Abstract

Background

Depression and anxiety are common within spine patient populations. The demand for surgical management of degenerative spine conditions and the prevalence of mental disorders are expected to increase as the general population ages. Concurrently, there is increasing pressure to demonstrate high-value care through improved perioperative outcome metrics and patient-reported outcome instruments. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of common mental disorders on perioperative markers of high resource utilization and patient-reported outcomes measurement information system physical function (PROMIS-PF) following thoracolumbar (TL) spine surgery.

Methods

A retrospective review of patients undergoing TL decompression alone or with fusion at a single institution. Data were collected using an administrative database for patient demographics. Outcomes of interest included length of stay, discharge disposition, 90-day return to the emergency department (ED), 90-day hospital readmission, 1-year complication rate, 1-year revision surgery rate, 1-year residual radiculopathy, and PROMIS-PF scores recorded preoperatively, at 0 to 1, 1 to 3, 3 to 6, and 6 to 12 months postoperatively. Univariate analysis and multiple linear regression were utilized to analyze results.

Results

A total of 596 patients were included in this study, of whom 205 (34%) had a history of depression or anxiety. Compared with patients with no history of a mental disorder, patients with depression or anxiety who underwent TL decompression alone had higher rates of 90-day ED visits (P = 0.019), 90-day readmissions (P = 0.031), and complications at 1 year (P = 0.012). After risk adjustment, the diagnosis of depression or anxiety had no significant effect on PROMIS-PF improvement from the preoperative to postoperative period.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that a history of depression or anxiety is common among patients undergoing spine surgery but has no significant impact on PROMIS-PF improvement. Because some patients with depression or anxiety may be at higher risk of postoperative resource utilization, further study and effort are warranted to support at-risk groups and improve overall care value.

Clinical Relevance

Although patients with depression or anxiety are at risk for increased resource utilization after TL decompression or fusion, they can experience similar levels of functional improvement as patients without these conditions. Therefore depression or anxiety should not be considered contraindications to surgery, but additional attention should be paid to this population during the postoperative recovery period.

Level of Evidence

4.

Keywords: depression, anxiety, spine surgery, outcomes, PROMIS

Introduction

Depression and anxiety are common mental health disorders with a worldwide prevalence of 5.7% and 7.3%, respectively, among adults older than 60 years.1,2 Menendez et al reported that 7% of patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery had either depression or anxiety.3 In a recent systematic review of patients with degenerative spine conditions, Chen et al reported a pooled prevalence of depression of 30.8%.4 Patton et al reported similar rates of psychological distress in a civilian spine clinic population and an even higher prevalence of approximately 80% in a veteran spine clinic population.5 The increasing prevalence of mental health disorders may pose additional challenges as the demand for surgical treatment of our aging population with degenerative disorders increases.1 Therefore, it is necessary to better understand the impact of mental health disorders on the delivery of high-value surgical care for spine patients.

High-value care should include treatment that results in significant improvement in patient-reported function and quality-of-life outcome instruments. While there are mixed findings in the literature, recent studies suggest that patients with depression and anxiety experience less improvement in patient-reported outcome instruments, including patient-reported outcomes measurement information system physical function (PROMIS-PF), PROMIS pain, and Oswestry Disability Index, compared with patients without a mental disorder or those who experienced improvement in depression as a result of the study.6,7 These findings suggest that care value could be improved by optimizing the mental health of patients undergoing spine surgery.

High resource utilization following spine surgery can also adversely impact the value of care by increasing cost. One of the most common reasons for resource utilization following spine surgery is uncontrolled pain.8,9 The presence of psychological distress including catastrophizing behavior, depression, and anxiety has been shown to have higher pain scores postoperatively.10 An imbalance of key neurotransmitters, which are important to modulatory pain pathways, may alter pain perception in patients with mental health disorders.11 Conversely, patients with better mental health may experience more pain relief and physical function improvement than those with poorer mental health.12 As such, studies have correlated mental disorders with higher rates of resource utilization after spine surgery, including the need for rehabilitation discharge and 30-day readmissions.12,13 Ideally, specific resources could be allocated to this subpopulation of spine patients and potentially reduce avoidable, costly readmissions.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of common mental disorders on perioperative outcomes and patient-reported outcomes in a population of patients undergoing degenerative thoracolumbar (TL) surgery. We hypothesized that patients with depression or anxiety may have higher rates of postoperative resource utilization and worse postoperative patient-reported outcomes.

Methods

The present study was reviewed by the institutional review board and deemed exempt by the institution’s clinical research committee. We performed a retrospective review of all patients undergoing TL decompression alone or with fusion at a single institution with 2 fellowship trained orthopedic spine surgeons between 1 January 2019 and 30 June 2021. No additional exclusion criteria were applied. Data were collected using an administrative database for patient demographics including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and race (white vs non-white), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status, smoking status, procedure performed (decompression alone or decompression and fusion), number of operative levels, surgery location (ie, whether thoracic levels were included), and relevant medical history, including the presence of a mental disorder diagnosis and related medications. Decompression and fusion procedures were further classified by the type of fusion performed—posterior lumbar interbody fusion or transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion, posterolateral fusion, or lateral lumbar interbody fusion or extreme lateral interbody fusion.

Outcome measures included perioperative markers of resource utilization as well as patient-reported outcomes. Perioperative outcomes of interest included length of stay days, discharge disposition, 90-day return to the emergency department (ED), and 90-day inpatient hospital readmission. The 1-year outcomes included the presence of a complication, revision surgery, revision surgery type (fusion or other), and residual radiculopathy. Complications were classified as hematoma, wound dehiscence or surgical site infection, pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis, compression fracture or broken hardware, and other medical complications. PROMIS-PF scores were recorded at clinic visits preoperatively, at 0 to 1, 1 to 3, 3 to 6, and 6 to 12 months postoperatively. PROMIS-PF scores were captured using the PROMIS-PF v2.0 short form 10a.

Patients were stratified into groups based on TL procedure type (TL decompression alone vs TL decompression and fusion), mental disorder status (presence or absence of depression [major depressive disorder] and/or anxiety [generalized anxiety disorder]), and pharmaceutical status (presence or absence of an antidepressant medication) as determined by review of the electronic medical record. Inferential statistics were utilized to determine the impact of having anxiety or depression on postoperative outcomes and PROMIS-PF scores. A subgroup analysis of patients with depression or anxiety was then performed to evaluate whether use of antidepressants affected postoperative clinical outcomes. Univariate analysis including χ 2 tests and independent sample t tests was used to determine differences among groups. The Fisher’s exact test was performed when the assumptions of χ 2 testing were not met. Multiple linear regression was then performed to evaluate the effect of depression or anxiety on improvement in PROMIS-PF scores after adjusting for confounding factors. The change from preoperative to the highest PROMIS-PF score achieved postoperatively was used as the endpoint for regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS 25.0, IBM Inc., Somers, NY).

Results

A total of 596 patients were included in our population. Of those patients, 205 (34%) had prior diagnoses of depression or anxiety and 391 (66%) did not. Three hundred forty-two (57%) patients underwent TL decompression alone, and 254 (43%) patients underwent TL decompression and fusion. Patients with depression or anxiety were more likely to be white, of female sex, have a higher BMI, and have a higher ASA score than those without depression or anxiety (all P < 0.05) (Table 1). No significant differences in types of fusion performed, number of operative levels, or whether surgery involved thoracic levels were observed between cohorts. In total, thoracic level procedures were performed in 41 patients (6.9%). Of the 205 patients with depression or anxiety, 65 (31.7%) had depression only, 66 (32.3%) had anxiety only, 74 (36.1%) had a combination of both, and 126 (61.5%) were on antidepressant medications. Eight patients (3.9%) had a concomitant diagnosis of bipolar disorder, and no other psychiatric comorbidities were identified in this population (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and surgeries performed.

| Variable | No Depression or Anxiety (n = 391) | Depression or Anxiety (n = 205) | P Value |

| Age | 61.2 ± 14.3 | 61.7 ± 13.3 | 0.682 |

| Female sex | 154 (39.4) | 135 (65.9) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index | 30.1 ± 5.9 | 31.4 ± 6.5 | 0.020 |

| Non-white race a | 63 (16.8) | 13 (6.6) | 0.001 |

| Current smoker | 32 (8.2) | 23 (11.2) | 0.224 |

| Former smoker | 132 (33.8) | 82 (40.0) | 0.131 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists score ≥3 | 163 (41.7) | 112 (54.6) | 0.003 |

| Surgery performed | 0.042 | ||

| Decompression | 236 (60.4) | 106 (51.7) | |

| Fusion | 155 (39.6) | 99 (48.3) | |

| Fusion type | |||

| Posterior lumbar interbody fusion/transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion | 81 (52.3) | 48 (48.5) | 0.557 |

| Posterolateral fusion | 63 (40.6) | 41 (41.4) | 0.903 |

| Lateral lumbar interbody fusion/extreme lateral interbody fusion | 11 (7.1) | 10 (10.1) | 0.396 |

| Operative levels | 0.088 | ||

| 1–2 Levels | 324 (82.9) | 158 (77.1) | |

| 3+ Levels | 67 (17.1) | 47 (22.9) | |

| Surgery included thoracic levels | 23 (5.9) | 18 (8.8) | 0.184 |

Note: P values <0.05 in bold.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or n (%).

Race not reported for 22 patients.

Table 2.

Depression or anxiety patient cohort details (n = 205).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

| Depression only | 65 (31.7) |

| Anxiety only | 66 (32.3) |

| Depression and anxiety | 74 (36.1) |

| On antidepressant medication | 126 (61.5) |

| Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | 29 (14.1) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 74 (36.1) |

| Other | 29 (14.1) |

| Other concomitant psychiatric conditions | |

| Bipolar disorder | 8 (3.9) |

| Schizophrenia | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) |

Perioperative clinical outcomes were assessed by mental disorder status and procedure type. Compared with patients with no mental health history, patients with depression or anxiety who underwent TL decompression alone had higher rates of 90-day ED visits (P = 0.019), 90-day readmissions (P = 0.031), and 1-year complications (P = 0.012), although no significant differences in any specific complication type were observed. There were no significant differences in length of stay, rates of home discharge, the presence of residual radiculopathy at 1 year, or 1-year revision surgery between groups undergoing TL decompression alone. Ten decompression alone (2.9%) patients proceeded to have a fusion within 1 year, but no significant differences in rates of conversion to fusion were observed between depression and anxiety and no depression or anxiety cohorts. Within the TL decompression and fusion population, there were no significant differences in any of the perioperative outcomes regardless of mental health status (Table 3). When comparing perioperative outcomes of patients with depression or anxiety by pharmaceutical status and procedure type, there were no differences in any of the outcome measures evaluated (Table 4).

Table 3.

Patient outcomes by depression/anxiety status and procedure type.

| Outcome Measure | Decompression | Fusion | ||||

| No Depression or Anxiety (n = 236) | Depression or Anxiety (n = 106) |

P Value | No Depression or Anxiety (n = 155) | Depression or Anxiety (n = 99) | P Value | |

| Length of stay, d | 0.48 ± 1.15 | 0.50 ± 1.85 | 0.898 | 2.62 ± 2.29 | 3.01 ± 2.39 | 0.194 |

| Home discharge | 235 (99.6) | 105 (99.1) | 0.524 a | 139 (89.7) | 85 (85.9) | 0.358 |

| 90-d emergency department return | 23 (9.7) | 20 (18.9) | 0.019 | 31 (20.0) | 17 (17.2) | 0.574 |

| 90-d readmission | 6 (2.5) | 8 (7.5) | 0.031 | 20 (12.9) | 12 (12.1) | 0.855 |

| 1-y complication | 2 (0.8) | 6 (5.7) | 0.012 a | 9 (5.8) | 4 (4.0) | 0.533 |

| Hematoma | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.9) | 0.591 a | 4 (2.6) | 1 (1.0) | 0.651 a |

| Wound dehiscence or SSI | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.9) | 0.095 a | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1.000 a |

| Pulmonary embolism or DVT | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0.310 a | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 a |

| Compression fracture or broken hardware | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 0.310 a | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 1.000 a |

| Other medical | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | N/A | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.0) | 1.000 a |

| 1-y residual radiculopathy | 13 (5.5) | 10 (9.4) | 0.180 | 3 (1.9) | 3 (3.0) | 0.575 |

| 1-y revision surgery | 13 (5.5) | 9 (8.5) | 0.299 | 8 (5.2) | 4 (4.0) | 0.770 a |

| Revision fusion | 6 (2.5) | 4 (3.8) | 0.507 a | 4 (2.6) | 4 (4.0) | 0.715 a |

| Follow-up, mo | 7.2 ± 7.2 | 7.5 ± 8.3 | 0.712 | 10.6 ± 7.0 | 10.6 ± 7.7 | 0.953 |

Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis; SSI, surgical site infection.

Note: P values <0.05 in bold.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or n (%).

Fisher’s exact test.

Table 4.

Patient outcomes by antidepressant usage and procedure type in patients with depression or anxiety.

| Outcome Measure | Decompression | Fusion | ||||

| Antidepressant Use (n = 43) | No Antidepressant Use (n = 63) | P Value | Antidepressant Use (n = 36) | No Antidepressant Use (n = 63) | P Value | |

| Length of stay, d | 0.44 ± 2.00 | 0.54 ± 1.76 | 0.791 | 3.56 ± 3.18 | 2.70 ± 1.75 | 0.142 |

| Home discharge | 42 (97.7) | 63 (100.0) | 0.406 a | 30 (83.3) | 55 (87.3) | 0.586 |

| 90-d emergency department return | 7 (16.3) | 13 (20.6) | 0.574 | 9 (25.0) | 8 (12.7) | 0.118 |

| 90-d readmission | 2 (4.7) | 6 (9.5) | 0.469 a | 6 (16.7) | 6 (9.5) | 0.345 a |

| 1-y complication | 0 (0.0) | 6 (9.5) | 0.079 a | 3 (8.3) | 1 (1.6) | 0.135 a |

| 1-y residual radiculopathy | 4 (9.3) | 6 (9.5) | 1.000 a | 2 (5.6) | 1 (1.6) | 0.299 a |

| 1-y revision surgery | 4 (9.3) | 5 (7.9) | 1.000 a | 3 (8.3) | 1 (1.6) | 0.135 a |

| Follow-up, mo | 8.4 ± 8.5 | 7.0 ± 8.2 | 0.408 | 12.6 ± 8.2 | 9.5 ± 7.2 | 0.053 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or n (%).

Fisher’s exact test.

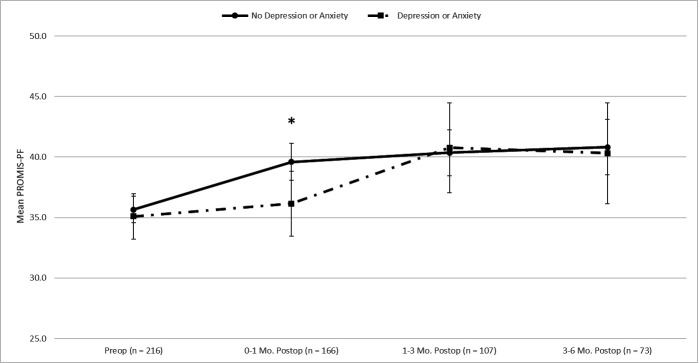

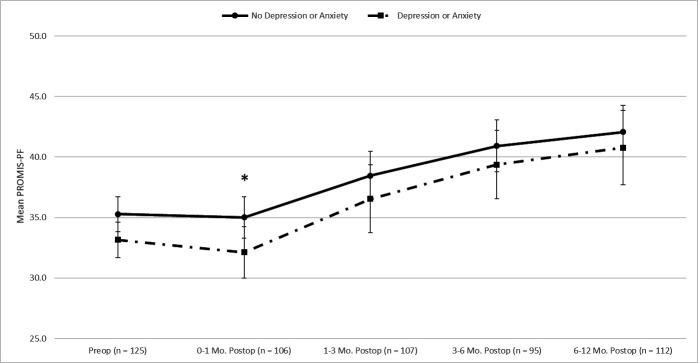

PROMIS-PF scores were then assessed by mental disorder status and procedure type. Compared with patients with no mental disorder history, patients with depression or anxiety who underwent TL decompression alone had similar baseline preoperative PROMIS-PF scores (35.1 vs 35.7, P = 0.581). Patients with depression or anxiety had significantly lower PROMIS-PF scores at 0- to 1-month postoperative follow-up (36.1 vs 39.6, P = 0.021). By the 1- to 3-month and 3- to 6-month follow-up, their PROMIS-PF scores were equivalent to those without a mental disorder (Figure 1). In patients undergoing TL decompression and fusion, those with depression or anxiety had worse preoperative PROMIS-PF scores compared with those without a mental disorder; however, this was not significant (33.2 vs 35.3, P = 0.052). This trend continued throughout their follow-up but was only significant at the 0- to 1-month follow-up (32.1 vs 35.0, P = 0.046) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Average patient-reported outcomes measurement information system physical function score over time in patients undergoing decompression surgery. Postop, postoperative; Preop, preoperative.

Figure 2.

Average patient-reported outcomes measurement information system physical function score over time: patients undergoing fusion surgery. Postop, postoperative; Preop, preoperative.

After risk adjustment for BMI, sex, non-white race, ASA ≥3, and fusion surgery, a diagnosis of depression or anxiety had no significant effect on PROMIS-PF physical function improvement from the preoperative to postoperative period (Table 5).

Table 5.

Risk-adjusted effect of depression or anxiety on maximum patient-reported outcomes measurement information system physical function improvement.

| Variable | Unadjusted β | 95% CI | P Value |

| Body mass index | −0.028 | −0.234 to 0.179 | 0.793 |

| Female sex | 0.422 | −2.218 to 3.062 | 0.753 |

| Non-white race | 2.547 | −1.346 to 6.440 | 0.199 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists score ≥3 | −0.892 | −3.599 to 1.814 | 0.517 |

| Fusion surgery | 0.383 | −2.173 to 2.940 | 0.768 |

| Depression or anxiety | 1.003 | −1.744 to 3.750 | 0.473 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or n (%).

Discussion

Depression and anxiety are commonly encountered mental disorders, which we observed in one-third of our patient population. Following spine surgery, a history of either depression or anxiety may have the greatest impact on early postoperative outcomes, particularly for those patients undergoing TL decompression alone. However, the presence of a mental disorder had no significant effect on PROMIS-PF improvement regardless of procedure type. These findings demonstrate that while patients with mental disorders may be at increased risk for increased resource utilization during the early postoperative period, they can experience similar positive effects on quality of life as those without these conditions following spine surgery.

It is generally accepted that the rate of readmissions and complications for TL decompression and fusion surgery is greater compared with TL decompression surgery alone. Interestingly in our population, patients undergoing TL decompression alone with a history of a mental disorder had higher rates of 90-day ED visits and hospital readmissions, which along with 1-year complications, more closely resembled the perioperative outcomes of the TL decompression and fusion group as a whole. Further analysis is warranted to understand the reasons for readmission in this group of patients.

In contrast to recent studies,12,14,15 our population experienced similar improvement in patient-reported outcome measures regardless of mental disorder status. Aside from early postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing decompression alone, there was no difference in PROMIS-PF scores after the 1-month postoperative period regardless of surgery type. Patients with depression or anxiety undergoing decompression and fusion trended toward lower preoperative and postoperative PROMIS-PF scores, but this difference was not significant, and patients in both groups demonstrated similar improvement. In a prospective longitudinal cohort study, Carreon et al evaluated the relationship between measures of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and postoperative outcomes. Utilizing the medical outcomes study short form-36 and Oswestry Disability Index, they found, in contrast to our own findings, that preoperative mental health, disease burden, and level of disability were all predictive of outcomes after lumbar surgery. Patients with worse mental health, increased disease burden, and higher level of disability experienced less postoperative improvement in HRQOL.14 In a retrospective review of patients undergoing minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion, Yoo et al found that patients with worse preoperative mental health as measured by short form-12 mental health composite score experienced a similar trend in improvement to those with better preoperative mental health scores. However, these patients had significantly worse PROMIS-PF scores at all timepoints and also demonstrated significantly less improvement from baseline at 1 year postoperatively.15 Lastly, in a retrospective review of 10,109 patients, Huang et al evaluated the impact of preoperative psychiatric disorders on both hospital and postdischarge outcomes after spine surgery for degenerative thoracic or lumbar spine disease. They demonstrated that mood disorders, including depression and bipolar disorder, were independent risk factors of in-hospital and postdischarge adverse events while anxiety decreased the risk of extended hospitalization.12

Other studies have found results in alignment with our own.16,17 In a retrospective review of 122 patients who underwent laminectomy without fusion for lumbar spinal stenosis, Kobayashi et al evaluated the influence of preoperative mental health on postoperative clinical outcomes.16 The authors of this study utilized various patient-reported outcome measures to establish a preoperative baseline and assess postoperative HRQOL. They demonstrated that patients with lower preoperative mental health scores (≤36.2 on Short Form-8) had significant improvements in postoperative HRQOL scores but no significant differences compared with those with higher preoperative mental health scores.16 Furthermore, in a retrospective comparative study, Divi et al evaluated outcomes of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion surgery in patients with and without preoperative depression. They demonstrated that although patients with depression had worse outcome scores at baseline and after surgery, the improvement for each patient from baseline and percent minimal clinical important difference was similar between groups.17

In synthesizing our results and those of previously published studies, one must ask, “how should patients with preoperative depression and/or anxiety and an indication for surgery be managed?” Based on the current literature, we suggest concomitant depression or anxiety is not a contraindication for surgery but does present increased risk for early complications. Patients should be counseled about this risk and made aware of appropriate resources to address postoperative concerns. At our institution, programs such as home-based outpatient physical therapy visits and nurse navigator education have been shown to effectively improve early postoperative outcomes after joint and spine surgery.18–20 Therefore, we suggest providing these additional resources to patients with depression or anxiety may mitigate the risk of early complications and delayed physical function improvements. When evaluating these populations, another factor that must be considered is the effect of taking antidepressant medications prior to undergoing surgery. Our results demonstrated that taking antidepressants prior to surgery had no significant impact on the hospital outcomes or PROMIS-PF scores. Similarly, in a retrospective analysis of 140 patients undergoing anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, Elsamadicy et al had results similar to our own demonstrating patients pretreated with antidepressants did not have inferior long-term outcomes after surgery.21 Based on the paucity of evidence regarding the effect of antidepressant medications on postoperative outcomes, we do not advocate for routine triage of these patients to undergo additional psychiatric evaluation, and suggest this be reserved for patients who appear at the highest risk based on surgeon evaluation.

The greatest limitation of our study was the retrospective approach to identifying a mental health disorder. Our methods included a manual chart review of the past medical history and medications to identify the presence or absence of depression, anxiety, or an associated antidepressant medication. We reviewed documentation from surgeon office visits, preoperative medical clearances, anesthesiologists, and a variety of additional providers within a large health system network who document within the electronic medical record. This differs from other studies, which instead attempt to identify and quantify mental disorders or psychological distress through the use of specific mental health outcome instruments. It is possible, therefore, that our approach may not accurately represent the burden of each patient’s condition. However, we felt that our approach was practical in application, and that the data collected could be obtained by any health care provider in the absence of specific instruments to evaluate mental health. Furthermore, we elected not to stratify our population by the presence of depression alone, anxiety alone, or depression and anxiety. This methodology was selected given the difficulty of distinguishing between these often overlapping conditions in clinical practice, and our belief that the surgeon’s approach to managing patients with either depression or anxiety or a combination thereof will likely be the same. In addition, given the relatively small sample size of this study, it is underpowered to compare outcomes across these subgroups, and the evaluation of this topic is an opportunity for future studies. A second limitation of the study is a lack of radiographic confirmation of fusion. Third, although we were able to stratify patients by the presence or absence of a prescribed medication for mental disease, we are unable to evaluate medication compliance through the retrospective design of this study. Fourth, the relatively wide patient-reported outcomes response windows leave potential for significant variation, particularly in the 6- to 12-month interval. At our clinic, patient-reported outcomes are distributed at each clinic visit, therefore making responses subject to variability in follow-up patterns. The time intervals identified for this study were selected to align with our standard follow-up visits of 2 to 4 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months in fusion patients. A final limitation of this study was the heterogeneity of surgery types and operative levels included. Although sample size precluded our ability to stratify our results by these important characteristics, the similar distribution of both fusion types and proportion of surgeries involving thoracic levels across the cohorts support the assertion that these factors did not bias our results. Follow-up studies evaluating the impact of depression and anxiety on outcomes within specific subgroups of pathologies and procedure types are needed to confirm our findings.

Given the findings of our study and mixed reports of the impact of depression and anxiety in the literature, further research as to how mental disorders may impact outcomes and care value are warranted. Optimizing mental health or providing specific resources to patients with mental disorders could lead to improved perioperative metrics or improved patient-reported outcomes. ED visits, hospital readmissions, and complications are costly events that can negatively impact the value of care.

Conclusion

Mental disorders are prevalent within patients with spine pathology. In our study population, depression or anxiety was present in one-third of patients undergoing surgery. Contrary to other reports, the presence of a mental disorder did not significantly impact PROMIS-PF outcomes in our study population, and both groups experienced similar improvement in functional outcome scores. However, patients with depression or anxiety undergoing decompression alone had higher rates of postoperative resource utilization including ED visits, hospital readmissions, and complications. Additional research should aim to improve the value of care delivered by reducing preventable ED visits and readmissions in this population.

References

- 1. Menendez ME, Neuhaus V, Bot AGJ, Ring D, Cha TD. Psychiatric disorders and major spine surgery: epidemiology and perioperative outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(2):E111–E122. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression. 27 December 2021.

- 3. Manchikanti L, Helm S, Fellows B. Opioid epidemic in the united states. Pain Phys. 2012;3S;15(3S;7):ES9–ES38. https://painphysicianjournal.com/current/past?journal=68. 10.36076/ppj.2012/15/ES9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen Z, Luo R, Yang Y, Xiang Z. The prevalence of depression in degenerative spine disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2021;30(12):3417–3427. 10.1007/s00586-021-06977-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patton CM, Hung M, Lawrence BD, et al. Psychological distress in a department of veterans affairs spine patient population. Spine J. 2012;12(9):798–803. 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Merrill RK, Zebala LP, Peters C, Qureshi SA, McAnany SJ. Impact of depression on patient-reported outcome measures after lumbar spine decompression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43(6):434–439. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rahman R, Ibaseta A, Reidler JS, et al. Changes in patients’ depression and anxiety associated with changes in patient-reported outcomes after spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2020::1–20:2019.11.SPINE19586. 10.3171/2019.11.SPINE19586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Parker SL, Xu R, McGirt MJ, Witham TF, Long DM, Bydon A. Long-term back pain after a single-level discectomy for radiculopathy: incidence and health care cost analysis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12(2):178–182. 10.3171/2009.9.SPINE09410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weir S, Samnaliev M, Kuo T-C, et al. The incidence and healthcare costs of persistent postoperative pain following lumbar spine surgery in the UK: a cohort study using the clinical practice research datalink (CPRD) and hospital episode statistics (HES). BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e017585. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dunn LK, Durieux ME, Fernández LG, et al. Influence of catastrophizing, anxiety, and depression on in-hospital opioid consumption, pain, and quality of recovery after adult spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;28(1):119–126. 10.3171/2017.5.SPINE1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson T, Correll CU, Gallop K, Vancampfort D, Stubbs B. Is pain perception altered in people with depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental pain research. J Pain. 2016;17(12):1257–1272. 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang Y-C, Chang C-H, Lin C-L, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of major psychiatric disorders preceding index surgery for degenerative thoracic/lumbar spine disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):10:5391. 10.3390/ijerph18105391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adogwa O, Elsamadicy AA, Mehta AI, et al. Association between baseline affective disorders and 30-day readmission rates in patients undergoing elective spine surgery. World Neurosurg. 2016;94:432–436. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.07.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carreon LY, Glassman SD, Djurasovic M, et al. Are preoperative health-related quality of life scores predictive of clinical outcomes after lumbar fusion? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(7):725–730. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318198cae4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yoo JS, Hrynewycz NM, Brundage TS, et al. The influence of preoperative mental health on PROMIS physical function outcomes following minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020;45(4):E236–E243. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kobayashi Y, Ogura Y, Kitagawa T, et al. The influence of preoperative mental health on clinical outcomes after laminectomy in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019;185:105481. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2019.105481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Divi SN, Goyal DKC, Mangan JJ, et al. Are outcomes of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion influenced by presurgical depression symptoms on the mental component score of the short form-12 survey? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020;45(3):201–207. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kelmer GC, Turcotte JJ, Dolle SS, Angeles JD, MacDonald JH, King PJ. Preoperative education for total joint arthroplasty: does reimbursement reduction threaten improved outcomes? J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(8):2651–2657. 10.1016/j.arth.2021.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Menon N, Turcotte JJ, Stone AH, Adkins AL, MacDonald JH, King PJ. Outpatient, home-based physical therapy promotes decreased length of stay and post-acute resource utilization after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(8):1968–1972. 10.1016/j.arth.2020.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Turcotte J, Menon N, Andersen K, Stone D, Patton C. The impact of nurse navigator-led preoperative education on hospital outcomes following posterolateral lumbar fusion surgery. Orthop Nurs. 2021;40(5):281–289. 10.1097/NOR.0000000000000787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elsamadicy AA, Adogwa O, Cheng J, Bagley C. Pretreatment of depression before cervical spine surgery improves patients’ perception of postoperative health status: a retrospective, single institutional experience. World Neurosurg. 2016;87:214–219. 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]