Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to examine COVID-19 pandemic-related changes in obesity and BMI among patients aged 5 to <20 years with selected chronic conditions.

Methods:

A longitudinal study in 293,341 patients aged 5 to <20 years who were prescribed one of five medication classes (for depression, psychosis, hypertension, diabetes, or epilepsy) and who had BMI measures from January 2019 to March 2021 was conducted. Generalized estimating equations and linear mixed-effects models were used, accounting for within-child repeated measures and stratified by age, race, ethnicity, gender, and class of medication prescribed, to compare obesity and BMI z score during the pandemic (June through December 2020) versus pre-pandemic (June through December 2019).

Results:

Obesity prevalence increased from 23.8% before the pandemic to 25.5% during the pandemic; mean (SD) BMI z score increased from 0.62 (1.26) to 0.65 (1.29). Obesity prevalence during the pandemic increased at a faster rate compared with pre-pandemic among children aged 5 to <13 years (0.27% per month; 95% CI: 0.11%-0.44%) and 13 to <18 years (0.24% per month; 95% CI: 0.09%-0.40%), with the largest increases among children aged 5 to <13 years who were male (0.42% per month), Black (0.35% per month), or Hispanic (0.59% per month) or who were prescribed antihypertensives (0.28% per month).

Conclusions:

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the obesity epidemic and widened disparities among children with selected chronic conditions. These findings highlight the importance of continuing efforts to specifically help high-risk populations who are experiencing weight gain from the pandemic.

INTRODUCTION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, children and adolescents have experienced increased stress, school closures, and less opportunity for physical activity and proper nutrition [1], all of which are risk factors for weight gain [2–5]. Three recent studies in the United States among children aged 2 to 17 years in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania [2]; southern California [3]; and Massachusetts [4] have found increases in obesity prevalence during versus before COVID-19, particularly in Black and Hispanic youths [2, 4]. Three recent studies in England [6], Germany [7], and South Korea [8] have also found increases in obesity prevalence among children during versus before COVID-19. However, these studies did not select children/adolescents with complex chronic conditions who may be more at risk for obesity-related morbidities. To address this research gap, we used electronic health record (EHR) data from an ongoing study of medication-induced weight gain. This study, the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) MedWeight Study [9], is examining the comparative effects of receiving prescriptions for five medication classes (for depression, psychosis, hypertension, diabetes, or epilepsy) on weight and metabolic outcomes over 5 years among children and adults. Because the data available included time periods before and after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, we had data available to examine COVID-19 pandemic-related changes in obesity and body mass index (BMI) among a population of children aged 5 to <20 years with selected chronic conditions who have been excluded from prior evaluations of pandemic weight change. We determined overall weight change as well as differences by age, gender, race, ethnicity, and class of medication prescribed.

METHODS

We conducted a longitudinal study using EHR data. Patients were included if they were prescribed one of five medication classes for depression, psychosis, hypertension, diabetes, or epilepsy at 15 health care systems in PCORnet (Supporting Information Table S1) [10]. The health care systems include academic and community hospitals as well as freestanding pediatric hospitals. Data were captured from EHRs and transformed into a standardized format, the PCORnet Common Data Model, which allows for data interoperability across sites; data were generated through a single statistical query that identified all patients receiving prescriptions for the included medication classes, using RxNorm codes along with demographics. RxNorm is the standardized coding system for identifying prescriptions, developed by the National Library of Medicine [11]. Institutional review boards of participating sites either approved the study or ceded to the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institutional Review Board.

We included 293,341 patients aged 5 to <20 years with available BMI measures from January 1, 2019, to March 31, 2021. After randomly selecting one BMI per patient in each month-year, we included 1,206,727 visits. Our outcomes were obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) and BMI z scores (BMI-z) based on age- and sex-specific Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reference data [12]. We used a longitudinal design to examine average obesity prevalence and BMI-z in each month from January 1, 2019, to March 31, 2021. To compare obesity prevalence and BMI-z differences during the pandemic (defined as June through December 2020) versus pre-pandemic (June through December 2019), we used generalized estimating equations for binary outcomes (with an identity link and binomial distribution to allow for estimation of prevalence differences) [13] and linear mixed-effects models, respectively, accounting for repeated measures within the same child. These models included a linear term for month, a binary indicator representing the periods before or during the pandemic, and a month-by-period interaction term. There was an initial dramatic decline in visit volume in March 2020, which rebounded by June 2020, although not to baseline (Supporting Information Table S2) [2]. As a result, we used June through December as comparison months. We ran models stratified by age, gender, race, ethnicity, and class of medication prescribed. Some patients (39%) were prescribed more than one medication class, and each medication class was coded as a dichotomous yes/no variable. Patients who were prescribed more than one class of medication were included in more than one of the medication-stratified models.

We performed several sensitivity analyses. First, we restricted the analytic sample to 94,022 patients with available BMI measures in both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods. Second, because there are some limitations to using CDC BMI-z for children with severe obesity, we examined severe obesity as a dichotomous outcome (defined as BMI ≥ 120% of the 95th percentile) [14, 15]. Third, we adjusted the overall age-stratified models for race, ethnicity, and class of medication prescribed rather than stratifying analyses by these variables. We analyzed data using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

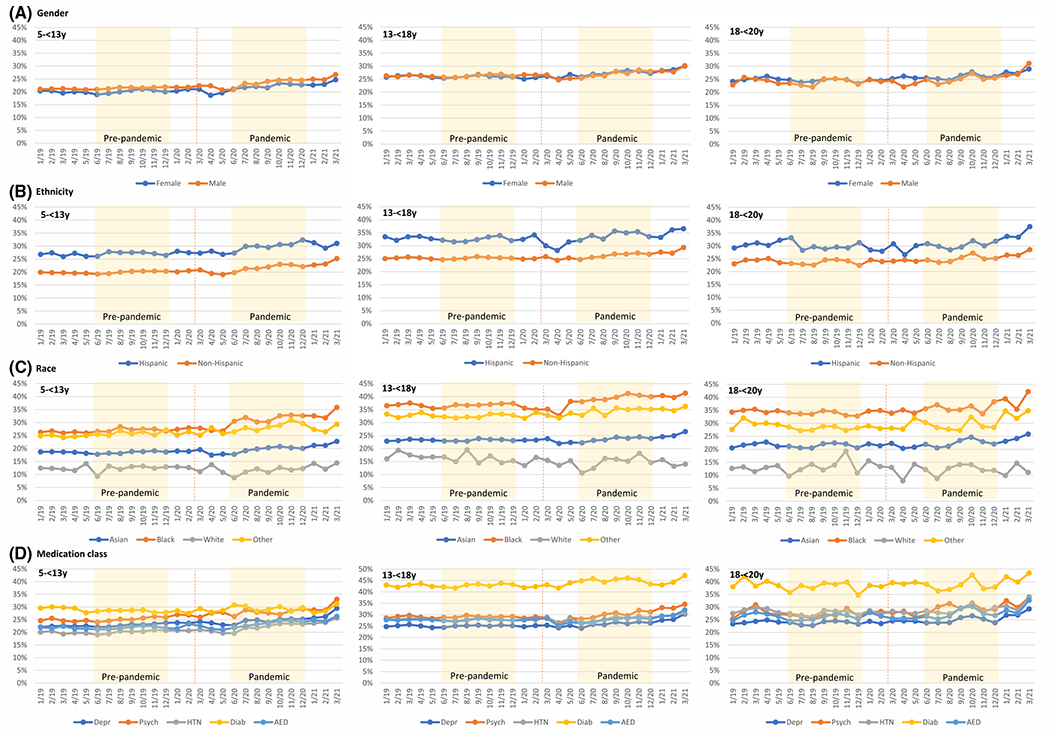

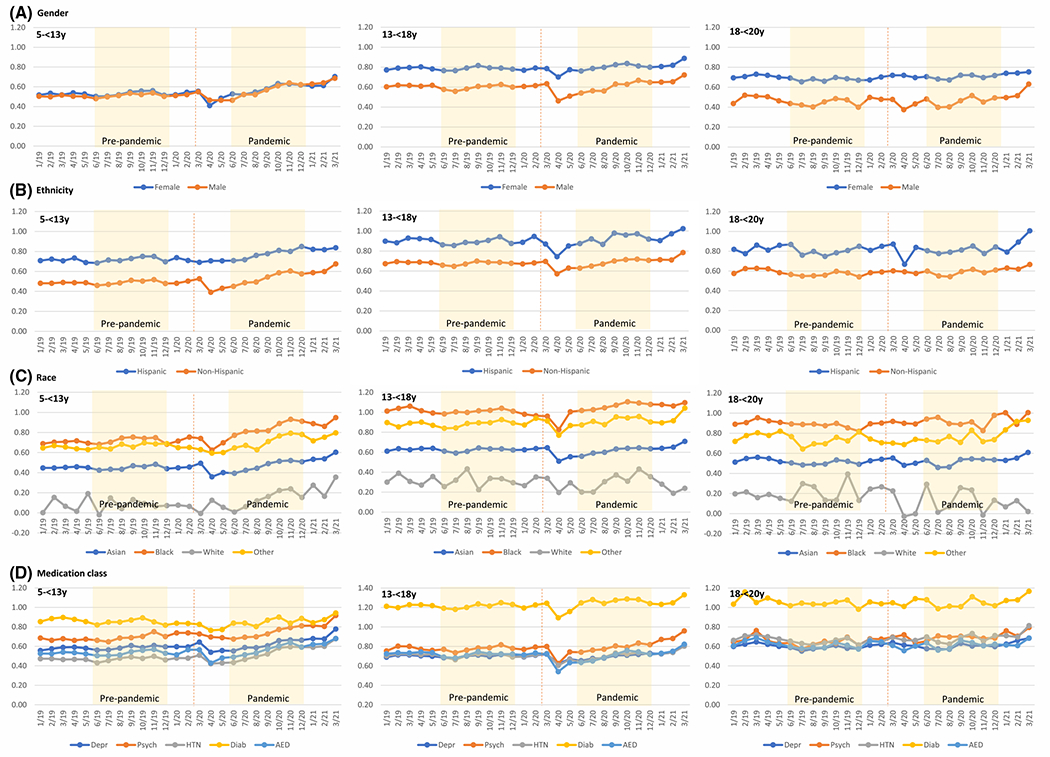

Among 293,341 included children, 51.6% were female, 12.7% were Hispanic, 2.0% were Asian, 16.5% were Black, 71.7% were White, and 9.8% were other races. Overall, obesity prevalence increased from 23.8% before the pandemic to 25.5% during the pandemic, and severe obesity prevalence increased from 10.7% to 11.8%; mean (SD) BMI-z increased from 0.62 (1.26) to 0.65 (1.29; Table 1). Between June 2019 and December 2020, the rate of obesity prevalence increased by 0.18% per month (95% CI: 0.09% to 0.28%) and 0.12% per month (95% CI: 0.03% to 0.21%) in children aged 5 to <13 and 13 to <18 years, respectively. At pandemic onset, there was a decline in obesity prevalence by 2.19% (95% CI: −3.75% to −0.63%) and 2.34% (95% CI: −3.79% to −0.89%) in children aged 5 to <13 and 13 to <18 years, respectively (Supporting Information Table S3), likely because of selection bias regarding who went for health care encounters in June 2020, which was still early in the pandemic. Obesity prevalence increased across almost all subgroups, with a larger rise among children aged 5 to <13 (0.27% per month; 95% CI: 0.11% to 0.44%) and 13 to <18 years (0.24% per month; 95% CI: 0.09% to 0.40%) during the pandemic (vs. pre-pandemic) and the largest increases were among children aged 5 to <13 years who were male (0.42% per month; 95% CI: 0.20% to 0.64%), Black (0.35% per month; 95% CI: −0.09% to 0.76%), or Hispanic (0.59% per month; 95% CI: 0.11% to 1.08%) or who were prescribed antihypertensive medications (0.28% per month; 95% CI: 0.07% to 0.50%; Figure 1 and Supporting Information Table S3). Similar results were noted for BMI-z (Figure 2). Based on estimates from the models and accounting for pre-pandemic trends, obesity prevalence in December 2020, for example, would have been 22.8% (95% CI: 21.7% to 23.8%) under the counterfactual that there was no pandemic versus 24.4% (95% CI: 23.8% to 25.0%) with the pandemic among 5- to <13-year-old individuals, 27.3% (95% CI: 26.3% to 28.3%) versus 28.3% (95% CI: 27.8% to 28.9%) among 13- to <18-year-old individuals, and 24.8% (95% CI: 23.0% to 26.6%) versus 26.4% (95% CI: 25.5% to 27.3%) among 18- to <20-year-old individuals.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics, overall (person-level) and by pre-pandemic (June through December 2019) vs. during the pandemic (June through December 2020) (visit-level)

| Overalla (person-level), n = 293,341 | Pre-pandemic (visit-level), n = 395,590 | During pandemic (visit-level), n = 261,096 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

|

| |||

| Male | 142,053 (48.4) | 192,835 (48.7) | 123,586 (47.3) |

|

| |||

| Female | 151,288 (51.6) | 202,755 (51.3) | 137,510 (52.7) |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity b | |||

|

| |||

| Non-Hispanic | 249,233 (87.3) | 338,802 (87.2) | 220,760 (86.4) |

|

| |||

| Hispanic | 36,417 (12.7) | 49,610 (12.8) | 34,691 (13.6) |

|

| |||

| Race b | |||

|

| |||

| Asian | 5390 (2.0) | 7823 (2.1) | 4972 (2.0) |

|

| |||

| Black or African American | 45,691 (16.5) | 62,987 (16.7) | 44,170 (17.8) |

|

| |||

| White | 198,193 (71.7) | 268,091 (71.1) | 171,977 (69.4) |

|

| |||

| Other | 27,210 (9.8) | 37,993 (10.1) | 26,809 (10.8) |

|

| |||

| Medication class | |||

|

| |||

| Epilepsy | |||

| No | 195,583 (66.7) | 257,225 (65.0) | 168,875 (64.7) |

| Yes | 97,758 (33.3) | 138,365 (35.0) | 92,221 (35.3) |

|

| |||

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 253,884 (86.5) | 331,495 (83.8) | 217,061 (83.1) |

| Yes | 39,457 (13.5) | 64,095 (16.2) | 44,035 (16.9) |

|

| |||

| Depression | |||

| No | 157,536 (53.7) | 204,692 (51.7) | 147,295 (56.4) |

| Yes | 135,805 (46.3) | 190,898 (48.3) | 113,801 (43.6) |

|

| |||

| Psychosis | |||

| No | 248,091 (84.6) | 326,621 (82.6) | 219,631 (84.1) |

| Yes | 45,250 (15.4) | 68,969 (17.4) | 41,465 (15.9) |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 173,143 (59.0) | 213,245 (53.9) | 141,529 (54.2) |

| Yes | 120,198 (41.0) | 182,345 (46.1) | 119,567 (45.8) |

|

| |||

| Age at BMI (y) c | |||

|

| |||

| 5 to <13 | 110,239 (37.6) | 152,814 (38.6) | 92,905 (35.6) |

|

| |||

| 13 to <18 | 142,190 (48.5) | 188,591 (47.7) | 127,463 (48.8) |

|

| |||

| 18 to <20 | 40,912 (13.9) | 54,185 (13.7) | 40,728 (15.6) |

|

| |||

| BMI ≥ 95th percentilec | |||

|

| |||

| No | 225,009 (76.7) | 301,320 (76.2) | 194,551 (74.5) |

|

| |||

| Yes | 68,332 (23.3) | 94,270 (23.8) | 66,545 (25.5) |

|

| |||

| Severe obesity c,d | |||

|

| |||

| No | 263,148 (89.7) | 353,310 (89.3) | 230,212 (88.2) |

|

| |||

| Yes | 30,193 (10.3) | 42,280 (10.7) | 30,884 (11.8) |

|

| |||

| BMI z score (units), mean (SD) c | 0.60 (1.26) | 0.62 (1.26) | 0.65 (1.29) |

Note: Data given as n (%) or mean (SD).

“Overall” means among patients in the MedWeight collaborative study prescribed one or more of the five medications of interest.

n = 16,857 missing values for race and n = 7691 missing values for ethnicity are not included in percentage.

We used first BMI and age in the overall column.

Severe obesity defined as BMI ≥ 120% of the 95th percentile based on CDC reference data.

FIGURE 1.

Obesity prevalence from January 2019 to March 2021 by age category and subgroups. Yellow-shaded areas represent the pre-pandemic (June through December 2019) and pandemic (June through December 2020) comparison time periods. The vertical dotted line is March 13, 2020 (date that COVID-19 was declared a national emergency in the United States)

FIGURE 2.

BMI-z from January 2019 to March 2021 by age category and subgroups. Yellow-shaded areas represent the pre-pandemic (June through December 2019) and pandemic (June through December 2020) comparison time periods. The vertical dotted line is March 13, 2020 (date that COVID-19 was declared a national emergency in the United States). BMI-z, BMI z score

Results were similar when restricting to those with BMI measures in both the pre-pandemic and pandemic periods (n = 94,022 children), as were results for severe obesity. Severe obesity prevalence increased across almost all subgroups, with a larger rise among children aged 5 to <13 years (0.20% per month; 95% CI: 0.09% to 0.32%) and 13 to <18 years (0.13% per month; 95% CI: 0.01% to 0.25%) during the pandemic (vs. pre-pandemic) and the largest increases among children aged 5 to <13 years who were male (0.25% per month; 95% CI: 0.09% to 0.40%) or Black (0.42% per month; 95% CI: 0.07% to 0.76%) or who were prescribed antihypertensive medications (0.20% per month; 95% CI: 0.05% to 0.35%; Supporting Information Figure S1, Supporting Information Table S4). Overall age-stratified results were similar when we adjusted for race, ethnicity, and medication class. For example, in these adjusted models among children aged 5 to <13 years, obesity prevalence increased 0.20% per month (95% CI: 0.04% to 0.36%), whereas, among children 13 to <18 years, obesity prevalence increased 0.23 per month (95% CI: 0.07 to 0.38) during the pandemic (vs. pre-pandemic).

DISCUSSION

In this large national sample of patients aged 5 to <20 years with selected chronic conditions, we found post-pandemic increases in obesity prevalence and BMI-z, especially among school-aged children of Black or Hispanic race/ethnicity or those who were prescribed antihypertensive medications. These results imply worsening metabolic health among children with selected chronic conditions, some of which are exacerbated by weight gain. Changes in obesity prevalence and BMI-z in this study among children with selected chronic conditions were similar to prior studies that have example general populations of children, excluding those with chronic diseases [2–5].

Our study had some limitations. Results are not generalizable to other populations without chronic conditions or with use of other medication classes or other chronic conditions. Our results could also be influenced by unmeasured confounding. For example, we did not have data on socioeconomic status, which is known to be associated with BMI in young childhood. Additionally, in-person visit volume was lower during the pandemic than during comparable months before the pandemic, suggesting potential selection bias. However, patient characteristics were comparable in each time period, and our findings were similar when we restricted to patients with BMI measures in both periods.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the childhood obesity epidemic and has widened disparities. These increases have the potential to have long-lasting consequences. Obesity during childhood creates risks for other chronic diseases during childhood as well as risks for obesity and chronic disease during adulthood. In December 2020, the American Academy of Pediatrics released guidelines to urge pediatricians to continue to screen, counsel, and treat obesity as it arises and to provide tailored strategies to families for healthy diets and physical activity during the pandemic [1]. Our findings highlight the importance of continuing these efforts and the need to specifically help high-risk populations (i.e., racial/ethnic minorities and those with chronic conditions) who are experiencing weight gain from the pandemic secondary to social and structural factors, including poverty, racism, and poor access to health care. Our findings, along with prior studies, also demonstrate the importance of closely monitoring weight and potential health consequences for children during societal events such as pandemics that might lead to the social isolation, decreased activity, poor nutrition, and mental health consequences that have been common during the pandemic [16, 17]. Some of these factors are almost certainly more prominent among children in our study, who entered the pandemic with preexisting medical problems, including mood and psychotic disorders and cardiometabolic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. Closely monitoring weight, both at the population and individual level, could facilitate more prompt interventions to mitigate weight gain. Children with selected medical conditions might benefit from this close monitoring more than the general population, considering their more frequent contact with the medical system than the general pediatric population.

Supplementary Material

Study Importance.

What is already known?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, children and adolescents have experienced increased stress, school closures, and less opportunity for physical activity and proper nutrition, all of which are risk factors for weight gain.

What does this study add?

Among children with selected chronic conditions, we found post-pandemic increases in obesity prevalence and BMI z score, especially among school-aged children of Black or Hispanic race/ethnicity or who were prescribed antihypertensive medications.

How might these results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the childhood obesity epidemic and has widened disparities among children with selected chronic conditions.

Our findings highlight the importance of monitoring and treating high-risk populations who may have experienced weight gain during the pandemic.

Future mitigation measures implemented among children to contain the spread of infection should consider the negative effect of weight gain.

Funding information

National Institutes of Health, Grant/Award Number: R01 DK120598

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics. American Academy of Pediatrics raises concern about children’s nutrition and physical activity during pandemic. Published December 9, 2020. Accessed December 10, 2021. http://services.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2020/american-academy-of-pediatrics-raises-concern-about-childrens-nutrition-and-physical-activity-during-pandemic/

- 2.Jenssen BP, Kelly MK, Powell M, Bouchelle Z, Mayne SL, Fiks AG. COVID-19 and changes in child obesity. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2021050123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-050123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolford SJ, Sidell M, Li X, et al. Changes in body mass index among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2021;326:1434–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu AJ, Aris IM, Hivert M, et al. Association of changes in obesity prevalence with the COVID-19 pandemic in youth in Massachusetts. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:198–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange SJ, Kompaniyets L, Freedman DS, et al. Longitudinal trends in body mass index before and during the COVID-19 pandemic among persons aged 2–19 years — United States, 2018–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1278–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UK Goverrnment. NCMP changes in the prevalence of child obesity between 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed June 20, 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-child-measurement-programme-ncmp-changes-in-child-bmi-between-2019-to-2020-and-2020-to-2021/ncmp-changes-in-the-prevalence-of-child-obesity-between-2019-to-2020-and-2020-to-2021

- 7.Vogel M, Geserick M, Gausche R, et al. Age- and weight group-specific weight gain patterns in children and adolescents during the 15 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Obes (Lond). 2022;46:144–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gwag SH, Oh YR, Ha JW, et al. Weight changes of children in 1 year during COVID-19 pandemic. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2021;35:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network. MedWeight study uses PCORnet to assess medication-Induced weight gain. Published October 5, 2020. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://pcornet.org/news/medweight-study-uses-pcornet-to-assess-medication-induced-weight-gain/

- 10.The National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network. PCORnet Common Data Model (CDM) Specification, Version 6.0. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://pcornet.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/PCORnet-Common-Data-Model-v60-2020_10_221.pdf

- 11.National Library of Medicine. RxNorm. Updated July 9, 2021. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/rxnorm/index.html

- 12.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital and Health Statistics, series 11, no. 246. National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005, 200;162:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman DS, Butte NF, Taveras EM, et al. BMI z-scores are a poor indicator of adiposity among 2- to 19-year-olds with very high BMIs, NHANES 1999–2000 to 2013–2014. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25:739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turer CB, Barlow SE, Sarwer DB, et al. Association of clinician behaviors and weight change in school-aged children. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57:384–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Min J, Xue H, Wang Y. Association between household poverty dynamics and childhood overweight risk and health behaviours in the United States: a 8-year nationally representative longitudinal study of 16 800 children. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13:590–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilfley DE, Staiano AE, Altman M, et al. Improving access and systems of care for evidence-based childhood obesity treatment: conference key findings and next steps. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25:16–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.