Abstract

Background

Studies have identified high rates of mental disorders in refugees, but most used self-report measures of psychiatric symptoms. In this study, we examined the percentages of adult refugees and asylum seekers meeting diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD), post-traumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder (BPD), and psychosis.

Methods

A systematic literature search in three databases was conducted. We included studies examining the prevalence of MDD, post-traumatic stress disorder, BPD, and psychosis in adult refugees according to a clinical diagnosis. To estimate the pooled prevalence rates, we performed a meta-analysis using the Meta-prop package in Stata (PROSPERO: CRD42018111778).

Results

We identified 7048 records and 40 studies (11 053 participants) were included. The estimated pooled prevalence rates were 32% (95% CI 26–39%; I2 = 99%) for MDD, 31% (95% CI 25–38%; I2 = 99.5%) for post-traumatic stress disorder, 5% (95% CI 2–9%; I2 = 97.7%) for BPD, and 1% (95% CI 1–2%; I2 = 0.00%) for psychosis. Subgroup analyses showed significantly higher prevalence rates of MDD in studies conducted in low-middle income countries (47%; 95% CI 38–57%, p = 0.001) than high-income countries studies (28%; 95% CI 22–33%), and in studies which used the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (37%; 95% CI 28–46% p = 0.05) compared to other diagnostic interviews (26%; 95% CI 20–33%). Studies among convenience samples reported significant (p = 0.001) higher prevalence rates of MDD (35%; 95% CI 23–46%) and PTSD (34%; 95% CI 22–47%) than studies among probability-based samples (MDD: 30%; 95% CI 21–39%; PTSD: 28%; 95% 19–37%).

Conclusions

This meta-analysis has shown a markedly high prevalence of mental disorders among refugees. Our results underline the devastating effects of war and violence, and the necessity to provide mental health intervention to address mental disorders among refugees. The results should be cautiously interpreted due to the high heterogeneity.

Key words: Mental disorders, meta-analysis, prevalence, refugees

Introduction

During the past decade, the trend of global displacement has been growing (UNHCR, 2020). In 2020, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR) estimated that more than 11 million people have been displaced throughout the year, and the proportion of this population has been continued to rise, despite the COVID-19 pandemic and closure of borders (UNHCR, 2020). Although refugees (people who, owing to a well-founded fear of persecution, are forced to escape from his or her country) and asylum seekers (people seeking protection from persecution or serious harm in a country other than their own) are defined in different ways (UNHCR, 2020), both groups may have been forced to face various stressors, such as persecution, violence, torture, detention, and the loss of homes and livelihoods. Such traumatic events may result in persistent mental health problems and overall decreased functioning (Steel et al., 2009; Marquez, 2016).

During the last years, several studies have examined the prevalence of mental disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. However, the resulting prevalence rates in this population present great variability (Fazel et al., 2005; Porter and Haslam, 2005; Bogic et al., 2015; Foo et al., 2018; Morina et al., 2018; Charlson et al., 2019; Blackmore et al., 2020), ranging from 5% (Fazel et al., 2005) to 80% (Bogic et al., 2015) for depression, from 4% (Charlson et al., 2019) to 88% (Morina et al., 2018) for PTSD, and from 1.5% (Blackmore et al., 2020) to 2% (Fazel et al., 2005) for psychosis. A systematic review on the prevalence of serious mental disorders in refugees resettled in high-income western countries reported weighted average rates of 5% for major depressive disorder (MDD), 9% for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 2% for psychotic disorders (Fazel et al., 2005). A meta-analysis among refugees and asylum seekers residing outside their country of origin reported a prevalence of 31.5% for PTSD, of 31.5% for depression, and 1.5% for psychosis (Blackmore et al., 2020). Another meta-analysis that examined the prevalence of mental disorders in conflict settings showed estimated rates of 22.1% for any mental disorder (13% for depression and 4% for PTSD) (Charlson et al., 2019). The variability across studies could be explained by differences in the origins and background of the analysed populations, the sample size, the sampling methods, and the diagnostic tools used (e.g. self-report, semi-structured or structured clinical interview) (Westermeyer and Janca, 1997; de Jong et al., 2003; Fazel et al., 2005; Bogic et al., 2015; Giacco et al., 2018; Giacco and Priebe, 2018; Charlson et al., 2019). Furthermore, the nature of the displacement, the context of the emergency, as well as the aspects of the host country/environment are additional aspects to consider in the variability of these studies (Giacco and Priebe, 2018).

Many epidemiological studies use self-report instruments to estimate the prevalence of mental disorders in refugees because they are easily administered and cost effective. However, such instruments overestimate prevalence rates considerably (Domken et al., 1994; Fazel et al., 2005; Steel et al., 2009). In fact, self-report instruments have been shown to overestimate true PTSD-rates by a factor of about 3.5 (Engelhard et al., 2007). Similar results have been also shown in depression studies (Domken et al., 1994; Steel et al., 2009; Krebber et al., 2014). One of the reasons is that many self-report instruments are designed for quickly picking-up mental disorders while minimising false negatives, therefore cut-offs are set with high sensitivity. Therefore, they identify more patients who may have a mental disorder than those diagnosed with clinician-administered interviews (Thombs et al., 2018). Another reason could be that self-report tools usually do not take functional impairment due to symptoms into account (McKnight and Kashdan, 2009). Besides, translations of existing self-report instruments may not adequately measure psychiatric symptoms across cultures (Hunt and Bhopal, 2004). Finally, overestimation may occur as a consequence of the so-called over-endorsement bias, the tendency of respondents to generously claim different types of symptoms on a checklist (Kroenke, 2001). Thus, more rigorous instruments, such as clinical diagnostic interviews, are more appropriate to estimate the prevalence of mental health disorders in refugees and asylum seekers (Fazel et al., 2005; Steel et al., 2009). In addition, clinicians' experience in using structured interviews can increase the reliability of symptoms measurement and psychiatric diagnoses even among samples with different cultural backgrounds (Alarcon et al., 1999; Aboraya et al., 2006). Nevertheless, among the structured and semi-structured interviews there may also be some differences in accuracy. For example, studies have shown that the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview – MINI, which has been designed as a briefer and quicker diagnostic screen than other interviews (Sheehan et al., 1997) identified more people as depressed than the Composite International Diagnostic Interview – CIDI, and the Structured Clinical Interview – SCID (Levis et al., 2018; Levis et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2021).

In the present study, we aimed to estimate the prevalence of diagnoses of serious mental disorders [MDD, PTSD, bipolar disorder (BPD), and psychosis] in refugees and asylum seekers from conflict-affected areas. Serious mental disorders are conditions resulting in serious functional impairment, which interferes with major life activities (NIH, 2019). Other definitions (Slade et al., 1997) take into account the duration and the disability they produce, for example in terms of the disability they are associated with. Within the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, the top-three mental disorders associated with the highest level of disability are MDD, BPD and psychosis (Kronenberg et al., 2017; James et al., 2018). Although not included in the GBD, PTSD is particularly relevant for refugees and asylum seekers since refugees may be exposed to multiple traumatic events, including interpersonal violence that may cause severe disability (Palic et al., 2016).

Similar to previous studies (Fazel et al., 2005; Blackmore et al., 2020), we included only studies that employed diagnostic interviews. Further, our study differs from previous studies in that we were able to include a larger number of studies than before since the number of studies increased during the past years. In addition, we were able to examine the prevalence of less common disorders such as BPD. Finally, due to the increased number of included studies, we could perform additional subgroup analyses, such as comparing the prevalence of serious mental disorders between refugees resettled in low-middle-income v. high-income countries, and among different kind of population sample (convenience samples v. probability-based samples).

Method

Search strategy and selection criteria

We report our meta-analysis according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (www.prisma-statement.org) (Moher et al., 2009) (see online Supplementary materials).

The present study was registered in PROSPERO on 5th December 2018 under the number: CRD42018111778.

A comprehensive search was performed in the bibliographic databases PubMed, Embase.com and APA PsycInfo (via Ebsco) from inception to June 4, 2020, by a medical librarian. Search terms included controlled terms (MeSH in PubMed, Emtree in Embase and PsycINFO thesaurus terms) as well as free text terms. The following terms were used (including synonyms and closely related words) as index terms or free-text words: ‘refugees’ and ‘mental illnesses’. A search filter was used to limit the results to adults. The search was performed without date or language restrictions. Duplicate articles were excluded. The full search strategies for all databases can be found in the online Supplementary materials.

Studies were considered eligible for this meta-analysis if they examined (a) the prevalence of serious mental disorders (MDD, PTSD, BPD, and psychosis), (b) in an adult (⩾18 years) population of refugees and asylum seekers who had to cross their country borders, (c) according to the criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM III, IV, or 5) or International Classification of Diseases (ICD 9 or10) (d) assessed with a structured or semi-structured clinical interview, such as the Structured Clinical Interview – SCID, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview – MINI, or Composite International Diagnostic Interview – CIDI. No cut-off has been considered to evaluate the diagnosis' severity. Disorders have been evaluated serious according with the National Institute of Mental Health (NIH) and GBD considerations (Kronenberg et al., 2017; James et al., 2018; NIH, 2019).

The definitions of refugees (a person who, owing to a well-founded fear of persecution, is forced to escape from his or her country) and asylum seekers (a person who seeks protection from persecution or serious harm in a country other than their own) were in agreement with the UNHCR Master Glossary of Terms (UNHCR, 2006) and Asylum and Migration Glossary 6.0 (Network, 2018). No restrictions were applied to the origin of the studies. Cross-sectional studies, follow-up studies, cohort data studies and register-based studies were eligible. To reduce possible selection bias, we excluded studies conducted on samples selected in psychiatric services and concerning internally displaced people (IDPs) (UNHCR, 2006).

All title and abstracts were screened by two researchers independently (MP/MS or SG). We retrieved the full texts of all abstracts that seemed eligible for inclusion. Subsequently, we performed a full-text selection according to our pre-specified eligibility criteria. Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

For every eligible study, two reviewers independently (MP/MS or SG) extracted data related to the year of publication, the country of data collection, the country of the refugees' origins, the sample size of the population, the age, the gender, the time elapsed as refugees or asylum seekers, the diagnostic tool used. Finally, we extracted the prevalence rates of MDD (current episode and recurrent), PTSD, BPD and psychotic disorder. In the absence of absolute numbers and if allowed by the data reported, the percentages of prevalence rates were converted into numbers. The time since displacement was reported in three different categories: (1) people who have spent more than five years as refugees or asylum seekers (⩾5), (2) people who have spent between 5 years and 1 year as refugees or asylum seekers (>1 < 5) and (3) people who have spent less then 1 year as refugees or asylum seekers. Countries were categorised as low-, middle- (LMIC) and in high-income (HIC) based on the World Bank list of economies 2020 (WBC, 2020).

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (MP/MS or SG) evaluated the assessment of the methodological quality of individual studies using a modified version of the Joanna Briggs tool – JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data (Munn et al., 2015) based on five questions, which permitted a critical assessment of prevalence rates: (1) Were study participants recruited in an appropriate way? (2) Was the sample size adequate? (3) Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? (4) Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants? (5) Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately?. The response categories per each question were yes, unclear, and no. Three or more unclear or negative answers were considered to define a study with a high risk of bias (see online Supplementary materials). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by involving a third reviewer (PC).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

The prevalence rates of serious mental disorders were calculated by pooling the study-specific estimates. To stabilise the variance of binomial data, the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation was used (Miller, 1978). Because we expected considerable heterogeneity between studies, we computed the pooled estimates under the random effects (DerSimonian and Laird) model based on the transformed values and their variance (Nyaga et al., 2014). The I2 was calculated as an indicator of the inter-study heterogeneity in percentages. Values of I2 are considered low, moderate and high when I2 equals 25, 50, and 75% respectively (Melsen et al., 2014). Based on previous meta-analyses on prevalence rates, we expected considerable heterogeneity in the prevalence estimates (Higgins, 2008; Charlson et al., 2019; Blackmore et al., 2020). To examine possible sources of heterogeneity between the included studies, we ran subgroups under the mixed-effects model with inverse-variance weights under the random-effects model (time since displacement ⩾ 5 years v. time since displacement >1 < 5years v. time since displacement <1year, MINI v. other diagnostic interviews, LMICs v. HICs, high risk of bias v. low risk of bias, convenience samples v. probability-based samples). Prevalence rates were calculated per each disorder separately. Pooled rates for subgroups were indicated, when at least three studies were present for each disorder. All statistical analyses were conducted using Meta-prop package in STATA/SE 16.1 for Mac (Nyaga et al., 2014).

Results

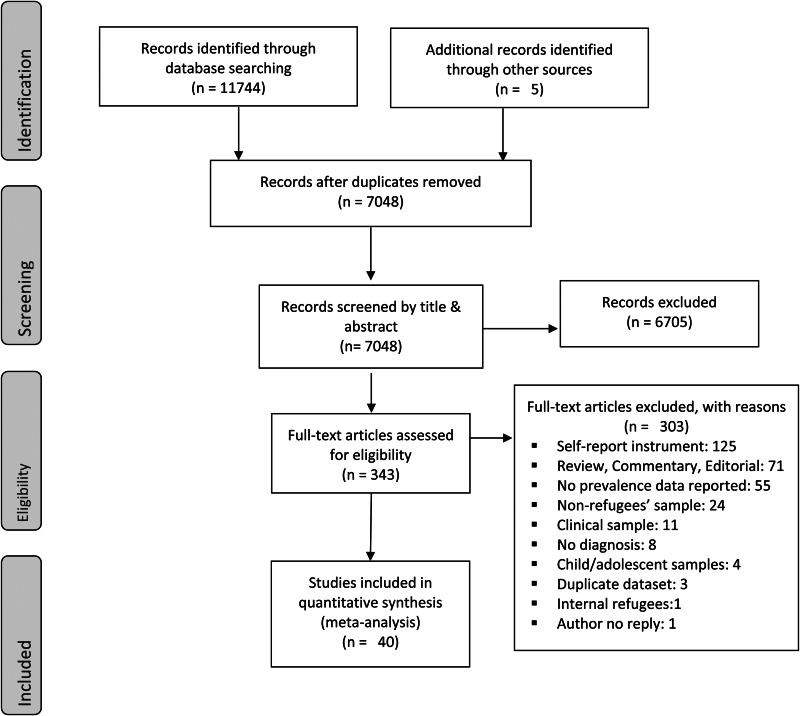

We initially identified 11 749 records. After exclusion of duplicates, 7048 records remained. We excluded 6705 studies based on titles and abstracts selection. We examined 343 full texts against our eligibility criteria and included 40 studies in the present meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study identification, screening, and eligibility test, following the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews (PRISMA).

Studies included were conducted across 18 countries, 7 LMICs (Van Ommeren et al., 2001a; Akinyemi et al., 2012; Llosa et al., 2014; Naja et al., 2016; Tekin et al., 2016; Kazour et al., 2017; Segal et al., 2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., 2018; Ainamani et al., 2020; Bapolisi et al., 2020; Civan Kahve et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020; Sagaltici et al., 2020) (Lebanon, Malaysia, Nepal, Nigeria, Turkey, Syria and Uganda) and 11 HICs (Hinton et al., 1993; Cheung, 1994; Steel et al., 2002; Turner et al., 2003; Fenta et al., 2004; Laban et al., 2004; Momartin et al., 2004; Marshall et al., 2005; Bhui et al., 2006; Renner et al., 2006; Von Lersner et al., 2008; Maier et al., 2010; Eckart et al., 2011; Jakobsen et al., 2011; Bogic et al., 2012; Heeren et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2012; Tay et al., 2013; Hocking et al., 2015; 2018; Wright et al., 2017; Kizilhan, 2018; Nose et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2018; Rees et al., 2019; Wulfes et al., 2019; Sundvall et al., 2020) (Australia, Austria, Canada, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, The Netherlands, United Kingdom and United States of America) and they reported the prevalence of mental disorders of 11 053 participants (5309 men – 48%). Of these 11 053 participants, 6897 (62.3%) had taken part in population-based representative surveys (PBR). The majority of the studies included have used MINI as diagnostic interview (Bhui et al., 2006; Von Lersner et al., 2008; Maier et al., 2010; Akinyemi et al., 2012; Bogic et al., 2012; Heeren et al., 2012; Llosa et al., 2014; Hocking et al., 2015, 2018; Naja et al., 2016; Kazour et al., 2017; Nose et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2018; Segal et al., 2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., 2018; Rees et al., 2019; Bapolisi et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020; Sundvall et al., 2020). CIDI was used by 7 studies (Van Ommeren et al., 2001a; Steel et al., 2002; Fenta et al., 2004; Laban et al., 2004; Marshall et al., 2005; Jakobsen et al., 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2012), SCID by six studies (Hinton et al., 1993; Tay et al., 2013; Tekin et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2017; Kizilhan, 2018; Wulfes et al., 2019) and one study (Cheung, 1994) used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule – DIS. The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale – CAPS and the PTSD Symptom Scale–Interview- PSS-I were used by six studies (Turner et al., 2003; Momartin et al., 2004; Renner et al., 2006; Eckart et al., 2011; Civan Kahve et al., 2020; Sagaltici et al., 2020) and one study (Ainamani et al., 2020) respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies meeting inclusion criteria

| Study | Country of study | Country category | Population | Sample size, n | PBR | Age, n – M (s.d.) | Gender, n | Time since displacement (years) | Questionnaire | MDD, n | MDD Recurrent ep, n | PTSD,n | Bipolar disorders, n | Pychotic disorders, n (%) | RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ainamani et al. (2020) | Uganda | LMIC | Congolese | 325 | No | M 31.9 F 30.9 |

M 143 F 182 |

NR | PSS-I | NR | NR | 285/325 | NR | NR | High |

| Akinyemi et al. (2012) | Nigeria | LMIC | Liberian, Sierra Leonean, Togolese | 444 | Yes | 34.8 (±12.8) | M 263 F 181 |

⩾5 | MINI | 201/444 | NR | 150/444 | 114/444 | NR | Low |

| Bapolisi et al. (2020) | Uganda | LMIC | Congolese, Burundian, Somali, Rwandese, Ethiopian, Eritrean, Sudanese | 387 | Yes | 33.01 (±12.2) | M 168 F 219 |

>1 < 5 | MINI | 226/387 | NR | 260/387 | NR | NR | Low |

| Bhui et al. (2006) | UK | HIC | Somali | 143 | No | ⩾18 | M 71 F 72 |

<1 | MINI | 38/143 | 13/143 | 20/143 | 0/143 | 1/143 | Low |

| Bogic et al. (2012) | Germany, Italy and UK | HIC | Former Yugoslavia | 854 | Yes | 41.6 (±10.8) | M 416 F 438 |

⩾5 | MINI | 292/851 | 132/846 | 282/854 | 16/850 | 11/854 | High |

| Cheung (1994) | New Zealand | HIC | Cambodian | 223 | Yes | ⩾18 | M 104 F 119 |

>1 < 5 | DIS | NR | NR | 27/223 | NR | NR | Low |

| Civan Kahve et al. (2020) | Turkey | LMIC | Iraqi | 101 | No | M 49 F 52 |

>1 < 5 | CAPS | NR | NR | 9/101 | NR | NR | Low | |

| Eckart et al. (2011) | Germany | HIC | Albanian, Kurdish, Romanian, Serbian, Turkish | 52 | No | ⩾18 | M 52 F 0 |

NR | CAPS MINI |

17/52 | NR | 20/52 | NR | NR | High |

| Fenta et al. (2004) | Canada | HIC | Ethiopian | 325 | No | 35.3 (±7.2) | M 203 F 139 |

⩾5 | CIDI | 20/325 | 33/342 | NR | NR | NR | High |

| Heeren et al. (2012) | Switzerland | HIC | African, Asian, European | 86 | No | NR | M 60 F 26 |

NR | MINI | 27/86 | NR | 20/86 | NR | NR | High |

| Hinton et al. (1993) | USA | HIC | Vietnamese, Chinese | 201 | NR | 33.2 (±12.0) | M 96 F 105 |

<1 | SCID | 11/201 | NR | 7/201 | NR | NR | High |

| Hocking et al. (2015) | Australia | HIC | Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Zimbabwe, Iraqi, Afghan, Iranian, Lebanon | 98 | No | 34.6 (±10.6) | M 87 F 11 |

NR | MINI | 58/95 | NR | 49/94 | NR | NR | High |

| Hocking et al. (2018) | Australia | HIC | Asia | 185 | NR | ⩾18 | M 129 F 56 |

>1 < 5 | MINI | 56/185 | NR | NR | NR | NR | High |

| Jakobsen et al. (2011) | Norway | HIC | Middle East, North African, Somali, Former Yugoslavia | 64 | No | 33 (±11.6) | M 34 F 30 |

>1 < 5 | CIDI | 21/64 | NR | 29/64 | NR | NR | Low |

| Kaur et al. (2020) | Malaysia | LMIC | Rohingya | 220 | Yes | 33.5 | M 116 F 104 |

>1 < 5 | MINI | 71/220 | NR | 84/220 | NR | NR | Low |

| Kazour et al. (2017) | Lebanon | LMIC | Syrian | 452 | No | 35.05 (±12.3) | M 200 F 252 |

<1 | MINI | NR | NR | 123/452 | NR | NR | High |

| Kizilhan (2018) | Germany | HIC | Yazidi | 296 | No | 23.72 (±2.62) | F 296 | >1 < 5 | SCID | 158/296 | NR | 144/296 | NR | NR | High |

| Laban et al. (2004) | The Netherlands | HIC | Iraqi | 294 | Yes | ⩾18 | M 190 F 104 |

>1 < 5 | CIDI | 85/294 | 13/294 | 108/294 | NR | NR | Low |

| Llosa et al. (2014) | Lebanon | LMIC | Palestinian | 194 | Yes | 41.5 (±15.1) | M 56 F 138 |

NR | MINI | 31/194 | 48/194 | 9/194 | 3/194 | 5/194 | Low |

| Maier et al. (2010) | Switzerland | HIC | Asian, African, European | 78 | No | 29.9 (± 8.4) | M 57 F 21 |

>1 < 5 | MINI | 26/78 | NR | 19/78 | NR | NR | High |

| Marshall et al. (2005) | USA | HIC | Cambodian | 490 | Yes | 52 (±13.4) | M 171 F 319 |

⩾5 | CIDI | 248/490 | NR | 301/490 | NR | NR | Low |

| Momartin et al. (2004) | Australia | HIC | Bosnian | 126 | No | 47 | M 49 F 77 |

NR | CAPS | NR | NR | 79/126 | NR | NR | Low |

| Naja et al. (2016) | Lebanon | LMIC | Syrian | 310 | No | 18-65 | M 120 F 189 |

NR | MINI | 136/310 | NR | NR | NR | NR | High |

| Nose et al. (2018) | Italy | HIC | Pakistan, Afghan, African, Ex-Yugoslavia | 109 | No | 30.0 (±7.60) | M 109 | >1 < 5 | MINI | 6/109 | NR | 9/109 | NR | NR | Low |

| Rasmussen et al. (2012) | USA | HIC | Mexican, South America, Chinese, Vietnamese | 660 | Yes | ⩾18 | M 345 F 315 |

NR | CIDI | 97/660 | NR | 8/660 | NR | NR | Low |

| Rees et al. (2019) | Australia | HIC | Arabic countries, Sri Lanka, Sudan. | 289 | Yes | 30.0 (±75.8) | F 289 | <1 >1 < 5 ⩾5 |

MINI | 94/289 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Low |

| Renner et al. (2006) | Austria | HIC | Chechnya, Afghan, West African | 150 | No | ⩾18 | M 110 F 40 |

NR | CAPS | NR | NR | 32/150 | NR | NR | High |

| Richter et al. (2018) | Germany | HIC | Iraninan, Russian, Iraqi, Afghan, Azerbaijan | 125 | No | 31.9 (± 0.6) | M 83 F 42 |

<1 | MINI | 9/125 | 7/125 | 22/125 | NR | 1/125 | High |

| Sagaltici et al. (2020) | Turkey | LMIC | Syrian | 342 | Yes | 33.7 (±10.0) | M 163 F 179 |

>1 < 5 | CAPS | NR | NR | 106/342 | NR | NR | High |

| Segal et al. (2018) | Lebanon | LMIC | Syrian, Palestinian | 254 | No | 40.4 (±13.5) | M 114 F 140 |

>1 < 5 | Modified-MINI | NR | NR | 13/254 | NR | 2/254 | High |

| Steel et al. (2002) | Australia | HIC | Vietnamese | 1161 | Yes | 41 (±14.2) | M 472 F 689 |

⩾5 | CIDI | 29/1161 | NR | 51/1161 | NR | NR | Low |

| Sundvall et al. (2020) | Sweden | HIC | Iraqi | 31 | No | 48 | F 14 M 17 |

⩾5 | MINI | 9/30 | NR | 13/30 | NR | NR | High |

| Tay et al. (2013) | Australia | HIC | Afghan, Chinese, Ganese, Iranian, Zimbabwe | 52 | No | 39 (±13.5) | M 34 F18 |

<1 | SCID | 30/52 | NR | 31/52 | NR | NR | Low |

| Tekeli-Yesil et al. (2018) | Turkey – Syria | LMIC | Syrian | 285 | No | 34.19 (± 1.7) | M 144 F 141 |

>1 < 5 | MINI | 201/285 | 104/238 | 85/285 | NR | NR | High |

| Tekin et al. (2016) | Turkey | LMIC | Iraqi | 238 | Yes | 32.70 (±11.8) | M 105 F 133 |

<1 | SCID | 94/238 | NR | 102/238 | NR | NR | Low |

| Turner et al. (2003) | UK | HIC | Kosovo | 120 | No | 37.1 | M 56 F 64 |

NR | CAPS | NR | NR | 46/118 | NR | NR | High |

| Van Ommeren et al. (2001a, 2001b) | Nepal | LMIC | Bhutanese | 810 | Yes | ⩾18 | M 616 F 194 |

⩾5 | CIDI | 23/810 | 139/810 | 197/810 | NR | NR | Low |

| von Lersner et al. (2008) | Germany | HIC | former Yugoslavia, Turkhis | 53 | No | 38.3 (±10.3) | M 25 F 28 |

⩾5 | MINI | 27/53 | NR | 29/53 | 1/53 | NR | Low |

| Wright et al. (2017) | USA | HIC | Iraqi | 291 | Yes | 34.30 (±11.3) | M 158 F 133 |

NR | SCID | 8/291 | NR | 11/291 | NR | NR | Low |

| Wulfes et al. (2019) | Germany | HIC | Afghan, Iranian, Iraqi, Syrian, Sudan | 118 | No | 32.9 (±13.1) | M 76 F 42 |

NR | SCID | 39/118 | NR | 35/118 | NR | NR | High |

PBR, population-based representative surveys; CAPS, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; HIC, High-income country; LMIC, Low middle-income country; MDD, Major depressive disorder; MINI, The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NR, Not reported; PSS-I, PTSD Symptom Scale–Interview; SCID, The Structured Clinical Interview for DS.

The prevalence of MDD was reported in 31 studies (Hinton et al., 1993; Van Ommeren et al., 2001a; Steel et al., 2002; Fenta et al., 2004; Laban et al., 2004; Marshall et al., 2005; Bhui et al., 2006; Von Lersner et al., 2008; Maier et al., 2010; Eckart et al., 2011; Jakobsen et al., 2011; Akinyemi et al., 2012; Bogic et al., 2012; Heeren et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2012; Tay et al., 2013; Llosa et al., 2014; Hocking et al., 2015, 2018; Naja et al., 2016; Tekin et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2017; Kizilhan, 2018; Nose et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., 2018; Rees et al., 2019; Wulfes et al., 2019; Bapolisi et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020; Sundvall et al., 2020): 23 reported only the prevalence of a current episode of MDD (Hinton et al., 1993; Steel et al., 2002; Marshall et al., 2005; Von Lersner et al., 2008; Maier et al., 2010; Eckart et al., 2011; Jakobsen et al., 2011; Akinyemi et al., 2012; Heeren et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2012; Tay et al., 2013; Hocking et al., 2015, 2018; Naja et al., 2016; Tekin et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2017; Kizilhan, 2018; Nose et al., 2018; Rees et al., 2019; Wulfes et al., 2019; Bapolisi et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020; Sundvall et al., 2020) (MDD) and 8 reported also prevalence of recurrent episode of MDD (reMDD) (Van Ommeren et al., 2001a; Fenta et al., 2004; Laban et al., 2004; Bhui et al., 2006; Bogic et al., 2012; Llosa et al., 2014; Richter et al., 2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., 2018) (Table 1). The pooled prevalence rate of MDD was 32% (95% CI 26–39%) with a very high heterogeneity between sample (I2 = 99.05%; p = 0.000) (Table 2 and figure 2.1). The random-effects pooled prevalence of reMDD was 16% (95% CI 10–22%) and the rates ranged from 4% to 44% (I2 = 96.3%; p = 0.000) (Table 2 and figure 2.2).

Table 2.

Prevalence rates of serious mental disorders

| Mental disorder | Prevalence rate (%) | Prevalence rates | Heterogeneity (I2) (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random pooled ES (95% CI) | ||||

| MDD | 32 | 26–39% | 99.05 | 0⋅000 |

| MDD (outliers removed) | 33 | 31–35% | 0.0 | 0.64 |

| MDD recurrent episode | 16 | 10–22% | 96.3 | 0⋅000 |

| PTSD | 31 | 25–38% | 99.3 | 0⋅000 |

| PTSD (outliers removed) | 32 | 30–35% | 50.2 | 0.05 |

| BPD | 5 | 2–9% | 97.7 | 0⋅000 |

| Psychosis | 1 | 1–2% | 0.00 | 0⋅000 |

MDD, Major depressive disorder; PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder; BPD, Bipolar disorder.

The prevalence of PTSD was reported in 36 studies (Hinton et al., 1993; Cheung, 1994; Van Ommeren et al., 2001b; Steel et al., 2002; Turner et al., 2003; Laban et al., 2004; Momartin et al., 2004; Marshall et al., 2005; Bhui et al., 2006; Renner et al., 2006; Von Lersner et al., 2008; Maier et al., 2010; Eckart et al., 2011; Jakobsen et al., 2011; Akinyemi et al., 2012; Bogic et al., 2012; Heeren et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2012; Tay et al., 2013; Llosa et al., 2014; Hocking et al., 2015; Tekin et al., 2016; Kazour et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2017; Kizilhan, 2018; Nose et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2018; Segal et al., 2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., 2018; Wulfes et al., 2019; Ainamani et al., 2020; Bapolisi et al., 2020; Civan Kahve et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020; Sagaltici et al., 2020; Sundvall et al., 2020) (Table 1). The random-effects pooled prevalence of PTSD was 31% (95% CI 25–38%) and the rates ranged from 1% to 88%. The heterogeneity between samples was high (I2 = 99.3%; p = 0.000) (Table 2 and figure 2.3).

The prevalence of BPD was reported in five articles (Bhui et al., 2006; Von Lersner et al., 2008; Akinyemi et al., 2012; Bogic et al., 2012; Llosa et al., 2014) (Table 1) and the random-effects pooled prevalence was 5% (95% CI 2–9%; I2 = 97.7%) (Table 2 and figure 2.4).

The prevalence of psychotic disorders was reported in five articles (Bhui et al., 2006; Bogic et al., 2012; Llosa et al., 2014; Richter et al., 2018; Segal et al., 2018) (Table 1). The random-effects pooled prevalence of the psychosis was 1% (95% CI 1–2%; I2 = 0.00%) (Table 2 and figure 2.5).

To reduce the high heterogeneity and confirm our prevalence rates, we also ran analyses without the outliers when it was possible. The analysis showed a prevalence of 33% of MDD and 32% of PTSD (Table 2 and online Supplementary materials).

Subgroups analysis showed a significant prevalence rates difference (p = 0.001) of MDD between studies conducted in refugees resettled in LMICs (Akinyemi et al., 2012; Llosa et al., 2014; Naja et al., 2016; Tekin et al., 2016; Tekeli-Yesil et al., 2018; Bapolisi et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020) (47%; 95% CI 38–57%) and those in HICs (Hinton et al., 1993; Van Ommeren et al., 2001a; Steel et al., 2002; Fenta et al., 2004; Laban et al., 2004; Momartin et al., 2004; Marshall et al., 2005; Bhui et al., 2006; Von Lersner et al., 2008; Maier et al., 2010; Eckart et al., 2011; Jakobsen et al., 2011; Bogic et al., 2012; Heeren et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2012; Tay et al., 2013; Hocking et al., 2015, 2018; Wright et al., 2017; Kizilhan, 2018; Nose et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2018; Rees et al., 2019; Wulfes et al., 2019; Sundvall et al., 2020) (28%; 95% CI 22–33%) (Table 3 and figure 3.1). Besides, a significant (p = 0.05) higher prevalence rate of MDD (37%; 95% CI 28–46%) has been reported in studies (Bhui et al., 2006; Von Lersner et al., 2008; Maier et al., 2010; Eckart et al., 2011; Akinyemi et al., 2012; Bogic et al., 2012; Heeren et al., 2012; Llosa et al., 2014; Hocking et al., 2015, 2018; Naja et al., 2016; Nose et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., 2018; Rees et al., 2019; Bapolisi et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020; Sundvall et al., 2020) conducted using the MINI as compared to studies that used others diagnostic interviews (Hinton et al., 1993; Van Ommeren et al., 2001a; Steel et al., 2002; Fenta et al., 2004; Laban et al., 2004; Momartin et al., 2004; Marshall et al., 2005; Jakobsen et al., 2011; Rasmussen et al., 2012; Tay et al., 2013; Tekin et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2017; Kizilhan, 2018; Wulfes et al., 2019) (26%; 95% CI 20–33%) (Table 3 and figure 3.2). In addition, studies (Turner et al., 2003; Fenta et al., 2004; Momartin et al., 2004; Bhui et al., 2006; Renner et al., 2006; Von Lersner et al., 2008; Maier et al., 2010; Eckart et al., 2011; Jakobsen et al., 2011; Heeren et al., 2012; Tay et al., 2013; Naja et al., 2016; Kazour et al., 2017; Hocking et al., 2018; Kizilhan, 2018; Nose et al., 2018; Richter et al., 2018; Segal et al., 2018; Tekeli-Yesil et al., 2018; Wulfes et al., 2019; Ainamani et al., 2020; Civan Kahve et al., 2020; Sundvall et al., 2020) which included participants from a convenience samples showed significant (p = 0.001) higher prevalence of MDD and PTSD (MDD: 35%; 95% CI 23–46%; PTSD: 34%; 95% CI 22–47%) than studies (Cheung, 1994; Van Ommeren et al., 2001a; Steel et al., 2002; Laban et al., 2004; Marshall et al., 2005; Akinyemi et al., 2012; Bogic et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2012; Llosa et al., 2014; Tekin et al., 2016; Wright et al., 2017; Rees et al., 2019; Bapolisi et al., 2020; Kaur et al., 2020; Sagaltici et al., 2020) conducted among probability-based samples (MDD: 30%; 95% CI 21–39%; PTSD: 28% 95% CI 19–37%) (Table 3 and figure 3.3). The heterogeneity between samples was high in all the subgroup analyses (I2 = 99.05%). The other analyses of the MDD, reMDD and PTSD subgroups, showed no significant differences among prevalence rates and high heterogeneity (Table 3 and online Supplementary materials). For psychotic disorders and BPD subgroup analyses were not conducted due to the limited number of studies.

Table 3.

Subgroups analysis results

| Major Depression Disorder (MDD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Categories | Random pooled ES (95% CI) | p | |

| Time since displacement | (⩾5) | 27 (16–37) | 0.55 | |

| (>1 < 5) | 36 (20–51) | |||

| (<1) | 26 (11–42) | |||

| Diagnostic interviews | MINI | 37 (28–46) | 0.05 | |

| Others* | 26 (20–33) | |||

| Country categories | LMICs | 47 (38–57) | 0.001 | |

| HICs | 28 (22–33) | |||

| Risk of bias | Low | 31 (24–39) | 0.74 | |

| High | 34 (22–45) | |||

| Population | Probability-based samples | 30 (21–39) | 0.001 | |

| Convenience samples | 35 (23–46) | |||

| Recurrent episode of MDD (reMDD) | ||||

| Time since displacement | (⩾5) | NP | NP | |

| (>1 < 5) | ||||

| (<1) | ||||

| Diagnostic interviews | MINI | 20 (9–30) | 0.168 | |

| Others* | 10 (3–8) | |||

| Country categories | LMICs | NP | NP | |

| HICs | ||||

| Risk of bias | Low | 14 (5–22) | 0.507 | |

| High | 18 (7–29) | |||

| Population | Probability-based samples | 15 (8–23) | 0.834 | |

| Convenience samples | 17 (4–30) | |||

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | ||||

| Time since displacement | (⩾5) | 35 (17–53) | 0.908 | |

| (>1 < 5) | 31 (20–42) | |||

| (<1) | 27 (13–41) | |||

| Diagnostic interviews | MINI | 30 (21–39) | 0.961 | |

| Others* | 33 (23–42) | |||

| Country categories | LMICs | 34 (17–52) | 0.641 | |

| HICs | 30 (23–36) | |||

| Risk of bias | Low | 30 (23–38) | 0.757 | |

| High | 33 (19–46) | |||

| Population | Probability-based samples | 28 (19–37) | 0.001 | |

| Convenience samples | 34 (22–47) | |||

Others: (CAPS, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DIS, Diagnostic Interview Schedule; SCID, The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM); MINI, The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; (⩾5): people who have spent more than five years as refugees or asylum seekers; (>1 < 5): people who have spent between 5 years and 1 year as refugees or asylum seekers; (<1): people who have spent less than 1 year as refugees or asylum seekers; HICs, High-income countries; LMICs, Low middle-income countries; NP, The aggregate prevalence of random effects was not allowed due to the limited number of the sample.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide the most recent and extensive overview of the prevalence rates of serious mental disorders across refugees and asylum-seeking populations. A comprehensive search was performed from inception to June 4, 2020 and was not intentionally updated to avoid interference caused by the effect of COVID-19 pandemic in this population. We included 40 studies in 11 053 participants, and all diagnoses were established with diagnostic interviews. Our study revealed that the most prevalent serious mental disorder in refugees and asylum seekers was MDD (32%), followed by PTSD (31%), recurrent episode of MDD (16%), and BPD (5%). The prevalence of psychotic disorders was 1%. Subgroup analyses showed that MDD appeared to be more prevalent (47%) among studies conducted in LMICs than in HICs (28%), and when the MINI (37%) has been used, compared to other diagnostic instruments (26%). PTSD and MDD showed higher prevalence rates (34% and 35% respectively) in studies where participants were from convenience samples in comparison to studies that used probability-based samples. PTSD and MDD were the most frequently evaluated disorders with 36 studies and 32 studies respectively, as opposed to BPD and psychosis of which we had only a few studies.

According to previous studies, the world-wide prevalence rate reported for MDD is 4.4% (WHO, 2017), the lifetime prevalence of PTSD in World Mental Health Surveys has been calculated between 3.9% and 5.6% (Koenen et al., 2017) and the prevalence rates of psychosis and BPD in the general population are 0.4% (Moreno-Kustner et al., 2018) and 2.5%, respectively (Carta and Angst, 2016). Comparing our results with the prevalence of the same disorders in the general population, suggests that MDD is seven times more likely in refugees and PTSD is 4 to 5 times more prevalent than in the general population (Koenen et al., 2017; WHO, 2017). Although BPD and psychosis are much rarer than MDD or PTSD, our study also indicated that externally displaced refugees and asylum seekers are two times more likely to be diagnosed with BPD and with psychosis than the general population (Carta and Angst, 2016; Moreno-Kustner et al., 2018). Studies have highlighted the role of trauma and stress experienced by minorities, social defeat, and discrimination as important risk factors for psychosis in refugees (Brandt et al., 2019; Duggal et al., 2020; Selten et al., 2020).

Our results are in line with the prevalence rates of the Blackmore and colleagues (Blackmore et al., 2020) study, who found a prevalence rates of 31.4% (95% CI 24.43–38.5) for PTSD, of 31.5% (95% CI 22.64–40.38) for depression, and 1.5% (95% CI 0.63–2.40) for psychosis. In addition, our study reports the random-effects pooled prevalence for BPD which has never examined before. Compared to the 2005 systematic review findings (Fazel et al., 2005), our rates prevalence showed an increase of serious mental disorders prevalence among refugees and asylum seekers from 5% (Fazel et al., 2005) to 32% for MDD, and from 9% (Fazel et al., 2005) to 31% for PTSD. One of the reasons for the discrepancy between these results could be the LMICs exclusion in Fazel and colleagues' systematic review. Furthermore, it might be explained by increased exposure to adverse events, increased financial hardship, social isolation, decreased access to adequate health care, as well as the lack of appropriate policies and investments in the last 15 years.

Our study methodology has several strengths, among which strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, a large number of included studies, and updated statistical methods. However, due to the low number of studies that examine refugees and asylum seekers separately, a limitation of this study was to consider these two groups together. Further, we found a large variability of prevalence rates and a high level of heterogeneity between studies. While high heterogeneity is very common in meta-analyses on prevalence rates (Higgins, 2008), we examined possible sources of heterogeneity between the included studies. Running the analyses without outliers did not alter the main results. Upon inspection of the pattern of outliers, no systematic differences between outlier studies from the rest of the studies were identified that might explain the high heterogeneity. However, due to the limit number of studies greater caution is required in interpreting the prevalence rates of BP and psychosis. In addition, we analysed subgroups under the mixed-effects model with inverse-variance weights under the random-effects model. The results of these subgroup analyses showed that significantly higher prevalence rates of MDD and PTSD in studies conducted among convenience samples than in studies that used probability-based samples. This result highlights the importance of having an adequate statistically representative sample of participants to avoid overestimating prevalence rates in a population as various and difficult to study as that of refugees and asylum seekers.

Furthermore, higher prevalence rates of MDD were found in LMICs than in HICs. This difference was not found for PTSD, where the prevalence rate was comparable between refugees and asylum seekers resettled in LMICs and HICs. The higher prevalence of MDD in refugees resettled in LMICs may be driven by higher exposure to post-migration living difficulties. Feelings of hopelessness, the failure of the migration project, and difficulties in integration may promote higher levels of depression (Steel et al., 2009; Charlson et al., 2019). Further, refugees resettled in LMICs can have a higher risk of developing MDD because of the lack of integration programs and mental health care due to the low investments in mental health care that unfortunately characterises the majority of these countries (Patel, 2007). On the other hand, compared to MDD, PTSD may have a stronger association with trauma exposure in the country of origin, which may not differ significantly between refugees in LMICs and HICs.

Another interesting finding was that we found a higher rate for MDD for studies conducted with the MINI than in studies that used different diagnostic interviews. This may be explained by the fact that the MINI may be administered by non-clinicians (similar to the CIDI, but dissimilar to the SCID I/P), and that its administration is shorter and its outcomes therefore potentially less precise.

Despite the high heterogeneity and methodological limitations of included studies, a high prevalence of serious mental disorders was found in refugees and asylum seekers diagnosed through structured clinical interviews. However, specific instruments culturally adapted for use across different local cultures and contexts for refugees would be advisable, since no one of the diagnostic instruments currently in use has been developed for the non-western populations, who represent the highest sample of refugees. For this reason, to reduce the high heterogeneity, more rigorous studies, using representative samples and culturally adapted instruments, to measure cultural concepts of distress would be recommended. Moreover, to strengthen the evidence base concerning the more serious mental disorders, further research on the prevalence of psychosis and BPD is imperative. To follow this goal, international and government investments in mental health research, population screening, and specific interventions on asylum seekers and refugees are warranted. However, until we have more rigorous studies and adequate diagnostic tools, due to the high heterogeneity between these studies, our results should be considered with caution.

Conclusion

In sum, our systematic review and meta-analysis show that it is imperative that governments and actors across the world acknowledge the devastating effect of war and prosecution on individuals' mental health. In order to prevent cycles of violence and victimisation, effective public mental health responses may be put in place to address worldwide suffering.

Data

All the data involved have been included in Tables and Figures of this paper, including online Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

None.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2022.29.

click here to view supplementary material

Financial support

This work was supported by Ayala Scholarship of Sapienza Foundation of Rome in Italy. Ayala Scholarship of Sapienza Foundation of Rome did not participate in any part of the process of the study (study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing the paper). The corresponding author had full access to all study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.

References

- Aboraya A, Rankin E, France C, El-Missiry A and John C (2006) The reliability of psychiatric diagnosis revisited: the clinician's guide to improve the reliability of psychiatric diagnosis. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 3, 41–50. Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21103149 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainamani HE, Elbert T, Olema DK and Hecker T (2020) Gender differences in response to war-related trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder – a study among the Congolese refugees in Uganda. BMC Psychiatry 20, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinyemi OO, Owoaje ET, Ige OK and Popoola OA (2012) Comparative study of mental health and quality of life in long-term refugees and host populations in Oru-Ijebu, Southwest Nigeria. BMC Research Notes 5, 394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon RD, Westermeyer J, Foulks EF and Ruiz P (1999) Clinical relevance of contemporary cultural psychiatry. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187, 465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bapolisi AM, Song SJ, Kesande C, Rukundo GZ and Ashaba S (2020) Post-traumatic stress disorder, psychiatric comorbidities and associated factors among refugees in Nakivale camp in Southwestern Uganda. BMC Psychiatry 20, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhui K, Craig T, Mohamud S, Warfa N, Stansfeld SA, Thornicroft G, Curtis S and McCrone P (2006) Mental disorders among Somali refugees: developing culturally appropriate measures and assessing socio-cultural risk factors. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41, 400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore R, Boyle JA, Fazel M, Ranasinha S, Gray KM, Fitzgerald G, Misso M and Gibson-Helm M (2020) The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine 17, e1003337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic M, Ajdukovic D, Bremner S, Franciskovic T, Galeazzi GM, Kucukalic A, Lecic-Tosevski D, Morina N, Popovski M, Schutzwohl M, Wang D and Priebe S (2012) Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. British Journal of Psychiatry 200, 216–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogic M, Njoku A and Priebe S (2015) Long-term mental health of war-refugees: a systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights 15, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt L, Henssler J, Müller M, Wall S, Gabel D and Heinz A (2019) Risk of psychosis among refugees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 76, 1133–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta MG and Angst J (2016) Screening for bipolar disorders: a public health issue. Journal of Affective Disorders 205, 139–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson F, van Ommeren M, Flaxman A, Cornett J, Whiteford H and Saxena S (2019) New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 394, 240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P (1994) Posttraumatic stress disorder among Cambodian refugees in New Zealand. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry 40, 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civan Kahve A, Aydemir MC, Yuksel RN, Kaya H, Unverdi Bicakci E and Goka E (2020) Evaluating the relationship between post traumatic stress disorder symptoms and psychological resilience in a sample of Turkoman refugees in Turkey. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 23, 434–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JT, Komproe IH and Van Ommeren M (2003) Common mental disorders in postconflict settings. Lancet 361, 2128–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domken M, Scott J and Kelly P (1994) What factors predict discrepancies between self and observer ratings of depression? Journal of Affective Disorders 31, 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggal AK, Kirkbride JB, Dalman C and Hollander AC (2020) Risk of non-affective psychotic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder by refugee status in Sweden. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 74, 276–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckart C, Stoppel C, Kaufmann J, Tempelmann C, Hinrichs H, Elbert T, Heinze HJ and Kolassa IT (2011) Structural alterations in lateral prefrontal, parietal and posterior midline regions of men with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 36, 176–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhard IM, van den Hout MA, Weerts J, Arntz A, Hox JJ and McNally RJ (2007) Deployment-related stress and trauma in Dutch soldiers returning from Iraq. Prospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry 191, 140–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M, Wheeler J and Danesh J (2005) Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: a systematic review. Lancet 365, 1309–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenta H, Hyman I and Noh S (2004) Determinants of depression among Ethiopian immigrants and refugees in Toronto. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192, 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo SQ, Tam WW, Ho CS, Tran BX, Nguyen LH, McIntyre RS and Ho RC (2018) Prevalence of depression among migrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacco D and Priebe S (2018) Mental health care for adult refugees in high-income countries. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 27, 109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacco D, Laxhman N and Priebe S (2018) Prevalence of and risk factors for mental disorders in refugees. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 77, 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren M, Mueller J, Ehlert U, Schnyder U, Copiery N and Maier T (2012) Mental health of asylum seekers: a cross-sectional study of psychiatric disorders. BMC Psychiatry 12, 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP (2008) Commentary: heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. International Journal of Epidemiology 37, 1158–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton WL, Chen YC, Du N, Tran CG, Lu FG, Miranda J and Faust S (1993) DSM-III-R disorders in Vietnamese refugees. Prevalence and correlates. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181, 113–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Kennedy GA and Sundram S (2015) Mental disorders in asylum seekers: the role of the refugee determination process and employment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 203, 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking DC, Mancuso SG and Sundram S (2018) Development and validation of a mental health screening tool for asylum-seekers and refugees: the STAR-MH. BMC Psychiatry 18, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt SM and Bhopal R (2004) Self report in clinical and epidemiological studies with non-English speakers: the challenge of language and culture. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 58, 618–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen M, Thoresen S and Johansen LEE (2011) The validity of screening for post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems among asylum seekers from different countries. Journal of Refugee Studies 24, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, Abdelalim A, Abdollahpour I, Abdulkader RS, Abebe Z, Abera SF, Abil OZ, Abraha HN, Abu-Raddad LJ, Abu-Rmeileh NME, Accrombessi MMK, Acharya D, Acharya P, Ackerman IN, Adamu AA, Adebayo OM, Adekanmbi V, Adetokunboh OO, Adib MG, Adsuar JC, Afanvi KA, Afarideh M, Afshin A, Agarwal G, Agesa KM, Aggarwal R, Aghayan SA, Agrawal S, Ahmadi A, Ahmadi M, Ahmadieh H, Ahmed MB, Aichour AN, Aichour I, Aichour MTE, Akinyemiju T, Akseer N, Al-Aly Z, Al-Eyadhy A, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Al-Raddadi RM, Alahdab F, Alam K, Alam T, Alashi A, Alavian SM, Alene KA, Alijanzadeh M, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Aljunid SM, Alkerwi AA, Alla F, Allebeck P, Alouani MML, Altirkawi K, Alvis-Guzman N, Amare AT, Aminde LN, Ammar W, Amoako YA, Anber NH, Andrei CL, Androudi S, Animut MD, Anjomshoa M, Ansha MG, Antonio CAT, Anwari P, Arabloo J, Arauz A, Aremu O, Ariani F, Armoon B, Ärnlöv J, Arora A, Artaman A, Aryal KK, Asayesh H, Asghar RJ, Ataro Z, Atre SR, Ausloos M, Avila-Burgos L, Avokpaho EFGA, Awasthi A, Ayala Quintanilla BP, Ayer R, Azzopardi PS, Babazadeh A, Badali H, Badawi A, Bali AG, Ballesteros KE, Ballew SH, Banach M, Banoub JAM, Banstola A, Barac A, Barboza MA, Barker-Collo SL, Bärnighausen TW, Barrero LH, Baune BT, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Bedi N, Beghi E, Behzadifar M, Behzadifar M, Béjot Y, Belachew AB, Belay YA, Bell ML, Bello AK, Bensenor IM, Bernabe E, Bernstein RS, Beuran M, Beyranvand T, Bhala N, Bhattarai S, Bhaumik S, Bhutta ZA, Biadgo B, Bijani A, Bikbov B, Bilano V, Bililign N, Bin Sayeed MS, Bisanzio D, Blacker BF, Blyth FM, Bou-Orm IR, Boufous S, Bourne R, Brady OJ, Brainin M, Brant LC, Brazinova A, Breitborde NJK, Brenner H, Briant PS, Briggs AM, Briko AN, Britton G, Brugha T, Buchbinder R, Busse R, Butt ZA, Cahuana-Hurtado L, Cano J, Cárdenas R, Carrero JJ, Carter A, Carvalho F, Castañeda-Orjuela CA, Castillo Rivas J, Castro F, Catalá-López F, Cercy KM, Cerin E, Chaiah Y, Chang AR, Chang H-Y, Chang J-C, Charlson FJ, Chattopadhyay A, Chattu VK, Chaturvedi P, Chiang PP-C, Chin KL, Chitheer A, Choi J-YJ, Chowdhury R, Christensen H, Christopher DJ, Cicuttini FM, Ciobanu LG, Cirillo M, Claro RM, Collado-Mateo D, Cooper C, Coresh J, Cortesi PA, Cortinovis M, Costa M, Cousin E, Criqui MH, Cromwell EA, Cross M, Crump JA, Dadi AF, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dargan PI, Daryani A, Das Gupta R, Das Neves J, Dasa TT, Davey G, Davis AC, Davitoiu DV, De Courten B, De La Hoz FP, De Leo D, De Neve J-W, Degefa MG, Degenhardt L, Deiparine S, Dellavalle RP, Demoz GT, Deribe K, Dervenis N, Des Jarlais DC, Dessie GA, Dey S, Dharmaratne SD, Dinberu MT, Dirac MA, Djalalinia S, Doan L, Dokova K, Doku DT, Dorsey ER, Doyle KE, Driscoll TR, Dubey M, Dubljanin E, Duken EE, Duncan BB, Duraes AR, Ebrahimi H, Ebrahimpour S, Echko MM, Edvardsson D, Effiong A, Ehrlich JR, El Bcheraoui C, El Sayed Zaki M, El-Khatib Z, Elkout H, Elyazar IRF, Enayati A, Endries AY, Er B, Erskine HE, Eshrati B, Eskandarieh S, Esteghamati A, Esteghamati S, Fakhim H, Fallah Omrani V, Faramarzi M, Fareed M, Farhadi F, Farid TA, Farinha CSES, Farioli A, Faro A, Farvid MS, Farzadfar F, Feigin VL, Fentahun N, Fereshtehnejad S-M, Fernandes E, Fernandes JC, Ferrari AJ, Feyissa GT, Filip I, Fischer F, Fitzmaurice C, Foigt NA, Foreman KJ, Fox J, Frank TD, Fukumoto T, Fullman N, Fürst T, Furtado JM, Futran ND, Gall S, Ganji M, Gankpe FG, Garcia-Basteiro AL, Gardner WM, Gebre AK, Gebremedhin AT, Gebremichael TG, Gelano TF, Geleijnse JM, Genova-Maleras R, Geramo YCD, Gething PW, Gezae KE, Ghadiri K, Ghasemi Falavarjani K, Ghasemi-Kasman M, Ghimire M, Ghosh R, Ghoshal AG, Giampaoli S, Gill PS, Gill TK, Ginawi IA, Giussani G, Gnedovskaya EV, Goldberg EM, Goli S, Gómez-Dantés H, Gona PN, Gopalani SV, Gorman TM, Goulart AC, Goulart BNG, Grada A, Grams ME, Grosso G, Gugnani HC, Guo Y, Gupta PC, Gupta R, Gupta R, Gupta T, Gyawali B, Haagsma JA, Hachinski V, Hafezi-Nejad N, Haghparast Bidgoli H, Hagos TB, Hailu GB, Haj-Mirzaian A, Haj-Mirzaian A, Hamadeh RR, Hamidi S, Handal AJ, Hankey GJ, Hao Y, Harb HL, Harikrishnan S, Haro JM, Hasan M, Hassankhani H, Hassen HY, Havmoeller R, Hawley CN, Hay RJ, Hay SI, Hedayatizadeh-Omran A, Heibati B, Hendrie D, Henok A, Herteliu C, Heydarpour S, Hibstu DT, Hoang HT, Hoek HW, Hoffman HJ, Hole MK, Homaie Rad E, Hoogar P, Hosgood HD, Hosseini SM, Hosseinzadeh M, Hostiuc M, Hostiuc S, Hotez PJ, Hoy DG, Hsairi M, Htet AS, Hu G, Huang JJ, Huynh CK, Iburg KM, Ikeda CT, Ileanu B, Ilesanmi OS, Iqbal U, Irvani SSN, Irvine CMS, Islam SMS, Islami F, Jacobsen KH, Jahangiry L, Jahanmehr N, Jain SK, Jakovljevic M, Javanbakht M, Jayatilleke AU, Jeemon P, Jha RP, Jha V, Ji JS, Johnson CO, Jonas JB, Jozwiak JJ, Jungari SB, Jürisson M, Kabir Z, Kadel R, Kahsay A, Kalani R, Kanchan T, Karami M, Karami Matin B, Karch A, Karema C, Karimi N, Karimi SM, Kasaeian A, Kassa DH, Kassa GM, Kassa TD, Kassebaum NJ, Katikireddi SV, Kawakami N, Karyani AK, Keighobadi MM, Keiyoro PN, Kemmer L, Kemp GR, Kengne AP, Keren A, Khader YS, Khafaei B, Khafaie MA, Khajavi A, Khalil IA, Khan EA, Khan MS, Khan MA, Khang Y-H, Khazaei M, Khoja AT, Khosravi A, Khosravi MH, Kiadaliri AA, Kiirithio DN, Kim C-I, Kim D, Kim P, Kim Y-E, Kim YJ, Kimokoti RW, Kinfu Y, Kisa A, Kissimova-Skarbek K, Kivimäki M, Knudsen AKS, Kocarnik JM, Kochhar S, Kokubo Y, Kolola T, Kopec JA, Kosen S, Kotsakis GA, Koul PA, Koyanagi A, Kravchenko MA, Krishan K, Krohn KJ, Kuate Defo B, Kucuk Bicer B, Kumar GA, Kumar M, Kyu HH, Lad DP, Lad SD, Lafranconi A, Lalloo R, Lallukka T, Lami FH, Lansingh VC, Latifi A, Lau KM-M, Lazarus JV, Leasher JL, Ledesma JR, Lee PH, Leigh J, Leung J, Levi M, Lewycka S, Li S, Li Y, Liao Y, Liben ML, Lim L-L, Lim SS, Liu S, Lodha R, Looker KJ, Lopez AD, Lorkowski S, Lotufo PA, Low N, Lozano R, Lucas TCD, Lucchesi LR, Lunevicius R, Lyons RA, Ma S, Macarayan ERK, Mackay MT, Madotto F, Magdy Abd El Razek H, Magdy Abd El Razek M, Maghavani DP, Mahotra NB, Mai HT, Majdan M, Majdzadeh R, Majeed A, Malekzadeh R, Malta DC, Mamun AA, Manda A-L, Manguerra H, Manhertz T, Mansournia MA, Mantovani LG, Mapoma CC, Maravilla JC, Marcenes W, Marks A, Martins-Melo FR, Martopullo I, März W, Marzan MB, Mashamba-Thompson TP, Massenburg BB, Mathur MR, Matsushita K, Maulik PK, Mazidi M, McAlinden C, McGrath JJ, McKee M, Mehndiratta MM, Mehrotra R, Mehta KM, Mehta V, Mejia-Rodriguez F, Mekonen T, Melese A, Melku M, Meltzer M, Memiah PTN, Memish ZA, Mendoza W, Mengistu DT, Mengistu G, Mensah GA, Mereta ST, Meretoja A, Meretoja TJ, Mestrovic T, Mezerji NMG, Miazgowski B, Miazgowski T, Millear AI, Miller TR, Miltz B, Mini GK, Mirarefin M, Mirrakhimov EM, Misganaw AT, Mitchell PB, Mitiku H, Moazen B, Mohajer B, Mohammad KA, Mohammadifard N, Mohammadnia-Afrouzi M, Mohammed MA, Mohammed S, Mohebi F, Moitra M, Mokdad AH, Molokhia M, Monasta L, Moodley Y, Moosazadeh M, Moradi G, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moradinazar M, Moraga P, Morawska L, Moreno Velásquez I, Morgado-Da-Costa J, Morrison SD, Moschos MM, Mountjoy-Venning WC, Mousavi SM, Mruts KB, Muche AA, Muchie KF, Mueller UO, Muhammed OS, Mukhopadhyay S, Muller K, Mumford JE, Murhekar M, Musa J, Musa KI, Mustafa G, Nabhan AF, Nagata C, Naghavi M, Naheed A, Nahvijou A, Naik G, Naik N, Najafi F, Naldi L, Nam HS, Nangia V, Nansseu JR, Nascimento BR, Natarajan G, Neamati N, Negoi I, Negoi RI, Neupane S, Newton CRJ, Ngunjiri JW, Nguyen AQ, Nguyen HT, Nguyen HLT, Nguyen HT, Nguyen LH, Nguyen M, Nguyen NB, Nguyen SH, Nichols E, Ningrum DNA, Nixon MR, Nolutshungu N, Nomura S, Norheim OF, Noroozi M, Norrving B, Noubiap JJ, Nouri HR, Nourollahpour Shiadeh M, Nowroozi MR, Nsoesie EO, Nyasulu PS, Odell CM, Ofori-Asenso R, Ogbo FA, Oh I-H, Oladimeji O, Olagunju AT, Olagunju TO, Olivares PR, Olsen HE, Olusanya BO, Ong KL, Ong SK, Oren E, Ortiz A, Ota E, Otstavnov SS, Øverland S, Owolabi MO,PA,M, Pacella R, Pakpour AH, Pana A, Panda-Jonas S, Parisi A, Park E-K, Parry CDH, Patel S, Pati S, Patil ST, Patle A, Patton GC, Paturi VR, Paulson KR, Pearce N, Pereira DM, Perico N, Pesudovs K, Pham HQ, Phillips MR, Pigott DM, Pillay JD, Piradov MA, Pirsaheb M, Pishgar F, Plana-Ripoll O, Plass D, Polinder S, Popova S, Postma MJ, Pourshams A, Poustchi H, Prabhakaran D, Prakash S, Prakash V, Purcell CA, Purwar MB, Qorbani M, Quistberg DA, Radfar A, Rafay A, Rafiei A, Rahim F, Rahimi K, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Rahimi-Movaghar V, Rahman M, Rahman MHU, Rahman MA, Rahman SU, Rai RK, Rajati F, Ram U, Ranjan P, Ranta A, Rao PC, Rawaf DL, Rawaf S, Reddy KS, Reiner RC, Reinig N, Reitsma MB, Remuzzi G, Renzaho AMN, Resnikoff S, Rezaei S, Rezai MS, Ribeiro ALP, Roberts NLS, Robinson SR, Roever L, Ronfani L, Roshandel G, Rostami A, Roth GA, Roy A, Rubagotti E, Sachdev PS, Sadat N, Saddik B, Sadeghi E, Saeedi Moghaddam S, Safari H, Safari Y, Safari-Faramani R, Safdarian M, Safi S, Safiri S, Sagar R, Sahebkar A, Sahraian MA, Sajadi HS, Salam N, Salama JS, Salamati P, Saleem K, Saleem Z, Salimi Y, Salomon JA, Salvi SS, Salz I, Samy AM, Sanabria J, Sang Y, Santomauro DF, Santos IS, Santos JV, Santric Milicevic MM, Sao Jose BP, Sardana M, Sarker AR, Sarrafzadegan N, Sartorius B, Sarvi S, Sathian B, Satpathy M, Sawant AR, Sawhney M, Saxena S, Saylan M, Schaeffner E, Schmidt MI, Schneider IJC, Schöttker B, Schwebel DC, Schwendicke F, Scott JG, Sekerija M, Sepanlou SG, Serván-Mori E, Seyedmousavi S, Shabaninejad H, Shafieesabet A, Shahbazi M, Shaheen AA, Shaikh MA, Shams-Beyranvand M, Shamsi M, Shamsizadeh M, Sharafi H, Sharafi K, Sharif M, Sharif-Alhoseini M, Sharma M, Sharma R, She J, Sheikh A, Shi P, Shibuya K, Shigematsu M, Shiri R, Shirkoohi R, Shishani K, Shiue I, Shokraneh F, Shoman H, Shrime MG, Si S, Siabani S, Siddiqi TJ, Sigfusdottir ID, Sigurvinsdottir R, Silva JP, Silveira DGA, Singam NSV, Singh JA, Singh NP, Singh V, Sinha DN, Skiadaresi E, Slepak ELN, Sliwa K, Smith DL, Smith M, Soares Filho AM, Sobaih BH, Sobhani S, Sobngwi E, Soneji SS, Soofi M, Soosaraei M, Sorensen RJD, Soriano JB, Soyiri IN, Sposato LA, Sreeramareddy CT, Srinivasan V, Stanaway JD, Stein DJ, Steiner C, Steiner TJ, Stokes MA, Stovner LJ, Subart ML, Sudaryanto A, Sufiyan MAB, Sunguya BF, Sur PJ, Sutradhar I, Sykes BL, Sylte DO, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Tadakamadla SK, Tadesse BT, Tandon N, Tassew SG, Tavakkoli M, Taveira N, Taylor HR, Tehrani-Banihashemi A, Tekalign TG, Tekelemedhin SW, Tekle MG, Temesgen H, Temsah M-H, Temsah O, Terkawi AS, Teweldemedhin M, Thankappan KR, Thomas N, Tilahun B, To QG, Tonelli M, Topor-Madry R, Topouzis F, Torre AE, Tortajada-Girbés M, Touvier M, Tovani-Palone MR, Towbin JA, Tran BX, Tran KB, Troeger CE, Truelsen TC, Tsilimbaris MK, Tsoi D, Tudor Car L, Tuzcu EM, Ukwaja KN, Ullah I, Undurraga EA, Unutzer J, Updike RL, Usman MS, Uthman OA, Vaduganathan M, Vaezi A, Valdez PR, Varughese S, Vasankari TJ, Venketasubramanian N, Villafaina S, Violante FS, Vladimirov SK, Vlassov V, Vollset SE, Vosoughi K, Vujcic IS, Wagnew FS, Waheed Y, Waller SG, Wang Y, Wang Y-P, Weiderpass E, Weintraub RG, Weiss DJ, Weldegebreal F, Weldegwergs KG, Werdecker A, West TE, Whiteford HA, Widecka J, Wijeratne T, Wilner LB, Wilson S, Winkler AS, Wiyeh AB, Wiysonge CS, Wolfe CDA, Woolf AD, Wu S, Wu Y-C, Wyper GMA, Xavier D, Xu G, Yadgir S, Yadollahpour A, Yahyazadeh Jabbari SH, Yamada T, Yan LL, Yano Y, Yaseri M, Yasin YJ, Yeshaneh A, Yimer EM, Yip P, Yisma E, Yonemoto N, Yoon S-J, Yotebieng M, Younis MZ, Yousefifard M, Yu C, Zadnik V, Zaidi Z, Zaman SB, Zamani M, Zare Z, Zeleke AJ, Zenebe ZM, Zhang K, Zhao Z, Zhou M, Zodpey S, Zucker I, Vos T and Murray CJL (2018). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. The Lancet, 392, 1789–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur K, Sulaiman AH, Yoon CK, Hashim AH, Kaur M, Hui KO, Sabki ZA, Francis B, Singh S and Gill JS (2020) Elucidating mental health disorders among Rohingya refugees: a Malaysian perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, 6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazour F, Zahreddine NR, Maragel MG, Almustafa MA, Soufia M, Haddad R and Richa S (2017) Post-traumatic stress disorder in a sample of Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Comprehensive Psychiatry 72, 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizilhan JI (2018) PTSD Of rape after IS (“Islamic State”) captivity. Archives of women's Mental Health 21, 517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Ratanatharathorn A, Ng L, McLaughlin KA, Bromet EJ, Stein DJ, Karam EG, Meron Ruscio A, Benjet C, Scott K, Atwoli L, Petukhova M, Lim CCW, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Bunting B, Ciutan M, de Girolamo G, Degenhardt L, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Kawakami N, Lee S, Navarro-Mateu F, Pennell BE, Piazza M, Sampson N, Ten Have M, Torres Y, Viana MC, Williams D, Xavier M and Kessler RC (2017) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychological Medicine 47, 2260–2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebber AM, Buffart LM, Kleijn G, Riepma IC, de Bree R, Leemans CR, Becker A, Brug J, van Straten A, Cuijpers P and Verdonck-de Leeuw IM (2014) Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psycho-oncology 23, 121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K (2001) Studying symptoms: sampling and measurement issues. Annals of Internal Medicine 134, 844–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg C, Doran T, Goddard M, Kendrick T, Gilbody S, Dare CR, Aylott L and Jacobs R (2017) Identifying primary care quality indicators for people with serious mental illness: a systematic review. The British Journal of General Practice 67, e519–e530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laban CJ, Gernaat HB, Komproe IH, Schreuders BA and De Jong JT (2004) Impact of a long asylum procedure on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in The Netherlands. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192, 843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis B, Benedetti A, Riehm KE, Saadat N, Levis AW, Azar M, Rice DB, Chiovitti MJ, Sanchez TA, Cuijpers P, Gilbody S, Ioannidis JPA, Kloda LA, McMillan D, Patten SB, Shrier I, Steele RJ, Ziegelstein RC, Akena DH, Arroll B, Ayalon L, Baradaran HR, Baron M, Beraldi A, Bombardier CH, Butterworth P, Carter G, Chagas MH, Chan JCN, Cholera R, Chowdhary N, Clover K, Conwell Y, de Man-van Ginkel JM, Delgadillo J, Fann JR, Fischer FH, Fischler B, Fung D, Gelaye B, Goodyear-Smith F, Greeno CG, Hall BJ, Hambridge J, Harrison PA, Hegerl U, Hides L, Hobfoll SE, Hudson M, Hyphantis T, Inagaki M, Ismail K, Jette N, Khamseh ME, Kiely KM, Lamers F, Liu SI, Lotrakul M, Loureiro SR, Lowe B, Marsh L, McGuire A, Mohd Sidik S, Munhoz TN, Muramatsu K, Osorio FL, Patel V, Pence BW, Persoons P, Picardi A, Rooney AG, Santos IS, Shaaban J, Sidebottom A, Simning A, Stafford L, Sung S, Tan PLL, Turner A, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Weert HC, Vohringer PA, White J, Whooley MA, Winkley K, Yamada M, Zhang Y and Thombs BD (2018) Probability of major depression diagnostic classification using semi-structured versus fully structured diagnostic interviews. British Journal of Psychiatry 212, 377–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis B, McMillan D, Sun Y, He C, Rice DB, Krishnan A, Wu Y, Azar M, Sanchez TA, Chiovitti MJ, Bhandari PM, Neupane D, Saadat N, Riehm KE, Imran M, Boruff JT, Cuijpers P, Gilbody S, Ioannidis JPA, Kloda LA, Patten SB, Shrier I, Ziegelstein RC, Comeau L, Mitchell ND, Tonelli M, Vigod SN, Aceti F, Alvarado R, Alvarado-Esquivel C, Bakare MO, Barnes J, Beck CT, Bindt C, Boyce PM, Bunevicius A, Couto TCE, Chaudron LH, Correa H, de Figueiredo FP, Eapen V, Fernandes M, Figueiredo B, Fisher JRW, Garcia-Esteve L, Giardinelli L, Helle N, Howard LM, Khalifa DS, Kohlhoff J, Kusminskas L, Kozinszky Z, Lelli L, Leonardou AA, Lewis BA, Maes M, Meuti V, Nakic Rados S, Navarro Garcia P, Nishi D, Okitundu Luwa EAD, Robertson-Blackmore E, Rochat TJ, Rowe HJ, Siu BWM, Skalkidou A, Stein A, Stewart RC, Su KP, Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Tadinac M, Tandon SD, Tendais I, Thiagayson P, Toreki A, Torres-Gimenez A, Tran TD, Trevillion K, Turner K, Vega-Dienstmaier JM, Wynter K, Yonkers KA, Benedetti A and Thombs BD (2019) Comparison of major depression diagnostic classification probability using the SCID, CIDI, and MINI diagnostic interviews among women in pregnancy or postpartum: an individual participant data meta-analysis. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 28, e1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llosa AE, Ghantous Z, Souza R, Forgione F, Bastin P, Jones A, Antierens A, Slavuckij A and Grais RF (2014) Mental disorders, disability and treatment gap in a protracted refugee setting. British Journal of Psychiatry 204, 208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T, Schmidt M and Mueller J (2010) Mental health and healthcare utilization in adult asylum seekers. Swiss Medical Weekly 140, w13110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez PV (2016) Mental Health Among Displaced People and Refugees. Available at 10.1596/25854. [DOI]

- Marshall GN, Schell TL, Elliott MN, Berthold SM and Chun CA (2005) Mental health of Cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. Jama 294, 571–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight PE and Kashdan TB (2009) The importance of functional impairment to mental health outcomes: a case for reassessing our goals in depression treatment research. Clinical Psychology Review 29, 243–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melsen WG, Bootsma MC, Rovers MM and Bonten MJ (2014) The effects of clinical and statistical heterogeneity on the predictive values of results from meta-analyses. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 20, 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ (1978) The inverse of the freeman – Tukey double arcsine transformation. The American Statistician 32, 138–138. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG and Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339, b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momartin S, Silove D, Manicavasagar V and Steel Z (2004) Comorbidity of PTSD and depression: associations with trauma exposure, symptom severity and functional impairment in Bosnian refugees resettled in Australia. Journal of Affective Disorders 80, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Kustner B, Martin C and Pastor L (2018) Prevalence of psychotic disorders and its association with methodological issues. A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 13, e0195687. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morina N, Akhtar A, Barth J and Schnyder U (2018) Psychiatric disorders in refugees and internally displaced persons after forced displacement: a systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry 9, 433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D and Tufanaru C (2015) Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13, 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naja WJ, Aoun MP, El Khoury EL, Abdallah FJ and Haddad RS (2016) Prevalence of depression in Syrian refugees and the influence of religiosity. Comprehensive Psychiatry 68, 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network EM (2018) Asylum and Migration Glossary 6.0. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/european_migration_network/glossary_en

- NIH NIOMH (2019) Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses. Retrieved March from Available at https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.

- Nose M, Turrini G, Imoli M, Ballette F, Ostuzzi G, Cucchi F, Padoan C, Ruggeri M and Barbui C (2018) Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress and psychiatric disorders in asylum seekers and refugees resettled in an Italian catchment area. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 20, 263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyaga VN, Arbyn M and Aerts M (2014) Metaprop: a stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Archives of Public Health = Archives Belges De Sante Publique 72, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palic S, Zerach G, Shevlin M, Zeligman Z, Elklit A and Solomon Z (2016) Evidence of complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) across populations with prolonged trauma of varying interpersonal intensity and ages of exposure. Psychiatry Research 246, 692–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V (2007) Mental health in low- and middle-income countries. British Medical Bulletin 81-82, 81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M and Haslam N (2005) Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis. Jama 294, 602–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A, Crager M, Baser RE, Chu T and Gany F (2012) Onset of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression among refugees and voluntary migrants to the United States. Journal of Traumatic Stress 25, 705–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees SJ, Fisher JR, Steel Z, Mohsin M, Nadar N, Moussa B, Hassoun F, Yousif M, Krishna Y, Khalil B, Mugo J, Tay AK, Klein L and Silove D (2019) Prevalence and risk factors of major depressive disorder among women at public antenatal clinics from refugee, conflict-affected, and Australian-born backgrounds. JAMA Netw Open 2, e193442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner W, Salem I and Ottomeyer K (2006) Cross-cultural validation of measures of traumatic symptoms in groups of asylum seekers from Chechnya, Afghanistan, and West Africa. Social Behavior and Personality 34, 1101–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Richter K, Peter L, Lehfeld H, Zaske H, Brar-Reissinger S and Niklewski G (2018) Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses in asylum seekers with follow-up. BMC Psychiatry 18, 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagaltici E, Alpak G and Altindag A (2020) Traumatic life events and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder among Syrian refugees residing in a camp in Turkey. Journal of Loss and Trauma 25, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Segal SP, Khoury VC, Salah R and Ghannam J (2018) Contributors to screening positive for mental illness in Lebanon's Shatila Palestinian refugee camp. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 206, 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selten JP, van der Ven E and Termorshuizen F (2020) Migration and psychosis: a meta-analysis of incidence studies. Psychological Medicine 50, 303–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett Sheehan K, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan MF and Dunbar GC (1997) The validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. European Psychiatry 12, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Slade M, Powell R and Strathdee G (1997) Current approaches to identifying the severely mentally ill. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32, 177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Silove D, Phan T and Bauman A (2002) Long-term effect of psychological trauma on the mental health of Vietnamese refugees resettled in Australia: a population-based study. Lancet 360, 1056–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, Marnane C, Bryant RA and van Ommeren M (2009) Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama 302, 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundvall M, Titelman D, DeMarinis V, Borisova L and Çetrez Ö (2020) Safe but isolated – an interview study with Iraqi refugees in Sweden about social networks, social support, and mental health. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 1–9. doi: 10.1177/0020764020954257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay K, Frommer N, Hunter J, Silove D, Pearson L, San Roque M, Redman R, Bryant RA, Manicavasagar V and Steel Z (2013) A mixed-method study of expert psychological evidence submitted for a cohort of asylum seekers undergoing refugee status determination in Australia. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 98, 106–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekeli-Yesil S, Isik E, Unal Y, Aljomaa Almossa F, Konsuk Unlu H and Aker AT (2018) Determinants of mental disorders in Syrian refugees in Turkey versus internally displaced persons in Syria. American Journal of Public Health 108, 938–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekin A, Karadag H, Suleymanoglu M, Tekin M, Kayran Y, Alpak G and Sar V (2016) Prevalence and gender differences in symptomatology of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among Iraqi Yazidis displaced into Turkey. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 7, 28556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs BD, Kwakkenbos L, Levis AW and Benedetti A (2018) Addressing overestimation of the prevalence of depression based on self-report screening questionnaires. Canadian Medical Association Journal 190, E44–E49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SW, Bowie C, Dunn G, Shapo L and Yule W (2003) Mental health of Kosovan Albanian refugees in the UK. British Journal of Psychiatry 182, 444–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR UNHCR (2006) Master Glossary of Terms. Available at https://www.unhcr.org/glossary/.

- UNHCR UNHCR (2020) Global report 2020. Available at https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/gr2020/pdf/GR2020_English_Full_lowres.pdf#_ga=2.50652713.1888700165.1632842480-1290971957.1623244785.

- Van Ommeren M, de Jong JT, Sharma B, Komproe I, Thapa SB and Cardena E (2001a) Psychiatric disorders among tortured Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. Archives of General Psychiatry 58, 475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]