PURPOSE:

Palliative care (PC) improves outcomes in advanced cancer, and guidelines recommend early outpatient referral. However, many PC teams see more inpatient than outpatient consults. We conducted a retrospective study of hospitalized patients with cancer to quantify exposure to inpatient and outpatient PC and describe associations between PC and end-of-life (EOL) quality measures.

METHODS:

We identified all decedents admitted to an inpatient oncology unit in 1 year (October 1, 2017-September 30, 2018) and abstracted hospitalization statistics, inpatient and outpatient PC visits, and EOL outcomes. Descriptive statistics, univariate tests, and multivariate analysis evaluated associations between PC and patient outcomes.

RESULTS:

In total, 522 decedents were identified. 50% saw PC; only 21% had an outpatient PC visit. Decedents seen by PC were more likely to enroll in hospice (78% v 44%; P < .001), have do-not-resuscitate status (87% v 55%; P < .001), have advance care planning documents (53% v 31%; P < .001), and die at home or inpatient hospice instead of in hospital (67% v 40%; P < .01). Decedents seen by PC had longer hospital length-of-stay (LOS; 8.4 v 7.0 days; P = .03), but this association reversed for decedents seen by outpatient PC (6.3 v 8.3 days; P < .001), who also had longer hospice LOS (46.5 v 27.1 days; P < .01) and less EOL intensive care (6% v 15%; P < .05).

CONCLUSION:

PC was associated with significantly more hospice utilization and advance care planning. Patients seen specifically by outpatient PC had shorter hospital LOS and longer hospice LOS. These findings suggest different effects of inpatient and outpatient PC, underscoring the importance of robust outpatient PC.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, randomized controlled trials have shown that early delivery of specialized palliative care (PC) improves outcomes for patients with advanced cancer, including improved quality of life (QOL), reduced symptom burden, less patient and caregiver distress, and longer survival.1-5 ASCO recommends that patients with advanced cancer, whether inpatient or outpatient, should receive dedicated PC services, early in the disease course, concurrent with active treatment.6 However, despite the growth of PC across the United States, early, robust, and longitudinal integration of PC into cancer care remains aspiration rather than reality at many hospitals. National Cancer Institute–designated cancer centers have expanded outpatient PC since 2009, but inpatient consultation volumes remain significantly larger than outpatient volumes as of 2018.7 As such, it is critical to understand the delivery process and clinical impact of PC consultation in the inpatient oncology setting, which differs from the interventions supported by earlier trials in the outpatient setting.

A number of studies have examined the effects of inpatient PC consultation on patients with cancer. These suggest a variety of benefits from inpatient PC, including reduced symptom severity,8-11 increased disease awareness and election of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) status,12-14 and decreased health care costs.15,16 Unfortunately, this body of evidence is heterogeneous in terms of study design and quality, being largely composed of nonrandomized and uncontrolled studies17; two notable exceptions are recent randomized trials showing that inpatient PC, compared with usual care alone, improves QOL in patients with hematologic malignancies.18,19 On the basis of these studies, individual centers have begun to implement new models of care with the goal of better integrating PC into the inpatient oncology setting. These include clinical triggers to facilitate or encourage PC consultation20,21 and a corounding (as opposed to consultative) role for PC clinicians.22

Despite these innovations, gaps in the literature remain. Notably, although a variety of benefits have been attributed to inpatient and outpatient PC individually, the relative impact of inpatient v outpatient PC on outcomes is not as well described. This is important because the two settings are characterized by a marked difference in care delivery and process: outpatient PC visits often transpire as a result of referral earlier in the disease course, enabling longitudinal building of rapport, patient and family coping skills, and disease understanding; whereas inpatient PC teams are often involved later in the disease course, usually providing assistance with acute symptom management and decision making in the context of hospitalization or clinical crisis.23 To address this gap in the evidence base, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of decedents with cancer who were hospitalized during 1 year in our center's inpatient oncology unit. Our goals were to describe which and how many patients were seen by inpatient and outpatient PC before death, to evaluate associations between PC exposure and end-of-life (EOL) quality measures, and to identify areas of differential impact of inpatient and outpatient PC on EOL outcomes and health care utilization.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a retrospective, observational study using pre-existing data from the medical record to examine EOL outcomes in decedents with cancer who were hospitalized in the final 2 years of life, and explore associations between EOL outcomes and inpatient v outpatient PC exposure. Outcomes and analyses were post hoc and exploratory in nature. This study was reviewed and approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

The subset of hospitalized decedents (as opposed to all decedents from the cancer center) was chosen for two specific reasons: (1) to describe a cohort with higher severity of illness and greater health care utilization, where EOL care processes would be abundantly documented, and (2) to describe a cohort that is less well described in the PC literature, which has often centered on the longitudinal experiences of patients in outpatient models of PC.

Data Collection

We identified all patients admitted to our cancer center's inpatient oncology unit during a single fiscal year (October 1, 2017, through September 30, 2018). Through targeted chart review, multiple study authors (J.C.Y., A.R.U., and R.J.B.) abstracted patient demographic information, hospitalization statistics, and number of inpatient and/or outpatient PC visits for each patient. Inpatient and outpatient PC exposure were treated as separate independent variables.

Decedents were identified through chart review and publicly available obituaries. For decedents, EOL outcomes, many of which correspond to quality measures published by ASCO's Quality Outcomes Practice Initiative, were captured in detail. These included hospice utilization, presence of advance care planning (ACP) documents in the electronic medical record, code status before death, pain and dyspnea management in the final two clinical encounters before death, and rates of systemic cancer therapy in the final 14 days of life and intensive care unit (ICU) utilization in the final 30 days of life. Hospital and hospice lengths-of-stay (LOS) were also documented. Health care utilization at other centers (including outside hospital admissions, ICU utilization, and PC utilization) was not able to be abstracted from the medical record.

PC Operations

At our center, during the study timeframe, oncology patients were referred to PC services at the discretion of a consulting physician (ie, an inpatient oncology service attending or longitudinal outpatient oncologist), as is routine in most centers across the United States. No automatic referral criteria or consult triggers were in use at this time. The inpatient and outpatient PC services were staffed by a hospital-based interdisciplinary team consisting of physicians (4.4 total clinical full-time equivalents or cFTE), nurse practitioners (1.3 cFTE), and social workers (1.3 cFTE), all of whom had specialty PC certification in their respective disciplines. PC consultations in both settings involved comprehensive symptom assessment and management; support of coping and prognostic understanding; exploration of patients' goals and values; and when warranted by the clinical situation, assistance with medical decision making and identification of EOL care preferences. Inpatient PC consults were seen on weekdays, with approximately 1,200 new patients seen over the year (average daily service census of 20-30 patients), and outpatient PC visits were seen two half-days per week, with approximately 800 total visits (250 new patients) over the year.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were used to summarize the results, and t-tests and chi-square tests were used to evaluate associations between PC exposure and continuous or categorical outcomes, respectively. We used generalized estimating equations to estimate means and standard deviations of continuous measures while accounting for multiple admissions per patient. Multivariate analysis of hospital LOS was done using generalized estimating equations to estimate change in LOS while accounting for age, sex, race and ethnicity, cancer type, and repeated measures among patients. To adjust for multiple testing, we used a Bonferroni correction for all univariate analyses: the desired α of 0.05 was divided by 17 (the total number of outcome comparisons), yielding a statistical significance level of < .003 for two-sided P values. All analyses were performed using Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

In 1 year, 899 unique patients were hospitalized; 57 were medical or surgical patients without an oncologic diagnosis and were excluded. Of the remaining 842 patients, 522 were deceased by the study cutoff date (October 1, 2020) and were included in the following analyses. Of the 522 decedents, 50% (n = 259) had some exposure to PC before death. Of these, most had only inpatient PC consultation; only 21% of all decedents (n = 111) had an outpatient PC visit before death. Thirteen percent of decedents (n = 68) were seen by both inpatient and outpatient PC. Patients seen by inpatient PC had a median of five inpatient visits (interquartile range [IQR]: 3-8 visits), with the first visit occurring a median of 45 days before death (IQR: 16-121 days). Patients seen by outpatient PC had a median of two clinic visits (IQR: 1-4 visits), with their first visit occurring a median of 223 days before death (IQR: 96-458 days).

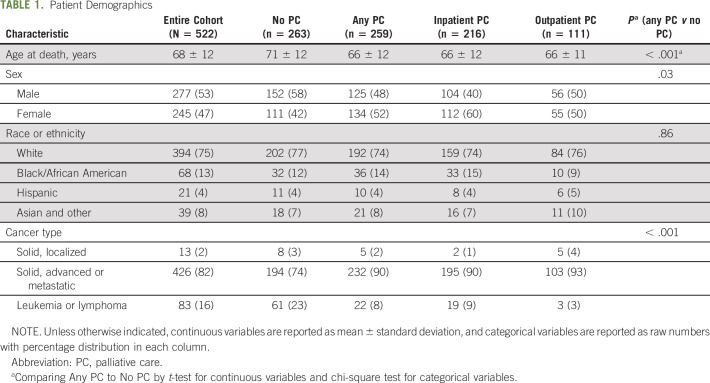

In terms of patient demographics across the cohort (Table 1), the median age at death was 69 years (range: 22-93 years), 47% were women, 25% were from self-identified racial or ethnic minority groups, and 82% had advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Compared with patients without PC exposure, decedents seen by PC were younger at time of death (66 v 71 years; P < .001), more likely to be female (52% v 42%; P = .03), and more likely to have advanced or metastatic solid disease (90% v 74%; P < .001) as opposed to localized disease, leukemias, or lymphomas. There was no difference in distribution of self-reported race or ethnicity between the PC and non-PC groups.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics

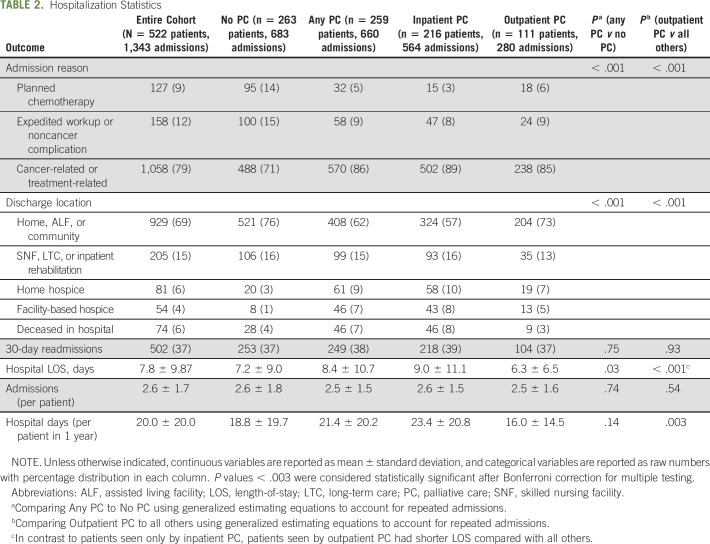

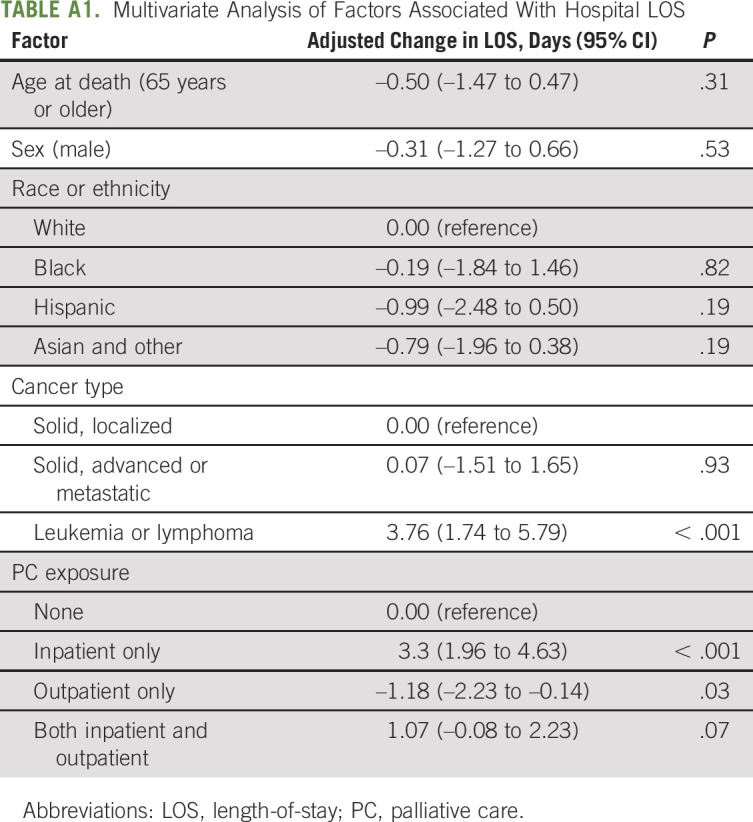

In terms of hospitalization statistics (Table 2), the most common reasons for admission were cancer- or treatment-related complications (including infections, uncontrolled symptoms, and other problems related to disease progression). This was especially true for patients seen by PC, who had significantly fewer admissions for other reasons (non–cancer-related issues, planned chemotherapy, or expedited medical workup without complication) than their non-PC counterparts (14% v 29%; P < .001). Patients seen by PC had longer average hospital LOS (8.4 v 7.2 days; P = .03), but on subgroup analysis, this difference was because of longer LOS among patients seen only by inpatient PC. Patients with outpatient PC exposure had the reverse association (hospital LOS 6.3 days v 8.2 days; P < .001), as well as fewer mean hospitalized days over the entire year (16.0 v 21.2 days; P = .003) compared with patients never seen by outpatient PC. This association remained significant in a multivariate analysis of factors associated with LOS (Appendix Table A1, online only); controlling for patient demographics and cancer type, any exposure to outpatient PC conferred an adjusted change of –1.18 days in mean LOS per hospital admission. Between groups, there was no difference in the rate of 30-day readmissions, which was high across the entire cohort (37% of admissions).

TABLE 2.

Hospitalization Statistics

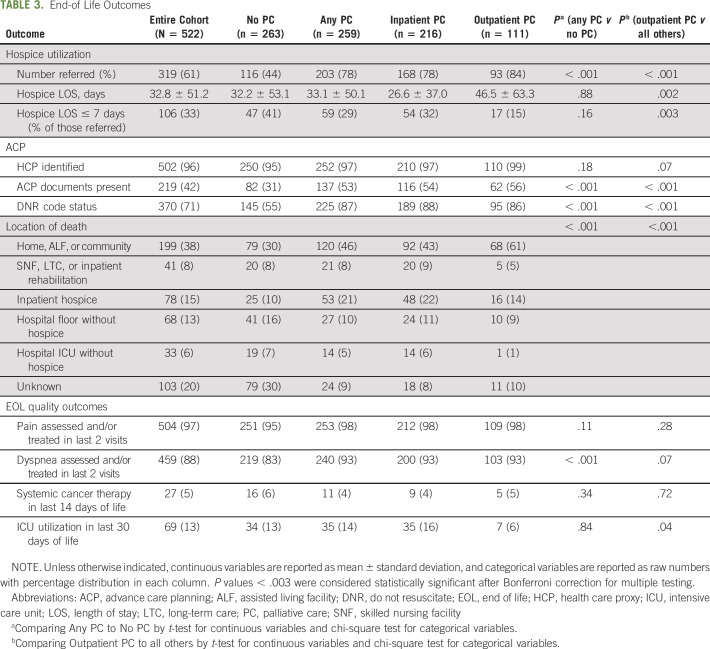

In terms of EOL outcomes (Table 3), there was a high rate of hospice utilization across the entire cohort (61%). Despite this, patients who had any PC exposure before death were significantly more likely to enroll with hospice compared with those who had no PC exposure (78% v 44%; P < .001). Mean hospice LOS did not differ between any PC exposure v none, but again, subgroup analysis showed that patients seen by outpatient PC had significantly longer hospice LOS compared with all others (46.5 v 27.1 days; P = .002). PC exposure was also significantly associated with greater availability of ACP forms in the electronic medical record (53% v 31%; P < .001) and greater frequency of DNR code status at time of death (87% v 55%; P < .001). Patients seen by PC were more likely to die at home or in inpatient hospice, rather than on a hospital floor or ICU without hospice enrollment, although interpretation of this outcome is limited by missing or unknown locations of death in 20% of the cohort. Finally, PC exposure was associated with more frequent assessment and/or treatment of dyspnea in the last two documented clinical encounters before death (93% v 83%; P < .001). There was no difference in frequency of systemic cancer therapy in the final 14 days or life. Patients seen by outpatient PC were less likely to use the ICU in the final 30 days of life compared with all others, though this difference was not statistically significant (6% v 15%; P = .046).

TABLE 3.

End-of Life Outcomes

DISCUSSION

In this observational study of decedents who were hospitalized on an inpatient oncology unit in the last 2 years of life, PC exposure was associated with several improvements in EOL care quality, including increased hospice utilization, increased documentation of ACP, more consistent symptom assessment, and fewer in-hospital deaths. Although concordance of care with patient and family goals and values is difficult to quantify in retrospect, the fact that PC exposure was strongly associated with multiple changes in EOL care processes (more hospice enrollment, more ACP and DNR code statuses, and different locations of death) suggests that PC involvement may have led to improved identification of patient and family care preferences. These findings are especially relevant because of the high illness severity within this cohort, as evidenced by the predominance of advanced or metastatic disease, the frequency of admissions for disease-related complications, the high rate of 30-day readmissions across all groups, and the high rate of mortality within 2 years of the study timeframe (n = 522 of 842; 62%). These indicators affirm that the inpatient oncology population is one with significant PC needs.

Furthermore, in this study, we uniquely described differences in care outcomes associated with inpatient PC, outpatient PC, and no PC at all. The subgroup of patients who encountered the outpatient PC team had shorter hospital LOS, fewer hospitalized days over the study timeframe, longer hospice LOS, and less ICU utilization at EOL; these outcomes were not associated with inpatient PC alone. These differences speak to the complexity and challenge of providing high-quality PC: to successfully affect patient outcomes, PC teams must develop rapport and familiarity with patients and families; tend to an array of physical and nonphysical causes of suffering; and build disease understanding and coping skills so that patients and families are empowered to make informed decisions as illnesses progress. These tasks cannot be accomplished in a single consultation. In fact, the content of PC clinic visits has been shown to evolve over the course of illness,23 which is difficult to replicate in the time-limited, emotionally fraught space of an acute hospitalization. As such, in line with previous research on early PC,1-4 our findings suggest that outpatient PC involvement may be associated with an even greater impact on EOL care quality and health care utilization than inpatient PC alone, reaffirming ASCO's clinical practice guidelines stating that referral to specialized PC should occur within 8 weeks of an advanced cancer diagnosis.6

Unfortunately, patients seen by outpatient PC represented less than one quarter of all decedents in this sample (n = 111 of 522; 21%), most of whom died nearly a decade after the publication of Temel et al's1 landmark trial of early PC for metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer, and at least 1-2 years after the publication of the aforementioned ASCO guidelines. What is needed to make early, integrated PC a reality for all patients diagnosed with advanced cancer? This problem requires a multifaceted solution, including education and outreach to referring clinicians, growth of the specialized PC workforce, and the development of automatic referral criteria or triggers for PC involvement, which have been studied at a few centers.20,21 Most importantly, hospitals and cancer centers must prioritize support for PC at an institutional level, recognizing that despite recent advances in telemedicine, robust outpatient PC may require a greater investment of administrative support and clinic space than an inpatient consultation service. Our study and others suggest that this investment is worthwhile—that access to outpatient PC is associated with better care quality in the hospital.

This is not to suggest that inpatient PC is not beneficial; indeed, in this severely ill cohort, inpatient PC was associated with significant differences in EOL quality outcomes, including more frequent dyspnea management, increased hospice utilization and ACP, and reduced in-hospital deaths. Importantly, the association between inpatient PC and hospital LOS should not be interpreted as a causal relationship, as PC was consulted by physician discretion, and we could not control for confounding by indication. Rather, our findings argue that one critical function of the inpatient PC team (in addition to managing acute symptoms and providing expert communication during crises) may be to facilitate more frequent referrals to outpatient PC for a patient population that would benefit from those services.

There are important limitations to this study. First, its findings represent the experiences and outcomes of decedents at a single tertiary cancer center. As such, they may not readily generalize to other centers, especially nonacademic, nonmetropolitan cancer centers and hospitals, which may have different institutional cultures around PC referral, practice patterns surrounding EOL care, and availability of PC resources. As a result, however, our data highlight that even at a cancer center with a robust rate of hospice referral (compared with data from a nationwide cohort of Medicare beneficiaries across 54 cancer centers),24 PC exposure is still associated with significant improvements in care quality. We theorize that PC services may be more impactful at cancer centers with lower baseline adherence to EOL quality measures.

A second important limitation is the retrospective, observational design of this study, such that we cannot infer causality, only association. In the absence of randomized exposure to PC, or a matched control group, we could not control for confounders mediating the observed associations between PC exposure and the outcomes described above. Some potential confounders that could not be reliably abstracted from the medical record include performance status at the time of hospitalization, the natural history of disease and status of cancer-directed therapy, and patient and family goals and care preferences. The associations we report should be interpreted with these limitations in mind.

The retrospective, observational nature of the study also introduced other limitations. We could not determine all decedents' location of death by reviewing medical records and obituaries. In addition, we chose to study a cohort of hospitalized decedents, for the reasons stated earlier. Although we believe this is an important patient group whose experiences have been underdescribed in the literature, our findings may not generalize to all decedents with cancer; for example, decedents who were never hospitalized toward EOL may have had different exposure to outpatient PC (and presumably less exposure to inpatient PC, or none at all).

In summary, in a population of decedents with cancer hospitalized toward EOL, PC exposure in any setting was associated with several important EOL quality outcomes, whereas PC exposure specifically in the outpatient setting was linked to shorter hospital LOS and longer hospice LOS. These findings underscore the importance of outpatient PC involvement. Inpatient PC teams are effective and valuable on their own, but one of their important functions may be to facilitate more connections between seriously ill patients and a robust, well-resourced outpatient PC team. Further work is needed to clarify how PC teams can best deliver this care in a way that is impactful, sustainable, and replicable across all cancer centers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR002541) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Hospital LOS

Jonathan C. Yeh

Employment: Takeda (I)

Research Funding: Takeda (I)

Mary K. Buss

Honoraria: UpToDate

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the ASCO Quality Care Symposium, Boston, MA, September 24-25, 2021.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Jonathan C. Yeh, Arielle R. Urman, Robert J. Besaw, Mary K. Buss

Administrative support: Robert J. Besaw

Collection and assembly of data: Jonathan C. Yeh, Arielle R. Urman, Robert J. Besaw

Data analysis and interpretation: Jonathan C. Yeh, Arielle R. Urman, Laura E. Dodge, Kathleen A. Lee, Mary K. Buss

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Different Associations Between Inpatient or Outpatient Palliative Care and End-of-Life Outcomes for Hospitalized Patients With Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Jonathan C. Yeh

Employment: Takeda (I)

Research Funding: Takeda (I)

Mary K. Buss

Honoraria: UpToDate

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733-742, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. : Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33:1438-1445, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al. : Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: Outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33:1446-1452, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383:1721-1730, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. : Emergency department-initiated palliative care in advanced cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2:591-598, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. : Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 35:96-112, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hui D, De La Rosa A, Chen J, et al. : State of palliative care services at US cancer centers: An updated national survey. Cancer 126:2013-2023, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braiteh F, El Osta B, Palmer JL, et al. : Characteristics, findings, and outcomes of palliative care inpatient consultations at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 10:948-955, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jack B, Hillier V, Williams A, et al. : Improving cancer patients' pain: The impact of the hospital specialist palliative care team. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 15:476-480, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kao CY, Hu WY, Chiu TY, et al. : Effects of the hospital-based palliative care team on the care for cancer patients: An evaluation study. Int J Nurs Stud 51:226-235, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Li Z, et al. : Symptom distress, interventions, and outcomes of intensive care unit cancer patients referred to a palliative care consult team. Cancer 115:437-445, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loke SS, Rau KM, Huang CF: Impact of combined hospice care on terminal cancer patients. J Palliat Med 14:683-687, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou WC, Hung YS, Kao CY, et al. : Impact of palliative care consultative service on disease awareness for patients with terminal cancer. Support Care Cancer 21:1973-1981, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson LC, Usher B, Spragens L, et al. : Clinical and economic impact of palliative care consultation. J Pain Symptom Manage 35:340-346, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. : Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 30:454-463, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.May P, Garrido MM, Cassel JB, et al. : Prospective cohort study of hospital palliative care teams for inpatients with advanced cancer: Earlier consultation is associated with larger cost-saving effect. J Clin Oncol 33:2745-2752, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang GM, Neo SH, Lim SZ, et al. : Effectiveness of hospital palliative care teams for cancer inpatients: A systematic review. J Palliat Med 19:1156-1165, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc T, VanDusen H, et al. : Effect of inpatient palliative care on quality of life 2 weeks after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 316:2094-2103, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Jawahri A, LeBlanc TW, Kavanaugh A, et al. : Effectiveness of integrated palliative and oncology care for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 7:238-245, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocque GB, Campbell TC, Johnson SK, et al. : A quantitative study of triggered palliative care consultation for hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 50:462-469, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adelson K, Paris J, Horton JR, et al. : Standardized criteria for palliative care consultation on a solid tumor oncology service reduces downstream health care use. JCO Oncol Pract 13:e431-e440, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riedel RF, Slusser K, Power S, et al. : Improvements in patient and health system outcomes using an integrated oncology and palliative medicine approach on a solid tumor inpatient service. JCO Oncol Pract 13:e738-e748, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoerger M, Greer JA, Jackson VA, et al. : Defining the elements of early palliative care that are associated with patient-reported outcomes and the delivery of end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol 36:1096-1102, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wasp GT, Alam SS, Brooks GA, et al. : End-of-life quality metrics among Medicare decedents at minority-serving cancer centers: A retrospective study. Cancer Med 9:1911-1921, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]