Abstract

Sirtuins (SIRTs) belong to the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent class III histone deacetylase family. They are key regulators of cellular and physiological processes, such as cell survival, senescence, differentiation, DNA damage and stress response, cellular metabolism, and aging. SIRTs also influence carcinogenesis, making them potential targets for anticancer therapeutic strategies. In this study, we investigated the anticancer properties and underlying molecular mechanisms of a novel SIRT1 inhibitor, MHY2251, in human colorectal cancer (CRC) cells. MHY2251 reduced the viability of various human CRC cell lines, especially those with wild-type TP53. MHY2251 inhibited SIRT1 activity and SIRT1/2 protein expression, while promoting p53 acetylation, which is a target of SIRT1 in HCT116 cells. MHY2251 treatment triggered apoptosis in HCT116 cells. It increased the percentage of late apoptotic cells and the sub-G1 fraction (as detected by flow cytometric analysis) and induced DNA fragmentation. In addition, MHY2251 upregulated the expression of FasL and Fas, altered the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2, downregulated the levels of pro-caspase-8, -9, and -3 proteins, and induced subsequent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage. The induction of apoptosis by MHY2251 was related to the activation of the caspase cascade, which was significantly attenuated by pre-treatment with Z-VAD-FMK, a pan-caspase inhibitor. Furthermore, MHY2251 stimulated the phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and MHY2251-triggered apoptosis was blocked by pre-treatment with SP600125, a JNK inhibitor. This finding indicated the specific involvement of JNK in MHY2251-induced apoptosis. MHY2251 shows considerable potential as a therapeutic agent for targeting human CRC via the inhibition of SIRT1 and activation of JNK/p53 pathway.

Keywords: MHY2251, SIRT1, JNK/p53 pathway, Apoptosis, Colorectal cancer cell

INTRODUCTION

Despite the recent advances in diagnostic and surgical techniques, colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the third most frequently diagnosed cancer and second most common cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide (Li, 2018). CRC is mainly treated by surgical removal, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of surgery and chemotherapy (Yang et al., 2017). Despite various treatment strategies, many patients with CRC continue to experience relapse—hence, improved chemotherapeutic agents that can effectively induce apoptosis in CRC cells are urgently needed.

Apoptosis involves two types of signaling pathways. The extrinsic pathway is initiated by the binding of specific receptors on the cell surface, called death receptors, with an extracellular ligand. This involves the binding of Fas receptors, known as differentiation clusters, to Fas ligands, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptors to TNF (Ashkenazi, 2008; Fulda, 2015). These binding events induce the activation of caspase 8 in the intracellular domain of the receptor (O’Brien and Kirby, 2008; Wong, 2011). Activated caspase 8 can affect mitochondria or further activate caspase 3 (Ashkenazi, 2008). The intrinsic pathway is initiated by the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, resulting in the release of internalized cytochrome c into the cytoplasm (Saelens et al., 2004). The released cytochrome c activates caspase 3 by forming a complex called the apoptosome with apoptosis protease activator 1 and caspase 9 (Elmore, 2007). A family of proteins called B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), which can inhibit or induce apoptosis, regulate this pathway (Cory and Adams, 2002). Both pathways can affect each other and cleave poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) via activated caspase 3, which ultimately leads to apoptosis.

Chromatin alteration by histone modification has epigenetic effects on various cellular processes such as DNA recombination, cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and apoptosis (Chrun et al., 2017). Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are known for their ability to remove acetyl groups at lysine residues in histone proteins, but recent several studies have demonstrated that they deacetylate both histones and non-histone proteins (Mariadason, 2008; Ocker, 2010; Halasa et al., 2021). The class III HDAC member sirtuin (SIRT), is a highly conserved group of seven proteins in humans. In addition, class III HDACs have almost no homology with other classes and are unaffected by HDAC inhibitors, such as butyrate, valproic acid, trichostatin A, or suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (Mariadason, 2008).

In particular, SIRT1 inhibits the function of p53 via deacetylation of lysine residue 382 of p53, which may contribute to tumor growth (Ghosh et al., 2017). SIRT1 upregulation has been observed in prostate cancer, primary CRC, melanoma, and non-melanoma skin cancer (Alves-Fernandes and Jasiulionis, 2019). Moreover, SIRT1 levels are elevated in stages I, II, and III CRC (Kabra et al., 2009; Lv et al., 2014). Thus, strategies to inhibit SIRT1 may be useful for the treatment of CRC via p53 activation. Several HDAC inhibitors have been approved for the treatment of T-cell lymphoma and multiple myeloma by the United States Food and Drug Administration. However, anticancer drugs that inhibit SIRT have not yet been approved, and several such candidates are undergoing clinical trials.

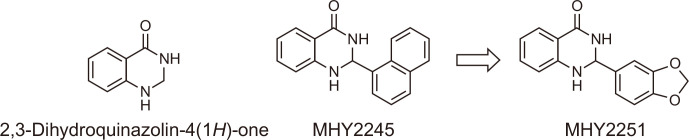

In previous studies, MHY2245, a 2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4-one analog, was identified as a promising anticancer agent. This compound exhibited anticancer activity by inhibiting the pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2)/mTOR pathway in human ovarian cancer cells (Tae et al., 2020) or inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HCT116 human colorectal cancer cells (Kang et al., 2022). The discovery of MHY2245’s anticancer activity led us to design and synthesize a number of MHY2245 analogs (Fig. 1). MHY2251 is one of the synthesized MHY2245 analogs with a 2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4-one template. MHY2251 [2-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one] was synthesized in 93% yield by the condensation reaction of anthranilamide and piperonal in the presence of a catalytic amount of sulfamic acid. The structure of MHY2251 was confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy.

Fig. 1.

The rationale for the design of MHY2251 [2-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one] and chemical structures of 2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one, MHY2245, and MHY2251.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) engage in essential signaling pathways that mediate cellular responses to extracellular signals. Abnormalities in the MAPK signaling pathway are implicated in various diseases, such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders (Kim and Choi, 2010; Wu et al., 2019). Among the MAPK superfamily, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylates Ser63 and Ser73 at the N-terminus of c-Jun, a transcription factor (Jing and Anning, 2005). JNK affects the growth of cancer cells by activating c-Jun, a proto-oncoprotein, in various cancers. In addition, JNK is involved in the development of CRC via its interaction with various other pathways, and ongoing studies have attempted to elucidate these mechanisms (Wan et al., 2020). Thus, promoting apoptosis via JNK regulation may be an effective strategy in CRC treatment.

This study was conducted to investigate whether MHY2251 induces apoptosis via SIRT inhibition and JNK/p53 pathway in HCT116 cells and to determine the underlying mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of MHY2251

Chemical reagents (anthranilamide, piperonal, and sulfamic acid) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and Daejung Chemicals (Sheung, Gyeonggi, Korea). 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum was recorded on a Varian Unity AS500 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and 13C NMR spectrum was recorded on a Varian Unity INOVA 400 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). Dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DMSO-d6, Amresco, Solon, OH, USA) was used as an NMR solvent for 1H and 13C NMR. All chemical shifts were expressed as parts per million (ppm), with deuterated peaks (δH 2.50 and δC 39.7), and coupling constant values (J values) were recorded in hertz (Hz). The following abbreviations are used in 1H NMR data: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), and m (multiplet). The progress of the reaction is monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), and TLC was conducted on Merck precoated 60F245 plates (Merck, Billerica, MA, USA).

To a stirred suspension of 2-aminobenzamide (anthranilamide, 100 mg, 0.73 mmol) and benzo[d][1,3]dioxole-5-carbaldehyde (piperonal, 110 mg, 0.73 mol) in methanol (2.0 mL) was added sulfamic acid (7 mg, 0.07 mmol) and the reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 2 h. After neutralizing to pH 7 using 0.1N NaOH solution, the formed solid was filtered, and washed with H2O to give pure 2-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-2,3-dihydroquinazolin-4(1H)-one (MHY2251, 183 mg, 92.8%) as a solid. 1H MMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ8.19 (s, 1H, CONH), 7.58 (d, 1H, J=7.5 Hz, 5-H), 7.22 (t, 1H, J=7.5 Hz, 7-H), 7.02-7.01 (m, 2H, 1-NH, 4′-H), 6.93 (d, 1H, J=8.0 Hz, 6′-H), 6.88 (d, 1H, J=8.0 Hz, 7′-H), 6.72 (d, 1H, J=7.5 Hz, 8-H), 6.65 (t, 1H, J=7.5 Hz, 6-H), 5.99 (s, 2H, CH2), 5.65 (s, 1H, 2-H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ164.3, 148.5, 148.0, 147.9, 136.2, 134.0, 128.0, 121.1, 117.8, 115.6, 115.1, 108.5, 107.8, 101.8, 66.9.

Chemicals

The stock solution of MHY2251 was prepared at a concentration of 10 mM in DMSO and stored at –20°C. Prior to the experiments, working dilutions were prepared in cell culture medium. The maximum concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1% (v/v) in the treatment range of 2.5-10 µM, and did not affect cell growth.

Cell culture

Cell were cultured as described previously (Kim et al., 2015). Human CRC cell lines (HCT116 with TP53 wild-type, HT-29 with TP53 mutant type, and DLD-1 with TP53 mutant type) and IEC-18, normal small intestinal epithelial cell lines from rats, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). CRC cells were cultured in an incubator at 37°C in humidified 95% air and 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). IEC-18 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Welgene Inc., Daegu, Korea) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 units/mL penicillin.

SIRT1 activity assay

The activity of SIRT1 was assessed using a SIRT1 fluorometric drug discovery kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA). MHY2251 at the indicated concentration in DMSO at a concentration that does not interfere with SIRT1 activity, was incubated with NAD+ (100 µM), Fluor de Lys-SIRT1 substrate (25 µM) and 0.04 U/µL SIRT1 at 37°C for 45 min. The concentration of deacetylated substrate was evaluated after adding a developer that terminated SIRT1 enzyme activity, and fluorescence was detected at an excitation wavelength of 360 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm using a fluorescent plate reader (GENios, TECAN Instrument, Salzburg, Austria).

Cell viability by MTT assay

Cell viability was measured by evaluating the metabolic activity of mitochondria in living cells using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Amresco), as previously described (Kim et al., 2015). The MTT assay was conducted using mitochondrial enzymes to reduce yellow tetrazolium MTT to purple MTT formazan. Cells were seeded on culture plates and treated with or without diverse reagents in each growth medium for the indicated concentrations for 24 or 48 h. The reagent-treated cells were further cultured for 2 h by adding MTT (0.5 mg/mL) in the dark. The formazan granules produced by living cells were dissolved in DMSO, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a multi-well reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vantaa, Finland). The percentage of viable cells was calculated according to the formula [(treated group/control group)×100].

Nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342

HCT116 cells were treated with MHY2251 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h and then stained with 4 µg/mL Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37°C for 20 min as previously described (Kim et al., 2015). The stained cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (ZEISS, Göttingen, Germany).

Flow cytometry analysis

This process was performed by flow cytometry as described previously (Park et al., 2011). The proportion of apoptotic cells was quantified using annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and suspended in 1X binding buffer (Becton-Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The suspended cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and annexin V-FITC solution (Becton-Dickinson Biosciences) for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. The stained cells were analyzed for apoptosis within 1 h using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). To prepare for sub-G1 fraction analysis, cells were first seeded in a well culture plate and incubated for 24 h, harvested with trypsin, washed with cold PBS, and fixed overnight at –20°C using 70% ethanol. Overnight ethanol-fixed cells were centrifuged, washed with cold PBS, and stained with cold PI solution (50 µg/mL in PBS) in the dark at 37°C for 30 min. Flow cytometry was performed using Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences).

DNA fragmentation assay

The DNA ladder formation was detected as described previously (Park et al., 2013). Cell lysates were prepared on ice for 30 min in buffer containing 5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 0.5% Triton X-100. Fragmented DNA was treated with RNase and proteinase K to increase its purity. Then, DNA was extracted with a phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol mixture (25:24:1, v/v/v) and precipitated with isopropanol. DNA isolated from 1.6% agarose gel containing 0.1 µg/mL ethidium bromide was visualized with an ultraviolet light source.

Caspase activity assay

Caspase activity was measured as described previously (Kim et al., 2015). The cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS, and lysed in lysis buffer (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) on ice for 20 min. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 10,000×g for 2 min and 100 µg of total protein was quantified. The quantified protein was mixed with 2X reaction buffer and colorimetric tetrapeptides, Z-DEVD, Z-IETD, and Ac-LEHD, for caspase-3, -8, and -9, respectively. After the reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 2 h, the enzymatic release of p-nitroaniline (pNA) was confirmed by measurement at 405 nm using a multi-well reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (Kim et al., 2015). Cells were harvested using trypsin after treatment with the indicated concentrations of inhibitor or MHY2251. Total protein was obtained by dissolving cells in lysis buffer containing 5 mM EDTA, 1% Nonoxynol-40, 100 µg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 µg/mL leupeptin, 250 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). The proteins were quantified using protein assay reagents (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of quantified proteins were denatured by boiling at 100°C for 5 min in a sample buffer (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated by 8-15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked for 45 min at room temperature with shaking using 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBS-T; 20 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 and 0.1% Tween-20). The membranes were then washed thrice for 10 min each with TBS-T. The blocked membranes were incubated overnight with the desired primary antibodies in TBS and incubated again with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) for 2 h. After washing, the band of the desired protein was visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Monoclonal antibodies specific for Bax (SC-493/rabbit/1:500), Bcl-2 (SC-7382/mouse/1:500), Fas (SC-715/rabbit/1:500), FasL (SC-834/rabbit/1:1,000), PARP (SC-7150/rabbit/1:1,000), pro-caspase-3 (SC-7272/mouse/1:1,000), pro-caspase-8 (SC-7890/rabbit/1:500), pro-caspase-9 (SC-7885/rabbit/1:500), p21 (SC-817/mouse/1:1,000), p53 (SC-126/mouse/1:500), SIRT1 (SC-15404/rabbit/1:500), and SIRT2 (SC-20966/rabbit/1:500) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Monoclonal antibodies specific for JNK (9252s/rabbit/1:1,000), p-JNK (9255s/mouse/1:1,000), and γ-H2AX (2577s/rabbit/1:1,000) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Monoclonal antibodies specific for p53K382Ac (ab75754/rabbit/1:500) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Monoclonal antibodies against β-actin (A5441/mouse/1:3000) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s test. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESUTLS

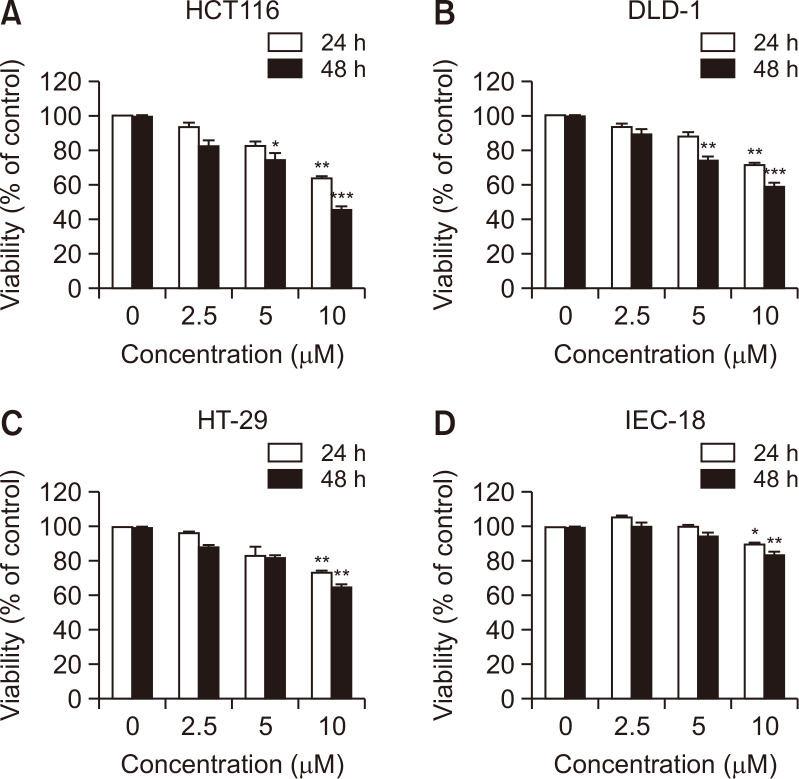

MHY2251 exerts cytotoxic effects on CRC cell lines

To evaluate the cytotoxicity of MHY2251, cell viability was examined by MTT assay using IEC-18 (rat intestinal epithelial cells), HCT116 (TP53 wild-type), HT-29 (TP53 mutant), and DLD-1 (TP53 mutant) human CRC cells. Treatment with MHY2251 inhibited the growth of CRC cell lines in a time- and concentration-dependent manner and exhibited more effective cytotoxicity in HCT116 than in HT-29 and DLD-1 cells (Fig. 2A-2C). In addition, normal intestinal cells (IEC-18) were less cytotoxic than CRC cells (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that MHY2251 has antiproliferative activity in CRC cells. Based on these findings, HCT116 cells were selected for subsequent experiments.

Fig. 2.

Effect of MHY2251 on the viability of human CRC cell lines and IEC-18 normal rat intestinal epithelial cells. (A) HCT116, (B) HT-29, (C) DLD-1, and (D) IEC-18 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of MHY2251 for 24 h and 48 h. The percentage of cell survival was determined by the MTT assay. Results are expressed as a percentage of vehicle-treated control ± SD of three separate experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 vs. vehicle-treated control.

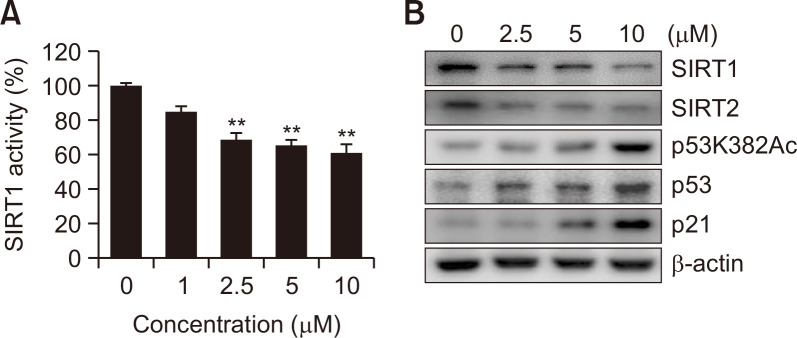

MHY2251 inhibits SIRT1 activity and expression of related proteins

SIRT1 activity was measured using a kit to examine the effects of MHY2251 on SIRT1 activity. MHY2251 significantly inhibited the activity of SIRT1 (Fig. 3A). Next, the effect of MHY2251 treatment on the expression of SIRT1-related proteins was examined by western blotting. As shown in Fig. 3B, the expression levels of SIRT1/2 decreased as the concentration of MHY2251 increased. Previous studies have demonstrated that acetylation of lysine 382 of p53 is the target site of SIRT1 and 2 (Solomon et al., 2006; van der Veer et al., 2007). Hence, we examined the levels of p53 acetylation at lysine 382 in HCT116 cells exposed to MHY2251. Treatment with MHY2251 increased the acetylation level of p53, as well as the protein expression levels of p53 and its target protein p21 (Fig. 3B). Therefore, this study demonstrated that MHY2251 inhibits the deacetylation activity of SIRT1 and related protein changes.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effects of MHY2251 on SIRT1 activity and the expression levels of related proteins. (A) In vitro SIRT1 deacetylase activity was measured by Fluor-de-Lys fluorometric assays. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. **p<0.01 compared with vehicle-treated control cells. (B) HCT116 cells were treated with MHY2251 for 24 h, and cell lysates were immunoblotted with SIRT1, SIRT2, p53K382Ac, p53, or p21 antibodies. β-actin was used as a loading control. The representative results of three independent experiments are shown.

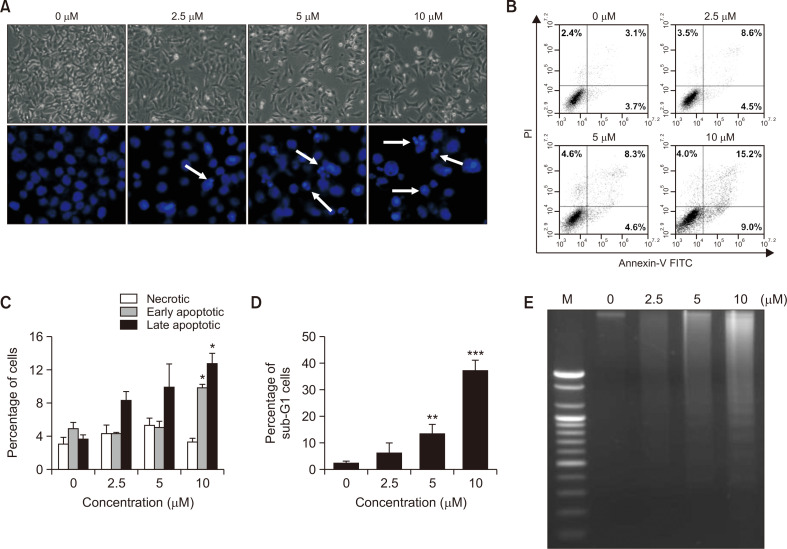

MHY2251 induced apoptosis in HCT116 cells

To investigate whether MHY2251 induces apoptosis, morphological changes were observed under a microscope. The cell density of the MHY2251 treated groups was reduced in a concentration-dependent manner compared to that of the untreated group (Fig. 4A, top panel). In addition, morphological changes in the nuclear structure were detected by Hoechst 33342 staining. MHY2251 treatment resulted in marked shrinkage and chromatin condensation in HCT116 cells (Fig. 4A, bottom panel). Flow cytometry was performed using annexin V-FITC and PI double staining to determine whether apoptotic cell death was increased by MHY2251 treatment. The proportion of early apoptotic cells (Fig. 4B, lower right quadrant) increased from 3.7% (0 µM) to 9.0%, and the proportion of late apoptotic cells (Fig. 4B, upper right quadrant) increased from 3.1% (0 µM) to 15.2% after 24 h of treatment with 10 µM MHY2251. This result also confirmed that apoptosis induced by MHY2251 was concentration dependent (Fig. 4C). Another hallmark of apoptosis, an increase in the sub-G1 fraction, was also confirmed by flow cytometry. Treatment with MHY2251 increased the accumulation of the sub-G1 fraction in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4D). DNA fragmentation, an event that occurs during apoptosis, was monitored using agarose gel electrophoresis. The DNA fragment ladder pattern, which was not found in the untreated group, increased in a concentration-dependent manner in the MHY2251 treated groups (Fig. 4E). These results also indicated that MHY2251 treatment caused apoptotic cell death in a concentration-dependent manner in HCT116 cells.

Fig. 4.

Apoptotic effect of MHY2251 on HCT116 cells. (A) Cells were treated with MHY2251 for 24 h and morphological changes were observed under a phase-contrast microscope (top panel). Cells treated in the same way were stained with Hoechst 33342 to detect nuclear changes (bottom panel). White arrows indicate the nuclei of apoptotic cells (original magnification, 400×). (B) HCT116 cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentage of upper left quadrant means necrotic cells, percentage of lower right quadrant means early apoptotic cells, and percentage of upper right quadrant means late apoptotic cells. (C) Percentage of necrotic, early apoptotic, and late apoptotic cells. *p<0.05 vs. vehicle-treated control. (D) Percentage of sub-G1 cells with augmentation of MHY2251 concentration. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. vehicle-treated control. (E) Fragmented genomic DNA was extracted from the cells and monitored by 1.6% agarose gel electrophoresis. M, marker. All the above data are the representative of three separate experiments.

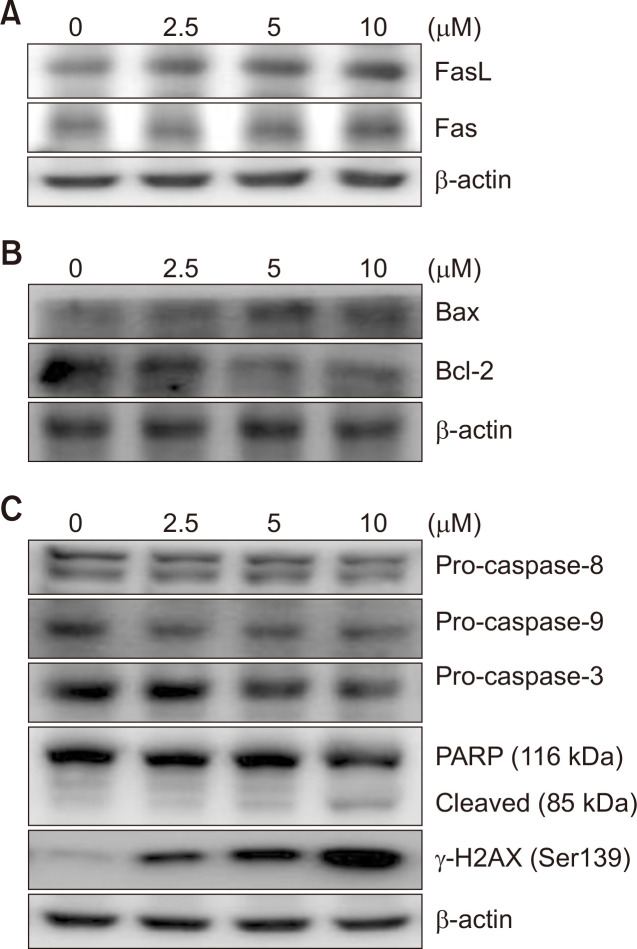

MHY2251 modulates the expression of apoptosis-related proteins in HCT116 cells

Western blotting was performed to investigate MHY2251-mediated changes at the molecular level. Fas and FasL, which are death receptors and their ligands in the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis, respectively, were increased in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein, was downregulated and Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax), a pro-apoptotic protein, was increased, suggesting that it also passes through the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis (Fig. 5B). Since caspases are activated through cleavage, pro-caspase-8 and -9 decrease in a concentration-dependent manner in the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways of apoptosis, respectively, leading to a decrease in pro-caspase-3, a precursor of the executor caspase. Moreover, cleavage of PARP, a molecular marker of apoptosis, and increased expression of γ-H2AX, a marker of DNA damage, were distinctly induced by MHY2251 treatment (Fig. 5C). The above results revealed that treatment of MHY2251 in HCT116 cells induced apoptosis through both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways.

Fig. 5.

Effect of MHY2251 on the levels of apoptotic proteins in HCT116 cells. (A-C) Total lysates of HCT116 cells treated with MHY2251 were immunoblotted and each datum represents three separate experiments. β-actin was used as a loading control. Bax, Bcl-2 associated X protein; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase.

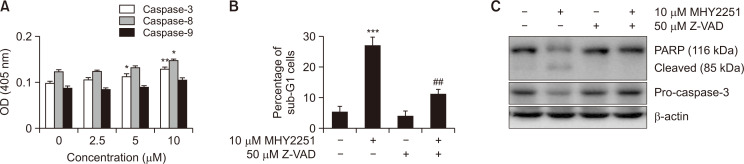

Caspase inhibition attenuates MHY2251-induced apoptosis in HCT116 cells

Based on previous results on the protein expression of pro-caspases, the effect of MHY2251 on caspase activity was investigated using specific substrates. Cells treated with MHY2251 showed notably increased caspase activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6A). Next, to investigate the relationship between caspase activation and MHY2251-induced apoptosis, flow cytometry analysis and western blotting were performed after treating the cells with the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. Although Z-VAD-FMK treatment alone had no effect, pre-treatment with Z-VAD-FMK alleviated the percentage of cells arrested in the sub-G1 fraction by MHY2251 (Fig. 6B). In addition, pre-treatment with Z-VAD-FMK inhibited pro-caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage at the protein level, suggesting that Z-VAD-FMK inhibited apoptosis through the caspase cascade induced by MHY2251 (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Caspase activation associated with MHY2251-induced apoptosis. (A) Caspase-3, -8, and -9 activities were measured using Z-DEVD-pNA, Z-IETD-pNA, and Ac-LEHD-pNA substrates, respectively. The data represent the mean ± SD values of three separate experiments. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 vs. vehicle-treated cells. (B) The sub-G1 fraction percentage was confirmed by flow cytometry after PI staining of Z-VAD-FMK and/or MHY2251 treated cells. The data represent the mean ± SD values of three separate experiments. ***p<0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells and ##p<0.01 vs. MHY2251-treated cells. (C) Total lysates of HCT116 cells treated with MHY2251 were immunoblotted via western blotting for pro-caspase-3 and PARP. Results represent three separate experiments. β-actin was used as a loading control. PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; PI, propidium iodide.

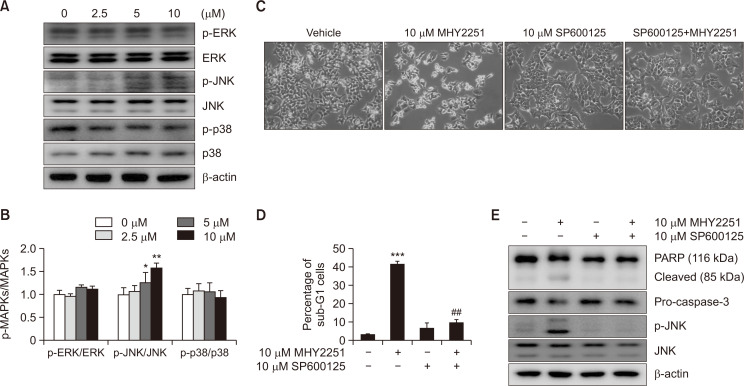

JNK is involved in MHY2251-induced apoptosis of HCT116 cells

The effects of MHY2251 on the MAPK pathway were studied to elucidate the pathways involved in apoptosis induction. The total levels of phosphorylated ERK, JNK, and p38 were measured by western blot analysis (Fig. 7A). As a result of measuring the ratio of phosphorylated proteins and total proteins, the ratio of phosphorylated MAPKs to total MAPKs significantly increased only in JNK in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 7B). Consequently, the effect of JNK on MHY2251-induced apoptosis was further studied using the JNK inhibitor SP600125. As expected, apoptosis induced by MHY2251 was significantly alleviated by SP600125 pre-treatment (Fig. 7C). Subsequently, the effects of SP600125 pre-treatment on apoptosis induced by MHY2251 treatment were investigated using flow cytometry and western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 7D, pre-treatment of HCT116 cells with SP600125 significantly decreased the accumulation of sub-G1 fractions induced by MHY2251 treatment. In addition, pre-treatment with SP600125 inhibited MHY2251-induced PARP cleavage, pro-caspase-3 activation, and JNK phosphorylation (Fig. 7E). Taken together, these results suggest that MHY2251 treatment induces apoptosis in HCT116 cells via the JNK/p53 pathway.

Fig. 7.

Role of JNK in MHY2251-induced apoptosis in HCT116 cells. (A, B) Cells were incubated with indicated concentrations of MHY2251 for 24 h and total cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting using p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK, p-p38, and p38 antibodies and each ratio of phosphorylation and total protein of MAPKs. The data represent the mean ± SD values of three separate experiments. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 vs. vehicle-treated cells. (C) Cells were treated with 10 µM MHY2251 for 24 h after pre-treatment of 10 µM SP600125 for 30 min and monitored using a phase-contrast microscope. (D) The percentage of sub-G1 cells was evaluated with flow cytometry. The data represent the mean ± SD values of three separate experiments. ***p<0.001 vs. vehicle-treated cells and ##p<0.01 vs. MHY2251-treated cells. (E) Protein expression levels of PARP, pro-caspase-3, p-JNK, and JNK were measured by western blotting. Representative data from three separate experiments are shown. β-actin was used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

Since epigenetic regulation of genes plays a key role in the development and progression of malignant tumors, HDAC inhibitors are being evaluated for their cancer suppression ability (Shabason and Camphausen, 2010). In this study, we investigated the inhibitory effects of MHY2251 on SIRT1, a class III HDAC, in HCT116 human CRC cells. MHY2251 inhibited SIRT1 activity, induced apoptosis via the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways, and activated the JNK pathway.

SIRT1 is upregulated and enhanced via deacetylation of its target p53 (Chen et al., 2014). Our study demonstrated that MHY2251 inhibited SIRT1 activity and promoted p53 acetylation—these findings are consistent with previous studies. In addition, MHY2251 increased the expression levels of p53 and downstream inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases, such as p21. These results suggest that MHY2251 suppresses CRC cell growth by restoring p53 expression and acetylation via SIRT1 inhibition.

One of the most important p53 functions is the ability to activate apoptosis, and disruption of this process can promote tumor progression and chemo-resistance (Gottlieb and Oren, 1998; Wachter et al., 2013). In particular, p53 forms a homotetrameric transcription factor that has been reported to directly regulate ~500 target genes, leading to a wide range of cellular processes including cell cycle arrest, cellular senescence, DNA repair, metabolic adaptation, and cell death such as apoptosis (Aubrey et al., 2018). During apoptosis, p53 indirectly inhibits the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 through pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins, such as p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) and NOXA (Aubrey et al., 2018). The major morphological feature of apoptosis is DNA fragmentation after chromatin condensation (Gerschenson and Rotello, 1992). Similarly, this study also demonstrated the morphological alteration of apoptosis, and at the protein level, increased expression levels of receptors and ligands related to the extrinsic pathway. In addition, there was a change in the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 corresponding to the intrinsic pathway. Moreover, reduction in the levels of precursors of caspases contributing to apoptosis signal transduction, cleavage of PARP, and DNA damage through increased levels of γ-H2AX were also confirmed. These results prove that MHY2251 induces apoptosis via the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways in HCT116 cells by restoring p53 acetylation.

In cancer, TP53 is the most frequently mutated tumor suppressor gene in human cancer (Zhu et al., 2020). Most of the TP53 mutations are missense mutations, resulting in the expression of the full-length p53 mutant protein. Mutant p53 proteins not only lose their wild-type p53-dependent tumor suppressor function, but also frequently acquire oncogenic gain-of-function (GOF) that promotes tumorigenesis. However, although the mechanism of apoptosis by p53-independent pathways in various cancer cells is well known, there are many reports that the cytotoxic response is not as strong as that of wild-type 53 cells (Zhu et al., 2020; Kang et al., 2022). TP53 mutations in CRC are associated with a poor prognosis, increased chemoresistance, and lymphatic infiltration. Therefore, although many studies are currently underway on the treatment of TP53 mutations in CRC, no clear results have been revealed (Li et al., 2015; Aubrey et al., 2018). Thus, a study using a TP53 mutant CRC cell line is necessary as a follow-up to this study.

As key operators of apoptosis, caspases play a crucial role in the induction and amplification of apoptotic signals in cells (Fan et al., 2005). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate whether MHY2251-induced apoptosis induces caspase activity. In contrast to the concentration-dependent increase in caspase activity when HCT116 cells were treated with MHY2251, the activation of pro-caspase-3 and cleavage of PARP were inhibited in the presence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. Therefore, MHY2251-induced apoptosis proceeds via the caspase cascade.

Further experiments were conducted to determine the pathways underlying MHY2251-induced apoptosis. In particular, MAPKs that regulate various biological activities, including apoptosis, have been investigated (Yue and López, 2020). In this study, a significant role of JNK (among the three MAPK proteins) was confirmed. JNK is an important factor in both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways (Dhanasekaran and Reddy, 2008). The JNK inhibitor SP600125 alleviated cell growth inhibition and suppressed the downregulation of pro-caspase-3 and PARP cleavage by MHY2251. This result indicated that MHY2251 induced apoptosis in HCT116 cells via the JNK pathway. In addition to the results of this study, another controversial issue is the causal relationship between SIRT1 and JNK. Whether SIRT1 activation occurs through JNK phosphorylation or JNK activation induced by SIRT1 is still under investigation (Lee et al., 2015; Liu and Cheng, 2018). Several substances with anticancer activity increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation in cancer cells and induce apoptosis through the ROS/JNK/c-Jun axis (Hwang et al., 2017; Jang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). However, when HCT116 cells were treated with MHY2251, ROS was not generated (data not shown). This suggests that MHY2251 does not pass through the ROS/JNK/c-Jun axis, and further studies are needed to elucidate the relationship between SIRT1 and JNK.

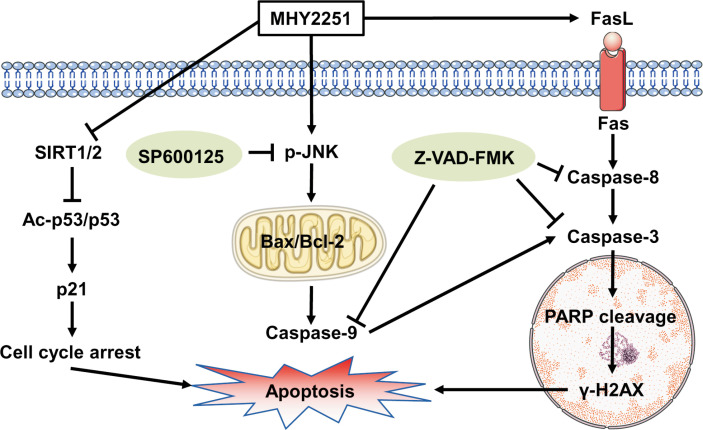

In summary, MHY2251 showed anti-proliferative activity and induced apoptosis in HCT116 cells expressing wild-type TP53. In addition, MHY2251 suppressed SIRT1 activity and its protein expression, subsequently increasing p53 acetylation and protein expression levels, thereby showing an anticancer effect. Moreover, apoptosis induced by MHY2251 treatment occurred through the caspase cascade via the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways, and activation of JNK, a member of the MAPK family, was involved upstream of this apoptotic process (Fig. 8). Overall, these results demonstrated that MHY2251 has the potential to be used as a therapeutic agent for treating CRC.

Fig. 8.

Proposed mechanism of MHY2251-induced apoptosis in HCT116 cells via SIRT1 inhibition and the JNK/p53 pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2021R1F1A1051265) and the Basic Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2018R1D1A1B07044648). We would like to thank the Aging Tissue Bank (http://grscicoll.org/institution/aging-tissue-bank) for providing research information.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- Alves-Fernandes D. K., Jasiulionis M. G. The role of SIRT1 on DNA damage response and epigenetic alterations in cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3153. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A. Targeting the extrinsic apoptosis pathway in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubrey B. J., Kelly G. L., Janic A., Herold M. J., Strasser A. How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:104–113. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Sun K., Jiao S., Cai N., Zhao X., Zou H., Xie Y., Wang Z., Zhong M., Wei L. High levels of SIRT1 expression enhance tumorigenesis and associate with a poor prognosis of colorectal carcinoma patients. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:7481. doi: 10.1038/srep07481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrun E. S., Modolo F., Daniel F. I. Histone modifications: a review about the presence of this epigenetic phenomenon in carcinogenesis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2017;213:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory S., Adams J. M. The Bcl2 family: regulators of the cellular life-or-death switch. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:647–656. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanasekaran D. N., Reddy E. P. JNK signaling in apoptosis. Oncogene. 2008;27:6245–6251. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan T. J., Han L. H., Cong R. S., Liang J. Caspase family proteases and apoptosis. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2005;37:719–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2005.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S. Targeting apoptosis for anticancer therapy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015;31:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerschenson L., Rotello R. Apoptosis: a different type of cell death. FASEB J. 1992;6:2450–2455. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.7.1563596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A., Sengupta A., Seerapu G. P. K., Nakhi A., Ramarao E. V. S., Bung N., Bulusu G., Pal M., Haldar D. A novel SIRT1 inhibitor, 4bb induces apoptosis in HCT116 human colon carcinoma cells partially by activating p53. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;488:562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb T. M., Oren M. p53 and apoptosis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 1998;8:359–368. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halasa M., Adamczuk K., Adamczuk G., Afshan S., Stepulak A., Cybulski M., Wawruszak A. Deacetylation of transcription factors in carcinogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:11810. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111810.e3cd48bdd4334780830464e4ba66298b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang N. L., Kang Y. J., Sung B., Hwang S. Y., Jang J. Y., Oh H. J., Ahn Y. R., Kim D. H., Kim S. J., Ullah S., Hossain M. A., Moon H. R., Chung H. Y., Kim N. D. MHY451 induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by ROS generation in HCT116 human colorectal cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2017;38:1783–1789. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J. Y., Kang Y. J., Sung B., Kim M. J., Park C., Kang D., Moon H. R., Chung H. Y., Kim N. D. MHY440, a novel topoisomerase Ι inhibitor, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via a ROS-dependent DNA damage signaling pathway in AGS human gastric cancer cells. Molecules. 2019;24:96. doi: 10.3390/molecules24010096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing L., Anning L. Role of JNK activation in apoptosis: a double-edged sword. Cell Res. 2005;15:36–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabra N., Li Z., Chen L., Li B., Zhang X., Wang C., Yeatman T., Coppola D., Chen J. SirT1 is an inhibitor of proliferation and tumor formation in colon cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:18210–18217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y. J., Jang J. Y., Kwon Y. H., Lee J. H., Lee S., Park Y., Jung Y. S., Im E., Moon H. R., Chung H. Y., Kim N. D. MHY2245, a sirtuin inhibitor, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HCT116 human colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:1590. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031590.8150a137cd02463199307ada79de4dc3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. K., Choi E. J. Pathological roles of MAPK signaling pathways in human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1802:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. H., Kang Y. J., Sung B., Kim D. H., Lim H. S., Kim H. R., Kim S. J., Yoon J. H., Moon H. R., Chung H. Y., Kim N. D. MHY-449, a novel dihydrobenzofuro[4,5-b][1,8]naphthyridin-6-one derivative, mediates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in AGS human gastric cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2015;34:288–294. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. Y., Lee W. T., Cheng C. H., Chen K. C., Chou C. M., Chung C. H., Sun M. S., Cheng H. W., Ho M. N., Lin C. W. Repositioning antipsychotic chlorpromazine for treating colorectal cancer by inhibiting sirtuin 1. Oncotarget. 2015;6:27580. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. Recent advances in colorectal cancer screening. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2018;4:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. L., Zhou J., Chen Z. R., Chng W. J. p53 mutations in colorectal cancer-molecular pathogenesis and pharmacological reactivation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015;21:84–93. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Cheng X. H. MiR-29b reverses oxaliplatin-resistance in colorectal cancer by targeting SIRT1. Oncotarget. 2018;9:12304–12315. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv L., Shen Z., Zhang J., Zhang H., Dong J., Yan Y., Liu F., Jiang K., Ye Y., Wang S. Clinicopathological significance of SIRT1 expression in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Med. Oncol. 2014;31:965. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0965-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariadason J. M. HDACs and HDAC inhibitors in colon cancer. Epigenetics. 2008;3:28–37. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.1.5736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien M. A., Kirby R. Apoptosis: a review of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic pathways and dysregulation in disease. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care. 2008;18:572–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2008.00363.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ocker M. Deacetylase inhibitors - focus on non-histone targets and effects. World J. Biol. Chem. 2010;1:55–61. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v1.i5.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. S., Hwang H. J., Kim G. Y., Cha H. J., Kim W. J., Kim N. D., Yoo Y. H., Choi Y. H. Induction of apoptosis by fucoidan in human leukemia U937 cells through activation of p38 MAPK and modulation of Bcl-2 family. Mar. Drugs. 2013;11:2347–2364. doi: 10.3390/md11072347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. S., Kim G. Y., Nam T. J., Kim N. D., Choi H. Y. Antiproliferative activity of fucoidan was associated with the induction of apoptosis and autophagy in AGS human gastric cancer cells. J. Food Sci. 2011;76:T77–T83. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens X., Festjens N., Walle L. V., Van Gurp M., Van Loo G., Vandenabeele P. Toxic proteins released from mitochondria in cell death. Oncogene. 2004;23:2861–2874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabason J. E., Camphausen K. HDAC inhibitors in cancer care. Oncology. 2010;24:180–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J. M., Pasupuleti R., Xu L., McDonagh T., Curtis R., DiStefano P. S., Huber L. J. Inhibition of SIRT1 catalytic activity increases p53 acetylation but does not alter cell survival following DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:28–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.28-38.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tae I. H., Son J. Y., Lee S. H., Ahn M. Y., Yoon K., Yoon S., Moon H. R., Kim H. S. A new SIRT1 inhibitor, MHY2245, induces autophagy and inhibits energy metabolism via PKM2/mTOR pathway in human ovarian cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16:1901–1916. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.44343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Veer E., Ho C., O'Neil C., Barbosa N., Scott R., Cregan S. P., Pickering J. G. Extension of human cell lifespan by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:10841–10845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan M., Wang Y., Zeng Z., Deng B., Zhu B., Cao T., Li Y., Xiao J., Han Q., Wu Q. Colorectal cancer (CRC) as a multifactorial disease and its causal correlations with multiple signaling pathways. Biosci. Rep. 2020;40:BSR20200265. doi: 10.1042/BSR20200265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachter F., Grunert M., Blaj C., Weinstock D. M., Jeremias I., Ehrhardt H. Impact of the p53 status of tumor cells on extrinsic and intrinsic apoptosis signaling. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013;11:27. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong R. S. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;30:87. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q., Wu W., Fu B., Shi L., Wang X., Kuca K. JNK signaling in cancer cell survival. Med. Res. Rev. 2019;39:2082–2104. doi: 10.1002/med.21574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Zhang Y., Wang L., Lee S. Levistolide A induces apoptosis via ROS-mediated ER stress pathway in colon cancer cells. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017;42:929–938. doi: 10.1159/000478647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J., López J. M. Understanding MAPK signaling pathways in apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:2346. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072346.ea6f3fdf31194ddd9c6b405921186f76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Zhou Q., Huang D., He L., Zhang H., Hu B., Peng H., Ren D. ROS/JNK/c-Jun axis is involved in oridonin-induced caspase-dependent apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;513:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G., Pan C., Bei J. X., Li B., Liang C., Xu Y., Fu X. Mutant p53 in cancer progression and targeted therapies. Font. Oncol. 2020;10:595187. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.595187.3f83fe63180c4f09a72a344b622f909c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]