Abstract

Epidemic Vibrio cholerae strains possess a large cluster of essential virulence genes on the chromosome called the Vibrio pathogenicity island (VPI). The VPI contains the tcp gene cluster encoding the type IV pilus toxin-coregulated pilus colonization factor which can act as the cholera toxin bacteriophage (CTXΦ) receptor. The VPI also contains genes that regulate virulence factor expression. We have fully sequenced and compared the VPI of the seventh-pandemic (El Tor biotype) strain N16961 and the sixth-pandemic (classical biotype) strain 395 and found that the N16961 VPI is 41,272 bp and encodes 29 predicted proteins, whereas the 395 VPI is 41,290 bp. In addition to various nucleotide and amino acid polymorphisms, there were several proteins whose predicted size differed greatly between the strains as a result of frameshift mutations. We hypothesize that these VPI sequence differences provide preliminary evidence to help explain the differences in virulence factor expression between epidemic strains (i.e., the biotypes) of V. cholerae.

Pandemic cholera is traditionally caused by specific strains of Vibrio cholerae O1 (23, 41) which are divided into two biotypes with classical biotype strains representing remnants of the sixth-pandemic clone, while El Tor biotype strains represent the current seventh-pandemic clone. The exact genetic relationship between these strains, however, is not well understood nor have the reasons why the seventh-pandemic clone replaced the sixth-pandemic clone been determined. Classical and El Tor strains were originally distinguished on the basis of their differences in several biochemical properties, including the ability to hemolyze sheep red blood cells, the susceptibility to polymyxin B, and the Voges-Proskauer reaction. Interestingly, as the seventh-pandemic has progressed, an increasing number of strains have been isolated which, like classical biotype strains, are hemolysin negative (1, 7, 44, 45). The biotypes also differ in the expression of several important virulence factors such as the coordinately regulated cholera toxin and toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP); however, until recently, the genetics underlying these differences were not well understood (5, 13, 20–22, 36, 46, 47). It has recently been shown that an explanation as to the differences in virulence factor expression are associated with variation in the tcpPH promoter region (29). Because it could be argued that seventh-pandemic strains are losing several phenotypes and developing classical biotype characteristics and because essential El Tor characteristics are found in many nonpathogenic environmental strains, we refer here to the isolates as being of the sixth- or the seventh-pandemic.

Epidemic V. cholerae strains possess two gene clusters that provide a normally marine or estuarine bacterium with the ability to colonize the human intestine and secrete a potent toxin, resulting in severe diarrhea (24, 35, 47, 49). These virulence gene clusters are absent from nonpathogenic strains. The genes encoding cholera toxin together with the adjacent genes on the CTX element are carried on the genome of a filamentous bacteriophage (CTXΦ) (49). The Vibrio pathogenicity island (VPI) is one of the initial genetic factors required for the emergence of epidemic V. cholerae. It contains several gene clusters, including the tcp gene cluster which encodes the type IV pilus structure known as TCP that is an essential colonization factor (16, 47) and acts as the CTXΦ receptor (49). We recently found evidence that the VPI appears to be phage encoded and can also form a plasmid replicative form (24, 26). The VPI also contains genes that encode proteins that regulate virulence (4–6, 14), and it contains numerous open reading frames (ORFs) with no known function.

There has long been an interest in the relationship of the sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains. The characteristics of the El Tor biotype are essentially those of most environmental nonpathogenic strains, while those of the classical biotype differ by the absence (loss) of functions with regard to hemolysin production, Voges-Proskauer reaction, and hemagglutination (1, 7–10, 45). Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) indicates that the strains responsible for the two pandemics are related, but the first presumed housekeeping gene (asd) to be sequenced from both pandemic strains differed at 1.6% of bases, suggesting a long period of divergence. This led us to the hypothesis that the two pandemic strains were independently derived from different environmental strains (25). However, further study (3) showed that three genes (mdh, dnaE, and 1,038 bp of hlyA sequenced) are identical in the sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains, apart from the known 11-bp deletion in hlyA of sixth-pandemic strains, which makes them hemolysin negative. Furthermore, in addition to asd with 1.6% base differences, recA differed at 4.59% of bases. Thus, the five genes fall into two classes: those identical or nearly so and those which are in the normal range for divergence of distantly related strains of a species. We interpreted the presence of three genes with no evidence of any sequence differences due to random genetic drift to mean that the two pandemic strains were closely related, as previously indicated by MLEE, but not directly derived from each other. The other two genes differ by 1.6% (asd) and 4.59% (recA), with every indication that the differences are due to random genetic drift of neutral mutations. It is highly improbable that this level of variation could have accumulated over a time in which no base substitution occurred in the other genes, and we concluded that for both asd and recA they had undergone whole-gene substitution by recombination.

In pursuit of our interest in the factors and processes involved in the emergence, pathogenesis, persistence, and spread of epidemic V. cholerae, we have fully sequenced and compared the entire VPI loci from representative strains from the sixth- and seventh-pandemics. Although several previous studies have reported the sequence of specific regions of the VPI from sixth- or seventh-pandemic strains (18, 19, 24, 27, 39, 40), a complete VPI analysis and comparison has not been performed to date. Where genes have been sequenced from both pandemics, the level of difference ranged from 0% (e.g., aldA) to 22% for tcpA. It seems clear that different parts of the VPI have different histories and in order to study this a complete sequence from at least one strain of each pandemic is needed. We report here the differences in VPI sequence, size, and gene structure between the two pandemic clones.

Sequencing the VPI from representative strains.

DNA sequence from positions 1 to 12,765 (numbering starts after the left att site) of N16961 was reported previously by us (24) and not resequenced. DNA from positions 1 to 11196 of strain 395 was sequenced by random shotgun analysis of cosmid DNA as described previously (24). The remainder of each VPI was sequenced by directional PCR sequencing using overlapping primers as enough of the VPI had been previously sequenced in either a sixth- or a seventh-pandemic strain or both. Primers were designed to amplify overlapping segments 1 kb in length. We first sequenced the regions not previously sequenced for that pandemic clone but, since the pattern of differences between the two pandemics suggested that some could be due to sequencing errors, we also resequenced those regions previously done by other laboratories, specifically the tcp regions of both sixth and seventh pandemic strains reported by Ogierman et al. (39) (GenBank accession numbers X74730 and X604098) and the acf region reported by Kovach et al. (27) (GenBank accession number U39068). Sequences were edited using either SEQUENCHER software version 3.0 (Genecodes, Ann Arbor, Mich.) or PHRED-PHRAP-CONSED programs (http://bozeman.mbt.washington.edu) (11). Regions previously sequenced were included as reference for comparative editing. Any difference between our sequence and the published sequence was checked in the sequence chromatogram. The sequence differences between sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains were inspected base-by-base by using the CONSED custom navigation facility. Sequence comparisons were done using Multicomp (42). ORF analysis and database searches were done using the ORF finder and BLAST search facilities of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The substitution rate was calculated by using a program provided by Li (33).

N16961 was sequenced as a representative of the current seventh-pandemic: it has been used in several studies, including human volunteer studies (31, 32), and its complete genome (containing two chromosomes) has recently been fully sequenced by The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) (15). Strain 395 was used as a representative of the sixth-pandemic strain as it has been used in many studies on virulence (31). The VPI nucleotide position numbers in our study correspond to the VPI sequence for each strain and are different at various regions along the VPI due to variation between the sequences. The proportion of discrepancies between our data and earlier sequences was quite low, but the total number was substantial. We are confident of our sequence since sequencing technology has improved over the years and, with the benefit of hindsight, we are able to check our data in the areas of concern when necessary. We attribute the differences between our data and earlier sequences to sequencing error rather than to the use of different strains. In many cases, the changes brought sixth- and seventh-pandemic sequences into agreement, which is most unlikely to be due to coincidence, and substantially reduced the level of difference in the region of low divergence.

General comparison of the VPI in sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains.

The VPI is flanked by 13- and 20-bp imperfect direct repeat sequences having homology to phage attachment (att) sites (24, 28). In a previous study (24), we found evidence that the VPI DNA between both att sites is unique to epidemic strains and absent from nonpathogenic strains, while the DNA outside the left and right att sites is common to all V. cholerae strains. Interestingly, it was recently found that the VPI also appears to have been horizontally transferred and acquired by a Vibrio mimicus strain and that the VPI has the same chromosomal (att site) insertion site as in V. cholerae (2). In the current study, we found that the VPI has the same specific chromosomal insertion site in both N16961 and 395 strains. After performing a complete sequence analysis, we have determined that the N16961 VPI is 41,272 bp and that the 395 VPI is 41,290 bp (excluding the att sites). The percent G+C composition of the VPI from both strains (35.5%) is very different from that of the rest of the host chromosome (ca. 47%) (15), a finding typical of pathogenicity islands (12, 30), and suggests the VPI was acquired from a foreign source. Computer analysis of the VPI sequences revealed the presence of 29 predicted ORFs (of >55 codons) for both strains N16961 and 395. Comparison of our N16961 sequence with that recently published by TIGR (15) revealed a discrepancy (an insertion) in the N16961 tagA gene reported by TIGR. Our sequencing of N16961 and 395 showed that both strains were identical at this site and different from the TIGR sequence. The TIGR genomic sequence analysis of N16961 reported the VPI as 45.3 kb rather than the 41.2 kb that we report here. The 45.3-kb size refers to a larger region of atypical nucleotide composition in N16961 that includes sequences outside the att sequences that we use to define the VPI (J. Heidelberg, personal communication).

There were several long intergenic sequences including one region between acfD and int that was reported to contain three ORFs (OrfZ, OrfW, and OrfV) in a sixth-pandemic strain by Hughes et al. (17) (GenBank accession number U39068). However, our two sequences in this region, which differ at only one base between the two strains, differ at several sites from the published sequence, and the longest ORF is 52 amino acids long. It is quite possible that this region once coded for a protein but a BLAST search did not reveal any compelling homologues of the short ORFs.

We found 483 polymorphic nucleotides (1.17% nucleotide difference) between the VPIs of the two strains, of which 60 differences are at the first base position in the codon, 47 occur at the second base, 209 occur at the third base, and 167 occur within intergenic regions. There were 97 amino acid differences (0.8% amino acid difference) between the strains.

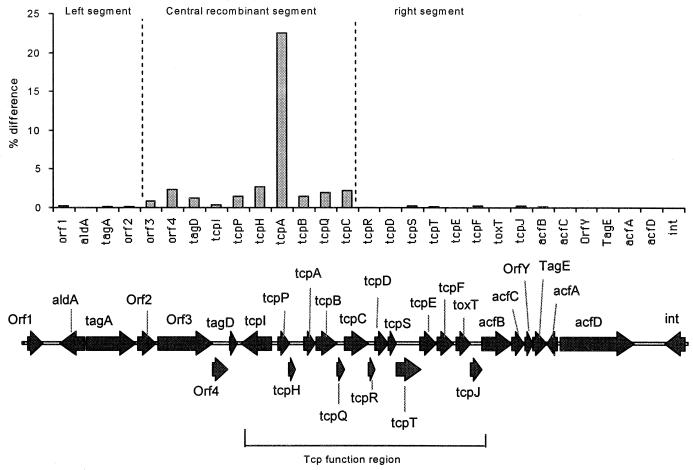

The level of difference varies greatly along the 41.2-kb length of the VPI (Table 1and Fig. 1) and three segments (left, center, and right in Fig. 1) can be recognized based on the level of difference between the sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains. The four genes in the left segment (orf1 to orf2) covering bases 1 to 8804 and the 15 genes in the right segment (tcpR to int) covering bases 21425 to 41139 show relatively little difference between the two sequences, whereas those in the center (orf3 to tcpC) have higher and varying levels of difference. The intergenic regions follow the same pattern as the genes. In the central segment, the tcpI-tcpP and tcpH-tcpA intergenic regions have particularly high levels of variation, but all intergenic regions in this segment have higher levels than do intergenic regions in the left and right segments. These segments with different levels of variation do not correspond to groupings of genes based on function. Our data are consistent with previous studies (34, 43) showing that the VPI “central region” containing the tcp genes tcpI-tcpC, and tcpA in particular, shows the highest level of variation on the VPI.

TABLE 1.

Sequence variation in VPI genes of N16961 (seventh pandemic) and 395 (sixth pandemic)

| Gene or intergenic regiona | Length (bp) | No. of:

|

% Difference | Ks | Ka | Ks/Ka ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorphic sites | Nonsynonymous sites | ||||||

| orf1 | 978 | 2 | 0 | 0.204 | 0.00559 | 0 | 0 |

| aldA | 1,521 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| tagA | 3,009 | 5 | 3 | 0.166 | 0.00306 | 0.00177 | 1.72881 |

| Intergenic | 1 | ||||||

| orf2∗ | 1,116 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00099 | 0 | |

| orf3∗ | 2,889 | 24 | 9 | 0.831 | 0.01583 | 0.00466 | 3.39699 |

| orf4 | 939 | 22 | 5 | 2.343 | 0.0669 | 0.00909 | 7.35973 |

| Intergenic | 7 | ||||||

| tagD | 495 | 6 | 2 | 1.212 | 0.02423 | 0.00619 | 3.91437 |

| Intergenic | 21 | ||||||

| tcpI | 1,863 | 8 | 3 | 0.429 | 0.00849 | 0.00228 | 3.72368 |

| Intergenic | 45 | ||||||

| tcpP | 666 | 10 | 5 | 1.502 | 0.01747 | 0.01212 | 1.44141 |

| tcpH | 411 | 11 | 5 | 2.676 | 0.10626 | 0.01614 | 6.58364 |

| Intergenic | 67 | ||||||

| tcpA | 675 | 152 | 45 | 22.519 | 1.0588 | 0.12187 | 8.68852 |

| Intergenic | 25 | ||||||

| tcpB | 1,293 | 19 | 3 | 1.469 | 0.04601 | 0.00332 | 13.8584 |

| tcpQ | 453 | 9 | 2 | 1.987 | 0.08709 | 0.00837 | 10.4050 |

| tcpC | 1,470 | 32 | 3 | 2.177 | 0.09158 | 0.00368 | 24.8858 |

| tcpR | 456 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| tcpD | 822 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| tcpS | 459 | 1 | 1 | 0.218 | 0 | 0.00339 | 0 |

| tcpT | 1,512 | 1 | 1 | 0.066 | 0 | 0.00076 | 0 |

| tcpE | 1,023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| tcpF | 1,017 | 3 | 3 | 0.295 | 0 | 0.00456 | 0 |

| Intergenic | 1 | ||||||

| toxT | 831 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| tcpJ | 762 | 2 | 0 | 0.262 | 0.00730 | 0 | 0 |

| acfB | 1,881 | 2 | 2 | 0.106 | 0 | 0.00164 | 0 |

| acfC | 762 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| orfY | 474 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| tagE | 909 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| acfA | 648 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| acfD∗ | 4,563 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intergenic | 1 | ||||||

| int | 1,269 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

∗, for orf2, orf3, and acfD, the largest common segment was used. See the text for details. The frameshift mutation was not included as a polymorphic site for this purpose.

FIG. 1.

Plot of DNA percentage differences of VPI genes between sixth (classical strain 395)- and seventh (El Tor strain N16961)- pandemic clones of V. cholerae. For orf2, orf3, and acfD, where translation frames differ between the strains, the differences are calculated based on the larger segment shared between the two clones. See the text for additional details. The genetic map of the seventh-pandemic clone is depicted at the bottom.

Frameshift differences.

Orf2 and Orf3 have no known function as yet, but they differ between the sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains in predicted size and structure. This difference results from a frameshift mutation (no base in N16961 and a T in 395) that alters the last 8 amino acids at the C-terminal end of orf2 in 395, thereby extending the ORF and yielding a truncated Orf3 in 395. Although we treat them as two ORFs, it is also possible that orfs2 and orf3 are a single orf with different single-base deletions disrupting the gene. A similar situation applies to acfD, which appears to have a role in colonization, in which the seventh-pandemic strain has the longer ORF. However, in this case, as has been observed before (17), in the sixth-pandemic strain there is a putative ribosomal frameshift motif, which under special conditions might allow the full ORF to be translated in the sixth-pandemic strain. For the comparisons reported in Table 1, we used the largest translated segment common to both. Importantly, the differences in gene structure and protein size observed between N16961 and 395 in orf2, orf3, and acfD were consistent in other sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains that we tested (unpublished data), suggesting that these differences are maintained in the two clones.

Variation in the ends of the VPI.

There is a total of five synonymous substitutions (three in orf2 and two in tcpJ) over 28,518 bp in the left and right segments combined, and we treat these two outer segments together, although there is a slightly higher level of variation in the left segment. We have previously shown (3) that the two pandemic strains are closely related since no mutational changes were detected in three genes. The finding of five synonymous substitutions over 28,518 bp of the VPI is consistent with the left and right segments being derived from the common ancestor, since our previous observation of no change in several housekeeping genes (thought to have been derived from the common ancestor) was based on 3,041 bp of the sequence. One would expect to observe some change if sufficient sequence is analyzed, and it may be that 0.018% synonymous substitution is found when sufficient housekeeping genes have been sequenced from both pandemic strains. Such a value is not inconsistent with our finding of no change in three housekeeping genes (the expectation is 0.5 substitutions in the 3,041 bp).

Values of Ks (synonymous substitution rate), Ka (nonsynonymous substitution rate), and the Ks/Ka ratios are also given in Table 1. Ks is a measure of the rate of synonymous substitutions being the proportion of sites which can undergo substitution without amino acid change and which have done so. Such mutations are generally neutral or of very low adaptive value. Ka is a similar measure for substitutions which do alter an amino acid. Although such mutations can be neutral, most adaptive mutations are in this category. The Ks/Ka ratio is often used as an indicator of neutral or adaptive variation. The Ks/Ka ratios in V. cholerae for the housekeeping genes asd,mdh, and recA are 30.88, 50.52, and 42.32, respectively, as calculated from the data of Karaolis et al. (25) and Byun et al. (3). For the genes in the left and right segments, the total number of substitutions is too low to give a meaningful comparison, although tagA has a value of Ks/Ka (1,7), suggesting that the differences may be due to natural selection rather than mere random genetic drift.

Variation in the central segment of the VPI.

The central segment from orf3 to tcpC contains much of the tcp gene cluster and has a much higher level of variation, with all genes having higher levels of variation (3.71% averaged over orf3 to tcpC and 1.62% excluding tcpA) than any in the left and right segments. However, tcpA which encodes the major protein subunit of the TCP (47) has by far the most divergence (34, 43). Rhine and Taylor reported that sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains differ in their tcpA sequence by 22.5% at the nucleotide level and by 16.9% at the protein level (43). The Ks/Ka value of 8.69 for tcpA also indicates selective pressure. When they were compared to other genes of the VPI, we also found higher levels of variation in the tagD-tcpI and tcpA-tcpB intergenic regions and higher percentage differences in orf4 (2.34%), tagD (1.21%), tcpP (1.50%), tcpH (2.67%), tcpB (1.46%), tcpQ (1.98%), and tcpC (2.17%).

Evolutionary history of the VPI.

The data we have presented on the VPI suggest that the two ends of the VPI had their last common ancestor at about the same time as the two pandemic strains themselves, although this will become clearer when more comparative sequence data is available for housekeeping genes. Thus, one explanation for the data is that following the acquisition of similar VPIs, the central region was substituted in one of the strains by recombination. An alternative explanation for the variation is that the two pandemic strains independently acquired differing VPI regions, most probably via phage infection. However, this does not give as ready an explanation of the variation in the level of divergence between the VPI sequences since it requires two events.

Since we started our studies on the VPI sequence, three new tcpA sequences have been reported. Two tcpA genes (37) are nearly identical to each other but quite different from the tcpA genes of sixth- and seventh-pandemic strains: one was from a clinical O1 strain, and the other was from a O34 nontoxigenic strain. The third (38) is from a toxigenic O53 strain and again differs substantially from the other three forms. In the case of the form isolated from the O1 and O34 strains, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and heteroduplex mobility analysis was carried out on tcpC/D (900 bp) and tcpE/T (680 bp), and no evidence was found for divergence between the two strains in the flanking segments. These data are consistent with our data in showing that the high divergence level was localized to a specific (i.e., central) region of the VPI.

The sharp break at each end of the central segment between genes with an average of 0.3% and those with an average of 1.6% divergence strongly suggests that a recombination event has occurred. The central segment includes tcpA, which encodes the major protein subunit of the TCP. It is known that differences in the TCP lead to differences in antigenic specificity and to substantial specificity in protective immunity (48). The polymorphism in tcpA with a product that is imunogenic and which may interact directly with the human host strongly suggests that it is subject to natural selection, and this may have driven the recombinational substitution of the central region of the VPI. It is also possible that the differences in TcpA affect interactions with various phage using it as a receptor in a way that is subject to selection. The other genes in the central segment having an average level of difference of 1.6% may have simply been part of the donor strain's VPI which was carried along in the recombination. Alternatively, the variation in some of the genes may have contributed to some selective advantage since the differences between two pandemics seem to be, in part at least, subject to natural selection based on the ratio of Ka to Ks (see above).

Conclusions.

The VPI can also be divided into three functional regions. We use “region” for functional division to distinguish “segment” for recombination segments. The three regions are: (i) the VPI “left region” containing a gene encoding a potential transposase and several ORFs with no known function but which we are currently investigating; (ii) the VPI “central region” containing many of the tcp gene cluster encoding proteins for the TCP structure and also including the tcpPH genes involved in the coordinate regulation of TCP and cholera toxin expression; and (iii) the VPI “right region” including the remaining transport and assembly tcp genes, the toxT regulator of cholera toxin and TCP production, the tcpJ gene (which is required for processing), int (which has high homology to phage-like integrases), and the acf gene cluster (which appears to have a role in colonization). The central segment that has been subjected to recombination does not correspond to the central VPI region containing all of the tcp genes, since the presumed recombination event involved only 7 of the 13 tcp genes, as well as three genes, including tagD of the left region. The recombination segment included tcpA, which has undergone the most change and which may be the gene that conferred all or most of the adaptive advantage leading to the selection for recombination. We have previously reported that V. cholerae appears to have a higher level of genetic exchange (horizontal gene transfer) in its housekeeping genes, including those for the O serogroup antigen, compared to E. coli and Salmonella enterica (3, 25).

The VPI is an essential genetic factor in the virulence of V. cholerae. Our data show that if the two pandemic clones emerged from a common stock, there have been important changes in the VPI during the divergence of the two clones. It is too early to determine the full significance of the changes involved since the function of many VPI genes are yet to be determined. However, it seems that V. cholerae as a species has a pool of variation in the central segment of the VPI and that this has contributed to the emergence and evolution of the pathogenic forms by horizontal gene transfer and recombinational exchange.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences described here for N16961 and 395 have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. AF325733 and AF325734, respectively).

Acknowledgments

We thank Debbie Rothemund for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (AI45637 to D.K.R.K. and AI19716 to J.B.K.) and the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NH&MRC to P.R.R). D.K.R.K is a recipient of a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barett J, Blake P A. Epidemiological usefulness of changes in hemolytic activity of V. cholerae biotype El Tor during the seventh pandemic. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;13:126–128. doi: 10.1128/jcm.13.1.126-129.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd E F, Moyer K E, Shi L, Waldor M K. Infectious CTXΦ and the vibrio pathogenicity island prophage in Vibrio mimicus: evidence for recent horizontal transfer between V. mimicus and V. cholerae. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1507–1513. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1507-1513.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byun R, Elbourne L D H, Lan R, Reeves P R. Evolutionary relationships of the pathogenic clones of Vibrio cholerae by sequence analysis of four housekeeping genes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1116–1124. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1116-1124.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll P A, Tashima K T, Rogers M B, DiRita V J, Calderwood S B. Phase variation in tcpH modulates expression of the ToxR regulation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1099–1111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5371901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiRita V J. Co-ordinate expression of virulence genes by ToxR in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiRita V J, Parsot C, Jander G, Mekalanos J J. Regulatory cascade controls virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5403–5407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feeley J C. Classification of Vibrio cholerae (Vibrio comma), including E1 Tor vibrios, by intrasubspecific characteristics. J Bacteriol. 1965;89:665–678. doi: 10.1128/jb.89.3.665-670.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelstein R A, Muckerjee S. Hemagglutination: a rapid method for differentiating V. cholerae and E1 Tor vibrios. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1963;112:335–339. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallut J. Actualité du choléra: evolution des problèmes épidémiologiques et bactériologiques. Bull Inst Pasteur. 1968;66:219–248. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallut J. La septième pandémic cholérique. Bull Soc Pathol Exot (Paris) 1971;64:551–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon D, Abajian C, Green P. CONSED—a graphical tool for sequence finishing. PCR Methods Appl. 1998;8:195–202. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Muhldorfer I, Tschape H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall R H, Vial P A, Kaper J B, Mekalanos J J, Levine M M. Morphological studies on fimbriae expressed by Vibrio cholerae O1. Microb Pathog. 1988;4:257–265. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Häse C C, Mekalanos J J. TcpP protein is a positive regulator of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:730–734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidelberg J F, Eisen J A, Nelson W C, Clayton R A, Gwinn M L, Dodson R J, Haft D H, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Umayam L, Gill S R, Nelson K E, Read T D, Tettelin H, Richardson D, Ermolaeva M D, Vamathevan J, Bass S, Qin H, Dragoi I, Sellers P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Fleishmann R D, Nierman W C, White O, Salzberg S L, Smith H O, Colwell R R, Mekalanos J J, Venter J C, Fraser C M. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature. 2000;406:477–483. doi: 10.1038/35020000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrington D A, Hall R H, Losonsky G A, Mekalanos J J, Taylor R K, Levine M M. Toxin, toxin-coregulated pili, and the toxR regulon are essential for Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis in humans. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1487–1492. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.4.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes K J, Everiss K D, Kovach M E, Peterson K M. Sequence analysis of the Vibrio cholerae acfD gene reveals the presence of an overlapping reading frame, orfZ, which encodes a protein that shares sequence similarity to the FliA and FliC products of Salmonella. Gene. 1994;146:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iredell J R, Manning P A. Biotype-specific tcpA genes in Vibrio cholerae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:47–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iredell J R, Manning P A. The toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP) of Vibrio cholerae O1: a model for type IV pilus biogenesis? Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90109-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwanaga M, Yamamoto K, Higa N, Ichinose Y, Nakasone N, Tanabe M. Culture conditions for stimulating cholera toxin production by Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor. Microbiol Immunol. 1986;30:1075–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb03037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonson G, Holmgren J, Svennerholm A M. Epitope differences in toxin-coregulated pili produced by classical and El Tor Vibrio cholerae O1. Microb Pathog. 1991;11:179–188. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90048-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonson G, Svennerholm A M, Holmgren J. Analysis of expression of toxin-coregulated pili in classical and El Tor Vibrio cholerae O1 in vitro and in vivo. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4278–4284. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4278-4284.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaper J B, Morris J G, Jr, Levine M M. Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:48–86. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karaolis D K R, Johnson J A, Bailey C C, Boedeker E C, Kaper J B, Reeves P R. A Vibrio cholerae pathogenicity island associated with epidemic and pandemic strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3134–3139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karaolis D K R, Lan R, Reeves P R. The sixth and seventh cholera pandemics are due to independent clones separately derived from environmental, nontoxigenic, non-O1 Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3191–3198. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3191-3198.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karaolis D K R, Somara S, Maneval D R, Jr, Johnson J A, Kaper J B. A bacteriophage encoding a pathogenicity island, a type-IV pilus and a phage receptor in cholera bacteria. Nature. 1999;399:375–379. doi: 10.1038/20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovach M E, Hughes K J, Everiss K D, Peterson K M. Identification of a ToxR-activated gene, tagE, that lies within the accessory colonization factor gene cluster of Vibrio cholerae O395. Gene. 1994;148:91–95. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovach M E, Shaffer M D, Peterson K M. A putative integrase gene defines the distal end of a large cluster of ToxR-regulated colonization genes in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology. 1996;142:2165–2174. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovacikova G, Skorupski K. Differential activation of the tcpPH promoter by AphB determines biotype specificity of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3228–3238. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3228-3238.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee C A. Pathogenicity islands and evolution of bacterial pathogens. Infect Agents Dis. 1996;5:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine M M, Black R E, Clements M L, Nalin D R, Cisneros L, Finkelstein R A. Volunteer studies in development of vaccines against cholera and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: a review. In: Holme T, Holmgren J, Merson M H, Mollby R, editors. Acute enteric infections in children: new prospects for treatment and prevention. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier/North-Holland Biomedical Press; 1981. pp. 443–459. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine M M, Kaper J B, Herrington D, Losonsky G, Morris J G, Clements M, E. B R, Tall B, Hall R. Volunteer studies of deletion mutants of Vibrio cholerae O1 prepared by recombinant techniques. Infect Immun. 1988;56:161–167. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.161-167.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W-H. Unbiased estimation of the rates of synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution. J Mol Evol. 1993;36:96–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02407308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manning P A. The tcp gene cluster of Vibrio cholerae. Gene. 1997;192:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mekalanos J J, Swartz D J, Pearson G D N. Cholera toxin gene: nucleotide sequence, deletion analysis and vaccine development. Nature. 1983;306:551–557. doi: 10.1038/306551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller V L, Taylor R K, Mekalanos J J. Cholera toxin transcriptional activator ToxR is a transmembrane DNA binding protein. Cell. 1987;48:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nandy B, Nandy R K, Vicente A C P, Ghose A C. Molecular characterization of a new variant of toxin-coregulated pilus protein (TcpA) in a toxigenic non-O1/non-O139 strain of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 2000;68:948–952. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.948-952.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novais R C, Coelho A, Salles C A, Vicente A C P. Toxin-coregulated pilus cluster in non-O1, nontoxigenic Vibrio cholerae: evidence of a third allele of pilin gene. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;171:49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogierman M A, Voss E, Meaney C A, Faast R, Attridge S R, Manning P A. Comparison of the promoter proximal regions of the tcp gene cluster in classical and El Tor strains of Vibrio cholerae O1. Gene. 1996;170:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogierman M A, Zabihi S, Mourtzois L, Manning P A. Genetic organization and sequence of the promoter-distal region of the tcp gene cluster of Vibrio cholerae. Gene. 1993;126:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90589-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollitzer R. Cholera. Monograph series 43. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reeves P R, Farnell L, Lan R. MULTICOMP: a program for preparing sequence data for phylogenetic analysis. CABIOS. 1994;10:281–284. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhine J A, Taylor R K. TcpA pilin sequences and colonization requirements for O1 and O139 Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1013–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roy C, Mukerjee S. Variability in the haemolytic power of El Tor vibrios. Ann Biochem Exp Med. 1962;22:295–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roy C, Mukerjee S, Tanamal S J W. Haemolytic and non-haemolytic El Tor vibrios. Ann Biochem Exp Med. 1963;23:553–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma D P, Thomas C, Hall R H, Levine M M, Attridge S R. Significance of toxin-coregulated pilus as protective antigens of Vibrio cholerae on the infant mouse model. Vaccine. 1989;7:451–456. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(89)90161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor R K, Miller V L, Furlong D B, Mekalanos J J. The use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:2833–2837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voss E, Manning P A, Attridge S R. The toxin-coregulated pilus is a colonization factor and protective antigen of Vibrio cholerae El Tor. Microb Pathog. 1996;20:141–153. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waldor M K, Mekalanos J J. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science. 1996;272:1910–1914. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]