Abstract

Objectives

Timely intravenous-to-oral antibiotic switching for children is important for paediatric antimicrobial stewardship (AMS). However, low decision-making confidence and fragmentation of patient care can hamper implementation, with difficulties heightened regionally where AMS programmes for children are lacking. The aim of this study was to develop and evaluate user-led creation and implementation of an intervention package for early intravenous-to-oral switching at regional hospitals in Queensland, Australia.

Design

Guided by theory, a four-phase approach was used to: (1) develop multifaceted intervention materials; (2) review materials and their usage through stakeholders; (3) adapt materials based on user-feedback and (4) qualitatively evaluate health workers experiences at 6 months postintervention.

Setting

Seven regional hospitals in Queensland, Australia.

Participants

Phase 2 included 15 stakeholders; health workers and patient representatives (patient-guardians and Indigenous liaison officers). Phase 4 included 20 health workers across the seven intervention sites.

Results

Content analysis of health worker and parent/guardian reviews identified the ‘perceived utility of materials’ and ‘possible barriers to use’. ‘Recommendations and strategies for improvement’ provided adjustments for the materials that were able to be tailored to individual practice. Postintervention interviews generated three overarching themes that combined facilitators and barriers to switching: (1) application of materials, (2) education and support, and (3) team dynamics. Overall, despite difficulties with turnover and problems with the medical hierarchy, interventions aided and empowered antibiotic therapy decision-making and enhanced education and self-reflection.

Conclusions

Despite structural barriers to AMS for switching from intravenous-to-oral antibiotics in paediatric patients, offering a tailored multifaceted intervention was reported to provide support and confidence to adjust practice across a diverse set of health workers in regional areas. Future AMS activities should be guided by users and provide opportunities for tailoring tools to practice setting and patients’ requirements.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, Protocols & guidelines, Infection control, PAEDIATRICS

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Provides a theory-based approach to the development and evaluation of a user-led paediatric antimicrobial stewardship intervention.

Examines the perspectives of health workers and parents/guardians in the creation of materials to improve early paediatric intravenous-to-oral antibiotic switching and their uptake.

Provides perspectives for barriers and some solutions to improving comprehension of healthcare materials for Indigenous parents/guardians.

Postintervention qualitative interviews did not include parents/guardians or Indigenous health liaisons to understand the parent/guardian information leaflets uptake in practice.

Although sampling regional, rural and remote hospitals in Queensland, it could in future be expanded to incorporate a larger number of these sits to identify the variance between these hospital environments and professional perspectives.

Introduction

Increasing antimicrobial resistance worldwide has prompted international development of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programmes, with the goal of optimising antibiotic use to limit resistance development. While one strategy for enhancing appropriate antibiotic use is the promotion of early intravenous -to-oral antibiotics transition, or ‘intravenous-to-oral switch’,1 2 these have yet to be uniformly adopted into national guidelines in many countries.3

In 2011, Australia introduced AMS as a dedicated hospital accreditation standard and an incentive for AMS programmes.4 However, barriers to AMS programme implementation include a lack of decision-making confidence, fragmentation of patient care across health practitioners and access to AMS expertise.5 These issues are frequently present in regional areas,6 7 with geographical isolation, small staff numbers and less access to AMS expertise and support than urban areas.8

Although Australia has seen a push for greater AMS programmes nationally, there are some limitations within the measures commonly used or recommended in adult settings, which may not be translatable to paediatrics. This disparity has resulted in significant evidence gaps in infection burden surveillance, susceptibility patterns9 10 and implementation of AMS activities.9 11 Indeed, in their policy statement on AMS, the American Academy of Paediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases and the Paediatric Infectious Diseases Society12 include implementing a programme specifically for the conversion of intravenous-to-oral antibiotic therapy in children. In a recent publication, we used a package of intervention materials for intravenous-to-oral switching in paediatric patients.13 This intervention allowed healthcare workers to tailor materials to their practice setting and patients’ requirements, demonstrating that a tailored programme increased the percentage of patients whose intravenous therapy was appropriately stopped or switched to oral therapy as well as decreased the duration of intravenous antibiotics requirements. This study provides a structured analysis of the development and evaluation of these materials as a timely intravenous-to-oral AMS strategy using consultation with health workers and parent/guardians and aiming to optimise uptake and reduce barriers to use in remote and regional Queensland hospitals.

Methods

A combination of two conceptual theoretical frameworks (decision sampling framework14 and person-based approach15) were used to develop and evaluate a multifaceted package of tailored interventions. Evaluation included stakeholders at seven Queensland regional and rural hospital sites comprising patient-guardians and diverse health practitioners, such as nurses, doctors, pharmacists and Indigenous liaison officers. Here, we present the stepped phases of development, implementation and evaluation of a paediatric intravenous-to-oral switch programme. The final resources used for the intervention can be found in online supplemental materials.13

bmjopen-2022-064888supp001.pdf (8.5MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-064888supp002.pdf (94.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-064888supp003.pdf (368.5KB, pdf)

Framework

The decision sampling framework presents optimal ‘evidence-informed decisions’ for intervention creation by using (1) the best available evidence, (2) experts to evaluate and review the usefulness, practicality, and the contexts and intervention will be used in, and (3) the consideration of values of intervention users and their patients to increase the use and impact of an intervention. The person-based approach, similarly, focuses on the development of interventions as concentrating on and accommodating perspectives of those who will use the intervention, ensuring ease of use and relevance. In designing an intervention, this framework encourages the use of consultation with experts and stakeholders as part of intervention development at multiple stages of the process to identify key challenges and evaluate components of the intervention from a user perspective.

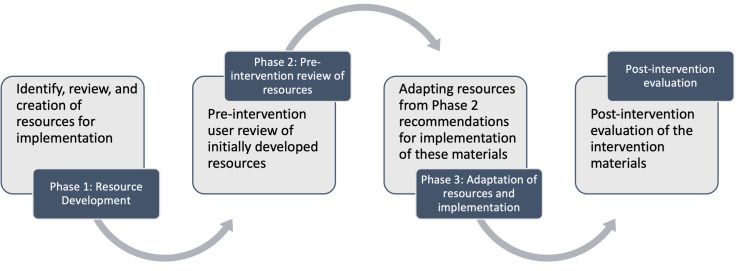

Drawing on these frameworks, the research involved four phases (figure 1): (1) Resource development: identifying, reviewing and creating resources for implementation; (2) a preintervention review of these resources; (3) adapting resources based on user recommendations and implementation of the materials; and (4) a postintervention evaluation of the intervention materials. See online supplemental additional file 1 for a COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research) checklist of the qualitative phases.

Figure 1.

Four phases of the development and evaluation of paediatric intravenous-to-oral switch materials.

bmjopen-2022-064888supp004.pdf (263.2KB, pdf)

Phase 1: resource development

An intervention package for paediatric AMS ‘switching’ from intravenous-to-oral antibiotic therapy was resourced by the research team from relevant literature through PubMed searches (limited to English-language publications) and author libraries from 2014 to 2018. AMS intervention materials were guidelines for community acquired pneumonia and skin and soft tissue infections, decision flow charts, medication tables, chart stickers, fact sheets, lanyards and a patient-guardian information leaflet that promoted timely intravenous-to-oral conversion of antibiotic therapy (see online supplemental material 1).

Phase 2: preintervention review of resources

A qualitative preintervention evaluation of these intervention resources by 15 multidisciplinary healthcare workers, 8 parents/guardians and 5 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers (including Indigenous Liaison Officers) from a regional and rural hospital site was conducted. Parents/guardians and Indigenous Liaison Officers were purposively sampled through invitation by local hospital coordinators. Healthcare workers were recruited through snowball sampling. Individual semistructured interviews were conducted by an independent female qualitative research officer (VL) from the university. However, where the researcher was not able to conduct the interview by phone, they were conducted on-site by one of two local paediatric registrars (a man and a woman) trained in interview techniques at two study sites. All participants were provided with an information sheet that included the aims of the research and asked for their consent to take part in audio recorded interviews. Participants were provided with a copy of the questions before the interviews (see online supplemental material 2), which asked them to review the content and design of the intervention materials and consider their relevance and utility for them personally, their practice, and/or that of their colleagues, or other parent/guardians perspective. All interviews were digitally audiorecorded, transcribed verbatim and deidentified. The duration of interviews was not recorded.

Analysis was conducted by two independent coders (VL, LSS) with respective backgrounds in medicine and psychology. Analysis used directed qualitative content analysis, which was focused on the decision sampling framework to identify gaps in information, practical implementation of the materials and suggestions for improvement.

Phase 3: adaption of resources and implementation

Resources from phase 1 were adapted based on responses from the phase 2 semistructured interviews. Implementation for each site used the reviewed and adapted package of intervention resources and were applied using a persuasive approach. This suite of interventions provided healthcare workers with the opportunity to tailor the use of these tools according to their practice setting and patient’s requirements (table 1). A more detailed discussion about this aspect of the study can be found in online supplemental material 3.

Table 1.

Intervention materials and their placement on wards

| Material | Description | Type | Common placements |

| ?STOP Poster* | A simple intravenous-to-oral guide to aid in practitioner’s decision-making. | A3 posters A4 laminate |

On walls and in medication charts |

| Flow chart* | Detailed chart for identifying those eligible for intravenous-to-oral antibiotic conversion. | A3 posters A4 laminate |

On walls and in medication charts |

| Stickers on paediatric inpatient medication chart | Reminders to prompt a medication review. | Labels/stickers | Medication charts |

| Guidelines | For CAP and SSTIs including first line antibiotics and dosages, and another included comparable intravenous-to-oral antibiotics for switching. | A4 laminate | In medication charts |

| Fact sheet | A general intravenous-to-oral conversion fact sheet for healthcare workers. | A4 handouts | Given to health workers |

| Education presentation | One-hour presentation regarding AMS and the intervention. | Presentation | In-person and online |

| Patient-guardian information leaflet | Information for patient-guardians regarding switching from intravenous-to-oral antibiotic medication. | Pamphlet | On ward or in the pharmacy |

| Patient-guardian video | A 10 min video presented by an Indigenous doctor regarding switching from intravenous-to-oral antibiotic medication for patient-guardians. | Video | Online |

*= site choice of wall placement

AMS, antimicrobial stewardship; CAP, community acquired pneumonia; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection.

Phase 4: postintervention evaluation

To explore whether and how the intervention materials were used as an AMS strategy in paediatric patients, we again conducted semistructured interviews with 20 health practitioners from the seven study sites. Unfortunately, these interviews were not able to include parents/guardians because access to this population was not feasible at the end of the 6-month intervention and after the completed treatment period for patients. Further we were not able to know who received the material to contact them for this phase of the research. Participants were recruited through emails to hospital staff and via snowball sampling, with the aim to include a range of health practitioners who had the opportunity to use the materials. A minimum sample size of 15 participants was specified and recruitment stopped when interviews appeared to have reached data saturation (information redundancy), identified by a lack of variation in the richness of answers across participants.16 Interviews generally followed the same procedures as phase 2, with a female qualitative research officer (LSS) from the university conducting interviews over the phone and the same two registrars conducting in-person interviews at local sites where phone interviews were not possible. The 20 interviews analysed ranged between 5 and 32 min in duration (M=17.29 min). Participants were asked to reflect on their use of the materials and provide perceptions of the quality of the content (comprehension and relevance), effectiveness of the design of the materials, perceptions of usefulness in daily practice and how supported they felt to effectively use the materials.

Thematic analysis for this phase was conducted by two independent coders (LSS and JF) with different health backgrounds (psychology and pharmacy). Analysis used an essentialist approach, reflecting the reality and experiences of participants that was reflexive and iterative to identify themes within the data.17–19 Themes were generated from codes based on underlying constructs with a focus on implementation of the materials to daily practice, support to use the materials and the effectiveness of the materials. Consensus on themes was achieved after discussion and refinement by coders.

Patient and public involvement

Physicians (paediatricians, registrars and consultants) pharmacists, nurses and patient representatives (patient-guardians and Indigenous liaison officers) were involved in the design and implementation of the overall project. Their level of involvement is described in each phase of the research. Results of the research will be disseminated to study participants if they indicated interest in receiving an abstract of the findings. They will be further disseminated through hospital newsletters and practice-oriented publications.

Results

Phase 2: preintervention review

Demographics for phases 2 and 4 are shown in table 2. Results for phase 2 identified gaps in information and practical implementation of the intervention materials interviews and are presented in table 3. Online supplemental material 3 provides further decision-making and quotes related to this phase.

Table 2.

Preintervention and postintervention participant demographics

| Preintervention (phase 2) | Postintervention (phase 4) | ||||||

| N | % Women | N | % Women | Mean time in role | Primary material preference | Secondary material preference | |

| Registered nurse | 4 | 75 | 5 | 100 | 5.7 years | ?STOP guide | Patient-guardian leaflet/education |

| Pharmacist | 3 | 67 | 6 | 100 | 8.5 years | ?STOP guide / Detailed flow chart | Patient chart stickers |

| Paediatric director/consultant | 4 | 25 | 1 | 100 | 3 years | ?STOP guide | Detailed flow chart |

| Paediatric registrar | 1 | 100 | 4 | 75 | 1.3 years | ?STOP guide | Patient-guardian leaflet |

| Junior resident | 3 | 67 | 3 | 67 | 1.3 years | ?STOP guide | None |

| Indigenous health worker/liaison | 5 | 60 | 1 | 0 | 1 years | ?STOP guide | Patient-guardian leaflet |

| Parent/guardian | 8 | 88 | 0 | – | – | N/A | |

Table 3.

Facilitators, barriers and recommendations for change to encourage intravenous-to-oral switch intervention utilisation

| Material | Perceived utility of materials | Possible barriers to use | Recommendations and strategies |

| Eligibility flowchart and suitable agents |

|

|

|

| ?Stop guideline |

|

|

|

| Lanyard With guideline |

|

|

|

| Patient chart stickers |

|

|

|

| Fact sheet |

|

|

|

| Patient-guardian information leaflet |

|

|

|

| Indigenous perspectives of patient-guardian information leaflet |

|

|

|

The materials were viewed as having some perceived utility, particularly to healthcare workers (table 3). For healthcare workers, the materials were seen as: accessible and direct information resources, able to assist with decision-making confidence, helpful learning tools or prompts and able to support communication between multidisciplinary teams. Carers who evaluated the patient-guardian information leaflet felt it could empower them to ask questions about treatment and felt more widely informed about doctors’ decision making. On the other hand, Indigenous health workers felt that there were multiple barriers to use the patient-guardian leaflet for these regional and rural areas. It was noted that low literacy and health literacy would mean few in their community would be able to understand the information leaflet. Among other things, the cultural diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, distrust of Western healthcare, differences in the way knowledge is passed on (eg, visually), and the different dynamics of living spaces among these peoples highlighted that there was no ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

Phase 3: adaptation

New resources were developed based on the feedback from phase 2. These included a patient video to address where English was not a first language for parents/caregivers and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients where liaison officers advocated for more opportunities for visual learning. This video was led and produced an AMS pharmacist in collaboration with a regional Indigenous medical doctor to meet the needs of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. An online education video was also developed by a paediatric infectious disease specialist and AMS pharmacist to upskill clinicians in the management of acquired pneumonia and skin and soft tissue infections as well as provide guidance for timely intravenous-to-oral conversion.

Phase 4: postintervention

Overall, three major themes were found in the data. See table 4 for example quotes by themes.

Table 4.

Postintervention themes and example quotes

| Theme | Sub-theme | Example quote |

| Application of materials | Utility of decision-aids | ‘Yeah especially in regards to suitability whereby you know the patient has got a specific disease like a cellulitis that they cannot or have not in the past … Yeah it’s good because it gives you a clear guide for using another agent.’ (Pharmacist, regional) |

| Memorable and simple |

‘Yes I’d say the yellow sticker was the best because it was bright and it’s hard to miss on the chart so it was kind of just a prompt for them when they were reviewing the chart.’ (Pharmacist, rural) ‘I think just because it was straightforward and just easy, I think the clinicians they refuse to cut guidelines. I think the flow chart just made a lot more sense, it’s easy.’ (Registrar, rural) |

|

| Targeted locations | ‘They were definitely strategically placed to not be overwhelmed but be in places where you are thinking about prescribing antibiotics.’ (RN, remote) | |

| Understanding patients’ needs |

‘…it was a way for me to just, you know, add-on to the counselling… Rather than just saying, ‘Take 5 mill’s four times a day’ … it gave a couple of other talking points to go through the leaflet. Just to make sure they knew how long it had to go on for, what to do if they needed to go back to see the doctor again and that sort of thing.’ (Senior Pharmacist, rural) ‘…when we give patients information or their parents info I think if it’s like a long-term chronic condition they are likely to read it and are more receptive.’ (Registrar, remote) ‘I feel that in the clinical situations in this hospital we haven’t been requiring the flow chart much over the last few months. And that’s on the basis that our consultants are already doing quite well in terms of switching antibiotics or ceasing antibiotics already before the flow chart was given to us.’ (Registrar, regional) |

|

| Education and support | Updating and reinforcing knowledge |

‘…we did that to help flag and get the discussions around antimicrobials and paediatrics happening all around this time. So for us it was good to do that and raise a bit more awareness on the type of medications they were prescribing and you know whether it was matching guidelines…’ (Senior pharmacist, rural) ‘… it did allow more open conversations with other people because there was a resource there. So in terms of helping me explicitly make the same decisions probably not a lot of help. But in terms of facilitating discussions with other people about the same decision making, very helpful.’ (Registrar, rural) |

| Familiarity |

‘You need to be familiar with it so I have familiarized most of the nursing staff with it at changeover or when they’re on shift. But if you are familiar with it it’s great especially considering that some of the nurses are having more contact time than say the medical staff will so it’s giving them a bit more confidence.’ (Senior Pharmacist, regional) ‘I didn’t know there was a video available so I would not expect that the rest of my staff knew…’ (NUM, rural) |

|

| Reminders | ‘(an AMS practitioner) came and spoke with us … and she came back a second time as well so she came and did some education with the doctors and then came and did some education with the nurses. I think that’s helpful.’ (NUM, rural) | |

| Team Dynamics | Empowering staff and changing practice | ‘(It) gives me sort of some confidence to ask about changing to oral.’ (RMO, rural) ‘Yes, definitely and I noticed a few times they would fax through an antibiotic request to pharmacy that would have the sticker on it and then (for) the dispensing pharmacist that would be a prompt to them to say ‘oh okay maybe I need to call about this to supply more’ before I supply it.’ (AMS Pharmacist, rural) |

| Multi-disciplinary engagement | ‘… it was good that it was so inclusive, quite often we’ve done things where it’s only just been nurses … it’s been their full responsibility. But having that whole procedure so if we didn’t pick it up the doctors hopefully did, or the pharmacists will come through and do it.’ (RN, rural) | |

| Knowledge and experience |

‘So even if you’re pointing out guidelines or you're pointing out resources … it may be that the person who makes all the decisions just makes their own decision based on their own experience or their own opinion a lot of the time. So I don’t, it’s my impression that often my more senior, my consultants did not appreciate, they don’t appreciate the guidelines…’ (Registrar, remote) ‘So I just didn’t know if we, there was any point in us actually using the resource because it was just something that we already knew.’ (NUM, rural) |

|

| Transience | ‘Out here we have a very transient medical population, and our nursing staff change quite a bit as well. Probably more than most departments and I think that that is part of the problem, I'm the only consistent person that’s been here in the last twelve months.’ (Registrar, remote) |

Application of materials

Utility of decision-aids

Across participants, there were generally positive views about the impact of the materials, particularly the design of the materials and how they supported decision making.

Memorable and simple

Each of the materials varied in their frequency and popularity of use, but the use of materials that were eye-catching, memorable and simple to use were the most often used. This was primarily true for the ?STOP chart and the yellow chart stickers for antibiotic review. The ?STOP chart in particular was the most favoured material across all health disciplines and the yellow sticker was used most often by pharmacists. These materials were used differently by each type of health practitioner, with doctors using them as switching guides, nurses using them to prompt doctors and for education, and junior doctors using them as evidence for decisions to switch in presentations to seniors. This is reflected further in the themes below and preferences for materials can be seen in table 1.

Targeted locations

Strategic placement of the materials was an important factor for all participants to easily access, engage with, and remember materials for decision-making. Thus, location and convenience of materials was paramount to success of the intervention. Participants reported remembering and using charts and posters placed in hand-over rooms, clinical rooms, treatment rooms, nurses’ stations, within patient charts, next to computers or as online bookmarks. In these high-traffic and relevant areas, they posed as a reminder about the importance of antibiotic switching and could also aid in decision-making.

Understanding patients’ needs

Factors of patients and their caregivers also influenced decisions to use (or not use) the materials. For example, patient-guardian leaflets were offered intermittently, with some health practitioners finding them useful adjuncts to delivering face-to-face advice with patient-guardians regarding why they were switching from intravenous-to-oral antibiotics. Alternately, others only offered leaflets with complex patients as they felt patient-guardians would be most receptive to the information. Similarly, some paediatric teams felt they did not need the switching materials because their patients were not complex enough or where they had already switched antibiotics to oral within 24–48 hours.

Education and support

Updating and reinforcing knowledge

Participants described the materials as supporting education and training among staff members unfamiliar with AMS, as well as their use as reminders of what antibiotics are appropriate and how to effectively switch from intravenous to oral. Further, doctors and pharmacists felt the presence of the materials helped to facilitate more discussion around AMS and to solidify prior knowledge regarding appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Familiarity

Familiarity with the content of the switching guides was expressed as necessary to enable effective use of those guides. Having departmental and executive support to understand the information in the materials was described as central to this process. However, knowledge about the types of materials available or their whereabouts on the ward were not always available to staff. In particular, difficulties arose regarding the video created for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, which was also available as an audiovisual option for other patient-guardians. Participants reported not using this video, primarily because they were not aware of it. However, those who were aware, primarily nurses, either did not know how to access it or due to technological constraints, could not provide the video as a resource to patient-guardians.

Reminders

Reminders were often suggested as the best way to prompt continued use of the materials, in the form of education and simple emails. It was also suggested that the strategy of in-person education used within this study was a persuasive prompt for AMS and use of materials to aid switching decision-making.

Team dynamics

Empowering staff and changing practice

Both junior and senior staff felt the materials were empowering and helpful for junior medical and nursing practitioners in presenting a decision to a senior staff member. Ultimately, several participants commented that the use of the materials had influenced their own or their team members’ practice in thinking and acting more proactively about switching from intravenous-to-oral antibiotics within paediatric care.

Broad engagement

Some participants felt the broad engagement of different health practitioners helped to ensure good AMS practice across patient care.

Prior experience

However, difficulties were also noted in engaging material uptake particularly among senior doctors/consultants. Participants echoed that for those senior healthcare workers, they were less likely to use the available guidelines and instead base their decisions on prior knowledge and experience.

Transience

Lack of support and engagement from some sites, particularly in rural and remote areas, created difficulties in appropriate use of the materials. Notably, all health practitioner groups reported that not having pharmacists on the ward or a lack of engagement from pharmacy was a constraint on effectively employing the intervention. This limitation was not always due to a pharmacist’s lack of awareness of the intervention, but rather due to suboptimal pharmacy presence on the ward owing to staffing issues and ward sizing. Similarly, across all participants, the main explanation for a lack of engagement with the materials was related to staff turn-over or low staff numbers that involved constantly retraining new staff or the need for more support.

Discussion

This research used a decision-sampling framework and person-based approach to develop and evaluate a multifaceted intervention package for improved timely and safe switching from intravenous-to-oral antibiotics in children. The four-phase approach used in this research was successful in guiding the creation, review, adjustment and evaluation of materials through a user-led focus. The initial review process provided wide-ranging feedback regarding the efficacy of the materials, and importantly provided an avenue for users to make suggestions for the materials that were tailored to their own sites, teams and knowledge. Indigenous health workers provided the most extensive feedback, recognising that the parent/guardian leaflet was unlikely to have the intended impact among many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parent/guardians. This was due to a variety of differences, but particularly identification that their communities would be more likely to learn and pass on knowledge visually and through conversation in culturally appropriate language. Subsequently, an Indigenous paediatric medical doctor led the creation of a video providing culturally appropriate information regarding antibiotic switching.

After 6 months of using the intervention materials, evaluations from various health practitioners revealed three overarching themes regarding the intervention and decision-aids: the application of materials, education and support, and team dynamics within and between hospitals. Overall, the intervention materials were viewed as aiding and empowering antibiotic therapy decision-making, assisting clinical decisions among all participants, and were particularly helpful at supporting junior doctors. The materials were used differently by each practitioner group to influence or support their own or others’ decisions. Those who discussed using them in their own practice were most frequently junior doctors, nurses and pharmacists, who felt they increased their individual capacity to influence antibiotic decision-making. This increased professional confidence and knowledge is likely to lead to more proactive attitudes and switching behaviours, where previously there has been resistance.17 18 Of the physical supporting material, while the most popular material was the ?STOP poster, most were seen as helpful for making switching decisions, or for communicating them to other healthcare workers and patient-guardians. Importantly, many participants felt that the intervention increased their knowledge of AMS practices, their ability to educate others, empowered them or others to make decisions (including presenting decisions to seniors), and assisted with AMS practice change. A key to their engagement appeared to be the presence of materials in various strategic places, such as placement in medical charts and pinned on walls. Having materials available at the most impactful locations meant that AMS was conveniently visible and could be kept in mind during prescribing, and overall, that switching information was memorable to key healthcare workers.

Similar to previous research, the most frequently highlighted barriers to uptake and engagement with the intervention were structural.5 7 Most hospital sites noted difficulties with the hierarchy of medical engagement. For some, mainly registrars, there were difficulties with high turnover of consultants and senior medical staff, such that medical teams did not have consistent leadership and the support to use interventions. This was also often recognised concerning pharmacy support, including from pharmacists themselves, with similar issues regarding lack of support stemming from high turnover or smaller wards at regional hospitals.7 18 For others there was a feeling of opposition, or a lack of appreciation, of the guidelines and materials from senior consultants who tended to preference their knowledge and experience over formal guidelines.6 20 While it is unclear whether this practice influenced others, it may lead to reduced confidence, particularly among junior doctors, in making or presenting switching decisions to senior consultants.

Key barriers to implementation of AMS practices in rural and regional Australia, and globally, have been identified as a lack of access to AMS support, education and training, and difficulties attracting and retaining staff, particularly staff with AMS expertise.5–7 18 Promisingly, our results show that access to tailored AMS support and appropriate resources can improve education and increase internal training of AMS practices across a broad array of health practitioners. While staff retention was still identified as a problem at all sites, though particularly in rural and remote areas, the impact of staff turnover was lessened by broad training and support to health practitioners at multiple levels, including registered nurses, junior resident medical officers, pharmacists and registrars.

Strengths and limitations

Limitations of our study were the small number of participating stakeholders and lack of input from patient-guardians and carers during the postintervention evaluation (phase 4). A lack of patient-guardians included in this phase means we do not know the extent to which the patient-guardian leaflet was useful in informing their understanding of the switching process. This should be a priority in future research to ensure patient-guardian materials continue to be adapted to suit their needs. Furthermore, although Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Liaison Officers provided feedback in the initial phases of the project, they were not included in the postevaluation as they were not involved in delivery of direct patient care, treatment decisions, and the use of the intervention materials. However, doing so would have provided further insight regarding how the Indigenous patient-guardian video could have affected patient care if it was used. A secondary preintervention evaluation of stakeholders following adaption of the resources in phase 3 would also likely have assisted with understanding barriers to access the newer materials, like the video. This may have identified further avenues for education, particularly regarding Indigenous patient/guardians, which could have been included in health worker education. Nevertheless, the interviewees were recruited from a range of regional areas, professions (including nurses and pharmacists) and are representative of a multidisciplinary team involved in caring for sick children. This approach shed light on the experiences of health workers in their preferences for materials and how those materials were used to aid antibiotic intravenous-to-oral switching by varying discipline and health context.

Although our study was conducted in rural and regional hospitals in one Australian state, we believe the findings are relevant for other settings in Australia and within similar health systems worldwide. Notably, a strength of our study is the involvement of local clinicians in the preintervention and postintervention evaluation, which may enable sustainability of the intervention. In particular, this study used a package of interventions which provided health workers with the opportunity to tailor the available tools to their practice setting and patient’s requirements, which is more realistic of a real-world situation and multifaceted approach more likely to be effective.21 22 Further, while we found consistent cross-site utilisation and acceptance of the materials, we are yet to grapple with the global change to digital medication charts and systems where prompt fatigue may render interventions like ‘chart stickers’ and visual reminders difficult to implement. Only one site included in this study had transitioned to a digital chart system. Although they were able to implement the materials flexibly, through posters near computers and links to guidelines, we need further research to understand the impact of digital systems in the implementation of future interventions.23 Importantly, improving antibiotic prescribing and management at the point of care requires complementary strategies: (1) changing clinician behaviour and (2) educating patients and families about the role of antibiotics in medical care and their own well-being.24

Conclusions

When guided by local clinicians and stakeholders, offering multifaceted intervention package to facilitate a timely switch from intravenous-to-oral antibiotic therapy in paediatric patients is successfully able to inform and adjust practice across hospital teams. Although more needs to be done to ensure all healthcare workers can embrace and support new interventions in a hospital setting, another main and not easily addressable issue remains the lack of sufficient long-term staff and their perpetually high turnover in regional hospitals. This is a major barrier to uptake in the long term. Future studies should explore how these interventions can be embedded within the healthcare infrastructure of a hospital and rely less on championship by individual staff.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Dr Andree Wade and Dr Gary Dyari Wood who generously conducted interviews. We are grateful to the health practitioners, Indigenous liaison officers and patient-guardians who generously shared their views and time with us during the stages of this research, providing valuable contributions.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was led by MLA with with MLvD, JEC, AI and NG contributing to the conception of the study. MLA reviewed the articles and extracted information for review and creation of resources. VL was responsible for the preintervention interviews, these were analysed by VL and LSS. MLA and MLvD adapted resources from the preintervention interview comments. Postintervention interviews were completed by LSS and analysis was completed by LSS and JF. The manuscript was led and written by LSS. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. LSS is responsible for the overall content as garantor.

Funding: This work was supported by a Children’s Hospital Foundation grant (50232). The Children’s Hospital Foundation had no involvement in any aspect of the research or decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved across all sites by Children’s Health Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (LNR/18/QRCJ/44322). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Cyriac JM, James E. Switch over from intravenous to oral therapy: a concise overview. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2014;5:83–7. 10.4103/0976-500X.130042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mertz D, Koller M, Haller P, et al. Outcomes of early switching from intravenous to oral antibiotics on medical wards. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;64:188–99. 10.1093/jac/dkp131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kopsidas I, Vergnano S, Spyridis N, et al. A survey on national pediatric antibiotic stewardship programs, networks and guidelines in 23 European countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020;39:e359–62. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care . National safety and quality health service standards. Sydney: ACSQHC, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broom J, Broom A, Adams K, et al. What prevents the intravenous to oral antibiotic switch? A qualitative study of hospital doctors’ accounts of what influences their clinical practice. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71:2295–9. 10.1093/jac/dkw129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James R, Luu S, Avent M, et al. A mixed methods study of the barriers and enablers in implementing antimicrobial stewardship programmes in Australian regional and rural hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70:2665–70. 10.1093/jac/dkv159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bishop JL, Schulz TR, Kong DCM, et al. Qualitative study of the factors impacting antimicrobial stewardship programme delivery in regional and remote hospitals. J Hosp Infect 2019;101:440–6. 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishop JL, Schulz TR, Kong DCM, et al. Similarities and differences in antimicrobial prescribing between major city hospitals and regional and remote hospitals in Australia. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2019;53:171–6. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryant PA. Antimicrobial stewardship resources and activities for children in tertiary hospitals in Australasia: a comprehensive survey. Med J Aust 2015;202:134–8. 10.5694/mja13.00143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osowicki J, Gwee A, Noronha J, et al. Australia-Wide point prevalence survey of the use and appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing for children in hospital. Med J Aust 2014;201:657–62. 10.5694/mja13.00154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant P, Morgan N, Clifford V, et al. 257. A whole of country analysis of antimicrobial stewardship resources, activities, and barriers for children in hospitals in Australia. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018;5:S108–9. 10.1093/ofid/ofy210.268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerber JS, Jackson MA, Tamma PD, et al. Policy statement: antibiotic stewardship in pediatrics. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2021;10:641–9. 10.1093/jpids/piab002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avent ML, Lee XJ, Irwin AD, et al. An innovative antimicrobial stewardship programme for children in remote and regional areas in Queensland, Australia: optimising antibiotic use through timely intravenous-to-oral switch. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2022;28:53–8. 10.1016/j.jgar.2021.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackie TI, Schaefer AJ, Hyde JK, et al. The decision sampling framework: a methodological approach to investigate evidence use in policy and programmatic innovation. Implement Sci 2021;16:1–17. 10.1186/s13012-021-01084-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, et al. The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e30. 10.2196/jmir.4055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charmaz K, Sampling T. Theoretical Sampling, Saturation and Sorting. In: Constructing grounded theory / Kathy Charmaz. London: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broom A, Broom J, Kirby E. Cultures of resistance? A bourdieusian analysis of doctors’ antibiotic prescribing. Soc Sci Med 2014;110:81–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broom A, Broom J, Kirby E, et al. What role do pharmacists play in mediating antibiotic use in hospitals? A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008326. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne D. A worked example of braun and clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Quant 2022;56:1391–412. 10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SL, Azmi S, Wong PS. Clinicians' knowledge, beliefs and acceptance of intravenous-to-oral antibiotic switching, hospital pulau pinang. Med J Malaysia 2012;67:190–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulliford MC, Prevost AT, Charlton J, et al. Effectiveness and safety of electronically delivered prescribing feedback and decision support on antibiotic use for respiratory illness in primary care: reduce cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2019;364:l236. 10.1136/bmj.l236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Little P, Stuart B, Francis N, et al. Effects of internet-based training on antibiotic prescribing rates for acute respiratory-tract infections: a multinational, cluster, randomised, factorial, controlled trial. Lancet 2013;382:1175–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60994-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Backman R, Bayliss S, Moore D, et al. Clinical reminder alert fatigue in healthcare: a systematic literature review protocol using qualitative evidence. Syst Rev 2017;6:255. 10.1186/s13643-017-0627-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamma PD, Cosgrove SE. Addressing the appropriateness of outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States: an important first step. JAMA 2016;315:1839. 10.1001/jama.2016.4286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-064888supp001.pdf (8.5MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-064888supp002.pdf (94.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-064888supp003.pdf (368.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-064888supp004.pdf (263.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.