Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST), often arising from a (plexiform) neurofibroma, is one of the hallmark complications of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) characterized by aggressive behavior [10]. The genetic background is complex and heterogeneous, with the initiating biallelic NF1 inactivation followed by a cascade of acquired mutations driving malignant progression. Amplification of receptor tyrosine kinase genes, have also been observed, and models demonstrated responses to the corresponding therapeutic blockades [7–9]. Fusion genes are rarely investigated in NF1-related MPNSTs [5]. We describe subclonal NTRK fusion genes in a subset of such tumors (Fig. 1), thereby potentially providing additional treatment options.

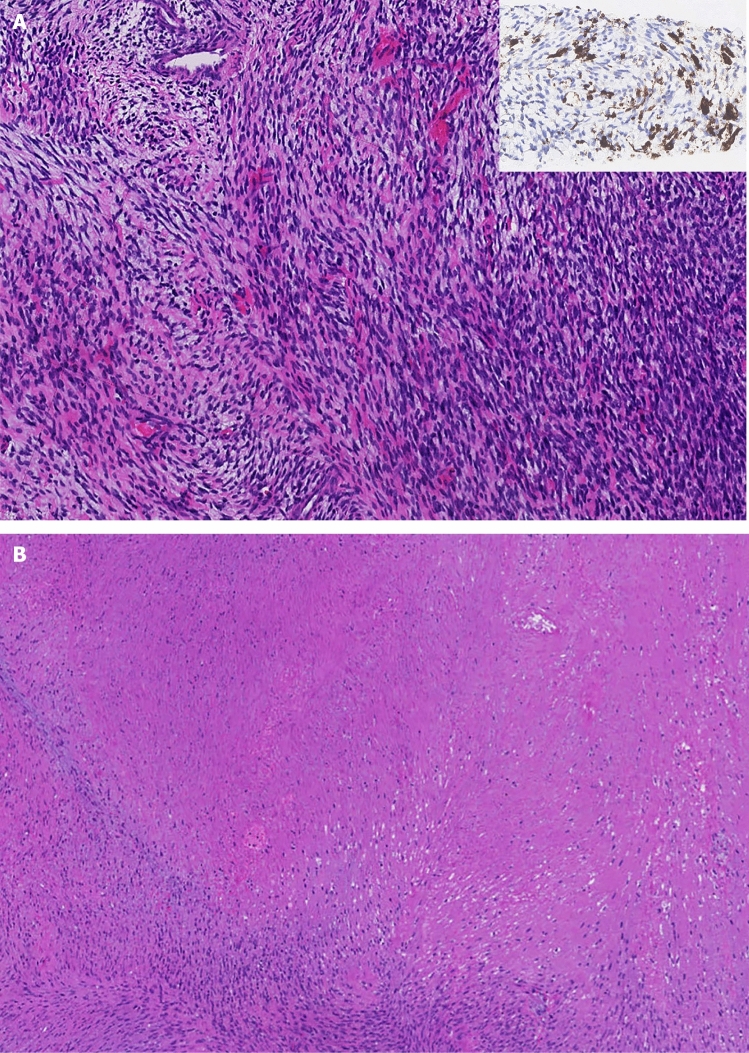

Fig. 1.

Morphological features of Case 1. a Primary biopsy showing an atypical cellular spindle cell tumor consistent with MPNST. Inset: partial pan-TRK expression. Magnification × 8. b First resection specimen depicted ~ 60% tumor necrosis. Magnification × 3

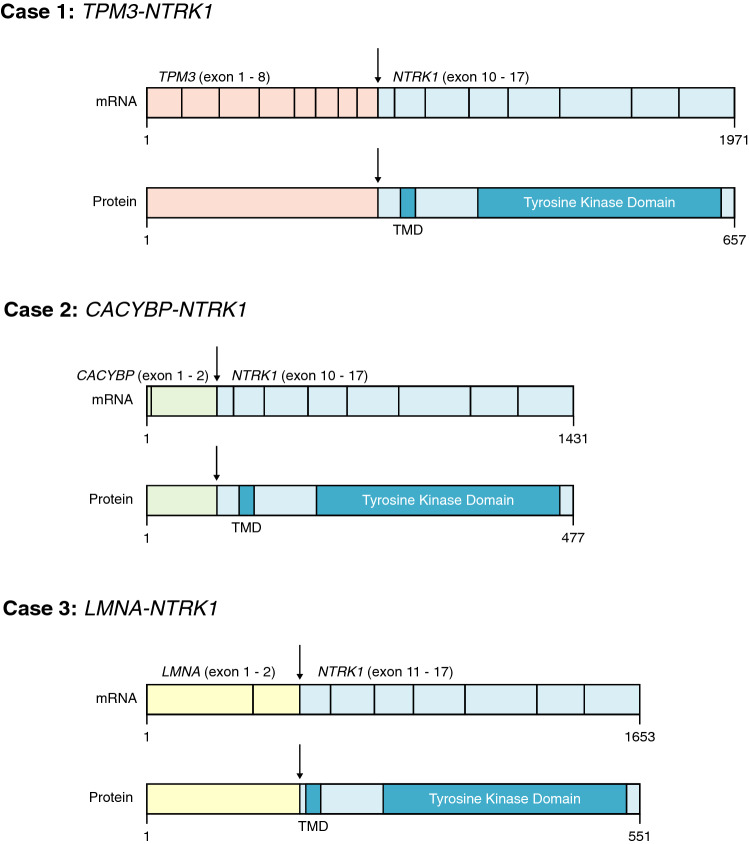

Three out of 21 (14%) cases of our cohort harbored a NTRK1 fusion gene. The partner genes were TPM3, LMNA and CACYBP (Fig. 2). TPM3::NTRK1 and LMNA::NTRK1 are common driver fusion genes in NTRK-related spindle cell neoplasms [1], whereas CACYBP::NTRK1 has not been reported in the literature so far. One could argue that these three tumors represent classical NTRK-rearranged spindle cell neoplasms unrelated to the NF1. Nonetheless, two tumors originated in a plexiform neurofibroma and harbored biallelic NF1 mutations. The third case showed clinical signs of NF1, but failed to show two hits, possibly due to technical limitations (Tables 1, 2).

Fig. 2.

Detected fusion transcripts and the resulting fusion proteins in the three NF1-related MPNSTs with a NTRK1 rearrangement. Functional regions and domains are annotated. Transmembrane Domain (TMD)

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of NF1 patients with MPNSTs harboring NTRK rearrangements

| Case | Age | Location | Primary diagnosis | Metastases | Neo-adjuvant Therapy | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16 | Knee | MPNST ex plexiform neurofibroma | Yes (lung) | Trk-i | Aw/oD (18 months) |

| 2 | 29 | Sciatic nerve | MPNST ex plexiform neurofibroma | No | Radiotherapy | Aw/oD (8 years) |

| 3 | 34 | Quadriceps muscle | MPNST without signs of preexisting neurofibroma | No | None | Aw/oD (29 years) |

Aw/oD alive without disease, Trk-i Trk-inhibitor

Table 2.

Molecular characteristics of MPNSTs with NTRK1 rearrangements

| Case | Technique for fusion transcript analysis | Fusion gene | Other molecular alterations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (first biopsy) | RNA-seq |

TPM3::NTRK1 exon 7 – exon 10 |

Focal deletion 17p; second somatic mutation NF1 c.7062_7063ins43 p.(Ser2355Valfs*7); 75% (WES) |

| 2 | RNA-seq |

CACYBP::NTRK1 exon 2 – exon 10 |

homozygous loss of NF1 (CNV) |

| 3 | Archer |

LMNA::NTRK1 exon 2 – exon 11 |

Loss of one NF1 allele; other allele not interpretable (CNV) |

By WGS, FISH and/or immunohistochemistry, the NTRK1 rearrangement presented as a subclonal molecular event in all three cases, further influencing MAPK signaling due to autoactivation of the corresponding transmembrane tyrosine kinase. NTRK genes, encoding for the neurotrophin family of growth factor receptors, have a crucial role in cell survival and proliferation, especially of neural tissue. Hence, it is not surprising that alterations in these genes can result in tumor development of MPNSTs [2].

Detection of NTRK chimeric fusion transcripts in NF1-associated MPNSTs might be of clinical importance as they may allow for targeted treatment with Trk-i as shown in one of our cases (Fig. 1a). While neurofibromin acts downstream of Trk, the sole blockade of the latter might be insufficient to fully abrogate MAPK signaling. In fact, a recent study showed that combined targeting of Trk and MEK, further downstream in the MAPK signaling pathway, in tumors harboring a NTRK fusion gene in combination with another activating alteration in the MAPK signaling pathway (i.e., activating KRAS and BRAF mutations) is paramount to prevent progression under Trk-i therapy and increase efficacy [3]. Whereas single agent treatment efficacy of MEK-i in NF1-related MPNSTs is questionable [4], the combination of a Trk-i and a MEK-i warrants further investigation.

In accordance with the intrinsic resistance against monotherapeutic Trk-i, the tumor of our treated case, initially showing good response, progressed during continuation of Trk-i treatment. A typical “escape” mutation in the kinase domain could not be detected by WES [2, 6]. Although the underlying resistance mechanism remains unclear so far, one could hypothesize that, besides another undetected mutation, quiescent cancer stem cells with specific genetic alterations are responsible for sustaining tumor growth [9].

Our study for the first time describes NF1-related MPNSTs harboring subclonal NTRK rearrangements with primarily good response to Trk-i treatment which could be an (additional) therapeutic agent.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marja van Blokland and Petra van der Weide for their very valuable help with this project.

Author contributions

LHI, MM, LKE, UFL conceptualized and made the original draft of the manuscript; LKE, RM, JHK, IvB performed the formal analyses; LHI, MM conducted the visualization of the data; all authors reviewed, edited and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Code of Conduct for Medical Research of the Federation of the Dutch Medical Scientific Societies. In addition, the material acquisition was performed in accordance with local bio banking initiative.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

L. S. Hiemcke-Jiwa and M. T. Meister: shared first authorship.

U. Flucke and L. A. Kester: shared senior authorship.

References

- 1.Antonescu CR. Emerging soft tissue tumors with kinase fusions: an overview of the recent literature with an emphasis on diagnostic criteria. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2020;59:437–444. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cocco E, Scaltriti M, Drilon A. NTRK fusion-positive cancers and TRK inhibitor therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:731–747. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0113-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cocco E, Schram AM, Kulick A, Misale S, Won HH, Yaeger R, et al. Resistance to TRK inhibition mediated by convergent MAPK pathway activation. Nat Med. 2019;25:1422–1427. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0542-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Blank PMK, Gross AM, Akshintala S, Blakeley JO, Bollag G, Cannon A et al (2022) MEK inhibitors for neurofibromatosis type 1 manifestations: clinical evidence and consensus. Neuro Oncol. 10.1093/neuonc/noac165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Dupain C, Harttrampf AC, Boursin Y, Lebeurrier M, Rondof W, Robert-Siegwald G, et al. Discovery of new fusion transcripts in a cohort of pediatric solid cancers at relapse and relevance for personalized medicine. Mol Ther. 2019;27:200–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemming ML, Nathenson MJ, Lin JR, Mei S, Du Z, Malik K, et al. Response and mechanisms of resistance to larotrectinib and selitrectinib in metastatic undifferentiated sarcoma harboring oncogenic fusion of NTRK1. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020;4:79–90. doi: 10.1200/PO.19.00287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longo JF, Brosius SN, Znoyko I, Alers VA, Jenkins DP, Wilson RC, et al. Establishment and genomic characterization of a sporadic malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor cell line. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5690. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pemov A, Li H, Presley W, Wallace MR, Miller DT. Genetics of human malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Neurooncol Adv. 2020;2:i50–i61. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdz049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somatilaka BN, Sadek A, McKay RM, Le LQ. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: models, biology, and translation. Oncogene. 2022;41:2405–2421. doi: 10.1038/s41388-022-02290-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uusitalo E, Rantanen M, Kallionpää RA, Pöyhönen M, Leppävirta J, Ylä-Outinen H, et al. Distinctive cancer associations in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1978–1986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.