Abstract

Objectives:

Preterm birth has been linked with increased risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD); however, potential causality, sex-specific differences, and association with early term birth are unclear. We examined whether preterm and early term birth are associated with ASD in a large population-based cohort.

Methods:

A national cohort study was conducted of all 4,061,795 singletons born in Sweden during 1973–2013 who survived to age 1 year, who were followed up for ASD identified from nationwide outpatient and inpatient diagnoses through 2015. Poisson regression was used to determine prevalence ratios (PRs) for ASD associated with gestational age at birth, adjusting for confounders. Co-sibling analyses assessed the influence of unmeasured shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors.

Results:

ASD prevalences by gestational age at birth were 6.1% for extremely preterm (22–27 weeks), 2.6% for very to moderate preterm (28–33 weeks), 1.9% for late preterm (34–36 weeks), 2.1% for all preterm (<37 weeks), 1.6% for early term (37–38 weeks), and 1.4% for full-term (39–41 weeks). The adjusted PRs comparing extremely preterm, all preterm, or early term vs. full-term, respectively, were 3.72 (95% CI, 3.27–4.23), 1.35 (1.30–1.40), and 1.11 (1.08–1.13) among males, and 4.19 (3.45–5.09), 1.53 (1.45–1.62), and 1.16 (1.12–1.20) among females (P<0.001 for each). These associations were only slightly attenuated after controlling for shared familial factors.

Conclusions:

In this national cohort, preterm and early term birth were associated with increased risk of ASD in males and females. These associations were largely independent of covariates and shared familial factors, consistent with a potential causal relationship.

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong neurodevelopmental condition with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 1.0% to 1.5%.1, 2 Reported risk factors for ASD include male sex, advanced maternal or paternal age, and adverse perinatal exposures.3–5 A recent meta-analysis reported that children born preterm (gestational age <37 weeks) have an approximately 30% increased risk of ASD compared with those born full-term.5 Given the high prevalence of preterm birth (nearly 11% worldwide)6 and >95% survival with modern neonatal care,7, 8 even a modestly increased risk of ASD in preterm birth survivors may have important public health impacts.

Despite prior evidence linking preterm birth with ASD,5, 9–11 potential causality of this association, sex-specific differences, and the association with early term birth (37–38 weeks) have seldom been explored. It is unclear whether preterm birth causes ASD or if these conditions may have shared genetic or environmental determinants within families. In addition, ASD is 3 to 4 times more commonly diagnosed in boys than girls, but may be underdiagnosed in girls.3 Few studies have examined ASD risk specifically in preterm girls, possibly because of insufficient numbers of cases. Early term birth is ~3 times more common than preterm birth and has been associated with other chronic disorders,7, 12 yet has rarely been examined in relation to ASD. A Swedish cohort study of 3.3 million persons previously reported a 3-fold risk of ASD among those born extremely preterm (23–27 weeks) compared with 37–42 weeks, but did not examine sex-specific risks nor early term birth.9 Additional large cohort studies are needed for well-powered assessments of ASD risk in key subgroups. The results may improve risk stratification and help facilitate timely detection and treatment of ASD in susceptible subgroups.

We sought to address these knowledge gaps by conducting a national cohort study of over 4 million persons in Sweden. Our goals were to: (1) provide population-based estimates for ASD risk associated with gestational age at birth in the largest cohort to date; (2) assess for sex-specific differences; and (3) explore the influence of shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors using co-sibling analyses. We hypothesized that preterm and early term birth are associated with increased risk of ASD in males and females, and that these associations are only partially explained by shared familial factors.

METHODS

Study Population

The Swedish Medical Birth Register contains prenatal and birth information for nearly all births in Sweden since 1973.13 Using this register, we identified 4,070,204 singletons born during 1973–2013 who survived to age 1 year. Singleton births were chosen to improve internal comparability, given the higher prevalence of preterm birth and its different underlying causes among multiple births. Because ASD is usually diagnosed after 1 year of age, survival to this age was required to enable an assessment of ASD prevalence among individuals who survived long enough to be diagnosed. We excluded 8,409 (0.2%) births that had missing information for gestational age, leaving 4,061,795 births (99.8% of the original cohort) for inclusion in the study. This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden (No. 2020/627). Participant consent was not required as this study used only pseudonymized registry-based secondary data.

Gestational Age at Birth Ascertainment

Gestational age at birth was identified from the Swedish Birth Register based on maternal report of last menstrual period in the 1970s and ultrasound estimation starting in the 1980s and later (>70% of the cohort). This was examined alternatively as a continuous variable or categorical variable with 6 groups: extremely preterm (22–27 weeks), very to moderate preterm (28–33 weeks), late preterm (34–36 weeks), early term (37–38 weeks), full-term (39–41 weeks, used as the reference group), and post-term (≥42 weeks). In addition, the first 3 groups were combined to provide summary estimates for preterm birth (<37 weeks).

ASD Ascertainment

The study cohort was followed up for the earliest registered diagnosis of ASD from birth through December 31, 2015 (maximum age 43.0 years; median 21.5). International Classification of Diseases (ICD) version 9, introduced in 1987, was the earliest ICD version to include a code for ASD. In the present study, ASD was identified based on at least one diagnosis in the Swedish Hospital or Outpatient Registers (which include all primary and secondary diagnoses) or Primary Care Register (which includes all primary diagnoses) using ICD-9 codes 299A, 299B, 299W, and 299X during 1987–1996 and ICD-10 codes F84.0, F84.1, F84.3, F84.5, F84.8, and F84.9 during 1997–2015. The Hospital Register started in 1964 and had >99% nationwide coverage by 1987 and onward.14 The Outpatient Register started in 2001 and contains all outpatient diagnoses from all specialty clinics nationwide. The Primary Care Register initially included two populous counties covering 20% of the national population starting in 1998, then was expanded to cover approximately 90% of the national population by 2008 and onward.15 A prior validation of ASD diagnoses in Sweden reported a positive predictive value of 96%.16 A sensitivity analysis was performed that examined ASD based on ≥2 (rather than ≥1) registered diagnoses, using the same diagnostic codes as above.

Covariates

Other perinatal and sociodemographic characteristics that may be associated with gestational age at birth and ASD were identified using the Swedish Birth, Outpatient, and Hospital Registers and national census data, which were linked using a pseudonymized version of the personal identification number. Covariates included birth year (modeled simultaneously as a continuous variable and categorical variable by decade), sex, birth order (1, 2, ≥3), maternal and paternal age at birth of the offspring (5-year intervals), highest maternal and paternal education level achieved (≤9, 10–12, >12 years), maternal body mass index (BMI) at the beginning of prenatal care (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, ≥30 kg/m2), preeclampsia (ICD-8: 637; ICD-9: 624.4–624.7; ICD-10: O14-O15), other hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (ICD-8: 400–404; ICD-9: 401–405, 642.0–642.3, 642.9; ICD-10: I10-I15, O10-O11, O13, O15-O16), maternal diabetes mellitus (i.e., gestational or pregestational types 1 or 2; ICD-8: 250; ICD-9: 250, 648.0, 648.8; ICD-10: E10-E14, O24), and family history of ASD in a first-degree relative (i.e., parents or siblings, identified using the Total Population Register and ASD diagnoses based on inpatient and outpatient ICD codes as above). Maternal BMI, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, and diabetes were included because they have been associated with preterm birth17 and are reported risk factors for ASD in the offspring.18 All variables were >98% complete, except for maternal BMI which was recorded starting in 1982 (60.1% of the cohort). Missing data were modeled as a separate category. In addition, a sensitivity analysis was performed after restricting to all individuals with complete data (N=2,409,928).

Statistical Analysis

Poisson regression with robust standard errors was used to compute prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between gestational age at birth and ASD, relative to full-term birth. Analyses were conducted both unadjusted and adjusted for covariates (as above). Prevalence differences (PDs) and 95% CIs, attributable fraction in the exposed (AFe), and population attributable fraction (PAF) also were computed for each gestational age group compared with full-term. Sex-specific differences were assessed by performing sex-stratified analyses and formally testing for interaction between gestational age at birth and sex on the additive and multiplicative scale. Poisson model goodness-of-fit was assessed using deviance and Pearson chi-squared tests, which showed a good fit in all models.

Co-sibling analyses were performed to assess the potential influence of unmeasured shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors on the observed associations.7 A total of 3,151,723 individuals had at least one full sibling and were included in these analyses. Poisson regression fixed effects models were performed at the maternal and paternal level to account for all factors shared by full siblings, including genetic and early-life environmental factors, thus controlling for their shared exposures even if not specifically measured. In addition, these analyses were adjusted for the same covariates as in the primary analyses.

In secondary analyses, we also explored (1) associations between gestational age at birth and ASD either with or without intellectual disability (ICD-8: 310–315; ICD-9: 317–319; ICD-10: F70-F79); (2) spontaneous vs. medically indicated preterm birth in relation to ASD, relative to full-term birth; (3) interactions between gestational age at birth and fetal growth (small for gestational age [SGA; <10th percentile for gestational age] vs. appropriate for gestational age [AGA; 10th-90th percentile]) on the additive and multiplicative scale; and (4) associations between gestational age at birth and ASD risk after stratifying by birth decade. All statistical tests were 2-sided and used an α-level of 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1.

RESULTS

Table 1 reports offspring and parental characteristics by gestational age at birth. Preterm infants were more likely than full-term infants to be male, first-born, or have a family history of ASD; their mothers and fathers were more likely to be at the extremes of age or have low education level; and their mothers were more likely to have high BMI, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, or diabetes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants by gestational age at birth (1973–2013), Sweden.a

| Extremely preterm (22–27 wks) N=5,064 (0.1%) |

Very to moderate preterm (28–33 wks) N=39,621 (1.0%) |

Late preterm (34–36 wks) N=150,452 (3.7%) |

Early term (37–38 wks) N=716,670 (17.6%) |

Full-term (39–41 wks) N=2,812,729 (69.3%) |

Post-term (≥42 wks) N=337,259 (8.3%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) a | n (%) a | n (%) a | n (%) a | n (%) a | n (%) a | |

| Offspring factors | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 2,651 (52.3) | 21,939 (55.4) | 81,836 (54.4) | 369,116 (51.5) | 1,428,560 (50.8) | 183,118 (54.3) |

| Female | 2,413 (47.7) | 17,682 (44.6) | 68,616 (45.6) | 347,554 (48.5) | 1,384,169 (49.2) | 154,141 (45.7) |

| Birth order | ||||||

| 1 | 2,631 (51.9) | 20,775 (52.4) | 75,478 (50.2) | 288,675 (40.3) | 1,182,812 (42.0) | 168,795 (50.0) |

| 2 | 1,365 (27.0) | 10,914 (27.6) | 44,497 (29.6) | 262,248 (36.6) | 1,057,214 (37.6) | 107,721 (31.9) |

| ≥3 | 1,068 (21.1) | 7,932 (20.0) | 30,477 (20.3) | 165,747 (23.1) | 572,703 (20.4) | 60,743 (18.0) |

| Family history of ASD a | 224 (4.4) | 1,533 (3.9) | 5,064 (3.4) | 22,950 (3.2) | 75,724 (2.7) | 8,566 (2.5) |

| Maternal factors | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <20 | 183 (3.6) | 1,737 (4.4) | 6,024 (4.0) | 20,762 (2.9) | 79,753 (2.8) | 12,366 (3.7) |

| 20–24 | 862 (17.0) | 7,971 (20.1) | 32,137 (21.4) | 136,153 (19.0) | 571,636 (20.3) | 75,406 (22.4) |

| 25–29 | 1,416 (28.0) | 12,037 (30.4) | 48,596 (32.3) | 233,917 (32.6) | 983,733 (35.0) | 117,384 (34.8) |

| 30–34 | 1,423 (28.1) | 10,498 (26.5) | 39,158 (26.0) | 202,734 (28.3) | 788,503 (28.0) | 89,150 (26.4) |

| 35–39 | 855 (16.9) | 5,530 (14.0) | 18,976 (12.6) | 96,547 (13.5) | 316,891 (11.3) | 35,315 (10.5) |

| ≥40 | 235 (4.6) | 1,399 (3.5) | 4,402 (2.9) | 22,195 (3.1) | 57,989 (2.1) | 5,774 (1.7) |

| Unknown | 90 (1.8) | 449 (1.1) | 1,159 (0.8) | 4,362 (0.6) | 14,224 (0.5) | 1,864 (0.5) |

| Education (years) | ||||||

| ≤9 | 780 (15.4) | 6,336 (16.0) | 23,053 (15.3) | 99,907 (13.9) | 355,189 (12.6) | 47,113 (14.0) |

| 10–12 | 2,311 (45.6) | 18,783 (47.4) | 70,949 (47.2) | 327,587 (45.7) | 1,266,820 (45.0) | 152,836 (45.3) |

| >12 | 1,879 (37.1) | 14,012 (35.4) | 55,134 (36.6) | 284,158 (39.7) | 1,173,488 (41.7) | 134,953 (40.0) |

| Unknown | 94 (1.9) | 490 (1.2) | 1,316 (0.9) | 5,018 (0.7) | 17,232 (0.6) | 2,357 (0.7) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 105 (2.1) | 1,022 (2.6) | 4,608 (3.1) | 21,140 (2.9) | 63,520 (2.3) | 4,507 (1.3) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 1,554 (30.7) | 13,367 (33.7) | 55,593 (37.0) | 295,859 (41.3) | 1,144,824 (40.7) | 108,613 (32.2) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 705 (13.9) | 4,840 (12.2) | 18,554 (12.3) | 94,487 (13.2) | 362,433 (12.9) | 42,411 (12.6) |

| ≥30.0 | 426 (8.4) | 2,522 (6.4) | 8,758 (5.8) | 40,717 (5.7) | 137,562 (4.9) | 18,536 (5.5) |

| Unknown | 2,274 (44.9) | 17,861 (45.1) | 62,939 (41.8) | 264,467 (36.9) | 1,104,390 (39.3) | 163,192 (48.4) |

| Preeclampsia | 697 (13.8) | 7,255 (18.3) | 15,363 (10.2) | 38,158 (5.3) | 93,068 (3.3) | 11,699 (3.5) |

| Other hypertensive disorders | 74 (1.5) | 704 (1.8) | 2,094 (1.4) | 8,405 (1.2) | 23,382 (0.8) | 2,224 (0.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 140 (2.8) | 1,517 (3.8) | 5,824 (3.9) | 18,228 (2.5) | 30,103 (1.1) | 2,218 (0.7) |

| Paternal factors | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <25 | 557 (11.0) | 5,122 (12.9) | 19,445 (12.9) | 76,374 (10.7) | 306,822 (10.9) | 42,663 (12.7) |

| 25–29 | 1,194 (23.6) | 10,558 (26.7) | 42,595 (28.3) | 194,476 (27.1) | 817,666 (29.1) | 102,908 (30.5) |

| 29–34 | 1,386 (27.4) | 11,153 (28.2) | 43,700 (29.0) | 220,468 (30.8) | 890,786 (31.7) | 102,285 (30.3) |

| 35–39 | 954 (18.8) | 7,063 (17.8) | 25,795 (17.2) | 134,185 (18.7) | 495,264 (17.6) | 54,262 (16.1) |

| 40–44 | 467 (9.2) | 3,109 (7.8) | 10,706 (7.1) | 54,765 (7.6) | 184,237 (6.5) | 20,574 (6.1) |

| ≥45 | 251 (5.0) | 1,560 (3.9) | 5,202 (3.5) | 25,138 (3.5) | 79,609 (2.8) | 9,164 (2.7) |

| Unknown | 255 (5.0) | 1,056 (2.7) | 3,009 (2.0) | 11,264 (1.6) | 38,345 (1.4) | 5,403 (1.6) |

| Education (years) | ||||||

| ≤9 | 890 (17.6) | 8,184 (20.7) | 30,823 (20.5) | 137,296 (19.2) | 524,110 (18.6) | 68,939 (20.4) |

| 10–12 | 2,409 (47.6) | 19,168 (48.4) | 72,970 (48.5) | 343,216 (47.9) | 1,330,868 (47.3) | 156,807 (46.5) |

| >12 | 1,507 (29.8) | 11,162 (28.2) | 43,524 (28.9) | 224,345 (31.3) | 916,900 (32.6) | 105,661 (31.3) |

| Unknown | 258 (5.1) | 1,107 (2.8) | 3,135 (2.1) | 11,813 (1.6) | 40,851 (1.5) | 5,852 (1.7) |

ASD diagnosis in a parent or sibling.

AGA = appropriate for gestational age, ASD = autism spectrum disorder, LGA = large for gestational age, SGA = small for gestational age

ASD was identified in 58,404 (1.4%) persons. The median age for the entire cohort at the end of follow-up was 21.5 years (mean 20.8 ± 13.1). The median age at the earliest registration of ASD was 14.9 years (mean 15.8 ± 8.6). ASD diagnostic codes were unavailable before 1987 and the earliest available outpatient data started in 1998. Consequently, age at diagnosis was not precisely known and does not necessarily correspond to age at earliest registration of ASD.

Gestational Age at Birth and Risk of ASD

Gestational age at birth was inversely associated with ASD risk in the entire cohort. ASD prevalences were 6.1% for extremely preterm, 2.6% for very to moderate preterm, 1.9% for late preterm, 2.1% for all preterm, and 1.6% for early term, compared with 1.4% for full-term birth (Table 2). Unadjusted PRs for ASD among those born extremely preterm, any preterm, or early term were 4.54 (95% CI, 4.08–5.06), 1.57 (1.52–1.62), and 1.19 (1.16–1.21), respectively, relative to full-term. After adjusting for covariates, most PRs were moderately reduced but all remained significantly elevated. Adjusted PRs associated with extremely preterm, all preterm, or early term birth were 3.87 (95% CI, 3.48–4.31), 1.40 (1.36–1.45), and 1.12 (1.10–1.14), respectively, compared with full-term (P<0.001 for each). Each additional week of gestation was associated with a 5% lower prevalence of ASD on average (adjusted PR per additional week, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.95–0.96; P<0.001).

Table 2.

Associations between gestational age at birth (1973–2013) and risk of ASD (1987–2015), Sweden.

| Cases | Prev.a | Unadjusted | Adjustedb |

Unadjusted | AFec | PAFd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | P | PD (95% CI) | (%) | (%) | |

| Total cohort | ||||||||

| Preterm (<37 wks) | 4,147 | 2.1 | 1.57 (1.52, 1.62) | 1.40 (1.36, 1.45) | <0.001 | 0.7 (0.7, 0.8) | 37.7 | 3.7 |

| Extremely preterm (22–27 wks) | 311 | 6.1 | 4.54 (4.08, 5.06) | 3.87 (3.48, 4.31) | <0.001 | 4.7 (4.1, 5.5) | 83.7 | 0.7 |

| Very to moderate preterm (28–33 wks) | 1,023 | 2.6 | 1.91 (1.80, 2.03) | 1.65 (1.55, 1.76) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.1, 1.4) | 50.2 | 1.3 |

| Late preterm (34–36 wks) | 2,813 | 1.9 | 1.38 (1.33, 1.44) | 1.25 (1.20, 1.30) | <0.001 | 0.5 (0.5, 0.6) | 28.1 | 1.9 |

| Early term (37–38 wks) | 11,451 | 1.6 | 1.19 (1.16, 1.21) | 1.12 (1.10, 1.14) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.2, 0.3) | 18.9 | 4.4 |

| Full-term (39–41 wks) | 37,940 | 1.4 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Post-term (≥42 wks) | 4,866 | 1.5 | 1.07 (1.04, 1.10) | 1.08 (1.05, 1.11) | <0.001 | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) | 4.0 | 0.5 |

| Per additional week (trend) | 0.94 (0.93, 0.94) | 0.95 (0.95, 0.96) | <0.001 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Males | ||||||||

| Preterm (<37 wks) | 2,829 | 2.7 | 1.48 (1.42, 1.54) | 1.35 (1.30, 1.40) | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.0) | 33.3 | 3.3 |

| Extremely preterm 22–27 wks) | 214 | 8.1 | 4.49 (3.94, 5.10) | 3.72 (3.27, 4.23) | <0.001 | 6.3 (5.2, 7.3) | 83.6 | 0.7 |

| Very to moderate preterm (28–33 wks) | 687 | 3.1 | 1.74 (1.61, 1.87) | 1.54 (1.43, 1.66) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) | 45.3 | 1.2 |

| Late preterm (34–36 wks) | 1,928 | 2.4 | 1.31 (1.25, 1.37) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.27) | <0.001 | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 23.5 | 1.6 |

| Early term (37–38 wks) | 7,683 | 2.1 | 1.16 (1.13, 1.19) | 1.11 (1.08, 1.13) | <0.001 | 0.3 (0.2, 0.3) | 16.1 | 3.7 |

| Full-term (39–41 wks) | 25,648 | 1.8 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Post-term (≥42 wks) | 3,397 | 1.9 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.06 (1.02, 1.09) | 0.002 | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) | 4.5 | 0.5 |

| Per additional week (trend) | 0.94 (0.94, 0.95) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.96) | <0.001 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Females | ||||||||

| Preterm (<37 wks) | 1,318 | 1.5 | 1.67 (1.58, 1.77) | 1.53 (1.45, 1.62) | <0.001 | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 41.7 | 4.0 |

| Extremely preterm (22–27 wks) | 97 | 4.0 | 4.52 (3.71, 5.49) | 4.19 (3.45, 5.09) | <0.001 | 3.1 (2.3, 3.9) | 83.4 | 0.7 |

| Very to moderate preterm (28–33 wks) | 336 | 1.9 | 2.14 (1.92, 2.38) | 1.92 (1.72, 2.14) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | 55.5 | 1.5 |

| Late preterm (34–36 wks) | 885 | 1.3 | 1.45 (1.35, 1.55) | 1.34 (1.25, 1.43) | <0.001 | 0.4 (0.3, 0.5) | 32.0 | 2.1 |

| Early term (37–38 wks) | 3,768 | 1.1 | 1.22 (1.18, 1.27) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.20) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.2, 0.2) | 22.4 | 5.3 |

| Full-term (39–41 wks) | 12,292 | 0.9 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Post-term (≥42 wks) | 1,469 | 1.0 | 1.07 (1.02, 1.13) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) | <0.001 | 0.1 (0.0, 0.1) | 7.0 | 0.8 |

| Per additional week (trend) | 0.93 (0.92, 0.93) | 0.94 (0.93, 0.95) | <0.001 | |||||

Cumulative prevalence.

Adjusted for birth year, sex, birth order, maternal factors (age, education, BMI, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, diabetes), paternal factors (age, education), and family history of ASD.

Attributable fraction among the exposed.

Population attributable fraction.

PD = prevalence difference, PR = prevalence ratio

An estimated 83.7%, 37.7%, and 18.9% of ASD cases among individuals born extremely preterm, any preterm, or early term, respectively, were attributable to extremely preterm, any preterm, or early term birth (Table 2, attributable fraction in the exposed [AFe]). In the entire population, an estimated 0.7%, 3.7%, and 4.4% of ASD cases were attributable to extremely preterm, any preterm, or early term birth, respectively (Table 2, population attributable fraction [PAF]).

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; ICD-9 340.9, ICD-10 F90) was identified as a comorbidity in 23,447 (40.7%) persons diagnosed with ASD. Its prevalence by gestational age at birth in the entire cohort was 8.4% for extremely preterm, 4.7% for moderate to very preterm, 3.6% for late preterm, 4.0% for all preterm, and 3.2% for early term, compared with 2.8% for full-term.

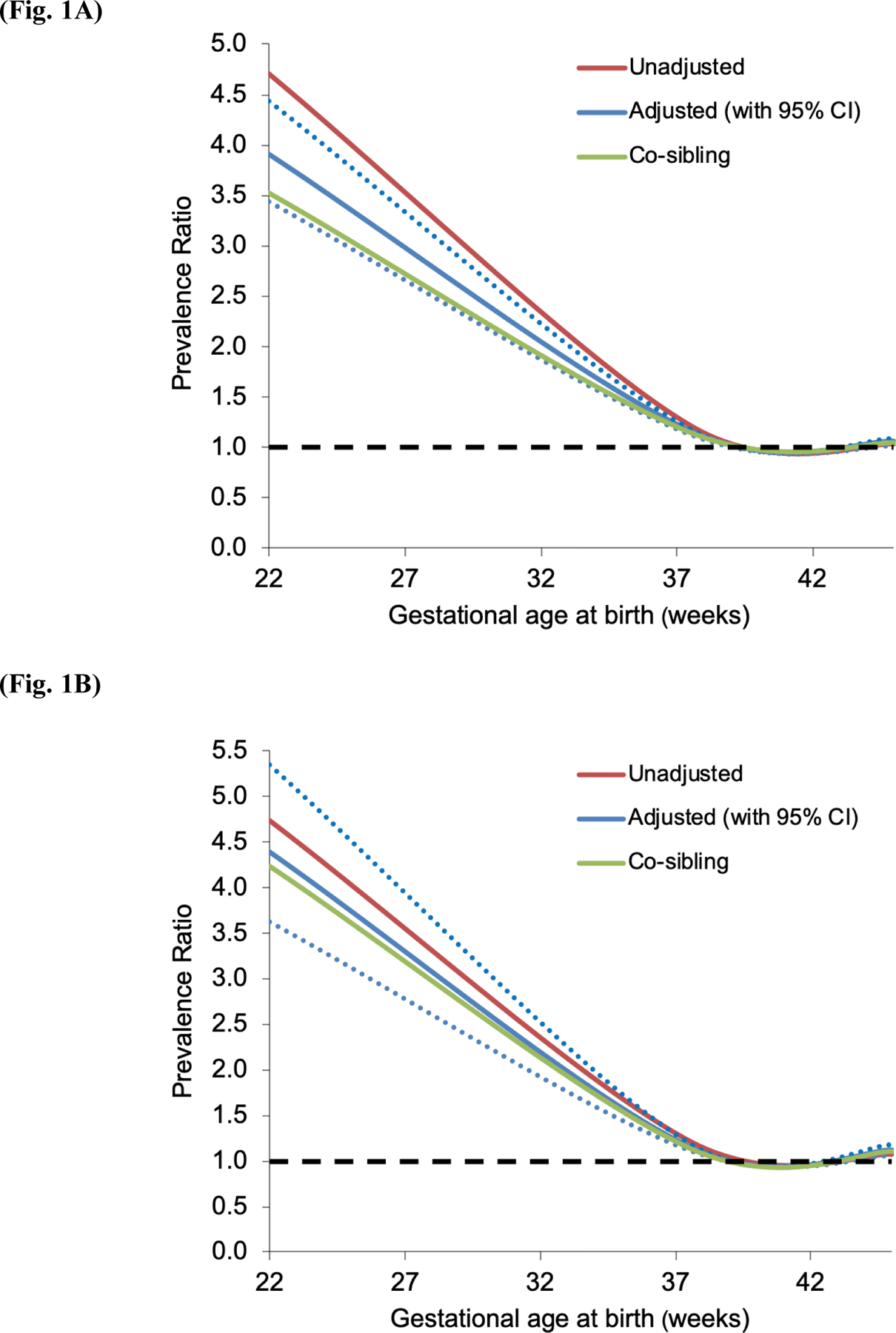

Sex-Specific Analyses

Preterm and early term birth were associated with increased risk of ASD among males and females (Table 2). In males, the adjusted PRs for ASD associated with extremely preterm, all preterm, and early term birth were 3.72 (95% CI, 3.27–4.23), 1.35 (1.30–1.40), and 1.11 (1.08–1.13), and in females were 4.19 (3.45–5.09), 1.53 (1.45–1.62), and 1.16 (1.12–1.20), respectively, compared with full-term (P<0.001 for each comparison). Figures 1A and 1B show PRs for ASD by gestational age at birth for males and females, respectively.

Figure 1.

Prevalence ratios for ASD (1987–2015) by gestational age at birth compared with full-term birth (1973–2013) in males (Fig. 1A) and females (Fig. 1B), Sweden (dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals for adjusted analyses).

Interactions between gestational age at birth and sex are shown in Table 3. Regardless of gestational age, ASD diagnosis was substantially more common in males than females. Preterm birth and male sex had a positive additive interaction (P=0.004) but negative multiplicative interaction (P<0.001) (i.e., the combined effect of preterm birth and male sex on ASD risk exceeded the sum but was less than the product of their separate effects). The positive additive interaction indicates that preterm birth accounted for more ASD cases among males than females.

Table 3.

Interactions between gestational age at birth and sex (1973–2013) in relation to risk of ASD (1987–2015).

| Gestational age at birth | PRs (95% CI) for early term vs. full-term within sex strata | PRs (95% CI) for preterm vs. full- term within sex strata | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-term (39–41 wks) | Early term (37–38 wks) | Preterm (<37 wks) | ||||||

| Prev.a (Cases) |

PR (95% CI)b | Prev.a (Cases) |

PR (95% CI)b | Prev.a (Cases) |

PR (95% CI)b | |||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 0.9% (12,292) | Reference | 1.1% (3,768) | 1.15 (1.11, 1.19); P<0.001 | 1.5% (1,318) | 1.52 (1.44, 1.61); P<0.001 | 1.15 (1.11, 1.19); P<0.001 | 1.52 (1.44, 1.61); P<0.001 |

| Male | 1.8% (25,648) | 2.02 (1.98, 2.07); P<0.001 | 2.1% (7,683) | 2.24 (2.18, 2.30); P<0.001 | 2.7% (2,829) | 2.74 (2.63, 2.85); P<0.001 | 1.11 (1.08, 1.13); P<0.001 | 1.35 (1.30, 1.40); P<0.001 |

| PRs (95% CI) for female vs. male within gestational age strata | 2.02 (1.98, 2.07); P<0.001 | 1.95 (1.87, 2.02); P<0.001 | 1.80 (1.68, 1.91); P<0.001 | |||||

| Interaction on additive scale: RERI (95% CI) | 0.07 (0.00, 0.14); P=0.05 | 0.19 (0.06, 0.32); P=0.004 | ||||||

| Interaction on multiplicative scale: PR ratio (95% CI) | 0.96 (0.92, 1.01); P=0.09 | 0.89 (0.83, 0.95); P<0.001 | ||||||

Cumulative prevalence.

Adjusted for birth year, sex, birth order, maternal factors (age, education, BMI, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, diabetes), paternal factors (age, education), and family history of ASD.

PR = prevalence ratio, RERI = relative excess risk due to interaction

Co-Sibling Analyses

Compared with the primary analyses, co-sibling analyses to control for unmeasured shared familial factors resulted in only modest attenuation of risk estimates (Table 4). For example, comparing preterm with full-term births, the adjusted PRs for ASD in the entire cohort were 1.40 (95% CI, 1.36–1.45; P<0.001) in the primary analysis vs. 1.32 (1.29–1.36; P<0.001) in the co-sibling analysis, among males were 1.35 (1.30–1.40; P<0.001) vs. 1.31 (1.26–1.35; P<0.001), and among females were 1.53 (1.45–1.62; P<0.001) vs. 1.51 (1.43–1.59; P<0.001).

Table 4.

Co-sibling analyses of gestational age at birth (1973–2013) and risk of ASD (1987–2015), Sweden.

| Cases | Prev.a | Adjustedb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | (%) | PR (95% CI) | P | |

| Total cohort | ||||

| Preterm (<37 wks) | 3,357 | 2.1 | 1.32 (1.29, 1.36) | <0.001 |

| Extremely preterm (22–27 wks) | 233 | 6.3 | 3.25 (2.92, 3.61) | <0.001 |

| Very to moderate preterm (28–33 wks) | 814 | 2.7 | 1.53 (1.45, 1.61) | <0.001 |

| Late preterm (34–36 wks) | 2,310 | 1.9 | 1.20 (1.16, 1.24) | <0.001 |

| Early term (37–38 wks) | 9,815 | 1.6 | 1.10 (1.08, 1.12) | <0.001 |

| Full-term (39–41 wks) | 32,942 | 1.4 | Reference | |

| Post-term (≥42 wks) | 4,070 | 1.5 | 1.07 (1.04, 1.09) | <0.001 |

| Per additional week | 0.96 (0.96, 0.96) | <0.001 | ||

|

| ||||

| Males | ||||

| Preterm (<37 wks) | 2,287 | 2.7 | 1.31 (1.26, 1.35) | <0.001 |

| Extremely preterm (22–27 wks) | 165 | 8.5 | 3.36 (2.96, 3.82) | <0.001 |

| Very to moderate preterm (28–33 wks) | 546 | 3.2 | 1.47 (1.37, 1.57) | <0.001 |

| Late preterm (34–36 wks) | 1,576 | 2.4 | 1.18 (1.14, 1.23) | <0.001 |

| Early term (37–38 wks) | 6,600 | 2.1 | 1.10 (1.07, 1.12) | <0.001 |

| Full-term (39–41 wks) | 22,202 | 1.8 | Reference | |

| Post-term (≥42 wks) | 2,843 | 1.9 | 1.05 (1.02, 1.08) | 0.003 |

| Per additional week | 0.96 (0.96, 0.97) | <0.001 | ||

|

| ||||

| Females | ||||

| Preterm (<37 wks) | 1,070 | 1.5 | 1.51 (1.43, 1.59) | <0.001 |

| Extremely preterm (22–27 wks) | 68 | 3.8 | 4.03 (3.32, 4.88) | <0.001 |

| Very to moderate preterm (28–33 wks) | 268 | 2.0 | 1.88 (1.69, 2.08) | <0.001 |

| Late preterm (34–36 wks) | 734 | 1.3 | 1.32 (1.24, 1.41) | <0.001 |

| Early term (37–38 wks) | 3,215 | 1.1 | 1.15 (1.11, 1.19) | <0.001 |

| Full-term (39–41 wks) | 10,740 | 0.9 | Reference | |

| Post-term (≥42 wks) | 1,227 | 1.0 | 1.11 (1.06, 1.17) | <0.001 |

| Per additional week | 0.94 (0.94, 0.95) | <0.001 | ||

Adjusted for shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors, and additionally for birth year, sex, birth order, maternal factors (age, education, BMI, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders, diabetes), paternal factors (age, education), and family history of ASD.

Secondary Analyses

Preterm and early term birth were associated with ASD either with or without intellectual disability (Supplemental Table 1). However, they were more strongly associated with ASD with intellectual disability (adjusted PR, preterm: 2.02; 95% CI, 1.89–2.17; P<0.001; early term: 1.25; 1.19–1.31; P<0.001) than without intellectual disability (preterm: 1.28; 1.23–1.32; P<0.001; early term: 1.10; 1.07–1.12; P<0.001).

We further examined ASD risk after stratifying by spontaneous (71.4%) or medically indicated (28.6%) preterm birth, which was systematically recorded starting in 1990 (N=2,415,158). Both spontaneous and medically indicated preterm birth were associated with an increased risk of ASD compared with full-term birth (adjusted PR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.28–1.41; P<0.001; and 1.52; 95% CI, 1.44–1.61; P<0.001, respectively), but medically indicated preterm birth was the stronger risk factor (P<0.001 for difference in PRs).

Both preterm birth and SGA were associated with increased risk of ASD after adjusting for each other as well as other covariates (PR, preterm vs. full-term: 1.40; 95% CI, 1.36–1.45; P<0.001; SGA vs. AGA: 1.29; 1.26–1.33; P<0.001), but preterm birth was the stronger risk factor (P<0.001 for difference in PRs). These factors had a significant positive interaction on the additive but not multiplicative scale (i.e., the combined effects of preterm birth and SGA on ASD risk exceeded the sum of their separate effects, P=0.001; Supplemental Table 2). The positive additive interaction indicates that preterm birth accounted for more ASD cases among individuals who were also SGA compared with those who were AGA.

The main analyses were repeated after stratifying by birth decade (1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s). Most results were similar across different birth cohorts (Supplemental Table 3). For example, comparing preterm vs. full-term birth, the adjusted PR by birth decade was 1.44 (95% CI, 1.27–1.63) for the 1970s, 1.37 (1.28–1.47) for the 1980s, 1.37 (1.30–1.44) for the 1990s, 1.41 (1.33–1.49) for the 2000s, and 1.55 (1.30–1.85) for the early 2010s (P<0.001 for each). Because ICD-9 was the first ICD version to include codes for ASD and was introduced in 1987, the similar findings for persons born in the 1970s (for whom ASD diagnoses would be recorded at later ages) suggest that the main results were not strongly influenced by the unavailability of ASD codes during the earliest years of follow-up. In addition, primary care and specialty outpatient diagnoses were unavailable prior to 1998 and 2001, respectively. The similar results among persons born in the 2000s-2010s compared with earlier decades suggest that the findings were not strongly influenced by the unavailability of outpatient data in earlier years.

In sensitivity analyses, the main analyses were repeated after (1) identifying ASD based on ≥2 (rather than ≥1) diagnoses, or (2) restricting to individuals with complete data (N=2,409,928). All risk estimates were nearly identical to the main findings and the conclusions were unchanged. For example, the adjusted PR for ASD comparing preterm with full-term birth was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.35–1.45; P<0.001) when identifying ASD based on ≥2 diagnoses and 1.40 (1.34–1.45; P<0.001) in a complete case analysis.

DISCUSSION

In this large national cohort, preterm and early term birth were associated with significantly increased risks of ASD in males and females. Persons born extremely preterm had an approximately 4-fold risk of ASD. These associations were largely independent of covariates as well as shared genetic or environmental determinants of preterm or early term birth and ASD within families, consistent with a potential causal relationship.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date of gestational age at birth in relation to ASD, and one of the first to investigate sex-specific differences, early term birth, or the influence of shared familial factors. A prior Swedish study of 3.3 million persons born in 1973–2008 who overlapped with the present cohort reported a 3-fold risk of ASD among those born extremely preterm (23–27 weeks) compared with 37–42 weeks (unadjusted hazard ratio [HR], 3.2; 95% CI, 2.6–4.0), but did not examine sex-specific risks nor early term birth.9 A US study of 195,021 births in 2000–2007 reported a 2.7-fold risk (95% CI, 1.5–5.0) of ASD among those born at 24–26 vs. 37–41 weeks.10 A US study of 7,876 births in 1994–2000 reported non-significant increased risks of ASD among those born extremely preterm (adjusted HR, 1.75; 95% CI, 0.41–7.40) or early term (1.16; 0.83–1.62) compared with 39–40 weeks, but was likely under-powered.11 A recent meta-analysis of 10 studies with a total of 6,485,081 participants reported a pooled relative risk of 1.31 (95% CI, 1.16–1.48; P<0.001) among those born preterm vs. full-term (variably defined).5

The present study extends this evidence by providing population-based risk estimates in a cohort of 4 million persons with >58,000 ASD cases, which enabled well-powered analyses of sex-specific differences, narrowly defined gestational age groups, and more complete adjustment for potential confounders. We found that preterm birth was associated with a higher relative risk of ASD in females (adjusted PR, 1.53) than males (1.35), likely due to a lower background prevalence of ASD diagnosis in females. However, preterm birth was associated with a larger number of ASD cases among males (additive interaction, P=0.004). Furthermore, early term birth (37–38 weeks) was associated with a modestly increased risk of ASD in females (adjusted PR, 1.16; P<0.001) and males (1.11; P<0.001). Early term birth has previously been associated with other chronic medical disorders19–24 and premature mortality from infancy into early adulthood,7, 12 supporting a re-definition of full-term birth.25 However, to our knowledge, the present study provides the first well-powered assessment of ASD risk associated with early term birth, which comprises 17–30% of all births.7, 8, 26 Consistent with a prior study,9 our findings appeared largely independent of shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors. Preterm and early term birth were associated with increased risk of ASD either without or (more strongly) with intellectual disability, which was overall consistent with a smaller overlapping cohort study from Stockholm.27 In addition, preterm birth was associated with increased risk of ASD across different birth decades from the 1970s through 2000s, consistent with a prior study in Denmark.28

Prior evidence has indicated that ASD is highly (~80%) but not entirely heritable.29 Preterm birth and other early-life environmental exposures may also be important contributors to ASD risk. The mechanisms are not established but may potentially involve inflammatory pathways.30–32 Increased proinflammatory cytokine levels, specifically IL-1, IL-6, and TNF, have been associated with uterine activation and the timing and initiation of preterm birth.33, 34 Up-regulation of proinflammatory cytokines in preterm infants has been reported to persist across the developmental trajectory in childhood.32, 35 Elevated inflammatory marker levels also have been detected in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of individuals with ASD and may play a key role in its pathogenesis.36, 37 Inflammatory-driven activation of microglia and synaptogenesis may lead to alteration or loss of neuronal connections during critical periods of brain development,36–38 which may be central to the development of ASD as well as other neurodevelopmental disorders.31 Intensive research into these mechanisms is ongoing and may potentially reveal new targets for intervention at critical windows of neurodevelopment to improve the disease trajectory.

The present study’s findings suggest that preterm and also early term birth should be recognized as independent risk factors for ASD. ASD may be significantly underdiagnosed in adult populations.39 In the present cohort, the median age at ASD diagnosis was 15 years, partly due to the unavailability of ASD codes before 1987, so that persons born in earlier years were often diagnosed in adolescence or adulthood. Our findings provide further evidence that gestational age at birth should be routinely included in history-taking and medical records for patients of all ages to help identify in clinical practice those born preterm or early term.40 Such information can provide additional valuable context for understanding patients’ health and may facilitate earlier evaluation for ASD and other neurodevelopmental conditions in those born prematurely.

A key strength of the present study was its large national cohort design, which afforded the high statistical power needed to examine ASD risk in narrowly defined gestational age groups and other relevant subgroups. Highly complete nationwide birth and medical registry data helped minimize potential selection or ascertainment biases. The availability of outpatient as well as inpatient diagnoses enabled more complete ascertainment of ASD rather than only the most severe cases, which may improve generalizability of the findings. Sweden’s national health system also facilitates more complete capture of diagnoses for the entire population by removing barriers to health care access. The overall prevalence of ASD in this cohort (1.4%) was commensurate with those based on clinical assessments in other populations.2 We were able to control for multiple potential confounders and assess the influence of unmeasured shared familial factors using co-sibling analyses.

This study also had several limitations. Detailed clinical records needed to validate ASD diagnoses were unavailable. However, ASD and other neuropsychiatric diagnoses in the Swedish registries have been validated previously and found to be highly reliable.14, 16 Outpatient diagnoses were available starting in 2001, resulting in under-reporting during earlier years. However, a sensitivity analysis suggested that this was unlikely to have a major influence on the findings. It is possible that ASD is more likely to be diagnosed in preterm children because of greater contact with the health care system (i.e., detection bias). However, this may be less likely among those born late preterm or early term, in whom increased risks also were found.

CONCLUSION

In this large population-based cohort, preterm and early term birth were associated with significantly increased risks of ASD in males and females. These findings were largely independent of measured covariates and unmeasured shared familial factors, consistent with a potential causal relationship. Persons born prematurely need early evaluation and long-term follow-up to facilitate timely detection and treatment of ASD, especially those born at the earliest gestational ages.

Supplementary Material

Article Summary:

This study determines associations between preterm or early term birth and autism risk, sex-specific differences, and potential causality in a cohort of >4 million persons.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Preterm birth has been linked with increased risk of autism; however, potential causality, sex-specific differences, and the association with early term birth are unclear. Such knowledge is needed to improve risk stratification and timely detection and treatment in susceptible subgroups.

What This Study Adds:

In a cohort of >4 million persons, preterm and early term birth were associated with significantly increased risks of autism in males and females. These associations were independent of covariates and shared genetic or environmental factors, consistent with potential causality.

Funding/Support:

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute at the National Institutes of Health [R01 HL139536 to C.C. and K.S.]; the Swedish Research Council; the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation; and ALF project grant, Region Skåne/Lund University, Sweden.

Role of Funder/Sponsor:

The funder/sponsor did not participate in the work.

Abbreviations:

- AFe

attributable fraction in the exposed

- AGA

appropriate for gestational age

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

- BMI

body mass index

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- LGA

large for gestational age

- PAF

population attributable fraction

- PD

prevalence difference

- PR

prevalence ratio

- SGA

small for gestational age

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Contributor Information

Casey Crump, Departments of Family Medicine and Community Health and of Population Health Science and Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.

Jan Sundquist, Center for Primary Health Care Research, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden.

Kristina Sundquist, Center for Primary Health Care Research, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018;392(10146):508–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elsabbagh M, Divan G, Koh YJ, Kim YS, Kauchali S, Marcin C, et al. Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Res 2012;5(3):160–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loomes R, Hull L, Mandy WPL. What Is the Male-to-Female Ratio in Autism Spectrum Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56(6):466–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolevzon A, Gross R, Reichenberg A. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism: a review and integration of findings. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161(4):326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C, Geng H, Liu W, Zhang G. Prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors associated with autism: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(18):e6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, Lumbiganon P, Petzold M, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7(1):e37–e46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crump C, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K. Gestational age at birth and mortality from infancy into mid-adulthood: a national cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019;3(6):408–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Prevalence of Survival Without Major Comorbidities Among Adults Born Prematurely. JAMA 2019;322(16):1580–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Onofrio BM, Class QA, Rickert ME, Larsson H, Langstrom N, Lichtenstein P. Preterm birth and mortality and morbidity: a population-based quasi-experimental study. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70(11):1231–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuzniewicz MW, Wi S, Qian Y, Walsh EM, Armstrong MA, Croen LA. Prevalence and neonatal factors associated with autism spectrum disorders in preterm infants. J Pediatr 2014;164(1):20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brumbaugh JE, Weaver AL, Myers SM, Voigt RG, Katusic SK. Gestational Age, Perinatal Characteristics, and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Birth Cohort Study. J Pediatr 2020;220:175–183 e178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Early-term birth (37–38 weeks) and mortality in young adulthood. Epidemiology 2013;24(2):270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweden Statistics. The Swedish Medical Birth Register https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/register-information/the-swedish-medical-birth-register/. Accessed June 4, 2020.

- 14.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundquist J, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, Kendler KS. Common adult psychiatric disorders in Swedish primary care where most mental health patients are treated. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17(1):235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idring S, Rai D, Dal H, Dalman C, Sturm H, Zander E, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in the Stockholm Youth Cohort: design, prevalence and validity. PLoS One 2012;7(7):e41280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371(9606):75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krakowiak P, Walker CK, Bremer AA, Baker AS, Ozonoff S, Hansen RL, et al. Maternal metabolic conditions and risk for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics 2012;129(5):e1121–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Risk of hypertension into adulthood in persons born prematurely: a national cohort study. Eur Heart J 2020;41(16):1542–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Preterm birth and risk of type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a national cohort study. Diabetologia 2020;63(3):508–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Association of preterm birth with lipid disorders in early adulthood: A Swedish cohort study. PLoS Med 2019;16(10):e1002947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crump C, Howell EA, Stroustrup A, McLaughlin MA, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Association of Preterm Birth With Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease in Adulthood. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173(8):736–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crump C, Sundquist J, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K. Preterm birth and risk of chronic kidney disease from childhood into mid-adulthood: national cohort study. BMJ 2019;365:l1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crump C, Friberg D, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Preterm birth and risk of sleep-disordered breathing from childhood into mid-adulthood. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48(6):2039–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spong CY. Defining “term” pregnancy: recommendations from the Defining “Term” Pregnancy Workgroup. JAMA 2013;309(23):2445–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ananth CV, Friedman AM, Gyamfi-Bannerman C. Epidemiology of moderate preterm, late preterm and early term delivery. Clin Perinatol 2013;40(4):601–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie S, Heuvelman H, Magnusson C, Rai D, Lyall K, Newschaffer CJ, et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorders with and without Intellectual Disability by Gestational Age at Birth in the Stockholm Youth Cohort: a Register Linkage Study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2017;31(6):586–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atladottir HO, Schendel DE, Henriksen TB, Hjort L, Parner ET. Gestational Age and Autism Spectrum Disorder: Trends in Risk Over Time. Autism Res 2016;9(2):224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bai D, Yip BHK, Windham GC, Sourander A, Francis R, Yoffe R, et al. Association of Genetic and Environmental Factors With Autism in a 5-Country Cohort. JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76(10):1035–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erdei C, Dammann O. The Perfect Storm: Preterm Birth, Neurodevelopmental Mechanisms, and Autism Causation. Perspect Biol Med 2014;57(4):470–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Favrais G, van de Looij Y, Fleiss B, Ramanantsoa N, Bonnin P, Stoltenburg-Didinger G, et al. Systemic inflammation disrupts the developmental program of white matter. Ann Neurol 2011;70(4):550–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malaeb S, Dammann O. Fetal inflammatory response and brain injury in the preterm newborn. J Child Neurol 2009;24(9):1119–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Challis JR, Lockwood CJ, Myatt L, Norman JE, Strauss JF, 3rd, Petraglia F. Inflammation and pregnancy. Reprod Sci 2009;16(2):206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cappelletti M, Della Bella S, Ferrazzi E, Mavilio D, Divanovic S. Inflammation and preterm birth. J Leukoc Biol 2016;99(1):67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin CY, Chang YC, Wang ST, Lee TY, Lin CF, Huang CC. Altered inflammatory responses in preterm children with cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol 2010;68(2):204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmerman AW, Jyonouchi H, Comi AM, Connors SL, Milstien S, Varsou A, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum markers of inflammation in autism. Pediatr Neurol 2005;33(3):195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez JI, Kern JK. Evidence of microglial activation in autism and its possible role in brain underconnectivity. Neuron Glia Biol 2011;7(2–4):205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chez MG, Dowling T, Patel PB, Khanna P, Kominsky M. Elevation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in cerebrospinal fluid of autistic children. Pediatr Neurol 2007;36(6):361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brugha TS, McManus S, Bankart J, Scott F, Purdon S, Smith J, et al. Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders in adults in the community in England. Archives of general psychiatry 2011;68(5):459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crump C Medical history taking in adults should include questions about preterm birth. BMJ 2014;349:g4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.