Abstract

Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) integrates both immunological and non-immunological inputs to control cell survival and death. Small GTPases are versatile functional switches that lie on the very upstream in signal transduction pathways, of which duration of activation is very transient. The large number of homologous proteins and the requirement for site-directed mutagenesis have hindered attempts to investigate the link between small GTPases and IRF3. Here, we constructed a constitutively active mutant expression library for small GTPase expression using Gibson assembly cloning. Small-scale screening identified multiple GTPases capable of promoting IRF3 phosphorylation. Intriguingly, 27 of 152 GTPases, including ARF1, RHEB, RHEBL1, and RAN, were found to increase IRF3 phosphorylation. Unbiased screening enabled us to investigate the sequence-activity relationship between the GTPases and IRF3. We found that the regulation of IRF3 by small GTPases was dependent on TBK1. Our work reveals the significant contribution of GTPases in IRF3 signaling and the potential role of IRF3 in GTPase function, providing a novel therapeutic approach against diseases with GTPase overexpression or active mutations, such as cancer.

Keywords: Small GTPases, IRF3, TBK1, Small-scale library screen

INTRODUCTION

The innate immune response is a rapid cellular reaction to the detection of cytosolic nucleic acids. Activation of cytosolic nucleic acid sensors is important for host defense against viral infection. However, stimulation of these sensors through accumulation of self-nucleic acids may contribute to the pathogenesis of various diseases, including sterile inflammatory diseases such as alcoholic hepatitis and steatohepatitis (Xu et al., 2021). Cytosolic nucleic acid sensing is also known to play a role in physiological processes such as organ regeneration (Schulze et al., 2018). A major sensing mechanism of cytosolic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) is the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon gene (STING) pathway. When bound with dsDNA, cGAS produces 2’3’-cyclic GMA-AMP (cGAMP), a second messenger molecule, which activates STING (Ishikawa and Barber, 2008; Gao et al., 2013). Signaling through this pathway converges to the activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3).

Recent studies have identified IRF3 as a central regulator of non-immune mediated apoptosis (Chattopadhyay et al., 2010). IRF3 interacts with the pro-apoptotic protein Bax to induce the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Phosphorylation of IRF3 by STING/TBK1 activates apoptosis in association with Bax. IRF3 can also be activated by ER stress without the presence of invading foreign material such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), RNA, or DNA (Liu et al., 2012). Additionally, ER stress induced by ethanol intake has been shown to cause hepatocyte damage in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of IRF3 (Petrasek et al., 2013). While both obesity and diabetes can cause mitochondrial dysfunction and ER stress, studies have revealed a direct role of IRF3 in obesity and diabetes (Mao et al., 2017; Rizwan et al., 2020). Genetic ablation of IRF3 was shown to increase overnutrition-induced hepatic insulin resistance and glucose intolerance (Qiao et al., 2018). Another study showed that hepatic IRF3 activates PP2A through Ppp2r1b transactivation, leading to AMPK dephosphorylation, thereby promoting dysglycemia and insulin resistance (Patel et al., 2022). Thus, IRF3 is a significant factor in mediating not only the innate immune response but also in modulating signal transduction of local inflammatory responses.

IRF3 is a constitutively expressed transcription factor localized in the cytoplasm in its inactive form. Upon phosphorylation, it undergoes dimerization and translocation to the nucleus (Hiscott, 2007). In the nucleus, IRF3 cooperatively binds with other transcription factors, including nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), Activating Protein-1 (AP-1), and Interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) to form a multimolecular enhancer that promotes gene transcription. IRF3 can be phosphorylated via multiple pathways including the Toll-like receptors (TLR) signaling pathway, which recognizes pathogen-associated molecules such as LPS (Shinobu et al., 2002); the STING pathway, which recognizes cytoplasmic DNA (Ishikawa and Barber, 2008); and the RIG-1 pathway, which recognizes RNA (Yoneyama et al., 2004). Multiple serine and threonine residues in IRF3 can be regulated by several upstream kinases, the best-characterized among them being TBK1 (Fitzgerald et al., 2003). Most innate immune sensors phosphorylate IRF3 through TBK1. Nevertheless, IRF3 can also be regulated by other upstream kinases. IRF3 phosphorylation by JNK phosphorylates the N-terminal serine 173 residue, which differs from the TBK1-mediated phosphorylation site(s). JNK inhibition reduced the expression of IRF3 target genes such as Rantes and Interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) (Zhang et al., 2009). Other upstream kinases such as, c-Abl and c-Abl-related kinase (Arg), also phosphorylate IRF3 at the tyrosine 292 residue. A c-Abl inhibitor reduced the induction of IFNB by IRF3 (Luo et al., 2019). Thus, it is crucial to identify upstream signals that may enhance or repress IRF3 phosphorylation to regulate pathological outcomes caused by IRF3 dysregulation.

Over 150 small GTPases have been identified in humans, comprising five families: ARF, RHO, RAS, RAB, and RAN, based on similarities in their G domain sequences. Cytoplasmic small GTPases regulate a variety of cellular processes by altering their conformational forms. In their active form, small GTPases signal through effector proteins to regulate multiple cellular functions, such as cell proliferation, cell death, microtubule dynamics, vesicle transport, and protein transport between the nucleus and cytosol (Balch, 1990; Boman et al., 1992; Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002; Kahn et al., 2005; Hodge and Ridley, 2016). Aberrant Small GTPases are associated with a multiple of human diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammatory diseases. For instance, activating mutations of Ras subfamily proteins such as KRAS, HRAS, NRAS have been extensively studied as a driver mutation of tumor transformation in a vast majority of tissues (Punekar et al., 2022). In addition, role of KRAS has been implicated in inflammatory diseases including Rheumatoid arthritis (Singh et al., 2012). In Alzheimer’s disease, overactivation of RhoA leads to amyloid β production and accumulation by promoting secretase-dependent cleavage amyloid precursor protein (Guiler et al., 2021).

Some small GTPases have been reported to suppress innate immune responses. For instance, ARL5B and ARL16 inhibit RIG-I and MDA5, respectively, in the RNA-sensing RLR pathway and suppress the production of type I interferon against viral RNA sensing (Yang et al., 2011; Kitai et al., 2015). In contrast, some small GTPases activate innate immune responses. For example, RAB1B binds to TRAF3 to promote the formation of MAVS-TRAF2/3 complex, thereby facilitating innate immune response through TBK1-IRF3 signaling (Beachboard et al., 2019). Another small GTPase, RAB2B, forms a complex with GARIL5 to regulate the cGAS-STING signaling axis to promote IFN responses to DNA viruses (Takahama et al., 2017). Rac1 transactivates NF-κB during TLR2 stimulation upon bacterial invasion (Arbibe et al., 2000). RAB11a is also involved in the recruitment of TLR4 and TRAM to the phagosome during bacterial invasion and induces the expression of IFNB through IRF3 signaling (Husebye et al., 2010). Although several small GTPases are involved in innate immune responses, the link between small GTPases and IRF3 remains unknown.

Small GTPases utilize GDP/GTP alternation to actuate functional switches (Cherfils and Zeghouf, 2013). As they lie upstream in signal transduction pathways, GTPases only remain transiently active. In the basal state, small GTPases remain inactive in their GDP-bound conformation. After activation, they quickly return to an inactive state by intrinsic hydrolysis of GTP. Thus, overexpression of individual GTPases in an unedited form does not ensure proper screening validity. To investigate the role of small GTPase activation by ectopic expression, it is crucial to utilize constitutively active mutants by deleting the intrinsic GTPase domain, which lacks an autoinhibitory function. Attempts to comprehensively investigate the role of GTPases have been unsuccessful due to the need for labor- and time-intensive site-directed mutagenesis and the large number of homologous proteins. Here, we compared small GTPases in an unbiased manner using a small-scale constitutively active mutant expression library. We discovered multiple GTPases that increase IRF3 phosphorylation and investigated the sequence-activity relationship. In addition, our study revealed that the regulation of IRF3 by small GTPases is generally dependent on TBK1, emphasizing the role of the kinase in the link between GTPase signaling and innate immunity or other IRF3-mediated functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Active mutant expression library construction

The pRK7 vector (Addgene plasmid #10883) was modified to have a HA-tag on either N- or C-terminus of each gene to be cloned. The tagged empty vectors were then linearized with two different restriction enzymes. The small GTPase inserts were amplified using purified human cDNA which was obtained from HEK293 or MCF7 cell line according to respective mRNA abundance. To simultaneously introduce constitutively active mutation, each gene was amplified in two parts utilizing mutagenic primers on the joining side. Gibson assembly reactions were done at 50°C for 1 h using NEBuilder HiFi DNA assembly master mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). After purification, all resultant plasmids were further verified by Sanger sequencing. The introduced mutations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Amino acid residues with induced mutations in small GTPases

| Symbol | Mutation | Symbol | Mutation | Symbol | Mutation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arf subfamily | Rrad | P100V | Rab27A | Q78L | |||

| Arl3 | Q71L | Rem1 | P89V | Rab27B | Q78L | ||

| Arl2 | Q70L | Rem2 | Q173L | Rab28 | Q72L | ||

| Arf5 | Q71L | Diras1 | G16V | Rab30 | Q68L | ||

| Arf4 | Q71L | Diras2 | G16V | Rab32 | Q85L | ||

| Arf3 | Q71L | Diras3 | Q95L | Rab33A | Q95L | ||

| Arf1 | Q71L | RasD1 | S33V | Rab33B | Q92L | ||

| Arf6 | Q67L | RasD2 | S30V | Rab34 | Q111L | ||

| TRIM23 | K458I | RasL10B | I63L | Rab35 | Q67L | ||

| Arl1 | Q71L | RasL10A | P13V | Rab36 | Q182L | ||

| Arl5B | Q70L | NkiRas1 | WT | Rab37 | Q82L | ||

| Arl5A | Q70L | NkiRas2 | WT | Rab38 | Q69L | ||

| Arl14 | Q68L | Rab subfamily | Rab39A | Q72L | |||

| Arl11 | Q67L | Rab1A | Q70L | Rab39B | Q68L | ||

| Arl4A | Q79L | Rab1B | Q67L | Rab40A | Q73L | ||

| Arl4C | Q72L | Rab2A | Q65L | Rab40B | Q73L | ||

| Arl4D | Q80L | Rab2B | Q65L | Rab40C | Q73L | ||

| ArfRP1 | Q79L | Rab3A | Q81L | Rab41 | Q90L | ||

| Arl6 | Q73L | Rab3B | Q81L | Rab42 | H74L | ||

| Arl13B | G75L | Rab3C | Q89L | IFT27 | P14V | ||

| Sar1a | H79G | Rab3D | Q81L | RasEF | Q600L | ||

| Sar1b | H79G | Rab4A | Q72L | Rho subfamily | |||

| Arl15 | A86L | Rab4B | Q67L | Rac3 | Q61L | ||

| Arl16 | C86L | Rab5A | Q79L | Rac1 | Q61L | ||

| Arl8A | Q75L | Rab5B | Q79L | Rac2 | Q61L | ||

| Arl8B | Q75L | Rab5C | Q80L | RhoG | Q61L | ||

| Arl10 | S132L | Rab6A | Q72L | Cdc42 | Q61L | ||

| Arl9 | S9L | Rab6B | Q72L | RhoJ | Q79L | ||

| Ras subfamily | Rab6C | Q72L | RhoQ | Q67L | |||

| Rit1 | G30V | Rab7A | Q67L | RhoU | Q107L | ||

| Rit2 | G29V | Rab7B | Q67L | RhoV | Q89L | ||

| Rap2C | G12V | Rab7L1 | Q67L | RhoB | Q63L | ||

| Rap2A | G12V | Rab8A | Q67L | RhoC | Q63L | ||

| Rap2B | G12V | Rab8B | Q67L | RhoA | Q63L | ||

| Rap1B | G12V | Rab9A | Q66L | RhoF | Q77L | ||

| Rap1A | G12V | Rab9B | Q66L | RhoD | Q75L | ||

| Rras2 | G23V | Rab10 | Q68L | Rnd2 | WT | ||

| Rras | G38V | Rab11A | S20V | Rnd3 | WT | ||

| Mras | G22V | Rab11B | S20V | Rnd1 | WT | ||

| Kras | G12V | Rab12 | Q101L | RhoH | WT | ||

| Nras | G12V | Rab13 | Q67L | RhoBTB2 | WT | ||

| Hras | G12V | Rab14 | Q70L | RhoBTB1 | WT | ||

| RalB | G23V | Rab15 | Q67L | Ran/unclassified | |||

| RalA | G23V | Rab17 | Q77L | Ran | Q69L | ||

| Eras | Q99L | Rab18 | Q67L | IFT22 | C12V | ||

| RhebL1 | Q64L | Rab19 | Q76L | SRPRB | C73V | ||

| Rheb | Q64L | Rab21 | Q78L | RhoT1 | P13V | ||

| Rerg | Q64L | Rab22A | Q64L | RhoT2 | A13V | ||

| RasL12 | R29V | Rab22B | Q65L | RabL3 | S15V | ||

| RasL11A | G36V | Rab23 | Q68L | RabL2A | Q80L | ||

| RasL11B | S42V | Rab24 | S67L | RabL2B | Q80L | ||

| RergL | Q62L | Rab25 | S21V | Rab20 | R59L | ||

| Gem | Q84V | Rab26 | Q123L |

Cell culture, DNA transfection and treatment

HEK293 and MCF7 cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 ug/mL streptomycin Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. For DNA transfection, the cells were transfected with plasmids using PolyJet in vitro transfection reagent Signagen (Frederick, MD, USA) for 24-48 h according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-Flag (#F1804) and anti-vinculin (#V9131) antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Phos-tag acrylamide (#AAL-107) was from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA, USA). BX795 (#14932) was from Cayman (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Rapamycin (#5318893) was from Peprotech (East Windsor, NJ, USA).

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed with a denaturing buffer containing SDS and β-mercaptoethanol. After boiling for 5 min, proteins were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblotting was then performed using specific antibodies and the blots were further visualized by chemiluminescence using a digital imager. For phos-tag assay, 7.5% polyacrylamide gels were polymerized in presence of Phos-tag acrylamide and MnCl2. Phos-tag gels separate phosphorylated proteins non-specifically for serine, threonine, tyrosine, and histidine phosphorylation.

Phylogenetic tree construction

Protein sequences of small GTPases were obtained from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/). The sequences were compared using the Molecular Evolution Genetic Analysis (MEGA 11) software (https://www.megasoftware.net/) by multiple sequence alignment through ClustalW algorithm. The tree was constructed using maximum likelihood analysis. The confidence levels of nodes were tested by bootstrapping 100 times (Hillis and Bull, 1993).

Analysis of protein sequence identity and similarity

Sequence identities and similarities were calculated with Sequence Identities and Similarities (SIAS) software (http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/sias.html). For protein similarity calculation, all positively charged amino acids (Arg, Lys, and His), all negatively charged amino acids (Asp and Glu), and all aliphatic amino acids (Val, Iso, and Leu) were considered as respectively similar. Additionally, the aromatic amino acids Phe, Tyr, and Trp, the polar amino acids Asn and Gln, and the small amino acids Ala, Thr, and Ser were treated as similar, respectively. To calculate the normalized similarity score, the BLOSUM62 matrix was used.

RESULTS

Gibson assembly cloning enables efficient construction of an expression library comprising constitutively active mutant small GTPases

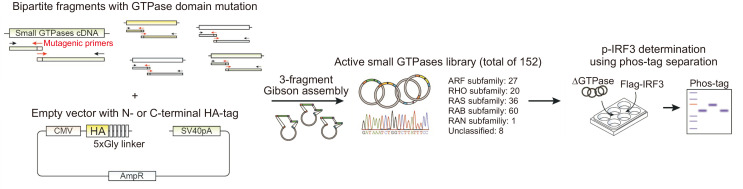

To investigate the role of small GTPases in IRF3 activation, we constructed an expression library comprising clones encoding individual GTPases with constitutively active mutations. Conventional site-directed mutagenesis is time- and labor-intensive and severely limits the number of constructed clones. Gibson assembly cloning using overlapping primers with variant sequences allowed us to directly clone active mutant small GTPases from wild-type cDNA (Fig. 1). Target mutation sequences were designed to ablate intrinsic GTPase activity and to increase affinity for GTP, based on previous reports and predictions according to their sequence homology with K-RAS (e.g., mutation of amino acid residues that correspond to G12 or Q61 in K-RAS). GTPases that are intrinsically deficient in GTP-hydrolyzing activity or constitutively bound to GTP were used in their native sequences (Table 1). Small GTPases were N-terminal HA-tagged as they generally undergo C-terminal isoprenylation. However, Arf GTPases were C-terminally HA-tagged because they are post-translationally modified by C-terminal myristoylation (Prakash and Gorfe, 2013). A library comprising of 152 expression clones encoding active mutant small GTPases was constructed and individually expressed with IRF3 for unbiased evaluation of their contribution to IRF3 signaling.

Fig. 1.

Construction of an expression library comprising constitutively active mutant small GTPases. Cloning scheme for the constitutively active mutant small GTPase library. Each GTPase was amplified into two fragments by using mutagenic primers in the GTPase domain. The PCR products were then fused to the linearized backbone vector with an HA-tag on either the N- or C-terminal side of the insert site simultaneously through 3-fragment Gibson assembly reaction.

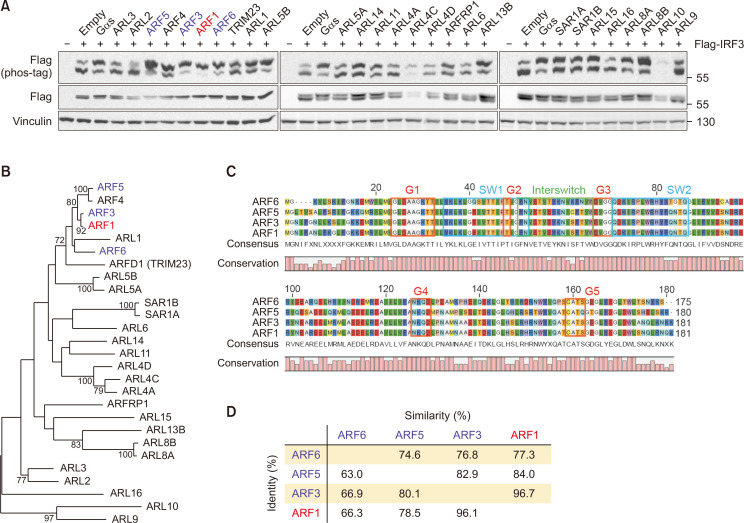

ARF1/3/5/6 increase IRF3 phosphorylation

The Arf family of GTPases regulates vesicular traffic and organelle structure. Recently, some members of the Arf protein family have been found to modulate molecular signaling pathways involving IRF3. For instance, ARF6 promotes IRF3 activation to induce IRF3-dependent genes that interfere with TLR4 signaling (Van Acker et al., 2014). However, the role of other Arf proteins in IRF3 signaling remains largely unknown. We examined whether Arf family proteins regulate IRF3 phosphorylation, which in turn activates the innate immune response. Phosphorylation of IRF3 was examined using a phos-tag gel after co-transfection with FLAG-IRF3 and individual Arf GTPases. Among the Arf subfamily members, ARF1 robustly increased the phosphorylation of IRF3, with almost no non-phosphorylated protein. Other proteins, such as ARF3, ARF5, and ARF6, also activated IRF3, as observed by IRF3 phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). We generated a phylogenetic tree to ascertain evolutionary redundancy among ARF proteins that positively regulate IRF3 phosphorylation. Of the 27 Arf subfamily genes, 4 genes that activate IRF3 share high protein sequence homology with shared amino acid sequences and domain structures (Fig. 2B). In particular, the ARF proteins that phosphorylated IRF3 shared a very high homology throughout the entire protein, suggesting that both the core G domain and other domains are responsible for IRF3 regulation. (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Fig. 1A). The two positive Arf protein sequences showed a 62-96% match with functional similarities such as serine and threonine amino acid matching of 74-96%, implying their structure-activity relationship. (Fig. 2D, Supplementary Fig. 1B) Our results showed that the control of IRF3 by these Arf proteins may be evolutionarily conserved.

Fig. 2.

ARF1/3/5/6 increases IRF3 phosphorylation. (A) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-IRF3 and individual Arf GTPases. 24 h post transfection, the migration shift of IRF3 was determined by phos-tag gel electrophoresis. Red, strong phosphorylation; blue, weak phosphorylation. (B) Phylogenetic comparison between Arf family proteins. The sequences were aligned using ClustalW. Horizontal distance represents the proportion of amino acid difference and the branch values denote the bootstrap confidence values. (C) Alignment of amino acid sequences for Arf GTPases that positively regulate IRF3 phosphorylation. Common domain structure of Arf GTPases is shown above. (D) Protein sequence identity among Arf GTPases that increase phosphorylation of IRF3. Identity, percentage of identical residues; similarities, percentage of similar functional residues.

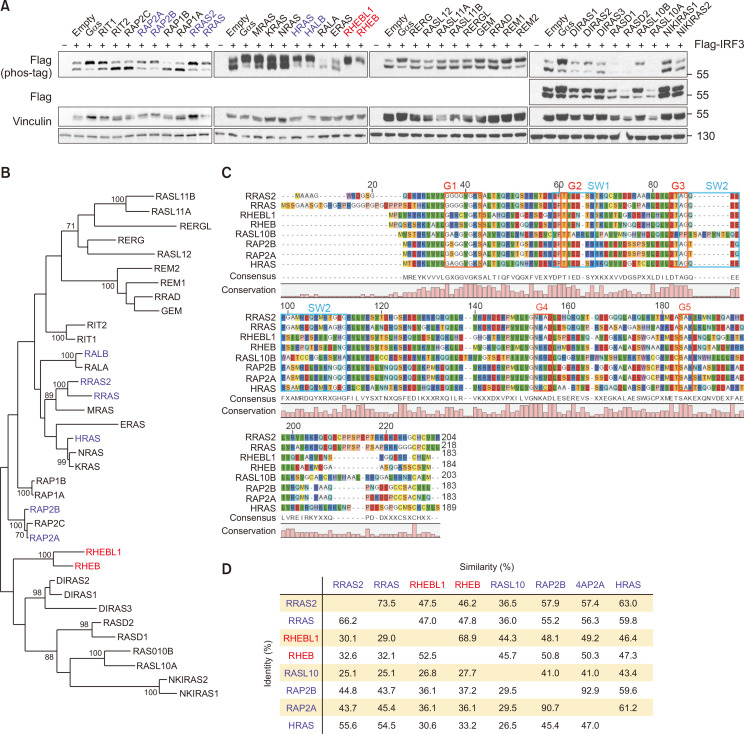

Multiple Ras proteins activate IRF3

The Ras subfamily of small GTPases is involved in cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. Recently, some members of the RAS family have been shown to modulate innate immune responses. For instance, knockdown of HRAS reduces virus-induced IRF3 phosphorylation, and RLR signaling is differentially propagated according to HRAS activity (Chen et al., 2017). Despite the various cellular functions modulated by Ras GTPases, information on the link between RAS GTPases and cytosolic DNA sensing is limited. Therefore, we examined the role of the Ras subfamily GTPases in IRF3 activation. The expression of individual Ras GTPases along with IRF3 and their parallel comparison enabled the identification of the members that control IRF3 signaling. Phos-tag analysis clearly showed that 9 out of 36 Ras subfamilies regulate IRF3 (Fig. 3A). Notably, the effects of RHEB and RHEBL1 were particularly robust. However, protein sequence comparison showed a lack of correlation between sequence homology and IRF3 phosphorylation activity, unlike the Arf GTPases (Fig. 3B). RHEB and RHEBL1 differ from other small Ras GTPases in their G1 domain sequence, which may contribute to their strong phosphorylation of IRF3. As expected, the overall sequence identity was as low as 25% among the positive hits, and the similarity varied from 35% to 92% (Fig. 3C, 3D). Our data suggest that specific functions exerted by RHEB and RHEBL1, such as controlling protein synthesis through mTOR regulation, may be related to IRF3 signaling and cytosolic DNA sensing.

Fig. 3.

Multiple Ras proteins activate IRF3. (A) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-IRF3 and individual Ras GTPases. 24 h post transfection, the migration shift of IRF3 was determined by Phos-tag gel electrophoresis. Red, strong phosphorylation; blue, weak phosphorylation. (B) Phylogenetic comparison between Ras family proteins. The sequences were aligned using ClustalW. Horizontal distance represents the proportion of amino acid difference and the branch values denote the bootstrap confidence values. (C) Alignment of amino acid sequences for Ras GTPases that positively regulate IRF3 phosphorylation. Common domain structure of Ras GTPases is shown above. (D) Protein sequence identity among Ras GTPases that increase phosphorylation of IRF3. Identity, percentage of identical residues; similarities, percentage of similar functional residues.

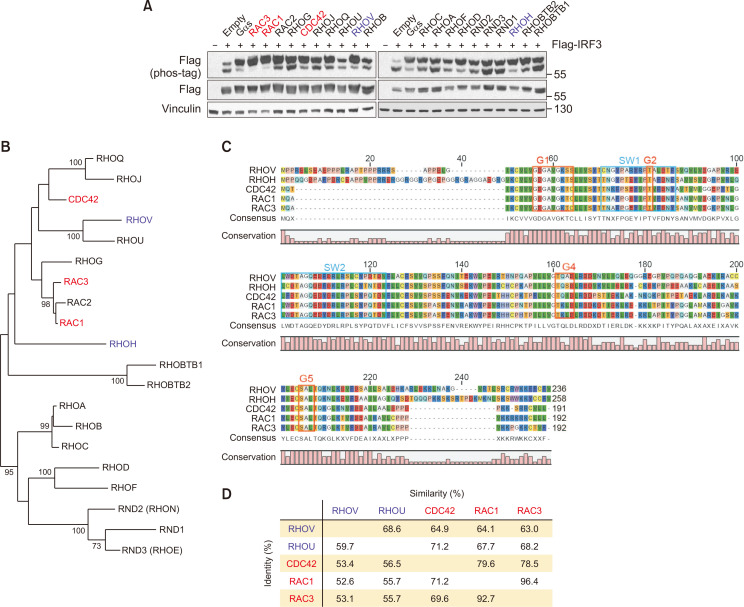

RAC1/3 and CDC42 phosphorylate IRF3

Rho GTPases are primarily responsible for regulating actin organization, cell morphology, and polarity. RAC1 is activated by viral infection, and inhibition of RAC1 reduces IRF3 phosphorylation and IFNB promoter activity (Ehrhardt et al., 2004). The link between other Rho GTPases and IRF3 has not yet been elucidated. We found that five out of 20 Rho GTPases, namely RAC1/3, CDC42, RHOH, and RHOV, upregulated phospho-IRF3 (Fig. 4A). The most robust signaling GTPases were RAC1/3 and CDC42, whereas most of the other RhoA-related proteins had little or no effect on IRF. Intriguingly, RHOH and RHOV, which possess higher sequence homology with RAC1/3 and CDC42 than RHOA, also had some effects on IRF3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4B). As expected, the five positive Rho GTPases were also similar in domain structure and amino acid sequences. The identity of the RHO proteins that phosphorylate IRF3 was approximately 52-92%, and the similarity was approximately 63-96% (Fig. 4C, 4D). It is noteworthy that RAC1/3 and CDC42 play a key role in the positive regulation of cell motility and protrusion, whereas RHOA and others similar members exert the opposite effect. Based on our observations, we hypothesize that cellular movement or actin polymerization may be closely linked to IRF3 signaling.

Fig. 4.

RAC1/3 and CDC42 phosphorylate IRF3. (A) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-IRF3 and individual Rho GTPases. 24 h post transfection, the migration shift of IRF3 was determined by Phos-tag gel electrophoresis. Red, strong phosphorylation; blue, weak phosphorylation. (B) Phylogenetic comparison between Rho family proteins. The sequences were multiply aligned by using ClustalW. Horizontal distance represents the proportion of amino acid difference and the branch values denote the bootstrap confidence values. (C) Alignment of amino acid sequences for Rho GTPases that positively regulate IRF3 phosphorylation. Common domain structure of Rho GTPases is shown above. (D) Protein sequence identity among Rho GTPases that increase phosphorylation of IRF3. Identity, percentage of identical residues; similarities, percentage of similar functional residues.

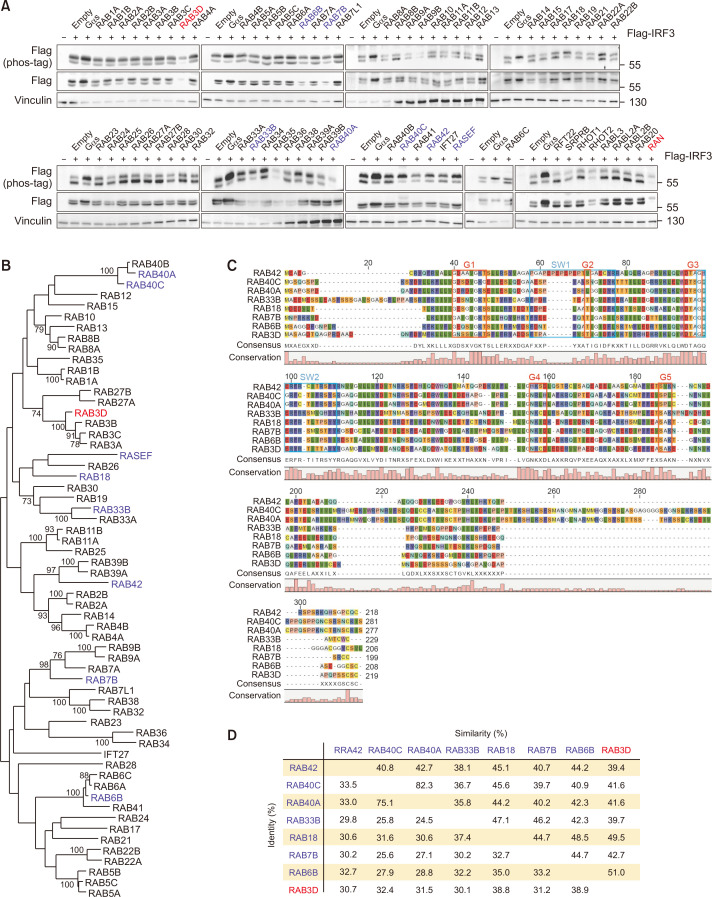

Multiple RAB GTPases and RAN stimulate IRF3 phosphorylation

Rab family G proteins control vesicular trafficking and endocytosis. Despite the large number of members, only RAB7 has been shown to block TBK1-mediated phosphorylation of IRF3 (Yang et al., 2016). Here, we examined the effects of the Rab subfamily and other unclassified GTPases, including RAN on IRF3 phosphorylation. We found that Rab GTPases, including RAB7, were less potent in phosphorylating IRF3, with the exception of RAB3D (Fig. 5A). Intriguingly, RAB3A/B/C, which share protein homology with RAB3D, did not show a similar effect (Fig. 5B-5D).

Fig. 5.

Multiple RAB GTPases and RAN stimulate IRF3 phosphorylation. (A) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-IRF3 and GTPases of Rab family, unclassified GTPases, or Ran. 24 h post transfection, the migration shift of IRF3 was determined by Phos-tag gel electrophoresis. Red, strong phosphorylation; blue, weak phosphorylation. (B) Phylogenetic comparison between Rab family proteins. The sequences were multiply aligned by using ClustalW. Horizontal distance represents the proportion of amino acid difference and the branch values denote the bootstrap confidence values. (C) Alignment of amino acid sequences for Rab GTPases that positively regulate IRF3 phosphorylation. Common domain structure of Rab GTPases is shown above. (D) Protein sequence identity among Rab GTPases that increase phosphorylation of IRF3. Identity, percentage of identical residues; similarities, percentage of similar functional residues.

Notably, RAN significantly increased IRF3 phosphorylation. Unlike other GTPases, RAN shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm to facilitate intracellular protein relocation. We speculate that at least one of the crucial upstream kinases of IRF3 is a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling kinase(s) that requires RAN in the cytoplasm.

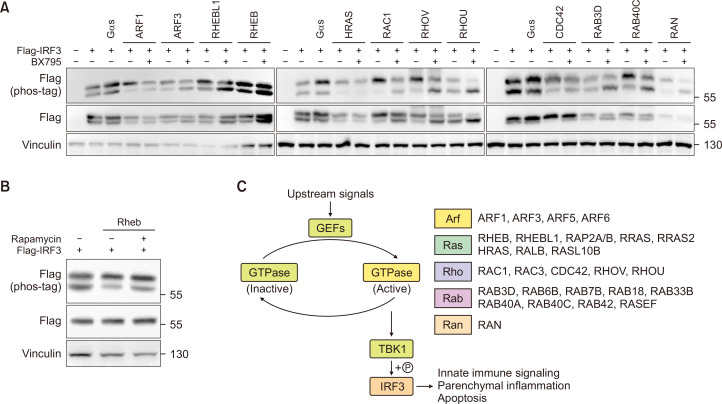

Most IRF3 phosphorylation by small GTPase overexpression occurs via TBK1

Next, we investigated whether TBK1 is required for small GTPase-mediated phosphorylation of IRF3 by using BX795, a well-known TBK1 inhibitor that inhibits of IRF3 phosphorylation (Fig. 6A). Surprisingly, every GTPases we have tested required TBK1 activity to regulate IRF3 except for Rheb/RhebL1. Although the contribution of TBK1 in the GTPase-mediated functional alterations is to be identified, the data clearly shows TBK1 as an important link between IRF3 and GTPase signaling. To identify how Rheb/RhebL1 can signal through IRF3, we have tested the role of mTOR on downstream IRF3 phosphorylation. Inhibition of mTOR by rapamycin partially diminished phosphorylation of IRF3 in cells overexpressed with constitutively active Rheb (Fig. 6B). In summary, we demonstrated that multiple small GTPases can phosphorylate IRF3, and the phosphorylation is largely dependent on TBK1 (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

IRF3 phosphorylation mediated by small GTPases require TBK1. (A) HEK293 cells were co-transfected with 0.2 µg of FLAG-IRF3 and 0.2 µg of GTPases, respectively. 24 h post transfection, the cells were treated with BX795 for 3 h. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with 0.2 µg of FLAG-IRF3 and 0.2 µg of HA-RHEB-Q64L or empty plasmid. 24 h post transfection, the cells were treated with Rapamycin or vehicle for 3 h. (C) Overall scheme of this study.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that (1) multiple small GTPases have the potential to phosphorylate and regulate IRF3; (2) this phosphorylation occurs through TBK1 and is inhibited by BX795; and (3) small GTPases that phosphorylate IRF3 showed protein domain homology in each GTPase family, with some phylogenetic distance.

Our study demonstrates that the small GTPase ARF1 is a potent inducer of IRF3 phosphorylation. A recent study demonstrated that cGAMP stimulation activated ARF1 by enhancing its binding to GGA3 (Gui et al., 2019). Thus, it is possible that ARF1 controls cytosolic DNA sensing in cells by controlling IRF3 phosphorylation. ARF1 expression is elevated in breast, colon/colorectal, gastric and liver cancers (Casalou et al., 2020). Since cytosolic DNA is significantly increased in cancer patients (Qin et al., 2016), this mechanism may play a role in cancer proliferation. Furthermore, the inhibition of IRF3 may provide a new therapeutic strategy to repress ARF1-mediated cancer proliferation.

We showed that nine out of 36 RAS small GTPases phosphorylate IRF3. Among these, RHEB and RHEBL1 were the strongest stimulators of IRF3. Rheb/RhebL1 are distinct from other RAS GTPases in their activation of mTOR, which is involved in cell proliferation, autophagy, and apoptosis. It has been recently reported that activation of mTOR complex has a potential to promote IRF3 nuclear translocation and target gene expression (Öhman et al., 2015; Bodur et al., 2018). Our data adds more value to these findings by suggesting Rheb as an important upstream mTOR regulator to control IRF3 activity. Rheb/RhebL1 act as cellular sensors of nutrients, energy levels, and growth factors (MacKeigan and Krueger, 2015). Our data expand the current knowledge that Rheb/RhebL1 may serve as an innate immunity trigger by integrating cellular inputs other than cytosolic DNA into the IRF3 transcriptome. For other Ras proteins that phosphorylate IRF3, the sequence homology is low. However, in spite of the low homology they converge on downstream signaling which involves RAF, MEK, ERK and others. Therefore, one of the signaling molecules commonly activated by RAS signaling might interact closely with IRF3.

Another key finding of our study was that the expression of mutant RAN activated IRF3. RAN shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm to facilitate the intracellular relocation of other proteins by binding to its cargo targets and importins and does not signal through downstream effectors (Stewart, 2007). After GDP-bound RAN translocates into the nucleus, Ran-GEF replaces RAN-bound GDP with GTP. GTP-bound RAN then shuttles back to the cytosol along with its cargo, translocating the target proteins from the nucleus. The mutant RAN from our expression library does not shuttle through the nuclear membrane since we induced mutations in the GTPase domain. It is designed to be cytosol-localized and thus inhibit nuclear trafficking of proteins. Therefore, our observation that mutant RAN increased IRF3 phosphorylation indicates the existence of crucial upstream regulator(s) of IRF3 that have RAN-dependent translocation between the cytosol and nucleus. Furthermore, IRF3 phosphorylation by mutant RAN was dependent on TBK1, as shown by the inhibition of phosphorylation after BX795 treatment. Since TBK1 is not nuclear-localized, our results warrant further investigation into the upstream regulator(s) of TBK1.

In summary, we have identified small GTPases that phosphorylate IRF3 in an unbiased manner for the first time and revealed a sequence-activity correlation followed by the identification of the necessity of TBK1 as a key link. IRF3 is an emerging target that integrates various cellular inputs. Therefore, our results warrant further studies to determine how a specific GTPase triggers IRF3 transcriptome changes and the involved cellular functions. Furthermore, since most small GTPases signal through TBK1 to phosphorylate IRF3, TBK1 inhibition may serve as a potential therapeutic strategy against diseases with GTPase overexpression or active mutations, such as neoplastic malignancies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Research Foundation of Korea grants funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (2021R1C1C1013323, 2021R1A4A5033289) as well as by the Creative-Pioneering Researchers Program and New Faculty Startup Fund from Seoul National University.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- Arbibe L., Mira J. P., Teusch N., Kline L., Guha M., Mackman N., Godowski P. J., Ulevitch R. J., Knaus U. G. Toll-like receptor 2-mediated NF-kappa B activation requires a Rac1-dependent pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:533–540. doi: 10.1038/82797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch W. E. Small GTP-binding proteins in vesicular transport. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1990;15:473–477. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90301-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beachboard D. C., Park M., Vijayan M., Snider D. L., Fernando D. J., Williams G. D., Stanley S., McFadden M. J., Horner S. M. The small GTPase RAB1B promotes antiviral innate immunity by interacting with TNF receptor-associated factor 3 (TRAF3) J. Biol. Chem. 2019;294:14231–14240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodur C., Kazyken D., Huang K., Ekim Ustunel B., Siroky K. A., Tooley A. S., Gonzalez I. E., Foley D. H., Acosta-Jaquez H. A., Barnes T. M., Steinl G. K., Cho K. W., Lumeng C. N., Riddle S. M., Myers M. G., Jr., Fingar D. C. The IKK-related kinase TBK1 activates mTORC1 directly in response to growth factors and innate immune agonists. EMBO J. 2018;37:19–38. doi: 10.15252/embj.201696164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boman A. L., Taylor T. C., Melançon P., Wilson K. L. A role for ADP-ribosylation factor in nuclear vesicle dynamics. Nature. 1992;358:512–514. doi: 10.1038/358512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalou C., Ferreira A., Barral D. C. The role of ARF family proteins and their regulators and effectors in cancer progression: a therapeutic perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8:217. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00217.7bca2cfc945b4115915af059694989c1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay S., Marques J. T., Yamashita M., Peters K. L., Smith K., Desai A., Williams B. R., Sen G. C. Viral apoptosis is induced by IRF-3-mediated activation of Bax. EMBO J. 2010;29:1762–1773. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. A., Lin Y. R., Chung H. T., Hwang L. H. H-Ras exerts opposing effects on type I interferon responses depending on its activation status. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:972. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherfils J., Zeghouf M. Regulation of small GTPases by GEFs, GAPs, and GDIs. Physiol. Rev. 2013;93:269–309. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt C., Kardinal C., Wurzer W. J., Wolff T., von Eichel-Streiber C., Pleschka S., Planz O., Ludwig S. Rac1 and PAK1 are upstream of IKK-epsilon and TBK-1 in the viral activation of interferon regulatory factor-3. FEBS Lett. 2004;567:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville S., Hall A. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature. 2002;420:629–635. doi: 10.1038/nature01148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald K. A., McWhirter S. M., Faia K. L., Rowe D. C., Latz E., Golenbock D. T., Coyle A. J., Liao S. M., Maniatis T. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:491–496. doi: 10.1038/ni921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P., Ascano M., Wu Y., Barchet W., Gaffney B. L., Zillinger T., Serganov A. A., Liu Y., Jones R. A., Hartmann G., Tuschl T., Patel D. J. Cyclic [G(2',5')pA(3',5')p] is the metazoan second messenger produced by DNA-activated cyclic GMP-AMP synthase. Cell. 2013;153:1094–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiler W., Koehler A., Boykin C., Lu Q. Pharmacological modulators of small GTPases of Rho family in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:661612. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.661612.c16c68c2904d47eab46eed448c2a3b31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui X., Yang H., Li T., Tan X., Shi P., Li M., Du F., Chen Z. J. Autophagy induction via STING trafficking is a primordial function of the cGAS pathway. Nature. 2019;567:262–266. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1006-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis D. M., Bull J. J. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Syst. Biol. 1993;42:182–192. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/42.2.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscott J. Triggering the innate antiviral response through IRF-3 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:15325–15329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge R. G., Ridley A. J. Regulating Rho GTPases and their regulators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016;17:496–510. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husebye H., Aune M. H., Stenvik J., Samstad E., Skjeldal F., Halaas O., Nilsen N. J., Stenmark H., Latz E., Lien E., Mollnes T. E., Bakke O., Espevik T. The Rab11a GTPase controls Toll-like receptor 4-induced activation of interferon regulatory factor-3 on phagosomes. Immunity. 2010;33:583–596. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa H., Barber G. N. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455:674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature07317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. A., Volpicelli-Daley L., Bowzard B., Shrivastava-Ranjan P., Li Y., Zhou C., Cunningham L. Arf family GTPases: roles in membrane traffic and microtubule dynamics. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:1269–1272. doi: 10.1042/BST0331269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitai Y., Takeuchi O., Kawasaki T., Ori D., Sueyoshi T., Murase M., Akira S., Kawai T. Negative regulation of melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5)-dependent antiviral innate immune responses by Arf-like protein 5B. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:1269–1280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.611053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. P., Zeng L., Tian A., Bomkamp A., Rivera D., Gutman D., Barber G. N., Olson J. K., Smith J. A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress regulates the innate immunity critical transcription factor IRF3. J. Immunol. 2012;189:4630–4639. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F., Liu H., Yang S., Fang Y., Zhao Z., Hu Y., Jin Y., Li P., Gao T., Cao C., Liu X. Nonreceptor tyrosine kinase c-Abl- and Arg-mediated IRF3 phosphorylation regulates innate immune responses by promoting type I IFN production. J. Immunol. 2019;202:2254–2265. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKeigan J. P., Krueger D. A. Differentiating the mTOR inhibitors everolimus and sirolimus in the treatment of tuberous sclerosis complex. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:1550–1559. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y., Luo W., Zhang L., Wu W., Yuan L., Xu H., Song J., Fujiwara K., Abe J. I., LeMaire S. A., Wang X. L., Shen Y. H. STING-IRF3 triggers endothelial inflammation in response to free fatty acid-induced mitochondrial damage in diet-induced obesity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017;37:920–929. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman T., Söderholm S., Paidikondala M., Lietzén N., Matikainen S., Nyman T. A. Phosphoproteome characterization reveals that Sendai virus infection activates mTOR signaling in human epithelial cells. Proteomics. 2015;15:2087–2097. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S. J., Liu N., Piaker S., Gulko A., Andrade M. L., Heyward F. D., Sermersheim T., Edinger N., Srinivasan H., Emont M. P., Westcott G. P., Luther J., Chung R. T., Yan S., Kumari M., Thomas R., Deleye Y., Tchernof A., White P. J., Baselli G. A., Meroni M., De Jesus D. F., Ahmad R., Kulkarni R. N., Valenti L., Tsai L., Rosen E. D. Hepatic IRF3 fuels dysglycemia in obesity through direct regulation of Ppp2r1b. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14:eabh3831. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abh3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrasek J., Iracheta-Vellve A., Csak T., Satishchandran A., Kodys K., Kurt-Jones E. A., Fitzgerald K. A., Szabo G. STING-IRF3 pathway links endoplasmic reticulum stress with hepatocyte apoptosis in early alcoholic liver disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013;110:16544–16549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308331110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash P., Gorfe A. A. Lessons from computer simulations of Ras proteins in solution and in membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1830:5211–5218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punekar S. R., Velcheti V., Neel B. G., Wong K. K. The current state of the art and future trends in RAS-targeted cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022;19:637–655. doi: 10.1038/s41571-022-00671-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao J. T., Cui C., Qing L., Wang L. S., He T. Y., Yan F., Liu F. Q., Shen Y. H., Hou X. G., Chen L. Activation of the STING-IRF3 pathway promotes hepatocyte inflammation, apoptosis and induces metabolic disorders in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2018;81:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z., Ljubimov V. A., Zhou C., Tong Y., Liang J. Cell-free circulating tumor DNA in cancer. Chin. J. Cancer. 2016;35:36. doi: 10.1186/s40880-016-0092-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizwan H., Pal S., Sabnam S., Pal A. High glucose augments ROS generation regulates mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis via stress signalling cascades in keratinocytes. Life Sci. 2020;241:117148. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.117148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze S., Stöß C., Lu M., Wang B., Laschinger M., Steiger K., Altmayr F., Friess H., Hartmann D., Holzmann B., Hüser N. Cytosolic nucleic acid sensors of the innate immune system promote liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:12271. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29924-3.e23109e2d28a4177896768238a57e86e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinobu N., Iwamura T., Yoneyama M., Yamaguchi K., Suhara W., Fukuhara Y., Amano F., Fujita T. Involvement of TIRAP/MAL in signaling for the activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 by lipopolysaccharide. FEBS Lett. 2002;517:251–256. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02636-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K., Deshpande P., Li G., Yu M., Pryshchep S., Cavanagh M., Weyand C. M., Goronzy J. J. K-RAS GTPase- and B-RAF kinase-mediated T-cell tolerance defects in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:E1629–E1637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117640109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M. Molecular mechanism of the nuclear protein import cycle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:195–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahama M., Fukuda M., Ohbayashi N., Kozaki T., Misawa T., Okamoto T., Matsuura Y., Akira S., Saitoh T. The RAB2B-GARIL5 complex promotes cytosolic DNA-induced innate immune responses. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2944–2954. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Acker T., Eyckerman S., Vande Walle L., Gerlo S., Goethals M., Lamkanfi M., Bovijn C., Tavernier J., Peelman F. The small GTPase Arf6 is essential for the Tram/Trif pathway in TLR4 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:1364–1376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.499194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Tian Y., Xia Q., Ke B. The cGAS-STING pathway: novel perspectives in liver diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:682736. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.682736.9b367c9b61704a1b8d4888ed7a6812a0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Imamura Y., Jenkins R. W., Cañadas I., Kitajima S., Aref A., Brannon A., Oki E., Castoreno A., Zhu Z., Thai T., Reibel J., Qian Z., Ogino S., Wong K. K., Baba H., Kimmelman A. C., Pasca Di Magliano M., Barbie D. A. Autophagy inhibition dysregulates TBK1 signaling and promotes pancreatic inflammation. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016;4:520–530. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. K., Qu H., Gao D., Di W., Chen H. W., Guo X., Zhai Z. H., Chen D. Y. ARF-like protein 16 (ARL16) inhibits RIG-I by binding with its C-terminal domain in a GTP-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:10568–10580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.206896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama M., Kikuchi M., Natsukawa T., Shinobu N., Imaizumi T., Miyagishi M., Taira K., Akira S., Fujita T. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:730–737. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Li M., Chen L., Yang K., Shan Y., Zhu L., Sun S., Li L., Wang C. The TAK1-JNK cascade is required for IRF3 function in the innate immune response. Cell Res. 2009;19:412–428. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.