Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the association of red blood cell (RBC), hemoglobin (Hb), red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation (RDW-CV), and red cell distribution width-standard deviation (RDW-SD) with preoperative deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty (TJA).

Methods

A total of 2059 TJA patients were enrolled. We used the ratios of RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD to DVT before TJA to create the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve, thereby calculating the cut-off values and the area under the curve (AUC). The patients were categorized into groups based on cut-off value, and risk factors for DVT before TJA were subsequently analyzed. We included the variates that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis in the multivariate binary logistic regression analysis.

Results

Preoperative DVT occurred in 107 cases (5.20%). Based on the ROC curve, we found that the AUC for RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD were 0.658, 0.646, 0.568, and 0.586, respectively. Multivariate binary regression analysis revealed that the risk of preoperative DVT in TJA patients with RBC≤3.92*109 /L, Hb≤118g/L, RDW-CV≥13.2%, and RDW-SD≥44.6fL increased 3.02 (P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) [2.0–4.54]), 2.15 (P < 0.001, 95% CI [1.42–3.24]), 1.54 (P = 0.038, 95% CI [1.03–2.3]), and 1.98 times (P = 0.001, 95% CI [1.32–2.98]), respectively. The risk of preoperative DVT in patients with corticosteroid use increased approximately 2.6 times (P = 0.002, 95% CI [1.22–5.81]).

Conclusion

We found that decreased RBC and Hb, increased RDW-CV and RDW-SD, and corticosteroid use were independent risk factors for preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA.

Keywords: red blood cell, hemoglobin, red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation, red blood cell-standard deviation, total joint arthroplasty, deep vein thrombosis

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is the third most common cardiovascular disease, following myocardial infarction and stroke.1 Total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are common procedures used to treat hip and knee osteoarthritis, resulting in excellent patient-reported outcomes.2, 3 VTE is considered as one common serious complication after total joint arthroplasty (TJA) and an important cause of morbidity and mortality, especially in hospitalized patients. DVT incidence may reach 40–60% without prophylaxis and PE may occur in 0.5–2% of the patients after TJA.4, 5 The incidence of DVT before TKA is 6.85–17.9%.6, 7 Song K et al reported that up to 29.4% of the patients undergoing THA had preoperative DVT and 66.7% that were postoperatively diagnosed with VTE had the thrombosis on the same sites as before the surgery.8 Peripheral types of DVT in small size should be taken seriously enough. Detachment of small thrombi may lead to PE.9 Therefore, it is very important to identify the risk factors of preoperative DVT in TJA patients.

Red blood cells (RBCs) are flexible, biconcave anucleated cells derived from bone marrow10 and play a prothrombotic role in blood coagulation in VTE by making the blood more viscous and pushing platelets (PLTs) toward the vessel wall. Therefore, DVT begins with the aggregation of RBCs, fibrin, and PLTs.11 Hemoglobin (Hb) is a special protein in the RBC that carries oxygen. The red blood cell distribution width (RDW) is a measurement of the size of RBC, thus “width” refers to the width of the distribution curve rather than the width of cells, and it is also an index of heterogeneity of RBC.12 RDW and RBCs affect the well-known Virchow's triad of blood stasis, endothelial injury, and hypercoagulability, making them important factors in pro-thrombotic states such as PE and DVT.13 Xiong et al found that the decreased RBC count was a risk factor for preoperative DVT before TKA.6 Tang et al demonstrated that change in RDW was an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with chronic heart failure, and the risk ratios of mortality for 1% increase in RDW were 1.08.14 Zehir S found that RDW>14.5% was associated with increased one-year mortality in hip fracture patients with partial prostheses.15 Bucciarelli et al demonstrated that those with an RDW>14.6% was independently correlated with a 2.5 times higher risk of first VTE than those with an RDW≤14.6%; additionally, high RDW was associated with a 3.19-fold increased risk of PE.16 Ellingsen TS et al observed that patients with RDW in the upper quartile had a 1.5-fold higher risk of VTE than those in the lowest quartile. They reported high RDW as a risk factor for incident VTE and RDW as a predictor of all-cause mortality in VTE patients.17 Yin P et al found that higher levels of RDW at the time of admission and discharge in hip fracture patients were associated with higher death risk.18 A retrospective study by Cheng X et al showed that patients with RDW-CV≥13.2 had a 1.536 times higher risk of DVT before TJA.19

Most previous studies focused on the predictive value of RBC and RDW on postoperative death of TJA patients and their impact on complications after TJA. In contrast, this study aimed to investigate the association of RBC, Hb, and RDW with preoperative DVT in patients (with osteoarthritis (OA)) undergoing TJA.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: A total of 2716 patients who (1) underwent TJA in our hospital between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2021, and (2) were diagnosed with OA or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) before surgery.

Exclusion criteria: (1) a history of VTE: 3 cases; (2) thrombophilia genetic disorders: 0 cases; (3) use of anticoagulation medications: 9 cases; (4) joint infection or tuberculosis: 19 cases; (5) tumors of the joints: 25 cases; (6) bone fractures: 343 cases; (7) no preoperative ultrasound records: 192 cases; (8) no RBC or RDW records: 66 cases. Finally, 657 patients were excluded and 2059 patients with TJA were enrolled.

Research Method

We created the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve by using the ratios of RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD to the incidence of preoperative DVT. The cut-off values for each of these indices and areas under curve (AUC) were calculated. We then divided the patients into groups and examined the risk factors for DVT before TJA. Based on the results of the deep vein ultrasound, patients were again divided into two groups: the DVT group and the non-DVT group. Then we conducted a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis to further verify. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study has been approved by Medical Research and Ethics Review (No. 184, 2022) and registered in the WHO International Clinical Trials Registration (ChiCRT2100054844).

Data Collection

We collected clinical data through the hospital's surgical anesthesia information system and electronic medical records. Patients’ basic information included: height, weight, body mass index (BMI), age, and gender. Medical records included: preoperative hypertension, diabetes, CHD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic bronchitis, RA, OA, cerebral infarction, cancer, renal failure, corticosteroid use, smoking, alcohol consumption, major surgery (major surgery requiring anesthesia (general, orthopedic, neurologic, or gynecologic surgery)20 in 12 months; preoperative laboratory examinations: blood type, RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, RDW-SD, and the result of low extremity vein ultrasound.

All patients were examined by Philips IE33 GE Vivid 9, C5-1, and 5–10Hz pulsed Doppler ultrasound. Each patient was co-diagnosed by two experienced sonographers. The positive criteria for DVT were venous incompressibility, intravascular filling defects, and lack of Doppler signal. We also collected the sites of DVT formation: distal and proximal and mixed thrombus formation.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 26.0 was used for statistical analyses. We created the ROC curve, thereby determining the cut-off values for RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD. Then the patients were divided into two groups: one group above and the other below the cut-off value. Risk factors were subsequently analyzed. For enumeration data, the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used. The results were represented in percentages (%). The variates that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to examine the association of preoperative RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD with preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA. P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

General Information of Participants

The mean age was 63.1 ± 12.1 years among all the enrolled TJA patients (with OA or RA), 71.4 ± 8.9 years in the DVT group, and 62.66 ± 12.1 years in the non-DVT group (Table 1). Preoperative OA was diagnosed in 1891 cases and RA in 168 cases. 1002 patients underwent TKA and 1057 underwent THA. Among them, 794 (38.56%) were male and 1265 (61.44%) were female. The preoperative comorbidities were hypertension (571 cases), diabetes (196 cases), and CHD (114 cases).

Table 1.

Summary of Patient Characteristics.

| Influencing factor | DVT (107) | Non-DVT (1952) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm) | 156.40 ± 6.6 | 158.02 ± 8.59 | 0.017 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.12 ± 9.59 | 61.33 ± 10.12 | 0.028 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 3.89 | 24.63 ± 4.77 | 0.364 |

| Age (year) | 71.4 ± 8.9 | 62.66 ± 12.1 | 0.000 |

| RBC (109/L) | 3.92 ± 0.55 | 4.23 ± 1.28 | 0.012 |

| Hb (g/L) | 115.8 ± 19.44 | 126 ± 17.03 | 0.000 |

| RDW-CV (%) | 13.75 ± 1.57 | 13.42 ± 1.49 | 0.029 |

| RDW-SD (fL) | 45.8 ± 4.0 | 44.8 ± 4.34 | 0.025 |

Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index; RBC: red blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; RDW-CV: red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation; RDW-SD: red blood cell-standard deviation; DVT: deep vein thrombosis.

P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Characteristics of DVT Formation

Among the 107 cases (5.2%) with DVT before TJA, there were 78 distal thrombus cases (72.9%), 13 proximal thrombus cases (12.15%), and 16 mixed thrombus cases (14.95%). Patients with proximal and mixed thrombi were implanted with an inferior vena cava filter before surgery, and distal thrombi were anticoagulated with low molecular weight heparin. Therefore, no PE occurred in our patient during the perioperative period. Analysis of preoperative RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD in patients undergoing TJA.

Analysis of Preoperative RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD in Patients Undergoing TJA

Our data showed that the DVT group had lower RBC and Hb while higher RDW-CV and RDW-SD than the non-DVT group. P value was lower than 0.05 (Table 1) (Table 2). As per the 2011 WHO guidelines21 (and the indicators used by our laboratory), when Hb<130g/L in men and <120g/L in women, it is defined as anemia. As shown in Table 3, RDW-CV and RDW-SD were markedly increased in the DVT group (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Univariate Analysis of Preoperative DVT Risk in Patients Undergoing TJA.

| Influencing factor | Chi-square test value | P |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 6.23 | 0.013 |

| Hypertension | 14.77 | 0.000 |

| Diabetes | 3.87 | 0.061 |

| CHD | 4.86 | 0.046 |

| COPD | 2.91 | 0.114 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 4.76 | 0.054 |

| Cerebral infarction | 6.18 | 0.027 |

| Major surgery in the last 12 months | 2.83 | 0.104 |

| Cancer | 2.03 | 0.181 |

| Renal failure | 4.47 | 0.092 |

| Depression | 0.22 | 0.639 |

| Corticosteroid | 7.42 | 0.015 |

| Smoking | 3.88 | 0.058 |

| Drinking | 0.96 | 0.410 |

| Blood type | 12.99 | 0.005 |

| Classification of RBC | 39.08 | 0.000 |

| Classification of Hb | 21.23 | 0.000 |

| Classification of HCT | 16.45 | 0.000 |

| Classification of RDW-CV | 5.60 | 0.022 |

| Classification of RDW-SD | 11.17 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index; DM: diabetes; RBC: red blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; RDW-CV: red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation; RDW-SD: red blood cell-standard deviation; DVT: deep vein thrombosis.

P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Table 3.

Comparison of RBC Correlation Indices of Anemia and Non-Anemia Group.

| Influencing factor | Anemia | Non-anemia | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBC (109/L) | 3.82 ± 1.18 | 4.5 ± 1.23 | 0.000 |

| Hb (g/L) | 110.6 ± 11.89 | 136.38 ± 11.6 | 0.000 |

| RDW-CV (%) | 13.75 ± 1.57 | 13.42 ± 1.49 | 0.000 |

| RDW-SD (fL) | 45.8 ± 4.0 | 44.8 ± 4.34 | 0.000 |

Abbreviations: RBC: red blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; RDW-CV: red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation; RDW-SD: red blood cell-standard deviation.

P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

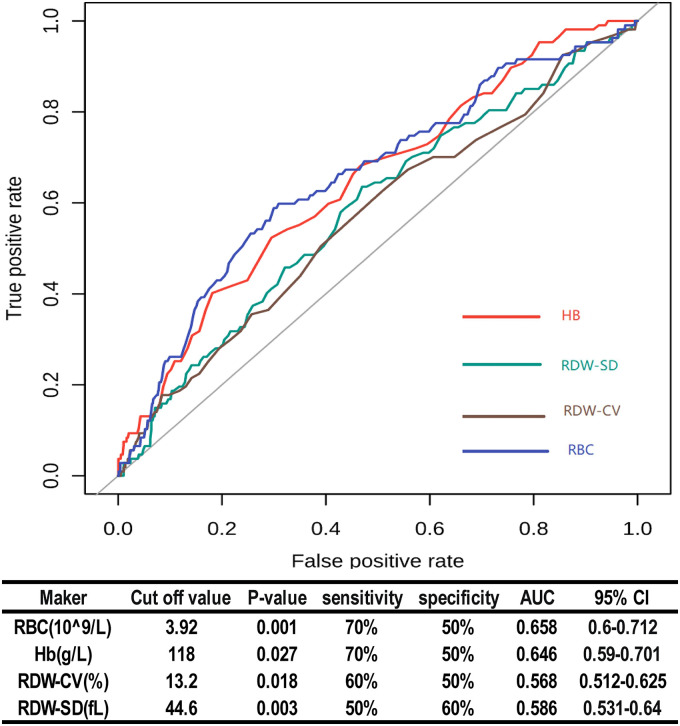

Based on the ROC curve, we found that the cut-off values for RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD were 3.92*109/L, 118g/L, 13.2%, and 44.6fL, respectively. AUCs for RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD were 0.658 (P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.6–0.712]), 0.646 (P = 0.027, 95% CI [0.59–0.701]), 0.568 (P = 0.018, 95% CI [0.512–0.625]), and 0.586 (P = 0.003, 95% CI [0.531–0.64]), respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagnostic performances of RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD for predicting DVT in patients undergoing TJA. Abbreviations: AUC: area under curve; CI: confidence interval; RBC: red blood cell; Hb: Hemoglobin; RDW-CV: red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation; RDW-SD: red blood cell-standard deviation; P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Analysis of High-Risk Factors of Preoperative DVT in Patients Undergoing TJA

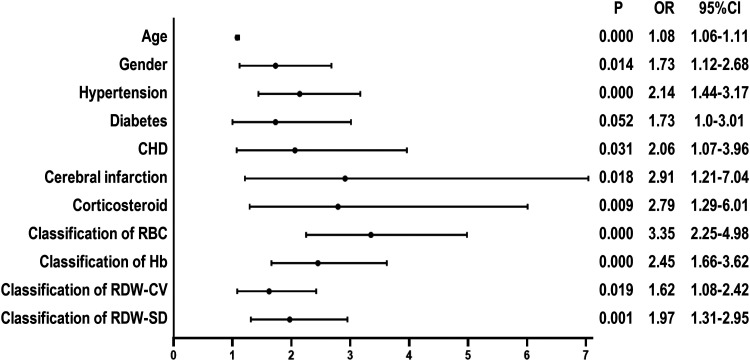

Univariate regression analysis found that the risk of preoperative DVT in TJA patients with RBC≤3.92*109/L, Hb≤118g/L, RDW-CV≥13.2%, and RDW-SD≥44.6fL increased by 3.35 (P < 0.001, 95% CI [2.25–4.98]), 2.45 (P < 0.001, 95% CI [1.66–3.62]), 1.62 (P = 0.019, 95% CI [1.08–2.42]), and 1.97 times (P = 0.001, 95% CI [1.31–2.95]), respectively. Furthermore, we also found that age, gender, hypertension, CHD, cerebral infarction, and corticosteroid use were risk factors for DVT before TJA (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Univariate logistic regression analysis of preoperative risk factors for DVT in patients undergoing TJA. Abbreviations: CHD: coronary heart disease; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RBC: red blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; RDW-CV: red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation; RDW-SD: red blood cell-standard deviation; P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

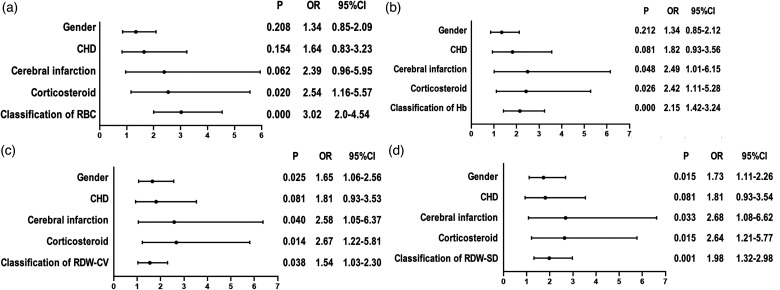

Considering the multicollinearity of RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis on these variables separately with age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, CHD, and corticosteroid (Figure 3). The analysis showed that the risk of preoperative DVT in TJA patients with RBC≤3.92*109/L, Hb≤118 g/L, RDW-CV≥13.2%, and RDW-SD≥44.6fL increased by 3.02 (P < 0.001, 95% CI [2.0–4.54]), 2.15 (P < 0.001, 95% CI [1.42–3.24]), 1.54 (P = 0.038, 95% CI [1.03–2.3]), and 1.98 times (P = 0.001, 95% CI [1.32–2.98]), respectively. The risk of preoperative DVT in patients with corticosteroid use increased by approximately 2.6 times (P = 0.002, 95% [1.22–5.81]).

Figure 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of preoperative risk factors for DVT in patients undergoing TJA. (a) Multivariate logistic regression analysis of RBC and preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA. (b) Multivariate logistic regression analysis of Hb and preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA. (c) Multivariate logistic regression analysis of RDW-CV and preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA. (d) Multivariate logistic regression analysis of RDW-SD and preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA. Abbreviations: CHD: coronary heart disease; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RBC: red blood cell; Hb: hemoglobin; RDW-CV: red cell distribution width-coefficient of variation; RDW-SD: red blood cell-standard deviation; P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Discussion

A retrospective study with a small sample size by Xu Z et al concluded that the RDW level cannot predict DVT in patients undergoing TJA.22 The reason why this study did not verify the association between RDW and DVT before TJA may be because its sample size was too small (only 110 cases). A retrospective study on risk factors for DVT before THA by Cheng X et al found the AUC for RDW of 0.532, the cut-off value of 15.89, a specificity of 88.2%, and a sensitivity of 18.2%.19 This study investigated acute thrombosis formation in hip fracture patients before TJA, and the preoperative AUC was comparably small (only 0.532). Different from these studies, the present study is the first one that has identified decreased RBC count and Hb, and increased RDW-CV and RDW-SD as independent risk factors for preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA, as well as the first study which has revealed the association between RDW and chronic thrombosis formation in patients undergoing TJA.

Decreased RBC and Hb

Both RBC and Hb were decreased in the DVT group in the present study, with cut-off values of 3.92*109/L and 118g/L, respectively. As per the 2011 WHO guidelines, when Hb<130g/L in men and <120g/L in women, it is defined as anemia.21 Hb is a special protein in the RBC that carries oxygen. According to the World Health Organization standards, patients with RBC≤3.92*109/L and Hb≤118g/L can be diagnosed with anemia. Feng L et al observed that preoperative anemia was an independent risk factor for hip fracture complicated with VTE in elderly patients in China.23 Xiong et al found that the decreased RBC count was a risk factor for preoperative DVT before TKA.6 Chadha identified anemia as an independent risk factor for preoperative DVT in patients with hip fractures.24 The present study found that RBC≤3.92*109/L and Hb≤118g/L were independent risk factors for preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA. Specifically, the risk of preoperative DVT in patients with RBC≤3.92*109/L and Hb≤118g/L before TJA increased by 3.02 and 2.15 times, respectively. The AUC for RBC was 0.658 (P < 0.001, 95% CI [0.6–0.712]), and that for Hb was 0.646 (P = 0.027, 95% CI [0.59–0.701]). Therefore, it is recommended that TJA patients with RBC≤3.92*109/L or Hb≤118g/L should be screened for preoperative DVT.

The DVT ratio of patients with anemia but normal RDW-SD or RDW-CV is 16.82%. Firstly, the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of these patients was less than 100 fL. Therefore, megaloblastic anemia is less likely. Secondly, we found that the PLT counts in our data were more than 100*109/L, and the neutrophils were more than 1.5 × 109/L in these patients. Thus, our patients were less likely to suffer from myelodysplastic syndromes. Finally, the cause of anemia due to chronic diseases cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, the DVT ratio of patients with normal hemoglobin but increased RDW-SD or RDW-CV was 23.36%. This ratio indicates a higher likelihood of iron-deficiency anemia. Our patients, with end-stage OA, had a long course of the disease, from years to decades, as both OA and RA patients are in long-term, chronic inflammatory conditions. Many cytokines and chemokines are detected in OA or RA.25, 26 Weiss et al found that inflammatory anemia can be divided into the following three stages: iron restriction, inflammatory suppression of erythropoietic activity, and decreased erythrocyte survival.27 In inflammation, interleukin 6 stimulates the hepatic synthesis of hepcidin, which binds to ferroportin, resulting in less intestinal absorption of iron and lower release of iron stored in hepatocytes and macrophages, leading to functional iron deficiency and decreased erythropoiesis.28 Therefore, the most likely cause of anemia in our DVT patients may be iron deficiency induced by inflammation, which eventually leads to anemia.

Increased RDW

An increased RDW reflects a profound deregulation of erythrocyte homeostasis involving both impaired erythropoiesis and abnormal RBC survival. A variety of underlying metabolic abnormalities may contribute to an increased RDW, such as inflammation, shortening of telomere length, alteration of erythropoietin (EPO) function, oxidative stress, poor nutritional status, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and RBC fragmentation.29 Lv H et al showed that an elevated RDW was associated with both short and long-term mortality in hip fracture patients.30 Higher levels of preoperative RDW were associated with less optimal outcomes after revision TJA.31 Yin P et al found that higher RDW levels at the time of admission and discharge were associated with a higher risk of death, and that the risk of death in patients with an RDW >14.5% increased 1.6-fold compared to those with RDW≤14.5%.18 A study on acute DVT by Cay N et al reported that an RDW >13.9% increased the risk of DVT incidence by 4.5 times; additionally, RDW>14.9% increased the risk of nonchronic proximal DVT by 12 times, and with increasing RDW levels, there was a graded increase in the risk of DVT incidence.32 A study by Bucciarelli et al demonstrated that those with an RDW>14.6% was independently associated with a 2.5-fold higher risk of first VTE than those with an RDW≤14.6%. Furthermore, high RDW levels were associated with a 3.19-fold increased risk of PE.16 Ellingsen TS et al found that VTE patients with RDW≥13.3% had a 30% higher risk of all-cause mortality after the first VTE event than those with RDW<13.3%. Individuals with RDW in the upper quartile had a 1.5 times higher risk of VTE than those in the lowest quartile. High RDW is a risk factor of incident VTE, and RDW is a predictor of all-cause mortality in VTE patients.17 This study was similar to the present one in terms of the cut-off value for RDW and increased risk for VTE. We found that the risk for preoperative DVT in patients with RDW-CV≥13.2% and RDW-SD≥44.6fL increased by 1.54 (P = 0.038, 95% CI [1.03–2.3]) and 1.98 (P = 0.001, 95% CI [1.32–2.98]) times, respectively. An increased RDW level was an independent risk factor for preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA.

The increase in RDW in our patients can be attributed to the following reasons. First, age can affect RDW. RBCs become smaller as they age, and a slight reduction in the rate of RBC turnover allows smaller cells to continue circulating, expanding the low-volume tail of the RBC population's volume distribution, and thereby increasing RDW.33 Therefore, RDW increases with age.33 The mean age of our patients was 63.1 ± 12.1 years, higher in the DVT group than the non-DVT group. Moreover, a mildly extended RBC lifespan is a previously unrecognized homeostatic adaptation common to a very wide range of pathologic states, compensating for subtle reductions in RBC output.33 Second, RDW reflects the inflammatory state of the body. Fujita B et al observed that RDW was associated with markers of inflammation, which suggested that the number of RDW reflected the severity of inflammation.34 Macdougall et al found that elevated RDW represented the underlying inflammatory state in overweight adolescents and inflammatory cytokines interfere with the maturation of RBCs in the bone marrow through multiple mechanisms.35 As mentioned earlier, our patients are in long-term, chronic inflammatory conditions. Many cytokines and chemokines are detected in OA and RA.25, 26 Inflammation is also strongly related to ineffective erythropoiesis. Some studies showed that inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, inhibit RBC maturation, thus promoting anisocytosis.36 Third, RDW is increased through the pathway of anemia. Inflammatory cytokines may directly inhibit EPO-induced RBC maturation,37 leading to anemia. Anemia in turn induces the body to increase EPO. Decreased EPO results in the elevation of RDW.38 RBC clearance delay adaptively compensates for the mild anemia associated with many of the diseases linked to elevated RDW, maintaining circulating red cell mass and oxygen carrying capacity despite reduced RBC output.33 A delay in RBC clearance not only increases RDW but also enables cells to circulate beyond the time when they would ordinarily have been cleared, thus increasing the average RBC age and lifespan.33

Mechanism of Decreased RBC and Hb, Increased RDW, and Preoperative DVT in Patients Undergoing TJA

RDW is a clinical indicator of pro-thrombotic status and it measures the sizing variability of RBCs based on MCV.39 When there is an increasing number of small or large RBCs, a condition known as anisocytosis, which is characterized by a high RDW, occurs.40 Chronic inflammation in our patients led to anemia (a decrease in RBC and Hb), which promoted an increase in EPO. Increased RDW levels were found to be a powerful stimulation of erythropoiesis by EPO, according to Golcuk Y et al.41 EPO increased significantly with increasing RDW levels.42 There is a specific relationship between inflammatory cytokines and RDW. Patients with a higher RDW level have notably elevated IL-6. Higher RDW is associated with low Hb, moderately depressed MCV, and high EPO.42 Østerud B et al described a novel mechanism by which RBCs promote procoagulant and proinflammatory sequelae of WBC exposure to LPS, likely through the action of RBC-DARC in the microenvironment(s) that bring monocytes and RBCs in close proximity.43 RBCs are thought to mediate major proinflammatory and procoagulant events in circulation, which is a notion supported by Østerud B et al.43 Anisocytosis, according to Yu FT et al, could increase blood viscosity in VTE, making blood flow more stagnant; additionally, increased blood cell contact with endothelial walls could trigger thrombosis by increased PLT and fibrin activation.44 Faes C et al also found that RDW was negatively correlated with erythrocyte deformability.45 Furthermore, in spontaneous thrombosis, increased RDW levels have shown an obvious relationship with the decreased RBC deformability,46 which is the major trigger point of increased local blood viscosity,44 RBC aggregation, and thrombosis.47 Hence, it may be suggested that increased RDW enhances the packing ability of RBCs, resulting in complex 3D clumps which in turn increase the local blood viscosity and facilitates thrombosis.48

In short, our patients, with end-stage osteoarthritis, were in long-term, chronic inflammatory conditions. The inflammatory state leads to the decrease in RBC and Hb, while the equivalent increase of RDW is a compensatory reaction of RBC decrease to the body. RDW increase represents the increase of RBC heterogeneity, compensatorily prolonged RBC lifespan, and reduced RBC deformability, and it accumulates in the local area of joint inflammation, thus inducing DVT formation. As RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD can be obtained from the complete blood count, no extra financial burden will be imposed on patients. Therefore, compared to other inflammatory cytokines, they are more clinically accessible and more advantageous in predicting DVT formation before TJA. Therefore, we recommend their clinical application.

In this study, the correlation with DVT in TJA patients was explored by using materials such as preoperative medical history, preoperative laboratory examinations, and preoperative auxiliary examinations. However, this study has certain limitations. As a retrospective study, some data are incomplete. The AUCs for RBC, Hb, RDW-CV, and RDW-SD were 0.658, 0.646, 0.568, and 0.586, respectively. Future studies with a bigger sample size and more data might be needed to further verify the association between RBC indices and preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA.

Conclusion

We found that decreased RBC and Hb, increased RDW-CV and RDW-SD, and corticosteroid use were independent risk factors for preoperative DVT in patients undergoing TJA. Patients with RBC≤3.92*109 /L, Hb≤118g/L, RDW-CV≥13.2%, or RDW-SD≥44.6fL should be screened for preoperative DVT before TJA.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Xiaojuan Xiong, Ting Li, Shuang Yu, and Bo Cheng contributed to the conception and design of the study. Xiaojuan Xiong, Ting Li, and Shuang Yu: contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. Xiaojuan Xiong wrote the manuscript. Bo Cheng revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent to Participate: As this was a retrospective study, and data were analyzed anonymously, informed consent was therefore waived by the committee.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Sharing Statement: The data used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval: This study has been approved by Medical Research and Ethics Review (No. 184, 2022).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Xiaojuan Xiong https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5693-0544

Ting Li https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3941-9602

Shuang Yu https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4726-7055

References

- 1.Goldhaber SZ. Venous thromboembolism: epidemiology and magnitude of the problem. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2012;25(3):235-242. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2012.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachmeier CJ, March LM, Cross MJ, et al. A comparison of outcomes in osteoarthritis patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement surgery. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(2):137-146. doi: 10.1053/joca.2000.0369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, et al. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):57-63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell RD, Huo MH. Apixaban and rivaroxaban decrease deep venous thrombosis but not other complications after total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9):1477-1481. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang CJ, Wang JW, Chen LM, et al. Deep vein thrombosis after total knee arthroplasty. J Formos Med Assoc. 2000;99(11):848-853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiong X, Cheng B. Preoperative risk factors for deep vein thrombosis in knee osteoarthritis patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty [published online ahead of print, 2021 Oct 26]. J Orthop Sci. 2021;S0949-2658(21)00344-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2021.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bala A, Huddleston JI, 3rd, Goodman SB, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after TKA: aspirin, warfarin, enoxaparin, or factor Xa inhibitors?. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(9):2205-2213. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5394-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song K, Yao Y, Rong Z, et al. The preoperative incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and its correlation with postoperative DVT in patients undergoing elective surgery for femoral neck fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(10):1459-1464. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2535-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith EB, Parvizi J, Purtill JJ. Delayed surgery for patients with femur and hip fractures-risk of deep venous thrombosis. J Trauma. 2011;70(6):E113-E116. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31821b8768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aleman MM, Walton BL, Byrnes JR, et al. Fibrinogen and red blood cells in venous thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2014;133(Suppl 1(0 1)):S38-S40. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.03.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuroiwa Y, Yamashita A, Miyati T, et al. MR Signal change in venous thrombus relates organizing process and thrombolytic response in rabbit. Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;29(7):975-984. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2011.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ertop S, Bilici M, Engin H, et al. Red cell distribution width has a predictable value for differentiation of provoked and unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2016;32(4):481-487. doi: 10.1007/s12288-015-0626-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson T, Shantsila E, Lip GY. Mechanisms of thrombogenesis in atrial fibrillation: Virchow’s triad revisited. Lancet. 2009;373(9658):155-166. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60040-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cauthen CA, Tong W, Jain A, et al. Progressive rise in red cell distribution width is associated with disease progression in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012;18(2):146-152. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zehir S, Sipahioğlu S, Ozdemir G, et al. Red cell distribution width and mortality in patients with hip fracture treated with partial prosthesis. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48(2):141-146. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2014.2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bucciarelli P, Maino A, Felicetta I, et al. Association between red cell distribution width and risk of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2015;136(3):590-594. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellingsen TS, Lappegård J, Skjelbakken T, et al. Red cell distribution width is associated with incident venous thromboembolism (VTE) and case-fatality after VTE in a general population. Thromb Haemost. 2015;113(1):193-200. doi: 10.1160/TH14-04-0335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin P, Lv H, Li Y, et al. Hip fracture patients who experience a greater fluctuation in RDW during hospital course are at heightened risk for all-cause mortality: a prospective study with 2-year follow-up. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(7):1559-1567. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4516-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng X, Fan L, Hao J, et al. Red cell distribution width-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (RHR): a promising novel predictor for preoperative deep vein thrombosis in geriatric patients with hip fracture. Clin Interv Aging. 2022;17:1319-1329. Published 2022 Sep 1. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S375762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, et al. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):809-815. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity (No. WHO/NMH/NHD/MNM/11.1). World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu Z, Li L, Shi D, et al. The level of red cell distribution width cannot identify deep vein thrombosis in patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2015;26(3):298-301. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng L, Xu L, Yuan W, et al. Preoperative anemia and total hospitalization time are the independent factors of preoperative deep venous thromboembolism in Chinese elderly undergoing hip surgery. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020;20(1):72. Published 2020 Apr 2. doi: 10.1186/s12871-020-00983-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung CL, Ang SB, Chadha M, et al. An updated hip fracture projection in Asia: the Asian federation of osteoporosis societies study. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2018;4(1):16-21. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Bosch MHJ, van Lent PLEM, van der Kraan PM. Identifying effector molecules, cells, and cytokines of innate immunity in OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2020;28(5):532-543. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim KW, Kim HR, Kim BM, et al. Th17 cytokines regulate osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(11):3011-3024. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss G, Ganz T, Goodnough LT. Anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2019;133(1):40-50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-06-856500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lasocki S, Longrois D, Montravers P, et al. Hepcidin and anemia of the critically ill patient: bench to bedside. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(3):688-694. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182065c57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salvagno GL, Sanchis-Gomar F, Picanza A, et al. Red blood cell distribution width: a simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2015;52(2):86-105. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2014.992064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lv H, Zhang L, Long A, et al. Red cell distribution width as an independent predictor of long-term mortality in hip fracture patients: a prospective cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(1):223-233. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aali-Rezaie A, Alijanipour P, Shohat N, et al. Red cell distribution width: an unacknowledged predictor of mortality and adverse outcomes following revision arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(11):3514-3519. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cay N, Unal O, Kartal MG, et al. Increased level of red blood cell distribution width is associated with deep venous thrombosis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24(7):727-731. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32836261fe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rezende SM, Lijfering WM, Rosendaal FR, et al. Hematologic variables and venous thrombosis: red cell distribution width and blood monocyte count are associated with an increased risk. Haematologica. 2014;99(1):194-200. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.083840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujita B, Strodthoff D, Fritzenwanger M, et al. Altered red blood cell distribution width in overweight adolescents and its association with markers of inflammation. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8(5):385-391. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macdougall IC, Cooper A. The inflammatory response and epoetin sensitivity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(Suppl 1):48-52. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_1.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lappé JM, Horne BD, Shah SH, et al. Red cell distribution width, C-reactive protein, the complete blood count, and mortality in patients with coronary disease and a normal comparison population. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412(23-24):2094-2099. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierce CN, Larson DF. Inflammatory cytokine inhibition of erythropoiesis in patients implanted with a mechanical circulatory assist device [published correction appears in perfusion. 2005 may;20(3):183]. Perfusion. 2005;20(2):83-90. doi: 10.1191/0267659105pf793oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.La Ferla K, Reimann C, Jelkmann W, et al. Inhibition of erythropoietin gene expression signaling involves the transcription factors GATA-2 and NF-kappaB. FASEB J. 2002;16(13):1811-1813. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0168fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao Y, Yang C, Bakeer B. Prognostic value of red blood cell distribution width in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(18):e25571. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riedl J, Posch F, Königsbrügge O, et al. Red cell distribution width and other red blood cell parameters in patients with cancer: association with risk of venous thromboembolism and mortality. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e111440. Published 2014 Oct 27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golcuk Y, Golcuk B, Elbi H. Relation between red blood cell distribution width and venous thrombosis. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117(7):1196-1197. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen LA, Felker GM, Mehra MR, et al. Validation and potential mechanisms of red cell distribution width as a prognostic marker in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2010;16(3):230-238. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Østerud B, Unruh D, Olsen JO, et al. Procoagulant and proinflammatory effects of red blood cells on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated monocytes. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(9):1676-1682. doi: 10.1111/jth.13041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu FT, Armstrong JK, Tripette J, et al. A local increase in red blood cell aggregation can trigger deep vein thrombosis: evidence based on quantitative cellular ultrasound imaging. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(3):481-488. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04164.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faes C, Ilich A, Sotiaux A, et al. Red blood cells modulate structure and dynamics of venous clot formation in sickle cell disease. Blood. 2019;133(23):2529-2541. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel KV, Mohanty JG, Kanapuru B, et al. Association of the red cell distribution width with red blood cell deformability. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;765:211-216. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4989-8_29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hathcock JJ. Flow effects on coagulation and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(8):1729-1737. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000229658.76797.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vayá A, Suescun M. Hemorheological parameters as independent predictors of venous thromboembolism. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2013;53(1-2):131-141. doi: 10.3233/CH-2012-1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]