Abstract

Background

Baka hunter-gatherers have a well-developed traditional knowledge of using plants for a variety of purposes including hunting and fishing. However, comprehensive documentation on the use of plants for hunting and fishing in eastern Cameroon is still lacking.

Method

This study aimed at recording plants used for hunting and fishing practices, using focus group discussion, interviews and field surveys with 165 Baka members (90 men and 75 women) of different age groups in 6 villages.

Results

The most frequent techniques used for hunting and fishing are the use of animal traps, fishing lines, dam fishing, hunting with dogs and spear hunting. We recorded a total of 176 plant species used in various hunting practices, the most frequently cited one being Zanthoxylum gilletii (De Wild.) P.G.Waterman, Greenwayodendron suaveolens (Engl. & Diels) Verdc., Microcos coriacea (Mast.) Burret, Calamus deërratus G.Mann & H.Wendl. and Drypetes sp. These plants are used for a variety of purposes, most frequently as hunting luck, psychoactive for improving the dog’s scent and capacity for hunting, materials for traps, and remedies for attracting animals and for making the hunter courageous.

Conclusion

Plants used for hunting purposes here are embedded in a complex ecological and cultural context based on morphological characteristics, plant properties and local beliefs. This study provides a preliminary report and leaves room for further investigations to improve the documentation of the traditional knowledge systems of the studied community.

Keywords: Baka hunter-gatherers, Hunting, Fishing, Ethnobotanical knowledge, Cameroon

Introduction

Baka hunter-gatherers heavily depend on wild forest resources (plants, animals) to meet their subsistence and cash income needs. Some studies in several sites have shown that they have a well-developed traditional knowledge of using plants for a variety of purposes including not only for direct material uses as food, medicines, craft and building materials hunting, and fishing but also for religious practices [1–8]. Hunting and fishing by the Baka hunter-gatherers are very important activities from ecological, social and cultural points of view, and bushmeat is among their most preferred food [9]. Although they are traditionally spear hunters [10], they have experienced through time a diversity of techniques and methods for hunting and fishing including snare hunting for medium-sized mammals, mouse traps, use of fire to smoke prey animals out of burrows, dam fishing, fish-poisoning, hunting with dogs, machetes ad catapults, as well as hunting with shotguns, from sedentary or migratory camps, etc. [11–16].

Various studies have also reported the use of plants and plant products for fishing and hunting. Previous studies reported up to 325 fish poison species used in tropical Africa, the most frequently used being Tephrosia vogelii Hook.f., Mundulea sericea (Willd.) A.Chev., Euphorbia tirucalli L., Gnidia kraussiana Meisn., Adenia lobata (Jacq.) Engl and Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile [17]. Many of these species were also reported as used for preparing arrow poisons and traditional medicine. Hunting of the Baka people not only involves the direct use of poisonous plants and weapons such as gun, nets, spear, bows and traps. It also involves the use of dogs, especially the use of plant medicine for improving the dogs’ hunting ability, and for a variety of hunting rituals. While ethnobotanical knowledge of the Baka hunter-gatherers has been investigated by several authors, comprehensive documentation on the use of plants for hunting is still lacking.

In the face of the recent shift in the Bakas’ subsistence activity from hunting and gathering to farming, the change in their lifestyle and the development of education support projects, anthropologists and activists working for indigenous issues have expressed their concern about the risks of degradation of traditional ecological knowledge among Baka hunter-gatherers. Indeed, it seems that fewer Baka people are now involved in traditional hunting and gathering activities. [18] emphasize that the creation of national park and forest concessions are the factors that limited the access of Baka members to hunting. However, previous studies show that a number of socio-economic variables influence traditional ecological knowledge among indigenous communities. These variables include age, gender, consumerism, occupation, and psychosocial variables [19–24].

.These studies, depending on the scale of analysis, pointed out significant differences on national and continental levels. On the global level, however, no significant difference was reported between women and men. Concerning the age variable, several studies reveal that youth are reported to show a greater diversity of plant knowledge [22, 25]. The present research aims at documenting the diverse uses of plants in hunting practices among the Baka community members in Eastern Cameroon. We hypothesize that the ethnobotanical hunting knowledge of Baka hunter-gatherers is rich and varies with age and gender.

Material and methods

Study site

The study was conducted in six villages along the road from Abong Mbang to Messok: Bitsomo (3.14785 N, 13.65072E), Nomedjo (3.34169 N, 13.59048 E), Adjela Baka (3.15397 N, 13.61487 E), Sissok (3.147857 N, 13.65072E), Payo (3.14569 N, 13.70801E) and Bosquet (3.12655 N,13.88085E) (Fig. 1). These villages are located in the Lomie council, in the Haut Nyong Division of, East Cameroon Region. The total population of the council is approximately 19,000 inhabitants [26]. The local population consists of four main ethnic groups: Zime, Kako, Ndjeme and the Baka, living along the side road and speaking the Baka language. They are mainly Christians and Muslims [26]. The predominant forms of their livelihoods are shifting cultivation, cacao garden cultivation, hunting, fishing and gathering. Various, NTFPs (Non-Timber Forest Products) are collected and sold.

Fig. 1.

Location of study villages

The vegetation of the area is part of the camerouno-congolian forest consisting of a semi-deciduous forest comprised of a majority of Malvaceae and Ulmaceae [27, 28].

The area is subject to a Guinean equatorial climate with four seasons divided as follows: a long dry season from December to mid-March; a short rainy season from mid-March to June; a short dry season in July–August; a long rainy season from August to November. The mean annual rainfall varies from 1500 to 2000 mm, with an average temperature of 24 °C.

Research methods

Sampling and data collection approach

The ethnobotanical approach applied in this study used focal group discussion, interviews and field surveys in the forest, with 165 Baka members from the six study villages (Table 1). These villages were chosen based on the presence of an important Baka community and the prior consent given by the Chief of the village. Respondents in each village were chosen at random, based on their willingness to participate in the research.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

| Characteristics | Number of respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 90 | 54.55 |

| Women | 75 | 45.45 |

| Age group | ||

| 10–20 years | 36 | 21.82 |

| 20–30 years | 55 | 33.33 |

| 30–40 years | 27 | 16.36 |

| 40–50 years | 19 | 10.91 |

| 50–60 years | 14 | 8.48 |

| + 60 years | 15 | 9.09 |

| Number of years of school attendance | ||

| No school attendance | 17 | 10.30 |

| 1–3 years | 62 | 37.58 |

| 4–6 years | 71 | 43.03 |

| 7–10 years | 15 | 9.91 |

During the focal group discussion, it was clearly explained to the community members that the objective of the study was to record the plants used for hunting and fishing practices according to age and gender to obtain their prior informed oral consent. Individual interviews were conducted to gather information on their experience of using plants in hunting and fishing practices. Respondents were asked about their age, gender, hunting methods employed, local names of plants used in hunting activities, parts used, and usage. To obtain effective participation of respondents, interviews were conducted in the local language with the help of local translators.

The interviews were followed by fieldwork in the forest, which gave an opportunity for more discussions with respondents. This was also an opportunity to observe and gather information on the plant species free-listed by respondents. Plants named during the interviews were identified in situ in the field using available floral reference literature [29–32]. Plants that were spontaneously found when walking in the forest were also considered and information on their uses was recorded. For each unidentified plant species cited during the interview in the village, a specimen was collected, pressed and dried, and their identification was confirmed at the Cameroon National Herbarium in Yaoundé (YA). The voucher specimen was kept at Millennium Ecological Museum Herbarium and at the National Herbarium in Yaounde. Some of the plants listed by respondents during the interviews were not found during the forest walks and remained unidentified. These plants referred to as ethnospecies in the present study also included those that were known in their uses category, but the respondent was not able to remember the vernacular name.

Data analysis

Simple descriptive statistics were applied to represent and list the number and percentage of species of plants and plant parts used. The floral list of plants cited by respondents was grouped based on their age and gender. The frequency of citation (F) for each hunting and fishing technique and species was calculated. It corresponds to the ratio between the number of respondents (n) having cited the technique or species and the total number of respondents (N):

The magnitude of plant knowledge among each group (represented by the total number of plants cited) was used as a measurement of ethnobotanical knowledge. NNESS similarity index between the lists of plant species cited by each group was used as means of comparison.

This index is used to compare with minimum bias the degree of similarity of two samples (i and j) on the basis of an identical data size k randomly selected from each sample. The similarity between the two samples (i and j) is expressed by the Morisita-Horn index and by its generalization, the NNESS index, which is a variant of the NESS index [33]. The formula is given below and was computed using the software BiodivR 1.0 [34].

where ESS ij/k is the expected number of species shared for random draws of k specimens from sample i and k specimens from sample j. The more the value is close to 1, the more the pairs of species lists compared are floristically similar. Values above 0.5 can denote a great number of similar species shared by the two lists.

Results

Hunting techniques

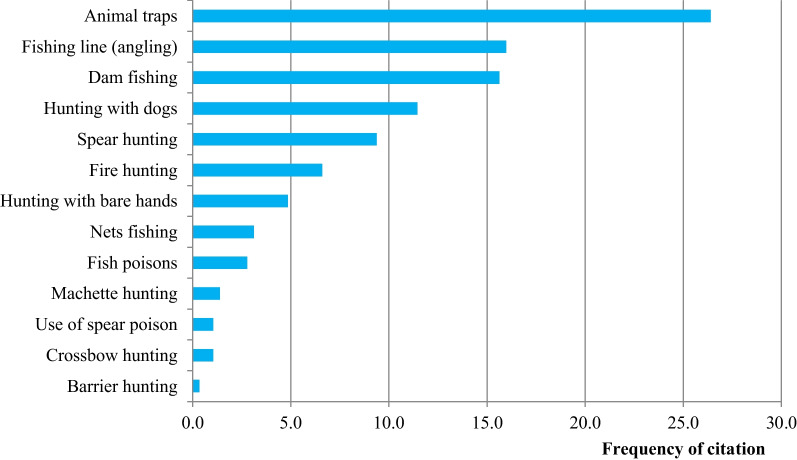

The results showed a total of 13 hunting techniques used by the Baka hunter-gatherers. The most frequently used techniques are animal traps, fishing lines, dam fishing, hunting with dogs and spear hunting (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Frequently used hunting techniques

Plant species used in hunting practices

A total of 176 plant species were recorded as used in the various hunting practices from the interviews with the Baka. The cumulative diagram of plant species recorded showed that the sampling size was adequate, as new species were hardly added despite the increase in the number of persons interviewed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cumulative diagram of plant species listed by interviewees

The most frequently cited species were Zanthoxylum gilletii (De Wild.) P.G.Waterman, Greenwayodendron suaveolens (Engl. & Diels) Verdc., Microcos coriacea (Mast.) Burret, Calamus deerratus G.Mann & H.Wendl and Drypetes sp. (Table 2). While the rattan species identified during the survey was Calamus deerratus, respondents insisted that all rattan species can be used as well.

Table 2.

List of recorded plant species used by Baka hunter-gatherers in hunting practices

| Scientific name | Familly | Vernacular name (in Baka) | Voucher number | Part used | Usage | Frequency of citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zanthoxylum gilletii (De Wild.) P.G.Waterman | Rutaceae | Bolongo, Ntawolo, Apouo'o, Njo'o | Nana P. 36 | Stem, leaves | Stems are used as fish poison and leaves are used to bring luck | 7.85 |

| Greenwayodendron suaveolens (Engl. & Diels) Verdc | Annonaceae | Botounga | de Wilde J.J.F.E. 7940 | Stem, bark | Barks are used to bring luck and to attract animals, stems are used as trap lever, to attract animals and to bring luck | 7.74 |

| Microcos coriacea (Mast.) Burret | Malvaceae | Bokou | Webb J. 05 | Fruit, bark | Fruits and barks are used as fish poison | 6.14 |

| Rattan | Arecaceae | kpongo | Raynal J. 10,548 | Stem | Stems are used to make baskets to carry catches and to make lobster pot | 4.89 |

| Drypetes sp. | Putranjivaceae | Kpwasso'o | Letouzey R. 12,210 | Leaves, stem | Leaves are used to increase dog’s hunting performance or to bring luck, stems are used as trap lever | 3.75 |

| Microdesmis puberula Hook.f. ex Planch | Pandaceae | Pipi/Fifi | Lejoly J. 899 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 3.64 |

| Desbordesia glaucescens (Engl.) Tiegh | Irvingiaceae | Solia | Nkongmeneck B.-A. 392 | Bark, stem | Barks used to bring luck, attract animals or get courage, stems used as trap lever | 2.84 |

| Ataenidia conferta (Benth.) Milne-Redh | Marantaceae | Boboko | Breteler F.J. 789 | Leaves | Use in chasing water during dam fishing | 2.73 |

| Diospyros hoyleana F.White | Ebenaceae | Bokembé | Letouzey R.573 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever, Barks use to have courage and to become invisible, stem used to make spear | 2.62 |

| Massularia acuminata (G.Don) Bullock ex Hoyle | Rubiaceae | Mindo | Thomas D.W. 6939 | Stem, leaves | Stems used as trap lever; leaves used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 2.05 |

| Asystasia gangetica (L.) T.Anderson | Acanthaceae | Apouo'o | Thomas D.W. 6769 | Leaves | Leaves are used as fish poison | 1.82 |

| Haumania danckelmaniana (J.Braun & K.Schum.) Milne-Redh | Marantaceae | Kpwasele | Letouzey R. 3652 | Leaves, stem | Leaves and stems are used to bring luck, stems are also used as trap lever and to attract animals, leaves are used in chasing water during dam fishing and to give drug to dog's | 1.71 |

| Heisteria zimmereri Engl | Olacaceae | Molomba, Modobalomba | Stem, bark | Stems are use as trap lever; bark are used to bring luck | 1.59 | |

| Landolphia heudelotii A.DC | Apocynaceae | Mokendjo | Breteler F.J. 2158 | Leaves, stem, fruit | Leaves are used to get courage, Stems are used to make spear, fruits are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 1.59 |

| Sloetiopsis usambarensis Engl | Moraceae | Ndoundoun | Cheek M. 8846 | Stem, root, bark and leaves | Stems and roots are used as trap lever, barks are used to bring luck, leave are used to get courage | 1.48 |

| Anonidium mannii (Oliv.) Engl. & Diels | Annonaceae | Gbwé | Thomas D.W. 7641 | Bark, leaves | Barks are used to be invisible; leave are used to attract animals | 1.37 |

| Brenania brieyi (De Wild.) E.M.A.Petit | Rubiaceae | Molondjo | Thomas D.W. 8743 | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 1.37 |

| Erythrophleum suaveolens (Guill. & Perr.) Brenan | Fabaceae | Mbanda | Sonké B. 999 | Stem, bark | Stems and barks are used to bring luck, to increase dog's hunting performance, to avoid to meet ferocious animals and as fish poison | 1.37 |

| Tabernaemontana crassa Benth | Apocynaceae | Pandor | Thomas D.W. 7575 | Stem, bark, leaves | Stems are used to attract animals, Barks and leaves are used to bring luck | 1.37 |

| Alchornea floribunda Müll.Arg | Euphorbiaceae | Yando | Nemba 104 | Root, leaves, stem | Root and stem are used to bring luck, leaves are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 1.02 |

| Baillonella toxisperma Pierre | Sapotaceae | Mabé | Letouzey R. 2805 | Stem, fruit pulp, bark | Stems are used to make gun and to become invisible, fruit pulps are used as fish poison and barks are used to attract animals | 1.02 |

| Strophanthus gratus (Wall. & Hook.) Baill | Apocynaceae | Nea | Onana J.-M. 115 | Bark, sap | Barks and saps are used as spear poison | 0.91 |

| Terminalia superba Engl. & Diels | Combretaceae | Ngoulou | Thomas D.W. 6065 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.91 |

| Xylopia sp. | Annonaceae | Koulou, Mpoulou | Thomas D.W. 4878 | Stem | Stems are used to become invisible, to bring chance and protection and as fish poison | 0.91 |

| Acacia pennata (L.) Willd | Fabaceae | Mpala | Letouzey R. 10,603 | Leaves | Leaves are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.8 |

| Annickia chlorantha (Oliv.) Setten & Maas | Annonaceae | Efoué | Endengle E. 87 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.8 |

| Cylicodiscus gabunensis Harms | Fabaceae | bolouma | Letouzey R. 10,063 | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.8 |

| Barteria nigritiana Hook.f | Passifloraceae | Fambo | Letouzey R. 12,458 | Bark | Barks are used to have luck and to attract animals | 0.68 |

| Manniophyton fulvum Müll.Arg | Euphorbiaceae | Coussa | Leaves, stem | Leaves are used to have luck; stems are used to make baskets to carry catches | 0.68 | |

| Rourea obliquifoliolata Gilg | Connaraceae | Mongassa | Koufani A. 32 | Stem, bark | Stems are used to make spear and as trap lever, barks are used to get courage | 0.68 |

| Scleria boivinii Steud | Cyperaceae | Tiyéyé | Kaji M. 254 | Stem, leaves, root | Stems, leaves and roots are used to bring luck | 0.68 |

| Alstonia boonei De Wild | Apocynaceae | Gouga | Nana P. 398 | Sap,bark, stem | Saps are used to bring luck, barks are used to attract animals, young stems are used to make shaft | 0.57 |

| Cleistopholis glauca Pierre ex Engl. & Diels | Annonaceae | Molombo | Tamaki 79 | Bark | Barks used as fish poison | 0.57 |

| Geophila cordifolia Miq | Rubiaceae | Djakelem | Letouzey R. 13,922 | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.57 |

| Klainedoxa gabonensis Pierre ex Engl | Irvingiaceae | Mongasa | Thomas D.W. 6761 | Stem, bark | Stems are used to make spear; barks are used to have power | 0.57 |

| Leptactina congolana (Robbr.) De Block | Rubiaceae | Nyambanou | Manning S.D. 1044 | Leaves | Leaves are used to become invisible | 0.57 |

| Triplochiton scleroxylon K.Schum | Malvaceae | Gwado | Mpom B. 245 | Bark, leaves | Barks are used as spear poison and to bring luck, leaves are used to bring luck | 0.57 |

| Turraeanthus africanus (Welw. ex C.DC.) Pellegr | Meliaceae | Assama | Cheek M. 9048 | Bark, leaves | Barks and leaves are used as fish poison | 0.57 |

| Albizia sp. | Esa'a | Villiers J.-F. 4750 | Bark | Barks are used to attract animals | 0.46 | |

| Capsicum frutescens L | Solanaceae | Alamba | Westphal 10,028 | Root, fruit, stem | Roots are used to bring luck, stems are used to attract animals, fruits are used to take the animal out of the hole | 0.46 |

| Clausena anisata (Willd.) Hook.f. ex Benth | Rutaceae | Toukoussa | Letouzey R. 4350 | Stem | Stems are used to bring luck/leaves are used to avoid to meet ferocious animals | 0.46 |

| Cleistopholis patens (Benth.) Engl. & Diels | Annonaceae | Kiyo afane | Letouzey R. 10,523 | Bark | Barks are used to get courage | 0.46 |

| Irvingia gabonensis (Aubry-Lecomte ex O'Rorke) Baill | Irvingiaceae | Péké | Letouzey R. 11,401 | Bark, stem | Barks are used to attract animal; stems are used to make fishing rod | 0.46 |

| Myrianthus arboreus P.Beauv | Urticaceae | Ngata | Nana P. 368 | Leaves | Leaves are used to attract animals | 0.46 |

| Pentaclethra macrophylla Benth | Fabaceae | Balaka | Leeuwenberg A.J.M. 9870 | Stem, bark, fruit | Stems are used as trap lever; barks are use as fish poison and fruits are used to attract animals | 0.46 |

| Piptadeniastrum africanum (Hook.f.) Brenan | Fabaceae | Koungou | Nemba 122 | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck and to increase dog's hunting performance | 0.46 |

| Pterocarpus soyauxii Taub | Fabaceae | Nguèlè | Bos 3272 | Stem, bark | Barks are used to bring luck; stems are used as trap lever | 0.46 |

| Ricinodendron heudelotii (Baill.) Heckel | Euphorbiaceae | Gobo | Leeuwenberg A.J.M. 5970 | Bark | Barks are used to attract animals and to bring luck in fishing | 0.46 |

| Strombosia pustulata Oliv | Olacaceae | Bobongo | de Wilde J.J.F.E. 8218 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.46 |

| Tetrapleura tetraptera (Schumach. & Thonn.) Taub | Fabaceae | Djaga | Mpom B.15 | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.46 |

| Anopyxis klaineana (Pierre) Engl | Rhizophoraceae | Eboma | Bark | Barks are used to attract animals and to have luck | 0.45 | |

| Afrostyrax lepidophyllus Mildbr | Huaceae | Nguimba | Letouzey R. 18,387 | Bark | Barks are used like hunt poison | 0.34 |

| Bombax buonopozense P.Beauv | Malvaceae | Ntombi | Villiers J.-F. 703 | Used to bring luck | 0.34 | |

| Diospyros sp. | Ebenaceae | Bokembé | Thomas D.W. 7209 | Stem | Stems used as trap lever, Barks use to have courage and to become invisible, stem used to make spear | 0.34 |

| Entandrophragma cylindricum (Sprague) Sprague | Meliaceae | Boyo | Breteler F.J. 2697 | Stem | Stems are used to make gun | 0.34 |

| Lepidobotrys staudtii Engl | Lepidobotryaceae | Wassassa | Letouzey R. 3900 | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.34 |

| Leptaspis zeylanica Nees ex Steud.//Leptaspis coclheata | Poaceae | Dingwélingwé | Jacques-Félix H. _&27 | Leaves | Leaves are used to get courage, | 0.34 |

| Panda oleosa Pierre | Pandaceae | Kana | Letouzey R. 43,237 | Bark, stem | Barks are used to attract animals; stems are used as trap lever | 0.34 |

| Psychotria cyanopharynx K.Schum | Rubiaceae | Mbongo | Letouzey R. 10,554 | Leaves, fruit | Leaves are used to increase dog's hunting performance; fruits are used as fish poison | 0.34 |

| Strombosiopsis tetrandra Engl | Olacaceae | Bossiko | de Wilde J.J.F.E. 8250 | Fruit, stem | Fruits are used to increase dog's hunting performance; stems are used as trap lever | 0.34 |

| Ficus platyphylla Delile | Moraceae | Ekom | Villiers J.-F. 1398 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.33 |

| Bikinia letestui (Pellegr.) Wieringa | Fabaceae | Ngassa | Cheek M. 8823 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.23 |

| Campylospermum elongatum (Oliv.) Tiegh | Ochnaceae | Kpwadjelé | Asonganyi J.N. 229 | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck and to attract animals | 0.23 |

| Celtis zenkeri Engl | Cannabaceae | Ngombé | Amshoff G.J.H. 6227 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.23 |

| Diospyros crassiflora Hiern | Ebenaceae | Lémbé | Letouzey R. 4785 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.23 |

| Entandrophragma utile (Dawe & Sprague) Sprague | Meliaceae | Gbwokoulou | Letouzey R. 12,017 | Stem | Stems are used to make gun | 0.23 |

| Eremospatha wendlandiana Dammer ex Becc | Arecaceae | Nkao'o | Letouzey R. 4151 | Stem | Stems are used to make lobster pot | 0.23 |

| Fire | Wa'a | Fires are used to take the animal out of the hole | 0.23 | |||

| Gilbertiodendron dewevrei (De Wild.) J.Léonard | Fabaceae | Bokou | Letouzey R. 1736 | Fruit, bark | Fruits and barks are used as fish poison | 0.23 |

| Hylodendron gabunense Taub | Fabaceae | Lando'o | de Wilde J.J.F.E. 8214 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.23 |

| Irvingia sp. | Irvingiaceae | Nto'o | Bullock S.H. 520 | Bark | Barks are used to become invisible | 0.23 |

| Manihot esculenta Crantz | Euphorbiaceae | Boma | Westphal 8933 | Tuber | Tubers are used to increase dog's hunting performance | 0.23 |

| Mimosa invisa Mart. ex Colla | Fabaceae | Nkenkeguili | Westphal 9836 | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.23 |

| Musanga cecropioides R.Br. ex Tedlie | Urticaceae | Kombo | Leeuwenberg A.J.M. 6713 | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.23 |

| Pericopsis elata (Harms) Meeuwen | Fabaceae | Mobaye | Letouzey R. 12,099 | Bark | Barks are used to get courage | 0.23 |

| Pollia condensata C.B.Clarke | Commelinaceae | Salabimbi | Kengué 11 | Leaves, stem | Leaves and stems are used to bring luck | 0.23 |

| Pycnanthus angolensis (Welw.) Warb | Myristicaceae | Etingue | Letouzey R. 178 | Bark | Barks are used to attract animals | 0.23 |

| Terminalia sp. | Combretaceae | Ngindi | Nana P. 400 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.23 |

| Triplophyllum protensum (Sw.) Holttum | Tectariaceae | Ndélé, Edélé | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.23 | |

| Adenia cissampeloides (Planch. ex Hook.) Harms | Passifloraceae | Poulou | Letouzey R. 9250 | Stem | Stems are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Aframomum sp. | Zingiberaceae | Nji'i | Thomas D.W. 3054 | Leaves | Leaves are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.11 |

| Anthocleista schweinfurthii Gilg | Gentianaceae | Eba | Bos 5686 | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Capsicum sp. | Solanaceae | Alamba | Westphal 9884 | Root, fruit, stem | Roots are used to bring luck, stems are used to attract animals, fruits are used to take the animal out of the hole | 0.11 |

| Ceiba pentandra (L.) Gaertn | Malvaceae | Baoba | Bamps P.R.J. 1448 | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Celtis adolfi-friderici Engl | Cannabaceae | Kakala | Breteler F.J. 2456 | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Cola nitida (Vent.) Schott & Endl | Malvaceae | Bolouga | Nkongmeneck B.-A. 106 | Fruit | Fruits are used to get courage | 0.11 |

| Cordia africana Lam | Boraginaceae | Mbabi | Satabié B. 173 | Bark | Barks are used to become invisible | 0.11 |

| Coula edulis Baill | Olacaceae | Npkombo | de Wilde J.J.F.E. 8218 | Stem, bark | Stems are used to stop water during dam fishing, barks are used to bring luck and to get courage | 0.11 |

| Detarium macrocarpum Harms | Fabaceae | Mili | Biholong M. 50 | Fruit | Fruits are used as fish poison | 0.11 |

| Distemonanthus benthamianus | Sele | de Wilde J.J.F.E. 7969 | Used to become invisible | 0.11 | ||

| Drypetes gossweileri S.Moore | Putranjivaceae | Ebomaka | Letouzey R. 4423 | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Elaeis guineensis Jacq | Arecaceae | Bila | Fruit | Fruits are used to bring luck | 0.11 | |

| Entandrophra sp. | Meliaceae | Eboyo | Nemba 481 | Leaves | Leaves are used to increase dog's hunting performance | 0.11 |

| Gambeya africana (A.DC.) Pierre | Sapotaceae | Sasagoulou | Letouzey R. 9282 | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Hunteria umbellata (K.Schum.) Hallier f | Apocynaceae | Mototoko | de Wilde J.J.F.E. 8371 | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.11 |

| Hypselodelphys zenkeriana (K.Schum.) Milne-Redh | Marantaceae | Ligombe | Breteler F.J. 1043 | Root | Roots are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Leplaea cedrata (A.Chev.) E.J.M.Koenen & J.J.de Wilde | Meliaceae | Mbegna | Mpom B. 24 | Bark | Barks are used to get courage | 0.11 |

| Lonchitis hirsuta L | Lonchitidaceae | Gobouma | Bark | Barks are used to attract animals | 0.11 | |

| Maesopsis eminii Engl | Rhamnaceae | Kanga | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.11 | |

| Mangifera indica L | Anacardiaceae | Manguier | Mpom B. 22 | Root | Roots are used to increase dog's hunting performance | 0.11 |

| Maranthes glabra (Oliv.) Prance | Chrysobalanaceae | Mbokandja | de Wilde W.J.J.O. 2652 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever and to make spear | 0.11 |

| Meiocarpidium oliverianum (Baill.) D.M.Johnson & N.A.Murray | Annonaceae | Mabelengue | Letouzey R. 10,153 | Stem | Stems are used to make spear | 0.11 |

| Milicia excelsa (Welw.) C.C.Berg | Moraceae | Bangui | Thomas D.W. 6869 | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Morelia senegalensis A.Rich. ex DC | Rubiaceae | Edjé | Letouzey R. 2886 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.11 |

| Musa sp. | Musaceae | Moundédé | Raynal J. 10,776 | Fruit | Fruits are used to attract animals | 0.11 |

| Nicotiana tabacum L | Solanaceae | Ndako | Swarbrick 213 | Leaves | Leaves are used to attract animals | 0.11 |

| Omphalocarpum sp. | Sapotaceae | Ngwadjala | Thomas D.W. 7917 | Leaves | Leaves are used to get courage | 0.11 |

| Pauridiantha pyramidata (K.Krause) Bremek | Rubiaceae | Ngwa'a | Letouzey R. 1696 | Leaves | Leaves are used as fish poison | 0.11 |

| Persea americana Mill | Lauraceae | Avocatier | Ekema 09 | Leaves | Leaves are used to have luck | 0.11 |

| Piper umbellatum L | Piperaceae | Mbebelembe | Nkongmeneck B.-A. 877 | Stem | Stems are used to make fire | 0.11 |

| Raphia sp. | Arecaceae | Letouzey R. 15,260 | Stem | Stems are used to make baskets to carry catches and to make lobster pot | 0.11 | |

| Santiria trimera (Oliv.) Aubrév | Burseraceae | Ebaba, Libaba | Letouzey R. 4684 | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck and to increase dog's hunting performance | 0.11 |

| Scottellia klaineana Pierre | Achariaceae | Kpwomboseko | Letouzey R. 5057 | Bark | Barks are used to have luck | 0.11 |

| Sida rhombifolia L | Malvaceae | Ntadanda | Breteler F.J. 278 | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Sterculia oblonga Mast | Malvaceae | Mboyo | Thomas D.W. 4945 | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Trichosypha sp. | Anacardiaceae | Ngoyo'o | Nemba 15 | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.11 |

| Not identified | Adama | Bark | Barks are used as fish poison | 0.68 | ||

| Not identified | Molombi | Root, bark, stem, leaves | Roots, barks, stems and leaves are used to become invisible | 0.68 | ||

| Not identified | Marantaceae | Gwasa'a | Lowe J. 3107 | Leave | Leaves are used for chasing water during dam fishing and for packaging products | 0.34 |

| Not identified | Mentem | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.34 | ||

| Not identified | Gbwo | Fruit | Fruits are used to increase dog's performance | 0.23 | ||

| Not identified | Meningoumbe | Stem | Stems are used to make lobster pot | 0.23 | ||

| Not identified | Alokou | Bark, leave | Barks and leaves are used as fish poison | 0.23 | ||

| Not identified | Moloundou | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog' hunting performance and to get courage | 0.23 | ||

| Not identified | Ngalé | Bark | Barks are used as fish poison | 0.23 | ||

| Not identified | Mindoundoun | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.23 | ||

| Not identified | Djouendjel | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Etoa | Stem | Stems are used as fish poison | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 1 | Used to get courage | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Mapembey | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Npossa | Leave | Leaves are used as container | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 2 | Used to make baskets to carry catches | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Bokobogwamé | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 3 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Kouma | Used to become invisible | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Gkouelo | Stem | Stems are used to make spear | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Gwandjaka | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Gwi | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Kouogouo | Stem | Stems are used to make lobster pot | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Kpobala | Leaves | Leaves are used to increase dog's hunting performance | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 4 | Used to increase dog's hunting performance | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Adia | Leaves | Leaves are used to increase dog's hunting performance | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Lo'o | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ma'a | Stem | Stems are used to bring luck | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Messini | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Metonga | Bark | Barks are used to become invisible | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Moboumso | Stem | Stems are used to bring luck | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Mokope | Bark | Barks are used to get courage | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Mongola | Stem | Stems are used to take animals out of the hole | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Mototombo | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Nkenkeguili | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Bekesso | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Npoh | Bark | Barks are used to bring luck | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Nto'o | Bark | Barks are used to become invisible | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Simbo | Stem | Stems are used to become invisible | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 5 | Stem | Stems are used as trap lever | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 6 | Stem | Stems are used to bring luck | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 7 | Used as fish poison | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 8 | Used to bring luck | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 9 | Used to get courage | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 10 | Used to bring luck | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 11 | Used to get courage | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 12 | Used to make lobster pot | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 13 | Used to bring luck | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Bolombi | Used to become invisible | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Eke | Stem | Stems are used to make baskets to carry catches | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Gwabotouga | Leaves | Leaves are used to bring luck | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ngokele | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Eloukou | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Gomabolo | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 14 | Used to make baskets to carry catches | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Mbaté | Bark | Barks are used to attract animals | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Molondo | Bark | Barks are used to increase dog’s hunting performance | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Njombo | Bark | Barks are used to get courage | 0.11 | ||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 15 | Used to increase dog's hunting performance | 0.11 | |||

| Not identified | Ethnospecies 16 | Used to get courage | 0.11 |

These plants were used for a variety of purposes including materials for making traps, baskets for transportation, arrow poison, fish poison, etc. (Fig. 4). Others were used in ritual practices aimed at becoming invisible to dangerous animals, attracting animals, or to have luck when going out for a hunting expedition. Others were used directly by the hunter to be courageous or to chase away dangerous animals. The use of dogs was another technique of hunting widely used in the region, as well as in other continents. A variety of plant species were used for improving the scent and other abilities of dogs.

Fig. 4.

Numbers of plants and their usages for hunting and fishing

Variation in the ethnobotanical knowledge for hunting with age and gender

The comparative analysis of the extent of plant knowledge among respondent groups showed no significant difference between men and women, which indicates there is no gender-based pattern in the knowledge of plants used in hunting practices. The 75 women interviewed cited 122 plants, with a ratio of 1.62 plants per respondent, while the 90 men cited 174 plants, with a ratio of 1.92 per respondent. Concerning the effect of age, the largest number of plants was cited by the respondent group of 20–30 years old (109 plant species cited by 55 respondents). This might be partly explained by the larger size of this group interviewed. The highest ratio of plant citation per respondent is recorded in the age group 50–60 years where a total of 14 respondents cited as many as 73 species, with a ratio of 5.21 per respondent (Table 3).

Table 3.

Score of citation of plants by age groups

| Age group | No. of respondents | No. of plants cited | Ratio (number of plant citation/respondent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10–20 years | 36 | 89 | 2.47 |

| 20–30 years | 55 | 109 | 1.98 |

| 30–40 years | 27 | 75 | 2.78 |

| 40–50 years | 19 | 59 | 3.11 |

| 50–60 years | 14 | 73 | 5.21 |

| + 60 years | 15 | 47 | 3.13 |

The value of the NNESS similarity index between lists of plants cited by men and women was 0.68, indicating a certain degree of commonality between the two groups.

The plants listed by aged members (+ 60 years) were significantly different from those of other age groups, as this is shown by the NNESS values of 0.39, which means the most-aged groups cited fewer common species (Table 4).

Table 4.

NNESS similarity indices between the lists of plants cited by age groups

| NNESS(k = 50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 10–20 years | 20–30 years | 30–40 years | 40–50 years | 50–60 years | + 60 years |

| 10–20 years | 1.00 | |||||

| 20–30 years | 0.69 | 1.00 | ||||

| 30–40 years | 0.64 | 0.69 | 1.00 | |||

| 40–50 years | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 1.00 | ||

| 50–60 years | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 1.00 | |

| Above 60 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 1.00 |

Values in bold show pairs of age groups having greater differences in their lists of plants cited

The group of 10–20 years old and that of above 60 years shared only 25 common species. Of the 89 species cited by younger groups, 53 were not cited by the group of above 60 years. Among those non-common species, the most frequent are: Diospyros crassiflora Hiern, Massularia acuminata (G.Don) Bullock ex Hoyle, Acacia pennata (L.) Willd., Brenania brieyi (De Wild.) E.M.A.Petit, Cleistopholis glauca Pierre ex Engl. & Diels, Diospyros hoyleana F.White, Heisteria zimmereri Engl., Strophanthus gratus (Wall. & Hook.) Baill., Xylopia sp., Albizia sp., Alchornea floribunda Müll.Arg., Cleistopholis patens (Benth.) Engl. & Diels, Manniophyton fulvum Müll.Arg., Tabernaemontana crassa Benth. and Terminalia superba Engl. & Diels. On the other hand, of the 47 species cited by respondents above 60 years, 26 were not known by younger respondents aged between 10 and 20 years. They consist of the species like Landolphia heudelotii A.DC., Erythrophleum suaveolens (Guill. & Perr.) Brenan, Tetrapleura tetraptera (Schumach. & Thonn.) Taub., Barteria nigritiana Hook.f. and Manihot esculenta Crantz.

Discussion

In the study villages, the importance of plants in hunting and fishing practices is well established. The plant species recorded as used in hunting practices are taxonomically quite diverse. Some have been cited more frequently than others. A previous botanical survey in this peripheral site of the Dja biosphere reserve has reported wider distribution and abundance of these species in the study area [35]. Given this availability, the Baka peoples in the study villages may therefore preferentially use the plants that are readily available in their neighbourhood for hunting purposes. Hunting and fishing practices recorded in the studied villages are in line with those previously reported by other researchers [12, 36–39]. Some of the species recorded as used in fishing and hunting practices have been described to have similar uses in the previous ethnobotanical literature in central Africa [2, 8]. The use of Marantaceae (Megaphrynium macrostachyum and Ataenidia conferta (Benth.) Milne-Redh.) in dam fishing was previously reported by [39, 40] and [4]. Some of the recorded plants like Drypetes spp. and Greenwayodendron suaveolens have also been reported as used for making spears or snares by Baka hunter-gatherers in Cameroon [15]. The use of the barks of Zanthoxylum gilletiim (De Wild.) P.G.Waterman, Turraeanthus africanus (Welw. ex C. DC.) Pellegr. and the fruits of Microcos coriacea (Welw. ex C. DC.) Pellegr. as fish poison, the application of Desbordesia glaucescens (Engl.) Tiegh. to improve the chance of catching more animals as well as the use of Tetrapleura tetraptera (Schumach. & Thonn.) Taub. and Aframomum melegueta K. Schum. to improve the performance of dogs in hunting have been documented by several authors in Central Africa as well as in West Africa and south America [39–41]. Natural poisons derived directly from plants have been used in fishing for millennia [42, 43], poisonous ingredients are pounded and thrown into a pool or dammed sections of a small river. After a time, which varies according to conditions the fish begin to rise to the surface of the water and can readily be taken by hand [17]. Several studies have shown that these poisons have no effect on human health, humans can digest it relatively safely [17, 44]. Although the consumption of preys killed with the natural poison has no effect on human health, [45] recorded an anaesthetic effect on limbs and roughness of skin of people who wade into streams to collect fish poisoned with Tephrosia vogelii Hook.f. These considerations should definitely be taken into account in the spread of these practices. The major problem in using fishing poisons is the massive destruction of aquatic organisms. Natural fish poisons paralyse or kill fish; sometimes, they kill other aquatic organisms; therefore, this practice has been banned in many contexts due to the ecological damage it can cause [17, 46].

Results of this study show that there is an uneven distribution of ethnobotanical knowledge for hunting within studied communities. Although the ratio of plant citation per respondent was higher among aged groups, similarity analysis shows that younger respondents cited a larger number of plant species used for hunting and fishing and that they named many plants that were not cited by the elders. These observations are contrary to those of [47] who reported that only adults can master hunting or medicinal plant knowledge. For instance, ethnobotanical knowledge acquisition process among the studied community involves plural channels and sources. It is acquired through contact with the people with different background, such as family members, schoolmates and neighbours of other ethnic groups, associated with their socialization process. Younger members of the community engage in a variety of game and subsistence-related activities. The Baka living on the periphery of the Dja biosphere are sedentary along the roads, so the young Baka interact with many other youths including Bantus of the similar age, and through this process of social contacts, there is a dynamic of recompositing of their original traditional knowledge acquired from their family members. In these dynamics, they accumulate their own ethnobotanical knowledge that extends beyond the scope of knowledge acquired within a narrow range of their own family. This observation is consistent with previous findings by [20] on the Baka in the same region of East Cameroon. Moreover, it is clearly established that traditional ecological knowledge transmission most often occurs between older and younger generations, or vertical instruction; it can also occur through more horizontal interactions between peers and through oblique transmission from non-familial mentors [48]. These different knowledge acquisition pathways were qualified as “multiple-stage learning process” by [49, 50].

From the similarity indices among the plant lists of different groups of respondents, it is shown that 68% of plant species recorded are shared between men and women. This commonality, however, masks finer gender differences. The social organization of the hunting activities involves both men and women who share the responsibilities. Although some of the hunting activities are performed by men, many of the rituals during which plants are used are performed by women and particularly virgin girls. In fact, from the discussion with respondents, it was revealed that according to the traditional beliefs within Baka society, the prayers and words sent to the ancestors to ask for luck require that the person sending the prayers be “pure”. For instance, virgin girls in Baka society are a symbol of good moral behaviour and conduct and thus of purity, as they have not yet engaged in sexual relationships considered as a sin that defiles the body of the person. Hence, they believe that their ancestors would be happy, answering to the will of virgin girls than that of any other person.

There are cases where women, especially elder members, play a key role in the transmission of ethnobotanical knowledge for hunting to men.

In such a context, ethnobotanical hunting knowledge acquisition within the studied communities might involve several individual and collective factors associated with their socialization process.

Conclusion

This study was conducted to document the traditional knowledge of plants used in hunting practices among the Baka community members in Eastern Cameroon. Results showed a taxonomic list of 176 species used by the studied populations. In the practice of hunting or fishing, these plants are used for a variety of purposes including as materials for making traps or baskets for transportation, arrow or fish poison, traditional medicine used by the hunter to be courageous or by the dogs to improve their scent and ability for hunting, materials for ritual practices performed to become invisible to dangerous animals, attract animals, to chase away dangerous animals or to have luck when going out for a hunting expedition.

Although female Baka are traditionally more active in fishing, they are knowledgeable of plants used for hunting as well. The ethnobotanical knowledge of using plants for hunting did not vary significantly with gender, but showed some variation among age groups, with younger members citing more plants than the elder. For further investigations, a comparative study with neighbouring Bantu communities will be important to understand the dynamics of inter-community knowledge exchange.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the people of the study villages for their supportive assistance and collaboration. We also thank M. Koue Djondandi and M. Francis Fosso Wafo for their involvement in data collection.

Author contributions

EFF, MTN and TO conceived and designed the study. The authors drafted the manuscript together. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (15H02598) of MEXT, Japan.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All the participants have been explained the process and nature of this project and asked to provide oral informed consent.

Consent for publication

All the participants have been explained the process and nature of this study and asked to provide oral informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dounias E. The management of wild yam tubers by the Baka pygmies in southern Cameroon. Afr Study Monogr. 2001;26:135–156. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisson R. Petit dictionnaire Baka-Français. 2002. 328 p.

- 3.Betti JL. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants among the Baka pygmies in the Dja biosphere reserve. Cameroon Afr Study Monogr. 2004;25(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hattori S. Utilization of Marantaceae plants by the Baka hunter-gatherers in southeastern Cameroon. Afr Study Monogr. 2006;33:29–48. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasuoka H. The wild yam question: evidence from Baka foraging in the northwest Congo basin. In: Gates DG, Tucker J, editors. Human ecology: contemporary research and practice. Berlin: Springer; 2010. pp. 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasuoka H. Dense wild yam patches established by hunter-gatherer camps: beyond the wild yam question, toward the historical ecology of rainforests. Hum Eco. 2013;41:465–475. doi: 10.1007/s10745-013-9574-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallois S, Heger T, Van Andel T, Sonké B, And Henry GA. From bush mangoes to bouillon cubes: wild plants and diet among the Baka, forager-horticulturalists from Southeast Cameroon. Econ Bot. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12231-020-09489-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallois S, Heger T, Henry AG, van Andel T. The importance of choosing appropriate methods for assessing wild food plant knowledge and use: a case study among the Baka in Cameroon. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0247108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichikawa M, Hattori S, Yasuoka H. Bushmeat crisis, forestry reforms and contemporary hunting among central African forest hunters. In: Pyhälä A, Reyes-García V, editors. Hunter-gatherers in a Changing world. New York: Springer; 2016. pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahuchet S. Dans la forêt d’Afrique Centrale. Les pygmées Aka et Baka. Peeters-Selaf, Paris-Louvain. 1992. 864 p.

- 11.Sato H. The Baka in Northwestern Congo: sedentary hunter-gatherers. In: Tanaka J, Kakeya M (eds.) Natural history of hulnan beings, Heibonsha, Tokyo (in Japanese). 1991, pp. 543–566

- 12.Hayashi K. Hunting activities in forest camps among the baka hunter-gatherers of Southeastern Cameroon. Afr Study Monogr. 2008;29(2):73–92. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasuoka H. The sustainability of duiker (Cephalophus spp.) hunting for the baka hunter-gatherers in southeastern Cameroon. Afr Stud Monogr. 2006;33:95–120. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasuoka H. Snare hunting among Baka hunter-gatherers: implications for sustainable wildlife management. Afr Study Monogr Suppl. 2014;49:115–136. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duda R. Ethnoecology of hunting in an empty forest. Practices, local perceptions and social change about the Baka (Cameroon). PhD dissertation. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, 2017. 299 p.

- 16.Oishi T, Mvetumbo M, Fongnzossie FE. Caring dogs for hunting among the Baka hunter-gatherers of southeastern Cameroon. Paper read at the twelfth international conference on hunting and gathering societies (CHAGS 12), July 25th 2018, the School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. 2018.

- 17.Neuwinger HD. Plants used for poison fishing in tropical Africa. Toxicon. 2004;44(4):417–430. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pemunta NV. Fortress conservation, wildlife legislation and the Baka Pygmies of southeast Cameroon. GeoJournal. 2019;84:1035–1055. doi: 10.1007/s10708-018-9906-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paniagua-Zambrana NY, Camara-Lerét R, Bussmann RW, Macía MJ. The influence of socioeconomic factors on traditional knowledge: a cross scale comparison of palm use in northwestern South America. Ecol Soc. 2014;19(4):9. doi: 10.5751/ES-06934-190409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallois S. Dynamics of local ecological knowledge: a case study among the Baka children of southeastern Cameroon. PhD dissertation, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelons. 2015. 354 p.

- 21.Tang R, Gavin MC. A classification of threats to traditional ecological knowledge and conservation responses. Conservat Soc. 2016;14:57–70. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.182799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallois S, Duda R, Reyes-García V. Local ecological knowledge among Baka children: A case of “children's culture. J Ethnobiol. 2017;37(1):60–80. doi: 10.2993/0278-0771-37.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller GJ, Boubacar R, Guimbo DI. The ‘how’ and ¨ ‘why’ of including gender and age in ethnobotanical research and community-based resource management. Ambio. 2014;44(1):67–78. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0517-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torres-Avilez W, MunizdeMedeiros P, Ulysses PA. Effect of gender on the knowledge of medicinal plants: systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine, 2016, 13 pages [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Dan Guimbo I, Muller J, Larwanou M. Ethnobotanical knowledge of men, women and children in rural Niger: a mixedmethods approach. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2011;9:235–242. doi: 10.17348/era.9.0.235-242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludeprena. Plan communal de développement de Lomié. PNDP. 2012. 134 p.

- 27.Letouzey R. Notice phytogéographique du Cameroun au 1:500000. Intitut de la Carte Internationale de la végétation, Toulouse, France. 1985. 240 p.

- 28.Achoundong G. Les Rinorea comme indicateurs des grands types forestiers du Cameroun. The Biodiversity of African Plants. 1996. pp 536–544.

- 29.Vivien J, et Faure JJ,. Arbres des forêts denses d’Afrique centrale. Saint Berthevin, France. 1985. 945p.

- 30.Wilks CM. et Issembé Y. Guide pratique d’identification des arbres de la guinée équatoriale, région continentale.Projet CUREF Bata Guinée Equatoriale. 2000. 546 p.

- 31.Letouzey R. Manuel de botanique forestière. Afrique tropicale, CTFT, Tome 2A et 2B, Nogent-sur-Marne : GERDAT-CTFT. 1982. 864 p.

- 32.Thirakul S. Manuel de dendrologie, Cameroun. Groupe Poulin, Thériault Ltée, Québec, Canada, 1983. 640 p.

- 33.Grassle F, Simith W. A similarity measure sensitive to the contribution of rare species and its use in investigation of variation in marine benthic communities. Oecologia. 1976;25:13–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00345030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hardy O. BiodivR 1.0. A program to compute statistically unbiased indices of species diversity within samples and species similarity between samples using rarefaction principles. User’s manual. Laboratoire Eco-éthologie Evolutive, CP160/12. Université Libre de Bruxelles. 2005.5 p.

- 35.Sonké B. Forêts de la réserve du Dja (Cameroun), études floristiques et structurales. Scripta Botanica Belgica, 2005. vol 32, 144 p.

- 36.Sato H. Folk etiology among the Baka, a group of hunter-gatherers in the African rainforest. Afr Stud Monogr Suppl. 1998;25(33):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hattori S. Nature conservation and hunter gatherers’ life in Cameroonian rainforest. Afr Stud Monogr Suppl. 2005;29:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hattori S. Current issues facing the forest people in Southeastern Cameroon: the dynamics of Baka life and their ethnic relationship with farmers. Afr Study Monogr. 2014;47:97–119. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gallois S, Duda R. Beyond productivity: The socio-cultural role of fishing among the Baka of southeastern Cameroon. Revue d’ethnoécologie. 2016 doi: 10.4000/ethnoecologie.2818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takanori O. Ethnoecology and ethnomedicinal use of fish among the Bakwele of southeastern Cameroon. Revue d’ethnoécologie. 2016 doi: 10.4000/ethnoecologie.2893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett CB, Alarcón R. Hunting and hallucinogens: the use psychoactive and other plants to improve the hunting ability of dogs. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;171:171–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howes FN. Fish-poison plants. In: Bulletin of miscellaneous information (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew); Springer: Heidelberg, 1930; 4, 129–153

- 43.Béarez P. FOCUS: first archaeological indication of fishing by poison in a sea environment by the engoroy population at Salango (Manabı, Ecuador) J Archaeol Sci. 1998;25:943–948. doi: 10.1006/jasc.1998.0330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Andel T. The diverse uses of fish-poison plants in northwest Guyana. Econ Bot. 2000;54(4):500–512. doi: 10.1007/BF02866548. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nwude N. Plants poisonous to Man in Nigeria. Vet Hum Toxicol. 1982;24:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Von Von Brandt A. Brandt’s fish catching methods of the world. 4. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallois S, Lubbers JM, Hewlett B, Victoria R-G. Social networks and knowledge transmission strategies among baka children. Southeastern Cameroon Hum Nat. 2018;29:442–463. doi: 10.1007/s12110-018-9328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adekannbi J, Olatokun WM, Ajiferuke I. Preserving traditional medical knowledge through modes of transmission: a post-positivist enquiry. South African J Info Mgmt. 2014;16:1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reyes-García V, Demps K, Gallois S. A multistage learning model for cultural transmission: Evidence from three indigenous societies. In: Hewlett BS, Terashima H (eds) Social learning and innovation in contemporary hunter-gatherers: evolutionary and ethnographic perspectives. Springer, Japan. 2016. pp. 47–60

- 50.Schniter E, Gurven M, Kaplan HS, Wilcox NT, Hooper PL. Skill ontogeny among Tsimane forager-horticulturalists. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2015;158:3–18. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.