Perhaps the creation of a “support bubble” where older adults can safely expand the number of people they are in close contact should be encouraged during future public health crises (Trotter, 2021). More highly individualized care to enhance mental health may be offered to those at risk.

Furthermore, the included studies in our systematic review also addressed the importance of proactive use of subjective cognitive function and mental health assessments. Proactive approaches to identify dementia risks in the community are recommended by the WHO (World Health Organization, 2018) and others (Hugo and Ganguli, 2014, Larner, 2019, Robinson et al., 2018) and should be integrated into national health policy. Not only older adults with dementia, but changes in neuropsychiatric manifestations in older adults with HC and MCI need to be monitored proactively for early detection to delay MCI and more severe stages of dementia, respectively.

Home health aides and other caregivers play a crucial role in helping dementia patients live at home (Suzanne, 2019). Since these patients are dependent on others for care, worsening cognition (Borelli et al., 2021), and behavioral symptoms increase the burden and psychological distress experienced by caregivers (Cohen et al., 2020). During social isolation, one of the most concerning issues for caregivers was reportedly the discontinuity of dementia care. Accessibility to continued consultation and professional support for both older adults with dementia and their caregivers should be robustly supported and protected (Pongan et al., 2021, Tsapanou et al., 2021, van Maurik et al., 2020). WHO has also recommended support for caregivers as one of the key action areas of the WHO’s Global Dementia Observatory Framework because of their essential role in supporting dementia care (World Health Organization, 2018).

5. Conclusion

This study highlights the impact of social isolation from COVID-19-related public health measures on subjective worsening cognitive function and mental health among older adults. The findings support the conclusion that social isolation results in the subjective worsening of cognitive function and mental health deterioration among a more significant proportion of older adults with dementia than those with HC. The study also addresses unhealthy lifestyles during social isolation resulting in worsening cognitive and mental health outcomes. Public health efforts should consider promoting healthy lifestyles while equipping public health responses to future pandemics.

Footnotes

Contributors

Conception/design of the work: PP, SN, HM; analysis of data: PP, KS, SN; interpretation of findings: all authors; drafting of the work: PP; substantially revised the work: all authors.

Funding

No.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for this secondary analysis of publicly available data.

Patient and public involvement

Since this research is based on published articles, there is no patient and public involvement.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.arr.2022.101839.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

Supplementary material

.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Alzheimer Society, n.d. Risk factors for dementia. https://alzheimer.ca/en/about-dementia/how-can-i-prevent-dementia/risk-factors-dementia (Accessed 24 August 2022).

- Alzheimer's Disease International, n.d. Dementia Statistics. https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/dementia-statistics/ (Accessed 24 August 2022).

- Amanzio M., Canessa N., Bartoli M., Cipriani G.E., Palermo S., Cappa S.F. Lockdown effects on healthy cognitive aging during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.685180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo L.V. d S., Calandri I.L., Slachevsky A., Graviotto H.G., Vieira M.C.S., Andrade C.B. d, Rossetti A.P., Generoso A.B., Carmona K.C., Pinto L.A.C., Sorbara M., Pinto A., Guajardo T., Olavarria L., Thumala D., Crivelli L., Vivas L., Allegri R.F., Barbosa M.T., Caramelli P. Impact of social isolation on people with dementia and their family caregivers. J. Alzheimer'S. Dis. 2021;81(2):607–617. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey L., Ward M., DiCosimo A., Baunta S., Cunningham C., Romero-Ortuno R., Kenny R.A., Purcell R., Lannon R., McCarroll K., Nee R., Robinson D., Lavan A., Briggs R. Physical and mental health of older people while cocooning during the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM: Int. J. Med. 2021:hcab015. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcab015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barendregt J.J., Doi S.A., Lee Y.Y., Norman R.E., Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2013;67(11):974–978. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barguilla A., Fernández-Lebrero A., Estragués-Gázquez I., García-Escobar G., Navalpotro-Gómez I., Manero R.M., Puente-Periz V., Roquer J., Puig-Pijoan A. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic confinement in patients with cognitive impairment. Front. Neurol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.589901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker T.H., Migliavaca C.B., Stein C., Colpani V., Falavigna M., Aromataris E., Munn Z. Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: a guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Med Res Method. 2021;21(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s12874-021-01381-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borelli W.V., Augustin M.C., de Oliveira P.B.F., Reggiani L.C., Bandeira-de-Mello R.G., Schumacher-Schuh A.F., Chaves M.L.F., Castilhos R.M. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia associated with increased psychological distress in caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Alzheimer'S. Dis. 2021;80(4):1705–1712. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges-Machado F., Barros D., Ribeiro Ó., Carvalho J. The Effects of COVID-19 home confinement in dementia care: physical and cognitive decline, severe neuropsychiatric symptoms and increased caregiving burden. Am. J. Alzheimer'S. Dis. Other Dementias®. 2020;35 doi: 10.1177/1533317520976720. 1533317520976720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutoleau-Bretonnière C., Pouclet-Courtemanche H., Gillet A., Bernard A., Deruet A.L., Gouraud I., Mazoue A., Lamy E., Rocher L., Kapogiannis D., El Haj M. The effects of confinement on neuropsychiatric symptoms in alzheimer’s disease during the COVID-19 Crisis. J. Alzheimer'S. Dis. 2020;76(1):41–47. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H., Donkin M. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialog-. Clin. Neurosci. 2009;11(2):217–228. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/hbrodaty. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagnin A., Di Lorenzo R., Marra C., Bonanni L., Cupidi C., Laganà V., Rubino E., Vacca A., Provero P., Isella V., Vanacore N., Agosta F., Appollonio I., Caffarra P., Pettenuzzo I., Sambati R., Quaranta D., Guglielmi V., Logroscino G., Bruni A.C. Behavioral and psychological effects of coronavirus disease-19 quarantine in patients with dementia. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.578015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos A.F., Poloni T.E., Caridi M., Pozzolini M., Vaccaro R., Rolandi E., Cirrincione A., Pettinato L., Vitali S.F., Tronconi L., Ceroni M., Guaita A. Life during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: the influence of cognitive state on psychosocial, behavioral and lifestyle profiles of older adults. Aging Ment. Health. 2021;0(0):1–10. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1870210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. Subjective Cognitive Decline — A Public Health Issue. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/data/subjective-cognitive-decline-brief.html#:∼:text=Subjective%20Cognitive%20Decline%20(SCD)%20is,frequent%20confusion%20or%20memory%20loss.&text=It%20is%20a%20form%20of,Alzheimer's%20disease%20and%20related%20dementias (Accessed 24 August 2022).

- Cheng S.T. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(9):64. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C.H., Wang J., Fukui C., Staudacher S., P A.W., Wu B. The impact of COVID-19 on social isolation in long-term care homes: perspectives of policies and strategies from six countries. J. Aging Soc. Policy. 2021;33(4–5):459–473. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2021.1924346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, 2021a, 2021–12-23 04:55:43. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (Accessed 24 August 2022).

- Cochrane, 2021b, 2021–12-19 13:45:36. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA Statement for Reporting Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews. https://training.cochrane.org/resource/prisma-s-extension-prisma-statement-reporting-literature-searches-systematic-reviews (Accessed 24 August 2022).

- Cohen G., Russo M.J., Campos J.A., Allegri R.F. COVID-19 epidemic in argentina: worsening of behavioral symptoms in elderly subjects with dementia living in the community. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11:866. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadras O., SeyedAlinaghi S., Karimi A., Shamsabadi A., Qaderi K., Ramezani M., Mirghaderi S.P., Mahdiabadi S., Vahedi F., Saeidi S., Shojaei A., Mehrtak M., Azar S.A., Mehraeen E., Voltarelli F.A. COVID-19 mortality and its predictors in the elderly: A systematic review. Health Sci. Rep. 2022;5(3) doi: 10.1002/hsr2.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Department of Health, 2015. Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414344/pm-dementia2020.pdf (Accessed 21 November 2022).

- Dharmarajan T.S., Gunturu S.G. Alzheimer's disease: a healthcare burden of epidemic proportion. Am. Health Drug Benefits. 2009;2(1):39–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Santo S.G., Franchini F., Filiputti B., Martone A., Sannino S. The Effects of COVID-19 and Quarantine Measures on the Lifestyles and Mental Health of People Over 60 at Increased Risk of Dementia. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.578628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downes M.J., Brennan M.L., Williams H.C., Dean R.S. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS) BMJ Open. 2016;6(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B., Padovani A., Scheltens P., Rossi A., Dell'Agnello G. Timely diagnosis for alzheimer's disease: a literature review on benefits and challenges. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(3):617–631. doi: 10.3233/jad-150692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakir A.M.S., Bharati T. Pandemic catch-22: The role of mobility restrictions and institutional inequalities in halting the spread of COVID-19. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaigher J.M., Lacerda I.B., Dourado M.C.N. Dementia and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.879598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin, K., 2021. Pandemic Worsened Many Older Adults’ Mental Health and Sleep, Poll Finds, But Long-Term Resilience Also Seen. https://healthblog.uofmhealth.org/health-management/pandemic-worsened-many-older-adults-mental-health-and-sleep-poll-finds-but-long.

- Gedde M.H., Husebo B.S., Vahia I.V., Mannseth J., Vislapuu M., Naik M., Berge L.I. Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on behavioural and psychological symptoms in home-dwelling people with dementia: a prospective cohort study (PAN.DEM) BMJ Open. 2022;12(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel C., Sutcliffe C., Darlington-Pollock F., Green M.A., Akpan A., Dickinson J., Watson J., Gabbay M. Health inequities in the care pathways for people living with young- and late-onset dementia: from Pre-COVID-19 to early pandemic. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health. 2021;18(2) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel C., Lion K.M., Lorenz-Dant K., Suárez-González A., Talbot C., Wharton E., Cannon J., Tetlow H., Thyrian J.R. The early impacts of COVID-19 on people living with dementia: part I of a mixed-methods systematic review. Aging Ment. Health. 2022:1–14. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2022.2084509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel C., Pulford D., Cooper C., Lord K., Shenton J., Cannon J., Shaw L., Tetlow H., Limbert S., Callaghan S., Whittington R., Rogers C., Komuravelli A., Rajagopal M., Eley R., Downs M., Reilly S., Ward K., Gaughan A., Gabbay M. COVID-19-related social support service closures and mental well-being in older adults and those affected by dementia: a UK longitudinal survey. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariyanto T.I., Putri C., Arisa J., Situmeang R.F.V., Kurniawan A. Dementia and outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2021;93 doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo J., Ganguli M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2014;30(3):421–442. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S., Mimura M., Ikeda M., Wada-Isoe K., Azuma M., Inoue S., Tomita K. Economic Burden of Alzheimer's Disease Dementia in Japan. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021;81(1):309–319. doi: 10.3233/jad-210075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawaid A. Protecting older adults during social distancing. Science. 2020;368(6487):145. doi: 10.1126/science.abb7885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F., Amariglio R.E., Buckley R.F., van der Flier W.M., Han Y., Molinuevo J.L., Rabin L., Rentz D.M., Rodriguez-Gomez O., Saykin A.J., Sikkes S.A.M., Smart C.M., Wolfsgruber S., Wagner M. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(3):271–278. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30368-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F., Amariglio R.E., van Boxtel M., Breteler M., Ceccaldi M., Chételat G., Dubois B., Dufouil C., Ellis K.A., van der Flier W.M., Glodzik L., van Harten A.C., de Leon M.J., McHugh P., Mielke M.M., Molinuevo J.L., Mosconi L., Osorio R.S., Perrotin A., Wagner M. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- July J., Pranata R. Prevalence of dementia and its impact on mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2021;21(2):172–177. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazawa K., Kubo T., Akishita M., Ishii S. Long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on facility- and home-dwelling people with dementia: Perspectives from professionals involved in dementia care. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2022;22(10):832–838. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larner, A.J., 2019. Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies in Dementia: A Pragmatic Approach: Second Edition (Second ed.). Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2015. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978–3-030–17562-7.

- Lazzari C., Rabottini M. COVID-19, loneliness, social isolation and risk of dementia in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the relevant literature. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2021;0(0):1–12. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2021.1959616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrasseur A., Fortin-Bédard N., Lettre J., Raymond E., Bussières E.L., Lapierre N., Faieta J., Vincent C., Duchesne L., Ouellet M.C., Gagnon E., Tourigny A., Lamontagne M., Routhier F. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Older Adults: Rapid Review. JMIR Aging. 2021;4(2) doi: 10.2196/26474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtisalo J., Palmer K., Mangialasche F., Solomon A., Kivipelto M., Ngandu T. Changes in lifestyle, behaviors, and risk factors for cognitive impairment in older persons during the first wave of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in finland: results from the FINGER study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.624125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Godai K., Kido M., Komori S., Shima R., Kamide K., Kabayama M. Cognitive decline and poor social relationship in older adults during COVID-19 pandemic: can information and communications technology (ICT) use helps? BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):375. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Su S., Luo B., Wang J., Liao S. Physical activity and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults in the COVID-19 pandemic era: A three-wave cross-lagged study. Int J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022;70 doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Sun J., Wang X., Zhao M., Huang Q., Li H. The impact of dementia on the clinical outcome of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimer'S. Dis.: JAD. 2020;78(4):1775–1782. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López L., Rodó X. The end of social confinement and COVID-19 re-emergence risk. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020;4(7):746–755. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchi Z.A., Ayele R., Dini M., Lamira J., Katz M., Pantilat S.Z., Jones J., Kluger B.M. Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for improving outpatient neuropalliative care: a qualitative study of patient and caregiver perspectives. Palliat. Med. 2021;35(7):1258–1266. doi: 10.1177/02692163211017383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi G., Baldassarre I., Barbaro A., Cavallo N.D., Cropano M., Nappo R., Santangelo G. Mental health status of Italian elderly subjects during and after quarantine for the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Psychogeriatrics. 2021;21(4):540–551. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi G., Baldassarre I., Barbaro A., Cavallo N.D., Cropano M., Nappo R., Santangelo G. Mental health status of Italian elderly subjects during and after quarantine for the COVID‐19 pandemic: a cross‐sectional and longitudinal study. Psychogeriatrics. 2021:12703. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makizako H., Nakai Y., Shiratsuchi D., Akanuma T., Yokoyama K., Matsuzaki-Kihara Y., Yoshida H. Perceived declining physical and cognitive fitness during the COVID-19 state of emergency among community-dwelling Japanese old-old adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2021;21(4):364–369. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manca R., De Marco M., Venneri A. The Impact of COVID-19 infection and enforced prolonged social isolation on neuropsychiatric symptoms in older adults with and without dementia: a review. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.585540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manini A., Brambilla M., Maggiore L., Pomati S., Pantoni L. The impact of lockdown during SARS-CoV-2 outbreak on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Neurol. Sci. 2021;42(3):825–833. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-05035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H.F., Kuo C.A., Huang W.N., Cummings J.L., Hwang T.J. Values of the minimal clinically important difference for the neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire in individuals with dementia. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015;63(7):1448–1452. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Maurik I.S., Bakker E.D., van den Buuse S., Gillissen F., van de Beek M., Lemstra E., Mank A., van den Bosch K.A., van Leeuwenstijn M., Bouwman F.H., Scheltens P., van der Flier W.M. Psychosocial effects of corona measures on patients with dementia, mild cognitive impairment and subjective cognitive decline. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.585686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Clinic, n.d. Mild Cognitive Impairment. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mild-cognitive-impairment/symptoms-causes/syc-20354578 (Accessed 21 November 2022).

- McGrattan A.M., Pakpahan E., Siervo M., Mohan D., Reidpath D.D., Prina M., Allotey P., Zhu Y., Shulin C., Yates J., Paddick S.M., Robinson L., Stephan B.C.M. Risk of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement (N. Y) 2022;8(1) doi: 10.1002/trc2.12267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Coordinating Council, 2015. Cognitive functioning: supporting people with mental health conditions https://www.mhcc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/2016.02.17._supporting_cognitive_functioning-_mhcc_version__v._11__.pdf (Accessed 24 August 2022).

- Mielke M.M. Sex and gender differences in Alzheimer's disease dementia. Psychiatr. 2018;35(11):14–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A.J., Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia--meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009;119(4):252–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musa G., Henríquez F., Muñoz-Neira C., Delgado C., Lillo P., Slachevsky A. Utility of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) in the assessment of a sample of patients with Alzheimer's disease in Chile. Dement Neuropsychol. 2017;11(2):129–136. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642016dn11-020005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council on Aging, 2021. COVID-Driven Isolation Can Be Dangerous for Older Adults. https://www.ncoa.org/article/covid-driven-isolation-can-be-dangerous-for-older-adults (Accessed 24 August 2022).

- Noguchi T., Kubo Y., Hayashi T., Tomiyama N., Ochi A., Hayashi H. Social isolation and self-reported cognitive decline among older adults in Japan: a longitudinal study in the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021;22(7):1352–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.05.015. e1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numbers K., Brodaty H. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021;17(2):69–70. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-00450-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J., Lee H.Y., Khuong Q.L., Markuns J.F., Bullen C., Barrios O.E.A., Hwang S.S., Suh Y.S., McCool J., Kachur S.P., Chan C.C., Kwon S., Kondo N., Hoang V.M., Moon J.R., Rostila M., Norheim O.F., You M., Withers M., Gostin L.O. Mobility restrictions were associated with reductions in COVID-19 incidence early in the pandemic: evidence from a real-time evaluation in 34 countries. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):13717. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92766-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 2021, The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (Accessed 24 August 2022).

- Özgün-Başıbüyük, G., Kaleli, I., Efe, M., Tiryaki, S., Ulusal, F., Demirdaş, F.B., Dere, B., Özgür, Ö., Koç, O., Tufan, İ., 2021. Depression Tendency Caused by Social Isolation: An Assessment on Older Adults in Turkey. 11(3), 298–304.

- Parfenov V.A., Zakharov V.V., Kabaeva A.R., Vakhnina N.V. Subjective cognitive decline as a predictor of future cognitive decline: a systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol. 2020;14(3):248–257. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642020dn14-030007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongan E., Dorey J.-M., Borg C., Getenet J.C., Bachelet R., Lourioux C., Laurent B., Group C., Rey R., Rouch I. COVID-19: association between increase of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia during lockdown and caregivers' poor mental health. J. Alzheimer'S. Dis.: JAD. 2021;80(4):1713–1721. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince Martin, W.A., Guerchet Maëlenn, Claire Ali Gemma 2015. World Alzheimer Report 2015, The Global Impact of Dementia: An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf (Accessed 21 November 2022).

- Rainero I., Bruni A.C., Marra C., Cagnin A., Bonanni L., Cupidi C., Laganà V., Rubino E., Vacca A., Di Lorenzo R., Provero P., Isella V., Vanacore N., Agosta F., Appollonio I., Caffarra P., Bussè C., Sambati R., Quaranta D., Passoni S. The Impact of COVID-19 quarantine on patients with dementia and family caregivers: a nation-wide survey. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.625781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M., 2019. Interpretation of subgroup analyses in systematic reviews: A tutorial. https://cegh.net/article/S2213–3984(18)30099-X/pdf (Accessed 21 November 2022).

- Robb C.E., de Jager C.A., Ahmadi-Abhari S., Giannakopoulou P., Udeh-Momoh C., McKeand J., Price G., Car J., Majeed A., Ward H., Middleton L. Associations of social isolation with anxiety and depression during the early COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of older adults in London, UK. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.591120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson L., Tang E., Taylor J.-P. Dementia: timely diagnosis and early intervention. BMJ. 2015;350:h3029. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson L., Dickinson C., Magklara E., Newton L., Prato L., Bamford C. Proactive approaches to identifying dementia and dementia risk; a qualitative study of public attitudes and preferences. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rongwei Fu, G.G., Mark Grant, Tatyana Shamliyan, Art Sedrakyan, Timothy J. Wilt, Lauren Griffith, Mark Oremus, Parminder Raina, Afisi Ismaila, Pasqualina Santaguida, Joseph Lau, and Thomas A. Trikalinos, 2010. Conducting Quantitative Synthesis When Comparing Medical Interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. In Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK49407/ (Accessed 21 November 2022).

- Sánchez-García M., Rodríguez-Del Rey T., Pérez-Sáez E., Gay-Puente F.J. [Neuropsychiatric symptoms in people living with dementia related to COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Exploratory systematic review] Rev. Neurol. 2022;74(3):83–92. doi: 10.33588/rn.7403.2021356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saragih I.D., Saragih I.S., Batubara S.O., Lin C.J. Dementia as a mortality predictor among older adults with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational study. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021;42(5):1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shon C., Yoon H. Health-economic burden of dementia in South Korea. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):549. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02526-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonetti A., Pais C., Jones M., Cipriani M.C., Janiri D., Monti L., Landi F., Bernabei R., Liperoti R., Sani G. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in elderly with dementia during COVID-19 pandemic: definition, treatment, and future directions. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.579842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen S., Conwell Y. Issues in dementia caregiving: effects on mental and physical health, intervention strategies, and research needs. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2011;19(6):491–496. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31821c0e6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soysal P., Smith L., Trott M., Alexopoulos P., Barbagallo M., Tan S.G., Koyanagi A., Shenkin S., Veronese N. The Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia or mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychogeriatrics. 2022 doi: 10.1111/psyg.12810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalletta G., Porcari D.E., Banaj N., Ciullo V., Palmer K. Effects of COVID-19 infection control measures on appointment cancelation in an Italian outpatient memory clinic. Front. Psychiatry. 2020;11:1335. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.599844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J.A., Gavaghan D., Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Rao W., Li M., Caron G., D'Arcy C., Meng X. Prevalence of loneliness and social isolation among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1017/s1041610222000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]