Abstract

Background

Yazidis in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq have been exposed to recurrent traumatic experiences associated with genocide and gender-based violence (GBV). In 2014, ISIS perpetrated another genocide against the Yazidi community of Sinjar. Women and girls were held captive, raped and beaten. Many have been forced into displacement. Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and suicide are high. Limited research has evaluated interventions delivered to this population.

Methods

This review explores how the global evidence on psychosocial interventions for female survivors of conflict-related sexual violence applies to the context of the female Yazidi population. We used a realist review to explore mechanisms underpinning complex psychosocial interventions delivered to internally displaced, conflict-affected females. Findings were cross-referenced with eight realist, semi-structured interviews with stakeholders who deliver interventions to female Yazidis in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Interviews also allowed us to explore the impact of COVID-19 on effectiveness of interventions.

Results

Seven mechanisms underpinned positive mental health outcomes (reduced PTSD, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation): safe spaces, a strong therapeutic relationship, social connection, mental health literacy, cultural-competency, gender-matching and empowerment. Interviews confirmed relevance and applicability of mechanisms to the displaced female Yazidi population. Interviews also reported increased PTSD, depression, suicide and flashbacks since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, with significant disruptions to interventions.

Conclusion

COVID-19 is just one of many challenges in the implementation and delivery of interventions. Responding to the mental health needs of female Yazidis exposed to chronic collective violence requires recognition of their sociocultural context and everyday experiences.

Key words: gender-based violence, internally displaced person, psychosocial, post-traumatic stress disorder, Yazidi

Background

In the past two decades, conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) against women and girls has received increased attention from the international community. CRSV is defined as ‘rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilisation, forced marriage and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, girls or boys that is directly or indirectly linked to a conflict’ (Guterres, 2019). As these forms of violence gain visibility, interventions responding to associated trauma have received greater investment (Tol et al., 2013; Wood, 2014).

Violence extends to post-conflict settings, where women and girls are at an increased risk, with severe consequences to their mental health (Hossain et al., 2021). This includes pathological distress (fear, sadness, anger, shame, sadness, guilt), anxiety disorders [post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)], depression, somatic complaints, substance abuse, suicidal ideation and self-harm. Social consequences include stigma and its sequelae – social exclusion and discrimination from their communities (Ventevogel et al., 2015).

Global prevalence of mental health disorders in these settings is estimated at 22.1% (Charlson et al., 2019). Although there is some evidence on the magnitude and risks of CRSV, up-to-date evidence on the contextual effectiveness, mechanisms of change and implementation of psychosocial interventions is missing. Evidence is particularly scarce as interventions face many implementation challenges, including scarcity of resources, low awareness about mental health disorders and stigma. As such, common therapeutic interventions might not be feasible or applicable in these contexts (Seidi and Jaff, 2019).

While the realist-informed review by Spangaro et al. (2015) on CRSV identified key mechanisms to prevent violence, they did not address context-specific mechanisms for the promotion of mental health amongst survivors. The most recent systematic review of psychosocial interventions for survivors of sexual violence included data ranging from over a decade ago (Tol et al., 2013). While the geographical scope and methodological quality of evaluations were limited, results on effectiveness of interventions were encouraging.

Research context

Trauma and mental health of the Yazidi population

The Yazidis are a Kurdish ethnoreligious group originating from the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), Syria, Turkey, Azerbaijan and Armenia (Erdener, 2017). Due to their minority status, Yazidis have experienced persistent marginalisation and oppression during the Ottoman Empire, and more recently, amongst Sunni Muslims (Jäger, 2019).

Experiences of violence include 74 genocides or ‘Fermans’ (Omarkhali, 2016), a word for the decrees which legitimised violence against Yazidis during the Ottoman Empire (Six-Hohenbalken, 2019). The most recent occurred in August 2014, when ISIS launched an attack on the Yazidi community of Sinjar in Northern Iraq (Jäger, 2019). ISIS's attack resulted in the death and kidnapping of 9900 Yazidis. Thousands were beheaded or burned alive; many perished from dehydration in an attempt to flee to Mount Sinjar (Cetorelli et al., 2017b). These atrocities have reactivated collective memories of previous genocides and displaced 400 000 Yazidis across the KRI (Dulz, 2016).

ISIS's attack was gender-specific: men were executed, boys were taken as child soldiers and women and girls were subjected to sexual slavery (Cetorelli et al., 2017b). One study amongst many reports an 8-year-old girl who had been raped hundreds of times during her 14-month captivity (Mohammadi, 2016). 92.6% of Yazidi women residing in an internally displaced person (IDP) camp experienced an average of 4.87 acts of violence during captivity (Goessmann et al., 2020). Mass killings and graves mean many don't know whether their relatives are still alive (Womersley and Arikut-Treece, 2019).

Conditions of displacement – inadequate water and housing, extreme temperatures, lack of access to basic resources and loss of legal documentation – lead to ongoing stress (Millar and Warwick, 2019). For those who wish to return to Sinjar, a continual threat of violence lingers. ISIS attacks have been documented throughout 2019 and 2020 (Global Network on Extremism & Technology, 2020). Improvised explosive devices are littered amongst destroyed infrastructure (UNMAS, 2019).

PTSD is the most widely reported mental health disorder amongst Yazidis, with an estimated prevalence of between 70 and 90% (Kizilhan and Noll-Hussong, 2020; Richa et al., 2020). Some suggest Yazidis are suffering from complex PTSD, owing to their prolonged exposure to multiple traumatic experiences (Hoffman et al., 2018). Rates of suicide and attempted suicide are high (Jaff, 2018; UNHCR, 2019). This is likely a gross underestimate due to its associated stigma (United Nations, 2017). Self-immolation has been reported in response to feelings of shame associated with sexual violence (Medicins Sans Frontieres, 2019). Online Supplementary Fig. S1 summarises the interactions between multiple traumatic exposures and their effect on Yazidi survivors' mental health.

COVID-19

SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) was declared a global pandemic on 11 March 2020; its first case was diagnosed in Iraq on 22 February 2020 (Hussein et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020).

Emerging evidence shows increased depression, anxiety, substance abuse and domestic violence since the outbreak (Galea et al., 2020; Othman, 2020; Röhr et al., 2020). Individuals have been faced with challenges to their psychological well-being – lifestyle changes, living conditions, school closures, movement restrictions and fear about spread of infection (Othman, 2020). Consequences are likely exacerbated in fragile contexts, especially amongst persons with pre-existing mental health conditions (IASC, 2020).

At the time of writing, only one study had examined the effect of COVID-19 on the mental health of a small sample of Yazidis in a camp near Dohuk (n = 38 women) (Kizilhan and Noll-Hussong, 2020). Between October 2019 and April 2020, female Yazidis experienced an 11%, 10% and 6% increase in PTSD, anxiety and depression, respectively.

Objectives

Limited literature has examined the effectiveness of interventions delivered to the displaced Yazidi population. We explore how global evidence on psychosocial interventions for female survivors of CRSV applies to the female Yazidi population. We also explore the implications of COVID-19 on the implementation and effectiveness of these interventions.

Methods

This study used a mixed-methods approach to explore how interventions work to improve the mental health of Yazidi survivors of CRSV, and in which circumstances. We used a realist review framework to evaluate how psychosocial interventions may trigger specific mechanisms that interact with the local context to produce intended and unintended outcomes, formulated as context-mechanism-outcome (CMO) configurations (De Souza, 2013) (Dalkin, 2015).

Following RAMESES reporting for realist reviews (online Supplementary Table S1), we began with an exploratory scoping of academic databases, PubMed, PubMed Central, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsychInfo, Scopus and Web of Science, using terms and eligibility criteria in Table 1. Databases were complemented by reference-list and grey literature screening. Scoping allowed us to formulate an initial context-intervention-mechanism-outcome (CIMO) configuration (Table 2). A CIMO was chosen instead of the more conventional CMO as this offers a clearer configuration for analysis of the interactions between interventions and mechanisms (Booth et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Search terms and eligibility criteria

| Component | Search terms | Eligibility criteria | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Included | Excluded | ||

| Type of intervention | ‘MHPSS’ OR ‘mental health’ OR ‘psychosocial’ OR ‘psychological’ | Any publication year due to specificity of topic | Pharmacological interventions |

| Intervention words | ‘Intervention’ OR ‘programme’ OR ‘service’ OR ‘healing’ OR ‘rehabilitation’ OR ‘therapy’ | ||

| Type of mental health condition | ‘Post-traumatic stress disorder’ OR ‘PTSD’ OR ‘trauma’ OR ‘depression’ OR ‘anxiety’ OR ‘fear’ OR ‘distress’ | If intermediate and/or primary outcomes were mental health indicators or constructs | Languages other than English |

| Setting | ‘Post-conflict’ OR ‘conflict affected’ OR ‘humanitarian setting’ OR ‘internally displaced’ OR ‘IDP’ OR ‘camp’ OR ‘settlement’ | Only populations living in IDP settings All ages can be affected by conflict and are found in IDP settings |

|

| Location | ‘Low and middle income countries’ OR ‘LMIC’ OR ‘low-resource setting’ | Grey literature: journal articles, theses, websites, reports, books and news articles | |

MHPSS interventions were ‘any type of local or outside support that aims to protect or promote psychosocial well-being and/or prevent or treat mental disorders’ (IASC, 2020). Grey literature was included so as to capture humanitarian work not published in academic journals. Utilising a diverse range of literature also provides an opportunity for richer theory development (Bunn et al., 2016). Grey literature sources included: UNHCR, UNFPA, UNICEF, World Health Organization, International Rescue Committee, International Organization for Migration, Médecins Sans Frontières and ALNAP. Due to limitations of the search tools on the ALNAP website, we searched the term ‘Yazidi’, as this was assumed to include all relevant data to the target population.

Table 2.

Our CIMO configuration

| Component | Initial programme theory | Refined programme theory |

|---|---|---|

| Context | Conflict-affected females who are internally displaced in low-resource settings. Have experience of historic and collective trauma, social and gendered inequality, live in poor displacement conditions with poor access to services | |

| Intervention | Group and individual psychotherapy (narrative exposure therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, interpersonal therapy and thought field therapy), livelihood programmes, EMDR, art therapy, relaxation techniques, counselling | |

| Mechanism |

|

|

| Outcome | Reduced PTSD, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Improved functioning scores, conduct behaviours, well-being | |

The context is the setting, the mechanism is a change in response or reasoning of participants upon introduction of the intervention, and outcomes are intended or unintended consequences of the intervention (Trickey et al., 2018). Our initial programme theory took into account authors' current views on which mechanisms may lead to positive mental health outcomes. This theory was tested and refined against results from the literature and stakeholder interviews.

‘COVID-19’ was excluded from our search terms as initial literature searches were conducted prior to the pandemic outbreak. As such, realist semi-structured interviews with stakeholders who deliver psychosocial interventions to female Yazidi IDPs were used to explore the impact of COVID-19 on the population's mental health, and to test our CIMO. Data from these interviews were presented separately to explicitly acknowledge stakeholders' contributions to knowledge production, as recommended by a recent publication in the field of realist synthesis (Abrams et al., 2021).

Stakeholders' public email addresses were identified through internet searches of humanitarian institutions in the region who were likely to have information needed to support, refute or refine the programme theory (Wong et al., 2016). Thirty-three stakeholders were recruited from seventeen institutions and eight participated. The remainder either didn't respond or objected, stating that they had no time, or did not work within the institutions anymore. All were aged 18 or over, including men and women. No compensation was given for their time.

Due to their semi-structured nature, interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes. Interviews were conducted one-on-one by one of the authors in English. Five consented to being audio-recorded. Two provided answers in writing, due to language barriers, where responses were written with the help of an English-speaking colleague in their institution (n = 1) or using an online translator (n = 1). The remaining stakeholder preferred not to be audio-recorded, so notes were taken.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Explanations were provided on the research objectives and procedures; ample opportunities for clarification and right to withdraw participation were given. To ensure strict online safety, access to interviews was password protected. Interview data were stored in an encrypted document. Risks of distress associated with research participation were considered minimal as interviews focused on work experiences, and did not collect data of a more personal nature. Ethics approval for qualitative data collection was obtained from the UCL Research Ethics Committee [ref.: 18701.001].

Interview transcripts and notes were analysed for recurrent themes using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This process was inductive: themes were coded without trying to fit them into a pre-existing framework. Identification of themes was semantic, based upon explicit views expressed.

Purposive sampling, involving iterative, snowballing techniques, was used to further develop, support, refute or refine our programme theory: what outcomes do psychosocial interventions delivered to female survivors of CRSV living in IDP settings have? What causes these outcomes (mechanisms)? (Wong et al., 2016). Records were also searched for interventions delivered to survivors of CRSV since the emergence of COVID-19, however no results were found. Sampling was complete at the point of theoretical saturation (Mogre et al., 2014). Records which met the eligibility criteria were included.

Literature was triangulated with interviews where similar themes were observed. One author analysed all data twice; where interpretation was difficult, the other author completed independent analysis, to reach a consensus. Table 2 outlines the refined programme theory.

Results

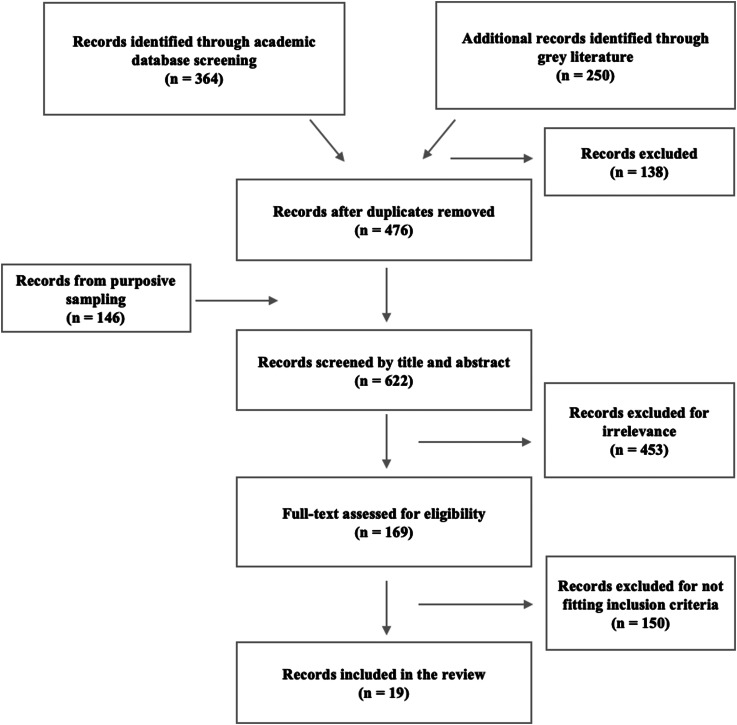

Figure 1 outlines the search strategy and yield. Nineteen records, spanning 2001–2020, were included. Interventions were delivered in nine post-conflict settings: KRI (n = 8), Uganda (n = 4), Nigeria (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), Sri Lanka (n = 1), Bosnia (n = 1), Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (n = 1), Rwanda (n = 1) and Burundi (n = 1).

Fig. 1.

Search strategy and yield.

Interventions consisted of art therapy (n = 2), eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) (n = 1), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) v. thought field therapy (n = 1), CBT (n = 1), interpersonal therapy (IPT) v. creative play (n = 1), narrative exposure therapy for children (KIDNET) v. meditation-relaxation (MED-RELAX) (n = 1), livelihood programmes (n = 2), trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT) (n = 1), narrative exposure therapy (NET) (n = 1), IPT v. NET (n = 1), trauma workshop (n = 1), counselling (n = 2), multi-component intervention (n = 1), group therapy (n = 2) and a resilience programme (n = 1).

Proposed underpinning mechanisms

We identified seven mechanisms which explain how interventions might work to improve the mental health and well-being of female survivors of CRSV in low-resource settings: safe spaces, a strong therapeutic relationship, empowerment, mental health literacy, social connection, gender-matching and cultural competency. Outcomes included reduced PTSD, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, attempted suicide and improved well-being. Table 3 outlines the results.

Table 3.

Literature included in the review

| Study | Study design, target population, sample size (n = ) and intervention | Mechanism | Outcomes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health literacy | Cultural competency | Strong therapeutic relationship | Safe spaces | Empowerment | Gender matching | Social connection | |||

| (Abdulah and Abdulla, 2020) | Pre and post-test quasi-experimental study of art therapy delivered to Yazidis (females, aged 10–27) in Sharya camp, KRI (n = 14) |

|

|||||||

| (Acarturk et al., 2016) | Randomised control trial (RCT) of EMDR delivered to adults (males and females, aged ≥18) in Kilis Refugee Camp at the Turkish–Syrian border, Turkey (n = 70)* |

|

|||||||

| (Atulomah et al., 2020) | Case-control study of motivational counselling delivered to IDPs (males and females, aged ≥60) living in 2 IDP camps, Borno State Nigeria (n = 40) |

|

|||||||

| (Bass et al., 2016) | RCT of trauma counselling and psychoeducation delivered to IDPs (males and females, aged ≥18) living in Dohuk governorate, KRI (n = 209) |

|

|||||||

| (Bolton et al., 2007) | RCT of group IPT v. creative play delivered to adolescents (males and females, aged 14–17) in 2 IDP camps, northern Uganda (n = 304) |

|

|||||||

| (Catani et al., 2009)** | RCT of KIDNET v. MED-RELAX delivered to war-affected children (girls and boys, aged 8-14) in post-Tsunami IDP camps, Manadkadu, Sri Lanka (n = 31) |

|

|||||||

| (Dybdahl, 2001) | RCT of semi-structured group therapeutic discussion delivered to mothers (aged 20-44) living in refugee settlements and private accommodation for IDPs in Tulza, Bosnia (n = 42) |

|

|||||||

| (Freij, 2018) | Qualitative evaluation (interviews and FGDs) of livelihood programme delivered to IDPs (males and females, aged 18–35) in Dohuk Governorate, KRI (n = 72) |

|

|||||||

| (Kaya and Luchtenberg, 2018) | Qualitative evaluation (interviews and FGDs) of livelihood programme delivered to IDPs (males and females, aged ≥18) in camps and settlements across KRI (n = 129) |

|

|||||||

| (Lancaster and Gaede, 2020) | Pre and post-test experimental study of a resiliency programme delivered to IDPs (males and females, aged 12–98) in Khanke, Essien, Kabarto and Soran camps, KRI (n = 766) |

|

|||||||

| (Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., 2013) | Quasi-experimental study of group therapy intervention delivered to war-affected IDPs (males and females, aged ≥18) in four trauma clinics, northern Uganda (n = 613) |

|

|||||||

| (O'Callaghan et al., 2013) | RCT of TF-CBT delivered to war-affected girls (aged 12–17) rescued from brothels in Beni, DRC (n = 52) |

|

|||||||

| (Schaal et al., 2009) | RCT of NET v. IPT delivered to youths (males and females, aged 14–28) living in child-headed households and orphanages in Kigali, Rwanda (n = 26) |

|

|||||||

| (Schneider et al., 2018) | Case-control study of NET delivered to IDPs (males and females, aged 18-80) in former IDP camps (Anaka, Pabbo, Koch Goma) and villages (Gulu and Nwoya district), Uganda (n = 1131) |

|

|||||||

| (Seidi et al., 2020) | Case series study of CBT v. thought field therapy (TFT) delivered to IDPs (males and females, aged 18-43) receiving treatment at two centres in Kalar City, KRI (n = 31) |

|

|||||||

| (Sonderegger et al., 2011) | Case-control study of CBT delivered to IDPs (males and females, aged 15-56) living in Pabbo and Ajulu IDP camps, Uganda (n = 202) |

|

|||||||

| (The Lotus Flower, 2017) | Annual report assessment of art therapy delivered to IDPs (females, aged ≥18) in Rwanga camp, Dohuk governorate, KRI (n = 85) |

|

|||||||

| (Womersley and Arikut-Treece, 2019) | RCT of psychotherapy, EMDR, art therapy, delivered to Free Yezidi Foundation Women's Centre members (females, aged ≥18) in Khanke IDP camp, Dohuk governorate, KRI (n = 200) |

|

|||||||

| (Yeomans et al., 2010) | RCT of 3-day trauma workshop with and without psychoeducation delivered to participants (males and females, mean age 38.6 years, SD =12.8) in two IDP camps in rural Burundi (n = 113) |

|

|||||||

| TOTAL | 10 | 16 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 12 | ||

Footnote: *Acaturk et al., 2016. Record was included despite intervention delivery to Syrian refugees as camp was located on the Syrian border. **Catani et al., 2009. Record was included due to exposure to war experiences, but note additional exposure to Tsunami.

Mechanism 1: delivery of interventions in safe spaces

Delivery of EMDR at a camp-kindergarten, where participants could avoid stigma by pretending they were dropping off their children, provided a place for participants to engage with treatment without fear of rejection (Acarturk et al., 2016). Art-based interventions at a women's centre enabled female Yazidis to share experiences of sexual violence in a women's only environment (The Lotus Flower, 2017). Safe spaces were important for displaced women to attain livelihood skills, build social networks and express themselves (Kaya, 2018).

Focus group discussions (FGDs) with Yazidi females attributed delivery of interventions in a safe space as a key reason for their improved well-being (Womersley and Arikut-Treece, 2019). This was supported by one stakeholder: ‘We work within a safe space and try to make it as accessible as possible…this could be a Community Centre or it could be a room in a youth centre’ [Interview 3].

Mechanism 2: strong therapeutic relationship

Beyond physical safety, survivors of CRSV need to feel emotionally safe to share their experiences. Staff who felt ‘like family’ were attributed to the success of a multi-component intervention with Yazidi females (Womersley and Arikut-Treece, 2019). In the DRC, participants attributed their improved PTSD, depression and anxiety scores to the delivery of TF-CBT by facilitators known to them (O'Callaghan et al., 2013). Trauma-based counselling, where emphasis was placed on therapeutic relationship, reduced depressive symptoms (Bass et al., 2016).

Two stakeholders necessitated a trusting therapeutic relationship for Yazidis due to their experiences of persecution: ‘They went through 74 genocide alone, so they always have negative thoughts about their neighbours’ [Interview 7].

Mechanism 3: gender-matching

Due to the sensitive and gendered nature of CRSV, gender-matching of therapist and participant proved effective in reducing depression, PTSD and anxiety (Schaal et al., 2009; Sonderegger et al., 2011; Acarturk et al., 2016; Lancaster and Gaede, 2020). Delivery of IPT to small gender-homogenous groups, with gender-matched participants and therapists, significantly reduced depressive symptoms (Bolton et al., 2007).

The Yazidi community is male dominated [Interview 5], so gender norms tend to dictate engagement with psychosocial interventions: ‘the man often refuses to engage in family therapy as men should be brave, should not cry and talk about himself’ [Interview 4]. Societal stigma associated with CRSV means having a female therapist can allow women to share their experiences: ‘For some of the Yazidis it makes a difference that you are a woman – if a male psychotherapist they wouldn't be able to talk about it due to the culture and gender norms’ [Interview 4]; ‘There are definitely people who prefer women… It's a lot easier for them to speak about their own personal details of such events with a female’ [Interview 3].

However, an intervention delivered by a man resulted in long-lasting reductions in suicidal ideation and suicide attempts amongst Yazidi women (Abdulah and Abdulla, 2020). This could be explained by resource scarcity: ‘Often we don't have female experts who have good training or information about treating patients therefore the survivor takes the male therapist’ [Interview 8].

Mechanism 4: cultural competency

Positive outcomes from gender-matching more broadly reflect the need for culturally competent intervention design and delivery. Interventions delivered by native facilitators reduced PTSD symptoms (Catani et al., 2009; Yeomans et al., 2010) and improved well-being (Dybdahl, 2001). Intervention delivery by community health workers, based on a curriculum developed by experts in Iraqi culture, reduced depression (Bass et al., 2016). Culturally-relevant activities increased participants' comfort (Sonderegger et al., 2011). A CBT intervention, when delivered to a largely illiterate population, showed minimal success when compared to thoughtfield therapy, which better suited participants' preference for traditional healing (Seidi et al., 2020). An art-based intervention allowed participants to understand their trauma in a way which made sense to them (Abdulah and Abdulla, 2020).

Delivering interventions in a culturally appropriate way helped to develop a trusting relationship: ‘I also learnt Kurmanji (the main dialect used by Yazidis), so that I can speak to Yazidis and relate to them and build trust’ [Interview 4].

However, a lack of trained facilitators is a major barrier: ‘Very few people from the region who do understand cultural notions of health are trained. It's very rare to have someone who's able to adapt a model that is Western or that is foreign to the region’ [Interview 3].

Mechanism 5: social connection

Group interventions allowed participants to discuss their traumatic experiences, amounting in faster declines in depression and PTSD compared to non-treatment groups (Schaal et al., 2009; Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., 2013). Mothers with experience of severe war activities reported a positive sense of social support in group therapy (Dybdahl, 2001). Peer support was so central to an intervention's success amongst adolescent females that they formed small groups outside of the intervention, to practice techniques learned (O'Callaghan et al., 2013). Female Yazidis felt they had gained supportive relationships, improved self-esteem and psychological safety in an art-based intervention (Abdulah and Abdulla, 2020).

Stakeholders noted that group-based interventions ‘allowed survivors to connect and learn from their peer groups…facilitating resiliency and emotional support from people who have experienced similar things, making them feel like they are not alone’ [Interview 5]. This is particularly important for the Yazidi community due to their persistent experiences of violence which require ‘collective healing because violence was collective in nature’ [Interview 1]. Another stakeholder noted that there was a benefit to Yazidis engaging with others outside of their family: ‘These group activities also activate an alternative social network rather than dwelling on their trauma within their families’ [Interview 3].

However, stigma is a major challenge for group interventions: ‘[stigma] is something that we deal with, on a day-to-day basis’ [Interview 3]. Stigma associated with experiences of CRSV is particularly widespread: ‘Society forced her to forget the past and what happened because it happened by people who are not of their religion. Forgetting what happened is believed to be better’ [Interview 1].

Individual psychotherapy was therefore deemed more beneficial [Interview 3 and 8], because ‘they feel more comfortable if they don't have to talk about people they know or family members’ [Interview 8]. Art therapy also helped to heal from trauma without having to speak about it: ‘Survivors can express themselves better and share what they cannot speak about in the community in their drawing’ [Interview 1].

Mechanism 6: mental health literacy

Integrating services with psychoeducation was another means to engage Yazidis and overcome stigma [Interview 7]. Mental health literacy, achieved through psychoeducation, reduced PTSD symptoms (Schneider et al., 2018). Psychoeducation delivered to guardians of sexually-exploited orphans helped to re-establish contact with family and reduce stigma (O'Callaghan et al., 2013; Acarturk et al., 2016).

However, where psychoeducation was replaced by a workshop on safety and trust, participants experienced greater reductions in PTSD. Reduced effectiveness of psychoeducation could be due to participants' increased engagement with their trauma, and so greater risk of re-traumatisation (Yeomans et al., 2010).

Stakeholders supported the need for mental health literacy: ‘Yazidi women are illiterate as women aren't allowed to go to school and don't know what psychological disorders are…They just hear that they are crazy and that you shouldn't go to a psychiatrist because people will know that you are crazy. This means you need to do psychoeducation for these terms’ [Interview 5].

Mechanism 7: empowerment

Art-based interventions reduced suicidal ideation by empowering participants to feel like they had a meaningful purpose: ‘I was so happy in the course, because I was thinking of being an artist’ (Abdulah and Abdulla, 2020); ‘I now have my own sewing machine…my hope for the future is to become a highly skilled tailor who can afford a good life for my children’ (The Lotus Flower, 2017). An intervention which concluded with a graduation ceremony, where participants' guardians watched them receive certificates, led to significant reductions in depression and anxiety (O'Callaghan et al., 2013).

Livelihood interventions reduced depressive symptoms and allowed Yazidi women to ‘get a job in the future and build selfreliance… and increase life skills’ [Interview 1] (Bass et al., 2016; Kaya and Luchtenberg, 2018). This is particularly important because ‘ISIS's attack caused the survivors to deny their wishes and ability to have a future’ [Interview 1]. This narrative has extended beyond the attack: Western media has ‘focused on Yazidis (and especially women) as weak victims. Many staff therefore find it challenging to help them move past the idea that they are victims’ [Interview 3]. The ability to gain skills has also relieved some of the ‘double burden’ of stress related to ‘poverty after the loss of everything from the ISIS attack’ [Interview 1].

The impact of COVID-19 on mechanisms

Table 4 outlines the findings from stakeholder interviews on the impact of COVID-19 on Yazidi females. Interviews revealed that Yazidi females have experienced increased flashbacks, PTSD, depression and anxiety since the start of the pandemic. We suggest that a change in the context and delivery of interventions has subsequently affected mechanisms and outcomes within our CIMO configuration. Closure of safe spaces, online delivery of interventions, isolation from social networks, redistribution of support workforce, loss of livelihoods, and increased rates of IPV have contributed to Yazidis' suffering.

Table 4.

The impact of COVID-19 on our CIMO configuration

| Component | Refined programme theory | After onset of COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| Context | Conflict-affected females who are internally displaced in low-resource settings. Have experience of historic and collective trauma, social and gendered inequality, live in poor displacement conditions with poor access to services | Conflict-affected females who are internally displaced in low-resource settings. Have experience of historic and collective trauma, social and gendered inequality, live in poor displacement conditions with poor access to services, during a global pandemic |

| Intervention | Group and individual psychotherapy (narrative exposure therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, interpersonal therapy and thought field therapy), livelihood programmes, EMDR, art therapy, relaxation techniques, counselling | |

| Mechanism |

|

|

| Outcome | Reduced PTSD, depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Improved functioning scores, conduct behaviours, well-being |

|

Discussion

We aimed to address the evidence gap on how interventions work to improve the mental health of displaced female Yazidi survivors of CRSV in the KRI. A realist review of psychosocial interventions delivered to female survivors of CRSV identified seven mechanisms: safe spaces, a strong therapeutic relationship, empowerment, mental health literacy, social connection, gender-matching and cultural competency. Interviews with stakeholders who deliver psychosocial interventions to female Yazidis in the KRI confirmed relevance of these mechanisms. Interviews also confirmed that COVID-19 has worsened Yazidi survivors' mental health.

Mechanisms in the research context

Safe spaces should be an essential component of interventions delivered to female Yazidi IDPs, whose experiences of persistent marginalisation continue to threaten their existence (Persecution Prevention Project, 2019). Displacement means they are unable to express their Yazidi identity, nor are they safe to return to home. The ongoing captivity of 3500 women and 1200 children by ISIS is a stark reminder of continual genocidal ideology in the region, and the inability of Iraqi authorities to protect the community (Persecution Prevention Project, 2019; Womersley and Arikut-Treece, 2019). ISIS's destruction of Yazidi shrines means there are no longer places to practice their rituals and customs (Isakhan and Shahab, 2020).

Aside from violence perpetrated by other groups, Yazidi females are exposed to violence in their interpersonal relationships. In 2019, 66% of female Yazidi IDPs reported past-year exposure to IPV (Goessmann et al., 2020). These high rates are situated within the broader context – Iraq has the largest social and legal gender inequalities in the world (The World Bank Group, 2019). For a state which has so frequently been fractured by war, a ‘culture of violence’ has become normalised and women's bodies are readily exploited (Heise, 1998; Ahram, 2019).

It is therefore unsurprising that the closure of safe spaces due to COVID-19 has resulted in alarming increases in IPV. In one study, 346 married women in the KRI reported an increase in IPV from 32.1 to 38.7% (Mahmood et al., 2021). Stakeholder interviews echoed this pattern of increased violence within the Yazid community.

However, nurturing feelings of safety extend beyond the physical space. Feeling ‘safe to tell’, a mechanism previously reported by Spangaro (2015), is particularly important for Yazidi survivors of CRSV, where sexual relations with those outside of the community are condemned. Fear of discrimination has been attributed to suicide and mental illness (Goodman et al., 2020). One study illustrated that 44.6% of formerly enslaved Yazidi females felt extremely excluded by community members, and 32.3% felt worried about not being able to get married or continue their marriage (Erdener, 2017).

As such, a strong therapeutic relationship is a suitable mechanism to help Yazidi survivors to speak of their trauma and has been attributed to positive intervention outcomes in non-conflict settings (Cloitre et al., 2002; Keller et al., 2010). However, applicability of this mechanism needs testing, for persistent persecution has amounted in a strong distrust of others, limiting engagement with psychosocial support services (Strang et al., 2020). As expressed by one care provider: ‘Some of my patients do not believe we can help them at all. Earning their trust is the most difficult challenge’ (Jiyan Foundation for Human Rights, 2017).

Gender-matching could be one effective mechanism to support the building of trust, particularly for survivors of gender-based violence, where the abuse itself is centred around gendered identity (Ward and Marsh, 2006). A gendered preference for health-seeking has already been established amongst Yazidis, attributed to high prevalences of IPV and gynaecological issues (Cetorelli et al., 2017a).

Other important cultural factors must also be taken into consideration to aid the safe and effective delivery of interventions. Western models of mental illness are incompatible with the way Yazidis view suffering: distress is often described as physical in origin, such as ‘liver burning’ (Womersley and Arikut-Treece, 2019).

However, to scale up culturally competent interventions requires considerable resources. As home to one-third of Iraq's oil resources, the KRI is a region of ongoing conflict and limited responsibility is assumed for minority populations (The Kurdish Project). Economic under-development, emigration of healthcare professionals, poor management and war damage are widespread (Al-Khalisi, 2013).

To approach this issue, group interventions appear to be one cost-effective way of dealing with large numbers of individuals who need support (Nakimuli-Mpungu et al., 2013; van Westrhenen et al., 2017). Social connection is one of the most consistent predictors of psychological adaptation following a range of traumatic events, including forced displacement (Shishehgar et al., 2017). Social connection is culturally relevant for Yazidis, whose collective mourning is a common coping behaviour for their collective trauma, and reflects the behaviour of other genocide survivors (Kanyangara et al., 2007; Erdener, 2017; Arikut-Treece, 2019).

Where stigma is a common challenge to group interventions, mental health literacy can help to normalise survivors' feelings and improve access to psychological services (Bosqui and Marshoud, 2018). A lack of knowledge about mental health problems is one of the key barriers to help-seeking amongst children and adolescents in high-income countries (Radez et al., 2021). For Yazidis, illiteracy has been directly associated with suicide and mental illness amongst women and girls, attributed to their inability to source and access services (International Organization for Migration, 2011).

Greater engagement with services can also empower individuals to seek employment, resulting in higher incomes and a positive effect on mental health (Thomson et al., 2022). This effect is especially profound in displacement settings; a loss of jobs since the outbreak of COVID-19 has been reported as a main cause of suicide in the Yazidi community (van Wilgenburg, 2021).

However, true empowerment of survivors begins with acknowledgement of their own perceptions and priorities, which may be different from what is expected by the outside world (Akhavan et al., 2020). Responding to the mental health needs of female Yazidis requires a greater understanding of their day-to-day experiences.

Strengths and limitations

The findings of this review are from a multitude of studies, in a diverse range of low-resource settings. Utilisation of grey literature and peer-reviewed literature resulted in a large pool of data within which to build the CIMO configuration.

However, records included interventions delivered to both males and females, thus limiting the applicability of findings solely to female Yazidis. The purposive sampling strategy does not require an exhaustive search of databases, exposing the potential to partial or incomplete results (Pawson et al., 2005; Kiss et al., 2020). Only a small number of Western mental health terms were used in searches. Despite PTSD, according to DSM-V criteria, being identified as a valid measure amongst IDPs living in Iraqi Kurdistan (Ibrahim et al., 2018), the dominant use of DSM-PTSD diagnoses as an entry criteria in review contexts where it has not been approved excludes those who do not meet Western standards of mental illness (Patel et al., 2014). The search may have missed records with titles and abstracts in languages other than English (Spangaro et al., 2013).

Interviews were based upon one-time consultations with a small sample. Questions may therefore elicit a different response at a later date. Although the study was designed to explicitly recognise the perspectives and contributions of service providers, we did not provide an opportunity for interviewees to offer their feedback on the interpretation of findings.

Conclusion

We explored how global evidence on psychosocial interventions delivered to female survivors of CRSV applies to the internally displaced female Yazidi population. Seven mechanisms underpin psychosocial interventions delivered to displaced female survivors of CRSV: safe spaces, a strong therapeutic relationship, social connection, mental health literacy, cultural competency, gender-matching and empowerment.

Realist semi-structured interviews confirmed relevance of mechanisms to female Yazidi IDPs in the KRI. Interviews highlighted the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of this population. Increased flashbacks, regressed treatment progress and increased fear were documented. Closure of safe spaces, isolation from social networks, redistribution of resources, disruptions to in-person interventions, loss of livelihoods and increased rates of IPV have contributed to Yazidis' suffering.

COVID-19 is just one challenge affecting the implementation and delivery of interventions. Gendered and legal inequalities, fractured governance and war damage are just some. Future research should focus on understanding the daily experiences of female Yazidi IDPs, and would benefit from large-sample quantitative analysis of mental health scores pre- and post-pandemic. Research should also investigate which interactions of mechanisms are most effective for this population.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.55.

click here to view supplementary material

Data

Not applicable to support anonymisation of interview data.

Authors' contributions

SLR was involved in the conception of the project, led the searching and screening of articles, interviews with stakeholders, data analysis and drafted the initial and final manuscript. LK provided direction on conduct of realist reviews, resolved decisions about inclusion criteria, data analysis, was closely involved in theorising and analysis and contributed to the final paper.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was acquired from the UCL Research Ethics Committee with approval granted on 04/08/2020 [project ID/title: 18701.001].

Consent for publication

Consent was obtained from each stakeholder prior to interview using UCL's institutional consent form.

References

- Abdulah DM and Abdulla BMO (2020) Suicidal ideation and attempts following a short-term period of art-based intervention: an experimental investigation. The Arts in Psychotherapy 68, 101648. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams R, Park S, Wong G, Rastogi J, Boylan AM, Tierney S, Petrova M, Dawson S and Roberts N (2021) Lost in reviews: looking for the involvement of stakeholders, patients, public and other non-researcher contributors in realist reviews. Research Synthesis Methods 12, 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acarturk C, Konuk E, Cetinkaya M, Senay I, Sijbrandij M, Gulen B and Cuijpers P (2016) The efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among Syrian refugees: results of a randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine 46, 2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahram AI (2019) Sexual violence, competitive state building, and Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 13, 180–196. [Google Scholar]

- Akhavan P, Ashraph S, Barzani B and Matyas D (2020) What justice for the Yazidi genocide? Voices from below. Human Rights Quarterly 42, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khalisi N (2013) The Iraqi medical brain drain: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Health Services 43, 363–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atulomah NO, Dangana JM, Olanrewaju MF and Oritogun KS (2020) Effectiveness of motivational counselling on post-traumatic stress disorder symptom-reduction among internally displaced elderly persons in Borno State Nigeria. The Nigerian Health Journal 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bass J, Murray SM, Mohammed TA, Bunn M, Gorman W, Ahmed AMA, Murray L and Bolton P (2016) A randomized controlled trial of a trauma-informed support, skills, and psychoeducation intervention for survivors of torture and related trauma in Kurdistan, Northern Iraq. Global Health: Science and Practice 4, 452–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Bass J, Betancourt T, Speelman L, Onyango G, Clougherty KF, Neugebauer R, Murray L and Verdeli H (2007) Interventions for depression symptoms among adolescent survivors of war and displacement in northern Uganda: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association 298, 519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Wright J and Briscoe S (2018) Scoping and searching to support realist approaches. Doing realist research. London: Sage, 147–166. [Google Scholar]

- Bosqui TJ and Marshoud B (2018) Mechanisms of change for interventions aimed at improving the wellbeing, mental health and resilience of children and adolescents affected by war and armed conflict: a systematic review of reviews. Conflict and Health 12, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V and Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bunn F, Goodman C, Malone JR, Jones PR, Burton C, Rait G, Trivedi D, Bayer A and Sinclair A (2016) Managing diabetes in people with dementia: protocol for a realist review. Systematic Reviews 5, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani C, Kohiladevy M, Ruf M, Schauer E, Elbert T and Neuner F (2009) Treating children traumatized by war and Tsunami: a comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry 9, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetorelli V, Burnham G and Shabila N (2017a) Health needs and care seeking behaviours of Yazidis and other minority groups displaced by ISIS into the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. PLoS ONE 12, e0181028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetorelli V, Sasson I, Shabila N and Burnham G (2017b) Mortality and kidnapping estimates for the Yazidi population in the area of Mount Sinjar, Iraq, in August 2014: a retrospective household survey. PLoS Medicine 14, e1002297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H and Saxena S (2019) New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet 394, 240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen LR and Han H (2002) Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: a phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 70, 1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalkin SM, Greenhalgh J, Jones D, Cunningham B and Lhussier M (2015) What’s in a mechanism? Development of a key concept in realist evaluation. Implementation science 10, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza DE (2013) Elaborating the context-mechanism-outcome configuration (CMOc) in realist evaluation: a critical realist perspective. Evaluation 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dulz I (2016) The displacement of the Yezidis after the rise of ISIS in Northern Iraq. Kurdish Studies 4, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Dybdahl R (2001) Children and mothers in war: an outcome study of a psychosocial intervention program. Child Development 72, 1214–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdener E (2017) The ways of coping with post-war trauma of Yezidi refugee women in Turkey. Women's Studies International Forum 65, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Freij N (2018) Creating Job Opportunities for Young Adults in Kurdistan. Zakho district, Dohuk Governorate, Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI): Action Against Hunger. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Merchant RM and Lurie N (2020) The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine 180, 817–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Network on Extremism & Technology (2020) Jihadists see COVID-19 as an opportunity [Online]. Available at https://gnet-research.org/2020/06/01/jihadists-see-covid-19-as-an-opportunity/ [Accessed 1st September 2020].

- Goessmann K, Ibrahim H and Neuner F (2020) Association of war-related and gender-based violence with mental health states of Yazidi women. JAMA Network Open 3, e2013418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Bergbower H, Perrotte V and Chaudhary A (2020) Survival after sexual violence and genocide: trauma and healing for Yazidi women in Northern Iraq. Health 12, 612–628. [Google Scholar]

- Guterres A (2019) Conflict related sexual violence: report of the United Nations secretary-general [Online]. Available at https://www.un.org/sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/report/s-2019-280/Annual-report-2018.pdf [Accessed 17th August 2022].

- Heise LL (1998) Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women 4, 262–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman YS, Grossman ES, Shrira A, Kedar M, Ben-Ezra M, Dinnayi M, Koren L, Bayan R, Palgi Y and Zivotofsky AZ (2018) Complex PTSD and its correlates amongst female Yazidi victims of sexual slavery living in post-ISIS camps. World Psychiatry 17, 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M, Pearson RJ, McAlpine A, Bacchus LJ, Spangaro J, Muthuri S, Muuo S, Franchi G, Hess T and Bangha M (2021) Gender-based violence and its association with mental health among Somali women in a Kenyan refugee camp: a latent class analysis. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 75, 327–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein NR, Naqid IA, Saleem ZSM, Almizori LA, Musa DH and Ibrahim N (2020) A sharp increase in the number of COVID-19 cases and case fatality rates after lifting the lockdown in Kurdistan region of Iraq. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 57, 140–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IASC (2020) Guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings [online]. Available at https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-task-force-mental-health-and-psychosocial-support-emergency-settings/iasc-guidelines-mental-health-and-psychosocial-support-emergency-settings-2007 [Accessed 1st September 2020].

- Ibrahim H, Ertl V, Catani C, Ismail AA and Neuner F (2018) The validity of posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) as screening instrument with Kurdish and Arab displaced populations living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. BMC Psychiatry 18, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration (2011) Increased Incidents of Suicide Among Yazidis in Sinjar, Ninewa. IOM-Iraq Special Report.

- Isakhan B and Shahab S (2020) The Islamic State's destruction of Yezidi heritage: responses, resilience and reconstruction after genocide. Journal of Social Archaeology 20, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jaff D (2018) Yazidi women: healing the invisible wounds. Global Health: Science and Practice 6, 223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger P (2019) Stress and health of internally displaced female Yezidis in Northern Iraq. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 21, 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiyan Foundation for Human Rights (2017) Annual Report. Erbil, Kurdistan.

- Kanyangara P, Rimé B, Philippot P and Yzerbyt V (2007) Collective rituals, emotional climate and intergroup perception: participation in ‘Gacaca’ tribunals and assimilation of the Rwandan genocide. Journal of Social Issues 63, 387–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya ZN and Luchtenberg KN (2018) Displacement and women's economic empowerment: voices of displaced women in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. In Economics LSO (ed.), London: Women for Women International, London, 3–36.

- Keller SM, Zoellner LA and Feeny NC (2010) Understanding factors associated with early therapeutic alliance in PTSD treatment: adherence, childhood sexual abuse history, and social support. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 78, 974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JT, Betancourt TS, Mukwege D, Lipton R and Vanrooyen MJ (2011) Experiences of female survivors of sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo: a mixed-methods study. Conflict and Health 5, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss L, Quinlan-Davidson M, Pasquero L, Tejero PO, Hogg C, Theis J, Park A, Zimmerman C and Hossain M (2020) Male and LGBT survivors of sexual violence in conflict situations: a realist review of health interventions in low-and middle-income countries. Conflict and Health 14, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizilhan JI and Noll-Hussong M (2020) The psychological impact of COVID-19 in a refugee camp in Iraq. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 74, 659–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster SL and Gaede C (2020) A test of a resilience based intervention for mental health problems in Iraqi internally displaced person camps. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 33, 696–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood KI, Shabu SA, M-Amen KM, Hussain SS, Kako DA, Hinchliff S and Shabila NP (2021) The impact of COVID-19 related lockdown on the prevalence of spousal violence against women in Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37, NP11811–NP11835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicins Sans Frontieres (2019) MSF warns of mental health crisis among Yazidis in Iraq [online]. Available at https://www.msf.org/msf-warns-mental-health-crisis-among-yazidis-iraq Accessed 1st June 2020.

- Millar O and Warwick I (2019) Music and refugees’ wellbeing in contexts of protracted displacement. Health Education Journal 78, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mogre V, Scherpbier A, Dornan T, Stevens F, Aryee PA and Cherry MG (2014) A realist review of educational interventions to improve the delivery of nutrition care by doctors and future doctors. Systematic Reviews 3, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi D (2016) Help for Yazidi survivors of sexual violence. The Lancet Psychiatry 3, 409–410. [Google Scholar]

- Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Okello J, Kinyanda E, Alderman S, Nakku J, Alderman JS, Pavia A, Adaku A, Allden K and Musisi S (2013) The impact of group counseling on depression, post-traumatic stress and function outcomes: a prospective comparison study in the Peter C. Alderman trauma clinics in northern Uganda. Journal of Affective Disorders 151, 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan P, McMullen J, Shannon C, Rafferty H and Black A (2013) A randomized controlled trial of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for sexually exploited, war-affected Congolese girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 52, 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omarkhali K (2016) Transformations in the Yezidi tradition after the ISIS attacks. An interview with Ilhan Kizilhan. Kurdish Studies 4, 148–154. [Google Scholar]

- Othman N (2020) Depression, anxiety, and stress in the time of COVID-19 pandemic in Kurdistan region, Iraq. Kurdistan Journal of Applied Research, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Patel N, Kellezi B and de Williams ACC (2014) Psychological, social and welfare interventions for psychological health and well-being of torture survivors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11, CD009317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G and Walshe K (2005) Realist review-a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10, 21–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persecution Prevention Project (2019) Before It's Too Late – A Report Concerning the Ongoing Genocide and Persecution Endured by the Yazidis in Iraq, and Their Need for Immediate Protection. Yale Macmillan Center Genocide Studies Program: Yale University.

- Radez J, Reardon T, Creswell C, Lawrence PJ, Evdoka-Burton G and Waite P (2021) Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 30, 183–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richa S, Herdane M, Dwaf A, Bou Khalil R, Haddad F, El Khoury R, Zarzour M, Kassab A, Dagher R and Brunet A (2020) Trauma exposure and PTSD prevalence among Yazidi, Christian and Muslim asylum seekers and refugees displaced to Iraqi Kurdistan. PLoS ONE 15, e0233681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röhr S, Müller F, Jung F, Apfelbacher C, Seidler A and Riedel-Heller SG (2020) Psychosocial impact of quarantine measures during serious coronavirus outbreaks: a rapid review. Psychiatrische Praxis 47, 179–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal S, Elbert T and Neuner F (2009) Narrative exposure therapy versus interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 78, 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Conrad D, Pfeiffer A, Elbert T, Kolassa I-T and Wilker S (2018) Stigmatization is associated with increased PTSD risk after traumatic stress and diminished likelihood of spontaneous remission – a study with East-African conflict survivors. Frontiers in Psychiatry 9, 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidi P and Jaff D (2019) Mental health in conflict settings. The Lancet 394, 2237–2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidi PA, Jaff D, Connolly SM and Hoffart A (2020) Applying cognitive behavioral therapy and thought field therapy in Kurdistan region of Iraq: a retrospective case series study of mental-health interventions in a setting of political instability and armed conflicts. Explore 17, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishehgar S, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, Green A and Davidson PM (2017) Health and socio-cultural experiences of refugee women: an integrative review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 19, 959–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Six-Hohenbalken M (2019) May I be a sacrifice for my grandchildren – transgenerational transmission and women's narratives of the Yezidi ferman. Dialectical Anthropology 43, 161–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonderegger R, Rombouts S, Ocen B and McKeever RS (2011) Trauma rehabilitation for war-affected persons in northern Uganda: a pilot evaluation of the EMPOWER programme. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 50, 234–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangaro J, Adogu C, Ranmuthugala G, Powell Davies G, Steinacker L and Zwi A (2013) What evidence exists for initiatives to reduce risk and incidence of sexual violence in armed conflict and other humanitarian crises? A systematic review. PloS one 8, e62600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangaro J, Adogu C, Zwi AB, Ranmuthugala G and Davies GP (2015) Mechanisms underpinning interventions to reduce sexual violence in armed conflict: A realist-informed systematic review. Conflict and health 9, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang A, O'Brien O, Sandilands M and Horn R (2020) Help-seeking, trust and intimate partner violence: social connections amongst displaced and non-displaced Yezidi women and men in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq. Conflict and Health 14, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Kurdish Project. Kurdistan oil: the past, present and future [online]. Available at https://thekurdishproject.org/kurdistan-news/kurdistan-oil/ Accessed 18 June 2021.

- The Lotus Flower (2017) Annual Report. Kurdistan.

- The World Bank Group (2019) Women, Business and the Law 2019: A Decade of Reform. Washington: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson RM, Igelström E, Purba AK, Shimonovich M, Thomson H, McCartney G, Reeves A, Leyland A, Pearce A and Katikireddi SV (2022) How do income changes impact on mental health and wellbeing for working-age adults? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health 7, e515–e528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tol WA, Stavrou V, Greene MC, Mergenthaler C, Van Ommeren M and García Moreno C (2013) Sexual and gender-based violence in areas of armed conflict: a systematic review of mental health and psychosocial support interventions. Conflict and Health 7, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickey H, Thomson G, Grant A, Sanders J, Mann M, Murphy S and Paranjothy S (2018) A realist review of one-to-one breastfeeding peer support experiments conducted in developed country settings. Maternal & Child Nutrition 14, e12559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR (2019) COI note on the situation of Yazidi IDPs in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. In Unhcr (ed.) 1–11.

- United Nations (2017) Report of the Secretary-General on Conflict-Related Sexual Violence.

- UNMAS (2019) The Dutch Government Reiterates its Support to Explosive Hazard Management Activities in Iraq.

- van Westrhenen N, Fritz E, Oosthuizen H, Lemont S, Vermeer A and Kleber RJ (2017) Creative arts in psychotherapy treatment protocol for children after trauma. The Arts in Psychotherapy 54, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- van Wilgenburg W (2021) Hopelessness, continued displacement lead to spike in suicides among Yezidis: KRG [online]. Available at https://www.kurdistan24.net/en/story/23999-Hopelessness,-continued-displacement-lead-to-spike-in-suicides-among-Yezidis:-KRG Accessed 1st June 2021.

- Ventevogel P, Ommeren M, Schilperoord M and Saxena S (2015) Improving mental health care in humanitarian emergencies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 93, 666–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J and Marsh M (2006) Sexual violence against women and girls in war and its aftermath: realities, responses and required resources. Symposium on Sexual Violence in Conflict and Beyond.

- Womersley G and Arikut-Treece Y (2019) Collective trauma among displaced populations in Northern Iraq: a case study evaluating the therapeutic interventions of the Free Yezidi Foundation. Intervention 17, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, Greenhalgh J, Jagosh J and Greenhalgh T (2016) RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Medicine 14, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood EJ (2014) Conflict-related sexual violence and the policy implications of recent research. International Review of the Red Cross 96, 457–478. [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans PD, Forman EM, Herbert JD and Yuen E (2010) A randomized trial of a reconciliation workshop with and without PTSD psychoeducation in Burundian sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress 23, 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W and Lu R (2020) A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New England Journal of Medicine 382, 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.55.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable to support anonymisation of interview data.