Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of the monetary policies in 3 countries (the Republic of Korea, China and the United States) on the Korean stock markets (e.g., KOSPI), using a structural Vector Autoregression. We find that a positive shock in Money Supply (M2) in all 3 countries is positive to the Korean stock markets but the degree of the response differs from one another. Surprisingly, the response of the KOSPI was largest to China’s M2, reflecting that China is Korea’s largest trading partner. From the responses of Korea’s industrial production and CPI, we speculate that a possibility of liquidity trap was not ruled out in some periods. We also find that the KOSPI responded negatively to a positive shock in Korea’s policy rate while it rarely responded to the shocks in the China’s policy rate and the US federal fund rate. We consider that China’s policy rate did not affect Korea’s economic activities as it was not a main monetary policy tool. We also consider that Korea’s determination of policy rate was not fully free from the US monetary policy and thus any shock in the US federal fund rate was substantially mitigated in the KOSPI.

Keywords: Structural VAR, Monetary policy, Korean stock market, Impulse response

Introduction

Despite recent disruptions in the global supply chain caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and trade conflicts between the US and China, globalization over the past decades has positioned the Korean economy as an essential part of the global economy. As a result, Korea’s trade with foreign countries is one of the most important components as evidenced by Korea’s trade-to-GDP ratio: it jumped 69.3% in 2000 to 109.6% in 2011, although it slightly dropped to 72.9% in 2020. In the process of globalization, the Korean economy has been often synchronized with its largest trading partners, e.g., US and China. This synchronization among these economies is even realized in the stock markets (Cho & Kim, 2011; Kim & Kim, 2009; Lee & Yu, 2018; Nam & Yuhn, 2001; Wang, 2016; among others). This synchronization, while beneficial during the expansion period, may pose some risks to the Korean economy because the effects of any financial or economic crises in one economy can be rather quickly transmitted.

One of the risks posed to the Korean economy, as the Korean economy is a comparatively small economy to its largest trading economies, is that of policy, particularly from monetary policies made in its trading partners. A change in the federal fund rate determined by the Federal Reserve System affects the US economy as well as the US stock markets. However, the impact of the change in the federal fund rate is not limited only to the US. As the Korean economy is more synchronized through globalization, the Korean economy is affected by the change in the federal fund rate.

Given this policy risk, it is important to clearly understand how monetary policy in Korea’s largest trading partners affects the Korean economy. Fortunately, there are extensive studies on the impact of US monetary policy on the Korean economy and financial markets (Kang et al., 2018; Nam & Lee, 2019). On the contrary, only a few studies on the impact of China’s monetary policy on the Korean economy have been made (Cho, 2021). A disparity in our understanding of China’s monetary policy and America’s monetary policy is not desirable. To tackle this disparity, this paper models a framework in which both nations’ monetary policies are included in the analysis of the policy influence on the Korean economy.

In this paper, however, a stock market is of our interest as the Korean stock market is the barometer of influences from any global events. For the past two decades, Korea’s ratio of its stock market valuation to its gross domestic product quadrupled, i.e., from 34.2% in 2000 to 123% in 2020. This increase reflects the globalization of the Korean firms as well as the openness of the stock market to the foreign investors. Partly due to this fact, the Korean stock market sensitively responds to global events. For this reason, we focus on the impact of monetary policy on a major Korean stock market: the KOSPI.

Literature review

An impact of monetary policy on the stock market has been studied in the transmission mechanism since the monetarists (e.g., Meltzer, 1995) argued that asset prices,1 e.g., stocks and houses, play a crucial role.2 Even if the stock market is an important channel of monetary policy (Chami et al., 1999), the study on the stock market channel has gained momentum since the late 1990s to answer if the stock market boom in the late 1990s was empirically caused by monetary policy. Most studies find that monetary policy caused the stock market boom. For some examples, Thorbecke (1997) and Patelis (1997), respectively, showed that an expansionary monetary policy led to an increase in stock prices and that restrictive monetary policy led to a decrease in stock prices. Lastrapes (1998) also demonstrated a significant impact of a monetary policy on the stock market not only in the US, but also in Europe and Japan. Roffia and Zaghini (2007) in their study for 15 industrialized countries showed that robust money growth is accompanied by large increases in stock price.

Given the stock market as an important channel of monetary policy, Campbell and Cochrane (1999) presented that a monetary policy changes the level of consumption that affects the expected profit of the firm and thus their share prices. Lettau and Ludvigson (2001) argued that the ratio of consumption to the aggregate wealth, including labor income, is important to the change in stock prices. Grabowski and Stawasz-Grabowska (2021) also found that the European Central Bank’s monetary policy also affected the equity markets of the Czech, Hungary, and Poland.

In the case of Korea, empirical results also produced similar results. For example, Shin (2003) showed that a shock in M2 increased the stock prices in the short run, but its impact disappeared in the long run as long-run money neutrality was imposed in the model. Park and Park (2013) showed that a change in M2 did affect KOSPI small-cap stocks although its impact on KOSPI large-cap stocks was very small.

Unlike monetary aggregates, e.g., M2, the empirical relationship between policy rate and stock prices seems to be more complicated, due to an endogenous response of monetary policy to the stock prices, as Rigobon and Sack (2003) argued. Despite the difficulty in the estimation coming from the simultaneous response of equity prices to interest rates, Rigobon and Sack (2003) showed that a 5% rise in the S&P 500 index increases the likelihood of a 25 basis point tightening by about a half. By utilizing the instrumental variables for the endogeneity, Rigobon and Sack (2004) further showed that an increase in short-run interest rates results in a decline in stock prices. Similarly, Bernanke and Kuttner (2005a, 2005b) measured that a stock price increases by 1% on the day when the federal fund rate is lowered by 25 basis points. However, they argued that there is no monthly change in the stock prices. D’Amico and Farka (2011) found that a tightening in policy rates has a negative impact on stock prices and that the Fed has responded significantly to movements in the stock market. The case of Korea also shows similar results: Jeong and Park (2015) demonstrated that policy rate and stock price had a negative relation, and this negative relation was robust to the extent that even inflation and US federal fund rate were included. Park and Park (2013) showed that a negative impact of policy rate on the stock market was larger when the stock market is in a bull market than in a bear market.

Empirical model

The Korean economy is relatively small compared to its two largest trading partners: the United States and China. In nominal terms, Korea’s GDP was $1.6 trillion in 2020, while US GDP was $20.9 trillion and China’s GDP was $14.7 trillion. Compared in nominal GDP, the Korean economy is only 11.7% to China’s economy and 7.8% further to the US economy. Given Korea’s relative size to China and US, we consider a structural equation to model the dynamics on the Korean economy by treating Korea as a small open economy that is influenced by the large economies, but does not influence the large economies;

| 1 |

where is the vector of variables for the large economies, i.e., China and US, is the vector of variables for the Korean economy, and . in and for j and k = 1 and 2, respectively, with lag operator L are the parameters and are the errors, capturing any factors that are not explained in the equations. The structural equation in (1) is relatively small in comparison with large-scale statistical macro-econometric models in analyzing economic relations. However, as Sims (1980) noted, the equation is not only simpler in the use of economic variables, but it is also credible in the identification of excluded variables.

We assume that errors in (1) are assumed to be zero mean, i.e.,, and homoscedastic in covariance, i.e., . Zero mean conveys that it is expected that any unexplained factors do not affect the variables in the equation and homoscedastic covariance means that it is expected that these unexplained factors are independent of each other. As our focus is to investigate the impact of monetary policies on the stock market in the Korean economy, we consider the following variables for the equation,

where Korean economic variables include Korea’s M2 and the Bank of Korea’s base rate.

However, the above structural equation cannot be directly estimated, as a matrix capturing the contemporary economic interactions within the structural equation is attached to the dependent variables, .

For this reason, we instead estimate the following reduced-form equations,

| 2 |

where for j, k = 1 and 2 are the matrices of coefficients to the economic variables of interest, . The errors in the reduced form capture any factors that are not explained in the equations. We assume that these unexplained factors do not affect the variables in the form, i.e.,, but are correlated each other, i.e., , as the contemporary economic relations among variables are not correctly captured in the reduced-form equation.

From the estimation of (2), we identify the parameters in and in the structural Eq. (1) as long as are identified;

| 3 |

and

| 4 |

However, identification from the above relations, i.e., (3) and (4), is not allowed unless we restrict on the coefficients of the matrix, as the number of the coefficients in the matrix is larger than the number of the coefficients estimated in the B matrices. Any restrictions on the matrix must be reasonable to economic theory or economic data.

Once and are identified from the reduced-form equation, it is possible to quantify how monetary policies affect the Korean stock market. To do this, we estimate the impulse response function from the structural Eq. (1) in the following moving-average forms,

| 5 |

where are a matrix polynomial in lag operator L. This is what we present in this paper.

Identification strategy

We develop a strategy to identify the matrix , where and , respectively, capture the contemporary monetary policies of China and the contemporary Korean economy (including the monetary policy in Korea). and 0 denote contemporary interactions among the monetary policies of China, the US, and the Korean economy.

Firstly, to identify , we consider the indicators of the monetary policies, i.e., M2 and policy rate, in the US and China while the two policies are independently determined. The divergence of two monetary policies seems obvious given trade conflicts between China and the US, varying policy responses to Covid-19, and differing domestic political dynamics (e.g., China’s recent focus on the doctrine of common prosperity). That is,

| 6a |

Secondly, to identify , we follow Kim (2003) to specify the Korean economic variables to which a stock index, i.e., KOSPI, is added.

| 6b |

Given the assumptions on and , i.e., each monetary policy is determined independently within its own economy,3 the estimation of the reduced-form Eq. (2) can be simplified, as proven by Hamilton (1994) and used by Lastrapes (2005, 2006) and Han et al. (2021). We lay out how is identified in this estimation; by this assumption, (2) can be rewritten as

| 7 |

From the relation between the structural equation and the reduced-form equation, i.e., (3) and (4), the covariance matrix in the estimation of (7) is now related to as seen below,

| 8 |

where , , , and . From (8), we find that the covariance matrix is symmetric and the product of the inverse matrix of and its transposition. With this information, where .

Once is identified, it is typical to recover a matrix polynomial in (5), i.e., , to find the impulse response function from the structural-form equation. For our interest, we quantify the change in the Korean stock index in response to the shocks in monetary policies.

Data

We use four variables to represent the monetary policies of China and the US, i.e., USM2, USFFR, China M2, and China r, the first three variables of which are obtained from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), and the last of which is obtained from the Bank of Korea’s Economic Statistics System. USM2 is seasonally adjusted M2 in the US, and USFFR is the Federal Reserve System’s target rate in the federal fund market. China M2 is China’s M2 that is not seasonally adjusted, while China r is the policy rate of the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). The People’s Bank of China targets a 1-year loan prime rate (LPR); that is, the average of the biggest 18 commercial banks’ loan prime rates in which the PBOC’s medium-term lending facility is based.

We choose 5 variables to specify the Korean economy: CPI, IP, r, M2, and FX. CPI is Korea’s consumer price index, which is set to be 100 in 2015, and IP is Korea’s industrial production index for all industries, which is also set at 100 in 2015. r is the Bank of Korea’s base rate, and M2 is Korea’s seasonally adjusted M2. The Bank of Korea’s base rate is a bid rate for its sales of 7-day repurchase agreements (RPs) that was adopted in 2008, and it targets a call rate in the interbank overnight money market.4FX is the Korean won’s exchange rate for one US dollar. All these data are obtained from the Bank of Korea’s Economic Statistics System.

Then, we collect Korea’s most comprehensive stock index—the KOSPI—from the Korea Exchange, which is the sole securities exchange operator in South Korea. KOSPI is the price index of all common stocks traded in the stock market division of the Korea Exchange for which the index was 100 in 1980.

All data are monthly (from the period of January 2001 to October 2020), and the summary of the data description is provided in the Appendix. With these collected data, we performed the augmented Dickey-Fuller unit root tests. As typically expected on the time series data,5 we could not reject the null hypothesis of being non-stationary. These results indicate that any static model would run into the spurious regression problem. Thus, these non-stationary data should be regressed with proper treatment of the dynamics, i.e., a use of lags of the dependent and explanatory variables as in vector auto-regressions (Enders & Doan, 2014).

As our interest is the impact of monetary policies on the Korean stock market, we plotted the monetary policy variables (i.e., M2 and policy rate) and the stock index in the following figures. Figure 1 shows the time trend of the KOSPI and its monthly fluctuations. As seen, the KOSPI more than quadrupled in two decades (from 530.27 in April 2001 to 2,357.82 in October 2020). The KOSPI suffered two significant drops during the period of interest after climbing to hit 2,000 in the mid-2000s. The first drop occurred mostly in 2008, when the aftermath of the Great Recession spread from the US to other countries. During this time, KOSPI dropped from 2,000.55 in October 2007 to 1,073.95 in November 2008. The second drop occurred mostly during the China–US trade conflict in 2019 and the Covid-19 pandemic starting in early 2020. However, the KOSPI was not too greatly affected by Covid-19 as the virus was successfully contained in Korea. In fact, KOSPI dropped from 2,533.51 in December 2017 to 1,786.75 in March 2020, but quickly bounced back to pre-pandemic levels. Between these drops, the KOSPI mostly went sideways, with its monthly fluctuation roughly within 5%.

Fig. 1.

KOSPI and its monthly fluctuation. KOSPI: The Korea Exchange (https://global.krx.co.kr/main/main.jsp)

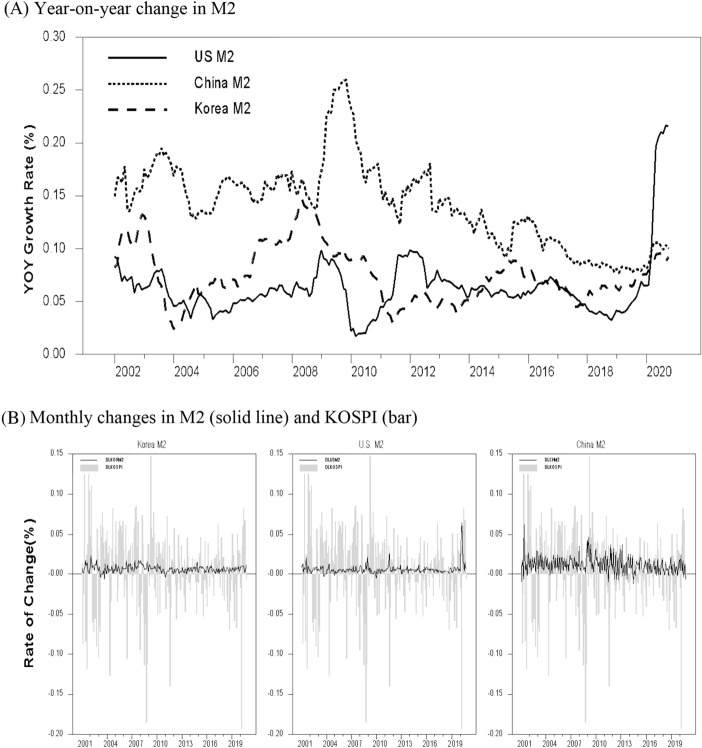

Figure 2 shows the changes in M2 and the KOSPI. The upper panel compares the year-on-year changes in M2 in all three countries. Note that the M2 growth rate in China overwhelms those of M2 in Korea and the US for the entire period of comparison, excepting the most recent years when US M2 jumped due to monetary stimulus from the Covid-19 pandemic. Another notable feature is that China’s M2 moved oppositely to those in Korea and the US in the time of the Great Recession. During this time, the growth of Korea’s M2 slowed down and deviated from the “seemingly” co-movement with the US M2. The lower panel compares the monthly changes in M2 and KOSPI. It is easily noticeable that China’s M2 fluctuated much more than the M2 in Korea and the US over the entire period of comparison, except the most recent period.

Fig. 2.

Changes in M2 and KOSPI. US M2: Federal Reserve Economic Data (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/). China M2: Federal Reserve Economic Data (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/). Korea M2: Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System (https://ecos.bok.or.kr/#/). KOSPI: The Korea Exchange (https://global.krx.co.kr/main/main.jsp)

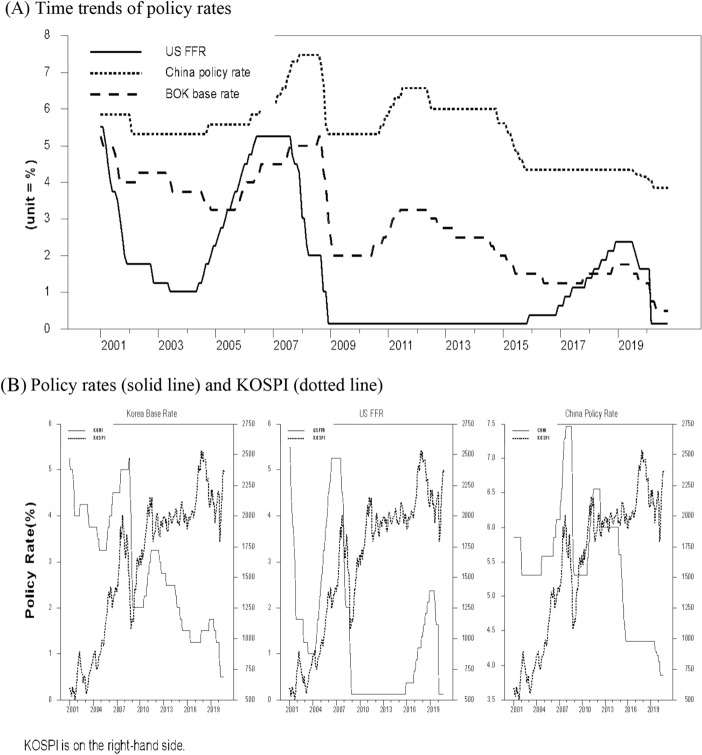

Figure 3 shows policy rates and the KOSPI. The upper panel compares the policy rates of the three countries; observe that China’s policy rate was highest at around 5–7% most of the time, while fluctuation was the smallest. To the contrary, the US federal fund rate was most volatile, ranging from 0.125 to 5.5%, while it had been 0.125% for six years (from December 2008 to November 2015). Finally, Korea’s policy rate was usually set between Chinese and American federal fund rates: the Bank of Korea attempted to keep its interest rates higher than those in the US in the hope of preventing foreign funds from flowing away. In addition to the level of policy rates, we noted that Korea’s policy rate deviated from the “seemingly” co-movement of the US federal fund rate and followed China’s rate during 2011–2015. Nonetheless, it must be clearly acknowledged that this deviation was made because the interest rate gap between Korea and the US was wide enough to solicit foreign cash flow to the Korean economy. The lower panel compares policy rates and the KOSPI, in which endogenous responses of policy rates are spotted in the graphs as Rigobon and Sack (2003) argued. The Bank of Korea raised the policy rate when the KOSPI climbed during 2004–2007 and then lowered the policy rate when the KOSPI plunged during 2007–2009. However, the KOSPI jumped as the policy rates in all 3 countries lowered in 2019. This observation indicates the complicated relation between policy rates and the stock market.

Fig. 3.

Policy rates and KOSPI. US FFR: Federal Reserve Economic Data (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/). China Policy Rate: Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System (https://ecos.bok.or.kr/#/). BOK Base Rate: Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System (https://ecos.bok.or.kr/#/). KOSPI: The Korea Exchange (https://global.krx.co.kr/main/main.jsp)

Empirical results on impulse response

Given the complicated relationships between monetary variables and the stock market, we have analyzed the impulse response of the KOSPI to the monetary shocks in 3 countries, i.e., Korea, the US and China, which should be correctly identified in the structural equation using the methods in the above section.

M2

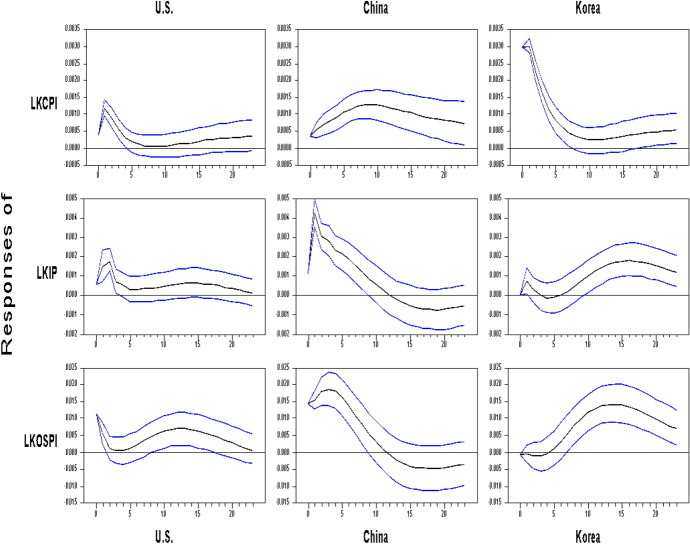

As Monetarist argued, the KOSPI increases in response to a positive shock in M2 not only in Korea, but also in China and the US. But the degree of the response of the KOSPI varies from country to country. Surprisingly, the KOSPI responded initially most to the shock in China’s M2 while it responded least to the shock in Korea’s M2 although the impact of Korea’s M2 on the KOSPI persisted up to 2 years. The response of the KOSPI to the US M2 was between China’s and Korea’s case.

Figure 4 shows the responses of the KOSPI to an increase in M2. From the figure, we note that an increase in China’s M2 lifts the KOSPI most, which is coupled with the increase in Korea’s industrial production. We contemplate that an increase in Korea’s industrial production results from the increase in Korea’s export to China when China’s economy is stimulated by the increase in China’s M2. But this effect is short-lived as the positive effect on industrial production and the KOSPI dies out within a year. Instead, Korea’s inflation, transmitted from the increase in China’s M2, is slowly built up and persists even after the positive effect on industrial production dissipated.

Fig. 4.

Impulse response to a shock in M2

For a positive shock in US M2, the KOSPI initially increases as expected. However, the response of the KOSPI to the shock was smaller than to the shock in China’s M2. We presume that the smaller response of the KOSPI to the shock in US M2 than to the shock in China’s M2 is related to Korea’s trade with these two countries. In fact, Korea’s exports to the US was counted for 23.9% of her total exports in December 2000, but shrank to 14.6% in October 2020. On the contrary, Korea’s exports to China was only 10.7%, but surpassed her exports to the US in July 2003 and further increased to 25.7% in October 2020. If Hong Kong is included into China’s trade, Korea’s trading volume with China is more than twice Korea’s trading volume with US. In this aspect, China’s economic fluctuation is crucial to the profits of many Korean firms and thus crucial to their stock values. Reflecting this influence, the response of Korea’s industrial production to a shock in M2 is smaller to US shock than to China’s shock.

On the contrary, an increase in Korea’s M2 does not instantaneously increase the KOSPI as well as Korea’s industrial production. Instead, it causes inflation instantaneously. We speculate that the phenomenon in which an increase in M2 increases the prices other than industrial production might indicate a liquidity trap in the Equation of Exchange framework. In fact, Korea’s ratio of M2 to its nominal GDP (1.1 and 1.6) is much higher than that of the U.S (0.47–0.84) in the period of analysis. Although the ratio of M2 to a nominal GDP is not a sole measure of excess liquidity, we cannot rule out the possibility of a liquidity trap in some periods in which an increase in Korea’s M2 would increase CPI more than production.6

This response of the KOSPI contrasts with an increase in M2 in China and the US where the increase would be transmitted via an increase in foreign demand, etc., which would lead to an increase in Korea’s exports. Despite the Korean stock market’s initial failure to respond to the increase in the M2, the KOSPI eventually increases as inflation subsides and industrial production increases.

Policy rate

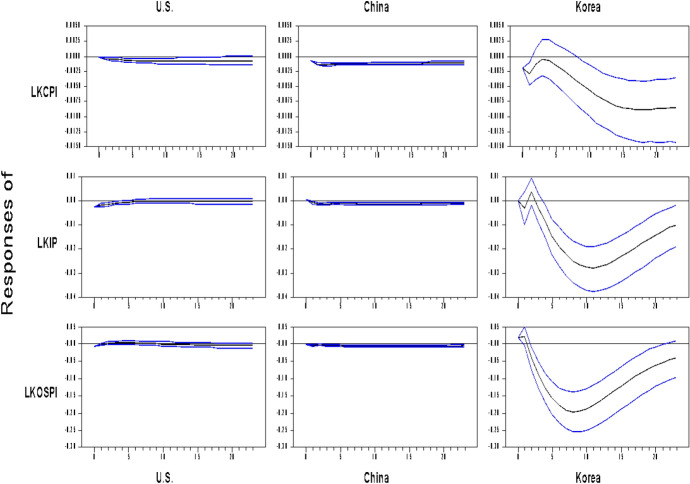

The response of the KOSPI to the positive shock in policy rates is contrasting: the KOSPI and other variables responded only to the shock in the Bank of Korea’s call rate, while the KOSPI hardly, or very minimally if any, responded to the shocks in US federal fund rate and in China’s policy rate.

As seen in Fig. 5, we find that a positive shock in Korea’s policy rate decreases Korea’s industrial production and CPI. As the economy cools down, the KOSPI increasingly declines as the impact of the rate increase accumulates. Note here that the KOSPI does not immediately decline when the policy rate increases. It takes 2–3 months for the KOSPI to finally drop. This delayed response may reflect the complicated, or endogenous if differently described, relation between the stock market and the policy rate.

Fig. 5.

Impulse response to a shock in policy rate

Contrary to Korea’s policy rate, US federal fund rate and China’s policy rate hardly, or very minimally if any, affects Korea’s main economic variables such as CPI, industrial production and KOSPI. This is striking and we need to figure out how this result comes out. We presume that the following two explanations contribute to the result.

First, for China’s shock, we consider that China’s policy rate, i.e., LPR, was not the effective monetary tool to change money supply up until 2019 and therefore any shock from China’s policy rate did not much affect the Korean economic activities. To see how ineffective China’s policy rate was to its money supply (e.g., M2), recall Figs. 2 and 3: the annual expansion of China’s M2 above 15% continued until 2010 even if the policy rate raised up to 7.47% in December 2007. Furthermore, the policy rate had been fixed at 4.35% for almost 4 years (October 2015–August 2019) even if there was a gap between the 1-year policy rate and the 1-year rates in the market. On August 17, the People’s Bank of China finally began to allow the policy rate to be fluctuated in accordance with the market rates. Given the limited role of China’s policy rate as a monetary tool, any shock in China’s policy rate did not much affect Korea’s economic activities.

Second, for US shock, we consider that the Bank of Korea’s determination of the policy rate was not fully free from US monetary policy. The Bank of Korea’s consideration of the US monetary policy in its determination of the policy rate can be found elsewhere, e.g., Bank of Korea’s quarterly reports, the press releases on its monetary policy decisions, etc. For example, the Bank of Korea raised its policy rate by 25 basis points, from 1.25% to 1.50% on November 30, 2017. In the press release, the Bank stated, “affected by factors such as the paces of monetary policy normalization in major countries, the directions of the US government’s economic policies, and the movements toward spreading trade protectionism” (Bank of Korea, 2017). Although there is no explicit expression in the Bank’s press releases or the reports, it is widely conceivable that the Bank attempts to maintain its policy rate higher than the US federal fund rate on the ceteris paribus assumption. By doing so, the Bank strives to prevent foreign funds from flowing out of the Korea economy. In fact, the Bank was urged to have a contingency plan to the rate increase in the US in its 2017 Inspection of the State Administration held on October 23, 2017 before the Bank actually raised its policy rate on November 30, 2017 (National Assembly of the Republic of Korea, 2018).

The Bank of Korea’s consideration of the US monetary policy implies that the impact of the change in the US federal fund rate targeted by the Federal Reserve System is substantially mitigated on the Korea economy as the Bank of Korea’s policy rate is presumptively determined in its expectation of the federal fund rate. This implication was consistent with what Kim and Shin (2010) found in their study of the relation of US monetary policy and Korea’s monetary policy and its impact on the Korean economy. Kim and Shin (2010) showed that Korea’s policy rate positively responded with a positive shock in the federal fund rate. As a result, they showed that the Korean stock market rarely responded to the same shock in the federal fund rate. This result was repeated in our research.

Conclusion

This paper investigated the impact of the monetary policies of the Republic of Korea, China, and the US on the Korean stock market (KOSPI). To investigate the impact, a structural VAR model was employed under the assumptions that (a) Korea is a small economy and (b) both China and the US independently make their own monetary policy. For the model, we identified the shocks by invoking a block exogeneity (Hamilton, 1994) while modeling the Korean economy developed in Kim (2003). In our investigation, we compared the impulse response of the KOSPI to the shocks in the monetary aggregates (i.e., M2) and the policy rates that the central banks targeted.

First, for a positive shock in M2, the KOSPI positively responded as Monetarists argued. But the degree of the response varied. Surprisingly, the KOSPI responded most to the monetary shock in China while it responded least to the shock in Korea although the response to the shock in Korea lasted most up to 2 years. The response of the KOSPI to a shock in US M2 was between two, Korea’s and China’s. From the response of Korea’s industrial production, we presume that Korea’s trade with China is the main reason for the largest response of the KOSPI to China’s M2. For the response of the KOSPI to Korea’s M2, we cannot rule out the possibility of liquidity trap in some periods, judging from the initial response of Korea’s CPI over Korea’s industrial production.

Second, for a positive shock in the policy rate, we observed that the KOSPI responded negatively to Korea’s policy rate while it hardly, or very minimally if any, responded to China’s policy rate and to the U.S. federal fund rate. For the China’s policy rate, we consider the lukewarm response of the KOSPI to be related to the point that China’s policy rate, i.e., LPR, was not the effective monetary policy tool to change money supply and thus a change in the rate did not much affect the Korean economic activities. For the US federal fund rate, we consider that the Bank of Korea’s determination of the policy rate was not fully from US monetary policy and thus any impact from the shock in the US federal fund rate was substantially mitigated in the KOSPI as Korea’s policy rate positively and preemptively responded to the shock in the US rate.

Given Korea’s trade with China and the US, we expect that the monetary impacts that we investigated will continue to be dominant in the near future. Given these monetary impacts, we would consider the following policy implications. First, the Bank of Korea, a monetary authority in Korea, must be mindful of a liquidity trap. For this aspect, a monetary policy must be focused more on the stability of financial systems rather than stimulating an economy. The stability of financial systems is especially important when a monetary tightening is required to tackle the current inflation. To secure this stability, a central bank needs to enhance its monitoring of the settlement system as well as financial institutions and its communication channel with the public. Second, a main role of stimulating an economy must be given to the fiscal policy. However, a simple stimulation of an economy is not desirable. Given the rising government debt, any fiscal policy must be more focused on the long-term change in Korea’s economic structure toward future industries, e.g., semiconductor, A.I., biotechnology, etc., as well as the reduction of income inequality that may rise from the structural changes.

Appendix: Data description and source

| Variables | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| USM2 | US M2 (US$, Seasonally Adjusted) | Federal Reserve Economic Data |

| USFFR | Federal Reserve Target Rate (%) | Federal Reserve Economic Data |

| China M2 | China’s M2 (CNY, Not Seasonally Adjusted) | Federal Reserve Economic Data |

| China r | People’s Bank of China’s Policy Rate (%) | Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System |

| KCPI | Korea’s Consumer Price Index (2015 = 100) | Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System |

| KORIP | Korea’s Industrial Production Index—All Industry (2015 = 100) | Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System |

| BOK r | Bank of Korea’s Base Rate | Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System |

| KORM2 | Korea M2 (KRW, Average, Seasonally Adjusted) | Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System |

| USFX | Exchange Rate (US Dollar to Korean Won) | Bank of Korea Economic Statistics System |

| KOSPI | Price Index of All Common Stocks Traded in the Stock Market Division of the Korea Exchange (1980 = 100) | The Korea Exchange |

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Besides the asset prices, there are studies focusing on the role of other economic variables, e.g., interest rates, exchange rates, banks, etc., in the monetary policy. Avci and Yucel (2017) provide a good summary of the role of interest rates and show this case for Turkey. For the role of exchange rates, refer to Mishkin (2008). For the role of banks, refer to Amar (2022).

Additional literature studying the relationship between stock prices and monetary variables is capital asset pricing model in that the asset price is determined by the present value of expected returns in the future. Hofmann (2001) and Goodhart and Hofmann (2004) showed that an increase in M2 lowers interest rates that raise the expected returns in the future and thus the asset price increases.

This assumption is explained by block exogeneity, which means that each block is independently determined when each policy is regarded as a block.

Call rate is a Korean version of the federal fund rate. Prior to 2008, the Bank of Korea directly targeted a call rate as the Federal Reserve System.

In fact, there are some, e.g., Hyundai Research Institute and former Bank of Korea governor Park, etc., who argued that the Korean economy is already in the liquidity trap. Yet, there is only one scholarly article which empirically supports the liquidity trap. That is, Kim (2017) in the estimation of the demand for money using Monte Carlo Markov Chain showed that Korea’s estimated interest rate is 0.543, indicating a liquidity trap.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yongseung Han, Email: yongseung.han@ung.edu.

Myeong Hwan Kim, Email: kimm@pfw.edu.

References

- Amar AB. On the role of Islamic banks in the monetary policy transmission in Saudi Arabia. Eurasian Economic Review. 2022;12(1):55–94. doi: 10.1007/s40822-022-00200-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avci SB, Yucel E. Effectiveness of monetary policy: Evidence from Turkey. Eurasian Economic Review. 2017;7(2):179–213. doi: 10.1007/s40822-017-0068-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Korea. (2017). Press Release on the Monetary Policy Decision. https://www.bok.or.kr/eng/bbs/E0000627/view.do?nttId=233291&menuNo=400022&pageIndex=4. Accessed 10 June 2022

- Bernanke BS, Kuttner KN. The study on the monetary policy and stock price in Korea. Journal of Industrial Economics and Business. 2005;28(6):2543–2564. [Google Scholar]

- Bernanke BS, Kuttner KN. What explains the stock market’s reaction to Federal Reserve policy. Journal of Finance. 2005;60(3):1221–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00760.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JY, Cochrane J. By force of habit: A consumption-based explanation of aggregate stock market behavior. Journal of Political Economy. 1999;107(2):205–251. doi: 10.1086/250059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chami, R., Cosimano, T. F., & Fullenkamp, C. (1999). The stock market channel of monetary policy. IMF Working Paper. 99/22.

- Cho, Y. (2021). Impact of a change in China’s monetary policy on the Korean economy. Bank of Korea Issue Note, 2021–19.

- Cho EJ, Kim TH. Impact of structural shock and estimation of dynamic response between variables. Korean Journal of Applied Statistics. 2011;24(5):799–807. doi: 10.5351/KJAS.2011.24.5.799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico S, Farka M. The Fed and the stock market: An identification based on intraday futures data. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics. 2011;29(1):126–137. doi: 10.1198/jbes.2009.08019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders W, Doan T. RATS Programming Manual. 2. Estima; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goodhart C, Hofmann B. Deflation, credit, and asset prices’. In: Burdekin RC, Siklos PL, editors. Deflation. Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski W, Stawasz-Grabowska E. How have the European central banks’ monetary policies been affecting financial markets in CEE-3 countries? Eurasian Economic Review. 2021;11(1):43–83. doi: 10.1007/s40822-020-00160-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JD. Time series analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Kim MH, Nam E. Investigating the interaction between terms of trade and domestic economy: In the case of the Korean economy. Journal of Korea Trade. 2021;25(1):34–46. doi: 10.35611/jkt.2021.25.1.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, B. (2001). The determinants of private sector credit in industrialized countries: do property prices matter? BIS Working Papers (December).

- Jeong, S., & Park, S. T. (2015). The study on the monetary policy and stock price in Korea. Journal of Industrial Economics and Business,28(6), 2543–2564

- Kang, T. S., Kim, K., Suh, H., & Kang, E. (2018). The US monetary policy normalization: the impact on Korean financial market and capital flow. Korea Institute for International Economic Policy -Policy Analysis, 18–04.

- Kim H. The liquidity trap estimation via MCMC approach: Korea and Japan study. Review of Institution and Economics. 2017;11(3):153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Monetary policy, foreign exchange intervention, and the exchange rate in a unifying framework. Journal of International Economics. 2003;60(2):355–386. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1996(02)00028-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Shin K. Globalization of capital markets and monetary policy independence in Korea. KDI Journal of Economic Policy. 2010;32(20):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Jo G. With regard to local contents rule (non-tariff barriers to trade): After announcing the Shanghai-Hong Kong stock connect, is the Chinese capital market suitable for Korean investors? Journal of Korea Trade. 2019;23(7):147–155. doi: 10.35611/jkt.2019.23.7.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Jo G. The impact of foreign investors on the stock price of Korean enterprises during the global financial crisis. Sustainability. 2019;11(6):1576. doi: 10.3390/su11061576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Kim SA. A study on US–Asia stock price co-movement and volatility spillover effects. Journal of Industrial Economics and Business. 2009;22(4):1621–1640. [Google Scholar]

- Lastrapes WD. The dynamic effects of money: Combining short-run and long-run identifying restrictions using Bayesian technique. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1998;80(4):588–599. doi: 10.1162/003465398557852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lastrapes WD. Estimating and identifying vector autoregressions under diagonality and block exogeneity restrictions. Economics Letters. 2005;87(1):75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2004.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lastrapes WD. Inflation and the distribution of relative prices: The role of productivity and money supply shocks. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking. 2006;38(8):2159–2198. doi: 10.1353/mcb.2007.0003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., & Yu, B. (2018). What drives the stock market comovements between Korea and China, Japan and the US? Bank of Korea Economic Analysis, 2018–2.

- Lettau M, Ludvigson S. Consumption, aggregate wealth, and expected stock returns. Journal of Finance. 2001;56(3):815–849. doi: 10.1111/0022-1082.00347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer AH. Monetary, credit and (other) transmission processes: A monetarist perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1995;9(4):49–72. doi: 10.1257/jep.9.4.49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishkin, F. S. (2008). Exchange rate pass-through and monetary policy. NBER Working Paper 13889. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Nam D, Lee JH. A small open economy DSGE model as a policy tool to analyze the effects of the US monetary policy and its estimation. Journal of Korean Economics Studies. 2019;37(4):5–59. doi: 10.46665/jkes.2019.12.37.4.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nam JH, Yuhn KH. Volatility spillover effects from the US stock market to the Korean stock market. Kukje Kyungje Yongu. 2001;7(3):23–45. [Google Scholar]

- National Assembly of the Republic of Korea. (2018). 2017 inspection report by the strategy and finance committee. https://committee.na.go.kr:444/finance/inspect/inspect02.do?mode=view&articleNo=655307&article.offset=0&articleLimit=10. Accessed 10 June 2022

- Park HD, Park HG. Measuring the transmission of monetary policy on the stock market. Journal of Industrial Economics and Business. 2013;26(4):1587–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Patelis AD. Stock return predictability and the role of monetary policy. Journal of Finance. 1997;52(5):1951–1972. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb02747.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rigobon R, Sack B. Measuring the reaction of monetary policy to the stock market. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2003;118(2):639–669. doi: 10.1162/003355303321675473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rigobon R, Sack B. The impact of monetary policy on asset prices. Journal of Monetary Economics. 2004;51(8):1553–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoneco.2004.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin W. Analysis of the stock market channel of monetary policy. Bank of Korea Monthly Bulletin. 2003;April:24–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sims CA. Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica. 1980;48(1):1–48. doi: 10.2307/1912017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorbecke W. On stock market returns and monetary policy. Journal of Finance. 1997;52(2):635–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb04816.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P. The asymmetric volatility and correlations between Korean, Chinese and American stock markets. Industrial Studies. 2016;40(1):53–79. [Google Scholar]