Abstract

Background

Newborn infants undergoing therapeutic hypothermia (TH) are exposed to multiple painful and stressful procedures. The aim of this systematic review was to assess benefits and harms of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the management of pain and sedation in newborn infants undergoing TH for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.

Methods

We included randomized and observational studies reporting any intervention (either drugs or non-pharmacological interventions) to manage pain and sedation in newborn infants (> 33 weeks’ gestational age) undergoing TH. We included any dose, duration and route of administration. We also included any type and duration of non-pharmacological interventions. Our prespecified primary outcomes were analgesia and sedation assessed using validated pain scales in the neonatal population; circulatory instability; mortality to discharge; and neurodevelopmental disability. A systematic literature search was conducted in the PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, with no language restrictions. Included studies underwent risk-of-bias assessment (Cochrane risk-of-bias tool and ROBINS-I) and data extraction performed by two authors independently. The plan had been to use effect measures such as mean difference for continuous outcomes and risk ratio for dichotomous outcomes, however the included studies are presented in a narrative synthesis due to their paucity and heterogeneity.

Results

Ten studies involving 3551 infants were included—one trial and nine observational studies. Most studies examined the use of phenobarbital or other antiepileptic drugs with primary outcomes related to seizure activity. The single trial that was included compared pentoxifylline with placebo. Among the primary outcomes, six studies reported circulatory instability and five reported mortality to discharge without relevant differences; two studies reported on neurodevelopmental disability and one study reported on pain scale. Three studies were ongoing.

Conclusions

We found limited evidence to establish the benefits and harms of the interventions for the management of pain and sedation in newborn infants undergoing TH. Long-term outcomes were not reported. Given the very low certainty of evidence—due to imprecision of the estimates, inconsistency and limitations in study design (all nine observational studies with overall serious risk of bias)—for all outcomes, clinical trials are required to determine the most effective interventions in this population.

Systematic Review Registration

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42020205755.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40272-022-00546-7.

Key Points

| Despite therapeutic hypothermia in newborn infants being associated with stress and pain, there is a lack of studies investigating sedation and pain relief during this treatment. |

| More clinical trials are needed to determine the most effective intervention. |

Introduction

Three to five newborns out of 1000 births are affected by peripartum asphyxia followed by subsequent moderate to severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) [1, 2]. The risk for subsequent disabilities from the asphyxia is reduced when the infant is treated with therapeutic hypothermia (TH) [3, 4]. The treatment should be initiated as soon as possible within the first 6 h after birth and then maintained for 72 h [2]. Infants undergoing TH are subjected to intensive care including painful procedures [5] as well as the TH, which is also associated with pain and stress [6, 7]. Additionally, painful experiences during the newborn period can alter future pain responses [8] and can also impair the infants’ brain development [9]. Therefore, managing infants’ pain and stress during TH is of great importance.

By reducing the body’s temperature during TH, serum clearance of morphine, fentanyl and midazolam is prolonged [10]. TH also redistributes regional blood flow, impacting both drug distribution and clearance. It has also been associated with a decreased glomerular filtration rate in animal studies and may consequently decrease renal excretion of drugs in humans [11]. The effects of sedative and analgesic treatment during TH are unclear and since TH can affect pharmacokinetics [12] caution is often recommended. In addition, infants undergoing TH might suffer from hepatic and renal injuries due to the asphyxia further impacting the way the infant will metabolize the drugs [11]. Morphine, midazolam, and dexmedetomidine are examples of drugs that might be used during TH for pain relief and/or sedation [13]. In addition to pharmacological interventions of pain management, non-pharmacological interventions could be good additional options since they have no known adverse effects and also facilitate parental involvement in infants’ care [14].

In summary, pain needs to be managed in all patients, including newborn infants, and there is strong evidence of the negative short- and long-term effects of painful procedures in this population. Pain management and sedation of infants receiving TH has not been systematically assessed for best practice. A comprehensive synthesis is needed to determine the best available evidence on pain relief and sedation in infants treated with TH.

Methods

Review Question

The aim of this study was to assess the benefits and harms of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the management of pain and sedation in newborn infants undergoing TH for HIE. The protocol of the review was registered in PROSPERO and submitted for publication before performing the search and data collection [15, 16]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2 guidelines were used in preparing this article.

Study Selection

The study included randomized, quasi-randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized studies of intervention using any type of drug or any type of non-pharmacological intervention used for the management of pain and/or sedation during TH. Crossover and cluster-randomized trials were excluded.

Primary Outcomes

The four primary outcomes were (1) analgesia and sedation assessed using validated pain scales in the neonatal population (the Echelle Douleur Inconfort Nouveau-ne [EDIN] scale, the COMFORTneo, Faces Pain Scale-revised, the Neonatal Pain, Agitation and Sedation scale [N-PASS], Pain Assessment Tool, the Astrid Lindgren and Lund Children’s Hospital’s Pain and Stress Assessment Scale for Preterm and Sick Newborn Infants [ALPS-neo], the Neonatal Facial Coding system [NFCS], and the Crying, Requires oxygen, Increased vital signs, Expression, Sleepless [CRIES] scale); (2) circulatory instability in the 12 h following the initiation of the intervention; (3) mortality to discharge; and (4) neurodevelopmental disability, defined as a composite outcome of cerebral palsy, developmental delay (Bayley Scales of Infant Development-Mental Development Index Edition II [BSID-MDIII]; Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development—Edition III Cognitive Scale [BSITD-III] or Griffiths Mental Development Scale—General Cognitive Index (GCI) assessment greater than two standard deviations [SDs] below the mean); intellectual impairment (intelligence quotient [IQ] greater than two SDs below the mean); and blindness (vision less than 6/60 in both eyes) or sensorineural deafness requiring amplification [4].

Secondary Outcomes

The secondary outcomes were neonatal mortality; duration of hospital stay; days to reach full enteral feeding; analgesia assessed with neurophysiological measures such as near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) or galvanic skin response (GSR); focal gastrointestinal perforation; episodes of bradycardia; signs of distress, e.g. heart rate > 100 beats/min, or as reported by study authors, and each of the components of the primary outcome ‘moderate-to-severe neurodevelopmental disability’.

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted using the following databases: PubMed, Embase, CINAHLComplete, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus, and Web of Science. Ongoing studies were searched for in ClinicalTrials.gov (see Appendix 1 for the full search history). Studies were included regardless of language, publication date, or publication status. We checked the reference lists of the included studies. The search strategy was run on January 2021.

Data Extraction and Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Two independent researchers screened the titles and abstracts followed by full-text screening using an online tool for the preparation of systematic reviews [17]. Disagreements were solved by a third researcher or through discussion within the group. Two researchers independently performed data extraction and assessed the included studies for risk of bias. For the assessment of risk of bias in the RCTs and observational studies, the Cochrane ‘Risk of Bias’ tool [18] and ‘Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions’ (ROBINS-I) tool [19] were used, respectively. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the researchers.

Measures of Treatment Effect

The plan was to summarize data in a meta-analysis if they were sufficiently homogeneous, both clinically and statistically. For dichotomous data, we planned to present results using risk ratios (RRs), odds ratios (ORs) and risk differences (RDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous data, we planned to use the mean difference (MD) when outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to report outcome data in tables if meta-analysis is deemed not appropriate, for example because of clinical or statistical heterogeneity.

Dealing with Missing Data, Assessment of Heterogeneity and Subgroup Analysis

Planned methods are reported in the review protocol but are not reproduced here as meta-analysis was deemed not appropriate [15, 16].

Results

Search Results

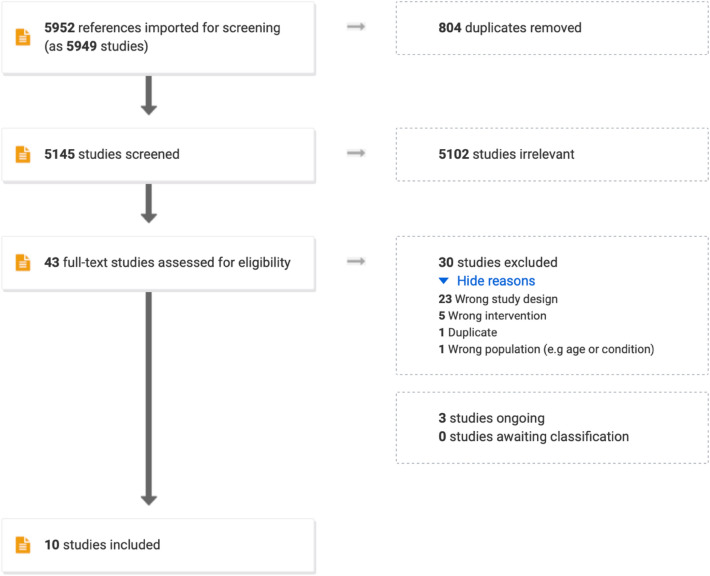

In total, 5145 studies were screened for title and abstract, of which 5102 were deemed irrelevant (Fig. 1). The remaining 43 studies were read in full text and 30 were excluded, leaving 10 studies to be included (one RCT and nine observational studies) (Table 1) and three ongoing studies (two RCTs and one observational study) (Table 2). Meta-analysis was deemed not feasible due to the heterogeneity among the included studies.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

Table 1.

Overview of the included studies

| Author, year Country |

Study design | Sample size | GA, weeks | Interventions | Primary objective | Inclusion criteria | Type of TH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abo Shady, 2018a [21] Egypt |

RCT | 20 | >36 | Pentoxifylline vs. placebo | Clinical and oxidative stress | GA > 36 weeks, diagnosed with HIE (12 severe and 8 moderate HIE) | NR |

|

O’Mara, 2018 [20] USA |

NRS | 19 | 38.5 ± 1.39 | DEX (all infants [n = 19] received DEX; 17 also received fentanyl) | Effectiveness and short-term safety | HIE requiring TH and received intravenous DEX within 48 h of birth | NR |

|

Favié, 2019 [24] The Netherlands |

NRS | 231 |

PB 39.8 ± 1.7 MID+PB 40.2 ± 1.4 MID 39.8 ± 1.6 |

PB and/or MID | Pharmacokinetics; clinical antiepileptic effectiveness; to develop dosing guidelines | Infants treated with TH and receiving MID and/or PB were included | NR |

|

Meyn, 2010 [25] USA |

NRS | 42 |

PB+TH: 38 ± 1 TH: 38 ± 2 |

PB | Moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment or death | All infants who received whole-body HT for HIE were included | WBC |

|

Sant’Anna, 2012 [26] Canada |

NRS | 98 |

PB: 39.0 ± 1.5 No PB: 39.1 ± 1.7 |

PB | Esophageal temperature profile during the induction phase of TH | Infants who underwent TH were grouped according to administration of PB before initiation of TH or not | WBC |

|

Sarkar, 2012 [30] USA |

NRS | 68 |

PB: 38.7 ± 1.6 No PB: 38.8 ± 1.7 |

PB | Short-term neuroprotection | Asphyxiated newborns ≥ 36 weeks who received TH for moderate (Sarnat stage 2) or severe (Sarnat stage 3) HIE | WBC or SHC |

|

Rao, 2018 [27] USA |

NRS | 78 |

PWS: 39.0 (37.9–39.7) #, PB first: 38.7 (38.0–39.7)#, LEV first: 39.0 (37.5–40.4)# |

PB and/or LEV | First-line treatment of neonatal seizures | Retrospectively identified infants with mild to severe HIE | WBC or SHC |

|

Surkov, 2021 [29] Ukraine |

NRS | 205 |

DEX: 39.6 ± 1.2 [36–42]## Standard sedation: 39.6 ± 1.5 [36–42]## |

DEX (n = 46) or standard sedation (n = 159; morphine, sodium oxybutyrate, and diazepam) | Cerebral blood flow and clinical outcomes | GA 37–42 weeks, signs and symptoms of moderate to severe HIE by Sarnat score during the first 72 h of life | NR |

|

Liow, 2020 [23] UK |

NRS | 169 |

Morphine: 39.9 ± 1.5 No morphine 39.7 ± 1.2 |

Morphine | Association of morphine infusion on brain injury and neurodevelopmental outcomes | Infants with moderate or severe encephalopathy | NR |

|

Berube, 2020 [28] USA |

NRS | 2621 | 39 (37–40)# | Unexposed (n = 714), opioids (n = 625), BA (n = 230), opioids and BA (n = 1052) | Mapping the use of sedatives and analgesics during TH among centers; associations between medication exposure and hospital outcome | All infants GA ≥ 35 weeks who were discharged from 125 neonatal intensive care units and who were treated with TH beginning on postnatal day 0 or 1 | NR |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise stated

BA benzodiazepine, DEX dexmedetomidine, GA gestational age, HIE hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, LEV levetiracetam, MD median, MID midazolam, NR not reported, NRS non-randomized study, PB phenobarbital, PWS patients without seizures, RCT randomized controlled trial, SHC selective head cooling, TH therapeutic hypothermia, WBC whole-body cooling

aConference abstract

#Median (interquartile range)

##min-max

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included ongoing studies

| Study registration no, year | Study design | Contact information Country | Planned no. of participants | Planned interventions | Planned outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT03837717, 2019 | RCT |

Alexa Craig (craiga@mmc.org) USA |

N = 34 > 35 weeks |

30 min maternal holding vs. no holding |

Primary 1. Change in the level of oxytocin in maternal saliva Secondary 1. Change in the level of cortisol in maternal saliva 2. Change in the level of oxytocin and cortisol in infant saliva 3. Comparison of infant temperature, heart rate, blood pressure and oxygen saturation before, during, and after holding 7. Subjective maternal and nurse reports |

| EUCTR2016‐000936‐17‐ES, 2019 | RCT |

info@gwpharm.com UK |

N = 32 > 36 weeks |

Cannabidiol vs. placebo |

Primary The safety and tolerability profile of a single intravenous dose of GWP42003-P, compared with placebo, will be assessed through monitoring of the following: Frequency, type, and severity of adverse events up to 30 days of life Mortality rate up to 30 days of life Clinically significant changes in the following, up to discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit: Laboratory parameters Cardiorespiratory monitoring Vital signs Secondary The plasma PK of CBD will be investigated. Plasma PK parameters will be determined using a population-based approach with sparse sampling |

| NCT03177980, 2017 | NRS |

Elisabeth Norman (elisabeth.norman@med.lu.se) Sweden |

N = 50 ≥ 36 + 0 weeks |

Fentanyl or fentanyl and clonidine Observational study, drugs administered according to clinical guidelines |

Primary PK of fentanyl and clonidine, neurophysiologic response; by single cortical events and their dynamics in relation to PK, neurophysiologic response; longer-term brain function in relation to PK, neurophysiologic response; global brain network function in relation to PK Secondary Change in/association between physiological parameters in relation to PK parameters. Change in pain responses as measured by pain assessment score for continuous pain/stress in relation to PK, procedural pain response at a short standardized pain stimulation; as assessed with change in galvanic skin response, change in serum-cortisol and scored by a procedural pain assessment scale (PIPP-R) in relation to PK. Pharmacogenetic profile in relation to PK and PD results; how PK/PD phenotypes depend on pharmacogenetic profiles |

PK pharmacokinetics, CBD cannabidiol, PD pharmacodynamic

Non-Pharmacological Interventions

Only 1 of the 13 studies assessed a non-pharmacological intervention, i.e. maternal holding (NCT038377172019).

Pharmacological Interventions

Most of the included studies examined the use of phenobarbital or other antiepileptic drugs with primary outcomes related to seizure activity. Only one study [20] and one of the ongoing studies (NCT03177980) used a pain/sedation scale as an outcome. Sample sizes in the included studies varied between 19 and 2621; the studies were conducted in the US (n = 5), Canada (n = 1), Egypt (n = 1), The Netherlands (n = 1), Ukraine (n = 1) and the UK (n = 1). Table 3 presents the outcomes of the included studies. The RCT by Shady et al. [21] compared pentoxifylline with placebo in a group of 20 infants, while the study by Surkov and colleagues [22] (described as a randomized trial in 2019; correction in 2021 reporting that it was an observational study) compared dexmedetomidine with the control group, in which morphine, sodium oxybutyrate, and diazepam were also used. Liow et al. [23] compared the use of pre-emptive morphine with no morphine. O’Mara et al. [20] also use dexmedetomidine in their study, although there was no control group and 17/19 infants also received fentanyl as co-intervention. Favié et al. [24] included infants who were divided into three groups according to the treatment received: phenobarbital alone, phenobarbital with midazolam, or midazolam alone. Meyn et al. [25] used prophylactic phenobarbital and compared it with TH itself. Similarly, Sant’Anna et al. [26] compared phenobarbital prior to TH with TH itself. Rao et al. [27] assessed the first-line treatment of neonatal seizures comparing phenobarbital used first or levetiracetam used first. Berube et al. [28] published an analysis of 2621 infants divided into four groups: unexposed, exposed to opioids, exposed to benzodiazepines, or exposed to both opioids and benzodiazepines.

Table 3.

Outcomes of the included studies

| Author, year Country |

Primary outcomes of the review | Secondary outcomes of the review | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain/sedation assessment | Circulatory instability | Mortality to discharge | Neurodevelop-mental disability | Composite outcome mortality or disability | Episodes of bradycardia | Seizures | |

|

Abo Shady, 2018a [21] Egypt |

NR | NR | Mortality in the hypothermia group was double the pentoxifylline/hypothermia group. Numbers NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

O’Mara, 2018 [20] USA |

N-PASS | No events following drug administration | 1 | NR | NR | HR instability in one patient (68 bpm) that resolved upon weaning the fentanyl infusion (and maintaining the DEX dose) | 8/19 |

|

Favié, 2019 [24] The Netherlands |

NR | NR | PB: 32, M:1, M+PB: 27 (unclear which time window) | NR | NR | NR | Seizure control with PB monotherapy in 74 patients (65.5%). 35 infants received MID as second-line antiepileptic treatment; of these, 22 (62.9%) received third-line treatment with lidocaine, levetiracetam, and/or clonazepam |

|

Meyn, 2010 [25] USA |

NR | NR | PB: 0; control: 3 (unclear which time window) | Death or moderate to severe neurodevelopmental impairment PB: 4; control; 9 | PB: 4; control: 9 | NR |

PB: 3/20 Control: 18/22 |

|

Sant’Anna, 2012 [26] Canada |

NR | Hypotension requiring medical therapy: PB: 17, no PB: 16 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

PB: 35/44 infants Control: 8/54 |

|

Sarkar, 2012 [30] USA |

NR | NR |

PB: 6 (17%) No PB: 4 (12%) |

NR | NR | NR |

PB: 34/36 infants Control: 1/32. Infants (n = 10) who received PB for clinical seizures developing after the initiation of TH were excluded |

|

Rao, 2018 [27] USA |

NR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (chest compressions and/or use of inotropic agents): PWS: 18 (52.9%); PB: 16 (66.7%); LEV: 13 (65.0%) | Patients without seizures 6 (17.6%); PB first 9 (37.5%); LEV first 1 (5.0%) | NR | NR | NR | 44/78 infants had seizures; of these infants, the 20 infants receiving LEV were seizure-free earlier than those 24 instances receiving PB |

|

Surkov, 2021 [29] Ukraine |

NR |

DEX group: higher mean blood pressure (p < 0.001); lower doses of dobutamine (EV − 1.87; 95% CI − 3.25 to − 0.48, p = 0.009) |

NR | NR | NR | No events of bradycardia |

Day 1, DEX: 2/46 Standard sedation: 77/159 (p < 0.001) |

|

Liow, 2020 [23] UK |

NR | NR | NR | Adverse neurological outcomes: morphine group: 125; no sedation: 17 |

Morphine group: 26 (18%) Control: None |

NR |

Morphine: 79/141 Control: 10/28 |

|

Berube, 2020 [28] USA |

NR | Hypotension requiring medical therapy: n = 257 (UE), n = 285 (OA), n = 92 (BA), n = 599 (O+B) | Mortality day 0–3 was lower among opioid-exposed neonates (31/625 [5%]) than unexposed neonates (64/714 [9%]). Mortality to discharge: opioid-exposed neonates (59/625 [10%]); unexposed neonates (110/714 [18%]) | NR | NR | NR | Infants receiving anticonvulsants: 331/714 infants in the group unexposed; 281/625 in the opioids group; 132/230 in the BA group; 452/1052 in the opioids and BA group |

BA benzodiazepine, bpm beats per min, DEX dexmedetomidine, EV expected value, HR heart rate, LEV levetiracetam, MID midazolam, N-PASS Neonatal Pain, Agitation and Sedation Scale, NR not reported, OA opioids, PB phenobarbital, PWS patients without seizures, TH therapeutic hypothermia, UE unexposed

aConference abstract

Primary Outcomes

Among the four primary outcomes of this review, five studies reported on circulatory instability and mortality to discharge, two studies reported on neurodevelopmental disability, and one study reported on pain scale. Primary and secondary outcome data are reported in Table 3.

Regarding circulatory instability, one study showed a decrease in the need for dobutamine [22], three studies found no difference in the use of vasopressors [20, 26, 27], while Berube et al. [28] showed that more infants receiving opioids alone or in combination with benzodiazepines required inotropic support than infants unexposed to those drugs.

Mortality to discharge was shown to be reduced in infants receiving treatment in three of the studies [21, 25, 28]. In the study by Rao et al. [27], infants who received phenobarbital first had a significantly higher mortality than infants who received levetiracetam first. In the study by Favié et al. [24], mortality (unclear whether the timeframe was until discharge) was reported as 28.3%, 39.7%, and 2.0% for infants receiving phenobarbital, phenobarbital+midazolam and midazolam, respectively. In the study by O’Mara [20], one patient died but it is unclear if the patient was in the dexmedetomidine and fentanyl group or in the dexmedetomidine-alone group.

Risk-of-Bias Within Studies

Details of our risk-of-bias assessments for randomized and non-randomized studies are presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. All of the included non-randomized studies were assessed with serious risk of bias, except one with critical risk of bias [22], due to critical bias in the classification of interventions. This study by Surkov et al., when published in 2019, was described as a randomized trial; however, in 2021 a correction was published to clarify that it was an observational study [29]. The study by O’Mara et al. [20] was assessed to have serious risk of bias due to the use of drugs that depend on the clinical stage of the infant and severity of HIE, and the relatively long period of data collection. Similarly assessed were the studies by Favié et al. [24] and Liow et al. [23], where the need for sedation and antiepileptic drugs might have been affected by the severity of HIE. The study by Sant’Anna et al. [26] was assessed with serious risk of bias because the initiation of treatment was started before the TH, that might have influenced the outcome. The study by Meyn et al. [25] had a very long data collection period and for that was assessed with serious risk of bias as the different experience of the team might have affected the outcome. For the studies by Sarkar et al. [30] and Rao et al. [27], the serious risk of bias comes from a long period of data collection followed by two different cooling methods used during the study period. The study by Berube et al. [28] was assessed to have serious risk of bias because data were collected during a long study period complicated by different practices in the participating centers.

Table 4.

Risk of bias for the included randomized controlled trial

| Bias | Abo Shady 2018a Egypt |

|---|---|

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | |

| Authors’ judgment | Unclear risk |

| Support for judgment | Not reported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | |

| Authors’ judgment | Unclear risk |

| Support for judgment | Not reported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | |

| Authors’ judgment | Unclear risk |

| Support for judgment | Not reported |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | |

| Authors’ judgment | Unclear risk |

| Support for judgment | Not reported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | |

| Authors’ judgment | Low risk |

| Support for judgement | Outcomes for all infants seem to be reported |

| Selective reporting | |

| Authors’ judgment | Unclear risk |

| Support for judgement | Protocol not available |

| Other bias | |

| Authors’ judgment | Unclear risk |

| Support for judgement | Conference abstract, very sparse information about the study |

aConference abstract

Table 5.

Risk of bias for the included non-randomized studies

| Domain/study | O’Mara, 2018 [20] | Sant’Anna, 2012 [26] | Favié, 2019 [24] | Meyn, 2010 [25] | Sarkar, 2012 [30] | Rao, 2018 [27] | Liow, 2020 [23] | Berube, 2020 [28] | Surkov, 2021 [29] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | |||||||||

| Bias due to confounding | Serious A | Serious H | Serious N | Serious U | Serious AA | Serious AE | Serious AI | Serious AO | Critical AT |

| Bias in the selection of participants into the study | Low B | Low I | Low O | Low B | Low B | Low B | Low I | Low I | Low B |

| At intervention | |||||||||

| Bias in the classification of interventions | Low C | Moderate K | Moderate P | Moderate W | Moderate AB | Moderate AF | Moderate AK | Serious AP | Critical AU |

| Post-intervention | |||||||||

| Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Moderate D | Moderate L | Moderate R | Moderate X | Moderate AC | Serious AG | Moderate AL | Moderate AR | Moderate AW |

| Bias due to missing data | Low E | Low E | Moderate S | Low Y | Low E | Low E | Low AM | Low E | No information |

| Bias in measurement of our primary outcomes |

Mortality: low Circulatory instability defined as hypotension requiring medical therapy: low F |

Circulatory instability (use of vasopressors): low M | Mortality: low T |

Mortality: low Death or moderate to severe NDI at > 18 months Z |

Mortality: low Circulatory instability: no information AD |

Mortality: low Circulatory instability: no information AH |

Mortality: low Neurodevelopmental follow up: low AN |

Mortality: low AS | Mortality: low T |

| Bias in the selection of the reported results | Low G | Low G | Low G | Low G | Low G | Low G | Low G | Low G | Serious AX |

| Overall bias | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | Serious | Critical |

A The need for sedation in an infant undergoing TH might depend on the severity of HIE; the use of DEX or fentanyl depends on the clinical state of the baby and therefore affects the outcome; data were collected for 3 years

B Inclusion and exclusion criteria are clearly predefined

C Interventions are well defined

D The co-intervention (fentanyl administered to 17/19 participants) is likely to affect the outcomes and is not balanced within the intervention group

E Data are available for all study participants

F Mortality: the outcome assessor judgment is negligible; circulatory instability defined as hypotension requiring medical therapy: the outcome assessor judgment is negligible

G Reported results seem to be complete

H The initiation of phenobarbital before TH could influence the outcome

I Inclusion criteria are predefined

K The intervention (drug administration) has no predefined criteria, it is unclear how the decision was made

L All infants received the intended intervention but neither the dose nor administration scheme are reported

M Circulatory instability: the outcome assessor judgment is negligible

N The need for sedation or antiepileptic drugs in the infant might depend on the severity of HIE

O Inclusion and exclusion criteria are clearly predefined (in the original article they refer to)

P Decision on dosing was made by the respective physician; large variety of doses

R Co-intervention with midazolam, lidocaine, levetiracetam and/or clonazepam could influence effects

S Data are available for the study participants who received PB but unclear how many there were from the beginning

T Mortality: the outcome assessor judgment is negligible

U Data were collected between 1999 and 2007, hence the experience of the team in performing TH might have changed during this time

W Decision to administer PB was up to the physician

X Both groups received PB but lower doses in the ‘nonprophylactic PB’ group, and no EEG was performed

Y Data are available for nearly all study participants, > 90% of population studied were included in the follow-up analysis

Z Mortality: the outcome assessor judgment is negligible; death or moderate to severe NDI at > 18 months: the outcomes assessors were blinded to the treatment

AA Data were collected between 2003 and 2009, and two different methods of cooling were used; the experience of the team in performing TH might have changed during this time

AB It is not defined how the infants receiving prophylactic PB were chosen

AC One infant received another drug (midazolam) and two infants received prophylactic phenobarbital (without clinical seizures). The PB group is unspecified (prophylactic/for clinical seizures vs. before TH/during TH)

AD Mortality: the outcome assessor judgment is negligible; circulatory instability: not defined or reported

AE Data were collected between 2008 and 2014, and two different methods of cooling were used because of the change in the NICU's practice; the experience of the team in performing TH might have changed during this time

AF The decision of the attending neonatologist or neurologist determined which intervention was given; in the center there are diverse approaches to treatment neonatal seizures

AG The study does not evaluate the antiepileptic drugs of third-line and beyond (if administrated). There were deviations from usual practice that were unbalanced between the intervention groups and likely to have affected the outcome (the HIE severity score was higher in the PB-first group)

AH Mortality: the outcome assessor judgment is negligible; circulatory instability: not defined or reported

AI The need for sedation or antiepileptic drugs in the infant might depend on the severity of HIE, secondary analysis of data

AK The decision of the attending neonatologist determined if the intervention was given; the use of morphine was not standardized, no information about the dose and duration of treatment is not available, no pain or sedation score was assessed

AL All infants received the intended intervention but neither the dose nor administration scheme are reported

AM Data are available for >90% of infants included

AN Mortality: the outcome assessor judgment is negligible; neurodevelopmental follow up: the outcome assessors were blinded

AO Data were collected between 2007 and 2015; the experience of the teams in performing TH might have changed during this time and the study includes data from many centers with different practices

AP The decision of the attending neonatologist determined which intervention was given; lack of medication indication data, no dosage information; differences between centers—lack of guidelines

AR All infants received the intended intervention but neither the dose nor administration scheme are reported

AS Reported results seems to be complete

AT The study was reported as an RCT but is observational study

AU Major aspects of the assignments of intervention status were determined in a way that could have been affected by knowledge of the outcome. We do not know how the intervention was applied to the study subjects

AW The participants seem to adhere to the interventions assigned, although there were deviations from usual practice that were unbalanced between the intervention groups and were likely to have affected the outcome

AX No protocol was published

DEX dexmedetomidine, EEG electrocardiogram, HIE hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, NDI neurodevelopment impairment, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, PB phenobarbital, RCT randomized controlled trial, TH therapeutic hypothermia

Discussion

Even though TH is an evidence-based treatment that has been available since 2006 [31], consensus and guidelines regarding appropriate analgesia and/or sedation are lacking. It is reasonable to assume the already injured asphyxiated brain would benefit from minimizing pain and stress, which are known to have negative consequences during TH, and avoiding the potential negative adverse effects from pharmacological treatments. A balanced treatment is desirable and ethically required [32, 33].

This systematic review included 10 studies on pharmacological interventions highlighting the extreme paucity of studies assessing pain and sedation management during neonatal TH. The clinical heterogenity of the included studies, e.g. different settings, comparisons, and outcomes, does not allow to draw any conclusion on the safety and efficacy of these interventions. Most of the studies examined the use of antiepileptic drugs on primary outcomes related to seizure activity; none of the included RCTs had pain relief or sedation as the primary outcome. There is a possibility that drugs primarily used for managing seizures such as phenobarbital affects infants in a way that could be interpreted as pain relieving. However, the area of use for phenobarbital is mainly antiepileptic. Certainty of the evidence is very low for all outcomes due to the imprecision of the estimates, inconsistency, and study limitations. One study [22] was listed as an RCT but after corresponding with the study author, it was clarified that it was an observational study and the manuscript was republished [29].

Previous studies have shown that TH seems to be associated with pain and stress [6, 7]; of note, this stress could even negate the beneficial effect of TH [13]. During TH in adults post cardiac arrest, sedation and analgesia are considered as essential in order to avoid shivering and achieve toleration of the treatment [32, 33]. When using opioids and other drugs during TH, there is a potential risk for adverse effects due to the effect of TH on the clearance and distribution of drugs [10, 13], which complicates dose settings. An additional challenge is posed by the lack of validated tools to assess pain during TH. Lago et al. [34] reported that there are knowledge gaps regarding both measuring and managing pain and stress during TH. We could not find other systematic reviews addressing the topic of our study. The protocol of a Cochrane review has been published, however it will include only randomized trials and a narrower list of drugs [35].

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this systematic review include the broad and complete search strategy, the publication of a protocol a priori, and the validated methodology to assess the included studies, e.g. Cochrane’s ‘Risk of Bias’ 2.0 tool and the ROBINS-I. We adhered to the protocol to minimize intellectual bias in conducting and reporting the findings. Screening for inclusions and risk-of-bias assessment were independently performed by two authors. Potential limitations include our broad approach, i.e. that, for example, we included all studies regardless of the type of drugs, which may have contributed to the large clinical heterogeneity of the included studies. Furthermore, our choice of the definition of outcomes could be discussed. We chose analgesia and sedation; circulatory instability; mortality to discharge; and neurodevelopmental disability as the primary outcomes while most of the included studies reported on seizures, which may be an outcome equally relevant to patients. Finally, we could not pool the included studies in any meta-analyses due to substantial heterogeneity.

Implications for Future Research

Future trials should optimize the use of tools to assess pain and report clinically relevant outcome for the infants and their families, and identify an appropriate comparator when the use of a placebo is considered unethical. Studies enrolling infants with moderate and severe HIE are needed to evaluate any differential effects of the intervention on both pain and agitation management and long-term outcomes. Observational studies might provide valuable information related to potential harms of the pharmacological interventions.

Conclusion

We found limited evidence to establish the benefits and harms of the interventions for the management of pain and sedation in newborn infants undergoing TH. Given the very low certainty of evidence—due to imprecision of the estimates, inconsistency and limitations in study design (all eight observational studies with overall serious risk of bias)—for all outcomes, clinical trials are required to determine the most effective interventions for the management of pain and sedation in this population.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Björklund (Library and ICT services, Lund University) for designing and running the search strategy.

Declarations

Funding

Open access funding provided by Örebro University.

Conflicts of interest

Pyrola Bäcke, Matteo Bruschettini, Ylva Thernström Blomqvist, Greta Sibrecht, and Emma Olsson declare they have no competing interests in relation to this systematic review.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent for participation and publication

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

PB, MB, YTB, and EO planned and designed the study. PB, MB, YTB, GS, and EO have made substantial contributions in refining the study and drafting the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kurinczuk JJ, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Human Dev. 2010;86:329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wassink G, Davidson J, Dhillon S, Zhou K, Bennet L, Thoresen M, Gunn A. Therapeutic hypothermia in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Curr Neurol Neurosci. 2019;19(2):2. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-0916-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunn A, Laptook A, Robertson N, Barks J, Thoresen M, Wassink G, et al. Therapeutic hypothermia translates from ancient history in to practice. Pediatr Res. 2017;81(1–2):202–209. doi: 10.1038/pr.2016.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs S, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi W, Inder T, Davis P. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003311.pub3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Axelin A, Cilio M, Asunis M, Peloquiin S, Franck L. Sleep-wake cycling in a neonate admitted to the NICU: a video-EEG case study during hypothermia treatment. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2013;27(3):263–273. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e31829dc2d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoffman K, Bromster T, Hakansson S, Van den Berg J. Monitoring of pain and stress in an infant with asphyxia during induced hypothermia: a case report. Adv Neonatal Care. 2013;13(4):252–261. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e31829d8baf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wassink G, Lear C, Gunn K, Dean J, Bennet L, Gunn A. Analgesics, sedatives, anticonvulsant drugs, and the cooled brain. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;20:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker SM. Early life pain—effects in the adult. Curr Opin Physiol. 2019;11:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cophys.2019.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams M, Lascelles D. Early neonatal pain—a review of clinical and experimental implications on painful conditions later in life. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:30. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanelli S, Buck M, Fairchild K. Physiologic and pharmacologic considerations for hypothermia therapy in neonates. J Perinatol. 2011;31(6):377–386. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ainsworth SB. Effects of therapeutic hypothermia on medications. In: Neonatal formulary: drug use in pregnancy and the first year of life. Seventh Edition. Wiley, West Sussex; 2015.

- 12.Lutz IC, Allegaert K, de Hoon JN, Marynissen H. Pharmacokinetics during therapeutic hypothermia for neonatal hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy: a literature review. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2020;4(1):e000685. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McPherson C, O’Mara K. Provision of sedation and treatment of seizures during neonatal therapeutic hypothermia. Neonatal Netw. 2020;39(4):227–235. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.39.4.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mangat A, Oei JL, Chen K, Quah-Smith I, Schmölzer G. A review of non-pharmacological treatments for pain management in newborn infants. Children. 2018;5(10):130. doi: 10.3390/children5100130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsson E, Bruschettini M, Thernström Blomqvist Y, Bäcke P. IPSNUT - Interventions for the management of Pain and Sedation in Newborns undergoing Therapeutic hypothermia for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a systematic review. PROSPERO 2020. CRD42020205755. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/#recordDetails. Accessed 2 May 2022.

- 16.Bäcke P, Bruschettini M, Thernström Blomqvist Y, Olsson E. Interventions for the management of pain and sedation in newborns undergoing therapeutic hypothermeia for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (IPSNUT): protocol of a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2022;11:101. doi: 10.1186/s13643-022-01982-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation). www.covidence.org. Accessed 2 May 2022.

- 18.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Sterne JA; on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JP, Green S (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v5.1/. Accessed 2 May 2022.

- 19.Sterne J, Hernán M, Reeves B, Savovic J, Bergman N, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Mara K, Weiss M. Dexmedetomidine for sedation of neonates with HIE undergoing therapeutic hypothermia: a single-center experience. AJP Rep. 2018;8(3):e168–e173. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1669938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abo Shady N, Ismail R, Abdi El Aal M. Pentoxifylline use for neuroprotection in neonates with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. QJM. 2018;111:i63–i64. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcy200.139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surkov D. Using of dexmedetomidine in term neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Med Perspekt. 2019;24(2):24–33. doi: 10.26641/2307-0404.2019.2.170123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liow N, Montaldo P, Lally P, Teiserskas J, Bassett P, Oliviera V, et al. Preemptive morphine during therapeutic hypothermai after neonatal encephalopathy: a secondary analysis. Ther Hypothermia Temp Manag. 2020;10(1):45–52. doi: 10.1089/ther.2018.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Favié L, Groenendaal F, van den Broek M, Rademakere C, de Haan T, van Straaten H, et al. Phenobarbital, midazolam pharmacokinetics, effectiveness, and drug-drug interaction in asphyxiated neonates undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. Neonatology. 2019;116:154–162. doi: 10.1159/000499330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyn D, Ness J, Ambalavanan N, Carlo W. Prophylactic phenobarbital and whole-body cooling for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2010;157(2):334–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sant’Anna G, Laptook A, Shankaran S, Bara R, McDonald S, Higgins R, et al. Phenobarbital and temperature profile during hypothermia for hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Child Neurol. 2012;27(4):451–457. doi: 10.1177/0883073811419317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao L, Hussain S, Zaki T, Cho A, Chanlaw T, Garg M, et al. A comparison of levetiracetam and phenobarbital for the treatment of neonatal seizures associated with hypoxic-iischemic encephalopathy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;88:212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berube M, Lemmon M, Pizoli C, Bidegani M, Tolia V, Cotton C. Opioid and benzodiazepine use durint therapeutic hypothermia in encephalopathic neonates. J Perinatol. 2020;40(1):79–88. doi: 10.1038/s41372-019-0533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Surkov D. Correction: Using of dexmedetomidine in term neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Medicini perspektivi. 2021;26:3. doi: 10.26641/2307-0404.2021.3.242347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarkar S, Barks J, Bapuraj J, Bhagat I, Dechert R, Schumacher R, et al. Does phenobarbital imiprove the effectiveness of therapeutic hypothermia in infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy? J Perinatol. 2012;32(1):15–20. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins RD, Raju TNK, Perlman J, Azzopardi DV, Blackmon LR, Clark R, et al. Hypothermia and perinatal asphyxia: Executive summary of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop. J Pediatr. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjelland T, Klepstad P, Haugen B, Nilsen T, Dalo O. Effects of hypothermia on the disposition of morphine, midazolam, fentanyl, and propofol in intensive care unit patients. Drug Metabol Dispos. 2012;41:214–223. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.045567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjelland T, Dale O, Kaisen K, Haugen B, Lydersen S, Strand K, Klepstad P. Propofol and remifentanil versus midazolam and fentanyl for sedation during therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest: a randomised trial. Intensive Care Med. 2014;38:959–967. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lago P, Spada C, Lugli L, Garetti E, Pirelli A, Savant Levet P, et al. Pain management during therapeutic hypothermia in newborn infants with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(3):628–629. doi: 10.1111/apa.15071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bäcke P, Bruschettini M, Sibrecht G, Thernström-Blomqvist Y, Olsson E. Pharmacological interventions for pain and sedation management in newborn infants undergoing therapeutic. Cochrane Database Syste Rev. 2022;11:CD015023. doi: 10.1002/1465858.CD015023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).