Abstract

Establishment and maintenance of chronic lung infections with mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) require that the bacteria avoid host defenses. Elaboration of the extracellular, O-acetylated mucoid exopolysaccharide, or alginate, is a major microbial factor in resistance to immune effectors. Here we show that O acetylation of alginate maximizes the resistance of mucoid P. aeruginosa to antibody-independent opsonic killing and is the molecular basis for the resistance of mucoid P. aeruginosa to normally nonopsonic but alginate-specific antibodies found in normal human sera and sera of infected CF patients. O acetylation of alginate appears to be critical for P. aeruginosa resistance to host immune effectors in CF patients.

The predominant bacterial pathogen in chronic pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients is the mucoid variant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is encapsulated by and overproduces mucoid exopolysaccharide (MEP), or alginate. That alginate is the major virulence factor of P. aeruginosa in CF lung infection is evident from the epidemiology of this disease. The pulmonary function of patients with CF declines only when mucoid P. aeruginosa is isolated and associated lung pathology develops (9, 32, 33). The growth of mucoid P. aeruginosa as a biofilm in the lungs of CF patients has been suggested to be a major factor in long-term bacterium survival. Biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa has been linked to genes involved in quorum sensing (7) and motility (31), with a recent demonstration that the acyl-homoserine lactone molecules involved in the quorum-sensing system (8) can be detected in the sputa of CF patients (42). However, the genes controlling alginate production appear to be independent of control by the known quorum-sensing genes of P. aeruginosa, including lasR and rhlR (8, 44, 45). Therefore, the question of whether there is a regulator or environmental cue common to both alginate production and quorum-sensing systems has not yet been answered.

The conversion of P. aeruginosa to the mucoid state in CF patients is often associated with mutations at the mucA locus (23). MucA and MucB (also called AlgN) act as anti-sigma factors for the alternative sigma factor ςE (47), encoded by algT (25), also known as algU (22). Increased activity of this sigma factor results in hyperexpression of the alginate biosynthetic operon located at 34 min on the P. aeruginosa genome (25). Conversion of P. aeruginosa to the mucoid state is often associated with the loss of production of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O side chains that normally render strains serum resistant (18, 30, 34).

MEP/alginate is a high-molecular-weight polysaccharide of β1–4-linked residues of mannuronic and guluronic acids (40, 41). The ratio of mannuronic acid to guluronic acid varies from strain to strain, on the order of 10:1 to 1:1 (40, 41). Acetylation occurs on the C-2 and C-3 hydroxyl groups of the mannuronic acid residues. The products of algI, algJ, and algF, located on the alginate biosynthetic operon, are required for the O acetylation of alginate (14, 15). Much research has been published on the biosynthesis of alginate (5, 6, 26, 46, 48) as well as on the control of synthesis by both genetic (2–4, 11, 13, 29) and environmental (10–12, 24, 25) factors. Despite this wealth of information, the exact molecular mechanisms by which alginate promotes the survival of bacteria in the lungs of otherwise immunocompetent hosts for years to decades have not been fully elucidated.

Defining the molecular properties of alginate that mediate the resistance of mucoid P. aeruginosa to host immune effectors is key to understanding the role of this material in pathogenesis. A property of MEP/alginate previously reported to be involved in the inability of CF patients to clear mucoid P. aeruginosa from their lungs is its elicitation during chronic infection of specific antibodies that fail to mediate the opsonic killing of mucoid P. aeruginosa growing either in suspension (32, 38) or in biofilms (27). Another characteristic of MEP/alginate that may confer bacterial resistance to host phagocytes and complement, particularly in the presence of the loss of production of the LPS O side chains that normally render strains serum resistant (18, 30, 34), is the presence of acetate substituents. Acetate residues are bound via ester linkages to hydroxyl groups that, when unsubstituted, can serve as acceptors for covalent linkage of the complement opsonins C3b and C4b to the bacterial surface (19). In addition, the presence of acetate residues may affect the activation of complement in an antibody-independent fashion. Thus, by linking acetate to hydroxyl groups, mucoid P. aeruginosa may be able to escape phagocytic killing by dampening the activation of complement. We therefore evaluated the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa FRD1153 (14, 15), an algJ mutant derived from mucoid P. aeruginosa strain FRD1, to opsonic killing by antibody-free human complement and by human complement with added MEP-specific opsonic and nonopsonic antibodies. These studies were performed to define further the role of acetate substituents in the long-term persistence of mucoid P. aeruginosa in the lungs of CF patients.

Comparative susceptibilities of strains to opsonic killing mediated by complement and leukocytes only.

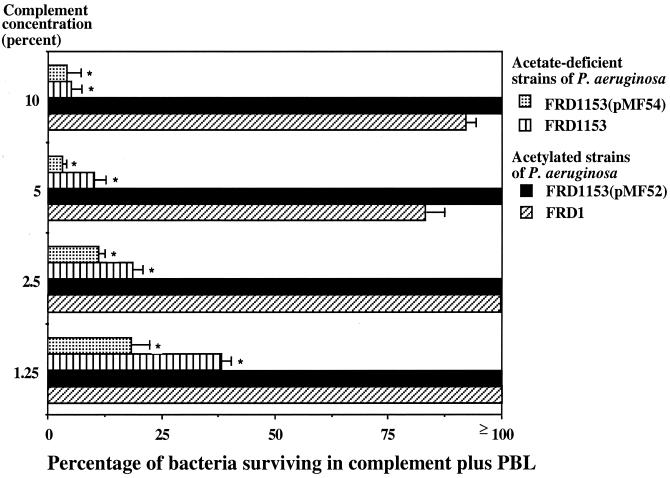

We initially assessed whether two components of the innate immune system—phagocytes and complement—could mediate the opsonic killing of parental, O-acetylation-deficient, and trans-complemented mucoid P. aeruginosa strains in the absence of antibody by using a well-established opsonophagocytic assay (1). The strains used were mucoid P. aeruginosa FRD1, a clinical isolate that has been extensively studied (2, 4, 5, 17, 29); mucoid P. aeruginosa FRD1153, which contains a point mutation generated in algJ as described previously (14, 15) and which produces only 7% of the parental level of O acetylation on alginate; strain FRD1153 complemented with plasmid pMF52 (15), which contains the algI, algJ, and algF genes under the control of the Ptrc promoter and which provides full restoration of parental levels of alginate acetylation in strain FRD1153; and strain FRD1153 complemented with plasmid pMF54, the vector control (15).

Strains with plasmid pMF52 or pMF54 were routinely cultured in Trypticase soy broth or on Trypticase soy agar plates containing 300 μg of carbenicillin/ml. Human serum was used as a source of complement; the serum was diluted 1:10 in RPMI medium–15% fetal calf serum and adsorbed twice with 1 to 2 mg of lyophilized P. aeruginosa strain FRD1 cells at 4°C for 30 min to remove specific antibody. Bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation, and the serum was filter sterilized and then diluted further for studies involving different concentrations of complement.

As shown in Fig. 1, 80 to 100% of cells of the parental strain, FRD1, and the fully complemented strain, FRD1153(pMF52), survived when up to 100 μl of a 10% concentration of adsorbed normal human serum was added to an opsonic killing assay with a final volume of 400 μl. Higher concentrations of human serum could not be used because mucoid strains from CF patients produce rough LPS (18), rendering the organisms sensitive to killing by complement alone at higher serum concentrations (35). In contrast, a maximum of 37% of cells of acetate-deficient strains FRD1153 and FRD1153(pMF54) survived when 100 μl of a 1.25% concentration of adsorbed normal human serum was added to the assay (Fig. 1). The survival of FRD1153 was reduced at higher concentrations of serum, with less than 10% survival at a 10% serum concentration.

FIG. 1.

Susceptibility of variously acetylated mucoid P. aeruginosa strains to opsonic killing by human peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) and complement at the indicated concentrations. Strain FRD1153 is an algJ mutant strain, unable to O acetylate alginate. Strain FRD1 is the parental strain of FRD1153. Plasmid pMF52 contains the algI, algJ, and algF genes under the control of the Ptrc promoter and restores the O-acetylation phenotype to FRD1153. Plasmid pMF54 is the cloning vector. Bars represent the mean CFU surviving, and error bars indicate the standard deviation. Asterisks indicate that at all complement concentrations tested, the percentage of bacteria surviving was significantly lower in both of the O-acetyl-deficient strains than in the O-acetyl-sufficient strains (P < 0.001, as determined by ANOVA and Fisher's PLSD test for pairwise comparisons).

Complementation in trans of FRD1153 with algJ from plasmid pMF52 restored the parental level of resistance to complement-mediated opsonic killing, whereas FRD1153 with the vector control, pMF54, was susceptible to complement-mediated opsonic killing. At all concentrations of human complement tested, the rate of survival of the strains producing acetylated MEP/alginate was significantly greater than that of strains with deficient levels of acetylation of MEP/alginate (P < 0.001, as determined by analysis of variance [ANOVA] and Fisher's probable least-significant-difference [PLSD] test). The data shown in Fig. 1 were reproduced four additional times with different adsorbed normal human sera as sources of complement (data not shown), with essentially identical results.

The above results indicate that acetylation of MEP/alginate is likely essential to the development of resistance of mucoid P. aeruginosa to basic host defenses. The very low level of complement that effectively opsonized the acetylation-deficient derivatives would make such strains prone to elimination by host defenses in the lungs. However, it is difficult to know what the actual level of complement activity is in CF lungs. Since most mucoid P. aeruginosa cells isolated from the lungs of CF patients produce rough LPS (35) and are susceptible to bactericidal killing at serum concentrations of ≥10%, it can be assumed that the levels of complement needed in chronically infected CF lungs to form the membrane attack complex capable of killing P. aeruginosa cells are <10% the levels in serum. It is not known whether the observed phagocytic killing of strains deficient in acetylation of alginate in vitro with complement concentrations as low as 1.25% is indicative of an inability of such strains to survive in CF lungs. Nonetheless, the ability of very small amounts of human serum to mediate opsonic killing of nonacetylated mucoid P. aeruginosa suggests that acetylation of MEP may be critical for bacterial resistance to host defenses during chronic lung infection in CF.

Effect of acetate substituents on antibody-independent complement activation.

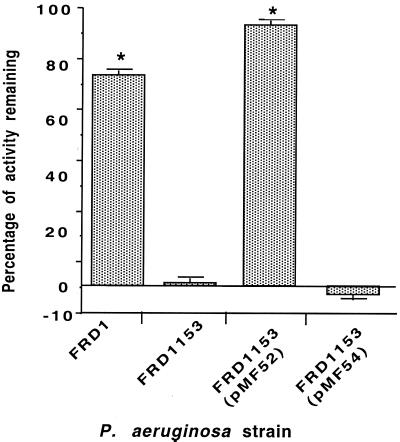

To determine the effect of acetate substituents on complement activation at serum concentrations lower than 10% that mediate phagocyte-dependent opsonic killing of the nonacetylated mutant, we compared the consumption of the activity of the alternative pathway of complement by the P. aeruginosa acetylase-deficient strains and by strains with wild-type levels of acetate. This goal was accomplished by dilution of human sera 1:10 in Veronal-buffered saline, adsorption as described above with lyophilized cells of P. aeruginosa strain FRD1 to remove specific antibody, and incubation with 107 CFU of the various strains for 30 min at 37°C. Bacteria were removed by centrifugation, and 108 rabbit red blood cells were added to the residual sera. After 30 min at 37°C, the samples were centrifuged to remove intact red blood cells, 100 μl of the supernatant was added to 96-well plates, and the amount of hemoglobin released into the supernatant was measured at 405 nm. Controls included serum samples treated with zymosan to consume all of the alternative pathway components and samples with no bacteria, whose hemoglobin release value represented 100% of the complement activity. The percentage of residual activity of the alternative pathway of complement left after incubation with each strain was calculated as follows: 100 × (optical density at 405 nm of test sample/optical density at 405 nm of sample showing 100% lysis of red blood cells). At a concentration of adsorbed, intact human serum of 6.25%, 76% of the alternative pathway activity remained after incubation with O-acetylated mucoid P. aeruginosa strain FRD1 (Fig. 2). In contrast, the poorly O-acetylated strain, FRD1153, consumed essentially all of the alternative pathway activity at this serum concentration; 96% of the alternative pathway activity remained when serum was incubated with FRD1153 containing algJ in trans, but 100% of the activity was consumed by incubation with strain FRD1153 containing only the vector control. These results are indicative of a role for the acetate substituents in abrogating the activation of the alternative pathway, an event that could lead to deposition of opsonic fragments of C3 and C4 and phagocytic killing. Therefore, at the molecular level, it appears that acetylation of alginate, particularly when it is expressed on a rough-LPS P. aeruginosa strain, dampens complement activation, leading to resistance to antibody-independent phagocytic killing.

FIG. 2.

Acetate residues on MEP/alginate inhibit activation of the alternative pathway of complement. Exposure of 6.25% adsorbed normal human serum to 107 CFU of each mucoid P. aeruginosa strain for 30 min followed by the removal of the bacteria and the evaluation of the residual complement-activating capacity of the serum showed that the fully O-acetylated strains, FRD1 and FRD1153(pMF52), activated <25% of the available complement, whereas the poorly O-acetylated strains, FRD1153 and FRD1153(pMF54), activated >98% of the available complement. Values of residual activity below 0% are due to experimental variation. Data are reported as mean and standard deviation. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between the value shown and that obtained with 100% residual activity (i.e., 100% red blood cell lysis; P <0.0001, as determined by ANOVA and Fisher's PLSD test).

Effect of acetate substituents on the functional activity of MEP-specific opsonic and nonopsonic antibodies.

Another factor involved in the pathogenesis of chronic mucoid P. aeruginosa infection in CF lungs is the lack of elicitation of an immune response that is effective at controlling infection. In other studies, we attributed this situation, in part, to the production of MEP-specific antibodies incapable of mediating opsonic killing of either suspended or biofilm-grown P. aeruginosa (27, 32, 38). Immunogenicity studies using MEP and mice have indicated that in the presence of preexisting nonopsonic antibodies to MEP, opsonic antibodies cannot be readily elicited, even with doses of MEP that do elicit opsonic antibodies in naive mice (16). Nonopsonic antibodies to MEP occur naturally in all human sera examined to date and are present in the sera of young CF patients prior to colonization with P. aeruginosa (38). These nonopsonic MEP-specific antibodies mediate high levels of complement activation in the presence of mucoid P. aeruginosa (37), but opsonic complement fragments derived following activation fail to bind efficiently to mucoid P. aeruginosa cells (37). In contrast, opsonic MEP-specific antibodies of the same immunoglobulin isotypes both activate complement and deposit opsonically active C3b and C3bi fragments onto the bacterial surface (37).

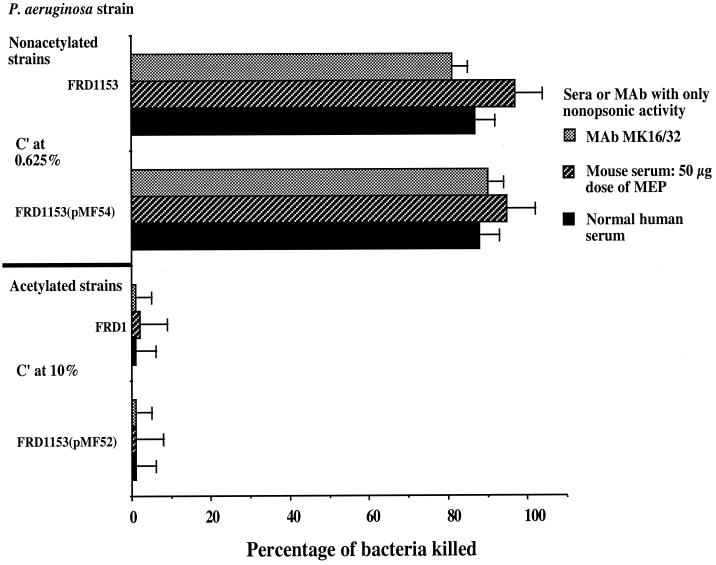

To determine whether the acetate substituents on MEP/alginate form the molecular basis for the lack of opsonic killing by nonopsonic antibodies, we carried out phagocytic assays using complement along with the following: (i) normal human serum containing naturally occurring antibodies to MEP that fail to mediate opsonic killing (36, 38), (ii) immunization-induced nonopsonic mouse antibodies obtained from mice immunized three times at 5-day intervals with purified MEP at a high dose (50 μg/dose), or (iii) an MEP-specific murine immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) monoclonal antibody that does not mediate opsonic killing of mucoid P. aeruginosa (37, 43). To determine if MEP-specific opsonic antibodies recognized acetylated epitopes, we used the following: (i) human sera with MEP-specific opsonic antibodies obtained from individuals vaccinated with purified MEP (36) (which already contained preexisting nonopsonic antibodies); (ii) sera from mice immunized three times at 5-day intervals with purified MEP at a low dose (10 μg), which elicits both opsonic and nonopsonic antibodies (16); or (iii) an opsonic IgG2a monoclonal antibody (43). To avoid phagocytic killing of the poorly acetylated strains in an antibody-independent manner, we used human serum at a concentration of 0.625%, which does not on its own opsonize nonacetylated mucoid P. aeruginosa strains for phagocytic killing. For the fully acetylated strains, we used human serum at a concentration of 10% as a source of complement. As shown in Fig. 3, even at a very low complement concentration, the usually nonopsonic antibodies readily mediated phagocytic killing of the poorly O-acetylated strains, FRD1153 and FRD1153(pMF54). In contrast, at a complement concentration of 10%, the fully O-acetylated mucoid P. aeruginosa strains, FRD1 and FRD1153(pMF42), were resistant to phagocytic killing by the nonopsonic antibodies. Data are shown for sera pooled from five immunized mice and for one normal human serum sample. The assays were repeated with four other normal human serum samples, with essentially identical results (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Opsonic killing of nonacetylated or acetylated mucoid P. aeruginosa strains in the presence of a nonopsonic monoclonal antibody (MAb), nonopsonic antibody to MEP in a normal human serum sample, and nonopsonic antibody in pooled sera from mice immunized with a high dose (50 μg) of MEP. Bars represent mean CFU killed, and error bars show the standard deviation. The percentage of the two nonacetylated strains killed by each of the three antibodies was significantly higher than the percentage of the acetylated strains killed by the corresponding antibodies (P < 0.001, as determined by ANOVA and Fisher's PLSD test for pairwise comparisons). C′, complement.

Effect of O-acetyl substituents on the functional activity of MEP-specific opsonic antibodies.

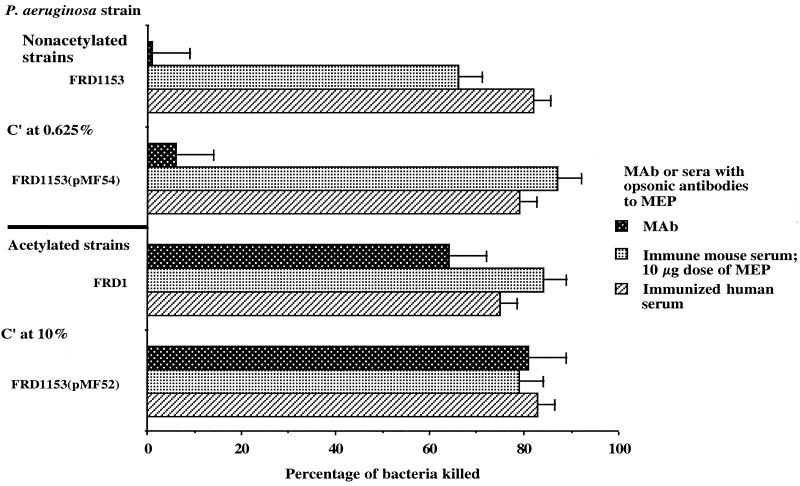

Sera obtained from mice or humans vaccinated with MEP and developing specific opsonic antibodies killed both poorly and fully acetylated mucoid P. aeruginosa strains in the phagocytic assay (Fig. 4). Again, data are shown for sera pooled from five immunized mice and for one immunized human serum sample, but the assays were repeated with four other immunized human serum samples, with essentially identical results (data not shown). The poorly acetylated strains were phagocytosed due to the concomitant presence of MEP-specific nonopsonic antibodies in the sera from the vaccinated mice and humans. However, when a murine IgG2a monoclonal antibody with opsonic killing activity was used, only the fully acetylated strains were opsonized for phagocytic killing (Fig. 4), a result indicating that acetate substituents form the epitope recognized by opsonic antibodies in vaccinated mouse and human sera and by the murine opsonic monoclonal antibody.

FIG. 4.

Opsonic killing of nonacetylated or acetylated mucoid P. aeruginosa strains in the presence of opsonic monoclonal antibody (MAb 9/5/23) to MEP, opsonic antibody in serum from a person immunized with MEP, or opsonic antibody in sera pooled from mice immunized with a low dose (10 μg) of MEP. Bars represent the mean CFU killed, and error bars show the standard deviation. The percentage of the two nonacetylated strains killed by the opsonic MAb was significantly lower than the percentage killed by the other antibody preparations (P < 0.01, as determined by ANOVA and Fisher's PLSD test for pairwise comparisons). The immune mouse and human sera killed the nonacetylated strains because of the concomitant presence of nonopsonic antibody induced by immunization in mice (a 10-μg dose of MEP elicits both opsonic and nonopsonic antibodies) or occurring naturally in humans.

Overall, our results indicate one potential molecular basis for the pathogenesis of chronic mucoid P. aeruginosa infection in CF lungs. O acetylation of MEP/alginate prevents activation of the alternative pathway of complement; the result is resistance to antibody-independent phagocytosis. In addition, acetylation of MEP/alginate precludes phagocytic killing by the nonopsonic antibodies to MEP found both in normal human sera and at high titers in the sera of infected CF patients (38). Acetate residues appear to be key factors in the epitope that is recognized by protective human and murine opsonic antibodies (39), and complement activation by these antibodies leads to phagocytic killing via deposition of C3b and C3bi (37). Phagocytic killing of mucoid P. aeruginosa correlates with the resistance of older, uninfected CF patients to infection with mucoid P. aeruginosa (32, 38) as well as with protective efficacy in rodent models of endobronchial infection with mucoid P. aeruginosa (39). In addition, acetate residues on MEP/alginate have been shown to be able to scavenge hypochlorite produced by activated phagocytes, potentially protecting mucoid P. aeruginosa from this host defense (20), as well as to suppress neutrophil and lymphocyte antibacterial functions and responses (21). Thus, O-acetyl substituents are likely one of the important components of MEP/alginate protecting mucoid P. aeruginosa from host defenses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Hyett, Denise DesJardins, and Elizabeth Kieff for contributions to this work.

Support was obtained from NIH grants AI 22836 (to G.B.P.), AI46588 (to M.F.), and AI 19146 (to D.E.O.) and from Veterans Administration Medical Research Funds (to D.E.O.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames P, DesJardins D, Pier G B. Opsonophagocytic killing activity of rabbit antibody to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1985;49:281–285. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.281-285.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boucher J C, Martinez-Salazar J, Schurr M J, Mudd M H, Yu H, Deretic V. Two distinct loci affecting conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis encode homologs of the serine protease HtrA. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:511–523. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.511-523.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher J C, Schurr M J, Yu H, Rowen D W, Deretic V. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: role of mucC in the regulation of alginate production and stress sensitivity. Microbiology. 1997;143:3473–3480. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-11-3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chitnis C E, Ohman D E. Cloning of Pseudomonas aeruginosa algG, which controls alginate structure. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2894–2900. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2894-2900.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chitnis C E, Ohman D E. Genetic analysis of the alginate biosynthetic gene cluster of Pseudomonas aeruginosa shows evidence of an operonic structure. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:583–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darzins A, Chakrabarty A M. Cloning of genes controlling alginate biosynthesis from a mucoid cystic fibrosis isolate of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:9–18. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.1.9-18.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies D G, Parsek M R, Pearson J P, Iglewski B H, Costerton J W, Greenberg E P. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Kievit T R, Iglewski B H. Quorum sensing, gene expression, and Pseudomonas biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 1999;310:117–128. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)10010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demko C A, Byard P J, Davis P B. Gender differences in cystic fibrosis: Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00230-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deretic V, Govan J R W, Konyecsni W M, Martin D W. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis—mutations in the muc loci affect transcription of the algR and algD genes in response to environmental stimuli. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deretic V, Martin D W, Schurr M J, Mudd M H, Hibler N S, Curcic R, Boucher J C. Conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Bio/Technology. 1993;11:1133–1136. doi: 10.1038/nbt1093-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deretic V, Schurr M J, Boucher J C, Martin D W. Conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to mucoidy in cystic fibrosis: environmental stress and regulation of bacterial virulence by alternative sigma factors. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2773–2780. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2773-2780.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Vries C A, Ohman D E. Mucoid-to-nonmucoid conversion in alginate-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa often results from spontaneous mutations in algT, encoding a putative alternate sigma factor, and shows evidence for autoregulation. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6677–6687. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6677-6687.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin J M, Ohman D E. Identification of algF in the alginate biosynthetic gene cluster of Pseudomonas aeruginosa which is required for alginate acetylation. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5057–5065. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5057-5065.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin J M, Ohman D E. Identification of algI and algJ in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate biosynthetic gene cluster which are required for alginate O acetylation. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2186–2195. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2186-2195.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garner C V, DesJardins D, Pier G B. Immunogenic properties of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1835–1842. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1835-1842.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberg J B, Ohman D E. Cloning and expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa of a gene involved in the production of alginate. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:1115–1121. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.3.1115-1121.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hancock R E W, Mutharia L M, Chan L, Darveau R P, Speert D P, Pier G B. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis: a class of serum-sensitive, nontypeable strains deficient in lipopolysaccharide O side chains. Infect Immun. 1983;42:170–177. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.1.170-177.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hostetter K M, Thomas M L, Rosen F S, Tack B F. Binding of C3b proceeds by a transesterification reaction at the thiolester site. Nature. 1982;298:72–75. doi: 10.1038/298072b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Learn D B, Brestel E P, Seetharama S. Hypochlorite scavenging by Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1813–1818. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.8.1813-1818.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mai G T, Seow W K, Pier G B, McCormack J G, Thong Y H. Suppression of lymphocyte and neutrophil functions by Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide (alginate): reversal by physicochemical, alginase, and specific monoclonal antibody treatments. Infect Immun. 1993;61:559–564. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.559-564.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin D W, Holloway B W, Deretic V. Characterization of a locus determining the mucoid status of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: AlgU shows sequence similarities with a Bacillus sigma factor. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1153–1164. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1153-1164.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin D W, Schurr M J, Mudd M H, Govan J R, Holloway B W, Deretic V. Mechanism of conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infecting cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8377–8381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathee K, Ciofu O, Sternberg C, Lindum P W, Campbell J I, Jensen P, Johnsen A H, Givskov M, Ohman D E, Molin S, Hoiby N, Kharazmi A. Mucoid conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by hydrogen peroxide: a mechanism for virulence activation in the cystic fibrosis lung. Microbiology. 1999;145:1349–1357. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathee K, McPherson C J, Ohman D E. Posttranslational control of the algT (algU)-encoded sigma22 for expression of the alginate regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and localization of its antagonist proteins MucA and MucB (AlgN) J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3711–3720. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3711-3720.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May T B, Shinabarger D, Maharaj R, Kato J, Chu L, DeVault J D, Roychoudhury S, Zielinski N A, Berry A, Rothmel R, Misra T K, Chakrabarty A M. Alginate synthesis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a key pathogenic factor in chronic pulmonary infection of cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:191–206. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meluleni G J, Grout M, Evans D J, Pier G B. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa growing in a biofilm in vitro are killed by opsonic antibodies to the mucoid exopolysaccharide capsule but not by antibodies produced during chronic lung infection in cystic fibrosis patients. J Immunol. 1995;155:2029–2038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohman D E, Chakrabarty A M. Genetic mapping of chromosomal determinants for the production of the exopolysaccharide alginate in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolate. Infect Immun. 1981;33:142–148. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.1.142-148.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohman D E, Goldberg J B, Flynn J L. Molecular analysis of the genetic switch activating alginate production. In: Silver S, Chakrabarty A, Iglewski B, Kaplan S, editors. Pseudomonas: biotransformations, pathogenesis, and evolving biotechnology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ojeniyi B, Baek L, Hoiby N. Polyagglutinability due to loss of O-antigenic determinants in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from cystic fibrosis patients. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 1985;93:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1985.tb02844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Toole G A, Kolter R. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:295–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parad R B, Gerard C J, Zurakowski D, Nichols D P, Pier G B. Pulmonary outcome in cystic fibrosis is influenced primarily by mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and immune status and only modestly by genotype. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4744–4750. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4744-4750.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedersen S S, Hoiby N, Espersen F, Koch C. Role of alginate in infection with mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 1992;47:6–13. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Penketh A, Pitt T, Roberts D, Hodson M E, Batten J C. The relationship of phenotype changes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the clinical condition of patients with cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:605–608. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.127.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pier G B, Ames P. Mediation of the killing of rough, mucoid isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis by the alternative pathway of complement. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:223–228. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pier G B, DesJardins D, Grout M, Garner C, Bennett S E, Pekoe G, Fuller S A, Thornton M O, Harkonen W S, Miller H C. Human immune response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide (alginate) vaccine. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3972–3979. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3972-3979.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pier G B, Grout M, DesJardins D. Complement deposition by antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide (MEP) and by non-MEP specific opsonins. J Immunol. 1991;147:1869–1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pier G B, Saunders J M, Ames P, Edwards M S, Auerbach H, Goldfarb J, Speert D P, Hurwitch S. Opsonophagocytic killing antibody to Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid exopolysaccharide in older, non-colonized cystic fibrosis patients. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:793–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709243171303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pier G B, Small G J, Warren H B. Protection against mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in rodent models of endobronchial infection. Science. 1990;249:537–540. doi: 10.1126/science.2116663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell N J, Gacesa P. Chemistry and biology of the alginate of mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Mol Aspects Med. 1988;10:1–91. doi: 10.1016/0098-2997(88)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sherbrock-Cox V, Russell N J, Gacesa P. The purification and chemical characterisation of the alginate present in extracellular material produced by mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Carbohydr Res. 1984;135:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(84)85012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh P K, Schaefer A L, Parsek M R, Moninger T O, Welsh M J, Greenberg E P. Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature. 2000;407:762–764. doi: 10.1038/35037627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Speert D P, Dinmick J E, Pier G B, Saunders J M, Hancock R E W, Kelly N. An immunohistological evaluation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pulmonary infection in two patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Res. 1987;22:743–747. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198712000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Storey D G, Ujack E E, Mitchell I, Rabin H R. Positive correlation of algD transcription to lasB and lasA transcription by populations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4061–4067. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4061-4067.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whiteley M, Lee K M, Greenberg E P. Identification of genes controlled by quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye R W, Zielinski N A, Chakrabarty A M. Purification and characterization of phosphomannomutase/phosphoglucomutase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa involved in biosynthesis of both alginate and lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4851–4857. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4851-4857.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu H, Schurr M J, Deretic V. Functional equivalence of Escherichia coli sigma E and Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgU: E. coli rpoE restores mucoidy and reduces sensitivity to reactive oxygen intermediates in algU mutants of P. aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3259–3268. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3259-3268.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zielinski N A, Maharaj R, Roychoudhury S, Danganan C E, Hendrickson W, Chakrabarty A M. Alginate synthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa—environmental regulation of the algC promoter. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7680–7688. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.23.7680-7688.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]