Abstract

Autistic young people in mainstream schools often experience low levels of peer social support, have negative perceptions of their differences and feel disconnected from their school community. Previous research findings have suggested that encouraging autistic young people to explore autistic culture and spending time with autistic peers may be associated with more positive outcomes. Autism-specific peer support is a framework that may support this process. Thirteen participants (eight male/five female) completed semi-structured interviews, exploring the idea of autism-specific peer support within mainstream schools and the practicalities of how it may work within a school setting. Thematic analysis was applied, and three themes are reported: (1) neurodiversity and an ethos of inclusivity, (2) flexibility and (3) benefits and challenges of embedding peer support in the wider school community. The idea of autism-specific peer support for autistic pupils in mainstream secondary schools was generally positively received. Peer support may provide a unique opportunity for autistic pupils to interact in a natural, comfortable way; share useful strategies; and build their identities. Nevertheless, careful design, training and ongoing support, alongside awareness of the rights, needs and preferences of individual pupils involved are likely to be crucial in ensuring the success of any peer support programme.

Lay abstract

Autistic young people may struggle in mainstream schools and feel disconnected from their peers and their school. We know that autistic adults can benefit from spending time with other autistic people, but we don’t know if this is the case for younger autistic people. We conducted interviews with 13 autistic young adults in the United Kingdom who recently left mainstream schooling. We asked them if they would have been interested in being involved in autistic peer support when they were at school, and if so, what that peer support should look like. Results indicated that autistic young people were enthusiastic about the idea of peer support. They thought it was important that peer support was flexible to suit their needs at different times, as well as inclusive, positive, and embracing neurodiversity. They also discussed the potential benefits and difficulties of having a peer support system within a school setting. This adds to the growing body of research on the potential benefits of autistic-autistic interactions on autistic people’s well-being and sense of belonging. Findings can be used to help design pilot peer support projects in schools that can be tested to see how effective they are.

Keywords: adolescence, autism, mainstream education, mental health, neurodevelopmental conditions, neurodiversity, peer support, school

Introduction

The number of autistic pupils in mainstream school is increasing (Symes & Humphrey, 2010); however, the successful inclusion of autistic pupils in mainstream schools is a complex process (Morewood et al., 2011). Autistic pupils are at a high risk of negative experiences (Morewood et al., 2011; The National Autistic Society, Scottish Autism, Children in Scotland, 2018): many report low levels of peer social support (Hoza, 2007; Symes & Humphrey, 2011) and high levels of bullying, and rejection by their peers (Fink et al., 2015). Autistic pupils participate less in class (Maciver et al., 2019), feel more disconnected from their school community (Hebron, 2018) and are more likely to be excluded from school than their non-autistic classmates (Martin, 2014; Paget et al., 2018).

Although autistic pupils have social and communicative styles that differ from non-autistic people (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), autistic pupils understand the concept of friendship, and many want to have friends (Cresswell et al., 2019; Marton et al., 2015). For young people, building social relationships is important: having one or two close friends can positively impact later adjustment, cushion the impact of stressful life events (Miller & Ingham, 1976), improve school transitions (Aikins et al., 2005), enhance self-esteem, and decrease anxiety and depressive symptoms (Buhrmester, 1990).

To support and facilitate friendship building, many school-based interventions focus on teaching neurotypical social skills, minimising overtly non-typical behaviours and using normative strategies to improve peer interactions and relationships (Gates et al., 2017). As the social skills of neurotypical people are considered unimpaired, it is commonly perceived that they will provide the best support to autistic people (Haney, 2012), thus in mainstream settings autistic pupils are often paired with neurotypical pupils in classes and in social interventions (Haney, 2012). In addition, social skills interventions are often held up as the gold standard in terms of providing autistic individuals with the tools to navigate a predominantly neurotypical environment (Lorenc et al., 2018).

While social skills training provides autistic young people with knowledge of the rules and mechanisms of non-autistic communication, such interventions inherently promote the assumption that neurotypical social norms are the ‘correct’ way to interact with others (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2018). Recent commentary suggests that many social skills interventions are unethical in that they stigmatise authentically autistic ways of being and attempt to make autistic individuals appear more ‘normal’ (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2018; Milton, 2016; Wilkenfeld & McCarthy, 2020). Developing and maintaining a ‘mask’ of normative social behaviour, as is implicitly encouraged by social skills training, requires a prolonged, exhausting effort for autistic people (Bargiela et al., 2016; Hull et al., 2017), causes anxiety and stress (Cage et al., 2018; Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019), and increases suicide risk (Cassidy et al., 2018). Adolescents often have negative perceptions of being neurodivergent, believing that they have a ‘bad brain’ (Hodge et al., 2019; Humphrey & Lewis, 2008). In response, autistic people have stressed the importance of schools supporting autistic differences, rather than pathologising and minimising natural behaviours. It is therefore pertinent to examine interventions which enhance the well-being of autistic individuals without further stigmatising authentically autistic ways of being in the world.

Peer support

One potential model for supporting autistic people which does not rely on minimising natural behaviours is autism-specific peer support. The peer support model assumes that shared experience of a phenomenon enhances the development of an empathetic supportive relationship (Repper & Carter, 2011). In the context of education, it is defined as ‘programmes which . . . use students themselves to help others learn and develop emotionally, socially or academically’ (Houlston et al., 2009, p. 328). Peer support structures can take several forms, such as mentoring, befriending and support groups (Bradley, 2016). Peer support within education has been shown to have several benefits, including providing a cost-effective personalised supplement to formal support mechanisms, the promotion of rapport due to proximity in age and increased well-being of both the mentor and the mentee (Appel, 2011; Hillier et al., 2019; Jacobi, 1991; MacLeod, 2010).

Education-based peer support programmes may be particularly helpful for those in minority groups, and peer support efficacy has been studied in marginalised populations such as care experienced young people (Biggs et al., 2020); Hispanic students (Holloway-Friesen, 2021); and lesbian, gay and bisexual students (Fetner et al., 2012; Lark & Croteau, 1998). Peer support programmes can combat the negative consequences of social isolation and marginalisation, address the importance of building community and provide a space for pupils and students in a minority to develop their own identities, rather than being expected to adhere to majority group norms (Fetner et al., 2012). Peer support can increase academic self-efficacy, enhance feelings of belonging and improve self-confidence (Holloway-Friesen, 2021; Rasheem et al., 2018). However, intersectionality must also be considered: young people have multiple identities. Peer support programmes have been shown to have strong benefits particularly for those with multiple intersecting minority identities, for example, with racial and gender identities (Rasheem et al., 2018). School-based peer support can have a profoundly positive impact both on individuals engaging with the programme and on the wider school community in terms of raising awareness and understanding of minority identities (Fetner et al., 2012; Griffin et al., 2004).

Peer support for autistic young people in mainstream schools

Some peer-mediated interventions for autistic young people have been delivered in schools, targeting, for example, academic skills and classroom behaviour via individual and class-wide peer tutoring and co-operative learning groups (Dugan et al., 1995; Kamps et al., 1994, 1995; McCurdy & Cole, 2014; Ward & Ayvazo, 2006). Some have also examined school-based peer support to enhance social opportunities and engagement for autistic pupils, involving non-autistic students playing a mentoring or befriending role to autistic students (Bambara et al., 2016; Bottema-Beutel et al., 2016; Bradley, 2016; Brain & Mirenda, 2019; Carter et al., 2017; Gardner et al., 2014; Hochman et al., 2015; Kretzmann et al., 2015; Sreckovic et al., 2017). These studies have had generally positive results, and there are advantages of having mentorship relationships between non-autistic and autistic peers, including promoting the social inclusion of the autistic students, enabling students to learn from one another (Bradley, 2016), providing peer support in relation to other aspects of identity (e.g. race, gender and sexual orientation) and bridging the ‘empathy gap’ that results from non-autistic people’s lack of understanding of the autistic experience (Milton, 2012).

However, in the existing literature on peer support for autistic people, ‘peer’ consistently refers to a non-autistic person (Rosqvist, 2018). This contrasts with the commonly employed meanings of this term in other areas of practice where peer support refers to the (often bidirectional) provision of support between individuals who have a mutually shared experience (Sunderland & Mishkin, 2013). While all young people in school will have some shared experience, this does speak to a key tension in the existing peer support literature: it is routinely non-autistic classmates who are recruited to improve the social integration of their autistic peers, by modelling neurotypical norms in social skills and providing access to existing peer networks (Carter et al., 2014, 2017; Hochman et al., 2015). Given that the heart of peer support is shared experience or commonality (Mead & MacNeil, 2006), it is surprising that the topic of autistic peer support (i.e. where autistic pupils support one another) has so far been under-explored. Indeed, there is evidence that autistic people may find autism-specific peer support more desirable than other types of social support; Kim and Crowley (2021) showed that autistic college students want more opportunities to connect with other autistic students; in contrast, Accardo et al. (2019) reported in their study that few autistic college students had attended, or preferred to attend, social skills groups. To our knowledge, no research has examined the potential benefits of school-based autistic–autistic peer support.

Teachers of autistic pupils have suggested that a framework supporting autistic pupils to engage with other autistic pupils within mainstream schools might be beneficial to develop a positive sense of self (Hodge et al., 2019). Many autistic pupils may experience marginalisation in mainstream school, and the opportunity for positive interpersonal interactions and positive social contexts may be crucial in developing self-understanding (Williams et al., 2019). Furthermore, autistic peer support programmes could provide space for autistic pupils to interact with each other without having to mask natural behaviours, a common concern for autistic adolescents (Bernardin et al., 2021). While there is little, if any, existing research on such programmes, studies with autistic adults do point to the potential benefits and positive outcomes of such an approach. For example, autistic adults may define or experience sociality in different ways to non-autistic people (Fletcher-Watson & Crompton, 2019; Rosqvist, 2019) and autistic people report increased feelings of comfort and ease around other autistic people (Crompton, Hallett, et al., 2020; Sinclair, 2010). In addition, autistic adults have reflected that during their school years they felt more understood by their autistic peers than by their non-autistic classmates (MacMillan et al., 2018). In autistic adults, feeling part of an autistic community reduces suicidality (Cassidy et al., 2018), and self-acceptance and pride in being autistic is linked to lower symptoms of depression (Cage et al., 2018). In the current climate of interventions which prioritise reduction of autistic traits, encourage masking and camouflaging and blending into a neurotypical environment, it is crucial to explore new forms of support by and for autistic people, which centre around empowerment, self-knowledge and community connection (Botha et al., 2020; Bottema-Beutel et al., 2018).

The current study

Although there is evidence to suggest that autistic peer support could be a valuable mechanism for supporting autistic young people, the extent to which autistic peer support within mainstream schools is desirable or feasible is currently unknown. In this study, we use a qualitative methodology to explore the experiences of young autistic people who have completed mainstream education (within the last 12 years), examining their perspectives on autistic peer support within the context of their school experience more broadly, including their support experiences and preferences at school, peer relationships and autistic identity.

Methods

This study used a qualitative design, featuring semi-structured interviews analysed thematically. This study received ethical approval from the University of Edinburgh Moray House School of Education and Sport Research Ethics Committee.

Participants

Participants were 13 autistic young adults (see Table 1 for demographic information), who met the following eligibility criteria: (1) aged 18–30 years, (2) received a diagnosis of autism, Asperger’s syndrome, or another ‘on the spectrum’ diagnosis prior to leaving school (3) attended a mainstream secondary school in the United Kingdom and (4) fluent English speaker. Participants were recruited through our project website, local autism organisations and social media.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information.

| ID | Age (years) | Gender | Age of diagnosis (years) | Year started secondary school | N years at secondary school | AQ score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 | Male | 10 | 2012 | 6 | 28 |

| 2 | 28 | Male | 4 | 2004 | 6 | 38 |

| 3 | 28 | Female | 3 | 2003 | 7 | 43 |

| 4 | 28 | Male | 13 | 2002 | 5 | 35 |

| 5 | 19 | Female | 10 | 2011 | 7 | 35 |

| 6 | 29 | Male | 8 | 2002 | 5 | 41 |

| 7 | 26 | Male | 9 | 2004 | 6 | 35 |

| 8 | 25 | Female | 16 | 2007 | 4 | 44 |

| 9 | 20 | Male | 11 | 2011 | 5 | 35 |

| 10 | 23 | Female | 17 | 2009 | 6 | 35 |

| 11 | 29 | Male | 6 | 2002 | 5 | 40 |

| 12 | 18 | Male | 15 | 2013 | 5 | 40 |

| 13 | 27 | Female | 15 | 2003 | 5 | 28 |

AQ: autism quotient.

We conducted interviews with school leavers rather than current pupils as we felt that some distance from the school experience would provide more reflective accounts. The upper age limit was chosen to ensure that participants were in mainstream secondary school at a point where mainstreaming of pupils with additional support needs was likely (Pirrie et al., 2006).

Participants (eight male/five female) had a mean age of 24.54 years (standard deviation (SD) = 4.19). The mean age of diagnosis was 10.54 years (SD = 4.54), and mean autism quotient (AQ) score was 36.69 (SD = 5.00). All participants identified as white British or Scottish. A number code was generated for each participant, and identifying details redacted from reported quotes.

Procedure

Participants provided written consent before taking part. All participants provided demographic information and completed an Autism Quotient measure through an online form prior to their interview. Interviews were conducted by the first author either in person (n = 2), over the phone (n = 7), over video call (n = 1) or via text chat (n = 3) depending on the preference of the participant.

Participants were told that they: could have a break any time throughout the interview for any reason; did not have to discuss anything they did not feel comfortable talking about and could provide as much detail as they wanted to for each question.

Measures

Interview

The research team developed a semi-structured interview schedule specifically for this study (see Supplementary Table 1). Prior to creating the schedule, we explored the literature for pre-existing schedules suitable for this area, though none were identified. Semi-structured interviews provide a flexible approach, allowing the interviewer to explore a participant’s response and to check the meaning of any ambiguous answers (Barriball & While, 1994).

Questions in the interview schedule broadly explored participants’ secondary school experiences, time spent with staff and other students during secondary school, reflections on support needs, and experiences of, and views on, autistic peer support. The wording of the interview was designed to be neutral (e.g. in terms of the potential benefits or challenges of peer support). The interview took 45–60 min to complete, and interview length was similar across the different formats (phone, video call, text chat, and in person). The interviews were conducted with awareness of the possibility of cross-neurotype miscommunication (Crompton, Ropar, et al., 2020; Hillary, 2020) in mind, and a number of steps were taken to minimise this: the question wording was reviewed by autistic people prior to the interviews, to ensure that it was clear and accessible; interviewees selected their preferred method of interview (in person, phone, video or text chat); interviewees were given time to process and check the meaning of questions, and the opportunity to clarify points they had made that the interviewer found unclear. The interview schedule is in the supplement.

The autism spectrum quotient (AQ)

The AQ is a 50-item, multiple-choice questionnaire, which yields an approximate measure of autistic traits (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). Scores range between 0 and 50, and an AQ score over 32 indicates high levels of autistic traits.

Community involvement

Lived experience perspectives were represented within the research team. An autistic research consultant and co-author were involved from the start of the project, advising on research methodology, recruitment and data collection, helping to ensure that our research is accessible to autistic people and in line with community priorities. Both autistic research team members were co-analysts of the qualitative data and are co-authors on this article. The research team was mindful of the potential difficulties in cross-neurotype communication within an autistic/non-autistic research team (Crompton, Ropar, et al., 2020; Hillary, 2020) and actively attempted to overcome communication barriers.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was applied to the data to identify patterns, commonalities, and differences in participant responses (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Thematic analysis was chosen as it can use an inductive process, thus not relying on existing frameworks to interpret data. This facilitates the creation of new knowledge and is well suited for an emerging and under-researched area (Willig, 2013), such as the topic of this research. A reflexive approach to thematic analysis was taken, with authors actively reflecting on their positionality during the analysis phases (Braun & Clarke, 2019). The research team was made up of autistic and non-autistic members from both academic and non-academic backgrounds, which ensured this research was influenced both by knowledge of the academic literature on this research topic and lived experience. Author identity may have influenced participant recruitment, data collection and analysis: our interests lie in progressive, participatory research using a neurodiversity paradigm, and this may have impacted who chose to participate in the research, as well the framing of our questions, rapport with participants and interpretation of the data. In addition, our knowledge of the existing literature may have shaped the analysis phase, though the analysis process was largely inductive rather than deductive (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Reflection on these influences formed part of the analysis and interpretation processes.

A broadly constructionist approach to analysis was taken. Interviews were transcribed professionally and checked for accuracy by the first author. The first author then read and re-read transcriptions to become familiar with the content, identifying features in the data and generating initial codes. Codes were established using a constant comparative method, moving between the different participant responses and the potential codes (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Miles et al., 2019). The second, third, and fourth authors then reviewed these codes individually, before they were then discussed as a group. Co-authors saw sample quotes associated with each code and provided feedback on each of the codes. A collaborative virtual whiteboard space was used while discussing the codes and themes, allowing authors to move the codes around in real space. The first four authors grouped related codes into themes and subthemes through an iterative and collaborative process, and ensured these related back to the initial codes. While member checking was not carried out, all authors were then involved in defining and naming themes and considering the findings in the context of the relevant research literature (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Results

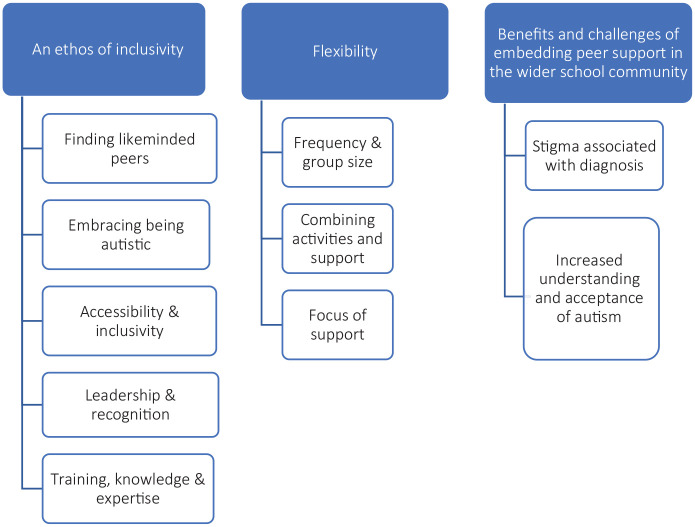

Participants each discussed their perspectives on autistic peer support within the context of their school experience more broadly. They reflected on their experience of diagnosis, support needs at that time, interactions with peers and teachers, and discussed the ways in which peer support may (or may not) be useful for autistic young people in mainstream secondary schools. Three main themes were identified from the interview data: (1) an ethos of inclusivity; (2) flexibility and (3) benefits and challenges of embedding peer support in the wider school community. Each theme comprised several subthemes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of themes and subthemes.

Theme 1: an ethos of inclusivity

Participants felt that autistic peer support had real potential for harbouring an ethos of inclusivity, and should be based on accepting and encouraging difference.

Subtheme 1: finding like-minded peers

While no participants mentioned experiencing formal autistic-specific peer support at school, participants all reported that they would have liked a space to share with like-minded people during their school years and felt that peer support space with other autistic pupils would have been beneficial: ‘Looking back I do think if that [autistic peer support] was available I would have liked that very much’ (Participant 6). ‘I think in the later years of high school when I started struggling with things, I think it would have been great to have that sort of peer support around’ (Participant 12). Participants reported that they felt particularly isolated after their diagnosis and that it would have been nice to spend time with others with similar experiences to them: ‘Sometimes it is nice . . . I always think it is nice to have really similar experiences that you can share and talk about . . . and sort of click on a particular level’ (Participant 8).

Most participants reported developing strong friendships with other autistic people after school and finding this very validating. They felt that they benefitted from spending time with other autistic people and reflected that they would have found this useful while at secondary school:

I went to a group for autistic people at my university, and it has been really helpful because I can talk about things, and most people understand and have similar experiences, and it has also allowed me to make friends. My current best friend is also autistic and I think it has . . . improved the understanding of myself and others, and allowed me to talk about things. I do think that [peer support at school] would have been beneficial. Because I don’t know if I would have made friends or not, but I would have made an attempt to, at the very least. And discussing some of the issues that I faced with people that understood and had similar experiences, that would have been good. (Participant 9)

Providing a space where autistic young people can be comfortable in who they are and talk about what makes them different in a positive way was highlighted as a beneficial component of peer support. Interacting with other autistic people may be particularly comfortable as autistic people may feel less need to mask and be more open about their experiences: ‘I can have conversations with them [autistic people] where I am really comfortable, and I am not having to think about facial expressions and body language and all this malarkey. It is just a lot less stressful. And then I feel I can be a lot more like me . . . and then I am quite astonished sometimes that people can be like “oh yes, I am totally like that too”’ (Participant 8).

Subtheme 2: embracing being autistic

Peer support potentially offers a unique opportunity to build pride in being autistic and develop a positive autistic identity. In particular, three of the older participants mentioned that when they were at school, being autistic was perceived very negatively and was not discussed. Participant 3 reported that at school ‘autism was the elephant in the room. . . .it would have been good for autism to be spoken about in a positive manner by other autistic students and teachers, and for there to be an open dialogue’. Most participants mentioned a degree of internalised stigma about their autism: ‘I do remember wasting quite a lot of energy at hating the facets of my personality which were most autistic as a child’ (Participant 6) and thought that supporting autistic young people to reduce internalised stigma could be beneficial: ‘I think a big thing we need to work on generally with autistic young people is removing that stigma. Cause it still follows me now even though I am really positive about being autistic’ (Participant 13).

Subtheme 3: accessibility and inclusivity

Accessibility and sensitivity to the needs of autistic young people is essential for successful peer support and requires thoughtful planning and consideration. Location and physical environment play an important role: participants reported that a calm space would provide some safety in the overwhelming school environment: ‘It would be nice to have somewhere to go and relax a bit . . . something where everyone can be calm and happy’ (Participant 12), ‘It would be nice to have a low sensory space to go to’ (Participant 3). The approach taken was also seen as contributing to accessibility. Participants noted the need for using clear language to aid understanding, having a consistent, reliable schedule and support for building and managing friendships for peer support to function well: ‘I am someone who likes to have a routine for things. I like to know when and where and what things are going to be. I have to plan things and if things aren’t planned I struggle’ (Participant 12).

A lack of acceptance of intersectional identities can be a barrier to effective, inclusive peer groups. LGBTQIA+ identities are more prevalent in the autistic community (Sala et al., 2020) and one participant noted that this had been a particular barrier for them engaging with their peers at school: ‘I didn’t relate to anyone because . . . I felt self-conscious . . . It is partly an intersection between trans stuff and autism’ (Participant 11). Peer support groups should also be aware of, and welcoming to, people of all backgrounds and identities.

Many participants suggested that peer support should be open to, and welcoming of, all neurodivergent pupils and pupils with mental health conditions, rather than autistic pupils exclusively. They felt that this would create a more inclusive environment and would allow them to discuss different things they found difficult and elicit a variety of coping strategies:

So I guess the real criteria for me would be more to do with their motivation, their ability to help, and their experience as well. It doesn’t have to just be people who are on the spectrum, it is not just autistic people who struggle. It could be people who are dyslexic, people who have had a bereavement or whatever and they have had similar reasons to be out of school and are in a similar negative situation. And I wouldn’t really mind if they were on the spectrum or neurodivergent in any other way. The priority for me would be that I feel they are on my side and have at least some sympathy, even if not understanding, of what I am going through. (Participant 4)

Finally, even though in general participants reported finding autism-specific communication easier, this was not always the case. It was highlighted by some participants that differences between autistic people may cause difficulty within a peer support setting:

. . . because autism is such a wide-ranging spectrum . . . with some autistic people, we have really different needs and we will have really different experiences. So for example . . . I sometimes am really sensitive to noise and there will be others who will stim by making a noise and that can be really irritating to me, even though I understand why they are doing that. So I think the conflicting support needs could be an issue definitely. I generally do feel quite positive about supporting each other . . . I have found such a good community with other autistic people and that has been beneficial and I think it would be really beneficial to younger people . . . and when I was younger as well, but it might not always be straightforward. (Participant 2)

This highlights the need for clear guidance on how to be a peer supporter and the boundaries of the group, as well as close coordination with staff, and advice on what other support pupils can engage with. These issues could potentially be bridged by well-trained staff supporting the group.

Subtheme 4: leadership and recognition

Participants felt it was important that autistic pupils engaging with peer support played a key role in its leadership and direction, rather than this being pre-defined by staff (or researchers), to ensure that it met their needs:

It is . . . much more useful when the people involved are able to contribute to how the group is run and how it is done . . . it is quite beneficial in order to get . . . our perspectives on things and be able to sort of take care of our needs and things like that. (Participant 9)

Participants felt that having an adult co-ordinator was important to support and moderate discussions, and in particular, that

an autistic adult would be best cause they would be easier to understand . . . They are more likely to have a better understanding of an autistic child’s experience. They are more able to empathise with other autistic people and a better understanding of each other. (Participant 12)

In addition, spending time with an autistic adult might be beneficial for autistic young people who may not have had this opportunity:

Having an autistic adult around would help . . . because I feel like having some sort of sense of where my life might go and the kind of person I might become, would have helped. When I was a child and a teenager I struggled a lot with suicidality, cause I couldn’t see what my future looked like at all. You didn’t see autistic adults. I think . . . a lot of what . . . made me suicidal was that I couldn’t visualise a world in which I was autistic as an adult. So I think having an autistic adult come in and be like ‘hey I am here, I can help you with stuff’ Would have been really useful. (Participant 11)

Being a peer supporter was also highlighted as being a responsibility, as well as something beneficial for autistic young people. It was suggested that peer supporters’ contributions should be recognised by the school as an activity involving responsibility and skill:

I think it is also good for the person doing the support as well. Being a supporter is seen to turn into a positive, the level of being a prefect or something like that. Where it is seen as ‘wow, you have responsibility, you have taken time out, you have got these skills and you have really helped someone’. It does need to be seen as a two-way thing cause I think it needs to be seen as a ‘you get something from it as well’. (Participant 4)

Subtheme 5: training, knowledge and expertise

The need for training to ensure that peer support was manageable and sustainable was highlighted by many participants. It was also suggested that there should be clarity about the different types of support within the school and the types of situations that young people (and/or adult co-ordinators) should not try to manage without external support:

Some brief level of training and then [. . .] a sort of handbook or something that is given out. It would maybe be ‘ok, here is how to listen, here is a lists of red flags that you shouldn’t try and handle yourself, you should go speak to a teacher about’ . . . and also ‘if it is a problem to do with academic things, then you go speak to this person . . . if it is a problem related to inclusion things, you go to speak to this person’. So like a roadmap, shall we say. (Participant 4)

It was noted that staff coordinators would also require some level of training to ensure that the group could function well as an inclusive, supportive network. This would include understanding the things that autistic young people often struggle with ( ‘communication and interaction, sensory processing and anxiety, navigating mechanisms within the school for support’ (Participant 7)), mediating difficult relationships between members of the group, and listening and engaging with autistic voices:

The person co-ordinating could help . . . if there is any problems within the group, if like someone is feeling isolated or there is some cheekiness or bullying, cause bullying can happen even amongst autistic people. A lot of groups within schools have a person to go to for social support or advice on how to handle social situations, that would be needed. (Participant 11)

Some participants noted that when they had been enrolled in school ‘buddy programmes’, paired with a non-autistic student, these factors had posed significant barriers for them: ‘It was just “there you go” effectively, and no guidance about what the point of it was. It didn’t go anywhere from the initial “Hi, how are you?” . . . more organisation would definitely have helped’. (Participant 1). This suggests that it would be beneficial that training covers both establishing and maintaining peer support relationships.

Theme 2: flexibility

While participants were generally very positive about the concept of autistic peer support within mainstream schools, there was a wide range of opinions on how best to manage and support this, as well as a diversity of views on what the function of autistic peer support should be. This reflects both the heterogeneity of autism and the range of different experiences that young people have. This suggests that autistic peer support needs to be flexible and reflective of the varied needs of the pupil cohort in a specific school at any given time. Some specific considerations and reflections are detailed below.

Subtheme 1: frequency and group size

Regarding frequency of contact, participants reported a need for flexibility, though generally felt that weekly informal sessions would have suited them best. Responses about peer group structure and size elicited a range of preferences. While some participants wanted 1:1 peer support: ‘because I am anxious in small groups, even groups of four, I would have wanted 1:1’ (Participant 1), others stated a preference for group peer support, or a hybrid between 1:1 and group: ‘I can be overwhelmed by group meetings, but they can be good if you know the other people’ (Participant 3). This highlights the need to work closely with pupils at the individual school-level at the group design stage.

Subtheme 2: combining activities and support

Most participants said that a peer support format which included combining support with activities would suit them, as it reduces the pressure of solely focusing on support and provides a more natural setting for friendship-building:

I think an activity . . . would be more helpful because it gives us . . . a basis to have in common, rather than just us being a group of people who are autistic. A group based around interests would make it less scary . . . and helps autistic people get to know each other, and know other people in a similar situation to them. It may be that having a space at some point in the group, at the beginning or end allows people to share experiences they’ve had and to talk about that too. (Participant 13)

Flexibility is needed regarding the type of activity that peer support groups are based around. Participants suggested a range of activities, and thus, single-activity, multi-activity or rotating-activity-based peer support could be considered and decided by pupils at the individual school level.

Subtheme 3: focus of support

Peer support provides a forum to discuss difficulties with people who may have similar experiences and to build a support network. Participants reported a range of areas that peer support could help with, and thus, schools should consult pupils and provide flexibility regarding the focus of peer support.

First, some participants reported wanting a peer space to talk and make friends. Most participants reported having difficulty making friends in secondary school: ‘I tended to keep mostly to myself. I guess because I didn’t really know how to approach people’ (Participant 7) and suggested that that a peer support space may have helped them make friendships: ‘I would’ve wanted a friend to chat to, to act as a sounding board. . .someone like-minded in a big place’ (Participant 3).

Second, some participants reported wanting time to discuss what they were finding difficult and share helpful strategies:

Peer support is a good thing because it’s reversing the trend where we privatise a lot of stress and anxiety . . . You can be reassured that if there is a problem, you can explore it and you don’t feel that you are dealing with it yourself . . . People on the spectrum struggle in different ways and overcome things in different ways, but being together can help . . . I spoke to people on the spectrum and I have given them advice and they have given me advice and some of their coping tactics work for me and some things I give them work too . . . A diversity of opinion would be quite useful for making school better. (Participant 4)

Third, some participants reported that peer support could be useful with many aspects of education, including navigating school life, organising their time, improving communication with teachers and supporting them during exam periods.

It would be good to have somebody to touch base with and if there was an issue there would be a way to raise that without necessarily having to walk up to a teacher in question and be like ‘I am not very happy with this class’ or something like that. Which is quite a confrontational thing. And obviously with social anxiety that can be quite a daunting experience. (Participant 5)

Specifically, participants felt that peer support from other autistic young people would be beneficial, to share advice about what might be helpful from an autistic perspective: ‘People tend to ignore the fact that autistic people can offer quite practical advice towards each other’ (Participant 11), and autistic people may have specific advice that can benefit their autistic peers’ education and speak about things that have helped them at school:

I do think the most important thing to me personally is to be able to discuss things with other people who are a similar sort of age and do similar sort of things. To see what they are doing and how they are dealing with certain things. (Participant 9)

As noted in the previous subtheme, combining these strands of support with activities might be beneficial for peer support groups.

Theme 3: benefits and challenges of embedding peer support in the wider school community

Although generally participants were very positive about peer support and suggested that it would have been beneficial during their school years, some potential barriers to engagement were identified, including stigma and autism understanding. These potential barriers could potentially be reduced by widening participation in peer support to neurodivergent students and pupils with mental health conditions to decrease the stigma associated with participation and increase autism acceptance. These barriers would have to be carefully managed and mitigated to ensure that peer support was safe and sustainable for pupils. It is also important to recognise that peer support is not right for every pupil at every time and should not be substituted for other forms of support, for example, intervention from teachers. However, as this theme suggests, peer support can have benefits both for autistic pupils and the wider school community.

Subtheme 1: stigma associated with diagnosis

Many participants noted the stigma associated with being autistic, and at school had not told their peers about their diagnosis. For some, this was due to negative feelings being autistic: ‘it was something I found quite embarrassing, and it is still something that I disassociate from’ (Participant 10); for others, it was because they did not know how others would react: ‘I have been treated in a range of ways once I have told people I am on the spectrum. . .it has gone from really patronising to “wow that must be interesting, tell me more”’ (Participant 4). A common difficulty was not knowing how to explain what being autistic meant:

I think the only reason I didn’t tell friends is because I just didn’t know how to. I didn’t really understand it . . . because no one had really explained it to me. You can’t just walk up to someone you have known for three years and go ‘oh by the way I am autistic’, and if they are like ‘oh what does that mean’ say ‘oh I don’t know’. It doesn’t really sound good at all, it is like you are just making it up. So I didn’t know how to say it. (Participant 8)

One pupil who did disclose their diagnosis found that it did not help their peers understand them:

they [my non-autistic peer group] did know [that I was autistic], but I don’t think they understood this. I was still expected to be like them, and communication breakdowns were blamed on me. There was no good information for them, or for me to share. I was just seen as a bit weird. (Participant 3)

There were also worries that disclosure would lead to exclusion or bullying: ‘I didn’t tell people I had a diagnosis because it would make me feel a bit different . . . or people would make fun of me’ (Participant 9).

One potential benefit of a group offering more broadly neurodivergent peer support rather than autism-specific peer support is that it affords pupils a level of anonymity regarding their specific diagnosis, which participants felt was important. It was also suggested that it is important to consider how the peer support group is promoted within the school community to ensure that those who are less comfortable disclosing or discussing their diagnosis still feel able to engage:

If they [autistic pupils] don’t feel comfortable outing themselves as autistic, it should be down to them whether they want to. I think in terms of still giving them access to support network and programmes and that, they should make it anonymous of who is going and not obvious that everyone who is going then has to be autistic cause they are going to that. (Participant 12)

Subtheme 2: increased understanding and acceptance of autism

Participants reported that autism understanding from non-autistic pupils was generally low and that autism held very negative connotations: ‘Nobody else really knew what being autistic was like, or what autism was really . . . being seen as different, in terms of neurodiversity, was always seen as something that was negative or would hold you back’ (Participant 4).

Making peer support accessible to a wider group of pupils (i.e. all neurodivergent pupils and/or those with mental health conditions) potentially affords the additional opportunity for young people to learn more about autism and neurodivergence more broadly: ‘it would increase awareness and it would maybe also diffuse some of the otherness’ (Participant 4):

I think what needs to be done is that people need to have a better understanding. There needs to be more education on what it is like for autistic people. Pupils who are not autistic that come can be better educated on these matters while they are there as well. (Participant 12)

This enhanced understanding of the neurodivergent experience within the group may reduce negative experiences with other pupils beyond the peer support group and increase mutual support and solidarity among neurodivergent pupils.

I imagine . . . if you have a neurodiverse peer support person who . . . maybe they don’t know much about autism but they are helping someone on the spectrum, they hear their friends making a joke about it and they might be like ‘no actually my experience has been completely different, my experience is positive and nothing like that at all, stop making fun of them’. (Participant 12)

Discussion

This study aimed to elicit the views of autistic school leavers on school-based autistic peer support. Previous research has focused on peer support which involves autistic pupils being supported by non-autistic peers. Here, we specifically explored how autistic young adults felt about the idea of autism-specific peer support, whereby autistic pupils support one another. The analysis resulted in three themes: an ethos of inclusivity, flexibility, and the benefits and challenges of embedding peer support in the wider school community. The results echo previous research on autistic communication, support and community for autistic adults, which have found that autism-specific social settings may be beneficial (Botha et al., 2020; Crane, Hearst, et al., 2021; Crompton, Ropar, et al. 2020; Crompton, Sharp, et al., 2020; Heasman & Gillespie, 2019); however, this is the first indication that this type of support might also be desirable and potentially beneficial to younger autistic people. Participants generally felt that autistic peer support in mainstream secondary schools would be wanted and beneficial, and provided insight into how this support should be set up and sustained, and key issues that may arise.

The importance of autistic-specific peer support and spaces

Importantly, no participants stated that they would have preferred peer support from neurotypical pupils. To date, research on peer support within schools has focused almost exclusively on neurotypical pupils mentoring or befriending autistic students (Bambara et al., 2016; Bottema-Beutel et al., 2016; Bradley, 2016; Brain & Mirenda, 2019; Carter et al., 2017; Gardner et al., 2014; Hochman et al., 2015; Kretzmann et al., 2015; Sreckovic et al., 2017) in order to support autistic pupils to develop neurotypical social skills and strategies to engage with their peers. The attitude that peer support can only be effectively delivered by neurotypical mentors permeates peer support research, including one study which stated that the success of peer-mediated interventions is contingent on access to neurotypical peers (Lorah et al., 2013). Our research suggests that there may be benefits to autistic peer support in school and that this should be investigated in future intervention studies. A recent study found that two-thirds of participants thought that being autistic negatively impacted their experience at school (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2020) and autistic people can internalise negative perceptions about their diagnosis (Berkovits et al., 2020). However, autistic young people can identify several positive attributes about themselves (Clark & Adams, 2020) and benefit from having a space to talk openly about their diagnosis (Crane, Lui, et al., 2021). There has also been the suggestion that autistic young people should be encouraged to explore autistic culture and be supported in constructing their identity (Cresswell & Cage, 2019). This aligns with our findings suggesting that an autism-specific peer support model may be valuable for autistic adolescents in mainstream secondary schools. Indeed, even if autistic young people do not feel comfortable or ready to join an autistic or neurodivergent peer support group, its very existence within the school may send a message of visibility, inclusion and acceptance.

Past research has found that spending time with autistic peers need not be a form of siloing or segregating autistic people, but instead can be a mechanism for maintaining well-being and for building resilience to manage everyday life in a majority non-autistic world (Crompton, Hallett, et al., 2020). While conflicting needs and communication difficulties between autistic people were highlighted as a potential concern both by participants in this study and in previous research (Bottema-Beutel, 2020; Carter et al., 2017), there is a clear desire for future exploration into autism-specific peer support within mainstream school settings.

Bottema-Beutel et al. (2016) found that autistic young people preferred support groups where adults were present and could initiate interactions between participants, though found their continued presence intrusive when adults controlled the topics of discussion. This is reflected in our findings that autistic young people felt that it was important to play a key role in the leadership and direction of a peer group rather than this being pre-defined by staff. In addition, participants stated that they would ideally like the group to be facilitated by an autistic staff member, echoing recent findings that autistic teachers would like to mentor autistic pupils and play a role in their educational inclusion (Wood & Happe, 2020), and previous research showing that some disabled student teachers feel that they are potentially well placed to support pupils with similar disabilities, through their unique understanding of the pupils’ learning experiences (Macleod & Cebula, 2009).

Broader neurodivergent peer support

Interestingly, participants were also interested in neurodivergent (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2021; Kapp et al., 2013) rather than autism-specific peer support, recognising that issues relevant to autistic people may also affect broadly neurodivergent people. Broader neurodivergent peer support may have several benefits. First, it means that a wider and more diverse group of pupils are involved, bringing together varied experiences, interests and strategies. Neurodiversity is an inherently inclusive movement, and involving all participants who identify as being neurodivergent may create an inclusive space and ethos. Second, it is common for pupils to have multiple neurodivergent identities: pupils with co-occurring diagnoses have significantly poorer educational outcomes than those with a single diagnosis and have increased social, emotional and communicative difficulties (Fleming et al., 2020). It has therefore been recommended that training and practice address and support the complexities of those with co-occurring conditions (Fleming et al., 2020). A space within the school that welcomes these pupils and encourages them to spend time with like-minded peers may be beneficial; previous research has found that autistic people have the most success in friendships where atypical behaviour is normalised and accepted (Sosnowy et al., 2019). Participants in our study also highlighted the need for acceptance of intersectional identities: it is important to acknowledge that neurodivergence is only one facet of identity and that diverse friendships offer multiple benefits for both individual and group relations (Bahns, 2019). Third, broad neurodivergent peer support means that individual pupils do not need to disclose their specific diagnosis if they are not comfortable doing this. However, due to the heterogeneous nature of neurodivergence, there may be conflicting support needs within a neurodivergent peer support space which may cause difficulty within a peer group. This may need to be carefully supported by staff to ensure that neurodivergent peer spaces are accessible and inclusive for all.

Practical implications and peer support design

Several participants highlighted the importance of a central activity to be accomplished or engaged in within any peer support group, rather than limiting the peer support to discussion-based formats. Having a mediating activity may help pupils initiate and sustain social connections and build communication and trust (Müller et al., 2008). While many autistic people describe feeling anxious or stressed in unstructured social situations, creative activities may help bridge interactions and reduce social anxiety (Müller et al., 2008). Previous research has found this beneficial; for example, one study examined the engagement of autistic adolescents in adventure therapy, an approach which was chosen due to the opportunity it presents for ‘uncontrived interaction, a group-driven process, and emphasis on the here-and-now’ (Karoff et al., 2017, p. 394). Peer support activities could take many forms – music, role playing games, improv, outdoor activities, yoga, creative writing: involving pupils from the earliest stages of planning a peer support group is therefore important in ensuring that activities match the interests of the group. Shared interests and activities are also another bridge to support the development of peer relationships, and potentially friendships. It is important when designing future peer support frameworks to consider the desired outcome of the autistic young people engaging in the support, whether this is friendship-building, developing coping skills and strategies, or building self-confidence, as these factors may influence the peer support design.

The importance of training and supervision mechanisms for pupil peer supporters and staff supporters was mentioned by participants, particularly in the context of the lack of clarity on the meaning and boundaries of peer support – a common issue highlighted in the literature (Hamilton et al., 2016). Designing and delivering appropriate training is key to the success of peer support groups, and future work could usefully involve co-designing training with autistic young people. Participants spoke of the need for peer support to be a place that embraces being autistic, and thus, the content of this training must reflect this. Martin et al.’s (2017) mentor training programme on key features of successful mentoring relationships was designed and delivered by autistic adults for autistic and non-autistic mentors working with autistic adults. Regular mentorship over 6 months resulted in improvements in the well-being of the mentees, as well as progress towards self-selected goals (Martin et al., 2017). It is essential that peer support in schools features similarly ongoing training and support from staff to be sustainable and beneficial for the young people involved.

Potential wider school benefits

Having an autistic peer support group might reduce neurotypical stigma towards autistic pupils, if the visibility and activities of the peer support group increase knowledge and acceptance among neurotypical pupils, or if the inclusive approach of the group results in increased positive contact between neurotypical and neurodivergent pupils. This aligns with recent research which found that neurotypical pupils in schools with autism centres were more accepting of autistic pupils compared to neurotypical pupils at schools without autism centres (Cook et al., 2020).

Strengths and limitations

This is the first research examining autistic people’s reflections on school based autistic peer support and is an important first step in ensuring that future peer support frameworks are aligned with the experiences and preferences of autistic people at their core. Our flexibility in using the interview method (online messaging, video call, face to face and phone options) potentially enhanced the diversity of the participant sample. No specific patterns emerged from data collected via these different modalities, however – with a small sample size in each (in person (n = 2), phone (n = 7) video call (n = 1) text chat (n = 3)) – it is difficult to be definitive about the potential impact of modality on data. All interviews lasted a similar time, and all provided rich data, though in general, text chat interviews resulted in shorter transcripts than interviews of other modalities. However, allowing participants to select their communication modality may have enabled fuller interviews because participants may have felt more comfortable or able to communicate than if only face-to-face interviews were offered. In-person interviews do not differ from phone and online interviews in terms of substantive coding approach (Johnson et al., 2021), and alternative interview modalities can allow participants to feel relaxed and able to disclose sensitive information (Novick, 2008). This may be particularly important for autistic people: enabling autistic people to select their chosen mode of communication (e.g. face to face, live chat, phone, or in person) may enhance communication engagement (Howard & Sedgewick, 2021). Creating an interview that could be used over multiple modalities and offering autistic people the choice of how they wanted to communicate ensures that the researcher is communicating with autistic people in their preferred way, which reduces anxiety (Howard & Sedgewick, 2021) and potentially makes for richer and more valid data. Transcripts from interviews of all communication modalities were treated equally, with all participants represented in the analysis.

However, the study has some limitations. First, the study included a UK-based, all White sample, who were all relatively highly educated with no learning disabilities. Therefore, findings may not transfer to the wider autistic population, including people with learning disabilities, non-speaking autistic people, autistic people who are undiagnosed in childhood or autistic people living in countries where social norms differ from the United Kingdom. Second, we interviewed autistic school leavers who had left school within the last 12 years, rather than pupils currently at school. While this passage of time may have allowed for important reflection in the context of experiences since leaving school, social change can happen rapidly, and it will be important to engage with current school students when designing any future frameworks to ensure that it reflects the current environment. Third, the study drew from a relatively small sample. While the concept of data saturation is not necessarily appropriate for research taking a reflexive thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2021), our sample allowed for the collection of rich data which addressed our research aim and is in line with similar studies in this research area (see Cresswell et al., 2019). However, future research in this area with larger or more diverse samples would allow for further consideration of the peer support preferences of subgroups of autistic pupils, for example, autistic girls. It may be useful for future work to explore experiences and views in these groups who may have specific support needs and preferences (Gray et al., 2021). Fourth, though a finding from this work is that autistic people may prefer a broader neurodivergent peer support, as the focus of this study was autistic pupils, we have not interviewed any otherwise neurodivergent pupils to ascertain their thoughts on engaging with this type of peer support. Future research should work with non-autistic neurodivergent young people to ascertain their feelings towards neurodivergent peer support.

Conclusion

The idea of autism-specific peer support in mainstream secondary schools was generally positively received by autistic young people and may provide a unique opportunity for them to interact in a natural, comfortable way, share useful strategies and build their identity. Nevertheless, careful design, training and ongoing support, alongside awareness of the rights, needs and preferences of the individual pupils involved are likely to be crucial in ensuring the success of any peer support programme.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-aut-10.1177_13623613221081189 for ‘Someone like-minded in a big place’: Autistic young adult’s attitudes towards autistic peer support in mainstream education by Catherine J Crompton, Sonny Hallett, Harriet Axbey, Christine McAuliffe and Katie Cebula in Autism

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Institute of Advanced Studies in the Humanities Postdoctoral Fellowship to the lead author, and University of Edinburgh College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine Public Engagement with Research Seed Fund Round One, Institutional Strategic Support Fund.

ORCID iD: Catherine J Crompton  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5280-1596

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5280-1596

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Accardo A. L., Jukder S. J., Woodruff J. (2019). Accommodations and support services preferred by college students with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 23(3), 574–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikins J. W., Bierman K. L., Parker J. G. (2005). Navigating the transition to junior high school: The influence of pre-transition friendship and self-system characteristics. Social Development, 14(1), 42–60. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Appel K. (2011). College mentoring programs. In Simpson C., Bakken J. (Eds.), Collaboration: A multidisciplinary approach to educating students with disabilities (1st ed., pp. 353–361). Prufrock Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bahns A. J. (2019). Preference, opportunity, and choice: A multilevel analysis of diverse friendship formation. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22(2), 233–252. [Google Scholar]

- Bambara L. M., Cole C. L., Kunsch C., Tsai S. C., Ayad E. (2016). A peer-mediated intervention to improve the conversational skills of high school students with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 27, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bargiela S., Steward R., Mandy W. (2016). The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S., Wheelwright S., Skinner R., Martin J., Clubley E. (2001). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriball K. L., While A. (1994). Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing-Institutional Subscription, 19(2), 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkovits L. D., Moody C. T., Blacher J. (2020). ‘I don’t feel different. But then again, I wouldn’t know what it feels like to be normal’: Perspectives of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(3), 831–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardin C. J., Mason E., Lewis T., Kanne S. (2021). ‘You must become a chameleon to survive’: Adolescent experiences of camouflaging. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(12), 4422–4435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs H., Reid S., Attygalle K., Wishart R., Sheilds J. (2020). MCR pathways social bridging finance initiative for educational outcomes evaluation report. The Robertson Trust. https://mcrpathways.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/MCR-Pathways-Evaluation-Report-Jan-2020-Publication.pdf

- Botha M., Dibb B., Frost D. M. (2020). ‘Autism is me’: An investigation of how autistic individuals make sense of autism and stigma. Disability & Society, 1–27. 10.1080/09687599.2020.1822782 [DOI]

- Bottema-Beutel K., Cuda J., Kim S. Y., Crowley S., Scanlon D. (2020). High school experiences and support recommendations of autistic youth. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(9), 3397–3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottema-Beutel K. (2020). Understanding and addressing social communication difficulties in children with autism. In Vivanti G., Bottema-Beutel K., Turner-Brown L. (Eds.), Clinical guide to early interventions for children with autism (pp. 41–59). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bottema-Beutel K., Mullins T. S., Harvey M. N., Gustafson J. R., Carter E. W. (2016). Avoiding the ‘brick wall of awkward’: Perspectives of youth with autism spectrum disorder on social-focused intervention practices. Autism, 20(2), 196–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottema-Beutel K., Park H., Kim S. Y. (2018). Commentary on social skills training curricula for individuals with ASD: Social interaction, authenticity, and stigma. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(3), 953–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley R. (2016). ‘Why single me out?’ Peer mentoring, autism and inclusion in mainstream secondary schools. British Journal of Special Education, 43(3), 272–288. [Google Scholar]

- Brain T., Mirenda P. (2019). Effectiveness of a low-intensity peer-mediated intervention for middle school students with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 62, 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. (1990). Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development, 61(4), 1101–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cage E., Di Monaco J., Newell V. (2018). Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(2), 473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cage E., Troxell-Whitman Z. (2019). Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 1899–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter E. W., Common E. A., Sreckovic M. A., Huber H. B., Bottema-Beutel K., Gustafson J. R., . . .Hume K. (2014). Promoting social competence and peer relationships for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial and Special Education, 35(2), 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Carter E. W., Gustafson J. R., Sreckovic M. A., Dykstra Steinbrenner J. R., Pierce N. P., Bord A., . . .Mullins T. (2017). Efficacy of peer support interventions in general education classrooms for high school students with autism spectrum disorder. Remedial and Special Education, 38(4), 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy S., Bradley L., Shaw R., Baron-Cohen S. (2018). Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Molecular Autism, 9(1), Article 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M., Adams D. (2020). The self-identified positive attributes and favourite activities of children on the autism spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 72, Article 101512. [Google Scholar]

- Cook A., Ogden J., Winstone N. (2020). The effect of school exposure and personal contact on attitudes towards bullying and autism in schools: A cohort study with a control group. Autism, 24(8), 2178–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L., Hearst C., Ashworth M., Davies J., Hill E. L. (2021). Supporting newly identified or diagnosed autistic adults: An initial evaluation of an autistic-led programme. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(3), 892–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane L., Lui L. M., Davies J., Pellicano E. (2021). Autistic parents’ views and experiences of talking about autism with their autistic children. Autism, 25(4), 1161–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell L., Cage E. (2019). ‘Who am I?’: An exploratory study of the relationships between identity, acculturation and mental health in autistic adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(7), 2901–2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell L., Hinch R., Cage E. (2019). The experiences of peer relationships amongst autistic adolescents: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 61, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton C. J., Hallett S., Ropar D., Flynn E., Fletcher-Watson S. (2020). ‘I never realised everybody felt as happy as I do when I am around autistic people’: A thematic analysis of autistic adults’ relationships with autistic and neurotypical friends and family. Autism, 24(6), 1438–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton C. J., Ropar D., Evans-Williams C. V., Flynn E., Fletcher-Watson S. (2020). Autistic peer-to-peer information transfer is highly effective. Autism, 24(7), 1704–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton C. J., Sharp M., Axbey H., Fletcher-Watson S., Flynn E. G., Ropar D. (2020). Neurotype-matching, but not being autistic, influences self and observer ratings of interpersonal rapport. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugan E., Kamps D., Leonard B., Watkins N., Rheinberger A., Stackhaus J. (1995). Effects of cooperative learning groups during social studies for pupils with autism and fourth-grade peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 28, 175–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetner T., Elafros A., Bortolin S., Drechsler C. (2012). Safe spaces: Gay-straight alliances in high schools. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie, 49(2), 188–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink E., Deighton J., Humphrey N., Wolpert M. (2015). Assessing the bullying and victimisation experiences of children with special educational needs in mainstream schools: Development and validation of the Bullying Behaviour and Experience Scale. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming M., Salim E. E., Mackay D. F., Henderson A., Kinnear D., Clark D., . . .Pell J. P. (2020). Neurodevelopmental multimorbidity and educational outcomes of Scottish schoolchildren: A population-based record linkage cohort study. PLOS Medicine, 17(10), Article e1003290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher-Watson S., Brook K., Hallett S., Murray F., Crompton C. J. (2021). Inclusive Practices for Neurodevelopmental Research. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 8, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher-Watson S., Crompton C. J. (2019). Autistic people may lack social motivation, without being any less human. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 42, Article E88. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner K. F., Carter E. W., Gustafson J. R., Hochman J. M., Harvey M. N., Mullins T. S., Fan H. (2014). Effects of peer networks on the social interactions of high school students with autism spectrum disorders. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 39(2), 100–118. [Google Scholar]

- Gates J. A., Kang E., Lerner M. D. (2017). Efficacy of group social skills interventions for youth with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 52, 164–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G., Strauss A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Gray L., Bownas E., Hicks L., Hutcheson-Galbraith E., Harrison S. (2021). Towards a better understanding of girls on the Autism spectrum: Educational support and parental perspectives. Educational Psychology in Practice, 37, 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P., Lee C., Waugh J., Beyer C. (2004). Describing roles that gay-straight alliances play in schools: From individual support to school change. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education, 1(3), 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton J., Stevens G., Girdler S. (2016). Becoming a mentor: The impact of training and the experience of mentoring university students on the autism spectrum. PLOS ONE, 11(4), Article e0153204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M. R. (2012). After school care for children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(3), 466–473. [Google Scholar]

- Heasman B., Gillespie A. (2019). Neurodivergent intersubjectivity: Distinctive features of how autistic people create shared understanding. Autism, 23(4), 910–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebron J. S. (2018). School connectedness and the primary to secondary school transition for young people with autism spectrum conditions. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 396–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillary A. (2020). Neurodiversity and cross-cultural communication. In Rosqvist H. B., Chown N., Stenning A. (Eds.), Neurodiversity studies: A new critical paradigm (pp. 91–107). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier A., Goldstein J., Tornatore L., Byrne E., Johnson H. (2019). Outcomes of a peer mentoring program for university students with disabilities. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 27(5), 487–508. [Google Scholar]

- Hochman J. M., Carter E. W., Bottema-Beutel K., Harvey M. N., Gustafson J. R. (2015). Efficacy of peer networks to increase social connections among high school students with and without autism spectrum disorder. Exceptional Children, 82(1), 96–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge N., Rice E., Reidy L. (2019). ‘They’re told all the time they’re different’: How educators understand development of sense of self for autistic pupils. Disability & Society, 34(9–10), 1353–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway-Friesen H. (2021). The role of mentoring on Hispanic graduate students’ sense of belonging and academic self-efficacy. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 20(1), 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Houlston C., Smith P. K., Jessel J. (2009). Investigating the extent and use of peer support initiatives in English schools. Educational Psychology, 29(3), 325–344. [Google Scholar]

- Howard P. L., Sedgewick F. (2021). ‘Anything but the phone!’: Communication mode preferences in the autism community. Autism, 25(8), 2265–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B. (2007). Peer functioning in children with ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(6), 655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull L., Petrides K. V., Allison C., Smith P., Baron-Cohen S., Lai M. C., Mandy W. (2017). ‘Putting on my best normal’: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2519–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N., Lewis S. (2008). ‘Make me normal’: The views and experiences of pupils on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools. Autism, 12(1), 23–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi M. (1991). Mentoring and undergraduate academic success: A literature review. Review of Educational Research, 61(4), 505–532. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. R., Scheitle C. P., Ecklund E. H. (2021). Beyond the in-person interview? How interview quality varies across in-person, telephone, and Skype interviews. Social Science Computer Review, 39(6), 1142–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Kamps D. M., Barbetta P. M., Leonard B. R., Delquadri J. (1994). Classwide peer tutoring: An integration strategy to improve reading skills and promote peer interactions among pupils with autism and general education peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamps D. M., Leonard B., Potucek J., Garrison-Harrell L. (1995). Cooperative learning groups in reading: An integration strategy for pupils with autism and general classroom peers. Behavioral Disorders, 21, 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kapp S. K., Gillespie-Lynch K., Sherman L. E., Hutman T. (2013). Deficit, difference, or both? Autism and neurodiversity. Developmental Psychology, 49(1), 59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]