Abstract

Early cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease may result in part from synaptic dysfunction caused by the accumulation oligomeric assemblies of amyloid β-protein (Aβ). Changes in hippocampal function seem critical for cognitive impairment in early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Diffusible oligomers of Aβ (oAβ) have been shown to block canonical long-term potentiation (LTP) in the CA1 area of hippocampus, but whether there is also a direct effect of oAβ on synaptic transmission and plasticity at synapses between mossy fibers (axons) from the dentate gyrus granule cells and CA3 pyramidal neurons (mf-CA3 synapses) is unknown. Studies in APP transgenic mice have suggested an age-dependent impairment of mossy fiber LTP. Here we report that although endogenous AD brain-derived soluble oAβ had no effect on mossy-fiber basal transmission, it strongly impaired paired-pulse facilitation in the mossy fiber pathway and presynaptic mossy fiber LTP (mf-LTP). Selective activation of both β1 and β2 adrenergic receptors and their downstream cAMP/PKA signaling pathway prevented oAβ-mediated inhibition of mf-LTP. Unexpectedly, activation of the cGMP/PKG signaling pathway also prevented oAβ-impaired mf-LTP. Our results reveal certain specific pharmacological targets to ameliorate human oAβ-mediated impairment at the mf-CA3 synapse.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Aβ oligomers, Mossy fiber-CA3 synapse, Long-term potentiation, cAMP/PKA pathway, cGMP/PKG pathway

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a globally prevalent, age-related disorder characterized by extracellular deposits (amyloid plaques) of diverse assemblies of amyloid β-peptides (Aβ) as well as intraneuronal deposits (neurofibrillary tangles) of the microtubule-associated protein, tau. Neurofibrillary tangles, the abundance of which correlates with cognitive symptoms, are found initially in the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, amygdala and other limbic regions and later spread to neocortical regions. The severity of cognitive deficits correlates better with the levels of soluble forms of Aβ than with those of insoluble amyloid plaques (Lue et al., 1999; McLean et al., 1999). Experimentally, aqueously soluble oligomers of Aβ (oAβ) have consistently been shown to block long-term potentiation (LTP) in the CA1 area of hippocampus, an extensively validated electrophysiological correlate of learning and memory (Gulisano et al., 2018; Lambert et al., 1998; Li et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019; Shankar et al., 2008; Walsh et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002).

Aβ-neutralizing and -clearing antibodies are currently emerging as the first potentially disease-modifying therapeutics for AD. Therefore, obtaining a deeper understanding of the molecular signaling and neurobiological mechanisms of β-amyloidosis becomes even more important for precision medicine in this highly common disease. To this end, we have conducted a novel analysis of the understudied dentate granule-mossy fiber-CA3 neuroanatomical pathway in the hippocampus and describe its vulnerability to impairment by oAβ obtained directly from human ((AD) brain.

The hippocampus has a crucial role in mammalian learning and memory. The main input to the hippocampus is provided by the dentate gyrus (Nicoll and Schmitz, 2005). Information reaches neurons of the CA3 region through mossy fiber mf) synapses made by dentate granule cell axons that have been proposed to participate in the rapid encoding of contextual memories (Kesner, 2007; Nakashiba et al., 2008; Nakazawa et al., 2003; Lee and Kesner, 2004; Shahola et al., 2022), a mnemonic process particularly affected in AD patients. MF-CA3 synapses exhibit an important feature of presynaptic plasticity involving prominent short-term plasticity and a form of LTP that is independent of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (in contrast to canonical CA1 LTP) and requires activation of β-adrenergic receptors as well as downstream cAMP/PKA signaling cascades (Henze et al., 2002; Salin et al., 1996; Huang and Kandel, 1996). oAβ is already known to impair LTP in the CA1 area of hippocampus through the cAMP/PKA/CREB or cGMP/PKG/CREB pathways (see e.g., Vitolo et al., 2002; Puzzo et al., 2005). Several studies have observed an age-dependent impairment of mossy fiber LTP in APP transgenic mice, including for example 12 mo transgenic AAP/PS1 mice and 24 mo Tg2576 mice (Maingret et al., 2017; Witton et al., 2010). However, it is not possible to definitively attribute these changes in mice to oAβ per se, as heterogenous Aβ species and many secondary effectors are present in vivo. Here, we asked for the first time whether application of natural soluble oAβ species isolated directly from human (AD) cortex can affect mf-LTP in wild-type (WT) mouse hippocampal slices. We find that AD-brain-derived oAβ potently blocks mf-LTP and that this involves second-messenger pathways that include presynaptic cAMP/PKA and cGMP/PKG.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

Both male and female C57BL/6 J mice were used. All procedures involving mice were in accordance with the animal welfare guidelines of The Harvard Medical School and Brigham Women’s hospital.

2.2. Extracellular field recordings

Experiments were performed as previously described (Li et al., 2018). Briefly, mice (ages 1–3 mo) were anesthetized with halothane and decapitated. Transverse acute hippocampal slices (350 μm) were cut in ice-cold oxygenated sucrose-enhanced artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 206 mM sucrose, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM D-glucose, pH 7.4. After dissection, slices were incubated in ACSF that contained the following (in mM): 124 NaCl, 2 KCl, 2 MgSO4, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 10 D-glucose saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7.4), in which they were allowed to recover for at least 90 min before recording. Recordings were performed in the same solution at room temperature in a chamber submerged in ACSF. To record field EPSPs (fEPSPs) in the CA3 region of the hippocampus, standard procedures were used. A unipolar stimulating electrode (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) was placed in the hilus region close to the dentate granule cell layer to stimulate mossy fiber axons. A borosilicate glass recording electrode filled with ACSF was positioned in stratum lucidum of CA3, 250–350 μm from the stimulating electrode. AP5 (50 μM) was added in ACSF to prevent contamination with the NMDA receptor-dependent pathway converging on CA3 neurons. Test stimuli were applied at low frequency (0.05 Hz) at a stimulus intensity that elicited a fEPSP amplitude that was 40–50% of maximum and the test responses were recorded for 10 min before the experiment was begun to ensure stability of the response. Once a stable test response was attained, experimental treatments, 0.5 mL AD brain Tris-buffered saline (TBS) soaking extracts without or with various drugs were added to the 9.5 mL ACSF perfusate, and a baseline was recorded for an additional 30 min. For the Anti-Aβ antibodies experiments, the 71A1 or 1G5 antibodies were added to the AD brain extract aliquots incubated with mixing for 30 min, then adding to the mixture to brain slice perfusion buffer. To induce mf-LTP, two consecutive trains (1 s) of stimuli at 100 Hz separated by 20 s were applied to the slices. Traces were obtained by pClamp 11 and analyzed using the Clampfit 11. Data analysis was as follows. The fEPSP magnitude was measured using the initial fEPSP slope and three consecutive slopes (1 min) were averaged and normalized to the mean value recorded 10 min before conditioning stimulus. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. Significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA test with post hoc Tukey’s test or unpaired student’s t-test.

3. Results

3.1. oAβ from AD brain extracts alters short-term plasticity in the mossy fiber pathway and impairs mossy fiber LTP, and certain Aβ antibodies can prevent this

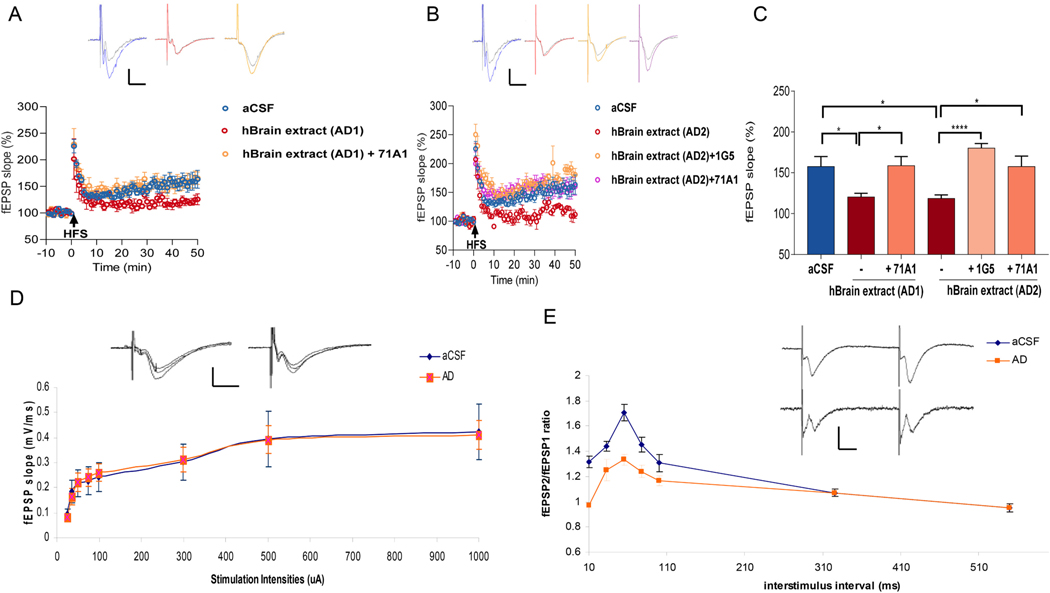

We demonstrated previously that AD brain-derived soluble Aβ oligomers (oAβ) consistently prevent LTP in the CA1 area of hippocampus (Shankar et al., 2008; Li et al., 2018; Hong et al., 2018). However, the effects of AD brain-derived soluble oAβ on LTP in the mossy fiber (mf) pathway, where axons (mossy fibers) project from DG granule cells to synapse on CA3 neurons, remain untested. We systematically assessed whether oAβ isolated from AD cerebral cortex alters mf-LTP in WT mouse hippocampal slices. We prepared AD cortical extracts (AD 1 and AD2) using the recently described 30-min “soaking” protocol on minced cortical bits, which avoids tissue homogenization that would break up myriad plaque cores and yields an aqueous extract enriched in highly diffusible, bioactive forms of oAβ (Hong et al., 2018). Addition of AD 1 or AD2 at 5% (v:v) to the aCSF slice perfusate resulted in significantly reduced mf-LTP compared to the aCSF control (Fig. 1). Recently, we reported that the strongly oligomer-preferring Aβ antibodies 71A1 and 1G5 protect against the oAβ-induced LTP block in CA1 of wt hippocampal slices (Liu et al., 2021). Here we found that 71A1 (2.12 μg/mL) or 1G5 (2 μg/mL) each fully rescued the suppression of mossy fiber LTP mediated by AD 1 or AD2 when simply added to the slice perfusate with these extracts (Fig. 1A, B; quantified in C). These results indicate that diffusible oAβ from AD brain impairs mf-LTP, and monoclonal antibodies specific for oAβ (they bind to monomers >100-fold less avidly (Liu et al., 2021) can protect against this.

Fig. 1.

oAβ from AD brain extracts impairs mossy fiber LTP and anti-Aβ antibodies protect against this. (A) Time course plots show that 71A1 prevented the blockade of mossy fiber LTP by AD extract 1 (AD 1. Each slice used for each treatment was from a different animal. Insets, Representative fEPSPs recorded before (grey) and after (blue, red and orange) HFS in aCSF, AD1 and AD1 + 71A1 slices, respectively. Calibration bars: horizontal, 10 ms; vertical, 0.2 mV. (B) 1G5 or 71A1 rescued the blockade of mf-LTP by AD extract 2 (AD 2). Each slice used for each treatment was from a different animal. Insets, Representative fEPSPs recorded before (grey) and after (blue, red, orange and pink) HFS in aCSF, AD2, AD2 + 1G5, and AD2 + 71A1 slices, respectively. Calibration: horizontal, 10 ms; vertical, 0.2 mV. (C) Histogram of the average potentiation for the last 10 min of LTP recording for experiments testing AD1 treatment +/− 2.12 μg/mL 71A1 and testing AD2 treatment +/− 2 μg/mL 1G5, 2.12 μg/mL 71A1. Error bars = mean +/− standard error. P-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test comparing the means of recorded fEPSP slopes. Compared to control, AD1 significantly blocked LTP (Ctr:157.6 ± 12.28 n = 6 vs. AD1: 120.4 ± 4.56 n = 4, p = 0.046). 71A1 prevented the blockade of LTP by AD1 (AD1:120.4 ± 4.6% n = 4 vs AD1 with 2.12 μg/mL 71A1: 158.7 ± 11.3% n = 6, p = 0.03). AD2 significantly blocked LTP compared to vehicle control (Ctr: 157.6 ± 12.28 n = 6 vs AD2: 118.6 ± 4.38 n = 4, p = 0.038). Two anti-Aβ antibodies, 1G5 and 71A1 prevented the blockade of LTP by AD2 respectively (AD2: 118.6 ± 4.4% n = 4 vs. AD2 with 2 μg/mL 1G5: 180.2 ± 5.5% n = 6, p < 0.0001; AD2: 118.6 ± 4.4% n = 4 vs. AD2 with 2.12 μg/mL 71A1: 157.6 ± 12.8% n = 4, p = 0.03). (D) Input-output curves of stimulus intensity versus fEPSP slope at the mossy fiber-CA3 synapses in AD treatment slices (blue circles, Ctr n = 10 slices from 7 mice; orange squares, AD n = 8 slices from 6 mice). Insets, Representative fEPSPs responses to 50, 100 and 300 μA stimulation in aCSF and AD slices respectively. Calibration: horizontal, 10 ms; vertical, 0.5 mV. (E) The ratio of the slope of the fEPSPs evoked by the second stimulus and that evoked by the first stimulus is plotted at various inter-pulse intervals (blue circles, Ctr n = 7 slices from 5 mice: orange squares, AD n = 8 slices from 6 mice). Traces show typical fEPSPs evoked with a 55 ms interpulse interval in aCSF and AD slices. Calibration bars: horizontal, 10 ms; vertical, 0.2 mV. * p < 0.05, **** p < 0.0001.

To assess whether oAβ alters basal synaptic transmission, we measured input/output curves over a broad range of stimulus intensities (25–1000 μA) against the resulting fEPSP slope and found no significant differences between aCSF and oAβ-rich AD soaking extracts (Fig. 1D). However, we did observe a significantly reduced paired-pulse ratio of fEPSP slope at 10–100 ms inter-pulse intervals in human oAβ-treated slices, compared with the typical paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) seen in control aCSF-treated slices (Fig. 1E). PPF is a measure of short-term plasticity and presynaptic efficacy. The changes in paired-pulse facilitation indicate presynaptic involvement in the effects of oAβ on mossy fiber LTP. This result suggests that oAβ impairs mf LTP in part through presynaptic mechanisms.

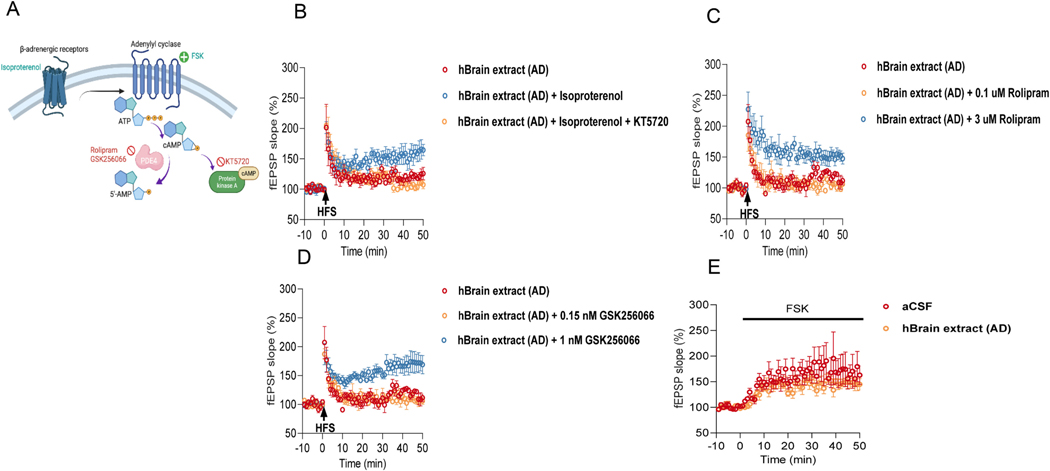

3.2. Prevention of oAβ-impaired mf-LTP by activating β-AR or their downstream cAMP/PKA signaling pathway

In vitro studies have shown that modulation of β-adrenergic receptors (AR) is a crucial upstream event for inducing mf-LTP. Activation of β-AR can induce mf-LTP, while antagonism of β-AR blocks it (Hopkins and Johnston, 1988; Huang and Kandel, 1996). β-Adrenergic responses are proposed to be mediated by activation of a cAMP cascade (Fig. 2A). To assess whether oAβ-mediated mf-LTP inhibition can be prevented by activation of β-AR and their downstream cAMP/PKA signaling, we treated hippocampal slices with AD soaking brain extracts mixed with a non-selective agonist of β-AR, isoproterenol (ISO, 1 μM) alone or with an inhibitor of PKA, KT5720 (1 μM). The results showed full recovery of mf- LTP by ISO, but the rescue did not occur in the presence of KT5720 (Fig. 2B). We next examined the effects of activating cAMP/PKA signaling with the phosphodiesterase type 4 (PDE4) inhibitors, Rolipram or GSK256066; the latter is a potent and tight-binding inhibitor of PDE4B with an apparent IC50 of 3.2 pM (Tralau-Stewart et al., 2011). Rolipram at 3 μM (but not at 0.1 μM) prevented the inhibition of mf-LTP by oAβ when added to the slice perfusate with the soluble AD brain extracts (Fig. 2C); 3 μM is known to increase cAMP concentration in hippocampal slices (Barad et al., 1998). Likewise, GSK256066 at 1 nM (but not at 150 pM) prevented mf-LTP inhibition by oAβ (Fig. 2D). Next, we investigated the effect of oAβ on activation of cAMP/PKA signaling by the adenylyl cyclase activator, Forskolin. Forskolin (FSK, 5 μM) induced potentiation by progressively increasing mf-fEPSP slope, and oAβ did not inhibit this forskolin-induced potentiation (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these results suggest that soluble oAβ from AD brain inhibit mossy fiber LTP, and this can be prevented by activation of β-AR and the downstream cAMP/PKA signaling pathway.

Fig. 2.

Prevention of oAβ-impaired mf LTP by β-AR activation and its downstream cAMP-PKA signaling pathway. (A) Schematic illustration of presynaptic cAMP-PKA signaling pathway that respond to activation of βAR and the effects of some agonists (light blue) and antagonists (red). (B) The β-AR agonist isoproterenol (ISO, 1 μM) prevented the inhibition of LTP by oAβ (AD: 121.1 ± 5.07% n = 4 vs. AD with 1 μM ISO: 158.3 ± 14.05% n = 4, p = 0.027), but the LTP was blocked by applying PKA inhibitor KT5720 (1 μM) (AD with 1 μM ISO: 158.3 ± 14.05% n = 4 vs. AD with 1 μM ISO + 1 μM KT5720: 106.4 ± 2.76% n = 5, p = 0.003; one way ANOVA test). Each slice used for each treatment was from a different animal. (C) The PDE 4 inhibitor Rolipram (3 μM but not 0.1 μM) prevented the inhibition of LTP by AD (AD: 118.6 ± 4.38% n = 4 vs AD with 3 μM Rolipram: 150.8 ± 8.56%, n = 4, p = 0.008; AD: 118.6 ± 4.38% n = 4 vs AD with 0.1 μM Rolipram: 104.5 ± 1.95%, n = 4, p = 0.237; One way ANOVA test). Each slice used for each treatment was from a different animal. (D) GSK256066 (1 nM but not 150 pM) prevented the inhibition of LTP by AD (AD: 118.6 ± 4.38% n = 4 vs. AD with 1 nM GSK256066: 171 ± 16.12%, n = 4, p = 0.018; AD: 118.6 ± 4.38% n = 4 vs. AD2 with 150 pM GSK256066: 108 ± 5.51%, n = 3, p = 0.792; One way ANOVA test). Each slice used for each treatment was from a different animal. (E) Time course of mf-fEPSP slope potentiation induced by perfusion of forskolin (FSK, 5 μM) in control condition and in presence of 5% AD (Ctr: 167.9 ± 24.7% n = 5 vs AD: 146.7 ± 9.44% n = 4, p = 0.489; unpaired Student’s t-test). * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

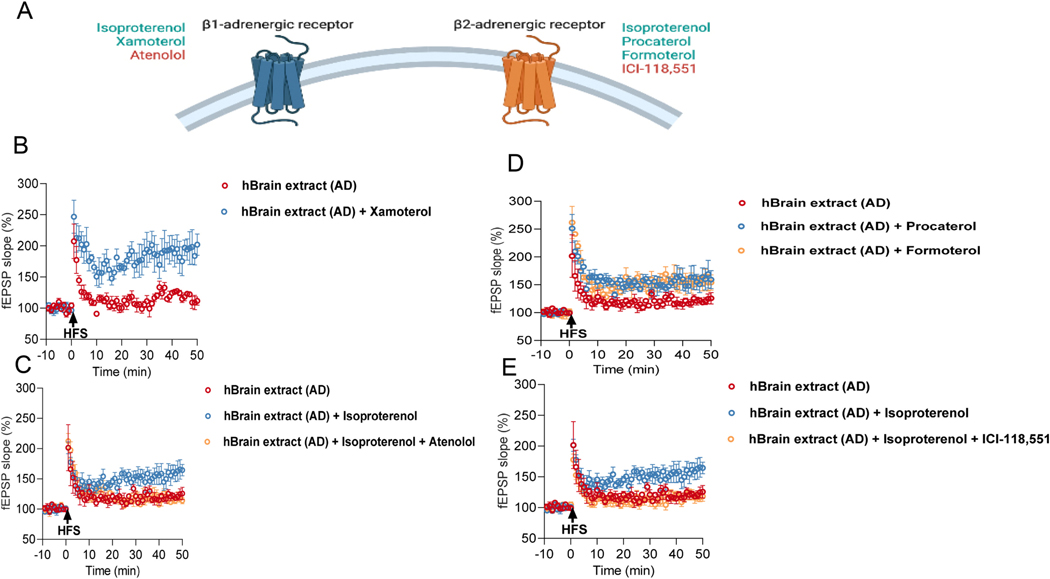

3.3. oAβ impairment of mf-LTP is prevented by activation of β1AR or β2AR

Previous studies reported that the subtypes of βAR, namely β1 and β2AR, are important for hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Yang et al., 2002; Gelinas et al., 2008; Hagena et al., 2016). To assess the contribution of the two β-AR subtypes to the impairment of mf-LTP by oAβ, we used different selective β1AR and β2AR agonists and antagonists (Fig. 3A). First, Xamoterol (1 μM), a selective β1-AR partial agonist, prevented the inhibition of mf-LTP when co-administered with AD soaking brain extracts (Fig. 3B). In accord, a selective β 1AR antagonist, atenolol (2 μM), blocked the rescue by ISO of mf-LTP (Fig. 3C). Similarly, the selective β2AR agonists Procaterol (0.1 μM) and Formaterol (0.1 μM) each rescued mf-LTP suppression by the AD brain extracts (Fig. 3D). A selective β2AR antagonist, ICI-118,551 (0.1 μM) blocked the ISO-rescued mf-LTP (Fig. 3E). These results suggest that the rescue of oAβ-impaired mf-LTP requires activation of both β1and β2AR.

Fig. 3. Prevention of oAβ-impaired mf LTP by activation of β1AR or β2AR.

(A) Summary of selective βAR or β2AR agonists (light blue) and antagonists (red). (B) Xamoterol, a selective β1AR partial agonist prevented the inhibition of LTP by AD. Each slice used for each treatment was from a different animal (AD: 118.6 ± 4.38% n = 4 vs. AD with 1 μM Xamoterol: 190.6 ± 20.63% n = 4, p = 0.014; unpaired student’s t-test). (C) Effect of atenolol, a selective β1AR antagonist on ISO-rescued MF-LTP. Each slice used for each treatment was from a different animal (AD: 121.1 ± 5.07% n = 4 vs. AD with 1 μM ISO: 158.3 ± 14.05% n = 4, p = 0.032; AD with 1 μM ISO: 158.3 ± 14.05% n = 4 vs. AD with 1 μM ISO and 2 μM atenolol: 117.3 ± 5.04% n = 6, p = 0.011; one way ANOVA). (D) Procaterol or Formaterol, selective β2AR agonists prevented the inhibition of LTP by AD respectively. Each slice used for each treatment was from a different animal (AD: 121.1 ± 5.07% n = 4 vs AD with 0.1 μM Procaterol: 158.1 ± 16.39% n = 5, p = 0.044; AD: 121.1 ± 5.07% n = 4 vs AD with 0.1 μM Formaterol: 155.9 ± 10.75% n = 3, p = 0.024; One way ANOVA test). (E) Effect of ICI-118,551, a selective β2AR antagonist on ISO-rescued MF-LTP (AD: 121.1 ± 5.07% n = 4 vs AD with 1 μM ISO: 158.3 ± 14.05% n = 4, p = 0.048; AD with 1 μM ISO: 158.3 ± 14.05% n = 4 vs AD with 1 μM ISO and 0.1 μM ICI-118,551: 117.5 ± 6.84% n = 5, p = 0.025; One way ANOVA test). Each slice used for each treatment was from a different animal. * p < 0.05.

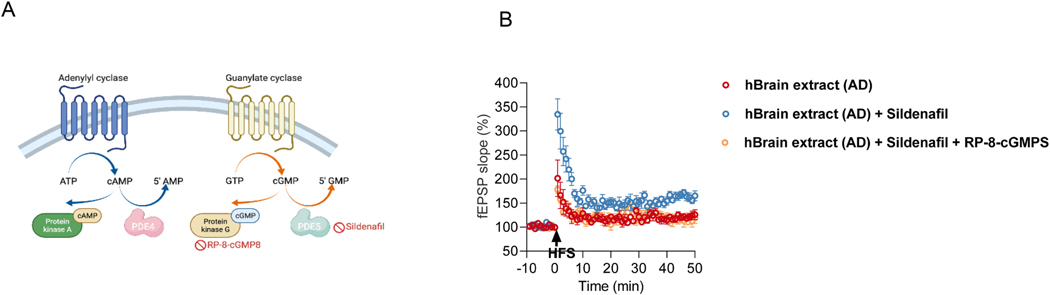

3.4. Prevention of oAβ-impaired mf-LTP by activation of cGMP-PKG signaling pathway

Synthetic Aβ peptides (in particular, aggregated Aβ1–42) have been reported to impair CA1 LTP in part via the cGMP/PKG/CREB signaling pathway (Puzzo et al., 2005). Our prior studies applying human brain oAβ-rich extracts indicate that their synaptotoxic and neuritotoxic potency is perhaps >100-fold more than that of synthetic Aβ aggregates (Jin et al., 2011) We therefore investigated a possible role for the cGMP-PKG pathway in protecting against natural oAβ-induced impairment of mf-LTP. We found that cGMP elevation through a 30 min application of sildenafil (50 nM), a specific PDE5 inhibitor (Fig. 4A) (Acquarone et al., 2019), prevented the inhibition of mf-LTP by oAβ. This effect of sildenafil was blocked by co-perfusion with the PKG inhibitor, Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (10 μM) (Fig. 4B). These results show that the prevention of oAβ-impaired mf-LTP by activation of the cGMP-PKG signaling pathway in parallel with the cAMP/PKA pathway.

Fig. 4.

Prevention of oAβ-impaired mf-LTP by activation of cGMP-PKG signaling pathway. (A) Schematic diagram of presynaptic the cAMP-PKA and cGMP-PKG signaling pathways and the effects of different antagonists. (B) sildenafil, a specific PDE5 inhibitor prevented the inhibition of LTP by AD but the rescued LTP was blocked by applying PKG inhibitors Rp-8-Br-cGMPS (10 μM) (AD: 120.4 ± 4.56% n = 4 vs AD with 50 nM sildenafil: 163.5 ± 5.29% n = 4, p = 0.02; AD with 50 nM sildenafil: 163.5 ± 5.29% n = 4 vs. AD with 50 nM sildenafil and 10 μM Rp-8-Br-cGMPS: 113.1 ± 8.76% n = 8, p = 0.0026; one way ANOVA test). * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

The major new findings in the present study are as follows. First, soluble Aβ oligomers (oAβ) isolated directly from AD brains impair presynaptic long-term plasticity at mf-CA3 synapses. Second, the strongly oligomer-preferring Aβ antibodies 71A1 and 1G5 protect against the oAβ-induced mf-LTP block. Third, activation of the β1AR or β2AR and their downstream cAMP/PKA signaling pathways can prevent oAβ-mediated inhibition of mf-LTP. Fourth, activation of the cGMP/PKG signaling pathway also can restore Aβ-impaired mf-LTP. Fifth, oAβ reduces PPF at 10–100 ms inter-pulse intervals in the mossy fiber pathway.

Synaptic dysfunction and/or loss have been hypothesized to be the principal basis for cognitive impairment in AD, in particular during the early stage of the disease (reviewed in Selkoe, 2002). The CA3 pyramidal cells (PC) receive mossy fiber inputs from DG granule cells. mf-CA3 synapses appear to be required for acquisition of contextual memories (Rolls, 2013; Shahola et al., 2022), and there is evidence for a role of mf-CA3 synapses in encoding new spatial information. Alterations in mf-CA3 synaptic function in the context of AD have only been studied in APP transgenic mice, including for example 12 mo transgenic AAP/PS1 mice and 24 mo Tg2576 mice (Maingret et al., 2017; Witton et al., 2010). Our study demonstrates for first time that presynaptic mf-LTP is specifically inhibited by AD brain-derived soluble Aβ oligomers in the hippocampus of WT mice. The source of Aβ peptides we used in this study is from highly disease-relevant human (AD) brain tissue. These soluble (‘soaking’) brain extracts contain heterogeneous Aβ monomers and dimers and higher oligomers (Hong et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Sebollela et al., 2017; Shankar et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2017). Analyses of such oAβ-rich extracts from human brain indicate that their synaptotoxic and neuritotoxic potency is perhaps ~100-fold greater than that of synthetic Aβ aggregates (Jin et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2017). We found the oAβ from diffusible AD brain extracts can significantly reduce paired-pulse facilitation (PPF). PPF is a measure of short-term plasticity and a change in PPF is frequently used as an indication of presynaptic involvement in long-term potentiation. So, our study suggests oAβ impairs mf LTP in part through presynaptic mechanisms.

In vitro studies have shown that β-adrenergic receptor activation and their downstream cAMP/PKA signaling modulates the early phase of mf- LTP via a presynaptic mechanism (Huang and Kandel, 1996). Our work shows that isoproterenol (ISO) can fully prevent oAβ-mediated inhibition of mf-LTP, but that rescue is blocked by the PKA inhibitor KT5720. We show that activation of β1AR or β2AR can prevent oAβ-mediated inhibition of mf-LTP by detailing the pharmacological the effects of β1AR or β2AR agonists and antagonists on this. These data provide strong evidence that these treatments prevent synaptic dysfunction induced by oAβ through activation of β1AR or β2AR and their downstream cAMP/PKA signaling pathway.

Another important finding of our study is that increases in intracellular cAMP or cGMP levels by inhibiting phosphodiesterases (PDEs) can restore oAβ-impaired mf-LTP. PDEs are grouped into 11 families based on homology of their catalytic domains, with most families containing more than one gene (Bender and Beavo, 2006). Some PDEs specifically hydrolyze cAMP (PDE4, PDE7 and PDE8) while others specifically hydrolyze cGMP (PDE5, PDE6 and PDE9) (Francis et al., 2011). We found that the PDE4 inhibitors, Rolipram or GSK256066 can prevent the inhibition of mf-LTP by oAβ when added to the slice perfusate together with the AD brain extracts. Furthermore, a surprising finding was that cGMP elevation through sildenafil (50 nM), a specific PDE5 inhibitor (Acquarone et al., 2019), prevented the mf-LTP inhibition by oAβ, and the effect of sildenafil was blocked by co-perfusion with the PKG inhibitor, Rp-8-Br-cGMPS. This finding is consistent with evidence that synthetic Aβ peptides (Aβ1–42) impair CA1 LTP in part via the NO/cGMP/PKG signaling pathway (Puzzo et al., 2005).

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that presynaptic mf-LTP is inhibited by applying AD brain-derived oAβ, and this can be prevented by certain oAβ antibodies, by β1AR or β2AR agonists and by PDE4 or PDE5 inhibitors. Together, these findings help identify a presynaptic form of LTP in which interrelated signaling pathways mediate the multifaceted synaptotoxicity of oAβ, suggesting several specific pharmacological targets to ameliorate oAβ-mediated impairment.

Funding

This work was funded by NIH grants R01AG006173 and P01AG015379 (DJS) and the Davis Amyloid Prevention Program (DJS).

Abbreviations:

- Aβ

amyloid β-protein

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- oAβ

oligomeric Aβ

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- mf

mossy fibers

- β-AR

β-adrenergic receptors

- ISO

isoproterenol

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- WT

wild-type

- PPF

paired-pulse facilitation

- PDE

phosphodiesterases

- FSK

forskolin

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

DJS is a director and consultant to Prothena Biosciences. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Acquarone E, Argyrousi EK, van den Berg M, Gulisano W, Fà M, Staniszewski A, Calcagno E, Zuccarello E, D’Adamio L, Deng SX, Puzzo D, Arancio O, Fiorito J, 2019. Synaptic and memory dysfunction induced by tau oligomers is rescued by up-regulation of the nitric oxide cascade. Mol. Neurodegener 14, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barad M, Bourtchouladze R, Winder DG, Golan H, Kandel E, 1998. Rolipram, a type IV-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor, facilitates the establishment of long-lasting long-term potentiation and improves memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 95, 15020–15025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender AT, Beavo JA, 2006. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol. Rev 58, 488–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SH, Blount MA, Corbin JD, 2011. Mammalian cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular mechanisms and physiological functions. Physiol. Rev 91, 651–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelinas JN, Tenorio G, Lemon N, Abel T, Nguyen P, 2008. Beta-adrenergic receptor activation during distinct patterns of stimulation critically modulates the PKA-dependence of LTP in the mouse hippocampus. Learn. Mem 15, 281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulisano W, Melone M, Li Puma DD, Tropea MR, Palmeri A, Arancio O, Grassi C, Conti F, Puzzo D, 2018. The effect of amyloid-beta peptide on synaptic plasticity and memory is influenced by different isoforms, concentrations, and aggregation status. Neurobiol. Aging 71, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagena H, Hansen N, Manahan-Vaughan D, 2016. β-Adrenergic control of hippocampal function: subserving the choreography of synaptic information storage and memory. Cereb. Cortex 26, 1349–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henze D, Wittner L, Buzsáki G, 2002. Single granule cells reliably discharge targets in the hippocampal CA3 network in vivo. Nat. Neurosci 5, 790–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W, Wang Z, Liu W, O’malley TT, Jin M, Willem M, Haass C, Frosch MP, Walsh DM, 2018. Diffusible, highly bioactive oligomers represent a critical minority of soluble Aβ in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Acta Neuropathol. 136, 19–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins W, Johnston D, 1988. Noradrenergic enhancement of long-term potentiation of mossy fiber synapses in the hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol 59, 667–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Kandel ER, 1996. Modulation of both the early and the late phase of mossy fiber LTP by the activation of β-adrenergic receptors. Neuron 16, 611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M, Shepardson N, Yang T, Chen G, Walsh D, Selkoe DJ, 2011. Soluble amyloid beta-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108, 5819–5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, 2007. Behavioral functions of the CA3 subregion of the hippocampus. Learn. Mem 14, 771–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL, 1998. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 95, 6448–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Kesner RP, 2004. Differential contributions of dorsal hippocampal subregions to memory acquisition and retrieval in contextual fear-conditioning. Hippocampus 14, 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Jin M, Liu L, Dang Y, Ostaszewski BL, Selkoe DJ, 2018. Decoding the synaptic dysfunction of bioactive human AD brain soluble Abeta to inspire novel therapeutic avenues for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta. Neuropathol. Commun 6, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Liu L, Selkoe DJ, 2019. Verubecestat for prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med 381, 388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Kwak H, Lawton TL, Jin SX, Meunier AL, Dang Y, Ostaszewski B, Pietras AC, Stern AM, Selkoe DJ, 2021. An ultra-sensitive immunoassay detects and quantifies soluble Aβ oligomers in human plasma. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, Beach T, Kurth JH, Rydel RE, Rogers J, 1999. Soluble amyloid beta peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol 155, 853–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maingret V, Barthet G, Deforges S, Jiang N, Mulle C, Amedee T, 2017. PGE2-EP3 signaling pathway impairs hippocampal presynaptic long-term plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 50, 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CA, Cherny RA, Fraser FW, Fuller SJ, Smith MJ, Beyreuther K, Bush AI, Masters CL, 1999. Soluble pool of Aβ amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol 46, 860–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashiba T, Young JZ, McHuagh TJ, Buhl DL, Tonegawa S, 2008. Transgenic inhibition of synaptic transmission reveals role of CA3 output in hippocampal learning. Science 319, 1260–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa K, Sun LD, Quirk MC, Rondi-Reig L, Wilson MA, Tonegawa S, 2003. Hippocampal CA3 NMDA receptors are crucial for memory acquisition of one-time experience. Neuron 38, 305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll RA, Schmitz D, 2005. Synaptic plasticity at hippocampal mossy fibre synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 6, 863–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzzo D, Vitolo O, Trinchese F, Jacob JP, Palmeri A, Arancio O, 2005. Amyloid-β peptide inhibits activation of the nitric oxide/cGMP/cAMPresponsive element-binding protein pathway during hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci 25, 6887–6897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls ET, 2013. A quantitative theory of the functions of the hippocampal CA3 network in memory. Front. Cell. Neurosci 7, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin PA, Scanziani M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, 1996. Distinct short-term plasticity at two excitatory synapses in the hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 93, 13304–13309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebollela A, Cline EN, Popova I, Luo K, Sun X, Ahn J, Barcelos MA, Bezerra VN, Lyra E, Silva NM, Patel J, Pinheiro NR, Qin LA, Kamel JM, Weng A, DiNunno N, Bebenek AM, Velasco PT, Viola KL, Lacor PN, Ferreira ST, Klein WL, 2017. A human scFv antibody that targets and neutralizes high molecular weight pathogenic amyloid-β oligomers. J. Neurochem 142, 934–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ, 2002. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science 298, 789–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahola M, Cohen R, Ben-Simon Y, Ashery U, 2022. cAMP-dependent synaptic plasticity at the hippocampal mossy fiber terminal. Front.Synaptic.Neurosci 14, 861215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, Brett FM, Farrell MA, Rowan MJ, Lemere CA, Regan CM, Walsh DM, Sabatini BL, Selkoe DJ, 2008. Soluble amyloid β-protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer disease patients potently impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med 14, 837–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tralau-Stewart CJ, Williamson RA, Nials AT, Gascoigne M, Dawson J, Hart GJ, Angell ADR, Solanke YE, Lucas FS, Wiseman J, Ward P, Ranshaw LE, Knowles RG, 2011. GSK256066, an exceptionally high-affinity and selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 suitable for administration by inhalation: in vitro, kinetic, and in vivo characterization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 337, 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitolo OV, Sant’Angelo A, Costanzo V, Battaglia F, Arancio O, Shelanski M, 2002. Amyloid beta-peptide inhibition of the PKA/CREB pathway and long-term potentiation: reversibility by drugs that enhance cAMP signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 99, 13217–13221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ, 2002. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 416, 535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HW, Pasternak JF, Kuo H, Ristic H, Lambert MP, Chromy B, Viola KL, Klein WL, Stine WB, Krafft GA, Trommer BL, 2002. Soluble oligomers of beta amyloid (1–42) inhibit long-term potentiation but not long-term depression in rat dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 924, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witton J, Brown JT, Jones MW, Randall AD, 2010. Altered synaptic plasticity in the mossy fibre pathway of transgenic mice expressing mutant amyloid precursor protein. Mol. Brain 3, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HW, Lin YW, Yen CD, Min MY, 2002. Change in bi-directional plasticity at CA1 synapses in hippocampal slices taken from 6-hydroxydopamine-treated rats: the role of endogenous norepinephrine. Eur. J. Neurosci 16, 1117–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Li S, Xu H, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ, 2017. Large soluble oligomers of amyloid beta-protein from Alzheimer brain are far less neuroactive than the smaller oligomers to which they dissociate. J. Neurosci 37, 152–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Mably AJ, Walsh DM, Rowan MJ, 2017. Peripheral interventions enhancing brain glutamate homeostasis relieve amyloid beta- and TNFalpha-mediated synaptic plasticity disruption in the rat hippocampus. Cereb. Cortex 27, 3724–3735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]