Abstract

Although many countries engage in public diplomacy, we know relatively little about the conditions under which their efforts create foreign support for their desired policy outcomes. Drawing on the psychological theory of “insincerity aversion,” we argue that the positive effects of public diplomacy on foreign public opinion are attenuated and potentially even eliminated when foreign citizens become suspicious about possible hidden motives. To test this theory, we fielded a survey experiment involving divergent media frames of a real Russian medical donation to the U.S. early in the COVID-19 pandemic. We find that an adapted news article excerpt describing Russia’s donation as genuine can decrease American citizens’ support for sanctions on Russia. However, exposing respondents to information suggesting that Russia had political motivations for their donation is enough to cancel out the positive effect. Our findings suggest theoretical implications for the literature on foreign public opinion in international relations, particularly about the circumstances under which countries can manipulate the attitudes of other countries’ citizens.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11109-022-09849-4.

Keywords: Public diplomacy, Media framing, National images, Foreign public opinion, Russia, United States, COVID-19, Health diplomacy

Introduction

Many governments increasingly engage in so-called public diplomacy to communicate with citizens in targeted countries. Activities in this area include social events and press conferences during leaders’ diplomatic visits, cultural and educational exchange programs, and humanitarian assistance with purposeful information campaigns, among others. But do these diplomatic efforts successfully sway the attitudes of citizens in targeted countries? When do these changes, if any, occur in the direction that the campaigning government intends? Under what circumstances do they occur unexpectedly in the opposite direction? Despite the prevalence of public diplomatic campaigns, we have little empirical evidence about the degree to which and conditions under which countries succeed in changing foreign citizens’ foreign policy preferences.

In this paper, we contribute to the literature on public diplomacy and, more broadly, the literature on foreign public opinion in international relations. Specifically, we examine public diplomacy in the context of a Russian medical donation to the United States early in the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent media response.1 On April 1, 2020, a Russian military-transport plane landed in New York with supplies such as ventilators and personal protective equipment.2

Using this case, we cast light on an under-investigated and theoretically important stage of public diplomacy. Specifically, we are interested in the consequences of how the media of a targeted country frames a foreign country’s motives. Does the media facilitate or impede that foreign country’s influence on policy preferences in the targeted country? Understanding the impact on foreign public opinion via media framing is important because ordinary citizens learn about and develop images of foreign countries, leaders, and policies primarily through news media. When a foreign country launches a public diplomacy campaign, it is partly the targeted country’s media that informs its citizens about the foreign country’s words and actions. The media literally “mediates” states’ transnational communication efforts, which may sway foreign public opinion.

Importantly for our research, Russia’s show of support was received with suspicion by American experts and media, who speculated about hidden motives. While some praised Russia for their assistance, others condemned Russia for presumably exploiting American tragedy for strategic gain. As a result, Americans were exposed to different types of coverage about Russia’s donation. This situation provided an opportunity to examine how different frames affect public opinion using actual (versus fabricated) news articles.

To investigate the effects of different frames, we draw on social and political psychology literature that examines “insincerity aversion” (e.g., Fein et al., 1990; Fein & Hilton, 1994; McGraw et al., 2002; Major et al., 2016). In the context of our research, insincerity aversion suggests that any positive effects of public diplomacy on foreign public opinion will be attenuated or possibly eliminated when foreign citizens are introduced to suspicions about the motives behind another country’s public diplomacy.

We test this theory by conducting a survey experiment on a national quota-based sample of 2814 American adults. We find that a sincere Russian donation substantially decreases support for sanctions: targeted audiences reward sincerity by supporting policy that favors the donor country. But information suggesting that the donation is insincerely motivated cancels out the positive effect of Russia’s charity. Our findings have theoretical implications for the literature on foreign public opinion in international relations, particularly about the circumstances under which countries can manipulate the attitudes of other countries’ citizens.

Foreign Public Opinion in International Relations

Before specifying our hypotheses, we discuss broader theoretical debates about foreign public opinion in international relations. Important questions for our work are (i) whether foreign public opinion matters, (ii) whether a country can change foreign public opinion, and (iii) what role the media plays, if any, in shaping foreign public opinion.

Does Foreign Public Opinion Matter?

Traditionally, international relations theorists maintain that a state’s foreign policy is best understood in terms of system factors, rational choice propensities, or national interests and capabilities (Bueno de Mesquita, 1982; Morgenthau, 1973; Stein, 1990; Waltz, 1979). According to this view, foreign public opinion does not influence foreign policy outcomes. These theorists believe that image management campaigns are not credible, do not bring about concrete benefits, or are merely a performance for domestic audiences (Edelstein & Krebs, 2005; Darnton, 2020; Hoffman, 2002) and they thus dismiss the role that public diplomacy plays in international relations (Cohen, 2017).

However, Herrmann and Fischerkeller (1995) propose theoretical relationships between different stereotypical images of foreign countries and states’ strategic “scripts,” sets of interrelated actions (Abelson, 1976): enemy images induce containment scripts, ally images induce institutional cooperation scripts, degenerate images induce revisionism scripts, and so on. Empirically, Shimko (1991), in studying the Reagan administration’s arms control policy, finds that those with enemy images of the Soviet Union held the most hostile policy preferences to the USSR. Experimentally, Herrmann et al. (1997) show that increasing negative affect strengthens the enemy image and induces support for aggressive policies. Other studies, like Cottam (1977), Cottam (1994), and Herrmann (1985), use cases spanning the U.S., U.K., Egypt, and Latin America to demonstrate how national images explain when the U.S. intervened (e.g., Guatemala in 1954) and when it did not (e.g., Bolivia in 1952). More generally, Goldsmith and Horiuchi (2012) show that attitudes toward the U.S. among foreign citizens predict those countries’ observable behavior, such as military deployment or UN General Assembly votes.

Can a Country Change Foreign Public Opinion?

These studies suggest that public opinion about, and images of, foreign countries matters for foreign policy. But they do not necessarily suggest that countries can change foreign citizens’ attitudes or policy preferences. The dominant view is that countries cannot easily change pre-existing images. The logic underlying this “image theory” is that individuals’ pre-existing images bias how they update their understanding of the international environment: they may selectively search for confirmatory information, selectively accept confirmatory information, or discount contradictory information (Hopf, 2010; Jervis, 1976; Tetlock, 1999).

Among various categorizations of national images, one of the most prevalent is the “enemy image” (Boulding, 1956; Finlay et al., 1967; Holsti, 1967) or “diabolical-enemy image” (Cottam, 1977; White, 1965). These negative images are understood as particularly difficult to change (Holsti, 1967). People who hold an enemy image of a country expect aggressive behavior or deception and, even if the country behaves positively, “evoke conspiracy theor[ies] to explain unanticipated positive moves on the other side’s part” (Herrmann 2003, and Jervis 1970).3 Taken together, “inherent bad-faith models” (Kissinger, 1961) appear to doom countries who hope to change foreign audiences’ priors.

However, some empirical studies show that countries can change public opinion abroad in desirable and expected ways, under certain conditions (Andrabi & Das, 2017; Blair et al., 2022; Goldsmith et al., 2014, 2021; Mattingly & Sundquist, 2022). Specifically, recent work suggests that countries’ ability to increase soft power via foreign aid (or other public diplomacy campaigns) and to change foreign public opinion depends on: whether targeted citizens (1) are aware of the campaigning country’s goodwill, (2) correctly attribute that goodwill to the campaigning country, and (3) perceive themselves as beneficiaries of that goodwill (Blair et al., 2022).

We find this work compelling and suggest an additional condition: (4) whether targeted citizens are convinced that the campaigning country is sincere. In a later section, we present our hypotheses for when images can be changed. But we first discuss the key theoretical mediator in the process of countries’ public diplomacy shaping foreign public opinion—the media.

What Role Does the Media Play?

As noted earlier, the most common source from which citizens hear about other countries’ statements and actions is the media.4 Given this, we are interested in whether states can change public opinion in a targeted country and what role the targeted country’s domestic media plays in blocking or facilitating such public diplomacy.5

Baum and Potter’s (2008) “marketplace framework” is helpful for understanding this relationship between the media, foreign policy, and public opinion. In this framework, the media defers to the public for demand: the public is their consumer.6 The public, however, “does not typically demand to be informed about foreign policy” (p. 53).

The media also has limited incentives to report stories about adversaries’ foreign policy that challenge news consumers’ pre-existing perceptions of those adversaries. Entman (2003) notes that the media is least likely to push culturally incongruous frames.7 Similarly, Sheafer et al. (2014) argue that public diplomacy efforts are more likely to succeed between countries that share values. Essentially, while the aforementioned “inherent bad-faith models” say people are unmotivated to update negative beliefs, existing studies further explain that the media gives the public little information that might encourage them to do so.

Furthermore, the media is not only incentivized against providing frames that challenge images but also biased towards stories that antagonize public opinion against foreign countries. For example, Brutger and Strezhnev (2022) show that, in both the U.S. and Canada, newspapers cover disputes filed against their own country rather than disputes filed by home country firms. Such biased story selection is part of a larger pattern, where media portrayals of issues involving other countries often (though not always) reinforce their domestic audience’s negative perceptions (Guisinger, 2017).

But in a global information age (Simmons, 2011), such a stylized description of consumers (with limited interest in foreign affairs) and the media (with limited incentives to report challenging news) may be insufficient. Today, people are exposed to numerous platforms, including social media, that are diverse in slant and volume. In the context of Russia’s medical donation to the U.S., some stories highlight Russia’s sincere motives, while others presume hidden motives (see examples in Section A of the Supplementary Materials). Interactions between news consumers and a growing number of news suppliers are considerably heterogeneous today.

Foreign countries may have increasingly limited control over how their diplomatic activities are framed by targeted countries’ media. Most Americans have moderate media diets, with few in so-called “echo chambers” (Dubois & Blank, 2018; Guess, 2021), and targeted citizens today are presented with differently framed accounts of how to interpret other countries’ actions. But how do such divergent media frames influence foreign public opinion? To our knowledge, there is limited evidence on this question. One recent exception examines how perceived motives of donor countries affect public opinion in recipient countries (Alrababa’h et al., 2020).8 But unlike their case, which examines the European Union’s or Russia’s foreign aid in Donbas in eastern Ukraine, we focus on a case where shifting opinion should be particularly challenging: one where a major power (i.e., Russia) attempts to influence public opinion in a longtime rival state (i.e., the United States).9

Perceived Motives of Public Diplomacy

Pew Research Center’s 2019 Global Attitudes Survey reveals that American views of Russia are “at their lowest point in more than a decade” (Huang & Cha, 2020). But major powers may still be able to shift foreign public opinion in rival states, depending on how their actions are framed.

In this section, we present our first hypothesis about the impact of humanitarian assistance on public opinion. Then, building on the theory of “insincerity aversion,” we present our second hypothesis about a context in which the effect of humanitarian assistance might be attenuated.

Appreciation of Sincerity

People seem to have a powerful, latent resistance to updating their images of other countries, particularly if those images are enemy images. But some countries do become more popular abroad following diplomatic action. Humanitarian assistance, for instance, seems like one way to sway foreign public opinion. Past studies (Goldsmith et al., 2014; Andrabi & Das, 2017) and polls (Terror Free for Tomorrow, 2006; Wike, 2012) show that foreign aid addressing epidemics (e.g., HIV/AIDS) or natural disasters improves donor countries’ images in recipient countries. Politicians also operate under the impression that aid works: then-Secretary of State Colin Powell, for example, expressed that post-disaster aid to Jakarta was “an opportunity [for Indonesians] to see American generosity, American values in action...[and dry up] pools of dissatisfaction” (The Economist, 2005).

Blair et al. (2022) theorize that foreign aid can increase donor countries’ soft power through “a process of exposure, attribution, affect and ideological alignment” (p. 1355). If they are to adopt a more positive view of a donor country, targeted citizens must first learn about donor-funded projects and accurately attribute benefits to the donor. In other words, aid’s efficacy in increasing soft power depends on the number of beneficiaries, how much attention it receives, and the type of attention it receives. Donating scarce medical resources during a pandemic, then, should be particularly effective in bolstering soft power.

Existing studies also suggest that national images become pliable during “dramatic events,” such as the high-profile diplomatic discussions between the U.S. and USSR in the late 1980s (Jervis, 1976; Peffley & Hurwitz, 1992). Such an event provides an “enabling environment” (Nye 2008, p. 90) for states to change their national images. Mattingly and Sundquist (2022), in related work, use the as-if random timing of a battle between China and India to advance the slightly different but related argument that China’s messages emphasizing generosity and friendship are effective despite the crisis.

Image changes may become even easier if the targeted country’s leaders appear supportive of a revised image. Peffley and Hurwitz (1992), citing Jervis (1976), write that cognitive stickiness becomes “increasingly ineffectual when new information is... consensually interpreted by opinion leaders.” Recently, Pan et al. (2021) show that frames designed by government elites can overcome individual predispositions and persuade the public to adopt the regime’s new policy position.10 In short, dramatic events, positive frames, and favorable interpretations circulated by the media appear to give states the window they need to improve their image abroad.

This logic and prior evidence lead to our Sincerity Hypothesis. As long as the media frames states’ actions as sincere, people update their opinion of the rival state:

- Sincerity Hypothesis:

When a foreign country’s international assistance is framed as sincerely motivated, foreign policy attitudes toward the donor country become more favorable among the recipient public.

Note “sincerity” does not denote diplomacy completely devoid of self-interest. Rather, we use it to describe good faith scenarios where a country’s actions are (reportedly, by the media) motivated at least in part by humanitarianism.

Aversion to Insincerity

However, negative frames—ones that speculate about foreign countries’ ulterior motives—might limit the persuasive power of assistance. Individuals are naturally averse to insincerity (e.g., Hibbing & Alford, 2004; McGraw, 2003; Robison, 2021). For example, politicians who appear to pander receive more negative evaluations (McGraw et al., 2002). This aversion persists even when citizens get divergent explanations for a politician’s behavior; explanations that highlight possible ulterior motives outweigh positive justifications for the politician’s behavior, regardless of information credibility (Robison, 2021). Social psychologists find a similar aversion in relationships between individuals (Fein et al., 1990; Fein & Hilton, 1994; Kunstman et al., 2016; Mayo, 2015; Major et al., 2016). Fein and Hilton (1994) demonstrate that suspicions based on contextual information can induce perceivers to see actors in a more negative light, even if they cannot be sure whether the actor truly harbors ulterior motives.

We reason that this aversion to insincerity extends beyond individual interactions to individual perceptions of state interactions. Citizens’ evaluations of countries may be similarly influenced by suspected insincerity, even when divergent frames emphasizing positive motives are available. More generally, Nye (2008) argues that foreign “policies that appear as narrowly self-serving or arrogantly presented are likely to prohibit rather than produce soft power” (p. 102).

Importantly, we expect that the media plays an essential role in this process. Specifically, our second hypothesis is that:

- Insincerity Hypothesis:

The effect of international assistance is attenuated if citizens are exposed to frames that suggest the country’s motives are insincere.

This type of framing could be particularly persuasive when negative sentiments are attributed to experts and political officials.11 In fact, such elite-level debates about the sincerity of state actions through public diplomacy have high stakes. Political leaders often declare the sincerity of their own country’s support for targeted countries to increase their country’s credibility in the eyes of foreign citizens (2008, p. 100). In response, other leaders suggest that rival countries’ foreign policy actions are insincere. For example, the U.S. Secretary of State denounced Beijing’s extensive vaccine diplomacy in Latin America as “deeply unfortunate” political ploys made with people’s health.12

Research Design

To test our two hypotheses, we fielded a pre-registered survey experiment from August 10 to August 15, 2020, using Lucid Marketplace (Coppock & McClellan, 2019).13 To collect a reasonably representative sample of voting-age adults, we used demographic quotas. To collect quality responses, we asked an attention-check question and filtered out those who responded inaccurately.14 A total of 2,814 respondents passed this question and completed the survey.

Prior to the experiment, we recorded respondents’ perceptions about the severity of COVID-19, general views on Russia, and basic demographics, including partisanship and ideology. We asked about COVID-19 and Russia early on to reduce the possibility that these questions affected how respondents read the experimental treatments and answered outcome questions.

To possibly increase the precision of our treatment effect estimates, we used answers about COVID-19, Russia, education, and partisanship to create a block randomization scheme (Horiuchi et al., 2007; Gerber & Green, 2012) with 16 () pre-stratified groups (see Section C of the Supplementary Materials for details). We selected these pre-treatment variables since they are potentially predictive of the outcome measures we collect. We then randomly divided respondents into three groups (explained below) within each stratum. In addition to potentially increasing efficiency, this approach improves accuracy in interpreting treatment effect heterogeneity conditional on these moderators because treatment assignment is balanced for each moderator by design.

Treatment Variables

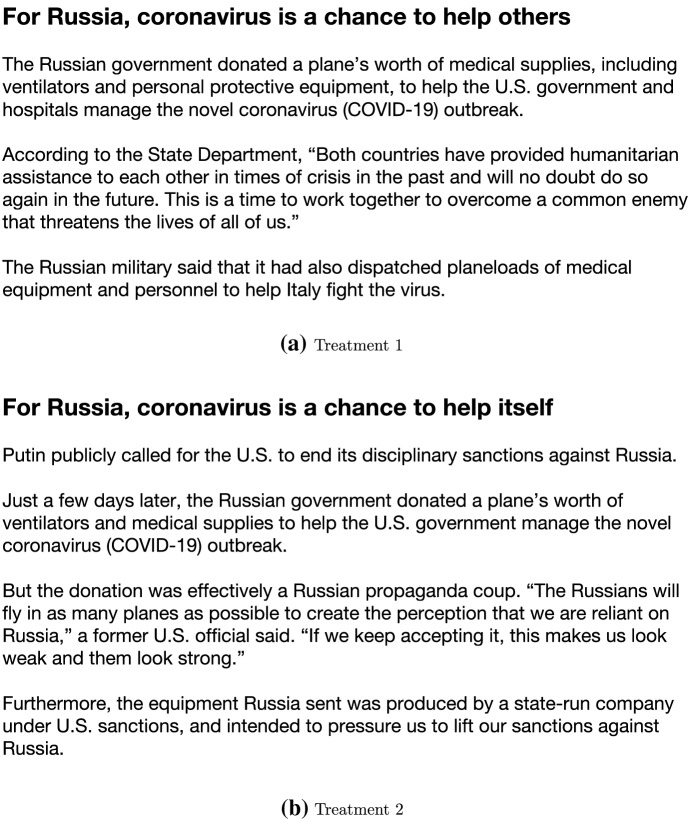

Respondents were randomly assigned with equal probability to Control, Treatment 1, or Treatment 2. Those in the latter two conditions were shown one of two hypothetical articles (see Fig. 1). Respondents in our control condition were not shown any text before answering outcome questions.

Fig. 1.

Screenshots of treatment materials

The first news excerpt (Treatment 1) reports a Russian donation of medical supplies to the U.S. It quotes a State Department official who emphasized a history of mutual assistance, saying “this is a time to work together to overcome a common enemy that threatens the lives of all of us.” At the end, we added a sentence (from a real article) about Russia’s donation to another country to minimize respondent skepticism. In short, Treatment 1 frames Russia’s donation as altruistic.

The second news excerpt (Treatment 2) begins with a sentence highlighting what Russia wants: “Putin publicly called for the U.S. to end its disciplinary sanctions against Russia.” It then reports the donation of ventilators and medical supplies—items the U.S. needs—to emphasize Russia’s possible strategic calculus. It includes a different quote from a former U.S. official who speculated that Russia was trying to “create the perception that we are reliant on Russia,” and make “us look weak and them look strong.”15 It also posits that the donation may be intended to pressure the U.S. to lift sanctions against Russia. In short, Treatment 2 frames Russia’s donation as insincerely driven by ulterior motives.

We ensured that the adapted excerpts were comparable in length and structure. Treatment 1 has 110 words, and Treatment 2 has 123. We added a title to each excerpt, putting it in bold and larger font to emphasize the main point we wanted respondents to comprehend, as newspapers do. The titles are identical except for a single word: “For Russia, coronavirus is a chance to help [others/itself].” We then asked respondents who read the articles to answer a relatively easy question about their content: “Which of the following best describes the article you just read?” The answer options were: “Russia made a donation to help the U.S.” and “Russia made a donation to pressure the U.S.”16 The two keywords—help and pressure—were highlighted in bold to help respondents recognize the key difference between the options.17

Brutger and Strezhnev (2022) and Guisinger (2017), among others, show that the news media is more likely to cover negative news. In our context, however, there exist articles that do not question Russia’s propaganda motivations, such as those published in Fox News, POLITICO, Reuters, and NBC, while others criticize Russia’s propaganda campaigns, such as articles published in CNN and The New York Times. See Section A of the Supplementary Materials.18

It is important to acknowledge that the two treatment conditions still differ across some dimensions. The treatments are not perfectly “information equivalent” (Dafoe et al., 2018). In other words, they might contain “information leakage” (Sher & McKenzie, 2006), feature a “double stimulus” (Converse & Presser, 1986), or contain a “double-barreled treatment” (Kertzer & Brutger, 2016). This possibility means any effects might not just be because of differences in the framing of Russia’s donation across the two treatment vignettes but because of other textual dissimilarities.19

That said, the titles—perhaps the strongest information stimulus, bold and larger than the regular text as they are—differ only by one word. Both treatments state the same facts. Therefore, we think any differences in our outcome variables can be considered as arising from respondents interpreting the facts differently; namely, whether they consider Russia’s donation sincere or insincere.

Before introducing our outcome variables, we want to explain our decision to use articles based on real events. Although experimental social scientists try to maximize information equivalence, they often also want to maximize ecological validity. To examine the impact of a real-world event, it often makes sense to examine the overall effect of actual news articles. Considering these merits and demerits, we decided to design articles based on real articles.

Outcome Variables

To measure foreign policy attitudes, we asked two outcome questions. To ensure that all respondents possessed sufficient baseline knowledge, each included a short description. The first question concerns sanctions that the U.S. placed on Russia in response to Russia invading Ukraine. Specifically, we asked:

- Outcome 1 (Sanctions):

In 2014, Russia began its military invasion and occupation of independent Ukraine (Crimea and some eastern territories). As a result of Russia violating international law, the United States has imposed sanctions on Russia since then. Do you agree or disagree that the U.S. should increase economic and diplomatic penalties on Russia?

The second question concerns future judgments about Russian election interference:

- Outcome 2 (Interference):

Some say that Russia interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Do you agree or disagree that Russia will attempt to influence the 2020 U.S. presidential election this November?

For both sets of response options, we presented respondents with a standard Likert scale: “Strongly disagree,” “Somewhat disagree,” “Neither agree nor disagree,” “Somewhat agree,” and “Strongly agree.”

Sanctions is our primary outcome because we are more theoretically interested in how our treatments influence policy preferences, as opposed to future judgments. In line with this, our preregistered hypotheses only involve Sanctions. To best test those hypotheses, we fixed the question order such that Sanctions always appeared before Interference. We asked Interference as a secondary outcome for exploratory purposes.

Statistical Analysis

We first examine the main outcome (Sanctions)—the degree of respondent support for increasing sanctions against Russia—in its raw form (i.e., as a categorical variable) and describe notable patterns. Then, to formally test our hypotheses, we estimate an ordinary least square (OLS) regression model:

| 1 |

The dependent variable () is respondent i’s answer to the outcome question, treated as continuous, ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”).20 The model includes dummy variables indicating whether respondent i was assigned to Treatment 1 or Treatment 2. The baseline category (i.e., Treatment 1 Treatment 2) is Control. The model also includes fixed effects () for randomized blocks and an error term (). We use robust standard errors to account for possible heteroskedasticity in our error term.

Our Sincerity Hypothesis suggests that respondents in Treatment 1, compared to those in Control, should be less likely to support increasing economic and diplomatic penalties on Russia. Therefore, we expect . Our Insincerity Hypothesis suggests that respondents in Treatment 2, compared to those in Treatment 1, are more likely to support increasing penalties on Russia. Thus, we expect .

It is important to note that we do not test our Insincerity Hypothesis by examining the coefficient for Treatment 2 (i.e., ) because is not the appropriate coefficient for the theory of insincerity aversion. It measures how much the article highlighting Russia’s hidden motives affects Americans’ support for sanctions against Russia compared to a no-information baseline. If this effect is positive (i.e., ) and statistically significant, we may call it a “backlash” or “backfire” effect because a negative frame increases support for the sanctions compared to the baseline of no information. But we do not have a strong theoretical prior that leads us to expect such an effect.21

Results

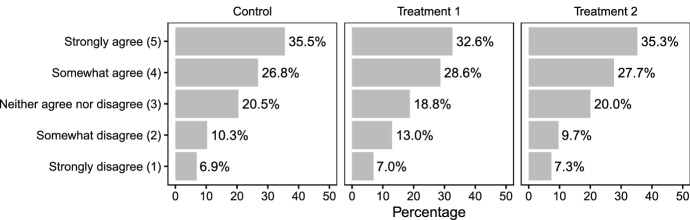

Figure 2 shows the distribution of responses to Sanctions by respondents’ treatment status. The leftmost panel is the distribution among those assigned to the control condition. Overall, Americans are supportive of sanctions against Russia. More than two-thirds (32.2 36.1 percentage) of untreated respondents either strongly or somewhat agree that the U.S. should increase economic or diplomatic penalties on Russia, while less than a tenth ( percentage) either strongly or somewhat disagree.

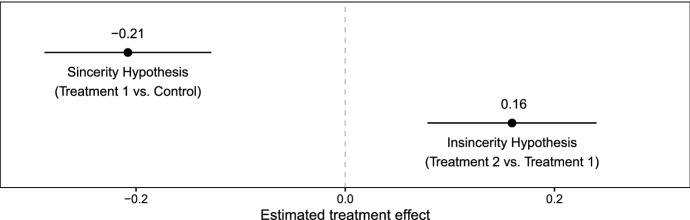

Fig. 2.

The distribution of responses to the question about support for increasing sanctions against Russia, by treatment status. Mean responses were 3.92, 3.72, and 3.87 for each group, respectively. Note: The number of observations is 943, 932, 939 for Control, Treatment 1, and Treatment 2, respectively

But we see a clear shift in the distribution among respondents exposed to information about Russia’s donations to the U.S. that emphasizes Russia’s sincere motives (i.e., Treatment 1, the middle panel). On the one hand, the percentage of those who strongly or somewhat agree with harsher sanctions is lower by 11.5 () percentage points. On the other hand, the percentage of those who neither agree nor disagree with them is higher by a large amount, 9.6 () percentage points. The percentage of those who strongly or somewhat disagree agree with harsher sanctions is also higher by 2.0 () percentage points. These changes suggest that Russia’s donations to the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic—when they are framed as primarily sincere—shifted Americans’ foreign policy attitudes in a favorable direction for the Kremlin. This aligns with our Sincerity Hypothesis.

However, when respondents are exposed to information that Russia’s primary motivation was to make the U.S. look weak and pressure the U.S. to lift sanctions against Russia, the donation’s effect is attenuated. The rightmost panel of Fig. 2 shows the distribution of Sanctions among respondents in Treatment 2. It differs substantially from that of respondents in Treatment 1. The percentage of those who strongly or somewhat agree with sanctions is lower by 4.9 () or 5.8 percentage points (), while the percentage of those who neither agree nor disagree is higher by 10.7 percentage points (). These patterns align with our Insincerity Hypothesis.

We test our hypotheses formally via regression analysis using the model denoted in Eq. (1).22 Figure 3 shows estimated treatment effects when the outcome variable is treated as continuous. The horizontal bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Among respondents in the control group, the average Sanctions score is 3.92, slightly smaller than the value assigned to “Somewhat agree” (4). The difference in Sanctions between Treatment 1 and Control is −0.21, which is significant at the 0.05 level. Thus, we find empirical support for our Sincerity Hypothesis. The effect magnitude is moderate: the effect of Treatment 1 relative to Control is 22 percent of the standard deviation of Sanctions in Control, which is 0.96.

Fig. 3.

The estimated average treatment effects on respondents’ support for increasing sanctions against Russia. Note: The horizontal bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals

The lower part of Fig. 3 shows the results of testing our Insincerity Hypothesis. The average in Treatment 1 is 3.72 and the difference between Treatment 2 and Treatment 1 is 0.16, which is significant at the 0.05 level. Therefore, we also find support for this hypothesis. The effect magnitude is again moderate: the effect of Treatment 2 relative to Treatment 1 is 17 percent of the standard deviation in Treatment 1, which is 0.96.

Our regression analysis shows an additional result: the coefficient for Treatment 2, which is in Eq. (1), is almost zero (see Table D in the Supplementary Materials). This implies that there is no backlash effect from being exposed to Russia’s insincere motives on support for sanctions against Russia.

Overall, we find support for our Sincerity Hypothesis. Donations increase favorable attitudes among the recipient public, and these attitudinal changes translate to shifts in foreign policy positions. We also find support for our Insincerity Hypothesis that “insincerity aversion” is a salient concern in diplomatic relations. When a donation is framed as insincere, recipients are more likely to support hostile foreign policy positions, as compared to when a donation is not framed as insincere.

As a robustness test, we also estimate treatment effects after dropping responses who provided nonsensical comments in an open-reply question and responses flagged by Qualtrics as possible bots.23 The results presented in Section F of the Supplementary Materials (Figs. F.1 and F.2) are almost the same as our main results (Figs. 2 and 3).

Effects on Interference

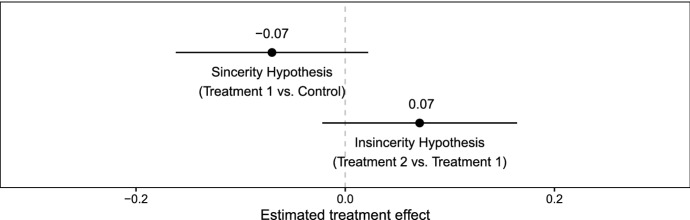

We also report the results of estimating treatment effects on our second outcome variable, Interference, which measures agreement that Russia will intervene in the 2020 U.S. election. Figure 4 shows no clear differences between the three panels. Those who were assigned to Treatment 1 are slightly less likely to agree and more likely to disagree with Russia’s interference, but this difference is marginal.

Fig. 4.

The distribution of responses to the question about the likelihood of Russia interfering in the 2020 U.S. election, by treatment status. Mean responses were 3.74, 3.66, and 3.75 for each group, respectively. Note: The number of observations is 943, 932, 939 for Control, Treatment 1, and Treatment 2, respectively

The estimated treatment effects are presented in Fig. 5. The direction of each is consistent with our expectations, but the magnitudes (− 0.07 for the difference between Treatment 1 and Control or 0.07 for the difference between Treatment 2 and Treatment 1) are small. It is only 6 percent of the standard deviations of Interference in Control or Treatment 1, which are 1.23 or 1.25, respectively. These differences are statistically insignificant at the 0.05 level.

Fig. 5.

The estimated average treatment effects on respondents’ belief that Russia will interfere the 2020 U.S. election. Note: The horizontal bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals

One reason for the null effect might be that the treatments do not mention election interference. With different excerpts, ones that focus on this issue, we might observe different effects. But this would be ecologically invalid: we do not know of any reports linking Russia’s donations and election interference before the period of our study. Another possible explanation for the difference between outcomes is that Sanctions captures support for current, enforceable foreign policy while Interference measures future expectations for Russia’s potential actions.

Conclusion

In this article, we apply the psychological theory of “insincerity aversion” to international relations and show that foreign countries’ image management attempts can be frustrated or facilitated by how the media frames their motives. When a foreign country’s assistance is framed as sincerely motivated, the donor country can induce support for its desired foreign policy among the recipient public. However, when a foreign country’s assistance is framed as insincerely motivated, their positive return is attenuated.24

Our findings imply that countries seeking to attract support for desirable foreign policy outcomes must not only consider their actions but also how those actions are perceived. The target country’s news media has the power to facilitate or attenuate the positive effects of, for instance, humanitarian assistance. Countries conducting public diplomacy should therefore be aware that target countries can use the media to obstruct diplomatic objective-making. They should carefully consider how each of their action options might be represented by actors in targeted countries. For countries that want to guard against foreign countries’ ability to influence or interfere with their citizens’ hearts and minds, our analysis suggests that media frames can weaken or obstruct foreign overtures. Note, though, that using media frames to completely obstruct such attempts may only be possible for states with firm control over the domestic media market.

Through our empirical analysis, we also make theoretical contributions to the literature on foreign public opinion in international relations. First, contrary to the widely discussed theory of cognitive stickiness (Hopf, 2010; Jervis, 1976), our results suggest that countries can change foreign public opinion as long as domestic media frames are consistent with the image that the foreign government wants to project. Foreign assistance, like our case of a Russian donation to the U.S., can favorably shift recipient public’s foreign policy attitudes toward the donor country.

Second, our results are consistent with the theoretical claim that dramatic events provide windows for countries—including major powers like Russia and the United States—who wish to change their images in rival states (Jervis, 1976; Peffley & Hurwitz, 1992). The dramatic event in our case is the pandemic. This finding has important implications for our understanding of “health diplomacy” (Fazal, 2020). Countries’ diplomatic efforts in this area may affect how citizens worldwide view donors (including major powers) and the kinds of foreign relations that they support. Future work should directly test the effects of dramatic events by examining how successful countries are at changing national images across contexts, both “dramatic” and not.25

Third, our analysis of our secondary outcome measure (i.e., the perceived likelihood of Russia’s interference in the U.S. elections) suggests that the effects of image management campaigns may be issue specific. This might suggest “dynamic constraints in belief systems” (Converse, 1964; Coppock & Green, 2021): even when an exogenous factor (in our case, the exposure to a media article) changes public opinion about one issue (e.g., sanctions against Russia), public opinion on other issues (e.g., Russia’s election interference) may not change. We need further inquiry into the mechanisms under which specific public diplomacy (in particular, information) campaigns influence foreign public opinion.

Finally, and most importantly, we shed light on the media’s ability to facilitate or impede states’ public diplomacy. Existing literature on the media’s role in international relations highlights how hard it is to change foreign public opinion, particularly for states with an enemy image. But an increasingly high-choice media environment and the resulting diverse media frames could sway foreign public opinion in different ways (Dubois & Blank, 2018; Guess, 2021). We hope our research invites further work on how divergent media frames affect the success of public diplomacy campaigns and, in turn, international relations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Footnotes

Our definition of a donation is general and includes any overt economic assistance to other countries for non-development and non-military purposes.

See Section A of the Supplementary Materials for news reports about this event.

Also see Mercer’s (1996) “desires hypothesis,” which highlights the difficulty in changing enemy images.

Domestic media reacts to investments, funding, or donations from foreign countries. See Section A of the Supplementary Materials for examples.

We can think of scenarios where the two—public diplomacy and domestic media framing—can be separated. For example, Russia’s public diplomacy could occur without U.S. media framing. Still, Americans may consume international media, such as Russian media coverage of Russian actions. Therefore, influencing the target country’s public opinion—even without that country’s domestic media coverage—is increasingly feasible given that countries have the technology to broadcast their media (e.g., Russia Today) abroad. Although we think delinking these two processes (i.e., public diplomacy and domestic media framing) theoretically and empirically is important for future research, this paper focuses on what happens when states engage in public diplomacy and the targeted country’s media frame these campaigns.

Baum and Potter (2008) argue that elites provide supply: reporters rely on elites as official sources.

Entman’s (2003) theory echoes the concept of homophily: people and states tend to have positive ties with those similar to them (Cottam, 1994; Herrmann, 1985).

Similarly, Bush and Prather (2020) show that support for economic relations with another country is shaped by whether people perceive that country as having taken their party’s side. Flynn et al. (2022) examine how American attitudes toward China are influenced by misinformation about Chinese foreign policy.

Alrababa’h et al. (2020) show how framing impacts views on aid from the European Union but not from Russia, while we find significant effects from Russia’s aid. We will discuss explanations for this difference later.

Opinion formation research confirms elite commentary’s salience (Zaller, 1992).

We do not separate the effects of media frames from elite commentary. We added elite quotes to both of our treatments, which we explain next, to maximize ecological validity. Media reports about public diplomacy typically contain such quotes from elites. Future work could identify the effects of media framing and elite cues separately by varying the presence and substantive content of elite comments.

See Eri Sugiura, “Blinken denounces China’s ‘strings attached’ vaccine diplomacy,” Nikkei Asia, March 17, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Editor-s-Picks/Interview/Blinken-denounces-China-s-strings-attached-vaccine-diplomacy (last accessed on August 16, 2022).

See Section B of the Supplementary Materials for additional information about our survey design. We pre-registered our study on August 11, 2020 at Evidence in Government and Politics (EGAP), after collecting a small number of observations in soft launch (https://osf.io/pt8ry/). The pre-analysis plan is also available in Section G of the Supplementary Materials. The study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College (IDs: STUDY00032069, MOD00010279). A complete replication package is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZXSGPP.

We took this precaution to alleviate concerns about the quality of survey samples collected during the COVID-19 pandemic (Aronow et al., 2020).

One potentially salient difference between the treatments is that the first quotes a current official, while the second quotes a former official. Future research could test different sources and their credibility.

Answer option order was randomized to eliminate order effects.

Since the objective is only to remind respondents of the main point, we do not subset based on these answers. We also note that our estimated treatment effects are, strictly speaking, the effects of asking respondents to read and then more carefully consider information about Russia (using the question above).

Still, the insincerity frame may be more likely than the sincerity frame to have been circulated in the United States and, therefore, the probability of individuals being assigned to our treatments in the real world may be imbalanced. Future work could use treatments with ecologically-valid weights.

For example, any treatment effects might be consequences of providing positive vs. negative information about Russia and not necessarily be linked to Russia’s motivations. Future work could expose respondents to a range of negative information about a country, including some about sincerity. Variation in types of negative information would contextualize the effects of insincerity versus those of other revealed information. We thank an anonymous reviewer for highlighting this potentially fruitful future direction.

We also run an ordered probit regression model and present results in Section D of the Supplementary Materials.

If we had a strong prior about the backlash effect or if our objective were to test such an effect, we could test whether the Treatment 2 coefficient is positive; namely, . However, this expectation would still be consistent with our expectation of under the Sincerity Hypothesis of . (Note that we believe that is highly unlikely. That would mean that respondents are less likely to support increasing penalties on Russia when they are informed of Russia’s insincere motives.) Put differently, our hypothesis of does not preclude the possibility of a backlash effect. In contrast, stating our Insincerity Hypothesis as would make a strong assumption about the backlash effect.

Section D of the Supplementary Materials includes a table showing OLS regression results. It also includes ordered probit regression results, which are substantively similar. In Section E of the Supplementary Materials, for our exploratory analyses, we make subgroups of respondents based on each of the four binary pre-treatment covariates used for block randomization and examine heterogeneity in treatment effects. We find that prior attitudes towards the donor, partisanship, and perceived urgency do not make someone more or less likely to change their opinions, but that education does seem to matter.

This additional robustness test is not part of our pre-registration. Since we delete these observations after treatment assignment (Montgomery et al., 2018), we must interpret results with reservation.

As we discuss earlier in the paper, we think future work should disentangle and identify the independent and conditional effects of both public diplomacy efforts and media coverage of these efforts on domestic public opinion. The continued expansion of domestic outlets (e.g., Breitbart) and foreign outlets’ increased ability to reach audiences abroad (e.g., Russia Today) raise the question of how domestic publics evaluate multiple, competing narratives about foreign countries. Future research should provide competing frames about public diplomacy actions, varying not only frame content but also whether the sources are foreign or domestic.

Mattingly and Sundquist (2022), in a natural experiment, show that messages emphasizing Chinese generosity have modest positive effects on Indian perceptions of China even during one kind of dramatic event (a battle between the two countries and higher geopolitical tensions). Related questions for future research are how long opinion changes induced by public diplomacy last, and whether they occur during periods of crisis or not.

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Graduate Immersion Conference 2020 in the Department of Political Science at the Ohio State University (October 26–27, 2020), the Asian Politics Online Seminar Series (December 2, 2020), the 2021 Winter Meeting of the Japanese Society for Quantitative Political Science (January 11, 2021), and the American Political Science Association Annual Meeting (September 30–October 3, 2021). The first draft was written by Rhee as an independent research paper that was supervised by Crabtree and Horiuchi when she was an undergraduate student at Dartmouth College. Rhee thanks the Ethics Institute at Dartmouth College for providing financial support for the project. We also thank Matt Baum, Tim Gravelle, Richard Herrmann, Takeshi Iida, Jiyoung Ko, Kelly Matush, Eric Min, Elizabeth Saunders, Robert Trager, and other conference and seminar participants for their helpful comments.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kasey Rhee, Email: kjrhee@stanford.edu.

Charles Crabtree, Email: crabtree@dartmouth.edu, http://charlescrabtree.com/.

Yusaku Horiuchi, Email: yusaku.horiuchi@dartmouth.edu, https://horiuchi.org/.

References

- Abelson R. Script processing in attitude formation and decision making. In: Carroll J, Payne J, editors. Cognition and social behavior. Erlbaum; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Alrababa’h A, Myrick R, Webb I. Do donor motives matter? Investigating perceptions of foreign aid in the conflict in Donbas. International Studies Quarterly. 2020;64(3):748–757. doi: 10.1093/isq/sqaa026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrabi T, Das J. In aid we trust: Hearts and minds and the Pakistan earthquake of 2005. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2017;99(3):371–386. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aronow, P. M., Kalla, J., Orr, L., & Ternovski, J. (2020). Evidence of Rising Rates of Inattentiveness on Lucid in 2020.

- Baum MA, Potter PBK. The relationships between mass media, public opinion, and foreign policy: Toward a theoretical synthesis. Annual Review of Political Science. 2008;11(1):39–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060406.214132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RA, Blair RM, Roessler P. Foreign aid and soft power: Great power competition in Africa in the early twenty-first century. British Journal of Political Science. 2022;52(3):1355–1376. doi: 10.1017/S0007123421000193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boulding KE. The image: Knowledge in life and society. University of Michigan Press; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Brutger R, Strezhnev A. International investment disputes, media coverage, and backlash against international law. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2022;66(6):983–1009. doi: 10.1177/00220027221081925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno de Mesquita B. The war trap. Yale University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bush SS, Prather L. Foreign meddling and mass attitudes toward international economic engagement. International Organization. 2020;74(3):584–609. doi: 10.1017/S0020818320000156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E. The big stick: The limits of soft power and the necessity of military force. Basic Books; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Converse JM, Presser S. Survey questions: Handcrafting the standardized questionnaire. Sage; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Converse PE. The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In: Apter D, editor. Ideology and discontent. The Free Press; 1964. pp. 206–261. [Google Scholar]

- Coppock A, Green DP. Do belief systems exhibit dynamic constraint? Journal of Politics. 2021;84(2):725–738. doi: 10.1086/716294. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coppock Alexander, McClellan Oliver A. Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research & Politics. 2019 doi: 10.1177/2053168018822174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cottam M. Images & intervention: US policies in Latin America. University of Pittsburgh Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cottam R. Foreign policy motivation: A general theory and a case study. University of Pittsburgh Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Dafoe A, Zhang B, Caughey D. Information equivalence in survey experiments. Political Analysis. 2018;26(4):399–416. doi: 10.1017/pan.2018.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darnton C. Public diplomacy and international conflict resolution: A cautionary case from cold war South America. Foreign Policy Analysis. 2020;16(1):1–20. doi: 10.1093/fpa/orz003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois E, Blank G. The echo chamber is overstated: The moderating effect of political interest and diverse media. Information, Communication & Society. 2018;21(5):729–745. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1428656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein DM, Krebs RR. Washington’s troubling obsession with public diplomacy. Survival. 2005;47(1):89–104. doi: 10.1080/00396330500061760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Entman Robert M. Projections of power: Framing news, public opinion, and US Foreign Policy. University of Chicago Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fazal TM. Health diplomacy in pandemical times. International Organization. 2020;74(S1):E78–E97. doi: 10.1017/S0020818320000326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fein S, Hilton JL. Judging others in the shadow of suspicion. Motivation and Emotion. 1994;18(2):167–198. doi: 10.1007/BF02249398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fein S, Hilton JL, Miller DT. Suspicion of ulterior motivation and the correspondence bias. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58(5):753–764. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay D, Holsti O, Fagen R. Enemies in politics. Rand McNally; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn DJ, Horiuchi Y, Zhang D. Misinformation, economic threat and public support for international trade. Review of International Political Economy. 2022;29(2):571–597. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2020.1824931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber AS, Green DP. Field experiments: Design, analysis, and interpretation. W.W. Norton; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith BE, Horiuchi Y. In search of soft power: Does foreign public opinion matter for US Foreign Policy? World Politics. 2012;64(3):555–585. doi: 10.1017/S0043887112000123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith BE, Horiuchi Y, Matush K. Does public diplomacy sway foreign public opinion? Identifying the effect of high-level visits. American Political Science Review. 2021;115(4):1342–1357. doi: 10.1017/S0003055421000393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith BE, Horiuchi Y, Wood T. Doing well by doing good: The impact of foreign aid on Foreign Public Opinion. Quarterly Journal of Political Science. 2014;9(1):87–114. doi: 10.1561/100.00013036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guess AM. (Almost) everything in moderation: New evidence on Americans’ online media diets. American Journal of Political Science. 2021;65(4):1007–1022. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guisinger A. American opinion on trade: Preferences without politics. Oxford University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann R. Perceptions and behavior in Soviet Foreign Policy. University of Pittsburgh Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann R. Image theory and strategic interaction in international relations. In: Sears DO, Huddy L, Jervis R, editors. Oxford handbook of political psychology. Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 285–314. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann R, Fischerkeller MP. Beyond the enemy image and spiral model: Cognitive-strategic research after the cold war. International Organization. 1995;49:415–450. doi: 10.1017/S0020818300033336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann R, Voss J, Schooler T, Ciarrochi J. Images in international relations: An experimental test of cognitive schemata. International Studies Quarterly. 1997;41:403–433. doi: 10.1111/0020-8833.00050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbing JR, Alford JR. Accepting authoritative decisions: Humans as wary cooperators. American Journal of Political Science. 2004;48(1):62–76. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00056.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman D. Beyond public diplomacy. Foreign Affairs. 2002;81(2):83–95. doi: 10.2307/20033086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holsti OR. Cognitive dynamics and images of the enemy. Journal of International Affairs. 1967;21(1):16–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hopf T. The logic of habit in international relations. European Journal of International Relations. 2010;16(4):539–561. doi: 10.1177/1354066110363502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi Y, Imai K, Taniguchi N. Designing and analyzing randomized experiments: Application to a Japanese election survey experiment. American Journal of Political Science. 2007;51(3):669–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00274.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Cha J. Russia and Putin receive low ratings globally. Pew Research Center; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jervis R. The logic of images in international relations. Princeton University Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Jervis R. Perception and misperception in international politics. Princeton University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kertzer JD, Brutger R. Decomposing audience costs: Bringing the audience back into audience cost theory. American Journal of Political Science. 2016;60(1):234–249. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kissinger H. The necessity for choice: Prospects of American foreign policy. Harper; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Kunstman JW, Tuscherer T, Trawalter S, Paige Lloyd E. What lies beneath? Minority Group Members’ Suspicion of Whites’ Egalitarian motivation predicts responses to whites smiles. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2016;42(9):1193–1205. doi: 10.1177/0146167216652860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Kunstman JW, Malta BD, Sawyer PJ, Townsend SSM, Mendes WB. Suspicion of motives predicts minorities’ responses to positive feedback in interracial interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2016;62:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly DC, Sundquist J. When does public diplomacy work? Evidence from China’s “Wolf Warrior” diplomats. Political Science Research and Methods. 2022 doi: 10.1017/psrm.2022.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo R. Cognition is a matter of trust: Distrust tunes cognitive processes. European Review of Social Psychology. 2015;26(1):283–327. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2015.1117249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw KM. Political impressions: Formation and management. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw KM, Lodge M, Jones JM. The pandering politicians of suspicious minds. Journal of Politics. 2002;64(2):362–383. doi: 10.1111/1468-2508.00130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer J. Reputation and international politics. Cornell University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery J, Nyhan B, Torres M. How conditioning on posttreatment variables can ruin your experiment and what to do about it. American Journal of Political Science. 2018;62(3):760–775. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthau H. Politics among nations: The struggle for power and peace. Knopf; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Nye JS. Public diplomacy and soft power. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;616(1):94–109. doi: 10.1177/0002716207311699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Shao Z, Yiqing X. How government-controlled media shifts policy attitudes through framing. Political Science Research and Methods. 2021;10(2):317–332. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2021.35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peffley M, Hurwitz J. International events and foreign policy beliefs: Public response to changing Soviet-U.S. relations. American Journal of Political Science. 1992;36(2):431–61. doi: 10.2307/2111485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robison J. Can elites escape blame by explaining themselves? Suspicion and the limits of elite explanations. British Journal of Political Science. 2021;52(2):553–572. doi: 10.1017/S000712342000071X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheafer T, Shenhav SR, Takens J, van Atteveldt W. Relative political and value proximity in mediated public diplomacy: The effect of state-level homophily on international frame building. Political Communication. 2014;31(1):149–167. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2013.799107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sher S, McKenzie CRM. Information leakage from logically equivalent frames. Cognition. 2006;101(3):467–494. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimko K. Images and arms control: Perceptions of the Soviet Union in the reagan administration. University of Michigan Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons BA. International studies in the global information age. International Studies Quarterly. 2011;55(3):589–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00676.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A. Why Nations cooperate: Circumstance and choice in international relations. Cornell University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Terror Free for Tomorrow. (2006). Humanitarian Assistance Key to Favorable Public Opinion in World’s Three Most Populous Muslim Countries. Terror Free Tomorrow.

- Tetlock P. Theory-driven reasoning about plausible pasts and probable futures in world politics: Are we prisoners of our preconceptions? American Journal of Political Science. 1999;43(2):335–366. doi: 10.2307/2991798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Economist. (2005). More generous than Thou: Emergency aid is proving just as politically charged as any other kind. The Economist.

- Waltz K. Theory of international politics. Addison-Wesley; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- White R. Images in the context of international conflict: Soviet Perceptions of the US and the USSR. In: Kelman HC, editor. International behavior: A social–psychological analysis. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston; 1965. pp. 236–276. [Google Scholar]

- Wike R. Does Humanitarian aid improve America’s image? Pew Research Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zaller J. The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.