Abstract

3D in vitro tumor models have recently been investigated as they can recapitulate key features in the tumor microenvironment. Reconstruction of a biomimetic scaffold is critical in these models. However, most current methods focus on modulating local properties, e.g. micro- and nano-scaled topographies, without capturing the global millimeter or intermediate mesoscale features. Here we introduced a method for modulating the collagen I-based extracellular matrix structure by disruption of fibrillogenesis and the gelation process through mechanical agitation. With this method, we generated collagen scaffolds that are thickened and wavy at a larger scale while featuring global softness. Thickened collagen patches were interconnected with loose collagen networks, highly resembling collagen architecture in the tumor stroma. This thickened collagen network promoted tumor cell dissemination. In addition, this novel modified scaffold triggered differences in morphology and migratory behaviors of tumor cells. Altogether, our method for altered collagen architecture paves new ways for studying in detail cell behavior in physiologically relevant biological processes.

Keywords: Wound modeling, Tumor modeling, Breast cancer, Collagen architecture

1. Introduction

Tumors are often described as “wounds that do not heal” [1] since tumorigenesis is tightly associated with chronic tissue damage and repair processes [2]. The hallmarks of cancer highly overlap with those of wound healing [3], both featuring sustained proliferative signaling, cell migration, angiogenesis, immune activation and inflammation and tissue repair with extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [3]. In scar tissue formation, after initial blood clots are formed, there is a rapid recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes, with the onset of inflammation. Meanwhile, activation of myofibroblasts induces wounded tissue contraction and increased ECM deposition and remodeling, followed by re-epithelialization and angiogenesis to restore tissue homeostasis [4]. However, cancer cells harbor high genomic instability and resistance to cell death, which fundamentally differentiate tumor progression from normal wound healing [3,5]. Solid tumors and fibrotic diseases include most of these processes, but in a highly dysregulated and tissue dependent manner. Importantly, pathological ECM remodeling [6,7] is usually implicated in liver carcinoma [8], breast cancer [9], melanoma [10] and lung cancer [11]. The dysregulated ECM signatures are directly associated with poor prognosis and also immunotherapy failure [12].

3D in vitro models have been used to mimic specific aspects of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and study dynamic ECM evolution [13]. Previous work on reconstructing the tumor ECM in vitro has primarily focused on individual local parameters, such as pore size, fiber diameter [14–17], stiffness [18], viscoelasticity [19], collagen alignment [20,21] or microarchitecture [14,22–24]. However, these models usually only include sub-micrometer topographies and mechanics but lack global architectural similitude to in vivo ECM structure. Here, we introduce a new type of thick collagen network that highly mimics in vivo ECM structure, especially similar to human skin scars [25,26]. Different from most previous efforts in modulating collagen structures through buffer condition [15], glycation [18], nanopatterning [27], 3D printing [28], stretching [20], or mixing different gels [29,30], we fabricate a type of thickened collagen network by altering fibrillogenesis during the transient gelation process via mechanical agitation. In vivo fibrillogenesis often involves integrins, fibronectins and tight cellular regulation. Here, our method takes advantage of in vitro fibrillogenesis, which is driven by self-assembly of proteins [31].

By disrupting in vitro fibrillogenesis through mechanical agitation, we created collagen bundles that are thickened and curly, with clustered collagen patches interspersed within a loosely connected collagen network. We refer to this material state as “thick collagen”. This type of collagen imposes less steric restraints. MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells migrated significantly faster in thickened collagen versus normally gelled collagen (generated without applying external mechanical disturbance). MCF10A acini developed protrusive strands in thick collagen. The enhanced migration was not hindered by MMP (matrix metalloproteinase) inhibition. Additionally, this type of collagen is locally dense but globally soft. It provided local spatial heterogeneity (inside the patch versus on the boundary) but global homogeneity (similar size of thick collagen patches and interspacing). Our thick collagen network can be easily prepared and bulk produced (tested up to milliliters scale). It has the potential to be widely applied in in vitro wound, tumor metastasis, and stem cell differentiation related 3D models. It also opens new ways of collagen structure modification and in vivo-like ECM architecture mimicry through mechanical fibrillogenesis disruption.

2. Methods

2.1. Cell culture

Lifeact-eGFP-transduced MDA-MB-231 cell line was a kind gift from the Lauffenburger lab at MIT. It was cultured in DMEM (Gibco™, 11965092) with 10% FBS (Gibco™, 16000-044) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (5,000U/ml, Gibco™ , 15070-063). Normal human lung fibroblasts (ATCC, PCS-201-013) were cultured in Lonza FGM-2 BulletKit (CC-3132) or RPMI1640 (Gibco™ , 11875-093) with 10% FBS and 1% Pen-Strep. Cells were all maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2.

2.2. MCF10A maintenance and acini formation

MCF10As (ATCC, CRL-10317™) were cultured with MCF10A growth medium which includes DMEM/F12 (Gibco™ , 11330-032) supplemented with 5% horse serum (Gibco™, 16050122), 20 ng/ml EGF, 0.5 mg/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma, H-0888), 100 ng/ml cholera toxin (Sigma, C-8052), 10 ug/ml insulin (Sigma, I-1882) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (5,000U/ml, Gibco™ , 15070-063). To produce MCF10A acini, 24-well plates were first coated with a thin layer of pre-thawed Matrigel (Corning, 354230) and then kept in an incubator for 30 minutes to allow Matrigel gelation. Around 5K to 10K MCF10A single cells were then seeded on top of the Matrigel and maintained with MCF10A assay medium in 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 4 days. MCF10A assay medium has the same components as MCF10A growth medium but with 2% normal horse serum and no EGF. MCF10A maintenance and acini formation protocols are adopted from the Brugge lab [32]. Cell recovery solution (Corning, 354253) was used to extract MCF10A acini from Matrigel following manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, MCF10A acini (in Matrigel) were first washed with ice-cold PBS 3 times followed by 1h ice incubation in cell recovery solution. Then MCF10A acini were spun down and washed in ice-cold PBS for 3 times at 70g for 2 minutes in a pre-chilled centrifuge. Washed MCF10A acini were seeded in normal or thick collagen for further study.

2.3. 3D tissue culture in normal collagen

Acid solubilized collagen I (Corning, 354249) was first neutralized with NaOH and then diluted with suspended cells (or acini) to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml or 1 mg/ml (MCF10A study) on ice. Culture media were added after 1h gelation at 37°C. For labeled ECM studies, the initial collagen solution was labeled with Alexa Fluor™ 647 NHS Ester (Succinimidyl Ester) and dialyzed as before [33]. To note, multiwell glass bottom plates used for imaging were pre-coated with polydopamine to anchor the collagen gel [34,35], including thick collagen gels.

2.4. 3D tissue culture in thick collagen

Acid solubilized collagen I (Corning, 354249) was neutralized with 0.5N NaOH in the same way as in normal collagen preparation mentioned above (step 1 in Fig. 1D). Then, the solution was kept at room temperature for around 6.5 to 7.5 minutes (step 2) to allow initial nucleation. In step 3, wide-bore tips were used to gently pipette up and down the collagen while warming up the gel with fingertips. Mixing is stopped when the collagen solution becomes cloudy. The turbidity of the cloudy thick collagen after complete gelation (without adding medium or PBS) for absorbance at 405nm (A405) was assessed to be between 0.4 to 0.5. The cloudy collagen solution can be directly mixed with cells (acini) and aliquoted into polydopamine coated wells followed by 1hr gelation at 37°C. Alternatively, the cloudy collagen solution can be kept on ice for up to 30 minutes before mixing with cells. In this way, the cell mixing step needs to be prolonged accordingly before aliquoting (i.e., the longer the ice incubation, the longer the cell mixing is needed to retain collagen clusters). To note, over-mixing will result in a collapsed (non-cohesive) scaffold. The subsequent steps were followed as per standard 3D tissue culture. In all cell seeding experiments, 2mg/ml thick collagen was used, unless otherwise noted.

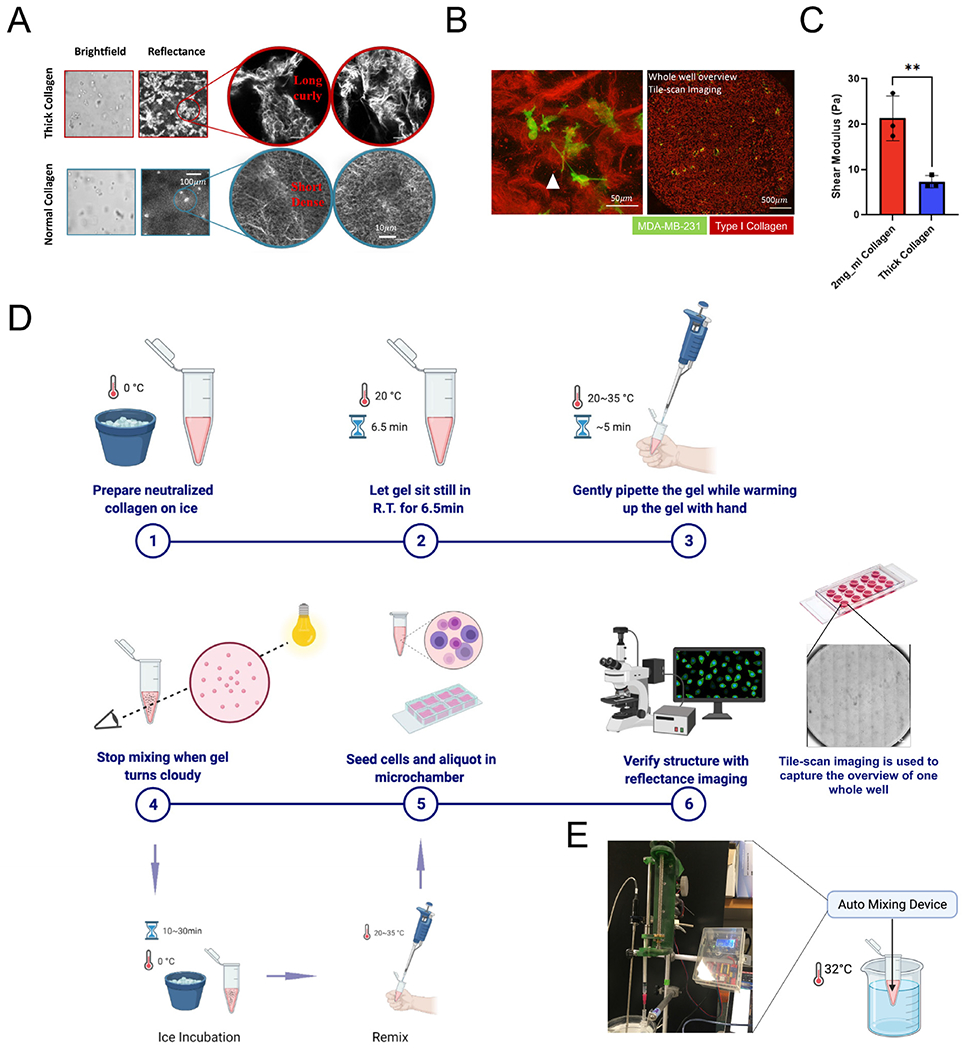

Fig. 1.

Thickened collagen bundles are curly and globally soft. (A) Structural differences of thick collagen bundles versus normal collagen. (B) Local (left) and global (right) view of thick collagen structure. MDA-MB-231 cells (Lifeact-GFP) seeded in thick collagen bundles respond to the local architectural heterogeneity, demonstrating an invasive phenotype. Thick collagen bundles varied locally in length and size but were globally evenly distributed in our gels as seen in a holistic overview from tile scan imaging. Attached polystyrene beads (white arrows) indicated the existence of a network between thick collagen bundles. (C) Thick collagen (2 mg/ml) is globally soft compared with normal collagen (2 mg/ml). Unpaired t-test is performed. * indicates P<0.05, ** indicates P<0.01. (D) Simplified manual step-by-step protocol of creating long and thick collagen via collagen fibrillogenesis intervention. Made with Biorender. (E) We developed a customized homogenization device that can be used to automate the formation of thick collagen networks.

2.5. Migration inhibition drug assay

Drugs were reconstituted and stored following manufacturers’ recommendations and diluted in culture media to working concentrations. Specifically, 20 μM pan-MMPs inhibitor GM6001(Abcam, ab120845), 30 μM ROCK inhibitor Y27632 (Abcam, ab144494), 10 μM Cdc42 inhibitor ML141 (Calbiochem®, 217708), 50 μM formin inhibitor SMIFH2 (Abcam, ab218296), 50 μM ARP2/3 inhibitor CK666 (Abcam, ab141231), 100 μM Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766, 20 μM Rac1 inhibitor EHT1864 (Cayman, 17258) were used. Fresh media mixed with specific drugs were prepared right before the experiment and replaced daily. In the drug assays, at least two independent experiments were performed with at least two replicates (technical duplicates) in each experiment.

2.6. Turbidimetry

The microplate reader was first pre-heated to 37°C. For normal collagen measurement, acid solubilized collagen was neutralized and diluted to 2 mg/ml as above-mentioned. Ice-cold collagen solution was aliquoted into 96-well plates (80μl per well) and A405 was tracked every minute for 20 min. For thick collagen measurement, after step 4 (without ice incubation), the solution was aliquoted into 96-well plates (80μl per well) and readouts of A405 were recorded every minute for 20 min.

2.7. Immunostaining

Culture media were first removed and gels were rinsed 3 times gently with PBS. Cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 min and permeabilized by 0.3% Triton X-100 for another 30 min. After fixation and permeabilization, cells were blocked with 1% BSA followed by primary antibody incubation (1:200), 3X PBS wash and secondary antibody incubation (1:500), supplemented by Hoechst stain (1:2000) and Alexa Fluor™ 647 Phalloidin (Invitrogen™, A22287, 1:200). Fluorescence imaging was acquired within one week after immunostaining.

2.8. Confocal microscopy

Imaging was performed with a Leica SP8 laser scanning confocal microscope. Time-lapse imaging (XYZT mode) was taken with a 20X objective (0.75 NA), with time interval set to 3 or 6 min, and z-step size set to 2 μm. Day 0 time-lapse imaging was acquired between around 0h to 12h post-embedding cells into gels. Day 1 time-lapse imaging was acquired between around 24h to 36h post-embedding. Overview tile scan images were taken on days 1, 2 or 5.

2.9. Image analysis

To track cell migration, XYZT data were first reduced in dimensions by conducting standard deviation (SD) projection along the z axis. The XYT data were then processed by TrackMate in Fiji to produce cell trajectories. Trajectories were exported to MATLAB to calculate average speed and mean squared displacement (MSD). Average speed specifically refers to the mean of the absolute value of the net displacement of the cell center per hour. Mean squared displacements were computed with the following equation [36]:

In this equation, N is the total step number, n is the n-th step, x,y are the x,y coordinates respectively. For morphology analysis, z-projected tile scan images were segmented and analyzed by in-house MATLAB codes. Segmentation performance was validated and curated, with manual correction. For difficult automated segmentation data, such as the Y27632-treated condition, manually tracked data were supplemented. The definitions of elongation, compactness, sphericity and shape variance were described in SI Fig. 4B. Morphology and migration tracking was performed as previously described [37].

A custom ImageJ script was used to derive the colocalization of the YAP/TAZ signal in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Specifically, the central plane of each cell is first extracted. DAPI and YAP/TAZ channels are then used to produce masks for cell nucleus and cell body, respectively. Nuclear YAP/TAZ is calculated by averaging YAP/TAZ intensity within the nucleus mask and cytoplasmic YAP/TAZ is calculated by averaging YAP/TAZ intensity within the cell body, outside the nucleus mask. To note, only YAP/TAZ of the focal plane is used for the average calculation. For thick collagen bundle size measurement, “Analyze Particle” function from Fiji was used.

2.10. Rheometry

An Anton Parr Shear Stress Rheometer (502 WESP) was used for mechanical characterization of collagen gels with the 25-mm parallel-plate geometry and a 500μm gap. A no. 1 25-mm cover glass (VWR) was used for the top plate and a 40 mm cover glass (Fisherbrand) as the bottom plate. To prevent slip between the gel and the plate, both plates were chemically treated with polydopamine and attached to each plate of the rheometer with double-sided tape (3M 666). The rheometer was then zeroed and calibrated. The temperature of the system is preset and maintained at 37°C. Collagen was deposited onto the bottom plate of the rheometer immediately before gelation, and the top plate was lowered rapidly so that the gel formed a uniform disk between the two plates. Approximately 350 μL collagen was pipetted onto the rheometer, the gap was set to 500μm, and the sample was kept in a custom made humidity chamber to prevent evaporation. After at least 60 min of gelation, gels were immersed in PBS and allowed to sit for at least 15 min before taking measurements. Then, the shear modulus was measured at 2% strain and at 0.1Hz. The shear modulus was determined and analyzed using custom Python scripts. Frequency sweeps were carried out at 2% strain.

2.11. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The collagen sample was placed in 4% PFA for 1h at room temperature, and then washed twice in PBS for 10 min each, and twice in ddH2O for 10 min as well. Then, the samples were gradually dehydrated through sequential ethanol (EtOH) washes (30%, 50%, 66% in H2O and 100% EtOH), for 10 min each. Samples were processed through a graded hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) sequential wash (30%, 50%, 66% in EtOH, and 100% HMDS), for 10 min each. Samples were then placed on aluminum foil and allowed to dry in the fume hood overnight. After that, the samples were mounted on a support with carbon tape and covered with a 8 nm layer of iridium with a sputter coater. The samples were then imaged with a scanning electron microscope.

2.12. Automatic collagen mixer

In order to further validate the replicability of the unique Collagen I architecture, a computer-controlled extruder was designed and constructed. Conventional off the shelf syringe pumps offer the accuracy required for this application. However, they tend to be heavy, bulky, and costly, and few offer the option of running custom pumping sequences without bypassing the whole controller board and connecting directly to the motor. It was therefore decided that to achieve the desired pumping in/out cycle, the best option would be to design a linear actuator that could operate any syringe and would be light enough to attach to a scaffold over the hot plate. The main components of the actuator are: a 3D-printed frame, a Nema 17 stepper motor, a A4988 stepper driver, a set of 20T/60T GT2 gears, a T8 2mm pitch lead screw, and an Arduino Uno microcontroller. The complete structure was printed in 11h using an Elegoo Saturn resin printer. The Arduino IDE was used to program and upload the code on the board. Using the known gear ratios and rotational-to-linear motion conversion of the lead screw, we adjusted the speed of the stepper motor to obtain the desired flow rates.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Most sampling and statistical analyses of result plots are indicated in their corresponding figure caption. For shear modulus, unpaired t-test is performed. For statistical comparisons in drug studies, one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD test was performed. *p-value<0.05; **p-value<0.01; *** p-value<0.001; ****p-value<0.0001. # indicates current condition is significantly different (p<0.05) with every other condition, unless otherwise annotated.

3. Results

3.1. Thickened collagen bundles are curly and globally soft

Thickened collagen bundles were long and curly in appearance, when compared with short, dense collagen networks gels prepared without mechanical disturbance, i.e. normal collagen, as shown in Fig. 1A. Collagen bundles imposed limited physical restraints, as both 3D collagen networks supported cell growth and provided a good mechanical scaffold. As for its detailed structure, thickened collagen patches were interconnected by thin collagen fibers, which were not clearly seen in reflectance imaging, but attached polystyrene beads indicated the existence of this loose network (Fig. 1B, left). Thick collagen patches varied in size, orientation, and micro-structure, providing local spatial heterogeneity for individual cells, but these patches were relatively uniformly distributed and separated by the loose collagen network (Fig. 1B, right). In addition, bulk rheometry revealed that thick collagen bundle gels are globally softer than normal collagen gels (Fig. 1C). Frequency sweeps revealed viscoelastic behavior in thick collagen gels, similar to that of normal collagen gels, but with slightly higher frequency dependent behavior (SI Fig. 1A, right). The generation of thickened collagen bundles did not require complex equipment. The overall process took 20 minutes to be completed and was reproducible. In manual fabrication (Fig. 1D), neutralized ice-cold collagen was first kept at room temperature for 6.5 minutes, then warmed up by fingertips while being stirred gently by a wide-bore pipette tip until turbidity reached between 0.4-0.5 (SI Fig. 1A, left). Similar thick collagen bundles structures were obtained between independent experiments, although a certain degree of variability can be seen (SI Fig. 1E, top row). To standardize the procedure, we also developed an automated homogenization device and adapted our protocol accordingly (Fig. 1E). With this device, thick collagen bundles were generated by mixing while heating ice-cold collagen gel at 32°C for 4min~5min. Reproducibility for both manual and automated fabrication is demonstrated in SI Fig. 1E.

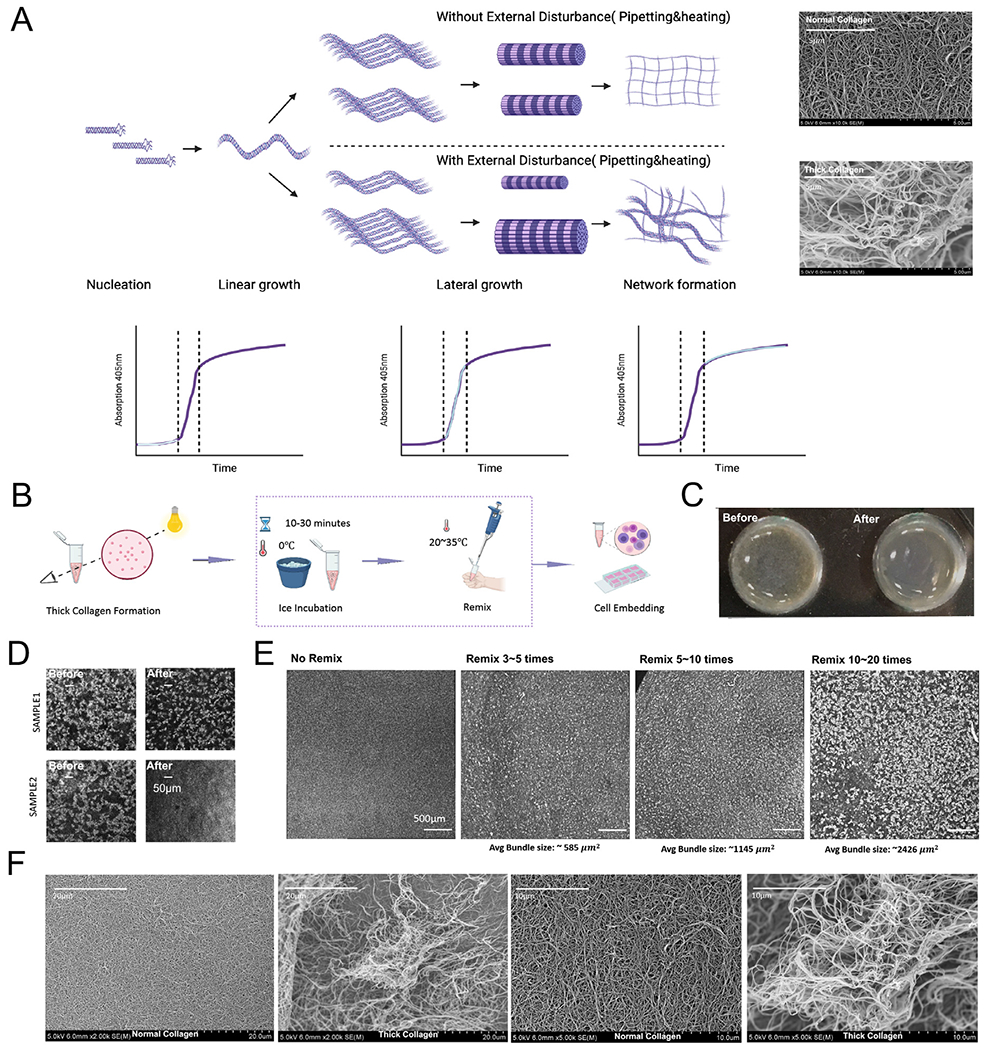

3.2. Thickened collagen structure can be tuned by temperature and mixing

Previous studies have focused on the dynamics of fibrillar gel formation. The steps proposed for in vitro fibrillogenesis, portrayed in Fig. 2A, are nucleation, linear growth and lateral growth [38–40]. The thickening of fibrils has often been reflected in the lag phase of the typical turbidity curve [17,39]. However, it has been suggested that the growth of visible particle-like structure is associated with the transition phase in the turbidity curve [41]. Also, collagen precipitation can dissolve upon pH [42] or temperature change [39,43], and this temperature-associated fibril instability may be governed by entropy [43]. In this line, temperature tuning during fibrillogenesis has been used to control collagen pore size [17]. Indeed, clusters in our thick collagen structures were not thermally stable and may disassemble upon ice incubation (Fig. 2B–C, SI Fig. 1B–D). In addition to temperature, we noticed that frequency and strength of remixing between step 4 and step 5, as annotated in Fig. 2B, are critical for tuning the average size of collagen patches. Of note, the size of the final collagen patches was dependent on the degree of mixing (Fig. 2D–E). However, over-mixing often resulted in an ultra-fragile collagen network that collapsed upon PBS addition (data not shown). The introduction of mechanical disturbance may be causing an uneven aggregation in gelation cores of collagen fibrils during lateral growth stage. For this, heating while mixing in the lateral growth stage may favor a more homogeneous distribution of these early gelation cores. Furthermore, 37°C incubation propagated the early heterogeneity and resulted in thick collagen networks. As shown in Fig. 2F, SEM images of 2 mg/ml normal collagen and 2 mg/ml thick collagen were consistent with above-mentioned observations with confocal reflectance imaging (Fig. 1A–B). Normal collagen is a network with dense and small pores, while thick collagen patches consist of long entangled and tortuous fibers. Interestingly, our thick collagen seemed to highly mimic the architecture of collagen from human scars (SI Fig. 2A–B). Overall, with our system, different fibrillar collagen gel patterns can be created by modulating collagen concentration, temperature, and mixing (SI Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Thickened collagen structure can be tuned by temperature and mixing. (A) Schematic diagram demonstrates hypothetically how external disturbance in the collagen lateral growth stage triggers the formation of thick collagen bundles. Made with Biorender.com. (B) After thick collagen bundles are formed, ice incubation and remix before gelation (indicated in the dotted square) can be tuned to modulate architecture of the thick collagen scaffold. (C) After thick collagen is formed, ice incubation decreases the overall granularity of the thick collagen system. More data can be seen in SI Fig. 1B. (D) Reflectance imaging showed that ice incubation between step 4 and step 5 (before complete gelation at 37°C) reduced the size of collagen bundles. More data and binarized images can be seen in SI Fig. 1C–D. See Fig. 2C for step 4 and step 5 description. (E) The frequency and strength applied in mixing thick collagen bundles before step 5 controlled the size of collagen bundles. (F) Scanning electron microscope images of normal collagen versus thick collagen bundles. Normal collagen consisted of dense networks and small pores while thick collagen patches had long tortuous collagen bundles and less physical restraints. Red arrows indicate the boundary of a possible collagen patch.

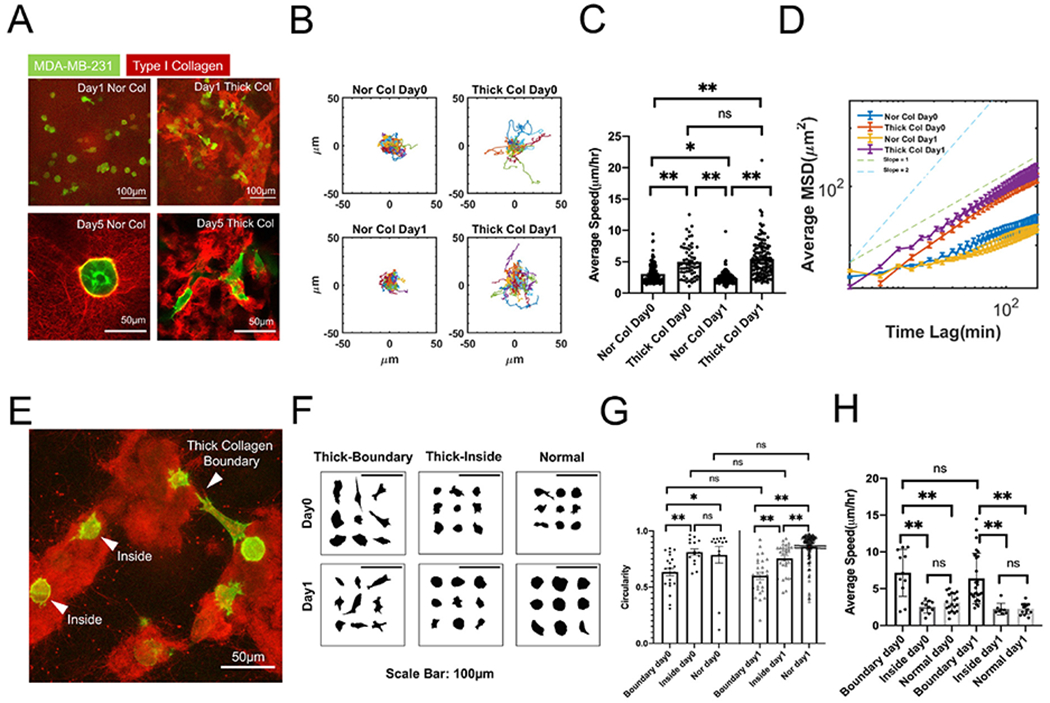

3.3. MDA-MB-231 cells located on the boundary of thick collagen patches are more migratory

To test the impact of thick collagen on cell behavior, we seeded MDA-MB-231 cells in our gels. MDA-MB-231 is a triple-negative basal type breast cancer cell line. It is highly aggressive and metastatic, featuring low-claudin (reduced cell-cell contact) and overexpression of ECM components and remodeling-related proteases, mesenchymal associated markers, and tumor favoring signals [44]. In in vitro 3D models, MDA-MB-231 cells are highly sensitive to collagen alignment [45,46], stiffness [38,47], and steric hindrance, such as pore size [16,47,48]. In vivo, MDA-MB-231 tumors preferentially metastasize to the bones, brain, and lungs [49–51].

Our thick collagen system was characterized by reduced physical hindrance, global softness, and local thickened fiber bundles. When embedded in our thick collagen gels, MDA-MB-231 cells responded rapidly during the first 24h. In long term culture (up to day 5), MDA-MB-231 cells in normal collagen mostly grew into spherical cell clusters whereas the ones seeded in thick collagen remained isolated and rarely clustered (Fig. 3A, SI Fig. 3A). This observation can be further supported by our overview of the tile scan imaging (SI Fig. 8A and SI Fig. 8B). Overall, when in thick collagen, MDA-MB-231 cells demonstrated higher local dissemination (Fig. 3B), average speed (Fig. 3C, SI Fig. 3C), and persistence (as shown by the MSD and its logarithmic slope) (Fig. 3D) compared with cells in normal collagen on day 0 and day 1 (SI Video 1A). In addition, MDA-MB-231 cells often demonstrated two distinct morphological phenotypes depending on the position of cells in the thick collagen patches (SI Video 1B, Fig. 3E, SI Fig. 3B). MDA-MB-231 cells perching on the boundary of thick collagen bundles were often highly stretched, spindle-like, and protruding towards nearby collagen patches (Fig. 3E, SI Fig. 3B, left). MDA-MB-231 cells located in the center of a thick collagen patch were more spherical, similar to cells in normal collagen (Fig. 3F–G). Consistent with morphological differences, MDA-MB-231 cells on the boundary displayed higher migration speed than cells in the middle of thick collagen patches (Fig. 3H).

Fig. 3.

MDA-MB-231s located on the boundary of thick collagen patches are more migratory. (A) MDA-MB-231 (Lifeact-GFP) cells seeded in normal type I collagen (Nor Col) versus thick collagen (Thick Col). MDA-MB-231 cells seeded in thickened collagen bundles did not form cell clusters and maintained an invasive phenotype throughout the culture period. Images from the top row are Z-projected images in which collagen structures are overlaid. Bottom row demonstrates one slice without projection. (B) MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) seeded in thick collagen (Thick Col) bundles migrated more actively than normal collagen (Nor Col) on day0 and day1. (C) Average speed of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) between normal versus thick collagen on day0 and day1. (D) Average mean squared displacement of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) between normal versus thick collagen on day0 and day1. (E) Representative image demonstrated the distinct behavior of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) along gel boundary versus trapped in the middle of the thick collagen. The beads trapped between the gel patches indicated the existence of loose connecting fiber. (F) Summarized morphology of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) in different conditions. Thick-Boundary: on the boundary of thickened collagen patch; Thick-Inside: in the middle of thickened collagen patch; Normal: normal collagen. (G) Circularity of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) located on the boundary versus cells found trapped in the middle of gel. (H) Average speed of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) located on the boundary versus cells found trapped in the middle of gel. All data are collected from at least 3 independent experiments with at least 2 replicates in each experiment. One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD test was performed. * indicates p-values<0.05. ** indicates p-value<0.01.

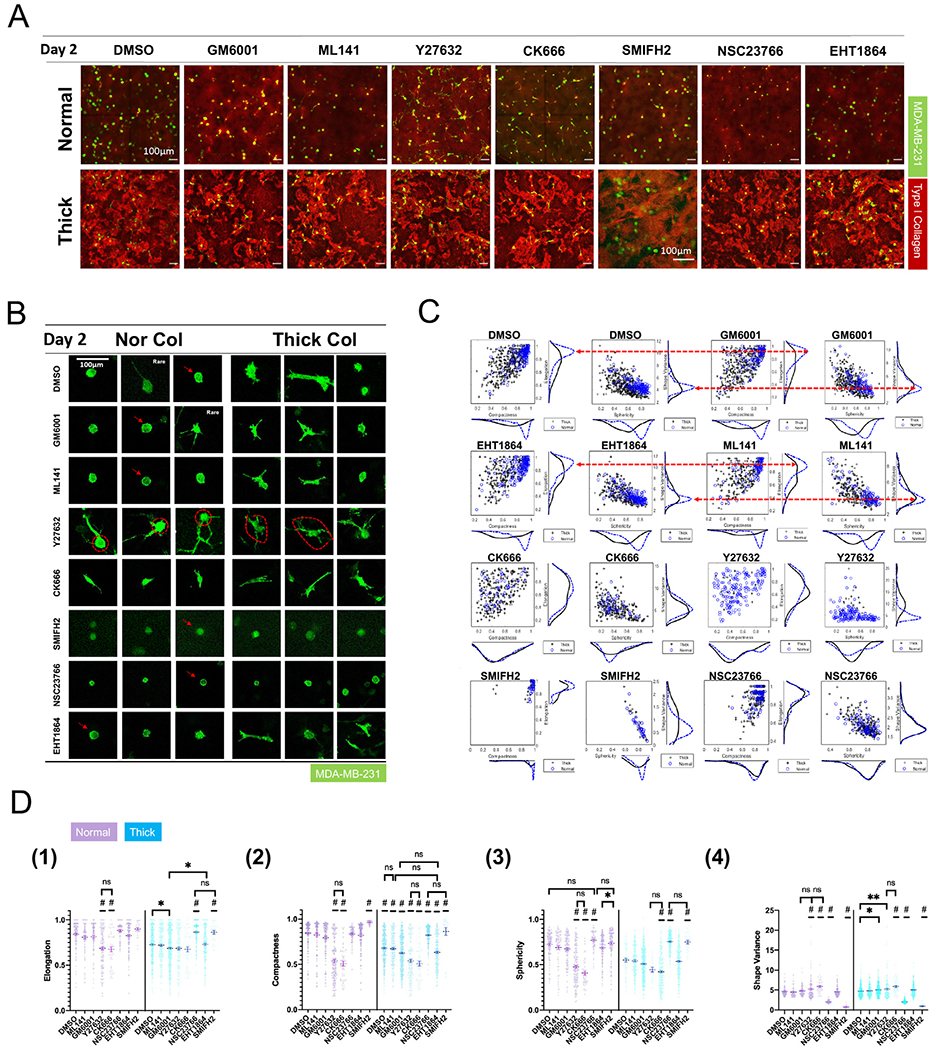

3.4. Drug treatment triggers distinct cell morphologies in thick collagen versus normal collagen

Persistent cell migration in a 3D environment requires protrusive structures and actomyosin-mediated contractility [52]. The branching and elongation of protrusive structures often involves ARP2/3 and formin-nucleated actin polymerization [53,54], whereas Rho-ROCK signaling is at the center of actomyosin-mediated cell contractility [55]. The Rho GTPases Rho, Rac and Cdc42 are major players in cytoskeletal regulation [56]. In 3D ECMs, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) contribute to matrix degradation and remodeling, which facilitate cell migration [48,57]. To investigate the specific molecular mechanism behind the elevated migration of MDA-MB-231 cells in thick collagen, we tested the following drugs in our gels: pan-MMP inhibitor GM6001 (20 μM), potent selective Cdc42 inhibitor ML141 (10 μM), ROCK inhibitor Y27632 (30 μM), ARP2/3 inhibitor CK666 (50 μM), formin inhibitor SMIFH2 (50 μM) and Rac1 inhibitors NSC23766 (100 μM) and EHT1864 (20 μM). We first traced and quantified cell morphology. GM6001, ML141, and EHT1864 treatments resulted in similar morphology patterns compared with DMSO control in normal collagen. In thick collagen, GM6001, ML141, and EHT1864 treatments also showed similar morphology but different from the morphology observed in normal collagen conditions (Fig. 4A, B, and SI Fig. 4A). These findings suggested that cell morphology was not governed by these drug targets, but was rather still more strongly influenced by the collagen architecture. On the other hand, Y27632, CK666, SMIFH2, and NSC23766 treated cells demonstrated distinct morphologies compared with control. Under the same drug treatment, MDA-MB-231 cells displayed similar morphology in normal collagen and thick collagen. This suggested that the driving force in these conditions was the drug treatment instead of collagen architecture. The graphic illustration of each morphological index can be found in S1 Fig. 4B. Normalized sphericity is shown in S1 Fig. 4C, and image segmentation performance is demonstrated in SI Fig. 4D.

Fig. 4.

Drug treatment triggers different cell morphology patterns in thick collagen versus normal collagen. (A) Morphology of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) under drug treatment on day2. (B) Summarized morphology of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) under drug treatment on day2. SMIFH2 treated MDA-MB-231s do not demonstrate F-actin accumulation along cell boundaries (indicated by white arrow) compared with MDA-MB-231s under DMSO, GM6001, ML141, NSC23766, and EHT1864 treatment (indicated by red arrows). Red dotted circles demonstrate visual difference of MDA-MB-231 cell bodies in normal and thick collagen under Y27632 treatment. (C) MDA-MB-231 (Lifeact-GFP) population distribution when projected on the axis of elongation index, compactness index, shape variance, and sphericity. See the definition and calculation of these four indices in the materials and methods section and SI Fig. 4B. Red arrows indicate that the morphology response from the MDA-MB-231 population was similar under different drug treatments. (D) Morphology index of each condition in normal (purple) and thick collagen (blue). All data are collected from at least 2 independent experiments with at least 2 replicates in each experiment. One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD test was performed for each collagen condition (thick or normal) separately. * indicates p-values<0.05. ** indicates p - value<0.01. “#”indicates that the condition is significantly different from all other conditions on that day, unless otherwise annotated.

Notably, each of the observed patterns is directly linked with the cell function affected by the inhibitor. Y27632 is a potent and selective ROCK inhibitor. ROCK mediates actomyosin-based cell contractility via regulating retrograde flow of actin monomers from protruding structures [58]. Inhibition of ROCK in our cultures led to extremely long cell protrusions, as shown in Fig. 4B. Interestingly, cells in normal collagen were usually round whereas cells in thick collagen were slightly elliptical, as indicated by the round/elliptical dotted circle in Fig. 4B. This suggested that the alignment of the cell body in response to collagen architecture may not be entirely abolished with ROCK inhibition.

Nucleation inhibitors triggered distinct morphologies in our collagen cultures. CK666 inhibits ARP2/3 whereas SMIFH2 inhibits formins. ARP2/3 often initializes actin fiber branching and is closely associated with lamellipodia. Upon ARP2/3 inhibition, MDA-MB-231 cells, in both normal collagen and thick collagen, were elongated and stretched. This suggested that, in the absence of ARP2/3, formin-driven actin networks may be disrupted and may lead to the elongation of the cell body. However, SMIFH2 treated cells were round and lacked cell peripheral fluctuations (indicated by red arrows on Fig. 4B). This suggested that formins may play a predominant role in cell migration in 3D collagen. NSC23766 shows similar effects as SMIFH2 (Fig. 4B). However, NSC23766-treated cells were smaller than most other drug conditions. This may be linked to NSC23766-induced proliferation arrest, as previously shown in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells [59]. In addition, SMIFH2-treated cells lacked F-actin accumulation at the cell periphery, clearly visible in NSC23766-treated cells (Fig. 4B, red arrows). NSC23766 and EHT1864 were both Rac1 inhibitors but generated distinct morphological responses in MDA-MB-231 cells in our experiments.

Further quantification of MDA-MB-231 cell morpholog agreed with representative images (Fig. 4C–D). In conditions governed by collagen architecture, namely GM6001/ML141/EHT1864/DMSO, the cell population demonstrated almost identical distributions as shown in histograms of each morphology index (Fig. 4C, red dotted arrows).

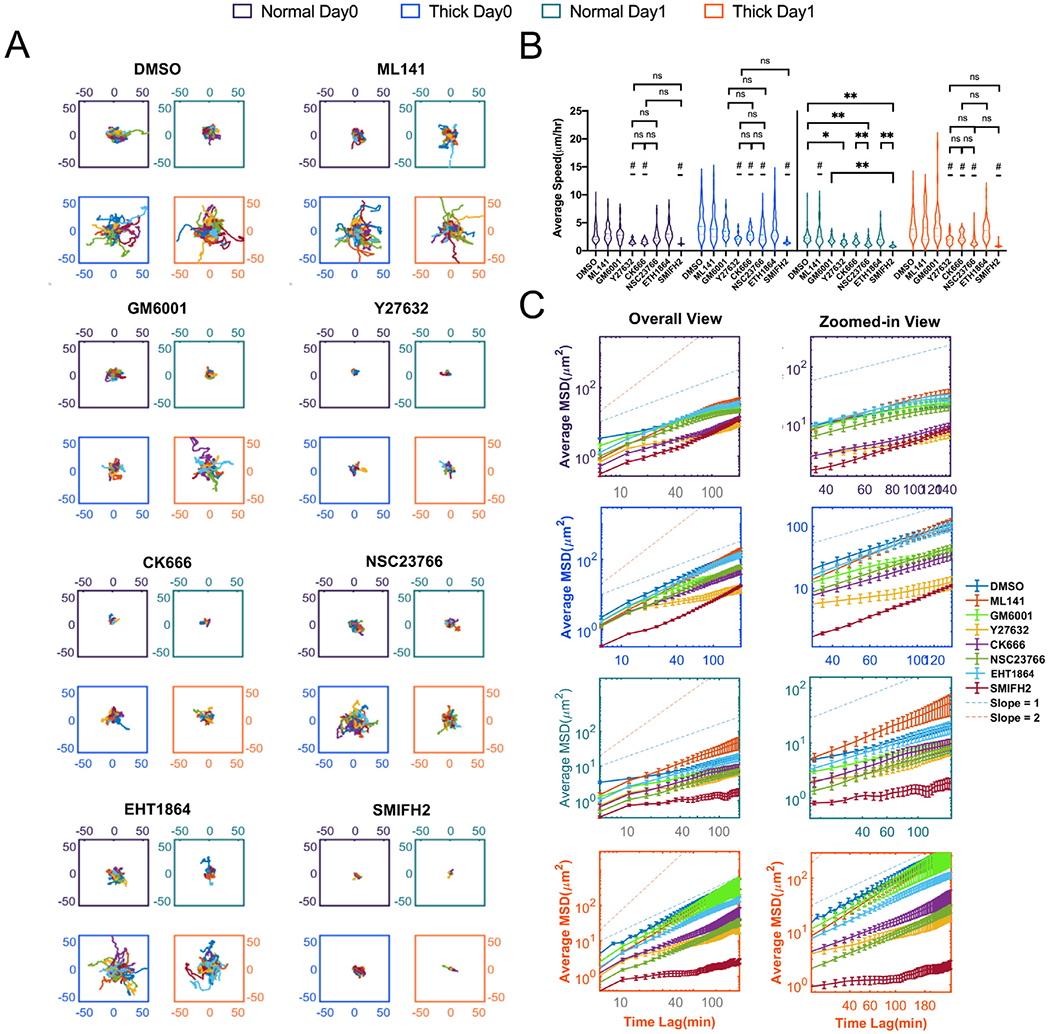

3.5. Fast migration of MDA-MB-231 cells in thick collagen requires contractility and protrusions but not MMPs

Apart from morphology signatures, we also tracked cell migration (Fig. 5A–C, SI Fig. 5A–B, and SI Video 2A). First, GM6001 treatment failed to inhibit MDA-MB-231 cell migration. GM6001-treated MDA-MB-231 cells in thick collagen migrated as actively as the DMSO control, both increased compared to cells in normal collagen. This suggested that migration of tumor cells in thick collagen was MMP-independent. We also noticed that Y27632, NSC23766, and SMIFH2 significantly reduced MDA-MB-231 cell migration. This suggested that actomyosin-based contractility by RhoA/ROCK and formin-based actin nucleation were required for cell migration in thick collagen. However, the interpretation of NSC23766 was confounded by the poor performance of another Rac1 inhibitor ML141. NSC23766 binds directly to Rac1 and blocks the interaction between GEF Trio or Tiam [60]. EHT1864 binds to Rac1 but it is an allosteric inhibitor for guanine association. EHT1864 can inhibit PDGF-induced lamellipodia formation, but lysophosphatidic acid or bradykinin can still trigger cytoskeletal re-arrangement through RhoA and Cdc42 respectively [61]. This suggested that the thick collagen architecture may override the effect of EHT1864. On the other hand, ML141, one of the Cdc42 inhibitors, did not show significant inhibition. It has been shown that human pancreatic cancer cells PANC-1 moved faster in aligned matrix fiber regardless of ML141 treatment, whereas NSC23766 inhibited cell movement, regardless of collagen fiber orientation [62], which correlates with our findings. Interestingly, while ML141 does not inhibit migration of MDA-MB-231 cells or pancreatic cancer cells, in 2D conditions it does inhibit ovarian cancer cell lines such as OVCA429 or SKOV3ip, in a dose-dependent manner. The differential preference between MDA-MB-231 cells for a stiff substrate and metastatic ovarian cancer cells (MOCC) for compliant substrate for migration [63,64] may be dictated by Rac1 and ML141, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Fast migration of MDA-MB-231s in thick collagen requires cell contractility and protrusions but not MMPs. (A) Overlaid trajectories of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) in thick collagen versus normal collagen on day0 and day1. “#”indicates that condition is significantly different from all other conditions, unless otherwise annotated on that day. One-way ANOVA with Turkey post-hoc analysis was performed within each day of each collagen condition. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01. (B) Average speed of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) in thick collagen versus normal collagen on day0 and day1. (C) Average mean squared displacements of MDA-MB-231s (Lifeact-GFP) in thick collagen versus normal collagen on day0 and day1. Error bar is in SEM. All data are collected from at least 2 independent experiments with at least 2 replicates in each experiment.

To conclude, our drug assays together indicate that for highly metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells to migrate in thick collagen, ROCK mediated cell contractility is at the center of tumor cell dissemination. In addition, the role of formins, based on SMIFH2 studies, needs to be explored further, since SMIFH2 has been recently reported to have off-target effects on several non-muscle myosins [65].

3.6. Non-metastatic MCF10A cells acquire protrusive phenotype in thick collagen

In contrast to the MDA-MB-231 cell line, MCF10A is an immortalized non-cancerous breast epithelial cell line. MCF10A cells lack the potential to form tumors and metastasize in nude mice [66]. When cultured in 3D reconstituted basement membrane gels, MCF10A cells developed into acinar structures that recapitulated many features of normal breast epithelial cells.

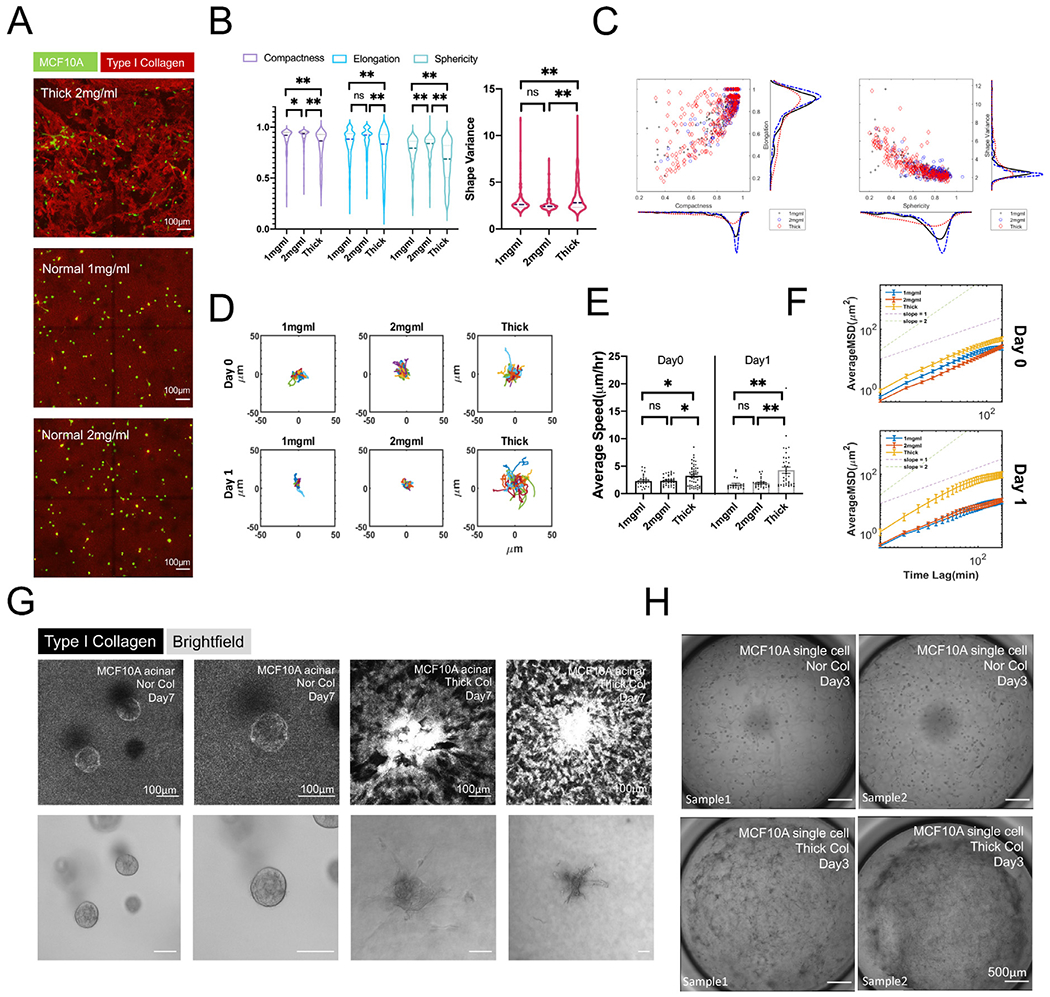

We first observed that thick collagen induced different responses from MCF10A single cells compared with both 1 mg/ml or 2 mg/ml normal collagen, but not as dramatic as seen in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 6A, SI Video 1C). A higher number of MCF10A cells in thick collagen were elongated and less spherical and compact, acquiring a mesenchymal-like morphology (Fig. 6B). We observed a contrast with the irregular protrusion patterns of MDA-MB-231 cells induced by thick collagen architecture, as indicated by the shape distribution in Figs. 1B, 3E–F and 4B DMSO condition. MCF10A single cells only transitioned from round to more elliptical without producing any small finger-like protrusions, as indicated in Fig. 6B and C. Also, MCF10A cells were sensitive to thick collagen architecture and influenced by collagen density (Fig. 6C). Consistent with the morphological transition, MCF10A cells had increased migration in thick collagen, as shown in Fig. 6D and SI Fig. 6D. MCF10A cells migrated significantly faster (Fig. 6E, SI Fig. 6A) and more persistently (Fig. 6F) in thick collagen than 1 mg/ml or 2 mg/ml normal collagen.

Fig. 6.

Non-metastatic MCF10As acquire protrusive phenotypes in thick collagen. (A) Projected confocal imaging of MCF10As in 2 mg/ml thick collagen, 1 mg/ml and 2 mg/ml normal collagen. (B) Compactness, elongation, sphericity, and shape variance index of MCF10As in different conditions. All data were collected from at least 2 repeated experiments with 2 replicates in each experiment. One-way ANOVA with Turkey post-hoc analysis was performed within each morphology index. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01. (C) MCF10A cell population distribution was projected on the axis of elongation, compactness, shape variance, and sphericity. (D) Overlaid migration trajectories of MCF10As on day0 and day1. (E) Average speed of MCF10As on day0 and day1. One-way ANOVA with Turkey post-hoc analysis was performed within each day. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01. (F) Average mean squared displacements of MCF10As on day0 and day1. (G) Day4 old MCF10A acini in normal versus thick collagen on day7 (3 days after collagen embedding). Nor Col: Normal collagen. Thick Col: Thick collagen. Reflectance images demonstrated collagen remodeling as a result of MCF10A acini contraction. (H) MCF10A single cell seeded in normal collagen (Nor Col) developed into round or extended cell clusters on day3. MCF10As seeded in thick collagen (Thick Col) demonstrated an invasive phenotype, and almost no round cell clusters were observed. In addition, global contraction of thick collagen networks occurred.

Thick collagen also triggered morphological changes of MCF10A acini. Protrusive branches appeared from the acini and pulled the collagen patches nearby substantially (Fig. 6G). MCF10A acini seeded in normal collagen showed little of these collagen-pulling events. Additional data can be seen at SI Fig. 6B. It has been previously documented that MCF10A acini generate protrusive cell strands in response to mechanical forces [67]. The collagen-pulling was not limited to MCF10A acini but also observed in single cells. In our overview tile scan imaging (Fig. 6H), morphological changes were universal and occurred across the entire well, accompanying the collapse and detachment of the thick collagen bundles from the vertical wall of culture wells. Additional data can be seen at SI Fig. 6C.

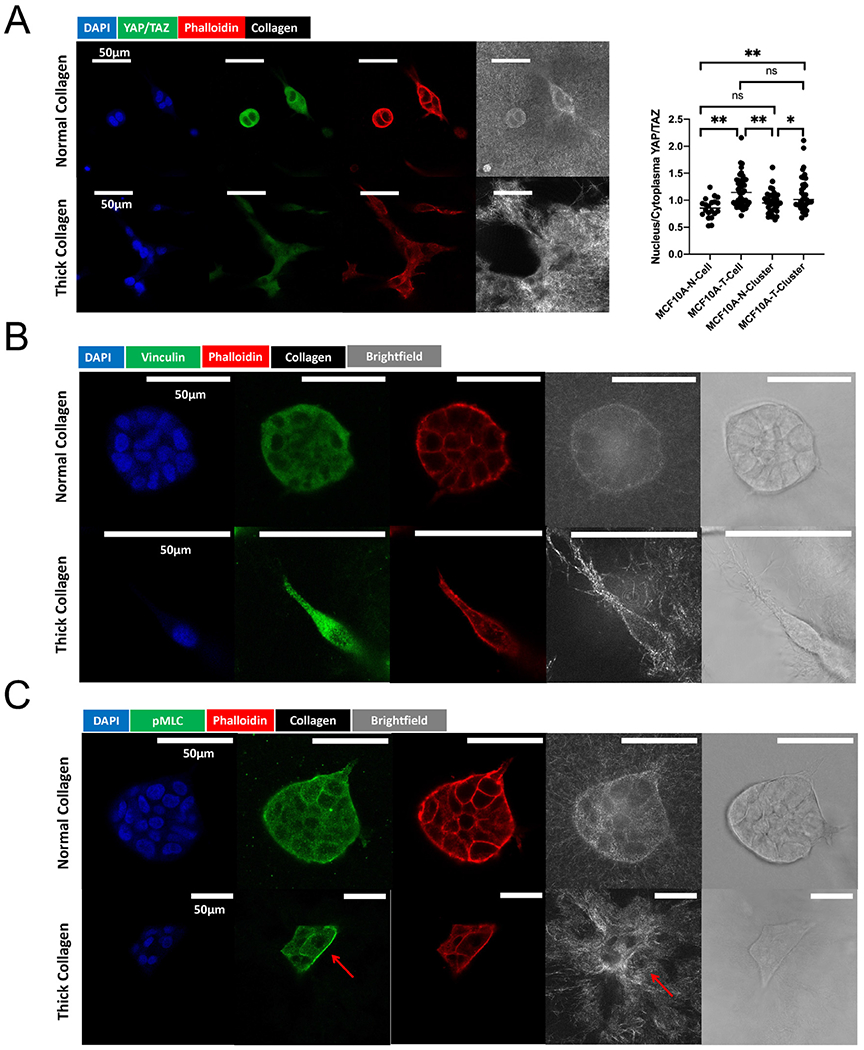

3.7. Molecular profiles induced by thick collagen in MCF10A cells

To investigate the molecular signatures induced by thick collagen in MCF10A cells, we collected immunofluorescence imaging of YAP/TAZ, vinculin, and phosphorylated myosin light chain (pMLC). YAP/TAZ is a sensitive mechanosensor, and its relative nuclear/cytoplasmic distribution is regulated by substrate rigidity [68]. YAP/TAZ accumulates in the nucleus when a cell stretches out on a substrate of high rigidity but localizes in the cytoplasm when cells are in confinement or interacting with softer substrates. As MCF10A cells often clustered in collagen after three days after gel embedding, we separated MCF10A clusters from MCF10A single cells in YAP/TAZ measurement. Our YAP/TAZ quantification revealed that both MCF10A single cells and MCF10A clusters had a higher nucleus/cytoplasm ratio in thick collagen versus normal collagen (Fig. 7A, SI Fig. 7A–B). This was consistent with our previous observation of highly stretched MCF10A clusters in thick collagen. Thick collagen architecture triggered stretching and elongation of MCF10A cells and redistribution of YAP/TAZ. Vinculin is a molecular marker for both intercellular and cell-ECM adhesions [69]. In the protrusive strands from MCF10A cell clusters, vinculin (Fig. 7B, SI Fig. 7C) colocalized with strained collagen bundles. This suggested that the collagen pulling observed in Fig. 6G and 6H may be linked to protrusive structures with strong adhesions. pMLC is a direct marker for actomyosin based contractility. Data in both Fig. 7C and SI Fig. 7D demonstrated that, in thick collagen where large gel patch contraction happens, increased pMLC can be observed. This indicated that the collagen-pulling observed in Fig. 6G and H was linked to cell contractility.

Fig. 7.

Molecular profiles induced by thick collagen in MCF10As. (A) YAP/TAZ localization in MCF10A single cell and clusters on day 4. “MCF10A-N-Cell” indicates single MCF10As identified and measured in 2 mg/ml normal collagen. “MCF10A-T-Cell” indicated single MCF10As identified and measured in 2 mg/ml thick collagen. “MCF10A-N-Cluster” indicated MCF10A clusters (consisting of more than 2 nuclei) identified and measured in 2 mg/ml normal collagen. “MCF10A-T-Cluster” indicated MCF10A clusters (consisting of more than 2 nuclei) identified and measured in 2 mg/ml thick collagen. YAP/TAZ data were collected from 2 independent experiments with at least 3 replicates in each experiment. One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analysis was performed. * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of vinculin in normal versus thick collagen. The red arrow indicates the colocalization of vinculin and collagen pulling. (C) pMLC staining in normal versus thick collagen. The red arrow indicates the colocalization of pMLC with the collagen pulling (alignment).

4. Discussion

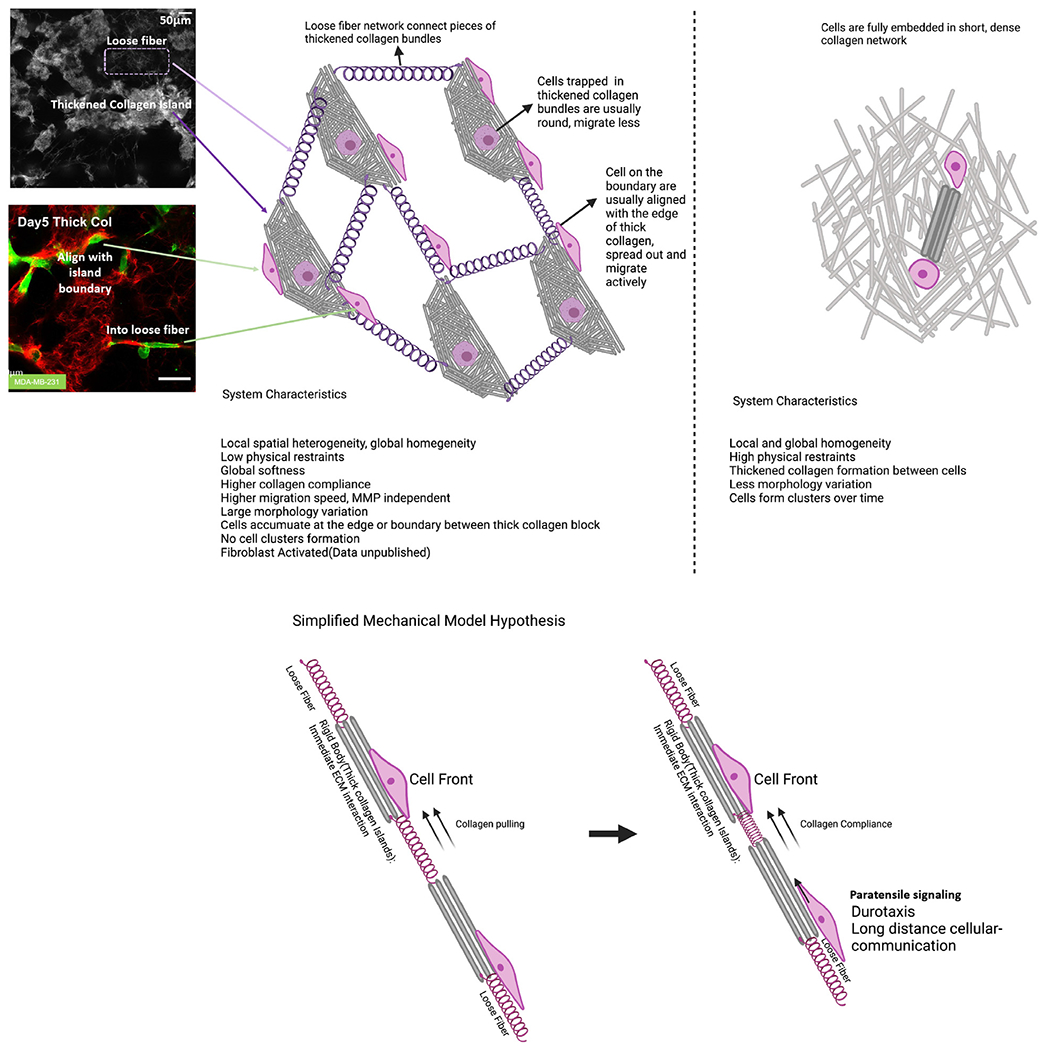

In this work we introduced a fast and reproducible method to modulate collagen architecture and created a type of collagen scaffold highly similar to in vivo stromal architecture heterogeneity (SI Fig. 2A,B,D). As the tumor microenvironment often features wavy and bundled collagen fibers, we embedded human cells into our system. Regardless of their initial invasive potential, we observed increased migration in the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 and the immortalized breast cell line MCF10A in our thick collagen scaffolds. We found that in thick collagen, MDA-MB-231 cell dissemination was significantly augmented in co-culture with normal human lung fibroblasts (SI Fig. 8, SI Video 2B). Fast migration of MDA-MB-231 cells relied on ROCK-mediated cell contractility and formin-based protrusive structures, but is MMP-independent. Characterization of both MCF10A single cells and MCF10A acini demonstrated differential behavior in thick collagen compared with normal collagen. Other cell types also appeared to exhibit similar behaviors in thick collagen (SI Video 2C). Our findings agree with observations of cells on wavy ECM substrates, which highlight the role of cell contractility [22].

There have been many different previously reported ways of modifying collagen architecture for 3D cultures. However, compared with previous work, our collagen demonstrated better global resemblance to in vivo ECM architecture (SI Fig. 2A–B). We generated this type of architecture in reconstituted collagen gels by applying mechanical agitation during fibrillogenesis and gelation. Thus, our method opens a new way of collagen architecture modification by integrating mechanical shearing during in vitro fibrillogenesis. More architectures of collagen can be created in the future by tuning mechanical disruption and temperature. Our thick collagen may serve as a better platform to examine and compare cell migration behaviors in 3D, as this type of collagen architecture has decoupled the confounding effect of physical restraints from other factors. Physical limits or steric restraints [21,24] of collagen greatly impact cell behavior. Most previous reports of tumor cell migration in 3D collagen were based on the normal collagen scaffold, which was strongly impacted by matrix proteolysis [48,70,71], suggesting MMP inhibition as a strategy against invasion. However, our thick collagen suggested an adjusted view of MMP inhibitors since they may be ineffective in heterogeneous and clustered collagen environments such as our thick collagen gels. In addition, our results agreed with intravital imaging work [72] that the migration of breast tumor cells in vivo is MMP-independent and may provide additional indications for the reasons for the failure of MMP inhibitors in clinical trials [73]. Without physical restraints, thick collagen could help further stratify drug performance in in vivo-like microenvironments. For example, in normal collagen, GM6001/ML141/SMIFH2/NSC23766/EHT1864 appeared to exert the same effects on cell morphology. However, MDA-MB-231 cells in thick collagen fell into two subgroups: GM6001/ML141/EHT1864 response versus SMIFH2/NSC23766 response (Fig. 4B). Altogether, thick collagen bundles have the potential to be applied in drug screening for targeting cell phenotypes in more complex microenvironments.

Further, this type of collagen can be easily integrated into co-culture assays as with normal collagen. The unique architecture and mechanical features of this thick collagen introduce a different overall picture of the mechanical landscape that scaffolds cells in culture. Our method captures the spatial heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Our findings echoed one intravital imaging study of breast cancer [72] which identified two subpopulations of tumor cell phenotypes, and their multiparameter classification links the driving factor of these two subpopulations to their relative locations in the TME. This study also supported the importance of spatial heterogeneity of TME. The overall features of this thick collagen system are summarized in Fig. 8. We also proposed the existence of paratensile signaling in thick collagen networks in Fig. 8, which may account for the increased MDA-MB-231 migration in the presence of NHLF in thick collagen (SI Fig. 8). A limitation in this system was a lack of molecular and cellular complexity. Importantly, our thick collagen scaffolds were solely composed of collagen I and did not include other important ECM proteins such as hyaluronic acid, laminin, or fibronectin. In addition, our systems lacked other important cells which contribute to the TME such as vascular endothelial cells and immune cells. Other studies have created microtissue cancer scaffolds containing many cell types which not only gave rise to tumors with more physiologically relevant cell-cell interactions but also stimulated deposition of other ECM proteins which are correlated with cancer progression [74]. Future studies will explore how the addition of other cell types, which stimulate or participate in ECM protein deposition, can affect cancer cell migration in our thick collagen scaffolds.

Fig. 8.

Summarized thick collagen features. Summarized features of thick collagen network compared with normal collagen. Thick collagen gels are heterogeneous and impose low physical restraints compared with normal collagen. We hypothesize that paratensile signaling may exist in thick collagen that allows for long range intercellular communication.

As thick collagen gels were locally dense but globally soft, they provided a way to separate local scale mechanics from global scale mechanics. Additionally, previous research has shown that the stiffness of collagen gels increases with increasing collagen concentration [75]. From confocal imaging, thick collagen bundles were of higher density compared with the thin fiber collagen network in the background of thick collagen gels. Taken together, it may be possible to conclude that thick collagen networks have a soft background but contain stiff inclusions. Previous studies have shown the importance of scales in mechanical interactions. For example, long-distance matrix-mediated mechanical communication exists [76–80], fibroblasts can recruit macrophages from 100-200 micrometers away in fibrillar collagen [81], floating gels regulate cells differently compared with anchored gels [82,83], with the same surface coating, the thickness of the coating regulates cell behavior [32], tissue-scale deformations can control wound closure [23], among others. Mesoscale clustered collagen architectures may provide a tool to study these phenomena. Aside from tumor modeling, the thick collagen gels have potential applications in 3D wound modeling, stem cell differentiation, and primary cell cultures.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance.

Tumor progression usually involves chronic tissue damage and repair processes. Hallmarks of tumors are highly overlapped with those of wound healing. To mimic the tumor milieu, collagen-based scaffolds are widely used. These scaffolds focus on modulating microscale topographies and mechanics, lacking global architecture similarity compared with in vivo architecture. Here we introduced one type of thick collagen bundles that mimics ECM architecture in human skin scars. These thickened collagen bundles are long and wavy while featuring global softness. This collagen architecture imposes fewer steric restraints and promotes tumor cell dissemination. Our findings demonstrate a distinct picture of cell behaviors and intercellular interactions, highlighting the importance of collagen architecture and spatial heterogeneity of the tumor microenvironment.

Acknowledgements

M.M. acknowledges support from the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant number R35GM142875. C.L. acknowledges support from Professor Rong Fan during manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.11.011.

Data availability statement

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- [1].Dvorak HF, Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing, N. Engl. J. Med 315 (1986) 1650–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Arwert EN, Hoste E, Watt FM, Epithelial stem cells, wound healing and cancer, Nat. Rev. Cancer 12 (2012) 170–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].MacCarthy-Morrogh L, Martin P, The hallmarks of cancer are also the hallmarks of wound healing, Sci. Signal (2020) 13, doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aay8690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Xue M, Jackson CJ, Extracellular matrix reorganization during wound healing and its impact on abnormal scarring, Adv. Wound Care 4 (2015) 119–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Behan FM, Iorio F, Picco G, Gonçalves E, Beaver CM, Migliardi G, Santos R, Rao Y, Sassi F, Pinnelli M, Ansari R, Harper S, Jackson DA, McRae R, Pooley R, Wilkinson P, van der Meer D, Dow D, Buser-Doepner C, Bertotti A, Trusolino L, Stronach EA, Saez-Rodriguez J, Yusa K, Garnett MJ, Prioritization of cancer therapeutic targets using CRISPR-Cas9 screens, Nature 568 (2019) 511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cox TR, Erler JT, Remodeling and homeostasis of the extracellular matrix: implications for fibrotic diseases and cancer, Dis. Model. Mech 4 (2011) 165–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yuzhalin AE, Lim SY, Kutikhin AG, Gordon-Weeks AN, Dynamic matrisome: ECM remodeling factors licensing cancer progression and metastasis, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1870 (2018) 207–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nguyen RY, Xiao H, Gong X, Arroyo A, Cabral AT, Fischer TT, Flores KM, Zhang X, Robert ME, Ehrlich BE, Mak M, Cytoskeletal dynamics regulates stromal invasion behavior of distinct liver cancer subtypes, Commun Biol. 5 (2022) 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Conklin MW, Eickhoff JC, Riching KM, Pehlke CA, Eliceiri KW, Provenzano PP, Friedl A, Keely PJ, Aligned collagen is a prognostic signature for survival in human breast carcinoma, Am. J. Pathol 178 (2011) 1221–1232 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kaur A, Ecker BL, Douglass SM, Kugel CH 3rd, Webster MR, Almeida FV, Somasundaram R, Hayden J, Ban E, Ahmadzadeh H, Franco-Barraza J, Shah N, Mellis IA, Keeney F, Kossenkov A, Tang H-Y, Yin X, Liu Q, Xu X, Fane M, Brafford P, Herlyn M, Speicher DW, Wargo JA, Tetzlaff MT, Haydu LE, Raj A, Shenoy V, Cukierman E, Weeraratna AT, Remodeling of the collagen matrix in aging skin promotes melanoma metastasis and affects immune cell motility, Cancer Discov. 9 (2019) 64–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wood SL, Pernemalm M, Crosbie PA, Whetton AD, The role of the tumor-microenvironment in lung cancer-metastasis and its relationship to potential therapeutic targets, Cancer Treat. Rev 40 (2014) 558–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chakravarthy A, Khan L, Bensler NP, Bose P, De Carvalho DD, TGF-β-associated extracellular matrix genes link cancer-associated fibroblasts to immune evasion and immunotherapy failure, Nat. Commun 9 (2018) 4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pizzurro GA, Liu C, Bridges K, Alexander AF, Huang A, Baskaran JP, Ramseier J, Bosenberg MW, Mak M, Miller-Jensen K, 3D model of the early melanoma microenvironment captures macrophage transition into a tumor-promoting phenotype, Cancers 13 (2021), doi: 10.3390/cancers13184579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Seo BR, Chen X, Ling L, Song YH, Shimpi AA, Choi S, Gonzalez J, Sapudom J, Wang K, Andresen Eguiluz RC, Gourdon D, Shenoy VB, Fischbach C, Collagen microarchitecture mechanically controls myofibroblast differentiation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117 (2020) 11387–11398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kalbitzer L, Pompe T, Fibril growth kinetics link buffer conditions and topology of 3D collagen I networks, Acta Biomater. 67 (2018) 206–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sapudom J, Rubner S, Martin S, Kurth T, Riedel S, Mierke CT, Pompe T, The phenotype of cancer cell invasion controlled by fibril diameter and pore size of 3D collagen networks, Biomaterials 52 (2015) 367–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yang Y-L, Motte S, Kaufman LJ, Pore size variable type I collagen gels and their interaction with glioma cells, Biomaterials 31 (2010) 5678–5688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mason BN, Starchenko A, Williams RM, Bonassar LJ, Reinhart-King CA, Tuning three-dimensional collagen matrix stiffness independently of collagen concentration modulates endothelial cell behavior, Acta Biomater. 9 (2013) 4635–4644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wisdom KM, Adebowale K, Chang J, Lee JY, Nam S, Desai R, Rossen NS, Rafat M, West RB, Hodgson L, Chaudhuri O, Matrix mechanical plasticity regulates cancer cell migration through confining microenvironments, Nat. Commun 9 (2018) 4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Riching KM, Cox BL, Salick MR, Pehlke C, Riching AS, Ponik SM, Bass BR, Crone WC, Jiang Y, Weaver AM, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ, 3D collagen alignment limits protrusions to enhance breast cancer cell persistence, Biophys. J 107 (2014) 2546–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mosier JA, Rahman-Zaman A, Zanotelli MR, VanderBurgh JA, Bordeleau F, Hoffman BD, Reinhart-King CA, Extent of cell confinement in microtracks affects speed and results in differential matrix strains, Biophys. J 117 (2019) 1692–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fischer RS, Sun X, Baird MA, Hourwitz MJ, Seo BR, Pasapera AM, Mehta SB, Losert W, Fischbach C, Fourkas JT, Waterman CM, Contractility, focal adhesion orientation, and stress fiber orientation drive cancer cell polarity and migration along wavy ECM substrates, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (2021) 118, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021135118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sakar MS, Eyckmans J, Pieters R, Eberli D, Nelson BJ, Chen CS, Cellular forces and matrix assembly coordinate fibrous tissue repair, Nat. Commun 7 (2016) 11036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Guzman A, Ziperstein MJ, Kaufman LJ, The effect of fibrillar matrix architecture on tumor cell invasion of physically challenging environments, Biomaterials 35 (2014) 6954–6963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chen G, Liu Y, Zhu X, Huang Z, Cai J, Chen R, Xiong S, Zeng H, Phase and texture characterizations of scar collagen second-harmonic generation images varied with scar duration, Microsc. Microanal 21 (2015) 855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kiss N, Haluszka D, Lőrincz K, Kuroli E, Hársing J, Mayer B, Kárpáti S, Fekete G, Szipőcs R, Wikonkál N, Medvecz M, Ex vivo nonlinear microscopy imaging of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome-affected skin, Arch. Dermatol. Res 310 (2018) 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tien J, Nelson CM, Microstructured extracellular matrices in tissue engineering and development: an update, Ann. Biomed. Eng 42 (2014) 1413–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yoo J, Park JH, Kwon YW, Chung JJ, Choi IC, Nam JJ, Lee HS, Jeon EY, Lee K, Kim SH, Jung Y, Park JW, Augmented peripheral nerve regeneration through elastic nerve guidance conduits prepared using a porous PLCL membrane with a 3D printed collagen hydrogel, Biomater Sci. 8 (2020) 6261–6271 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gong X, Kulwatno J, Mills KL, Rapid fabrication of collagen bundles mimicking tumor-associated collagen architectures, Acta Biomater. 108 (2020) 128–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sauer F, Oswald L, Ariza de Schellenberger A, Tzschätzsch H, Schrank F, Fischer T, Braun J, Mierke CT, Valiullin R, Sack I, Käs JA, Collagen networks determine viscoelastic properties of connective tissues yet do not hinder diffusion of the aqueous solvent, Soft Matter 15 (2019) 3055–3064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kadler KE, Hill A, Canty-Laird EG, Collagen fibrillogenesis: fibronectin, integrins, and minor collagens as organizers and nucleators, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 20 (2008) 495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS, Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures, Methods 30 (2003) 256–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ban E, Franklin JM, Nam S, Smith LR, Wang H, Wells RG, Chaudhuri O, Liphardt JT, Shenoy VB, Mechanisms of plastic deformation in collagen networks induced by cellular forces, Biophys. J 114 (2018) 450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB, Mussel-inspired surface chemistry for multifunctional coatings, Science 318 (2007) 426–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yu X, Walsh J, Wei M, Covalent immobilization of collagen on titanium through polydopamine coating to improve cellular performances of MC3T3-E1 cells, RSC Adv. 4 (2013) 7185–7192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gorelik R, Gautreau A, Quantitative and unbiased analysis of directional persistence in cell migration, Nat. Protoc 9 (2014) 1931–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Liu C, Mak M, Fibroblast-mediated uncaging of cancer cells and dynamic evolution of the physical microenvironment, Sci. Rep 12 (2022) 791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sapudom J, Kalbitzer L, Wu X, Martin S, Kroy K, Pompe T, Fibril bending stiffness of 3D collagen matrices instructs spreading and clustering of invasive and non-invasive breast cancer cells, Biomaterials 193 (2019) 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wood GC, The formation of fibrils from collagen solutions. 2. A mechanism of collagen-fibril formation, Biochem. J 75 (1960) 598–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Silver FH, Birk DE, Kinetic analysis of collagen fibrillogenesis: I. Use of turbidity–time data, Coll. Relat. Res 3 (1983) 393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhu J, Kaufman LJ, Collagen I self-assembly: revealing the developing structures that generate turbidity, Biophys. J 106 (2014) 1822–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rosenblatt J, Devereux B, Wallace DG, Injectable collagen as a pH-sensitive hydrogel, Biomaterials 15 (1994) 985–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].de Wild M, Pomp W, Koenderink GH, Thermal memory in self-assembled collagen fibril networks, Biophys. J 105 (2013) 200–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dai X, Cheng H, Bai Z, Li J, Breast cancer cell line classification and its relevance with breast tumor subtyping, J. Cancer 8 (2017) 3131–3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Nuhn JAM, Perez AM, Schneider IC, Contact guidance diversity in rotationally aligned collagen matrices, Acta Biomater. 66 (2018) 248–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Han W, Chen S, Yuan W, Fan Q, Tian J, Wang X, Chen L, Zhang X, Wei W, Liu R, Qu J, Jiao Y, Austin RH, Liu L, Oriented collagen fibers direct tumor cell intravasation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113 (2016) 11208–11213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Geiger F, Rüdiger D, Zahler S, Engelke H, Fiber stiffness, pore size and adhesion control migratory phenotype of MDA-MB-231 cells in collagen gels, PLoS One 14 (2019) e0225215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wolf K, Te Lindert M, Krause M, Alexander S, Te Riet J, Willis AL, Hoffman RM, Figdor CG, Weiss SJ, Friedl P, Physical limits of cell migration: control by ECM space and nuclear deformation and tuning by proteolysis and traction force, J. Cell Biol 201 (2013) 1069–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bos PD, Zhang XH-F, Nadal C, Shu W, Gomis RR, Nguyen DX, Minn AJ, van de Vijver MJ, Gerald WL, Foekens JA, Massagué J, Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to the brain, Nature 459 (2009) 1005–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, Drobnjak M, Kakonen SM, Cordón-Cardo C, Guise TA, Massagué J, A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone, Cancer Cell 3 (2003) 537–549 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Minn AJ, Kang Y, Serganova I, Gupta GP, Giri DD, Doubrovin M, Ponomarev V, Gerald WL, Blasberg R, Massagué J, Distinct organ-specific metastatic potential of individual breast cancer cells and primary tumors, J. Clin. Invest 115 (2005) 44–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pandya P, Orgaz JL, Sanz-Moreno V, Actomyosin contractility and collective migration: may the force be with you, Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 48 (2017) 87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pollard TD, Regulation of actin filament assembly by Arp2/3 complex and formins, Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct 36 (2007) 451–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Goode BL, Eck MJ, Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly, Annu. Rev. Biochem 76 (2007) 593–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Amano M, Nakayama M, Kaibuchi K, Rho-kinase/ROCK: A key regulator of the cytoskeleton and cell polarity, Cytoskeleton 67 (2010) 545–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Sadok A, Marshall CJ, Rho GTPases: masters of cell migration, Small GTPases 5 (2014) e29710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Singh D, Srivastava SK, Chaudhuri TK, Upadhyay G, Multifaceted role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), Front. Mol. Biosci 2 (2015) 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Vicente-Manzanares M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Horwitz AR, Non-muscle myosin II takes centre stage in cell adhesion and migration, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 10 (2009) 778–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Hofbauer SW, Krenn PW, Ganghammer S, Asslaber D, Pichler U, Oberascher K, Henschler R, Wallner M, Kerschbaum H, Greil R, Hartmann TN, Tiam1/Rac1 signals contribute to the proliferation and chemoresistance, but not motility, of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells, Blood 123 (2014) 2181–2188 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gao Y, Dickerson JB, Guo F, Zheng J, Zheng Y, Rational design and characterization of a Rac GTPase-specific small molecule inhibitor, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 11 (2004) 7618–7623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Shutes A, Onesto C, Picard V, Leblond B, Schweighoffer F, Der CJ, Specificity and mechanism of action of EHT 1864, a novel small molecule inhibitor of Rac family small GTPases, J. Biol. Chem 282 (2007) 35666–35678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Wang Y, Gong J, Yao Y, Extracellular nanofiber-orchestrated cytoskeletal reorganization and mediated directional migration of cancer cells, Nanoscale 12 (2020) 3183–3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].McGrail DJ, Kieu QMN, Dawson MR, The malignancy of metastatic ovarian cancer cells is increased on soft matrices through a mechanosensitive Rho-ROCK pathway, J. Cell Sci 127 (2014) 2621–2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].McGrail DJ, Kieu QMN, landoli JA, Dawson MR, Actomyosin tension as a determinant of metastatic cancer mechanical tropism, Phys. Biol 12 (2015) 026001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Nishimura Y, Shi S, Zhang F, Liu R, Takagi Y, Bershadsky AD, Viasnoff V, Sellers JR, The formin inhibitor SMIFH2 inhibits members of the myosin superfamily, J. Cell Sci 134 (2021), doi: 10.1242/jcs.253708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Cowell JK, LaDuca J, Rossi MR, Burkhardt T, Nowak NJ, Matsui S-I, Molecular characterization of the t(3;9) associated with immortalization in the MCF10A cell line, Cancer Genet. Cytogenet 163 (2005) 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Shi Q, Ghosh RP, Engelke H, Rycroft CH, Cassereau L, Sethian JA, Weaver VM, Liphardt JT, Rapid disorganization of mechanically interacting systems of mammary acini, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111 (2014) 658–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, Zan-conato F, Le Digabel J, Forcato M, Bicciato S, Elvassore N, Piccolo S, Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction, Nature 474 (2011) 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bays JL, DeMali KA, Vinculin in cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 74 (2017) 2999–3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zaman MH, Trapani LM, Sieminski AL, Mackellar D, Gong H, Kamm RD, Wells A, Lauffenburger DA, Matsudaira P, Migration of tumor cells in 3D matrices is governed by matrix stiffness along with cell-matrix adhesion and proteolysis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 (2006) 10889–10894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Sabeh F, Ota I, Holmbeck K, Birkedal-Hansen H, Soloway P, Balbin M, Lopez-Otin C, Shapiro S, Inada M, Krane S, Allen E, Chung D, Weiss SJ, Tumor cell traffic through the extracellular matrix is controlled by the membrane-anchored collagenase MT1-MMP, J. Cell Biol 167 (2004) 769–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Gligorijevic B, Bergman A, Condeelis J, Multiparametric classification links tumor microenvironments with tumor cell phenotype, PLoS Biol. 12 (2014) e1001995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Fingleton B, MMP inhibitor clinical trials – the past, present, and future, in: The Cancer Degradome, Springer New York, New York, NY, 2008, pp. 759–785. [Google Scholar]

- [74].Recapitulating spatiotemporal tumor heterogeneity in vitro through engineered breast cancer microtissues, Acta Biomater. 73 (2018) 236–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Motte S, Kaufman LJ, Strain stiffening in collagen I networks, Biopolymers 99 (2013) 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Sunyer R, Conte V, Escribano J, Elosegui-Artola A, Labernadie A, Valon L, Navajas D, García-Aznar JM, Muñoz JJ, Roca-Cusachs P, Trepat X, Collective cell durotaxis emerges from long-range intercellular force transmission, Science 353 (2016) 1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].van Oers RFM, Rens EG, LaValley DJ, Reinhart-King CA, Merks RMH, Mechanical cell-matrix feedback explains pairwise and collective endothelial cell behavior in vitro, PLoS Comput. Biol 10 (2014) e1003774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Wang H, Abhilash AS, Chen CS, Wells RG, Shenoy VB, Long-range force transmission in fibrous matrices enabled by tension-driven alignment of fibers, Biophys. J 107 (2014) 2592–2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Pakshir P, Alizadehgiashi M, Wong B, Coelho NM, Chen X, Gong Z, Shenoy VB, McCulloch CA, Hinz B, Dynamic fibroblast contractions attract remote macrophages in fibrillar collagen matrix, Nat. Commun 10 (2019) 1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Reinhart-King CA, Dembo M, Hammer DA, Cell-cell mechanical communication through compliant substrates, Biophys. J 95 (2008) 6044–6051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Wozniak MA, Desai R, Solski PA, Der CJ, Keely PJ, ROCK-generated contractility regulates breast epithelial cell differentiation in response to the physical properties of a three-dimensional collagen matrix, J. Cell Biol 163 (2003) 583–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Grinnell F, Ho CH, Lin YC, Skuta G, Differences in the regulation of fibroblast contraction of floating versus stressed collagen matrices, J. Biol. Chem 274 (1999) 918–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Leong WS, Tay CY, Yu H, Li A, Wu SC, Duc D-H, Lim CT, Tan LP, Thickness sensing of hMSCs on collagen gel directs stem cell fate, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 401 (2010) 287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.