Abstract

Lemmel syndrome is a rare clinical entity characterized by the presence of a periampullary duodenal diverticulum resulting in compression and dilatation of the pancreatic and common bile ducts, accompanied by obstructive jaundice. Gastric outlet obstruction is not a known complication of this syndrome, and there are no standardized approaches to its treatment. We present the first case of Lemmel syndrome presenting as gastric outlet obstruction and provide the results of a systematic literature review.

Keywords: Case report, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Lemmel syndrome, Obstructive jaundice, Pancreas, Periampullary diverticulum

Introduction

Diverticula, defined as outpouchings of the bowel wall, are common throughout the small and large intestine and are usually asymptomatic [1]. The most common site of diverticulosis is the colon, the second being the duodenum with a reported prevalence of 23% [2–4]. Duodenal diverticula usually involve the mucosal layer and occur most frequently within the second portion of the duodenum [5]. Given that duodenal diverticula are largely asymptomatic, they are commonly diagnosed as an incidental finding that does not require intervention [4]. However, in rare instances, duodenal diverticula arising 2–3 cm from the ampulla of Vater (“periampullary duodenal diverticula”) may lead to compression and result in dilatation of the biliary and pancreatic ducts, causing clinical symptoms in approximately 5% of cases [2, 6].

An extremely rare clinical entity involving periampullary diverticula is Lemmel syndrome, described by Dr. Gerhard Lemmel in 1934 as a periampullary duodenal diverticulum compressing the pancreatic and common bile ducts and resulting in obstructive jaundice. Depending on the location of the major duodenal papilla relative to the diverticulum, it can be characterized into 3 separate types: within the diverticulum (type I), within the margin of the diverticulum (type II), or near the diverticulum (type III) [7]. Since this description, nearly 100 years ago, there have only been a handful of reported cases of Lemmel syndrome, each with varying presentations and treatment courses. Because of the variability in presentation, there are no standardized approaches to its diagnosis or treatment. In this manuscript, we report an interesting case of Lemmel syndrome and perform a literature review involving 17 cases of Lemmel syndrome to delineate approaches to the diagnosis and management of this rare condition.

Case Report

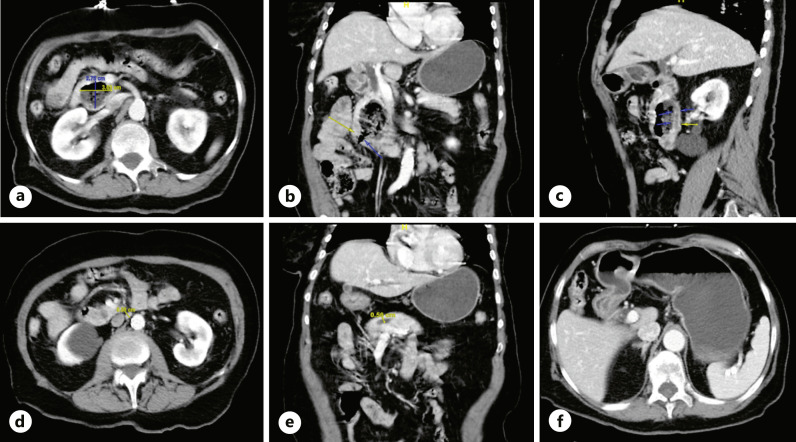

An 82-year-old woman presented with acute abdominal pain and non-bloody, non-bilious emesis. On arrival, she was hemodynamically stable. She was oriented only to person, but the remainder of her exam was normal. Laboratory testing was within normal limits, including total bilirubin of 0.6 mg/dL (normal range <1.2) and direct bilirubin of 0.1 mg/dL (normal range <0.2). Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast revealed a 2.7 × 3.7 × 5.2 cm complex pancreatic head lesion containing air and debris, contiguous with the duodenum at the junction of the 2nd and 3rd segments with dilatation of the common bile (1 cm) and main pancreatic duct (0.6 cm), concerning for a pancreatic mass. There was also gastric outlet obstruction (GOO), manifested as a markedly distended stomach with distal gastric and proximal duodenal wall thickening and hyperenhancement (shown in Fig. 1). She was made nil per os (NPO) and started on intravenous (IV) maintenance fluids in anticipation of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) to characterize her pancreatic mass.

Fig. 1.

CT abdomen pelvis demonstrating a 2.7 × 3.7 × 5.2 cm complex pancreatic head lesion containing air and debris (a), contiguous with the duodenum at the junction of the second and third segments (b) with moderate 1.0 cm dilatation of the common bile duct (c) and 0.6 cm dilatation of the main pancreatic duct (d, e). CT abdomen pelvis demonstrating GOO manifested as markedly distended stomach with distal gastric and proximal duodenal wall thickening and hyperenhancement (f).

EUS showed normal parenchyma in the neck, body, and tail of the pancreas, as shown in Figure 2, and there was no pancreatic mass. EGD showed a large non-bleeding periampullary diverticulum, with the ampulla specifically located on the rim of the diverticulum, in the second portion of the duodenum, containing a large amount of food debris that was obstructing the common bile and main pancreatic ducts, causing ductal dilatation, consistent with Lemmel syndrome type II, as shown in Figure 3. Endoscopic diverticular lavage with the removal of food debris was performed. Her diet was quickly escalated, her symptoms resolved, and she was discharged the following afternoon. Repeat CT scan of the abdomen 11 days post-procedure showed resolution of GOO and reduced biliary ductal dilation and diverticular size, as shown in Figure 4. At 1-month follow-up, she remained asymptomatic and was tolerating a high-fiber diet without clinical signs of GOO or biliary obstruction.

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) demonstrating common and biliary ductal dilation in the setting of an otherwise endosonographically normal pancreas.

Fig. 3.

Large non-bleeding periampullary diverticulum in the second portion of the duodenum containing a large amount of food debris prior to lavage (a), during partial clearance (b), and following complete clearance (c).

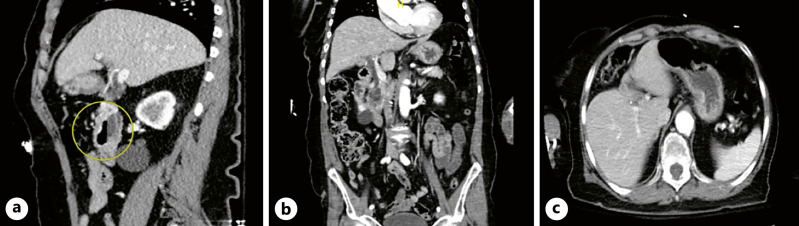

Fig. 4.

CT abdomen pelvis demonstrating improvement in common bile duct dilation (a) and diverticular size with resolution of radiographic evidence of GOO (b, c) 10 days after endoscopic diverticular lavage. Bile duct measuring 0.7 cm, previously 1.0 cm. Diverticular dimensions measuring 1.9 × 3.6 × 3.7 cm (AP by transverse by craniocaudal), previously 2.7 × 3.7 × 5.2 cm. Pancreatic duct not visualized well likely due to resolution of dilation following removal of diverticular contents.

Methods

The consensus-based clinical case reporting (CARE) checklist was completed by the authors for the case report presented and is attached as supplementary material. A PubMed search was performed to identify previous cases of Lemmel syndrome using the search terms “Lemmel” or “Lemmel’s” or “Lemmel’s syndrome” or “Lemmel syndrome.” PubMed was utilized to ensure all published case reports were peer-reviewed and available for viewing at no cost. All available reports prior to May 2021 were identified and reviewed. Cases that met the inclusion criteria (radiographic evidence of periampullary diverticulum causing pancreaticobiliary ductal dilatation and completed manuscripts published in English) were included. Data on age, sex, report date, existing comorbidities, symptoms, exam findings, laboratory studies, imaging studies, treatment modalities, and outcomes were collected and analyzed. The distribution of normality was evaluated for continuous variables, and parametric or non-parametric tests were chosen as appropriate. Wilcoxon rank-sum test or t test for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables were used to analyze differences between two groups. More than two groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis test. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 28, IBM SPSS Statistics). All statistical tests were two-sided, and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

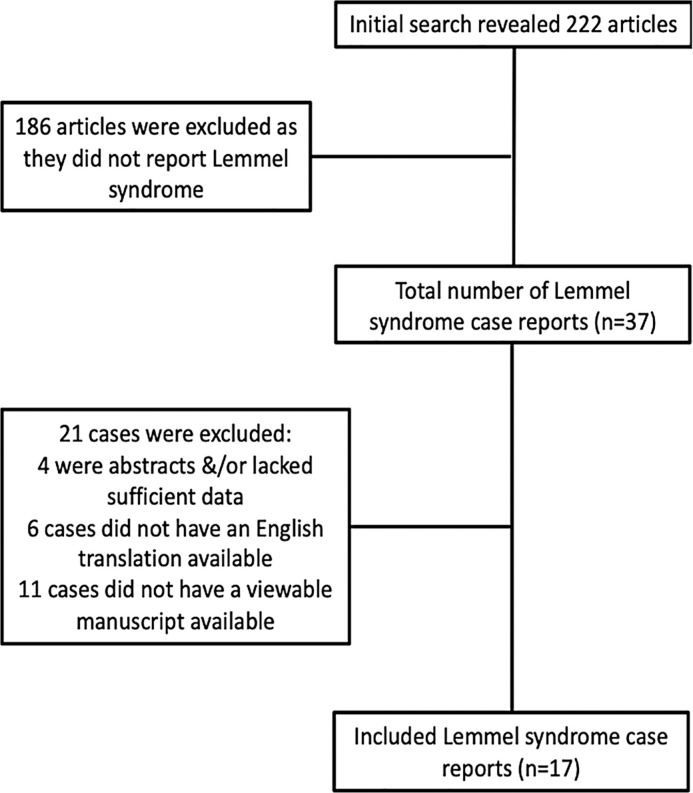

Utilizing the literature search terms as described above, 222 articles were reviewed (shown in Fig. 5). A total of 186 articles were excluded as they did not report Lemmel syndrome. Of the 37 articles that remained, 21 cases were excluded: 4 cases were abstracts without completed manuscripts; 6 cases were not available in English, and 11 cases were not associated with a viewable manuscript. Ultimately, 16 cases were identified satisfying our PubMed search criteria. With the addition of our case, the sample size reached 17 subjects. Table 1 summarizes demographic and clinical data of reported cases. The mean age of subjects was 70 ± 19.2 years old, with a range of 24 years old to 91 years old. Ten of the seventeen subjects (58.8%) were female.

Fig. 5.

Flow diagram of the literature search.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of previously reported Lemmel syndrome cases

| Author | Age, years | Gender | Comorbidities/medical history | Presenting complaint | Pertinent vital signs | Exam findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Love et al. (2021) [23] | 82 | F | Breast cancer s/p treatment, dementia, DM, HTN | 2 days; diffuse abdominal pain | Within normal limits | Anicteric Benign exam |

| Bellamlih et al. (2021) [11] | 77 | F | N/A | 4 weeks; general deterioration, RUQ pain, fever | 38.9°C | Scleral icterus, RUQ tenderness |

| Bernshteyn et al. (2020) [6] | 57 | M | DM2, GERD, psoriasis, cholecystectomy | 5 days; RUQ pain, fever, elevated LFTs | 38.9°C 114 HR |

RUQ pain Jaundice not mentioned |

| Yanagaki et al. (2020) [8] | 81 | F | Previously healthy | General deterioration, RUQ pain, fever. Timeframe not specified |

38.8°C | Anicteric Benign exam |

| Alzerwi (2020) [19] | 24 | F | Previously healthy | 6 months; epigastric pain, fever, anorexia, pale stool, dark urine | 38.7°C 117 HR |

Scleral icterus Tender epigastrium |

| Tabata et al. (2019) [22] | 91 | F | HTN, CAD | Painless jaundice. Timeframe not specified |

Within normal limits | Jaundiced |

| Frauenfeld et al. (2019) [20] case 1 | 79 | M | N/A | 2 weeks; abdominal pain, fever, jaundice | Febrile (not specified) | Jaundiced |

| Frauenfeld et al. (2019) [20] case 2 | 70 | F | N/A | Nausea, vomiting, slight jaundice. Timeframe not specified | Not available | Jaundiced |

| Venkatana et al. (2019) [18] | 70 | M | Remove cholecystectomy, Billroth II | Fever, chills/rigors, RUQ pain. Timeframe not specified | Febrile (not specified) | Jaundice, RUQ tenderness |

| Oliveira et al. (2019) [17] | 89 | M | Dementia, osteoarthritis | 1 month; fever, chills, RUQ pain | 38.9°C | Scleral icterus, RUQ tenderness |

| Tobin et al. (2018) [10] | 80 | F | N/A | 6 weeks; general deterioration | Not mentioned | Anicteric Benign exam |

| Miyajima et al. (2018) [16] | 80 | F | HCC, cholangiocarcinoma, DM, pulmonary fibrosis | 5 days; fever | 38°C 102 HR |

Scleral icterus |

| Desai et al. (2017) [5] | 25 | F | Previously healthy | 3 months; 30-lb weight loss, fatigue, weakness | Not mentioned | Anicteric Benign exam |

| Khan BA et al. (2017) [9] | 69 | M | N/A | Acute pancreatitis | Not mentioned | Epigastric pain, jaundiced |

| Somani and Sharma (2017) [15] | 78 | M | N/A | Scleral icterus | Not mentioned | Scleral icterus |

| Rouet et al. (2012) [21] | 70 | M | Remote cholecystectomy | 2 weeks; abdominal pain, fever, jaundice | N/A | Jaundiced |

| Kang HS et al. (2014) [2] | 81 | F | PUD s/p subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis | 4 days; nausea, vomiting, fever, diffuse abdominal pain | 38.4°C | Jaundiced, RUQ tenderness |

PUD, peptic ulcer disease; s/p, status post; DM, diabetes mellitus; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HTN, hypertension; HR, heart rate; RUQ, right upper quadrant.

Abdominal pain was the most common presenting symptom, present in 64.7% of cases (11/17), followed by fever in 52.9% of cases (9/17). In 41.2% (7/17) of cases, information on vital signs was not included. Outcomes were reported in 15 cases. There were no deaths related to Lemmel syndrome.

Physical exam findings were documented in 94.1% (16/17) of cases. Four subjects (25%) had completely normal exams. Abdominal tenderness was present in 43.8% (7/16) of cases and was localized to the RUQ 71.4% (5/7) of the time among these patients. Signs of biliary obstruction were present in 43.8% (7/16) of cases. Jaundice was reported in 68.8% (11/16) of cases. Laboratory data was recorded in all cases. Elevation in serum total bilirubin was the most common lab abnormality among patients (5.9 ± 7.0 mg/dL) and was present in 81.3% (13/16) of cases. Elevations in liver enzymes were the second most common lab abnormality, present in 68.9% (11/16) of cases [aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 175.8 ± 97.8 U/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 234.4 ± 211.5 U/L; alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 596.5 ± 394.5 U/L; gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) 618.2 ± 556.1 U/L]. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated in 46.7% (8/16) of cases (32.0 ± 46.3 mg/dL), and in one case, there were no lab abnormalities.

Diagnostic and treatment modalities implemented are summarized in Table 2. Approximately half of cases (52.3%; 9/17) utilized abdominal US, 94.1% (16/17) of cases utilized CT imaging, 47.1% (8/17) of cases utilized MRI/MRCP, and 58.8% (10/17) of cases utilized direct visualization via EGD or side-viewing duodenoscope. Abdominal ultrasonography was the initial diagnostic tool in 47.1% (8/17) of cases and was abnormal in 75% (6/8). CT was the initial diagnostic tool in 47.1% (8/17) of cases and was followed by additional more definitive imaging techniques in most cases (11/17). When mentioned, common bile duct dilatation was present in 100% of cases, dilatated to an average of 12.5 mm. Pancreatic duct dilatation was mentioned in 29.4% (5/17) of cases; the degree of dilatation was not specifically recorded in most cases, and it was not mentioned in the remaining cases. EUS was utilized in 3 cases (17.6%), once to further evaluate the degree of ductal dilatation and twice to rule out periampullary neoplasm. The diagnosis was made based on CT imaging alone in only one case without further imaging or diagnostic study. Two patients (13.3%) underwent transhepatic cholangiography, one due to prior history of Billroth II gastrojejunostomy and the other due to an inability to visualize the major duodenal papilla endoscopically.

Table 2.

Diagnostic tests and treatment modalities used during management of previously reported Lemmel syndrome cases

| Author | Laboratory data | Imaging modalities | Imaging findings | Interventions and treatments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Love et al. (2021) [23] | Lactic acid 6.3, T bili 1.0, normal LFTs | CT abdomen/pelvis with contrast, EGD/EUS | CBD dilatation (10 mm), PD dilatation (6 mm), GOO | ERCP removal of food debris, endoscopic diverticular tap-water lavage |

| Bellamlih et al. (2021) [11] | T bili 6, D bili 3.7, AST 234, ALP 398, ALP 334 GGT 339, CRP 40.7 | Abdominal US, CT abdomen/pelvis, MRCP, EUS | CBD dilatation (12 mm) | 14 days of IV abx |

| Bernshteyn et al. (2020) [6] | T bili 5.5, ALP 194, ALT 106, AST 260 | Abdominal US, CT abdomen/pelvis, MRI | CBD dilatation (12 mm) | IV abx, ERCP with CBD stent placement |

| Yanagaki et al. (2020) [8] | T bili 1.0, WBC 27K, AST 337, ALT 143, amylase 110, CRP 8.87 | CT abdomen/pelvis without contrast, CT abdomen/pelvis with contrast, MRCP | CBD dilatation (exact size not mentioned) | 12 days of IV abx, ERCP (for visualization), surgery (extrahepatic bile duct resection with cholecystectomy, hepaticojejunostomy, and diverticulectomy and papilloplasty) |

| Alzerwi, (2020) [19] | T bili 114, D bili 98, ALP 1058, AST 89, ALT 41, amylase 58, WBC 20.6, PLT 510 | KUB, abdominal ultrasound, CT abdomen/pelvis, MRCP | CBD dilatation (22 mm), PC dilatation (4.8 mm) | IV abx, ERCP (aborted), percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and biliary drainage, surgery (sphincterotomy, ampullectomy, cholecystectomy, duodenotomy) |

| Tabata et al. (2019) [22] | T bili 3.7, AST 263, ALT 293, GGT 265, ALP 1181, CRP 6.27 | CT abdomen/pelvis | CBD dilatation (10 mm) | ERCP diverticular decompression via air suction, endoscopic sphincterotomy, IV abx |

| Frauenfeld et al. (2019) [20] case 1 | Elevated T bili (not specified) | Abdominal ultrasound (normal), CT abdomen without contrast | CBD dilatation (11 mm) | Nasogastric decompression, bowel rest |

| Frauenfeld et al. (2019) [20] case 2 | Elevated bilirubin metabolites, elevated inflammatory markers (values not specified) | Abdominal ultrasound, CT abdomen with contrast | CBD dilatation (13 mm) | 7 days of IV abx |

| Venkatana et al. (2019) [18] | T bili 3.5, alp 716, AST 88, amylase 84 (nL). CRP 133, WBC 11.69. Blood cultures + Klebsiella | CT abdomen with contrast, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (in setting of previous Billroth II) | CBD dilatation (value not mentioned) | Percutaneous transhepatic drainage and decompression |

| Oliveira et al. (2019) [17] | T bili 5.1, D bili 2.9, AST 171, ALT 243, ALP 236, GGT 374, CRP 13.2 | Abdominal ultrasound (normal), EGD, CT abdomen | CBD dilatation (7 mm) | Bowel rest, IV abx for 7 days |

| Tobin et al. (2018) [10] | T bili 27.4, ALT 741, ALP 517, GGT 426 | Abdominal ultrasound, MRCP, EGD | CBD dilatation (value not mentioned) | Not mentioned |

| Miyajima et al. (2018) [16] | T bili 6.2, AST 259, ALT 233, GGT 1734, ALP 1200, amylase 563, lipase 843, CRP 19.7, LDH 348, +E. tarda blood cultures | CT abdomen | CBD and PD dilatation (values not mentioned) | IV abx, ERCP, endoscopic papilloplasty and cannulation, endoscopic biliary drainage tube placement |

| Desai et al. (2017) [5] | All labs within normal limits | CT abdomen/pelvis with contrast | CBD dilatation (18 mm) | Bowel rest, 14 days of IV abx |

| Khan BA et al. (2017) [9] | T bili 2.9, D bili 1.4, Lipase 5,168, ALT 50, AST 59, ALP 156 | CT abdomen, MRCP | PD dilatation (value not mentioned) | IV fluids, bowel rest; eventual surgical diverticulectomy after recurrence of symptoms |

| Somani and Sharma (2017) [15] | T bili 5.5, AST 86, ALP 620 | Abdominal ultrasound, EUS | CBD dilatation (10 mm) | ERCP, endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy |

| Rouet et al. (2012) [21] | T bili 1.54 mg/dL | Abdominal ultrasound, CT abdomen | CBD and PD dilatation (values not mentioned), liver abscess | ERCP, endoscopic sphincterotomy; IV abx, percutaneous abscess drainage |

| Kang HS et al. (2014) [2] | T bili 2.37, AST 88, ALT 96, ALP 349, GGT 571, WBC 11.17, CRP 2.392 | CT abdomen, MRCP | CBD dilatation (value not mentioned) | ERCP biliary cannulation, endoscopic sphincterotomy, enterolith removal |

CT A/P, computerized tomography of abdomen and pelvis; CBD, common bile duct; PD, pancreatic duct; GOO, gastric outlet obstruction; abx, antibiotics.

Treatment and outcomes were described in 88.2% (15/17) of cases. Among these cases, there were no deaths or long-term complications related to their presenting illness. 67% of patients (10/15) were treated with IV antibiotics, and 70% (7/10) of these cases involved fever as a presenting sign; 20% (2/10) of cases were afebrile, and one case did not comment on the presence or absence of fever. Endoscopic intervention, such as diverticular lavage, pancreaticobiliary stent placement, or sphincterotomy, was performed in 46.7% (7/15) of these cases and was a successful treatment 100% of the time, defined as resolution of symptoms and radiographic or laboratory abnormalities. Few cases (20%, 3/15) were treated surgically with definitive diverticulectomy. One case was treated with nasogastric (NG) decompression and bowel rest alone. Most cases (66.7%, 10/15) were successfully treated without surgical or percutaneous intervention. In one case, symptoms recurred after an initial course of IV antibiotics and were treated with surgical diverticulectomy. There was no significant association between the presence of jaundice and whether surgical diverticulectomy was performed (χ2 = 2.885, df = 4, p = 0.577).

Discussion

Making the diagnosis of Lemmel syndrome can be challenging, as it can present clinically in a variety of non-specific ways. Lemmel syndrome can be further divided into 3 separate types depending on the location of the major duodenal papilla: within the diverticulum (type I), within the margin of the diverticulum (type II), or near the diverticulum (type III) [7]. The majority of patients present with abdominal pain, often localized to the RUQ. However, it is not uncommon for patients to present with vague, non-specific complaints or to be entirely asymptomatic at the time of presentation. Symptom onset appears to be subacute in most cases, although occasionally Lemmel syndrome may present as an acute obstruction of the biliary tree. Additionally, while classically associated with obstructive jaundice, the diagnosis is often made in the absence of jaundice [8–10]. In our unusual case, a patient presented with GOO and exhibited no clinical signs of jaundice despite radiographic evidence of biliary and pancreatic duct dilation.

Given the range of clinical presentations, the diagnosis of Lemmel syndrome is most reliably made by imaging. Cholestatic patterns on serum chemistries, including an elevated bilirubin and liver enzymes may strengthen the diagnosis, but they may also be normal despite radiographic evidence of biliary dilatation [5]. While there is no standardized approach, many modalities have been implemented in previous reports including magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), barium swallow studies, CT, endoscopy, and laparoscopic surgery. Interestingly, while abdominal ultrasonography has been commonly utilized in the initial diagnostic work-up in past reports, the diagnosis of Lemmel syndrome has never been made based on ultrasonography alone, and additional imaging has always been required. CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast appears to be a sensitive test and is most commonly performed in cases of suspected Lemmel syndrome. In one case, CT imaging alone was sufficient to make the diagnosis, appearing as an outpouching of the intestinal wall containing air, an air-fluid level, or debris [5]. Unfortunately, abdominal CT exams lack specificity, and a duodenal diverticula may be falsely interpreted as a possible pancreatic neoplasm or pseudocyst, as was the case for our patient [3, 11]. Thus, a suspected case of Lemmel syndrome seen on CT scan may require a more definitive study such as MRCP or endoscopy. Examination with a side-viewing duodenoscope allows for better visualization of periampullary duodenal diverticula and for immediate endoscopic intervention. For these reasons, ERCP has been heralded as the gold standard in previous reports [6, 12]. However, it appears that the diagnosis of Lemmel syndrome is made only approximately 50% of the time endoscopically, and the diagnosis can and has been made by MRCP and other radiographic modalities alone [5, 8, 13]. The diagnosis can also be made surgically with direct visualization of the periampullary diverticulum, but this is the last option given its invasiveness and non-inferiority to the other alternatives [8, 13].

The overwhelming majority of duodenal diverticula are asymptomatic [4]. For patients who exhibit symptoms, there is no standardized approach to treatment, and clinical decisions must be tailored to each patient. As is the case for colonic diverticula, the most definitive treatment option for symptomatic periampullary diverticula is diverticulectomy [13]. However, certain cases do not warrant surgical intervention, and alternative treatment options exist for patients who are poor surgical candidates or decline invasive procedures. In patients with minimal or no symptoms, conservative management is the mainstay of therapy with high-fiber diet [14]. Patients with obstructive pancreaticobiliary complications such as cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, and pancreatitis warrant emergent intervention through endoscopic sphincterotomy or stenting, and possibly diverticulectomy [6, 8]. Interestingly, as was the case in our patient, some instances of symptomatic periampullary diverticula may be successfully treated with simple diverticular lavage, with resolution of symptoms similar to those who have received more invasive therapies. In patients with concurrent symptoms of diverticulitis or cholangitis, including fever, leukocytosis, and elevated inflammatory markers, antibiotic therapy is also warranted. As a potential bridge to definitive diverticulectomy, less-invasive endoscopic techniques, including simple tap-water lavage, may provide sufficient symptomatic relief in the interim and should be considered as a first step. It is unclear whether the type of Lemmel syndrome influences outcomes or treatment approach, as this information is largely unreported and difficult to ascertain among published case reports.

In summary, the diagnosis of Lemmel syndrome should be made based on the presence of a periampullary duodenal diverticulum causing compression and dilatation of the pancreatic and/or common bile ducts, with or without the presence of jaundice. The presence of a periampullary diverticulum can result in local compression of a variety of structures, not limited to pancreatic and common bile ducts, and cause a wide variety of symptoms, ranging from asymptomatic cholestatic laboratory values to GOO to ascending cholangitis and diverticulitis. The most sensitive imaging modality in suspected cases of Lemmel syndrome is CT abdomen with contrast and can be followed by direct visualization via side-viewing duodenoscope and, in clinically indicated cases, ERCP to allow for potential therapeutic intervention. In patients with mild symptoms, diet modification and diverticular lavage may offer complete resolution of symptoms. In more severe cases, endoscopic biliary cannulation and sphincterotomy may provide adequate relief and circumvent the need for invasive surgical intervention.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval is not required for this study in accordance with local and national guidelines. The guardian and caregiver of the patient detailed in our original case report provided informed written consent for use of all relevant images, lab results, and pertinent medical history. Patient’s guardian consented to having the case published anonymously. Guardian consent was obtained because our patient lacked decisional capacity due to underlying chronic medical conditions.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding sources were utilized to perform this case report and literature review.

Author Contributions

James Love, Cemal Yazici, Constantine Melitas, and Fred Zar analyzed and interpreted the patient data and had direct contact with the patient. James Love and Meredith Yellen reviewed the literature and wrote the manuscript. Fred Zar and Cemal Yazici assisted in the editing and revision process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

No funding sources were utilized to perform this case report and literature review.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this review are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Piscopo N, Ellul P. Diverticular disease: a review on pathophysiology and recent evidence. Ulster Med J. 2020 Oct;89(2):83–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kang HS, Hyun JJ, Kim SY, Jung SW, Koo JS, Yim HJ, et al. Lemmel’s syndrome, an unusual cause of abdominal pain and jaundice by impacted intradiverticular enterolith: case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2014 May;29(6):874–8. 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.6.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pearl MS, Hill MC, Zeman RK. CT findings in duodenal diverticulitis. Am J Roentgenol. 2006 Oct;187(4):W392–5. 10.2214/ajr.06.0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA. Surgical treatment: evidence-based and problem-oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Desai K, Wermers JD, Beteselassie N. Lemmel syndrome secondary to duodenal diverticulitis: a case report. Cureus. 2017 Mar;9(3):e1066. 10.7759/cureus.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernshteyn M, Rao S, Sharma A, Masood U, Manocha D. Lemmel’s syndrome: usual presentation of an unusual diagnosis. Cureus. 2020 Apr;12(4):e7698. 10.7759/cureus.7698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nayyar N, Sood S, Tomar A. Lemmel’s syndrome. Appl Radiol. 2019 Sep;48(5):48A–48B. 10.37549/ar2600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yanagaki M, Shiba H, Hagiwara S, Hoshino M, Sakuda H, Furukawa Y, et al. A successfully treated case of Lemmel syndrome with pancreaticobiliary maljunction: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020 Jun;72:560–3. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.06.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Khan BA, Khan SH, Sharma A. Lemmel’s syndrome: a rare cause of obstructive jaundice secondary to periampullary diverticulum. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4(6):000632. 10.12890/2017_000632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tobin R, Barry N, Foley NM, Cooke F. A giant duodenal diverticulum causing Lemmel syndrome. J Surg Case Rep. 2018 Oct;2018:rjy263. 10.1093/jscr/rjy263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bellamlih H, Echchikhi M, El Farouki A, Moatassim Billah N, Nassar I. An unusual cause of obstructive jaundice: lemmel’s syndrome. BJR Case Rep. 2021 Apr;7(2):20200166. 10.1259/bjrcr.20200166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Volpe A, Risi C, Erra M, Cioffi A, Casella V, Fenza G. Lemmel’s syndrome due to giant periampullary diverticulum: report of a case. Radiol Case Rep. 2021 Dec;16(12):3783–6. 10.1016/j.radcr.2021.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kansoun A, El-Helou E, Amiry AR, Bahmad M, Mohtar IA, Houcheimi F, et al. Surgical approach for duodenal diverticulum perforation: a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020 Oct;76:217–20. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.09.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ferreira-Aparicio FE, Gutiérrez-Vega R, Gálvez-Molina Y, Ontiveros-Nevares P, Athie-Gútierrez C, Montalvo-Javé EE. Diverticular disease of the small bowel. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012 Sep;6:668–76. 10.1159/000343598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Somani P, Sharma M. Endoscopic ultrasound of Lemmel’s syndrome. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2017 Mar;36(2):155–7. 10.1007/s12664-017-0744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miyajima S, Yamakawa G, Ohana M. Edwardsiella tarda-associated cholangitis associated with Lemmel syndrome. IDCases. 2018 Feb;11:94–6. 10.1016/j.idcr.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oliveira DM, Correia C, Cunha F, Dias P. A rare cause of abdominal pain with fever. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Mar 16;12(3):e228401. 10.1136/bcr-2018-228401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Venkatanarasimha N, Yong YR, Gogna A, Tan BS. Case 265: Lemmel syndrome or biliary obstruction due to a periampullary duodenal diverticulum. Radiology. 2019 Apr;291(2):542–5. 10.1148/radiol.2019162375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alzerwi NAN. Recurrent ascending cholangitis with acute pancreatitis and pancreatic atrophy caused by a juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum: a case report and literature review. Medicine. 2020 Jul;99(27):e21111. 10.1097/MD.0000000000021111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frauenfelder G, Maraziti A, Ciccone V, Maraziti G, Caleo O, Giurazza F, et al. Computed tomography imaging in Lemmel syndrome: a report of two cases. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2019 May;9:23. 10.25259/JCIS-17-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rouet J, Gaujoux S, Ronot M, Palazzo M, Cauchy F, Vilgrain V, et al. Lemmel’s syndrome as a rare cause of obstructive jaundice. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012 Dec;36(6):628–31. 10.1016/j.clinre.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tabata S, Miyazato K, Hoshino K, Arakaki S, Hokama A, Fujita J. Diagnosis of Lemmel’s syndrome by air insufflation during endoscopy. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2020 Jan;130(1):66–7. 10.20452/pamw.14977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Love J, Melitas C, Yazici C, Zar F. Lemmel Syndrome: An Unusual Presentation with Gastric Outlet Obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S1054–5. 10.14309/01.ajg.0000783524.45064.ae. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this review are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.