Abstract

Introduction

Small cell carcinoma of the bladder (SCCB) is a rare variant of bladder cancer with poor outcomes. We evaluated long-term outcomes of nonmetastatic (M0) and metastatic (M1) SCCB and correlated pathologic response with genomic alterations of patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC).

Patients and Methods

Clinical history and pathology samples from SCCB patients diagnosed at our institution were reviewed.

Results

One hundred and ninety-nine SCCB patients were identified. (M0: 147 [74%]; M1: 52 [26%]). Among M0 patients, 108 underwent radical cystectomy (RC) (NAC: 71; RC only: 23; adjuvant chemotherapy: 14); 14 received chemoradiotherapy; the rest received chemotherapy alone or no cancer-directed therapy. RC-only patients had a median follow-up of 9.1 years, and median disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were 1.1 and 1.2 years, respectively. NAC patients had pathologic response (<pT2pN0) and pathologic complete response (pT0pN0) rates of 48% and 38%, respectively, with median follow-up of 7.2 years, and median DFS and OS of 5.6 and 14.5 years, respectively. NAC responders (<ypT2N0) had superior median DFS (14.5 vs. 0.6 years, hazard ratio [HR] 0.24, P< .001) and OS (14.5 vs. 2.5 years, HR 0.31, P = .002). DFS rates for responders and nonresponders were 76% and 27% at 5 years, and 71% and 23% at 10 years, respectively. Local and central nervous system recurrences were infrequent. Median progression-free survival (PFS) and OS for M1 disease were 6.9 and 10.3 months, respectively. Genomic profiling was performed on 47 NAC patients. Loss of ERCC2 function was significantly enriched among those with pathologic complete response to NAC (mutations present in 50% of pathologic complete responders vs. 15% nonresponders, P = .045).

Conclusion

M0 SCCB is chemo-sensitive and patients have excellent long-term survival following response to NAC. Patients with M1 disease have poor survival despite systemic therapy. Loss-of-function mutations of ERCC2 were associated with pathologic complete response to NAC.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, Radical cystectomy, Small cell carcinoma of the bladder, Urothelial carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Small cell carcinoma of the bladder (SCCB) is a rare and aggressive histologic subtype of bladder cancer. Although SCCB comprises <5% of all cancers of the bladder and urinary tract, it represents one of the most common sites of extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma [1, 2].

Due to the rarity of SCCB, optimal management remains poorly defined. Platinum-based chemotherapy is the basis of treatment for metastatic disease (M1), while management of non-metastatic disease (M0) is commonly divided into two approaches: peri-operative chemotherapy and radical cystectomy, or concurrent chemoradiotherapy, similar to treatments for limited-stage small cell lung cancer.

In describing our institution’s experience in managing SCCB with long term follow-up, this study aimed to: (1) describe the natural history of M0 and M1 disease with long-term follow-up, (2) determine the impact of platinum-based chemotherapy on clinical outcomes in non-metastatic disease, and (3) identify clinical and genomic parameters that might correlate with clinical outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

All cases of SCCB diagnosed at our institution from 1990-2015 were identified and reviewed by genitourinary pathologists (XH, HAA) to confirm diagnosis, provide quantification of the small-cell component, and identify the presence of non-small cell components. Only cases with clinical follow-up were included for analysis. This research was performed under an IRB–approved protocol.

Cases were classified as either M0 or M1 based on absence or presence of distant metastases at diagnosis. M0 cases were confirmed to be invasive disease on pathology review. Clinical data were extracted from individual medical records.

Genomic Analysis

A subset of patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) had pretreatment tumors sequenced using Memorial Sloan Kettering Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT), an FDA-authorized next-generation sequencing platform [3]. Tumors were analyzed using one of three versions of the assay, each of which examines all exons and selected introns for 341 – 468 genes. All loss-of-function alterations were considered deleterious, including deletions, nonsense mutations, and frameshift or splice site alterations. For missense mutations, deleterious status was determined by manual review of the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer [4], algorithmically determined recurrent hotspot mutations [5], and annotation of oncogenicity by OncoKB [6]. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) and fraction of genome altered (FGA) for each sample were analyzed as well.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized across relevant clinical variables. Association of treatment groups with respect to categorical outcome data types were assessed via Fisher’s exact test, and continuous data types were assessed via Wilcoxon rank sum test. Survival endpoints were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences in survival between groups were assessed via log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate models were built using Cox proportional hazards models. For patients with M0, overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of cystectomy (or primary radiotherapy or systemic therapy initiation for those who did not undergo cystectomy/radiotherapy) to time of death, while disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated as the time to disease recurrence or death. Pathologic response was defined as <pT2pN0 following NAC and pathologic complete response was defined as pT0pN0 following NAC. For M1 patients, OS and progression-free survival (PFS) were calculated from the start of systemic therapy to death, and to progression or death, respectively.

RESULTS

Patient and pathologic characteristics

Of 199 patients with clinical follow-up, 52 (26%) had M1 and 147 had M0 disease (Supplemental Figure 1). Compared to the M1 cohort, the M0 cohort had more women (25% vs. 12%, p=0.049) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population with Small Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder, Including Non-Metastatic (M0) and Metastatic (M1) Cases

| M0 | M1 | Total | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 147 (74%) | 52 (26%) | 199 | ||

| Gender | 0.049 | |||

| Female | 37 (25%) | 6 (12%) | 43 (22%) | |

| Male | 110 (75%) | 46 (88%) | 156 (78%) | |

|

| ||||

| Age | 70 | 69 | 0.836 | |

| Range | 39 - 96 | 47 - 95 | ||

|

| ||||

| ECOG Performance Status | 0.071 | |||

| 0-1 | 121 (82%) | 39 (75%) | 160 (80%) | |

| 2 | 8 (5%) | 7 (13%) | 15 (8%) | |

| Not documented | 18 (12%) | 6 (12%) | 24 (12%) | |

|

| ||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.062 | |||

| No | 32 (22%) | 5 (10%) | 37 (19%) | |

| Yes | 115 (78%) | 47 (90%) | 162 (81%) | |

|

| ||||

| Platinum Agent | 0.028 | |||

| Carboplatin | 32 (28%) | 18 (38%) | 50 (31%) | |

| Cisplatin | 80 (70%) | 24 (51%) | 104 (64%) | |

| Non-Platinum | 3 (3%) | 5 (11%) | 8 (5%) | |

|

| ||||

| Regimen Category | 1.000 | |||

| Small cell | 93 (81%) | 38 (81%) | 131 (81%) | |

| Urothelial or other | 22 (19%) | 9 (19%) | 31 (19%) | |

|

| ||||

| Prior Cystectomy | ||||

| No | NA | 39 (75%) | ||

| Yes | NA | 13 (25%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Visceral Metastasis | ||||

| No | NA | 26 (50%) | ||

| Yes | NA | 26 (50%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Number of Metastatic Sites | ||||

| 1 | NA | 32 (62%) | ||

| 2 | NA | 15 (29%) | ||

| 3 | NA | 4 (8%) | ||

| 4 | NA | 1 (2%) | ||

Abbreviations: ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Associations with treatment groups with respect to categorical outcome data types were assessed via Fisher’s xxact test, and continuous data types were assessed via Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Based on pretreatment biopsies, 157 tumors (79%) had >90% small cell component and 18 (9%) had <50% small cell component. A third (35%) had a urothelial carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS) component. Divergent or variant histologies included: glandular (18%), squamous (4%) and sarcomatoid differentiation (3%). Twenty-eight of the M0 patients had T1 disease on transurethral resection with no definite evidence of muscle invasion. Six patients underwent up-front radical cystectomy (RC) (post-op pathology: pT2pN0, n=1; pT3pN0, n=2; pT3pN1, n=1; pT4pN0, n=1), 4 chemoradiotherapy, 3 chemotherapy only, and 4 neoadjuvant chemotherapy and RC; 3 did not receive cancer-directed therapy.

Most patients (81%) received systemic therapy – 78% and 90% of M0 and M1 patients, respectively (p=0.062). All these patients received small cell-specific chemotherapy regimens (platinum-etoposide or cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine). M0 patients were more likely to receive cisplatin-based chemotherapy than M1 patients (70% vs. 51%, p=0.028).

Non-Metastatic (M0) Cohort

Therapeutic disposition for the 147 patients with M0 disease is outlined in Supplemental Figure 1. Of these patients, 108 underwent radical cystectomy. NAC was administered to 71 patients (66%), 14 (13%) received adjuvant chemotherapy, and 23 (21%) did not receive peri-operative chemotherapy. Of the 39 patients who did not undergo radical cystectomy, 14 (36%) received definitive chemoradiotherapy, 16 (41%) received chemotherapy only, and 9 (23%) did not receive cancer-directed therapy due to poor performance status. Patient demographics are tabulated in Supplemental Table 1 along with DFS and OS (Figure 1). Of 15 patients treated with bladder radiotherapy, 3 had local recurrence, 1 of which was muscle-invasive.

Figure 1.

(A) Disease-free survival for small cell carcinoma of the bladder managed by radical cystectomy with or without perioperative chemotherapy. (B) Disease-free survival for M0 small cell carcinoma of the bladder managed without radical cystectomy and progression-free survival for M1 small cell carcinoma of the bladder. (C) Overall survival for small cell carcinoma of the bladder managed by radical cystectomy with or without perioperative chemotherapy. (D) Overall survival for small cell carcinoma of the bladder managed without radical cystectomy. ACT = adjuvant chemotherapy; chemoRT = chemoradiotherapy; M0 = non-metastatic disease; M1 = metastatic disease; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RC = radical cystectomy; yrs = years.

Impact of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Non-Metastatic Small Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder

Table 2 details the pathologic stage distributions between patients who received NAC (n=71) and those who did not (cystectomy only, n = 23; adjuvant chemotherapy, n = 14). NAC-treated patients had a lower rate of extravesical (pT3-4) disease on pathologic evaluation compared to those who did not receive NAC (34% vs. 62%, p<0.001), although rates of nodal involvement were comparable (13% vs. 14%, p=0.77). Among patients who received NAC, the observed pathologic response rate (<pT2pN0) and pathologic complete response rate (pT0pN0) were 48% and 38%, respectively.

Table 2.

Pathologic Stage Distribution for Patients with Non-Metastatic Small Cell Carcinoma Who Received Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Cystectomy and Patients Who Underwent Upfront Cystectomy

| Neoadjuvant (n=71) | Upfront Cystectomy (n=37) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pT-stage | 0.001 | ||

| 0,1,2 | 47 (66%) | 11 (30%) | |

| 3,4 | 24 (34%) | 26 (70%) | |

|

| |||

| 0N-stage | 1.000 | ||

| Node negative | 62 (87%) | 29 (78%) | |

| Node positive | 9 (13%) | 5 (14%) | |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 3(8%) | |

|

| |||

| AJCC Stage | 0.008 | ||

| 0,I,II | 43 (61%) | 12 (32%) | |

| III/IV | 28 (39%) | 25 (68%) | |

Abbreviations: AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer

Associations assessed via Fisher’s exact test.

All patients who underwent NAC received platinum-based chemotherapy (cisplatin: n=55, 77%; carboplatin: n=16, 23%). Most patients were treated with small cell-type regimens (platinum-etoposide: n=58, 82%) while 12 patients (17%) received urothelial carcinoma-type regimens (platinum-gemcitabine: n=8; MVAC: n=4). One received carboplatin/paclitaxel.

Pathologic complete response rates with cisplatin- and carboplatin-based regimens were 40% and 31% (p=0.574), respectively. Pathologic downstaging rates for cisplatin- and carboplatin-based regimens were 49% vs. 44% (p=0.781), respectively. Pathologic complete response rates with a small cell-directed chemotherapy regimen vs a urothelial carcinoma-directed regimen were 41% and 25% (p=0.346), respectively, and pathologic downstaging rates were 51% and 33% (p=0.349), respectively. Downstaging occurred in 43% of pure small cell tumors versus 33% of tumors with components of urothelial carcinoma, NOS, or other variant histologies, with pathologic complete response in 51% versus 44%, respectively (p = 0.638).

NAC-treated patients had better outcomes compared to cystectomy-only patients (DFS: hazard ratio [HR] 0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.29–0.87; p=0.015; OS: HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.21–0.65; p<0.001). Median follow-up for NAC-treated patients was 7.2 years with a median DFS and OS of 14.5 and 14.5 years, respectively, and median follow-up for cystectomy-only patients was 9.1 years with a median DFS and OS of 1.1 and 1.2 years, respectively. Cystectomy-only patients were significantly older than NAC-treated patients (77 years vs 68 years, p=0.001). Univariate analysis showed that NAC and age, but not performance status, were significantly associated with DFS and OS. After adjusting for age, NAC was statistically associated with improvement in OS but not DFS (Supplemental Table 2).

DFS and OS: NAC responders vs. non-responders

We further analyzed the survival difference between pathologic responders (defined by pathologic downstaging: <pT2pN0) and non-responders to NAC (defined by residual muscle-invasive or higher stage disease at cystectomy). The proportion of patients who received cisplatin-based chemotherapy (76% vs. 79%, p=0.781) or small cell-directed regimens (78% vs. 88%, p=0.349) between responders and non-responders were similar.

Compared to NAC non-responders, NAC responders had higher median DFS (14.5 vs. 0.6 years, HR 0.24, p<0.001) and OS (14.5 vs. 2.5 years, HR 0.31, p=0.002) (Figure 2). DFS rates for responders and non-responders were estimated to be 76% vs 27% at 5 years, and 71% vs 23% at 10 years, respectively. Landmark OS rates for responders and non-responders were estimated to be 79% vs 39% at 5 years, and 74% vs 36% at 10 years, respectively.

Figure 2.

(A) Disease-free survival for non-metastatic small cell carcinoma of the bladder based on pathologic response (<ypT2pN0) to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. (B) Overall survival for non-metastatic small cell carcinoma of the bladder based on pathologic response (<ypT2pN0) to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. M0 = non-metastatic disease; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; yrs = years.

Radiographically confirmed metastatic disease was eventually observed in 2/34 (6%) responders compared to 18/37 (49%) non-responders (p<0.001). Patterns of metastatic recurrence are shown in Supplemental Table 3. Among non-responders, radiographically confirmed metastatic recurrences were detected in 5/13 (38%) ypT2 tumors, 11/22 (50%) ypT3 tumors and 2/2 (100%) of ypT4 tumors.

Clinical Outcomes of Metastatic Small Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder

The majority of M1 patients had one to two sites of metastatic disease at presentation (one site: 62%, two sites: 29%). Only ten patients had baseline CNS imaging. The most common sites of metastatic involvement were non-regional lymph nodes (42%), liver (29%), and bone (12%). No CNS metastases were identified at presentation. Radiographic progression was documented in 23/47 patients who received systemic therapy, most commonly involving liver (n=8, 35%), followed by bones, lungs, and distant lymph nodes (n=4, 17% each), and locoregional progression (n=3, 13%). There were four cases of CNS metastases at progression following first-line systemic therapy, three with brain parenchymal involvement and one with leptomeningeal involvement.

Of the 52 M1 patients, 47 (90%) received chemotherapy. Most received platinum-based chemotherapy regimens (cisplatin: n=24, 51%; carboplatin: n=18, 38%) while the remaining five received either cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine (n=1), gemcitabine/doxorubicin (n=2), single agent paclitaxel (n=1), or etoposide monotherapy (n=1). With a median follow-up of 2.7 years, median PFS and OS for the entire M1 cohort were 6.9 and 10.3 months, respectively (Figure 1).

In a Cox proportional model of potential predictors of PFS and OS for M1 patients treated with chemotherapy, ECOG performance status, presence of visceral metastases, type of platinum agent (cisplatin vs carboplatin) or types of chemotherapy regimen (neuroendocrine-specific vs others) were not associated with PFS. For OS, only ECOG performance status was prognostic (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate Analysis for Overall Survival (OS) and Progression-Free Survival (PFS) for Patients with Metastatic Small Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder

| Univariate Analysis for OS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| HR (95%CI) | p-value | ||

|

| |||

| Platinum Agent | Carboplatin | ref | |

| Cisplatin | 0.73 (0.38-1.39) | 0.337 | |

|

| |||

| ECOG Performance Status | 0-1 | ref | |

| 2 | 5.01 (1.51-16.66) | 0.009 | |

|

| |||

| Visceral Metastasis | Absent | ref | |

| Present | 1.40 (0.74-2.68) | 0.302 | |

|

| |||

| Chemotherapy Type | Small cell regimen | ref | |

| Urothelial regimen | 0.57 (0.23-1.42) | 0.226 | |

|

| |||

| Univariate Analysis for PFS | |||

|

| |||

| HR (95%CI) | p-value | ||

|

| |||

| Platinum Agent | Carboplatin | ref | |

| Cisplatin | 0.7[0.37-1.33] | 0.281 | |

|

| |||

| ECOG Performance Status | 0-1 | ref | |

| 2 | 2.21[0.75-6.47] | 0.149 | |

|

| |||

| Visceral Metastasis | Absent | ref | |

| Present | 1.32[0.7-2.52] | 0.390 | |

|

| |||

| Chemotherapy Type | Small cell regimen | ref | |

| Urothelial regimen | 0.56[0.22-1.38] | 0.208 | |

Abbreviations: HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, OS = overall survival, ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, PFS = progression-free survival

Genomic Predictors

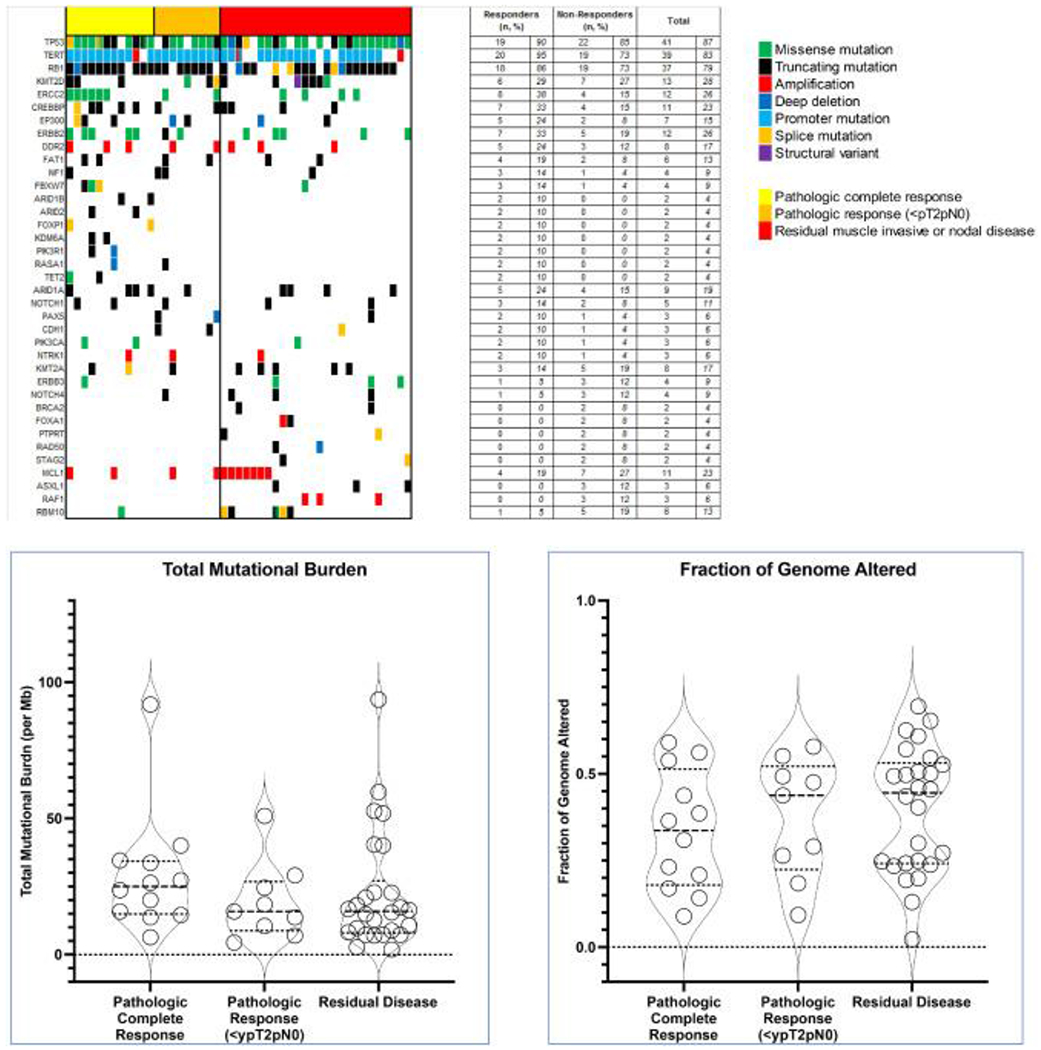

Targeted next-generation sequencing was performed on 47 neoadjuvant-treated pre-treatment tumors (21 responders [12 with pathologic complete response and 9 with residual non-muscle invasive disease <ypT2pN0] and 26 non-responders). The most commonly altered genes with ≥10% prevalence were, in order of descending frequency: TP53 (87%), TERT promoter (83%), RB1 (79%), KMT2D (28%), ERCC2 (26%), ERBB2 (26%), CREBBP (23%), MCL1 (23%), ARID1A (19%), DDR2 (17%), MYCL (17%), KMT2A (17%), EP300 (15%), FAT1 (13%), CDKN1A (13%), RICTOR (13%), PTEN (13%), RMB10 (13%) and NOTCH1 (11%). Only four cases (9%) harbored pathogenic FGFR3 alterations.

ERCC2 hotspot alterations were significantly enriched among those with pathologic complete response to NAC compared to non-responders (p=0.045) but only a trend was observed when all responders were compared to non-responders (p=0.100) (6/12 [50%] pathologic complete responders [ypT0N0], 2/9 [22%] responders with residual non-muscle invasive disease [<ypT2N0] and 4/26 [15%] non-responders). No other potential associations were observed (Figure 3A; Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 3A.

Oncoprint of 47 cases of non-metastatic small cell carcinoma of the bladder, arranged via response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (x-axis) and decreasing prevalence in genomic alterations (y-axis). Only top 30 most altered genes are shown.

B. Total mutational burden and fraction of genomic for 47 cases of neoadjuvantly-treated small cell of the bladder based on pathologic responses.

Median TMB for the entire cohort was 16.7 mut/Mb (interquartile range: 9.7 – 29.1) and median FGA was 0.40 (interquartile range: 0.23 – 0.53). No differences in TMB and FGA distributions were observed based on pathologic responses. (Figure 3B).

DISCUSSION

SCCB is a rare disease with an aggressive clinical course. Our dataset represents one of the largest single center series of chemotherapy-treated SCCB with long-term follow-up. For M0 disease, neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy was associated with high pathologic response rate, which was associated with durable long-term disease control with a median follow-up time of over seven years. Persistent invasive disease following NAC, similar to urothelial carcinoma of the bladder, was associated with high risk of recurrence, predominantly within the first two to three years of surgery, with a quarter of patients maintaining disease-free status over a longer period of time. M1 status was associated with dramatically worse outcomes.

There is no standardized treatment approach for SCCB, and treatment choice is predicated upon institutional and geographic preferences. For organ-confined SCCB, our institution has adopted an approach similar to that used for muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma, using NAC followed by radical cystectomy for most patients. In the United Kingdom, >50% of patients with localized SCCB underwent radiation therapy while only 30% underwent radical cystectomy [7]. However, a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis indicated increased utilization of NAC plus radical cystectomy and less use of chemoradiotherapy in the United States between 2001 and 2016 [8]. There are no conclusive data comparing both approaches [7, 9–11]. Our data, along with those from other groups, consistently demonstrated that for non-metastatic SCCB, a multimodality approach incorporating locoregional therapy with surgery or radiotherapy, along with systemic therapy, provides the best outcomes compared to cystectomy or radiotherapy alone [7, 9, 10, 12]. Notably, selection bias remains a major limitation when comparing outcomes across modalities.

Neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy improves survival, especially among pathologic responders. In a large series from MD Anderson Cancer Center, 48 of 125 patients with resectable disease received neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy, which was associated with a pathologic response rate of 62% and pT0/pTisN0 rate of 58% at cystectomy. Responders experienced significantly longer OS [13]. Our observations were consistent with this experience, and recurrence rates were high among non-responders. Of note, we observed that an estimated 27% and 23% of non-responders remained recurrence-free at 5 and 10 years, respectively.

Metastatic SCCB, on the other hand, was associated with exceedingly poor PFS and OS. In our M1 cohort, the 47 patients who received systemic therapy had PFS and OS between 6.9 and 10.3 months, respectively, which were consistent with the range of 7.6 [14] to 13 months [7, 12] reported in the literature. These are poor outcomes compared to urothelial carcinoma, NOS [15].

Patterns of recurrence in SCCB were distinctive from small cell carcinoma of the lung or urothelial carcinoma. In contrast to small cell carcinoma of the lung, we saw very low rates of CNS involvement in both site of recurrence (10% of all documented radiographic recurrences, 3% among the entire population) following definitive therapy for M0 disease and site of progression (17%, n=4) for M1 disease; this was concordant with other series. A multicenter UK series observed 1.5% CNS involvement throughout the entire disease trajectory of 409 patients [7], and an Irish study identified a 6.4% rate of brain metastasis in their extrapulmonary small cell population [2]. However, we also observed very low rates of local recurrence or progression, reaffirming the systemic nature of SCCB.

Consistent with previous reports [16, 17], the majority of SCCB harbored genomic alterations in TP53, RB1, and TERT promoter. Pathogenic ERCC2 alterations were significantly enriched among those with pathologic complete response following NAC. The ERCC2 protein is involved in nucleotide excision repair [18] and ERCC2 loss of function has been associated with enhanced platinum response in urothelial carcinoma [19–21], further supporting a shared origin between SCCB and urothelial carcinoma [16]. Our population represents the largest genomically characterized neoadjuvantly-treated SCCB population with pathologic outcomes. Unfortunately, no apparent genomic markers of response or resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy other than ERCC2 alterations were observed.

Although immune checkpoint blockade [22] and antibody-drug conjugates such as enfortumab vedotin [23] have become established therapeutic options for urothelial carcinoma, they remain under-explored in SCCB. SCCB may have substantially lower immune cell density [24] with PD-L1 expression ranging from 0% to 50% [24, 25]. On the other hand, we observed a higher distribution of TMB in SCCB compared to urothelial carcinoma, which may be associated with response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, clinical activity with checkpoint blockade to date remains mixed [26, 27]. Nectin-4 expression, the target of enfortumab vedotin, was shown to be low in SCCB, likely precluding meaningful clinical activity [28]. Currently, the phase II ICONIC trial of rare genitourinary cancers (A031702, NCT02496208), has an arm evaluating the role of nivolumab, ipilimumab, and cabozantinib in platinum-refractory SCCB.

Conclusions:

In our large single center dataset with long-term clinical follow-up and detailed annotation, non-metastatic SCCB may be associated with long-term survival especially among pathologic responders to neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. However, patients with M1 disease have a high mortality rate with the use of standard chemotherapy. Other treatment approaches are desperately needed, especially for patients with metastatic disease.

Clinical Practice Points

Small cell carcinoma of the bladder is known to be rare and sensitive to platinum-based chemotherapy but is associated with aggressive clinical course especially in the metastatic setting.

For localized disease, management typically consists of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy, extrapolated from management of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and small cell lung cancer. To date, only one other series from MDACC demonstrated that pathologic response in SCCB was associated with longer survival. Our data with median follow-up of 7 – 9 years independently confirms that pathologic downstaging to non-invasive disease is a positive predictor of long-term outcome in SCCB. Even among non-responders to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, risk of recurrence plateaued, and long-term survival remained possible. Unlike small cell carcinoma of the lung, central nervous system involvement was rare and infrequent in our large SCCB cohort.

Our data also represent the largest effort to date evaluating associations between genomic alterations and response of SCCB to platinum-based chemotherapy. SCCB is associated with higher tumor mutation burden and alterations in the DNA damage response and repair (DDR) gene ERCC2 were associated with pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, reflecting observations from urothelial cancer of the bladder.

Our data reaffirm the importance and survival benefit of systemic therapy for patients with SCCB, in addition to cystectomy, especially among pathologic responders. Ongoing studies in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder are assessing whether alterations of ERCC2 and other DDR genes may allow for bladder preservation, findings which may also potentially benefit those with SCCB.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Study population. ACT = adjuvant chemotherapy; CRT = chemoradiotherapy; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RC = radical cystectomy.

Supplemental Figure 2. Oncoprint of 47 cases of non-metastatic small cell carcinoma of the bladder, arranged via response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (x-axis).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (NIH/NCI) [grant numbers R01 CA233899, P30 CA008748, P50CA221745] and Cycle for Survival. B.J. Guercio is supported by the NIH/NCI [grant number T32-CA009207], an Oncocyte Conquer Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award, and a Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network Young Investigator Award. E. Pietzak is supported by the NIH/NCI K12 Paul Calabresi Career Development Award for Clinical Oncology [grant number K12 CA184746]. B. Weigelt is funded in part by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and Cycle for Survival. Sponsors of the study had no involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Funding support:

This study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (P30 CA008748), R01 CA233899, P01CA221757, SPORE in Bladder Cancer P50CA221745 and Cycle for Survival. B.J. Guercio is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute via T32-CA009207, an Oncocyte Conquer Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award, and a Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network Young Investigator Award. E. Pietzak is supported by the NIH/NCI K12 Paul Calabresi Career Development Award for Clinical Oncology [K12 CA184746]. B. Weigelt is funded in part by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and Cycle for Survival grants.

Conflicts of interest

M.Y. Teo reports consulting/advisory role for Janssen Oncology and institutional research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, and Pharmacyclics. B.J. Guercio reports honoraria from Medscape and institutional research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Sanofi. E. Pietzak reports receiving honoraria from UpToDate, has served on the Scientific Advisory Board for Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co Inc., QED Therapeutics, Chugai Pharmaceuticals, and Steba Biotech, and receives research funding from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. B.H. Bochner reports consulting/advisory role for Genentech/Roche and Olympus; and honoraria from Genentech/Roche. A.C. Goh has served as a consultant for Medtronic. B. Weigelt reports ad hoc membership of the scientific advisory board of Repare Therapeutics, outside the submitted study. J. Sarungbam reports work as a consultant for Janssen Research & Development, LLC. S.A. Funt receives research funding from AstraZeneca and Genetech/Roche, has consulted for/received honoraria from Merck and has stock/equity ownership in Allogene Therapeutics, Urogen, Kronos Bio, Neogene Therapeutics, IconOVir, Vida Ventures, Doximity, and Ginkgo Bioworks. D.F. Bajorin reports personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb and Merck; consulting/advisory role for Merck, Dragonfly Therapeutics, Fidia Farmaceutici S.p.A., and Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation; Travel/accommodations/expenses from Merck; and institutional research funding from Novartis, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Astellas Pharma, and Seattle Genetics/Astellas. D.B. Solit reports personal fees from BridgeBio, Loxo/Lilly Oncology, Scorpion Therapeutics, Vividion Therapeutics, Pfizer, and FORE Therapeutics outside the submitted work. G. Iyer reports institutional research funding from Novartis, Bayer, Debiopharm, Seagen, Inc, Mirati Therapeutics, and Janssen; has served as a consultant or advisory role for Bayer, Janssen, Mirtai Therapeutics, Basilea, Flare Therapeutics, and Loxo/Lilly; has served as a speaker for Gilead Sciences and the Lynx Group; and has received personal fees from Personal fees from LOXO Oncology, Flare Therapeutics, Gilead, The Lynx Group, and DAVA Oncology. J.E. Rosenberg reports honoraria from Clinical Care Options, Medscape, Peerview, Physicans’ Education Resource, Research To Practice, UpToDate, and EMD-Serono; consulting or advisory role for Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BioClin Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Gilead/Immunomedics, Infinity, Janssen Oncology, Lilly, Merck, Mirati Therapeutics, Pfizer, EMD Serono, Pharmacyclics, Roche/Genentech, Seagen, and QED Therapeutics; institutional research funding from Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Genentech/Roche, Seagen, and QED Therapeutics; and an institutional patent regarding prediction of platinum sensitivity. H. Al-Ahmadie reports consulting/advisory roles for Bristol-Myers Squibb, EMD Serono, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Janssen Biotech, and PAIGE.AI. The remaining authors have no relevant conflicts of interest/ disclosures to report.

REFERENCES

- [1].Dores GM, Qubaiah O, Mody A, Ghabach B, Devesa SS. A population-based study of incidence and patient survival of small cell carcinoma in the United States, 1992-2010. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Naidoo J, Teo MY, Deady S, Comber H, Calvert P. Should patients with extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma receive prophylactic cranial irradiation? J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:1215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, Syed A, Middha S, Kim HR, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;23:703–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Forbes SA, Beare D, Boutselakis H, Bamford S, Bindal N, Tate J, et al. COSMIC: somatic cancer genetics at high-resolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D777–D83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chang MT, Asthana S, Gao SP, Lee BH, Chapman JS, Kandoth C, et al. Identifying recurrent mutations in cancer reveals widespread lineage diversity and mutational specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:155–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chakravarty D, Gao J, Phillips SM, Kundra R, Zhang H, Wang J, et al. OncoKB: A Precision Oncology Knowledge Base. JCO Precis Oncol. 2017;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chau C, Rimmer Frcr Y, Choudhury PhD A, Leaning Frcr D, Law A, Enting D, et al. Treatment Outcomes for Small Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder: Results From a UK Patient Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;110:1143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Luzzago S, Palumbo C, Rosiello G, Knipper S, Pecoraro A, Nazzani S, et al. Survival of Contemporary Patients With Non-metastatic Small-cell Carcinoma of Urinary Bladder, According to Alternative Treatment Modalities. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2020;18:e450–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cattrini C, Cerbone L, Rubagotti A, Zinoli L, Latocca MM, Messina C, et al. Prognostic Variables in Patients With Non-metastatic Small-cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Bladder: A Population-Based Study. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2019;17:e724–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jung K, Ghatalia P, Litwin S, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Greenberg RE, et al. Small-Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder: 20-Year Single-Institution Retrospective Review. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:e337–e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fischer-Valuck BW, Rao YJ, Henke LE, Rudra S, Hui C, Baumann BC, et al. Treatment Patterns and Survival Outcomes for Patients with Small Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4:900–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sroussi M, Elaidi R, Fléchon A, Lorcet M, Borchiellini D, Tardy MP, et al. Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Urinary Bladder: A Large, Retrospective Study From the French Genito-Urinary Tumor Group. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2020;18:295–303.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Lynch SP, Shen Y, Kamat A, Grossman HB, Shah JB, Millikan RE, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in small cell urothelial cancer improves pathologic downstaging and long-term outcomes: results from a retrospective study at the MD Anderson Cancer Center. Eur Urol. 2013;64:307–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ismaili N, Heudel PE, Elkarak F, Kaikani W, Bajard A, Ismaili M, et al. Outcome of recurrent and metastatic small cell carcinoma of the bladder. BMC Urol. 2009;9:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, Dogliotti L, Oliver T, Moore MJ, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3068–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chang MT, Penson A, Desai NB, Socci ND, Shen R, Seshan VE, et al. Small-Cell Carcinomas of the Bladder and Lung Are Characterized by a Convergent but Distinct Pathogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1965–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hoffman-Censits J, Choi W, Pal S, Trabulsi E, Kelly WK, Hahn NM, et al. Urothelial Cancers with Small Cell Variant Histology Have Confirmed High Tumor Mutational Burden, Frequent TP53 and RB Mutations, and a Unique Gene Expression Profile. Eur Urol Oncol. 2021;4:297–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li Q, Damish AW, Frazier Z, Liu D, Reznichenko E, Kamburov A, et al. Helicase Domain Mutations Confer Nucleotide Excision Repair Deficiency and Drive Cisplatin Sensitivity in Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:977–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Van Allen EM, Mouw KW, Kim P, Iyer G, Wagle N, Al-Ahmadie H, et al. Somatic ERCC2 mutations correlate with cisplatin sensitivity in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1140–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Teo MY, Bambury RM, Zabor EC, Jordan E, Al-Ahmadie H, Boyd ME, et al. DNA Damage Response and Repair Gene Alterations Are Associated with Improved Survival in Patients with Platinum-Treated Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3610–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu D, Plimack ER, Hoffman-Censits J, Garraway LA, Bellmunt J, Van Allen E, et al. Clinical Validation of Chemotherapy Response Biomarker ERCC2 in Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:1094–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, Fradet Y, Lee JL, Fong L, et al. Pembrolizumab as Second-Line Therapy for Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1015–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Powles T, Rosenberg JE, Sonpavde GP, Loriot Y, Durán I, Lee JL, et al. Enfortumab Vedotin in Previously Treated Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1125–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mandelkow T, Blessin NC, Lueerss E, Pott L, Simon R, Li W, et al. Immune Exclusion Is Frequent in Small-Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:2532518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Reis H, Serrette R, Posada J, Lu V, Chen YB, Gopalan A, et al. PD-L1 Expression in Urothelial Carcinoma With Predominant or Pure Variant Histology: Concordance Among 3 Commonly Used and Commercially Available Antibodies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:920–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sarfaty M, Whiting K, Teo MY, Lee CH, Peters V, Durocher J, et al. A phase II trial of durvalumab and tremelimumab in metastatic, non-urothelial carcinoma of the urinary tract. Cancer Med. 2021;10:1074–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McGregor BA, Campbell MT, Xie W, Farah S, Bilen MA, Schmidt AL, et al. Results of a multicenter, phase 2 study of nivolumab and ipilimumab for patients with advanced rare genitourinary malignancies. Cancer. 2021;127:840–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hoffman-Censits JH, Lombardo KA, Parimi V, Kamanda S, Choi W, Hahn NM, et al. Expression of Nectin-4 in Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma, in Morphologic Variants, and Nonurothelial Histotypes. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Study population. ACT = adjuvant chemotherapy; CRT = chemoradiotherapy; NAC = neoadjuvant chemotherapy; RC = radical cystectomy.

Supplemental Figure 2. Oncoprint of 47 cases of non-metastatic small cell carcinoma of the bladder, arranged via response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (x-axis).