Abstract

Unprecedented financial and emotional stress, paired with measures to slow the spread of COVID-19 (e.g., school closures), place youth at risk for experiencing increased rates of abuse. We analyzed data from New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services to investigate the frequency of child maltreatment prevention service case openings during this time. Longitudinal counts of case openings were compiled for January through June of the years 2014–2020. An independent samples Kruskal–Wallis H-test suggested that pre-quarantine case openings were significantly larger than case openings during quarantine. To account for the possible influence of other historical events impacting data, a secondary Kruskal–Wallis H-test was conducted comparing only the 4 months of quarantine data available to the 4 months immediately preceding quarantine orders. The second independent samples Kruskal–Wallis H-test again suggested that pre-quarantine case openings were significantly larger than case openings during quarantine. A Poisson regression model further supported these findings, estimating that the odds of opening a new child maltreatment prevention case during quarantine declined by 49.17%. These findings highlight the severity of COVID-19 impacts on child maltreatment services and the gap between demand for services and service accessibility. We conclude with recommendations for local governments, community members, and practitioners.

Keywords: COVID-19, child maltreatment, access to services, stress and abuse, global crises, children and families, family violence

Child Maltreatment Prevention Service Cases are Significantly Reduced During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Investigation into Unintended Consequences of Quarantine

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a highly contagious novel coronavirus causing worldwide illness and death. The disease is thought to have begun in December of 2019 (Rodriguez-Morales et al., 2020), and reports of its presence in the United States began in January of 2020 (Burke, 2020). Nearly every country has reported being impacted by the novel coronavirus, with 27.3 million cases reported worldwide as of September 2020 (John Hopkins School of Medicine, 2021). By March 2020, most of the United States had been placed under a mandatory quarantine to slow the increasing spread of the virus. Much of the United States remains under some level of restrictions (e.g., mask wearing, social distancing, and remote work/school) as of September 2020. This is particularly apparent in large urban centers.

Due to SARS-CoV-2, referred to herein as COVID-19, individuals report that they are experiencing a number of adverse mental health effects due to social isolation measures (Rossi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020). In addition to social isolation, people are coping with other circumstances caused by COVID-19 that are traditionally linked to harmful sequelae, including, but not limited to job loss and unemployment (Coibion et al., 2020), global economic recession (Fernandes, 2020), grief (Wallace et al., 2020), and anxiety about infection (Ho et al., 2020). An unintended consequence that may occur as a result of the interactions amongst these unique conditions is family violence. Although the COVID-19 pandemic is novel and research is in early phases, a wealth of literature exists examining the association between other mass traumatic events, like natural disasters, and child maltreatment. Seddighi et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review that revealed that children are more likely to be victims of family violence, during disasters, due to the risk of families being under more psychological and economic pressures

Circumstances surrounding COVID-19 may be uniquely related to an increase in child maltreatment as families are spending more time inside, at home. For instance, youth experiencing family violence who would typically be identified by school personnel (Golbertstein et al., 2020), or who reduce their time in a household with domestic violence or child abuse through attending school and after-school programs, are now quarantined in these homes. Rosenthal and Thompson (2020) report that on holidays and during summer, incidents of child maltreatment tend to increase. Providing further support for the relationship between stress, school closures, and child maltreatment, Bright et al. (2019) found that when student report cards were released on Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, or Thursdays, there were no significant increases in instances of child abuse; however, when report cards were released on a Friday, there were four times as many substantiated incidents of child abuse. Thus, it appears that youth and families are particularly vulnerable to experiencing violence during school closures (i.e., holidays, summer, and weekends), which may also include closures due to COVID-19 quarantine. In addition to youth and their parents spending more time at home, parents may be engaging in maladaptive coping mechanisms due to stress, such as substance use, which then makes them more susceptible to committing violence. With many schools operating remotely for the 2020–2021 school year, family violence advocates are concerned about the increased potential for harm (Usher et al., 2020).

It is critical to determine whether families are receiving preventive services during this time when parents and their children are sheltering together at home indefinitely. In a review of existing research on isolation during illness breakouts, Brooks et al. (2020) found that parents and children who were quarantined were more likely than those who were not socially isolated to experience post-traumatic stress and symptoms of trauma-related mental health disorders. Alcohol abuse or dependency symptoms were also found amongst quarantined participants, which is important because of the link between parental substance use and child maltreatment (Kepple, 2017). Stressors post-quarantine included financial loss (Brooks et al., 2020); job loss is another factor associated with child abuse and neglect (Scheneck-Fontaine & Gassman-pines, 2020). Therefore, there is strong evidence to suggest a very high risk for increased levels of family violence and child abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study Objective

Given the strong association between social isolation, stress, financial hardship, and family violence, it is likely that the need for child welfare services and support increased dramatically when social distancing and shelter in place policies were enacted. Further, we anticipate that families who had not needed services previously may be newly in need of services due to compounding unexpected stressors brought on by COVID-19. However, anecdotal reports from individual agencies suggest that although need is high, service use during the COVID-19 pandemic is low. To date, there are no empirical studies documenting if service use for child maltreatment prevention and intervention programs in the United States has been impacted by COVID-19. This study seeks to fill this gap in the literature and make a data-driven call to action for evolving child welfare outreach efforts.

Method

Sample

We used publicly available child welfare data from New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services (ACS). New York City’s ACS is a public governmental child protection agency, similar to county child welfare agencies existing in other metropolitan areas (e.g., Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services in California and Harris County Protective Services in Texas); the goal of the ACS is to prevent child maltreatment and provide services to families to avoid out-of-home removals for youth. As opposed to serving only one county, New York City’s ACS serves all five boroughs of New York City (i.e., Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, the Bronx, and Staten Island), and investigates approximately 55,000 cases of maltreatment annually (NYC Children, 2020). Available data focused on frequency counts of new case openings for preventive services at 42 timepoints (i.e., January to June of 2014–2020) across all boroughs of New York City. Preventive services include but are not limited to parental coaching and stress management, childcare, housing assistance, domestic violence advocacy, substance use treatment, services for survivors of sexual exploitation, and intensive family treatment (NYC Children, 2020).

As demographic data for new case openings were not available, we report demographics for New York City to contextualize the study. In 2018, there were 1,739,256 youth under age 18 located in New York City (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018). Approximately 25.9% of youth identify as White, 35.6% as Latinx, 21.6% as Black, 11.6% as Asian, and 5.4% other. Slightly over half of youth in New York City live in a household with two married parents (54.9%), while 30.4% live with a single parent, 9.5% live with grandparents, and 5.2% are in another living situation. Over 25% of families experience economic hardship, with 26.7% of families reporting severe rent burden. As of April 27th, 2020, New York City reported 178,100 COVID-19 cases and 11,708 deaths; this death rate is three to six times greater than the city’s typical death rate (Katz & Sanger-Katz, 2020).

Administration for children’s services and prevention services

In an effort to provide services to support and stabilize at-risk families, preventive services are a critical resource keeping New York City children out of the foster care system. Some of the goals of the ACS preventive services are to strengthen families, avoid out-of-home-removals, and promote positive youth development. Preventive services are overseen by and offered by ACS’ Division of Preventive Services (DPS). The DPS contracts with 54 non-profit agencies and offers a broad range of services. Some examples of the diverse array of preventive services offered include childcare support/skills training, parental substance dependence treatment, support for housing/financial instability, and evidence-based in-home therapeutic services. The preventive services offered through ACS are voluntary, open to families with or without an active ACS maltreatment investigation, open to anyone regardless of immigration status or insurance, free, and delivered through contracted community-based agencies. Youth and families do not need a referral source to receive services; services are initiated through youth and/or their families calling a county helpline or 311 for services, or, requesting services electronically via the ACS website or emailing the Office of Prevention Technical Assistance.

In the case of a referral to ACS, ACS is legally obligated to investigate all reports of child maltreatment. ACS is required to make a determination within 60 days or fewer from the referral date. During the investigation, ACS will determine if services are required and support any family in coordinating the respective services. If ACS determines that there is evidence of child maltreatment or concerns, preventive services will often be offered in order to alleviate psychological or economic stressors. If ACS does not find evidence, community-based preventive services may still be offered to a family (Administration for Children’s Services, 2021).

Materials and Procedures

Administration for children’s services data allowed us to compare trends in preventive case openings before COVID-19 and during the time course of the spread of COVID-19 in 2020. New York City is an important test case because it experienced differentially severe impacts from COVID-19 early in its spread through the United States. Thus, patterns in service use in New York City may provide a model for similar COVID-19 peaks in other cities.

A database was compiled utilizing New York City ACS “monthly child welfare indicator reports” for January to June for the years 2014–2020 (https://www1.nyc.gov/site/acs/about/flashindicators.page). These reports contain information regarding the number of new preventive cases opened in the agency each month dating back 7 years. Two descriptive techniques investigated whether there are reductions in new cases of child maltreatment prevention services.

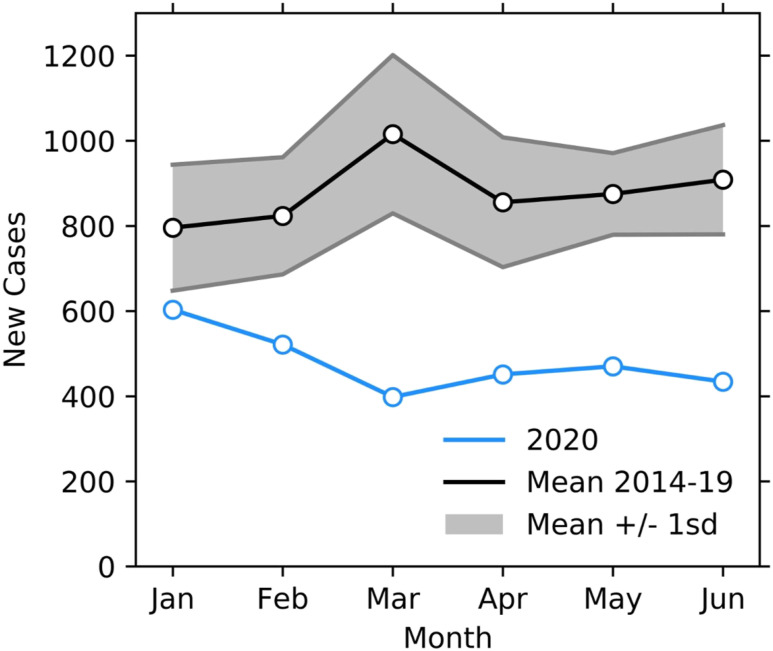

First, the number of preventive case openings in a period prior to mandatory quarantines (i.e., January to June 2014–2019 and January to February of 2020) and during mandatory quarantines (i.e., March to June 2020) were examined to determine if there was a clear pattern of increasing, stable, or decreasing case openings over time (Figure 1) that varied contemporaneously with COVID-19 mandatory quarantines. If the null hypothesis is true, and COVID-19’s spread has had no influence on prevention and intervention services offered by the child welfare system, the number of new prevention service cases would follow the baseline pattern established over the prior six pre-COVID January to June periods. Non-parametric differences tests (i.e., Kruskal–Wallis H-test) were conducted to determine if changes in new child maltreatment prevention service case openings were significantly statistically different depending upon whether New York City was under quarantine for COVID-19.

Figure 1.

A comparison of the mean frequency of new preventive case openings in January to June from 2014–2019 (pre-quarantine) compared to new preventive case openings in January to June 2020 (quarantine) in New York City, NY, USA.

A Poisson regression analysis, used with “count” data (i.e., count of reported cases) was also conducted. As with a typical logistic regression, Poisson regression coefficients represent an odds-ratio (OR) of the difference in the logs of expected counts of the dependent variable, based upon a one unit increase in the independent variable. In this study, COVID-19 status was dummy-coded, with “0” referring to January through June 2014–2019 and “1” referring to January through June 2020. The reported value of the OR is one set of odds divided by another set of odds, which can then be converted into both the percent difference between the odds, as well as a different, more easily interpretable percent difference in frequencies. If the associated p-value is significant, this implies that the independent variable significantly predicts the dependent variable; in this case, it would indicate that COVID-19 status predicts the odds of a new prevention case opening.

We hypothesize that the trend in case openings for 2020 quarantine months will be different than all of the pre-COVID-19 years preceding it (i.e, 2014–2019), and that the odds of opening a new child maltreatment prevention case will be significantly less during quarantine than in the preceding 6 years. This study is exempt from institutional review.

Results

For January to June of 2014–2019, new preventive case openings in New York City ranged from 551–1314 (M = 862.16, SD = 163.95, N = 38). The number of new preventive cases opened in March to June 2020 stands in stark contrast to this range at 398–470 new cases (M = 438.25, SD = 30.60, N = 4). To examine whether the differences were statistically significant, two Kruskal–Wallis H-tests were conducted. The first Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted to compare case counts in pre-COVID-19 January to June and case counts during COVID-19 quarantine. There was a significant difference in the mean number of case openings (Figure 1) for pre-quarantine months (i.e., January to June 2014–2019) compared to cases opened during quarantine months (i.e., March- June 2020); χ2 (1) = 10.61, p = 0.001.

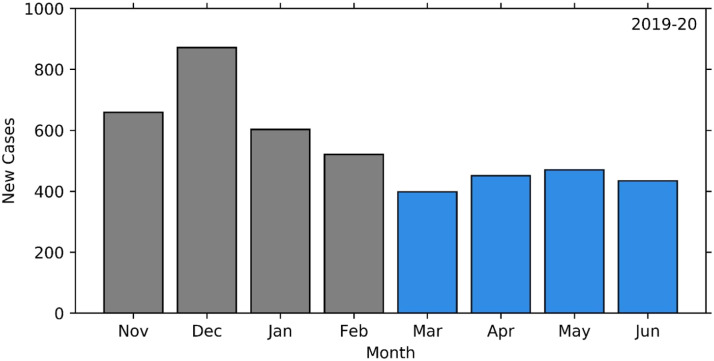

To provide more confidence that differences were not due to any cultural shifts, legal policies, or historical events that may have occurred between 2014 and 2020, a second Kruskal–Wallis H-test was conducted comparing only March to June 2020 (i.e., quarantine months) to November 2019–February 2020 (i.e., the 4 months immediately preceding COVID-19 quarantine announcements; Figure 2). The second Kruskal–Wallis H-test again suggested that the number of pre-quarantine (M = 663.75 SD = 149.95, N = 4) case openings were significantly more numerous than the mean number of cases opened during quarantine (M = 438.25, SD = 30.60, N = 4); χ2 (1) = 5.33, p = 0.021.

Figure 2.

A comparison of new preventive case openings in New York City for pre-quarantine 2019–2020 (November–February) and quarantine 2020 (March–June 2020).

A Poisson regression model was estimated. When comparing January to June of 2014–2019 to March to June of 2020, a test of the regression model suggested that the estimated regression coefficients were not equal to zero, x2 (1) = 3620.95, p < .001; thus, the null hypothesis was rejected, and results suggested that COVID-19 quarantine status predicted the odds of a new prevention case opening. The results of the regression further supported the findings provided by the two independent samples Kruskal–Wallis H-tests. The model estimated that the odds of opening a new child maltreatment prevention case during quarantine (i.e., March–June 2020) were 97% lower than the odds of opening a case in March–June of 2014–2019 (OR = 1.97, p < .001), indicating that case openings declined by 49.17% from the pre-COVID to the COVID periods (M = 862.16 to M = 438.25)

Discussion

There is much conjecture regarding increased need for child welfare service use during the COVID-19 pandemic due to increased risk of maltreatment and other life stressors, and speculative decreased use of services due to quarantine mandates and social isolation. We conducted this study to investigate impacts of COVID-19 quarantine on child maltreatment prevention services. This is the first study to date that uses empirical data to examine the impact of COVID-19 on child abuse prevention services. In addition, New York was one of the first US states to experience a rapid rise in COVID-19 cases. Most other US states experienced lagged growth in COVID-19 cases with similarly lagged responses. Thus, New York serves as a useful model and test case for understanding and projecting impacts from COVID-19 on other states, especially as cities and states begin to face a new COVID-19 related challenge regarding whether to re-employ quarantine orders that had previously been suspended.

Our research demonstrated that families in New York City accessed child welfare preventive services significantly less often when the stay-at-home orders began in March 2020 than prior to that time. Given evidence that child maltreatment increases in times of stress (Tobey et al., 2013), this further suggests the likelihood that families who may need preventive services for the first time due to COVID-19 are not in fact receiving services. New York City ACS reports that their preventive services seek to provide intervention to families at-risk before impairment in the home reaches the level of out-of-home placement. Out-of-home removals are linked to juvenile justice involvement and psychological impairment (Kolivoski et al., 2017), among other adverse outcomes, and youth of color are disproportionately represented in out-of-home placements (Pryce et al., 2019). Reduced access to child maltreatment prevention services may increase the risk of maltreatment and ultimately, increase the number of out-of-home removals. The results in this study suggest a need for increased outreach to families through novel means to bridge gaps in accessing services.

Results of this study show that child welfare prevention service case openings have significantly decreased, suggesting that these societal disruptions have made a large impact on service access. Given that stressors have increased and usual sources of support for vulnerable families are less accessible during the COVID-19 shutdowns, there is the potential for large increases in instances of child abuse. In the United States, school personnel are the primary source of reports to child welfare services (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services et al., 2018). Given that most students are attending school via distance learning, school personnel have limited contact with them and therefore, are likely not able to identify potential cases of child maltreatment at the same rate in comparison to when students are in-person. It appears that now, more than ever, school personnel and teachers may still be the most important mandated reporters in a child’s life; teachers and personnel may need to consider new and different indicators of abuse and neglect that can be identified virtually.

We note several important limitations in this study. The sample for this study was gathered from New York City, which is a relatively distinct sample. New York City’s population is very diverse when compared to the rest of the United States. Notably, this may lead to limited generalizability to the rest of the country. Additionally, given that data were limited to de-identified counts of case openings, rather than a dataset consisting of individuals/participants as the unit of measurement, researchers were unable to report information on the circumstances of the child maltreatment prevention services that were accessed and reported during quarantine. With researchers unable to access specifics of the cases that were reported, there are unknown circumstances that may have been helpful, such as, data specific to identifying geographical location, socioeconomic status, familial circumstances, or the method in which it was reported. These details provide critical information that would aid in identifying families that are still able to access child welfare preventive services, even during COVID-19 quarantine. Moreover, it is unclear whether lower numbers of preventive case openings are due to staffing barriers and complications related to quarantine orders and/or to less access of families and youth to mandated reporters and prevention services.

Recommendations

Identification. To respond to this crisis, community leaders (e.g., community organizers, faith leaders, school personnel, and elected officials) should coordinate with mental health providers and social workers to ensure resources are available that are appropriate both to the needs of their respective communities, and to the unique circumstances of the epidemic. For example, schools should organize virtual check-ins with families to ensure that they are connected to resources. For families they are not able to reach, trusted community leaders can facilitate a coordinated effort of locating and connecting with them. Families that already have a history of abuse or neglect may be particularly susceptible to having children who are not connecting with their teachers or counselors. For example, Missouri has implemented social media campaigns and hotlines targeting families who may have previously been identified as particularly stressed. The social media campaigns aim to normalize the intense stress that may have been exacerbated by COVID-19 and encourages families to ask and accept help. Additionally, Missouri has also applied for emergency funds to bill for services that could effectively be provided as virtual supports, as opposed to in-person, such as, phone calls, online parent classes, and virtual home visits (https://ctf4kids.org/covid-19-response/). We encourage novel ways of supporting families to be translated to distance learning settings, as well.

New ways of identifying child abuse or neglect through remote learning interactions may help teachers identify and refer children and families for social services. Teachers and social workers may need to work closely to connect with students who show warning signs of abuse. Given that many communities may already have limited resources for outreach and resources, social workers can continue to provide virtual check-ins to these families most at risk. Additionally, policymakers should also allocate funds and resources to support the families most in need to reduce the extra stressors due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Given that schools do not have physical access to their students, communities may benefit by having other essential workers in the community receive training to identify abuse or neglect. Virtual online training for neighbors, grocery clerks, and mail delivery personnel can be utilized as a tool to guide community members in recognizing warning signs of abuse and violence in the home and how to report suspected abuse.

Importantly, inequities persist in low-income communities with respect to internet services (DiMaggio & Hargittai, 2001). For this reason, it is recommended that states follow initiatives to provide internet services for communities who may not have access, like initiatives currently in place in New York City (https://www1.nyc.gov/site/acs/about/covidhelp.page). For example, New York City has compiled a list of ways to access cell service and WiFi for low-income families and households with K-12 students. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) created the Emergency Broadcast Benefit Program to support this access for low income families (FCC, 2021). Additional support can be found on a resource page by HighSpeedInternet.com (Armstrong, 2021). Even in communities where free Internet is offered, there are disparities in which households can access these services; local communities should work together to determine how to ensure that this access reaches every household. This is an important step to take for increasing equitable access to maltreatment prevention services, yet additional support helping connect families with these resources is needed through outreach by trained professionals or paraprofessionals

Prevention. Agencies need to consider how to adapt their resources during times of social distancing. Community centers can offer virtual spaces for caregivers to discuss stressors, connect families to resources, and teach potential coping skills. These groups need to be provided in as many languages as possible to offer space to all families. Such initiatives exist at the Department of Child and Family Safety in Los Angeles, CA, where they have implemented parenting classes in an attempt to reduce caregiver stress and provide families with tangible tools (https://dcfs.lacounty.gov/events/). Further, social media can be used to distribute helpline numbers and other resources. Public service announcements on streaming channels, news channels, and social media can disseminate knowledge about substance use disorders and provide information regarding online groups to curb the risk of increased substance use during the epidemic. Additionally, expanding equitable access to mental health resources can support efforts in reducing parent/caregiver stress, and therefore, potentially reducing maltreatment. As an example of this, Iowa has created a free counseling program available to any member in their state, regardless of insurance provider (https://dhs.iowa.gov/sites/default/files/Comm552.pdf?090320201914).

Agencies may also need to consider the unique needs of particularly vulnerable communities. Research identifies social support from the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) community as a protective factor against suicide and mental health issues for LGBTQ youth (Kaniuka et al., 2019). Therefore, resources can be allocated to community centers to encourage maintaining virtual connections among LGBTQ youth and mentors during COVID-19.

Undocumented populations make up another vulnerable group to the impact of COVID-19. Although individuals from undocumented communities are more likely to be classified as essential workers (e.g., agricultural workers and grocery personnel), they are also ineligible for unemployment insurance benefits and disaster relief, such as the CARES Act (Villa, 2020). In California, statewide public and private funding sources have allocated US$75 million as a disaster relief fund to support undocumented workers who have lost their jobs or wages during the pandemic (State of California, 2020). Through this US$75 million fund, individuals can receive a one-time payment of US$500 and households can receive US$1000. Other states can model California’s efforts as a starting point in supporting undocumented individuals, a critical community who are ineligible for federal relief, and in working to provide support to reduce COVID-19 related economic stress. Additionally, free and subsidized childcare for essential workers is critical in alleviating caregiver stress and potentially, to prevent child maltreatment. For example, Iowa has led a state-wide effort in mapping childcare facilities available to essential workers (https://dhs.iowa.gov/childcare/families).

Documentation. Given that this type of widespread closure of schools and public spaces is unprecedented in the modern era, federal and local child welfare agencies should release raw data reporting child maltreatment allegations, substantiations, and service use. Many areas regularly publish such, for example, New York City and Indiana publish monthly service use and allegation rates, and California reports this on a quarterly basis (https://www1.nyc.gov/site/acs/about/flashindicators.page; https://www.in.gov/dcs/3197.htm; https://ccwip.berkeley.edu/). However, it is vital that this information is reported frequently to help investigate national and local trends of child maltreatment. This type of documentation can also support nationwide efforts to identify potential factors, such as economic problems and social support efforts, that influence incidents of abuse and report rates during a pandemic.

Moreover, to reduce child maltreatment during a time that requires essential workers, parents, caregivers, and first responders to be over-extended on time and energy, communities should make efforts to create easily accessible information. Initiatives that document every state’s response to COVID-19 and provides resources for childcare, mental health, and local agencies that may support pressing concern related to the pandemic (https://www.childwelfare.gov/organizations/?CWIGFunctionsaction=rols:main.dspList&rolType=Custom&RS_ID=177&rList=ROL) can be extremely helpful for consolidating information for members of the community. Nonetheless, the website is not easily accessible and varies in information of tangible tools from state to state. We recommend that resources such as the one mentioned above be more easily accessible. For example, agencies can create hashtags and social media campaigns to raise awareness. They can also and make public announcements on the radio to provide easy access to important information for essential workers and parents, which would potentially reduce stress associated with identifying resources and services.

Accurate, timely, and geo-coded documentation of COVID-19 cases has been critical for steering the response to the virus. We argue that similar standards are required for child maltreatment service use during COVID-19. Many service providers report counts of child maltreatment case openings, but these data differ in granularity (e.g., individual-level vs. counts), time scale, and ease of accessibility. It is vital that this information is easily accessible and reported frequently to aid in identifying trends in child maltreatment and correlating trends in case openings with the time course of the COVID-19 response. This type of documentation can also support efforts to identify factors that influence incidents of abuse and reporting rates during a pandemic, such as economic hardship and remote work/school.

We have similar recommendations for community-level interventions. Social distancing and remote school alter how families identify and use services, and how practitioners and mandated reporters identify and report potential instances of child maltreatment. It is critical that this information is targeted, consolidated, and easily accessible for families. Service providers may consider creating hashtags and social media campaigns, and/or creating radio announcements, so that essential workers and parents do not have to expend resources search for information.

Future Research

Future research must explore how people utilize preventive child welfare services while practicing social distancing. Individual-level data would help to highlight differences in reporting depending on multiple factors (e.g., geographic location, demographics, and types of child abuse incidents). While this study quantifies changes in child welfare preventive services during the COVID-19 pandemic, future research should aim to include additional months of the quarantine order and expand on these initial findings for stronger results. In addition, future studies would benefit from examining frequency data from other states in order to make current findings more generalizable to the greater United States population.

Future research on risk factors such as substance use, stress, emotional burden, and unaddressed mental health needs may inform recommendations about of how communities can support families during school closures. Additionally, research on child maltreatment may also benefit from collecting data from families to identify social supports, resources, and services that can reduce familial stress levels when school closures are in place. Families may require extra support to transition when quarantine orders have been lifted, and post-crisis support services may be needed. Communities, researchers, and policy makers should act proactively to devise plans and social supports for vulnerable youth to best transition to the changes that will be needed post social distancing measures.

When social distancing has ended, on a national level, we will be at a unique transition period. This period of transition may allow researchers, policy makers, and community organizers to re-conceptualize and improve the effectiveness of child maltreatment prevention, identification, and intervention. The above mentioned future directions of research can highlight new mechanisms for reporting and prompt higher levels of safety for youth during and even after social distancing measures have been lifted, and families face the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Kelly M. Whaling https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2300-1255

Jill D. Sharkey https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4658-2811

References

- Adminsitration for Children Services . (2021, April 18). Child Welfare. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/acs/child-welfare/child-safety.page

- Armstrong R. L. (2021, March 22). Are there programs to help make internet service more affordable? https://www.highspeedinternet.com/resources/are-there-government-programs-to-help-me-get-internet-service

- Bright M. A., Lynne S. D., Masyn K. E., Waldman M. R., Graber J., Alexander R. (2019). Association of Friday school report card release with Saturday incidence rates of agency-verified physical child abuse. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(2), 176–182. http://doi.org/ggfn63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S. K., Webster R. K., Smith L. E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. http://doi.org/ggnth8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke R. M. (2020). Active monitoring of persons exposed to patients with confirmed COVID-19—United States, January–February 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(9), 245–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coibion O., Gorodnichenko Y., Weber M. (2020). Labor markets during the COVID-19 crisis: A preliminary view (No. w27017). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio P., Hargittai E. (2001). From the ‘digital divide’to ‘digital inequality’: Studying Internet use as penetration increases. Center for Arts and Cultural Policy Studies, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Communications Commission . (2021, February). Emergency broadband benefit. https://www.fcc.gov/broadbandbenefit [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes N. (2020). Economic effects of coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19) on the world economy. SSRN 3557504. [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Mental Health for Children and Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr, 174(9), 819–820.Published online April 14. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C. S., Chee C. Y., Ho R. C. (2020). Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 49(1), 1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John Hopkins School of Medicine . (2021, April 17). Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Kaniuka A., Pugh K. C., Jordan M., Brooks B., Dodd J., Mann A. K., Williams S. L., Hirsch J. K. (2019). Stigma and suicide risk among the LGBTQ population: Are anxiety and depression to blame and can connectedness to the LGBTQ community help? Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 23(2), 205–220. http://doi.org/ggms5k [Google Scholar]

- Katz J., Sanger-Katz M. (2020, April 27). NY.C. Deaths reach 6 times the normal level. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/27/upshot/coronavirus-deaths-new-york-city.html [Google Scholar]

- Kepple N. J. (2017). The complex nature of parental substance use: Examining past year and prior use behaviors as correlates of child maltreatment frequency. Substance Use &Misuse, 52(6), 811–821. http://doi.org/dt55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolivoski K. M., Shook J. J., Kim K. H., Goodkind S. (2017). Placement type matters: Placement experiences in relation to justice system involvement among child welfare-involved youth and young adults. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(8), 847–864. http://doi.org/dt56 [Google Scholar]

- NYC Children . (2020). Prevention services. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/acs/child-welfare/preventive-services.page [Google Scholar]

- Pryce J., Lee W., Crowe E., Park D., McCarthy M., Owens G. (2019). A case study in public child welfare: County-level practices that address racial disparity in foster care placement. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 13(1), 35–59. http://doi.org/dt57 [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Morales A. J., Cardona-Ospina J. A., Gutiérrez-Ocampo E., Villamizar-Peña R., Holguin-Rivera Y., Escalera-Antezana J. P., Alvarado-Arnez L. E., Bonilla-Aldana K., Franco-Paredes C., Henao-Martinez A. F., Paniz-Mondolfi A., Lagos-Grisales G. J., Ramírez-Vallejo E., Suárez J. A., Zambrano L. I., Villamil-Gómez W. E., Balbin

- Rosenthal C. M., Thompson L. A. (2020). Child Abuse Awareness Month during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(8), 812. http://doi.org/dt58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R., Socci V., Talevi D., Mensi S., Niolu C., Pacitti F., Di Marci A., Rossi A., Siracusano A., Di Lorenzo G. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. An N= 18147 web-based survey. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 790. http://doi.org/dt59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck-Fontaine A., Gassman-Pines A. (2020). Income inequality and child maltreatment risk during economic recession. Children and Youth Services Review, 112, 104926. http://doi.org/dt6b [Google Scholar]

- Seddighi H., Salmani I., Javadi M. H., Seddighi S. (2019). Child abuse in natural disasters and conflicts: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(1), 176–185. http://doi.org/dt6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of California . (2020, April 15). Governor Newsom announces new initiatives to support California workers impacted by COVID-19. https://www.gov.ca.gov/2020/04/15/governor-newsom-announces-new-initiatives-to-support-california-workers-impacted-by-covid-19/

- Tobey T., McAuliff K., Rocha C. (2013). Parental employment status and symptoms of children abused during a recession. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 22(4), 416–428. http://doi.org/dt6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2018). Child population [data set]. Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York. https://data.cccnewyork.org/data/map/98/child-population#98/a/6/148/40/a/a [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Administration for Children and Families. Administration on Children. Youth and Families. Children’s Bureau . (2018). Child maltreatment 2018 .https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment [Google Scholar]

- Usher K., Bhullar N., Durkin J., Gyamfi N., Jackson D. (2020). Family violence and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 10.1111/inm.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa L. (2020, April 17). ‘We’re ignored completely.’ Amid the pandemic, undocumented immigrants are essential but exposed .https://time.com/5823491/undocumented-immigrants-essential-coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- Wallace C. L., Wladkowski S. P., Gibson A., White P. (2020). Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1), E70–E76. http://doi.org/dt6f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., Ho C. S., Ho R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. http://doi.org/ggpxx6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S. N., Armitage C. J., Tampe T., Dienes K. (2020). Public perceptions and experiences of social distancing and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A UK-based focus group study. BMJ Open, 10. http://doi.org/dt6g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]