Abstract

Background & objectives:

Data from the National Clinical Registry for COVID-19 (NCRC) were analyzed with an aim to describe the clinical characteristics, course and outcomes of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the third wave of the pandemic and compare them with patients admitted earlier.

Methods:

The NCRC, launched in September 2020, is a multicentre observational initiative, which provided the platform for the current investigation. Demographic, clinical, treatment and outcome data of hospitalized COVID-19 patients were captured in an electronic data portal from 38 hospitals across India. Patients enrolled during December 16, 2021 to January 17, 2022 were considered representative of the third wave of COVID-19 and compared with those registered during November 15 to December 15, 2021, representative of the tail end of the second wave.

Results:

Between November 15, 2021 and January 17, 2022, 3230 patients were recruited in NCRC. Patients admitted in the third wave were significantly younger than those admitted earlier (46.7±20.5 vs. 54.6±18 yr). The patients admitted in the third wave had a lower requirement of drugs including steroids, interleukin (IL)-6 inhibitors and remdesivir as well as lower oxygen supplementation and mechanical ventilation. They had improved hospital outcomes with significantly lower in-hospital mortality (11.2 vs. 15.1%). The outcomes were better among the fully vaccinated when compared to the unvaccinated or partially vaccinated.

Interpretation & conclusions:

The pattern of illness and outcomes were observed to be different in the third wave compared to the last wave. Hospitalized patients were younger with fewer comorbidities, decreased symptoms and improved outcomes, with fully vaccinated patients faring better than the unvaccinated and partially vaccinated ones.

Key words: Delta variant, demography, hospitalized, Omicron variant, outcome, SARS-CoV-2

The first case of COVID-19 in India was reported on January 30, 20201, and since then until January 27, 2022, over 38 million cases and 0.48 million deaths were reported2,3. The pandemic has witnessed two major waves in India, with some States/cities bearing the major burden of cases. India witnessed the third wave of COVID-19, which started around mid-December 2021. This upsurge in cases has been attributed to a highly mutated and transmissible variant of SARS-CoV-2, i.e. Omicron (B.1.1.529)4. Since the first case of Omicron was reported from South Africa, many countries have observed a similar sharp rise followed by precipitous fall in the number of COVID-19 cases1,5. The clinical characteristics of the hospitalized patients in this wave have not yet been well documented. Although some preclinical studies have suggested a lower virulence for this variant of concern (VOC), conclusive evidence regarding the virulence is yet to be established6. The aim of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics, course and outcomes of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 during the third wave of pandemic in India and compare them with patients admitted in hospitals in the preceding month, representative of the tail end of the last wave.

Material & Methods

The National Clinical Registry for COVID-19 (NCRC) is a prospective multicentre clinical database, initiated and maintained by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) and ICMR-National Institute of Medical Statistics (NIMS), New Delhi. The structure and protocol of the registry are available in the public domain7. Currently, 38 tertiary care hospitals across India are enrolling hospitalized COVID-19 patients in this registry, more details are available elsewhere8.

The diagnosis of COVID-19 was based on real-time (RT) - PCR, rapid antigen test or cartridge-based nuclear amplification tests. Patients were admitted as per the local/national guidelines and managed as per the clinical discretion of the attending physicians, based on the available National and State guidelines.

Rationale for choosing the time-periods: The Omicron variant was first reported from South Africa on November 24, 2021 and from India on December 2, 20214,9,10. The rapid rise in number of cases observed since mid-December onwards was considered as the third wave of COVID-19 in India, and attributed to the high transmissibility of the Omicron VOC11. Patients admitted between December 16 and January 17, 2022 were considered to be representative of the third wave. A prevailing scenario of Omicron infection in some States and mixed prevalence of both Omicron and Delta variants in some other States characterized the India’s COVID-19 pandemic during this period. The records of the preceding month, representative of the tail end of the second wave, were considered for comparison. Thus, the two time periods analyzed were November 15 to December 15, 2021 and December 16, 2021 to January 17, 2022. Activities of the NCRC were approved by the Central Ethics Committee for Human Research at the ICMR and the respective Institutional Ethics Committees of the participating sites. As anonymized data were retrieved from hospital case files, a waiver of consent was granted.

Demographic, clinical, treatment and outcome data were collected in an e-data capture portal, developed by ICMR-NIMS, by a designated team in each of the participating hospital.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using STATA v14 (College Station, TX, USA). Categorical data were presented as frequency and proportions, while continuous data were summarized as mean or median, as appropriate. Comparisons between the two time periods were made using Chi-square/Fisher’s exact and Student’s t test/rank-sum test, as applicable.

Results & Discussion

Between November 15, 2021 and January 17, 2022, 3230 confirmed COVID-19 cases were enrolled in the NCRC, with 620 and 2610 enrolments in the aforementioned two time periods, respectively. The information was collected from admitted patients in 34 centres out of the 38 participating centres (Box).

Box.

Geographical zone-wise spread of participating centres.

| North | North- East |

|---|---|

| Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh Medanta Institute of Education and Research, Gurugram, Haryana Christian Medical College, Ludhiana, Punjab Pandit Bhagwat Dayal Sharma Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana | North-Eastern Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical Sciences, Shillong, Meghalaya Naga Hospital Authority, Kohima, Nagaland. |

| West | East |

| All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur, Rajasthan Rajasthan University of Medical Sciences, Jaipur, Rajasthan Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan Sardar Patel Medical College, Bikaner, Rajasthan Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital & Research Centre, Pune, Maharashtra Smt. NHL Muncipal Medical College, Ahmedabad, Gujarat CIMS Hospital, Ahmedabad, Gujarat Sumandeep Vidyapeeth and Institution, Deemed to be University & Dhiraj Hospital, Vadodara, Gujarat GMERS Medical College and Hospital, Himmatnagar, Gujarat | All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, Odisha Hitech Medical college, Bhubaneswar, Odisha Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research, Kolkata, West Bengal Medical College, Kolkata, West Bengal Infectious Diseases & Beliaghata General Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal College of Medicine and Sagore Dutta Hospital, Kamarhati, Kolkata, West Bengal Tata Medical Centre, Kolkata, West Bengal All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, Chattisgarh Shaheed Nirmal Mahto Medical College, Dhanbad, Jharkhand Government Medical College, Jagdalpur, Chhattisgarh |

| South | Central |

| Bowring and Lady Curzon Medical College and Research Institute, Bengaluru, Karnataka Gulbarga Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalburgi, Karnataka Gandhi Medical College, Secunderabad, Telangana St. John’s Medical College & Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka | All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh J.N. Medical College, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh sRMRC Gorakhpur & BRD Medical College, Gorakhpur , Uttar Pradesh |

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients registered before and during the third wave of COVID-19 are described in the Table. Patients admitted during the end of the second wave were significantly older than the third wave (54.6±18 vs. 46.7±20 yr, P<0.001). In the current wave, the highest proportion of patients belonged to the age group of 19-39 and 40-59 yr (31.6 and 31.9%, respectively). As compared to the preceding month, proportion of children in the age group of 0-18 yr in December 2021 - January 2022 period was higher, whereas proportion of elderly (≥60 yr) was lower.

Table .

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients registered during two consecutive months before and during third wave of COVID-19 (n=3230)

| Characteristics | November 15 - December 15, 2021 (n=620) | December 16, 2021 - January 17, 2022 (n=2610) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age±SD (completed yr) | 54.6±18 | 46.7±20.5 | <0.001 |

| Males | 393 (63.4) | 1576 (60.4) | 0.17 |

| Age categories (yr) | |||

| 0–18 | 20 (3.2) | 162 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| 19–39 | 110 (17.7) | 825 (31.6) | |

| 40–59 | 194 (31.3) | 833 (31.9) | |

| ≥60 | 272 (47.7) | 790 (30.3) | |

| Vaccinated with at least one dose of anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | 381 (61.5) | 1454 (55.7) | 0.009 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| At least one comorbidity | 374 (60.3) | 1316 (50.4) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 258 (41.6) | 728 (27.9) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 178 (28.7) | 500 (19.2) | <0.001 |

| Chronic cardiac disease | 50 (7.7) | 204 (7.8) | 0.95 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 27 (4.2) | 59 (2.3) | 0.007 |

| Chronic liver disease | 13 (1.9) | 37 (1.4) | 0.72 |

| Asthma | 17 (2.7) | 57 (2.2) | 0.40 |

| Symptom profile* | |||

| Symptomatic | 479 (77.2) | 1944 (74.6) | <0.15 |

| Fever | 326/479 (68.1) | 1151/1944 (59.2) | <0.001 |

| Cough | 302/479 (63.1) | 1023/1944 (52.6) | <0.001 |

| Breathing difficulty | 206/479 (43) | 517/1944 (26.6) | <0.001 |

| Sore throat | 74/479 (15.5) | 418/1944 (21.5) | 0.001 |

| Loss of smell or taste | 51/479 (10.7) | 45/1944 (2.3) | <0.001 |

*Proportion of specific symptoms is calculated among the symptomatic patients. Chi-square test was applied to compare proportion. Unpaired t test was applied to compare means. P<0.05 was considered significance. Values are expressed as n (%), unless specified. SD, standard deviation

Similar pattern was seen in the recent wave of COVID-19 in South Africa where the patients hospitalized during the current wave due to Omicron VOC were younger (median age: 36 vs. 59 yr) than those in the preceding wave12. This is an important finding, considering that younger age group is considered healthier and usually has lower comorbidities, in comparison to the old13.

Higher proportion of young being admitted also reflected an improved health-seeking behaviour post-second wave. Vaccination strategy in India was pragmatic and risk-based, making it plausible that a significant proportion of young adults might still be unvaccinated13. Staggered opening of educational institutions/workplaces could be one of the reasons for the young being exposed to infection14.

In the current wave, the overall proportion of patients with comorbidities [1316 (50.4%)] were less as compared to the previous time period [374 (60.3%)], though the proportion of children (0-18 yr) with comorbidities increased in the current wave [previous wave: 3/19 (15%); current wave: 54/162 (33.2%), P<0.09], which was not significant. Commonly recognized symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection were observed to be significantly lower in this wave, except for sore throat, which occurred in higher proportion (15.5 vs. 21.5%, P=0.001). Fever was associated with chills in 4.8 per cent of patients in the second wave and 2.3 per cent of patients in the third wave.

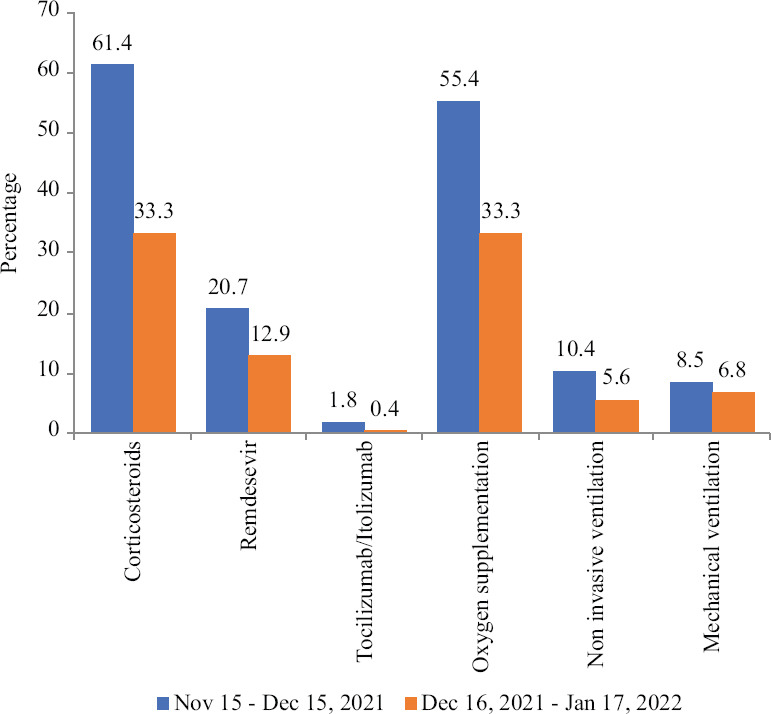

As on January 17, 2022, complete dataset was available for 2825 patients and was analyzed for treatment details and outcomes. Figure shows the drug and supportive therapies used in the two epochs. The usage of drugs and supportive therapy in the form of oxygen supplementation (invasive and non-invasive) had significantly reduced in the third wave. The median duration of treatment with remdesevir was five days [interquartile range (IQR): 4, 5] in both the waves. Forty two patients had a history of previous COVID-19 infection, 37 of them being in the third wave, the difference not being significant (0.7 vs. 1.5%). Chest computed tomography data were available for 134 patients and 304 patients, from the second and third wave, respectively. In the second wave, 97 per cent of these fell in Co-RADS category 4, 5 and 6, whereas in the third wave, the same proportion was 96 per cent. The difference was not significant.

Figure.

Drug and supportive therapies requirement during two subsequent months before and during the third wave of COVID-19 (n=2825). The proportion of patient receiving drugs including corticosteroids, remdesevir, tocilizumab and supportive therapy, were higher during November 15 to December 15, 2021 than the subsequent one month.

Of the 3230 patients, random blood sugar was available in 801 patients. Among these patients, the median (IQR) of the highest recorded random blood sugar after starting corticosteroids was 268 (170, 358) mg/dl, while the highest recorded blood sugar during the hospital stay among patients who did not receive steroids was 133 (106, 183) mg/dl, P<0.001. The mean oxygen saturation at admission with or without oxygen supplementation during the second wave was 89.7±8.8 per cent and 93.9±7.6 per cent during the third wave.

In-hospital complications including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis/septic shock and acute kidney injury were reported in fewer cases in the month representing third wave [ARDS: 9.6% (n=54) vs. 3.2% (n=72), P=0.001; sepsis/septic shock: 5% (n=28) vs. 1.9% (n=44), P<0.001; acute kidney injury: 3% (n=18) vs. 1.6% (n=35), P=0.04]. The median duration of hospital stay was five (IQR: 4, 9) days during the second wave and five (IQR: 3, 7) days in the third wave. The in-hospital mortality was 15.1 (n=82) and 11.2 per cent (n=240), respectively, during the two epochs, P=0.01. Proportion of patients dying was not significantly different across age categories.

It was noteworthy that in this analysis, the outcome characteristics significantly improved, with a significant reduction in utilization of drug as well as supportive therapies, which could be taken as a surrogate marker for considering the third wave as being less severe in nature. Younger patients with decreased symptoms and improved outcomes were recorded in the third wave. Higher proportion of younger individuals being admitted might be a reason of improved outcomes, considering that the ability to fight infections is higher among young15. Studies originating from South Africa and the United Kingdom (UK) report similar findings12,16,17.

The supportive therapy and outcome of participants enrolled over the time period of this study were disaggregated as per vaccination status. Vaccinated individuals had lower requirement of oxygen [497 (33.7%) vs. 568 (42.4%), P<0.001] or mechanical ventilation [78 (5.4%) vs. 124 (9.2%), P<0.001] and suffered lower in hospital mortality [102 (7.1%) vs. 220 (17.6%), P<0.001] compared to unvaccinated or partially vaccinated. Further, the requirement for mechanical ventilation was lower among patients vaccinated with two doses of anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine [63/1266 (4.9%) vs. 91/1344 (6.8%), P=0.05] compared to single dose, though not significant.

The possibility of immune escape of this VOC, both from natural infection and post-vaccination, is a global concern. The recent UK report also corroborates this finding that vaccination protects against severe disease requiring hospitalization, irrespective of the variant in question16. Thus, vaccination remains the mainstay in the fight against severe COVID-19.

The study had a few limitations. First, genomic sequencing was not performed though the current epidemiology of infections across the country suggests that the highly transmissible Omicron VOC is the predominant driver of this upsurge18. The weekly reports of the INSACOG suggest that the predominant circulating variant during mid-November and early December was Delta, while it was Omicron in the subsequent month18. All investigations are done as per the treating physician’s discretion with no additional investigations for the purpose of the registry. The data are collected primarily from medical records, which in most cases are paper-based and may result in missing information. Due to these reasons, the date of vaccination among the patients was incompletely captured and hence was not analyzed. In addition, the registry is a dynamic data collection platform. At any point in time, the outcome data are unavailable for a considerable number of patients as they have not yet achieved the outcome.

The third wave of COVID-19 pandemic in India, presumably being driven by Omicron VOC, appeared to be milder in terms of course of illness and final outcomes. Younger patients, below 40 yr of age, were admitted in greater proportions. Vaccinated individuals fared better with higher recovery rates. However, COVID appropriate behaviour needs to be continued to avoid complications and mortality.

Acknowledgment:

Authors acknowledge Dr Sartaj Hussain, Scientist B; Shri Asif Kavethkar, Sr Technician, ICMR-RMRC, Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: National Clinical Registry for COVID-19 is funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Andrews MA, Areekal B, Rajesh KR, Krishnan J, Suryakala R, Krishnan B, et al. First confirmed case of COVID-19 infection in India:A case report. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:490–2. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2131_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 – 25 January. 2022. [accessed on January 27, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-up date-on-covid-19---25-january-2022 .

- 3.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Home. [accessed on January 27, 2022]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/

- 4.GISAID – hCov19 variants. accessed on January 21, 2022. Available from: https://www.gisaid.org/hcov19-variants/

- 5.Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE), Johns Hopkins University of Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center. COVID-19 dashboard. [accessed on January 21, 2022]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html .

- 6.Diamond M, Halfmann P, Maemura T, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Iida S, Kiso M, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 Omicron virus causes attenuated infection and disease in mice and hamsters. Res Sq. 2021 Doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1211792/v1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Indian Council of Medical Research. National clinical registry: What is it? [accessed on January 21, 2022]. Available from: https://www.icmr.gov.in/tab1ar1.html .

- 8.Kumar G, Mukherjee A, Sharma RK, Menon GR, Sahu D, Wig N, et al. Clinical profile of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in first & second wave of the pandemic:Insights from an Indian registry based observational study. Indian J Med Res. 2021;153:619–28. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.ijmr_1628_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Archived: WHO timeline – COVID-19. [accessed on January 21, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19 .

- 10.World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. [accessed on January 24, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/what-we-do/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants .

- 11.Karim SSA, Karim QA. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant:A new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:2126–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02758-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maslo C, Friedland R, Toubkin M, Laubscher A, Akaloo T, Kama B. Characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized patients in South Africa during the COVID-19 Omicron wave compared with previous waves. JAMA. 2022;327:583–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandal S, Arinaminpathy N, Bhargava B, Panda S. India's pragmatic vaccination strategy against COVID-19:A mathematical modelling-based analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e048874. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chernozhukov V, Kasahara H, Schrimpf P. The association of opening K-12 schools with the spread of COVID-19 in the United States:County-level panel data analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2103420118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2103420118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. [accessed on January 24, 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health .

- 16.Imperial College London. Report 50 – Hospitalisation risk for omicron cases in England. [accessed on January 24, 2022]. Available from: http://www.imperial.ac.uk/medicine/departments/school-public-health/in fectious-disease-epidemiology/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-50-severity-omicron/

- 17.Wolter N, Jassat W, Walaza S, Welch R, Moultrie H, Groome M, et al. Early assessment of the clinical severity of the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant in South Africa:A data linkage study. Lancet. 2022;399:437–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00017-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science – Technology. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Inida. INSACOG weekly bulletin. [accessed on January 24, 2022]. Available from: https://dbtindia.gov.in/sites/default/files/INSACOG%20WEEKLY%20BULLETIN%2010-01-2022.pdf .