Abstract

Background:

Limited epidemiological data exist describing how patients engage with various treatments for overactive bladder (OAB). In order to improve care for patients with OAB, it is essential to gain a better understanding of how patients interface with OAB treatments longitudinally, i.e. how often patients change treatments and the pattern of this treatment change in terms of escalation and de-escalation.

Objectives:

To describe treatment patterns for women with bothersome urinary urgency (UU) and/or urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) presenting to specialty care over one-year.

Study design:

The Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN) study enrolled adult women with bothersome UU and/or UUI seeking care for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) between January 2015 and September 2016. An ordinal logistic regression model was fitted to describe the probabilities of escalating or de-escalating level of treatment during one-year follow-up.

Results:

Among 349 women, 281 reported UUI, and 68 reported UU at baseline. At the end of one-year of treatment by a urologist or urogynecologist, the highest level of treatment received by participants was: 5% expectant management, 36% behavioral treatments (BT), 26% physical therapy (PT), 26% OAB medications, 1% percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, 3% intradetrusor onabotulinum toxin A injection, and 3% sacral neuromodulation. Participants using BT or PT at baseline were more likely to be de-escalated to no treatment than participants on OAB medications at baseline, who tended to stay on medications. Predictors of the highest level of treatment included starting level of treatment, hypertension, UUI severity, stress urinary incontinence, and anticholinergic burden score.

Conclusions:

Treatment patterns for UU and UUI are diverse. Even for patients with significant bother from OAB presenting to specialty clinics, further treatment often only involves conservative or medical therapies. This study highlights the need for improved treatment algorithms to escalate patients with persistent symptoms, or to adjust care in those who have been unsuccessfully treated.

Keywords: discontinuation, therapy, treatment outcome, urge incontinence, urgency

Introduction

The lifetime prevalence of overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) in women is approximately 30%.1 OAB encompasses lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as urinary urgency (UU), frequency, nocturia, and urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). Patients who report OAB symptoms are often managed with multiple treatments; however, similar to other chronic diseases,2 patient willingness to try therapies with possible side effects or risks and adherence to treatments is poor with discontinuation rates of medications nearing 50% by the first month of treatment.3 Although several studies have reported an association between clinical improvement and treatment adherence, these studies need to be interpreted cautiously as this association may reflect treatment bias or compliance bias.4, 5

Limited epidemiological data exist describing how patients engage with various OAB treatments. Many factors, including patient, provider, payer, and treatment-effect, influence what kind of treatments patients are offered or have access to and when patients start, stop, or change treatments.6–9 In order to improve care for patients with OAB and identify potentially modifiable barriers to treatment, it is essential to gain a better understanding of how patients interface with OAB treatments longitudinally, i.e. how often patients change treatments and the pattern of this treatment change in terms of escalation and de-escalation. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to describe the treatment patterns for UU and/or UUI women presenting to specialty care over one year using data from the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN).

Materials and Methods:

Study sample

LURN is a multi-center research network that performed a one-year prospective observational cohort study of adults seeking specialty care, i.e. care from a urogynecologist or urologist specializing in management of LUTS, between January 2015 and September 2016.10 Patients were eligible if they reported at least one urinary symptom in the past month based on the LUTS Tool and were seeking care from a LURN physician for the first time. The LUTS Tool comprises 44 questions on severity and bother of LUTS.11 12 Additional study inclusion and exclusion criteria have been previously published.13 After a baseline visit, participants were contacted for a follow-up visit every three months for one year. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

The current study only included those women who reported bothersome UU or UUI. Participants with UU were identified if they reported a “sudden need to rush to urinate” (Q6 on the LUTS Tool) or a “sudden need to rush to urinate for the fear of leaking” (Q12) during the past month, while participants were categorized as having UUI if they responded “sometimes”, “often”, or “always” on Q16b – “leaked urine in connection with a sudden need to rush to urinate”. Women were included in this cohort if they reported of “sometimes”, “often”, or “always” on the LUTS Tool and also reported bothersome UU or UUI which was defined as “somewhat”, “quite a bit”, or “a great deal” bothered.

Treatment for LUTS

Participant-reported treatments for LUTS were collected at baseline and every three months for one year including start and stop dates for medications and procedure dates. Treatments of interest for this study included: (1) behavioral therapy (BT), (2) prescribed course of pelvic floor physical therapy (PT) with a trained therapist, (3) OAB medications, (4) percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), (5) intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA injection, and (6) sacral neuromodulation (SNM). These treatments were ordered from 1 to 6, respectively, reflecting existing recommended treatment paradigms from conservative to aggressive or from least procedurally intensive to most surgically intensive.14 Treatment grouping was also performed for BT and OAB medications and these are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA was assumed to be effective for six months from the last procedure date. Participants on SNM were assumed to continue SNM therapy unless the device was removed.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes for this study were treatment escalation and de-escalation from baseline to follow-up. Escalation was defined as an increase in treatment level (e.g. from level 1=BT to level 3=OAB medication), whereas de-escalation was defined as a decrease in treatment level (e.g. from level 3=OAB medication to level 1=BT).

Independent Variables

Demographic variables included age at study enrollment, race, and education. The following baseline clinical characteristics were also collected: 1) Body Mass Index (BMI); 2) comorbidities (history of hypertension, diabetes, psychiatric diagnosis, stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), and hyperlipidemia); 3) use of diuretics; 4) anticholinergic burden (ACB) score 15; 5) UU and UUI symptom severity questions from the LUTS Tool; 6) stress urinary incontinence (average of LUTS Tool items related to leaking urine in connection with laughing, sneezing, or coughing, and in connection with physical activities, such as exercising or lifting a heavy object); 7) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures 16 (gastrointestinal bowel incontinence and diarrhea, constipation, depression, anxiety, physical functioning, and sleep disturbance measures); 8) quality of life due to urinary symptoms as measured by Q8 of the American Urological Association Symptom Index;17 and 9) the Perceived Stress Scale 18.

Statistical Analyses

The highest level of treatment at each visit was plotted in a lasagna plot to show treatment patterns over time. The percentage of participants with treatment escalation and de-escalation between visits were calculated and presented using bar charts. Denominators of these percentages were the number of participants with treatment data from two consecutive visits, and numerators were the number of participants who had treatment escalation or de-escalation. To obtain predicted probabilities of treatment escalation and de-escalation from baseline to study follow-up, we fit a multivariable ordinal logistic regression model predicting the highest level of treatment during study follow-up using baseline characteristics. The ordinal logistic regression model was used to obtain predicted probabilities of each level of treatment from one unified model. For each participant, escalation (de-escalation) probabilities were obtained by summing up the predicted probabilities of all higher (lower) levels of treatment from their baseline level of treatment.

Candidate predictors were selected with clinical input. Model selection used backward elimination. Covariates significant at 0.10 level were included in the final model. To adjust for baseline treatments, level of treatment at baseline and prior sling placement at baseline were included as predictors regardless of p-value.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results:

Among the 545 women enrolled in LURN, 349 women presented with bothersome UU or UUI; 281 had bothersome UUI (i.e. OAB-wet) and 68 had bothersome UU alone (i.e. OAB-dry) at baseline (Table 1). Mean (± SD) age was 57 (± 15) years and participants were mostly white (80%) and non-Hispanic (95%). Mean (± SD) BMI was 31.6 (± 8.2) kg/m2. Prior to or at the time of their baseline visit, 69% of participants reported undergoing BT and 13% reported PT (Table 1). At baseline, 10% were taking OAB medications (our data set cannot ascertain how many had previously tried these medications). Few participants had tried PTNS (n=1), intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA (n=2), or SNM surgeries (n=1). Ten percent reported a history of previous sling surgery prior to baseline.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics at baseline

| Total (n=349) | Urinary urgency with urgency incontinence (n=281) | Urinary urgency without urgency incontinence (n=68) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Demographics | |||

| Age in years | 57.1 (14.6) | 57.6 (14.0) | 54.9 (16.6) |

| Race β | |||

| Black/African-American | 48 (14%) | 40 (14%) | 8 (12%) |

| Other | 22 (6%) | 17 (6%) | 5 (7%) |

| White | 278 (80%) | 223 (80%) | 55 (81%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latina | 12 (3%) | 9 (3%) | 3 (4%) |

| Non-Hispanic/Non-Latina | 330 (95%) | 265 (94%) | 65 (96%) |

| Ethnicity unknown | 7 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Education β | |||

| < HS Diploma/GED | 9 (3%) | 7 (3%) | 2 (3%) |

| HS Diploma/GED | 33 (10%) | 29 (10%) | 4 (6%) |

| Some college/tech school - no degree | 92 (27%) | 77 (28%) | 15 (23%) |

| Associates degree | 40 (12%) | 31 (11%) | 9 (14%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 96 (28%) | 81 (29%) | 15 (23%) |

| Graduate degree | 75 (22%) | 54 (19%) | 21 (32%) |

| Physical Exam and Clinical Information | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) β | 31.6 (8.2) | 32.0 (8.4) | 29.5 (6.6) |

| Current Smoker β | 29 (8%) | 24 (9%) | 5 (7%) |

| Former Smoker β | 95 (27%) | 77 (28%) | 18 (26%) |

| Number of alcoholic drinks per week in the past year γ | |||

| Has not had alcohol in the past year | 69 (20%) | 55 (20%) | 14 (21%) |

| 0 to 3 drinks per week | 222 (65%) | 179 (65%) | 43 (64%) |

| 4 to 7 drinks per week | 38 (11%) | 30 (11%) | 8 (12%) |

| >= 8 drinks per week | 13 (4%) | 11 (4%) | 2 (3%) |

| Hypertension β | 139 (40%) | 120 (43%) | 19 (28%) |

| Diabetes | 58 (17%) | 46 (16%) | 12 (18%) |

| Psychiatric Diagnosis β | 153 (44%) | 130 (46%) | 23 (34%) |

| History of Stroke or TIA β | 15 (4%) | 13 (5%) | 2 (3%) |

| Hyperlipidemia β | 110 (32%) | 88 (31%) | 22 (32%) |

| On diuretics | 52 (15%) | 44 (16%) | 8 (12%) |

| IPAQ γ | |||

| Low activity | 194 (57%) | 161 (59%) | 33 (50%) |

| Moderate activity | 43 (13%) | 36 (13%) | 7 (11%) |

| High activity | 101 (30%) | 75 (28%) | 26 (39%) |

| LUTS Treatment | |||

| Treatment prior to or at baseline (not mutually exclusive) | |||

| Behavioral therapy | 240 (69%) | 195 (69%) | 45 (66%) |

| Pelvic floor physical therapy | 47 (13%) | 39 (14%) | 8 (12%) |

| OAB medication # | 36 (10%) | 29 (10%) | 7 (10%) |

| PTNS | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| Botox | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| SNM | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Sling | 36 (10%) | 28 (10%) | 8 (12%) |

Table values are mean (standard deviation) or percent (frequency).

Missing <2%;

Missing 2–5%

OAB medication only included current medication use at baseline.

HS, high school; GED, General Educational Development; BMI, body mass index; TIA, transient ischemic attack; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; LUTD, lower urinary tract disease; OAB, overactive bladder; PTNS, Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation; SNM, sacral neuromodulation

At baseline, the mean (±SD) overall LUTS Tool severity score was 47.7 (±12.8) and was higher in the UUI cohort compared with UU-only cohort (difference [95% CI] = 9.7 [6.1–13.2], Table 2). UUI participants had more severe frequency (difference [95% CI] = 5.0 [0.1–9.9]), urgency (difference [95% CI] = 18.0 [14.3–21.7]), and incontinence symptoms (difference [95% CI] = 23.5 [18.9–28.1]) than UU-only participants, but they were similar on other LUTS. The PROMIS measures were all within ½ SD (5 points) of the normative population mean of 50, except for PROMIS Physical Function for which the UUI participants had lower physical function than the normative population mean.

Table 2:

Patient-reported measures at baseline

| Total (n=349) | Urinary urgency with urgency incontinence (n=281) | Urinary urgency without urgency incontinence (n=68) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Overall LUTS Tool a, b Score ¥ | 47.7 (12.8) | 49.6 (12.6) | 39.9 (10.5) |

| LUTS Tool Frequency Score γ | 55.8 (18.4) | 56.8 (17.8) | 51.8 (20.1) |

| LUTS Tool Post-micturition Score β | 48.4 (26.0) | 48.9 (26.2) | 46.4 (25.0) |

| LUTS Tool Urgency Score γ | 65.0 (18.0) | 68.5 (17.5) | 50.5 (12.5) |

| LUTS Tool Voiding Difficulty Score γ | 28.3 (21.1) | 28.7 (21.1) | 26.8 (21.3) |

| LUTS Tool Pain Score γ | 16.3 (21.7) | 16.3 (21.5) | 16.2 (22.8) |

| LUTS Tool UI Score λ | 45.4 (19.3) | 50.1 (16.6) | 26.6 (17.6) |

| Quality of life due to urinary symptoms (0=Delighted to 6=Terrible) λ | 4.7 (1.1) | 4.8 (1.1) | 4.3 (1.2) |

| PROMIS c Depression (T score) γ | 50.4 (9.0) | 50.9 (9.1) | 48.2 (8.0) |

| PROMIS Anxiety (T score) γ | 51.4 (9.4) | 51.6 (9.6) | 50.4 (8.5) |

| PROMIS Physical Function (T score) γ | 45.7 (10.4) | 45.0 (10.4) | 48.6 (10.2) |

| PROMIS Sleep Disturbance (T score) γ | 51.9 (4.8) | 52.0 (4.9) | 51.4 (4.7) |

| PROMIS GI Diarrhea (T score) γ | 49.7 (9.6) | 50.0 (9.7) | 48.2 (9.5) |

| PROMIS GI Constipation (T score) λ | 52.2 (8.2) | 52.2 (8.1) | 51.9 (8.4) |

| Perceived Stress Scale λ | 13.7 (7.8) | 13.9 (7.7) | 12.8 (7.9) |

| PROMIS GI Bowel Incontinence (raw scale) λ | 5.6 (2.7) | 5.7 (2.8) | 5.2 (2.7) |

Table values are mean (standard deviation). The LUTS Tool scores range from 0 to 100 and were created by combining responses to related symptom severity questions from the LUTS Tool and calculating the Euclidean length of the relevant questions as a measure of overall symptom severity. Higher score means more severity. PROMIS measures T-scores have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10 by definition and are centered on the US general population. The minimal clinically important differences (MCID) is 3 to 5 points in T-scores across PROMIS measures.

Missing <2%;

Missing 2–5%;

Missing 5–10%;

Missing 17%

LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; UI, urinary incontinence; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; GI, gastrointestinal

LUTS Tool: Coyne K, Barsdorf A, Thompson C, et al. Moving towards a comprehensive assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Neurourology and Urodynamics.31(4):448–454,2012

Helmuth MS, A, Andreev V, Liu G, et al. Use of Euclidean Length to Measure Urinary Incontinence Severity Based on the Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Tool. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 218(3):357–359,2017

PROMIS: Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology.;63(11):1179–1194, 2010

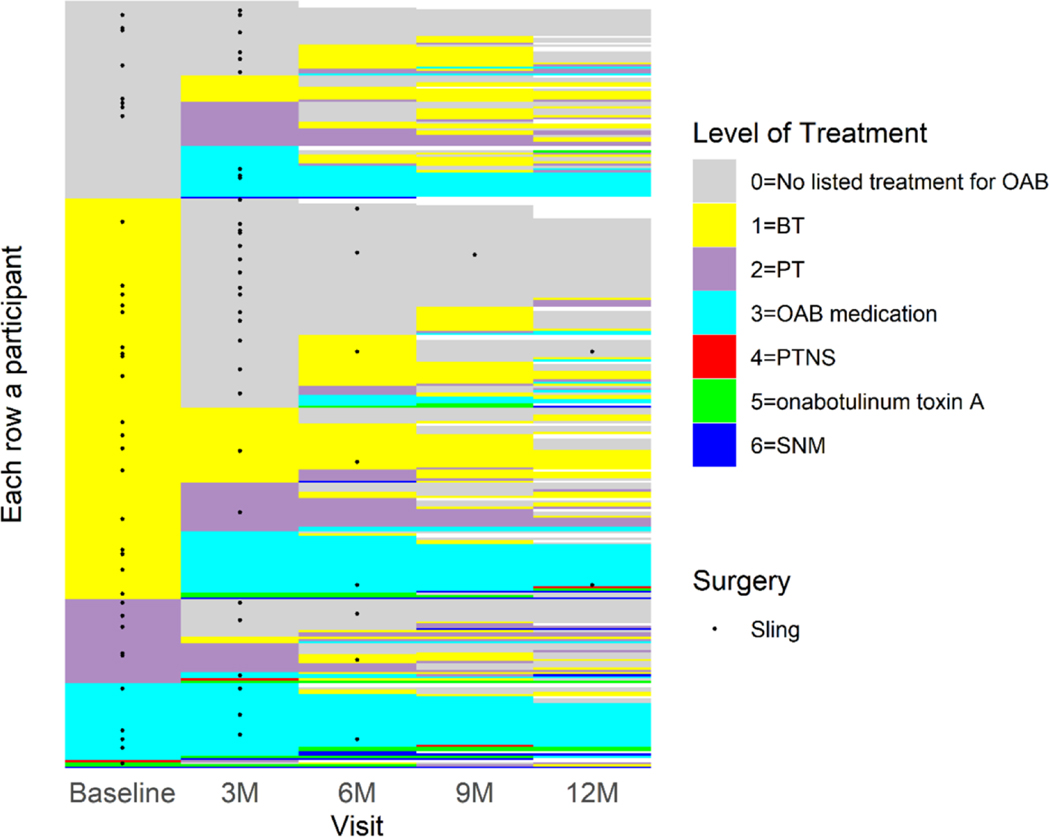

Treatment patterns over time

Figure 1 shows the patterns of the highest level of treatment over time among the participants. Each row of this lasagna plot represents a participant who was followed for 12 months (x-axis). The type of treatment a participant receives during a given 3-month interval is denoted with a color (see legend for “Level of Treatment”). For example, if a participant who is on BT at baseline initiates OAB medication between 3 and 6 months and stays on that treatment for the remainder of the study period, that participant would have a yellow colored row at baseline which would change to aqua at 3 months and remain aqua. If a participant underwent a sling procedure, this was indicated with a black dot. At baseline, 52% of participants reported BT, 11% PT and 10% OAB medication as the highest level of treatment, while 26% (n=90) had not tried or were not currently using any of the treatments of interest before or at the time of their baseline visit. The majority of these 90 participants were treated during study follow-up (highest level of treatment: 26% [n=23] with BT, 28% [n=25] with PT, and 27% [n=24] with OAB medications). Among the 182 (52%) participants on BT at baseline, 25% (n=45) discontinued BT and remained untreated during study follow-up; 32% (n=58) continued BT, and 19% (n=34) escalated to PT and 20% (n=36) to OAB medication during the study follow-up. Among the 38 (11%) participants using PT at baseline, 26% (n=10) discontinued PT and did not receive any other treatment during the study follow-up; 8% (n=3) de-escalated to BT, 47% (n=18) continued PT, and 8% (n=3) escalated to an OAB medication during the study follow-up. Among the 35 (10%) participants using an OAB medication at baseline, 80% (n=28) continued use and 20% (n=7) escalated to third-line treatments. Third-line treatments were the least commonly used mode of treatment with only 12 (3%) participants using intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA, 4 (1%) PTNS, and 11 (3%) SNM prior to baseline or during the study. Supplementary Figure 1 shows the treatment escalation and de-escalation patterns over the follow-up period.

Figure 1:

Lasagna plot of the highest level of treatment by visit.

Slings were placed in 10% (n=36) of participants prior to baseline and in 11% (n=40) during the study follow-up (mostly between baseline and 3 months). A minority (2% [n=6]) had slings placed both prior to and after baseline (Figure 1).

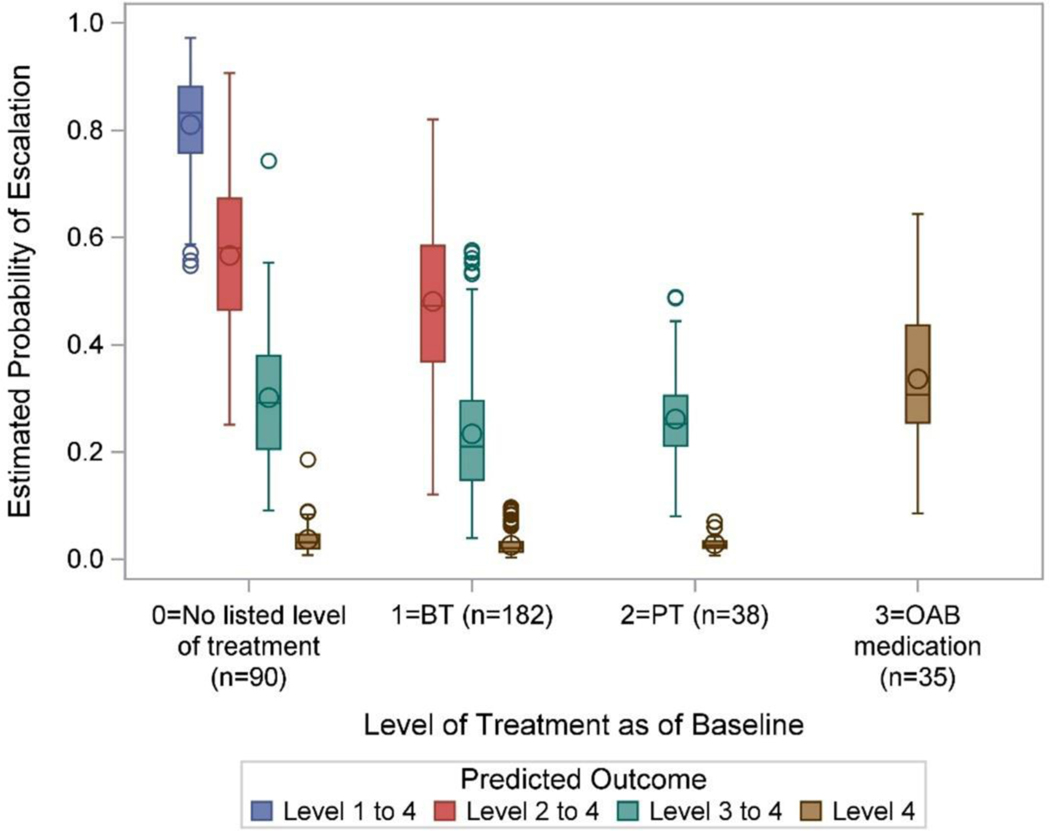

Probability of treatment escalation and de-escalation over 12 months

Based on the ordinal logistic regression model of highest level of treatment (Supplementary Table 2), on average, participants with no OAB treatment at baseline had an .81 probability of escalating to level 1 (BT) or above (1+), .57 probability of escalating to level 2 (PT) or above (2+), .30 probability of escalating to level 3 (OAB medication) or above (3+), and .04 probability of escalating to level 4 (surgeries/procedures) during the study period. Figure 2a represents these probabilities of escalating treatment visually. Participants were grouped based on their baseline treatment (x-axis). The distribution of estimated probabilities that they change treatment to a more invasive treatment is demonstrated by the box plots. For example, for participants who were not on any treatment at baseline (level 0), the estimated average probability that they were escalated to a treatment of level 1 or greater (blue box plot) during the 1-year follow up was 0.81. On average, participants on a level 1 treatment (BT) at baseline had .48 probability of escalating to level 2 or greater, .23 probability of escalating to level 3 or greater, and .03 probability of escalating to level 4. Participants on level 2 (PT) at baseline had .26 probability of escalating to level 3 or greater and .03 probability of escalating to 4. Finally, participants on level 3 (OAB medication) at baseline had an average of .34 probability of escalating to level 4.

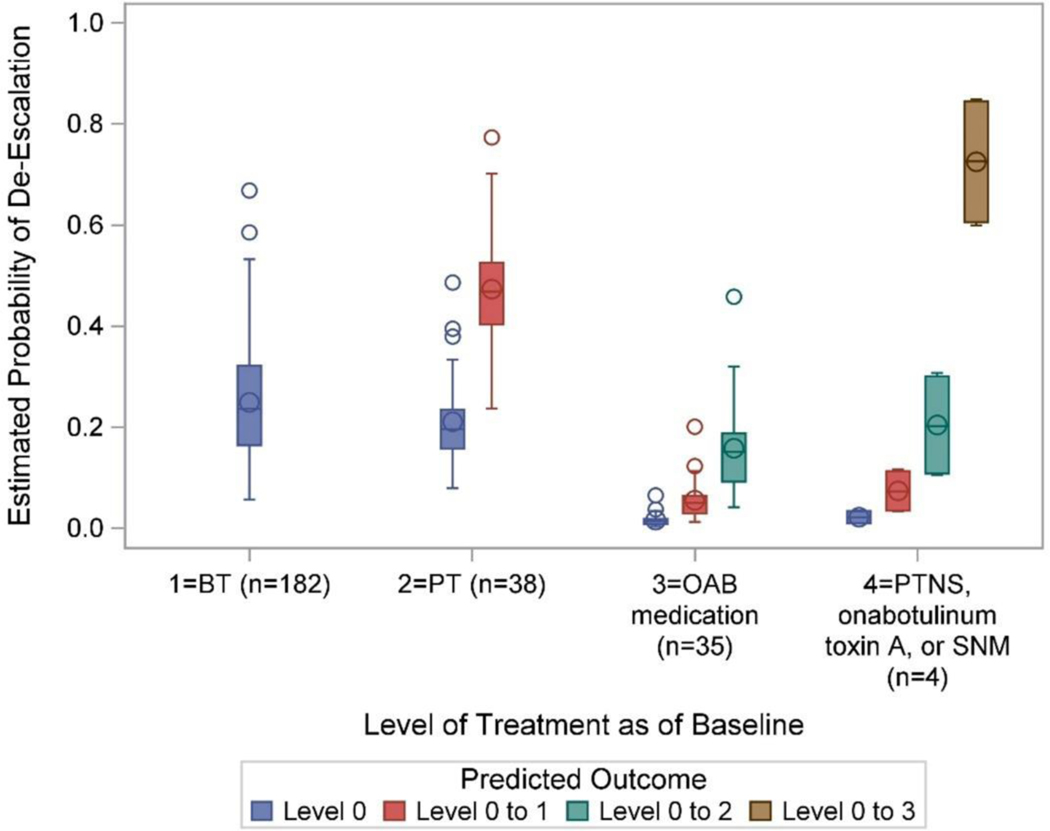

Figure 2:

Estimated probability of (a) escalation and (b) de-escalation by level of treatment as of baseline. Results from proportional odds model. BT, behavioral therapy; PT, pelvic floor physical therapy; OAB, overactive bladder; PTNS, Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation; SNM, sacral neuromodulation.

Considering the probability of de-escalation (Figure 2b), participants on level 1 (BT) at baseline had an average probability of .25 of de-escalating to level 0 (no treatment). Participants on level 2 (PT) at baseline had .47 probability of de-escalating to level 1 or lower and .21 probability of de-escalating to level 0. Participants on level 3 (OAB medication) at baseline on average had .16 probability of de-escalating to level 2 or lower, .06 probability of de-escalating to level 1 or lower, and .02 probability of de-escalating to level 0. Only four participants were on treatment level 4 at baseline.

Comment

Principal findings

This study sought to elucidate patterns of treatment as well as factors associated with treatment escalation and de-escalation in a cohort of women with bothersome UU and UUI presenting to specialty care. Despite reporting significant bother from their OAB symptoms, approximately 40% of participants only received conservative treatment, i.e., BT, or no treatment during the 12-month study period. Participants who were on OAB medications at baseline or were started on OAB medications after their first visit tended to stay on medications throughout the study period. Participants undergoing BT or PT at baseline were more likely to be de-escalated to no treatment than participants on OAB medications at baseline.

Results in the context of what is known

Our study is the first to describe treatment patterns—escalation, de-escalation and continuation—that incorporates all OAB treatment modalities in a cohort of women presenting to specialty care. Kraus et al. (2020) described treatment patterns of patients with OAB over a 24-month period using a large, retrospective database.19 They defined their cohort by identifying patients who filled an OAB medication prescription or underwent a third-line procedure for OAB. Similar to our findings, they found that a small percentage (approximately 3%) of patients in the OAB medication cohort were escalated to a third-line treatment; however, of the patients in the third-line procedure cohort, one third were prescribed an OAB mediation. The study by Kraus et al. is limited by the reliance of medical claims to identify their patient cohort and thus does not capture patients with bothersome OAB who were undergoing more conservative treatment options. Using a prospectively collected cohort of participants, our study demonstrated that a large proportion of patients who report bothersome UU and UUI only receive first line treatments such as BT or no treatment at all, despite receiving care from a tertiary female urology or urogynecology clinic. In this study, we were also able to provide novel information regarding the average probability of treatment escalation or de-escalation depending on baseline characteristics. While these findings cannot fully account for the many reasons why escalation and de-escalation occur, they are able to increase awareness of how often they occur which can be useful information for patient counseling around treatment options.

Few studies have described the escalation to third-line treatments, but several studies have explored factors associated with discontinuation of third-line treatments. We were surprised to find that in our cohort of patients who sought care in tertiary academic medical centers, very few participants were escalated to third-line treatments during the study period; only 7% of participants were treated with any third-line treatments prior to baseline or during the study. In 2020, Kirby et al. performed a retrospective study using insurance claim data, exploring time to third-line treatment for women who were started on an OAB medication and found that the median time to receiving third-line treatment was 38 months from the first OAB medication prescription. 20 In our cohort, 80% of participants who were on OAB medications at baseline continued medication during the study, while the remaining 20% were escalated to third-line treatments. It is possible that if we followed our cohort beyond 12 months that a greater proportion of patients would be escalated to third-line treatments. In 2021, Du et al. published a retrospective cohort study of new OAB patients presenting to a specialty care clinic to determine the impact of an OAB clinical care pathway on the rate of and time to third-line treatments.21 The clinical care pathway increased rates of third-line treatment from 7.7% to 13.4% at 6 months and 11.1% to 16.5% at 12 months while decreasing the time to third-line treatments from 280 days to 160 days. Du et al.’s study highlighted the benefits of clinical care pathways yet underscored the fact that only a fraction of patients are escalated to third-line treatments, a similar finding in our study.

Many factors influence whether a patient continues or discontinues a given treatment. Prior studies have associated medication adherence with patient factors, such as age, weight, gender, symptom severity, cumulative ACB score, and comorbid conditions and treatment factors, such as adverse effects, cost, and efficacy. 4, 22–25 We identified several clinical factors associated with different treatment patterns. By pairing knowledge about treatment patterns with patient clinical response and treatment goals, providers can improve their counseling around OAB treatments. Ultimately, data from this study can be used to create prediction tools that can assist providers individualize treatment plans with the goal to improve OAB symptoms.

Strengths and Limitations:

To the best of our knowledge, our study is one of the first to describe treatment patterns for women with bothersome OAB that incorporate all OAB treatment modalities. This information could be used to develop clinical tools for counseling and refining treatment plans for patients, especially those at high risk for discontinuation of medication or conservative therapy. Other strengths include using data from a one-year multi-center prospective observational study of patients seeking specialty care for LUTS. The generalizability of the study’s findings is limited by the fact that the study cohort is mostly well-educated, English-speaking, and white participants seeking specialty care. Consequently, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Other limitations include participant recall bias, which could impact the reporting of symptom severity and treatments. Also, given the nature of the data available, we were not able to comment on several important factors that would impact treatment patterns. For instance, treatment cost, time constraints, side effects, and treatment response could impact a patient’s ability or willingness to continue treatment, while limitations of insurance coverage, personal or group practice patterns, and medical training could influence a medical provider’s ability or willingness to prescribe a given treatment. Furthermore, we were unable to capture participant satisfaction with treatment or response to treatments, which would greatly impact whether a patient is willing to continue to treatment or escalate therapy. It is possible that certain treatments were effective at treating the patient’s bothersome symptoms, and thus escalation of treatment was not clinically indicated; conversely, those same treatments may not have been effective and thus were discontinued. Lastly, given the length of follow up being restricted to 1-year, we may not have captured treatment escalation that had been planned or captured if longer longitudinal follow up had been obtained.

Clinical and research implications:

The finding that so few patients with bothersome UU and/or UUI are escalated beyond conservative or medication therapy is surprising given the percentage of patients who sought care after having tried these therapies already and reinforces the need for treatment algorithms that are centered on patient satisfaction and improved resolution of clinically bothersome symptoms. We also need to improve our understanding of treatment response as we are still uncertain if more prompt escalation to third line treatments would lead to more impactful resolution of bothersome UU and UUI. Using these data to develop OAB treatment prediction tools would allow providers to individualize treatment plans and identify patients at risk for treatment discontinuation, as well as patients who may not be escalated to potentially beneficial OAB treatments with the goal to improve clinical outcomes for patients suffering from this chronic and often debilitating condition.

Conclusions:

Treatment patterns for UU and UUI are highly variable. Even for patients with significant bother from OAB presenting to specialty clinics, further treatment often only involves conservative or medical therapies. This study highlights the need for improved treatment algorithms to escalate patients with persistent symptoms or to adjust care in those who have been unsuccessfully treated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This is publication number 31 of the Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network (LURN).

This study is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases through cooperative agreements (grants DK097780, DK097772, DK097779, DK099932, DK100011, DK100017, DK099879).

Research reported in this publication was supported at Northwestern University, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The following individuals were instrumental in the planning and conduct of this study at each of the participating institutions:

Duke University, Durham, North Carolina (DK097780): PIs: Cindy Amundsen, MD, J. Eric Jelovsek, MD, MMEd, MSDS; Co-Is: Kathryn Flynn, PhD, Jim Hokanson, PhD, Aaron Lentz, MD, David Page, PhD, Nazema Siddiqui, MD, Kevin Weinfurt, PhD, Lisa Wruck, PhD, Michelle O’Shea, MD, PhD, Todd Harshbarger, PhD; Study Coordinators: Paige Green, Magaly Guerrero

University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA (DK097772): PIs: Catherine S Bradley, MD, MSCE, Karl Kreder, MD, MBA; Co-Is: Bradley A. Erickson, MD, MS, Daniel Fick, MD, Vince Magnotta, PhD, Philip Polgreen, MD, MPH; Study Coordinators: Sarah Heady, Chelsea Poesch, Shelly Melton, Jean Walshire

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL (DK097779): PIs: James W Griffith, PhD, Kimberly Kenton, MD, MS, Brian Helfand, MD, PhD; Co-Is: Carol Bretschneider, MD, David Cella, PhD, Sarah Collins, MD, Julia Geynisman-Tan, MD, Alex Glaser, MD, Christina Lewicky-Gaupp, MD, Margaret Mueller, MD, Devin Boehm, BS; Study Coordinators: Sylwia Clarke, Melissa Marquez, Malgorzata Antoniak, Pooja Talaty, Francesca Moroni, Sophia Kallas. Dr. Helfand and Ms. Talaty are at NorthShore University HealthSystem.

University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI (DK099932): PI: J Quentin Clemens, MD, FACS, MSCI; Co-Is: John DeLancey, MD, Dee Fenner, MD, Rick Harris, MD, Steve Harte, PhD, Anne P. Cameron, MD, Aruna Sarma, PhD, Giulia Lane, MD; Study Coordinators: Linda Drnek, Greg Mowatt, Sarah Richardson, Julia Chilimigras, Diana O’Dell

University of Washington, Seattle Washington (DK100011): PI: Claire Yang, MD; Co-I: Anna Kirby, MD; Study Coordinators: Brenda Vicars, RN, Lauren Daniels

Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis Missouri (DK100017): PI: H. Henry Lai, MD; Co-Is: Gerald L. Andriole, MD, Joshua Shimony, MD, PhD, Fuhai Li, PhD; Study Coordinators: Linda Black, Vivien Gardner, Patricia Hayden, Diana Wolff, Aleksandra Klim, RN, MHS, CCRC

Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, Data Coordinating Center (DK099879): PI: Robert Merion, MD, FACS; Co-Is: Victor Andreev, PhD, DSc, Brenda Gillespie, PhD, Abigail Smith, PhD; Project Manager: Melissa Fava, MPA, PMP; Clinical Monitor: Melissa Sexton, BA, CCRP; Research Analysts: Margaret Helmuth, MA, Jon Wiseman, MS, Jane Liu, MPH, Sarah Mansfield, MS

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Kidney, Urology, and Hematology, Bethesda, MD: Project Scientist: Ziya Kirkali MD; Project Officer: Christopher Mullins PhD; Project Advisor: Julie Barthold, MD.

Shauna Leighton, Medical Editor with Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, provided editorial assistance on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Ethics of Approval Statement:

All research is Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved (IRB #14154–04). All human subjects provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality.

Patient Consent Statement:

All human subjects provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality.

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT02485808

Conflicts of Interest: Authors do not have any relevant disclosures.

Data Availability Statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the NIDDK Central Repository at https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/; please reference the acronym “LURN”.

References

- 1.Reynolds WS, Fowke J, Dmochowski R. The Burden of Overactive Bladder on US Public Health. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2016;11(1):8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown MT, Bussell J, Dutta S, Davis K, Strong S, Mathew S. Medication Adherence: Truth and Consequences. Am J Med Sci. 2016;351(4):387–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeowell G, Smith P, Nazir J, Hakimi Z, Siddiqui E, Fatoye F. Real-world persistence and adherence to oral antimuscarinics and mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder (OAB): a systematic literature review. BMJ Open. 2018;8(11):e021889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, et al. Patient-reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int. 2010;105(9):1276–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andy UU, Arya LA, Smith AL, et al. Is self-reported adherence associated with clinical outcomes in women treated with anticholinergic medication for overactive bladder?. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016;35(6):738–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato D, Uno S, Van Schyndle J, Fan A, Kimura T. Persistence and adherence to overactive bladder medications in Japan: A large nationwide real-world analysis. Int J Urol. 2017;24(10):757–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Illiano E, Finazzi Agrò E, Natale F, Balsamo R, Costantini E. Italian real-life clinical setting: the persistence and adherence with mirabegron in women with overactive bladder. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52(6):1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalder M, Pantazis K, Dinas K, Albert US, Heilmaier C, Kostev K. Discontinuation of treatment using anticholinergic medications in patients with urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Athanasopoulos A, Giannitsas K. An overview of the clinical use of antimuscarinics in the treatment of overactive bladder. Adv Urol. 2011;2011:820816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang CC, Weinfurt KP, Merion RM, Kirkali Z; LURN Study Group. Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction Research Network. J Urol. 2016;196(1):146–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coyne KS, Barsdorf AI, Thompson C, et al. Moving towards a comprehensive assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(4):448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp Z, et al. Assessing patients’ descriptions of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and perspectives on treatment outcomes: results of qualitative research. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(9):1260–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cameron AP, Lewicky-Gaupp C, Smith AR, et al. Baseline Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Patients Enrolled in LURN: A Prospective, Observational Cohort Study. J Urol. 2018;199(4):1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lightner DJ, Gomelsky A, Souter L, Vasavada SP. Diagnosis and Treatment of Overactive Bladder (Non-Neurogenic) in Adults: AUA/SUFU Guideline Amendment 2019. J Urol. 2019;202(3):558–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carnahan RM, Lund BC, Perry PJ, Pollock BG, Culp KR. The Anticholinergic Drug Scale as a measure of drug-related anticholinergic burden: associations with serum anticholinergic activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(12):1481–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barry MJ, Williford WO, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association symptom index and the benign prostatic hyperplasia impact index is perceptible to patients?. J Urol. 1995;154(5):1770–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraus SR, Shiozawa A, Szabo SM, Qian C, Rogula B, Hairston J. Treatment patterns and costs among patients with OAB treated with combination oral therapy, sacral nerve stimulation, percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation, or onabotulinumtoxinA in the United States. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39(8):2206–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirby AC, Park S, Cook SB, Odem-Davis K, Gore JL, Wolff EM. Practice Patterns for Women With Overactive Bladder Syndrome: Time Between Medications and Third-Line Treatments. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26(7):431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du C, Berg WT, Siegal AR, et al. A retrospective longitudinal evaluation of new overactive bladder patients in an FPMRS urologist practice: Are patients following up and utilizing third-line therapies?. Neurourol Urodyn. 2021;40(1):391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lua LL, Pathak P, Dandolu V. Comparing anticholinergic persistence and adherence profiles in overactive bladder patients based on gender, obesity, and major anticholinergic agents. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(8):2123–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soda T, Tashiro Y, Koike S, Ikeuchi R, Okada T. Overactive bladder medication: Persistence, drug switching, and reinitiation. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39(8):2527–2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ivchenko A, Bödeker RH, Neumeister C, Wiedemann A. Anticholinergic burden and comorbidities in patients attending treatment with trospium chloride for overactive bladder in a real-life setting: results of a prospective non-interventional study. BMC Urol. 2018;18(1):80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim TH, Lee KS. Persistence and compliance with medication management in the treatment of overactive bladder. Investig Clin Urol. 2016;57(2):84–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the NIDDK Central Repository at https://repository.niddk.nih.gov/; please reference the acronym “LURN”.