Abstract

Artemisia capillaris and Artemisia iwayomogi are well-known herbal medicines which are used as hepatotherapeutic drugs. These two herbal species can be confused with each other, owing to their morphological similarity and similar Korean common names of “Injinho” and “Haninjin,” respectively. Molecular markers to distinguish between the two plants were developed. Six primer sets were designed and verified, and their efficiencies were found to range from 90.28 to 98.29%. The developed primer sets had significant correlation coefficient values between the cycle threshold values and the logarithm of DNA concentration for their target species (R2 > 0.98), with slopes ranged from − 3.3637 to − 3.5793. The specificity of the quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was confirmed with 14 other species. Additionally, 16 commercial medicinal herbs and 40 blind samples were tested to evaluate their reliability. Collectively, the findings indicate that developed qPCR-based target-specific primer sets have potential applicability toward protection of consumers’ rights.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10068-022-01166-0.

Keywords: Artemisia capillaris, Artemisia iwayomogi, Medical herb, Species identification, SYBR-GREEN real-time PCR

Introduction

Traditional herbal medicines have been used to prevent various diseases. The use of herbal medicinal products and supplements by the global population has increased. In particular, approximately four billion people living in developing countries seem to depend on herbal medicines for healthcare (Ekor et al., 2014). The size of the traditional herbal medicine market in Europe was estimated at US$5.18 billion in 2016 (Research and Markets, 2018). In 2016, the American Botanical Council reported that US$7.45 billion was spent on traditional herbs in the United States (Smith et al., 2016). The global herbal medicine market is constantly expanding and is expected to surpass approximately US$129 billion by 2023 (Market Research Future, 2018)

The genus Artemisia consists of more than 500 diverse species and belongs to the Asteraceae family. Artemisia has diverse secondary metabolites and active ingredients, thereby exhibiting a vast range of bioactivities (Nigam et al., 2019). In this genus, A. capillaris is called “Injinho” and A. iwayomogi is termed as “Haninjin” in Korea. (Wang et al., 2012). These are registered as Korean herbal medicines, and their origins are A. capillaris Thunb. and A. iwayomogi Kitamura, respectively (The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, 2015). According to the discrimination of A. capillaris in Korea (The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, 2017a, 2017b), it is listed in the Korean Herbal Pharmacopoeia (Herbal Medicine) and Japanese Pharmacopoeia (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, 2011). However, in the Taiwan Herbal Pharmacopoeia, the People's Republic of China, and Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards, A. scoparia Waldst. et Kit. or A. capillaris is listed as its origin (China Pharmacopoeia, 2015; Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy, 2013; The Government of the Hong Kong special Administrative Region, 2005). According to the discrimination of A. iwayomogi (The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, 2017a, 2017b), herbal medicines are not listed in the Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China, Japanese Pharmacopoeia, Taiwan Herbal Pharmacopoeia, Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standards, Vietnamese Pharmacopoeia, or Pharmacopoeia of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

A. capillaris Thunb. and A. iwayomogi have traditionally been used as herbal medicines in Korea and China. Their derivatives show cholesteric (Okuno et al., 1981), anti-inflammatory (Jang et al., 2005; Shin et al., 2006), cytoprotective (Hong et al., 2007), antioxidant (Seo and Yun, 2008), antibacterial (Seo et al., 2010), and hepatoprotective effects (Choi et al., 2011). A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi have been used to treat liver disorders because they have the same medicinal name, “InJin,” in oriental medicine clinics, despite the difference in their taxonomic position (Wang et al., 2012). Furthermore, owing to their morphological similarities, A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi are often undistinguished in the herbal medicine market (Seoul Metropolitan Government Research Institute of Public Health and Environment, 2017). Thus, a species identification method that can clearly distinguish between the two medicinal species is needed for improved pharmaceutical quality control and consumer safety.

Counterfeit ingredients in complex food products have been detected using various techniques, including DNA-based analysis (Hong et al., 2017). qPCR can detect target ingredients in complex food products, including functional foods, with high accuracy (Kane and Hellberg, 2016; An et al., 2018). Additionally, qPCR has been extensively used to determine species in diverse industries, including raw meat or processed meat mixtures. (Cammà et al., 2012), animal products (Fumiere et al., 2006), animal feed (Loncarevic et al., 2008), fish and seafood (Naaum et al., 2016), and herbal formulations (Kumar et al., 2020).

Conventional PCR-based markers, such as random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (Pyo and Choi, 1996), multiplex PCR (Lee et al., 2008), and sequence characterization amplification region markers (Lee et al., 2006) have been developed to detect Artemisia spp. at the molecular level. However, the disadvantages of these methods, such as end-point detection, low sensitivity, and high time requirements, can be overcome with the development of qPCR-based markers that have advantages, such as high sensitivity and real-time monitoring.

In the present study, we developed a qPCR-based approach to distinguish between A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi, which can be confused for one another due to the lack of clear identification of their herbal origins, owing to their morphological similarity and identical Korean herbal medicine name “InJin”. We also tested 14 other species used in commercial products and 40 blind samples, using species-specific markers to demonstrate the reliability of the process.

Materials and methods

Plant and sample preparation

Capillaris wormwood (A. capillaris) was supplied by an accredited national institution. (Food and Drug Safety Evaluation, Republic of Korea). Wormwood gmelin (A. iwayomogi) was provided by Hantaek Botanical Garden (Yongin, Korea). The plants were planted in pots comprising horticultural soil (Seoul Bio, Chung Buk, Korea) and then cultivated in greenhouses at a controlled temperature (24 °C). Fresh leaves from both the plants were washed with distilled water and lyophilized. The samples were then pulverized using a mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen and used as a powder. All commercial products were stored in sealed containers at room temperature (20–21 °C) and were powdered using a blender.

Specificity test

To examine the cross-reactivity of the designed primer sets, a specificity test was performed using 14 plant species in addition to A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi. The 14 dry samples were stored in a shade at room temperature (20–21 °C) utilizing sealed products acquired from the local market. As a positive control, the primer pair 18S rRNA was used, and the PCR product was amplified using 20 cycles prior to qPCR.

Reference binary mixtures of A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi

Quantitative reference binary mixtures were produced in batches of four powder binary mixtures of increasing amounts (0.1–100% w/w), as described previously (Kim et al., 2021). Therefore, A. capillaris powder was added to A. iwayomogi powder and mixed to formulate four different binary mixtures (2 g each), and vice versa. Additionally, since impurities of concentrations less than 0.1% are generally not considered illegal for economic reasons, the real-time PCR cycle threshold (Ct) for target species in all binary mixtures was applied at a cut-off value of 0.1% to distinguish between pure and adulterated products (Oh and Jang, 2020). The applicability of DNA markers to processed products was evaluated as described by Oh et al. (2022).

Blind samples

Forty blind test samples were obtained from the National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation of the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (Cheongju, Korea). The samples comprised randomly selected percentages of A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi ground powders. The A. capillaris powder or A. iwayomogi powder was used to prepare 0–10% (w/w) concentration samples (total 150 mg).

Genomic DNA (gDNA) extraction

To evaluate PCR primer set efficiency, gDNA, which was used to generate standard curves, was extracted from the leaves of A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi using the DNeasy Plant Pro Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total gDNA was isolated from binary mixture samples (2 g each) using a modified large-scale CTAB-based (1% [w/v] cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, 100 mmol/L Tris, 700 mmol/L EDTA, 1% β-mercaptoethanol) gDNA isolation method and purified employing the Wizard DNA Clean-up system (Promega, Madison, USA) to obtain high-quality gDNA (Sasikumar et al., 2004). The gDNA was used to plot a standard curve for the reference binary mixture. gDNA from commercial A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi herbal medicine products was extracted utilizing the DNeasy Plant Pro Kit (Qiagen). The purity was estimated using a SPECTROstar Nano reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) to verify that it lies between 1.7 and 2.

Specific primer design for target species

To develop species-specific primer sets, the reference sequences of the chloroplast genes accD, rpoB, matK, and ycf1 of two species [A. capillaris (NC_031400.1) and A. iwayomogi (NC_031399.1)] and the nuclear DNA sequences of the capillary wormwood species of A. capillaris (KT965668.1) were obtained from the NCBI nucleotide database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Multiple sequence alignments were performed using ClustalW2 (EMBL-EBI, Hinxton, Cambridgeshire, UK) and BioEdit v.7.2 (Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were affirmed in A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi. Therefore, we designed a set of species-specific primers in the variable region utilizing Beacon Designer (PRIMER Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and they were synthesized by a commercial firm (Macrogen, Seoul, South Korea).

Cloning and sequencing of PCR amplicons

Conventional PCR was conducted in a C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, California, USA) with 10 pmol primer mixture and 10 ng DNA using TaKaRa Ex Taq™ DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Bio Company, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan). The PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 53–61 °C (according to primer set Tm) for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min. The primer extension step was performed for 5 min at 72 °C in the final cycle. Cloning and sequencing of the PCR products (AC_ITS, AC_accD, AC_rpoB, AI_matK, AI_ycf1, and AI_rpoB) were performed as previously described (Oh and Jang, 2020).

Optimization of qPCR

qPCR with Gotaq® qPCR Systems (Promega) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The qPCR mixture contained 2× Gotaq Master Mix (10 µL), 10 pmol of each primer (0.5 µL), 10 ng/µL gDNA (1 µL), and CXR reference dye (0.2 µL), adjusted to a final volume of 20 µL with distilled water. qPCR amplification was performed using the Quant Studio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the following cycling program: 95 °C for 2 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 58–62 °C (according to the primer set Tm) for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. qPCR was performed in triplicate.

qPCR standard curve construction and data analysis

qPCR analysis was performed as described by Oh et al. (2022). At the threshold level of log-based fluorescence, the number of cycles was defined as the cycle threshold (Ct) number, which was observed in qPCR experiments (Yuan et al., 2006). The default parameters were used to determine the correlation between the Ct standard curve and the diluted DNA. The standard curve was calculated as Y = − mx + b, the slope of the standard curve was "m" in the equation, and "b" represents the y-intercept. The calculation for estimating the efficiency (E) of the real-time PCR assay was E = (10–1/slope) and the percentage of the efficiency was evaluated as (E – 1) × 100%. (ENGL, 2015; Lo and Shaw, 2018). Based on previous reports (Bustin et al., 2009), two criteria were used to define an acceptable qPCR accuracy analysis: (1) 110% to 90% amplification efficiency corresponding to a slope between − 3.10 and − 3.58; (2) Linear dynamic range with R2-value (correlation coefficient) > 0.98, measured over four log10 concentrations. The accuracy and reproducibility of qPCR primer pairs were evaluated in two different laboratories, as described by Oh et al. (2022).

Results and discussion

Development of DNA markers based on variation regions

To distinguish between A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi, species-specific primer pairs were designed to amplify the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions and chloroplast genes, as described by Oh et al. (2022). The ITS region exists on the rRNA gene. Furthermore, the ribosome gene, which is essential for protein synthesis, is an indispensable and well-conserved gene in present organisms. Accordingly, ITS section analysis is possible in almost all taxa, and primers for sequencing can be well established or used in a wide range of organisms (Baldwin et al., 1995). Other studies have used chloroplast genes (e.g., matK, rpoB, rbcL, and rpoC1) for species identification (CBOL Plant Working, et al., 2009). Sequence alignment was performed between A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi to design a set of qPCR primers based on variable sequences between the two species. We identified a variety of SNPs within the nuclear DNA and chloroplast genomes of both species (Supplementary Fig. 1). The processing of various food products reduces the quality of DNA contained in the products, as the DNA gets degraded during drying, heating, and blending processes (Lo and Shaw, 2018). As low-quality DNA decreases the efficiency of qPCR, especially when the target sequence is extensive, we designed primer pairs to amplify short sequences of 100–374 bp.

Evaluation and validation of the designed primer sets

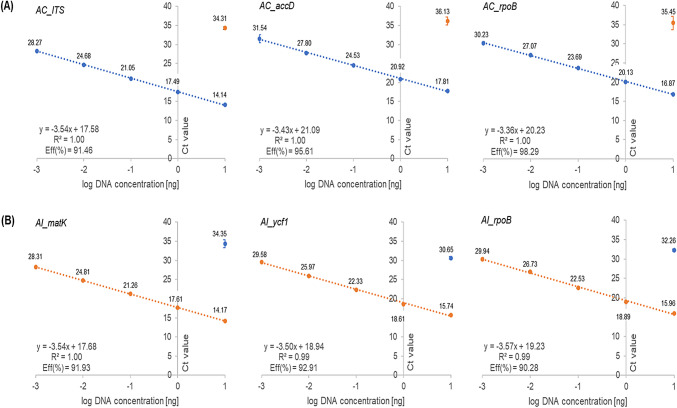

The sensitivity of six primer sets (AC_ITS, AC_accD, AC_rpoB, AI_matK, AI_ycf1, and AI_rpoB) was evaluated by investigating the standard curve using continuously diluted (ten-fold) DNA isolated from leaf samples of the target species (10–0.001 ng/µL) and performing regression analysis. The R2-value or correlation coefficient of the six primer sets were higher than 0.98, the slopes ranged from − 3.36 to − 3.57, and the efficiency based on the slope ranged from 90.28 to 98.29% for each target species (Fig. 1). All values satisfied the ENGL (European Network of GMO Laboratories) guidelines. In addition, inter-laboratory experiments in two independent laboratories were performed to validate the adaptability of the six primer sets used with different qPCR machines. As a result, the PCR efficiency was 90.94% to 103.40%, and the R2-value was greater than 0.98 (Supplementary Table 1). Efficiency tests of the designed primers depicted that the primer sets were suitable for the detection of target species (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Standard curves were constructed based on the efficiency and correlation coefficient (R2) using ten-fold serially diluted genomic DNA (10 ng/µL to 1 pg/µL) of A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi and species-specific primer sets. The x-axis represents the logarithm of the DNA concentration (ng), and the y-axis represents average cycle threshold (Ct) value ± standard deviation (SD). Blue dot, A. capillaris; orange dot, A. iwayomogi. (A) A. capillaris-targeting primer sets (AC_ITS, AC_accD, and AC_rpoB), and (B) A. iwayomogi-targeting primer sets (AI_matK, AI_ycf1, and AI rpoB). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed in triplicate (n = 3)

Table 1.

The designed primer sets of real-time PCR assay for targeting the target species

| Target species | Target gene | Primer | Length (bp) | Sequence (5ʹ → 3 ʹ ) | Size (bp) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All plants | 18s rRNA | 18s rRNA_F | 25 | TCTGCCCTATCAACTTTCGATGGTA | 137 | 58 |

| 18s rRNA_R | 25 | AATTTGCGCGCCTGCTGCCTTCCTT | ||||

| Artemisia capillaris | ITS | AC_ITS_F | 17 | AGGCTCGTTTCGTGTAG | 257 | 60 |

| AC_ITS_R | 18 | CCTGACGGAGAATTTGTG | ||||

| accD | AC_accD_F | 20 | GTAGTGAAAGTGGAAATAGC | 100 | 58 | |

| AC_accD_R | 23 | CTGTATTTTTGATTTACATCCAC | ||||

| rpoB | AC_rpoB_F | 18 | GGAACTGGATTGGAAGGA | 112 | 59 | |

| AC_rpoB_R | 23 | CATTACCTGATAAAAGGATCTTG | ||||

| Artemisia iwayomogi | matK | AI_matK_F | 22 | TGATTTAGCCAGTGATCCAATC | 374 | 62 |

| AI_matK_R | 20 | TTGCAGAAGTCTTTCTCAGG | ||||

| ycf1 | AI_ycf1_F | 21 | CTTTTGCCTGTGAATAATCTC | 251 | 59 | |

| AI_ycf1_R | 25 | CTACAAAGTCGAAATAAGAAATTTG | ||||

| rpoB | AI_rpoB_F | 18 | GGAACTGGATTGGAAGGC | 113 | 61.5 | |

| AI_rpoB_R | 24 | CCATTACCTGATAAAAGGATCTTC |

Consequently, we examined 14 other species in addition to A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi to test the specificity of the six qPCR primer sets designed for this study (Table 2). Five primer sets, except AI_matK, did not produce any amplicons from the other non-targeted 14 species before amplification by 40 cycles. However, using AI_matK, PCR products were amplified from the three species belonging to the Compositae family at Ct values greater than the cutoff Ct value and before 40 cycles. Taken together, these results indicated that the developed DNA markers were optimized to detect the intended target species without any false-positive amplifications involving the other 14 species.

Table 2.

The result of the species specificity test using real-time PCR primer sets

| NO | Family | Species | Artemisia capillaris | Artemisia iwayomogi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | accD | rpoB | matK | rpoB | ycf1 | |||

| Cut-off cycles | 26.14 | 28.61 | 28.35 | 30.46 | 27.08 | 28.51 | ||

| 1 | Compositae | Artemisia capillaris | ++a | ++ | ++ | − | − | − |

| 2 | Artemisia iwayomogi | −b | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| 3 | Dendranthema indicum | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 4 | Cirsium japonicum | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 5 | Xanthium strumarium | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 6 | Taraxacum platycarpum | − | − | − | +c | − | − | |

| 7 | Carthamus tinctorius | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 8 | Dendranthema zawadskii | − | − | − | + | − | − | |

| 9 | Aster tataricus | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 10 | Artemisia annua | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 11 | Kalimeris yomena | − | − | − | + | − | − | |

| 12 | Ambrosia artemisiifolia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 13 | Liliaceae | Veratrum maackii | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 14 | Hemerocallis fulva | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 15 | Zingiberaceae | Curcuma longa | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 16 | Graminae | Zea mays | − | − | − | − | − | − |

a++ Means that was amplified before cut-off Ct cycles

b− Means that was not amplified before 40 cycles

c+ Means that was amplified between more than cut-off Ct cycles and less than 40 cycles

Application of the developed qPCR assay for dried, heated, and autoclaved samples

In general, commercial products of A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi are subjected to various processes, such as drying, heating, and autoclaving. Such food-processing conditions can cause serious DNA degradation in medicinal herb samples. For example, heat treatment causes severe DNA fragmentation; therefore, conventional PCR-based marker assays are inefficient and inappropriate for authenticating food products (Hwang et al., 2015). Hence, we examined the efficiency, R2-value, and slope of the designed qPCR assay using processed leaf reference binary mixtures to confirm its applicability in commercial herbal medicines. We constructed six standard curves for a ten-fold DNA dilution series of A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi, using a qPCR primer set (Table 3). All slopes ranged from − 3.36 to − 3.57, and the six R2-value were > 0.98 for each designed primer set. The reaction efficiency values ranged from 90.28 to 98.29% for each target species. gDNA was extracted from dried, heated, and autoclaved leaf binary mixtures (0.1–100% w/w), diluted to 10 ng/μL, and adopted for qPCR evaluation. Ct values were acquired for each sample subjected to the three types of food processing (Supplementary Table 2). Dried and heated leaf binary mixtures estimated comparably low Ct values; however, for the autoclaved samples, higher Ct values were observed than those of the dried and heated samples. These results indicate that the autoclaved leaves had more severe DNA degradation than dried and heated leaves, suggesting that different Ct values should be applied to determine adulteration according to the product processing procedures. The 18 designed qPCR primer sets had slopes ranging from − 3.12 to − 3.57, R2-value > 0.98, and efficiency values ranging from 90.28 to 108.90 for the processed leaf binary mixtures (Table 3). In general, a level of adulteration < 0.1% is acceptable in food products, and consequently, a Ct value of 0.1% of the target species in all binary mixtures should be used to establish the cut-off cycle number to discern genuine products from adulterated products (Oh et al., 2022).

Table 3.

Evaluation of slope, R2, and efficiency obtained by real-time PCR system

| DNA standard curve | Dry-treated binary mixture standard curve | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target species | Primer | Y (Slope) | R2 | Efficiency (%) | Target species | Primer | Y (Slope) | R2 | Efficiency (%) | |

| A. capillaris | AC_ITS | -3.54 | 1 | 91.46 | A. capillaris | AC_ITS | -3.45 | 0.98 | 94.89 | |

| AC_accD | -3.43 | 1 | 95.61 | AC_accD | -3.25 | 0.98 | 103.02 | |||

| AC_rpoB | -3.36 | 1 | 98.29 | AC_rpoB | -3.22 | 0.98 | 104.37 | |||

| A. iwayomogi | AI_matK | -3.54 | 1 | 91.93 | A. iwayomogi | AI_matK | -3.16 | 0.99 | 107.11 | |

| AI_ycf1 | -3.5 | 0.99 | 92.91 | AI_ycf1 | -3.21 | 0.99 | 104.58 | |||

| AI_rpoB | -3.57 | 0.99 | 90.28 | AI_rpoB | -3.17 | 1 | 106.51 | |||

| Heat-treated binary mixture standard curve | Autoclave-treated binary mixture standard curve | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target species | Primer | Y (Slope) | R2 | Efficiency (%) | Target species | Primer | Y (Slope) | R2 | Efficiency (%) | |

| A. capillaris | AC_ITS | -3.21 | 0.99 | 104.75 | A. capillaris | AC_ITS | -3.29 | 0.99 | 101.39 | |

| AC_accD | -3.29 | 0.99 | 101.45 | AC_accD | -3.21 | 0.99 | 106.61 | |||

| AC_rpoB | -3.31 | 0.99 | 100.27 | AC_rpoB | -3.18 | 0.99 | 106.19 | |||

| A. iwayomogi | AI_matK | -3.17 | 0.99 | 106.76 | A. iwayomogi | AI_matK | -3.15 | 0.99 | 107.74 | |

| AI_ycf1 | -3.13 | 0.99 | 108.3 | AI_ycf1 | -3.14 | 0.99 | 108.15 | |||

| AI_rpoB | -3.14 | 0.99 | 108.15 | AI_rpoB | -3.12 | 0.99 | 108.9 | |||

Set threshold cycle (Ct) values obtained from three condition (dried, heated, and autoclaved) using the designed primer sets with reference binary mixtures

qPCR reliability validation using blind samples

For reliability testing, we performed blinded tests with 20 samples of A. iwayomogi powder mixed with an unknown amount of A. capillaris powder (Table 4A) and 20 samples of A. capillaris powder mixed with an unknown amount of A. iwayomogi powder (Table 4B). Forty unknown powder samples of A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi were randomly mixed at different concentrations by other independent research groups. Amplification of 18S rRNA was conducted as a positive control, and the amplified PCR products had low Ct values (12.81–13.76 cycles) (Table 4). Subsequently, we evaluated the presence of A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi powders in the samples based on the cut-off Ct values of the devised primer sets. (0.1% A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi in binary mixtures, respectively). Three samples (samples 9, 14, and 19), in which the Ct value of the A. capillaris primer sets exceeded the cut-off Ct values, were identified. This indicates that the sample did not contain A. capillaris powder within the A. iwayomogi powder. The remaining 17 samples had Ct values lower than their cut-off values, indicating that these samples were blended with the A. capillaris powder. Another three samples (samples 24, 37, and 38), in which the Ct value of the A. iwayomogi primer sets exceeded the cut-off Ct values, were identified. This denotes that the sample did not contain A. iwayomogi powder within the A. capillaris powder. Moreover, the other 17 samples exhibited lower Ct than the cut-off values, indicating that these samples comprised A. iwayomogi powder. Overall, qPCR showed identical results for the 40 blind samples (Table 4), supporting the fact that the developed qPCR analysis can be used commercially to identify the indiscriminate use of the two morphologically similar medicinal herbs.

Table 4.

Results of the blind mixture (total mass of 150 mg) test for evaluating the reliability of the developed primer

| A | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primer sets | A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi blind test | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sample number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 18 s rRNA primer | 13.76 ± 0.146 | 13.641 ± 0.317 | 13.679 ± 0.280 | 13.878 ± 0.144 | 13.582 ± 0.190 | 13.041 ± 0.235 | 13.531 ± 0.429 | 13.225 ± 0.213 | 12.99 ± 0.000 | 13.102 ± 0.094 | 13.621 ± 0.125 | 13.507 ± 0.225 | 13.438 ± 0.285 | 13.667 ± 0.142 | 13.458 ± 0.148 | 13.618 ± 0.122 | 13.671 ± 0.115 | 13.438 ± 0.113 | 13.087 ± 0.123 | 13.099 ± 0.106 |

| A. capillaris | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ITS 26.14 cyclesa | 19.785 ± 0.109 | 21.841 ± 0.093 | 22.146 ± 0.261 | 22.216 ± 0.212 | 19.876 ± 0.109 | 21.87 ± 0.166 | 22.34 ± 0.173 | 21.277 ± 0.127 | 33.232 ± 1.478 | 20.889 ± 0.081 | 22.015 ± 0.070 | 24.702 ± 0.162 | 21.296 ± 0.052 | 32.707 ± 0.435 | 21.858 ± 0.154 | 21.055 ± 0.140 | 22.166 ± 0.191 | 23.188 ± 0.254 | 31.704 ± 0.354 | 23.459 ± 0.238 |

| accD 28.61 cycles | 22.924 ± 0.063 | 25.009 ± 0.035 | 25.859 ± 0.169 | 25.861 ± 0.111 | 23.466 ± 0.156 | 25.165 ± 0.268 | 25.72 ± 0.008 | 24.729 ± 0.240 | 34.872 ± 0.820 | 23.964 ± 0.142 | 25.521 ± 0.153 | 27.919 ± 0.068 | 24.766 ± 0.064 | 34.71 ± 0.301 | 24.795 ± 0.209 | 24.383 ± 0.096 | 25.716 ± 0.115 | 26.131 ± 0.209 | 33.891 ± 0.960 | 26.397 ± 0.085 |

| rpoB 28.35 cycles | 23.153 ± 0.091 | 25.167 ± 0.029 | 25.886 ± 0.066 | 25.931 ± 0.062 | 23.721 ± 0.026 | 25.182 ± 0.130 | 25.8 ± 0.002 | 24.919 ± 0.048 | 35.344 ND | 24.348 ± 0.185 | 25.8 ± 0.045 | 28.107 ± 0.068 | 24.832 ± 0.028 | 37.466 ± 2.853 | 24.951 ± 0.193 | 23.909 ± 0.235 | 25.879 ± 0.130 | 26.076 ± 0.160 | 33.212 ± 0.762 | 26.556 ± 0.167 |

| A. iwayomogi | ||||||||||||||||||||

| matK 30.46 cycles | 21.23 ± 0.022 | 21.144 ± 0.085 | 21.023 ± 0.022 | 21.363 ± 0.099 | 20.887 ± 0.150 | 20.731 ± 0.084 | 20.91 ± 0.051 | 20.565 ± 0.093 | 21.095 ± 0.067 | 20.558 ± 0.089 | 21.018 ± 0.032 | 20.985 ± 0.021 | 20.816 ± 0.139 | 20.985 ± 0.035 | 20.952 ± 0.046 | 20.946 ± 0.101 | 20.891 ± 0.128 | 20.812 ± 0.094 | 20.659 ± 0.021 | 20.589 ± 0.093 |

| ycf1 27.08 cycles | 23.084 ± 0.119 | 23.108 ± 0.037 | 23.334 ± 0.194 | 23.239 ± 0.177 | 23.269 ± 0.158 | 23.019 ± 0.290 | 22.979 ± 0.192 | 22.919 ± 0.079 | 23.196 ± 0.183 | 22.895 ± 0.149 | 23.137 ± 0.121 | 23.07 ± 0.111 | 23.16 ± 0.252 | 23.286 ± 0.201 | 23.137 ± 0.355 | 23.01 ± 0.147 | 22.883 ± 0.116 | 22.83 ± 0.184 | 22.793 ± 0.154 | 22.795 ± 0.193 |

| rpoB 28.51 cycles | 22.135 ± 0.105 | 22.211 ± 0.039 | 22.296 ± 0.058 | 21.942 ± 0.068 | 21.875 ± 0.131 | 21.727 ± 0.007 | 21.969 ± 0.024 | 21.841 ± 0.001 | 21.993 ± 0.012 | 21.783 ± 0.074 | 22.129 ± 0.157 | 22.026 ± 0.093 | 22.165 ± 0.052 | 22.082 ± 0.033 | 21.98 ± 0.003 | 21.877 ± 0.062 | 21.893 ± 0.112 | 21.732 ± 0.015 | 21.733 ± 0.087 | 21.704 ± 0.064 |

| Test results | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| B | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primer sets | A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi blind test | |||||||||||||||||||

| Sample number | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 |

| 18 s rRNA primer | 13.392 ± 0.091 | 13.18 ± 0.112 | 13.1 ± 0.077 | 13.094 ± 0.188 | 13.176 ± 0.096 | 12.915 ± 0.079 | 13.112 ± 0.064 | 12.904 ± 0.012 | 12.847 ± 0.115 | 13.039 ± 0.165 | 13.19 ± 0.101 | 13.37 ± 0.100 | 13.059 ± 0.140 | 13.343 ± 0.091 | 13.054 ± 0.053 | 13.22 ± 0.128 | 13.073 ± 0.205 | 13.005 ± 0.100 | 13.041 ± 0.171 | 12.81 ± 0.106 |

| A. capillaris | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ITS 26.14 cyclesa | 15.604 ± 0.377 | 14.895 ± 0.095 | 14.88 ± 0.142 | 15.596 ± 0.397 | 15.26 ± 0.049 | 14.856 ± 0.117 | 15.126 ± 0.091 | 14.883 ± 0.119 | 15.214 ± 0.094 | 14.929 ± 0.039 | 14.797 ± 0.114 | 15.582 ± 0.114 | 14.805 ± 0.093 | 15.287 ± 0.203 | 14.973 ± 0.152 | 15.194 ± 0.101 | 14.921 ± 0.146 | 15.306 ± 0.048 | 15.477 ± 0.006 | 14.98 ± 0.072 |

| accD 28.61 cycles | 18.895 ± 0.141 | 18.473 ± 0.057 | 18.402 ± 0.133 | 18.294 ± 0.081 | 18.371 ± 0.053 | 18.259 ± 0.034 | 18.287 ± 0.072 | 18.378 ± 0.037 | 18.175 ± 0.075 | 18.172 ± 0.013 | 18.206 ± 0.248 | 18.362 ± 0.111 | 18.223 ± 0.050 | 18.356 ± 0.108 | 18.188 ± 0.188 | 18.229 ± 0.035 | 18.159 ± 0.051 | 17.993 ± 0.082 | 18.106 ± 0.008 | 17.899 ± 0.039 |

| rpoB 28.35 cycles | 18.578 ± 0.050 | 17.994 ± 0.048 | 18.079 ± 0.034 | 17.997 ± 0.058 | 18.03 ± 0.027 | 18.026 ± 0.136 | 17.94 ± 0.026 | 17.955 ± 0.014 | 17.955 ± 0.009 | 17.974 ± 0.036 | 18.058 ± 0.019 | 18.26 ± 0.107 | 18.074 ± 0.030 | 18.192 ± 0.034 | 18.03 ± 0.050 | 18.09 ± 0.024 | 18.032 ± 0.052 | 17.949 ± 0.063 | 18.008 ± 0.112 | 17.888 ± 0.030 |

| A. iwayomogi | ||||||||||||||||||||

| matK 30.46 cycles | 22.863 ± 0.001 | 23.514 ± 0.061 | 24.936 ± 0.042 | 34.519 ± 1.008 | 23.772 ± 0.104 | 23.006 ± 0.151 | 26.165 ± 0.000 | 24.204 ± 0.083 | 26.98 ± 0.119 | 22.925 ± 0.011 | 22.945 ± 0.184 | 24.096 ± 0.031 | 24.448 ± 0.021 | 24.834 ± 0.085 | 26.111 ± 0.196 | 24.728 ± 0.171 | 34.742 ± 1.218 | 34.385 ± 0.581 | 24.827 ± 0.048 | 26.191 ± 0.261 |

| ycf1 27.08 cycles | 24.776 ± 0.101 | 25.059 ± 0.051 | 26.09 ± 0.190 | 34.323 ± 0.190 | 25.74 ± 0.108 | 25.174 ± 0.153 | 27.614 ± 0.198 | 25.747 ± 0.110 | 28.195 ± 0.114 | 24.513 ± 0.288 | 26.148 ± 0.176 | 25.848 ± 0.103 | 26.122 ± 0.185 | 26.075 ± 0.122 | 27.339 ± 0.183 | 26.605 ± 0.172 | 35.054 ± 0.094 | 33.2 ± 0.186 | 26.237 ± 0.150 | 28.222 ± 0.179 |

| rpoB 28.51 cycles | 24.237 ± 0.134 | 24.571 ± 0.080 | 25.817 ± 0.031 | 31.722 ± 0.020 | 24.955 ± 0.135 | 24.499 ± 0.117 | 26.966 ± 0.013 | 25.17 ± 0.194 | 27.929 ± 0.033 | 23.935 ± 0.044 | 25.701 ± 0.069 | 25.02 ± 0.062 | 25.148 ± 0.004 | 25.736 ± 0.037 | 26.795 ± 0.189 | 26.15 ± 0.006 | 32.065 ± 0.095 | 31.939 ± 0.055 | 25.68 ± 0.041 | 27.034 ± 0.009 |

| Test results | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O | O |

Application of the developed qPCR assay to commercial herbal medicines

A. capillaris ("Injinho") and A. iwayomogi ("Haninjin") are referred to with the same herbal medicine name ("InJin") in Korea. Therefore, the plants may be confused for each other when using them to manufacture commercial herbal products. The developed qPCR analysis was used to distinguish between “Injinho” and “Haninjin” in 16 commercial herbal medicines commonly known as “InJin”. The positive control used 18S rRNA primer to confirm the amplification ability of gDNA extracted from commercial products. (Allmann et al., 1993). As depicted in Table 5, the 18S rRNA primer set exhibited low Ct values (12.87–17.37 cycles), indicating that the amount of DNA extracted from all commercial products was adequate for PCR amplification. The six target-specific qPCR primer sets were assessed with the 16 “InJin” commercial products. Using A. capillaris species-specific primers (AC_ITS, AC_accD, and AC_rpoB), samples 1, 3, and 4 were amplified to Ct values lower (14.61–24.36 cycles) than the cut-off Ct values (Ct values of 0.1% A. capillaris-specific primer set in binary mixtures; Supplementary Fig. 2A) for each primer set; cut-off Ct values for AC_ITS, AC_accD, and AC_rpoB were 26.14, 28.61, and 28.35 cycles, respectively (Table 5). In contrast, using A. iwayomogi species-specific primers (AI_matK, AI_ycf1, and AI_rpoB), samples 5–16 were amplified to Ct values lower (17.96–25.25 cycles) than the cut-off Ct values (Ct values of 0.1% A. iwayomogi-specific primer set in binary mixtures; Supplementary Fig. 2B) for each primer set; cut-off Ct values for AI_matK, AI_ycf1, and AI_rpoB were 30.46, 27.09, and 28.51 cycles, respectively (Table 5). Therefore, for all samples except sample 2, using the non-target-specific qPCR primer sets resulted in a Ct value higher than the cut-off. Sample 2 had a higher Ct value than the cut-off Ct value, for all six species-specific primer sets, indicating that the sample could not be distinguished by any of the primer sets. Therefore, the developed qPCR systems could successfully detect identical species in commercial herbal medicines sold under the name “InJin” in the local market. We suggest that the target DNA (A. capillaris or A. iwayomogi) contained in commercial herbal medicines can be detected using the developed qPCR method.

Table 5.

Results of the real-time PCR assay using “Injin” commercial herbal medicines

| Primer sets | Labelled "InJin" commercial herbal medicines test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dried leaves | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| 18 s rRNA primer | 12.873 ± 0.098 | 14.301 ± 0.079 | 17.377 ± 0.052 | 15.872 ± 0.060 | 13.153 ± 0.040 | 13.026 ± 0.083 | 14.245 ± 0.445 | 13.785 ± 0.058 |

| A. capillaris | ||||||||

| ITS 26.14 cycles | 14.617 ± 0.114 | 30.918 ± 0.046 | 20.861 ± 0.117 | 19.415 ± 0.369 | 33.112 ± 0.106 | 34.693 ± 0.543 | 34.968 ± 0.762 | 33.457 ± 0.210 |

| accD 28.61 cycles | 17.951 ± 0.129 | 31.62 ± 0.546 | 23.537 ± 0.018 | 23.228 ± 0.014 | 34.823 ± 0.469 | 34.955 ± 0.493 | 35.009 ± 0.000 | 35.365 ± 0.112 |

| rpoB 28.35 cycles | 17.929 ± 0.091 | 31.837 ± 0.501 | 24.365 ± 0.107 | 23.41 ± 0.031 | 34.507 ± 0.349 | 33.909 ± 0.029 | 36.001 ± 3.352 | 33.78 ± 1.376 |

| A. iwayomogi | ||||||||

| matK 30.46 cycles | 35.033 ± 0.310 | 36.805 ± 0.270 | 33.993 ± 2.123 | 30.598 ± 0.408 | 21.801 ± 0.190 | 23.117 ± 0.239 | 20.756 ± 0.076 | 22.136 ± 0.156 |

| ycf1 27.08 cycles | 31.762 ± 0.392 | 37.016 ± 0.127 | 33.007 ± 0.145 | 30.993 ± 0.071 | 21.212 ± 0.002 | 20.826 ± 0.004 | 20.909 ± 0.068 | 19.129 ± 0.004 |

| rpoB 28.51 cycles | 34.458 ± 0.110 | 34.564 ± 0.473 | 34.504 ± 0.072 | 34.313 ± 0.102 | 22.491 ± 0.105 | 22.257 ± 0.043 | 22.098 ± 0.022 | 20.443 ± 0.143 |

| Primer sets | Labelled "InJin" commercial herbal medicines test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dried leaves | ||||||||

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| 18 s rRNA primer | 14.048 ± 0.035 | 14.048 ± 0.035 | 14.282 ± 0.038 | 14.925 ± 0.060 | 14.018 ± 0.054 | 14.819 ± 0.058 | 14.147 ± 0.148 | 13.716 ± 0.027 |

| A. capillaris | ||||||||

| ITS 26.14 cycles | 32.495 ± 0.396 | 34.046 ± 0.115 | 35.777 ± 1.692 | 35.231 ± 0.308 | 33.69 ± 0.268 | 35.724 ± 0.248 | 34.534 ± 0.772 | ND |

| accD 28.61 cycles | 34.917 ± 0.725 | 35.843 ± 0.482 | 37.244 ± 2.596 | 35.469 ± 0.161 | 36.521 ± 2.307 | 35.232 ± 0.506 | 36.867 ± 1.893 | 36.298 ± 0.835 |

| rpoB 28.35 cycles | 36.466 ± 2.339 | 35.364 ± 0.826 | 33.822 ± 1.796 | 35.011 ± 0.000 | 37.274 ± 2.579 | 38.643 ± 0.000 | 33.904 ± 0.031 | 28.231 ± 0.352 |

| A. iwayomogi | ||||||||

| matK 30.46 cycles | 23.674 ± 0.179 | 25.251 ± 0.729 | 21.098 ± 0.292 | 23.672 ± 0.244 | 22.967 ± 0.037 | 21.387 ± 0.295 | 22.043 ± 0.365 | 22.854 ± 0.049 |

| ycf1 27.08 cycles | 20.993 ± 0.044 | 21.472 ± 0.027 | 19.961 ± 0.029 | 20.742 ± 0.064 | 19.059 ± 0.081 | 19.122 ± 0.033 | 21.282 ± 0.044 | 19.984 ± 0.010 |

| rpoB 28.51 cycles | 22.083 ± 0.095 | 22.616 ± 0.059 | 21.263 ± 0.190 | 22.036 ± 0.161 | 20.747 ± 0.069 | 17.96 ± 0.034 | 22.362 ± 0.088 | 21.286 ± 0.057 |

In conclusion, the developed qPCR method was highly accurate and efficient for detecting target species in processed medicinal herbs. We designed three sets of six primers for the nuclear and chloroplast genomes for each specie (A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi). For relative quantification of the target species, a standard curve was plotted using ten-fold serially diluted (10 ng/µL to 1 pg/µL) DNA templates and a reference binary mixture model. The developed DNA markers were confirmed using 40 blinded sample analyses and commercial product tests for 14 other species. Thus, the DNA markers devised in this study could be used to establish a highly effective identification method to detect and distinguish between A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi, which are commonly used in the herbal medicine market. Overall, the developed qPCR analysis can be applied for regulatory monitoring of herbal medicines typically referred to as “Injin,” and thus can contribute to consumer food safety.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Figure 1: Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) primers designed for A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi. (A) A. capillaris-targeting primer sets (ITS, accD, and rpoB). (B) A. iwayomogi-targeting primer sets (matK, ycf1, and rpoB). Supplementary Figure 2: Cycle threshold (Ct) values were obtained based on the efficiency and correlation coefficient (R2) using dry-treated reference binary mixtures. A plot against the logarithm of the target species concentration (100%, 10%, 1%, and 0.1%) was generated: the x-axis represented the logarithm of the percentage of target species (%), and the y-axis represented average Ct value ± standard deviation (SD). (A) A. capillaris powders were mixed with A. iwayomogi powders via ten-fold dilutions (0.1%, 1%, 10%, and 100%; total mass of 2 g), and each mixture of gDNA (10 ng/µL) mixture was amplified using the A. capillaris-targeting primer sets (AC_ITS, AC_accD, and AC_rpoB). Red dotted line represents the 0.1% binary mixture Ct values (cut-off Ct values) for amplification using the A. capillaris-targeting primer sets (AC_ITS, AC_accD, and AC_rpoB); (B) A. iwayomogi powders were mixed with A. capillaris powders via ten-fold dilutions (0.1%, 1%, 10%, and 100%; total mass of 2 g), and each mixture of gDNA (10 ng/µL) was amplified using the A. iwayomogi-targeting primer sets (AI_matK, AI_ycf1, and AI_rpoB). Purple dotted line represents the 0.1% binary mixture Ct values (cut-off Ct values) for amplification using the A. iwayomogi-targeting primer sets (AI_matK, AI_ycf1, and AI_rpoB). Yellow dot, A. capillaris; green dot, A. iwayomogi. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed in triplicate (n = 3). (PPTX 512 kb)

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Grant (17162MFDS065) from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2020.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yea Dam Kim, Email: yeadam@kangwon.ac.kr.

Yo Ram Uh, Email: yoram@kangwon.ac.kr.

Cheol Seong Jang, Email: csjang@kangwon.ac.kr.

References

- Allmann M, Candrian U, Höfelein C, Lüthy J. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR): A possible alternative to immunochemical methods assuring safety and quality of food detection of wheat contamination in non-wheat food products. Zeitschrift Für Lebensmittel-Untersuchung Und Forschung. 1993;196:248–251. doi: 10.1007/BF01202741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An J, Moon JC, Jang CS. Markers for distinguishing Orostachys species by SYBR Green-based real-time PCR and verification of their application in commercial O. japonica food products. Applied Biological Chemistry. 61: 499–508 (2018)

- Baldwin BG, Sanderson MJ, Porter JM, Wojciechowski MF, Campbell CS, Donoghue MJ. The ITS region of nuclear ribosomal DNA: a valuable source of evidence on angiosperm phylogeny. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 1995;82:247–277. doi: 10.2307/2399880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer C. The MIQE Guidelines: Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments. Clinical Chemistry. 2009;55:611–622. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammà C, Di Domenico M, Monaco F. Development and validation of fast Real-Time PCR assays for species identification in raw and cooked meat mixtures. Food Control. 2012;23:400–404. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CBOL CPW, Hollingsworth PM, Forrest LL, Spouge, JL, Hajibabaei M, Ratnasingham S, Bank M, Chase MW, Cowan RS, Erickson DL, Fazekas AJ, Graham SW, James KE, Kim KJ, Kress WJ, Schneider H, AlphenStahl J, Barrett SCH, Berg C, Bogarin D, Burgess KS, Cameron KM, Carine M, Chacón J, Clark A, Clarkson JJ, Conrad F, Devey DS, Ford CS, Hedderson TAJ, Hollingsworth ML, Husband BC, Kelly LJ, Kesanakurti PR, Kim JS, Kim YD, Lahaye R, Lee HL, Long DG, Madriñán S, Maurin O, Meusnier I, Newmaster SG, Park CW, Percy DM, Petersen G, Richardson JE, Salazar GA, Savolainen V, Seberg O, Wilkinson MJ, Yi DK, Little DP. A DNA barcode for land plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106: 12794–12797 (2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- China Pharmacopoeia. The Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. 2015 Edition. Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. pp. 410–411 (2015)

- Choi JH, Kim DW, Yun N, Choi JS, Islam MN, Kim YS, Lee SM. Protective effects of hyperoside against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver damage in mice. Journal of Natural Products. 2011;74:1055–1060. doi: 10.1021/np200001x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Chinese Medicine and Pharmacy . Taiwanese Herbal Pharmacopoeia. 2. Ministry Health and Welfare: Chiu WT; 2013. pp. 208–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2014;4:177. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENGL (European Network of GMO Laboratories). Definition of Minimum Performance Requirements for Analytical Methods of GMO Testing. Available from: http://gmocrl.irc.ec.ecrl.jrc.ec.europa.eu/doc/MPR%20Report%20Application%2020_10_2015.pdf Accessed 20 October 2015

- Fumière O, Dubois M, Baeten V, von Holst C, Berben G. Effective PCR detection of animal species in highly processed animal byproducts and compound feeds. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2006;385:1045–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0533-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong E, Lee SY, Jeong JY, Park JM, Kim BH, Kwon K, Chun HS. Modern analytical methods for the detection of food fraud and adulteration by food category. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2017;97:3877–3896. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JH, Lee JW, Park JH, Lee IS. Antioxidative and cytoprotective effects of Artemisia capillaris fractions. Biofactors. 2007;31:43–53. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520310105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SG, Kim JH, Moon JC, Jang CS. Chloroplast markers for detecting rice grain-derived food ingredients in commercial mixed-flour products. Genes & Genomics. 2015;37:1027–1034. doi: 10.1007/s13258-015-0335-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SI, Kim YJ, Lee WY, Kwak KC, Baek SH, Kwak GB, Yun YG, Kwon TO, Chung HT, Chai KY. Scoparone from Artemisia capillaris inhibits the release of inflammatory mediators in RAW 264.7 cells upon stimulation cells by interferon-γ plus LPS. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 28: 203–208 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kane DE, Hellberg RS. Identification of species in ground meat products sold on the US commercial market using DNA-based methods. Food Control. 2016;59:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GS, Oh SH, Jang CS. Development of molecular markers to distinguish between morphologically similar edible plants and poisonous plants using a real-time PCR assay. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2021;101:1030–1037. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Rodrigues V, Baskaran K, Shukla AK, Sundaresan V. DNA barcode based species-specific marker for Ocimum tenuiflorum and its applicability in quantification of adulteration in herbal formulations using qPCR. Journal of Herbal Medicine. 2020;23:100376. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2020.100376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MY, Doh EJ, Kim ES, Kim YW, Ko BS, Oh SE. Application of the multiplex PCR method for discrimination of Artemisia iwayomogi from other Artemisia herbs. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2008;31:685–690. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MY, Doh EJ, Park CH, Kim YH, Kim ES, Ko BS, Oh SE. Development of SCAR marker for discrimination of Artemisia princeps and A. argyi from other Artemisia herbs. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 29: 629–633 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lo YT, Shaw PC. DNA-based techniques for authentication of processed food and food supplements. Food Chemistry. 2018;240:767–774. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loncarevic S, Økland M, Sehic E, Norli HS, Johansson T. Validation of NMKL method no. 136—Listeria monocytogenes, detection and enumeration in foods and feed. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 124: 154–163 (2008) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Market Research Future. Herbal Medicine Market Research Report—Forecast to 2023. Maharashtra: WantStats Research and Media Pvt. Ltd (2018)

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. The 16th revision of Japanese Pharmacopoeia. Yaksa Ilbo Co., Ltd., p 1602 (2011)

- Naaum A, Hanner R. (Eds.). Seafood authenticity and traceability: A DNA-based perspective. Academic Press. pp 134–135 (2016)

- Nigam M, Atanassova M, Mishra AP, Pezzani R, Devkota HP, Plygun S, Salehi B, Setzer WN, Sharifi-Rad J. Bioactive compounds and health benefits of Artemisia species. Natural Product Communications. 14: 1934578X19850354 (2019)

- Oh SH, Jang CS. Development and validation of a real-time PCR based assay to detect adulteration with corn in commercial turmeric powder products. Foods. 2020;9:882. doi: 10.3390/foods9070882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SH, Kim YD, Jang CS. Development and application of DNA markers to detect adulteration with Scopolia japonica in the medicinal herb Atractylodes lancea. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2022;31:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s10068-021-01008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno I, Uchida K, Kadowaki M, Akahori A. Choleretic effect of Artemisia capillaris extract in rats. The Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 1981;31:835–838. doi: 10.1016/S0021-5198(19)52807-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research and Markets. Europe Spice and Herb Extracts Market—Segmented by Type, Application, and Geography Growth, Trends and Forecasts (2018–2023). Dublin: Research and Markets (2018)

- Sasikumar B, Syamkumar S, Remya R, John Zachariah T. PCR based detection of adulteration in the market samples of turmeric powder. Food Biotechnology. 2004;18:299–306. doi: 10.1081/FBT-200035022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo KS, Jeong HJ, Yun KW. Antimicrobial activity and chemical components of two plants, Artemisia capillaris and Artemisia iwayomogi, used as Korean herbal Injin. Journal of Ecology and Environment. 2010;33:141–147. doi: 10.5141/JEFB.2010.33.2.141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo KS, Yun KW. Antioxidant activities of extracts from Artemisia capillaris Thunb. and Artemisia iwayomogi Kitam. used as InJin. Korean Journal of Plant Research. 21: 292–298 (2008)

- Seoul Metropolitan Government Research Institute of Public Health and Environment. A Simple and Comprehensive Herbal Medicine Guide. pp. 50–51 (2017)

- Shin TY, Park JS, Kim SH. Artemisia iwayomogi inhibits immediate-type allergic reaction and inflammatory cytokine secretion. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology. 2006;28:421–430. doi: 10.1080/08923970600927975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Kawa K, Eckl V, Morton C, Stredney R. Herbal supplement sales in US increase 7.7% in 2016. HerbalGram. 115: 56–65 (2017)

- The Government of the Hong Kong special Administrative Region. Hong Kong Chinese Materia Medica Standard. 6: 138–154 (2005)

- The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety The 4th revision of the Korean Herbal Pharmacopoeia (Herbal Medicine) Pharmaceutical Articles. Part. 2015;1:291–292. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation. Discrimination of Artemisiae Capillaris Herba. (2017a)

- The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation. Discrimination of Artemisiae Iwayomogii Herba. (2017b)

- Wang JH, Choi MK, Shin JW, Hwang SY, Son CG. Antifibrotic effects of Artemisia capillaris and Artemisia iwayomogi in a carbon tetrachloride-induced chronic hepatic fibrosis animal model. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;140:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JS, Reed A, Chen F, Stewart CN. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) primers designed for A. capillaris and A. iwayomogi. (A) A. capillaris-targeting primer sets (ITS, accD, and rpoB). (B) A. iwayomogi-targeting primer sets (matK, ycf1, and rpoB). Supplementary Figure 2: Cycle threshold (Ct) values were obtained based on the efficiency and correlation coefficient (R2) using dry-treated reference binary mixtures. A plot against the logarithm of the target species concentration (100%, 10%, 1%, and 0.1%) was generated: the x-axis represented the logarithm of the percentage of target species (%), and the y-axis represented average Ct value ± standard deviation (SD). (A) A. capillaris powders were mixed with A. iwayomogi powders via ten-fold dilutions (0.1%, 1%, 10%, and 100%; total mass of 2 g), and each mixture of gDNA (10 ng/µL) mixture was amplified using the A. capillaris-targeting primer sets (AC_ITS, AC_accD, and AC_rpoB). Red dotted line represents the 0.1% binary mixture Ct values (cut-off Ct values) for amplification using the A. capillaris-targeting primer sets (AC_ITS, AC_accD, and AC_rpoB); (B) A. iwayomogi powders were mixed with A. capillaris powders via ten-fold dilutions (0.1%, 1%, 10%, and 100%; total mass of 2 g), and each mixture of gDNA (10 ng/µL) was amplified using the A. iwayomogi-targeting primer sets (AI_matK, AI_ycf1, and AI_rpoB). Purple dotted line represents the 0.1% binary mixture Ct values (cut-off Ct values) for amplification using the A. iwayomogi-targeting primer sets (AI_matK, AI_ycf1, and AI_rpoB). Yellow dot, A. capillaris; green dot, A. iwayomogi. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed in triplicate (n = 3). (PPTX 512 kb)