Abstract

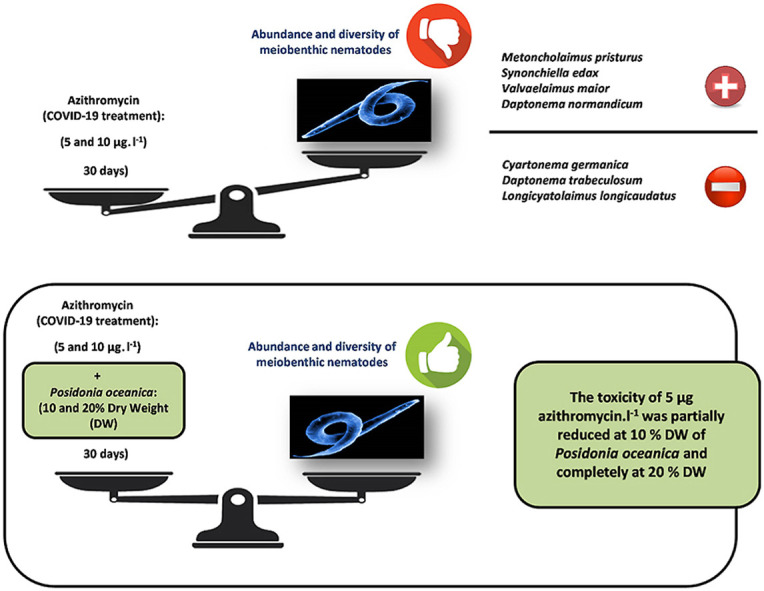

The current study presents the results of an experiment carried to assess the impact of azithromycin, a COVID-19 drug, probably accumulated in marine sediments for three years, since the start of the pandemic, on benthic marine nematodes. It was explored the extent to which a common macrophyte from the Mediterranean Sea influenced the toxic impact of azithromycin on meiobenthic nematodes. Metals are known to influence toxicity of azithromycin. The nematofauna from a metallically pristine site situated in Bizerte bay, Tunisia, was exposed to two concentrations of azithromycin [i.e. 5 and 10 μg l−1]. In addition, two masses of the common macrophyte Posidonia oceanica [10 and 20% Dry Weight (DW)] were considered and associated with azithromycin into four possible combinations. The abundance and the taxonomic diversity of the nematode communities decreased significantly following the exposure to azithromycin, which was confirmed by the toxicokinetic data and behaving as substrate for P-glycoprotein (P-gp). The toxicity of 5 μg l−1 dosage of azithromycin was partially reduced at 10% DW of Posidonia and completely at 20% DW. The results showed that 5 μg l−1 of azithromycin can be reduced by the macrophyte P. oceanica when present in the environment at low masses as 10% DW.

Keywords: COVID-19 crisis, Azithromycin, Posidonia oceanica, Ecotoxicity, Meiobenthic nematodes, Toxicokinetics

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Aquatic products and animals are essential nutrients in the human diet and are also present in the global aquatic product industry for consumers (Selamoglu, 2021a). Therefore, we need to protect our aquatic environment against to pollution on various environmental and ecological effects. The aquatic ecosystems and living organisms suffer from environmental impact by emissions of volatile organic substances, and pollution of water by oil chemicals and many various hazardous agents (Selamoglu, 2021b). The pollution of aquatic habitats with emerging pharmaceuticals has particularly become a serious environmental issue over the past decades, paralleled by challenging tasks for analytical chemistry, which needs to develop up to date tools for their precise and fast measurement in water or sediment samples (Minguez et al., 2016). The emerging pollutants comprise a new class of compounds that add up to the traditional list of chemical parameters measured during routine sampling programs that estimate the water quality. Assessing their toxicity and their synergic intercations in the environment comprise recent and challenging research questions, since these molecules were proved to be biologically active, to have detrimental effects on aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems alike and, in the end, on human health (Algros, 2018).

The Coronavirus Infectious Disease 2019(COVID-19) was until recently a pandemic crisis, caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome COronaVirus strain 2 (SARS-CoV-2, see Whitworth, 2020). The first casualties were recorded in Wuhan, China, during December 2019 and afterwards it became universal, with multiple negative effects on humans’ health and worldwide economy. As of October 15, 2022, 624,288,971 total cases (12,836,369 28-day cases) and 6,566,462 total deaths (40,225 28-day deaths) were globally recorded because of COVID-19 (https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html?fbclid=IwAR0-JhqnSy-s-gfnCAw0hvBFOqSEirVVdeDW38bCQWEx7ovbITkYmdDaReo#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6).

Starting with 2022, the number of casualties dropped, following a global compaign of vaccination, which contributed massively to the end of this pandemic. However, new questions arrised for scientists, mainly related to the environmental impacts of various drugs used for almost 3 years as COVID-19 treatments (e.g., lopinavir, ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, xanthine, and azithromycin, respectivly) and the way their toxicity interacted with macrophyte debris, a common presence in aquatic habitats.

Many COVID-19 epicenters were located in European countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, such as France, Spain, and Italy (https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html?fbclid = iwar0-jhqnsy-s-gfncawbfoqseirvdw38bcqwex7ovbitkymdareo#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6). One of the seemingly successful drugs used against the SARS-CoV-2 variant Omicron was the azithromycin, associated with the co-factor zinc (Poupaert, 2020). This antibiotic was previously proved to induce both chronic and acute toxic effects on wildlife, including the marine biota (Shiogiri et al., 2017). Indeed, the toxicity of azythromycin was investigated by experiments carried mainly on fish species such as the Chinook salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Fairgrieve et al., 2005), the tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Shiogiri et al., 2017), and the zebrafish Danio rerio (Mendonça-Gomes et al., 2021). The results found supported diverse physiological effects and a reduction in total protein levels. However, as recommended by Goodsell et al. (2009), we think here that such a choice of specific sentinel taxa located at enough high trophic level as bioindicators may not be as good due to the delayed irritating signal compared to the components of the small food web: meiofauna, protists, and bacteria. The first step for preventing of the health risks and establishing strict thresholds for the azithromycin must be knowledge of small bioindicators at the base of the marine food chain as it is the case for the dominant meiobenthic group of nematodes.

The meiobenthos (40 μm - 1 mm, Vitiello & Dinet, 1979) comprises numerous phyla that proved to be successful bioindicators in biomonitoring surveys and ecotoxicological experiments. Usually, one of the characteristics of meiobenthos is the short life cycle (a few weeks to months, Austen et al., 1994), benthic larval stages (Schratzberger et al., 1999), high densities, and ubiquitous distribution in various marine habitats, covering a broad spectrum of tolerances against various contaminants (; Guo et al., 2001). In addition, because of their small body-size, the meiobenthos usually comprises an intermediary link in aquatic food webs, hence an important step in the transfer of pollutants to upper trophic levels, humans included (Moens and Vincx, 1997). Among various meiobenthic groups, the most abundant (up to 23 million. m−2, Warwick and Price, 1979) and diverse (more than 8000 known species, Boufahja et., 2014) is the one of the free-living nematodes. Their utility as suitable ecological indicators was emphasised by many studies (Austen et al., 1994; Mahmoudi et al., 2005; Beyrem et al., 2007; Armenteros et al., 2009; Boufahja et al., 2016; Allouche et al., 2022).

The objective of the current work was to examine experimentally the impact of the rather abusively use of the azithromycin on a representative invertebrate-macrophyte marine association, comprising meiobenthic nematofauna in the presence or absence of Posidonia oceanica, a common dweller in the Mediterranea basin (Telesca et al., 2015). The current experiment tested to which extent the presence of P. oceanica, a common macrophyte in the Mediterranean Sea basin, interacts with the unknown effects of azithromycin on the meiobenthic nematofauna. We believe that this topic is of current concern, given that several countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea used this drug as a treatment against SARS-CoV-2. Thus, high quantities of azithromycin were suspected to have reached the infralittoral zone during the past three years, with unknown effects on the marine environment and the quality of the seafood consumed by humans. Furthermore, toxicokinetic parameters of azithromycin were assessed based on the absortion, distribution, metabolism, elimination and toxicity (ADMET) properties.

2. Materials and methods

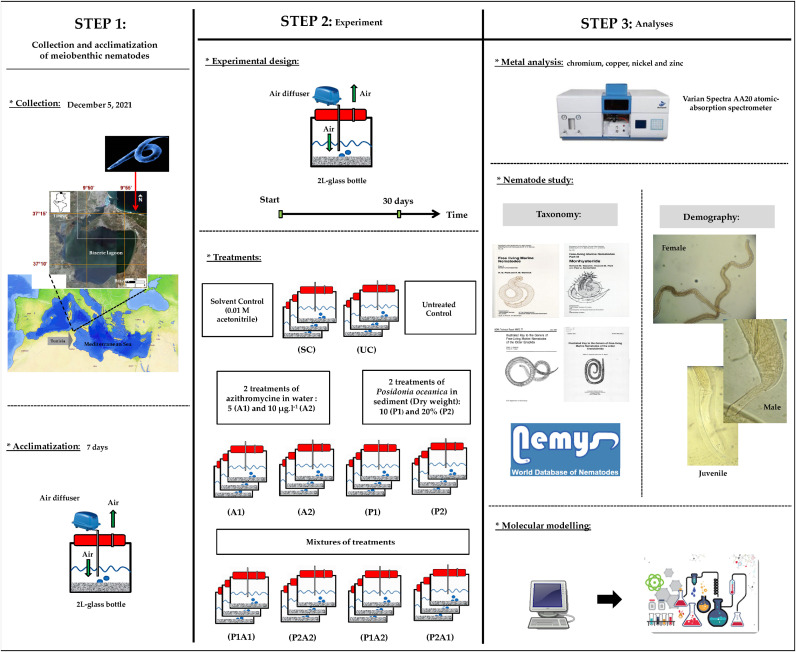

A graphical presentation illustrating the timeline and experimental design and the analyzes performed is shown in Fig. 1 . Details of all followed steps and methods are given below.

Fig. 1.

Graphical summary of steps and methodology adopted.

2.1. Sampling and sediment analyses

Water and sediment samples were taken early in the morning (7 a.m.) of the December 5th, 2021 from a subtidal site situated in the Bizerte Bay, Tunisia (37°15′07.34″N, 9°56′26.75″E). This pristine dissipative beach is an undisturbed flat, with fine sand; where waves are breaking far from the intertidal area in directions N–S and NW–SE, and dissipating their force along wide surf zones as reported Ben Garali et al. (2008). The suitability of this location and metals monitored during the current work were validated referring to the following bases: (1) the concentrations of chosen three metals (chromium, copper, and nickel) were previously measured by Hedfi et al. (2013) in the same location which will allow to compare, (2) a fourth metal was also considered (zinc) since it is commonly prescribed with azithromycin as a COVID-19 treatment, and (3) the nematode assemblage was acceptably diverse (species richness: 18–35 according to Beyrem and Aïssa (2000) and Hedfi et al. (2013)).

The sediment was taken at 50 cm depth with Plexiglass hand-cores (10 cm2 section, 3.6 cm inner diameter), following Coull and Chandler (1992). At the sampling site, four environmental parameters (i.e., pH, temperature, salinity, and dissolved oxygen) were measured at the sediment-water interface by using a pH meter, a temperature/conductivity meter (WTW LF 196, Weilheim, Germany), and an Oximeter (WTW OXI 330/SET, WTW, Weilheim, Germany), respectively. In the laboratory, part of the sampled sediment was homogenized with a wide spatula to measure the proportion of coarse particles (larger than 63 μm), mean grain-size, and the water content, whereas the rest was used for fill microcosms, each with a mass of with 300 g Wet Weight. Three sedimentary subsamples, each of 100 g, were oven dried (45 °C for 96 h) to determine the water content in % (Boufahja et al., 2016). The dried sediment was used for quantifying total organic matter by ignition at 450 °C for 6 h (Fabiano and Danovaro, 1994). Other dried sediment sub-samples were sieved through a 63-μm-mesh size to first separate the silt/clay particles (Mahmoudi et al., 2007). Afterwards, cumulative curves were plotted for the coarse fraction to estimate the mean grain-size (Buchanan, 1971). For the extraction of the metals from the sediment (chromium, copper, nickel, and Zinc), three 15-g aliquots of dried sediment were digested after refluxing with trace-metal grade HNO3 (90 ml) at 95 °C for 1 h. These chosen metals may originate in Bizerte coasts from the steel manufacturing firm Fouledh (37°13′69.8″, 9°81′39.2″), located in the City of Menzel Bourguiba, Tunisia. Their concentrations were determined with the aid of a Varian Spectra AA20 atomic-absorption spectrometer with an air/acetylene flame and an auto-sampler (Yoshida et al., 2004; Boufahja and Semprucci, 2015).

2.2. Experimental set-up

Microcosms comprised 2 L glass bottles filled with 200 g of sediment and topped up with filtered seawater (0.7 μm pore-size Glas Microfibre GF/F, Whatman)). Each microcosm operated as a closed system, with continuous ventilation provided by an aquarium pump. The reliability of the current experimental devices was tested previously by several authors (Austen et al., 1994; Mahmoudi et al., 2005; Essid et al., 2020; Wakkaf et al., 2020; Hedfi et al., 2021).

2.3. Sediment contamination

Following a week of acclimatization, different treatments, including azithromycin (hereafter A) and the presence or absence of P. oceanica (P) were included in the experimental design. Following Amaral et al. (2019) and Mendonça-Gomes et al. (2021), azithromycin stock solutions were prepared, by using azithromycin dihydrate draggers (500 mg) diluted in acetonitrile solution (0.01 M).

The concentrations of azithromycin used in the current experiment were based on the previous recommendations of Fernandes et al. (2020) and Mendonça-Gomes et al. (2021). The former authors reported that azithromycin was detected in concentrations as high as 2.8 μg l−1 in a river from Portugal. The concentration tested by the latter author (i.e. 12.5 μg l−1) was found to be effective in inducing after 72 h exposure for the adults of the zebrafish Danio rerio the reduction of total protein levels, as well as changes in oxidative stress and neurotoxicity, suggesting potential increase of azithromycin concentration in aquatic habitats. Herein, two lower concentrations were chosen to better identify the significant cumulative threshold: 5 μg l−1 (hereafter A1) and 10 μg l−1 (hereafter A2). The concentrations of P. oceanica chosen were derived from the work of Allouche et al. (2021), who observed significant reduction in the density and taxonomic diversity of nematodes, following their exposure to sediment concentrations of 33% Dry Weight (DW) of minced leaves of P. oceanica (40–63 μm). Hence, two lower concentrations were used in the current experiment: 10 and 20% DW. In total, nine types of experimental microcosms were installed: an untreated control (hereafter UC), a solvent control (hereafter SC: 0.01 M acetonitrile), two Posidonia concentrations (hereafter P1 and P2), two azethromycin concentrations (hereafter A1 and A2), and their mixtures (i.e., P1A1, P2A2, P2A1, P1A2). Three replicates were used for both individual and combined treatments. The experiment ended after 30 days and the sediment from each microcosm was preserved in 4% neutralized formaldehyde with hexamethylenetetramine for further study of nematofauna.

2.4. Nematode study

The nematodes were sorted first through of the levigation-decanting-sieving method (Vitiello and Dinet, 1979). Two stacked sieves, of 1 mm and 40 μm mesh size, were used. The upper sieve excluded the macrofauna and large debris and the lower sieve retained the meiofauna. The organisms retained on the lower sieve were transferred in 4% neutralized formaldehyde solution until further counting and microscopic examination. Few drops of the aqueous solution of Rose Bengal (0.2 g.L−1) were added to color in pink the living organisms (Guo et al., 2001). The counting of meiofauna was performed in a dollifus plate with a tiled bottom (200 squares of 5 mm2) by using a 50 × dissecting microscope (Model WildHeerbrugg M5A. For each replicate, a maximum of 100 nematodes were picked up randomly (Kotta and Boucher, 2001) with a fine niddle and mounted on microscopic slides (Seinhorst, 1959) for further taxonomic identification with three generic keys (Platt and Warwick, 1983, 1988; Warwick et al., 1998). The species were determined based on descriptions from the Nemys database (Nemys eds., 2022). The taxonomic diversity of the nematode assemblages exposed to different treatments was assessed by using Species number (S) and Margalef's species Richness (d). Moreover, all individuals observed were classified as juveniles (J), males (M), and females (F), and the M/F and J/F ratios calculated.

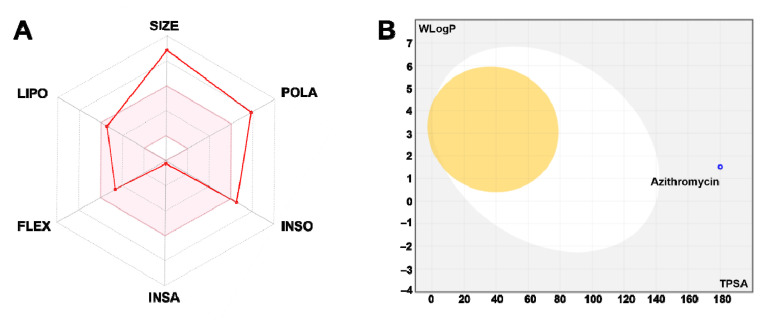

2.5. Toxicokinetic assessment

Effects of a given toxin/pollutant also depend on its 3D chemical structure that mediates the toxicokinetics and thus its molecular interactions with target receptors (Allouche et al., 2022; Badraoui et al., 2022). Toxicokinetic attributes of azithromycin were assessed based on the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity (ADMET) parameters as previously reported [A,B,C]. The bioavailability, which depends mainly on the physico-chemical characteristics: molecular size (SIZE), lipophiliciy (LIPO), insolubility (INSO), insaturation (INSA), polarity (POLA) and flexibility (FLEX) of azithromycin was also assessed [B,D,E].

2.6. Data processing

The statistical analyses followed the standard methods described by Clarke (1993) and Clarke and Warwick (2001) and were performed with STATISTICA (v5.1) software. Data were first tested for normality and homogeneity of variance, using Bartlett test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, respectively. Then, one-way analysis of variance (1-ANOVA) was used to compare the following univariate indices among treatments: abundance, species number (S), and Margalef's Species Richness (d), followed by Tukey's HSD post-hoc tests (log-transformed data). The comparisons between demographic ratios were performed based on separate chi-square randomization tests by using Ecosim software version 7 (Gotelli and Entsminger, 2005). Moreover, three multivariate analyzes were performed with the PRIMER v.5 software (Clarke and Gorley, 2001). First, the community structure in various treatments were graphically represented by using the non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (nMDS) plots, based on √-ransformed species abundances and Bray-Curtis similarity coefficients. Second, the ANalysis Of SIMilarity test (ANOSIM) (Clarke, 1993) was used to analyse for differences among the communities among treatments. Third, the SIMPER (Simper Percentages) procedure (Clarke, 1993) was used to determine the contribution of each species to the average Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between the control microcosms and treatments.

3. Results

3.1. Abiotic variables

On the sampling day, four abiotic parameters were measured in-situ, as follows: depth = 45 cm, temperature = 14.6 °C, pH = 8.12, salinity = 37.3, and dissolved oxygen = 7.8 mg l−1. The sediment parameters evaluated in laboratory included the organic matter proportion (0.82 ± 0.05%) and three granulometry descriptors: 92.77 ± 3.21% coarse particles, 7.23 ± 3.21% silt/clay particles, and mean grain size of 0.45 ± 0.08 mm. Final concentrations of chromium, copper, nickel, and zinc measured in sediment at the end of the experiment are given in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Concentrations of metals (parts per million Dry Weight ± SD) in sediment collected on December 5th, 2021 from a subtidal site situated in the Bizerte bay, Tunisia (37°15′07.34″N, 9°56′26.75″E). TEL = Threshold Effects Eevel of NOAA (1999) for marine sediment.

| References | Copper | Nickel | Chromium | Zinc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedfi et al. (2013) | 12.1 ± 3.3 | 10.2 ± 3.3 | 11.4 ± 1.7 | – |

| Present study | 15.7 ± 1.3 | 11.8 ± 1.1 | 9.7 ± 2.4 | 26.1 ± 3.7 |

| TEL (NOAA, 1999) | 18.7 | 15.9 | 52.3 | 124 |

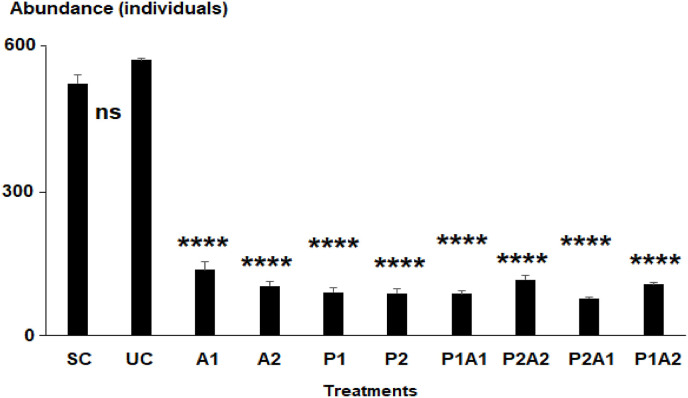

3.2. Abundance

The control microcosms ‘SC’ and ‘UC’ had significantly the highest average abundances of nematodes (524 ± 18 and 573 ± 4 individuals, respectively). Those related to all treatments applied showed significantly reduced abundances (Fig. 2 , 1-ANOVA: df = 20, F = 268.4, p < 0.001, Tukey's HSD test: p < 0.00001).

Fig. 2.

Average abundance of the nematofauna in the control microcosms with (SC) or without acetonitrile (UC) used as a solvent of azithromycin and those enriched with azithromycin (A1 and A2), leaves of Posidonia oceanica (P1 and P2) and their mixtures (P1A1, P2A2, P1A2 and P2A1). The four stars indicate the significant differences compared to the controls UC at p < 0.00001 (Tukey's HSD test, log-transformed data). No significant difference (ns).

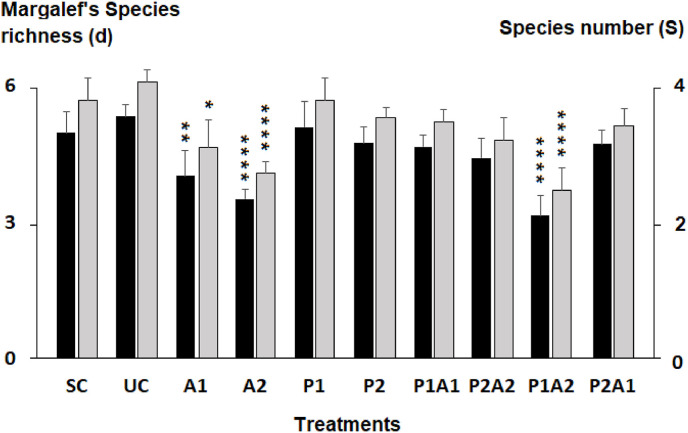

3.3. Taxonomic diversity and multivariate analyses

Twenty-seven species belonging to 24 genera of meiobenthic nematodes were identified in the solvent and control, as well as in the microcosms treated with azithromycin and/or Posidonia oceanica (Table 2 ). Three genera comprised two species: Daptonema sp., Marylynnia sp., and Sabatieria sp. The solvent and control nematode communities were very similar (Table 2). Twenty-seven species were identified in the treatment A1, 20 in treatment A2, 26 in P1, and 25 in P2 (Table 2). The nematofauna from P1A1 and P2A2 comprised 25 and 24 taxa, respectively. Twenty-sex species were found in the mixture P2A1 and 24 in P1A2. The Margalef's Species Richness had the lowest mean values in A2 and P1A2 (Tukey's HSD tests, p < 0.00001, Fig. 3 ).

Table 2.

Taxonomic structure of the nematofauna in the control microcosms with (SC) or without acetonitrile (UC) used as a solvent of azithromycin and those enriched with azithromycin (A1 and A2), leaves of Posidonia oceanica (P1 and P2) and their mixtures (P1A1, P2A2, P1A2 and P2A1). The values correspond to the average relative abundances (SD). Trophic groups [Selective deposit feeders (1 A); non-selective deposit feeders (1 B); epigrowth feeders (2 A); omnivores-carnivores (2 B)]; Caudal forms [clavate/conico-cylindrical (cla); conical (co); elongated/filiform (e/f); short/rounded (s/r)].

| Species (functional groups) | SC | UC | A1 | A2 | P1 | P2 | P1 A1 | P2 A2 | P2A1 | P1A2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bathylaimus tenuicaudatus (cla, 1 B) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 3.74 (1.58) | 0.77 (0.67) | 4.58 (1.07) | 5.66 (1.52) | 4.66 (2.51) | ||

| Cyartonema germanica (co, 1 A) | 6.33 (1.52) | 7 (2.65) | 0.33 (0.58) | 4.17 (2.03) | 1.42 (1.23) | 2.38 (2.21) | 0.66 (0.57) | 5.64 (3.38) | 1.66 (1.15) | |

| Daptonema fallax (cla, 1 B) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 2.26 (1.19) | 2.32 (1.17) | 1.14 (0.07) | 0.33 (0.57) | 4.71 (1.98) | 8 (1) | ||

| Daptonema normandicum (cla, 1 B) | 2.66 (1.15) | 7.33 (3.21) | 1 (1.75) | 7.92 (2.68) | 8.16 (2.74) | 0.78 (0.68) | 1 (1) | 6.80 (2.97) | ||

| Daptonema trabeculosum (cla, 1 B) | 0.66 (0.57) | 0.66 (0.58) | 3.66 (1.53) | 5.75 (1.52) | 5.61 (2.80) | 5 (3.46) | 0.41 (0.71) | 9.66 (1.52) | ||

| Enoplolaimus longicaudatus (cla, 2 B) | 3 (1) | 0.66 (1.15) | 0.33 (0.58) | 7.58 (2.11) | 12.29 (2.82) | 1.48 (1.72) | 0.33 (0.57) | 7.70 (4.67) | ||

| Halalaimus gracilis (e/f, 1 A) | 3.33 (1.52) | 1.33 (0.58) | 4 (1) | 4.07 (1.04) | 1.48 (0.66) | 1.51 (0.62) | 11.40 (1.86) | 7 (1) | 2.60 (1.35) | 12 (4.35) |

| Halaphanolaimus sp. (cla, 1 A) | 18 (1) | 18 (3.61) | 12 (2) | 13.87 (3.43) | 20.68 (5.47) | 21.22 (4.81) | 4.49 (2.02) | 12 (4) | 18.83 (1.97) | |

| Longicyatholaimus longicaudatus (e/f, 2 A) | 2.33 (0.57) | 3.33 (2.08) | 0.66 (0.58) | 3.5664 | 3.63 (2.05) | 2.34 (1.31) | 6.96 (4.10) | 1.66 (2.08) | ||

| Marylynnia puncticaudata (e/f, 2 A) | 3.33 (0.57) | 7 (1.73) | 9.33 (1 53) |

1.69 (1.56) | 7.75 (2.02) | 8.06 (2.42) | 12.94 (1.02) | 2.66 (1.15) | 6.47 (2.37) | 18.33 (7.09) |

| Marylynnia stekhoveni (e/f, 2 A) | 3.33 (1.52) | 1 (1.73) | 2 (2) | 0.67 (0.58) | 1.20 (2.08) | 1.29 (2.24) | 3.84 (1.41) | 5 (2) | 0.43 (0.75) | 0.33 (0.57) |

| Metoncholaimus pristiurus (cla, 2 B) | 3.33 (0.57) | 0.66 (1.15) | 10 (2) | 8.81 (2.12) | 0.80 (1.39) | 0.86 (1.49) | 0.36 (0.62) | 10 (2.64) | 1.28 (0.04) | |

| Microlaimus honestus (co, 2 A) | 14.67 (2.08) | 15 (3.61) | 14.33 (3.21) | 6.44 (1.59) | 4.26 (2.42) | 0.37 (0.64) | 1.47 (1.27) | 5.66 (3.78) | 4.66 (2.46) | |

| Odontophora villoti (co, 1 B) | 0.66 (1.15) | 1.33 (0.58) | 0.33 (0.58) | 0.66 (1.15) | 1.51 (0.78) | 1.58 (0.88) | 1 (0) | 0.87 (0.75) | 0.33 (0.57) | |

| Oncholaimellus calvadocicus (cla, 2 B) | 3.33 (0.57) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 5.43 (1.61) | 2.24 (1.26) | 2.35 (1.41) | 1.52 (0.63) | 4 (2) | 3.89 (1.39) | 0.33 (0.57) |

| Paramonohystera proteus (cla, 1 B) | 7.33 (0.57) | 7.33 (2.08) | 4.66 (2.08) | 7.81 (1.63) | 8.15 (2.61) | 8.49 (3.07) | 12.19 (2.01) | 11.33 (2.51) | 4.25 (1.78) | 10.33 (3.51) |

| Parasphaerolaimus paradoxus (cla, 2 B) | 2.33 (1.15) | 2.33 (1.53) | 2.33 (0.58) | 1.34 (1.52) | 2.48 (1.41) | 2.54 (1.44) | 6.21 (2.72) | 2.66 (1.15) | 1.72 (2.01) | 1 (0) |

| Phanodermopsis sp. (s/r, 2 A) | 1 (1) | 1.33 (1.15) | 0.33 (0.58) | 1.55 (1.34) | 1.60 (1.40) | 4.65 (2.16) | 0.66 (0.57) | 0.41 (0.71) | 1 (1.73) | |

| Prochromadorella longicaudata (co, 2 A) | 1.66 (0.57) | 2.66 (1.53) | 1 (1) | 3.72 (1.52) | 2.89 (1.64) | 2.94 (1.57) | 2.64 (1.61) | 2.66 (2.08) | 1.26 (1.23) | 0.33 (0.57) |

| Synonchiella edax (cla, 2 B) | 1.66 (0.57) | 1.33 (1.53) | 5.66 (2.08) | 9.52 (3.23) | 1.85 (1.31) | 1.88 (1.25) | 6.14 (1.49) | 10.33 (3.21) | 1.28 (1.31) | 7.33 (3.05) |

| Sabatieria pulchra (cla, 1 B) | 1 (1) | 1.66 (0.58) | 0.33 (0.58) | 3.41 (3.12) | 1.84 (0.65) | 1.92 (0.75) | 3.03 (0.49) | 2.33 (2.08) | 0.85 (0.73) | 5.33 (2.30) |

| Sabatieria punctata (cla, 1 B) | 2 (1) | 2.66 (1.15) | 1.33 (2.31) | 2.36 (2.09) | 2.88 (0.96) | 2.98 (1) | 2.66 (3.05) | 1.70 (1.47) | ||

| Spirinia parasitifera (co, 2 A) | 3.66 (1.52) | 2.33 (1.53) | 2.66 (0.58) | 0.34 (0.58) | 2.56 (1.71) | 2.60 (1.64) | 1.19 (1.23) | 5.15 (1.32) | 1.66 (1.52) | |

| Thalassironus britannicus (co, 2 B) | 3.33 (0.57) | 1.66 (1.15) | 5 (1) | 5.72 (3.48) | 1.77 (1.06) | 1.83 (1.09) | 0.78 (0.68) | 2.33 (2.51) | 0.43 (0.75) | 0.33 (0.57) |

| Theristus modicus (co, 1 B) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) | 7.33 (1.53) | 4.07 (1.77) | 4.02 (1.53) | 4.19 (1.70) | 1.88 (0.56) | 3 (3) | 6.00 (1.97) | 7 (3) |

| Thoonchus inermis (cla, 2 B) | 2.33 (1.15) | 1.33 (1.15) | 1.33 (1.53) | 1.46 (1.28) | 1.55 (1.37) | 3.01 (2.02) | ||||

| Valvaelaimus maior (co, 1 B) | 1.66 (0.57) | 2.33 (0.58) | 8 (1) | 10.49 (1.41) | 2.26 (1.19) | 2.32 (1.17) | 6.84 (0.72) | 1.66 (1.52) | 2.57 (1.31) | 8.66 (1.52) |

Fig. 3.

Species number and Margalef's Speciess Richness (d) of the nematofauna in the control microcosms with (SC) or without acetonitrile (UC) used as a solvent of azithromycin and those enriched with azithromycin (A1 and A2), leaves of Posidonia oceanica (P1 and P2) and their mixtures (P1A1, P2A2, P1A2 and P2A1). The stars indicate the significant differences compared to the controls UC (* = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.001; **** = p < 0.00001) (Tukey's HSD test, log-transformed data).

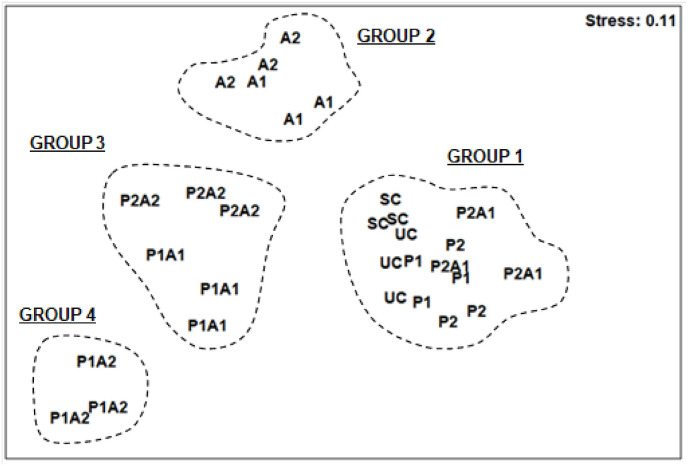

The non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) ordination had a stress value of 0.11. Overall, three groups of assemblages were apparent (Fig. 4 ): SC-UC-P1-P2-P2A1 (Group 1), A1-A2-P2A2 (Group 2), and P1A1-P1A2 (Group 3). The analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) outcomes showed significant differences in the structure of nematode communities among treatments (p = 0.01). The R-statistic values and average Bray-Curtis dissimilarity percentages between untreated control nematofauna and solvent controls, as well as among treatments increased from the first (R-value = 0.296–0.556; dissimilarity = 17.65–24.79%) to the third group (R-value = 1; dissimilarity = 39.36–47.3%) (Table 3 ).

Fig. 4.

Non-metric Multidimensal Scaling analysis (nMDS) applied on √-transformed abundances of nematode species collected from the control microcosms with (SC) or without acetonitrile (UC) used as a solvent of azithromycin and those enriched with azithromycin (A1 and A2), leaves of Posidonia oceanica (P1 and P2) and their mixtures (P1A1, P2A2, P1A2 and P2A1).

Table 3.

Analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) and nematodes species responsible for average dissimilarity (AD) between in the control microcosms with (SC) or without acetonitrile (UC) used as a solvent of azithromycin and those enriched with azithromycin (A1 and A2), leaves of Posidonia oceanica (P1 and P2) and their mixtures (P1A1, P2A2, P1A2 and P2A1) on the basis of SIMPER analysis (Similarity Percentages). More abundant (+); less abundant (−); stable abundance (st); elimination (Ø). Only species contributing to ∼50% of the average dissimilarity between compared treatments were indicated and ranked according to the importance of their contribution to dissimilarity.

| Comparisons | AD (%) | ANOSIM | Species | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC vs. SC | 18.91 | R = 0.296 p = 0.07 |

Metoncholaimus pristiurus (+) Marylynnia stekhoveni (+) Enoplolaimus longicaudatus (+) Daptonema trabeculosum (−) Odontophora villoti (−) Marylynnia puncticaudata (−) Thoonchus inermis (+) Phanodermopsis sp. (−) Halalaimus gracilis (+) |

||||

| Comparisons | AD (%) | ANOSIM | Species | Comparisons | AD (%) | ANOSIM | Species |

| UC vs. A1 | 32.64 | R = 1 p = 0.01 |

Metoncholaimus pristiurus (+) Cyartonema germanica (−) Daptonema trabeculosum (−) Valvaelaimus maior (+) Theristus pertenuis (ø) Daptonema normandicum (+) Sabatieria punctata (−) Synonchiella edax (+) Longicyatholaimus longicaudatus (−) |

UC vs. P1A1 | 39.36 | R = 1 p = 0.01 |

Microlaimus honestus (−) Halaphanolaimus sp. (−) Halalaimus gracilis (+) Daptonema trabeculosum (−) Sabatieria punctata (ø) Daptonema normandicum (+) Marylynnia stekhoveni (+) Cyartonema germanicum (−) |

| UC vs. A2 | 34.26 | R = 1 p = 0.01 |

Daptonema trabeculosum (ø) Cyartonema germanica (ø) Metoncholaimus pristiurus (+) Valvaelaimus maior (+) Synonchiella edax (+) Longicyatholaimus longicaudatus (ø) Daptonema nomandicum (+) Marylynnia puncticaudata (−) |

UC vs. P1A2 | 47.30 | R = 1 p = 0.01 |

Halaphanolaimus sp. (ø) Microlaimus honestus (ø) Daptonema trabeculosum (ø) Daptonema normandicum (+) Halalaimus gracilis (+) Sabatieria punctata (ø) Marylynnia puncticaudata (+) Valvaelaimus maior (+) Synonchiella edax (+) |

| UC vs. P1 | 17.65 | R = 0.333 p = 0.01 |

Enoplolaimus longicaudatus (+) Microlaimus honestus (−) Bathylaimus tenuicaudatus (−) Cyartonema germanica (−) Marylynnia stekhoveni (st) Daptonema normandicum (ø) Thoonchus inermis (st) |

UC vs. P2A1 | 24.79 | R = 0.556 p = 0.01 |

Microlaimus honestus (−) Enoplolaimus longicaudatus (+) Bathylaimus tenuicaudatus (ø) Metoncholaimus pristiurus (+) Longicyatholaimus longicaudatus (+) |

| UC vs. P2 | 22.25 | R = 0.444 p = 0.01 |

Microlaimus honestus (−) Enoplolaimus longicaudatus (+) Cyartonema germanica (−) Bathylaimus tenuicaudatus (ø) Marylynnia stekhoveni (st) |

UC vs. P2A2 | 36.29 | R = 1 p = 0.01 |

Metoncholaimus pristiurus (+) Cyartonema germanica (−) Synonchiella edax (+) Daptonema trabeculosum (−) Longicyatholaimus longicaudatus (ø) Marylynnia stekhoveni (+) Microlaimus honestus (−) Halalaimus gracilis (+) Daptonema normandicum (+) |

The SIMPER results are provided in Table 3. The main difference between the untreated control nematofauna and the azithromycin treatments was due mainly to an increase in the proportion of two species, namely M. pristiurus and S. edax. Both levels of azithromycin considered were followed by the decline or disappearance of three species: C. germanica, Trichotheristus mirabilis and Longicyatholaimus longicaudatus. Instead, the species Enoplolaimus longicaudatus showed higher relative abundance in the sediments enriched with P. oceanica compared to untreated control sediment. This was also associated with a reduction in the relative abundance of three other species: Microlaimus honestus, Bathylaimus tenuicaudatus, and Cyartonema germanica.

A restructure of the nematode communities was noticed in the microcosms treated with different mixtures of P. oceanica and azithromycin, reflecting numerous consecutive changes (Table 3). In the microcosms treated with P2A1, an increase in the abundance of M. pristiurus and E. longicaudatus was observed, whereas in P2A2, the relative abundance of M. pristiurus, Halalaimus gracilis, and Marylynnia steckoveni increased. The difference among the untreated control assemblage and the mixtures P1A1 and P1A2 was mainly due to enhanced proportions of the following taxa: H. gracilis, M. steckoveni and/or M. punctata. Moreover, the relative abundance of three other species increased in P2A1: M. pristiurus, E. longicaudatus, and L. longicaudatus.

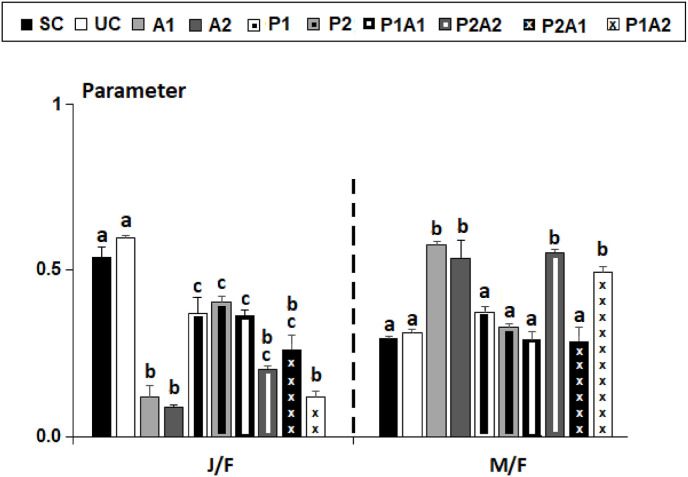

3.4. Demographic traits

At the end of this experiment, it was found that the highest values for the sex-ratio M/F characterized azithromycin treatments (A1 and A2), P2A2, and P1A2, and the lowest ones of J/F in treatments A1, A2, and P1A2 (Fig. 5 ). These results were confirmed statistically based on separate chi-square randomization tests outcomes (√-transformed data: p < 0.05, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Values of demographic Ratios (J/F and M/F) of the nematofauna in the control microcosms with (SC) or without acetonitrile (UC) used as a solvent of azithromycin and those enriched with azithromycin (A1 and A2), leaves of Posidonia oceanica (P1 and P2), and their mixtures (P1A1, P2A2, P1A2 and P2A1). Juveniles (J); Females (F); Males (M). Vertical bars replace standard Deviations. Different letters above bars correspond to significant difference (p < 0.05) based on Chi-Square test outcomes (√-transformed data in %).

3.5. Toxicokinetic findings

The toxicokinetic data of azithromycin are shown by Table 4 . These data are commonly used in toxicokinetic approaches. The physicochemical parametes and bioavalability scores, as shown by Fig. 6 A exhibited that azithromycin had acceptable bioavalability, which indicates the physiological activity of the antibiotic with possible toxic outcomes. Azithromycin was also associated with low gastro-intestinal (GI) absorption and blood-brain-barrier (BBB) permeation (Fig. 6B). While azithromycin inhibited none of the major cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms (CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4), it was expected to behave as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate. Thus, it could be deduced that azithromycin may disrupt the distribution but not the metabolism and elimination. Log Kp calculation, as assessed using both lipophilicity and molecular weight, resulted in low skin permeability.

Table 4.

Physicochemical properties, toxicokinetics and toxicity prediction of azithromycin.

| Physicochemical properties | |

| Molecular weight (g × mol−1) | 748.98 |

| Num. heavy atoms | 52 |

| Num. arom. heavy atoms | 0 |

| Fraction Csp3 | 0.97 |

| Num. rotatable bonds | 7 |

| Num. H-bond acceptors | 14 |

| Num. H-bond donors | 5 |

| Molar Refractivity | 200.78 |

| TPSA (Å2) | 180.08 |

| Water solubility/Lipophilicity | |

| Log S (ESOL) | −6.55 |

| Log S (Ali) | −7.50 |

| Log S (SILICOS-IT) | −2.22 |

| Consensus Log Po/w | 2.02 |

| Oral toxicity and toxicokinetics | |

| GI absorption | Low |

| BBB permeant | No |

| P-gp substrate | Yes |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No |

| Log Kp (cm/s) | −8.01 |

Fig. 6.

Bioavailability hexagon of azithromycin based on its physico-chemical parameters (A). The boiled-egg model of azithromycin (B). Molecular size (SIZE), polarity (POLA), insolubility (INSO), insaturation (INSA). Flexibility (FLEX), lipophiliciy (LIPO).

4. Discussion

The current work had two main objectives: first, to test if excessive azithromycin concentrations in aquatic environment, an antibiotic widely used during the past three as anti-COVID-19 treatment in coutries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, was toxic for free-living nematodes, and (2) to test the interactions between azithromycin and debris of P. oceanica, a very abundant macrophyte in the Mediterranea Sea, on nematofauna.

The results obtained from this work therefore made it possible to provide answers to the following questions: (1) will the Mediterranean coastal infralitoral zones with high densities of P. oceanica become more vulnerable to azithromycin? Such question is in our opinion relevant, given that several Mediterranean countries such as Italy, France and Spain were among the epicenters of COVID-19 and (2) could P. oceanica play a key-role as remediator in the marine habitats affected by azithromycin?

To give answers to the questions above, the stating nematofauna must be collected from a metallically pristine location since several published works confirmed that metals may influence the reactivity of azithromycin (Dash and Shahidul Islam, 2020). Such criteria were filled based on results given in Table 1. The concentrations measured were lower than the Threshold Effects Eevel of NOAA (1999) for marine sediment, and were very close to those found previously by Hedfi et al. (2013) in the same location.

During the current study, just the microcosms contaminated with azithromycin (A1 and A2) and P1A2 had lower diversity compared to control replicates (UC). Thus, we can assume that the azithromycin is associated with certain toxic effects for meiobenthic nematodes, as was previously proved for other antibiotics, such as penicillin G (Nasri et al., 2015a; b) and ciprofloxacin (Nasri et al., 2020a; b). The negative intercations between this antibiotic and nematodes are explicable by direct contact, through the ingestion of contaminated sediment or internalization through cuticular pores, as well and indirectly, by eliminating bacteria and affecting the microvore nematodes. In P1A2 treatment, the highest concentration in azithromycins (A2), which proved to be harmful for the nematofauna, was not attenuated by the lowest mass of P. oceanica (P1). Both quantities of this macrophyte, P1 and P2, had no significant effect on the nematode diversity (Fig. 3). Similar negative effects induced by this antibiotic were also found for fish. Fairgrieve et al. (2005) evaluated the toxic effects of azithromycin in fish. The authors showed that the Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) exposed orally to azithromycin showed histopathologic lesions on gills, head and trunk, but also on the kidney, liver, raft, heart, pyloric channel, upper intestine, gonade, gonade, gonade, gonade, gonade, gonade, gonade, and brain. Moreira Mendonça-Gomes et al. (2021) also assessed the toxicity of azithromycin, alone and in combination with a second COVID-19 drug, hydroxychloroquine, using as experimental model the zebrafish (Danio rerio). The authors observed neurotoxic effects induced by azithromycin, alone and combined with hydroxychloroquine, associated with several physiological and biochemical disruptions.

The nematode species showed different responses to the treatments. The most vulnerable taxa to azithromycin used alone and combined with P. oceania were the microvores and the consumers of diatoms. It can be deduced from this that the azithromycin targeted benthic bacteria through its antibiotic properties and the bacteriophagous nematodes were therefore faced with lower nutritional resources, diminishing their densities. Similarly, the imbalanced microbial consortium from sediment seems to have affected the densities of nematodes of type 2 A. Several previous studies have supported the concept of indigenous consortium ‘microalgues-bacteria’ (Tang et al., 2010; Mahdavi et al., 2015). More recently, it has also proved that bacteria are associated with microalgae in the phycosphere (Amin et al., 2012, 2015; Bagatini et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2017, 2018). In parallel to this, we also suspect that following their exposure to azithromycin, the non-selective deposit feeders were affected by their caudal forms. The nematodes appurtenant to this feeding group that have clavate or round tails are disadvantaged compared to those with conical tails, which are better adapted to locomotion in habitats impacted by azithromycin during the search for micro-shelters, food and sexual partners. We also suggest that the fine sediment displacement with conical tails is more efficient, through saltory movements, compared to other types of tails. This potential explanation was reinforced by the dominance in the sediments spiked with azithromycin of omnivore-carnivores, which also posessed conical tails, namely the males of S. edax and M. pristiurus. In the sediments enriched with debris of the macrophyte P. oceanica, the substrate is coarser and more porous compared to fine sediments microhabitats. This may explain the dominance of nematodes that posessed elongated tails, as was the case for the predator nematode Enoplolaimus longicaudatus. The tolerance of omnivores-carnovores to azithromycin could be related to their sturdy body type and broad trophic spectrum (Allouche et al., 2020, 2021).

The distribution of nematodes in the ordinal plan of the nMDS plot (Fig. 4) exposure to the mixtures of treatments is explained below according to the SIMPER analysis outcomes (Table 3).

-

-

The nematode assemblage from P2A1, which had a similar taxonomic and relative abundance composition with the controls SC and UC. Despite this overall similarity, a certain toxicity was visible in treatment A1, leading to lower abundance of the tolerant species M. honestus compared to control treatment UC, whereas the sensitive species L. longicaudatus, which is rather sensitive, had a better representation.

-

-

The nematode assemblages from P1A1 and P2A2 comprised higher relative abundances of microvores (i.e. H. gracilis) and diatoms consumers (i.e. M. steckhoveni) with effiliated tails. Instead, the members of these two trophic guilds which posessed short tails were disadvantaged, along with the non-selective deposit feeders with clavate tails. It emerges that the pattern described above in the absence of P. oceanica (i.e. the exposure to azithromycin to favor of conical tails species) was not supported. It could be thus assumed that the toxic effect of azithromycin was buffered by the presence of the vegetal debris. This antibiotic could have been wrapped on this macrophyte remains such as to form larger particles, leading instead to a more porous microenviroment that favoured free-swimming taxa with effiliated tails.

-

-

The nematode assemblage from P1A2 presented certain similarities to P1A1 and P2A2, by showing a reduction in the proportions of microvores and diatoms consumers, with short tails and of non-selective deposit feeders with clavate tails, but beneficial for microvores (i.e. H. gracilis) and diatom consumers (i.e., M. steckhoveni and M. puncticaudata) with effiliated tails. We would also like to emphasise the proliferation within this community of certain tolerant species to azithromycin and with conical tails: V. maior, a non-selective deposit feeder and of Synonchiella edax, an omnivore-carnivore.

The communities from SC and UC controls were similar in terms of abundance and taxonomic diversity, indicating that the solvent used in the current study (acetonitrile 0.01 M) had no harmful effects on the nematode assemblages. The SIMER analysis revealed that the lowest average dissimilarity in this experiment was between control treatments SC and UC (18.91%), with no significant ANOSIM analysis outcome (R = 0.296; p = 0.07).

At the end of this experiment, it was found that the highest values for the sex-ratio M/F characterized azithromycin treatments (A1 and A2), P2A2, and P1A2, and the lowest ones of J/F in treatments A1, A2, and P1A2 (Fig. 5). These results were confirmed statistically based on separate chi-square randomization tests outcomes (Fig. 5).

Based on changes in J/F ratio, a significant decrease in nematode fertility could be possible under both azithromycin treatments A1 and A2, and also after ewposure to A2 mixed with P. oceanica fibers (P1A2). This finding was probably associated to a discernible masculinization since the sex-ratio M/F showed its highest values at treatments A1, A2, P1A2, and P2A2.

The toxicokinetic study of azithromycin may explain the demographic traits and taxonomic diversity findings. In fact, exposure to azithromycin was associated with acceptable bioavalability, low GI absorption, skin permeability and BBB permeation. Its major toxic outcomes may be related to being a P-gp substrate, hence, disruption of drugs distribution as previously reported in several pharmaco- and toxico-kinetic studies [A,B,C,D].

5. Conclusions

The current experiment showed that the azithromycin had harmful effects on nematodes, by decreasing significantly their overall density and leading to the disappearance of the most vulnerable taxa, when present in the highest concentration A2: C. germanicum, D. trabeculosum and L. longicaudatus. This was confirmed by the bioavailability and the toxicokinetic attributes. Other species proved to be tolerant to azythromycin, such as M. pristurus, S. edax, V. maior, and D. normandicum. Instead, the presence of the macrophyte P. oceanica did not have any meaningful impact on the diversity of nematodes. However, the presence of this macrophyte was beneficial for nematodes with effiliated tails as a result of a more porous microenvironment.

Based on the results of the current study, the toxicity of the antibiotic azithromycin followed a decrease P2A1 < P1A1/P2A2 < P1A2. The presence of the macrophyte P. oceanica seems to have reduced the toxicity of azithromycin, mainly when present in the highest concentration. At concentrations of 5 μg l−1 (A1) the toxicity of azithromycin was potentially buffered by 10% DW of Posidonia (P1) and entirely by 20% DW (P2). Therefore, the mass of P. oceanica that proved to be effective in neutralizing 5 μg l−1 of azithromycin is between 10 and 20% DW. In P2A2 two nematodes thrived and were considered as tolerant species to azithromycin: V. maior and S. edax.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Octavian Pacioglu was funded by the projects National Core Program—Romanian Ministry of Research and Innovation, Romania, Project 25N/2019 BIODIVERS 19270103 and by a grant from the Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research and Innovation (UEFISCDI), Romania, Project Number PN-III-P1-1.1-TE-2021-0221.

Handling Editor: Maria Cristina Fossi

Footnotes

This paper has been recommended for acceptance by Maria Cristina Fossi.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Algros E. vol. 1. Faculté de Pharmacie. Henri Poincaré Universitu - Nancy; France: 2018. p. 107pp. (Antibiotiques dans l’environnement: sources, concentrations, persistance, effets et risques potentiels). [Google Scholar]

- Allouche M., Ishak S., Ben Ali M., Hedfi A., Almalki M., Karachle P.K., Harrath A.H., Abu-Zied R.H., Badraoui R., Boufahja F. Molecular interactions of polyvinyl chloride microplastics and beta-blockers (diltiazem and bisoprolol) and their effects on marine meiofauna: combined in vivo and modeling study. J. Hazard Mater. 2022;431 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allouche M., Nasri A., Harrath A.H., Mansour L., Alwasel S., Beyrem H., Bourioug M., Geret F., Boufahja F. New protocols for the selection and rearing of Metoncholaimus pristiurus and the first evaluation of oxidative stress biomarkers in meiobenthic nematodes. Environ. Pollut. 2020;263 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allouche M., Nasri A., Harrath A.H., Mansour L., Alwasel S., Beyrem H., Plăvan G., Rohal-Lupher M., Boufahja F. Meiobenthic nematode Oncholaimus campylocercoides as a model in laboratory studies: selection, culture, and fluorescence microscopy after exposure to phenanthrene and chrysene. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28:29484–29497. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-12688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral D.F., Montalvão M.F., de Oliveira Mendes B., da Costa Araújo A.P., de Lima Rodrigues A.S., Malafaia G. Sub-lethal effects induced by a mixture of different pharmaceutical drugs in predicted environmentally relevant concentrations on Lithobates catesbeianus (Shaw, 1802) (Anura, ranidae) tadpoles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26(1):600–616. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3656-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin S.A., Hmelo L.R., van Tol H.M., Durham B.P., Carlson L.T., Heal K.R., Morales R.L., Berthiaume C.T., Parker M.S., Djunaedi B., Ingalls A.E., Parsek M.R., Moran M.A., Armbrust E.V. Interaction and signalling between a cosmopolitan phytoplank-ton and associated bacteria. Nature. 2015;522:98–101. doi: 10.1038/nature14488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin S.A., Parker M.S., Ambrust E.V. Interactions between diatoms and bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012;76:667–684. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenteros M., Ruiz Abierno A., Fernandez-Garces R., Perez-Garcia J.A., Díaz-Asencio L., Vincx M., Decraemer W. Biodiversity patterns of free-living marine nematodes in a tropical bay. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 2009;85:179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Austen M.C., McEvoy A.J., Warwick R.M. The specificity of meiobenthic community responses to different pollutants: results from microcosm experiments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1994;28:557–563. [Google Scholar]

- Badraoui R., Saeed M., Bouali N., Hamadou W.S., Elkahoui S., Alam M.J., Siddiqui A.J., Adnan M., Saoudi M., Rebai T. Expression profiling of selected immune genes and trabecular microarchitecture in breast cancer skeletal metastases model: effect of α–tocopherol acetate supplementation. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2022;110:475–488. doi: 10.1007/s00223-021-00931-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagatini I.L., Eiler A., Bertilsson S., Klaveness D., Tessarolli L.P., Vieira A.A.H. Host-specificity and dynamics in bacterial communities associated with bloom-forming freshwater phytoplankton. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Garali A., Ouakad M., Gueddari M. Dynamique sédimentaire au niveau de la frange littorale est de Bizerte (nord-est de la Tunisie) Afr. Geosci. Rev. 2008;15(4):337–351. [Google Scholar]

- Beyrem H., Aïssa P. Les nématodes libres, organismes-sentinelles de l’évolution des concentrations d’hydrocarbures dans la baie de Bizerte (Tunisie) Cah. Biol. Mar. 2000;41:329–342. [Google Scholar]

- Beyrem H., Mahmoudi E., Essid N., Hedfi A., Boufahja F., Aïssa P. Individual and combined effects of cadmium and diesel on a nematode community in a laboratory microcosm experiment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2007;68:412–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boufahja F., Semprucci F. Stress-induced selection of a single species from an entire meiobenthic nematode assemblage: is it possible using iron enrichment and does pre-exposure affect the ease of the process? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015;22:1979–1998. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boufahja F., Semprucci F., Beyrem H. An experimental protocol to select nematode species from an entire community using progressive sedimentary enrichment. Ecol. Indicat. 2016;60:292–309. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan J.B. In: Methods for the Study of Marine Benthos.International Biological Programme Handbook No. 16. Holme N.A., McIntyre A.D., editors. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Oxford: 1971. Measurement of the physical and chemical environment: Sediments; p. 334. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. J. Ecol. 1993;18:117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K.R., Gorley R.N. PRIMER-E; Plymouth,UK: 2001. PRIMER V5: User Manual/tutorial; p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K.R., Warwick R.M. second ed. PRIMER-E; Plymouth, United Kingdom: 2001. Changes in Marine Communities: an Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation. [Google Scholar]

- Coull B.C., Chandler G.T. Pollution and meiofauna: field, laboratory and mesocosm studies. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. 1992;30:191–271. [Google Scholar]

- Dash S., Shahidul Islam M.D. Azithromycin and metals complex interaction: a systemic review on drug-metals interaction. Acta. Sci. Pharm. 2020;1(12):3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Essid N., Allouche M., Lazzem M., Harrath A.H., Mansour L., Alwasel S., Mahmoudi E., Beyrem H., Boufahja F. Ecotoxic response of nematodes to ivermectin, a potential anti-COVID-19 drug treatment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020;157 doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiano M., Danovaro R. Composition of organic matter in sediment facing a river estuary (Tyrrhenian Sea): relationships with bacteria and microphytobenthic biomass. Hydrobiologia. 1994;277:71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fairgrieve W.T., Masada C.L., McAuley W.C., Peterson M.E., Myers M.S., Strom M.S. Accumulation and clearance of orally administered erythromycin and its derivative, azithromycin, in juvenile fall Chinook salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2005;64(2):99–106. doi: 10.3354/dao064099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes M.J., Paíga P., Silva A., Llaguno C.P., Carvalho M., Vázquez F.M., Delerue-Matos C. Antibiotics and antidepressants occurrence in surface waters and sediments collected in the north of Portugal. Chemosphere. 2020;239 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodsell P.J., Underwood A.J., Chapman M.G. Evidence necessary for taxa to be reliable indicators of environmental conditions or impacts. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009;58:323–331. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotelli N.J., Entsminger G.L. Acquired Intelligence Inc, & Kesey-Bear; 2005. Ecosim: Null Models Software for Ecology. Version 7.72. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Somerfield P.J., Warwick R.M., Zhang Z. Large-scale patterns in the community structure and biodiversity of free living nematodes in the Bohai Sea China. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. 2001;81:755–763. [Google Scholar]

- Hedfi A., Ben Ali M., Hassan M.M., Albogami B., Al-Zahrani S.S., Mahmoudi E., Karachle P.K., Rohal-Lupher M., Boufahja F. Nematode traits after separate and simultaneous exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (anthracene, pyrene and benzo[a]pyrene) in closed and open microcosms. Environ. Pollut. 2021;276 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedfi A., Boufahja F., Ben Ali M., Aïssa P., Mahmoudi E., Beyrem H. Do trace metals (chromium, copper and nickel) influence toxicity of diesel fuel for free-living marine nematodes? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013;20(6):3760–3770. doi: 10.1007/s11356-012-1305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotta J., Boucher G. Interregional variation of free-living nematode assemblages in tropical coral sands. Cah. Biol. Mar. 2001;42:315–326. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi H., Prasad V., Liu Y., Ulrich A. In situ biodegradation of naphthenic acids in oil sands tailings pond water using indigenous algae–bacteria consortium. Bioresour. Technol. 2015;187:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi E., Essid N., Beyrem H., Hedfi A., Boufahja F., Vitiello P., Aïssa P. Effects of hydrocarbon contamination on a free-living marine nematode community: results from microcosm experiments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005;50:1197–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi E., Essid E., Beyrem H., Hedfi A., Boufahja F., Vitiello P., Aïssa P. Individual and combined effects of lead and zinc of a free-living marine nematode community: results from microcosm experiments. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2007;343:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça-Gomes J.M., da Costa Araujo A.P., da Luz T.M., Charlie-Silva I., Bezerra Braz H.L., Bezerra Jorge R.J., Ibrahim Ahmed M.A., Nobrega R.H., Vogel C.F.A., Malafaia G. Environmental impacts of COVID-19 treatment/Toxicological evaluation of azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine in adult zebrafish. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;790 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Minguez L., Pedelucq J., Farcy E., Ballandonne C., Budzinski H., Halm-Lemeille M.-P. Toxicities of 48 pharmaceuticals and their freshwater and marine environmental assessment in northwestern France. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016;23(6):4992–5001. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-3662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens T., Vincx M. Observations on the feeding ecology of estuarine nematodes. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1997;77:211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Nasri A., Allouche M., Hannachi A., Barkaoui T., Barhoumi B., Saidi I., D'Agostino F., Mahmoudi E., Beyrem H., Boufahja F. Nematodes trophic groups changing via reducing of bacterial population density after sediment enrichment to ciprofloxacin antibiotic: case study of Marine Mediterranean community. Aquat. Toxicol. 2020;228 doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2020.105632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasri A., Boufahja F., Hedfi A., Mahmoudi E., Aïssa P., Essid N. Impact of penicillin G on the trophic diversity (Moens & Vincx, 1997) of marine nematode community: results from microcosm experiments. Cah. Biol. Mar. 2015;56(1):65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nasri A., Hannachi A., Allouche M., Barhoumi B., Saidi I., Dallali M., Harrath A.H., Mansour L., Mahmoudi E., Beyrem H., Boufahja F. Chronic ecotoxicity of ciprofloxacin exposure on taxonomic diversity of a meiobenthic nematode community in microcosm experiments. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020;32:1470–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Nasri A., Jouili S., Boufahja F., Hedfi A., Mahmoudi E., Aïssa P., Essid N., Beyrem H. Effects of increasing levels of pharmaceutical penicillin G contamination on structure of free living nematode communitiesin experimental microcosms. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015;40:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemys, editor. Nemys: World Database of Nematodes. 2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NOAA . Coastal protection & restoration division. NOAA; USA: 1999. Screening Quick Reference Tables (SQuiRTs) [Google Scholar]

- Platt H.M., Warwick R.M. Part I. British Enoplids Synopses of the British Fauna No 28. Cambridge University Press; 1983. Free living marine nematodes; p. 314. [Google Scholar]

- Platt H.M., Warwick R.M. Part II. British Chromadorids Synopses of the British Fauna No 38. E. J. Brill; Leiden: 1988. Free living marine nematodes; p. 502. [Google Scholar]

- Poupaert J.H., Aguida B., Hountondji C. Study of the interaction of zinc cation with azithromycin and its significance in the COVID-19 treatment: a molecular approach. Open Biochem. J. 2020;14(1):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Selamoglu M. Blue economy and blue ocean strategy. J. Ecol. Nat. Resour. 2021;5(4) [Google Scholar]

- Selamoglu M. Importance of the cold chain logistics in the marketing process of aquatic products: an update study. Surv. Fish. Sci. 2021;8(1):25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Schratzberger M., Warwick R.M. Differential effects of various types of disturbances on the structure of nematode assemblages: an experimental approach. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999;181:227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Seinhorst J.W. A rapid method for the transfer of nematodes from fixative to anhydrous glycerine. Nematologica. 1959;4:67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Shiogiri N.S., Ikefuti C.V., Carraschi S.P., da Cruz C., Fernandes M.N. Effects of azithromycin on tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): health status evaluation using biochemical, physiological and morphological biomarkers. Aquacult. Res. 2017;48(7):3669–3683. [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., He L.Y., Tao X.Q., Dang Z., Guo C.L., Lu G.N., Yi X.Y. Construction of an artificial microalgal-bacterial consortium that efficiently degrades crude oil. J. Hazard Mater. 2010;181:1158–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telesca L., Belluscio A., Criscoli A., Ardizzone G., Apostolaki E.T., Fraschetti S., Gristina M., Knittweis L., Martin C.S., Pergent G., Alagna A., Badalamenti F., Garofalo G., Gerakaris V., Pace M.L., Pergent-Martini C., Salomidi M. Seagrass meadows (Posidonia oceanica) distribution and trajectories of change. Sci. Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep12505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H., Angelova A., Bowler B., Jones M., Gutierrez T. Enhanced crude oil biodegradation potential of natural phytoplankton-associated hydro-carbonoclastic bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;19:2843–2861. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H.F., Lesaulnier C., Pelikanb C., Gutierrez T. Visualisation of the obligate hydrocarbonoclastic bacteria Polycyclovorans algicola and Algiphilus aromaticivorans in co-cultures with micro-algae by CARD-FISH. Microbiol. Meth. 2018;152:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello P., Dinet A. Définition et échantillonnage du méiobenthos. Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer Médit. 1979;25:279–283. [Google Scholar]

- Wakkaf T., Allouche M., Harrath A.H., Mansour L., Alwasel S., Ansari K.G.M.T., Beyrem H., Sellami B., Boufahja F. The individual and combined effects of cadmium, Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) microplastics and their polyalkylamines modified forms on meiobenthic features in a microcosm. Environ. Pollut. 2020;266 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwick R.M., Platt H.M., Somerfield P.J. Part III. British Monohysterids Synopsis of British Fauna (New Series) No 53. Field. Council; Studies: 1998. Free-living marine nematodes. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick R.M., Price R. Ecological and metabolic studies on free-living nematodes from an estuarine sand flat. Estuar. Coast Mar. Sci. 1979;9:257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth J. COVID-19: a fast evolving pandemic. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020;114(4):241–248. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/traa025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M., Hamdi H., Abdulnasser I., Jedidi N. In: Study on Environmental Pollution of Bizerte Lagoon. Ghrabi A., Yoshida M., editors. INRST-JICA Publishers; Tunis: 2004. Contamination of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in Bizerte lagoon bottom sediments, surface sediment and sediment repository; pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.