Abstract

Background

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) primarily complicates the course of asthma, cystic fibrosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Mortality data of ABPA and the difference in all-cause mortality between ABPA with and without COPD are not available.

Objective

We investigated the difference in all-cause mortality between ABPA with and without COPD.

Methods

A retrospective review was performed among patients with the diagnosis of ABPA at Peking University People’s Hospital between January 2010 and March 2022. Logrank test was performed to investigate the difference between all-cause mortality for ABPA with and without COPD and Cox regression analysis was performed to investigate the independent risk factors for all-cause mortality in patients with ABPA.

Results

Sixty-one patients with ABPA were enrolled in this study. The follow-up duration was 50.38 months (3–143 months). In the COPD group, 7 patients died (7/10), while in the non-COPD group, 4 patients died (4/51). The 1-year survival rates of ABPA with and without COPD were 60% and 97.8%, respectively. The 5-year survival rates of ABPA with and without COPD were 40% and 94%, respectively. The Cox regression analysis showed that higher C-reactive protein (CRP) (HR = 1.017, 95% CI 1.004–1.031, P = 0.013) and complicating COPD (HR = 8.525, 95% CI 1.827–39.773, P = 0.006) were independent risk factors associated with mortality in patients with ABPA.

Conclusion

The all-cause mortality for ABPA with COPD is higher than that for ABPA without COPD. Higher CRP and complicating COPD are independent risk factor for mortality in patients with ABPA.

Keywords: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, pulmonary disease, mortality, risk factor, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Introduction

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is an allergic pulmonary disease caused by a hypersensitivity reaction to Aspergillus species.1,2 A meta-analysis has shown that the prevalence of ABPA in adults with asthma worldwide ranges from 0.72% to 3.5%,3 and 2.5% of non-smoking adult asthma patients in China meet the diagnostic criteria for ABPA,4 which reveals that ABPA is not a rare disease in asthma patients. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),5–7 bronchiectasis,8 and cystic fibrosis9 can also be complicated by ABPA. Agarwal et al initially described the occurrence of ABPA in COPD in 2008.10 Its prevalence ranges from 2% to 15%, with a pooled prevalence of about 9.5%,11 suggesting that ABPA is not a rare comorbidity of COPD. It is well known that COPD has high morbidity and mortality worldwide.12 The presence of Aspergillus sensitization in COPD is associated with frequent exacerbations,13 bronchiectasis,7 and poor lung function.5,14 Considering the fact that the combination with COPD can significantly increase the mortality of patients with asthma,15 COPD may also have a similar impact on patients with ABPA. Most studies performed in patients with ABPA were case reports or cross-sectional studies with the follow-up duration ranging from 3 months to 43.7 months,16–20 and few studies focused on the long-term follow-up and prognosis, especially for ABPA with COPD. Additionally, the mortality of ABPA and the difference between all-cause mortality for ABPA with and without COPD have never been reported.16–23 Hence, this study aimed to retrospectively analyze the follow-up data of patients with ABPA to explore the difference between all-cause mortality for ABPA with and without COPD and to promote early identification and intervention of severe and high-risk patients.

Methods

Study Design and Ethics Approval

This study was a retrospective clinical data analysis, and the research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University People’s Hospital. The requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, but all data were anonymized and data confidentiality was maintained.

Study Subjects

The medical records of patients diagnosed with ABPA in the outpatient or inpatient department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine from January 2010 to March 2022 in the information system of Peking University People’s Hospital were reviewed using “allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis” as the search term.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients with ABPA who met the diagnostic criteria of the “Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis” (2017 edition) were included in the study,24 and patients with insufficient diagnostic evidence and less than 3 months of follow-up were excluded from the study. The diagnosis of COPD complied with the diagnostic criteria of the Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of COPD (2013 Revised Edition).25 The diagnosis of asthma complied with the diagnostic criteria of the Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Bronchial Asthma (2016 Edition).26 The diagnosis of bronchiectasis complied with the diagnostic criteria of the Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Adult Bronchiectasis (2012 Edition).27 Central bronchiectasis (CB) was defined using two different criteria, depending on whether bronchiectasis was confined to the medial half (point midway between the hilum and chest wall) or the medial two-thirds of the lung.28

Data Collection

Data, including general information, clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), pulmonary function (Jaeger, Germany), diagnosis course, follow-up time, treatment medicine, and survival status, were collected from the medical records of patients. Serum total immunoglobulin E (IgE) was assessed using Roche Cobas e601 electrochemiluminescence instrument; Aspergillus fumigatus m3 allergen among Thermo Fisher Scientific detection reagents was used to assess Aspergillus fumigatus specific IgE (Sp-IgE). Results of laboratory tests, chest HRCT, and pulmonary function were obtained when the patients were diagnosed with ABPA for the first time in our hospital or in another hospital. An arterial blood gas test was performed in patients without oxygen uptake before treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed, and graphs were drawn with SPSS (version 26.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range (lQR; 25th to 75th percentile). Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square test, while Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to compare the survival distribution among different groups and Kaplan–Meier survival curves for different groups of subjects were obtained and plotted. To identify variables independently associated with mortality, we conducted the Cox regression analysis by including the variables with P ≤ 0.05 in the univariate analysis. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline Data of Patients with ABPA

Seventy-five inpatients and outpatients were retrieved, and 13 patients with an inadequate diagnosis and 1 patient with a follow-up period of less than 3 months were excluded. Among the 61 patients, 58 patients fully met the diagnostic criteria, and total IgE of three patients was not more than 1000 IU/mL (764.8–978.2 IU/mL). All of them were taking glucocorticoids while testing of total IgE, their clinical characteristics and imaging features met the diagnostic criteria of ABPA, and glucocorticoids and antifungal drugs were effective. Finally, 61 patients were included, including 29 males. All patients had stage I disease on admission. The follow-up time ranged from 3 to 143 months, with an average follow-up time of 50.38 months.Ten patients with COPD were identified; all of them had a long-term history of heavy smoking (32.5 [27.5–55.13] pack-years) and definite emphysema, and 4 of them were complicated with asthma. There were 11 deaths during 252 person-years of follow-up. Among the 11 patients who died, 7 died of respiratory disease, 2 died of colon cancer, 1 died of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, and 1 died due to an unknown cause. Seven of the 10 patients with COPD died (70%). Among the 50 patients without COPD, 4 patients died (7.84%). The mean survival time of ABPA with and without COPD was 37 months and 129.98 months, respectively. The mean age at the time of death for ABPA with and without COPD was 76 years and 74 years, respectively.

Comparison of Characteristics Between Patients Who Had ABPA with or Without COPD

Age (76.00 ± 9.64 years vs 52.78 ± 16.77 years, P < 0.001), proportion of male patients (10 [100%] vs 21 [41.18%], P = 0.002), smoking history (10 [100%]) vs 11 [21.57%], P < 0.001), pack-years of smoking (0 [0–0] vs 32.5 [27.5–55.13], P < 0.001), death rate (7 [70%] vs 4 [7.84%], P < 0.001), neutrophil count (7.45 ± 2.64 × 109/L vs 5.12 ± 3.05 × 109/L, P = 0.029), neutrophil percentage (69.04 ± 25.5% vs 55.08 ± 15.73%, P = 0.041), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (8.68 [4.33–16.66] vs 1.90 [1.43–5.86], P < 0.001), and C-reactive protein (CRP) (15.10 mg/L [7.91–100.84 mg/L] vs 3.94 mg/L [1.00–15.40 mg/L], P = 0.011) at diagnosis were significantly higher in patients with COPD than in patients without COPD. Body mass index (BMI) (20.61±2.59 kg/m2 vs 23.07± 3.48 kg/m2, P = 0.040), eosinophil count (0.09× 109/L [0.03–0.65 × 109/L] vs 0.62 × 109/L [0.24–0.94 × 109/L], P=0.026), eosinophil percentage (1.45% [0.23–6.85%] vs 9.6 [2.61–13.5%], P = 0.006), proportion of patients with asthma (4 [40.00%] vs 48 [94.12%], P < 0.001) and with allergic rhinitis (1 [10.00%] vs 32 [60.78%], P = 0.009), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) (46.94 ± 7.79% vs 63.08 ± 15.9%), P < 0.001), percentage of FEV1 predicted (FEV1%) (37.17 ± 8.59% vs 64.82 ± 26.25%), P < 0.001), peak expiratory flow percentage (PEF) (2.80 L/s [2.57–3.58 L/s] vs 4.70 L/s [3.21–6.55 L/s], P = 0.012), percentage of PEF predicted (PEF%) (40.30% [32.50–47.15%] vs 73.80 [49.50–95.30%], P = 0.001), percentage of the diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide predicted (DLCO%) (56.56 ± 14.66% vs 75.68 ± 22.74%, P = 0.021), and diffusing capacity divided by the alveolar volume (DLCO/VA) (0.85 mmol/min/kPa/L [0.64–1.04 mmol/min/kPa/L] vs 1.47 mmol/min/kPa/L [1.24–1.60 mmol/min/kPa/L], P < 0.001) were significantly lower in patients with COPD than in patients without COPD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Characteristics Between Patients Who Had ABPA with or Without COPD

| All Patients (n=61) | With COPD | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=10) | No (n=51) | |||

| Age, years | 58.63±17.01 | 76.00±9.64 | 52.78±16.77 | <0.001 |

| Male | 31 (50.82%) | 10(100.00%) | 21(41.18%) | 0.002 |

| Smokers | 21(34.43%) | 10(100.00%) | 11(21.57%) | <0.001 |

| Pack-years of smoking | 0 (0–12.5) | 0 (0–0) | 32.5 (27.5–55.13) | <0.001 |

| Dead | 11(18.03%) | 7(70.00%) | 4(7.84%) | <0.001 |

| Duration of ABPA, in months | 249.00(85.00–592.00) | 321(76.50–603.50) | 165.00(85.00–592.00) | 0.585 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.61±3.53 | 20.61±2.59 | 23.07±3.48 | 0.040 |

| Peripheral blood cells | ||||

| Leukocyte, ×109/L | 9.12±3.83 | 9.40±2.54 | 8.89±4.00 | 0.703 |

| Neutrophil, ×109/L | 5.63±3.10 | 7.45±2.64 | 5.12±3.05 | 0.029 |

| Neutrophil, % | 58.00±18.27 | 69.04±24.5 | 55.08±15.73 | 0.026 |

| Eosinophil, ×109/L | 0.49(0.07–0.90) | 0.09(0.03–0.65) | 0.62(0.24–0.94) | 0.026 |

| Eosinophil, % | 6.90(0.9–13.00) | 1.45(0.23–6.85) | 9.60(2.61–13.50) | 0.006 |

| Inflammatory indicator | ||||

| NLR | 2.65(1.49–6.65) | 8.68(4.33–16.66) | 1.90(1.43–5.86) | <0.001 |

| CRP, mg/L | 5.97(1.90–18.50) | 15.1(7.91–100.84) | 3.94(1.00–15.40) | 0.011 |

| ESR, mm/h | 17.00(7.0–29.00) | 20.5(7.50–43.25) | 17(6.00–28.00) | 0.477 |

| Immunological tests | ||||

| Total IgE, IU/mL | 2248.00(1256.00–2500.00) | 2213.50(1260.50–2500.00) | 2248.00(1256.00–2500.00) | 0.968 |

| Sp-IgE, kUA/L | 2.82(0.68–12.80) | 2.56(1.10–6.83) | 2.82(0.53–13.30) | 0.579 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Asthma | 52(85.25%) | 4(40.00%) | 48(94.12%) | <0.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 32(52.46%) | 1(10.00%) | 31(60.78%) | 0.009 |

| Spirometry | ||||

| FEV1/FVC | 59.45±15.80 | 46.94±7.79 | 63.08±15.90 | <0.001 |

| FEV1/pred | 57.79±27.06 | 37.17±8.59 | 64.82±26.25 | <0.001 |

| PEF, L/s | 3.79(2.89–5.93) | 2.80(2.57–3.58) | 4.70(3.21–6.55) | 0.012 |

| PEF, % | 57.50(41.00–87.00) | 40.3(32.50–47.15) | 73.8(49.5–95.30) | 0.001 |

| DLCO, % | 71.94±22.68 | 56.56±14.66 | 75.68±22.74 | 0.021 |

| DLCO/VA, mmol/min/kPa/L | 1.29(1.05–1.55) | 0.85(0.64–1.04) | 1.47(1.24–1.60) | <0.001 |

| Arterial blood gas | ||||

| PaO2, mmHg | 76.05±12.35 | 73.00±11.89 | 76.33±12.71 | 0.461 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 41.00(39.00–44.00) | 40.00(40.00–4.75) | 41.00(38.00–43.00) | 0.566 |

| SaO2, % | 96.00 (94.00–97.00) | 95.00(91.50–96.75) | 96.00(94.00–97.00) | 0.182 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Glucocorticoids | 54(88.52%) | 8(80.00%) | 46(90.20%) | 0.702 |

| Antifungal Drugs | 43(70.49%) | 6(60.00%) | 35(68.63%) | 0.870 |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; DLCO, Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide; VA, Alveolar volume; ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FEV1/FVC, Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC); FEV1/pred, Percentage of FEV1 predicted; IgE, Immunoglobulin E; NLR, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PEF, Peak expiratory flow percentage; PaO2, Partial arterial oxygen pressure; PaCO2, Partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide; SaO2, Oxygen saturation; Sp-IgE, Aspergillus fumigatus specific IgE.

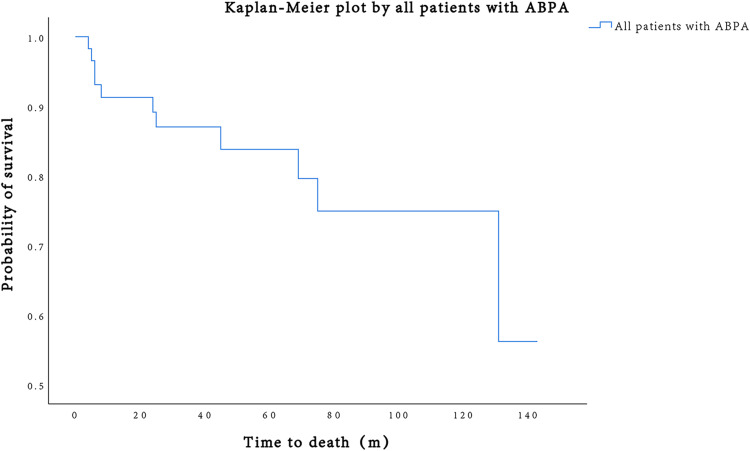

Survival Time and Rate in Patients with ABPA

Kaplan-Meier curves showed the overall survival curve of all patients with ABPA. The average survival time was 114 months. The 1-year and 5-year survival rate was 91.3% and 83.8%, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Survival curves for all-cause mortality in all patients with ABPA.

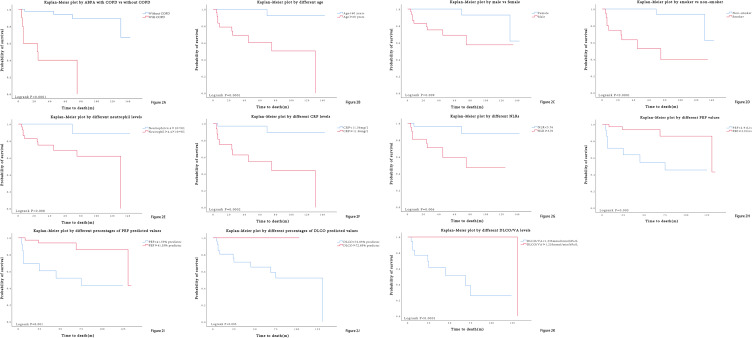

Results of the Kaplan-Meier Analysis for Mortality of ABPA

Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that COPD affected the survival time of patients with ABPA, and the all-cause mortality for ABPA with COPD was much higher than that for ABPA without COPD (Figure 1). According to the results of Kaplan-Meier analysis, male gender, smoking history, older age, higher CRP and NLR, lower PEF, PEF%, DLCO%, and DLCO/VA had a significantly higher risk for all-cause mortality (the cutoff value of continuous variables was calculated by the ROC curve) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2.

Results of the Kaplan-Meier Analysis for Motality of ABPA

| Variable | Log Rank Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Survival Time (Months) | χ2 | P value | ||

| COPD | Yes | 37.00 | 34.94 | <0.001 |

| No | 129.98 | |||

| Age | ≥ 60 years | 80.84 | 14.75 | <0.001 |

| < 60 years | 137.31 | |||

| Gender | Male | 91.85 | 6.73 | 0.009 |

| Female | 134.00 | |||

| Smokers | Yes | 72.21 | 15.77 | <0.001 |

| No | 134.63 | |||

| Neutrophil | ≥4.4 × 109/L | 92.00 | 7.06 | 0.008 |

| <4.4 × 109/L | 134.78 | |||

| CRP | ≥11.56mg/L | 73.53 | 13.83 | <0.001 |

| <11.56mg/L | 133.33 | |||

| NLR | ≥3.76 | 76.64 | 7.44 | 0.006 |

| <3.76 | 131.52 | |||

| PEF | ≥2.91L/s | 120.65 | 9.03 | 0.003 |

| <2.91L/s | 71.06 | |||

| PEF% | ≥41.55% | 120.87 | 10.16 | 0.001 |

| <41.55% | 68.25 | |||

| DLCO% | ≥72.85% | - | 7.97 | 0.005 |

| <72.85% | 82.96 | |||

| DLCO/VA | ≥1.235mmol/min/kPa/L | 131.00 | 18.35 | <0.001 |

| <1.235mmol/min/kPa/L | 60.04 | |||

Abbreviations: COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; DLCO, Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide; VA, Alveolar volume; NLR, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PEF, Peak expiratory flow percentage.

Figure 2 .

Survival curves for all-cause mortality in patients of different subgroups.

Comparison of the Clinical Characteristics of All Patients with ABPA Between the Death and Survival Groups

Age (73.00 ± 10.02 years vs 52.98 ± 17.37 years, P = 0.001), proportion of male patients (9 [81.82%] vs 22 [44.00%], P = 0.023), smoking history (9 [81.82%] vs 12 [24.00%], P = 0.001), pack-years of smoking (0 [0–0] vs 30 [15–50], P < 0.001), neutrophil count (7.33 ± 2.85 × 109/L vs 5.09 ± 3.01× 109/L, P = 0.030), NLR (6.50 [2.96–14.28] vs 1.97 [1.41–5.88], P = 0.002), CRP (48.16 mg/L [9.72–126.70 mg/L] vs 3.03 mg/L [0.98–10.96 mg/L], P < 0.001), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (28.00 mm/h [15.00–67.50 mm/h] vs 13.50 [5.00–26.50 mm/h], P = 0.030), and proportion of patients with COPD (7 [63.64%] vs 3 [6.00%], P < 0.001) were significantly higher in the death group than in the survival group. Proportion of patients with allergic rhinitis (2 [18.18%] vs 30 [60.00%], P = 0.012), PEF (2.71 L/s [2.35–3.67 L/s] vs 4.68 L/s [3.31–6.53 L/s], P = 0.027), PEF% (39.6% [30.55–56.90%] vs 73.50 [48.83–94.48%], P = 0.024), DLCO% (57.57 ± 10.62% vs 76.41 ± 23.51%, P = 0.014), and DLCO/VA (1.04 mmol/min/kPa/L [0.78–1.15 mmol/min/kPa/L] vs 1.48 mmol/min/kPa/L [1.24–1.61 mmol/min/kPa/L], P < 0.001) were significantly lower in patients in the death group than in patients in the survival group (Table 3). The detailed condition of the died patients was provided (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics of All Patients with ABPA Between the Death and Survival Groups

| Survival | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=50) | No (n=11) | ||

| Age, years | 52.98±17.37 | 73.00±10.02 | 0.001 |

| Male | 22(44.00%) | 9(81.82%) | 0.023 |

| Smokers | 12(24.00%) | 9(81.82%) | 0.001 |

| Pack-years of smoking | 0(0–0) | 30(15–50) | <0.001 |

| Duration of ABPA, in months | 262.50(89.00–610.75) | 165.00(49.00–517.00) | 0.800 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.00±3.54 | 21.13±2.73 | 0.107 |

| Peripheral blood cells | |||

| Leukocyte, × 109/L | 8.52±3.33 | 10.91±4.98 | 0.058 |

| Neutrophil, × 109/L | 5.09±3.01 | 7.33±2.85 | 0.030 |

| Neutrophil, % | 56.68±16.52 | 61.23±24.4 | 0.461 |

| Eosinophil, × 109/L | 0.48(0.09–0.80) | 0.70(0.06–1.75) | 0.968 |

| Eosinophil, % | 7.50(1.35–11.24) | 6.90(0.60–15.85) | 0.750 |

| Inflammatory indicator | |||

| NLR | 1.97(1.41–5.88) | 6.50(2.96–14.28) | 0.002 |

| CRP, mg/L | 3.03(0.98–10.96) | 48.16(9.72–126.7) | <0.001 |

| ESR, mm/h | 13.50(5.00–26.50) | 28.00(15.00–67.50) | 0.030 |

| Immunological tests | |||

| Total IgE, IU/mL | 2324.50(1276.25–2500.00) | 1927.00(1101.00–2500.00) | 0.526 |

| Sp-IgE, kUA/L | 2.22(0.55–14.03) | 3.5(0.73–6.62) | 0.219 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Asthma | 45(90.00%) | 7(63.64%) | 0.078 |

| COPD | 3(6.00%) | 7(63.64%) | <0.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 30(60.00%) | 2(18.18%) | 0.012 |

| Spirometry | |||

| FEV1/FVC | 62.62±16.12 | 53.00±14.2 | 0.077 |

| FEV1/pred | 63.11±25.60 | 48.07±26.27 | 0.095 |

| PEF, L/s | 4.68(3.31–6.53) | 2.71(2.35–3.67) | 0.027 |

| PEF, % | 73.50(48.83–94.48) | 39.6(30.55–56.90) | 0.024 |

| DLCO, % | 76.41±23.51 | 57.57±10.62 | 0.014 |

| DLCO/VA, mmol/min/kPa/L | 1.48(1.24–1.61) | 1.04(0.78–1.15) | <0.001 |

| Arterial blood gas | |||

| PaO2, mmHg | 76.46±13.15 | 72.91±10.14 | 0.417 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 41.50(38.75–44.25) | 40.00(39.00–42.5) | 0.326 |

| SaO2, % | 96.00(94.00–97.00) | 95.00(93.50–97.00) | 0.567 |

| Treatment | |||

| Glucocorticoids | 43(86.00%) | 11(100.00%) | 0.426 |

| Antifungal Drugs | 34(68.00%) | 7(63.64%) | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; DLCO, Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide; VA, Alveolar volume; ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FEV1/FVC, Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC); FEV1/pred, Percentage of FEV1 predicted; IgE, Immunoglobulin E; NLR, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PEF, Peak expiratory flow percentage; PaO2, Partial arterial oxygen pressure; PaCO2, Partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide; SaO2, Oxygen saturation; Sp-IgE, Aspergillus fumigatus specific IgE.

Table 4.

The Detailed Condition of the Death Group

| Died Patients | Age (Years) | Gender | Predisposing Conditions | Comorbidity | Cause of Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 64 | Male | COPD Asthma |

Coronary heart disease | Pneumomediastinum AECOPD Respiratory failure |

| Case 2 | 82 | Male | COPD | Coronary heart disease | AECOPD NSTEMI Respiratory failure |

| Case 3 | 83 | Male | COPD | Chronic pulmonary heart disease | AECOPD Respiratory failure |

| Case 4 | 74 | Male | Asthma | Coronary heart disease Acute cerebral infarction |

Coronary heart disease Acute cerebral infarction |

| Case 5 | 62 | Male | COPD Asthma |

Pulmonary tuberculosis | Pulmonary tuberculosis AECOPD Respiratory failure |

| Case 6 | 82 | Male | COPD | Chronic pulmonary heart disease | AECOPD Respiratory failure |

| Case 7 | 81 | Male | Asthma | Advanced colorectal cancer | Advanced colorectal cancer |

| Case 8 | 52 | Female | Asthma | Depression | Unknown |

| Case 9 | 77 | Male | COPD Asthma |

NSCLC | NSCLC AECOPD Respiratory failure |

| Case 10 | 69 | Female | Asthma | Advanced colorectal cancer | Advanced colorectal cancer |

| Case 11 | 76 | Male | COPD | Chronic pulmonary heart disease | AECOPD Heart failure Respiratory failure |

Abbreviations: AECOPD, Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSTEMI, Non-ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction; NSCLC, Non-small-cell lung cancer.

Results of Cox Regression Analysis

Cox regression analysis showed that higher CRP (HR = 1.017, 95% CI 1.004–1.031, P = 0.013) and complicating COPD (HR = 8.525, 95% CI 1.827–39.773, P = 0.006) were independent risk factors associated with mortality in patients with ABPA.

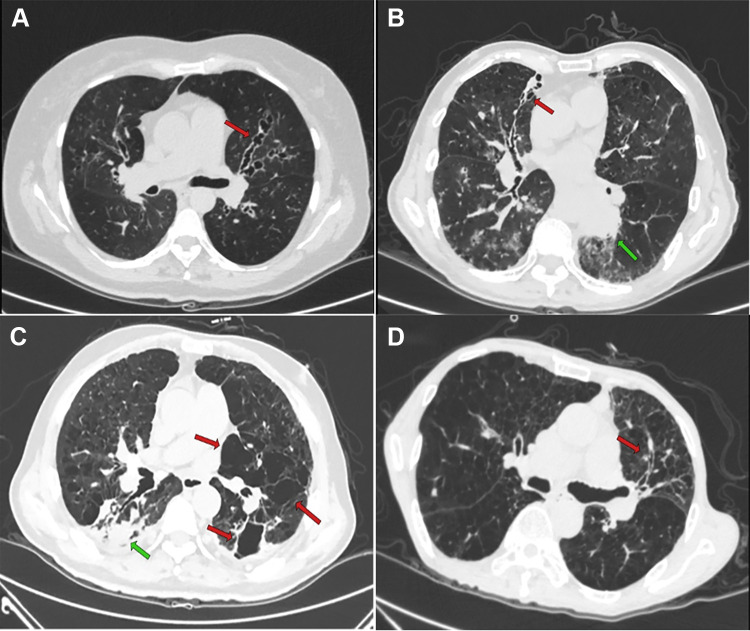

Comparison of Characteristics Between Patients Who Had ABPA with or Without CB

Smoking history (1 [6.25%] vs 20 [44.44%], P = 0.006), pack-years of smoking (0 [0–0] vs 0 [0–18.75], P = 0.025), and BMI (20.75 ± 3.29 kg/m2 vs 23.38 ± 3.27 kg/m2, P = 0.009) were significantly lower in patients with CB than in patients without CB. Eosinophil count (0.77 × 109/L [0.23–0.94 × 109/L] vs 0.48 × 109/L [0.05–0.71 × 109/L], P = 0.029) and Sp-IgE level (13.30 kUA/L [3.50–25.90 kUA/L] vs 0.93 kUA/L [0.54–6.10 kUA/L], P = 0.001) were significantly higher in patients who had ABPA with CB than in patients without CB (Table 5). And we showed several typical HRCT photographs of ABPA including 3 died patients (Figure 3).

Table 5.

Comparison of Characteristics Between Patients Who Had ABPA with or Without Central Bronchiectasis

| Central Bronchiectasis | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=16) | No (n=45) | ||

| Age, years | 50.94±19.06 | 58.60±17.35 | 0.145 |

| Male | 5(31.25%) | 26(57.78%) | 0.068 |

| Smokers | 1(6.25%) | 20(44.44%) | 0.006 |

| Pack-years of smoking | 0(0–0) | 0(0–18.75) | 0.025 |

| Dead | 1(6.25%) | 10(22.22%) | 0.294 |

| Duration of ABPA, in months | 592(105.00–631.00) | 154.5(73.00–427.50) | 0.018 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.75±3.29 | 23.38±3.27 | 0.009 |

| Peripheral blood cells | |||

| Leukocyte, ×109/L | 9.50±3.32 | 8.78±3.95 | 0.522 |

| Neutrophil, ×109/L | 5.46±2.84 | 5.57±3.21 | 0.899 |

| Neutrophil, % | 54.82±18.72 | 58.58±18.09 | 0.498 |

| Eosinophil, ×109/L | 0.77(0.23–0.94) | 0.48(0.05–0.71) | 0.029 |

| Eosinophil, % | 9.6(2.61–11.15) | 6.4(0.45–13.97) | 0.144 |

| Inflammatory indicator | |||

| NLR | 1.90(1.21–3.99) | 4.14(1.5–7.71) | 0.375 |

| CRP, mg/L | 3.94(2.25–11.70) | 8.09(1.23–41.37) | 0.910 |

| ESR, mm/h | 26.00(17.00–29.00) | 12.00(5.25–28.75) | 0.160 |

| Immunological tests | |||

| Total IgE, IU/mL | 2248.00(1011.00–2500.00) | 2322.00(1262.75–2500.00) | 0.398 |

| Sp-IgE, kUA/L | 13.30(3.50–25.9) | 0.93(0.54–6.10) | 0.001 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Asthma | 15(93.75%) | 37(82.22%) | 0.480 |

| COPD | 1(6.25%) | 9(20.00%) | 0.377 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 8(50.00%) | 24(53.33%) | 0.819 |

| Spirometry | |||

| FEV1/FVC | 54.44±18.95 | 62.64±14.77 | 0.112 |

| FEV1/pred | 50.78±29.71 | 62.97±24.54 | 0.153 |

| PEF, L/s | 3.16(2.82–6.52) | 3.90(3.16–5.75) | 0.078 |

| PEF, % | 49.50(38.20–94.2) | 65.25(43.33–87.08) | 0.160 |

| DLCO, % | 66.68±31.97 | 74.10±18.19 | 0.317 |

| DLCO/VA, mmol/min/kPa/L | 1.48(1.17–1.60) | 1.24(1.04–1.55) | 0.616 |

| Arterial blood gas | |||

| PaO2, mmHg | 75.21±13.57 | 75.78±12.21 | 0.889 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 41.00(40.00–52.00) | 41(38.00–43.00) | 0.101 |

| SaO2, % | 95.00(94.00–97.00) | 96.00(94.00–97.00) | 0.866 |

| Treatment | |||

| Glucocorticoids | 15(93.75%) | 39(86.67%) | 0.759 |

| Antifungal Drugs | 13(81.25%) | 28(62.22%) | 0.164 |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; DLCO, Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide; VA, Alveolar volume; ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FEV1/FVC, Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC); FEV1/pred, Percentage of FEV1 predicted; IgE, Immunoglobulin E; NLR, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PEF, Peak expiratory flow percentage; PaO2, Partial arterial oxygen pressure; PaCO2, Partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide; SaO2, Oxygen saturation; Sp-IgE, Aspergillus fumigatus specific IgE.

Figure 3 .

HRCT scans of patients with ABPA.

Discussion

ABPA presents with symptoms that are similar to those of asthma. They include coughing, wheezing, and shortness of breath. Chronic airway diseases, including asthma and COPD, which are the background diseases of ABPA, have a high incidence in the world. Various research studies were performed to assess the characteristics and prognosis of ABPA with asthma, but few studies paid attention to the characteristics and prognosis of ABPA with COPD, although some studies showed that Aspergillus was associated with frequent exacerbations and higher mortality in COPD.29

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the long-term follow-up data of 61 patients who had ABPA with an average follow-up time of 50.38 months (range, 3–143 months), and we reported that the all-cause mortality rate of ABPA with COPD (70%) was significantly higher than that of ABPA without COPD (7.84%). The Log rank test showed that the mean survival time of ABPA with COPD was 37 months, which was much shorter than that of ABPA without COPD (129.98 months). The cause of death in patients who had ABPA with and without COPD was definitely different. Most patients with COPD and ABPA died of respiratory diseases, such as AECOPD, while death of patients without COPD was usually due to a malignant tumor, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

However, univariate analysis showed that old age, poor pulmonary function, and severe systemic inflammatory reaction were closely related to the higher mortality of ABPA. The Cox regression analysis showed that complicating COPD (HR = 8.525, 95% CI 1.827–39.773, P = 0.006) was one of the independent risk factors associated with mortality in patients with ABPA. We suppose that all these significant univariate factors are related to COPD.

The main reasons for the increased mortality in patients with COPD include the following: Firstly, the mean age of patients with ABPA and COPD in this study was 76 years, which was much higher than that of patients without COPD (53 years). The mean age of three patients with ABPA and COPD was 77 years in the study by Sun.6 Another study showed that the mean age of 10 patients with ABPA and COPD was 59 years,30 which was in line with the age characteristic of patients with COPD in this study. Therefore, advanced age is a prominent feature of patients with ABPA and COPD, which is in accordance with the different onset age of patients with COPD and asthma. Asthma often occurs in childhood and usually before the age of 40 years, while COPD usually occurs after the age of 50 years in smokers. On the other hand, although the incidence of ABPA in COPD might not be lower than that in asthma,11 the proportion of of ABPA with COPD was much lower than that of ABPA with asthma in most of the current case studies. A previous study in China showed that none of the 77 patients with ABPA had COPD.31 In another study, 1 out of 46 patients with ABPA had COPD,32 and in a recent retrospective analysis by Zeng, 3 out of 193 patients with ABPA had COPD.18 It can be speculated that a large number of patients with COPD and ABPA are underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, leading to a higher age at the time of first diagnosis in these patients. These two aspects lead to the fact that the age of patients with ABPA and COPD is much higher than that of ABPA patients without COPD. A delayed diagnosis and treatment will lead to gradual aggravation of clinical symptoms, severe airflow obstruction, CB, and other structural lung damage, which seriously affect the quality of life and survival time of patients.

Secondly, patients with COPD have more severe airflow obstruction and significantly reduced diffusing function, which was significantly associated with increased mortality. The univariate analysis and Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that reduced pulmonary ventilation function and diffusing capacity were closely related to COPD and increased mortality. Smoking history was closely associated with genesis and development of COPD and worse pulmonary function, which was also demonstrated in this study. Although a retrospective study found that DLCO/VA was lower in patients who had ABPA with CB,18 CB had no significant association with DLCO/VA in this study. Thus, the important factor leading to the decline in pulmonary ventilation and diffusing capacity in our patients was coexisting COPD, and not CB. Therefore, COPD-induced decline in pulmonary function is an important cause of death in patients with ABPA.

In addition to the significant differences in age and pulmonary function, the inflammatory characteristics were significantly different between patients with COPD and without COPD. Univariate analysis showed that patients with COPD had significantly a higher neutrophil count, neutrophil percentage, CRP and NLR, but the indicators related to ABPA-characteristic allergic inflammation, such as blood eosinophil count and eosinophil percentage, were significantly lower. Agarwal et al found that elderly patients with ABPA had lower serum total IgE and Sp-IgE levels and less bronchiectasis,21 suggesting that patients with ABPA aged over 60 years and with COPD showed a hypoallergenic inflammatory reaction but a severe neutrophilic inflammatory reaction. NLR and CRP are sensitive indicators of systemic infection, and previous studies have found that these indicators are associated with an increased risk of acute exacerbation, hospitalization, and early death in patients with COPD.33–36 We also analyzed the impact of CB on mortality. ABPA with CB did not increase the risk of mortality. Besides, our study also showed that the inflammatory characteristics of patients with COPD were significantly different from those of patients with CB. The former was dominated by increased CRP and neutrophil count, while the latter was dominated by increased ABPA-characteristic allergic inflammation indicators, such as eosinophil count and Sp-IgE level. Previous studies suggested that patients with ABPA and CB have higher levels of total IgE and Sp-IgE, more severe immunoreactivity, more aggressive clinical form and symptoms, and more frequent exacerbations.17,37–39 The prominent inflammatory characteristic of patients with ABPA and COPD suggests that patients with COPD may have more severe airway infections and the type and mechanism of airway inflammation in COPD with ABPA are different from those in typical asthma with ABPA. Th2 inflammation reaction and fungal colonization of the airways are important mechanisms for the pathogenesis of ABPA.40 There is an interaction and overlap between infection and Th2 inflammation of the airways caused by fungal colonization. Airway inflammation was more likely secondary to fungal colonization in patients who had COPD instead of persistent allergy. It remains to be determined whether there are different pathways of airway inflammation in patients with COPD and ABPA and patients with classic asthma and ABPA.

The clinical characteristics and pathogenesis of patients with ABPA and COPD may be different from those of patients with ABPA but without COPD, which can lead to significant differences in mortality. Thus, we should increase the screening of Aspergillus sensitization and ABPA in patients with COPD to reduce misdiagnosis, improve early detection and treatment, and lower mortality. In addition, due to the limited treatment methods for ABPA, glucocorticoids and antifungal drugs are the main medications, and a higher priority is given to glucocorticoids. However, physicians are usually more cautious when applying glucocorticoids in patients with COPD and ABPA, considering their advanced age, more underlying diseases, and worse immune status. Some patients often fail to take a sufficient amount of glucocorticoids and complete the full course of treatment with glucocorticoids. The mechanism of ABPA in COPD should be explored through more research studies to identify the differences from that of ABPA based on classic asthma. It is necessary to further optimize the treatment plan according to the pathogenesis and clinical characteristics of patients with COPD and ABPA to improve their compliance, thereby improving the treatment effect and reducing the mortality.

In summary, the all-cause mortality for ABPA with COPD was much higher than that for ABPA without COPD. Older age, poorer pulmonary function, and a more severe neutrophilic inflammatory reaction were closely related to higher mortality of ABPA with COPD. Higher CRP and complicating COPD were independent risk factors for mortality in patients with ABPA. Patients with COPD should be routinely evaluated for Aspergillus sensitization and ABPA to promote early identification and intervention of severe and high-risk patients and ultimately reduce mortality.

However, our study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. It was a single-center retrospective study with a small sample size. The mortality rate obtained in this study cannot be extrapolated to all patients with ABPA. The laboratory had set the upper limit of the total IgE detection value at 2500 IU/mL, which may have influenced the significance of total IgE. Further, some new biological targeted drugs, such as the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab, were not included in our study.41 Moreover, patients with COPD have a higher mortality rate versus age-matched controls. We did not compare the difference in mortality between COPD with and without ABPA in order to analyze how ABPA can contribute to mortality in patients with COPD and ABPA. Hence, a prospective large-scale research study with a longer follow-up time period is needed to explore the difference in all-cause mortality between ABPA with and without COPD and related risk factors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Youth Scientific Research Cultivation Project of Peking University People’s Hospital Research and Development Fund (RDY2021-19). We thank Medjaden Inc. for scientific editing of this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Youth Scientific Research Cultivation Project of Peking University People’s Hospital Research and Development Fund (RDY2021-19).

Abbreviations

ABPA, Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis;; AECOPD, Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI, Body mass index; CB, Central bronchiectasis; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; DLCO, Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide; VA, Alveolar volume; ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FEV1, Forced expiratory volume in one second; FEV1/pred, Percentage of FEV1 predicted; FVC, Forced vital capacity; HRCT, High-resolution computed tomography; IgE, Immunoglobulin E; NLR, Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; NSCLC, Non-small-cell lung cancer; NSTEMI, Non-ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction; PEF, Peak expiratory flow percentage; PaO2, Partial arterial oxygen pressure; PaCO2, Partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide; SaO2, Oxygen saturation; Sp-IgE, Aspergillus fumigatus specific IgE; Th2, T helper cell type 2.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kosmidis C, Denning DW. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Thorax. 2015;70(3):270–277. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bains SN, Judson MA. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Clin Chest Med. 2012;33(2):265–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC. Global burden of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with asthma and its complication chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in adults. Med Mycol. 2013;51(4):361–370. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.738312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma YL, Zhang WB, Yu B, Chen YW, Mu S, Cui YL. Prevalence of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in Chinese patients with bronchial asthma. Chin J Tuberculosis Respir Dis. 2011;34(34):909–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin JM, Liu XF, Sun YC. The prevalence of increased serum IgE and Aspergillus sensitization in patients with COPD and their association with symptoms and lung function. Respir Res. 2014;15:130. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0130-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu XF, Sun YC, Jin JM, Li R, Liu Y. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: report of 3 cases. Chin J Tuberculosis Respir Dis. 2013;36(10):5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal RH, Basanta G, Dheeraj A, et al. Aspergillus hypersensitivity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: COPD as a risk factor for ABPA? Med Mycol. 2010;48(7):988–994. doi: 10.3109/13693781003743148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasteur MC, Helliwell SM, Houghton SJ, et al. An investigation into causative factors in patients with bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(4 Pt 1):1277–1284. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9906120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens DA, Moss RB, Kurup VP, et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in cystic fibrosis--state of the art: cystic fibrosis foundation consensus conference. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(Suppl 3):S225–S264. doi: 10.1086/376525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agarwal R, Srinivas R, Jindal SK. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis complicating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mycoses. 2008;51(1):83–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muthu V, Prasad KT, Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, Agarwal R. Obstructive lung diseases and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2021;27(2):105–112. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.López-Campos JL, Tan W, Soriano JB. Global burden of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(1):14–23. doi: 10.1111/resp.12660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiew PY, Ko FWS, Pang SL, et al. Environmental fungal sensitisation associates with poorer clinical outcomes in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2):2000418. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00418-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Agbetile J, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus during stable state and exacerbations of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(1):64–71. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00162912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorino C, Pedone C, Scichilone N. Fifteen-year mortality of patients with asthma-COPD overlap syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;34:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu HW, Mao B, Wei P, et al. The clinical characteristics and prognosis of ABPA are closely related to the mucus plugs in central bronchiectasis. Clin Respir J. 2020;14(2):140–147. doi: 10.1111/crj.13111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal R, Garg M, Aggarwal AN, Saikia B, Gupta D, Chakrabarti A. Serologic allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA-S): long-term outcomes. Respir Med. 2012;106(7):942–947. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeng YY, Xue XM, Cai H, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: a retrospective cohort study. J Asthma Allergy. 2022;15:53–62. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S345427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Behera D, Chakrabarti A. Utility of IgE (total and Aspergillus fumigatus specific) in monitoring for response and exacerbations in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2016;59(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/myc.12423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muthu V, Sehgal IS, Prasad KT, et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) sans asthma: a distinct subset of ABPA with a lesser risk of exacerbation. Med Mycol. 2020;58(2):260–263. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myz051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthu V, Sehgal IS, Prasad KT, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in the elderly. Mycoses. 2022;65(1):71–78. doi: 10.1111/myc.13388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang SJ, Zhang J, Zhang CP, Shao CZ. Clinical characteristics of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with and without bronchiectasis. J Asthma. 2021;58(1):1–7. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2019.1656230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiew PY, Lim AYH, Keir HR, et al. High frequency of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in bronchiectasis-COPD overlap. Chest. 2022;161(1):40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asthma Group of the Respiratory Diseases Branch of the Chinese Medical Association. Experts consensus on diagnosis and treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Natl Med J China. 2017;34:2650–2656. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Group of the Respiratory Diseases Branch of the Chinese Medical Association. The guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of COPD (2013 revised edition). Chin J Front Med Sci. 2014;2:67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lv XD. The diagnostic criteria of the guidelines for the prevention and treatment of bronchial asthma (2016 edition). Chin J Tuberculosis Respir Dis. 2016;39(9):675–697. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adult Bronchiectasis Diagnosis and Treatment Expert Consensus Writing Group. Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of adult bronchiectasis (2012 edition). Chin J Crit Care Med. 2012;5(5):20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansell DM, Strickland B. High-resolution computed tomography in pulmonary cystic fibrosis. Br J Radiol. 1989;62(733):1–5. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-62-733-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiew PY, Dicker AJ, Keir HR, et al. A high-risk airway mycobiome is associated with frequent exacerbation and mortality in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(3):2002050. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02050-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang MY, Qian YJ, Lin L, Wang HM. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: report of 10 cases. Chin J Tuberculosis Respir Dis. 2019;42(7):543–545. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang MQ, Gao JM. Clinical analysis of 77 patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Acta Acad Med Sinicae. 2017;39(3):352–357. doi: 10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.2017.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou MF, Li S, Yang Y, et al. Clinical features and reasons for missed diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Natl Med J China. 2019;99(16):1221–1225. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2019.16.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groenewegen KH, Postma DS, Hop WCJ, Wielders PLML, Schlösser NJJ, Wouters EFM. Increased systemic inflammation is a risk factor for COPD exacerbations. Chest. 2008;133(2):350–357. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lonergan M, Dicker AJ, Crichton ML, et al. Blood neutrophil counts are associated with exacerbation frequency and mortality in COPD. Respir Res. 2020;21(1):166. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01436-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao CY, Liu XL, Tang Z. Prognostic role of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio for hospital mortality in patients with AECOPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:2285–2290. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S141760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiong W, Xu M, Zhao YF, Wu XL, Pudasaini B, Liu JM. Can we predict the prognosis of COPD with a routine blood test? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:615–625. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S124041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patterson K, Strek ME. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7(3):237–244. doi: 10.1513/pats.200908-086AL [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agarwal R, Gupta D, Aggarwal AN, Behera D, Jindal SK. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: lessons from 126 patients attending a chest clinic in north India. Chest. 2006;130(2):442–448. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar R, Chopra D, Chopra RD. Evaluation of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with and without central bronchiectasis. J Asthma. 2002;39(6):473–477. doi: 10.1081/JAS-120004905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denning DW, Pashley C, Hartl D, et al. Fungal allergy in asthma-state of the art and research needs. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4:14. doi: 10.1186/2045-7022-4-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma YL. The use of biological agents for the treatment of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chin J Tuberculosis Respir Dis. 2019;42(11):864–868. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2019.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]