Abstract

Background:

Kratom, a tree native to Southeast Asia, is increasingly used in Western countries for self-treatment of pain, psychiatric disorders, and mitigation of withdrawal symptoms from drugs of abuse. Because kratom is solely supplied from its native locations, supply shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic may impact the availability of preparations and hence force consumers to change their patterns of use. The aim of this study was to understand if and how COVID-19 was influencing kratom purchasing and use.

Methods:

Additional questions specific to kratom availability and changes in use during COVID-19 were added to an international online survey with responses collected between January and July 2020. During the same period, kratom-related social media posts to Twitter, Reddit, and Bluelight were analyzed for themes similar to the survey questions.

Results:

The survey results indicated no changes in kratom use patterns although the sample size was relatively small (n=70) with younger consumers reporting a potential issue in obtaining their desired products from their usual sources. The survey respondents identified primarily as non-Hispanic white (87.1%). Social media themes revolved primarily around quitting kratom during COVID-19, misinformation about the effects of kratom COVID-19, and other non-COVID related discussions. While some consumers may increase their kratom dose because of additional stress, a majority of discussions centered around reducing or rationing kratom due to COVID-19 or a perceived dependence. Access to quality kratom products was also a major discussion topic on social media

Conclusions:

Kratom use patterns did not change due to COVID-19 but consumers were concerned about potential product shortages and resulting quality issues. Clinicians and public health officials need to be informed and educated about kratom use as a potential mitigation strategy for substance use disorders and for self-treatment of pain.

Keywords: Kratom, COVID-19, Social media, Use patterns

Introduction

Background

The leaves of the Kratom tree (Mitragyna speciosa, Rubiacaea), which is native to Southeast Asia, have a long traditional use as both a stimulant, analgesic, and for a range of other ailments.1–4 In recent years, various leaf preparations have become popular in the US and globally due to their perceived analgesic and opioid-like effects.5–9 Based on national representative surveys between 0.7–6.1% of US adults report kratom use during their lifetime or in the past year.10–12 A majority of people appear to use kratom preparations to self-treat pre-existing conditions such as chronic pain, neuropsychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety, PTSD, ADHD, etc.), or manage withdrawal symptoms from illicit or prescription drugs, primarily opioids.5,13–17 Kratom’s leaves contain the indole alkaloids mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine, among others, that interact with the μ-opioid receptor as partial biased agonists without recruiting β-arrestin.9,18 This may explain the less severe respiratory depression and other adverse effects reported by kratom using-adults, as activation of the β-arrestin pathway is associated with many of the adverse effects typical of classical opioids, such as morphine, oxycodone, or fentanyl.9,19–23

Despite its perceived beneficial effects, long-term kratom use has been associated with the development of tolerance and dependence, and case studies report kratom withdrawal symptoms similar to opioids that required treatment with buprenorphine and/or naloxone.24–28 Kratom remains differentially scheduled in various countries. In the US, the leaf or products containing kratom alkaloids are unregulated at the federal level while several other countries have placed kratom on controlled substances lists. Several US states have banned kratom preparations citing concerns of public health whereas others require labeling and GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) testing in order to meet quality standards.29 Given the ongoing global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, availability of kratom from its sources in Southeast Asia (primarily Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia) may contribute to supply shortages or disruptions in kratom leaves reaching distributors and, ultimately, consumers.

Aims

In order to explore the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic might be impacting kratom purchasing or use, we included questions regarding the pandemic on a large anonymous online survey about kratom that was being conducted between July 2019 and July 2020. The aims of the primary study were centered on correlations between co-use of kratom with other drugs, quality of life, and measures of mental health such as post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, depressive, and anxiety disorders, and pre-existing health conditions. For this sub-study specific to kratom purchasing and use during the pandemic, questions about the availability of kratom preparations and potential changes in kratom consumption and purchasing behaviors were added to the parent study survey in January 2020. Given the use of kratom by consumers to mitigate or self-treat a substance use disorder, among other conditions, a shortage in available kratom may negatively impact quality of life and current efforts to maintain sobriety.15,30 To supplement, and possibly provide support for, and greater contextualization of, some of our survey findings related to kratom use during the pandemic, we also analyzed social media posts pertaining to kratom and COVID-19 for the time period which survey data were being collected during the pandemic. By seeking out additional, publicly available, data sources for user-generated text about kratom during this time period we hoped to provide a more nuance understanding about this topic than could be gleaned from a self-reported survey alone. The ultimate aim of this sub-study, which comprised an addition to the international survey parent study (data forthcoming), was to understand if and how the COVID-19 pandemic was influencing kratom purchasing and use. A novel aspect of this study is the mixed methods approach to utilize both survey and social media data to gain a more comprehensive understanding of kratom use patterns.

Methods

Online survey setting, approval, and data collection

An online anonymous cross-sectional international survey was conducted between July 2019 and July 2020 of current kratom users. Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) was used to collect the data. The survey was available through various social media outlets following distribution to Facebook and Reddit group leaders and posted to the American Kratom Association website (https://www.americankratom.org/, no posts were sponsored or paid advertisements). Participants were offered no incentive to complete the survey. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida (IRB #2019–01121). Study participation was voluntary. Prior to beginning the survey, participants had to acknowledge they were 18 years or older. Kratom users are identified in the survey by asking the question: “How long has it been since you first consumed Kratom?”. Data analysis for this sub-study only includes completed responses for the survey section on COVID-19 that were added to the parent study survey in January 2020. This resulted in a total sample size of n=70, reflecting those who completed the COVID-19 section that was added at the beginning of the pandemic, out of a total of 4,945 completed surveys. Internet protocol addresses were not stored with the data but used to prevent multiple responses from the same device to ensure anonymity and prevent ballot stuffing.

Survey format

Demographic data (age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, country, employment status, and education) and COVID-related questions (availability of Kratom products, change in use habits, fears of kratom product shortage) were collected. Additional data was collected but not analyzed as part of this research question. The complete survey is attached as supplementary material.

Survey data analysis

Data were analyzed in Microsoft Excel 2013 (version 15.0, Microsoft, Seattle, WA) and GNU PSPP (http://www.gnu.org/software/pspp/, version 0.10.4-g50f7b7). Chi-square analysis was applied for level comparison among nominal and ordinal variables against expected values for goodness of fit (single variable Chi-square goodness of fit assuming equal counts for expected values). Binomial logistic regression was used to compare levels of variables against a reference level to obtain odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. For each logistic regression, all pertinent independent variables were included in the same model comparing all levels against each other (Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons among levels, post-survey power calculation resulted in at least 85% power and 93% confidence for all models).

Social media data collection

Prior to beginning social media data collection, the study team generated a list of a priori themes that were expected to be identified in online posts based on existing kratom literature that pre-dated COVID-19 (e.g., use as self-adopted harm-reduction method, use to mitigate opioid withdrawal symptoms, long-standing medicinal use in Asia),5,16,17,31 anecdotal accounts from kratom users obtained during the pandemic, and a warning letter issued by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to a kratom vendor who purported that kratom products were effective in treatment or prevention of COVID-19 (FDA, 2020; see Table S1 in Appendix A for a priori themes).

Social media posts made between March 1, 2020 to July 31, 2020 were collected as individual datasets. The following search strings were used during data collection: “coronavirus” and “kratom”, “corona virus” and “kratom”, “corona” and “kratom”, “covid-19” and “kratom”, “covid” and “kratom”, “pandemic” and “kratom”, “quarantine” and “kratom”, “social distancing” and “kratom”. Our initial plan was to attempt to obtain social media posts from the following sources: Reddit, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Bluelight. However, we were unable to obtain data from Facebook and Instagram due to a 2018 corporate policy change that restricts access to the application programming interface (API) for these sites and that would require informed consent from every individual person whose data we sought to include in our sample. Accordingly, we collected data from Reddit, Twitter, and Bluelight. These and similar sites permit exploration of available descriptive data on kratom including, in this case, the possibility to tap into self-report about kratom during COVID-19 in the form of user-generated posts.32–34 Reddit data, in particular, can be highly contextualized and have been used to gain insight about a wide range of topics.35–39

An R package was used to successfully collect, aggregate, and filter (e.g., remove automated, non-human “bot” posts) data from Reddit, Bluelight, and Twitter (see Appendix B for additional description of social media post data collection and handling methods). Upon first pass, 1,503 (NBluelight = 48, NReddit = 193, NTwitter = 1,259) posts were obtained, however a large portion of Twitter posts appeared to be automated “bot” posts from advertisers or other interest groups; 969 (77.1%) met criteria for being considered a “bot”. This determination was made using the “botometer”, a scoring system that calculates the probability of an automated Twitter account, providing a range from 0–1 with higher scores indicating greater likelihood of automation; an a priori score of 0.43 was used as a cutoff point per recommended guidelines.40 A total of 533 posts remained. After conducting a preliminary reading of the 533 posts to include only those that met the criteria of having both a kratom- and COVID-related keyword, 379 unique posts comprised the final sample.

Two researchers independently read through all compiled posts to identify naturally occurring themes. Upon discussion and review of themes that emerged through the first pass of the data, the research team conferenced and developed a codebook that included 20 unique thematic categories that would be used for subsequent coding (see Table 1), many of which were consonant with expected themes and several were novel or more nuanced than initially anticipated. Two raters (J.R. and K.S.) independently coded all posts using MAXQDA 2020 (VERBI Software, 2019).41 A code-specific results table of posts was generated to determine the frequency of occurrences for a given code as well as percent concordance versus discordance among raters across codes; the kappa statistic was used to compute the magnitude of interrater agreement with a range from −1 to +1, where 1 represents perfect agreement among raters.42,43 For transparency, all raw data and social media posts collected and coded for this study are available upon request.

Table 1.

Thematic Codes and Interrater Agreement.

| Thematic Code | Concordant | Discordant | Total | % Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Posts explicitly Covid-19 related

|

||||

| Quitting or reducing kratom use during COVID-19 | 96 | 24 | 120 | 80.00 |

| Misinformation about kratom as prevention or medically supported treatment for COVID-19 | 94 | 18 | 112 | 83.93 |

| Concern over perceived kratom availability due to pandemic effects or government interference | 70 | 17 | 87 | 80.46 |

| Kratom use to mitigate drug withdrawal | 54 | 19 | 73 | 73.97 |

| Counters to misinformation about kratom as prevention or medically supported treatment for COVID-19 | 60 | 17 | 77 | 77.92 |

| Questions & speculation about using Kratom to protect against or treat COVID-19 infection | 45 | 23 | 68 | 66.18 |

| Changes in kratom consumption or dosing behavior | 42 | 15 | 57 | 73.68 |

| Disruptions in kratom purchasing availability | 38 | 8 | 46 | 82.61 |

| Changes in kratom purchasing behavior | 26 | 10 | 36 | 72.22 |

| Opioid craving during COVID-19 | 33 | 5 | 38 | 86.84 |

| Kratom use due to restricted treatment access (e.g., opioid agonist therapy, detox services, general medical services, dentistry) | 22 | 4 | 26 | 84.62 |

| Kratom dosing routine disruptions | 4 | 4 | 8 | 50.00 |

| Concerns over kratom products being contaminated with COVID-19 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 80.00 |

| Changes in kratom purchasing location | 4 | 0 | 4 | 100.00 |

|

Posted during COVID-19 pandemic, but not all explicitly pandemic-related |

||||

| Kratom strains & dosing (e.g., giving advice, soliciting advice, providing update of dosing regimen) | 245 | 48 | 293 | 83.62 |

| Adverse kratom side effects or complaints (e.g., kratom dependence, tolerance, withdrawal, professed addiction) | 176 | 87 | 263 | 66.92 |

| Polydrug use (including concomitant use of kratom with other drugs) | 105 | 27 | 132 | 79.55 |

| Kratom as substitute for another drug | 46 | 16 | 62 | 74.19 |

| Kratom use to treat pain symptoms predating COVID-19 | 8 | 13 | 21 | 38.10 |

| Kratom use to treat symptoms (ADD/ADHD, anxiety depression) that predated COVID-19 | 12 | 10 | 22 | 54.55 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 1188 | 367 | 1555 | 76.40 |

Results

Anonymous online survey

The COVID-19 related questions from the online survey were available from January 2020 to July 2020 and provided a sample of n=70 completed responses out of a total of 4,945 completed responses over the entire course of the survey. A large number of responses were provided in the initial weeks following the availability or an announcement of the survey in July 2019 thus accounting for the small response quota by the time the COVID section was added in January 2020. Only completed surveys were included in the analysis of COVID-19 questions which reduced the sample size from 77 to 70. The COVID-19 related questions were analyzed by age, gender, marital status, and race/ethnicity to relate demographic variables to potential differences in COVID-19 behaviors and kratom use patterns.

The use patterns of kratom among respondents was lowest for self-treatment of misuse of another drug (15 or 19.5%) followed by self-treatment of a prescription medicine dependency or to replace such medications (25 or 32.5%). The use of kratom to self-treat an emotional or mental condition was indicated by 33 (42.9%) respondents while 54, or 70.1%, of respondents used kratom to self-treat acute or chronic pain conditions (Table 2). Respondents could choose to use kratom for multiple self-treatment conditions hence creating a complex user profile. Kratom was primarily obtained through legal means either online (56 or 72.7%) or in smartshops/smoke shops or alike venues (23 or 29.9%). No respondent obtained kratom from the clubbing scene and only one received it through an illegal dark web source.

Table 2.

Survey General Demographics and Kratom use patterns.

| Survey question | Answer | Responses (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Are you self-treating with Kratom to mitigate, enhance or reduce the effects of your concomitant misuse of another drug (e.g. heroin, cocaine, amphetamine, marijuana)? | Yes | 15 (19.5%) |

| No | 62 (80.5%) | |

| Are you self-treating with Kratom to mitigate, enhance or reduce the effects of a prescription medicine dependency or as a prescription medicine replacement (e.g. opioid pain killers (morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydrocodone), to replace methadone or other replacement therapy)? | Yes | 25 (32.5%) |

| No | 52 (67.5%) | |

| Are you self-treating with Kratom because of a medical condition leading to acute or chronic pain? | Yes | 54 (70.1%) |

| No | 23 (29.9%) | |

| Are you self-treating with Kratom because of an emotional/mental condition (e.g. anxiety, depression, PTSD)? | Yes | 33 (42.9%) |

| No | 44 (57.1%) | |

| If you have ever used or are currently using Kratom, what is/are your sources for obtaining Kratom (select all that apply)? | Food/Nutrition store | 7 (9.1%) |

| Online (legal) | 56 (72.7%) | |

| Darkweb (illegal) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| Friends/Family | 5 (6.5%) | |

| Smart shop or other shops | 23 (29.9%) | |

| Clubs/nightlife | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 8 (10.4%) | |

| How long has it been since you first consumed Kratom? | Less than 6 months | 14 (18.2%) |

| 6 months - 1 year | 14 (18.2%) | |

| 1–2 years | 26 (33.8%) | |

| 2–5 years | 18 (23.4%) | |

| more than 5 years | 5 (6.5%) | |

| What is the usual amount of Kratom you take/have taken per dose? | Less than 1 gram | 3 (3.9%) |

| 1–3 grams | 24 (31.2%) | |

| 3–5 grams | 17 (22.1%) | |

| 5–8 grams | 20 (26.0%) | |

| more than 8 grams | 5 (6.5%) | |

| I drink a prepared Kratom decoction | 4 (5.2%) | |

| I do not know | 4 (5.2%) | |

| How many times on average do you use/have used Kratom per day? | Less than once per day | 10 (13.0%) |

| Once per day | 10 (13.0%) | |

| 2 times/day | 23 (29.9%) | |

| 3 times/day | 14 (18.2%) | |

| 4 times/day | 8 (10.4%) | |

| More than 4 times/day | 6 (7.8%) | |

| I had sporadic use in the past | 6 (7.8%) | |

| Did you increase the regular dose of Kratom over the course of time? | Yes | 31 (40.3%) |

| No | 46 (59.7%) | |

| Have you taken/Are you taking Kratom in combination with other drugs/substances? | Yes | 20 (26.0%) |

| No | 57 (74.0%) |

A majority of respondents (63.7%) would be considered regular or chronic kratom users, having used kratom for at least one year (Table 2). Approximately half of respondents (53.3%) used between 1–5 grams of kratom product per dose while a third (32.5%) used more than 5 and even exceeding 8 gram per dose. Few respondents used less than 1 gram or a prepared kratom tea/decoction. Nearly half of respondents (48.1%) consumed kratom 2–3 times/day while fewer respondents (18.2%) consumed kratom more frequently than 2–3 times/day; 33.8% used kratom less frequently than 2–3 times/day. A kratom dose increase over time, with no time frame provided, was reported by 40.3% of respondents. Kratom was taken concomitantly or contemporaneously with other drugs, either in the past or currently, by 26% of respondents (Table 2).

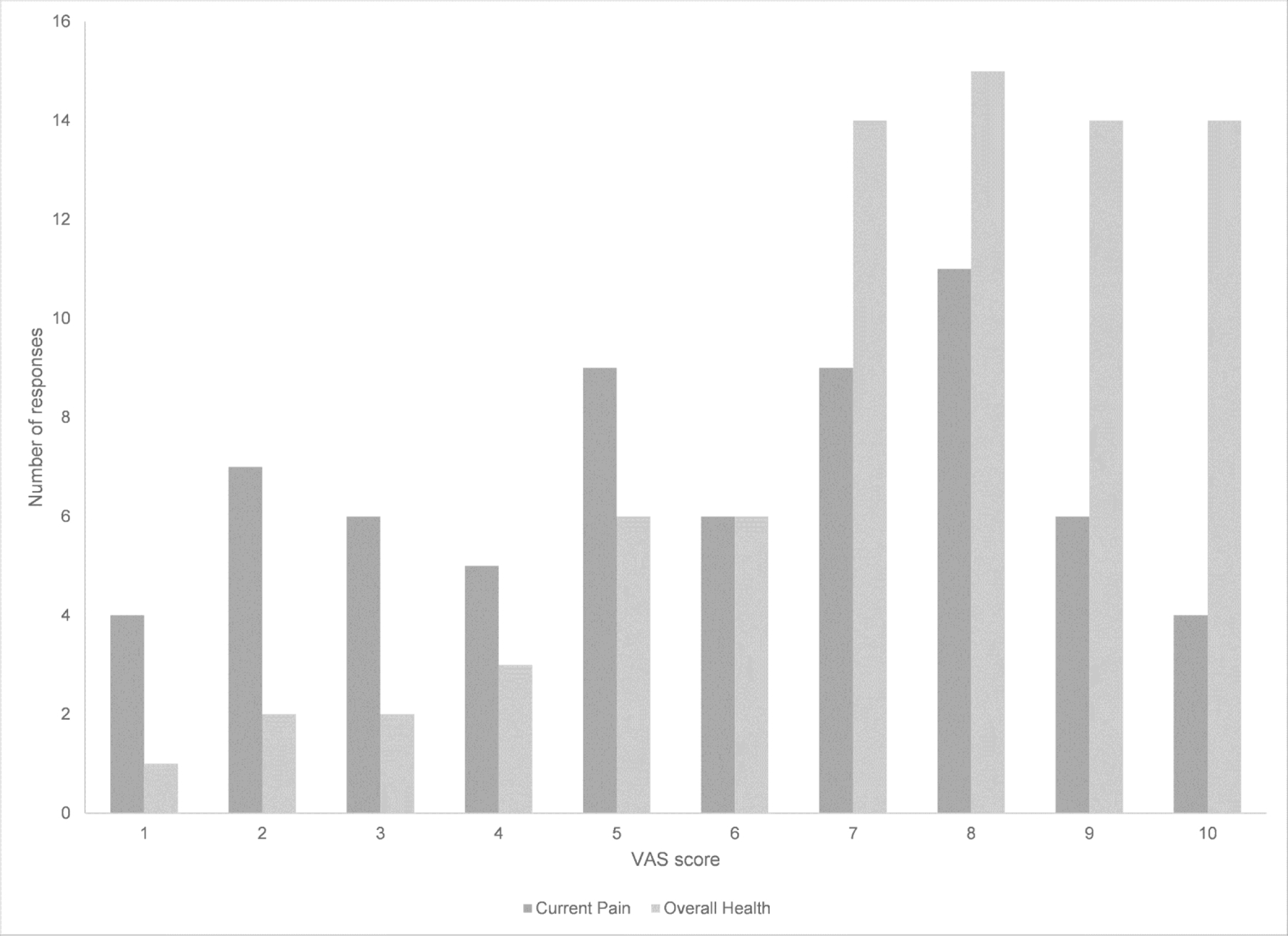

Current pain and overall health, evaluated using visual analogue scales (VAS), were binned into categories of 1-point increments (i.e. VAS scores between 0–1 fell into category 1, scores between 1.01–2 fell into category 2, etc.) (Figure 1). Current pain did not follow a particular trend towards higher or lower scores, with an average of 5.7 out of 10 and standard deviation of 2.64. Overall current health was skewed towards higher values indicating better health, with an average of 7.44 and standard deviation of 2.17.

Figure 1:

Visual Analogue Scale Binned Rating of current pain and overall health. For current pain, no pain is rated as 1 and worst imaginable pain as 10. For current overall health, 1 is rated as worst health and 10 is best health.

Current experiences with obtaining kratom products during the COVID-19 pandemic

A majority (62 or 88.5%) of respondents did not experience issues in obtaining their kratom products from their usual sources during this stage of the pandemic (Table 3). However, there was a significant difference (p=0.015) by age category with age groups 18–20 and 21–30 years experiencing a greater issue of kratom accessibility compared to older age groups. No significant differences in kratom access were found between respondents based on gender (p=0.811), marital status (p=0.636), or race/ethnicity (p=0.932) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Survey COVID-related questions.

| Have you or do you currently experience any issues in obtaining your Kratom products from your usual sources? | Do you fear that there may be a shortage of Kratom products should the global supply chain and Kratom economy be impacted by the novel coronavirus pandemic? | If you anticipated a potential shortage in Kratom supply, did you buy larger amounts from your usual sources in recent weeks or months? | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Sign. | Yes | Maybe | No | Sign. | Yes | No | I do not anticipate a Kratom supply shortage | Sign. | |

| Total | 8 (11.5%) | 62 (88.5%) | 24 (34.3%) | 29 (41.4%) | 17 (24.3%) | 27 (38.5%) | 35 (50%) | 8 (11.5%) | |||

| Age | |||||||||||

| 18–20 years | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.015 | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.124 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.632 |

| 21–30 years | 3 (4.3%) | 8 (11.4%) | 3 (4.3%) | 2 (2.9%) | 6 (8.6%) | 3 (4.3%) | 8 (11.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| 31–40 years | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (15.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | 4 (5.7%) | 5 (7.1%) | 4 (5.7%) | 4 (5.7%) | 3 (4.3%) | |||

| 41–50 years | 2 (2.9%) | 22 (31.4%) | 8 (11.4%) | 12 (17.1%) | 4 (5.7%) | 10 (14.3%) | 12 (17.1%) | 2 (2.9%) | |||

| 51–60 years | 2 (2.9%) | 9 (12.9%) | 4 (5.7%) | 6 (8.6%) | 1 (1.4%) | 5 (7.1%) | 4 (5.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | |||

| ≥61 years | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (17.1%) | 6 (8.6%) | 5 (7.1%) | 1 (1.4%) | 5 (7.1%) | 6 (8.6%) | 1 (1.4%) | |||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Female | 3 (4.3%) | 26 (37.1%) | 0.811 | 11 (15.7%) | 13 (18.6%) | 5 (7.1%) | 0.511 | 12 (17.1%) | 14 (20.0%) | 3 (4.3%) | 0.913 |

| Male | 5 (7.1%) | 36 (51.4%) | 13 (18.6%) | 16 (22.9%) | 12 (17.1%) | 15 (21.4%) | 21 (30.0%) | 5 (7.1%) | |||

| Marital status | |||||||||||

| Single/never married | 3 (4.3%) | 13 (18.6%) | 0.636 | 4 (5.7%) | 4 (5.7%) | 8 (11.4%) | 0.139 | 3 (4.3%) | 11 (15.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0.296 |

| Married | 2 (2.9%) | 31 (44.3%) | 9 (12.9%) | 18 (25.7%) | 6 (8.6%) | 11 (15.7%) | 17 (24.3%) | 5 (7.1%) | |||

| Partnered | 1 (1.4%) | 7 (10.0%) | 5 (7.1%) | 2 (2.9%) | 1 (1.4%) | 6 (8.6%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Divorced | 2 (2.9%) | 9 (12.9%) | 5 (7.1%) | 4 (5.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | 6 (8.6%) | 4 (5.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | |||

| Widowed | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.9%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||||

| Black or African-American | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0.932 | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0.074 | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.552 |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (4.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.9%) | 1 (1.4%) | |||

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 8 (11.4%) | 53 (75.7%) | 24 (34.3%) | 24 (34.3%) | 13 (18.6%) | 25 (35.7%) | 30 (42.9%) | 6 (8.6%) | |||

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | |||

| Do not wish to answer | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

Perceived future availability of kratom products and purchasing behavior

Two questions asked respondents to speculate about the possible impact of COVID-19 on future shortages in the global kratom product supply chain and if such anticipated shortages might influence them to change their purchasing behavior and stockpile a kratom supply. Overall, approximately one-third of respondents (24 or 34.3%) feared that there may be future shortages in the global kratom supply chain due to COVID-19 whereas 29, or 41.4%, responded with “maybe” and 17 (24.3%) responded with “no” (Table 3). There were no significant differences by age (p=0.124), gender (p=0.511), marital status (p=0.139), or race/ethnicity (p=0.074). Half of the respondents did not change their kratom purchasing behavior while 27, or 38.6%, did buy larger amounts from their usual sources in recent weeks or months and 8, or 11.4%, did not anticipate a kratom supply shortage (Table 3). No significant differences were found based on age (p=0.632), gender (p=0.913), marital status (p=0.296), or race/ethnicity (p=0.552). Of note, the sample was overwhelmingly composed of white, non-Hispanic respondents (61 or 87.1%).

Changes in kratom consumption behavior due to COVID-19

A majority of respondents (ranging from 72.2% for single/never married to 100% for e.g. ages 61 years and older) did not report changing their kratom consumption behavior due to COVID-19 (Table 4). Any deviations from consumption solely occurred among white non-Hispanic respondents of which 8, or 12.7%, took more kratom to alleviate stress and/or psychiatric disorder symptoms. Only 1, or 1.6%, among white non-Hispanic respondents consumed more kratom to mitigate withdrawal symptoms from an opioid medication while 2, or 3.2%, consumed kratom to prevent an infection with the novel coronavirus (COVID-19).

Table 4.

Survey COVID-related changes in Kratom use question.

| Have you been changing your consumption behavior or reason(s) for taking Kratom since the novel coronavirus global pandemic affected your area (select all that apply)? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, I consume Kratom to prevent an infection with the novel coronavirus. | Yes, I consume more Kratom to alleviate stress and/or emotional disorders. | Yes, I consume more Kratom to mitigate withdrawal symptoms from an opioid medication. | No, I have not changed my consumption behavior or reason(s) for taking Kratom. | |

| Age | ||||

| 18–20 years | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100.0%) |

| 21–30 years | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (75.0%) |

| 31–40 years | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (81.8%) |

| 41–50 years | 1 (4.0%) | 3 (12.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 21 (84.0%) |

| 51–60 years | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (9.1%) | 9 (81.8%) |

| ≥ 61 years | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (100.0%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1 (3.3%) | 4 (13.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | 24 (80.0%) |

| Male | 1 (2.4%) | 4 (9.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 37 (88.1%) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single/never married | 2 (11.1%) | 3 (18.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (72.2%) |

| Married | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 32 (97.0%) |

| Partnered | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 6 (75.0%) |

| Divorced | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (72.7%) |

| Widowed | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (100.0%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Black or African-American | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (100.0%) |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 2 (3.2%) | 8 (12.7%) | 1 (1.6%) | 52 (82.5%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (100.0%) |

| Do not wish to answer | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100.0%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (100.0%) |

Social media posts

The majority of coded posts came from Twitter (n=193), followed by reddit (n=147), and Bluelight (n=39). Reddit posts originated from 34 unique subreddits, but most prominent among these were subreddits dedicated to kratom discussion (n=93). Of these, 64 posts came from subreddits on quitting kratom use. Posts made between March 1, 2020 and July 31, 2020 fell along two general types: those made during the pandemic that were able to be tied directly to COVID-19, and those that while made during the specified dates did not always explicitly relate to the pandemic, but instead segued between descriptions of activity that seemed to occur both before and during the global onset of COVID-19. This was particularly true for Reddit posts, which were longer and often provided detailed histories of kratom use, other drug use regimens, myriad psychological and physical health descriptions, and personal anecdotes (e.g., jobs, relationships, treatment experiences). These posts describing prior or intermittent states, behaviors, or experiences, were often contained within the same post describing similar or related descriptions that were contemporaneous or coincident with COVID-19.

Social media posts explicitly related to COVID-19

Table 1 displays all themes that were coded, the interrater agreements vs. disagreements, and agreement percent. Table S2 in supplementary materials displays the chance-corrected Kappa coefficient, calculated to help reduce the proportion of agreement which might be assigned to coded segments by chance.42 A total of 1,555 unique codes were made, of which 1,188 were concordant and 367 were discordant, resulting in a 76.40% rate of interrater agreement. Corrected Kappa for interrater agreement was 0.75, which, like other variations of Cohen’s K, can be interpreted similarly, indicating that the interrater agreement here is moderate to substantial.44,45 The matrix displayed in Table 5 gives the number of posts in which two themes co-occurred.

Table 5.

Number of times codes co-occur in social media posts.

| Code System | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Quitting during COVID-19 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Misinformation about kratom for COVID-19 | 3 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Concern over kratom availability | 6 | 4 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Kratom use to mitigate drug withdrawal | 9 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Counters to misinformation | 2 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Questions about COVID-19 infection | 7 | 23 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| 7. Changes in kratom consumption | 18 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||

| 8. Disruptions in kratom purchasing availability | 14 | 0 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| 9. Changes in kratom purchasing | 5 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 0 | |||||||||||

| 10. Opioid craving during COVID-19 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 11. Kratom use due to restricted med access | 2 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |||||||||

| 12. Kratom dosing routine disruptions | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||

| 13. Kratom contaminated with COVID-19 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| 14. Changes in kratom purchasing location | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| 15. Kratom strains & dosing | 73 | 11 | 13 | 34 | 3 | 17 | 35 | 21 | 11 | 10 | 18 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | |||||

| 16. Adverse kratom side effects | 91 | 4 | 9 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 18 | 9 | 17 | 7 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 109 | 0 | ||||

| 17. Polydrug use | 32 | 2 | 4 | 27 | 0 | 3 | 18 | 15 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 66 | 51 | 0 | |||

| 18. Kratom as substitute for another drug | 21 | 4 | 4 | 25 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 24 | 25 | 0 | ||

| 19. Kratom to treat pain symptoms | 3 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | |

| 20. Kratom to treat psychiatric symptoms | 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

Among posts that were explicitly or more directly COVID-19-related, the most common theme identified was “Quitting or reducing kratom during COVID-19” (n=120), most often represented by posts among individuals who were seeking to quit during the pandemic, either because they had previously considered stopping their kratom use or because they anticipated that the pandemic would force them into withdrawal. Others who discussed quitting kratom did so out of concern for contracting COVID-19, due primarily to fears that continuing their kratom regimen could make possible COVID-19 infection worse, concerns about what kratom withdrawal would be like if infected and/or hospitalized, or because of general worries regarding kratom supply disruption that would have the potential to induce unwanted kratom withdrawal. This is evidenced by another frequently occurring theme, “Concern over perceived kratom availability due to the pandemic effects or government interference” (n=87). The finding of quitting or reducing kratom use during the pandemic in social media posts was perhaps the greatest difference than data collected via the survey in that the survey did not specifically ask about intentions or perceived need to quit or reduce kratom during COVID-19. Yet, similar to survey findings, we did not find that a majority of people described changes in consumption, dosing, or purchasing behavior (e.g., stockpiling) nor disruptions in kratom availability.

Although most of these posts expressed anxiety about the pandemic disrupting kratom availability, some hinted that government agencies, such as FDA, would use the pandemic as an opportunity to halt kratom shipments into the US. While these were a minority of posts, a related theme was more common, namely “Misinformation about kratom as prevention or medically supported treatment for COVID-19” (n=112). Prominent among these posts were ideas that kratom may have immune-boosting or anti-inflammatory properties that would be protective against many infections, including possibly COVID-19, and that kratom use could actually help against a pulmonary infection in particular. These posts were similar and more closely related, but still distinct from, those which comprised the theme “Questions and speculation about using Kratom to protect against or treat COVID-19 infection” (n=68). Here, curiosity and equivocation of opinion about the benefits or risks of kratom use during the COVID-19 era were expressed, leaving it as an open question as to whether kratom could actually be protective or curative. Also prominent, but standing in no relation to these prior themes, was “Counters to misinformation about kratom as prevention or medically supported treatment for COVID-19” (n=77), with posts either explicitly denouncing unfounded speculations, suggesting that there is no evidence for such claims, or using humor to publicly shame individuals who expressed ideas of kratom as a panacea.

“Changes in kratom consumption or dosing behavior”, “Disruptions in kratom purchasing availability”, and “Changes in kratom purchasing behaviors” occurred at similar frequencies, with the latter characterized by two extremes: kratom hoarding or stockpiling and descriptions of difficulties purchasing due to lost income or access. Dosing behavior changes were often associated with increased use due to pandemic-related stress or increased recreational time and a desire to relax or even enjoy oneself during lockdowns or quarantine. “Kratom use to mitigate drug withdrawal” occurred at high rates (n=73) and in the context of several licit and illicit drugs or supplements, including alcohol, buprenorphine (both prescribed and diverted), prescription opioids, products marketed as “nootropics” (e.g., tianeptine sodium/sulfate salt, phenibut), and gabapentin. Kratom use, for some, was directly attributable to restricted access to opioid agonist therapy or basic medical services (n=26), though this occurred at lower rates than were expected. Some people described difficulty accessing illicit opioids and expressed increased opioid craving during the pandemic.

Social media posts during COVID-19 not always explicitly tied to pandemic

For all posts, the most frequently occurring theme (n=293) was “kratom strains and dosing” which was comprised of soliciting or giving of advice and/or descriptions of one’s dosing regimen, including updates about dosing over time. As shown in Table 1, this theme often occurred within posts also pertaining to quitting or reducing kratom during COVID-19 and the more temporally diffuse themes: “Polydrug use” (n=132), “kratom as substitute for another drug” (n=62), and “Adverse kratom side effects or complaints” (n=263). Oftentimes, language about strain or dosing was intermingled within long posts also describing the perceived need to use kratom to mitigate withdrawal from another drug, substitute kratom for another drug, or use kratom as part of a larger, complex pattern of polydrug use. The latter sometimes manifested in terms of recreation or to achieve a euphoric “high”, but more often pertained to using to obtain relief from kratom and other drug withdrawal and to sustain (or regain) capacity for daily functioning that was believed by many to be achieved by maintaining the correct kratom dosing regimen (which often included concomitant use with other substances). The desire to simply “feel better” or “not feel worse” was frequently expressed and clearly divorced from posts describing hedonic pursuits. In part, the former was represented in the themes of “kratom use to treat symptoms that existed prior to and during COVID-19” (e.g., anxiety, depression, attention deficit disorder, or pain; n=43). The second most common theme found across all posts, “adverse effects of kratom”, was comprised of primarily four subthemes: Kratom dependence, withdrawal, tolerance, and/or professed addiction. This partially explains its fairly robust relation to the theme of “quitting kratom” as many people described a desire to end their relationship with kratom due to the preponderance of what they perceived to be unsustainable negative consequences (e.g., dependence, burden of dosing multiple times a day, smell and taste of kratom powder, etc.). Adverse effects from kratom were discussed fluidly in past and present tense and even discussed in prospective terms among those who had already quit using kratom but who openly weighed the undesirable consequences that they believed would manifest if they resumed use.

Discussion

Kratom use remains essential for many during COVID-19

Although the sample size for the COVID-19 related survey questions was small, it provides an insight on how kratom users perceive and adapted to the global pandemic. The overall use patterns do reflect kratom use from larger surveys with a majority of users self-treating acute and chronic pain conditions (68–91%).5,16 One deviation in this sample was the comparably low number of respondents using kratom to self-treat mental and/or psychiatric conditions or symptoms, which is usually as high as the use for acute or chronic pain (66–96%).5,16,17 The continued high use of kratom to self-treat pain may support its potential effectiveness as an analgesic and benefit as an alternative to other analgesic drugs such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and, more importantly, opioids. It is not always apparent if kratom is taken to avoid the initial use of opioids or their replacement but independent of that kratom is consistently used to self-treat pain according to surveys. Furthermore, in addition to survey data at least one human clinical trial supports the analgesic effects of kratom in doses equivalent to those commonly reported in surveys.23,46

A majority of respondents are obtaining their kratom from legal online or local smoke/smart shops (similar to tobacco and herb shops). This finding agrees with surveys and indicates that people using kratom do not necessarily seek out illegal drug sources because they are able to obtain kratom legally in their respective communities.5,16 This may reduce the risk of people consuming adulterated or contaminated substances, although many countries provide little regulatory oversight of kratom product quality or labeling.47 Likewise, despite increasing self-regulation among kratom vendors, some kratom products purchased in the US have been associated with adulteration, contamination, and insufficient regulation of the alkaloid content to ensure consumer safety and product quality and consistency.29,48–50 Even if kratom users are able to obtain their preferred products, they may not always receive consistent product quality and content, which could contribute to experimentation in dose escalation and concomitant use with other drugs/substances. Kratom may often serve the purpose of mitigating the withdrawal effects of other drugs that were initially taken concomitantly, especially opioids and stimulants, based on its own central stimulant and depressant effects.8,14,23,51,52 Such concomitant kratom use has remained similar during COVID-19 emphasizing the role kratom may play in maintaining substance use regimens, preventing relapse to illicit drugs, and permitting continued self-treatment of chronic conditions for which patients may not seek counseling or prescription drugs, limitations to treatment access for specific conditions during COVID-19, or who may experience barriers when trying to access medical care.

Similar to other surveys, a majority of respondents are chronic, long-term consumers of kratom, using over one year. Approximately half of respondents reported kratom doses between 1–5 grams which were associated with lower risk of adverse effects in prior surveys compared to higher doses (above 5 grams) while perceived benefits were well received in this dose range.5,6,16,17 Similarly, a majority of respondents reported taking 2–3 kratom doses per day, which echoes findings from surveys and small observational studies that indicate an effect duration of between 3–6 hours for kratom preparations for a range of self-treatment indications.5,23 Because kratom dose and frequency of use remain similar in this sub-analysis compared to prior surveys, it does not appear that COVID-19 was impacting kratom use patterns during the time our sub-study collected survey data for. However, the findings suggest that kratom remains an essential substance among people using for a variety of health-related indications.

Survey points to unchanged perceived availability and use of kratom during COVID-19

While younger kratom users may have temporarily experienced issues obtaining their preferred kratom products from their usual sources, no other demographic variables were indicative of a change in purchasing behavior. The perception of kratom users of a shortage in product availability in the future did lead 38.6% to stock up. This behavior is not unusual and has been observed for other products considered essential. It also may indicate a divergent use pattern of kratom products by age.

Social media snapshot of kratom during rapidly changing and uncertain times

Overall, posts provided support for many survey findings regarding motivations for using kratom, including substitution for another substance or to self-treat pain or psychiatric symptoms as well as kratom in the context of the pandemic. Similarly, the majority of social media text indicated similar dosing ranges and indicators of regular, versus intermittent kratom use, which is somewhat intuitive given that people self-selected into communities discussing a very particular topic (kratom) at a very particular moment (COVID-19). However, the posts we examined contained information about quitting or reducing kratom during COVID-19 not captured via survey. Similar to the survey, evidence of polysubstance that included use of kratom and another drug were found, but did not comprise the majority. Unlike the survey, we found extensive examples of people seeking or providing very specific types of advice about kratom and kratom dosing, which is perhaps a natural artifact of a sample of social media posts. This specific element of peer-to-peer information sharing was not a survey item, but does underscore the community of online kratom users that exists and which warrants greater study.

Taken together, social media posts examined revealed three primary findings. First, kratom use can be considered a typical or routine aspect of daily living for many of the people who posted, particularly those posting to Reddit or Bluelight. Second, like nearly all other typical or routine aspects of daily life, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted, or has been perceived as threatening to disrupt, kratom use among those who may be best characterized as regular or chronic users. Although some people purported to increase use due to pandemic-related stress, many more viewed the pandemic as a force that might necessitate kratom abstinence or decreased use, including rationing their supply. For some, COVID-19 revealed a degree of dependence they did not realize they had, with some perceiving pandemic-related conditions (e.g., telework, being laid off or furloughed, isolated at home due to shelter-in-place orders) as an opportunity to quit or reduce use. Although kratom dependence and withdrawal were discussed separately from the pandemic by some, for others the beginning of COVID-19 brought anticipation or fear of kratom withdrawal to the fore. Third, COVID-19 conditions disrupted other drug use regimens, including regular use or misuse of a range of licit and illicit substances, primarily opioids, but also GABAergic drugs and questionable supplements or products marketed as cognitive-enhancing “nootropics”. In so doing, many people sought information about kratom during the early months of the pandemic as a way to mitigate active or anticipated withdrawal. Although the reasons for withdrawal were not always clear, some specified inability to access OAT due to initial treatment disruptions and inability to acquire their usual illicit drugs due to illicit market disruptions and price gouging by drug dealers (at least during the early days of the pandemic). The posts reveal that the lives of many people posting about kratom use or kratom cessation were complicated, in part due to the fact that they had many conditions or prior conditions that they believed required kratom self-treatment and/or other substance use. They also revealed that the pandemic and its many uncertainties was making their lives more complicated, stressful, and uncertain.

Enduring complexities of kratom use

More broadly, many posts provided further evidence that some, irrespective of COVID-19, relied on kratom to self-treat pain, serve as a drug substitute, or ameliorate psychiatric symptoms, findings which have been observed across multiple self-report studies.2,4,5,13–17,31,53 Many of these posts also reveal the extent to which the online kratom-using community relies on mutual support and information-sharing among peers, perhaps indirectly indicating the lack of availability of scientific data on kratom, the lack of consistency across kratom products, and a potential reluctance to speak openly about use to loved ones or medical providers.28,53 Because social media allows sharing of unscientific sources, unsupported claims of medical properties of kratom can be circulated such as its supposed and unproven immune-modulating effects that can lead to potential drug interactions or self-treatment of serious disorders. Although not an overarching theme, some people specified that they kept their use secret. This, along with the fact that kratom was used contemporaneously or concomitantly with other drugs (e.g., buprenorphine, alcohol, benzodiazepines, methamphetamines), suggests that a minority of users are engaging in potentially high-risk practices that are hidden, underscoring the importance of kratom product safety regulation, reducing stigmatization of people with SUD, and making scientifically informed SUD treatment more accessible. It also suggests that clinicians, during the pandemic and beyond, should work with patients to better assess for kratom use, particularly among people with histories of chronic pain, psychiatric symptoms, or SUD who may be fearful about disclosing kratom use.

Limitations

This study had several important limitations. The survey utilized a recruitment method through online advertising for this study that likely introduced selection bias because of the use of electronic distribution techniques that may skew towards a younger and economically/technologically fluent population that has access to such technology thus resulting in underrepresentation of other socio-demographic groups such as low income and those lacking online skills or accessibility to the internet.54 Furthermore, given that the survey was distributed with the help of kratom advocacy groups, respondents were likely overwhelmingly in favor of kratom use.

For social media analyses, posts were limited to only those made during a narrow window of time and in relation to COVID-19, meaning they may not be reflective of kratom use at other times. Posts analyzed corresponded to only three social media websites and are therefore not representative of the broader kratom-using population but also not representative of even all kratom users on social media as data cites from some platforms (e.g., Facebook) could not be obtained. Findings should be interpreted with this in mind. For instance, Reddit may skew younger and more towards males. However, examination of additional data sources from people who did not self-select into our online survey, but posted on Reddit, Twitter, and Bluelight, still provide greater insight about kratom use during a narrow period of time than had they been left wholly unexamined. Further, important demographic information could not be obtained from posts, nor could country of origin for the person posting; though it seems based on the parlance or post context that most were made by US residents. The survey was available during the initial months of the pandemic and the global availability of kratom may not yet have impacted local markets until July 2020. It remains unclear whether kratom actually faced supply chain issues during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Kratom use and availability remained in general unaltered during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic according to the survey, but regular kratom users discussed on social media reducing or rationing their kratom consumption nonetheless. No increased dosing or frequency of use with kratom was reported and few users reported consuming kratom to either prevent or treat a COVID-19 infection both in the survey and the social media analysis. Analysis of social media posts in part agreed and added to the survey data by revealing distinct themes that indicate a risk of kratom dependence, perceived effects of different strains, and concomitant or contemporaneous use of kratom with other drugs. The survey contained similar demographic findings to allow comparison with prior alike studies. Because of the variable kratom products available on the US market, consumers seek to rely on a preferred vendor or product in hopes to receive consistent quality. However, in order to achieve consistent quality and dosing, an appropriate regulatory framework needs to be established and a better understanding of the pharmacology, benefits, and adverse effects of kratom and its ingredients gained. Research on well-defined kratom products to establish dose-effect relationship will benefit quality and labeling of such products to increase consumer confidence and safety.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

Support was provided by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health NIDA

The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

None of the authors report a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jansen KL, Prast CJ. Ethnopharmacology of kratom and the Mitragyna alkaloids. J Ethnopharmacol May-Jun 1988;23(1):115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh D, Narayanan S, Muller CP, et al. Motives for using Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth.) among regular users in Malaysia. J Ethnopharmacol Apr 6 2019;233:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suwanlert S A study of kratom eaters in Thailand. Bull Narc Jul-Sep 1975;27(3):21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veltri C, Grundmann O. Current perspectives on the impact of Kratom use. Substance abuse and rehabilitation 07/01/2019 2019;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Grundmann O Patterns of Kratom use and health impact in the US-Results from an online survey. Drug Alcohol Depend Jul 01 2017;176:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruegel AC, Grundmann O. The medicinal chemistry and neuropharmacology of kratom: A preliminary discussion of a promising medicinal plant and analysis of its potential for abuse. Neuropharmacology Aug 19 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kruegel AC, Uprety R, Grinnell SG, et al. 7-Hydroxymitragynine Is an Active Metabolite of Mitragynine and a Key Mediator of Its Analgesic Effects. ACS central science 06/26/2019 2019;5(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh D, Narayanan S, Vicknasingam B. Traditional and non-traditional uses of Mitragynine (Kratom): A survey of the literature. Brain Res Bull Sep 2016;126(Pt 1):41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todd DA, Kellogg JJ, Wallace ED, et al. Chemical composition and biological effects of kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): In vitro studies with implications for efficacy and drug interactions. Scientific reports 11/05/2020 2020;10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covvey JR, Vogel SM, Peckham AM, Evoy KE. Prevalence and characteristics of self-reported kratom use in a representative US general population sample. Journal of addictive diseases Oct-Dec 2020 2020;38(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palamar JJ. Past-Year Kratom Use in the U.S.: Estimates From a Nationally Representative Sample. American journal of preventive medicine 04/26/2021 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Schimmel J, Amioka E, Rockhill K, et al. Prevalence and description of kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) use in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Addiction (Abingdon, England) 2021 Jan 2021;116(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bath R, Bucholz T, Buros AF, et al. Self-reported Health Diagnoses and Demographic Correlates With Kratom Use: Results From an Online Survey. Journal of addiction medicine 09/17/2019 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Boyer EW, Babu KM, Adkins JE, McCurdy CR, Halpern JH. Self-treatment of opioid withdrawal using kratom (Mitragynia speciosa korth). Addiction Jun 2008;103(6):1048–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coe MA, Pillitteri JL, Sembower MA, Gerlach KK, Henningfield JE. Kratom as a Substitute for Opioids: Results From an Online Survey. Drug and alcohol dependence 09/01/2019 2019;202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Garcia-Romeu A, Cox DJ, Smith KE, Dunn KE, Griffiths RR. Kratom (Mitragyna Speciosa): User Demographics, Use Patterns, and Implications for the Opioid Epidemic. Drug and alcohol dependence 03/01/2020 2020;208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Smith KE, Lawson T. Prevalence and motivations for kratom use in a sample of substance users enrolled in a residential treatment program. Drug Alcohol Depend Nov 1 2017;180:340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obeng S, Wilkerson JL, León F, et al. Pharmacological Comparison of Mitragynine and 7-Hydroxymitragynine: In Vitro Affinity and Efficacy for μ-Opioid Receptor and Opioid-Like Behavioral Effects in Rats. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2021 Mar 2021;376(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basiliere S, Kerrigan S. CYP450-Mediated Metabolism of Mitragynine and Investigation of Metabolites in Human Urine. Journal of analytical toxicology 05/18/2020 2020;44(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behnood-Rod A, Chellian R, Wilson R, et al. Evaluation of the rewarding effects of mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine in an intracranial self-stimulation procedure in male and female rats. Drug and alcohol dependence 10/01/2020 2020;215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Henningfield JE, Grundmann O, Babin JK, Fant RV, Wang DW, Cone EJ. Risk of Death Associated With Kratom Use Compared to Opioids. Preventive medicine 2019 Nov 2019;128. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Henningfield JE, Fant RV, Wang DW. The abuse potential of kratom according the 8 factors of the controlled substances act: implications for regulation and research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) Feb 2018;235(2):573–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vicknasingam B, Chooi WT, Rahim AA, et al. Kratom and Pain Tolerance: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study. The Yale journal of biology and medicine 06/29/2020 2020;93(2). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad K, Aziz Z. Mitragyna speciosa use in the northern states of Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. J Ethnopharmacol May 7 2012;141(1):446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh D, Muller CP, Vicknasingam BK. Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) dependence, withdrawal symptoms and craving in regular users. Drug Alcohol Depend Jun 1 2014;139:132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanciu CN, Gnanasegaram SA, Ahmed S, Penders T. Kratom Withdrawal: A Systematic Review with Case Series. J Psychoactive Drugs Jan-Mar 2019;51(1):12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiss ST, Douglas HE. Treatment of Kratom Withdrawal and Dependence With Buprenorphine/Naloxone: A Case Series and Systematic Literature Review. Journal of addiction medicine 04/01/2021 2021;15(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith KE, Rogers JM, Strickland JC, Epstein DH. When an obscurity becomes a trend: Social-media descriptions of tianeptine use and associated atypical drug use. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Griffin OH, Webb ME. The Scheduling of Kratom and Selective Use of Data. Journal of psychoactive drugs Apr-Jun 2018 2018;50(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma A, McCurdy CR. Assessing the therapeutic potential and toxicity of Mitragyna speciosa in opioid use disorder. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology 2021 Mar 2021;17(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh D, Narayanan S, Vicknasingam B, Corazza O, Santacroce R, Roman-Urrestarazu A. Changing trends in the use of kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) in Southeast Asia. Hum Psychopharmacol May 2017;32(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith KE, Rogers JM, Strickland JC, Epstein DH. When an obscurity becomes trend: social-media descriptions of tianeptine use and associated atypical drug use. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse 04/28/2021 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Swogger MT, Hart E, Erowid F, et al. Experiences of Kratom Users: A Qualitative Analysis. J Psychoactive Drugs Nov-Dec 2015;47(5):360–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith KE, Rogers JM, Schriefer D, Grundmann O. Perceived therapeutic benefits with caveats?: Analyzing social media data to understand complexities of kratom use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Brett EI, Stevens EM, Wagener TL, et al. A content analysis of JUUL discussions on social media: Using Reddit to understand patterns and perceptions of JUUL use. Drug and alcohol dependence 01/01/2019 2019;194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bunting AM, Frank D, Arshonsky J, Bragg MA, Friedman SR, Krawczyk N. Socially-supportive norms and mutual aid of people who use opioids: An analysis of Reddit during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. Drug and alcohol dependence 2021;222:108672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chandrasekharan E, Samory M, Jhaver S, et al. The Internet’s hidden rules: An empirical study of Reddit norm violations at micro, meso, and macro scales. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 2018;2(CSCW):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sowles SJ, McLeary M, Optican A, et al. A content analysis of an online pro-eating disorder community on Reddit. Body image 2018;24:137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vosburg SK, Robbins RS, Antshel KM, Faraone SV, Green JL. Characterizing Pathways of Non-oral Prescription Stimulant Non-medical Use Among Adults Recruited From Reddit. Frontiers in psychiatry 2021;11:1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wojcik S, Messing S, Smith A, Rainie L, Hitlin P. Bots in the Twittersphere. Pew Research Center April 9, 2018. April). Available at: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wpcontent/uploads/sites/14/2018/04/06160833/PI_2018. 2018;4. [Google Scholar]

- 41.MAXQDA 2020 [computer software]. In: software V, ed. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software, Germany; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brennan RL, Prediger DJ. Coefficient kappa: Some uses, misuses, and alternatives. Educational and psychological measurement 1981;41(3):687–699. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia medica 2012 2012;22(3). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen J A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and psychological measurement 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Eye A, Von Eye M. Can one use Cohen’s kappa to examine disagreement? Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences 2005;1(4):129. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trakulsrichai S, Sathirakul K, Auparakkitanon S, et al. Pharmacokinetics of mitragynine in man. Drug Des Devel Ther 2015;9:2421–2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prozialeck WC. Update on the Pharmacology and Legal Status of Kratom. J Am Osteopath Assoc Dec 1 2016;116(12):802–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chittrakarn S, Penjamras P, Keawpradub N. Quantitative analysis of mitragynine, codeine, caffeine, chlorpheniramine and phenylephrine in a kratom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth.) cocktail using high-performance liquid chromatography. Forensic science international 04/10/2012 2012;217(1–3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fowble KL, Musah RA. A validated method for the quantification of mitragynine in sixteen commercially available Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) products. Forensic science international 2019 Jun 2019;299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scott TM, Yeakel JK, Logan BK. Identification of mitragynine and O-desmethyltramadol in Kratom and legal high products sold online. Drug Test Anal Sep 2014;6(9):959–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh D, Yeou Chear NJ, Narayanan S, et al. Patterns and reasons for kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) use among current and former opioid poly-drug users. Journal of ethnopharmacology 03/01/2020 2020;249. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Wilson LL, Chakraborty S, Eans SO, et al. Kratom Alkaloids, Natural and Semi-Synthetic, Show Less Physical Dependence and Ameliorate Opioid Withdrawal. Cellular and molecular neurobiology 01/12/2021 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Smith KE, Rogers JM, Shriefer D, Grundmann O. Therapeutic benefit with caveats?: Analyzing social media data to understand the complexities of kratom use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. under review [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Brown J, West R, Beard E, Michie S, Shahab L, McNeill A. Prevalence and characteristics of e-cigarette users in Great Britain: Findings from a general population survey of smokers. Addict Behav Jun 2014;39(6):1120–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.