Abstract

The plant hormones cytokinin (CK) and abscisic acid (ABA) play critical and often opposite roles during plant growth, development, and responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. Rose (Rosa sp.) is an economically important ornamental crop sold as cut flowers. Rose petals are extremely susceptible to gray mold disease caused by the necrotrophic fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea. The infection of rose petals by B. cinerea leads to tissue collapse and rot, causing severe economic losses. In this study, we showed that CK and ABA play opposite roles in the susceptibility of rose to B. cinerea. Treatment with CK enhanced the disease protection of rose petals to B. cinerea, while ABA promoted disease progression. We further demonstrated that rose flowers activate CK-mediated disease protection via a B. cinerea-induced rose transcriptional repressor, Rosa hybrida (Rh)WRKY13, which is an ortholog of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), AtWRKY40. RhWRKY13 binds to promoter regions of the CK degradation gene CKX3 (RhCKX3) and the ABA-response gene ABA insensitive4 (RhABI4), leading to simultaneous inhibition of their expression in rose petals. The increased CK content and reduced ABA responses result in enhanced protection from B. cinerea. Collectively, these data reveal opposite roles for CK and ABA in the susceptibility of rose petals against B. cinerea infection, which is mediated by B. cinerea-induced RhWRKY13 expression.

A pathogen-induced rose transcription factor can regulate disease protection by simultaneously inhibiting cytokinin degradation and downregulating abscisic acid responses in rose petal.

Introduction

Recognition of pathogenic microorganisms by host immune receptors leads to activation of defense signaling in the plant, and hormones play a critical role in this process (Berens et al., 2017). Salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) are the major plant hormones related to pathogen response, and an antagonistic relationship between SA and JA forms the central backbone of the plant immune signaling network (Thomma et al., 2001). The cross talk of SA, JA, and other plant hormones involved in plant–pathogen interactions, such as ethylene (ET), gibberellins (GAs), brassinosteroids (BRs), auxin, and strigolactones, form a signaling network that modulates the plant immune response (Pieterse et al., 2012). Functional overlap and redundancy, combined with the antagonism of different hormones makes this hormone signaling network extremely complex (Abuqamar et al., 2017).

Abscisic acid (ABA) and cytokinin (CK) have been implicated in plant–microbe interactions. ABA often has negative effects on the plant’s response to necrotrophic pathogens such as the fungus Botrytis cinerea. For example, exogenous application of ABA promoted infection of B. cinerea in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), while the ABA-deficient tomato sitiens mutant showed enhanced resistance to B. cinerea (Audenaert et al., 2002; Achuo et al., 2006). Similarly, the Arabidopsis ABA biosynthesis mutants abscisic aldehyde oxidase3-2 (aao3-2) and aba deficient2-12 (aba2-12) showed increased resistance to B. cinerea (Asselbergh et al., 2008). In addition, some regulators in the ABA signaling pathway also play roles in B. cinerea resistance. In Arabidopsis, ABA insensitive4 (ABI4), encoding an Apetala2 (AP2)-type transcription factor, acts as a key regulator in the transduction of the ABA-activated signaling pathway. The ABA-insensitive abi4-1 mutant of Arabidopsis showed enhanced resistance to B. cinerea, suggesting a negative role of ABA in resistance to necrotrophic pathogens (Asselbergh et al., 2008). Moreover, Liu et al. (2015) showed that negative regulation of the ABA signaling pathway by the Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY33 is critical for resistance to B. cinerea (Liu et al., 2015).

In contrast to ABA, CK generally promotes disease protection against necrotrophic pathogens, although there are exceptions. In plants, adenosine phosphate-isopentenyltransferase (IPT) catalyzes CK biosynthesis, and CKX enzymes catalyze CK degradation (Zürcher and Müller, 2016). CK homeostasis, including its synthesis by IPT and degradation by CKX, is essential in the plant response against pathogens. For example, increased CK levels in IPT-overexpressing transgenic tomato plants resulted in a reduced susceptibility against infection by B. cinerea (Swartzberg et al., 2008). Arabidopsis plants overexpressing IPT manifested reduced susceptibility to the necrotrophic fungal pathogen Alternaria brassicicola, whereas constitutive expression of the CK degradation gene CKX4 increased susceptibility to A. brassicicola (Choi et al., 2010).

In various biological processes of plants, antagonism between the ABA and CK pathways is involved. Both hormones influence each other’s production and response. Exogenous ABA application suppresses the expression of IPT8 in Arabidopsis (Nishiyama et al., 2011), and ABA promotes the expression of a number of CKX genes to reduce the level of CK in Arabidopsis (Werner et al., 2006). Recent studies revealed that CK-induced Type-A Arabidopsis response regulators (ARRs) inhibit the ABA response by interacting with and promoting the degradation of ABI5, a key transcription factor of the ABA signaling pathway, in Arabidopsis seedlings (Wang et al., 2011; Guan et al., 2014). Interestingly, ABA-induced ABI4 negatively regulates the transcription of several Type-A ARRs by directly binding to their promoters (Huang et al., 2017). Thus, ABI4 and ABI5 are considered as key signaling nodes in the regulation of the cross talk of CK and ABA signaling. However, detailed studies of the regulatory mechanism underlying the interaction between CK and ABA are still limited.

Roses (Rosa sp.) are an economically important ornamental crop worldwide, accounting for over 30% of the world’s cut-flower trade and valued in the billions of US dollars in the annual global market. Globally, cut roses are mainly produced in tropical plateau areas in Africa and South America, such as Kenya, Ethiopia, Ecuador, and Colombia, whereas the major consumer market is developed countries in Europe and North America. During the long-distance transport to the consumer market, which can take 3–4 days, cut roses are subjected to various abiotic and biotic stresses. For example, gray mold disease caused by the necrotrophic fungal pathogen B. cinerea is a major threat and causes severe losses of this important ornamental crop (Cao et al., 2019).

Synthetic CK (6-benzyladenine, 6-BA) is commonly used in flower preservatives to increase the vase life of cut flowers. Here, we found that the presence of CK in flower preservatives, either 6-BA or naturally occurring CK, has a positive effect on the protection of rose flowers against B. cinerea. By contrast, exogenous application of ABA has the opposite effect and promoted necrotrophic infection of B. cinerea on rose petals. We identified a B. cinerea-induced WRKY transcription factor, RhWRKY13, that promotes protection of rose by inhibiting the expression of the CK degradation gene RhCKX3 and the ABA response gene RhABI4, simultaneously. This work revealed the molecular mechanism of RhWRKY13-mediated disease protection against B. cinerea in rose flowers by its opposite effects on CK and ABA signaling.

Results

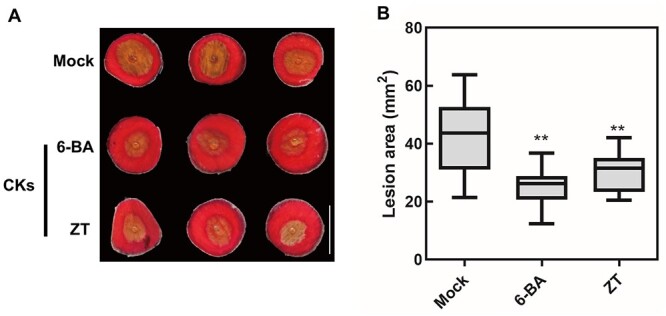

CKs protect rose against the necrotrophic fungal pathogen B. cinerea

The synthetic CK 6-BA is frequently used in flower preservatives to slow the degradation of cut flowers. We noticed that the application of 100 µM 6-BA in flower preservatives enhanced disease protection against B. cinerea infection of cut rose flowers (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figure S1). Similarly, direct atomizer spraying of 6-BA on rose petals resulted in a significant reduction of B. cinerea infection (Elad, 1993). Nevertheless, the role of naturally occurring CK in disease protection against B. cinerea is still unknown. To investigate the role of CK in rose petal disease protection mechanisms, we treated petal discs from rose flowers with the naturally occurring CK zeatin (ZT) and then inoculated them with B. cinerea (Figure 1). Similar to 6-BA-treated flowers, the 100 µM ZT-treated flowers showed significantly smaller lesions that formed at the inoculation sites at 60 h post inoculation (hpi) (Figure 1), suggesting that naturally occurring CKs might play an important role in the disease protection to B. cinerea in rose petals. The same results were obtained using whole flowers (Supplemental Figure S2). Moreover, ZT itself and low concentrations (1 and 10 µM) of 6-BA had no inhibitory effect on the growth of B. cinerea in a plate assay, but 100 mM 6-BA seemed to inhibit B. cinerea growth (Supplemental Figure S3). All the results indicated that exogenous CK could decrease rose petal susceptibility to B. cinerea.

Figure 1.

Treatment with exogenous CKs promotes disease protection against the necrotrophic pathogen B. cinerea. A, Mock-, 100 µM 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BA)-, and 100 µM ZT-treated discs of rose petals inoculated with B. cinerea. The images were digitally extracted and scaled for comparison (scale bar = 1 cm). B, Statistical analysis of 60 hpi lesion area in petals subjected to exogenous CKs or water. The box contains the middle 50% of the data. The upper edge (hinge) of the box indicates the 75th percentile of the data set while the lower hinge indicates the 25th percentile. The lines in the boxes indicate the median value of the data. It shows the lesion size from three biological replicates (n ≥ 48). The error bar represents standard deviation (SD). Significant differences are indicated by asterisks according to Student’s t test (**P < 0.01).

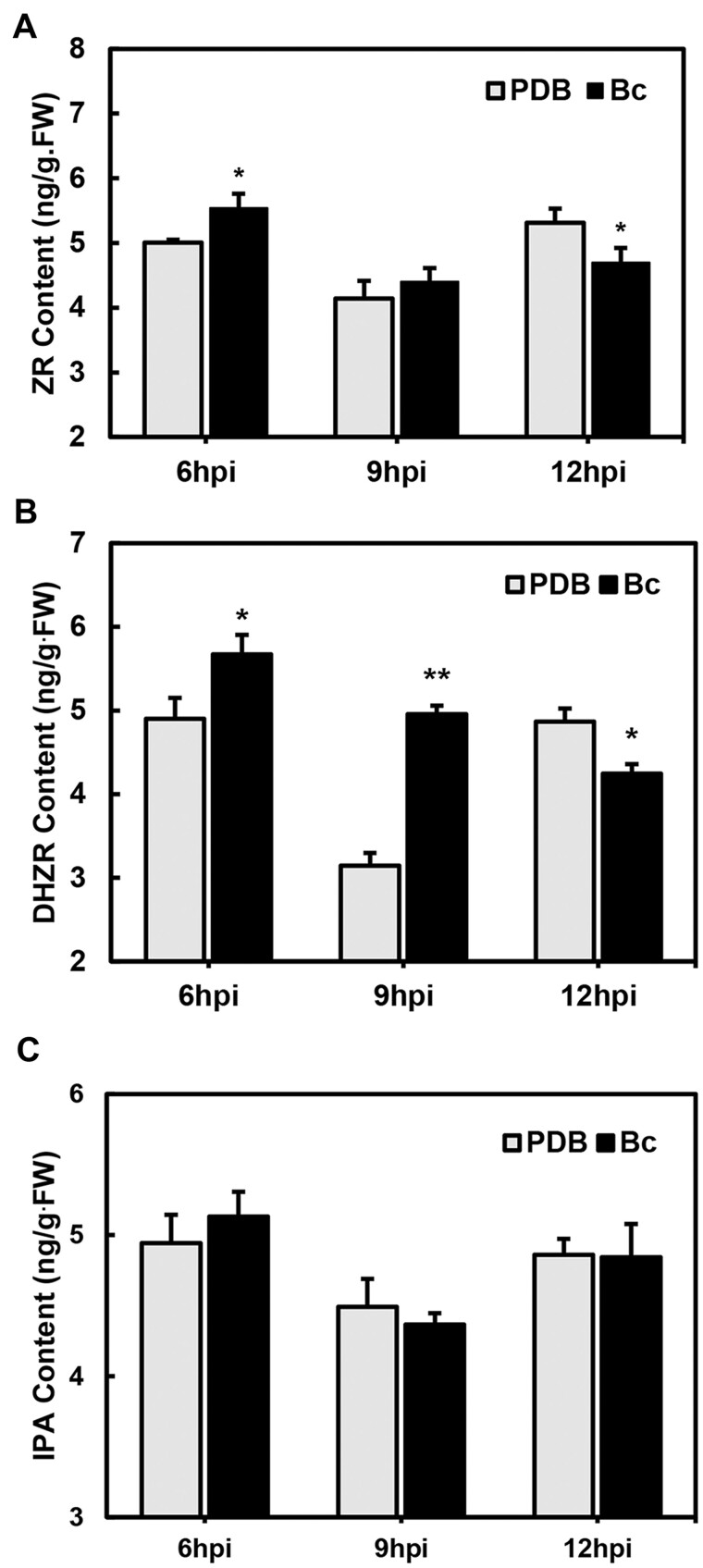

According to our work, the spores of B. cinerea started to germinate about 5 hpi, and by 12 hpi obvious killed petal cells could be observed (X. Liu and Z. Zhang, unpublished data). Dihydrozeatin riboside (DHZR), ZT riboside (ZR), and isoprenoid adenosine (IPA) are the most common CKs with physiological activity in plants (Mok et al., 2000). To further explore the role of CK in the rose–B. cinerea interaction, we quantified the three species of CK in rose petals at a time-course of B. cinerea inoculation, potato dextrose broth (PDB) treated petals were used as mocks. Results showed the CK content of rose petals increased subtly but to significant levels at the early stage of infection (6 hpi) (Figure 2), suggesting that the endogenous CK functions in disease protection. At the late stage of infection (12 hpi), a decreased CK content was observed (Figure 2). These results indicated that CK as an important phytohormone in the initial stage of rose–B. cinerea interaction, responded quickly to B. cinerea infection.

Figure 2.

The contents of CKs in rose petals after B. cinerea inoculation. The content of (A) ZR, (B) DHZR, and (C) IPA 6, 9, and 12 h after B. cinerea inoculation. Bc, B. cinerea. The contents of CKs are shown with mean ± sd from three biological replicates. The statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

RhCKX3 is a negative regulator of CK-induced disease protection against B. cinerea

As CK promoted the disease protection of rose flowers to B. cinerea, we investigated whether the rose plant activates or suppresses the expression of its CK metabolism-related genes as part of its protection response to B. cinerea infection. Although there are exceptions, plants mainly synthesize CK in the roots. Since our study is focused on the petals of the cut rose flower without roots, we focused our study on CK degradation-related genes rather than CK biosynthesis genes. We hypothesized that CK degradation-related genes could be downregulated upon B. cinerea infection, thereby maintaining CK contents and enhancing B. cinerea tolerance in petals.

CK degradation is mediated by CKXs in the plant. We identified a total of six RhCKX genes in the rose genome and named them based on their sequence similarity with the CKX genes of Arabidopsis (Raymond et al., 2018; Supplemental Figure S4). Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) revealed that among the six RhCKX genes, only RhCKX3 was downregulated during infection by B. cinerea (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure S5).

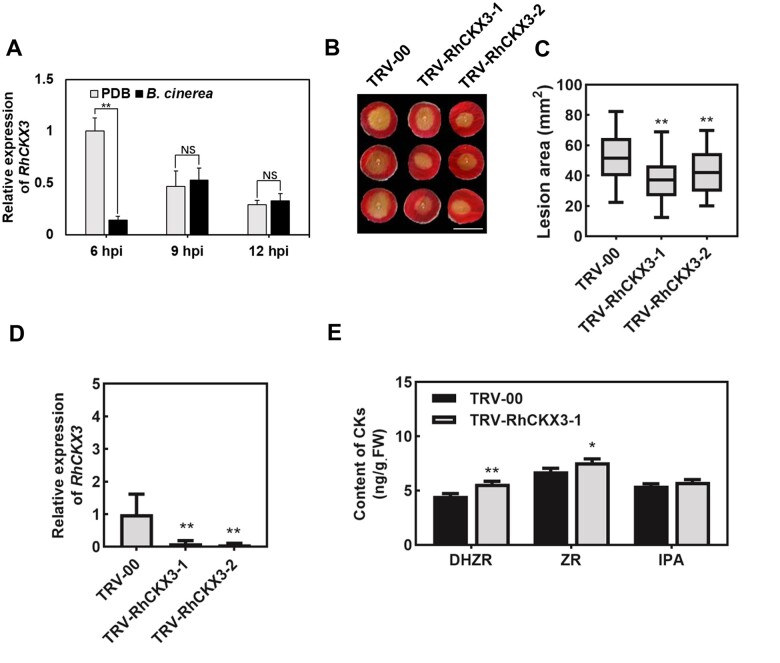

Figure 3.

CKX3 negatively regulates disease protection against B. cinerea in rose petals. A, RT-qPCR analysis of RhCKX3 expression at 6, 9, and 12 h in PDB-treated and B. cinerea inoculated rose petals. Mean ± sd are shown from three technical replicates. Experiments were performed independently three times, with similar results. B, Compromised disease protection to B. cinerea upon silencing of RhCKX3 at 60 hpi. Two independent coding sequence fragments of 188 bp (RhCKX3-1) and 246 bp (RhCKX3-2) of RhCKX3 were used for silencing. The images were digitally extracted and scaled for comparison (scale bar = 1 cm). C, Quantification of B. cinerea disease lesions on TRV-RhCKX3-1-, TRV-RhCKX3-2-, and TRV-00-inoculated rose petal discs. The box contains the middle 50% of the data. The upper edge (hinge) of the box indicates the 75th percentile of the data set while the lower hinge indicates the 25th percentile. The lines in the boxes indicate the median value of the data. It shows the lesion size from three biological replicates (n ≥ 48). The error bar represents SD. D, Relative expression of RhCKX3 at 6 days post-silencing compared with TRV-00. Mean ± sd are shown from three technical replicates. Experiments were performed independently three times, with similar results. E, CK contents in petals of RhCKX3-1-silenced and TRV-00 control. The contents of CKs are shown with mean ± sd from three biological replicates. All statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

To verify the role of RhCKX3 in response to B. cinerea, we used virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) in rose petals, as described previously (Cao et al., 2019), to silence RhCKX3. To this end, we independently inoculated petal discs with two different recombinant tobacco rattle virus (TRV)-based vectors that specifically target RhCKX3 (TRV-RhCKX3-1 and TRV-RhCKX3-2). The empty TRV vector was used as a control (TRV-00) and the silencing efficiency of VIGS was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Figure 3D). The RhCKX3-silenced petal discs, as well as the controls, were then inoculated with B. cinerea. At 60 hpi, the silencing of RhCKX3 resulted in a significantly smaller lesion area compared with the control petal discs, indicating enhanced disease protection against B. cinerea (Figure 3, B and C). Significantly increased contents of ZR and DHZR were detected in RhCKX3-silenced rose petals (Figure 3E). The above results indicate that RhCKX3 participates in the disease protection of rose against B. cinerea by regulating the endogenous CK content in plants.

RhWRKY13 directly binds to the RhCKX3 promoter and suppresses its expression in flower petals

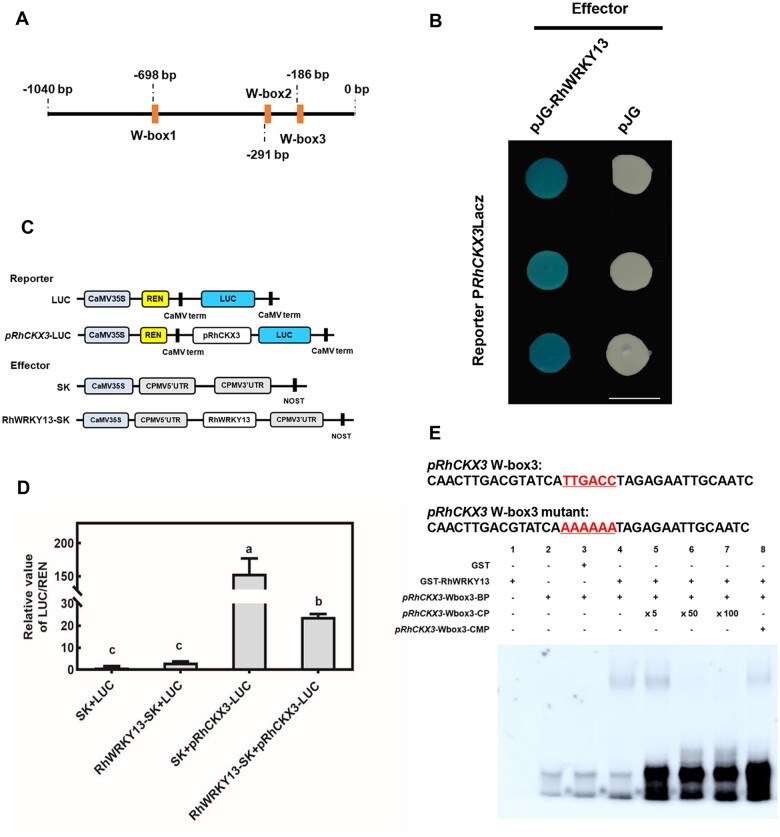

To understand the mechanism regulating RhCKX3 during the disease protection to B. cinerea, we cloned the 1,040-bp promoter region upstream of the RhCKX3 coding sequence. Sequence analysis using the New PLACE database (https://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/?action=newplace) suggested that the cis-elements in the promoter of RhCKX3 included 13 ARR1AT sequences for CK response regulators, 5 binding sites for MYB transcription factors, and 5 binding sites for AP2/ET response factor transcription factors. In addition, a known binding site for WRKY transcription factor, W-box ((T)TTGACY, where Y is C or T), was found on −186, −291, and −698 bp in RhCKX3 promoter region (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

RhWRKY13 binds to a cis-element in the promoter of RhCKX3. A, Schematic representation of the 1,040-bp RhCKX3 promoter (pRhCKX3). B, RhWRKY13 binds to the promoter of RhCKX3 in the Y1H assay. The empty effector vector pJG4-5 (pJG) was used as a negative control; RhWRKY13 binds to the promoter of RhCKX3 and promotes the expression of the downstream LacZ gene, which encodes β-galactosidase, which turns blue with 80 mg/L X-gal. The images were digitally extracted and scaled for comparison (scale bar = 1 cm). C, Double-reporter and effector plasmids used in the dual-luciferase reporter assay. D, The relative value of REN/LUC shows the interaction of RhWRKY13 and the RhCKX3 promoter for the LUC reporter system. Mean ± sd are shown from three biological replicates. Significant differences are indicated by lowercase letters according to Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05). E, The interaction of RhWRKY13 and biotin-labeled pRhCKX3 W-box3 as shown by an EMSA. Purified protein (1 μg) was incubated with 50 nM of the biotin-labeled wild-type pRhCKX3 W-box3 probes (BP) and non-labeled mutant pRhCKX3 W-box3 probes (CMP). The competition test was performed with non-labeled probes (CP) provided in 5-, 50-, or 100-fold excess over labeled probe.

The cloned promoter region was subsequently used as a bait to screen a library of B. cinerea-induced rose transcription factors using yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assays. The Y1H assay identified a WRKY transcription factor, RhWRKY13 (Liu et al., 2019), which could bind to the cis-acting element of the RhCKX3 promoter (Figure 4B).

To further analyze the interaction of RhWRKY13 and the RhCKX3 promoter, a dual-luciferase reporter assay was performed as previously described (Hellens et al., 2005). Co-expression of the RhWRKY13 effector (RhWRKY13-SK) with the RhCKX3 promoter-derived luciferase reporter [pRhCKX3-luciferase (LUC)] in Nicotiana benthamiana resulted in significantly higher luciferase activities than the control (SK + LUC) or RhWRKY13 alone (RhWRKY13-SK + LUC); but lower than that in cells with pRhCKX3-LUC only (SK + pRhCKX3-LUC) (Figure 4, C and D). These results indicated that RhWRKY13 could bind to the promoter of RhCKX3 and repress its transcription. Meanwhile, the transactivation assay in yeast also indicated that RhWRKY13 does not act as a transcriptional activator (Supplemental Figure S6). The electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was conducted to further clarify the interaction of RhWAKY13 and the RhCKX3 promoter W-box3 site (Figure 4E), not W-box1 or W-box2 of RhCKX3 promoter (Supplemental Figure S7). Moreover, binding was gradually attenuated by increasing concentrations of unlabeled probe and no binding occurred in the W-box3 mutation (Figure 4E).

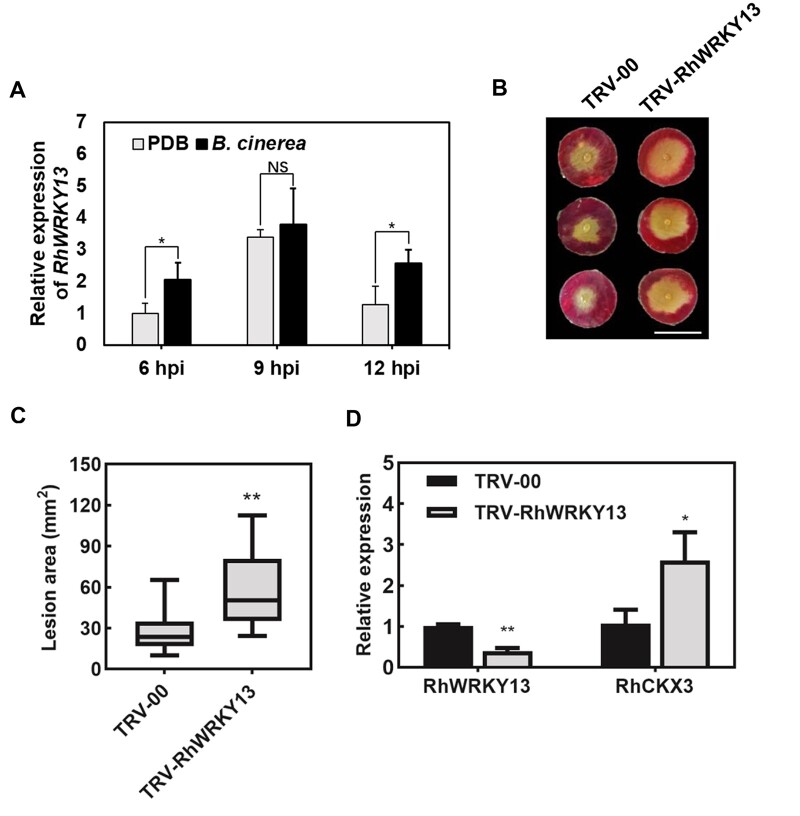

Silencing of RhWRKY13 promotes flower susceptibility to B. cinerea

We evaluated the expression pattern of RhWRKY13 during B. cinerea infection by RT-qPCR. The expression of RhWRKY13 was upregulated upon infection by B. cinerea (Figure 5A), opposite to the expression pattern of RhCKX3 (Figure 3A). To further verify the role of RhWRKY13 in the disease protection against B. cinerea in rose, we silenced RhWRKY13 in rose petals via VIGS. The RhWRKY13-silenced rose petals were more susceptible to B. cinerea compared with the TRV control (Figure 5, B and C). The RT-qPCR revealed that the expression level of RhWRKY13 in silenced petals was 60.5% lower than that in the TRV control; in contrast, the expression of RhCKX3 was 2.6-folds in the RhWRKY13-silenced rose petals (Figure 5D). The above results indicate that the B. cinerea-induced transcription factor RhWRKY13 regulates disease protection against B. cinerea in rose by inhibiting the expression of RhCKX3.

Figure 5.

RhWRKY13 is required for disease protection against B. cinerea in rose petals. A, Relative expression of RhWRKY13 at 6, 9, and 12 h in PDB-treated and B. cinerea inoculated rose petals. Mean ± sd are shown from three technical replicates. Experiments were performed independently three times, with similar results. B, The phenotype of changes in susceptibility to B. cinerea after silencing the RhWRKY13 gene. The images were digitally extracted with scale bar = 1 cm. C, Quantification of B. cinerea disease lesion area on TRV-WRKY13- and TRV-00-inoculated rose petal discs. The box contains the middle 50% of the data. The upper edge (hinge) of the box indicates the 75th percentile of the data set while the lower hinge indicates the 25th percentile. The lines in the boxes indicate the median value of the data. It shows the lesion size from three biological replicates (n ≥ 48). The error bar represents sd. D, Relative expression of RhWRKY13 and RhCKX3 at 6 days after silencing RhWRKY13. Mean ± sd are shown from three technical replicates. Experiments were performed independently three times, with similar results. All statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

RhWRKY13 binds to the promoter of RhABI4, but not RhABI5

ABA and CK often play opposite roles during various biological processes in plants. Recent studies have suggested that ABI4 and ABI5 are critical players in the cross talk of CK and ABA in plants (Huang et al., 2017, 2018). Furthermore, a previous phylogenetic analysis of WRKY transcription factors in rose and Arabidopsis suggested that AtWRKY40 sequence is the closest to RhWRKY13 (Liu et al., 2019). AtWRKY40 has been reported to inhibit the expression of AtABI4 and AtABI5 by binding to their W-box cis-elements in Arabidopsis (Shang et al., 2010). We therefore investigated whether RhWRKY13 can simultaneously regulate ABA signaling in rose petals via RhABI4 and RhABI5, in addition to its suppression of RhCKX3 expression in the CK signaling pathway.

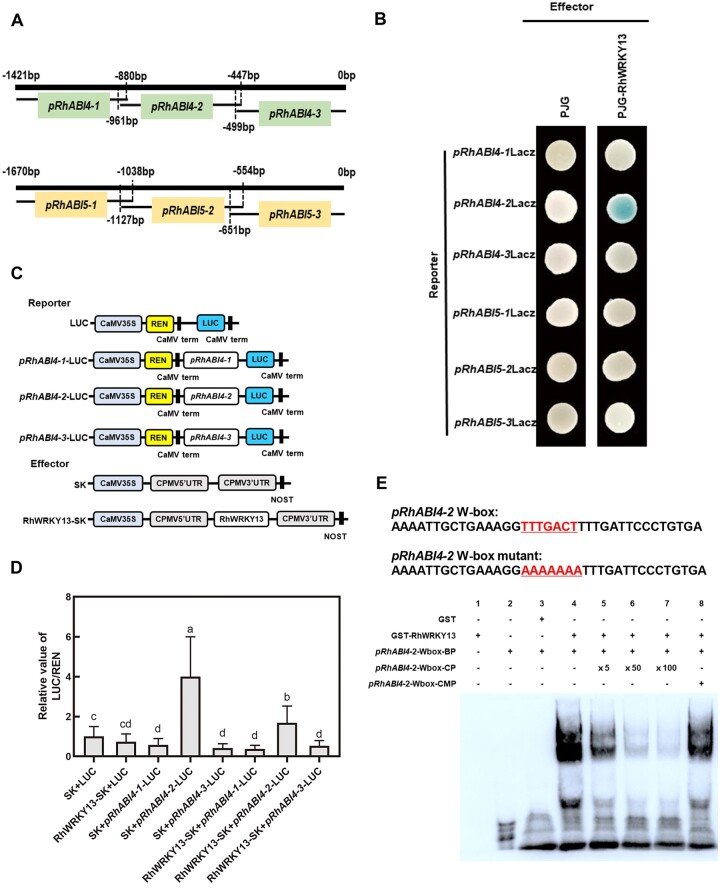

To this end, we identified the 1,421- and 1,670-bp promoter regions upstream of the RhABI4 and RhABI5 coding sequences, respectively (Figure 6A). Promoter region analysis using the New PLACE database suggested that the cis-elements in the promoters of RhABI4 and RhABI5 both include WRKY transcription factor binding sites, suggesting their potential to bind RhWRKY13. Indeed, a Y1H experiment showed that RhWRKY13 could bind to the −447 to −961 bp region of the RhABI4 promoter (Figure 6B). A dual-luciferase reporter assay also demonstrated that RhWRKY13 could bind to the RhABI4-2 promoter and inhibit its expression (Figure 6, C and D). However, RhWRKY13 could not bind to the promoter of RhABI5 in both the Y1H and dual-luciferase reporter assay (Figure 6, B–D). The EMSA further demonstrated the interaction of RhWAKY13 and the RhABI4-2 promoter W-box site (Figure 6E). Therefore, our results suggest that rose RhWRKY13 only binds to the cis-element of the RhABI4 promoter, but not the RhABI5 promoter. This indicates that RhWAKY13 reduces ABA signaling pathway in rose via repressing the transcription of ABA-response gene RhABI4.

Figure 6.

RhWRKY13 binds to the cis-element in the promoter of RhABI4, but not RhABI5. A, Schematic representation of the 1,421-bp RhABI4 promoter (pRhABI4) and 1,670-bp RhABI5 promoter (pRhABI5). The pRhABI4-1 fragment is 622 bp, the pRhABI4-2 fragment is 515 bp, the pRhABI4-3 fragment is 499 bp, the pRhABI5-1 fragment is 633 bp, the pRhABI5-2 fragment is 574 bp, and the pRhABI5-3 fragment is 651 bp. B, RhWRKY13 binds to the promoter of RhABI4-2 in the Y1H assay. The empty effector vector pJG4-5 (pJG) was used as a negative control. RhWRKY13 binds to the promoter of RhABI4-2 and promotes the expression of the downstream LacZ gene, which encodes β-galactosidase, turning blue with 80 mg/L X-gal. C, Schematic representation of double-reporter and effector plasmids used in the dual-luciferase reporter assay. D, The relative value of REN/LUC shows the interaction of RhWRKY13 and the RhABI4-2 promoter for the LUC reporter system. Mean ± sd are shown from three biological replicates. Significant differences are indicated by lowercase letters according to Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05). E, The interaction of RhWRKY13 and biotin-labeled pRhABI4-2 W-box as shown by an EMSA. Purified protein (1 μg) was incubated with 50 nM of the biotin-labeled wild-type pRhABI4-2 W-box probes (BP) and non-labeled mutant pRhABI4-2 W-box probes (CMP). The competition test was performed with non-labeled probes (CP) provided in 5-, 50-, or 100-fold excess over labeled probe.

Furthermore, in Arabidopsis, AtWRKY40 forms a complex with AtWRKY18 and AtWRKY60. However, RhWRKY45 and RhWRKY46, which showed sequence similarity to AtWRKY18 and AtWRKY60 (Liu et al., 2019), did not interact with RhWRKY13 via a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) experiment (Supplemental Figure S8). In addition, RhWRKY45 and RhWRKY46 did not bind to the promoter region of RhABI4 or RhABI5 in a Y1H assay (Supplemental Figure S9). This result further illustrates the functional differentiation of the RhWRKY13 and AtWRKY40 transcription factors.

Negative regulation of RhABI4 by RhWRKY13 contributes to the disease protection against B. cinerea

Since RhWRKY13 is a key regulator of the disease protection against B. cinerea in rose, the interaction of the transcriptional repressor RhWRKY13 and the RhABI4 promoter implied that ABA signaling might be involved in B. cinerea susceptibility in rose petals. Like many necrotrophic fungi, B. cinerea can synthesize ABA to promote its infection of plants (Tuomi et al., 1993; Siewers et al., 2004, 2006). Moreover, the application of exogenous ABA increases the susceptibility to B. cinerea in tomato and Arabidopsis (Audenaert et al., 2002; Abuqamar et al., 2017). However, it is inconclusive whether ABA increases the susceptibility of rose flowers to B. cinerea. We therefore tested whether exogenous ABA affects the susceptibility of rose petals to B. cinerea. Indeed, exogenous ABA application significantly increased the susceptibility of rose petals to B. cinerea (Supplemental Figure S10). Meanwhile, the content of ABA significantly decreased in B. cinerea-treated rose petals at 6 hpi and increased at 12 hpi. The change of ABA content was opposite to CK (Supplemental Figure S11A). However, the silencing of the RhCKX3 gene in petals caused an increase in CK content (Figure 3E), but did not affect the ABA content (Supplemental Figure S11B). These indicate that ABA has an opposite function to that of CK during the interaction between rose and B. cinerea. RhCKX3 as the downstream gene of RhWRKY13 has no connection with ABA.

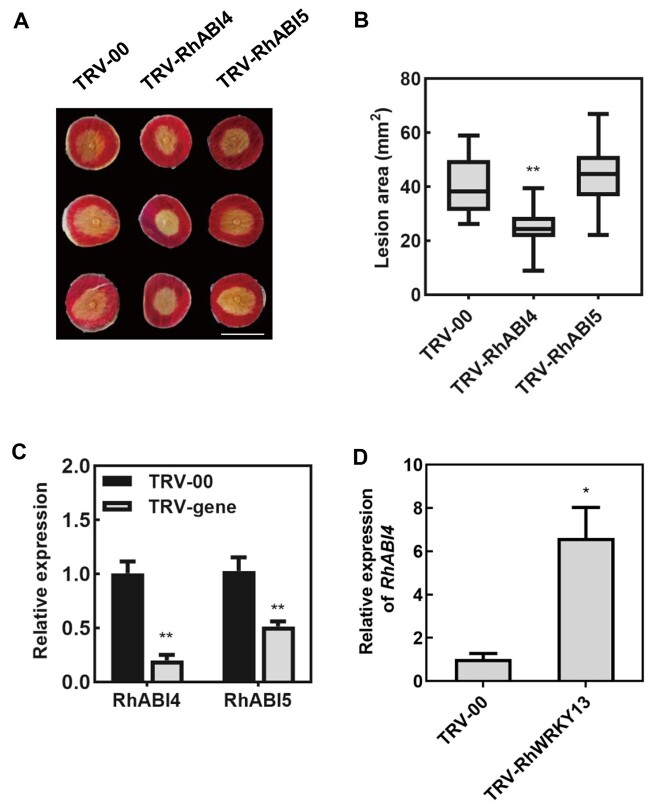

To investigate whether RhABI4 and RhABI5 participate in the disease protection to B. cinerea, we silenced RhABI4 and RhABI5 in rose petals using VIGS. The susceptibility of rose petals to B. cinerea decreased upon RhABI4 silencing (Figure 7), but was not changed upon RhABI5 silencing (Figure 7). The RhABI4 was induced under B. cinerea infection (Supplemental Figure S12) and the expression of RhABI4 increased in RhWRKY13-silenced petals (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

The abscisic acid response gene RhABI4 is required for disease protection against B. cinerea in rose petals. A, RhABI4- and RhABI5-silenced rose petal discs inoculated with B. cinerea. The photograph was taken at 60 hpi. The images were digitally extracted and scaled for comparison (scale bar = 1 cm). B, Quantification of B. cinerea disease lesions on TRV-RhABI4-, TRV-RhABI5-, and TRV-00-inoculated rose petal discs. The box contains the middle 50% of the data. The upper edge (hinge) of the box indicates the 75th percentile of the data set while the lower hinge indicates the 25th percentile. The lines in the boxes indicate the median value of the data. It shows the lesion size from three biological replicates (n ≥ 48). The error bar represents sd. C, Relative expression of RhABI4 and RhABI5 at 6 days post-silencing. Mean ± sd are shown from three technical replicates. Experiments were performed independently three times, with similar results. D, Relative expression of RhABI4 in RhWRKY13-silenced petals. Mean ± sd are shown from three technical replicates. Experiments were performed independently three times, with similar results. All statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

CK and ABA have a feedback regulation of RhWRKY13

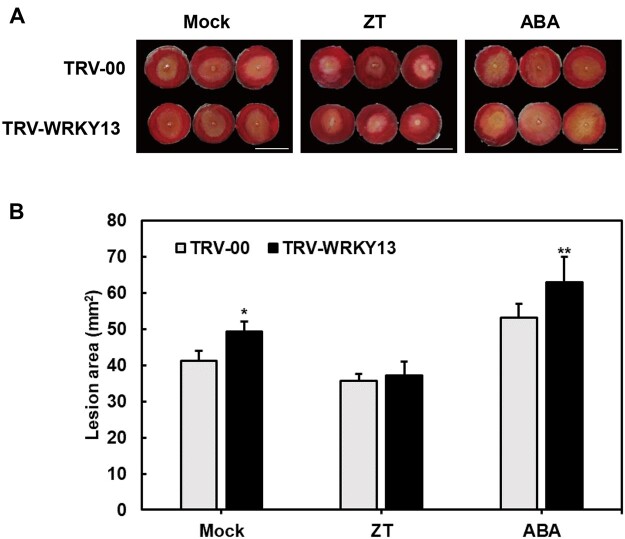

The expression pattern showed that RhWRKY13 was suppressed in CK-treated petals but induced in ABA-treated ones (Supplemental Figure S13). To identify if CK and ABA existed feedback regulation on RhWRKY13-involved disease protection, exogenous CK and ABA treatment was performed on RhWRKY13-silenced and TRV-00 petal discs. Petal discs after VIGS 5 days were treated with 100 µM ZT and 100 µM ABA for 24 h, respectively. We observed the susceptibility of RhWRKY13-silenced rose petals to B. cinerea was restored upon CK treatment, while the susceptibility in RhWRKY13-silenced petals can be increased by ABA treatment (Figure 8). These results indicate that RhWRKY13 as the node involves in CK metabolism and ABA signaling, and RhWRKY13 is fed back by ABA and CK to some extent.

Figure 8.

The effect of exogenous CK and ABA treatment on disease protection of RhWRKY13-silenced rose petals. A, Inoculation of B. cinerea on Mock-, 100 µM ZT, and 100 µM ABA-treated RhWRKY13-silenced petal discs. The photographs were taken at 60 hpi. The images were digitally extracted and scaled for comparison (scale bar = 1 cm). B, Quantification of B. cinerea disease lesions on Mock-, ZT-, and ABA-treated RhWRKY13-silenced petal discs. The graph shows the lesion size from three biological replicates (n ≥ 48) with the standard deviation. All statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

In summary, the B. cinerea-induced transcription factor RhWRKY13 inhibits ABA signaling in rose flowers by repressing the expression of RhABI4, and inhibits CK degradation by repressing the expression of RhCKX3, thereby decreasing the necrotrophic infection of B. cinerea on rose.

Discussion

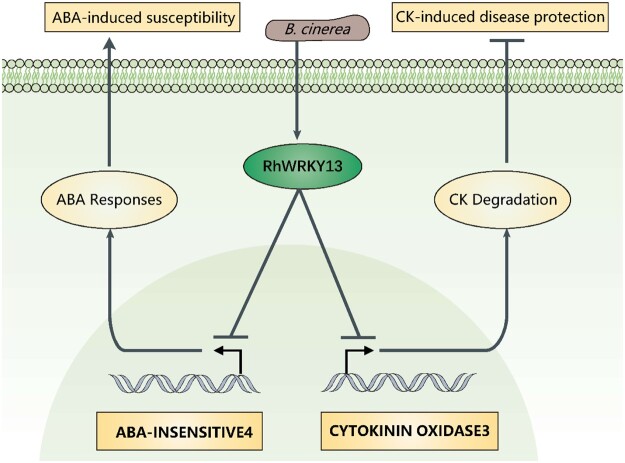

The flower petal is a short-lived and delicate organ, but it still needs to protect itself before completing its opening and fertilization. Rose petals are easily infected by the necrotrophic pathogen B. cinerea, resulting in severe economic losses of this important ornamental crop worldwide. In the present study, we showed that there is an active mechanism in rose petals that upregulates RhWRKY13 expression upon perception of B. cinerea infection. RhWRKY13 acts as a transcriptional repressor and simultaneously inhibits the expression of the CK degradation gene RhCKX3 and the ABA response gene RhABI4, thereby slowing the degradation of CK and repressing ABA signaling to facilitate disease protection against B. cinerea (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Model describing the involvement of RhWRKY13 in ABA and CK signaling and the disease protection against B. cinerea. Botrytis cinerea induced transcription factor, RhWRKY13, that can regulate disease protection in rose. Importantly, RhWRKY13, acts as a critical regulator, has opposite effects on CK content and ABA signaling by simultaneously inhibiting CK degradation (CKX3, RhCKX3) and downregulating ABA responses (ABA insensitive4, RhABI4) in the rose petal. The increased CK content and reduced ABA responses result in enhanced disease protection to B. cinerea. Arrows indicate positive regulation and T-bars indicate negative regulation.

The plant hormones CK and ABA play opposite roles in the disease protection against B. cinerea

The interactions between invading pathogens and their host plants involve various chemical signaling, in which phytohormones play crucial roles. Previously, a role of JA and ET was demonstrated in the disease protection against B. cinerea in rose petals (Cao et al., 2019), whereas the implications of other hormones remain unclear.

During colonization, necrotrophic fungi such as B. cinerea induce senescence in their host plant tissues. For example, B. cinerea and many other necrotrophs produce and release ABA, a known inducer of senescence, during their infection (Tuomi et al., 1993; Siewers et al., 2004, 2006). Previous studies have demonstrated that ABA promotes petal senescence in rose (Ma et al., 2018). In this article, we showed that during B. cinerea infection, ABA content decreased at the early stage of infection (6 hpi), while increased at the late stage of infection (12 hpi) (Supplemental Figure S11A). It might be due to the large amount of ABA produced by the Botrytis itself during the infection process. Meanwhile, exogenous application of ABA increased susceptibility of rose petals to B. cinerea (Supplemental Figure S10), whereas silencing of the ABA signaling gene RhABI4 reduced B. cinerea susceptibility (Figure 7). Consistent with this, tomato sitiens mutants with reduced ABA levels and the Arabidopsis abi4-1 mutant with inactivated ABA signaling are less susceptible to B. cinerea than wild-type plants (Audenaert et al., 2002; Achuo et al., 2006).

CK often plays opposite roles to that of ABA in various plant processes, such as the longevity of plant organs. In contrast to necrotrophic pathogens, obligate biotrophic fungi and gall-forming pathogenic bacteria use CK to facilitate their infection of plants. For example, Agrobacterium tumefaciens induces crown galls by a T-DNA integrated into the plant chromosome to produce CK and auxin (Lee et al., 2009). Similarly, obligate biotrophic fungal pathogens such as Puccinia striiformis produce CK to modulate the physiology of host plants and enhance their pathogenicity (Walters et al., 2008). In contrast to ABA, CK can delay senescence of flowers in many plant species, including rose (Mayak and Halevy, 1970), and therefore may potentially affect disease protection against necrotrophs such as B. cinerea. Indeed, in the present study, we showed that the application of both synthetic CK (6-BA) and naturally occurring CK (ZT) enhanced disease protection of rose against B. cinerea (Figure 1 and Supplemental Figures S1 and S2). Meanwhile, the endogenous CK was induced by B. cinerea at the early infection time point (6 hpi). These results are consistent with the previous finding that spraying of 6-BA on rose flowers enhanced disease protection against B. cinerea (Argueso et al., 2012; Gupta et al., 2020).

Rose plants down-regulate RhCKX3 leading to disease protection against B. cinerea

Although there are some exceptions, it is generally found that ABA and CK are crucial accelerants and suppressants of senescence, respectively (Ma et al., 2018), and therefore play opposite roles in the disease protection against B. cinerea. However, it is still unknown if host plants activate or repress their CK/ABA-related genes to promote disease protection to necrotrophic pathogens and whether their action is interdependent.

To investigate if the plant actively regulates endogenous CK content as part of its mode of disease protection, we analyzed the expression of CK-related genes under B. cinerea infection. In plants, CK is mainly synthesized in the root; we therefore investigated if a cut rose flower can repress CK degradation to maintain the CK content. We demonstrated that RhCKX3 is a key player involved in CK-mediated disease protection against B. cinerea in rose flowers. This is supported by the expression pattern of RhCKX3, which is significantly repressed by B. cinerea infection (Figure 3A). In contrast, the transcript levels of other members of the RhCKX gene family were not down-regulated during B. cinerea infection (Supplemental Figure S5). Importantly, the reduced pathogen growth and increased CK content of the RhCKX3-silenced plants demonstrated the role of this gene in the disease protection against B. cinerea (Figure 3).

Simplistically, CK, ABA, and their cross talk play a regulatory role in the susceptibility of rose petals to B. cinerea. The senescence-related progress is repressed as one of the CK-induced disease-protection strategies, the level of self-CK acts as an earlier swift signal to active pathogen response of rose. CK-induced disease protection seems a “directly” signal, even earlier than ET, one of the classical defense hormones against necrotrophic pathogens, that regulated the PRR trafficking (Pizarro et al., 2018; Gupta et al., 2020).

RhWRKY13 acts as a regulator of the disease protection against B. cinerea in rose petals

Commercially, the cut rose is harvested before its opening and pollination. This stage of flower has to protect themselves from various pathogens. The rapid change in RhCKX3 expression upon B. cinerea infection implied that there might be a mechanism in rose petals that regulates CK content for its disease protection. WRKY transcription factors participate in the regulation of plant growth and development, abiotic stress responses, and disease response. Recently, a genome-wide analysis identified 56 WRKY genes in rose (Liu et al., 2019). Here, we demonstrated that RhWRKY13 acts as a regulator of RhCKX3 and RhABI4 and that its expression was significantly up-regulated in B. cinerea-infected rose petals. As revealed by Y1H and dual-luciferase reporter assays as well as EMSAs, RhWRKY13 binds to the promoter of RhCKX3 and RhABI4 (Figures 4 and 6) and regulates the expression of both genes (Figures 5D and 8D). Silencing of RhWRKY13 in rose petals leads to increased susceptibility (Figure 5), which is opposite to the effect of silencing RhCKX3 or RhABI4, which enhanced disease protection against B. cinerea. RhWRKY13 to some extent is fed back by CK and ABA (Figure 8). Therefore, we conclude that RhWRKY13 acts as a B. cinerea-induced transcription repressor and the RhWRKY13–RhCKX3/RhABI4 regulatory module plays an essential role in disease protection against B. cinerea in rose petals through increasing the levels of CK and repressing ABA signaling (Figure 9). Furthermore, the opposite regulatory effect of RhWRKY13 on CK metabolism (positive effect) and ABA signaling (negative effect) suggested that it is a key regulator of the interaction between CK and ABA.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and hormone treatments

Cut roses (Rosa hybrida) were harvested from the greenhouse at stage 2 of flower opening (Ma et al., 2005) and immediately delivered to the laboratory. The flowers were then recut to 25 cm in length and placed in a vase with distilled water for further experiments. For the hormone treatment of whole flowers, rose flowers were placed in vases containing 100 µM 6-BA, 100 µM ZT, or 100 µM ABA, or in deionized water as a control for 24 h. For the hormone treatment of petal discs, the petals were obtained from the outermost whorls of rose flowers, and then a 12-mm disc was punched from the center of each petal. The petal discs were then placed in aqueous solutions of 100 µM 6-BA, 100 µM ZT, or 100 µM ABA, or in deionized water as a control, for 24 h. The treated petal discs were washed with deionized water and placed on 0.4% agar (v/v), with 16 discs per petri dish for B. cinerea inoculation.

Botrytis cinerea inoculation

The method for B. cinerea inoculation on rose petals has been described previously (Cao et al., 2019). Briefly, the B. cinerea strain CAU8324 was grown on potato dextrose agar at room temperature for 14 days, or longer. The inoculum was prepared by harvesting B. cinerea spores with tap water and then suspending in half-strength PDB to a final concentration of 1 × 105 conidia/mL. For inoculation, 2 μL drops of B. cinerea inoculum or PDB (mock) were dropped onto the center of each petal disc, closed petri dishes to ensure 100% humidity. The inoculated petal discs were evaluated by observing the area of disease lesions at 60 hpi. Each inoculation was repeated at least three times, using at least 16 petal discs each time. Statistical analysis was performed by Student’s t test.

VIGS

To establish VIGS in rose petals, a 188-bp or a 246-bp fragment of the RhCKX3 coding region, a 349-bp fragment of the RhWRKY13 gene (105 bp from the 3′ coding region and 244 bp from the 3′ untranslated region), a 218-bp coding region of RhABI4, and a 245-bp coding region of RhABI5 were PCR amplified and inserted into the pTRV2 vector (Liu et al., 2002) to generate the TRV-RhCKX3-1, TRV-RhCKX3-2, TRV-RhWRKY13, TRV-RhABI4, and TRV-RhABI5 constructs, respectively. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1. The generated TRV constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium (A. tumefaciens) strain GV3101.

The method used to establish VIGS in rose petal has been described by Cao et al. (2019). Briefly, Agrobacterium carrying TRV constructs were grown in LB medium with 50 μg/mL kanamycin, 25 μg/mL rifampicin, 10 mM MES, and 20 μM acetosyringone. The overnight culture was then harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in an infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM 2-Morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES), and 200 µM acetosyringone, pH 5.6) at an OD600 of 1.5. A 1:1 mixture of Agrobacterium cultures carrying pTRV1 and each recombinant pTRV2 construct was then used for vacuum infiltration, where petal discs were immersed in the Agrobacterium suspension and infiltrated under a vacuum at 0.7 MPa. At 6 days post-TRV infection, the petal discs were inoculated with B. cinerea.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA of rose petals was extracted as described previously (Wu et al., 2017). One microgram of total RNA was used to synthesize the first‐strand cDNA with HiScript II Q Select RT SuperMix (Vazyme) in a 20‐μL reaction volume. The RT-qPCR was performed in the Step One Plus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the TB Green Premix RT‐qPCR kit (TAKARA). RhUBI2 was used as a housekeeping gene. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Quantification of endogenous CKs

Rose petals (100 mg) were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground to a powder. Each sample was coated with 100 μL coating buffer (1.5 g/L Na2CO3, 2.93 g/L NaHCO3, and 0.02 g/L NaN3, pH = 9.6) containing 0.25 μg/mL antigens against DHZR, ZR, or IPA. The coated plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. The quantification of CKs with VIGS samples was performed as described previously (Yang et al., 2001).

Y1H assay

The Y1H assay was performed as previously described (Lin et al., 2007). To establish Y1H screening for transcription factors that interact with the RhCKX3 promoter, the 1,040-bp promoter region of RhCKX3 was cloned into the pLacZ vector to generate pRhCKX3LacZ. The generated pRhCKX3LacZ plasmid was used as a bait for screening a yeast library including 80 rose transcription factors that are differentially expressed upon B. cinerea infection (Liu et al., 2018). To confirm the interaction of RhWRKY13 and the promoter regions of RhCKX3, RhABI4, and RhABI5, the coding sequence of RhWRKY13 was cloned into the pJG4-5 vector to generate pJG-RhWRKY13. The 1,040-bp promoter sequence of RhCKX3, the truncated RhABI4 promoter sequence (0 to −499 bp, −447 to −961 bp, and −880 to −1,421 bp from the start codon), and the truncated RhABI5 promoter sequence (0 to −651 bp, −554 to −1,127 bp, and −1,038 to −1,670 bp from the start codon) were cloned into the pLacZ vector. The pJG-RhWRKY13 and corresponding pLacZ plasmids carrying different promoter fragments were co-transformed into the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) strain EGY48 and grown on synthetic dextrose (SD) medium lacking Trp and Ura. The transformants were then transferred to SD medium containing 80 μg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-d-galactopyranoside (X-gal) for the color development of yeast colonies.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

For detecting the binding activity of RhWRKY13 to the promoter of RhCKX3, RhABI4, or RhABI5, the coding sequence of RhWRKY13 was cloned into the pGreenII62-SK vector, while the promoters of RhCKX3, RhABI4, or RhABI5 were cloned into the pGreenII 0800-LUC double‐reporter vector (Hellens et al., 2005).

The generated constructs were then transformed into Agrobacterium and grown overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with 50 μg/mL kanamycin, 25 μg/mL rifampicin, 10 mM MES, and 20 μM acetosyringone. The overnight culture was then harvested and resuspended in the infiltration buffer described above. A 10:1 mixture of Agrobacterium cultures carrying pGreenII0800-LUC and pGreenII62-SK constructs were then co-infiltrated into leaves of N. benthamiana by using a needleless syringe. The firefly luciferase (LUC) and Renilla luciferase (REN) activities were then measured at 3 days post infiltration by using the dual luciferase assay kit (Promega) under a GloMax 20/20 luminometer (Promega).

Purification of GST-RhWRKY13 recombinant protein and EMSA

The coding sequence (CDS) of RhWRKY13 was cloned into pGEX-4T (EcoRI/XhoI), N′-terminal fused with GST tag. The promoter DNA with W-box ((T)TTGACY, where Y is C or T) or mutant fragments was synthesized with botin labeled on both ends. The competed control, cold probe fragments were synthesized without botin labeled.R

The EMSA was performed as previous study (Wu et al., 2017). The GST-RhWRKY13 was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 induced by 0.2 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside, the cultures were incubated at 28°C for 12 h. The recombinant proteins were extracted from the cells and purified using glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA fragments and the purified proteins were incubated at 25°C for 40 min before separation with native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in 0.5× Tris/Borate/EDTA (TBE) buffer. EMSA was performed using a Light Shift chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce).

Y2H assay

The coding sequences of RhWRKY13, RhWRKY45, and RhWRKY46 were amplified from cDNA and cloned into pGADT7 (EcorI/XhoI) or pGBKT7 (EcorI/SalI). The generated constructs were co-transformed into yeast (S. cerevisiae) strain AH109. Transformants were grown on SD plates lacking Trp and Leu for spot assays and then spotted onto SD plates lacking Trp, Leu, His and Ade.

For the transcription activity assay, pGBKT-RhWRKY13, pGBKT7, and pGBKT7-GAL4-CAM were transformed into yeast strain AH109. Transformants were grown on SD plates lacking Trp for spot assays and then spotted onto SD plates lacking Trp and His, containing X-α-gal.

Phylogenetic analysis

All the amino acid sequences were aligned by ClustalW with default parameters. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the alignment result using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA 7.0 software with bootstrap = 1000. The gene accession numbers used for analysis were listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in Rosa chinensis “Old Blush” genome data libraries (https://lipm-browsers.toulouse.inra.fr/pub/RchiOBHm-V2/) and The Arabidopsis Information Resource (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) under accession numbers listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Treatment with the synthetic CK 6-benzylaminopurine leads to less B. cinerea growth in the whole flower.

Supplemental Figure S2. ZT treatment leads to less B. cinerea growth in the whole flower.

Supplemental Figure S3. CK itself had no inhibitory effect on germination or growth of B. cinerea in a plate assay.

Supplemental Figure S4. Phylogenetic analysis of the CKX genes in rose and Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure S5. Expression of the RhCKX genes during B. cinerea infection.

Supplemental Figure S6. RhWRKY13 represses transcription.

Supplemental Figure S7. The interaction of RhWRKY13 and biotin-labeled pRhCKX3 W-box1 and W-box2 as shown by an EMSA.

Supplemental Figure S8. RhWRKY45 and RhWRKY46 do not interact with RhWRKY13.

Supplemental Figure S9. RhWRKY45 and RhWRKY46 do not bind to the promoter of RhABI4 and RhABI5.

Supplemental Figure S10. Treatment with exogenous ABA increased B. cinerea growth in the rose petal.

Supplemental Figure S11. The contents of ABA in B. cinerea inoculated or RhCKX3-silenced petals.

Supplemental Figure S12. Expression of the RhABI4 during B. cinerea infection.

Supplemental Figure S13. The expression of genes in CK- and ABA-treated petals.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used in this study.

Supplemental Table S2. The accession numbers of genes in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Dr Saskia van Wees (Utrecht University, The Netherlands) for feedback on the manuscript and discussion during the writing process.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 31772344 and 31972444) to Z.Z.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Xintong Liu, Beijing Key Laboratory of Development and Quality Control of Ornamental Crops, Department of Ornamental Horticulture, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100083, China.

Xiaofeng Zhou, Beijing Key Laboratory of Development and Quality Control of Ornamental Crops, Department of Ornamental Horticulture, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100083, China.

Dandan Li, Beijing Key Laboratory of Development and Quality Control of Ornamental Crops, Department of Ornamental Horticulture, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100083, China.

Bo Hong, Beijing Key Laboratory of Development and Quality Control of Ornamental Crops, Department of Ornamental Horticulture, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100083, China.

Junping Gao, Beijing Key Laboratory of Development and Quality Control of Ornamental Crops, Department of Ornamental Horticulture, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100083, China.

Zhao Zhang, Beijing Key Laboratory of Development and Quality Control of Ornamental Crops, Department of Ornamental Horticulture, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100083, China.

X.L. and D.L. performed the experiments. X.L., X.Z., and Z.Z. analyzed the data. X.Z., J.G., and B.H. provided technical support and conceptual advice. X.Z. and Z.Z. designed the research. X.L. and Z.Z. completed the writing.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plphys/pages/general-instructions) is: Zhao Zhang (zhangzhao@cau.edu.cn).

References

- Abuqamar S, Moustafa K, Tran LP (2017) Mechanisms and strategies of plant defense against Botrytis cinerea. Crit Rev Biotechnol 37: 262–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achuo EA, Prinsen E, Hofte M (2006) Influence of drought, salt stress and abscisic acid on the resistance of tomato to Botrytis cinerea and Oidium neolycopersici. Plant Pathol 55: 178–186 [Google Scholar]

- Argueso CT, Ferreira FJ, Epple P, To JP, Hutchison CE, Schaller GE, Dangl JL, Kieber JJ (2012) Two-component elements mediate interactions between cytokinin and salicylic acid in plant immunity. PLoS Genet 8: e1002448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselbergh B, De Vleesschauwer D, Höfte M (2008) Global switches and fine-tuning—ABA modulates plant pathogen defense. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 21: 709–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audenaert K, De Meyer GB, Hofte MM (2002) Abscisic acid determines basal susceptibility of tomato to Botrytis cinerea and suppresses salicylic acid-dependent signaling mechanisms. Plant Physiol 128: 491–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berens ML, Berry HM, Mine A, Argueso CT, Tsuda K (2017) Evolution of hormone signaling networks in plant defense. Annu Rev Phytopathol 55: 401–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Yan H, Liu X, Li D, Sui M, Wu J, Yu H, Zhang Z (2019) A detached petal disc assay and virus-induced gene silencing facilitate the study of Botrytis cinerea resistance in rose flowers. Hort Res 6: 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Huh SU, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Paek KH, Hwang I (2010) The cytokinin-activated transcription factor ARR2 promotes plant immunity via TGA3/NPR1-dependent salicylic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell 19: 284–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elad Y (1993) Regulators of ethylene biosynthesis or activity as a tool for reducing susceptibility of host-plant tissues to infection by Botrytis cinerea. Neth J Plant Pathol 99: 105–113 [Google Scholar]

- Guan C, Wang X, Feng J, Hong S, Liang Y, Ren B, Zuo J (2014) Cytokinin antagonizes abscisic acid-mediated inhibition of cotyledon greening by promoting the degradation of abscisic acid insensitive5 protein in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 164: 1515–1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Pizarro L, Leibman‐Markus M, Marash I, Bar M (2020) Cytokinin response induces immunity and fungal pathogen resistance, and modulates trafficking of the PRR LeEIX2 in tomato. Mol Plant Pathol 21: 1287–1306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens RP, Allan AC, Friel EN, Bolitho K, Grafton K, Templeton MD, Karunairetnam S, Gleave AP, Laing WA (2005) Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods 1: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Hou L, Meng J, You H, Li Z, Gong Z, Yang S, Shi Y (2018) The antagonistic action of abscisic acid and cytokinin signaling mediates drought stress response in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 11: 970–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Zhang X, Gong Z, Yang S, Shi Y (2017) ABI4 represses the expression of type-A ARRs to inhibit seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant J 89: 354–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C-W, Efetova M, Engelmann JC, Kramell R, Wasternack C, Ludwig-Müller J, Hedrich R, Deeken R (2009) Agrobacterium tumefaciens promotes tumor induction by modulating pathogen defense in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Cell 21: 2948–2962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R, Ding L, Casola C, Ripoll DR, Feschotte C, Wang H (2007) Transposase-derived transcription factors regulate light signaling in Arabidopsis. Science 318: 1302–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Cao X, Shi S, Zhao N, Li D, Fang P, Chen X, Qi W, Zhang Z (2018) Comparative RNA-Seq analysis reveals a critical role for brassinosteroids in rose (Rosa hybrida) petal defense against Botrytis cinerea infection. BMC Genet 19: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SA, Kracher B, Ziegler J, Birkenbihl RP, Somssich IE (2015) Negative regulation of ABA signaling by WRKY33 is critical for Arabidopsis immunity towards Botrytis cinerea 2100. eLife 4: e07295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Li D, Zhang S, Xu Y, Zhang Z (2019) Genome-wide characterization of the rose (Rosa chinensis) WRKY family and role of RcWRKY41 in gray mold resistance. BMC Plant Biol 19: 522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YL, Schiff M, Dinesh-Kumar SP (2002) Virus-induced gene silencing in tomato. Plant J 31: 777–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N, Cai L, Lu W, Tan H, Gao J (2005) Exogenous ethylene influences flower opening of cut roses (Rosa hybrida) by regulating the genes encoding ethylene biosynthesis enzymes. Sci China Ser C: Life Sci 48: 434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N, Ma C, Liu Y, Shahid MO, Wang C, Gao J (2018) Petal senescence: a hormone view. J Exp Bot 69: 719–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayak S, Halevy AH (1970) Cytokinin activity in rose petals and its relation to senescence. Plant Physiol 46: 497–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok MC, Martin RC, Mok DWS (2000) Cytokinins: biosynthesis, metabolism and perception. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant 36: 102–107 [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama R, Watanabe Y, Fujita Y, Le DT, Kojima M, Werner T, Vankova R, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K, Kakimoto T, et al. (2011) Analysis of cytokinin mutants and regulation of cytokinin metabolic genes reveals important regulatory roles of cytokinins in drought, salt and abscisic acid responses, and abscisic acid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 23: 2169–2183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse CM, Van Der Does D, Zamioudis C, Leon-Reyes A, Van Wees SC (2012) Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 28: 489–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro L, Leibman-Markus M, Schuster S, Bar M, Meltz T, Avni A (2018) Tomato prenylated RAB acceptor protein 1 modulates trafficking and degradation of the pattern recognition receptor LeEIX2, affecting the innate immune response. Front Plant Sci 9: 257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond O, Gouzy J, Just J, Badouin H, Verdenaud M, Lemainque A, Vergne P, Moja S, Choisne N, Pont C, et al. (2018) The Rosa genome provides new insights into the domestication of modern roses. Nat Genet 50: 772–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Yan L, Liu Z-Q, Cao Z, Mei C, Xin Q, Wu F-Q, Wang X-F, Du S-Y, Jiang T, et al. (2010) The Mg-chelatase H subunit of Arabidopsis antagonizes a group of WRKY transcription repressors to relieve ABA-responsive genes of inhibition. Plant Cell 22: 1909–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewers V, Kokkelink L, Smedsgaard J, Tudzynski P (2006) Identification of an abscisic acid gene cluster in the grey mold Botrytis cinerea. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 4619–4626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewers V, Smedsgaard J, Tudzynski P (2004) The P450 monooxygenase BcABA1 is essential for abscisic acid biosynthesis in Botrytis cinerea. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 3868–3876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartzberg D, Kirshner B, Rav-David D, Elad Y, Granot D (2008) Botrytis cinerea induces senescence and is inhibited by autoregulated expression of the IPT gene. Eur J Plant Pathol 120: 289–297 [Google Scholar]

- Thomma BP, Penninckx IA, Broekaert WF, Cammue BP (2001) The complexity of disease signaling in Arabidopsis. Curr Opin Immunol 13: 63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi T, Ilvesoksa J, Laakso S, Rosenqvist H (1993) Interaction of abscisic acid and indole-3-acetic acid-producing fungi with Salix leaves. J Plant Growth Regul 12: 149–156 [Google Scholar]

- Walters DR, McRoberts N, Fitt BD (2008) Are green islands red herrings? Significance of green islands in plant interactions with pathogens and pests. Biol Rev 83: 79–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li L, Ye T, Zhao S, Liu Z, Feng Y-Q, Wu Y (2011). Cytokinin antagonizes ABA suppression to seed germination of Arabidopsis by downregulating ABI5 expression. Plant J 68: 249–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner T, Kollmer I, Bartrina I, Holst K, Schmulling T (2006) New insights into the biology of cytokinin degradation. Plant Biol 8: 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Ma N, Jia Y, Zhang Y, Feng M, Jiang CZ, Ma C, Gao J (2017) An ethylene-induced regulatory module delays flower senescence by regulating cytokinin content. Plant Physiol 173: 853–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zhang J, Wang Z, Zhu Q, Wang W (2001) Hormonal changes in the grains of rice subjected to water stress during grain filling. Plant Physiol 127: 315–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher E, Müller B (2016) Cytokinin synthesis, signaling, and function—advances and new insights. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 324: 1–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.