Abstract

Abortion is criminalised to at least some degree in most countries. International human rights bodies have recognised that criminalisation results in the provision of poor-quality healthcare goods and services, is associated with lack of registration and unavailability of essential medicines including mifepristone and misoprostol, obstructs the provision of abortion information, obstructs training for abortion provision, is associated with delayed and unsafe abortion, and does not achieve its apparent aims of ether protecting abortion seekers from unsafe abortion or preventing abortion. Human rights bodies recommend decriminalisation, which is generally associated with reduced stigma, improved quality of care, and improved access to safe abortion. Drawing on insights from reproductive health, law, policy, and human rights, this review addresses knowledge gaps related to the health and non-health outcomes of criminalisation of abortion. This review identified evidence of the impacts of criminalisation of people seeking to access abortion and on abortion providers and considered whether, and if so how, this demonstrates the incompatibility of criminalisation with substantive requirements of international human rights law. Our analysis shows that criminalisation is associated with negative implications for health outcomes, health systems, and human rights enjoyment. It provides a further underpinning from empirical evidence of the harms of criminalisation that have already been identified by human rights bodies. It also provides additional evidence to support the WHO’s recommendation for full decriminalisation of abortion.

Keywords: Public Health

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Existing studies establish the impacts on abortion care, abortion seekers and abortion providers when abortion is criminalised. Meanwhile, doctrinal studies in international human rights law show increased awareness of the incompatibility of criminalisation with a range of rights including the right to privacy and the right to health.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Using an innovative methodology that integrates international human rights law and public health research, this study substantiates the material ways in which criminalisation impacts on abortion seekers and health workers and thus concretises human rights implications. It shows the impact of criminalisation not only of pregnant people who seek abortion, but across the spectrum of availing of, providing, and assisting with abortion care.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This paper provides evidence of the incompatibility of criminalisation with aspirations for the maximisation of health outcomes and the realisation of human rights. In doing so, it demonstrates health and human rights imperatives for decriminalisation as a matter of legal and policy change.

Introduction

Criminalisation can be understood as the application of criminal law to some or all persons who seek, access, provide (including medication), assist with, are aware of, or believe someone to have accessed abortion (UN Special Rapporteur, paras. 21–36).1 Where abortion is criminalised, the criminal law is used to regulate abortion, and those who have, provide, or support with availing of consensual abortion may be arrested, investigated and/or prosecuted (although in some settings the law is not actively applied). Abortion is criminalised in most countries.2 In some settings general offences (such as manslaughter or murder) are applied to people who avail of, provide or assist with accessing abortion either in addition to offences specific to abortion or as a way of criminalising abortion in practice. In some settings having an abortion is a crime, while in others the pregnant person does not commit a crime but those who assist her or provide abortion to her do. Even in jurisdictions where abortion is available on broad grounds, abortion may still be criminalised or criminal sanctions may apply to other synonyms for abortion including ‘termination of pregnancy’, ‘destruction of unborn human life’, ‘procurement of a miscarriage’ or ‘menstrual regulation’.2

In many settings criminalisation of abortion is a legacy of 19th century regulatory approaches, often residual from colonial-era laws.3 Criminalisation does not align with either the human rights of abortion seekers or providers, or the realities of contemporary abortion care, which is safe, effective and not harmful.4 Key human rights institutions have stated that criminalisation results in the provision of poor-quality healthcare goods and services (UN Special Rapporteur, para. 32),1 is associated with lack of registration and unavailability of essential medicines including mifepristone and misoprostol, obstructs the provision of abortion information (UN Special Rapporteur, paras. 21–36; Human Rights Committee),1 5 obstructs training for abortion provision (UN Special Rapporteur, paras. 21–36),1 is associated with delayed and unsafe abortion (UN Special Rapporteur, paras. 21–36; Human Rights Committee, para 20; Human Rights Council, paras. 93–95),1 6 7 and does not achieve its apparent aims of either protecting abortion seekers from unsafe abortion or preventing abortion.1 6 7 Meanwhile, public health scholars generally associate decriminalisation with reduced stigma, improved quality of care and improved access to safe abortion.8

There is now a consensus in international human rights law that criminal abortion laws jeopardise the health and life of abortion seekers (UN Special Rapporteur; Human Rights Committee, para. 8; CEDAW Committee, para. 31(c)),1 9 10 are discriminatory (Human Rights Council, paras. 46, 50, 90; Human Rights Council, paras. 49–51),11 12 and violate human rights protections (Human Rights Council, paras. 93–95).7 As a result, human rights institutions increasingly take the view that abortion should be decriminalised.13–15 While these sources do not tend to provide a comprehensive definition of decriminalisation, when we speak of decriminalisation we refer to the full decriminalisation of abortion for women, providers and assistants through the removal of abortion and all abortion-related offences from the criminal law and penal code, and the non-application of other offences (like manslaughter or murder) to those who access, provide, or assist with availing of abortion.

In this review, we aim to address knowledge gaps that relate to health and non-health outcomes associated with the criminalisation of abortion. In particular, we seek to assess whether, how and to what extent evidence from included studies demonstrates empirically the rights violations that are associated with criminalisation. The review was designed in accordance with a methodology for integrating human rights in guideline development that we have described elsewhere.16 This methodology is appropriate for complex interventions, including laws and policies, which may have have multiple components interacting synergistically, have non-linear effects, or are context dependent.17 Complex interventions of this kind often interact with one another, meaning that outcomes related to one individual or community may be dependent on others, and that they might be positively or negatively impacted by the arrangements of people, institutions and resources within a larger implementation system.17 This is one of seven reviews with the same methodological approach that was conducted as part of developing the evidence base for WHO’s Abortion Care Guideline.18

Throughout this review, we use the terms women, girls, pregnant women (and girls), pregnant people and people interchangeably to include all those with the capacity for pregnancy.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

The nature of this research did not require or enable the involvement of patients or the public, although criminalisation was identified as a law and policy intervention for consideration within the broader process of guideline development at a scoping meeting that took place in Geneva. The participants in this meeting are listed in the Abortion Care Guideline (WHO, p. 122).18

Identification of studies and data extraction

This review examined the impact of criminalisation on two populations: (1) people seeking abortion and (2) healthcare providers. Law, policy, and human rights scholars and practitioners worked together to develop the search strategy and outcomes of interest. We searched in English for a combination of MeSH terms and keywords.

Searches were conducted in PubMed, HeinOnline and JStor and the search engine Google Scholar. As the second edition of the WHO’s Safe Abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems (2012) included data up until 2010, we limited our search to papers published in English after 2010 to 2 December 2019. We undertook an updated search of the same databases in July 2021. We aimed to locate papers that included original data and analysis on the connections (direct and indirect) between criminalisation of abortion and our outcomes of interest. We included a wide range of study types, including (comparative and non-comparative) quantitative studies, qualitative and mixed-methods studies, reports, PhD theses and economic or legal analyses that undertook original data collection or analysis. Following a preliminary assessment of the literature,19 we identified health and non-health outcomes of interest that could be linked to the effects of criminalisation. The identified outcomes of interest were delayed abortion, opportunity costs (understood widely as including, inter alia, financial and health harms), self-managed abortion, workload implications, system costs, perceived imposition on personal ethics or conscience, perceived impact on relationship with patient, referral to another provider, unlawful abortion, continuation of pregnancy, and stigmatisation.

There were six members of the review team (MF, AF, FdL, AC, MIR and AL). Two reviewers (MF and AF) conducted an initial screening of the literature. Titles and abstracts were first screened for eligibility using the Covidence tool; full texts were then reviewed. A third reviewer (FdL) confirmed that these manuscripts met inclusion criteria. Two reviewers (FdL and AC) extracted data. Any discrepancies were reviewed and discussed with two additional reviewers (AL and MIR). The review team resolved discrepancies through consensus.

Consistent with our methodology for integrating human rights in reviews that underpin evidence bases for guideline development,16 we analysed international human rights law relevant to reproductive rights to identify applicable (hard and soft) legal standards. These were standards that referred either expressly to the criminalisation of sexual and reproductive healthcare including abortion, or outlined states’ general obligations vis-à-vis sexual and reproductive healthcare as they could be applied to the criminalisation of abortion. As described elsewhere,16 this included a systematic analysis of sources such as treaties, general comments, opinions of treaty monitoring bodies and reports of special procedures. Having undertaken the searches and full-text review, we integrated the evidence from the studies and from international human rights law to develop a full understanding of the law and policy implications for our outcomes of interest of criminalisation of abortion. In applying human rights standards to the data extracted from these manuscripts, we sought to identify which human rights standards are engaged by criminalisation, and whether this evidence suggests that criminalisation has positive or negative effects on the enjoyment of rights. Where the manuscripts did not contain any data relevant to the outcomes of interest, we considered whether human rights law provided evidence that could further explicate the impacts and effects of criminalisation.

Analysis

Using evidence tables described in our methodology,16 we presented data from the included studies as relevant to our outcomes of interest. In these tables, we presented both the association of each finding with the outcome of interest and an overall conclusion of the identified findings across the body of evidence. Following this, we applied the identified human rights standards to these outcomes thus combining the evidence from human rights law and the included studies to develop an understanding of the effects of criminalisation of abortion. This allowed us to assess whether the evidence from the included studies indicated effects of criminalisation that were incompatible with international human rights law.16 Across all study designs, we used and applied a visual representation of effect direction to summarise the effect of the intervention, with symbols indicated whether the evidence extracted from a study suggested an increase (▲), decrease (⊽), or no change (○) to the outcome of interest, but not indicating magnitude of the effect.16

Results

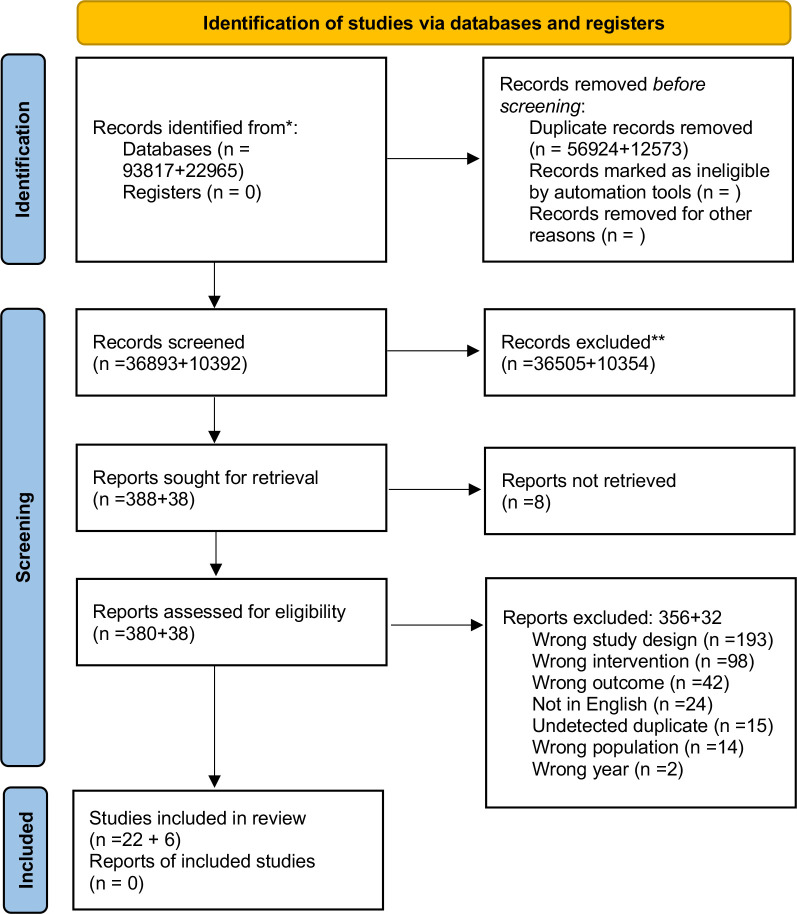

The initial search generated 47 285 citations after duplicates were removed. We screened the titles and abstracts and conducted a full-text screening of 426 manuscripts. We excluded those manuscripts that did not have a clear connection with the intervention and our predefined outcomes, resulting in 28 manuscripts being included in the final analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. *Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). **If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools. From: Page et al.62 PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Manuscripts described data from the following 19 settings: Australia,20–22 Brazil,23 Chile,24 25 El Salvador,26 Ethiopia,27 Ireland28–30 Lebanon,31 Mexico,32–37 Nepal,38 Northern Ireland,28 39 Palestine,40 Philippines,41 Rwanda,42 Senegal,43 Sri Lanka,44 Tanzania,27 Uganda,45 Uruguay and46 47 Zambia.27 The characteristics of included manuscripts are presented in table 1. The included studies contained information relevant for the outcomes: delayed abortion24 29 39 continuation of pregnancy,32 36 46 47 opportunity costs,21 22 24–26 28 29 31 33 37 39–44 self-managed abortion,24 28 39 41 unlawful abortion,24 28 31 35 37 39–42 44 45 criminal justice procedures against women23 24 26 27 37 45 and healthcare professionals,20 21 24 30 41 45 workload implications,20 21 42 43 referral to another provider,29 40 perceived impact on relationship with patient,22 24 29 antiabortion ‘sting’ operations,21 42 availability of trained providers,21 29 41 reporting of suspected unlawful abortions,23–27 29 35 41–43 and system cost.24 29 31 32 34 36 38 40 41 45–47 No evidence was identified linking the intervention to the outcomes harassment of healthcare providers and stigmatisation of healthcare providers. As might be expected in a review of this kind, and as becomes clear in the results described below, some findings are repeated across outcomes of interest.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author/year | Country | Methods | Participants |

| Aiken et al 201939 | Northern Ireland, UK | Qualitative individual in-depth interviews (n=30). | Women in Northern Ireland who had sought an abortion by travelling to a clinic in Great Britain or by using online telemedicine to self-manage an abortion at home. |

| Aiken et al 201728 | Ireland and Northern Ireland, UK | Retrospective cohort study (n=5650). | Women living in Ireland and Northern Ireland utilising the online telemedicine services of Women on Web. |

| Aitken et al 201729 | Ireland | Cross sectional study (n=184). | Non-consultant hospital doctors training in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. |

| Antón et al 201646 | Uruguay | Times series design (n=not reported). | Data from the Perinatal Information System on births among women and girls below 20 years of age. |

| Antón et al 201847 | Uruguay | Times series design (n=93 762 births). | Data from the Perinatal Information System on planned and unplanned births. |

| Arambepola and Rajapaksa 201444 | Sri Lanka | Case control study (n=771). | Women admitted to hospitals due to unsafe abortion (cases) and delivery of an unintended term pregnancy (controls) |

| Blystad et al 201927 | Ethiopia, Tanzania, Zambia | Qualitative individual interviews (n=79). | Representatives of Ministries, religious organisations, non-governmental organisations, UN agencies, professional organisations, health workers, journalists and others |

| Casas and Vivaldi 201424 | Chile | Legal analysis and qualitative individual interviews (n=61). | Hotline providers, healthcare providers, women with experiences of ‘illegal abortions’, their friends, partners and relatives. |

| Casseres 201823 | Brazil | Legal analysis/commentary based on a legal analysis of 42 criminal lawsuits. | N/A. |

| Citizen’s Coalition 2014 | El Salvador | Legal case series (n=129) in which records from women who were prosecuted for abortion or aggravated homicide when fetal death occurred in the last months of the pregnancy. | N/A. |

| Centre for Reproductive Rights 2010 | Philippines | Legal review/qualitative individual interviews (n=53). | Women with experiences of unsafe abortion, acquaintances of women who had died as a result from unsafe abortion, a range of key stakeholders including healthcare providers, lawyers, activists, counsellors, political leaders and law enforcement agents |

| Clarke and Mühlrad 201632 | Mexico | Times series design. Analysis of vital statistics data covering live births (n=23 151 080) and maternal deaths (n=11 858) among women aged 15–44. | N/A. |

| De Costa et al 201320 | Queensland and New South Wales, Australia | Qualitative individual interviews (n=22). | Physicians providing abortions in the states of Queensland and New South Wales. |

| Douglas et al 201321 | Queensland and New South Wales, Australia | Qualitative individual interviews (n=22). | Physicians providing abortions in the states of Queensland and New South Wales |

| Fathallah et al 201931 | Lebanon | Qualitative interviews (n=119). | Women who have had an abortion (n=84) and physicians who provide abortion (n=35) in the five provinces of Lebanon between 2003 and 2008. |

| Friedman et al 201933 | Mexico City, Mexico | Times series design. Review of the medical records of women (n=35 054) seeking abortion. | N/A. |

| Henderson et al 201338 | Nepal | Retrospective cohort study. Review of medical charts (n=23 493) of abortion-related admissions at four public hospitals. | N/A. |

| Juarez et al 201937 | Querétaro, Tabasco and the State of Mexico, Mexico | Qualitative individual interviews (n=60). | Women aged 15–44 with experience of abortion in the three states Querétaro, Tabasco and the State of Mexico. |

| Koch et al 201534 | Mexico | Times series design (n=not reported). Analysis of maternal mortality data from 32 states in Mexico over a 10-year period. | N/A. |

| LaRoche et al 202022 | Australia | Qualitative individual interviews (n=22). | Women, transgender and gender non-binary people from across Australia who had obtained a medical abortion while living in Australia. More than half of the participants (n=13) obtained their abortion in a state where procuring a first-trimester termination was subject to criminal law at the time of their procedure. |

| Nara et al 201945 | Uganda | Qualitative interviews and focus group discussions (n=69). | Congolese refugees aged 15–49 living in Kampala and the Nakivale Refugee camp (n=58 (interviews n=21; focus groups n=36)), and key informants working with refugees and/or in the sexual and reproductive health field (n=11). |

| Påfs et al 202042 | Kigali, Rwanda | Qualitative individual interviews (n=32) and focus group discussions (n=5). | Healthcare providers (physicians, nurses and midwives) involved in post-abortion care (PAC) at three public hospitals |

| Power et al 202130 | Ireland | Qualitative interview (n=10). | Fetal medicine specialists. |

| Ramm et al 202025 | Chile | Survey instrument (n=313) and qualitative interviews (n=30). | Medical and midwifery students at seven universities (survey). Faculty members at the same universities, all of whom were practicing clinicians (interview). |

| Shahawy 201940 | Palestine | Qualitative individual interviews (n=60). | Patients, female companions of patients, and hospital staff aged from 18 to 70 years, most of whom were Muslim, married and urban dwellers, had a high school education or less, and had at least three children. |

| Suh 201443 | Senegal | Qualitative individual interviews (n=36) and observations of PAC services at three hospitals. | Healthcare professionals |

| Van Dijk et al 201235 | Mexico City, Mexico | Review of medical charts (n=12) of maternal mortality occurring over a 3-year period. | N/A. |

| Gutiérrez Vázquez et al 201636 | Mexico City, Mexico | Times series design (n=not reported); 10% of public census data at three time points. | N/A. |

N/A, not available.

Impact of criminalisation on abortion seekers

A summary of the impacts of the intervention on abortion seekers and the application to human rights are presented in table 2. Evidence identified per study and outcome is presented in online supplemental table 1.

Table 2.

Impact of criminalisation on abortion seekers

| Outcome | Overall conclusion of evidence (A) | Application of HR standards (B) | Conclusion evidence+HR (C) |

| Delayed abortion | Overall, evidence from three studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to abortion delay. While evidence from two of these studies suggests that criminalisation leads to healthcare providers delaying care for women who are suffering from severe pregnancy complications, evidence from one study indicates that while criminalisation does not stop women from having an abortion, it complicates women’s abortion pathways and thereby delays abortion. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by taking steps to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity including addressing unsafe abortion, by protecting people from the risks associated with unsafe abortion, to protect people seeking abortion and by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence-based and proportionate). | Criminalisation can result in delayed access to abortion care. Such delays may be associated with unsafe abortion or increased risks of maternal mortality or morbidity, with negative implications for rights. |

| Continuation of pregnancy | Overall evidence from four studies suggests that criminalisation indirectly contributes to increased continuation of pregnancy; decriminalisation is associated with reductions in birth rates. While two of these studies suggests that criminalisation affects the birth rates of women 20–29 and 20–34 years in particular, 1 study points to a greater impact among adolescents. Evidence from one study suggests that criminalisation does not impact adolescent birth rates. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence based and proportionate), to equality and non-discrimination, to decide the number and spacing of children. It can also result in a violation of the state’s obligation to ensure abortion is available where the life and health of the pregnant person is at risk, or where carrying a pregnancy to term would cause her substantial pain or suffering, including where the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest or where the pregnancy is not viable. | Criminalisation is associated with continuation of pregnancy. Where that is undesired, this has negative implications for rights. |

| Opportunity cost | Overall, evidence from 14 studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to opportunity costs including travelling for abortion, delayed abortion and postabortion care, apprehension of legal repercussions, poor quality post abortion care, emotional distress, financial costs, internalised and experienced stigma, confusion about accessing abortion, and sexual and financial exploitation. Evidence from two studies suggests these opportunity costs disproportionately impact some groups of women. Evidence from two studies suggests that although criminalisation may create fear among women it does not impact the decision to have an abortion. |

Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by protecting people from the risks associated with unsafe abortion, and ensuring ensure abortion regulation is evidence-based and proportionate). | Criminalisation contributes to opportunity costs for those accessing or seeking abortion, with negative implications for rights. |

| Unlawful abortion | Overall, evidence from 11 studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to unlawful abortion. These abortions are either self-managed or conducted in healthcare facilities. They are sometimes unsafe and may lead to death. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by taking steps to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity including addressing unsafe abortion, by protecting people from the risks associated with unsafe abortion, to protect people seeking abortion, and by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence-based and proportionate). It can also result in a violation of the state’s obligation to ensure abortion is available where the life and health of the pregnant person is at risk, or where carrying a pregnancy to term would cause her substantial pain or suffering, including where the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest or where the pregnancy is not viable. | Criminalisation is associated with access to unlawful abortion. Such unlawful abortion may be unsafe and/or increase risks of maternal mortality and morbidity, with negative implications for rights. |

| Self-managed abortion | Overall, evidence from four studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to self-managed abortion. These abortions are sometimes unsafe. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by taking steps to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity including addressing unsafe abortion, by protecting people from the risks associated with unsafe abortion). | Criminalisation may be associated with recourse to self-managed abortion. Where such self-managed abortions are unsafe, or increase risks of maternal mortality or morbidity, criminalisation has negative implications for rights. |

| Criminal justice procedures | Overall, evidence from three studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to criminal justice procedures against women and girls, some of which lead to convictions. Evidence from two studies indicates that criminalisation creates fear of legal repercussions among women undergoing abortions, and evidence from another study suggests that prosecutions and convictions against women are rare. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligation to protect, respect and fulfil the right to information (where information provision is criminalised), the rights to life and health (by protecting people seeking abortion and ensuring the availability of postabortion care without criminal sanction), and the right to privacy. | Criminalisation exposes women and girls to criminal proceedings, and to the risks associated with not accessing, support, timely information or timely postabortion care. This has negative implications for rights. |

bmjgh-2022-010409supp001.pdf (199.9KB, pdf)

Evidence from three studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to abortion delay.24 29 39 Specifically, healthcare professionals may delay provision where women are experiencing complications to be sure that they ‘qualify’ under limited exceptions to criminal offences.29 One study also demonstrates that criminalisation complicates the care pathway by forcing women to travel out of country or rely on telemedicine services; care pathways on which medications may be confiscated during transport, delivery may be prolonged, and there may be resultant delays in accessing care.39 While delay in accessing abortion does not per se constitute a human rights violation, delays associated with criminalisation may engage states’ obligations to take steps to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity and to address delayed and unsafe abortion,1 6 7 not least because of the requirement to ensure abortion regulation is evidence based and proportionate.1 Evidence from four studies suggests that criminalisation indirectly contributes to increased continuation of pregnancy32 36 46 47 by identifying the impact of decriminalisation on birth rates. These studies suggest that decriminalisation is associated with decreased birth rates in women aged between 20 and 29,36 20 and 34,47 and 15 and 4432 years of age. One study identifies a more marked trend towards reduced fertility among adolescents following decriminalisation,32 while another found little effect on adolescent birth rates in a setting where parental authorisation requirements continued to apply post-decriminalisation.36 Evidence from one study suggests that decriminalisation was not associated with a change in adolescent birth rates.46

Evidence from 16 studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to opportunity costs. We understand opportunity costs widely as including travel to access abortion, delayed and poor-quality post-abortion care, distress, financial burdens, stigma and exploitation.21 22 24–26 28 29 31 33 37 39–44 These opportunity costs impact disproportionately on certain populations of women and girls such as single women and women from socioeconomically disadvantaged groups31 and those accessing care in public rather than private healthcare sectors.25 Accordingly, the right to equality and non-discrimination in sexual and reproductive healthcare is engaged (Human Rights Council, paras. 46, 50, 90; CEDAW Committee, paras. 49–51),11 12 and these differential impacts appear not to be proportionate or evidence based.1 Additionally, two studies suggest that, despite generating fear among some pregnant women, criminalisation does not impact the decision to have an abortion.37 44 Four studies suggest that criminalisation contributes to self-managed abortion,24 28 39 41 which is sometimes unsafe24 41 and sometimes unlawful,24 28 39 while 11 studies suggest that it contributes to unlawful abortions,24 28 31 35 37 39–42 44 45 some of which are unsafe and lead to death.35 In one study, women reported avoiding seeking care from health facilities or trained providers because of the criminalisation of abortion,44 while another study revealed in criminalised settings that fear of litigation among healthcare providers contributes to denial of abortion and subsequent recourse to unlawful abortion.42 While some self-managed abortions may be unlawful, not all are, just as not all unlawful abortions are self-managed, however, as both occur outside of the formal health system, they may be less safe. Accordingly, this evidence illustrates that criminalisation of abortion appears incompatible with the human rights obligation to protect the health and life of abortion seekers (UN Special Rapporteur; Human Rights Committee, para. 8; CEDAW Committee, para. 31(c)).1 9 10

The evidence outlined in this section indicates clearly that criminalisation is incompatible with states’ obligation to take steps to prevent and reduce maternal mortality and morbidity and to protect women from unsafe abortion outlined above. In some cases, the criminalisation of abortion can result in violations of the right to life, and human rights bodies have made it clear that women should not be criminalised for accessing abortion.1 6 7 9–12 Illustrating that criminalisation can result in women who have abortions coming into contact with the criminal justice system, evidence from three studies shows that criminal justice procedures are initiated against women who seek abortion,23 24 26 although one further study suggests this is rare,27 and two further studies show that women who avail of abortion fear criminal justice repercussions.37 45

Impact of criminalisation on healthcare providers

A summary of the impacts of the intervention on health professionals and the application of human rights are presented in table 3. Evidence identified per study and outcome is presented in online supplemental table 2.

Table 3.

Impact of criminalisation on abortion providers

| Outcome | Overall conclusion of evidence (A) | Application of HR standards (B) | Conclusion evidence+HR (C) |

| Workload implications | Overall, evidence from four studies suggests that criminalisation has increased workload implications for healthcare providers who, in order to comply with regulations and avoid criminal investigations, have to refer women to other health professionals, provide detailed written statements and ensure documentation does not put themselves or their patients at risk. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by protecting healthcare professionals providing abortion care, and by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence based and proportionate). | Workload implications arising from criminalisation place significant burdens on healthcare professionals providing abortion care, with negative implications for both their rights and the rights of persons seeking to access comprehensive abortion care. |

| Referral to another provider | Overall, evidence from two studies suggests that criminalisation of abortion, including abortion referrals, will complicate women’s pathways to a safe and legal abortion. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by taking steps to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity including addressing unsafe abortion, by protecting people from the risks associated with unsafe abortion, to protect people seeking abortion, and by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence-based and proportionate). | Criminalisation can result in complications in accessing safe abortion care. Where such complications increase risks of maternal mortality or morbidity, they have negative implications for rights. Criminalisation may deter people seeking abortion or for those who have availed of abortion from accessing comprehensive abortion care, including referral within the formal medical system, with negative implications for rights. |

| Perceived impact on provider–patient relationship | Evidence from three studies suggests that criminalisation negatively impacts the provider patient relationship. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by protecting people seeking abortion, and by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence based and proportionate). | Criminalisation can impact negatively on the doctor–patient relationship, with negative implications for women and girls’ right to health. |

| Antiabortion sting operations | Overall, evidence from two studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to apprehension of anti-abortion sting operations. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by protecting healthcare professionals providing abortion care). | Where criminalisation is associated with antiabortion sting operations, this may put healthcare professionals who conscientiously provide comprehensive abortion care and information at risk of legal or professional sanction, with negative implications for their rights and the rights of abortion seekers or those who have had abortions. |

| Criminal justice procedures against healthcare providers | Overall, evidence from one study indicates that criminalisation leads to criminal justice procedures against abortion information providers and evidence from five studies suggests that healthcare providers anticipate criminal justice procedures against them resulting from their clinical practice. In addition, evidence from two of these studies indicates that fear of criminal justice procedures leads to hesitancy to provide abortion care, including in cases of non-viable pregnancies. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by protecting healthcare professionals providing abortion care, and by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence-based and proportionate). | Actual or apprehended criminal justice procedures against healthcare providers associated with criminalisation may result in reduced or hindered access to comprehensive abortion care. Where this is the case, criminalisation interferes disproportionately with rights to health and to physical and mental integrity. |

| Availability of trained providers | Overall, evidence from three studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to lower availability of trained providers and a loss of relevant skills. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by taking steps to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity including addressing unsafe abortion, by protecting people from the risks associated with unsafe abortion, to protect people seeking abortion, by ensuring that where it is lawful abortion is safe and accessible, and by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence-based and proportionate). | Criminalisation is associated with reduced availability of trained providers and a loss of relevant skills, with implications for the availability of competent providers for exceptions to criminalisation, for the reduction of maternal mortality and morbidity and, thus, for human rights. |

| Reporting of suspected unlawful abortion | Overall, evidence from eight studies suggests that some healthcare providers report or would report a woman suspected of an induced abortion, while evidence from two studies indicate that healthcare providers generally do not report women to authorities. Where abortion is criminalised, there is not always a consensus among healthcare providers about whether and when one should report. While some never report in order to avoid being dragged into an investigation, others report to protect themselves from any legal repercussions. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligation to protect, respect and fulfil the right to information (where information provision is criminalised), the rights to life and health (by protecting people seeking abortion, by protecting healthcare professionals providing abortion care, by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence-based and proportionate, and by ensuring the availability of post-abortion care without criminal sanction), and the right to privacy. | Where criminalisation requires or results in healthcare professionals reporting suspected unlawful abortion, this may deter women and girls from seeking or safely accessing abortion information with negative implications for rights. Where criminalisation requires or results in healthcare professionals reporting suspected unlawful abortion, this may put healthcare professionals who conscientiously provide comprehensive abortion care and information at risk of legal or professional sanction, with negative implications for their rights and the rights of abortion seekers or those who have had abortions. |

| System costs | Overall, evidence from 12 studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to system costs. Four of these studies suggest that criminalisation, indirectly, contributes to system costs by showing how decriminalisation impacts birth weight positively, decreases unplanned pregnancies and fertility, and increases maternal mortality and severe abortion morbidity. Evidence from four studies shows that criminalisation contributes to system costs by creating a black market for abortion medication, by delaying abortion and post-abortion care until women are severely ill, by contributing to poor quality of postabortion care, and by preventing women from accessing evidence based, safe and effective treatment. Evidence from one study indicates that criminalisation does not contribute to any system costs related to adolescent birth rates and finally, evidence from one study suggests that factors related to maternal healthcare and health status impact maternal mortality and not abortion legislation itself. |

Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the rights to life and health (by taking steps to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity including addressing unsafe abortion, by protecting people from the risks associated with unsafe abortion, by ensuring abortion regulation is evidence based and proportionate). | Criminalisation is associated with system costs, including those related to access to unlawful abortion, unsafe abortion, and increased maternal morbidity and mortality. Thus, criminalisation has negative implications for rights. |

| Harassment | No evidence identified. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the right to health (by protecting healthcare professionals providing abortion care). | Criminalisation of abortion may expose healthcare professionals to risks of harassment, criminal prosecution, or sting operations. The implications for healthcare professionals of criminalisation may reduce the no of willing providers of lawful abortion, abortion information or postabortion care with implications for the health and rights of abortion seekers or persons who have accessed abortion including unsafe abortion. |

| Stigmatisation | No evidence identified. | Criminalisation engages states’ obligations to protect, respect and fulfil the right to health (by protecting healthcare professionals providing abortion care). | Criminalisation of abortion may lead to stigmatisation of abortion care provision with implications for the professional life, health and well-being of healthcare professionals. |

Evidence from four studies suggests that criminalisation has increased workload implications for healthcare providers associated with complex regulations and ensuring they do not put themselves or their patients at risk of investigation or prosecution.20 21 42 43 This can involve what physicians considered to be unnecessary referrals to psychiatrists and other physicians for second opinions to establish compliance with exceptions to abortion criminalisation,20 the provision of detailed written statements justifying abortion provision in specific cases to manage risk of prosecution,21 and the exercise of particular caution when preparing paperwork and case files.42 43 Two studies suggest that referral pathways and practices are complicated by criminalisation,29 40 and three studies show that criminalisation negatively impacts the relationship between provider and patient.22 24 29 Physicians perceived criminalisation to have such negative impacts because they consider they cannot provide optimal care due to criminalisation,29 must undertake reporting24 and experience patients being wary and sometimes dishonest in interactions because of their apprehension of the criminal law.22

While evidence from only one study indicates that criminal justice proceedings are taken against abortion information providers,24 evidence from five studies suggests that healthcare providers anticipate criminal justice procedures against them resulting from their clinical practice,20 21 30 41 45 and two studies indicate that criminalisation leads to hesitancy in providing care.30 41 Evidence from two studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to healthcare providers’ apprehension of being subject to antiabortion sting operations,21 42 in one case reportedly resulting in health workers providing abortion care clandestinely.42 Combined with the findings from human rights bodies that criminalisation results in a ‘chilling effect’ in the provision of healthcare, with negative implications for the rights to life, health and privacy of women who seek abortion care,5 13 this evidence points clearly to the negative effects of criminalisation.

Overall, evidence from three studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to lower availability of trained providers and a loss of relevant skills.21 29 41 As a matter of international human rights law states are required to ensure that sexual and reproductive healthcare is available, accessible, acceptable and of good quality to protect, respect and fulfil the right to health.48 If, as these studies suggest, criminalisation contributes to a reduction in trained and available abortion care providers this has implications for the extent to which the state is fulfilling these obligations. While evidence from two studies indicate that healthcare providers generally do not report women to authorities,27 43 evidence from eight studies suggests that some healthcare providers report or would report a woman suspected of an induced abortion and consider themselves bound to do so.23–26 29 35 41 42 This reveals the ways in which criminalisation operates incompatibly with international human rights law, which makes it clear that states may not require healthcare professionals to report people for accessing abortion1 6 and that postabortion care must always be available regardless of the legal status of abortion.1 9 11 The combination of the evidence from these studies and applicable international legal standards points clearly to the negative impacts of criminalisation. Overall, evidence from 10 studies suggests that criminalisation contributes to system costs ranging from increased maternal mortality and morbidity, to creating a black market for abortion medication, delaying postabortion care, and distorting record keeping,24 29 31 32 34 36 38 40 41 45–47 with clear implications for the fulfilment of the right to health.48

Discussion

As outlined above, international human rights law requires states to take steps to ensure women do not have to undergo unsafe abortion, to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality, and to effectively protect women and girls from the physical and mental risks associated with unsafe abortion. Yet, the evidence from this review suggests that criminalisation has implications for access to safe abortion, as well as for the experience of seeking and availing of abortion care. Under international human rights law, states are required to revise their laws to ensure that in practice, the regulation of abortion does not jeopardise women’s lives, subject women or girls to physical or mental pain or suffering constituting torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, discriminate against women or girls, or interfere arbitrarily with their privacy.9 Thus, the evidence from this review reinforces the human rights imperative for full decriminalisation of abortion in all settings.

Reflecting the recognition across legal and health scholarship and domestic and international human rights law that criminalisation is not a sound regulatory approach to abortion, full or partial decriminalisation is beginning to occur. In some countries, parliaments have recently made legislative changes to remove criminal offences for women who access or avail of abortion, although providing abortion outside of the circumstances laid down in the law remains an offence.49 In others, parliaments have fully decriminalised abortion, although that is rare,50–52 and several superior courts have found that criminalisation of accessing or availing of abortion is unconstitutional.53 However, partial decriminalisation or practices of depenalisation or non-application of the law are insufficient as the open, informed and positive provision of abortion care remains hindered (Erdman and Cook, p. 13),54 and there are continuing impacts on health workers and healthcare facilities where provision of abortion remains criminalised. Health professionals increasingly express support for either full or partial decriminalisation, regardless of personal religious or ethical stance vis-à-vis abortion per se,55 and there is growing acknowledgement of the harms that are produced by abortion criminalisation (Erdman, p. 249).56 Formal decriminalisation does not necessarily create clarity in the community about the permissibility of abortion,57 suggesting that formal decriminalisation ought to be accompanied by government facilitating the provision of accurate and accessible information about the availability of abortion in a variety of formats and languages and in-keeping with the right to receive accurate and unbiased information on sexual and reproductive healthcare as reflected in, for example, Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.5 58 59

It is important to recall that in many jurisdictions criminalisation interacts with other abortion law and policy that may compound its effects, including the existence of grounds (which usually operate as exceptions or ‘defenses’ to general abortion-related offences). ‘Grounds-based’ access to abortion emerged to mitigate the effects of criminalisation, permitting abortion in limited circumstances. However, such restrictions, laws and policies not only themselves produce negative human rights effects including those resulting from delay, disproportionate impact on marginalised groups and denial of abortion even in circumstances where international human rights law makes clear it must be available, but also complicate abortion provision and health system organisation, create burdens within the criminal justice system, and contribute to the exceptionalisation and stigmatisation of abortion for both pregnant people and health workers.60 These broader effects combine with the human rights and public health impact of criminalisation outlined in this review to establish the significant burdens produced by criminalisation.

Limitations

This review has limitations. While its geographical scope is wide, with manuscripts reflecting 19 country contexts, the review only contains manuscripts published in English. Further research on the impact of criminalisation in a wider range of settings would be welcome. Furthermore, research on the impact of criminalisation of particular subpopulations of abortion seekers including people with diminished capacity and minors would benefit the overall evidence base. As a general matter, randomised controlled trials or comparative observational studies are not readily applicable to questions relating to the realisation of human rights applicable to abortion-related interventions, and studies do not always contain comparisons. Although this may be considered a limitation from a standard methodological perspective for systematic reviews, it does not impact on our ability to identify human rights law implications of law and policy interventions and thus is not a limitation for a review of this kind. Relatedly, standard tools for assessing risk of bias or quality, including GRADE,61 were unsuitable for this review which aimed to ensure effective integration of human rights into our understanding of the effects of criminalisation as a regulatory intervention in abortion law and policy. Thus, as explained in the published methodology,16 a wide variety of sources is engaged with.

Conclusion

This review identified evidence of the impacts of criminalisation on people seeking to access abortion and on abortion providers, and considered whether, and if so how, this demonstrates the incompatibility of criminalisation with substantive requirements of international human rights law. This review clearly points to impacts that have negative implications for health outcomes, health systems and human rights. It provides empirical evidence of the scale, complexity and severity of human rights violations associated with criminalisation and which have already been identified by human rights bodies. It also provides additional evidence to support the WHO’s recommendation for full decriminalisation of abortion, understood as ‘the complete decriminalisation of abortion for all relevant actors: removing abortion from all penal/criminal laws, not applying other criminal offences (eg, murder, manslaughter) to abortion, and ensuring there are no criminal penalties for having, assisting with, providing information about or providing abortion’.18 Given this, the need for states to fully decriminalise of abortion as a necessary step towards ensuring that abortion is available, accessible and of good quality is now firmly established.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @fdelond

FdL, AC, MIR, AF, MF and AL contributed equally.

Contributors: AL managed and is guarantor for the study. AL and FdL designed the review. AF and MF identified and extracted studies. AC and MIR analysed the data. AC undertook visualisation. FdL prepared the draft manuscript and revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript and revision.

Funding: This work was supported by the UNDP‐UNFPA‐UNICEF‐WHO‐World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), a cosponsored programme executed by the WHO (AL) (https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research-(srh)/human-reproduction-programme). Professor FdL also acknowledges the support of the Leverhulme Trust through the Philip Leverhulme Prize (FdL) https://www.leverhulme.ac.uk.

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.UN Special Rapporteur . Right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, Interim report to the general assembly (UN Doc. A/66/254), 2011

- 2.World Health Organization . Global abortion policies database, 2018. Available: https://abortion-policies.srhr.org/ [Accessed 29 Oct 2021].

- 3.Nabaneh S. The Gambia's political transition to democracy: is abortion reform possible? Health Hum Rights 2019;21:169–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheldon S. The decriminalisation of abortion: an argument for Modernisation. Oxf J Leg Stud 2016;36:334–65. 10.1093/ojls/gqv026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Human Rights Committee . Whelan v Ireland (UN Doc. CCPR/C/11/D/2425/2014); 2017.

- 6.Human Rights Committee . General Comment No. 28: Article 3 (the equality of rights between men and women) (2000) (UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add/10).

- 7.Human Rights Council . Un special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, report of the special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions on a gender-sensitive approach to arbitrary killings (UN Doc. A/HRC/35/23), 2017

- 8.Baer M. Abortion law and policy around the world: in search of decriminalisation. Health Hum Rights 2017;19:13–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Human Rights Committee . General Comment No. 36 on article 6 of the International covenant on civil and political rights, on the right to life (UN Doc. CCPR/C/GC/36); 2018.

- 10.CEDAW Committee . General recommendation No. 24, article 12 of the convention (women and health), (UN. Doc A/54/38/Rev.1, chap. I); 1999.

- 11.Human Rights Council . UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UN Doc. A/HRC/22/53)

- 12.CEDAW Committee . General recommendation No. 33 on women’s access to justice (2015) (UN Doc. CEDAW/C/GC/33).

- 13.CEDAW Committee . Report of the inquiry concerning the United Kingdom of great britain and Northern Ireland under article 8 of the optional protocol to the convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (un Doc. CEDAW/C/OP.8/GBR/1); 2018.

- 14.The Africa leaders' Declaration on safe, legal abortion as a human right [Accessed 20 January 2017].

- 15.African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights Protocol to the African charter on human and peoples' rights on the rights of women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol), AHG/Res, 240 (XXXI)

- 16.de Londras F, Cleeve A, Rodriguez MI, et al. Integrating rights and evidence: a technical advance in abortion guideline development. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e004141. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petticrew M, Knai C, Thomas J, et al. Implications of a complexity perspective for systematic reviews and guideline development in health decision making. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e000899. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Abortion care guideline; 2022. [PubMed]

- 19.Burris S, Ghorashi AR, Cloud LF, et al. Identifying data for the empirical assessment of law (ideal): a realist approach to research gaps on the health effects of abortion law. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e005120. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Costa C, Douglas H, Black K. Making it legal: abortion providers' knowledge and use of abortion law in New South Wales and Queensland. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;53:184–9. 10.1111/ajo.12035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Douglas H, Black K, de Costa C. Manufacturing mental illness (and lawful abortion): doctors' attitudes to abortion law and practice in New South Wales and Queensland. J Law Med 2013;20:560–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LaRoche K, Wynn LL, Foster A. ‘We have to make sure you meet certain criteria’: exploring patient experiences of the criminalisation of abortion in Australia. Public Health Res Pract 2020. 10.17061/phrp30342011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casseres L. Structural racism and the Criminalisation of abortion in Brazil. Sur International Journal on Human Rights 2018;28:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casas L, Vivaldi L. Abortion in Chile: the practice under a restrictive regime. Reprod Health Matters 2014;22:70–81. 10.1016/S0968-8080(14)44811-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramm A, Casas L, Correa S, et al. "Obviously there is a conflict between confidentiality and what you are required to do by law": Chilean university faculty and student perspectives on reporting unlawful abortions. Soc Sci Med 2020;261:113220. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Citizens’ Coalition for the Decriminalization of Abortion on Grounds of Health, Ethics and Fetal Anomaly . From hospital to jail: the impact on women of El Salvador’s total criminalization of abortion. Reproductive Health Matters 2014;22:52–60. 10.1016/S0968-8080(14)44797-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blystad A, Haukanes H, Tadele G, et al. The access paradox: abortion law, policy and practice in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:126. 10.1186/s12939-019-1024-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aiken A, Gomperts R, Trussell J. Experiences and characteristics of women seeking and completing at-home medical termination of pregnancy through online telemedicine in Ireland and Northern Ireland: a population-based analysis. BJOG 2017;124:1208–15. 10.1111/1471-0528.14401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aitken K, Patek P, Murphy ME. The opinions and experiences of Irish obstetric and gynaecology trainee doctors in relation to abortion services in Ireland. J Med Ethics 2017;43:778–83. 10.1136/medethics-2015-102866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Power S, Meaney S, O'Donoghue K. Fetal medicine specialist experiences of providing a new service of termination of pregnancy for fatal fetal anomaly: a qualitative study. BJOG 2021;128:676-684. 10.1111/1471-0528.16502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fathallah Z. Moral work and the construction of abortion networks: women's access to safe abortion in Lebanon. Health Hum Rights 2019;21:21–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clarke D, Mühlrad H. The impact of abortion Legalization on fertility and maternal mortality: new evidence from Mexico. University of Gothenburg Working Papers in Economics No 661 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedman J, Saavedra-Avendaño B, Schiavon R, et al. Quantifying disparities in access to public-sector abortion based on legislative differences within the Mexico City metropolitan area. Contraception 2019;99:160–4. 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koch E, Chireau M, Pliego F, et al. Abortion legislation, maternal healthcare, fertility, female literacy, sanitation, violence against women and maternal deaths: a natural experiment in 32 Mexican states. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006013. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Dijk MG, Ahued Ortega A, Contreras X, et al. Stories behind the statistics: a review of abortion-related deaths from 2005 to 2007 in Mexico City. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;118 Suppl 2:S87–91. 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gutiérrez Vázquez EY, Parrado EA. Abortion Legalization and childbearing in Mexico. Stud Fam Plann 2016;47:113–28. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2016.00060.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juarez F, Bankole A, Palma JL. Women's abortion seeking behavior under restrictive abortion laws in Mexico. PLoS One 2019;14:e0226522. 10.1371/journal.pone.0226522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henderson JT, Puri M, Blum M, et al. Effects of abortion legalization in Nepal, 2001-2010. PLoS One 2013;8:e64775. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aiken ARA, Padron E, Broussard K, et al. The impact of Northern Ireland’s abortion laws on women’s abortion decision-making and experiences. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2019;45:3–9. 10.1136/bmjsrh-2018-200198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shahawy S. The unique landscape of abortion law and access in the occupied Palestinian territories. Health Hum Rights 2019;21:47–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Center for Reproductive Rights “ . Forsaken lives: the harmful impact of the Philippine criminal abortion ban; 2010.

- 42.Påfs J, Rulisa S, Klingberg-Allvin M, et al. Implementing the liberalized abortion law in Kigali, Rwanda: ambiguities of rights and responsibilities among health care providers. Midwifery 2020;80:102568. 10.1016/j.midw.2019.102568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suh S. Rewriting abortion: deploying medical records in jurisdictional negotiation over a forbidden practice in Senegal. Soc Sci Med 2014;108:20–33. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arambepola C, Rajapaksa LC. Decision making on unsafe abortions in Sri Lanka: a case-control study. Reprod Health 2014;11:91. 10.1186/1742-4755-11-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nara R, Banura A, Foster AM. Exploring Congolese refugees' experiences with abortion care in Uganda: a multi-methods qualitative study. Sex Reprod Health Matters 2019;27:262–71. 10.1080/26410397.2019.1681091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Antón J-I, Ferre Z, Triunfo P. Evolution of adolescent fertility after decriminalization of abortion in montevideo, Uruguay. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2016;134:S24–7. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antón J-I, Ferre Z, Triunfo P. The impact of the legalisation of abortion on birth outcomes in Uruguay. Health Econ 2018;27:1103–19. 10.1002/hec.3659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) . CESCR General Comment No. 15: the right to the highest attainable standard of health (Art. 12) (UN Doc. E/C.12/2000/4), 2000

- 49.Health (Regulation of termination of pregnancy) act, 2018

- 50.Northern Ireland (Executive formation etc) act, 2019

- 51.Abortion reform act, 2019

- 52.Abortion legislation act, 2020

- 53.Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation . Declaration of invalidity No. 683; 2021. [Accessed 7 Sep 2021].

- 54.Erdman JN, Cook RJ. Decriminalization of abortion - A human rights imperative. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2020;62:11–24. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Finley Bab C, Casas L, Ramm A. Medical and midwifery student attitudes toward moral acceptability and legalisation of aborton, following decriminalzation of abortion in Chile. Sex Reprod Health 2020;24:100502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Erdman J. Harm production: an argument for decriminalization. In: Miller AM, Roseman MJ, eds. Beyond virtue and vice - rethinking human rights and criminal law. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pérez B, Sagner-Tapia J, Elgueta HE. [Decriminalization of abortion in Chile: a mixed method approach based on perception of abortion in the community population]. Gac Sanit 2020;34:485–92. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.CESCR . General Comment No 22 on the right to sexual and reproductive health (Article 12 of the International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights) (UN Doc. E/C/12/GC/22); 2016.

- 59.CRPD . General Comment No. 3 on article 6: women and girls with disabilities, (UN Doc. CRPD/C/GC/3); 2016.

- 60.de Londras F, Cleeve A, Rodriguez MI, et al. The impact of 'grounds' on abortion-related outcomes: a synthesis of legal and health evidence. BMC Public Health 2022;22:936. 10.1186/s12889-022-13247-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, et al. Grade evidence to decision (ETD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: introduction. BMJ 2016;353:i2016. 10.1136/bmj.i2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2022-010409supp001.pdf (199.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.