Abstract

Strains of Escherichia coli producing Shiga toxins Stx1, Stx2, Stx2c, and Stx2d cause gastrointestinal disease and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome in humans. We have recently constructed a recombinant bacterium which displays globotriose (the receptor for these toxins) on its surface and adsorbs and neutralizes these Shiga toxins with very high efficiency. This agent has great potential for the treatment of humans with such infections. E. coli strains which cause edema disease in pigs produce a variant toxin, Stx2e, which has a different receptor specificity from that for the other members of the Stx family. We have now modified the globotriose-expressing bacterium such that it expresses globotetraose (the preferred receptor for Stx2e) by introducing additional genes encoding a N-acetylgalactosamine transferase and a UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine-4-epimerase. This bacterium had a reduced capacity to neutralize Stx1 and Stx2c in vitro, but remarkably, its capacity to bind Stx2e was similar to that of the globotriose-expressing construct; both constructs neutralized 98.4% of the cytotoxicity in lysates of E. coli JM109 expressing cloned stx2e. These data suggest that either globotriose- or globotetraose-expressing constructs may be suitable for treatment and/or prevention of edema disease in pigs.

Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains are important enteric pathogens. In humans they cause diarrhea and hemorrhagic colitis, and these can progress to potentially fatal systemic sequelae, such as the hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) (6, 10, 11, 16). HUS is characterized by the triad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal failure, and it is a leading cause of acute renal failure in children (6). During infections STEC strains colonize the gut and release Stx into the gut lumen; the STEC strains do not invade the gut mucosa, but toxin is absorbed into the circulation and targets tissues displaying the appropriate glycolipid receptor (particularly the microvasculature of the gut, kidneys, and brain). This accounts for both the severe gastrointestinal symptoms and the systemic manifestations of STEC disease. There are several distinct classes of Stx which differ in amino acid sequence. All Stx types associated with human disease (Stx1, Stx2, Stx2c, and Stx2d) recognize the same glycolipid receptor, globotriaosyl ceramide (Gb3), which has the structure Galα(1→4)Galβ(1→4)Glc-ceramide (7). In a recent study we exploited this specificity to develop a recombinant bacterium expressing a mimic of the Gb3 oligosaccharide on its surface (13). This involved insertion of a plasmid (pJCP-Gb3) carrying two Neisseria galactosyltransferase genes, lgtC and lgtE (2), into a derivative of E. coli R1 (CWG308), which has a waaO mutation in the outer core lipopolysaccharide (LPS) biosynthesis locus such that a truncated LPS core terminating in glucose (Glc) is produced (3). Expression of lgtC and lgtE resulted in the linkage of Galα(1→4)Galβ(1→4) onto the terminal Glc. This bacterium adsorbed and neutralized Stx1, Stx2, Stx2c, and Stx2d with very high efficiency in vitro, and oral administration protected mice from an otherwise fatal challenge with highly virulent STEC strains (13). Oral administration of this novel agent to individuals diagnosed with, or at risk for, STEC infection has the potential to adsorb and neutralize free Stx in the gut lumen, thereby preventing absorption of toxin into the bloodstream and the concomitant life-threatening systemic sequelae associated with STEC disease in humans.

The above construct, however, was somewhat less effective at neutralizing the variant toxin Stx2e produced by STEC strains associated with piglet edema disease. This was not unexpected, since Stx2e has a different receptor specificity, recognizing globotetraosyl ceramide [Gb4; GalNAcβ(1→3)Galα(1→4)Galβ(1→4)-Glc-ceramide] preferentially over Gb3 (1). Piglet edema disease is a serious, frequently fatal STEC-related illness characterized by neurological symptoms, including ataxia, convulsions, and paralysis; edema is typically present in the eyelids, brain, stomach, intestine, and mesentery of the colon. It is caused by particular STEC serotypes (most commonly O138:K81, O139:K82, and O141:K85) which are not associated with human disease (4, 9). The altered glycolipid receptor specificity affects the tissue tropism of the toxin, accounting for the distinctive clinical presentation of edema disease. Edema disease occurs principally at the time of weaning, and so incorporation of an effective Stx2e binding agent into the feed should be a means of preventing disease outbreaks and the associated economic losses. Accordingly, in the present study we have constructed a recombinant bacterium expressing globotetraose on its surface and examined its capacity to bind and neutralize Stx2e in vitro.

Construction of an E. coli CWG308 derivative expressing GalNAcβ(1→3)Galα(1→4)Galβ(1→4)Glc.

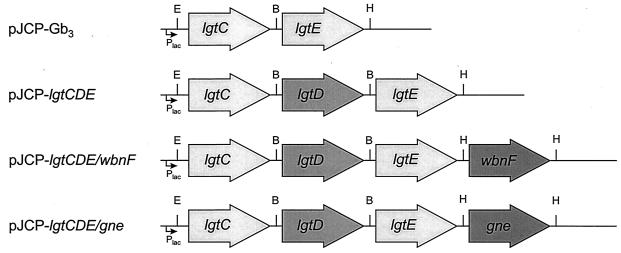

Globotetraose differs from globotriose only by the additional N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) linked 1→3 to the terminal galactose (Gal). Thus, insertion of a gene encoding the appropriate GalNAc transferase into pJCP-Gb3 would be expected to direct globotetraose expression when the plasmid is introduced into CWG308. The Neisseria lgt locus includes such a gene (lgtD), but this contains a poly(G) tract and so is unstable because of susceptibility to slipped-strand mispairing (2, 19). To overcome this we mutagenized the lgtD gene by overlap extension PCR, using N. gonorrhoeae chromosomal DNA as the template. The 5′ portion of lgtD was amplified using the primers 5′-CAGACGGGATCCGACGTATCGGAAAAGGAGAAAC-3′ (LGTDF), incorporating a BamHI site (underlined), and 5′-GCGCGCAATATATTCACCGCCACCCGACTTTGCC-3′ (LGTDOLR). The 3′ portion of lgtD was amplified using the primers 5′-GGCAAAGTCGGGTGGCGGTGAATATATTGCGCGC-3′ (LGTDOLF) and 5′-CATGATGGATCCTGTTCGGTTTCAATAGC-3′ (LGTDR), also incorporating a BamHI site. PCR was performed using the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) under conditions recommended by the supplier. The two PCR products were then purified, aliquots were mixed, and the complete lgtD coding sequence with the desired modifications was amplified using the primers LGTDF and LGTDR. This procedure mutates GGG codons in the poly(G) tract to GGT or GGC (all of which encode Gly), eliminating the risk of slipped-strand mispairing without changing the encoded amino acid sequence. The modified PCR product was digested with BamHI and cloned into similarly digested pJCP-Gb3 between lgtC and lgtE, as shown in Fig. 1, and then it was transformed into E. coli JM109 (20). Insertion of lgtD with the correct mutations and the appropriate orientation was confirmed by sequence analysis of plasmid DNA using custom-made oligonucleotide primers and dye terminator chemistry on an ABI model 377 automated DNA sequencer. This plasmid (designated pJCP-lgtCDE) was then transformed into E. coli CWG308.

FIG. 1.

Construction of pJCP-Gb3 derivatives. pJCP-Gb3 is a derivative of pK184 (5) carrying Neisseria lgtC and lgtE, as described previously (13). The N. gonorrhoeae lgtD gene was amplified and mutagenized to stabilize its poly(G) tract by overlap extension PCR and cloned into the BamHI site between lgtC and lgtE to generate pJCP-lgtCDE. wbnF and gne genes were then amplified from E. coli O113 and cloned into the HindIII site downstream of lgtE to generate pJCP-lgtCDE/wbnF and pJCP-lgtCDE/gne, respectively. Restriction sites: E, EcoRI; B, BamHI; H, HindIII. All genes are in the same orientation and are located immediately downstream of the vector promoter (Plac).

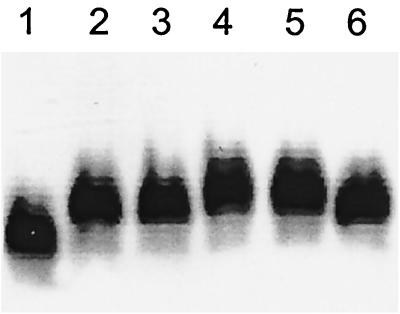

LPS was then purified from the above strain as well as from E. coli CWG308 and CWG308:pJCP-Gb3 and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with silver staining as previously described (8). While there was a clear difference in mobility of the LPS from CWG308 and CWG308:pJCP-Gb3, expression of the additional transferase gene in CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE did not further retard LPS mobility (Fig. 2). This could be explained either by failure to produce functional LgtD or by the absence of the essential precursor UDP-GalNAc. This would require a functional UDP-GalNAc-4-epimerase, an enzyme not necessarily present in all E. coli strains. In a previous study (14) we described the genetic locus for biosynthesis of E. coli O113 O antigen, the repeat unit structure of which includes GalNAc. This locus contains two genes (designated gne and wbnF) encoding proteins with similarity to nucleotide sugar epimerases, and we postulated that one or the other of these may be a functional UDP-GalNAc-4-epimerase. We therefore amplified the gne and wbnF genes from E. coli O113 chromosomal DNA using the primers 5′-TTTATTAAGCTTCCAATTAAGGAGGTAACTC-3′ and 5′-AATTACAAGCTTATAATTTTAATTACCATACCC-3′ for gne and primers 5′-ATATTCAAGCTTGAGTGAGGATTATAAATGAAATT-3′ and 5′-TTTCTTAAGCTTTTGTAAAATCAAACTTTATAGAAG-3′ for wbnF (each primer incorporates a HindIII site, underlined). Each PCR product was purified, digested with HindIII, ligated with HindIII-digested pJCP-lgtCDE (Fig. 1), and then transformed into E. coli JM109. Correct insertion and orientation of each construct (designated pJCP-lgtCDE/gne and pJCP-lgtCDE/wbnF) were confirmed by sequence analysis, and then each plasmid was transformed into CWG308. Comparison of the electrophoretic mobility of LPS purified from these recombinant strains (Fig. 2) indicated that expression of the gne gene resulted in an increase in the molecular size of the LPS. This gene was originally designated galE (14) because it encoded a product with a high degree of similarity to putative GalE proteins (UDP-Glc-4-epimerases) from a large number of bacteria, the most closely related being that from Yersinia enterocolitica O:8 (57% identity and 73% similarity) (22). However, the Yersinia galE gene is now designated gne on the Bacterial Polysaccharide Gene Database (available at www.microbio.usyd.edu.au/BPGD/default.htm), and the function of its product is listed as a UDP-GalNAc-4-epimerase. Given the high degree of similarity between the Yersinia and E. coli O113 proteins and the fact that LgtD is a proven GalNAc transferase (2), we conclude that galE from the E. coli O113 rfb locus also encodes a functional UDP-GalNAc-4-epimerase, and accordingly it has been renamed gne.

FIG. 2.

Silver-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of LPS purified from E. coli CW308 derivatives. Lanes: 1, CWG308; 2, CWG:308-pJCP-Gb3; 3, CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE; 4 and 5, CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE/gne (two separate preparations); 6, CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE/wbnF. Each lane contains approximately 3 μg of LPS.

Adsorption and neutralization of Stx.

The capacity of the above CWG308 derivatives to adsorb and neutralize various Stx types was then assessed. Filter-sterilized French pressure cell (FPC) lysates of E. coli JM109:pJCP522 (12) and JM109:pJCP521 (15) were used as a source of Stx1 and Stx2c, respectively. For Stx2e, we first PCR-amplified the complete stx2e operon from chromosomal DNA extracted from an O141 STEC strain isolated from a piglet with edema disease. The primers used were 5′-GCATCATGCGTTGTTAGCTC-3′ and 5′-AAAGACGCGCATAAATAAACCG-3′. The PCR product was purified, blunt-cloned into SmaI-digested pBluescript SK (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and then transformed into E. coli JM109. The insert of this plasmid (designated pJCP543) was sequenced and found to be identical to the sequence previously published for stx2e (18), except for a single nucleotide substitution in the A subunit coding region which did not affect the amino acid sequence. Accordingly, an FPC lysate of JM109:pJCP543 was used as a source of Stx2e. The crude Stx extracts were prepared by growing the various E. coli JM109 derivatives in 10 ml of Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 50 μg of ampicillin/ml overnight at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2 (PBS), and lysed in an FPC operated at 12,000 lb/in2. Lysates were then sterilized by passage through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter.

E. coli CWG308, CWG308:pJCP-Gb3, CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE, CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE/gne, and CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE/wbnF were then grown overnight in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 20 μg of isopropyl-β-d(thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)/ml and 50 μg of kanamycin/ml (except for CWG308). Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in PBS at a density of 109 CFU/ml. Aliquots (250 μl) of the Stx1, Stx2c, and Stx2e extracts were incubated with 500 μl of each of the above suspensions or PBS for 1 h at 37°C with gentle agitation. The mixtures were then centrifuged and the supernatants were filter sterilized. The cytotoxicity of the supernatant fraction was then assayed using Vero (African green monkey kidney) cells, which are highly susceptible to all Stx-related toxins (6). Twelve serial twofold dilutions were prepared in tissue culture medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium buffered with 20 mM HEPES and supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 IU of penicillin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml), commencing at a dilution of 1:1 for Stx2e or 1:20 for Stx1 or Stx2c. Fifty microliters of each dilution was transferred onto washed Vero cell monolayers in 96-well tissue culture trays, and after 30 min of incubation at 37°C, a further 150 μl of culture medium was added to each well. Cells were examined microscopically after 72 h of incubation at 37°C and scored for cytotoxicity. The endpoint Stx titer (cytotoxic doses [CD] per milliliter) was defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution resulting in cytotoxicity in at least 10% of the cells in a given monolayer. As a permanent record, cell monolayers were then fixed in 3.8% formaldehyde–PBS and stained with crystal violet. The percentage of Stx adsorbed or neutralized was calculated using the formula 100 − (100 × CDcells ÷ CDPBS), where CDcells is the Stx titer in the extracts incubated with the CWG308 derivatives and CDPBS is the Stx titer in the respective Stx extract treated only with PBS. As shown in Table 1, CWG308 exhibited no neutralization activity, whereas CWG308:pJCP-Gb3 bound 99.9, 99.2, and 98.4% of the cytotoxicity of Stx1, Stx2c, and Stx2e, respectively. This is in accordance with our previous findings for this globotriose-expressing construct (13) except for a slightly improved neutralization of Stx2e. In our previous study we observed 87.5% neutralization using a crude lysate of a wild-type STEC isolate from a case of edema disease as a source of Stx2e, but some of the residual cytotoxicity may have been due to the presence of other toxic substances. Neutralization of the various toxin types was not significantly diminished for CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE and CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE/wbnF, which was not surprising given that polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis indicated that the LPS from both of these strains was indistinguishable from that of CWG308:pJCP-Gb3. However, neutralization of both Stx1 and Stx2c was significantly lower for CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE/gne, which is consistent with the altered electrophoretic mobility of its LPS. Interestingly, it exhibited the same in vitro neutralization activity against Stx2e as the other constructs (98.4%), in spite of expression of what has hitherto been believed to be the preferred receptor for this toxin type.

TABLE 1.

Neutralization of Stx

| E. coli strain | % Stx neutralizeda

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stx1 | Stx2c | Stx2e | |

| CWG308 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CWG308:pJCP-Gb3 | 99.9 | 99.2 | 98.4 |

| CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE | 99.9 | 98.4 | 98.4 |

| CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE/wbnF | 99.8 | 98.4 | 98.4 |

| CWG308:pJCP-lgtCDE/gne | 96.9 | 87.5 | 98.4 |

Toxin neutralization was assayed using Vero cells as described in the text. Assays were performed in duplicate with identical results. Untreated toxin extracts had endpoint titers of 656,000, 164,000, and 62,000 CD/ml for Stx1, Stx2c, and Stx2e, respectively.

Conclusions.

In the present study we have modified the globotriose-expressing bacterium CWG308:pJCP-Gb3 so that it expresses globotetraose (the preferred receptor for Stx2e) by introducing additional genes encoding a GalNAc transferase (lgtD) and a UDP-GalNAc-4-epimerase (gne). The addition of an extra sugar residue to the outer LPS core required both genes and was demonstrated by electrophoretic analysis. Furthermore, the fact that the LPS migrated as a single species implied that this reaction proceeds to completion. The globotetraose-expressing bacterium had a reduced capacity to neutralize Stx1 and Stx2c in vitro, presumably because the terminal GalNAc residue sterically hinders the interaction between the Stx B subunit and the (now subterminal) globotriose moiety. However, its capacity to bind Stx2e was similar to that of the globotriose-expressing construct: both neutralized 98.4% of the cytotoxicity in lysates of E. coli JM109 expressing cloned stx2e. It has long been held that the piglet edema disease-associated toxin Stx2e has a higher affinity for Gb4 than for Gb3 (1, 7, 17). Thus, the findings of this study were somewhat unexpected. Some of the early studies on Stx receptor specificity involved overlaying glycolipids separated by thin-layer chromatography with toxin. However, it has been suggested that the polyisobutylmethacrylate used in these studies (to stabilize the silica gel prior to reaction of the separated lipids with toxin) may have induced conformational changes in the carbohydrate moieties which affected toxin-receptor interactions (21). Receptor specificity was also examined on the basis of susceptibility of cell lines containing various amounts of Gb3 and Gb4 to the toxin. Interestingly, fatty acyl chain length is known to influence the interaction of Gb3 with Stx1 and Stx2 to different extents, and so it is possible that factors other than the structure of the oligosaccharide component may have been compounding factors in the cell culture studies (7). In the present study the globotriose and globotetraose moieties were expressed on an otherwise identical platform comprising the inner core oligosaccharide and the lipid A components of E. coli LPS. Thus, differences in toxin-receptor interactions (or lack thereof) truly reflect the impact of oligosaccharide structure and conformation. Of course, the protective efficacy of oral administration of recombinant bacteria expressing mimics of Stx receptors needs to be examined in a piglet edema disease challenge model. On the basis of the results obtained in this study, it is clear that both the globotriose- and the globotetraose-expressing constructs should be tested.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Chris Whitfield for providing E. coli CWG308 and to Elizabeth Parker for assistance with purification and analysis of LPS.

This work was supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the Channel Seven Children's Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.DeGrandis S, Law H, Brunton J, Gyles C, Lingwood C A. Globotetraosyl ceramide is recognized by the pig edema disease toxin. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12520–12525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gotschlich E C. Genetic locus for the biosynthesis of the variable portion of Neisseria gonorrhoeae lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2181–2190. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinrichs D E, Yethon J A, Amor P A, Whitfield C. The assembly system for the outer core portion of R1- and R4-type lipopolysaccharides of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29497–29505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imberechts H, de Greve H, Lintermans P. The pathogenesis of edema disease in pigs. A review. Vet Microbiol. 1992;31:221–233. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(92)90080-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jobling M G, Holmes R K. Construction of vectors with the p15a replicon, kanamycin resistance, inducible lacZα and pUC18 or pUC19 multiple cloning sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5315–5316. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.17.5315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karmali M A. Infection by verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:15–38. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lingwood C A. Role of verotoxin receptors in pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morona R, Brown M H, Yeadon J, Heuzenroeder M W, Manning P A. Effect of lipopolysaccharide core synthesis mutations on the production of Vibrio cholerae O-antigen in Escherichia coli K-12. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;66:279–285. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90274-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morris J A, Sojka W J. Escherichia coli as a pathogen in animals. In: Sussman M, editor. The virulence of Escherichia coli. London, United Kingdom: Society for General Microbiology, Academic Press; 1985. pp. 47–77. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien A D, Holmes R K. Shiga and Shiga-like toxins. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:206–220. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.206-220.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paton A W, Beutin L, Paton J C. Heterogeneity of the amino-acid sequences of Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin type-I operons. Gene. 1995;153:71–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00777-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paton A W, Morona R, Paton J C. A new biological agent for treatment of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli infections and dysentery in humans. Nat Med. 2000;6:265–270. doi: 10.1038/73111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paton A W, Paton J C. Molecular characterization of the locus encoding biosynthesis of the lipopolysaccharide O antigen of Escherichia coli serotype O113. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5930–5937. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5930-5937.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paton A W, Paton J C, Manning P A. Polymerase chain reaction amplification, cloning and sequencing of variant Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin type II operons. Microb Pathog. 1993;15:77–82. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paton J C, Paton A W. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:450–479. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samuel J E, Perera L P, Ward S, O'Brien A D, Ginsburg V, Krivan H C. Comparison of the glycolipid receptor specificities of Shiga-like toxin type II and Shiga-like toxin type II variants. Infect Immun. 1990;58:611–618. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.3.611-618.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstein D L, Jackson M P, Samuel J E, Holmes R K, O'Brien A D. Cloning and sequencing of a Shiga-like toxin type II variant from an Escherichia coli strain responsible for edema disease of swine. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4223–4230. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4223-4230.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Q-L, Gotschlich E C. Variation of gonococcal lipooligosaccharide structure is due to alterations in poly-G tracts in lgt genes encoding glycosyl transferases. J Exp Med. 1996;183:323–327. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yiu S C K, Lingwood C A. Polyisobutylmethacrylate modifies glycolipid binding specificity of verotoxin 1 in thin-layer chromatogram overlay procedures. Anal Biochem. 1992;202:188–192. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90226-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Toivanen P, Skurnik M. The gene cluster directing O-antigen biosynthesis in Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:8: identification of the genes for mannose and galactose biosynthesis and the gene for the O-antigen polymerase. Microbiology. 1996;142:277–288. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]