Abstract

Background

Child sexual abuse is a significant global problem in both magnitude and sequelae. The most widely used primary prevention strategy has been the provision of school‐based education programmes. Although programmes have been taught in schools since the 1980s, their effectiveness requires ongoing scrutiny.

Objectives

To systematically assess evidence of the effectiveness of school‐based education programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse. Specifically, to assess whether: programmes are effective in improving students' protective behaviours and knowledge about sexual abuse prevention; behaviours and skills are retained over time; and participation results in disclosures of sexual abuse, produces harms, or both.

Search methods

In September 2014, we searched CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE and 11 other databases. We also searched two trials registers and screened the reference lists of previous reviews for additional trials.

Selection criteria

We selected randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cluster‐RCTs, and quasi‐RCTs of school‐based education interventions for the prevention of child sexual abuse compared with another intervention or no intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the eligibility of trials for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias. We summarised data for six outcomes: protective behaviours; knowledge of sexual abuse or sexual abuse prevention concepts; retention of protective behaviours over time; retention of knowledge over time; harm; and disclosures of sexual abuse.

Main results

This is an update of a Cochrane Review that included 15 trials (up to August 2006). We identified 10 additional trials for the period to September 2014. We excluded one trial from the original review. Therefore, this update includes a total of 24 trials (5802 participants). We conducted several meta‐analyses. More than half of the trials in each meta‐analysis contained unit of analysis errors.

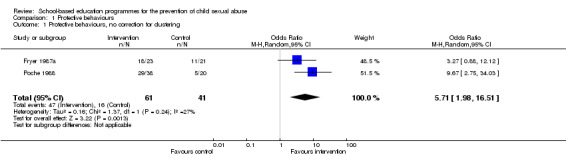

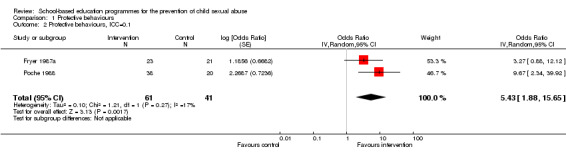

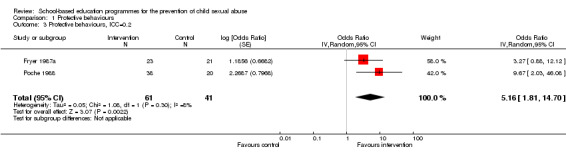

1. Meta‐analysis of two trials (n = 102) evaluating protective behaviours favoured intervention (odds ratio (OR) 5.71, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.98 to 16.51), with borderline low to moderate heterogeneity (Chi² = 1.37, df = 1, P value = 0.24, I² = 27%, Tau² = 0.16). The results did not change when we made adjustments using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) to correct errors made in studies where data were analysed without accounting for the clustering of students in classes or schools.

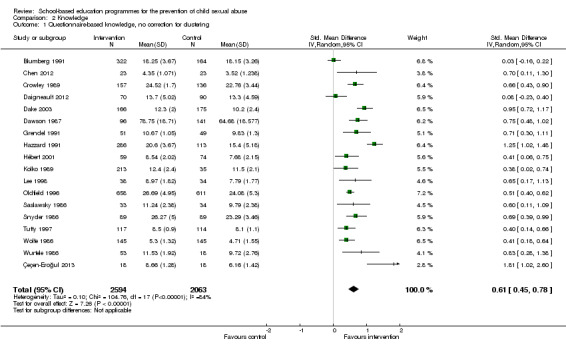

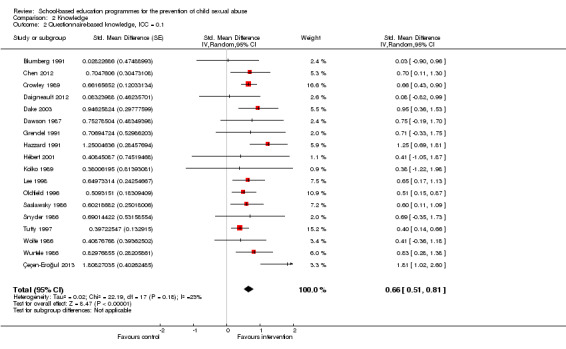

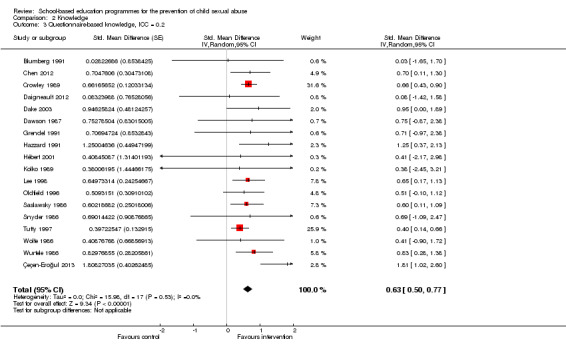

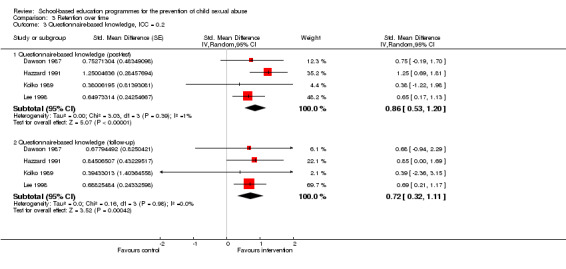

2. Meta‐analysis of 18 trials (n = 4657) evaluating questionnaire‐based knowledge favoured intervention (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.61, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.78), but there was substantial heterogeneity (Chi² = 104.76, df = 17, P value < 0.00001, I² = 84%, Tau² = 0.10). The results did not change when adjusted for clustering (ICC: 0.1 SMD 0.66, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.81; ICC: 0.2 SMD 0.63, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.77).

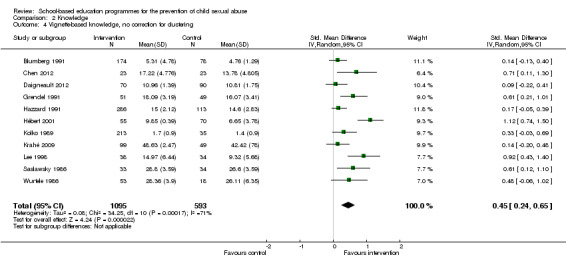

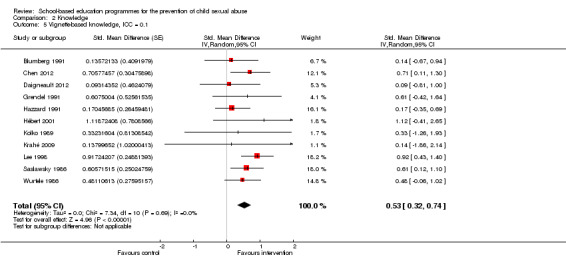

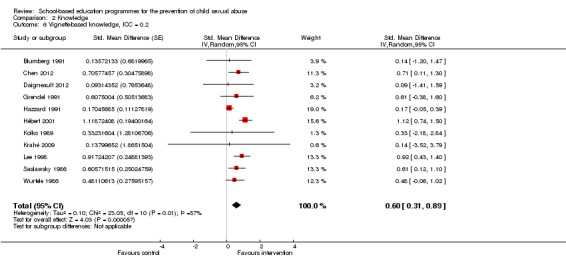

3. Meta‐analysis of 11 trials (n =1688) evaluating vignette‐based knowledge favoured intervention (SMD 0.45, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.65), but there was substantial heterogeneity (Chi² = 34.25, df = 10, P value < 0.0002, I² = 71%, Tau² = 0.08). The results did not change when adjusted for clustering (ICC: 0.1 SMD 0.53, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.74; ICC: 0.2 SMD 0.60, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.89).

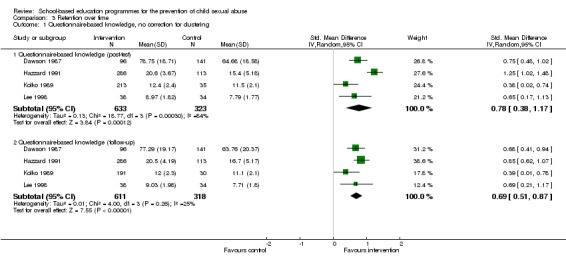

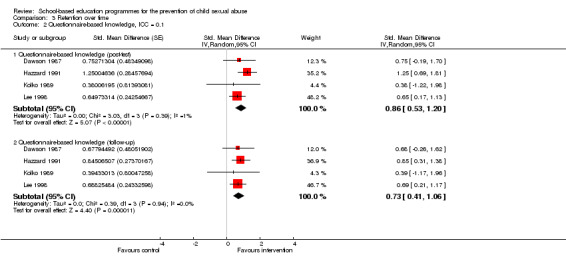

4. We included four trials in the meta‐analysis for retention of knowledge over time. The effect of intervention seemed to persist beyond the immediate assessment (SMD 0.78, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.17; I² = 84%, Tau² = 0.13, P value = 0.0003; n = 956) to six months (SMD 0.69, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.87; I² = 25%; Tau² = 0.01, P value = 0.26; n = 929). The results did not change when adjustments were made using ICCs.

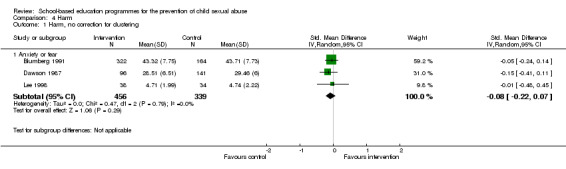

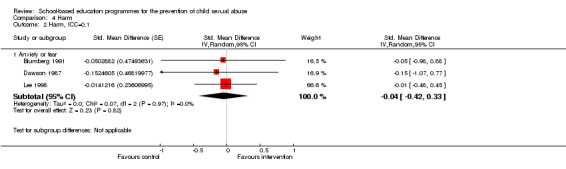

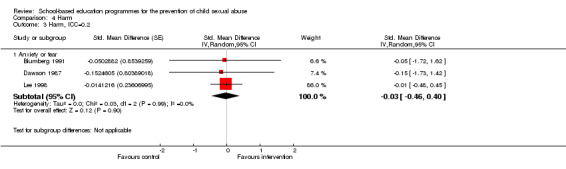

5. We included three studies in the meta‐analysis for adverse effects (harm) manifesting as child anxiety or fear. The results showed no increase or decrease in anxiety or fear in intervention participants (SMD ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.07; n = 795) and there was no heterogeneity (I² = 0%, P value = 0.79; n=795). The results did not change when adjustments were made using ICCs.

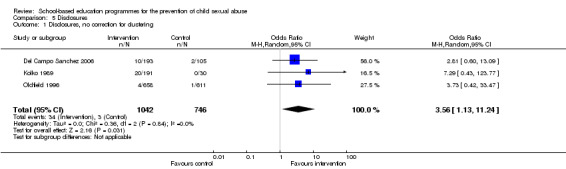

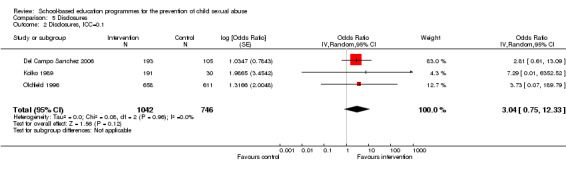

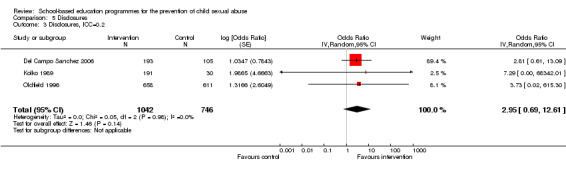

6. We included three studies (n = 1788) in the meta‐analysis for disclosure of previous or current sexual abuse. The results favoured intervention (OR 3.56, 95% CI 1.13 to 11.24), with no heterogeneity (I² = 0%, P value = 0.84). However, adjusting for the effect of clustering had the effect of widening the confidence intervals around the OR (ICC: 0.1 OR 3.04, 95% CI 0.75 to 12.33; ICC: 0.2 OR 2.95, 95% CI 0.69 to 12.61).

Insufficient information was provided in the included studies to conduct planned subgroup analyses and there were insufficient studies to conduct meaningful analyses.

The quality of evidence for all outcomes included in the meta‐analyses was moderate owing to unclear risk of selection bias across most studies, high or unclear risk of detection bias across over half of included studies, and high or unclear risk of attrition bias across most studies. The results should be interpreted cautiously.

Authors' conclusions

The studies included in this review show evidence of improvements in protective behaviours and knowledge among children exposed to school‐based programmes, regardless of the type of programme. The results might have differed had the true ICCs or cluster‐adjusted results been available. There is evidence that children's knowledge does not deteriorate over time, although this requires further research with longer‐term follow‐up. Programme participation does not generate increased or decreased child anxiety or fear, however there is a need for ongoing monitoring of both positive and negative short‐ and long‐term effects. The results show that programme participation may increase the odds of disclosure, however there is a need for more programme evaluations to routinely collect such data. Further investigation of the moderators of programme effects is required along with longitudinal or data linkage studies that can assess actual prevention of child sexual abuse.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Humans; Schools; Child Abuse, Sexual; Child Abuse, Sexual/prevention & control; Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice; Program Evaluation; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

School‐based programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse

Background and review question

School‐based education programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse have been implemented on a large scale in some countries. We reviewed the evidence for the effectiveness of these programmes in the following areas: (i) children's skills in protective behaviours; (ii) children's knowledge of child sexual abuse prevention concepts; (iii) children's retention of protective behaviours over time; (iv) children's retention of knowledge over time; (v) parental or child anxiety or fear as a result of programme participation; and (vi) disclosures of past or current child sexual abuse during or after programmes. The evidence is current to September 2014.

Study characteristics

This review included 24 studies, conducted with a total of 5802 participants in primary (elementary) and secondary (high) schools in the United States, Canada, China, Germany, Spain, Taiwan, and Turkey. The duration of interventions ranged from a single 45‐minute session to eight 20‐minute sessions on consecutive days. Although a wide range of programmes were used, there were many common elements, including the teaching of safety rules, body ownership, private parts of the body, distinguishing types of touches and types of secrets, and who to tell. Programme delivery formats included film, video or DVD, theatrical plays, and multimedia presentations. Other resources used included songs, puppets, comics, and colouring books. Teaching methods used in delivery included rehearsal, practice, role‐play, discussion, and feedback.

Key results

This review found evidence that school‐based sexual abuse prevention programmes were effective in increasing participants' skills in protective behaviours and knowledge of sexual abuse prevention concepts (measured via questionnaires or vignettes). Knowledge gains (measured via questionnaires) were not significantly eroded one to six months after the intervention for either intervention or control groups. In terms of harm, there was no evidence that programmes increased or decreased children's anxiety or fear. No studies measured parental anxiety or fear. Children exposed to a child sexual abuse prevention programme had greater odds of disclosing their abuse than children who had not been exposed, however we were more uncertain about this effect when the analysis was adjusted to account for the grouping of participants in classes or schools. Studies have not yet adequately measured the long‐term benefits of programmes in terms of reducing the incidence or prevalence (or both) of child sexual abuse in programme participants.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence for all outcomes included in the meta‐analyses (combining of data) was moderate. Study quality was compromised in about half of the included studies, due to suboptimal data collection methods for study outcomes and inappropriate data analysis.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| School‐based programme for the prevention of child sexual abuse compared with no intervention or standard school curriculum | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children (aged 5 to 12) and adolescents (aged 13 to 18) Settings: primary (elementary) or secondary (high) schools Intervention: school‐based education programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse Comparison: no intervention or standard school curriculum | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control group | Intervention group | |||||

| Protective behaviours (self protective events measured using a stranger simulation test immediately post intervention) | 390 per 1000 | 795 per 1000 (559 to 914) |

OR 5.71 (1.98 to 16.51) |

102 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Results favoured intervention |

|

Questionnaire‐based knowledge (factual knowledge measured by assessing responses to items on a questionnaire or multi‐choice test, immediately post intervention) (higher score = higher knowledge) |

The mean knowledge score measured using a variety of scales across control groups ranged from 3 to 64 | The mean knowledge score in the intervention groups was 0.61 standard deviations higher (0.45 higher to 0.78 higher) | 4657 (18) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | Results favoured intervention | |

|

Vignette‐based knowledge (applied knowledge measured by assessing responses to hypothetical scenarios, immediately post intervention) (higher score = higher knowledge) |

The mean knowledge score measured using a variety of instruments across control groups ranged from 1 to 42 | The mean knowledge score in the intervention groups was 0.45 standard deviations higher (0.24 higher to 0.65 higher) | 1688 (11) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | Results favoured intervention | |

| Harm (measured using anxiety or fear questionnaires) | The mean anxiety or fear score measured using a variety of scales across control groups ranged from 2 to 7 | The mean anxiety or fear score in the intervention groups was 0.08 standard deviations lower (0.22 lower to 0.07 higher) | 795 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | Results showed no increase or decrease in anxiety or fear | |

| Disclosures (of past or current child sexual abuse made during or after programme completion) | 4 per 1000 | 14 per 1000 (5 to 45) |

OR 3.56 (1.13 to 11.24) |

1788 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | Results favoured intervention, however when adjusted for unit of analysis errors, this effect disappeared |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Downgraded one level due to imprecision (wide confidence intervals). 2Downgraded one level due to risk of bias: unclear or high risk of bias for randomisation and allocation concealment, and blinding of participants or personnel 3Downgraded one level due to imprecision: 95% CIs around pooled estimate include both effect and no effect. 4 Downgraded one level following sensitivity analysis using ICCs of 0.1 and 0.2 to adjust for the effect of clustering on the results.

Background

Description of the condition

Child sexual abuse is a problem of considerable magnitude with short‐ and long‐term repercussions for those victimised. There is no universal definition of child sexual abuse (Macdonald 2001; Trickett 2006). It is a term used to describe a range of experiences involving a child in unwanted, inappropriate, coercive, and unlawful sexual exploitation by an adult or older child. The World Health Organization (WHO) definition states that "child sexual abuse is the involvement of a child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully comprehend, is unable to give informed consent to, or for which the child is not developmentally prepared and cannot give consent, or that violates the laws or social taboos of society" (WHO 1999, p 15). Child sexual abuse is categorised along a continuum according to the type of abuse experienced by the child: involving physical body contact (using the term 'contact child sexual abuse') or not involving physical body contact (using the term "non‐contact child sexual abuse"). Contact acts include unwanted touching, fondling, masturbation, frottage, oral‐genital contact, and vaginal or anal penetration by a penis, finger or other object. Non‐contact acts include making sexual comments, voyeurism ('peeping'), exhibitionism ('flashing'), exposing a child to pornography, or making pornography (Finkelhor 2008; Putnam 2003). Recent meta‐analyses of data collected from retrospective studies of adults in countries and cultures worldwide estimate that 10% to 20% of female children, and 5% to 10% of male children, have experienced child sexual abuse on a spectrum from exposure through unwanted touching to penetrative assault before the age of 18 years (Barth 2013; Ji 2013; Pereda 2009; Stoltenborgh 2011). These data are likely to underestimate its true prevalence because two‐thirds of individuals never disclose their victimisation (London 2005) and most cases go unreported to authorities (Wyatt 1999). The WHO estimates that child sexual abuse contributes to seven to eight per cent of the global burden of disease for females, and four to five per cent for males (Andrews 2004).

Child sexual abuse is associated with adverse psychosocial outcomes such as depression (Roosa 1999), post‐traumatic stress disorder (Widom 1999), antisocial and suicidal behaviours (Bensley 1999), eating disorders (Perkins 1999), alcohol and substance abuse (Spak 1998), post‐partum depression and parenting difficulties (Buist 1998), sexual re‐victimisation, and sexual dysfunction (Fleming 1999). A recent meta‐analysis found child sexual abuse was also associated with higher rates of physical health conditions, including gastrointestinal, gynaecological, and cardiovascular problems, and obesity (Irish 2010). A longitudinal analysis of the association between childhood sexual abuse and educational achievement found a clear linear relationship between increasing severity of child sexual abuse and poorer educational achievement, however the relationship was confounded by sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. lower maternal age and qualifications) and family functioning variables (e.g. inter‐parental violence) known to be associated with child maltreatment (Boden 2007). These consequences are far‐reaching into families and communities, with significant costs for institutions in terms of primary and rehabilitative health care, education and welfare assistance, child protection, and justice system costs (Fang 2012).

Given the retrospective nature of many studies, it is unclear what proportion of survivors go on to experience adverse outcomes and how sexual abuse interacts with other potential risk factors for these adverse outcomes. However, outcomes are known to vary for individuals according to: child age and gender; perpetrator age and gender; the relationship between child and perpetrator; the severity, duration, and/or frequency of the abusive act(s); accompanying physical or emotional violence and/or force; and the presence of other forms of victimisation (Putnam 2003; Trickett 1997). Sexual abuse has been reported across all socioeconomic and ethnic groups, in both males and females, and perpetrators can include those outside the family as well as within it (Finkelhor 1993); they can be adults or other young people (Turner 2011). However, all children are not at equal risk. Risk factors for child sexual abuse, mainly identified in Western countries, include being female (Fergusson 1996), having a physical or mental disability (Westcott 1999), living without a natural parent (Finkelhor 1986; Finkelhor 1990), parental mental illness, parental alcohol or drug dependency, and young maternal age (Fergusson 1996; Holmes 1998; MacMillan 2013). Girls appear to be more likely to be sexually abused by family members and boys by non‐family members (Finkelhor 1990). The time of greatest vulnerability for child sexual abuse is between 7 and 12 years of age (Finkelhor 1986).

Description of the intervention

This review focuses on the most widely used strategy for the prevention of child sexual abuse: the provision of school‐based programmes. Some terms commonly used to describe these programmes include: personal safety education (NCMEC 1999); protective behaviours (Flandreau‐West 1984); personal body safety (Miller‐Perrin 1990); body safety (Wurtele 2007); and child assault prevention and child protection education (NSW Department of School Education 1998). These programmes target children and adolescents aged 5 to 18 years who are students in primary (elementary) or secondary (high) schools. Support for interventions of this type can be found in Article 19 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, an international law, which states that governments should "take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse" (United Nations 1989).

Education programmes to reduce the occurrence of sexual abuse in children and adolescents were first developed by women's rape prevention collectives in the United States of America (USA) in the 1970s (Berrick 1991). School‐based programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse were rapidly and widely adopted across the USA, assisted in some states by policy mandates, and by the mid 1990s it was estimated that two‐thirds of 10‐ to 16‐year olds in the USA had participated in such programmes (Finkelhor 1995c). Schools are a logical choice for teaching children about sexual abuse and its prevention, given their primary function is to educate (Wurtele 2009), and the content of prevention programmes aligns with proscribed school health curricula (Walsh 2013). Hence, schools have emerged as an important primary and secondary prevention setting providing access to large populations of children and adolescents, and relatively economical service delivery, without stigmatising those who may be at particular risk (Wurtele 2010).

School‐based child sexual abuse prevention programmes are typically presented to groups of students and are tailored to ages and cognitive levels. Programme content covers themes such as body ownership; distinguishing types of touches; identifying potential abuse situations; avoiding, resisting, or escaping such situations; secrecy; and how and whom to tell if abuse has occurred (Duane 2002; Topping 2009). Many programmes also stress that the child or adolescent is not to blame. Programmes vary in the number of, and extent to which these themes are covered. There is considerable variability in programme delivery formats and teaching methods. Formats such as books, comics, dramatic plays, puppet shows, films, lectures, and discussions have been used with some programmes employing single formats, whereas others use combinations of formats (Duane 2002; Topping 2009; Wurtele 1987a). Programme teaching methods have been conceptualised on a continuum from those employing purely didactic approaches, such as a speech, address, or talk, stressing students' passive listening and acquisition of knowledge, to those employing behavioural approaches, such as modelling, and emphasising students' active participation in role‐play, rehearsing, or practising new self protection skills (Wurtele 1987a). The duration and frequency of programmes is diverse, with 30 minutes being a common length as this fits with a standard school lesson period. Programmes also vary in their scope with some programmes dealing only with child sexual abuse, whereas others integrate these themes into programmes covering broader issues such as general safety education, social and emotional learning, mental health and well being, respectful relationships, and sexuality education. This review focuses only upon interventions in which prevention of child sexual abuse is the main goal.

How the intervention might work

The ultimate goal of child sexual abuse prevention education is to prevent children from ever experiencing abuse. It is also important, in cases where children have experienced abuse, for adults to respond quickly and effectively to disclosures, to protect them from further victimisation, and to limit the harm caused. From a public health perspective (Rosenberg 1991), comprehensive approaches to child sexual abuse would involve multiple "prevention targets", including (i) offenders and potential offenders, (ii) children and adolescents, (iii) situations, and (iv) communities (Smallbone 2008, p 47). Although not yet rigorously researched, it appears that school‐based programmes may also work to enhance community capacity for sexual abuse prevention by raising awareness and delivering information to multiple members of children's social systems (Duane 2002), via provision of information packages to parents, training for teachers, and family participation in homework activities.

School‐based sexual abuse prevention programmes focus on children and adolescents as prevention targets. They seek to prevent child sexual abuse by providing students with knowledge and skills to recognise and avoid potentially sexually abusive situations, and with strategies to physically and verbally repel sexual approaches by offenders. They endeavour to minimise harm by disseminating messages about appropriate help seeking in the event of abuse or attempted abuse. Interventions aim to transfer the knowledge and skills learned by the child or adolescent in the classroom to real‐life situations. Interventions work by capitalising on principles used by classroom teachers, most notably social cognitive learning theories (Bandura 1986; Vygotsky 1986), which stress the social context of learning via the use of instruction, modelling, rehearsal, reinforcement, and feedback (Wurtele 1987a).

Do programmes actually prevent child sexual abuse? There is some evidence from a small group of studies, all of which have been conducted in the USA, that participation in school‐based child sexual abuse prevention programmes may decrease the occurrence of child sexual abuse. A study of 2000 10‐ to 16‐year olds found that those exposed to more comprehensive prevention education were more knowledgeable about sexual abuse, more likely to report using self protection strategies, more likely to report protective efficacy, more likely to have disclosed their victimisation, and less likely to engage in self blame (Finkelhor 1995a). In a follow‐up study, the same individuals were more likely to use the protective strategies they had been taught when confronted with threats and assaults (Finkelhor 1995b). Two studies with high‐school (Ko 2001) and college students (Gibson 2000) showed programmes were associated with reduced incidence of child sexual abuse. However these studies harbour the limitations of retrospective recall and have not been replicated with larger and more diverse samples. Research with sexual offenders on their perceptions of the efficacy of children's self protection strategies in actual abuse situations has found the most effective strategy, reported by three‐quarters of offenders, was to tell the offender they did not want to participate in sexual activities. Girls under the age of 12 years effectively used six strategies to avoid abuse: demanding to be left alone, saying they would tell someone, crying, saying they were scared, saying the they did not want to, and saying "no" (Leclerc 2011). These strategies are key content in school‐based child sexual abuse prevention programmes (Duane 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite widespread adoption into the school curriculum in many countries, conclusions about the effectiveness of school‐based programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse remain tentative. A number of research synthesis studies have been conducted on this topic in the form of meta‐analyses, and systematic and narrative reviews (see Table 2: Previous reviews). However the findings have been limited by methodological weaknesses in the reviews (e.g. including non‐randomised as well as randomised studies; aggregation of diverse outcomes; inappropriate analytical approaches), and in the individual studies included in the reviews (e.g. use of diverse measures; inadequate measurement of programme fidelity). Additionally, previous meta‐analyses have differed in their parameters and have not been replicated. Further, there are historical distinctions in previous reviews, for example, the classification of programmes as primarily active or passive, behavioural or instructional, that warrant further exploration; this particular distinction seems artificial from an educational perspective because many programmes are, in practice, multifaceted, involving a number of teaching methods that are used in integrated ways to deliver programme content (MacMillan 1994). What is needed is a way of identifying, more precisely, the range of child, programme, and study design characteristics that may moderate programme effectiveness.

1. Previous reviews.

| Meta‐analyses | Systematic reviews | Narrative reviews | Systematic reviews of reviews |

|

Berrick 1992 Davis 2000 Heidotting 1994 Rispens 1997 Zwi 2007 |

Duane 2002 Kenny 2008 MacIntyre 2000 MacMillan 1994 Topping 2009 |

Albers 1991 Carroll 1992 Conte 1986 Daro 1991 Daro 1994 Finkelhor 2007 Finkelhor 1992 Hébert 2004 Kolko 1988 O'Donohue 1992 Reppucci 2005 Reppucci 1991 Roberts 1999 Sanderson 2004 Wurtele 2002 Wurtele 1987b |

Mikton 2009 |

Evaluations of discrete programmes have been limited to authors assessing and reporting on one or more of five measures: (i) knowledge gains, (ii) skills gains, (iii) sexual abuse disclosures, (iv) negative programme effects or harms, and (v) subsequent incidence of child sexual abuse (Smallbone 2008). Consistent with previous reviews, the original Cochrane review found improvements in knowledge and protective behaviours (skills) among children who had received school‐based programmes (Zwi 2007). Findings on disclosures, harm, and retention of knowledge over time were inconclusive. As this was the most rigorous of the reviews ever conducted (Mikton 2009), and is the only review to include risk of bias analyses, the review also uncovered many methodological quality issues that warrant ongoing monitoring and review. This is important because the historical controversy over school‐based child sexual abuse prevention programmes is concentrated on two outcomes: programmes' actual effectiveness in preventing child sexual abuse, and concerns over negative programme effects (Finkelhor 2007). Evidence on programmes' effectiveness with regard to the fifth and arguably the most important measure, the degree to which programmes actually reduce the incidence of child sexual abuse, remains a pressing and unanswered empirical question that requires ongoing review.

It has been suggested that education programmes can cause harm to participating children and adolescents (Taal 1997). This is reported to be a common parental concern (Finkelhor 2007; Tutty 1993). Some studies report few or no evaluated negative effects on children (Tutty 1997), whereas others suggest potentially harmful sequelae. For example, some children report increased worry following programme participation (Finkelhor 1995c) and older children have been found to experience more negative feelings about non‐sexual physical touch (Taal 1997). Therefore, there is a need to rigorously evaluate the evidence for these programmes, both in terms of beneficial and harmful outcomes, and to update the current evidence base on programme effectiveness.

Objectives

To systematically assess evidence of the effectiveness of school‐based education programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse. Specifically, to assess whether: programmes are effective in improving students' protective behaviours and knowledge about sexual abuse prevention; behaviours and skills are retained over time; and participation results in disclosures of sexual abuse, produces harms, or both.

The original review and the current update do not address whether these programmes or other interventions have reduced the incidence and/or prevalence of child sexual abuse at the population level as reported by official records (e.g. from statutory child protection services, law enforcement, primary care, or hospital data), and/or community prevalence data (e.g. from self report surveys repeated at regular intervals). This objective may be incorporated in future review updates as research advances in this field.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies in the original review, and in this update, if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), cluster‐RCTs, or quasi‐RCTs where participants were allocated to the intervention or control group by day of the week, alphabetical order, or other sequential allocation such as class or school. In decision making for inclusion in the review, we focused on features of study design rather than design labels.

Types of participants

The study population comprised children (aged 5 to 12 years) and adolescents (aged 13 to 18 years) attending primary (elementary) or secondary (high) schools.

Types of interventions

Included interventions were school‐based education programmes focusing on knowledge of sexual abuse and sexual abuse prevention concepts, or skill acquisition in protective behaviours, or both, compared with no intervention or the standard school curriculum. For this update, we excluded: interventions for preventing relationship and dating violence, and sexually coercive peer relationships, as these were reviewed in another Cochrane review (Fellmeth 2013); interventions for abduction prevention, the aims of which did not clearly refer to prevention of child sexual abuse; interventions aimed broadly at child protection or personal safety in which it was not possible to isolate the effects of the sexual abuse component; and interventions set entirely in before‐ and after‐school programmes, and early childhood programmes that were not in schools (e.g. day‐care settings).

Types of outcome measures

Child outcome measures were:

protective behaviours (as measured by an independently scored simulation test);

knowledge of sexual abuse or knowledge of sexual abuse prevention concepts, or both (as measured by questionnaires or vignettes);

retention of protective behaviours over time;

retention of knowledge over time;

harm, manifest as parental or child anxiety or fear (as measured by questionnaires); and

disclosure of sexual abuse by child or adolescent during or after programmes (as measured by official records of student self reports to school staff, child protective services, or police).

Outcomes measured did not form criteria for inclusion in the review. We included studies meeting the inclusion criteria for types of study, participants, and interventions only.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We completed the most recent searches for this review update on 8 September 2014. We incorporated new search terms to describe recent concepts, such as child sexual abuse in online contexts, and the increasing use of terms such as 'exploitation' and 'victimisation' by researchers when describing child sexual abuse. Searches for the previous review were completed in August 2006. Where possible, we focused on finding new studies and identifying older studies added to databases since that time. We added five new sources (two trials registers, two conference proceedings indexes, and one source of open access dissertations), and searched these for all available years (see Appendix 1). Search strategies used for the original review are in Appendix 2. The list of the databases searched and the time period they cover (for the original review and for this review update) are listed below:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2014, Issue 8);

Ovid MEDLINE(R), 1946 to August Week 4, 2014;

EMBASE (OVID), 1980 to 2014 Week 36;

PsycINFO (OVID),1967 to September Week 1 2014;

CINAHL (EBSCOhost), 1937 to current;

Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), 1970 to 29 August 2014;

ERIC (EBSCOhost), 1966 to current;

Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), 1952 to current;

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science (CPCI‐S), 1990 to 29 August 2014;

Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Social Sciences & Humanities (CPCI‐SSH), 1990 to 29 August 2014;

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) 2014, Issue 3, part of theCochrane Library;

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/);

ICTRP (apps.who.int/trialsearch/);

Australasian Theses (via TROVE) (trove.nla.gov.au/);

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) (via SCIRUS) (ndltd.org/serviceproviders/scirus‐etd‐search); last searched September 2013, not available in September 2014.

Searching other resources

Other sources of information searched included the reference lists of previous systematic and narrative reviews, and reference lists of included studies. We also searched databases of programme evaluations such as the Promising Practices Network (RAND Corporation 2013), and Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development (CSPV 2013). To identify unpublished studies, we circulated requests via email to relevant listservs (e.g. Child‐Maltreatment‐Research‐Listerv).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We conducted selection of studies in three phases. In phase one, we imported titles and abstracts of articles identified in the searches into reference management software and review authors KZ and SW (2007 and 2009 searches), KW and KZ (2013 searches), and KW and AS (2014 searches) independently screened them. We excluded papers if they clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria (i.e. study design, participants, type of intervention, types of comparisons). In phase two, two review authors (KZ and SW in 2007; KZ and KW in 2013; KW and AS in 2014) independently screened the titles, abstracts, and methodology sections of papers appearing to meet inclusion criteria. In phase three, we retrieved the full text of studies meeting all inclusion criteria for data extraction and we linked together multiple reports of the same study (e.g. Blumberg 1991). One study was translated into English (Del Campo Sanchez 2006). In cases where agreement could not be reached during screening, we asked a third and fourth review author to independently assess the study against the inclusion criteria, and we resolved these cases via discussion and consensus.

Data extraction and management

For this update, we used an electronic data extraction proforma adapted from the checklist of items specified in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011, Table 7.3a). Two review authors (KZ and SW in 2007) independently performed data extraction. KW repeated data extraction for all 24 studies in 2013, with KZ extracting data independently for new studies in 2013. No data extraction was required in 2014 as no further studies met the inclusion criteria. The data were entered into RevMan by KZ (Review Manager 4.2 in 2007) and KW (Review Manager 5.2 in 2013), and independently checked for accuracy by a research assistant who was not involved in the review. We resolved discrepancies via discussion. We asked authors of studies in which methods of sequence generation, allocation concealment, or blinding were unclear to provide additional information (see Assessment of risk of bias in included studies). We contacted corresponding authors of studies with insufficient information to allow inclusion in meta‐analyses (Harvey 1988; Saslawsky 1986 in 2007; Chen 2012; Kraizer 1991 in 2013) and studies that used cluster‐randomisation (Dake 2003; see Unit of analysis issues) via email with a request to provide additional data. In some instances, authors were able to provide data as requested, however, the majority did not respond to requests. It is not possible to know for sure that all authors received our correspondence.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In the original review, two review authors (KZ, SW) independently assessed each included study. In the review update, the procedure was repeated by one review author (KW) who independently assessed risk of bias for all included studies and compared these results to those obtained in the original review, with KZ assessing risk of bias independently for new studies in 2013. KW repeated assessment of risk of bias after a six‐month interval. There were no discrepancies. We undertook no 'Risk of bias' assessment in 2014 as no further studies met the inclusion criteria. Review authors assessing risk of bias were not blinded to the names of the authors, institutions, journals, or results of studies.

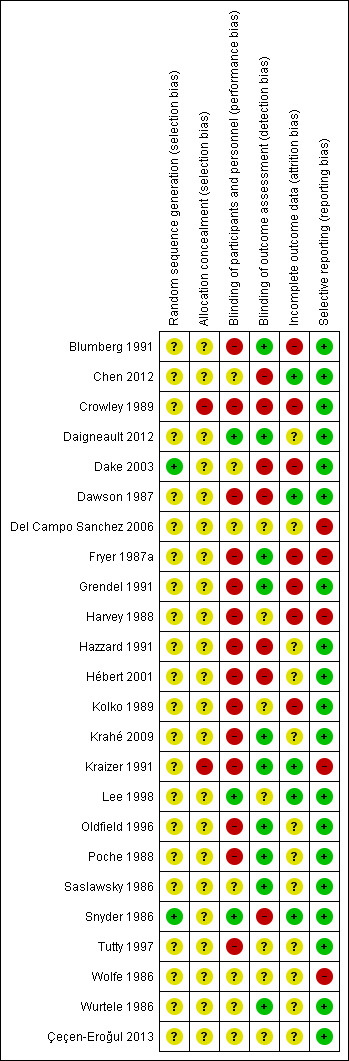

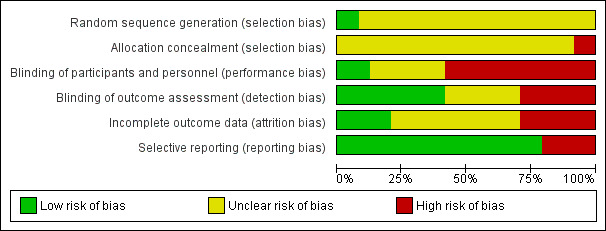

We assessed risk of bias using the seven domains on the Cochrane revised 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011, Table 8.5a): (i) random sequence generation; (ii) allocation concealment; (iii) blinding of participants and personnel; (iv) blinding of outcome assessment; (v) incomplete outcome data; (vi) selective reporting; and (vii) other sources of bias. We assessed included studies on each domain as 'low risk', 'high risk', or 'unclear risk' of bias. We made judgements by answering 'yes' (assessed as low risk of bias), 'no' (assessed as high risk of bias) or 'uncertain' (assessed as unclear risk of bias) to pre‐specified questions for each domain. We used verbatim text from study reports as support for each judgement of risk wherever possible. We entered information into RevMan and summarised it in a 'Risk of bias' table for each included study. We generated two summary figures: a 'Risk of bias' summary (Figure 1) visually depicting judgements across all studies, and a 'Risk of bias' graph (Figure 2) illustrating the proportion of studies for each risk of bias criterion. Risk of bias domains are detailed below.

1.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Random sequence generation (selection bias)

Description: The method used to generate the allocation sequence was described in sufficient detail to enable assessment of the extent to which it could produce comparable groups. In other words, a rule, based on some chance process, was adequately applied.

Questions: Do study authors make an explicit statement about random assignment? What methods were used to randomly assign participants to intervention and control groups?

Judgement: Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Allocation concealment (selection bias)

Description: The method used to conceal the allocation sequence was described in sufficient detail to enable assessment of whether the assignment of participants to groups could have been predicted ahead of time, or during the assignment process. Upcoming allocations were concealed from those allocating participants to groups.

Questions: Do the study authors report a method of concealing allocation of participants to intervention or control groups? Is there evidence that the method was potentially unconcealed?

Judgement: Was allocation adequately concealed?

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias)

Description: The measures used to blind study participants and personnel (such as programme facilitators or teachers) from knowledge of participant intervention or control group membership was described in sufficient detail to enable assessment of the effects of this knowledge on study outcomes.

Questions: Do study authors report procedures for blinding? What specific blinding procedures were used? Was blinding achievable for this type of intervention?

Judgement: Was participant and personnel knowledge of the allocation to intervention or control group adequately withheld?

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias)

Description: The measures used to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of participant intervention or control group membership were described in sufficient detail to enable assessment of the effects of this knowledge on outcome assessment or data collection, or both.

Questions: Do study authors report procedures for blinding of individuals responsible for outcome assessment or data collection, or both? What specific blinding procedures were used? Was blinding achievable for this type of intervention?

Judgement: Was outcome assessors' knowledge of the allocation to intervention or control group adequately withheld?

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Description: Complete outcome data are reported for each main outcome in sufficient detail to enable assessment of group differences owing to missing data. Complete outcome data include: attrition, exclusions, numbers of participants in each intervention and control group compared with the total number of participants randomised, and reasons for attrition and exclusions.

Questions: Do study authors report attrition, exclusions, numbers of participants in each intervention and control group compared with the total number of participants randomised, and reasons for attrition and exclusions? Are imputation methods explained?

Judgement: Were outcome data adequately addressed?

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

Description: The extent of outcome reporting is sufficient to enable assessment of the possibility of selective outcome reporting, that is, reporting of some outcomes and not others depending on the nature and direction of results.

Questions: Do study authors report complete outcome data that match the aims or hypotheses of the study? Do study authors report on all pre‐specified outcomes of interest?

Judgement: Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Other sources of bias

Description: Any other important concerns about bias not addressed in other domains.

Questions: Do study authors report studies in sufficient detail to enable assessment of other important risks of bias (e.g. related to the specific study design, extreme baseline imbalances, or contamination effects)?

Judgement: Was the study free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

According to the review protocol (Zwi 2003), for individual trials we planned to report the risk ratio (RR) and risk difference (RD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MD) with 95% CI for continuous variables. For the meta‐analysis, where possible, we planned to report the RR and RD with 95% CI for dichotomous outcomes and MD with 95% CI for continuous variables. Elsewhere in the protocol (e.g. p 4) odds ratios (OR) are also mentioned.

In the original review, and in this review update, we reported the summary of effect for dichotomous outcomes as an OR with 95% CI. Odds ratios are the statistic used most often in this field. For continuous outcomes this was to be reported as the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI. Standardised mean differences are appropriate for data synthesis where different outcome measures are used across studies.

Unit of analysis issues

In the review protocol (Zwi 2003), in the case of cluster‐RCTs, we planned to adjust for unit of analysis errors where the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was available. In the original review, and in this review update, some included studies involved cluster‐randomisation at the level of the class, school, or district. However, ICCs were not reported in the studies, nor were they available from study authors. No published ICC for school‐based child sexual abuse prevention interventions could be found. We noted that estimates of 0.1 and 0.2 had been used in a review of school‐based violence prevention programmes (Mytton 2006), based on the rationale for a published ICC of 0.15 for similar trials (CPPRG 1999b in Mytton 2006), and was considered a plausible yet conservative estimate for the impact of clustering at the classroom level (Schochet 2008). We reasoned that a suitably conservative approach would be to use the extremes of ICC 0.1 and 0.2 to calculate a design effect for each cluster‐RCT according to the formula given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011, Section 16.3.4) which is: 1 + (mean cluster size ‐ 1) ICC. We weighted these using the generic inverse variance function and used random‐effect models.

Some studies included in this review had multiple intervention groups (Blumberg 1991; Crowley 1989; Dawson 1987; Krahé 2009; Poche 1988). In these cases, we combined all relevant intervention groups into a single group, and all relevant control groups into a single group. Using the tools available in Review Manager 5.2, we combined means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous outcomes, and summed sample sizes and number of outcomes across groups for dichotomous outcomes. This enabled us to make comparisons between groups using pair‐wise comparisons without risk of double‐counting participants.

Dealing with missing data

Requirements for dealing with missing data in Cochrane Reviews have changed since the protocol for this review was written (Zwi 2003). We identified several types of missing data in this review update: missing outcomes, missing summary data, and missing participants. For missing outcomes (e.g. disclosures, adverse outcomes) and missing summary data (i.e. group size totals, means, SDs), we contacted corresponding study authors to provide the outstanding data. Some authors responded helpfully to these requests, but data could only be provided for the most recent studies; in other cases, data had been collected over two decades ago and were no longer available. In some cases, authors did not respond. If data remained unavailable after these processes, we excluded these studies from the analyses. For missing participants, we reported the attrition rate wherever possible in the 'Risk of bias' tables beneath the Characteristics of included studies table.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity (study diversity) visually and by examining the I² statistic (Higgins 2002), a quantity which describes the proportion of variation in point estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. We supplemented this with a statistical test of homogeneity to determine the strength of evidence for genuine heterogeneity using a significance level of P value > 0.05.

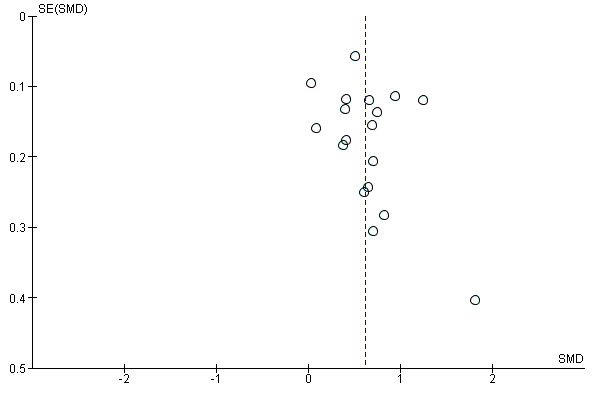

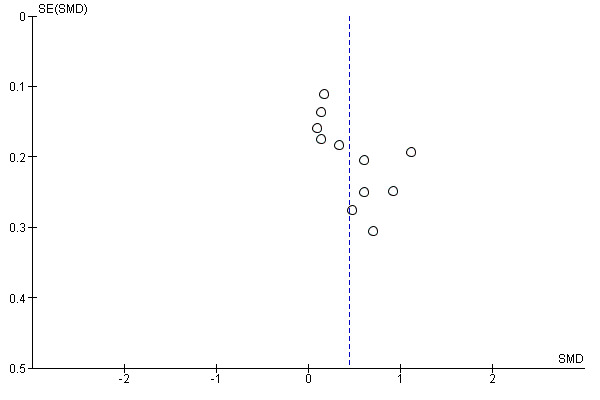

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess reporting biases, we used two approaches to investigate the relationship between effect size and sample size (Borenstein 2009). We drew fixed‐effect forest plots with studies plotted according to weight (i.e. from most to least precise). We noted any trend towards greater effect sizes at the bottom of the plots indicative of bias attributable to missing studies. We also drew fixed‐effect funnel plots and checked them for asymmetry indicating the presence of publication bias. In both approaches, trends or asymmetry could be due to publication or related biases (e.g. language bias, availability bias, citation bias) or due to genuine differences between small and large trials (Borenstein 2009; Egger 1997). If a relationship was identified, we further examined differences between studies as a possible explanation along with comparisons by source (e.g. peer‐reviewed journals; theses). We planned to conduct these analyses only when there was a reasonable number of studies (more than 10) and a reasonable amount of dispersion in sample sizes. To reduce the effects of publication bias, in the review update, we made efforts to retrieve the full texts of unpublished trials (e.g. theses). This was made easier by virtue of the fact that many had been made available on electronic databases since our previous searches were conducted and document delivery services had improved.

Data synthesis

We synthesised the data using tools provided in Review Manger (RevMan) 5.2 (RevMan 2012). We assessed the appropriateness of combining studies based on sufficient comparability with respect to: the type of intervention, the type of outcome measures, and the nominated data collection points pre‐ and post‐intervention. We calculated summary statistics (OR for dichotomous data and SMD for continuous data) with 95% CIs for each study. We had intended to use a fixed effect model to combine data in the first instance and then to adopt a random effects model where the I square value exceeded 30%. On further consideration of the differences between the included studies in terms of their setting and intervention, we decided instead to adopt a random effects model to combine data. In all cases, we generated pooled estimates for those studies for which complete statistical data were available or could be derived (i.e. counts and proportions for dichotomous data, and means and SDs for continuous data). Forest plots are presented for each of the pooled estimates. In all cases, we corrected for small sample size bias by using Hedges' g, which is the default in Review Manager (RevMan) 5.2 (RevMan 2012).

We planned to conduct analyses on the six outcomes nominated above: (i) protective behaviours; (ii) knowledge of sexual abuse or knowledge of sexual abuse prevention concepts, or both; (iii) retention of protective behaviours over time; (iv) retention of knowledge over time; (v) parental or child anxiety or fear; (vi) disclosure of sexual abuse. To manage subtle differences in outcome measurement for (ii) (knowledge), we created subgroups according to the category of measurement instrument used (i.e. questionnaire‐based knowledge or vignette‐based knowledge). There were insufficient data to proceed with analysis for retention of protective behaviours over time. No studies measured parental anxiety or fear.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In the review protocol (Zwi 2003), we specified the conduct of subgroup analyses to assess the impact of clinically relevant differences: (i) in the interventions (e.g. passive or active involvement of participants); and (ii) between groups of participants (e.g. gender, school setting). We did not conduct subgroup analyses because there was insufficient information provided in the included studies about issues that were hypothesised as being relevant for subgroup analysis, for example, studies did not always provide a breakdown of student gender by intervention group. Further, upon close scrutiny, interventions did not appear to fit an active/passive dichotomy with many having multiple components of both active and passive types (e.g. a video or DVD presentation may at times require children to sit still and listen, and at other times, to respond, chant, sing, or move). Further, there were insufficient numbers of studies to allow for meaningful comparisons. This will be elaborated further below.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analysis to explore the extent to which results were influenced by risk of bias. We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses removing from the analyses studies with high risk of bias for: (i) allocation concealment (selection bias); (ii) blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias); (iii) incomplete outcome data (attrition of over 20%), and (iv) selective reporting (reporting bias). We also conducted sensitivity analyses to determine the impact of unit of analysis errors, arising from inadequate adjustment for cluster‐randomisation in published results.

Rating the quality of the evidence

We rated the quality of the evidence for our main outcomes according to methods for rating evidence from randomised controlled trial developed by the GRADE working group (http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). For each outcome of interest the evidence started at high quality and could be downgraded to moderate, low or very low quality after consideration of the possible impact of risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness and publication bias on our confidence in the effects of intervention.

We have presented results for the primary analyses, quality ratings, and explanations for downgrading any decisions for the following outcomes in a 'Summary of Findings' table:

Protective behaviours (self protective events measured using a stranger simulation test immediately post intervention)

Questionnaire‐based knowledge (factual knowledge measured by assessing responses to items on a questionnaire or multi‐choice test, immediately post intervention)

Vignette‐based knowledge (applied knowledge measured by assessing responses to hypothetical scenarios, immediately post intervention)

Harm (measured using anxiety or fear questionnaires)

Disclosures (of past or current child sexual abuse made during or after programme completion)

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

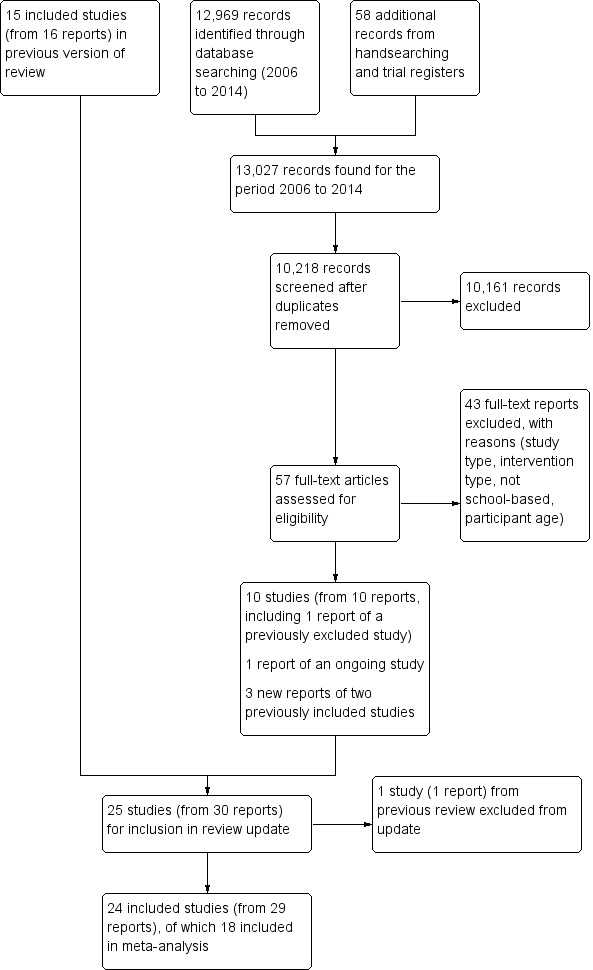

For this update, we searched the period from August 2006 to September 2014 (see Appendix 1). We identified a total of 12,969 records through database searching and a further 58 records from other sources. After duplicates were removed, we screened 10,218 records and excluded 10,161 records. We retrieved and evaluated the full‐text reports of the remaining 57 records for eligibility. Of these, we excluded 43 reports, with reasons reported in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. From the remaining papers, we identified: 10 new included studies, one of which was translated from Spanish into English (Del Campo Sanchez 2006); three additional reports of two included studies from the previous review (Blumberg 1991; Fryer 1987b); and one ongoing study (NCT02181647).

Searches for the original review covered the period up to August 2006 (Appendix 2). The previous review was based on 15 included studies. We excluded one of the previously included studies from this update (Pacifici 2001), because we reassessed it as not meeting the eligibility criterion for type of intervention, being focused on sexual violence prevention in the context of dating relationships for adolescents (see Fellmeth 2013), rather than explicitly on knowledge of child sexual abuse and its prevention. In total, this updated review reports on a total of 24 unique trials reported in 29 papers (Figure 3).

3.

Study flow diagram for searches 2006‐2014

Included studies

The Characteristics of included studies table summarise details for each of the 24 included studies.

Design

Of the 24 included studies, seven were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Chen 2012; Fryer 1987a; Harvey 1988; Lee 1998; Tutty 1997; Wurtele 1986; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013), 11 were cluster‐RCTs (Blumberg 1991; Dake 2003; Dawson 1987; Grendel 1991; Hazzard 1991; Kolko 1989; Krahé 2009; Kraizer 1991; Oldfield 1996; Poche 1988; Wolfe 1986), and six were quasi‐RCTs (Crowley 1989; Daigneault 2012; Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Hébert 2001; Saslawsky 1986; Snyder 1986). Of the quasi‐RCTs, all but Del Campo Sanchez 2006 used a Solomon four‐group design (Campbell 1963; Solomon 1949).

The unit of randomisation in 14 studies was clusters (classrooms, schools, or districts). Of these, 11 were cluster‐RCTs (as above) and three were quasi‐RCTs (Crowley 1989; Daigneault 2012; Hébert 2001). In 10 trials the unit of randomisation was individual school students. Of these, seven were RCTs (as above) and three were quasi‐RCTs (Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Saslawsky 1986; Snyder 1986).

Eighteen studies allocated participants to one of two groups, the intervention (school‐based sexual abuse prevention programme) and a control group (no programme or wait‐listed). Four studies allocated participants to one of three groups, two of which were intervention groups comprising slight variations of the same programme (Krahé 2009; Kraizer 1991), or different programmes (Blumberg 1991; Del Campo Sanchez 2006). Three studies allocated participants to one of four groups, three of which were intervention groups comprising programme variations (Hazzard 1991; Poche 1988; Wurtele 1986).

Location

Sixteen studies were conducted in the USA. Three studies were conducted in Canada (Daigneault 2012; Hébert 2001; Tutty 1997). One study apiece was conducted in China (Lee 1998), Germany (Krahé 2009), Spain (Del Campo Sanchez 2006), Taiwan (Chen 2012), and Turkey (Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013).

Sample sizes

The total number of participants randomised in cluster‐RCTs ranged from 74 (Poche 1988) to 1269 (Oldfield 1996). The total number of students randomised in trials with individuals as the unit of randomisation ranged from 46 (Chen 2012) to 382 (Del Campo Sanchez 2006). The number of participants in the 13 cluster‐RCTs ranged from 74 (Poche 1988) to 1269 (Oldfield 1996), and in the nine RCTs in which participants were randomised as individuals, ranged from 36 (Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013) to 231 (Tutty 1997). Eleven studies (including nine cluster‐RCTs and two studies in which participants were randomised as individuals) each included more than 200 participants.

Settings

All studies were conducted in school settings: 23 in primary (elementary) schools and one in a special school for adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Only six studies were undertaken in single grades: one in kindergarten (Harvey 1988), one in grade one (Grendel 1991), two in grade three (Dake 2003; Kolko 1989), and two in grade four (Snyder 1986; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013). All other studies involved various combinations of grades to which there was no discernable pattern. It is possible to categorise the studies into three broad age group blocks as follows: (i) 10 studies with younger participants from kindergarten to grade three (Blumberg 1991; Dake 2003; Fryer 1987a; Grendel 1991; Harvey 1988; Hébert 2001; Kolko 1989; Krahé 2009; Kraizer 1991; Poche 1988); (ii) eight studies with older participants from grade four upwards (Crowley 1989; Dawson 1987; Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Hazzard 1991; Lee 1998; Snyder 1986; Wolfe 1986; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013); and (iii) six studies with younger and older participants together (Chen 2012; Daigneault 2012; Oldfield 1996; Saslawsky 1986; Tutty 1997; Wurtele 1986).

None of the included studies were conducted in secondary (high) school settings.

Participants

A total of 5802 school‐aged participants were included in the 24 trials. Study participants' mean ages at baseline in the included studies ranged from 5.8 years (Harvey 1988) to 13.44 years (Lee 1998). Authors of eight studies did not report the mean age of participants at baseline (Crowley 1989; Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Fryer 1987a; Hazzard 1991; Kraizer 1991; Oldfield 1996; Tutty 1997; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013).

The proportion of females in the included studies ranged from 45% (Poche 1988; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013) to 55% (Crowley 1989). One trial enrolled female participants only (Lee 1998). Gender‐specific proportions were not reported in five studies (Chen 2012; Daigneault 2012; Fryer 1987a; Harvey 1988; Kraizer 1991).

Ethnicity data were reported in 13 studies. Two studies reported 100% Chinese participants (Chen 2012; Lee 1998). In five studies the predominant ethnicity reported was White or Caucasian comprising 74% to 97% of participants (Grendel 1991; Oldfield 1996; Poche 1988; Snyder 1986; Tutty 1997). Six studies reported diverse samples comprising participants from different combinations of White or Caucasian, Black or African, Hispanic, Asian, Middle Eastern, or 'other' backgrounds (Blumberg 1991; Daigneault 2012; Dake 2003; Dawson 1987; Harvey 1988; Hazzard 1991). In these six studies, the proportion of non‐White participants ranged from 32% (Hazzard 1991) to 66% (Dake 2003). One of these studies reported country of birth rather than ethnicity (Daigneault 2012). Ethnicity data were not reported in the 10 remaining studies (Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Fryer 1987a; Hébert 2001; Kolko 1989; Krahé 2009; Kraizer 1991; Saslawsky 1986; Wolfe 1986; Wurtele 1986; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013).

Parental socioeconomic position was not reported in any study. Non‐empirical markers for study locations were used such as "low socioeconomic" (e.g. Daigneault 2012), "middle income" (Grendel 1991; Hébert 2001; Poche 1988), or "lower to middle income" (Saslawsky 1986; Wolfe 1986; Wurtele 1986).

Religious background of study participants was not reported in any study. One study reported data collection in religious schools in Spain (Del Campo Sanchez 2006).

Participants' school achievement data (e.g. grades) at baseline were not reported in any study. In one study, the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) (Dunn 1981) was used to assess children's receptive and expressive language ability at baseline (Fryer 1987a), and, in another study, Raven's Standard Progressive Matrices (RSPM) (Raven 1960) was used as a measure of general intellectual ability at baseline (Lee 1998); in this study, participants were adolescent Chinese females with mild intellectual disabilities from four special schools in Hong Kong, China.

None of the studies enrolled participants on the basis of previously reported abuse.

Interventions

In all 24 trials, interventions focused specifically on child sexual abuse prevention. The targets of the interventions were school‐aged children who were taught knowledge of sexual abuse, sexual abuse prevention concepts, and/or skill acquisition in self protective behaviours.

A wide range of previously published, modified, and new prevention programmes were used in the trials. Fifteen discrete programmes were identified including: Behavioural Skills Training (BST) (Lee 1998; Wurtele 1986), Good Touch/Bad Touch (Crowley 1989; Harvey 1988; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013), Red Flag/Green Flag (Chen 2012; Kolko 1989), Child Abuse Primary Prevention Program (CAPPP) (Blumberg 1991), Child Sexual Abuse Prevention Program (Grendel 1991), Children Need to Know Personal Safety Training Programme (Fryer 1987a), ESPACE (Daigneault 2012; Hébert 2001), Good Secrets/Bad Secrets (Snyder 1986), No Child's Play (Krahé 2009), Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse Program (Del Campo Sanchez 2006), Project TRUST (Oldfield 1996), Safe Child Program (Kraizer 1991), Stop, Tell someone, Own your body, Protect yourself (STOP!) (Blumberg 1991), TOUCH (Saslawsky 1986), and Who Do You Tell? (Tutty 1997).

In two trials, combinations of programmes were used in interventions: TOUCH plus BST (Wurtele 1986), and Feeling Yes, Feeling No plus Spiderman and Power Pack Comic Book (Hazzard 1991). Four trials did not identify the programme used (Dake 2003; Dawson 1987; Poche 1988; Wolfe 1986).

Contents of or topics covered in the intervention programmes were not consistently reported in the majority of trials. We could discern that programmes were multifaceted with integrated content, including teaching of safety rules ranging from two to six rules (e.g. Grendel 1991; Poche 1988), with the most common being four rules (Blumberg 1991; Fryer 1987a; Lee 1998; Saslawsky 1986; Wurtele 1986), and prevention concepts such as body ownership, private parts, distinguishing appropriate and inappropriate touches, distinguishing types of secrets, and whom to tell. Programme content was not detailed in eight studies (Crowley 1989; Dake 2003; Dawson 1987; Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Hazzard 1991; Krahé 2009; Snyder 1986; Tutty 1997). Four studies also included abduction prevention content (Chen 2012; Fryer 1987a; Kraizer 1991; Poche 1988).

Teaching methods were more clearly reported than programme contents. Rehearsal, practice, or role‐play was mentioned in 12 studies (Blumberg 1991; Daigneault 2012; Fryer 1987a; Harvey 1988; Hébert 2001; Kraizer 1991; Lee 1998; Poche 1988; Snyder 1986; Tutty 1997; Wurtele 1986; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013), discussion in 10 studies (Blumberg 1991; Grendel 1991; Hazzard 1991; Hébert 2001; Oldfield 1996; Saslawsky 1986; Snyder 1986; Tutty 1997; Wolfe 1986; Wurtele 1986), and modelling in six studies (Daigneault 2012; Hébert 2001; Lee 1998; Saslawsky 1986; Wurtele 1986; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013). A specific suite of teaching strategies was designated in four studies, including instruction, modelling, rehearsal, social reinforcement, shaping, feedback, and group mastery (Chen 2012; Lee 1998; Saslawsky 1986; Wurtele 1986). The strategy review, which involved revisiting previous content and summarising new content, was nominated in one study (Grendel 1991). Three studies did not report teaching methods (Crowley 1989; Dake 2003; Del Campo Sanchez 2006).

Programme delivery formats were reported in the majority of studies. These included film, video, and DVD formats in 12 studies (Blumberg 1991; Dawson 1987; Grendel 1991; Harvey 1988; Hazzard 1991; Kolko 1989; Krahé 2009; Poche 1988; Saslawsky 1986; Tutty 1997; Wurtele 1986; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013), plays in three studies (Krahé 2009; Oldfield 1996; Wolfe 1986), and multimedia in two studies (Blumberg 1991; Hazzard 1991). Additional resources included songs (Blumberg 1991; Harvey 1988; Krahé 2009), puppets (Blumberg 1991; Harvey 1988), comics (Dawson 1987; Hazzard 1991), a colouring book (Kolko 1989), a storybook (Harvey 1988), and games (Harvey 1988). Three studies did not nominate programme delivery formats (Crowley 1989; Dake 2003; Del Campo Sanchez 2006).

No programmes were delivered electronically in web‐ or computer‐based formats.

The duration of the intervention programmes in the included trials ranged from a single 45‐minute session (Oldfield 1996) to eight 20‐minute sessions on consecutive days (Fryer 1987a). Fourteen interventions were brief (i.e. less than 90 minutes total duration) (Blumberg 1991; Crowley 1989; Dawson 1987; Grendel 1991; Harvey 1988; Hébert 2001; Kolko 1989; Krahé 2009; Lee 1998; Oldfield 1996; Poche 1988; Saslawsky 1986; Wolfe 1986; Wurtele 1986), and the remainder were longer, lasting from 90 to 180 minutes in total duration.

In 17 trials, the effectiveness of prevention programmes was compared to that of a wait‐listed control group. In the seven remaining studies, the control group interventions were as follows: discussion about self concept (Saslawsky 1986; Wurtele 1986); multimedia presentation with no child abuse content (Harvey 1988); fire safety (Blumberg 1991); fire or water safety (Hazzard 1991); attention control programme (Lee 1998); and a game of hangman (Snyder 1986).

All programmes were delivered on school premises and during school hours, apart from one study in which the programme was delivered in the morning, before school classes began (Chen 2012).

Outcomes

In this section we summarise six outcome measures of interest that were addressed in the included studies: (i) protective behaviours; (ii) knowledge (questionnaire‐based knowledge and vignette‐based knowledge); (iii) retention of protective behaviours over time; (iv) retention of knowledge over time; (v) harm (manifest as parent or child anxiety or fear); and (vi) disclosures. This information is presented in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Protective behaviours

Three studies measured change in behaviour using a simulated abuse situation and scored the child's response to the situation (Fryer 1987a; Kraizer 1991; Poche 1988). All three studies used a version of a stranger simulation test to assess children's self protective skills (i.e. whether children could follow the rules they were taught and not interact if approached by a stranger).

Knowledge

Knowledge outcome measures varied between studies. Knowledge measures used were: (i) questionnaire‐based measures, or (ii) vignette‐based measures that used scenarios or visual prompts to elicit a response from the child about safe behaviour in that situation. Only one study did not measure knowledge (Poche 1988), and one study used a vignette‐based measure only (Krahé 2009). Ten studies used both vignette‐ and questionnaire‐based measures (Blumberg 1991; Chen 2012; Daigneault 2012; Grendel 1991; Harvey 1988; Hazzard 1991; Hébert 2001; Lee 1998; Saslawsky 1986; Wurtele 1986). Three studies used a second questionnaire‐based measure to establish construct validity (Chen 2012; Crowley 1989; Del Campo Sanchez 2006).

The use of more than one measure by studies to assess knowledge gain was not anticipated at the outset of this systematic review. The two types of measures were administered differently. Questionnaire‐based measures were administered as self completed measures via individual or group administration. Vignette measures were administered by interview. The different methods of administration and the type of response required from the child means that these two outcomes may measure different aspects of children's knowledge; therefore, we considered them as separate knowledge outcomes.

Knowledge ‐ questionnaire‐based measures

Questionnaire‐based knowledge measures were used in 21 studies. The Personal Safety Questionnaire (PSQ) was used in six (Crowley 1989; Grendel 1991; Hébert 2001; Lee 1998; Saslawsky 1986; Wurtele 1986). The Children's Knowledge of Abuse Questionnaire (CKAQ) and versions thereof (CKAQ‐R, CKAQ‐IIIR) were used in five studies (Daigneault 2012; Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Hébert 2001; Oldfield 1996; Tutty 1997), and the Children Need to Know Knowledge/Attitude Test (CNTKKAT) was used in two (Fryer 1987a; Kraizer 1981). Other custom‐made knowledge scales were also used (Blumberg 1991; Chen 2012; Crowley 1989; Dake 2003; Dawson 1987; Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Harvey 1988; Hazzard 1991; Kolko 1989; Snyder 1986; Wolfe 1986; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013).

Knowledge ‐ vignette‐based measures

Vignette‐based knowledge measures were used in 11 studies. The What If Situations Test (WIST), comprising six brief verbal vignettes, was used in four studies (Grendel 1991; Lee 1998; Saslawsky 1986; Wurtele 1986). A Chinese version of the WIST was used in one study (Chen 2012), and a French version in another (Daigneault 2012). The Touch Discrimination Task (TDT), based on the WIST and comprising seven verbal vignettes, was used in one study (Blumberg 1991), and an unnamed measure comprising 10 picture vignettes featuring good touch and sexually abusive touch were used in another study (Harvey 1988). Eight cartoon picture vignettes and stories were used in Krahé 2009. Video vignettes entitled What Would You Do? (WWYD) and comprising six 30‐second scenes were used by Hazzard 1991, and an unnamed video measure with five situations was used by Hébert 2001.

Retention of protective behaviours over time

Retention of self protective skills was measured in three studies at one month (Poche 1988), and six months (Fryer 1987a; Kraizer 1991). In Fryer 1987a, no comparison with the control group was available at follow‐up because the control groups had been exposed to the intervention. In Kraizer 1991, data were not reported. In Poche 1988, there was substantial loss to follow‐up.

All three studies measured post‐test protective behaviours within one to two days following the intervention. One study reported following up with assessment of protective behaviours one month after the intervention (Poche 1988), and the two other studies reported following up six months after the intervention (Fryer 1987a; Kraizer 1991). However, follow‐up data were published only for Fryer 1987a; data were not published for Kraizer 1991, and Poche 1988 reported significant loss to follow‐up with only nine of 23 children available for measurement.

Retention of knowledge over time

All of the 21 studies measuring post‐test questionnaire‐based knowledge did so within a two‐week period following intervention. Ten studies also reported short‐term knowledge outcomes one to three months following intervention (Crowley 1989; Dawson 1987; Harvey 1988; Hazzard 1991; Hébert 2001; Lee 1998; Poche 1988; Saslawsky 1986; Wurtele 1986; Ҫeҫen‐Eroğul 2013). One study reported knowledge outcomes at five months (Blumberg 1991), three studies at six months (Fryer 1987a; Kolko 1989; Kraizer 1991), and two studies at eight months (Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Krahé 2009). One study measured long‐term outcomes at 12 months (Hazzard 1991). One study measured long‐term outcomes in "the second year of the study" (Daigneault 2012, p 527), however the precise timing was not reported.

For most studies, no comparison with the control group was available at follow‐up because the control groups had been exposed to the intervention by then. Complete data (for intervention and control groups) were reported in only four studies (Dawson 1987; Hazzard 1991; Kolko 1989; Lee 1998).

Harm ‐ parental or child anxiety or fear

No studies measured parental anxiety or fear. Parent satisfaction questionnaires were used in five studies (Grendel 1991; Hazzard 1991; Hébert 2001; Tutty 1997; Wurtele 1986).

Six studies measured child anxiety or fear via child report (Blumberg 1991; Daigneault 2012; Dawson 1987; Hazzard 1991; Kraizer 1991; Lee 1998), and four studies via parent report (Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Hazzard 1991; Hébert 2001; Tutty 1997). Instruments used with children were the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) (Dawson 1987; Hazzard 1991; Oldfield 1996), the Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) (Oldfield 1996), and the Fear Assessment Thermometer Scale (Lee 1998). One study used a "children's feelings of safety" measure (Daigneault 2012, p 530). Instruments used with parents were adapted from the Parental Perception Questionnaire (PPQ) (Miller‐Perrin 1986), a 16‐item measure in which parents rate how often they observed negative and positive behaviours. Included studies variously referred to the measure as a 'parent observation' measure (e.g. Tutty 1997) and a 'side effects' scale (e.g. Del Campo Sanchez 2006).

Disclosures

Children's disclosures of child sexual abuse during or following intervention were reported by five studies (Blumberg 1991; Del Campo Sanchez 2006; Hazzard 1991; Kolko 1989; Oldfield 1996). To record disclosures, two studies used a data collection form completed by staff at the school (Hazzard 1991; Oldfield 1996). Two other studies conducted child protective services (CPS) file searches (Blumberg 1991; Kolko 1989). Blumberg 1991 conducted follow‐up CPS searches at 15 months post‐intervention.

Excluded studies

We excluded 55 studies because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. We excluded 36 studies on the basis of study type (13 pre‐test and post‐test studies without control groups; 11 controlled before‐and‐after studies without random assignment; five post‐test only studies; five quasi‐experimental studies without random assignment; one cross‐sectional comparative study; and one comparative group design). We excluded 14 studies because the intervention was not primarily about child sexual abuse prevention, but was about dating and relationship violence, gendered violence, or sexual harassment in the context of partner relationships (seven of these studies were cited in the Cochrane Review by Fellmeth 2013, including Pacifici 2001, which was included in the original review) or abduction prevention, the aims of which did not mention prevention of child sexual abuse. We excluded four studies because they were not school‐based and one study because participants were outside the age criteria.

Reasons for exclusion are detailed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Twenty studies stated that individuals or groups (classes, schools, or districts) were "randomised", "randomly allocated", or "randomly assigned" to groups, but provided no detail about how the random sequence was generated. Three further studies described a classic experimental design, but did not report details about random assignment (Dake 2003; Kolko 1989; Kraizer 1991). We classified all of these studies as unclear risk of bias. One study reported a random component in the sequence generation, coin tossing (Snyder 1986), and we classified it as low risk of bias. In one study, evidence of computerised randomisation was provided after author contact (Dake 2003). We re‐classified this study as low risk of bias.

Allocation concealment