Abstract

Within the human lung, mast cells typically reside adjacent to the conducting airway and assume a mucosal phenotype (MCT). In rare pathologic conditions, connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) can be found in the lung parenchyma. MCTCs accumulate in the lungs of infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a chronic lung disease associated with preterm birth, which is characterized by pulmonary vascular dysmorphia. The human mast cell line (LUVA) was used to model MCTCs or MCTs. The ability of MCTCs to affect vascular organization during fetal lung development was tested in mouse lung explant cultures. The effect of MCTCs on in vitro tube formation and barrier function was studied using primary fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. The mechanistic role of MCTC proteases was tested using inhibitors. MCTCLUVA but not MCTLUVA was associated with vascular dysmorphia in lung explants. In vitro, the addition of MCTCLUVA potentiated fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell interactions, inhibited tube stability, and disrupted endothelial cell junctions. Protease inhibitors ameliorated the ability of MCTCLUVA to alter endothelial cell angiogenic activities in vitro and ex vivo. These data indicate that MCTCs may directly contribute to disrupted angiogenesis in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. A better understanding of factors that regulate mast cell subtype and their different effector functions is essential.

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is the most common pulmonary disease because of premature birth, resulting in 10,000 BPD cases annually in the United States alone.1, 2, 3, 4 A BPD diagnosis increases the risk of long-term pulmonary morbidity, including recurrent wheezing and asthma.3,5, 6, 7 Multiple pathologic symptoms are associated with BPD, including alveolar simplification, disrupted vasculogenesis, altered inflammation, and oxygen toxicity.1, 2, 3, 4,6, 7, 8, 9, 10

It is widely believed that mast cells (MCs) arise from the common myeloid progenitor via the basophil/MC progenitor as MC progenitors.11, 12, 13 MC progenitors are released from the bone marrow and enter target tissues, where they mature under the instructive signals of their local microenvironment.11,14 Consequently, MCs from various tissues differ phenotypically from each other. Distinct populations are named [mucosal MCs (MCTs) and connective tissue MCs (MCTCs)] based on the location in which they were first identified. It was later discovered that the two MC subtypes express different proteases.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 MCTCs express two tryptases (TPSAB1 and TPSB2), carboxypeptidase A3 (CPA3), and chymase 1 (CMA1), whereas MCTs express only tryptases.16, 17, 18,20 In healthy human lungs, MCTs are found in the trachea and large airways.11,14,21,22

A significant enrichment of MC-specific genes in BPD has been previously identified.10 Immunohistochemical staining of lung tissues confirmed a 50-fold increase in the accumulation of CMA-expressing MCTCs in lungs with BPD.10 MCTCs are rare in human lungs but are found in asthma with high Th2 cell counts and in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.23, 24, 25, 26, 27 The accumulation of MCTCs in a genetic model with BPD-like pathologic features has also been reported.10 Another report found that MC accumulation in a model of BPD was associated with neonatal supraphysiologic oxygen exposure and that MC-deficient mice are partially protected from pathologic findings.22 This study did not provide insight into the phenotype of the MCs involved.

Although several studies describe disorganization of the pulmonary microvasculature in BPD, limited studies have explored the cause of this impairment.3,9,28,29 Pulmonary vasculature development starts at embryonic day (ED) 9.5 in mice or gestational week 4 in humans.3,30,31 The preexisting loose network of endothelium begins to arrange around the distal airspaces during the canalicular stage through the process of angiogenesis and vasculogenesis.9,31 Capillaries are then embedded in the primary septa during the saccular phase and continue to expand and mature.9,31 Premature infants born at 24 to 27 weeks of gestation are in the late canalicular stage (ED 16.5 to 17.5 in mice), which is also the period of high BPD risk.2, 3, 4,9

We hypothesized that MCTC accumulation contributes to the impaired vascularization during early lung development in BPD. We found that human MCTCs but not MCTs significantly disrupt vascular organization in mouse fetal lung explants and human fetal lung microvascular endothelial cells. Mechanistically, MCTCs enhance initiation of endothelial cell-cell interactions but destabilize mature endothelial cell tight junctions.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

LUVA (Kerafast, Boston, MA), an immortalized human MC line, derived from an 8-week–old CD34+ mononuclear cell culture,32 were maintained in StemPro34 (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplied with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 200 mmol/L l-glutamine. LUVAs express all three MC-specific proteases, including TPSAB1/TPSB2, CMA1, and CPA3, under these culture conditions.

Fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (feHPMVCs; ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA) were maintained in endothelial cell growth medium with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 5% fetal bovine serum. All experiments were conducted with feHPMVCs within 5 passages.

Human bronchial epidermal (16HBE) cells, a SV40 transformed human bronchial epithelial cell line, were grown using Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% nonessential amino acids, sodium pyruvate, and HEPES buffer. 16HBE cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2. The cells were allowed to form tight junctions and then differentiated at air-liquid interface.

All animal-related experiments are approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY) under protocol 2008-043E.

Induced MCTs

16HBE cells were seeded on the apical surface of a 12-well transwell (Corning, Corning, NY) and allowed to reach confluence. The epithelial cells were allowed to form tight junctions, then differentiated at air-liquid interface for 2 days. LUVAs were then seeded at 0.25 million cells/mL in the basal chamber. The phenotype of the co-cultured MCs were assessed by quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis of the expression levels of TPSAB1, TPSB2, CMA1, and CPA3 (Supplemental Figure S1A). Changes in CMA1 and phosphorylated CPA3 were then confirmed using Western blot analysis. Western blot (Supplemental Figure S1B) confirmed the absence of CMA1 and CPA3 in co-cultured LUVAs.

Ex Vivo Angiogenesis Experiments

Timed mating of wild-type C57BL/6J mice was performed. At ED 16, the dam was sacrificed and mouse embryos were dissected from the uterine horns. The lung lobes of ED 16 mice were carefully dissected, washed twice with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline, and then placed on the apical surface of fibronectin (F1141, 2 mg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) precoated transwells. The individual lung lobes were allowed to attach for 30 minutes at 37°C and cultured at 37°C for 48 hours in the absence or presence of 30,000 feHPMVC-primed MCTC/MCT LUVAs in the bottom chamber.

In Vitro Angiogenesis Experiments

The 96-well tissue culture plates were coated with Matrigel (Corning) on ice and allowed to polymerize at 37°C for 30 minutes. feHPMVCs were then seeded at 2000 cells per well alone (control) and mixed with 5000 MCTCs or 5000 MCTs. The cells were imaged for 12 hours using an inverted phase-contrast microscope. The images were processed and quantified for tube complexity (number of mesh) using ImageJ software version 1.52a(NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij).

Transendothelial Electrical Resistance

feHPMVC cultures were seeded at 100,000 cells per well in fibronectin-coated inserts of a 12-well transwell plate and allowed to grow to confluence. The cells were allowed to form tight junctions until the transendothelium electrical resistance (TEER) was >200 mΩ. MCTCs or MCTs were added at 20,000 cells per well to the bottom well, and TEER was measured after 12 hours with an epithelial volt/ohm meter voltahmmeter (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) equipped with a pair of Chopstick Electrode Sets (World Precision Instruments).33

Paracellular Endothelial Permeability Assay

feHPMVC cultures were seeded at 100,000 cells per well on fibronectin-coated inserts of a 12-well transwell plate and allowed to establish tight junctions, as above. MCTCs or MCTs were added at 20,000 cells per well to the bottom well, respectively. Then 100 μL of 300-μg/mL fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran (10,000 mol. wt.; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to the media in the apical chamber. The maximum possible permeability was established by adding fluorescein isothiocyanate–dextran to fibronectin-coated transwells without cells. After 6 hours, 100 μL of media was harvested from the basal chamber, and fluorescence intensities were quantified on a VICTOR2 1420 Multilabel Counter using Wallac software (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA). The fluorescent intensities from all samples were normalized to the fluorescent intensity of the maximum possible permeability.

Inhibitor Treatment

For inhibitor treatment, 200 μg/mL of soybean-derived serine protease inhibitor (VWR AMRESCO, K213-1G; Avantar, Radnor, PA) or 30 μmol/L chymostatin (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) was applied to LUVAs for 1 hour. Before adding to endothelial cells, the LUVA cells were washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline and added to the in vitro angiogenesis experiments.

RT-qPCR

Quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed using predeveloped noncommercial assays (PrimerBank, http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank, last accessed June 9, 2016). Briefly, RNA samples were isolated using the Absolutely RNA Microprep kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Reverse transcription reaction was performed using the Script cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA), and cDNA samples were run in duplicate using Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The results were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method.

Western Blot Analysis

To confirm MC phenotype, LUVAs were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on ice and then boiled at 100°C for 10 minutes. To detect MC proteases in the conditioned media, the media was snap frozen with liquid nitrogen and then boiled for 10 minutes. Samples were then resolved on SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (BioRad). Membranes were blocked by incubating in 5% (w/v) molecular grade blocker (BioRad) in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 for 1 hour at room temperature. MC-specific proteases were detected by overnight incubation in antibodies (1:1000 dilution) against tryptase-β2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), CMA1 (MA5-11717; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and CPA3 (16236-1-AP; Proteintech). Finally, membranes were incubated for 1 hour with a mouse anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) or goat anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody and developed using Supersignal West Pico PLUS kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Lectin Staining

Ex vivo cultured E16.5 C57BL/6J mouse lungs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The fixed lobes were then cleared using a protocol adapted from CUBIC Cancer3 and stained with tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated isolectin-IB4 (L5264; Sigma-Aldrich) and DAPI (D3571; Invitrogen). The samples were then mounted and visualized using a multiphoton microscope (FVMPE-RS; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

feHPMVCs monolayers on transwells were fixed using ice-cold 10% neutral buffered formalin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The fixed feHPMVCs were then stained with DyLight 594–labeled Ulex Europaeus Agglutinin I (DL-1067, 1:1000 dilution; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Immunofluorescent Staining

Ex vivo cultured E16.5 C57BL/6J mouse lungs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The fixed lobes were then cleared using a protocol adapted from CUBIC Cancer34 and stained with Von Willebrand factor primary antibodies (GA52761-2, 1:250 dilution; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Primary antibody staining was then detected by Texas Red–conjugated goat–anti-rabbit secondary antibody (T6391, 1:1000 dilution; Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA). DAPI was used to stain nuclei. The samples were then mounted and visualized using a multiphoton microscope (FVMPE-RS, Olympus).

feHPMVC monolayers on transwells were fixed using ice-cold 10% neutral buffered formalin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The fixed feHPMVCs were then stained with mouse anti-human CDH5 antibody (555661, 1:250 dilution; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Nucleus were stained with DAPI. The samples were then visualized using a DM5500B fluorescent microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Three-Dimensional Reconstruction and Quantification

Three-dimensional reconstruction was performed using segmentation function with Amira software version 6.5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reconstructed surfaces were visualized with surface view function. The volumes of the reconstructed structure were listed in the material statistics. The relative vessel volume was determined by normalizing the volume of IsolectinB4 to the volume of DAPI in each field.

Statistical Analysis

Data that involved pairwise comparison (such as quantitative PCR, Western blot, relative vessel volume, growth phase or decay phase time, TEER, or paracellular vascular permeability) were tested using a paired t-test. The tube complexity overtime and of branches in in vitro angiogenesis experiment were tested using the χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

MCTCs Induce Fetal Lung Microvascular Dysmorphism ex Vivo

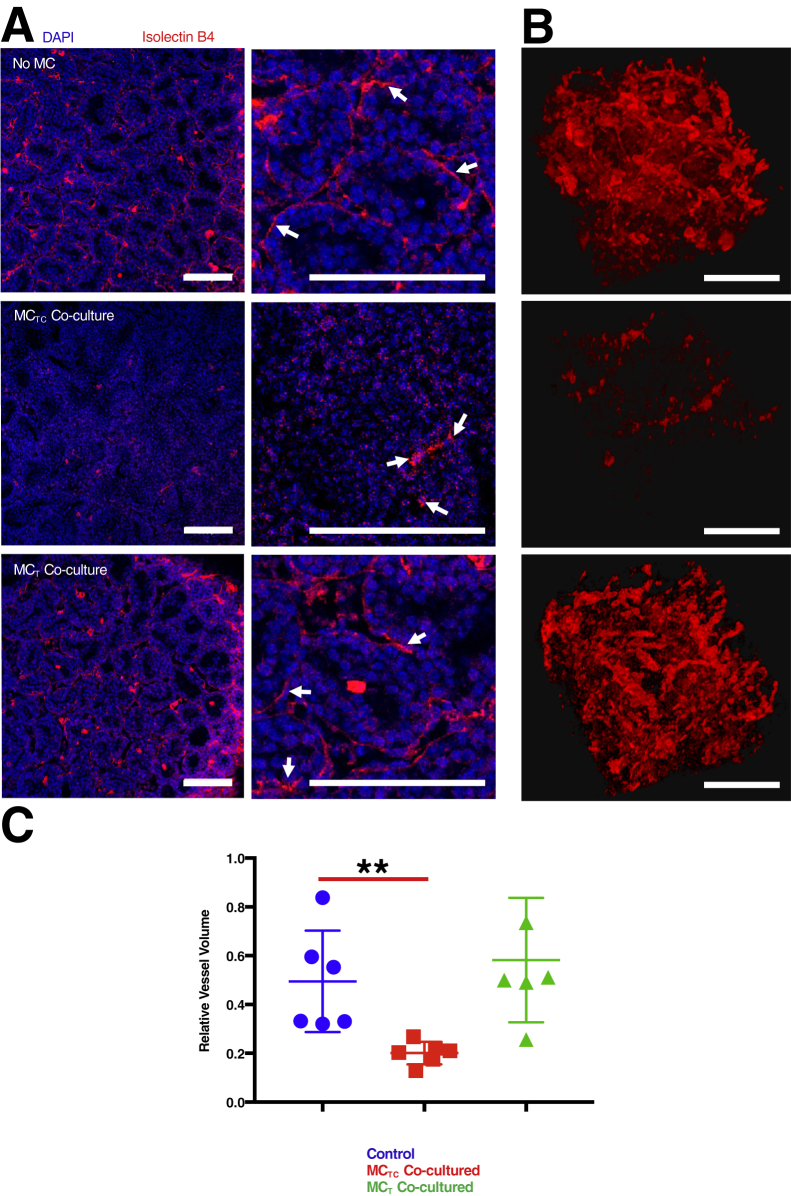

Previous studies described the accumulation of MCTCs in BPD10 and mouse models of BPD-like pathologic findings.22 Disruption and deficiency in lung parenchyma microvasculature have been well described in BPD.2,3,9 Therefore, this study tested whether there was a direct link between the presence of MCs and microvascular dysmorphia during fetal lung development at a stage when BPD risk is highest. Fetal lung tissues were isolated from ED 16.5 mice and placed in culture for 48 hours in the absence or presence of human MCs. Lung microvasculature (Figure 1) was compared by reconstructing the thee-dimensional structure of DAPI-stained nuclei and isolectin B4 staining vessels. A significant reduction was observed in the relative vessel volume when mouse lung tissues were cultured in the presence of MCTCs (t-test P = 0.0069) (Figure 1C). Lungs co-cultured with MCTCs also had a marked dysmorphism, featuring reduced connection among endothelial cells (Figure 1B). Importantly, when mouse lung tissues were cultured in the presence of MCTs (Figure 1, A and B), vascular structure was normal (Figure 1B). These results were confirmed by Von Willebrand factor staining of vascular endothelial cells (Supplemental Figure S2). This study tested whether these observations were associated with the presence of cell death but low levels of apoptotic cells were found in all conditions (Supplemental Figure S3, A and B). Interestingly, RT-qPCR analysis found no significant loss of pulmonary endothelial cell marker gene expression (Supplemental Figure S3C). These data suggest that MCTC-induced vascular dysmophism may be due to alterations in endothelial cell capacity to form vessels.

Figure 1.

Connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) cause microvascular dysmorphism in the developing lung. A: Representative images of embryonic mouse lung tissue explant cultured for 48 hours alone [no mast cells (MCs) (control)] and with MCTCs or mucosal phenotype mast cells (MCTs). The microvasculature was stained with tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated isolectin B4 (red), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Arrows indicate endothelial cells stained with Isolectin B4. B: Representative three-dimensional reconstructed microvasculature showing the inset region. C: Quantification of total volume of vasculature relative to the total nuclear volume in each condition. n = 6 (and in triplicates). ∗∗P < 0.01 (t-test). Scale bars = 100 μm.

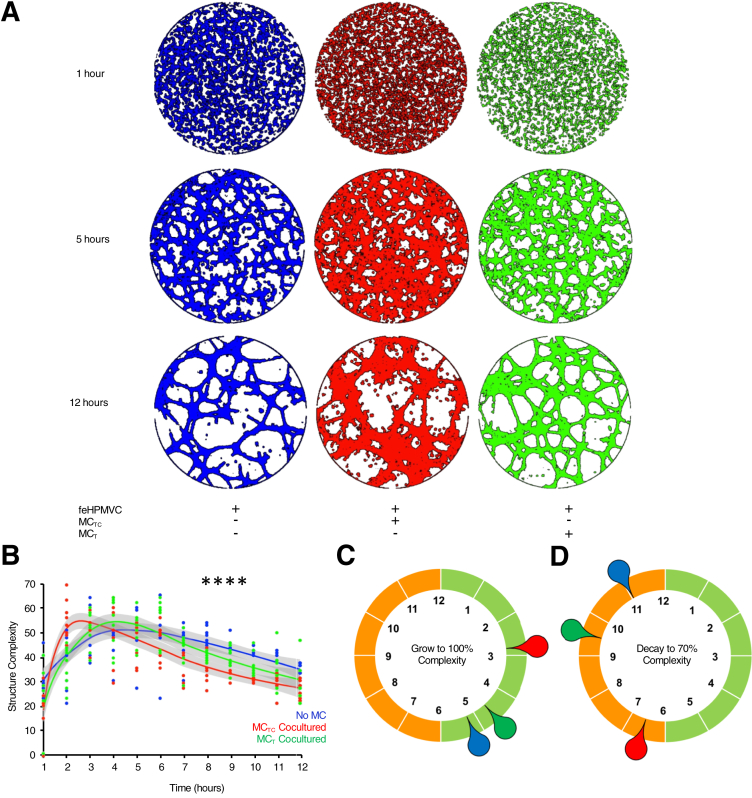

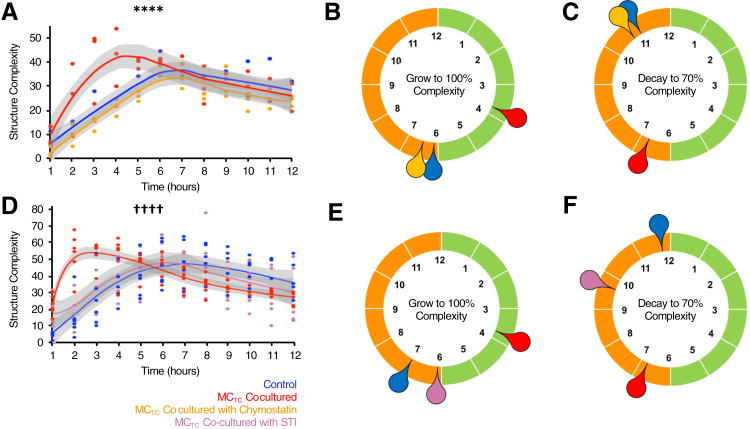

MCTCs Directly Disrupt feHPMVC Tube Formation

The effects of MCTCs on vascular structure were confirmed by testing their ability to directly alter feHPMVC tube formation. feHPMVCs were allowed to form tubes during a 12-hour period in the absence or presence of MCs. Hourly imaging quantified the initiation and stabilization of tubular structures (Figure 2). Co-culture of feHPMVCs with MCTCs was associated with notable differences in tubular structures (χ2 test P < 0.0001) (Figure 2). When co-cultured with MCTCs, the rate of developing tubular complexity was a mean of 1.8 hours faster (2.87 versus 5.25 hours, t-test P < 0.0001) when compared with feHPMVCs cultured on matrigel alone (Figure 3C). The stability of tubular structures in MCTC co-cultured samples was also disrupted compared with feHPMVCs cultured on matrigel alone (Figure 2). The time at which the cultures reached a 70% reduction in complexity was reduced by a mean of 4.5 hours faster (11 versus 6.75 hours, t-test P = 0.0046). feHPMVCs co-cultured on matrigel with MCTs had no significant differences in tube formation, including in both the initiation and stabilization phases.

Figure 2.

Connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) disrupt endothelial cell tube formation. A: Representative, color-enhanced images of fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (feHPMVCs) undergoing tube morphogenesis when cultured for 12 hours alone (blue) and with MCTCs (red) or mucosal phenotype mast cells (MCTs) (green). B: Quantification of tube complexity (Materials and Methods) defined each hour during tube formation. C: Graphical representation of the mean time (in hours) needed to reach maximum tube structure complexity for each condition. D: Graphical representation of the mean time (in hours) needed for tube structures to regress to 70% of their maximum complexity. n = 3 (and in triplicates). ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 control versus MCTC co-culture (χ2 test).

Figure 3.

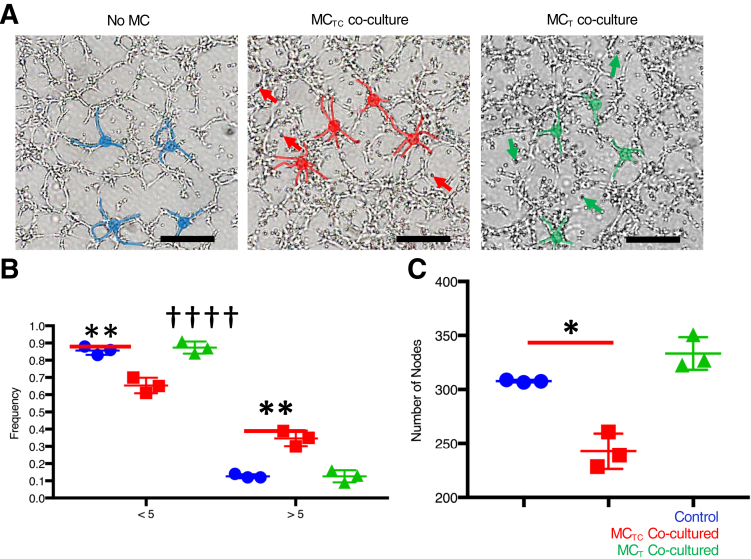

Connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) promote the initiation of endothelial cell-cell contacts during tube formation. A: Representative, color-enhanced images of fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (feHPMVCs) undergoing tube morphogenesis when cultured for 2 hours alone and with MCTCs or mucosal phenotype mast cells (MCTs). Representative feHPMVC cell-cell junctions are highlighted. No MC (control) is labeled in blue, MCTC co-culture is labeled in red, and MCT co-culture is labeled in green. Red arrows indicate representative MCTC human mast cell lines (LUVAs); green arrows, representative MCT LUVAs. B: Quantification of the frequency of cell-cell junctions containing <5 cells or ≥5 cells in each condition. C: Quantification of the total number of junctions in each condition. n = 3 (and in triplicates). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 (t-test); ††††P < 0.0001 versus control (χ2 test). Scale bars = 500 μm.

MCTCs Promote Initiation but Disrupt Maintenance of Endothelial Cell-Cell Interactions

The number of cells at individual cell-cell junctions during the initiation of feHPMVC tube formation (2 hours) was carefully quantified. During this initial phase, feHPMVCs appear to elongate, migrate, and form multicellular nodes. These nodes are composed of two to five individual endothelial cells, with most nodes containing three cells (Figure 3A). When feHPMVCs were cultured with MCTCs, a significant shift in the distribution (χ2 test P < 0.0001) of endothelial cells per node (Figure 3B) was observed. The shift included an increase in the number of nodes with more endothelial cells, with a significant increase in the number of nodes that contained five branches (13% versus 35%, P = 0.0012). No differences in the distribution of the number of cells that formed nodes was observed in feHPMVCs when co-cultured with MCTs.

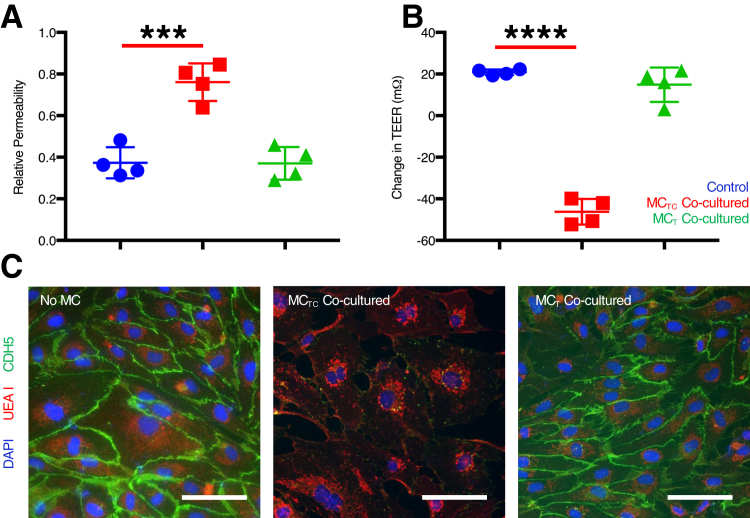

Although MCTCs appeared to promote initiation of endothelial cell-cell junction formation in nodes, they also were associated with an inability to maintain tube structures. Therefore, this study then tested whether MCTCs inhibited the stability of endothelial cell-cell interactions. feHPMVC monolayers were grown to confluence in the upper chamber of a transwell and assayed for TEER and pericellular permeability in the absence or presence of MCs placed in the bottom chamber. TEER was significantly reduced in feHPMVC monolayers that contained MCTCs (t-test P < 0.0001) (Figure 4B). Similarly, pericellular permeability was significantly increased in feHPMVC monolayers that contained MCTCs (t-test P < 0.0006) (Figure 4A). MCTs had no effects on feHPMVC TEER or permeability. In addition, immunostaining for CDH5 revealed a drastic and selective loss of cell-cell junctions in the presence of MCTCs but not MCTs (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) destabilize endothelial cell-cell junctions. A: Quantification of paracellular permeability of fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell (feHPMVC) monolayer alone (control; blue) and with MCTCs (red) or mucosal phenotype mast cells (MCTs; green). B: Quantification of transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) in confluent cultures of feHPMVC monolayers alone (control) (blue) and with MCTCs (red) or MCTs (green). C: Representative images of feHPMVC monolayers in each condition indicated. Cell-cell contacts are visualized by staining for CDH5 (green), and endothelial cell surface glycoprotein (UEA1) and nuclei are visualized by DAPI. n = 4 (and in triplicates). ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 (t-test). Scale bars = 100 μm.

CMA Activity Is Necessary for the Vasculodisruptive Effects of MCTCs

We hypothesized the MC-specific serine proteases, including tryptase (tryptase-α/β1 and tryptase-β2) and CMA1 played an important role in the vasculodisruptive effects we identified. Therefore, this study analyzed the effects of two different serine protease inhibitors, soybean trypsin inhibitor or chymostatin, on the ability of MCTCs to affect endothelial cell tube formation in vitro (Figure 5). Soybean trypsin inhibitor pretreatment of MCTCs completely blocked the accelerated initiation of feHPMVC tube formation (Figure 5) and the increased instability of feHPMVC tube complexity (Figure 5). Chymostatin pretreatment of MCTCs completely blocked the accelerated initiation of feHPMVC tube formation (Figure 5) and partially but significantly blocked the increased instability of feHPMVC tube complexity (Figure 5, D and F). These data suggest that broad inhibition of MC proteases (by soybean trypsin inhibitor) or preferential inhibition of CMA (by chymostatin) significantly blocks the ability of MCTCs to after in vitro endothelial cell angiogenesis.

Figure 5.

Serine protease inhibition protects against disrupted endothelial cell tube formation. Fetal human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (feHPMVCs) were allowed to undergo tube morphogenesis for 12 hours alone (control; blue) and with connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs; red) or with mucosal phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) pretreated with soybean derived trypsin inhibitor (STI; yellow; A–C) or chymostatin (purple; D–F). A and D: Quantification of tube complexity (Materials and Methods) defined each hour during tube formation. B and E: Graphical representation of the mean time (in hours) needed to reach maximum tube structure complexity for each condition. C and F: Graphical representation of the mean time (in hours) needed for tube structures to regress to 70% of their maximum complexity. n = 3 (and in triplicates). ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 control versus chymostatin treated (χ2 test); ††††P < 0.0001 control versus STI treated MCTC co-culture (χ2 test).

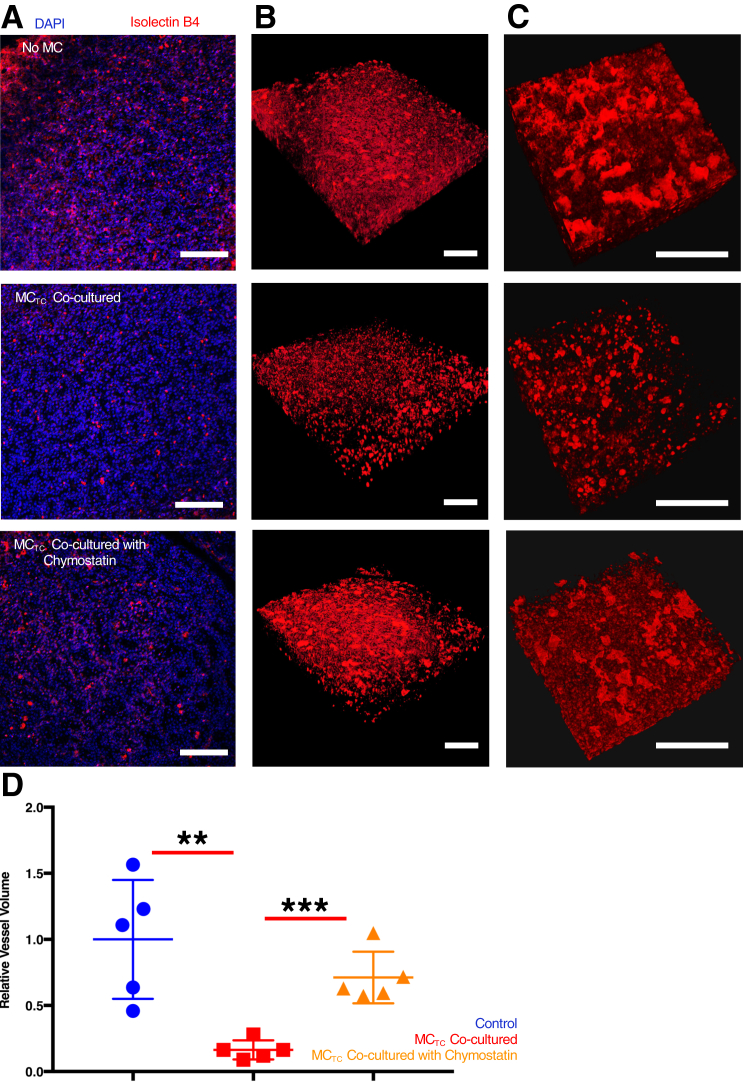

This study next examined whether chymostatin treatment blocked the ability of MCTCs to disrupt vascular structures in embryonic lung tissue ex vivo. Again, vascular structures in ED 16.5 mouse lung tissue were visually disrupted when cultured in the presence MCTCs for 48 hours (Figure 6, A–C), including a quantitative reduction in tissue vessel volume (Figure 6D). However, when MCTCs were pretreated in chymostatin, their ability to disrupt vascular structures was significantly attenuated (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Chymase inhibition protects against microvascular dysmorphism in the developing lung. A: Representative images of embryonic mouse lung tissue explant cultured for 48 hours alone [no mast cells (MCs) (control)] and with connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) or with MCTCs pretreated with chymostatin. The microvasculature was stained with tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated isolectin B4 (red), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). B: Representative three-dimensional reconstructed microvasculature in A. C: Representative three-dimensional reconstructed microvasculature showing higher magnification of a region in B. D: Quantification of total volume of vasculature relative to the total nuclear volume in each condition. n = 5 (and in triplicates). ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 (t-test). Scale bars = 100 μm.

Discussion

Prior studies have revealed MCs are heterogeneous, with molecular phenotypes defined by their tissue environment.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Commonly acknowledged MC subtypes include MCTCs and MCTs, which are classified predominantly based on their protease composition.17, 18, 19 Although MCs occupy the lung and upper airways, they commonly assume a MCT phenotype. MCTCs are rare in the distal lung and typically only found in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or refractory/severe asthma.11,14,18,21,22,24,26,35,36 Despite the potential for distinct MC phenotypes to have distinct functions, the pathophysiologic effects of the presence of MCTCs in the lung are not clear. MCs, particularly MCTCs, accumulate in the lungs of infants with severe BPD.10 The goal of this study was to understand the possible consequences of MCTC accumulation in the BPD lung parenchyma. Because parenchymal vascular abnormalities are a cardinal feature of BPD, this study tested whether MCTCs could directly disrupt the formation of the parenchymal vasculature, which is essential for lung function. This study found that MCTCs, but not MCTs, lead to abnormal formation of pulmonary microvascular endothelial structure both ex vivo and in vitro. Importantly, the activity of MC-specific proteases are necessary for the vasculodisruptive effects.

MCs can disrupt angiogenesis under pathologic conditions.22,26,37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 MC accumulation was observed in some BPD animal models, including hyperoxia challenged mice and rats.22 A study in pulmonary hypertension, which is often associated with BPD, suggests that MCTCs promote lung vascular remodeling.41 Interestingly, a recent BPD study found that MC-deficient mice are protected from air space damage by neonatal hyperoxia, which hints at the antiangiogenic effects of MCs under this condition22 The current ex vivo study provides direct evidence of the possible impairment MCTC accumulation can cause in the late-canalicular and early-saccular phase, during which preterm infants are at high risk for BPD.2,4,9 Interestingly, a study in mice found that the presence of MCTCs is important for the proper development of spinal cord vasculature.49 A different study in chicken lung also found that MCTCs and MCTs are recruited during embryonic development.50 However, MCTCs are rarely found in healthy human lungs, and a mouse embryonic study found that MCs are not recruited to the healthy lung until after delivery.51 This evidence indicates that MCTCs can facilitate vascular development and remodeling but do not contribute to normal human lung development.

Although MCTCs were clearly associated with a diminution in lung vascular structures ex vivo (Figures 1 and 6), it was noted that their presence had a biphasic effect on endothelial cell tube formation in vitro (Figures 2 and 5). This study quantified endothelial tube stability by measuring the time at which the cultures had 70% of maximal tube complexity. This decision was based on a careful evaluation of the timing and distribution of tubular structures (data not shown), suggesting the effect size was most evident at this level.

Disruption of cell-extracellular matrix and cell-cell interactions is reported to be involved in microvascular structure dysmorphism.52, 53, 54 The current study data suggest that MCTCs caused a marked loss of CDH5 but spared many other surface proteins, such as the targets of isolectin B4 (Figure 4C). CDH5 is important for maintaining endothelial adherens junctions, which help to balance vascular quiescence and angiogenesis. The loss of surface CDH5 can lead to increased cell migration and proliferation.53 In fact, preliminary studies suggest that MCs can significantly enhance feHPMVC proliferation (data not shown), which is a phenotype consistent with tight junction impairment. Another recent study found that the loss of surface CDH5 on corneal microvascular endothelial cells leads to a microvasculature simplification, resembling the current study's in vitro phenotype.54

Our serine protease inhibitor experiments suggest that MC proteases, specifically CMA1, play an important role in disrupting angiogenesis (Figures 5 and 6). This finding is consistent with the previous in vivo study, which found that inhibition of CMA1 can protect against renal microvascular damage in the diabetic rat.55 CMA1, tryptase-α/β1 and tryptase-β2 may affect angiogenesis through many different mechanisms.37,43,45,46 CMA1 can cleave angiotensin I, producing angiotensin II and promoting matrix metalloproteinase 9 maturation. MC serine proteases can also cleave membrane-bound stem cell factor (SCF), stimulating production of more SCF.27,52 Our preliminary RT-qPCR analysis found a significant increase in feHPMVC SCF gene regulation (data not shown). This finding is partially supported by a study that found that SCF is a potent endothelial permeability factor that promotes internalization of CDH5 in mouse corneal model,52 which leads to corneal microvasculature dysmorphism.

There are limitations to the studies presented here. Although the effects of human MCs on human endothelial cells are studied here in vitro, LUVA does not recapitulate all aspects of human primary MCs. Likewise, our ex vivo mouse lung model lacks many of the complexities of the postnatal human lung. Moreover, mouse lung and human MC line (LUVA) co-culture can have potential histoincompatibility issues. This study used the transwell system with a 0.45-μm filter size, which prevents the mouse lung and human MC line (MCTC LUVA) from direct contact. This study also included MCT LUVA as the second control, which helped rule out the possible phenotype due to histoincompatibility. However, these studies take advantage of using the mouse lung from the saccular stage of histologic development, the time when infants are at the greatest risk for BPD.3,9,30 Interestingly, DAPI staining of ex vivo lung tissue suggested changes in the overall structure of the parenchymal region in the presence of MCTCs. These changes may be a secondary effect of the vascular dysmorphia caused by MCTCs or could be an independent and direct effect. This study did not quantify these changes because our system almost certainly does not recapitulate proper distal airspace structure or morphologic features. Testing the effects of MCTCs directly on alveolar formation and structure should be directly tested in appropriate model systems and is one focus of our future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Siva K. Solletti, Dr. Ravi Misra, Christopher S. Slaunwhite, Kathy Donlon, Cory J. Poole, and Tristan McRae for advice and experimental support; and Dr. Michael Welte, David S. Goldfarb, and Sina Ghaemmaghami for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supported by Pediatric Molecular and Personalized Medicine Program (T.J.M.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.04.017.

Author Contributions

Y.R., T.J.M., and J.P. designed the studies; J.A.M. and J.P. contributed reagents and experiment materials; Y.L. and S.W. established research protocols; Y.R. performed the studies; Y.R. and T.J.M. analyzed data; and Y.R. and T.J.M. wrote the manuscript; all authors approved the manuscript.

Supplemental Data

Human lung epithelial cells induce a mucosal-like phenotype in human mast cells. The human mast cell line (LUVA) was exposed to the human bronchial epidermal (16HBE) human lung airway–like epithelial cell line and then assessed for mast cell–specific protease expression at the mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels. A: A three-dimensional scattered plot indicating relative expression levels of CMA1, CPA3, and TPSB2 mRNA level. The color indicates the subtype score of each sample determined by fold change of TPSB2 divided by the product of CMA1 and CPA3 fold change. Epithelial cell exposure leads to a mucosal-like mast cell (MCT) phenotype with low CMA1, low CPA3, and high TPSB2. This phenotypic change persisted for >2 days after removal of epithelial cells/conditioned medium. B: Western blot analysis of cell lysates from LUVAs cultured alone [connective tissue phenotype mast cell (MCTC)] or co-cultured with 16HBEs (MCT). n = 3 (and in triplicates).

Von Willebrand factor (VWF) staining reveals microvascular dysmorphism in the developing lung. Representative images of embryonic mouse lung tissue explant cultured for 48 hours alone [no mast cells (MCs) (control)] or with connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) or mucosal phenotype mast cells (MCTs). The microvasculature was stained with VWF antibody (red), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). n = 5 in duplicates. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) do not induce endothelial cell apoptosis. A: Representative images of embryonic mouse lung tissue explant cultured for 48 hours alone [no mast cells (MCs)] or with MCTCs or mucosal phenotype mast cells (MCTs) stained for DAPI (nuclei) or using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay for apoptotic cells. Insets in lower panels showed TUNEL-positive stains in the nuclei. B: Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells, normalized to total number of nuclei. C: Quantitative RT-PCR for microvascular endothelial marker genes. n ≥ 4. ∗P < 0.05 (t-test) control VEGFR2 expression versus MCTs co-cultured. Scale bars = 100 μm.

References

- 1.Abman S.H., Bancalari E., Jobe A. The evolution of bronchopulmonary dysplasia after 50 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:421–424. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201611-2386ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jobe A.H. The new bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:167–172. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283423e6b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenmark K.R., Abman S.H. Lung vascular development: implications for the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:623–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.102229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kair L.R., Leonard D.T., Anderson J.M. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Rev. 2012;33:255–264. doi: 10.1542/pir.33-6-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baraldi E., Filippone M. Chronic lung disease after premature birth. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1946–1955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra067279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bose C.L., Dammann C.E., Laughon M.M. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and inflammatory biomarkers in the premature neonate. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93:F455–F461. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.121327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jo H.S., Cho K.H., Cho S.I., Song E.S., Kim B.I. Recent changes in the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia among very-low-birth-weight infants in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(Suppl 1):S81–S87. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.S1.S81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abman S.H. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1755–1756. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2109111c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt A.J., Pryhuber G.S., Huyck H., Watkins R.H., Metlay L.A., Maniscalco W.M. Disrupted pulmonary vasculature and decreased vascular endothelial growth factor, Flt-1, and TIE-2 in human infants dying with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1971–1980. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2101140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharya S., Go D., Krenitsky D.L., Huyck H.L., Solleti S.K., Lunger V.A., Metlay L., Srisuma S., Wert S.E., Mariani T.J., Pryhuber G.S. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling reveals connective tissue mast cell accumulation in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:349–358. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0406OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallgren J., Gurish M.F. Mast cell progenitor trafficking and maturation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;716:14–28. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-9533-9_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nilsson G., Dahlin J.S. New insights into the origin of mast cells. Allergy. 2019;74:844–845. doi: 10.1111/all.13668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grootens J., Ungerstedt J.S., Nilsson G., Dahlin J.S. Deciphering the differentiation trajectory from hematopoietic stem cells to mast cells. Blood Adv. 2018;2:2273–2281. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018019539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collington S.J., Williams T.J., Weller C.L. Mechanisms underlying the localisation of mast cells in tissues. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cildir G., Pant H., Lopez A.F., Tergaonkar V. The transcriptional program, functional heterogeneity, and clinical targeting of mast cells. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2491–2506. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dwyer D.F., Barrett N.A., Austen K.F., Immunological Genome Project Consortium Expression profiling of constitutive mast cells reveals a unique identity within the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:878–887. doi: 10.1038/ni.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh F.H., Sharma P., Gibbons A., Goggans T., Erzurum S.C., Haque S.J. Human airway epithelial cell determinants of survival and functional phenotype for primary human mast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14380–14385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503948102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wernersson S., Pejler G. Mast cell secretory granules: armed for battle. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:478–494. doi: 10.1038/nri3690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xing W., Austen K.F., Gurish M.F., Jones T.G. Protease phenotype of constitutive connective tissue and of induced mucosal mast cells in mice is regulated by the tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14210–14215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111048108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galli S.J., Borregaard N., Wynn T.A. Phenotypic and functional plasticity of cells of innate immunity: macrophages, mast cells and neutrophils. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/ni.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahlin J.S., Hallgren J. Mast cell progenitors: origin, development and migration to tissues. Mol Immunol. 2015;63:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veerappan A., Thompson M., Savage A.R., Silverman M.L., Chan W.S., Sung B., Summers B., Montelione K.C., Benedict P., Groh B., Vicencio A.G., Peinado H., Worgall S., Silver R.B. Mast cells and exosomes in hyperoxia-induced neonatal lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;310:L1218–L1232. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00299.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douaiher J., Succar J., Lancerotto L., Gurish M.F., Orgill D.P., Hamilton M.J., Krilis S.A., Stevens R.L. Development of mast cells and importance of their tryptase and chymase serine proteases in inflammation and wound healing. Adv Immunol. 2014;122:211–252. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800267-4.00006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gosman M.M., Postma D.S., Vonk J.M., Rutgers B., Lodewijk M., Smith M., Luinge M.A., Ten Hacken N.H., Timens W. Association of mast cells with lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2008;9:64. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansbro P., Beckett E., Stevens R., Jarnicki A., Kim R., Hanish I., Hansbro N., Deane A., Keely S., Horvat J., Yang M., Oliver B., van Rooijen N., Inman M., Adachi R., Soberman R., Hamadi S., Wark P., Foster P. A short-term model of COPD identifies a role for mast cell tryptase (P3242) J Immunol. 2013;190(1 Suppl):136.3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soltani A., Ewe Y.P., Lim Z.S., Sohal S.S., Reid D., Weston S., Wood-Baker R., Walters E.H. Mast cells in COPD airways: relationship to bronchodilator responsiveness and angiogenesis. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1361–1367. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00084411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berger P., Girodet P.O., Begueret H., Ousova O., Perng D.W., Marthan R., Walls A.F., Tunon de Lara J.M. Tryptase-stimulated human airway smooth muscle cells induce cytokine synthesis and mast cell chemotaxis. FASEB J. 2003;17:2139–2141. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0041fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thebaud B., Ladha F., Michelakis E.D., Sawicka M., Thurston G., Eaton F., Hashimoto K., Harry G., Haromy A., Korbutt G., Archer S.L. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene therapy increases survival, promotes lung angiogenesis, and prevents alveolar damage in hyperoxia-induced lung injury: evidence that angiogenesis participates in alveolarization. Circulation. 2005;112:2477–2486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.541524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao J., Guihard P.J., Wu X., Blazquez-Medela A.M., Spencer M.J., Jumabay M., Tontonoz P., Fogelman A.M., Bostrom K.I., Yao Y. Vascular endothelium plays a key role in directing pulmonary epithelial cell differentiation. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:3369–3385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201612122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herriges M., Morrisey E.E. Lung development: orchestrating the generation and regeneration of a complex organ. Development. 2014;141:502–513. doi: 10.1242/dev.098186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parera M.C., van Dooren M., van Kempen M., de Krijger R., Grosveld F., Tibboel D., Rottier R. Distal angiogenesis: a new concept for lung vascular morphogenesis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L141–L149. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00148.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laidlaw T.M., Steinke J.W., Tinana A.M., Feng C., Xing W., Lam B.K., Paruchuri S., Boyce J.A., Borish L. Characterization of a novel human mast cell line that responds to stem cell factor and expresses functional FcepsilonRI. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1101. e1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye L., Martin T.A., Parr C., Harrison G.M., Mansel R.E., Jiang W.G. Biphasic effects of 17-beta-estradiol on expression of occludin and transendothelial resistance and paracellular permeability in human vascular endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:362–369. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubota S.I., Takahashi K., Nishida J., Morishita Y., Ehata S., Tainaka K., Miyazono K., Ueda H.R. Whole-body profiling of cancer metastasis with single-cell resolution. Cell Rep. 2017;20:236–250. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bankova L.G., Dwyer D.F., Liu A.Y., Austen K.F., Gurish M.F. Maturation of mast cell progenitors to mucosal mast cells during allergic pulmonary inflammation in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;8:596. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitamura Y., Shimada M., Hatanaka K., Miyano Y. Development of mast cells from grafted bone marrow cells in irradiated mice. Nature. 1977;268:442–443. doi: 10.1038/268442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Souza Junior D.A., Santana A.C., da Silva E.Z., Oliver C., Jamur M.C. The role of mast cell specific chymases and tryptases in tumor angiogenesis. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:142359. doi: 10.1155/2015/142359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doggrell S.A., Wanstall J.C. Vascular chymase: pathophysiological role and therapeutic potential of inhibition. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:653–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He S., Aslam A., Gaca M.D., He Y., Buckley M.G., Hollenberg M.D., Walls A.F. Inhibitors of tryptase as mast cell-stabilizing agents in the human airways: effects of tryptase and other agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 2 on histamine release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:119–126. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heuston S., Hyland N.P. Chymase inhibition as a pharmacological target: a role in inflammatory and functional gastrointestinal disorders? Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:732–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffmann J., Yin J., Kukucka M., Yin N., Saarikko I., Sterner-Kock A., Fujii H., Leong-Poi H., Kuppe H., Schermuly R.T., Kuebler W.M. Mast cells promote lung vascular remodelling in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1400–1410. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00043310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metcalfe D.D., Mekori Y.A. Pathogenesis and pathology of mastocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2017;12:487–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-052016-100312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russo A., Russo G., Peticca M., Pietropaolo C., Di Rosa M., Iuvone T. Inhibition of granuloma-associated angiogenesis by controlling mast cell mediator release: role of mast cell protease-5. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:24–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Theoharides T.C., Valent P., Akin C. Mast cells, mastocytosis, and related disorders. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:163–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1409760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Souza Junior D.A., Borges A.C., Santana A.C., Oliver C., Jamur M.C. Mast cell proteases 6 and 7 stimulate angiogenesis by inducing endothelial cells to release angiogenic factors. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wimazal F., Jordan J.-H., Sperr W.R., Chott A., Dabbass S., Lechner K., Horny H.P., Valent P. Increased angiogenesis in the bone marrow of patients with systemic mastocytosis. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1639–1645. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61111-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ribatti D., Nico B., Maxia C., Longo V., Murtas D., Mangieri D., Perra M.T., De Giorgis M., Piras F., Crivellato E., Sirigu P. Neovascularization and mast cells with tryptase activity increase simultaneously in human pterygium. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:585–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vartio T., Seppä H., Vaheri A. Susceptibility of soluble and matrix fibronectins to degradation by tissue proteinases, mast cell chymase and cathepsin G. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dudeck A., Köberle M., Goldmann O., Meyer N., Dudeck J., Lemmens S., Rohde M., Roldán N.G., Dietze-Schwonberg K., Orinska Z., Medina E., Hendrix S., Metz M., Zenclussen A.C., von Stebut E., Biedermann T. Mast cells as protectors of health. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(Suppl):S4–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ribatti D., Contino R., Quondamatteo F., Formica V., Tursi A. Mast cell populations in the chick embryo lung and their response to compound 48/80 and dexamethasone. Anat Embryol. 1992;186:241–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00174145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abraham D., Oster H., Huber M., Leitges M. The expression pattern of three mast cell specific proteases during mouse development. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:732–740. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J.Y., Choi J.S., Song S.H., Im J.E., Kim J.M., Kim K., Kwon S., Shin H.K., Joo C.K., Lee B.H., Suh W. Stem cell factor is a potent endothelial permeability factor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1459–1467. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wallez Y., Vilgrain I., Huber P. Angiogenesis: the VE-cadherin switch. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto H., Ehling M., Kato K., Kanai K., van Lessen M., Frye M., Zeuschner D., Nakayama M., Vestweber D., Adams R.H. Integrin beta1 controls VE-cadherin localization and blood vessel stability. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6429. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takai S., Jin D., Miyazaki M. Multiple mechanisms for the action of chymase inhibitors. J Pharmacol Sci. 2012;118:311–316. doi: 10.1254/jphs.11r11cp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Human lung epithelial cells induce a mucosal-like phenotype in human mast cells. The human mast cell line (LUVA) was exposed to the human bronchial epidermal (16HBE) human lung airway–like epithelial cell line and then assessed for mast cell–specific protease expression at the mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels. A: A three-dimensional scattered plot indicating relative expression levels of CMA1, CPA3, and TPSB2 mRNA level. The color indicates the subtype score of each sample determined by fold change of TPSB2 divided by the product of CMA1 and CPA3 fold change. Epithelial cell exposure leads to a mucosal-like mast cell (MCT) phenotype with low CMA1, low CPA3, and high TPSB2. This phenotypic change persisted for >2 days after removal of epithelial cells/conditioned medium. B: Western blot analysis of cell lysates from LUVAs cultured alone [connective tissue phenotype mast cell (MCTC)] or co-cultured with 16HBEs (MCT). n = 3 (and in triplicates).

Von Willebrand factor (VWF) staining reveals microvascular dysmorphism in the developing lung. Representative images of embryonic mouse lung tissue explant cultured for 48 hours alone [no mast cells (MCs) (control)] or with connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) or mucosal phenotype mast cells (MCTs). The microvasculature was stained with VWF antibody (red), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). n = 5 in duplicates. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Connective tissue phenotype mast cells (MCTCs) do not induce endothelial cell apoptosis. A: Representative images of embryonic mouse lung tissue explant cultured for 48 hours alone [no mast cells (MCs)] or with MCTCs or mucosal phenotype mast cells (MCTs) stained for DAPI (nuclei) or using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay for apoptotic cells. Insets in lower panels showed TUNEL-positive stains in the nuclei. B: Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells, normalized to total number of nuclei. C: Quantitative RT-PCR for microvascular endothelial marker genes. n ≥ 4. ∗P < 0.05 (t-test) control VEGFR2 expression versus MCTs co-cultured. Scale bars = 100 μm.