Abstract

Clinical trials have shown that baricitinib, an oral selective Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor, is effective for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. However, daily practice data are limited. Therefore, this multicentre prospective study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of 16-weeks’ treatment with baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in daily practice. A total of 51 patients from the BioDay registry treated with baricitinib were included and evaluated at baseline and after 4, 8 and 16 weeks of treatment. Effectiveness was assessed using clinician- and patient-reported outcome measurements. Adverse events and laboratory assessments were evaluated at every visit. At week 16, the probability (95% confidence interval) of achieving Eczema Area and Severity Index ≤ 7 and numerical rating scale pruritus ≤ 4 was 29.4% (13.1–53.5) and 20.5% (8.8–40.9), respectively. No significant difference in effectiveness was found between dupilumab non-responders and responders. Twenty-two (43.2%) patients discontinued baricitinib treatment due to ineffectiveness, adverse events or both (31.4%, 9.8% and 2.0%, respectively). Most frequently reported adverse events were nausea (n = 6, 11.8%), urinary tract infection (n = 5, 9.8%) and herpes simplex infection (n = 4, 7.8%). In conclusion, baricitinib can be an effective treatment option for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, including patients with non-responsiveness on dupilumab. However, effectiveness of baricitinib is heterogeneous, which is reflected by the high discontinuation rate in this difficult-to-treat cohort.

Key words: atopic dermatitis, baricitinib, daily practice, JAK-inhibitor, patient-reported outcome measures

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most common chronic inflammatory skin diseases worldwide (1). Although most patients are diagnosed with mild AD, which can usually be treated with topical therapy, a considerable subset of patients have moderate-to-severe AD (1, 2). These patients often need treatment with potent topical steroids and systemic immunosuppressive treatment to control their AD (3). Until recently, adequate systemic treatment options for patients with moderate-to-severe AD were limited. Due to increased understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of AD in the past decade, more targeted therapies for moderate-to-severe AD have been developed that address this unmet need and may contribute to a more personalized treatment for patients with AD (4).

SIGNIFICANCE

To date, daily practice data on the effectiveness and safety of baricitinib treatment are limited. This study of 51 adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis treated with baricitinib showed that baricitinib can be an effective treatment option in a subgroup of adult patients in daily practice, including patients who failed on dupilumab treatment due to ineffectiveness. However, the effectiveness of baricitinib is rather heterogeneous, as reflected by the high discontinuation rate in this difficult-to-treat cohort. Most frequently reported adverse events were comparable to those reported in clinical trials.

In the Netherlands, dupilumab was the first monoclonal antibody inhibiting interleukin (IL)-4/IL-13 signalling, and baricitinib was the first oral selective Janus kinase (JAK)1/2 inhibitor that became commercially available for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD (October 2017 and December 2020, respectively) (5, 6). Baricitinib inhibits the JAK-STAT signalling and thereby several pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in AD pathogenesis, including thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-22 and IL-31, are downregulated (7, 8). Clinical trials with baricitinib 2 and 4 mg once daily (QD) showed significant improvement in signs and symptoms of moderate-to-severe AD, together with improvement in quality of life (QoL), work productivity and daily functioning (7–10). To date, daily practice data on the effectiveness and safety of baricitinib treatment are limited (11, 12).

Therefore, this study evaluated the clinical effectiveness and safety of 16-weeks’ treatment with baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe AD in daily practice. In addition, effectiveness was evaluated for dupilumab non-responders (dupilumab-NR) and dupilumab responders/ naïve patients (dupilumab-R/naïve).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

A prospective multicentre observational cohort study was performed including patients with moderate-to-severe AD (≥ 18 years) participating in the BioDay registry from January 2021 until February 2022. The BioDay registry is a Dutch registry that contains daily practice data on effectiveness and safety of new advanced systemic therapies for the treatment of AD. Patients of all ages who are willing to participate in the BioDay registry and who are starting treatment with an advanced systemic therapy were included. All patients fulfilled the criteria for baricitinib treatment established by the Dutch Society of Dermatology and Venereology (NVDV) (6). The study was approved by the local medical research ethics committee in Utrecht, The netherlands, as a non-interventional study (METC 18-239) and was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Treatment and data collection

Patients were treated with the standard dosage of baricitinib 4 mg QD. For patients ≥ 75 years old or in case of chronic/recurrent infections and/or creatinine clearance of 30–60 ml/min, baricitinib dosage was adjusted to 2 mg QD. Patients visited the outpatient clinic prior to baricitinib initiation (baseline), and after 4, 8 and 16 weeks of treatment. Systemic immunosuppressive and/or immunomodulating treatment was, if possible, discontinued before baricitinib initiation. Patients were recorded as using concomitant immunosuppressive treatment when prednisolone or cyclosporine A had been used within 1 week, methotrexate within 4 weeks and dupilumab within 10 weeks prior to baricitinib treatment, respectively. For example, if a patient discontinued dupilumab treatment 2 weeks prior to baricitinib initiation, the patient was considered as having concomitant immunosuppressive treatment until week 8 of baricitinib treatment. During baricitinib treatment adverse events (AEs) were evaluated and laboratory assessments (blood count, liver enzymes, serum creatinine, creatinine phosphokinase (CPK)) were performed at every visit. Lipid status was monitored at baseline and week 16.

Outcome measures

Clinical scores were rated by a trained physician at every visit, and included the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score (range 0–72) (13) and the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score based on a 6-point scale (range: clear; almost clear; mild; moderate; severe; very severe). In addition, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were collected, including the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) (range 0–30) (14), the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) (range 0–28) (15), the numerical rating scale (NRS) (range 0–10) (16) of the mean weekly pruritus and pain, and the Patient Global Assessment of Disease Status (PGADS) (range: poor (1); fair (2); good (3); very good (4); excellent (5), Table SI) (17). The Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT) (range 0–24) (18) was assessed at baseline and after 16 weeks of treatment. Primary endpoints were the mean EASI, NRS-pruritus and NRS-pain, DLQI and POEM at weeks 4, 8 and 16. Secondary endpoints were evaluated by absolute cut-off scores EASI ≤7 (19), IGA ≤1 ((almost) clear) (29), NRS-pruritus (19) and NRS-pain ≤4, DLQI≤5 (19), POEM ≤7 (19), ADCT <7 (18) and PGADS ≥3 (17) at weeks 4, 8 and 16. Effectiveness outcomes were stratified by dupilumab-NR (i.e. discontinuation of treatment due to ineffectiveness or a combination of ineffectiveness/AEs) and dupilumab-R/naïve (i.e. patients who discontinued treatment due to AEs/other reasons and patients with no previous dupilumab treatment). This stratification was performed to evaluate if the effectiveness of baricitinib was different for dupilumab non-responders, suggesting that these patients might have a more difficult-to-treat AD compared with patients who were naïve for dupilumab or experienced AEs (with an adequate response). IGA≤1 and ADCT<7 were not included in this analysis due to the low number of patients achieving the cut-off score in the dupilumab-NR and dupilumab-R/naïve subgroups. For safety analysis, AEs and laboratory abnormalities were ranked based on frequency and severity. Severity of the AEs was based on expert opinion. AEs that required treatment were documented as moderate and an AE that led to treatment discontinuation was reported as severe.

Statistical analysis

Initially, the overall percentage of missing values for clinical scores and PROMs was calculated (27.0%). Multiple imputation (MI) was performed to avoid bias and loss of statistical power (21, 22). MI was performed with linear regression for continuous variables. Sex, age, concomitant use of immunosuppressive treatment and number and reason of dropouts (i.e. patients who discontinued baricitinib treatment before or at week 16) were used as predictors. Outcomes of patients after discontinuation, although included in the imputation, were subsequently excluded from the analysis to avoid bias. The data were imputed 30 times, and all analyses were performed on each imputation separately. Results were pooled with Rubin’s rule.

For the analysis of continuous outcomes over time, a linear regression model was used. We included a residual covariance (i.e. GEE-type) matrix to correct for multiple measurements per patient over time. For dichotomous outcomes, a logistic regression with a random intercept was used. In a second step, the interaction of time with dupilumab-NR and dupilumab-R/naïve was included. Results from the analysis were used to estimate means (for continuous outcomes) and probabilities (for dichotomous outcomes) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and reported in figures. Effects of follow-up time and the interaction of the time with dupilumab response were tested with likelihood ratio tests.

Differences in baseline characteristics stratified by dupilumab-NR and dupilumab-R/naïve were analysed by a t-test for normally distributed and continuous outcomes and a χ2 test was used for dichotomous/categorical outcomes. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 27.0) and SAS v9.4. Likelihood ratio tests were pooled with the miceadds package in R (23, 24). p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism (version 8.3) was used to construct figures.

RESULTS

Patient and baseline characteristics

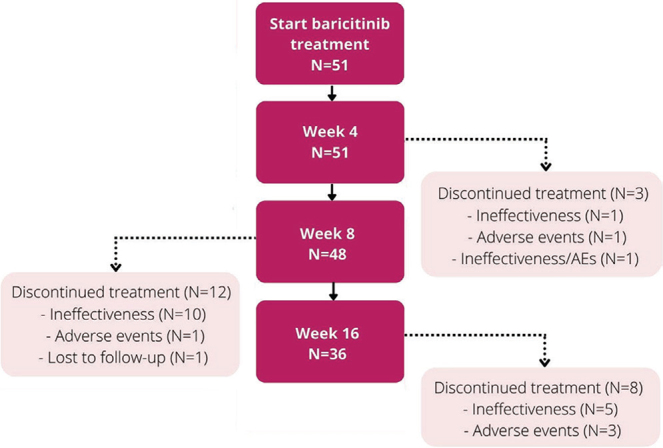

A total of 51 adult patients with AD treated with baricitinib were included. All patients were registered in the BioDay registry and treated between January 2021 and February 2022 in academic (n = 38) and non-academic hospitals (n = 13). At baricitinib initiation, the mean age was 39.5 years (standard deviation (SD) 15.5) and the majority of patients was male (n = 34, 66.7%). In total, 28 patients (54.9%) were using concomitant systemic immunosuppressive/immunomodulating treatment for their AD or comorbidity (rheumatoid arthritis, n = 1; tertiary adrenal insufficiency, n = 1) at baseline. Two (3.9%) patients started with baricitinib 2 mg QD due to impaired renal clearance together with an age ≥75 years, and obesity along with increased cardiovascular risks. All other patients (n = 49) used baricitinib 4 mg QD. In addition, 76.5% used medium to very high-potency (e.g. mometasone, betamethasone or clobetasol) topical corticosteroids. A total of 38 patients (74.5%) had failed on previous dupilumab treatment due to ineffectiveness (n = 16, 42.1%), AEs (n = 12, 31.6%) or both (n = 10, 26.3%). Almost all patients (n = 11, 91.7%), who discontinued previous dupilumab treatment due to AEs, achieved an EASI≤7 at the time of treatment discontinuation. Baseline characteristics, flowchart of patients and differences in dupilumab-NR and dupilumab-R/naïve are showed in Table I/Fig. 1.

Table I.

Baseline and patient characteristics

| Total cohort (n = 51) | Dupilumab |

p-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-responder (n = 26) | Responder/naïve patients (n = 25) | |||

| Male, n (%) | 34 (66.7) | 18 (69.2) | 16 (64.0) | 0.692 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 39.5 (15.5) | 40.2 (16.1) | 38.8 (15.1) | 0.752 |

| Age of onset atopic dermatitisb, n (%) | ||||

| Childhood | 40 (78.4) | 19 (73.1) | 21 (84.0) | 0.343 |

| Adolescence | 3 (5.9) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (8.0) | 0.529 |

| Adult | 8 (15.7) | 6 (23.1) | 2 (8.0) | 0.139 |

| Atopic disease at baseline, n (%) | 38 (74.5) | 18 (69.2) | 20 (80.0) | 0.378 |

| Allergic asthma | 23 (45.1) | 9 (34.6) | 14 (56.0) | 0.125 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 29 (56.9) | 14 (53.8) | 15 (60.0) | 0.486 |

| Missing | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 28 (54.9) | 13 (50.0) | 15 (60.0) | 0.555 |

| Missing | 4 (7.8) | 3 (11.5) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Food allergy | 17 (33.3) | 7 (26.9) | 10 (40.0) | 0.322 |

| Missing | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | |

| ≥ 2 atopic comorbidities | 29 (56.9) | 14 (53.8) | 15 (60.0) | 0.657 |

| Previous use of conventional immunosuppressive drugs, n (%) | 0.620 | |||

| Cyclosporine A | 43 (84.3) | 21 (80.8) | 22 (88.0) | 0.244 |

| Methotrexate | 20 (39.2) | 8 (30.8) | 12 (48.0) | 0.332 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 9 (17.6) | 3 (11.5) | 6 (24.0) | 0.959 |

| Azathioprine | 4 (6.1) | 3 (11.5) | 1 (4.0) | 0.317 |

| History of ≥2 immunosuppressive drugs | 24 (47.1) | 10 (38.5) | 14 (60.0) | 0.328 |

| Previous use of biological, n (%) | ||||

| Dupilumab | 38 (74.5) | 26 (100) | 12 (48.0) | NA |

| Reason of discontinuation dupilumab, n (%) | ||||

| Ineffectiveness | 16 (42.1) | 16 (61.5) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Adverse events | 12 (31.6) | 0 (0) | 12 (100) | NA |

| Ineffectiveness/adverse events | 10 (26.3) | 10 (38.5) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Previous use of JAK-inhibitor, n (%) | ||||

| Abrocitinib | 2 (3.9) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (4.0) | NA |

| Reason of discontinuation abrocitinib, n (%) | ||||

| Patient wish | 1 (50.0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Pregnancy wish | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | NA |

| Immunosuppressive therapy at baseline, n (%) | 0.882 | |||

| Cyclosporine A | 28 (54.9) | 17 (65.4) | 1 (44.0) | 0.025 |

| Methotrexate | 4 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (16.0) | 0.035 |

| Prednisolone | 5 (9.8) | 2 (7.7) | 3 (12.0) | 0.671 |

| Dupilumab | 5 (9.8) | 3 (11.6) | 2 (8.0) | 0.024 |

| EASI score, mean (SD) | 18.3 (13.5) | 18.6 (14.5) | 18.0 (12.6) | 0.863 |

| IGA score, n (%) | 0.940 | |||

| Clear | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Almost clear | 3 (5.9) | 1 (3.8) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Mild | 6 (11.8) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (12.0) | |

| Moderate | 18 (35.3) | 10 (38.5) | 8 (32.0) | |

| Severe | 18 (35.3) | 10 (38.5) | 8 (32.0) | |

| Very severe | 6 (11.8) | 3 (11.5) | 3 (12.0) | |

| NRS-pruritus, mean (SD) | 6.6 (2.2) | 6.6 (2.5) | 6.6 (2.0) | 0.958 |

| NRS-pain, mean (SD) | 4.2 (3.1) | 4.3 (3.1) | 4.1 (2.7) | 0.821 |

| DLQI score, mean (SD) | 12.0 (5.9) | 11.9 (5.9) | 12.0 (5.6) | 0.993 |

| POEM score, mean (SD) | 16.9 (6.9) | 17.1 (5.8) | 16.7 (4.5) | 0.757 |

| ADCT score, mean (SD) | 12.7 (4.4) | 13.7 (3.5) | 11.8 (4.4) | 0.094 |

| PGADS, n (%) | 0.420 | |||

| Poor | 16 (31.4) | 10 (27.8) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Fair | 20 (39.2) | 9 (34.6) | 11 (44.0) | |

| Good | 13 (25.5) | 7 (26.9) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Very good | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (8.0) | |

| Excellent | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Data after multiple imputation.

p-value calculated for differences between dupilumab-non-responder and dupilumab-responder/naïve.

Reference categories: childhood aged < 12 years, adolescence aged 12–17 years, adult ≥ 18 years.

Standard deviation (SD) was calculated by the standard error of the mean (SEM) multiplied by √n.

EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA: Investigator Global Assessment; NRS: numerical rating scale; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; ADCT: Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool; PGADS: Patient Global Assessment of Disease Status.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of 51 patients during the first 16 weeks of baricitinib treatment. AE: adverse event.

Effectiveness

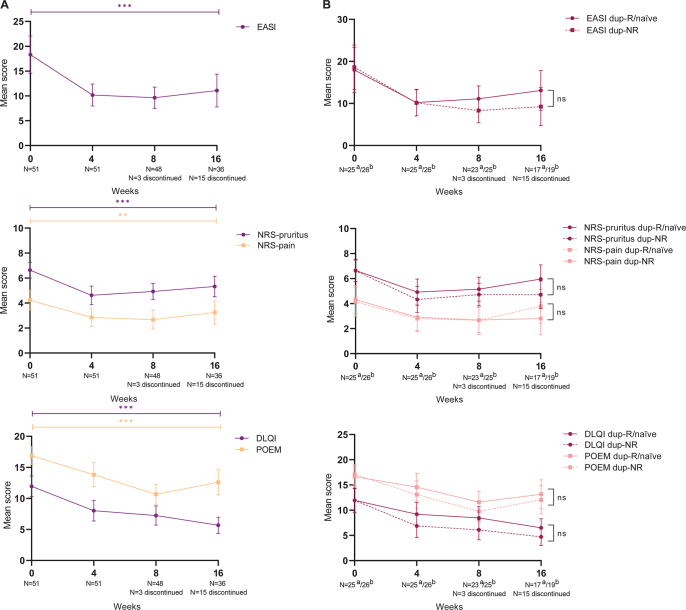

All primary outcomes significantly improved during 16 weeks of baricitinib treatment, with the largest change from baseline to week 4 (Table II/Fig. 2A). The mean EASI score significantly changed from 18.3 (95% CI 14.5–22.1) to 11.1 (95% CI 7.8–14.4) after 16 weeks of treatment (p < 0.0001). The mean NRS-pruritus significantly decreased from 6.6 (95% CI 6.0–7.3) to 5.3 (95% CI 4.5–6.2) at week 16 (p < 0.0001).

Table II.

Primary and secondary outcomes on the effect of 16-week baricitinib treatment in 51 patients with atopic dermatitis

| Baseline (n = 51) | Week 4 (n = 51) | Week 8 (n = 48) | Week 16 (n = 36) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who discontinued treatment, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.9) | 12 (23.5) | 8 (15.6) | |

| Concomitant immunosuppressive therapy, n (%) | 28 (54.9) | 20 (39.2) | 4 (8.3) | 3 (8.3) | |

| Primary endpoints, mean (95% CI) | |||||

| EASI score | 18.3 (14.5–22.1) | 10.2 (8.0–12.4) | 9.7 (7.5–11.8) | 11.1 (7.8–14.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Weekly average NRS-pruritus | 6.6 (6.0–7.3) | 4.6 (3.9–5.4) | 4.9 (4.3–5.6) | 5.3 (4.5–6.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Weekly average NRS-pain | 4.2 (3.4–5.0) | 2.9 (2.1–3.6) | 2.7 (1.9–3.4) | 3.3 (2.3–4.2) | 0.001 |

| DLQI score | 12.0 (10.3–13.6) | 8.0 (6.4–9.7) | 7.2 (5.7–8.8) | 5.7 (4.4–7.0) | < 0.0001 |

| POEM score | 16.9 (15.4–18.3) | 13.8 (11.9–15.7) | 10.7 (9.1–12.3) | 12.6 (10.6–14.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Secondary endpoints, n (%), probability % (95% CI) | |||||

| EASI score≤7 | 10 (19.6), 8.4 (2.6–23.8) | 19 (37.3), 27.4 (11.9–51.2) | 20 (41.7), 31.5 (12.9–58.8) | 19 (52.8), 29.4 (13.1–53.5) | 0.023 |

| IGA score≤1 | 3.0 (5.9), 1.9 (3.2–10.7) | 9 (17.6), 8.7 (2.5–26.1) | 13 (27.1), 16.1 (0.5–43.3) | 13 (36.1), 22.2 (7.8–49.0) | 0.002 |

| NRS-pruritus≤4 | 7 (13.7), 5.9 (1.7–18.4) | 21 (41.2), 35.9 (18.3–58.3) | 17 (35.4), 23.9 (9.2–49.3) | 15 (41.7), 20.5 (8.8–40.9) | < 0.0001 |

| NRS-pain≤4 | 25 (49.0), 48.3 (27.1–70.1) | 37 (72.5), 83.3 (63.5–93.5) | 35 (72.9), 50.9 (29.8–71.7) | 26 (72.2), 78.6 (54.9–91.8) | 0.004 |

| DLQI score≤5 | 8 (15.7), 9.6 (3.3–24.5) | 19 (37.3), 31.9 (16.3–52.9) | 15 (31.3), 22.2 (8.3–47.3) | 19 (52.8), 31.4 (15.2–53.8) | 0.027 |

| POEM score≤7 | 3 (5.9), 1.1 (0.1–10.0) | 9 (17.6), 6.5 (1.3–26.9) | 9 (18.8), 6.6 (1.7–31.5) | 8 (22.2), 4.8 (0.8–24.5) | 0.076 |

| ADCT score<7 | 2 (3.9), 2.8 (2.9–22.3) | – | – | 18 (50.0), 33.0 (15.0–57.8) | 0.003 |

| PGADS score≥3 | 15 (29.4), 27.0 (12.7–48.4) | 27 (52.9), 52.9 (34.0–71.0) | 23 (47.9), 46.9 (27.4–67.4) | 25 (69.4), 70.0 (47.5–85.7) | 0.277 |

Data after multiple imputation.

p-values based on overall likelihood ratio tests for time.

AD: atopic dermatitis; CI; confidence interval; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA: Investigator Global Assessment; NRS: numerical rating scale; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; ADCT: Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool; PGADS: Patient Global Assessment of Disease Status; –: not measured.

Fig. 2.

Primary effectiveness outcomes during 16 weeks of baricitinib treatment. (A) Clinician- and patient-reported outcomes including the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), numerical rating scale (NRS)-pruritus and NRS-pain, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM). (B) Clinician- and patient-reported outcomes including the EASI, NRS-pruritus and NRS-pain, DLQI and POEM stratified by: (a) dupilumab responders/naïve patients (dup-R/naïve) and (b) dupilumab non-responders (dup-NR). Data after multiple imputation. ***p < 0.0001, **p < 0.001, ns: non-significant.

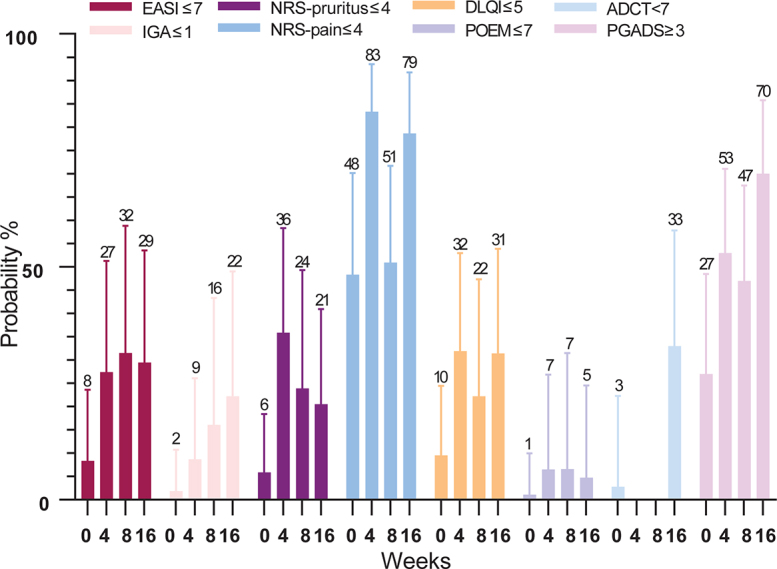

Secondary endpoints including absolute cut-off scores are shown in Table II/Fig. 3. The probability of achieving EASI≤7 at week 4 was 27.4% (95% CI 11.9–51.2) and 29.4% (95% CI 13.1–53.5) (p = 0.023) at week 16. For the NRS-pruritus ≤ 4 the probability was 35.9% (95% CI 18.3–58.3) at week 4 and 20.5% (95% CI 8.8–40.9) at week 16 (p = 0.003). After 16 weeks of treatment, the probability of achieving IGA≤1, NRS-pain ≤ 4, DLQI ≤ 5, POEM ≤ 7, ADCT<7, and PGADS ≥ 3 was 22.2% (95% CI 7.8–49.0), 78.6% (95% CI 54.9–91.8), 31.4% (95% CI 15.2–53.8), 4.8% (95% CI 0.8–24.5), 33.0% (15.0–57.8) and 70.0% (95% CI 47.5–85.7), respectively (Table II/Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Secondary effectiveness outcomes during 16 weeks of baricitinib treatment. Probability % of achieving Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)≤7, Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) ≤1, numerical rating scale (NRS)-pruritus and NRS-pain≤4, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)≤5, Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM)≤7, Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT)<7 and Patient Global Assessment of Disease Status (PGADS)≥3. Data after multiple imputation.

Most patients continued on a baricitinib dosage of 4 mg QD. In 2 patients the baricitinib dosage was switched to 2 mg QD due to controlled disease. In the 2 other patients, the dosage was adjusted to 2 mg QD due to the development of AEs. Almost all patients (n = 25/28, 89.3%) were able to discontinue their concomitant immunosuppressive/immunomodulating therapy during baricitinib treatment. Due to inadequate response on baricitinib treatment, 2 patients still used prednisolone, of which 1 patient also used methotrexate. The other patient who was not able to stop the concomitant immunosuppressive treatment had a low dose of prednisolone 2.5 mg QD indicated for tertiary adrenal insufficiency. Of the patients who achieved week 16, 22.2% did not use any topical corticosteroids and almost half of the patients only used <10 g/week. In total, 17 (33.3%) patients discontinued baricitinib treatment due to ineffectiveness (week 4 (n = 2, 3.9%); week 8 (n = 10, 19.6%); week 16 (n = 5, 9.8%)) (Fig. 1). No significant difference in effect on the EASI, NRS-pruritus and NRS-pain, DLQI, POEM and PGADS over time was found between the dupilumab-NR and dupilumab-R/naïve group (Fig. 2B/Table SII).

Safety

In total 48 AEs were reported during 16 weeks of baricitinib treatment, of which 29 patients (56.9%) experienced at least 1 AE (Table III). The majority of AEs were evaluated as mild (77.1%). Most frequently reported AEs were nausea (n = 6, 11.8%), urinary tract infection (n = 5, 9.8%) and herpes simplex infections (n = 4, 7.8%). In 11 (21.6%) patients a laboratory abnormality was documented (Table III), mostly increased asymptomatic CPK levels (n = 5, 9.8%) or anaemia (n = 4, 7.8%). In total, 72.7% of the laboratory abnormalities resolved during the first 16 weeks of treatment. Five patients (9.8%) discontinued treatment due to 1 or more AEs (Fig. 1/Table III). One patient was diagnosed with a herpes simplex infection, which required oral treatment with valaciclovir. Another patient experienced severe nausea directly after baricitinib initiation, which resolved after discontinuing baricitinib. Furthermore, 1 patient experienced heart palpitations, which resolved after treatment discontinuation and 1 patient developed a corneal perforation due to a bacterial infection which required antibiotic ocular treatment and a bandage contact lens. In 1 patient a combination of AEs (acne, nausea and fatigue) resulted in treatment discontinuation.

Table III.

Reported adverse events and laboratory abnormalities during 16 weeks of baricitinib treatment

| Adverse events | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of AEs | 48 |

| Number of patients with AE | 29 (56.9) |

| Severity of AEs | |

| Mild | 37 (77.1) |

| Moderate | 7 (14.6) |

| Severe | 4 (8.3) |

| Number of patients with AE leading to treatment discontinuation | 5 (9.8) |

| Nausea | 1 (2.0) |

| Herpes simplex infection | 1 (2.0) |

| Corneal perforation due to bacterial infection | 1 (2.0) |

| Heart palpitations | 1 (2.0) |

| Combination of nausea, acne and headache | 1 (2.0) |

| Infections | 14 (27.5) |

| Urinary tract infection | 5 (9.8) |

| Herpes simplex | 4 (7.8) |

| Upper airway infection | 3 (5.9) |

| Dermatomycosis | 1 (2.0) |

| Corneal perforation due to bacterial infection | 1 (2.0) |

| Gastrointestinal | 12 (23.5) |

| Nausea | 6 (11.8) |

| Intestinal complaints | 3 (5.9) |

| Vomiting | 1 (2.0) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (2.0) |

| Reflux | 1 (2.0) |

| Laboratory abnormalities | 11 (21.6) |

| Increased CPKa | 5 (9.8) |

| Anaemiab | 4 (7.8) |

| Leukopaeniac | 1 (2.0) |

| Hypertriglyceridaemiad | 1 (2.0) |

| General | 6 (11.8) |

| Fatigue | 3 (5.9) |

| Night sweats | 1 (2.0) |

| Headache | 1 (2.0) |

| Heart palpitations | 1 (2.0) |

| Non-infectious skin-related | 2 (3.8) |

| Acne | 1 (2.0) |

| Hair regrowthe | 1 (2.0) |

| Other | 3 (5.9) |

| Conjunctivitis | 1 (2.0) |

| Muscle/joint pain | 1 (2.0) |

| Muscle weakness | 1 (2.0) |

Increase >3 times upper limit of normal (ULN).

Haemoglobin <8.5 mmol/l (men) or <7.5 mmol/l (women).

Leukocytes <2.0×109/l.

Triglycerides >2.0 mmol/l.

Referring to a patient with alopecia areata. Other reference categories: thrombocytosis >600× 109/l, neutropenia <1.0×109/l, lymphocytopaenia <0.5×109/l, ALAT 3× ULN, creatinine increase of >130%, hypercholesterolaemia >8.0 mmol/l.

AE: adverse event; CPK: creatinine phosphokinase.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first studies demonstrating the clinical effectiveness and safety of baricitinib treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe AD in a real-life setting, including patients with non-responsiveness to dupilumab. Overall, clinical outcome measures changed significantly over time, with a rapid improvement in the first 4 weeks of treatment. However, a considerable subset of patients (33.3%) discontinued treatment due to ineffectiveness. Five other (9.8%) patients discontinued treatment due to 1 or more AEs. Interestingly, no significant differences were found in effectiveness outcomes between dupilumab-NR and dupilumab-R/naïve. However, the dupilumab-NR group tended to have a slightly better response to baricitinib treatment. Further research in a larger cohort is necessary to define predictors for clinical response to baricitinib treatment.

Both clinician- and patient-reported outcomes significantly improved in the first 16 weeks of baricitinib treatment. It was found that the probability of achieving EASI≤7 and NRS-pruritus ≤4 significantly improved to 29.4% and 20.5%, respectively. In addition, the probability of achieving ADCT <7 (i.e. having controlled AD in the past week) was 33.0% and the PGADS≥3 was 70.0% (i.e. overall well-being regarding AD scored as good to excellent). However, the probability of achieving POEM ≤ 7 was quite low (4.8–6.6%), which might indicate that patients still experienced daily symptoms of AD. Another explanation could be that patients achieved a significant decrease on the primary continuous outcome without reaching the criteria for an absolute cut-off score. In total, 22 (43.2%) patients discontinued baricitinib treatment due to ineffectiveness and/or AEs. Therefore, baricitinib treatment might be an effective treatment option in the remaining subgroup of patients with AD.

It was found that the probability of achieving IGA≤ 1 was 22.2% and for DLQI≤ 5 (i.e. no or a small effect of AD on QoL) this was 31.4%. Clinical trials showed comparable percentages of patients achieving an IGA ≤ 1 (22.0–31.0%) (7, 8). However, the percentage of patients who achieved DLQI≤ 5 was higher in clinical trials (57.0%) (10). Other endpoints were difficult to compare with outcome measures used in clinical trials (e.g. EASI-75, improvement of ≥ 4 points on NRS-pruritus, POEM, and DLQI). Patients in clinical trials are selected based on strict eligibility criteria and patients with systemic immunosuppressive therapy at baseline are excluded. However, in the current daily practice study 54.9% of the patients still used concomitant immunosuppressive drugs at baseline. Therefore, we have made use of more absolute instead of relative outcomes. The use of concomitant immunosuppressive treatment in the current study cohort might indicate a more severe AD and causes possibly lower EASI scores at baseline. Furthermore, the washout of the concomitant immunosuppressive treatment in 25/28 patients may have resulted in an underestimation of the effect of baricitinib. Moreover, 74.5% of the patients had previously failed on dupilumab treatment, of which 68.4% failed due to ineffectiveness or a combination of ineffectiveness and AEs. For more than 3 years, no other advanced systemic therapy for AD was available. Therefore, our first patients treated with baricitinib, as second new advanced systemic therapy for AD on the market, were the most difficult-to-treat patients.

At present, only 2 small single-centre daily practice studies (n = 12 and n = 14), with limited clinical visits and outcome measures, have been published on the effectiveness and safety of baricitinib treatment (11, 12). The study of Rogner et al. (11) found a mean reduction in EASI score of 81.3% at week 16, while in the current study a decrease in mean EASI score from 18.3 to 11.1 was found. The study of Uchiyama et al. (12) found that 50% of the patients achieved IGA≤1 at week 12, which is higher compared with the results were the probability of achieving IGA≤1 was 16.1% at week 8 and 22.2% at week 16. In these studies, respectively, none (12) and only half of the patients (11) had previously been treated with systemic immunosuppressive therapy. This indicates that these patients might have had less difficult-to-treat AD compared with our patients, of which all had been previously treated with systemic immunosuppressive drugs and 47.1% had used ≥ 2 immunosuppressive drugs.

So far, there are no head-to-head studies available comparing the effectiveness of baricitinib with dupilumab. A recently published study reported on the results of an indirect treatment comparison (ITC) analysis between baricitinib and dupilumab based on clinical trial data (25). They found that baricitinib potentially results in a more rapid improvement in itch, while there were quite similar outcomes regarding DLQI and EASI-75 (25). Ariens et al. (26) found in a large daily practice cohort of 210 patients treated with dupilumab, that 44.6% of the patients achieved EASI≤7 after 4 weeks and 73.3% after 16 weeks of treatment. The NRS-pruritus ≤4 was achieved by 58.1% and 71.6% after 4 and 16 weeks of treatment, respectively. Compared with this daily practice study, the current study found a smaller effect of baricitinib on moderate-to-severe AD. However, in the study of Ariens et al. 25.2% of patients used concomitant immunosuppressive treatment at baseline, which is lower than in the current study (26).

Regarding safety analysis, 56.9% of the patients experienced at least 1 AE, which is similar to the ratio reported in clinical trials (51.0–58.0%) (7, 8, 27). Most frequently reported AEs were also in line with previous clinical and daily practice studies (e.g. urinary tract infection, herpes simplex infection, upper airway infection and increased CPK) (7, 8, 27). However, nausea was found in 6 (11.8%) patients, while it was reported in 0.8–2.8% of patients in clinical trials (27). In daily practice studies in which baricitinib was indicated for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), thrombotic events did occur, which was not seen in the current study (28). Other reported AEs in these daily practice RA studies were quite similar to the current study results (28, 29). Furthermore, most AEs (77.1%) reported in the current study were considered mild, although 5 patients needed to discontinue their treatment due to AEs (e.g. severe nausea, heart palpitations and an ocular bacterial infection with corneal perforation). In addition to the heart palpitations reported by 1 patient, safety analysis showed no new findings compared with clinical and daily practice studies.

Strengths of this study are the multicentre and prospective design, along with the use of many validated clinical outcomes and PROMs (at baseline and week-4/8/16 visits). Furthermore, this study might provide a better insight into the effect of baricitinib treatment in patients with more difficult-to-treat AD, including patients with non-responsiveness on dupilumab. A limitation of the study is the amount of missing data, partially caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which was covered by multiple imputation. In addition, the concomitant use of immunosuppressive therapy at baseline and the high discontinuation rate have influenced the current results, a bias could therefore not fully be excluded. Nevertheless, this is a reflection of real-world daily practice.

In conclusion, baricitinib can be an effective treatment option in a subgroup of adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD, including patients who had previously failed on dupilumab treatment. However, the effectiveness of baricitinib is rather heterogeneous, which is reflected by a high discontinuation rate in this difficult-to-treat cohort. In future, daily practice data is necessary to assess the long-term effectiveness and safety profile of baricitinib in patients with AD. More research, focused on patient profiling and predictors for clinical response on baricitinib treatment, is recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Patients included in this manuscript participated in the BioDay registry sponsored by Eli Lilly, Sanofi Genzyme, Leo Pharma, Abbvie and Pfizer.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: CMB is a speaker for Abbvie and Eli Lilly. BSB is a speaker for Sanofi Genzyme and LEO Pharma. LSS is a speaker for Abbvie. IMH is a consultant, advisory board member, and/or speaker for Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, AbbVie, Janssen and Eli Lilly. FMG was an advisory board member and/or speaker for AbbVie, LEO Pharma, Novartis and Sanofi Genzyme. KP is a consultant, advisory board member, and/or speaker for Sanofi Genzyme, Abbvie and LEO Pharma. MdG is a consultant, advisory board member, and/or speaker for Sanofi Genzyme and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Pfizer and Eli Lilly. MLAS is an advisor, consultant, speaker and/or investigator for AbbVie, Pfizer, LEO Pharma, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Eli Lilly and Galderma. She has received grants from Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Novartis and Pfizer. MSdB-W is a consultant, advisory board member, and/or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Aslan, Arena, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi-Genzyme. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, Girolomoni G, Puig L, Simpson EL, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy 2018; 73: 1284–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, Loman L, Voorberg AN, Schuttelaar MLA. Prevalence of adult atopic dermatitis in the general population, with a focus on moderate-to-severe disease: results from the Lifelines Cohort Study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35: e787–e790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiedinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016; 387: 1109–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thaci D, Simpson EL, Beck LA, Bieber T, Blauvelt A, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 40–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domaingroup Allergy and Eczema and association for Atopic Dermatitis (VMCE), the Netherlands . Dupilumab (opinion) December 2020 [accessed 2022 Jun 20]. Available from https://nvdv.nl/professionals/nvdv/standpunten-en-leidraden/introductie-van-dupilumab-voor-ernstig-constitutioneel-eczeem-ce-standpunt.

- 6.Domaingroup Allergy and Eczema and assocation for Atopic Dermatitis (VMCE), the Netherlands . Baricitinib (opinion). December 2020 [accessed February 25, 2022]. Available from https://nvdv.nl/professionals/nvdv/standpunten-enleidraden/baricitinib-standpunt.

- 7.Simpson EL, Lacour JP, Spelman L, Galimberti R, Eichenfeld LF, Bissonnette R, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183: 242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reich K, Kabashima K, Peris K, Silverberg JI, Eichenfeld LF, Bieber T, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib combined with topical corticosteroids for treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol 2020; 156: 1333–1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guttman-Yassky E, Silvergberg JI, Nemoto O, Forman SB, Wilke A, Prescilla R, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019. 90: 913–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wollenberg A, Nakahara T, Maari C, Peris K, Lio P, Augustin M, et al. Impact of baricitinib in combination with topical steroids on atopic dermatitis symptoms, quality of life and functioning in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis from the BREEZE-AD7 Phase 3 randomized trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35: 1543–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogner D, Biedermann T, Lauffer F. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with baricitinib: first real-life experience. Acta Derm Venereol 2022; 102: adv00677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchiyama A, Fujiwara C, Inoue Y, Motegi SI. Real-world effectiveness and safety of baricitinib in Japanese patients with atopic dermatitis: a single-center retrospective study. J Dermatol 2022; 49: 469–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leshem YA, Hajar T, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL. What the Eczema Area and Severity Index score tells us about the severity of atopic dermatitis: an interpretability study. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172: 1353–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994; 19: 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients’ perspective. Arch Dermatol 2004; 140: 1513–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phan NQ, Blome C, Fritz F, Gerss J, Reich A, Ebata T, et al. Assessment of pruritus intensity: prospective study on validity and reliability of the visual analogue scale, numerical rating scale and verbal rating scale in 471 patients with chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol 2012; 92: 502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths C, de Bruin-Weller M, Deleuran M, Concetta Fargnoli M, Staumont-Sallé D, Hong CH. Dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and prior use of systemic non-steroidal immunosuppressants: analysis of four phase 3 trials. Dermatol Ther 2021; 11: 1357–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pariser DM, Simpson EL, Gadkari A, Bieber T, Margolis DJ, Brown M, et al. Evaluating patient-perceived control of atopic dermatitis: design, validation, and scoring of the Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT). Curr Med Res Opin 2020; 36: 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Bruin-Weller M, Biedermann T, Bissonnette R, Deleuran M, Foley P, Girolomoni G, et al. Treat-to-target in atopic dermatitis: an international consensus on a set of core decision points for systemic therapies. Acta Derm Venereol 2021; 17: 101–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Futamara M, Leshem YA, Thomas KS, Nankervis H, Williams HC, Simpson EL. A systematic review of Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) in atopic dermatitis (AD) trials: many options, no standards. JAAD 2016; 74: 288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donders ART, Van der Heijden GJMG, Stijnen T, Moons KGM. Review: a gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J Clin Epidemiol 2006; 59: 1087–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prev Sci 2007; 8: 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rstudio . Available from: https://www.rstudio.com.

- 24.Robitzsch A, Grund S. (2022). miceadds: Some Additional Multiple Imputation Functions, Especially for ‘mice’. R package version 3.13-1. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=miceadds.

- 25.De Bruin-Weller MS, Serra-Baldrich E, Barbarot S, Grond S, Schuster G, Petto H, et al. Indirect treatment comparison of baricitinib versus dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther 2022; 12: 1481–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ariens LFM, Van der Schaft J, Spekhorst LS, Bakker DS, Romeijn GLE, Kouwenhoven TA. Dupilumab shows long-term effectiveness in a large cohort of treatment-refractory atopic dermatitis patients in daily practice: 52-week results from the Dutch BioDay registry. J Am Acad Dematol 2021; 84: 1000–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bieber T, Thyssen JP, Reich K, Simpson EL, Katoh N, Torrelo A, et al. Pooled safety analysis of baricitinib in adult patients with atopic dermatitis from 8 randomized clinical trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35: 476–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guidelli GM, Viapiana O, Luciano N, de Santis M, Boffini N, Quartuccio L, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib in 446 patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a real-life multicentre study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2021; 39: 868–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwamoto N, Sato S, Kurushima S, Michitsuij T, Nishihata S, Okamoto M, et al. Real-world comparative effectiveness and safety of tofacitinib and baricitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2021; 23: 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]