Abstract

Recent national and state legislation has called attention to stark racial/ethnic disparities in maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity (SMM), the latter of which is defined as having a life-threatening condition or life-saving procedure during childbirth. Using linked New York City birth and hospitalization data for 2012–14, we examined whether racial and economic spatial polarization is associated with SMM rates, and whether the delivery hospital partially explains the association. Women in ZIP codes with the highest concentration of poor blacks relative to wealthy whites experienced 4.0 cases of SMM per 100 deliveries, compared with 1.7 cases per 100 deliveries among women in the neighborhoods with the lowest concentration (risk difference = 2.4 cases per 100). Thirty-five percent of this difference was attributable to the delivery hospital. Women in highly polarized neighborhoods were most likely to deliver in hospitals located in similarly polarized neighborhoods. Housing policy that targets racial and economic spatial polarization may address a root cause of SMM, while hospital quality improvement may mitigate the impact of such polarization.

In the US, black women are three times more likely to experience a pregnancy-related death than are white women.1 In New York City, Asian and Latina women there are at increased risk.2 Black and Latina women there are three and two times, respectively, more likely than white women to experience severe maternal morbidity (SMM) during childbirth.3,4 SMM, defined as having a life-threatening condition or life-saving procedure during child birth, is nearly a hundred times as frequent as mortality.5 Given the relatively small number of pregnancy-related deaths, SMM is an important marker of near misses that can be used to study maternal mortality, as well as being an important health outcome. Alarmingly, both SMM and mortality are increasing in the US,6,7 and racial/ethnic disparities in SMM are persistent. Individual-level risk factors such as obesity and hypertension do not entirely explain these trends,8 and the quality of obstetric care is likely a factor.9 Legislation has been enacted at the federal10 and state11 levels in response to rising maternal death rates, which creates the opportunity to develop strategies for reducing the risk of maternal mortality and decrease disparities. The etiology of disparities in SMM is complex, and multilevel interventions are likely needed. However, current research focuses primarily on individual-level risk factors, and evidence on the underlying macro-level determinants that influence SMM is lacking.

One important determinant of SMM may be the geography of racial and economic privilege and disadvantage, which is patterned by structural racism. Structural racism is the manifestation of historical and current oppression that shapes neighborhoods and institutions, which results in differential access to opportunities and resources.12 Public health policy makers acknowledge that historical discriminatory housing practices (called redlining) in New York City have had a lasting effect on neighborhood racial segregation and institutions serving segregated neighborhoods.13 At the same time, growing economic inequality globally has brought increasing attention to social inequality and polarization, and a concern exists that this growing polarization is reflected in urban neighborhoods.14,15 Racial and economic spatial polarization, defined as extreme concentrations of residents from certain racial/ethnic or economic groups in a given neighborhood, may have a profound impact on health, including SMM. A growing body of literature suggests that racial and economic spatial polarization are associated with adverse health outcomes, including birth outcomes.16,17 This literature builds on decades of evidence regarding the ill effects of racial segregation on infant outcomes, particularly among infants of black women.18 However, racial segregation—including racial spatial polarization—has not been studied in association with SMM, despite intense current focus on SMM as an urgent public health issue.

Pathways that link racial and economic spatial polarization to SMM may be similar to those proposed in the literature on segregation and birth outcomes.19,20 The psychosocial and built environment may result in chronic stress and health behaviors, which in turn put women at risk for comorbidities such as obesity and hypertension—important risk factors for SMM.21 A less-studied yet potentially modifiable pathway is access to high-quality health care, including care at the delivery hospital. At least half of maternalmortality22 andathirdofSMMevents23 are likely preventable during childbirth, which points to poor quality of care as a risk factor for maternal mortality and SMM.24 In New York City, black and Latina women are more likely to deliver in hospitals with higher risk-adjusted rates of SMM, which suggests that the delivery hospital may play a role in SMM inequities.3,4 Variation in the racial/ethnic distribution of deliveries in the city’s hospitals calls into question whether underlying racial and economic spatial polarization is driving where women deliver and, in turn, influencing their risk of SMM.

The Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) is a measure of racial and economic spatial polarization, a type of segregation, that is increasingly used to monitor population health inequalities.25 The Racial Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE Race) contrasts the concentration of blacks and whites in a given neighborhood and therefore identifies extremes of both concentration levels simultaneously.26 Parallel indices measure economic spatial polarization (ICE Income) and joint racial and economic spatial polarization (ICE Race-Income), also referred to as economic segregation or racial economic segregation. The indices are conceptually relevant for small geographic areas,27 so are appropriate for studying the polarization of neighborhoods within New York City.

Our objective was to examine racial and economic spatial polarization in association with SMM in New York City using linked birth certificate and hospitalization data for 2012–14. We chose to examine three measures of spatial polarization—the ICE measures for race, income, and race and income combined—to reflect different dimensions of social patterning in the city that may have distinct policy implications. We hypothesized that neighborhoods with the highest concentration of blacks relative to whites, low-income households relative to high-income households, and low-income black households relative to high-income white households have the highest risk of SMM. We further hypothesized that the hospital of delivery would partially mediate the associations between spatially patterned risks and SMM. A secondary objective was to examine whether women from the most racially and economically polarized neighborhoods delivered in hospitals located in similarly polarized neighborhoods.

Study Data And Methods

DATA SOURCES

We used vital statistics birth records linked with New York State discharge abstract data from the Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System for all delivery hospitalizations in New York City in 2012–14. The linkage was conducted by the New York State Department of Health. Delivery hospitalizations were identified based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), diagnosis and procedure codes and diagnosis-related group delivery codes.28 We linked the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) data for 2012–16 to birth and hospitalization data by ZIP code, excluding women with a missing ZIP code (n = 1,091) or residence outside of New York City (n = 27,071).

Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, the New York State Department of Health, and the Office for the Program for the Protection of Human Subjects at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

MEASURES

We calculated Index of Concentration at the Extremes measures at the ZIP code level using ACS data for 183 of the ZIP codes in New York City. ICE Race was calculated as [(N of non-Hispanic white persons) – (N of non-Hispanic black persons)/total non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white population]. The resulting measure ranges from −1 (all non-Hispanic black) to 1 (all non-Hispanic white). ICE Income was computed analogously using ACS population counts of the number of households in the bottom and top quintiles of annual US household income: households earning less than $25,000 (low income) and those earning $100,000 or more (high income). The index for race and income was computed using ACS population counts of black-headed households earning less than $25,000 (black, low income) and white-headed households earning $100,000 or more (white, high income).We describe univariate statistics of ICE measures in online appendix exhibit A1.29

We used an algorithm published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to identify SMM; it is composed of diagnoses for life-threatening conditions (for example, eclampsia and renal failure) and procedure codes for life-saving procedures (such as hysterectomy).30

Covariates selected for risk adjustment were maternal sociodemographic factors, comorbidities, and obstetric factors that could predispose women to greater risk of SMM. Race, Latino origin, maternal education, age, previous live births, and nativity (US-born/foreign-born status) are self-reported items on the birth certificate. We created categories of combined race and ethnicity: non-Latina black (henceforth referred to as “black”), Latina, non-Latina white (henceforth referred to as “white”), Asian (including Pacific Islander), and other. If a woman chose Latino origin, she was classified as Latina regardless of race. If a woman chose black in combination with white or Asian race, she was classified as black. We additionally created the categories Latina black, Latina white, and Latina other for a secondary analysis. Medicaid status (Medicaid versus private/self-pay/other) was determined by reimbursement codes. Comorbidities were obtained from the birth certificate (prepregnancy body mass index and multiple pregnancy), hospital discharge record (asthma, cardiac disease, renal disease, pulmonary disease, musculoskeletal disease, blood disorders, mental disorders, central nervous system disorders, rheumatic heart disease, placentation disorders, anemia, and prior cesarean delivery), or the birth certificate and hospital discharge record combined (prepregnancy diabetes, prepregnancy hypertension, gestational diabetes, and gestational hypertension).31

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We conducted a complete case analysis because of the low frequency of missing values (<1.6 percent). The final analytic sample consisted of 316,600 women who delivered in forty hospitals.

We examined the distributions of ICE measures across ZIP codes in New York City and divided them into quintiles.14,23,25 We estimated logit models and generated predicted probabilities to calculate unadjusted and adjusted risk differences for quintile of racial and economic segregation and SMM, accounting for the clustering of observations into ZIP codes using a robust cluster estimator for standard error. We chose to estimate risk differences instead of risk ratios to report the number of excess cases of SMM, as the former provides a measure of the burden of disease with more direct clinical and public health implications. We considered sociodemographic factors, including race/ethnicity, as potential confounders (although some of these factors, such as education, may actually be mediators between segregation and SMM). Comorbidities and the hospital of delivery were considered potential mediators on the causal pathway between segregation and SMM (see the conceptual model in appendix exhibit A2).29 To estimate any direct effect of ICE measures on SMM after all measured variables were accounted for, we included both confounders and mediators in the adjusted risk-difference models.

Using Fairlie nonlinear decomposition32 with random variable ordering,33 we tested the hypothesis that associations between ICE measures and SMM were mediated in part by the delivery hospital. This technique is used to explain the amount that selected covariates contribute to individual or group differences by race, sex, or geography.33 In this case, we were primarily interested in the contribution of the delivery hospital to the gap in SMM between ICE quintiles, with sociodemographic and comorbidity pathways adjusted for. In this approach, predicted probabilities are generated for each neighborhood category from a logit model. The contribution of each variable to the disparity is equal to the change in the average predicted probability from replacing the distribution of a given covariate in neighborhoods in quintile 1 with the distribution of the covariates in all other neighborhoods, while holding the distributions of the other variables constant. We collapsed quintiles 2–5 into a single group because of violations of positivity: There were few or no cases of SMM from women in neighborhoods in those quintiles at some hospitals.

To test the hypothesis that the effect of ICE measures would be strongest among black women, we created an interaction term in each logit model for ICE measure by race/ethnicity and calculated risk differences stratified by race/ethnicity. Among Latina women, we tested an interaction term for ICE measures and race (black, white, or other).

A secondary analysis examined whether the ICE measures for the neighborhood (ZIP code) of the hospital were associated with the measures for the mother’s neighborhood.

Because blood transfusions account for a significant proportion of SMM events, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which isolated blood transfusions were removed from the index. We performed statistical analyses with Stata, version 14.1.

LIMITATIONS AND ADVANTAGES

Our analysis had limitations, including the possibility of unmeasured variables, using administrative data to measure SMM, and its cross-sectional design. The coding intensity of hospitals may influence the measure of SMM, and in that case, if the intensity were correlated with ICE measures or mother’s race, our estimates could have been biased in an unpredictable direction. Future research should be designed to test the potential impact of coding bias in studies that compare rates of SMM across hospitals. Finally, although NewYork City is an ideal setting in which to study our research question (given its intense racial and economic spatial polarization), it is unique, and our results might not be generalizable to all regions in the US—in particular, rural areas. Future research might examine our research question in other geographic regions.

Despite these limitations, our study had several advantages. We studied a sizable number of births to women of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds and were able to risk-adjust for a broad array of covariates. We employed a rigorous methodological approach to define neighborhood characteristics that are currently a topic of housing policy debate. Additionally, we focused on a mediating factor—the hospital of delivery—that is currently the focus of obstetric quality initiatives to reduce SMM.

Study Results

Sociodemographic characteristics by Index of Concentration at the Extremes measures are displayed in exhibit 1 and appendix exhibit A3.29

Exhibit 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of 316,600 women delivering in New York City in 2012–14, by racial and economic spatial polarization measures

| ICE Race | ICE Income | ICE Race-Income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Characteristics | No. | Quintile 1 (n = 69,437) | Quintile 5 (n = 37,824) | Quintile 1 (n = 107,038) | Quintile 5 (n = 34,088) | Quintile 1 (n = 84,597) | Quintile 5 (n = 36,341) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Black | 66,281 | 58% | 3% | 28% | 5% | 50% | 3% |

| Latina | 98,569 | 29 | 11 | 44 | 9 | 41 | 9 |

| Non-Latina white | 95,708 | 8 | 71 | 14 | 69 | 6 | 71 |

| Asian | 56,042 | 5 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 4 | 16 |

| Age, years | |||||||

| Less than 20 | 14,221 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| 20 to less than 35 | 231,732 | 74 | 63 | 77 | 59 | 75 | 60 |

| 35 to less than 40 | 54,713 | 14 | 27 | 13 | 30 | 13 | 30 |

| 40 or more | 15,934 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 9 |

| Born in US | |||||||

| No | 154,629 | 47 | 33 | 51 | 26 | 48 | 27 |

| Yes | 161,971 | 53 | 67 | 49 | 74 | 52 | 73 |

| Education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 68,220 | 23 | 5 | 32 | 3 | 28 | 3 |

| High school | 71,457 | 26 | 7 | 29 | 4 | 27 | 5 |

| Some college | 71,523 | 31 | 13 | 25 | 9 | 30 | 10 |

| College or more | 105,400 | 20 | 75 | 15 | 84 | 16 | 82 |

| Insurance during pregnancy | |||||||

| Medicaid | 199,977 | 75 | 19 | 83 | 10 | 80 | 11 |

| Private or other | 116,623 | 25 | 81 | 17 | 90 | 20 | 89 |

| Previous live births | |||||||

| No | 142,056 | 42 | 58 | 40 | 62 | 41 | 61 |

| Yes | 174,544 | 58 | 42 | 60 | 38 | 59 | 39 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of New York City birth certificate and hospital discharge data linked to American Community Survey data.

NOTES The Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) measure for race (ICE Race) is the relative concentration of non-Hispanic black to non-Hispanic white populations in the mother’s or hospital’s ZIP code. The ICE measure for income (ICE Income) is the relative concentration of low-income households to high-income households in a ZIP code. The ICE measure for race and income (ICE Race-Income) is the relative concentration of low-income black households to high-income white households in a ZIP code. For all three indices, quintile 1 is the highest relative concentration and quintile 5 is the lowest. Chi-square bivariate tests of frequencies of all characteristics by each ICE measure were significant (p < 0.001).

The risk of SMM for the overall population was 2.6 percent (8,239 cases) (data not shown). The unadjusted risk of SMM showed a decreasing trend as relative concentration of blacks, low-income households, or black low-income households decreased (exhibit 2). In the neighborhoods with the highest relative concentration of blacks relative to whites (ICE Race), the risk was 4.1 percent. This decreased across quintiles, with only 1.7 percent of women in quintile 5 experiencing an SMM event (unadjusted risk difference: 2.4). The risk ranged from 3.1 percent in quintile 1 to 1.7 percent in quintile 5 on the ICE Income measure (unadjusted RD: 1.4), and from 4.0 percent to 1.7 percent on the ICE Race-Income measure (unadjusted RD: 2.3). Differences were attenuated after we adjusted for all measured confounders and mediators.

Exhibit 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted risk difference (RD) for severe maternal morbidity (SMM) in New York City in 2012–14, by racial and economic spatial polarization measures

| Unadjusted RD | Adjusted RDa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| ICE measure | Cases per 100 | Cases per 100 | 95% CI | Cases per 100 | 95% CI |

| ICE Race | |||||

| Quintile 1 | 4.1 | 2.4 | 2.0, 2.8 | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.6 |

| Quintile 2 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 0.7, 1.3 | 0.1 | −0.1, 0.3 |

| Quintile 3 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 0.0, 0.7 | 0.2 | −0.1, 0.4 |

| Quintile 4 | 1.7 | 0.0 | −0.3, 0.3 | 0.0 | −0.2, 0.4 |

| Quintile 5 | 1.7 | 0.0 | Ref | 0.0 | Ref |

| ICE Income | |||||

| Quintile 1 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.8, 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 |

| Quintile 2 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 0.6, 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 |

| Quintile 3 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.3, 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.5 |

| Quintile 4 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 0.2, 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.5 |

| Quintile 5 | 1.7 | 0.0 | Ref | 0.0 | Ref |

| ICE Race−Income | |||||

| Quintile 1 | 4.0 | 2.3 | 1.9, 2.7 | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 |

| Quintile 2 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 0.5, 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.0, 0.4 |

| Quintile 3 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 0.0, 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.0, 0.5 |

| Quintile 4 | 1.8 | 0.2 | −0.1, 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0, 0.4 |

| Quintile 5 | 1.7 | 0.0 | Ref | 0.0 | Ref |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of New York City birth certificate and hospital discharge data linked to American Community Survey data.

NOTES N = 316,600. The Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) measures for race, income, and race and income are explained in the notes to exhibit 1. Quintile 1 represents the highest relative concentration of non-Hispanic black, low-income, or non-Hispanic black and low-income households, and quintile 5 the lowest. CI is confidence interval.

Adjusted for race/ethnicity, age, nativity, previous live births, education, insurance status, prepregnancy body mass index, multiple pregnancy, prepregnancy diabetes, prepregnancy hypertension, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, cardiac disease, renal disease, pulmonary disease, musculoskeletal disease, blood disorders, mental disorders, central nervous system disorders, rheumatic heart disease, placentation disorders, anemia, asthma, prior cesarean delivery, and hospital of delivery.

We conducted a decomposition analysis that estimated the contribution of the hospital of delivery to differences in SMM across neighborhoods. For ICE Race, 36.3 percent of the difference in SMM compared to other neighborhoods wasduetothehospitalofdelivery,with50.1percent due to comorbidities and 3.6 percent to sociodemographic factors (exhibit 3). Contributions to the disparity by the hospital of delivery were similar for ICE Race-Income (34.8 percent) but smaller for ICE Income (14.2 percent).

Exhibit 3.

Factors contributing to associations between racial and economic spatial polarization and severe maternal morbidity in New York City in 2012–14

| ICE Race | ICE Income | ICE Race-Income | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Factors | Cases per 100 | % of difference due to factor | Cases per 100 | % of difference due to factor | Cases per 100 | % of difference due to factor |

| Sociodemographic factorsa | 0.07 | 3.6% | 0.11 | 16.2%*** | 0.14 | 7.3%** |

| Comorbiditiesb | 0.98 | 50.1**** | 0.44 | 62.6**** | 0.94 | 49.2**** |

| Delivery hospital | 0.71 | 36.3**** | 0.10 | 14.2 | 0.67 | 34.8**** |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of New York City birth certificate and hospital discharge data linked to American Community Survey data.

NOTES N = 316,600. The Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) measures for race, income, and race and income are explained in the notes to exhibit 1. “Percent of difference” refers to the amount of risk difference between racially and economically polarized neighborhoods that is due to the factor.

Age, nativity, previous live births, education, and insurance status.

Prepregnancy body mass index, multiple pregnancy, prepregnancy diabetes, prepregnancy hypertension, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, cardiac disease, renal disease, pulmonary disease, musculoskeletal disease, blood disorders, mental disorders, central nervous system disorders, rheumatic heart disease, placentation disorders, anemia, asthma, and prior cesarean delivery.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

We examined whether race/ethnicity moderated associations between neighborhood measures and SMM. We present unadjusted risk differences stratified by race/ethnicity in appendix exhibit A4.29 Risk differences were of the largest magnitude for black and Latina women. When we analyzed the impact of ICE measures among different groups of Latinas, we found the most notable differences among black Latina women (appendix exhibit A5).29

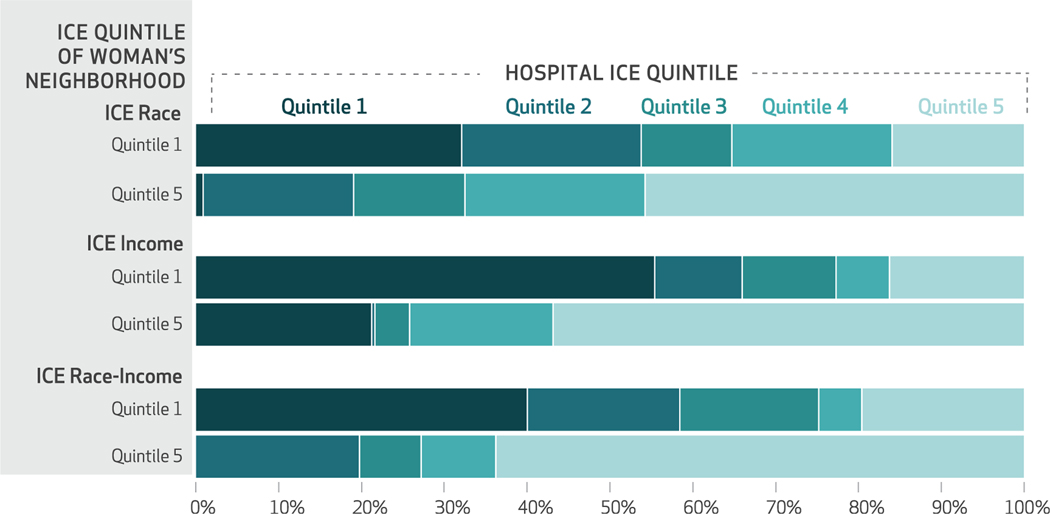

Thirty-two percent of women who lived in neighborhoods with the highest relative concentration of blacks delivered in hospitals located in similarly “black polarized” neighborhoods, whereas only 1 percent of women from neighborhoods with a high relative concentration of whites delivered in “black polarized” neighborhoods (exhibit 4). Fifty-five percent of women from the neighborhoods with the highest concentration of low-income households delivered in hospitals located in neighborhoods with the highest concentration of low-income households, while only 21 percent of women from neighborhoods with the highest concentration of high-income households delivered in hospitals located in neighborhoods with the highest concentration of low-income households. Distributions using the ICE Race-Income measure followed similar patterns. Appendix exhibit A6 shows the distribution of deliveries across quintiles of ICE measures for mother’s residence and hospital location.29 The correlation was mostly due to the first and fifth quintiles, and no dose-response relationship was observed. Chi-square tests for frequencies were significant (p < 0.001) for all ICE measures.

Exhibit 4.

Percent of women who delivered in hospitals in racially and economically polarized neighborhoods in New York City in 2012–14, by polarization of the woman’s neighborhood

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of New York City birth certificate and hospital discharge data linked to American Community Survey data.

NOTES NOTES The Index of Concentration at the Extremes (ICE) measures for race, income, and race and income are explained in the notes to exhibit 1. Quintile 1 represents the highest relative concentration of non-Hispanic black, low-income, or non-Hispanic black and low-income households, and quintile 5 the lowest.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded blood transfusions from the algorithm used to define SMM found reduced SMM risk as neighborhood relative concentrations of blacks, low-income households, and black low-income households decreased. Fully adjusted risk differences were attenuated (appendix exhibit A7).29

Discussion

Our examination of racial and economic social polarization in association with severe maternal morbidity in New York City found stark differences in risk of SMM across neighborhoods. These differences were due in part to the hospital of delivery. Neighborhoods with extreme racial polarization experienced the greatest excess risk of SMM. Furthermore, the associations between racial and economic spatial polarization and SMM were of the largest magnitude among black and Latina women.

Our findings contribute to the small body of literature on the social determinants of SMM. Renata Howland and coauthors reported that high neighborhood poverty in New York City was associated with high rates of SMM.34 Several other studies have used neighbourhood characteristics as control variables for hospital characteristics under investigation.35–37 Instead, we measured racial and economic polarization, which takes into account concentrations of both race and income and is thus a stronger predictor of health outcomes than income threshold measures alone.16 Previous investigations of associations between Index of Concentration at the Extremes measures and infant outcomes had similar results.16,38 Our study built on existing literature by testing mediators for differential maternal health outcomes in neighborhoods polarized by race, income, or both. Our analysis is also novel because it considered neighborhood of residence as a social determinant that drove women to deliver in lower-quality hospitals, as opposed to a covariate for risk adjustment.

Our results suggest that the hospital of delivery contributes approximately one-third of the difference in SMM between racially and economically polarized neighborhoods. We focused this analysis on the contribution of the hospital of delivery to the inequitable spatial pattern of SMM in New York City to demonstrate that improving hospital quality may be one downstream factor—in addition to individual health status—that could be modified to mitigate the impact of racial and economic spatial polarization. Because our models risk-adjusted for a wide array of maternal risk factors, any leftover risk attributed to hospital can be interpreted as a proxy for quality. Quality improvement has been suggested as important to reducing racial/ethnic disparities in SMM.39 Our finding that delivery site is one mechanism by which racial and economic spatial polarization influences the risk of SMM adds to the urgency of increasing equitable access to high-quality obstetric care.

Comorbidities and sociodemographic characteristics together accounted for over half of the risk difference between black, low-income neighborhoods and all other neighborhoods. A larger proportion of risk was accounted for by comorbidities, as they are pathways by which neighborhood-level psychosocial and material exposures are “embodied” to influence risk of SMM.40 Future research might focus on the causative and protective details of these pathways.

Research on segregation and birth outcomes generally points to greater magnitudes of effects among blacks.18 We found the largest excess risks among blacks and Latinas—especially black Latinas. One potential explanation for the lack of association between neighborhood racial and economic polarization and SMM among white women is their greater ability to access resources outside of their neighborhoods—for example, a higher-quality hospital. The small number of SMM events within strata meant that we could not conduct a decomposition analysis within strata of race/ethnicity to test this hypothesis. However, previous research has demonstrated that white women were more likely to travel outside their neighborhoods for delivery.41 Notably, our definition of racial polarization was the relative concentration of blacks and whites. This definition is an appropriate proxy for the historical structuring of neighborhoods due to institutional racism. The fact that Latinas in these neighborhoods also experience high risk of SMM is evidence that there is a structural impact of the neighborhood itself, beyond the race of the mother. The concentration of Latino immigrants—the extent to which the neighborhood is an ethnic enclave—may have implications for the ability of Latinas (particularly immigrant women) to obtain high-quality obstetric care.

Our exploratory finding that women in racially and economically polarized neighborhoods were likely to deliver in hospitals located in similarly polarized neighborhoods stimulates hypotheses about how the neighbourhood in which a hospital is located may underlie the inequity in where women receive obstetric care. On the one hand, the neighborhood in which a woman lives may constrain her choice of where to deliver a baby. Black and Latina women who live in the most racially and economically polarized neighborhoods may face constraints to accessing high-quality care, such as lack of timely prenatal care and poor transportation. On the other hand, hospitals located in New York City neighborhoods with a high concentration of black residents or low-income households may face unique structural barriers to the delivery of high-quality care, such as a limited ability to recruit highly trained clinicians and administrators that in turn prevents the hospitals from attracting pregnant women from high-income and white neighborhoods. Future research might address our research question in a larger sample of hospitals and in different urban or rural contexts.

Policy Implications

Our findings have implications for current policy discussions on how to best address the deplorable inequity in maternal mortality and morbidity in the US. In response to the crisis of rising maternal death rates, the US enacted a law that established state grants for activities, including both the improved reporting of maternal death and provider education to improve the quality of maternal care.10 In 2019 New York State enacted a law to establish maternal mortality review boards and a maternal mortality and morbidity advisory council, whose role is to develop strategies for reducing the risk of maternal mortality and decrease disparities.11 Our results suggest that neighborhood polarization plays a role in the disparate care received by black and Latina women and must be considered in any strategy to reduce SMM disparities. Improving women’s health in neighborhoods with a high relative concentration of black residents or low-income households could reduce comorbidities, in particular for women of color. At the same time, part of the excess burden of SMM in those neighborhoods is due to the hospital of delivery, which indicates that women in these neighborhoods could benefit by obtaining the same quality of obstetric care as do women in neighborhoods with a high relative concentration of white residents or high-income households. Women in polarized neighborhoods overwhelmingly delivered in hospitals located in similarly polarized neighborhoods, which is an institutional manifestation of the underlying social polarization of New York City. Potential solutions include directly investing in health promotion in high-risk neighborhoods, which is the focus of a current initiative of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.42 A second approach is to improve the quality of obstetric care in the hospitals where women in highly polarized neighborhoods deliver, for which increasing resources to these hospitals is likely vital.43 To monitor the success of intervening in highly polarized neighborhoods and the hospitals that serve them, trends in SMM rates could be monitored using neighborhood Index of Concentration at the Extremes measures, to ensure that quality improvement is reaching women in the neighborhoods with the highest burden of SMM.

Other timely policy topics for which our results have implications are the increasing income polarization and the lasting impact of slavery and racial inequity in the US. The implications of these two sociological forces go hand in hand in New York City neighborhoods. Both racial and economic spatial polarization were associated with SMM, but racial spatial polarization most clearly outlined the excess burden of SMM. During the Obama administration, the Department of Housing and Urban Development put in place a legal requirement for states to take meaningful action on historical patterns of segregation. This requirement was suspended in 2018,44 and the department has proposed a rule that some people claim would make it more difficult to demonstrate that a policy has had a discriminatoryeffect.45 The New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development has proceeded regardless, and in 2018 it launched “Where We Live,” a study of the causes and impacts of housing segregation in the city.46 Such efforts are crucial to addressing the fundamental causes of the US maternal mortality and morbidity crisis.

Conclusion

The combination of racial and economic spatial polarization is associated with severe maternal morbidity in New York City. The hospital of delivery partially explained this association. Policies addressing racial and economic segregation, health promotion in highly polarized neighborhoods, and quality improvement in hospitals that serve these neighborhoods are needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was the subject of an oral presentation at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Washington, D.C., June 3, 2019. This work was funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R01 MD007651) and the Blavatnik Family Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors acknowledge Andrew Rundle and James Quinn with the Built Environment and Health Research Group at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health for their assistance with geographic data.

Contributor Information

Teresa Janevic, Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute, Departments of Population Health Science and Policy and Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in New York City..

Jennifer Zeitlin, Center for Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Inserm UMR 1153, Obstetrical, Perinatal, and Pediatric Epidemiology Research Team (Epopé), Paris Descartes University, in France..

Natalia Egorova, Department of Population Health Science and Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai..

Paul L. Hebert, Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development Center for Veteran-Centered, Value-Driven Health, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, and a research associate professor in the Department of Health Services, School of Public Health, University of Washington, both in Seattle..

Amy Balbierz, Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute, Department of Population Health Science and Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai..

Elizabeth A. Howell, Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute, Departments of Population Health Science and Policy and Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai..

NOTES

- 1.Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths—United States, 2007–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(35):762–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Pregnancy-associated mortality: New York City, 2006–2010 [Internet]. New York (NY): The Department; [cited 2020 Mar 5]. Available from: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/ms/pregnancy-associated-mortality-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(2):143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Howell EA, Egorova NN, Janevic T, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Severe maternal morbidity among Hispanic women in New York City: investigation of health disparities. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(2):285–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a multistate analysis, 2008–2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210(5):435.e1-.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liese KL, Mogos M, Abboud S, Decocker K, Koch AR, Geller SE. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6(4):790–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the U.S. maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonard SA, Main EK, Carmichael SL. The contribution of maternal characteristics and cesarean delivery to an increasing trend of severe maternal morbidity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, Wapner RJ, Reddy UM, Varner MW, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1460–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Preventing Maternal Deaths Act of 2018, Pub. L. 155–344, Sec. 132 Stat.5047 (Dec. 21, 2018).

- 11.An act to amend the public health law, in relation to maternal mortality review boards and the maternal mortality and morbidity advisory council, S.1819/A.3276 Assembly of State of New York, 2019. Regular Session. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Take Care New York 2020: 3rd annual update 2018 [Internet]. New York (NY): The Department; 2018. [cited 2020 Mar 5]. Available from: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/tcny/tcny-2020-annual-report3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modai-Snir T, van Ham M. Neighbourhood change and spatial polarization: the roles of increasing inequality and divergent urban development. Cities. 2018;82:108–18. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massey DS. The age of extremes: concentrated affluence and poverty in the twenty-first century. Demography. 1996;33(4):395–412, discussion 413–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huynh M, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G, Waterman PD, et al. Spatial social polarization and birth outcomes: preterm birth and infant mortality—New York City, 2010–14. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(1):157–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallace M, Crear-Perry J, Theall KP. Privilege and deprivation: associations between the index of concentration at the extremes and birth equity in Detroit. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(8):537. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehra R, Boyd LM, Ickovics JR. Racial residential segregation and adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;191:237–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anthopolos R, Kaufman JS, Messer LC, Miranda ML. Racial residential segregation and preterm birth: built environment as a mediator. Epidemiology. 2014;25(3):397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer MR, Cooper HL, Drews-Botsch CD, Waller LA, Hogue CR. Metropolitan isolation segregation and black-white disparities in very preterm birth: a test of mediating pathways and variance explained. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(12):2108–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gray KE, Wallace ER, Nelson KR, Reed SD, Schiff MA. Population-based study of risk factors for severe maternal morbidity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012;26(6):506–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuckerwise LC, Lipkind HS. Maternal early warning systems—towards reducing preventable maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity through improved clinical surveillance and responsiveness. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(3):161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawton BA, Jane MacDonald E, Stanley J, Daniells K, Geller SE. Preventability review of severe maternal morbidity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(4):515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Alton ME, Friedman AM, Bernstein PS, Brown HL, Callaghan WM, Clark SL, et al. Putting the “M” back in maternal-fetal medicine: a 5-year report card on a collaborative effort to address maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(4):311–317.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N,Waterman PD, Spasojevic J, Li W, Maduro G, Van Wye G. Public health monitoring of privilege and deprivation with the Index of Concentration at the Extremes. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(2):256–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massey DS, Denton NA. The dimensions of residential segregation. Soc Forces. 1988;67(2):281–315. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieger N, Kim R, Feldman J, Waterman PD. Using the Index of Concentration at the Extremes at multiple geographical levels to monitor health inequities in an era of growing spatial social polarization: Massachusetts, USA (2010–14). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):788–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuklina EV, Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, Meikle SF, Posner SF, et al. An enhanced method for identifying obstetric deliveries: implications for estimating maternal morbidity. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(4):469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 30.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1029–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lydon-Rochelle MT, Holt VL, Cárdenas V, Nelson JC, Easterling TR, Gardella C, et al. The reporting of pre-existing maternal medical conditions and complications of pregnancy on birth certificates and in hospital discharge data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fairlie RW. An extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique to logit and probit models. J Econ Soc Meas. 2005;30(4):305–16. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fairlie RW. Addressing path dependence and incorporating sample weights in the nonlinear Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique for logit, probit, and other nonlinear models [Internet]. Stanford (CA): Stanford Institute for EconomicPolicy Research; 2017. Apr [cited 2020 Mar 5]. (Discussion Paper No. 17–013). Available from: https://siepr.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/17-013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howland RE, Angley M, Won SH, Wilcox W, Searing H, Liu SY, et al. Determinants of severe maternal morbidity and its racial/ethnic disparities in New York City, 2008–2012. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23(3):346–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Huang Y, D’Alton ME, Wright JD. Hospital delivery volume, severe obstetrical morbidity, and failure to rescue. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(6): 795.e1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reid LD, Creanga AA. Severe maternal morbidity and related hospital quality measures in Maryland. J Perinatol. 2018;38(8):997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guglielminotti J, Landau R, Wong CA, Li G. Patient-, hospital-, and neighborhood-level factors associated with severe maternal morbidity during childbirth: a cross-sectional study in New York State 2013–2014. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23(1):82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chambers BD, Baer RJ, McLemore MR, Jelliffe-Pawlowski LL. Using index of concentration at the extremes as indicators of structural racism to evaluate the association with preterm birth and infant mortality—California, 2011–2012. J Urban Health. 2019;96(2):159–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howell EA, Zeitlin J. Improving hospital quality to reduce disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2017; 41(5):266–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krieger N. Epidemiology and the people’s health: theory and context. New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hebert PL, Chassin MR, Howell EA. The contribution of geography to black/white differences in the use of low neonatal mortality hospitals in New York City. Med Care. 2011; 49(2):200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gale R. For a big-city health department, a new focus on health equity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(3):347–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandra A, Frakes M, Malani A. Challenges to reducing discrimination and health inequity through existing civil rights laws. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(6):1041–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Department of Housing and Urban Development. Affirmatively furthering fair housing: withdrawal of notice extending the deadline for submission of assessment of fair housing for consolidated plan participants. Fed Regist. 2018;83(100):23928. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fadulu L. Trump proposal would raise bar for proving housing discrimination. New York Times [serial on the Internet]. 2019. Aug 2 [cited 2020 Mar 5]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/02/us/politics/trump-housing-discrimination.html

- 46.New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Where We Live NYC: draft plan [Internet]. New York (NY): City of New York; [2020. Mar 5]. Available from: https://wherewelive.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Where-We-Live-NYC-Draft-Plan.pdf [Google Scholar]