PURPOSE:

The use of telemedicine expanded dramatically in March 2020 following the COVID-19 pandemic. We sought to assess oncologist perspectives on telemedicine's present and future roles (both phone and video) for patients with cancer.

METHODS:

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Electronic Health Record (EHR) Oncology Advisory Group formed a Workgroup to assess the state of oncology telemedicine and created a 20-question survey. NCCN EHR Oncology Advisory Group members e-mailed the survey to providers (surgical, hematology, gynecologic, medical, and radiation oncology physicians and clinicians) at their home institution.

RESULTS:

Providers (N = 1,038) from 26 institutions responded in Summer 2020. Telemedicine (phone and video) was compared with in-person visits across clinical scenarios (n = 766). For reviewing benign follow-up data, 88% reported video and 80% reported telephone were the same as or better than office visits. For establishing a personal connection with patients, 24% and 7% indicated video and telephone, respectively, were the same as or better than office visits. Ninety-three percent reported adverse outcomes attributable to telemedicine visits never or rarely occurred, whereas 6% indicated they occasionally occurred (n = 801). Respondents (n = 796) estimated 46% of postpandemic visits could be virtual, but challenges included (1) lack of patient access to technology, (2) inadequate clinical workflows to support telemedicine, and (3) insurance coverage uncertainty postpandemic.

CONCLUSION:

Telemedicine appears effective across a variety of clinical scenarios. Based on provider assessment, a substantial fraction of visits for patients with cancer could be effectively and safely conducted using telemedicine. These findings should influence regulatory and infrastructural decisions regarding telemedicine postpandemic for patients with cancer.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 public health emergency declaration posed special challenges for patients with cancer and their oncologists (hematology, stem-cell transplant, medical, radiation, surgical, and palliative care providers).1,2 Patients with cancer appear to be at higher risk for complications from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), although the root causes of this remain unclear.3-5 Patients with cancer are typically older, have pre-existing comorbidities, and may be immunocompromised from their cancer or cancer treatments. Consequently, health care systems used telemedicine to augment existing care while avoiding the risks of in-person contact.2,6 Telemedicine use for cancer care rose dramatically in mid-March 2020.2,7 This adaptation was facilitated by changes in reimbursement and regulations around provider licensing.8,9

Before March 2020, telemedicine was deployed in limited-use cases for patients with cancer, often to extend specialty expertise into rural areas.10-14 Thota et al14 reported that telemedicine sustainably lowered costs and increased the quality of health care for patients with cancer in rural Utah, using a real-time video-based program for patients located in a local clinic to visit with oncologists located at a tertiary medical center. However, the results of this structured program are difficult to apply to the national response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in which large numbers of oncologists and patients with cancer engaged in an unplanned telemedicine experiment without any formal training, established clinical workflows, or tested technical infrastructure, from both home and clinical locations.2 Ambulatory cancer patients range from healthy persons needing only periodic monitoring to severely immune-compromised patients requiring daily therapy. Oncologist outpatient activities range from discussion of reassuring results to conducting a physical examination, and obtaining a biopsy, etc.

Currently, most health care systems conduct telemedicine using a mixture of phone (audio only) and video (audio plus visual) visits; these modes have different strengths and weaknesses. Phone visits can be arranged without special instructions and do not require patients to have specialized technology or internet service. Video visits offer a richer experience for both patients and providers, which phone visits lack; communication cues can be assessed, and data (eg, computed tomography scans) can be viewed jointly via screen sharing. However, video visits are more complicated to arrange and conduct as they require broadband internet capacity and technology (camera and microphone) along with digital literacy (the ability to use and understand information from digital devices15) on the part of both patients and providers. Disparities in population abilities to conduct video visits have been described,16 and telemedicine data in nononcology settings such as genetics or pediatric visits suggest distinct differences between phone and video.13,17 Darcourt et al7 recently published data examining the experience of patients (n = 1,471) and providers (n =23) with video visits at a single institution during the first wave of the pandemic (March-April 2020). Patients and providers were largely satisfied with video visits within the context of pandemic care (92.6% and 65.2%, respectively), but this is limited by a single-institution experience and the early time point in the pandemic. However, relatively similar findings were reported by Patt et al18 with regards to patient and provider satisfaction. These analyses did not compare phone to video visits or query regarding future state.

Given the unknown impacts and relative merits of different types of telemedicine for patients with cancer, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) EHR Oncology Advisory Group formed a Telemedicine Workgroup to develop and conduct a survey to (1) understand the current experience with telemedicine from the oncologist perspective including both phone and video visits, (2) provide data to guide practice postpandemic, and (3) describe the facilitators and barriers for telemedicine when used for patients with cancer (eg, the oncology setting). This project was conceived of as a quality improvement project by the NCCN and was conducted as such and thus qualified as institutional review board–exempt.

METHODS

NCCN Telemedicine Workgroup

The NCCN EHR Oncology Advisory Group (Advisory Group) serves as a forum for NCCN members to share challenges and innovative practices regarding the optimization of oncology EHR systems. The Advisory Group formed a Workgroup in April 2020 to assess the current state of telemedicine for oncology. The Workgroup operated under the auspices of the Advisory Group and comprised representatives from six of the 30 NCCN Member Institutions, who have expertise in EHR optimization including telemedicine.

Survey Development

The Workgroup developed a survey designed to assess oncologist perspectives on their telemedicine experience in caring for patients with cancer at NCCN Member Institutions. The complete 20-question survey (14 multiple choice, multiselect, drop-down depending on branching logic; and six free text) and draft invitation are available in the Data Supplement (online only).

Survey Distribution

To elicit the perspective of a broad spectrum of oncologists, we requested that each NCCN EHR Advisory Group Member distribute a survey invitation to eligible providers at their home institution. In July 2020, Workgroup members contacted an Advisory Group Member from each NCCN Member Institution to solicit participation. Each Member was responsible for distributing the survey to local providers or identifying the appropriate person at their institution to do so. A standard invitation e-mail was shared with each member, which included a hyperlink to the survey (hosted on SurveyMonkey). The survey was open from July 15 to August 21, 2020. The final survey responses were reviewed by the Advisory Group on October 12, 2020, and the Group approved these results for publication.

Analysis Plan

Means, standard deviations, and proportions were calculated for continuous and categorical variables (Table 1). Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between how favorably oncologists view using optional telemedicine visits and oncologist characteristics (years of experience postfellowship, comfort level with technology, specialty, and sex). Tukey's honestly significant difference test and one-way analysis of variance were used to compare the difference between the percentage of patients who could reasonably be seen by video and specialty. Data analyses were performed using R statistical software version R 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P value of .05 was considered statistically significant.

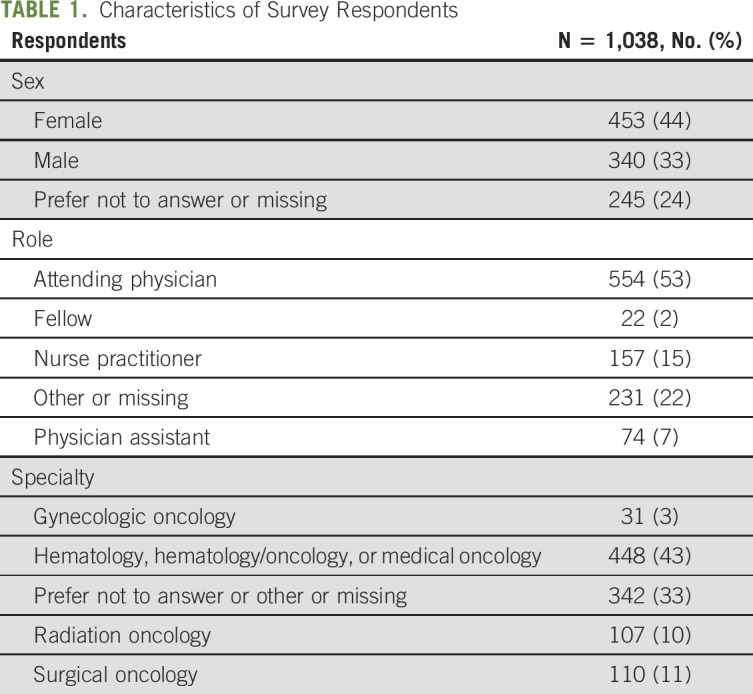

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Survey Respondents

RESULTS

Respondent Characteristics

Of the 30 Member Institutions, 26 (87%) are represented in the responses. The number of respondents per center is available in the Data Supplement. A total of 1,038 individuals responded, with more than three quarters completing the demographic questions at the end. Table 1 shows the respondent characteristics.

Telemedicine Experience

Most respondents (N = 1,038) had no telemedicine experience before the pandemic (81%) but by the time of the survey, 84% had participated in both phone- and video-based visits. Common reasons for not having conducted any telemedicine (n = 66) visits (either phone or video) included patient lack of technology, inefficient workflows, and need for physical examination. Respondents (n = 826) indicated that whether a telemedicine visit occurred was largely based on provider discretion (88%) and patient preference (81%); these were not mutually exclusive categories. For phone visits, 92% of respondents (n = 726) who conducted them did 1-10 visits per week and 8% did 11 or more. For video visits, 73% of those who conducted them (n = 781) did 1-10 visits per week and 27% did 11 or more.

Phone- and Video-Based Visits Compared With In-Person Visits

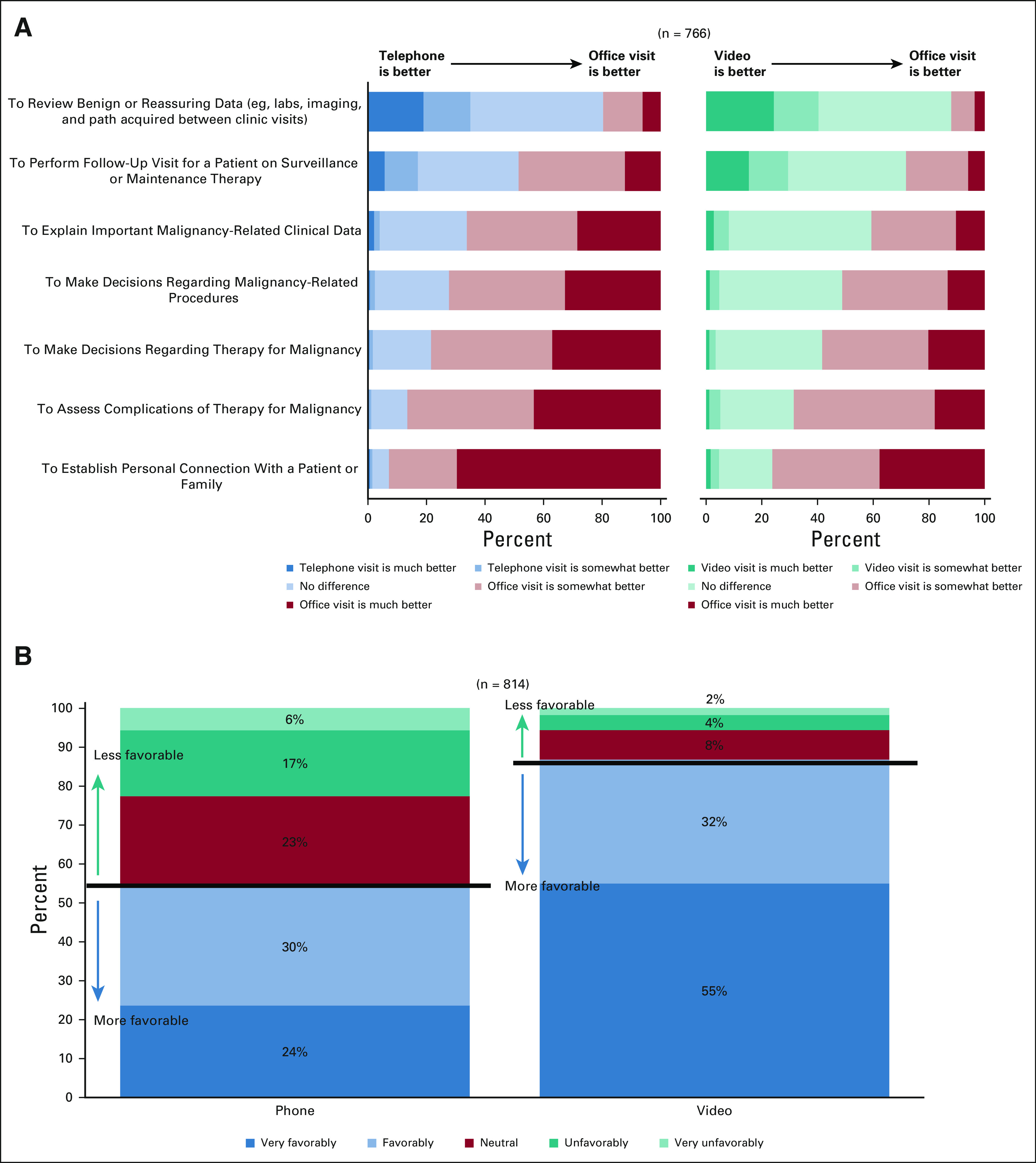

Respondents (n = 766) were asked to compare telemedicine (either phone or video) to an in-person office visit for a variety of clinical scenarios typically encountered (Fig 1A). Phone and video formats were not directly compared with each other in this question. For scenarios intended to review benign or reassuring data, telemedicine visits were considered as good as or better than in-person visits. By contrast, scenarios requiring assessment, decision making, or establishing an emotional connection generated responses favoring in-person visits, whereas intermediate complexity scenarios (eg, make decisions regarding procedures) yielded results in between these extremes. Phone and video formats tracked similarly, although video outperformed phone in every scenario.

FIG 1.

(A) Oncologist perspective on how telemedicine visits (both phone and video) compared with in-person office visits for particular tasks commonly accomplished during visits. (B) Favorability of using optional phone and video visits postpandemic for appropriate patients, assuming reimbursement and that providers can select phone or video format and visit length.

Telemedicine Outcomes

Respondents (n = 733) were asked how often telemedicine visits resulted in an urgent in-person visit, unplanned diagnostic study, or medication change. Greater than two thirds of respondents indicated that a telemedicine visit generated an urgent in-person visit rarely or never; roughly a quarter (27% for phone and 24% for video) said this was an occasional occurrence. Unplanned diagnostic studies and medication changes were outcomes reported with greater frequency; however, the survey did not query whether the action triggered ultimately proved necessary or was driven by the uncertainty of telemedicine format compared with an in-person format. There was little difference between phone and video visits; free-text comments (n = 43) noted that unplanned diagnostic studies and medication changes were also common during in-person visits. Respondents (n = 801) were asked how often they perceived an adverse outcome as arising because of a telemedicine visit versus an in-person visit. This was an uncommon occurrence (93% reported never or rarely, 6% occasionally, and < 1% frequently).

Postpandemic Teleoncology Utilization

Respondents (n = 814) were asked “How favorably do you view using OPTIONAL telephone and video visits, post pandemic for appropriate patients, assuming reimbursement and that providers can select telephone or video format and visit length?” with separate responses for both phone and video on a 5-point Likert scale (very favorably; favorably; neutral; unfavorably; and very unfavorably). For phone, 54% replied very favorably or favorably versus 46% neutral, unfavorably, or very unfavorably; for video, 87% replied very favorably or favorably versus 13% neutral, unfavorably, or very unfavorably (Fig 1B). A logistic regression was used to determine whether there was a relationship between self-reported respondent characteristics and views on telemedicine. Comparing those responding very favorably or favorably to those responding neutral, unfavorably, or very unfavorably according to years in practice, sex, comfort with technology (very comfortable or comfortable v neutral v somewhat uncomfortable), and specialty (hematology or medical oncology, gynecologic oncology, surgical oncology, radiation oncology, other or no reply) demonstrated no relationship between respondent characteristics and the favorability of using telemedicine.

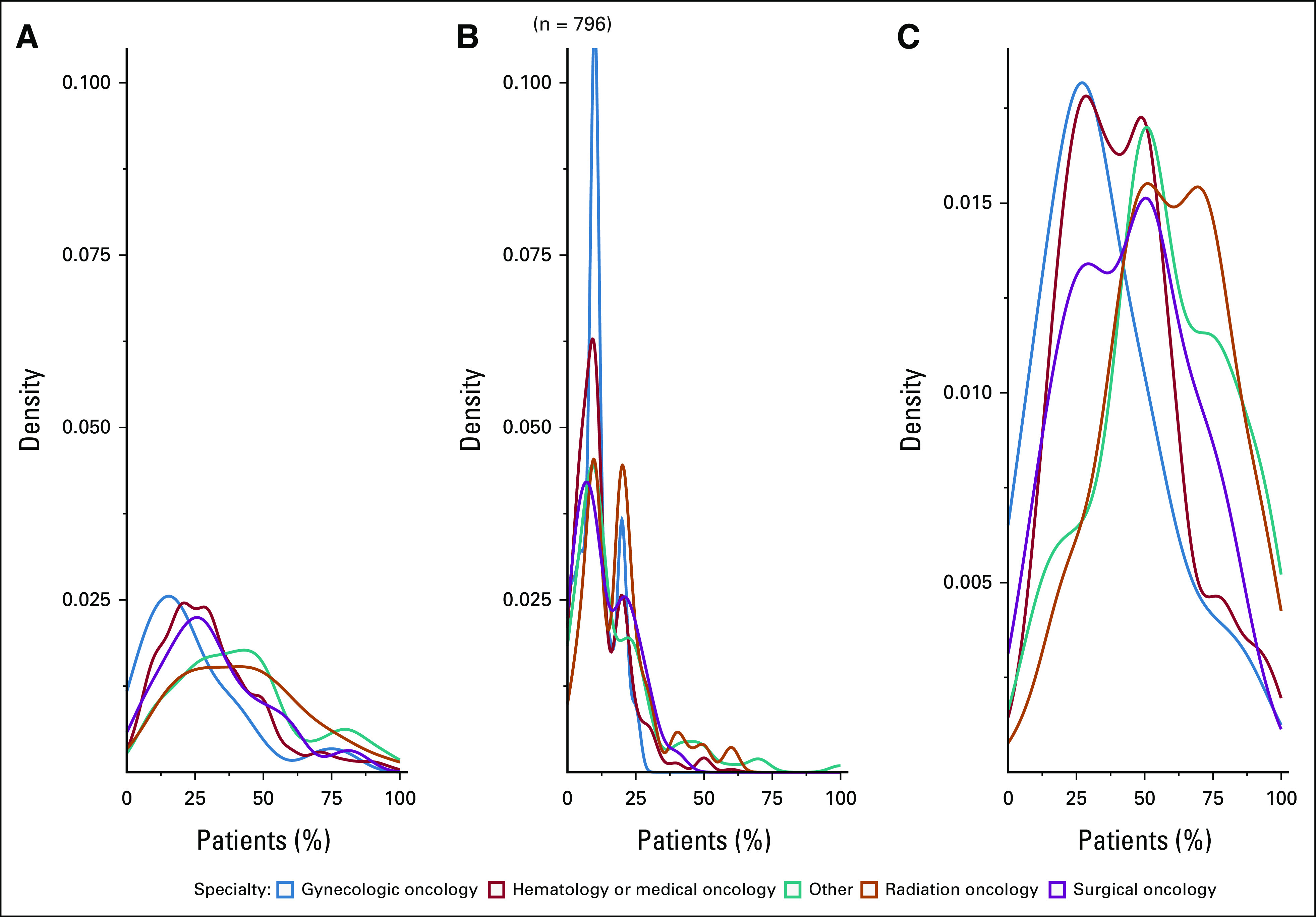

Respondents (n = 796) were asked, “Absent any financial implications, approximately what percentage of your patients could reasonably be seen via telemedicine versus in-person visits after pandemic resolution?” with the survey requiring a percentage value for phone, video, and in-person totaling 100%. The averaged response across all respondents was 54% in-person visits, 33% video visits, and 13% phone visits. The results from these analyses showed that this differed by specialty. Figure 2 shows the distributions by specialty. A one-way analysis of variance showed a significant difference (F(4, 650) = 15.75, P < .001) between specialties for patients who could be seen by telemedicine. The Tukey's honestly significant difference test comparing the means of different groups showed radiation oncology was significantly more likely to have indicated telemedicine versus gynecologic oncology (mean difference in proportion, d = 23.6%; 95% CI, 9.6 to 37.6), hematology or medical oncology (d = 15.9%; 95% CI, 8.3 to 23.5%), and surgical oncology (d = 13.%; 95% CI, 4.1 to 23.3).

FIG 2.

Density plots showing the distribution of the estimated percentage of patients with cancer who could be seen by oncologist specialty. (A) Video. (B) Phone. (C) Telemedicine (phone or video).

Free-Text Responses

Many respondents entered detailed information into the free-text comments. Key themes appeared in response to the free-text questions “What would make you more willing to conduct virtual visits?” (n = 620 responses), “What would make you less willing to conduct virtual visits?” (n = 540 responses), and “Is there anything else you would like to share about virtual visits?” (n = 292 responses). Reimbursement appeared as a key future driver for postpandemic telemedicine. Lack of efficiency and emotional connection were cited as barriers. Responses (Data Supplement) displayed a range of experiences with telemedicine:

“My overall experience doing virtual visits has been markedly positive. [Patients] tell me how much they love not having to deal with parking headaches, costs, valet issues, lab wait times, traffic, long drives, overnight stays before/after appointments, etc.”

“Significant concern [that] we are not adequately caring for … cancer patients with no physical exam”

DISCUSSION

Telemedicine expanded rapidly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as health care systems sought to minimize in-person contact. Patients with cancer represent a unique population that may be at higher risk for complications from SARS-CoV2, but for whom the risks and benefits of telemedicine are poorly understood. The NCCN Advisory Group sought to better understand oncologists' perspectives on current and future practice of telemedicine for patients with cancer. This survey represents the largest such assessment of oncologist perspectives on the use of telemedicine17 and includes key findings as the oncology community contemplates how to deploy telemedicine postpandemic. One key finding is that telemedicine seems safe for appropriately selected patients in the oncology setting; serious adverse events attributable to the use of telemedicine were reported as uncommon. Of note, respondents reported that oncologist and patient preference largely dictated who participated in telemedicine. If these adverse events were influenced by patient hesitancy to enter the clinic, it is plausible that their occurrence would be lower in the postpandemic period with telemedicine utilization not driven by physical distancing requirements.

Another key finding is that telemedicine performed well for uncomplicated clinical scenarios but underperformed versus in-person visits as care complexity increased. Within this continuum, respondents preferred video visits to phone visits for all hypothetical clinical scenarios. The free-text responses offered clues regarding what drove this preference. Video visits “provide a window into the patient's life—you visibly see the environment they live in and possibly the challenges of day to day,” “video visits provide a better interpersonal connection because of not having to wear masks—ability to smile, appreciate facial expressions both good and bad,” or “Telephone visits are much more limiting than the video visits because of the inability to gauge expression which can often times provide clues about level of understanding as well as distress.” Our third and most consequential finding is that oncologists indicated telemedicine has utility in oncology care and that telemedicine would be an appropriate mechanism for nearly half (46%) of the patient visits postpandemic.

Strengths of this analysis include the large number of respondents from geographic and economically diverse areas across the United States—to our knowledge, this is one of the largest and broadest such surveys in oncology.13 The high completion rate suggests a high level of motivation and interest on this topic, supported by the many lengthy and thoughtful comments in response to the free-text questions (Data Supplement). The survey timing in July 2020 means the respondents were relatively mature technically and organizationally from a telemedicine perspective. Limitations include that NCCN Member Institutions represent US academic tertiary care cancer centers. Thus, our results may not reflect the perspectives of community or non-US oncologists. Furthermore, our reliance on an Advisory Group Member to forward the survey complicates the calculation of a response rate. Institutional listservs were heterogeneous and each institution differed (eg, some included fellows, others included providers outside the target audience [eg, geneticists], and others excluded offsite providers [eg, radiation and surgical oncology]). Nonetheless, all specialties were well represented across multiple institutions and no single institution represented > 31% of the responses for a specific specialty. These listservs included subspecialty providers seeing a unique class of patients for which telemedicine was well suited (eg, benign hematology) or inappropriate (eg, postoperative surgery).Another limitation is the time frame of the survey (July 15-August 21, 2020). The results may not reflect current engagement and attitudes about telemedicine.

It seems unlikely that the telemedicine genie can be forced back into the bottle postpandemic, given that substantial numbers of providers and patients with cancer have had favorable telemedicine experiences. Our survey suggests that telemedicine is viewed as safe and effective for cancer care within certain clinical scenarios. As such, it would be appropriate for regulatory agencies, in conjunction with providers and insurers, to begin exploring reimbursement and licensure for postpandemic care. Reimbursement decisions should consider that a substantial number of providers feel there is a real, although small, role for phone visits—possibly because of the inherent ease for patients and providers “My experience is that patients are more relaxed and easy to talk with when they are at home and contacted by phone. Even patients I have known for years seem very different in their demeanor when talking with them by phone from a telephone visit conducted from home.” Guidelines should clarify or contemplate rules around conversion from a telemedicine to an in-person encounter as some percent of telemedicine visits will need to be converted to an in-person examination. Triage workflows need to be developed for the appropriateness of telemedicine. Health care systems need to contemplate clinical workflow integration and patient support issues. For instance, how do we prospectively integrate telemedicine visits into clinical workflows based on patient or cancer characteristics? Free-text comments noted the struggle to intersperse telemedicine with in-person visits. We may need to have clearer messaging to patients about the utility or role for phone versus video visits, as well as training or education for patients about when each type of visit is likely to be appropriate. Vendors offering video technology should consider how to enhance the experience by facilitating screen sharing to permit review of scans, being able to sketch or take notes for patients, and facilitating multiparty participation so that caregivers and interpreters can join. Survey free-text comments strongly supported the need for better resourcing patients and providers.

We must also carefully consider the patient perspective and the risk of inadvertently widening disparities. Our survey does not directly speak to the perspective of patients with cancer. However, our respondents (who work with such patients daily) expressed concerns that some populations might be left behind by an increased reliance on telemedicine: “We need to address the barriers of widespread broadband and device access for patients” and “I see patients with [head and neck cancer], many of them have limited resources, limited technological literacy, and many are nonverbal because of their disease” and “Many of my older patients lacked the appropriate telephones or knowledge to set up a telehealth video visit.” Existing literature finds disparities with respect to patient portals19,20 (which may complicate telemedicine disparities as some vendors rely on portal accounts to perform video visits) and with regards to access to the needed technology, digital literacy, or broadband capacity.16,21,22 Telemedicine solutions should account for varying levels of digital literacy and reduce potential barriers by enabling patients to join visits using multiple routes (portal, e-mail, and SMS).

In conclusion, our results demonstrate an ongoing role for telemedicine in oncology. Clinical workflows and best practices cannot stabilize until regulatory, licensing, and reimbursement policies are addressed and should be re-examined as these policies become clearer and pandemic pressures ease. A fuller understanding of the patient and caregiver perspective is warranted and ongoing.23,24

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the following: the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Member Institutions and the NCCN EHR Oncology Advisory Group, which is composed of clinical leaders who oversee the optimization of EHR systems at their respective NCCN Member Institutions.

Amye J. Tevaarwerk

Other Relationship: Epic Systems

Travis Osterman

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Infostratix

Consulting or Advisory Role: eHealth, AstraZeneca, Outcomes Insights, Biodesix, MDoutlook, GenomOncology, Cota Healthcare, Flagship Biosciences

Research Funding: GE Healthcare, Microsoft, IBM Watson Health

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GE Healthcare

Waddah Arafat

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Myovant Sciences

Research Funding: Seattle Genetics/Astellas

Jessica Sugalski

Employment: Archimedic

Leadership: Archimedic

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Archimedic

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: My spouse holds several patents related to his role as President of Archimedic. Companies include Cooper Surgical, ZSX Medical, and Becton Dickinson

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented as an abstract and oral presentation at the virtual National Comprehensive Cancer Network annual meeting, March 20, 2021.

SUPPORT

A.J.T. was supported by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA014520.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Amye J. Tevaarwerk, Travis Osterman, Waddah Arafat, Jeffrey Smerage, Fernanda C. G. Polubriaginof, Tricia Heinrichs, Jessica Sugalski, Daniel B. Martin

Collection and assembly of data: Amye J. Tevaarwerk, Travis Osterman, Waddah Arafat, Jeffrey Smerage, Fernanda C. G. Polubriaginof, Tricia Heinrichs, Jessica Sugalski, Daniel B. Martin

Data analysis and interpretation: Amye J. Tevaarwerk, Thevaa Chandereng, Travis Osterman, Waddah Arafat, Jeffrey Smerage, Fernanda C. G. Polubriaginof, Tricia Heinrichs, Jessica Sugalski, Daniel B. Martin

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Oncologist Perspectives on Telemedicine for Patients With Cancer: A National Comprehensive Cancer Network Survey

The following represents disclosure information provided by the authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Amye J. Tevaarwerk

Other Relationship: Epic Systems

Travis Osterman

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Infostratix

Consulting or Advisory Role: eHealth, AstraZeneca, Outcomes Insights, Biodesix, MDoutlook, GenomOncology, Cota Healthcare, Flagship Biosciences

Research Funding: GE Healthcare, Microsoft, IBM Watson Health

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GE Healthcare

Waddah Arafat

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Myovant Sciences

Research Funding: Seattle Genetics/Astellas

Jessica Sugalski

Employment: Archimedic

Leadership: Archimedic

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Archimedic

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: My spouse holds several patents related to his role as President of Archimedic. Companies include Cooper Surgical, ZSX Medical, and Becton Dickinson

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services : https://www.phe.gov/emergency/news/healthactions/phe/Pages/2019-nCoV.aspx [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Liu R, Sundaresan T, Reed ME, et al. : Telehealth in oncology during the COVID-19 outbreak: Bringing the house call back virtually. JCO Oncol Pract 16:289-293, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. : Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 21:335-337, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood WA, Neuberg DS, Thompson JC, et al. : Outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies and COVID-19: A report from the ASH Research Collaborative Data Hub. Blood Adv 4:5966-5975, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarifkar P, Kamath A, Robinson C, et al. : Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 33:e180-e191, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehrotra A, Ray K, Brockmeyer D, et al. : Rapidly converting to “virtual practices”: Outpatient care in the era of Covid-19. NEJM Catalyst Innov Care Deliv, 1(2) 2020. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0091 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darcourt JG, Aparicio K, Dorsey PM, et al. : Analysis of the implementation of telehealth visits for care of patients with cancer in Houston during the COVID-19 pandemic. JCO Oncol Pract 17:e36-e43, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.https://www.ahip.org/health-insurance-providersrespond- AsHIPHIPRtCC-, to-coronavirus-covid-19/

- 9.https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicaretelemedicine- CfMaMSMthcpfs, health-care-provider-fact-sheet

- 10.Barsom EZ, Jansen M, Tanis PJ, et al. : Video consultation during follow up care: Effect on quality of care and patient- and provider attitude in patients with colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc 35:1278-1287, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mooi JK, Whop LJ, Valery PC, et al. : Teleoncology for indigenous patients: The responses of patients and health workers. Aust J Rural Health 20:265-269, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma JJ, Gross G, Sharma P: Extending oncology clinical services to rural areas of Texas via teleoncology. JCO Oncol Pract 8:68, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viers BR, Lightner DJ, Rivera ME, et al. : Efficiency, satisfaction, and costs for remote video visits following radical prostatectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Eur Urol 68:729-735, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thota R, Gill DM, Brant JL, et al. : Telehealth is a sustainable population health strategy to lower costs and increase quality of health care in rural Utah. JCO Oncol Pract 16:e557-e562, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manganello J, Gerstner G, Pergolino K, et al. : The relationship of health literacy with use of digital technology for health information: Implications for public health practice. J Public Health Manag Pract 23:380-387, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khairat S, Haithcoat T, Liu S, et al. : Advancing health equity and access using telemedicine: A geospatial assessment. J Am Med Inform Assoc 26:796-805, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lion KC, Brown JC, Ebel BE, et al. : Effect of telephone vs video interpretation on parent comprehension, communication, and utilization in the pediatric emergency department: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 169:1117-1125, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patt DA, Wilfong L, Toth S, et al. : Telemedicine in community cancer care: How technology helps patients with cancer navigate a pandemic. JCO Oncol Pract 17:e11-e15, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerber DE, Laccetti AL, Chen B, et al. : Predictors and intensity of online access to electronic medical records among patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract 10:e307-e312, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pho KK, Lu R, Gates S, et al. : Mobile device applications for electronic patient portals in oncology. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 3:1-8, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell UA, Chebli PG, Ruggiero L, et al. : The digital divide in health-related technology use: The significance of race/ethnicity. Gerontologist 59:6-14, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nouri S, Khoong EC, Lyles CR, et al. : Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the Covid-19 pandemic. NEJM Catalyst Innov Care Deliv 1(3), 2020. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0123 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas SL, Mazanec P, Lipson AR, et al. : Videoconference intervention for distance caregivers of patients with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. JCO Oncol Pract 17:e26-e35, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang CY, El-Kouri NT, Elliot D, et al. : Telehealth for cancer care in veterans: Opportunities and challenges revealed by COVID. JCO Oncol Pract 17:22-29, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]