Due to the newness of the virus, side effects of vaccines specific to SARS-CoV-2 are not yet known. CoronaVac, a purified inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine developed by Sinovac Biotech (Beijing, China), has been shown to induce SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralising antibodies in mice, rats, non-human primates and in macaques.1 CoronaVac was shown to be well tolerated and did not cause dose-related safety concerns in phase 1 and 2 clinical studies involving healthy individuals aged 18–59 years2 and those aged 60 years and older.3 The most common symptom was injection site pain, and hypersensitivity reactions were the least reported side effects.2 We do not know the phase 3 efficacy and side effect results of CoronaVac, although vaccination has started. Turkey has decided on the CoronaVac within the vaccine market and is currently continuing the vaccination of elderly people following health workers. Here we share up-to-date data on an elderly person who developed post-vaccination side effects in the form of a petechial rash.

An 82-year-old woman presented with weakness, burning in the legs and a rash. A diffuse petechial rash was observed on both lower extremities during dermatological examination (figure 1A, B). It was learned that she had been vaccinated with CoronaVac 1 day before the petechial rash appeared, and that there were no symptoms other than weakness and burning in the legs approximately 10 hours after vaccination. A complete blood test, routine biochemical parameters, C-reactive protein, D-dimer levels, platelet count and coagulation parameters were normal. Urinalysis showed no signs of proteinuria or haematuria. Serological tests for viral hepatitis and HIV were negative. Antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and cardiolipin antibodies were within normal ranges. Complement levels and serum proteinograms were normal. PCR and rapid IgM, IgG antibodies for SARS-COV-2 testing were negative. The patient had been using hydroxychloroquine 400 mg regularly for the last 3 years for seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, and olmesartan for 2 years for hypertension. She was taking no drug other than these and the vaccine. Prednisolone 5 mg, which she had been using for 6 months for seronegative arthritis, was discontinued 3 weeks before the vaccine in order not to prevent the effect of the vaccine. She was diagnosed with petechial rash as a vaccine-induced hypersensitivity reaction based on the clinical picture, history and laboratory analysis. According to the objective causality assessment by the Naranjo probability scale,4 the causal association between CoronaVac and the petechial rash was probable (Naranjo score=6).

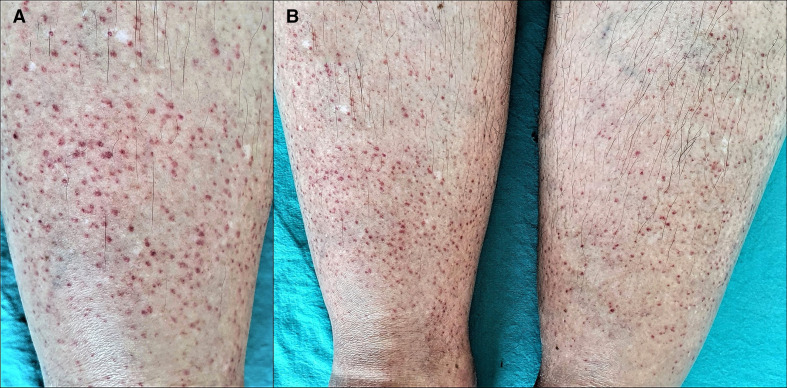

Figure 1.

(A) Close view of the petechial rash on the right leg. (B) Bilaterally located petechial rash in the lower extremities.

The lesions regressed almost completely after 2 days and completely disappeared after 1 week. In the meantime, when safety in vaccine effect was reported if prednisolone was <20 mg in the newly published guideline by the American College of Rheumatology,5 the discontinued prednisolone was restarted 1 week after complete remission of the rash and this time, while she was using it for 2 weeks, the corresponding second dose of vaccine was administered. Probably as a result of this, no skin reaction was observed after the second dose. Skin symptoms such as petechial exanthems6 and cutaneous leucocytoclastic vasculitis7 in COVID-19 are well defined and common. Here, the presence of viral proteins in the endothelial cells of the dermal vessels is thought to be responsible for the pathogenesis of petechiae purpura.6 As for vasculitis, it is thought that the accumulation of immune complexes that activate the complement cascade cause small vessel wall damage.7

Vaccine-associated hypersensitivity reactions are not infrequent; however, IgE or complement-mediated anaphylactic or serious delayed-onset T cell-mediated systemic reactions are extremely rare. Hypersensitivity may result either from the active vaccine component or one of the other components. Post vaccination acute-onset hypersensitivity reactions involve localised adverse events and systemic reactions varying from urticaria/angioedema to anaphylaxis, rarely. Delayed-type reactions happen generally within hours or days following exposure, although symptom onset can be seen after 2–3 weeks. The most frequent signs of delayed-type reactions are cutaneous eruptions such as maculopapular petechial rash. Delayed reactions are usually self-limiting conditions that do not contraindicate the administration of future booster doses of the same vaccine.8 Therefore, we decided to administer the second dose to our patient 28 days after the first dose.

The occurrence of a CoronaVac-related mucocutaneous eruption has been reported as 4% in phase 1/2 clinical studies involving healthy adults aged 60 years and older. Because the phase 3 results on CoronaVac have not yet been published, we are not sufficiently aware of CoronaVac-related cutaneous or systemic side effects.3 Hence, postmarketing safety surveillance is needed to identify rare serious adverse events, and case reports are crucial in this. As far as we are aware, this is the first cutaneous side effect following CoronaVac vaccination reported before the phase 3 results have been published.

ejhpharm-2021-002794supp001.pdf (169.1KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Contributors: FC is the primary physician of the patient discussed in this paper and supervised the process, created the idea, designed the process, reviewed the article, took part in patient care, data collection, literature review, writing and preparation of the manuscript. İK took part in the diagnosis and patient evaluation and reviewed the article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Gao Q, Bao L, Mao H, et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020;369:77–81. 10.1126/science.abc1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18–59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2021;21:181–92. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30843-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wu Z, Hu Y, Xu M, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) in healthy adults aged 60 years and older: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2021;395. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30987-7. [Epub ahead of print: 03 Feb 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1981;30:239245. 10.1038/clpt.1981.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. ACR COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Task Force . COVID-19 vaccine clinical guidance summary for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, 2021. Available: https://www.rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/COVID-19-Vaccine-Clinical-Guidance-Rheumatic-Diseases-Summary.pdf

- 6. Diaz-Guimaraens B, Dominguez-Santas M, Suarez-Valle A, et al. Petechial skin rash associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156:820–2. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mayor‐Ibarguren A, Feito‐Rodriguez M, Quintana Castanedo L, et al. Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis secondary to COVID‐19 infection: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020;34:e541–2. 10.1111/jdv.16670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McNeil MM, DeStefano F. Vaccine-associated hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;141:463–72. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ejhpharm-2021-002794supp001.pdf (169.1KB, pdf)