Abstract

Sexual disorders following retroperitoneal pelvic lymph node dissection (RPLND) for testis tumor can affect the quality of life of patients. The aim of the current study was to investigate several different andrological outcomes, which may be influenced by robot-assisted (RA) RPLND. From January 2012 to March 2020, 32 patients underwent RA-RPLND for stage I nonseminomatous testis cancer or postchemotherapy (PC) residual mass. Modified unilateral RPLND nerve-sparing template was always used. Major variables of interest were erectile dysfunction (ED), premature ejaculation (PE), dry ejaculation (DE), or orgasm alteration. Finally, fertility as well as the fecundation process (sexual intercourse or medically assisted procreation [MAP]) was investigated. Ten patients (31.3%) presented an andrological disorder of any type after RA-RPLND. Hypospermia was present in 4 (12.5%) patients, DE (International Index of Erectile Function-5 [IIEF-5] <25) in 3 (9.4%) patients, and ED in 3 (9.4%) patients. No PE or orgasmic alterations were described. Similar median age at surgery, body mass index (BMI), number of nodes removed, scholar status, and preoperative risk factor rates were identified between groups. Of all these 10 patients, 6 (60.0%) were treated at the beginning of our robotic experience (2012–2016). Of all 32 patients, 5 (15.6%) attempted to have a child after RA-RPLND. All of these 5 patients have successfully fathered children, but 2 (40.0%) required a MAP. In conclusion, a nonnegligible number of andrological complications occurred after RA-RPLND, mainly represented by ejaculation disorders, but ED occurrence and overall sexual satisfaction deficit should be definitely considered. No negative impact on fertility was described after RA-RPLND.

Keywords: andrology, lymph node excision, nonseminomatous germ cell tumor, robotics, testicular cancer

INTRODUCTION

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) represents the standard treatment in stage II (or higher) nonseminomatous germ cell tumor (NSGCT) patients harboring residual masses (>1 cm) after chemotherapy and an alternative to active surveillance or chemotherapy for stage I NSGCT patients.1 However, sexual disorders following RPLND can highly affect the quality of life of patients that usually are young at diagnosis,2 and have excellent tumor cure rates.3,4

In the last decades, a tremendous increase in robotic approach has been reported among all urological procedures, as well as for RPLND. Robot-assisted RPLND (RA-RPLND) was firstly described in 2006 by Davol et al.5 Later, RA-RPLND treatment has been reported in small series of stage I NSGCT patients and selected postchemotherapy residual masses.6,7,8,9 However, only a few studies reported about both sexual and reproductive outcomes following simple and postchemotherapy robot-assisted RPLNDs (RA-RPLND and PC-RA-RPLND).7,8,9 Most of these studies focused on ejaculatory disorders.

The current study aims at assessing both sexual and reproductive outcomes following nerve-sparing unilateral modified dissection template RA-RPLND, including erectile dysfunction (ED), antegrade ejaculation impairment, and fertility rate.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study population

Between January 2012 and March 2020, 32 patients diagnosed for NSGCT underwent a RA-RPLND or a PC-RA-RPLND for stage I NSGCT or postchemotherapy residual mass, respectively, at the European Institute of Oncology (Milan, Italy). All procedures were performed by two highly experienced surgeons (OdC and GM). In particular, each of them had previously performed at least one thousand robot-assisted urological surgeries and more than forty open RPLNDs. Major variable of interest was the occurrence of any andrological complications (ED, premature ejaculation [PE], dry ejaculation [DE], and orgasm alteration). In preoperative assessment, body mass index (BMI), scholar status (primary school, high school, and university), presence and type of preoperative sexual dysfunction (ED, PE, dimorphism, and orgasmic alteration), and general risk factors for sexual disorder (smoking status, alcohol intake, diabetes/metabolic syndrome, and neuroleptic/antiepileptic drugs) were investigated. The abridged 15-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-15) was administered pre- and postoperatively.10 The preorchiectomy and post-RA-RPLND sperm count analyses, if performed, were retrieved. All patients were asked to evaluate whether their postoperative experiences in sexual desire, orgasmic functioning, and sexual satisfaction were “better, same, or worse” with respect to before RA-RPLND. Finally, research and eventual obtainment of children was investigated, as well as the fecundation process (sexual intercourse or medically assisted procreation [MAP]).

All data were prospectively collected in a customized database and retrospectively analyzed. The Student’s t-test was used to compare the statistical significance of means’ differences, while the Chi-square test was used to compare the statistical significance of the differences in proportions. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level set at P < 0.05. Analyses were performed using the R software environment for statistical computing and graphics (version 3.4.1; http://www.r-project. org/).

Description of the technique

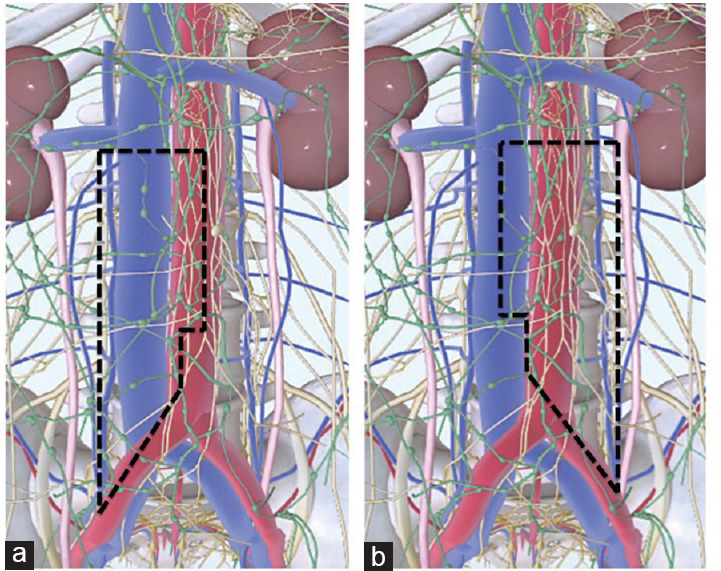

A modified unilateral lymph node dissection template was used for all patients according to those previously described for both simple11,12 and PC-RPLNDs.13 For both left- and right-sided RPLNDs, cranial and caudal boundaries were the renal veins and the ureteral crossing upon the iliac arteries, respectively. For right-sided tumors, paracaval, precaval, interaortocaval, preaortic, and right iliac nodes were retrieved. For left-sided tumors, para-aortic, preaortic, interaortocaval, and left iliac nodes were retrieved. Gonadal vessels as well as deferens duct were removed for both-sided RPLND. A nerve-sparing procedure was always attempted; postganglionic nerve fibers at aortic bifurcation and retrocaval sympathetic chain trunk were identified and spared. Finally, both-sided templates excluded the dissection of the contralateral tissue below a plane passing through the inferior mesenteric artery, thereby sparing the contralateral lower sympathetic nerves, superior hypogastric nerves, and hypogastric sympathetic plexus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection template limits. (a) Unilateral modified nerve-sparing template for right-sided primary testicular tumor. (b) Unilateral modified nerve-sparing template for left-sided primary testicular tumor.

RESULTS

In the current study, the overall population median (interquartile range) age was 29 (27–33) years, BMI was 24 (23–26) kg m−2, and most of the patients (27, 84.4%) had a high scholar status (Table 1). Of all RA-RPLNDs, 19 (59.4%) were performed because of a right-sided testis tumor, and 8 (25.0%) RA-RPLNDs were performed due to postchemotherapy residual masses. In four (12.5%) patients, a preoperative IIEF-5, derived from IIEF-15, lower than 25 was described. Within 25 (78.1% out of 32) patients where preoperative spermiogram’s result was available, in 22 (88.0% out of 25) semen count analysis was normal. Sperm was cryopreserved in 26 (81.3%) patients before primary orchiectomy. One (3.1%) patient underwent a testicular extraction of sperm (TESE) because of azoospermia. The last five (15.6%) patients were not interested in any kind of fertility preservation. Finally, 23 (71.9%) patients had at least one risk factor for sexual dysfunction occurrence. The median follow-up was 56.5 (49.7–69.0) months.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of 32 patients who underwent robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for nonseminomatous germ cell tumor

| Characteristic | Overall population |

|---|---|

| Age at surgery (year) | |

| Median | 29 |

| Range | 27–33 |

| BMI (kg m−2) | |

| Median | 24 |

| Range | 23–26 |

| Scholar status, n (%) | |

| University | 12 (37.5) |

| High school | 15 (46.9) |

| Primary school | 4 (12.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (3.1) |

| Preoperative IIEF-5 | |

| Median | 25 |

| Range | 19–25 |

| Preoperative RFs, n (%) | |

| No | 9 (28.1) |

| Yes | 23 (71.9) |

| Preoperative spermiogram, n (%) | |

| Altered | 3 (9.4) |

| Normal | 22 (68.8) |

| Unknown | 7 (21.9) |

| Preoperative sexual impairment, n (%) | |

| No | 28 (87.5) |

| Yes | 4 (12.5) |

| Year of surgery group, n (%) | |

| 2012–2016 | 17 (53.1) |

| 2017–2020 | 15 (46.9) |

| Type of RPLND, n (%) | |

| Postchemotherapy | 8 (25.0) |

| Simple | 24 (75.0) |

| Patients’ positioning, n (%) | |

| Full flank | 10 (31.3) |

| Supine | 22 (68.8) |

| Laterality, n (%) | |

| Left | 13 (40.6) |

| Right | 19 (59.4) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| No | 28 (87.5) |

| Yes | 4 (12.5) |

BMI: body mass index; IIEF-5: International Index of Erectile Function-5; RPLND: retroperitoneal lymph node dissection; RFs: risk factors

Of all 32 patients, 10 (31.3%) presented an andrological disorder of any type after RA-RPLND. Hypospermia was present in 4 (12.5%) patients, while DE in 3 (9.4%) patients and the last 3 (9.4%) patients experienced ED. No premature ejaculation or orgasmic alterations were described. Similar median age at surgery (29 years vs 30 years) and BMI (24 kg m−2 vs 24 kg m−2) were reported for both patients who experienced postoperative sexual dysfunctions and who did not (Table 2). In the group of patients who experienced postoperative sexual dysfunctions, one patient had a preoperative IIEF-5, derived from IIEF-15, lower than 25. All patients that experienced andrological complications after RA-RPLND had a high scholar status and six (60.0%) had at least one risk factor for sexual dysfunction. Conversely, no one had altered preoperative spermiogram. Most patients with sexual disorders after RA-RPLND (60.0%, 6 out of 10) were treated at the beginning of our robotic experience (2012–2016). All patients with andrological complications underwent a simple RA-RPLND, most (60.0%, 6 out of 10) for a left-sided primary tumor and in supine position (80.0%, 8 out of 10). Two (20.0%) out of 10 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. Finally, the median number of lymph node removed was similar for both patients who did and did not experience postoperative sexual dysfunctions (17 vs 16). Of all 32 patients, 5 attempted to have a child after RA-RPLND, and all of them successfully fathered children, but 2 (40.0%) of them required a MAP.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of 32 patients who underwent robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for nonseminomatous germ cell tumor, stratified according to experience or not a postoperative sexual impairment

| Characteristics | Postoperative sexual impairment: No (n=22; 68.8%) | Postoperative sexual impairment: Yes (n=10; 31.3%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (year) | |||

| Median | 30 | 29 | 0.2 |

| Range | 27–36 | 27–30 | |

| BMI (kg m−2) | |||

| Median | 24 | 24 | 0.4 |

| Range | 23–26 | 21–25 | |

| Number of LN removed | |||

| Median | 17 | 16 | 0.9 |

| Range | 11–21 | 12–19 | |

| Preoperative IIEF-5 | |||

| Median | 25 | 25 | 0.7 |

| Range | 20–25 | 19–25 | |

| Scholar status, n (%) | 0.4 | ||

| University | 7 (31.8) | 5 (50.0) | |

| High school | 10 (45.5) | 5 (50.0) | |

| Primary school | 4 (18.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Preoperative sexual impairment, n (%) | 1 | ||

| No | 19 (86.4) | 9 (90.0) | |

| Yes | 3 (13.6) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Preoperative RFs, n (%) | 0.6 | ||

| No | 5 (22.7) | 4 (40.0) | |

| Yes | 17 (77.3) | 6 (60.0) | |

| Preoperative RF categories, n (%) | 0.2 | ||

| None | 5 (22.7) | 4 (40.0) | |

| Diabetes/metabolic syndrome | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Neuroleptics/antiepileptic | 0 (0) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Smoke | 4 (18.2) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Alcohol | 10 (45.5) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Smoke and alcohol | 3 (13.6) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Preoperative spermiogram, n (%) | 0.2 | ||

| Altered | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Normal | 13 (59.1) | 9 (90.0) | |

| Unknown | 6 (27.3) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Type of RPLND, n (%) | 0.08 | ||

| Postchemotherapy | 8 (36.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Simple | 14 (63.6) | 10 (100) | |

| Year of surgery group | 0.9 | ||

| 2012–2016 | 11 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | |

| 2017–2020 | 11 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | |

| Patients’ positioning, n (%) | 0.7 | ||

| Full flank | 8 (36.4) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Supine | 14 (63.6) | 8 (80.0) | |

| Laterality, n (%) | 0.3 | ||

| Left | 7 (31.8) | 6 (60.0) | |

| Right | 15 (68.2) | 4 (40.0) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | 0.8 | ||

| No | 20 (90.9) | 8 (80.0) | |

| Yes | 2 (9.1) | 2 (20.0) |

BMI: body mass index; IIEF-5: International Index of Erectile Function-5; RPLND: retroperitoneal lymph node dissection; RFs: risk factors; LN: lymph node

DISCUSSION

Dry ejaculation is the typical andrological disorder that can occur after RPLND, but sexual satisfaction, erectile and orgasmic functioning, and fertility can be even severely impaired after this surgery. However, most of the studies published focused their investigation upon a single disorder, or to a limited group of them. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies reporting a complete overview of andrological aspects, which may be influenced by RA-RPLND.

The present study aimed to give a comprehensive description of possible sexual dysfunctions in 32 patients with NSGCT who underwent modified unilateral nerve-sparing simple and PC-RA-RPLNDs at our institution. Of all 32 patients, 10 (31.3%) presented an andrological disorder of any type after RA-RPLND. Hypospermia was present in 4 (12.5%) patients, while DE in 3 (9.4%) patients. Regarding DE, our results are similar to those of previous studies, where retrograde ejaculation was reported ranging between 2.0%–6.7% and 1.2%–6.1% in open and laparoscopic RPLNDs, respectively, and even higher rates were described in case of PC-RPLND for both approaches.14 Conversely, only a few series reported data regarding the DE occurrence after RA-RPLND, where it was described ranging between 0 and 10.5%.7,8,9 Finally, no accurate reports exist about the hypospermia prevalence in these patients. This information is difficult to be obtained, usually it is not reliable because based on patients’ accounts, and it is challenging to be tested on postoperative semen count analyses.

In a previous study, ED was shown as a transitory event that occurs in almost the 25% of patients.15 However, in a different series of full bilateral nonnerve-sparing PC-RPLND, no differences were described between pre- and postoperative erectile functions, while orgasmic functioning, intercourse, and overall sexual satisfactions were found significantly impaired after RPLND.16 In the current study, 3 (9.4%) patients experienced ED, while no PE or orgasmic alterations were described. Noteworthy, the two questions that affected the postoperative IIEF-15 final result were: the second “Over the last month, when you had erections with sexual stimulation, how often were your erections hard enough for penetration?” and the fifth “Over the last month, during sexual intercourse, how difficult was it to maintain your erection to completion of intercourse?”. Taking together, this observation underlines a greater psychological impact of neoplastic condition and surgical stress on erectile function than a biologic pathophysiological condition.

Because of the usual young age at diagnosis of patients with testicular cancer, fertility is often a primary concern. In a systematic review, a large proportion of patients with testis tumor were described to have an alteration of sperm count and motility before orchiectomy.17 This observation might be explained by the fact that testicular cancer itself can induce oligozoospermia due to dysgenesis, atrophy, and carcinoma in situ, or because it requires treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy that can impair the spermatic production.

This impairment was not so marked in our series. In the current study in fact, semen count analysis was normal in the 88.0% of the 25 patients whose preoperative spermiogram’s result was available. However, fertility conservation through sperm cryopreservation still remains an important aspect of preorchiectomy management. In our series, sperm cryopreservation before primary orchiectomy was reported in 26 (81.3%) patients and one (3.1%) patient underwent a TESE because of azoospermia. Moreover, of all 32 patients, 5 attempted pregnancy after RA-RPLND, and all of them successfully fathered children, but 2 (40.0%) of them required a MAP. These data are similar to those previously published.18,19

Finally, we used the number of LN removed as deputy of extent of RA-RPLND. Considering in fact the crucial help to spare ejaculatory disorders given by the extent of modified templates, we wanted to exclude a difference in extent of LN dissection between who experienced or not sexual dysfunctions. As aforementioned, all patients received the same unilateral modified nerve-sparing template according to the side of primary testis tumor. No differences were reported in terms of median LN removed that accounted for 17 and 16 in whom experienced or not sexual disorders, respectively.

Taking together, the current study results describe a considerable amount (31.3%) of sexual disorders after RA-RPLND. However, this observation is the result of the sum of all the considered dysfunctions, evidence that was not well assed in previous studies, and particularly in those regarding RA-RPLND. As expected, ejaculatory impairments represented the higher proportion, but ED occurrence and overall sexual satisfaction deficit should be definitely considered. In consequence, much effort is aimed in future studies for a more accurate investigation and a much more comprehensive analysis of all possible sexual impairments that can occur in these patients, avoiding to shed light only on the predominant ejaculatory disorders. This effort may help patient counseling and preoperative planning, particularly in this specific cohort of patients in which the postoperative quality of life may be a deterrent.

Despite its novelty and strength, the current study has some limitations. First, the major of them is the retrospective nature of the analyses conducted and a small population. This design type only allows testing the association between RA-RPLND and sexual disorders, but it does not allow inferring causality, while the population size does not allow any statistical predictive method. However, these are common pitfalls among the majority of studies dealing with this particular topic. Second, despite when possible we used health validated questionnaires (i.e., IIEF-15), some outcomes such as overall sexual satisfaction and desire to attempt pregnancy relied on patients’ accounts and for this can be affected by biases. Furthermore, despite their value, health validated questionnaires (i.e., IIEF-15) cannot entirely replace objective data obtained after specific clinical tests such as the RigiScan registration. In consequence, the current data on erectile function may be validated in future also after the RigiScan registration performed before and after the treatment for all patients. Finally, we could not provide a direct comparison between current results and data from our historic open series because these specific data were not historically prospectively collected. A retrospective and accurate collection and analysis would be strongly impaired by unknown biases.

CONCLUSIONS

In the current study, andrological results following RA-RPLND were demonstrated comparable with those of previous open and laparoscopic series regarding simple and PC-RPLNDs. Andrological complications are mainly represented by ejaculation disorders, but ED occurrence and overall sexual satisfaction deficit should be indeed considered. No negative impact on fertility was described after RA-RPLND in patients with NSGCT, but larger series with longer follow-up are needed to confirm our results.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

FAM and GM designed the study, wrote the manuscript, and interpreted data. OdC supervised the study and edited the manuscript. PV edited the manuscript and interpreted data. FB, LJ, and GC collected data. SL interpreted data. RB, EDT, MF, GC, and DB edited the manuscript. DVM and VM supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research received no external funding. We acknowledge the Italian Ministry of Health for the partial support with Ricerca Corrente and 5×1000 funds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bokemeyer C, Cohn-Cedermark G, et al. Guidelines on Testicular Cancer:2015 Update. Eur Urol. 2015;68:1054–68. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, et al. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2015. [Last accessed on 01 September 2021]. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2013. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/ Based on November 2015 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman MP, Quaresma M, Berrino F, Lutz JM, De Angelis R, et al. Cancer survival in five continents:a worldwide population-based study (CONCORD) Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:730–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fosså SD, Cvancarova M, Chen L, Allan AL, Oldenburg J, et al. Adverse prognostic factors for testicular cancer-specific survival:a population-based study of 27,948 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:963–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davol P, Sumfest J, Rukstalis D. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. Urology. 2006;67:199. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams SB, Lau CS, Josephson DY. Initial series of robot-assisted laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;60:1299–302. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheney SM, Andrews PE, Leibovich BC, Castle EP. Robot-assisted retroperitoneal lymph node dissection:technique and initial case series of 18 patients. BJU Int. 2015;115:114–20. doi: 10.1111/bju.12804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris KT, Gorin MA, Ball MW, Pierorazio PM, Allaf ME. A comparative analysis of robotic vs laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer. BJU Int. 2015;116:920–3. doi: 10.1111/bju.13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stepanian S, Patel M, Porter J. Robot-assisted laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer:evolution of the technique. Eur Urol. 2016;70:661–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Gendrano N. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF):a state-of-the-science review. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:226–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donohue JP, Thornhill JA, Foster RS, Rowland RG, Bihrle R. Retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for clinical stage A testis cancer (1965 to 1989): modifications of technique and impact on ejaculation. J Urol. 1993;149:237–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pizzocaro G, Salvioni R, Zanoni F. Unilateral lymphadenectomy in intraoperative stage I nonseminomatous germinal testis cancer. J Urol. 1985;134:485–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heidenreich A, Pfister D, Witthuhn R, Thüer D, Albers P. Postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in advanced testicular cancer:radical or modified template resection. Eur Urol. 2009;55:217–24. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crestani A, Esperto F, Rossanese M, Giannarini G, Nicolai N, et al. Andrological complications following retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testicular cancer. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2017;69:209–19. doi: 10.23736/S0393-2249.16.02789-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Capogrosso P, Boeri L, Ferrari M, Ventimiglia E, La Croce G, et al. Long-term recovery of normal sexual function in testicular cancer survivors. Asian J Androl. 2016;18:85–9. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.149180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimitropoulos K, Karatzas A, Papandreou C, Daliani D, Zachos I, et al. Sexual dysfunction in testicular cancer patients subjected to post-chemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection:a focus beyond ejaculation disorders. Andrologia. 2016;48:425–30. doi: 10.1111/and.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djaladat H, Burner E, Parikh PM, Beroukhim Kay D, Hays K. The association between testis cancer and semen abnormalities before orchiectomy:a systematic review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2014;3:153–9. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2014.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donohue JP, Foster RS, Rowland RG, Bihrle R, Jones J, et al. Nerve-sparing retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy with preservation of ejaculation. J Urol. 1990;144:287–91. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39434-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck SD, Bey AL, Bihrle R, Foster RS. Ejaculatory status and fertility rates after primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. J Urol. 2010;184:2078–80. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]