Abstract

In this study, biochar derived from bamboo pretreated with aluminum salt was synthesized for the removal of two sulfonamide antibiotics, sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and sulfapyridine (SPY), from wastewater. Batch sorption experiments showed that Al-modified bamboo biochar (Al-BB-600) removed both sulfonamides effectively with the maximum sorption capacity of 1200–2200 mg/kg. The sorption mechanism was mainly controlled by hydrophobic, π-π, and electrostatic interactions. Fixed bed column experiments with Al-modified biochar packed in different dosages (250, 500 and 1000 mg) and flow rates (1, 2 and 4 mL/min) showed the dosage of 1000 mg and flow rate of 1 mL/min performed the best for the removal of both SMX and SPY from wastewater. Among the breakthrough (BT) models used to evaluate the fixed bed filtration performance of Al-BB-600, the Yan model best described the BT behavior of the two sulfonamides, suggesting that the adsorption process involved multiple rate-liming factors such as mass transfer at the solid surface and diffusion Additionally, the Bed Depth Service Time (BDST) model results indicated that Al-BB-600 can be efficiently used in fixed bed column for the removal of both SMX and SPY in scaled-up continuous wastewater flow operations. Therefore, Al-modified biochar can be considered a reliable sorbent in real-world application for the removal of SMX and SPY from wastewater.

Keywords: Fixed bed filters, Adsorption, Biochar, Wastewater treatment, Sulfonamide antibiotics

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and sulfapyridine (SPY) are typical sulfonamide antibiotics that are widely added to livestock feed for bacterial disease treatment (Yang et al., 2020) because of their efficacy and low cost (Connor, 1998; Gao et al., 2012; Tian et al., 2013; Paumelle et al., 2021). Unfortunately, because of their low rate of metabolization, they have been released to the environment, mainly via wastewater and animal excretion (Galán et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2020; Paumelle et al., 2021). Making matters worse, due to their high mobility and resistance to biodegradation, they are further dispersed in the environment through leaching to soil surface and groundwater, and even drinking water (Hu et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2020). The residues of these antibiotics are carcinogenic and allergenic, not only display acute or chronic toxicity (Choquet-Kastylevsky et al., 2002; Shao et al., 2005; Guo et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020), but also generate a selection pressure on microbes in the environment to develop antimicrobial resistance (Hu et al., 2018; Paumelle et al., 2021). Therefore, the innovative wastewater treatment technique for effective removal of these sulfonamide antibiotics is an urgent need.

Wastewater treatment methods for antibiotics removal include membrane bioreactors (Galán et al., 2012), constructed wetlands (Liu et al., 2019), adsorption (Cooney, 1999), sludge activation (Villar-Navarro et al., 2018), advanced oxidation (Wang and Wang, 2016), ozonation (Khan et al., 2020), microalgae-based technology (Leng et al., 2020), and reverse osmosis (Khan et al., 2020). Among them, adsorption is relatively inexpensive, convenient, and reliable. Conventional sorbents such as activated carbon (Bansal and Goyal, 2005), zeolite (Motsi et al., 2009) and clay minerals (Gaines Jr and Thomas, 1953), are either too expensive or have limited availability and removal efficiencies for antibiotics. Hence, efficient and cost-effective sorbents are essential for successful application of adsorption technique to remove antibiotics from wastewater.

Biochar, a carbonaceous material made by the pyrolysis of organic feedstocks under anaerobic conditions, has been regarded as an effective sorbent to remove inorganic and organic emerging contaminants in the environment due to its high specific surface area, abundant surface functional groups, and diverse sorption sites (Ahmad et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2021). Nevertheless, many studies have shown a poor performance of pristine biochar to remove aqueous sulfonamide antibiotics due to the low pore volume of biochar in relation of the size of antibiotic compounds (Huang et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2020; Krasucka et al., 2021). It is speculated that when applied to wastewater (pH ≈ 7.6), the electrostatic repulsion between sulfonamides (e.g., SMX, pKa of 1.8 and 5.6, Table S1) and pristine biochar, both negatively charged, may hinder the sorption performance. Thus, a number of modification methods involving metal oxide/oxyhydroxide impregnation of biochar have been developed recently to improve the sorption efficiency of anionic contaminants (Zhang and Gao, 2013; Zhou et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021). Upon modification, the biochar is enriched in active sorption sites with positive charge (Yao et al., 2011), which may induce electrostatic attraction to sulfonamide antibiotics in wastewater (pH ≈ 7.6). Unlike iron oxide nanocomposite, which may be reduced to its ferrous state in solution upon impregnation (Yang et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2020), boehmite remains stable in aqueous environment. With the point of zero charge (PZC) around 7.7-9.4 (Kosmulski, 2001; Kasprzyk-Hordern, 2004), boehmite has been proven safe and efficient as a sorbent (Zhang and Gao, 2013). Therefore, we modified biochar with aluminum oxyhydroxide (boehmite) in this study.

To date, most applications of metal-modified biochar to antibiotic removal have been focused on batch sorption (Kong et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Yi et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018; Heo et al., 2019; Xiang et al., 2020; Bai et al., 2021). Batch experiments, while serving as an essential approach to examine sorption characteristics, are limited in reflecting the in situ dynamic sorption performance of sorbents. In other words, the actual conditions in which sorbents are likely to be used in adsorption techniques are note realistically simulated by batch sorption. In contrast, fixed bed filtration has the advantages of generating premium effluent quality, efficient sorbent use and regeneration, and facile operational scale-up (Senthilkumar et al., 2006). Fixed bed filtration reactors have already exhibited reliable antibiotic removal ability in continuous flow water treatment and purification systems (Darweesh and Ahmed, 2017; de Franco et al., 2017; Peng et al., 2018; Jang and Kan, 2019). For example, Jang et al. (2019) reported the practical application of NaOH-activated biochar derived from agricultural waste to remove tetracycline from water in fixed bed column. Fixed bed filtration with NaOH-modified biochar was also applied to eliminate the wastewater-sourced ofloxacin and tetracycline (Tang et al., 2022). To the content of our knowledge, no former studies have examined the fixed bed column performance of Al-modified biochar for the removal of sulfonamide antibiotics from wastewater.

Therefore, in this study, the overarching goal is to examine the performance of Al-modified biochar on sulfonamide antibiotics removal from wastewater. We used bamboo pretreated with aluminum chloride hexahydrate (AlCl3·6H2O) solution as feedstock for biochar production and wastewater was spiked with sulfonamide antibiotics. Specifically, both SMX and SPY sorption kinetics and isotherms of Al-modified biochar in wastewater were conducted. The dynamic breakthrough (BT) behaviors of SMX and SPY in fixed bed systems packed with Al-modified biochar in wastewater were also determined under different experimental conditions and examined through different BT models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Bamboo is a common feedstock for biochar preparation and has been applied to remove antibiotics in aqueous phases (Yao et al., 2012; Inyang et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2020). Thus, it was selected for use in this study and was obtained in Gainesville, FL. A mill machine (Thomas-Wiley, model 4) was used to grind air-dried bamboo into 0.5 to 2 mm particles. Aluminum chloride hexahydrate (AlCl3·6H2O) was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH). Both SMX and SPY were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and their physiochemical properties can be found in Table S1. 100 mg/L of SMX/SPY stock solution was made with DI water (18.2 MΩ, pH ≈ 5.6) and stored in the dark chamber (4 °C). The degradation of SMX/SPY was ignored in this study.

Eight-gallon wastewater (secondary treated) were sampled 7 times over a period of 20 days from a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) located at the University of Florida, Gainesville, FL (USA). To remove suspended solids and other impurities, wastewater samples were pumped through 0.45 μm polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane filters (Millipore Durapore™) and stored in the dark chamber (4 °C ) with plastic film sealing. The physiochemical property of the wastewater collected from the same location was reported previously (Zheng et al., 2019) (Table S2, SI). To explore a full range of sulfonamide antibiotic sorption ability, the filtered wastewater samples (pH ≈ 7.6) were spiked with sulfonamide antibiotics (100 mg/L) to realize a final concentration of 10 mg/L for both batch and fixed bed column studies, which is higher than typical naturally occurring concentrations.

2.2. Sample preparation & characterization

Al-modified biochar was prepared based on a previous study (Zhang and Gao, 2013). Briefly, 20 g of milled bamboo was magnetically stirred with 19.32 g of AlCl3·6H2O in 100 mL of DI water overnight (25 ± 0.5 °C). The mixture was then oven-dried at 80 °C for 36 h and then pyrolyzed under a nitrogen environment at 600 °C for 1.5 h (Sun et al., 2014b) in a tubular furnace (Olympic 1823HE). The obtained sample was sieved (0.5 - 1 mm of particle size), rinsed with DI water 3 times, dried at 80 °C for 24 h, and sealed in an air-tight container prior to use. The final product was labeled Al-BB-600, denoting the feedstock and temperature of biochar. Pristine biochar without AlCl3 solution pretreatment was also produced at 600 °C (BB-600) for comparison.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted to characterize the sorbent crystalline structure at a scan rate of 0.03° s−1 (2θ range of 0-70°) using a D2 PHASER (Bruker, USA) X-ray diffractometer. Surface morphologies and elemental compositions were determined by scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS, Hitachi SN3400, Japan). The biochar surface functional groups were analyzed by the Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (Bruker Tensor 27).

2.3. Batch sorption study

Batch sorption kinetic experiments were conducted by mixing 100 mg of biochar with 10 mg/L of spiked wastewater containing SMX or SPY in centrifuge tubes (50 mL) and placed on an orbit shaker (250 rpm) at room temperature with an equilibrium period of 24 h. At different time intervals (0.08 to 24 h), duplicate 10 mL samples were sacrificially withdrawn by syringe, and immediately filtered through 0.22 μm nylon membrane filters (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then SMX or SPY concentrations in the extracted samples were determined at 260 nm wavelength using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer (EVO-60). The sulfonamide antibiotics sorption capacity (Qe) was calculated based on mass balance (Support Information S1). Batch sorption isotherms were determined using similar experimental methods, but different dosages of pristine and Al-modified biochar (10-670 mg) in wastewater spiked with sulfonamides (10 mg/L).

Both sorption kinetics and isotherms were conducted in duplicate and results are exhibited as mean value. Similar treatments were conducted simultaneously without adding sorbents and were used as controls. Further trials were performed if there was a difference larger than 5% in the results.

2.4. Fixed bed column sorption study

The schematic diagram of fixed bed column system is shown in Fig. 1. The experiment was conducted under different dosages (0, 250, 500 and 1000 mg) of Al modified biochar or flow rates (1, 2 and 4 mL/min) of wastewater spiked with SMX or SPY (10 mg/L). Acrylic columns (5.1 cm in height and 1.6 cm in inner diameter) were wet-packed with acid-washed quartz sand (0.425-0.6 mm in size) above and below the biochar layer to stabilize the sorbent and minimize entrapped air. The inlet and outlet of column were covered with 50 μm stainless-steel mesh membranes to equalize flow distribution over the cross-sectional area (2.01 cm2) in the column. After column packing, DI water was pumped upward (peristaltic pump, Masterflex L/S) through the column (> 10 h) to remove bubbles and other impurities. Subsequently, DI water was replaced by wastewater spiked with SMX or SPY and the column effluent was collected at preset time intervals using a fraction collector (IS-95 Interval Sampler, Spectrum Chromatography). The aqueous concentrations of SMX or SPY in the effluent were then measured by the UV-Vis spectrophotometry as described above.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of fixed bed column sorption system (A: wastewater spiked with sulfonamides solution (red); B: peristaltic pump; C: acrylic column packed with quartz sand (top & bottom) and biochar (center); D: fraction collector).

The column experiment was conducted in duplicate. Further trials were performed if there was a difference larger than 5% between the duplicate results.

2.5. Sorption Models

For the batch study, three most commonly used sorption kinetic (pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and Elovich) models and two most commonly used isotherm (Langmuir and Freundlich) models were tested, and details can be found in the Support Information (S2-S3). These models are widely applied in simulated the adsorption behaviors of organics on carbonaceous materials (Jeppu and Clement, 2012). For the fixed bed column study, the dynamic sorption performance of Al-BB-600 for the removal of SMX and SPY from wastewater, were simulated with 6 models (Bed Depth Service Time (BDST), Adams-Bohart (A-B), Thomas, Clark, Yoon-Nelson (Y-N), and Yan). Many studies have covered the background of the Thomas, A-B, Y-N, and Clark models (e.g., (Zhang et al., 2011; Nazari et al., 2016; Chu, 2020)). Details of these models can also be found in the Support Information (S4).

Less common is the Yan model (modified dose-response model) which has been developed to describe BT curves in packed columns (Yan et al., 2001). It assumes multiple rate-limiting steps in the sorption process such as mass transfer at the solid surface and diffusion (de Franco et al., 2017). The Yan model equation can be written as follows:

| (1) |

where C0 (mg/L)is the original antibiotic concentrations in the influent, Ct (mg/L) is the antibiotic concentration in the outflow at t (min), a is the Yan model constant, q0 (mg/kg) is the amount of antibiotics adsorbed onto the sorbent at equilibrium, x (g) is the dosage mass of sorbent, and v (mL/min) is the flow rate. The value of q0 at a given Ct can be predicted from a plot of against time t, using the non-linear regression.

The BDST model has been widely used for fixed bed column design and operation for wastewater treatment to predict how long the sorbent bed may last before replacement (Cooney, 1999). It is a simplified version of Adams-Bohart model and was further developed and modified by Hutchins (Hutchins, 1973). The linear equation of the BDST model is defined as:

| (2) |

where N0 is biochar adsorption capacity (mg/L), k is the adsorption rate constant (L/mg/min), C0 is the influent sorptive concentration (mg/L), F is the linear flow velocity (cm/min), h is the sorbent layer bed depth (cm), t (min) is the service time, and Ct (mg/L) the outflow concentration at time t (min). N0 and k can be calculated based on the slope and intercept of a linear plot of the equation. Both determination coefficient (R2) and root mean square error (RMSE) were calculated to determine the goodness of breakthrough model fit to the experimental data. Details can be found in the Support Information (S5 & S6).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Properties of bamboo biochar

The XRD spectra of Al-BB-600 (Fig. S1) with peaks at 2θ = 13.2°, 38.4°, 48.6°, and 64.8° corresponding to the index planes (0 2 0), (0 3 1), (2 0 0), and (1 5 1), respectively (Zhang and Gao, 2013), shows that boehmite (AlOOH) was the major crystalline phase present in Al-modified biochar. The EDS analysis (Fig. S2) shows that Al-BB-600 had aluminum and oxygen on its surface, which corresponds to aluminum oxyhydroxide/oxide. The above results are consistent with previous findings that colloidal and nanosized metal oxyhydroxide/oxide can be stabilized successfully on biochar surface, resulting in increased specific surface area compared to pristine biochar (Wan et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2019). The FTIR spectra (Fig. 2) further support the existence of aluminum oxyhydroxides in Al-BB-600 with peaks at 719 and 569 cm−1 indicating Al-OH and Al-O bonds, respectively (Li et al., 2016; Taherymoosavi et al., 2017). Besides the presence of aromatic C=O/C=C groups (1560-1618 cm−1) in both BB-600 (pristine biochar) and Al-BB-600, new oxygen-containing functional groups in Al-BB-600 were detected such as -OH (3433 cm−1) and -CO (1077 cm−1) (Chen et al., 2008).

Figure 2.

FITR spectra of pristine biochar (BB-600) and Al-modified biochar (Al-BB-600).

3.2. Sulfonamide batch sorption behavior

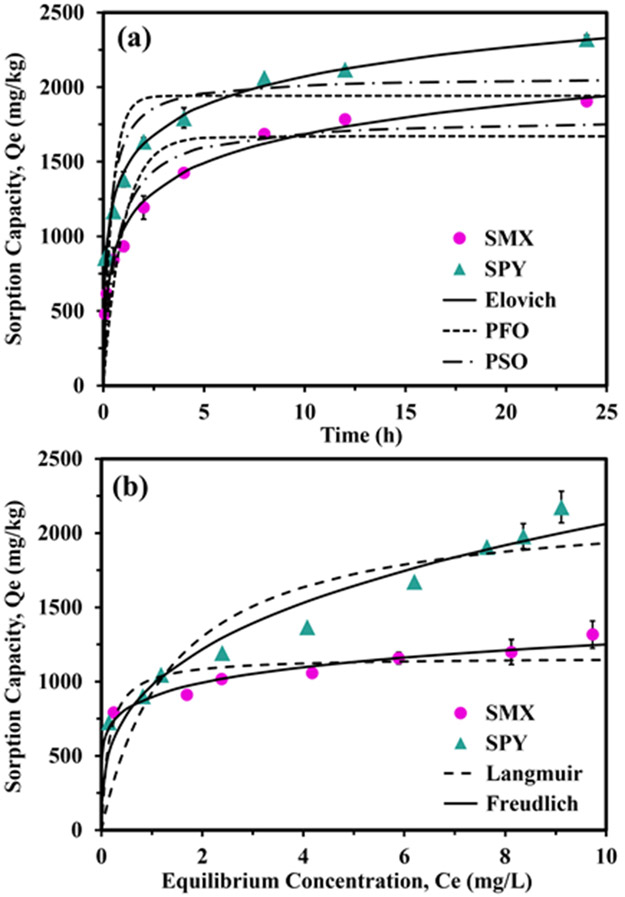

Fig. 3a shows the sorption kinetics of Al-BB-600 in wastewater. Both SMX and SPY exhibited a rapid sorption within the first 4 h, followed by a slow adsorption until reaching equilibrium after 12 h. The dual (fast and slow) sorption stages suggest the involvement of multiple sorption mechanisms (Zhao et al., 2018). This is confirmed by the intraparticle diffusion plot (Fig. S3), which showed a two-stage linear relationship that did not pass through the origin. The first rapid sorption stage may indicate a physical surface sorption mechanism limited by boundary layer diffusion (Geng et al., 2021). Following the decrease in available active sites on biochar, a slower sorption rate may indicate specific (chemo-) and irreversible adsorption which may be controlled by intraparticle diffusion (de Franco et al., 2017).

Figure 3.

SMX and SPY sorption (a) kinetics (PFO: pseudo-first-order; PSO: pseudo-second-order), and (b) isotherms onto Al-BB-600 in wastewater. Data (symbols) were simulated with models (lines).

Pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and Elovich models were applied to further evaluate the sorption kinetics performance and mechanism onto Al-BB-600 in wastewater. The Elovich was the most fitting model (R2 = 0.99, Table S3) for both SMX and SPY, further suggesting that the sorption of sulfonamides was governed by several mechanisms on the heterogeneous surface of Al modified biochar (Jang et al., 2018). For both SMX and SPY, α was greater than β in Elovich model, indicating a fast sorption process involving multiple active sites on biochar surface in the early stage (Geng et al., 2021).

Two isotherm models were used to evaluate the sorption capacity of Al-BB-600. As shown in Fig. 3b and Table S3, the Freundlich model described the isotherm data better for both antibiotics (R2 = 0.93 for SMX and 0.94 for SPY) than the Langmuir, suggesting heterogeneous sorption mechanisms or sites (Huang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020b). The maximum sorption capacity (Qmax) of SMX and SPY were 1200 and 2200 mg/kg in wastewater, respectively (Table S3). Pristine biochar showed negligible sorption of SMX and SPY in wastewater (Fig. S4), whereas Al-BB-600 effectively adsorbed both SMX and SPY even at low equilibrium concentrations (Fig. 3b). This may be explained by the enhancement of active sorption sites and oxygen-containing surface functional groups (Fig. 2) upon Al-modification of biochar, the latter might interact with polar potions of sulfonamide antibiotics (e.g., -SO2NH- and -NH2) through hydrogen bonding (Wan et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2019; Geng et al., 2021). Overall, the batch sorption experiments demonstrated the promising sorption ability of Al-BB-600 for real-world application to remove sulfonamide antibiotics.

3.3. Adsorption mechanism

It is hypothesized that the hydrogen bond interaction of SMX may be stronger than SPY since the pKa2 of SMX (5.6) is closer to the pKa of carboxyl groups on biochar’s surface (~ 5) compared to that of SPY (8.4, Table S1) (Xie et al., 2014). Upon impregnation, the increase in active sorption sites could increase the positive charge on the surface of Al-BB-600, thus enhancing electrostatic interaction with the anionic species of SMX (Yao et al., 2011). However, as shown in Fig. 3b, the Qmax of SMX (1200 mg/kg) was lower than that of SPY (2200 mg/kg) in wastewater, which is counter-logical to the greater expected SMX hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interaction. Therefore, other factors may exist related the complex chemistry of wastewater, either inhibiting the SMX sorption or facilitating the SPY sorption. The collected wastewater sample used in this study, with its high total organic carbon content (TOC, 4.1 - 9.4 mg/L, Table S2), likely contained abundant anion species such as organic acids, which would compete with the anionic species of SMX (pKa2=5.6) for active sorption sites on biochar, thus reducing the SMX removal by Al-BB-600 in wastewater (Lian et al., 2015). In contrast, the predominantly neutral speciation of SPY (pKa2=8.4) would avoid this competition for sorption sites. Further, the pH of wastewater was around 7.6, which is close to the PZC of boehmite (Yang et al., 2007; Kosmulski, 2018). Therefore, the electrostatic interaction between SMX and biochar in wastewater might not be very strong. Additionally, the neutral form of SPY was more hydrophobic at pH around 7.6 and would be a stronger π-electron acceptor compared to the negatively charged SMX. Therefore, hydrophobic interaction and π-π electron donor-acceptor (EDA) interaction could be stronger for SPY (Yao et al., 2018), leading to its greater sorption capacity onto Al-BB-600 in wastewater. As a result, the adsorption mechanism of sulfonamides on Al-BB-600 was mainly controlled by hydrophobic, π-π, and electrostatic interactions.

3.4. Fixed bed column sulfonamide adsorption

3.4.1. Impact of dosage

Different amount of Al-BB-600 (0.25, 0.5 and 1 g) were packed in fixed bed columns to remove SMX and SPY (C0=10 mg/L) from wastewater (v = 1 mL/min). While the control (i.e., no biochar) showed near instantaneous BT, Al-BB-600 showed increasing retardation of both SMX and SPY with increasing sorbent dosages (Fig. 4a and 4b). Specifically, the slope of the BT curve decreased with the increase of dosage (bed depth), thus the BT time (C/C0 = 0.03) increased from 1 to 28 min and 5 to 42 min for SMX and SPY, respectively. This is partially attributed to the extension of the mass transfer zone, creating more contact time of SMX and SPY with biochar in each column (Song et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2018). As with the batch system, the sorption performance of SPY in the fixed bed column (i.e. BT delay) was better than that of SMX.

Figure 4.

BT performance of (a) SMX, and (b) SPY in fixed bed columns packed with Al-BB-600 of different dosages (v = 1 mL/min and C0 = 10 mg/L) in wastewater. Data (symbols) were simulated with models (lines). The dashed line is the simulations of Thomas, Adams-Bohart (A-B) and Yoon-Nelson (Y-N) models (same results).

Thomas, A-B, Y-N, Clark, and Yan models were applied to evaluate the dynamic fixed bed performance of Al-BB-600 under all experimental conditions (Table 1). The fitting results of the Thomas, A-B, and Y-N models were almost the same, as shown in several previous studies (Yan et al., 2018; Chu, 2020), and thus are shown as a single curve (Thomas/A-B/Y-N) in Fig. 4. The Thomas/A-B/Y-N model simulated the experimental data slightly better than the Clark model; however, they failed to match the full experimental BT data, especially with respect to the beginning and end (Fig. 4). Unlike them, the Yan model avoided these disadvantages and achieved the best fit of experimental data among all models with the highest R2 (0.97-0.99 for SMX and 0.98-0.99 for SPY) and the lowest RMSE (~0.05 for SMX and 0.03-0.04 for SPY), which is consistent with former investigations (Calero et al., 2009; Song et al., 2011; de Franco et al., 2017). With the increase in biochar dosage, the dynamic adsorption capacity q0 (mg/kg) predicted by the Yan model increased gradually, for both SMX and SPY except for one data point (SPY onto 1 g of Al-BB-600). This may be ascribed to the increase in contact time as mentioned above. Additionally, increasing the biochar dosage would provide more active binding sites between sulfonamides and biochar in the column (Zhou et al., 2016). The predicted Yan model q0 for both SMX and SPY were slightly lower than their respective Langmuir maximum sorption capacities (Qmax), which is expected because of the distinction between batch and column systems (Zheng et al., 2019). This result also confirms that the fixed bed sorption capacity of Al-BB-600 to SPY (average q0 = 1400 mg/kg) from wastewater is greater than that of SMX (average q0 = 650 mg/kg).

Table 1.

Best-fit parameters of six SMX and SPY breakthorugh models at different conditions.

| Model | SMX | SPY | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x (g) | v (mL/min) |

Kth (mL/mg/min) |

q0 (mg/kg) |

R2 | RMSE | x (g) | v (mL/min) |

Kth (mL/mg/min) |

q0 (mg/kg) |

R2 | RMSE | |

| Thomas | 0.250 | 1.000 | 0.020 | 735.431 | 0.967 | 0.074 | 0.250 | 1.000 | 0.006 | 1643.516 | 0.957 | 0.077 |

| 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.006 | 788.545 | 0.893 | 0.098 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.003 | 1718.489 | 0.933 | 0.083 | |

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.002 | 858.180 | 0.879 | 0.104 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 1503.275 | 0.888 | 0.106 | |

| 1.000 | 2.000 | 0.007 | 619.709 | 0.907 | 0.093 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 0.003 | 1712.626 | 0.902 | 0.107 | |

| 1.000 | 4.000 | 0.019 | 564.398 | 0.951 | 0.076 | 1.000 | 4.000 | 0.006 | 1337.017 | 0.915 | 0.101 | |

| x (g) | v (mL/min) |

KYN (L/min) | τ (min) | R2 | RMSE | x (g) | v (mL/min) |

KYN (L/min) | τ (min) | R2 | RMSE | |

| Yoon-Nelson | 0.250 | 1.000 | 0.202 | 18.169 | 0.967 | 0.074 | 0.250 | 1.000 | 0.061 | 40.555 | 0.957 | 0.077 |

| 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.058 | 38.921 | 0.893 | 0.098 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.028 | 84.822 | 0.933 | 0.083 | |

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.025 | 84.717 | 0.879 | 0.104 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.015 | 148.398 | 0.888 | 0.106 | |

| 1.000 | 2.000 | 0.070 | 30.588 | 0.907 | 0.093 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 0.028 | 84.532 | 0.902 | 0.107 | |

| 1.000 | 4.000 | 0.190 | 13.929 | 0.951 | 0.076 | 1.000 | 4.000 | 0.063 | 32.996 | 0.915 | 0.101 | |

| Z (cm) | F (cm/min) |

KAB (mL/mg/min) |

N0 (mg/L) |

R2 | RMSE | Z (cm) | F (cm/min) |

KAB (mL/mg/min) |

N0 (mg/L) |

R2 | RMSE | |

| Adam-Bohart | 0.255 | 0.497 | 0.020 | 358.976 | 0.967 | 0.074 | 0.255 | 0.497 | 0.006 | 802.228 | 0.957 | 0.077 |

| 0.509 | 0.497 | 0.006 | 384.902 | 0.893 | 0.098 | 0.509 | 0.497 | 0.003 | 838.823 | 0.933 | 0.083 | |

| 1.019 | 0.497 | 0.002 | 418.892 | 0.879 | 0.104 | 1.019 | 0.497 | 0.001 | 733.774 | 0.888 | 0.106 | |

| 1.019 | 0.995 | 0.007 | 302.490 | 0.907 | 0.093 | 1.019 | 0.995 | 0.003 | 835.961 | 0.902 | 0.107 | |

| 1.019 | 1.989 | 0.019 | 275.492 | 0.951 | 0.076 | 1.019 | 1.989 | 0.006 | 652.620 | 0.915 | 0.101 | |

| x (g) | v (mL/min) |

A | r | R2 | RMSE | x (g) | v (mL/min) |

A | r | R2 | RMSE | |

| Clark | 0.250 | 1.000 | 2.576E+09 | 0.948 | 0.954 | 0.086 | 0.250 | 1.000 | 143.961 | 0.091 | 0.941 | 0.090 |

| 0.500 | 1.000 | 5.832E+04 | 0.157 | 0.841 | 0.120 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 95.078 | 0.039 | 0.911 | 0.096 | |

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 2.7E+04 | 0.065 | 0.806 | 0.132 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 74.394 | 0.021 | 0.859 | 0.119 | |

| 1.000 | 2.000 | 3.043E+04 | 0.183 | 0.850 | 0.118 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 122.342 | 0.043 | 0.880 | 0.118 | |

| 1.000 | 4.000 | 7.134E+05 | 0.628 | 0.927 | 0.093 | 1.000 | 4.000 | 69.475 | 0.090 | 0.898 | 0.111 | |

| x (g) | v (mL/min) |

q0 (mg/kg) | a | R2 | RMSE | x (g) | v (mL/min) |

q0 (mg/kg) | a | R2 | RMSE | |

| Yan | 0.250 | 1.000 | 697.236 | 2.401 | 0.984 | 0.050 | 0.250 | 1.000 | 1423.690 | 1.936 | 0.994 | 0.029 |

| 0.500 | 1.000 | 692.305 | 1.531 | 0.961 | 0.059 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 1554.017 | 2.010 | 0.988 | 0.035 | |

| 1.000 | 1.000 | 757.009 | 1.672 | 0.968 | 0.053 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1330.793 | 1.674 | 0.981 | 0.044 | |

| 1.000 | 2.000 | 545.575 | 1.649 | 0.977 | 0.046 | 1.000 | 2.000 | 1555.511 | 1.686 | 0.983 | 0.044 | |

| 1.000 | 4.000 | 535.351 | 1.835 | 0.989 | 0.037 | 1.000 | 4.000 | 1094.266 | 1.420 | 0.987 | 0.040 | |

| Relation | C/C0 | k (L/mg/min) | N0 (mg/L) |

R2 | - | Relation | C/C0 | k (L/mg/min) | N0 (mg/L) |

R2 | - | |

| BDST | Dosage (F=0.497 cm/min) | 0.030 | 0.043 | 179.049 | 1.000 | - | Dosage (F=0.497 cm/min) | 0.030 | 0.063 | 240.175 | 0.990 | - |

| Dosage (F=0.497 cm/min) | 0.200 | 0.277 | 188.996 | 0.992 | - | Dosage (F=0.497 cm/min) | 0.200 | 0.277 | 396.445 | 0.989 | - | |

| Flow rate (h=1.019 cm) | 0.030 | 0.049 | 166.547 | 0.962 | - | Flow rate (h=1.019 cm) | 0.030 | 0.041 | 251.341 | 0.999 | - | |

| Flow rate (h=1.019 cm) | 0.200 | 0.022 | 221.506 | 0.984 | - | Flow rate (h=1.019 cm) | 0.200 | 0.015 | 454.789 | 0.999 | - | |

Notes: Explanation of parameters can be found in the Support Information.

The BDST model was applied to investigate the bed depth impact on SMX and SPY removal from wastewater by Al-BB-600 in fixed bed columns. As shown in Fig. 5, both BT points (C/C0=0.03 and 0.20) showed a strong linear relationship (R2 >0.99) between the dosage (bed depth) and service time for both SMX and SPY, respectively (Table 1). For both sulfonamides, the dynamic adsorption capacities N0 (mg/L) produced from the BDST model increased with the increasing C/C0. This may be ascribed to the fact that more active sites on biochar were occupied by sulfonamides at higher C/C0 values, causing the improvement of adsorption capacity (Sun et al., 2014a). Again, the removal capacity of Al-BB-600 for SPY was greater than that for SMX under the same column conditions according to the value of N0 (Table 1). Overall, these findings indicate that, for biochar-packed fixed bed column systems, the BDST model can guide the operation of SMX and SPY treatment in wastewater on a large scale.

Figure 5.

BDST model plots relating the bed depth (h) and service time (t) for (a) SMX, and (b) SPY (v = 1 mL/min and C0 = 10 mg/L).

3.4.2. Impact of flow rate

Different flow velocity was applied (1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 mL/min) to the Al modified biochar (1g) packed column for SMX and SPY removal (C0=10 mg/L) from wastewater. Predictably, the column performed better at a lower flow rate, with flow rate of 1 mL/min showing the longest BT time of 28 and 42 min for SMX and SPY, respectively (Fig. 6). At the fastest flow rate (4.0 mL/min), the BT time decreased to 3.4 and 4 min for SMX and SPY, respectively. This insufficient sulfonamide removal can be attributed to the limited exposure of sulfonamides to Al-BB-600 at a high flow rate.

Figure 6.

BT performance of (a) SMX, and (b) SPY in fixed bed columns packed with Al-BB-600 under different flow rates (x = 1 g and C0 = 10 mg/L) in wastewater. Data (symbols) were simulated with models (lines). The dashed line is the simulations of Thomas, Adams-Bohart (A-B) and Yoon-Nelson (Y-N) models (same results).

Again, the Yan model best simulated the column data (Table 1, average R2 = 0.98 and 0.99 for SMX and SPY, respectively) with the lowest RMSE (0.04-0.05 for SMX and ~0.04 for SPY). With increasing flow rate, the dynamic adsorption capacity, q0, predicted from Yan model decreased gradually for both SMX and SPY, except for one datapoint (SPY at v = 2 mL/min), which can be ascribed to the decreasing residence time of wastewater and the limited contact time as mentioned above. Similarly, the sorption performance of SPY was better than that of SMX in fixed bed column in terms of the BT time and predicted q0 (mean of 610 mg/kg for SMX and 1330 mg/kg for SPY).

The BDST model still showed a strong linear relationship between the reverse of linear flow rate and service time (Fig. 7, R2> 0.96 for SMX and > 0.99 for SPY). For both sulfonamides, the predicted N0 (mg/L) also increased with increasing C/C0 (Table 1). Again, the predicted N0 of SPY was greater than that of SMX under the same conditions. Theoretically, the linear equation of the BDST model at the half of BT point (C/C0=0.50) should pass through the origin (t=0). However, for sorption of SMX and SPY onto Al-BB-600 in wastewater, the linear plot (C/C0=0.50) had positive y-axis intercepts under all experimental conditions (Fig. S5), suggesting that there was more than one rate-liming factor (e.g., mass transfer at the solid surface and diffusion) involved (Sun et al., 2014a; de Franco et al., 2017). The above results suggest that flow rate is an important consideration in successful application of Al-modified biochar as a fixed-bed column packing material to remove sulfonamides from wastewater.

Figure 7.

BDST model plots relating the reverse of linear flow velocity (1/F) and service time (t) for (a) SMX, and (b) SPY (x = 1 g and C0 = 10 mg/L).

4. Conclusions

Batch sorption experiments demonstrated that Al-modified biochar (Al-BB-600) effectively removed SMX and SPY from wastewater. The main mechanisms involved in sorption of SMX and SPY, as suggested by chemical characterization and kinetic and adsorption isotherm modeling, were likely hydrophobic interaction, π-π EDA interaction and electrostatic interactions. Fixed bed column experiments revealed that maximal removal for sulfonamides occurred at the Al-BB-600 dosages of 1000 mg with a flow rates of 1 mL/min. Among all BT models, the Yan model best described the experimental data for both sulfonamides. Further the BDST model showed a strong linear relationship between service time and the amount of Al-BB-600, demonstrating the fixed bed column can be applied for a continuous wastewater flow system. The findings of this work indicate that Al-modified biochar may be a reliable sorbent for removing sulfonamide antibiotics from wastewater and can be applied to the real-world water treatment application. Nevertheless, further investigations on the recyclability, regeneration potential, life cycle assessment, cost analysis, and pilot scale evaluation of the sorbent for treating antibiotics in wastewater are warranted to promote its uses in large-scale applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the USDA Grant 2020-38821-31081. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

References

- Ahmad M, Rajapaksha AU, Lim JE, Zhang M, Bolan N, Mohan D, Vithanage M, Lee SS, Ok YS, 2014. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: a review. Chemosphere 99, 19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai S, Zhu S, Jin C, Sun Z, Wang L, Wen Q, Ma F, 2021. Sorption mechanisms of antibiotic sulfamethazine (SMT) on magnetite-coated biochar: pH-dependence and redox transformation. Chemosphere 268, 128805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal RC, Goyal M, 2005. Activated carbon adsorption. CRC press. [Google Scholar]

- Calero M, Hernáinz F, Blázquez G, Tenorio G, Martín-Lara M, 2009. Study of Cr (III) biosorption in a fixed-bed column. Journal of Hazardous Materials 171, 886–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Zhou D, Zhu L, 2008. Transitional adsorption and partition of nonpolar and polar aromatic contaminants by biochars of pine needles with different pyrolytic temperatures. Environmental science & technology 42, 5137–5143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng N, Wang B, Wu P, Lee X, Xing Y, Chen M, Gao B, 2021. Adsorption of emerging contaminants from water and wastewater by modified biochar: A review. Environ Pollut, 116448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet-Kastylevsky G, Vial T, Descotes J, 2002. Allergic adverse reactions to sulfonamides. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 2, 16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu KH, 2020. Breakthrough curve analysis by simplistic models of fixed bed adsorption: In defense of the century-old Bohart-Adams model. Chemical Engineering Journal 380, 122513. [Google Scholar]

- Connor EE, 1998. Sulfonamide antibiotics. Primary care update for ob/gyns 5, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney D, 1999. Adsorption design for wastewater treatment, CRC Pres. INC., Boca Raton, Florida, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Darweesh TM, Ahmed MJ, 2017. Batch and fixed bed adsorption of levofloxacin on granular activated carbon from date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) stones by KOH chemical activation. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology 50, 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Franco MAE, de Carvalho CB, Bonetto MM, de Pelegrini Soares R, Féris LA, 2017. Removal of amoxicillin from water by adsorption onto activated carbon in batch process and fixed bed column: kinetics, isotherms, experimental design and breakthrough curves modelling. Journal of Cleaner Production 161, 947–956. [Google Scholar]

- Gaines GL Jr, Thomas HC, 1953. Adsorption studies on clay minerals. II. A formulation of the thermodynamics of exchange adsorption. The Journal of Chemical Physics 21, 714–718. [Google Scholar]

- Galán MJG, Díaz-Cruz MS, Barceló D, 2012. Removal of sulfonamide antibiotics upon conventional activated sludge and advanced membrane bioreactor treatment. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 404, 1505–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Zhang Y, Gong X, Song Z, Guo Z, 2018. Removal mechanism of di-n-butyl phthalate and oxytetracycline from aqueous solutions by nano-manganese dioxide modified biochar. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25, 7796–7807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P, Munir M, Xagoraraki I, 2012. Correlation of tetracycline and sulfonamide antibiotics with corresponding resistance genes and resistant bacteria in a conventional municipal wastewater treatment plant. Science of the total environment 421, 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng X, Lv S, Yang J, Cui S, Zhao Z, 2021. Carboxyl-functionalized biochar derived from walnut shells with enhanced aqueous adsorption of sulfonamide antibiotics. Journal of Environmental Management 280, 111749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Chen Z, Lu C, Guo J, Li H, Song Y, Han Y, Hou Y, 2020. Effect and ameliorative mechanisms of polyoxometalates on the denitrification under sulfonamide antibiotics stress. Bioresource technology 305, 123073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J, Yoon Y, Lee G, Kim Y, Han J, Park CM, 2019. Enhanced adsorption of bisphenol A and sulfamethoxazole by a novel magnetic CuZnFe2O4–biochar composite. Bioresource technology 281, 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Jiang L, Zhang T, Jin L, Han Q, Zhang D, Lin K, Cui C, 2018. Occurrence and removal of sulfonamide antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in conventional and advanced drinking water treatment processes. Journal of hazardous materials 360, 364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Wang X, Zhang C, Zeng G, Peng Z, Zhou J, Cheng M, Wang R, Hu Z, Qin X, 2017. Sorptive removal of ionizable antibiotic sulfamethazine from aqueous solution by graphene oxide-coated biochar nanocomposites: influencing factors and mechanism. Chemosphere 186, 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Zimmerman AR, Chen H, Gao B, 2020. Ball milled biochar effectively removes sulfamethoxazole and sulfapyridine antibiotics from water and wastewater. Environmental Pollution 258, 113809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins R, 1973. New method simplifies design of activated-carbon systems. Chemical Engineering 80, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Inyang M, Gao B, Zimmerman A, Zhou Y, Cao X, 2015. Sorption and cosorption of lead and sulfapyridine on carbon nanotube-modified biochars. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 22, 1868–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang HM, Kan E, 2019. Engineered biochar from agricultural waste for removal of tetracycline in water. Bioresource technology 284, 437–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang HM, Yoo S, Park S, Kan E, 2018. Engineered biochar from pine wood: Characterization and potential application for removal of sulfamethoxazole in water. Environmental Engineering Research 24. [Google Scholar]

- Jeppu GP, Clement TP, 2012. A modified Langmuir-Freundlich isotherm model for simulating pH-dependent adsorption effects. Journal of contaminant hydrology 129, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzyk-Hordern B, 2004. Chemistry of alumina, reactions in aqueous solution and its application in water treatment. Advances in colloid and interface science 110, 19–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan NA, Ahmed S, Farooqi IH, Ali I, Vambol V, Changani F, Yousefi M, Vambol S, Khan SU, Khan AH, 2020. Occurrence, sources and conventional treatment techniques for various antibiotics present in hospital wastewaters: a critical review. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 129, 115921. [Google Scholar]

- Kong X, Liu Y, Pi J, Li W, Liao Q, Shang J, 2017. Low-cost magnetic herbal biochar: characterization and application for antibiotic removal. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 24, 6679–6687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmulski M, 2001. Evaluation of points of zero charge of aluminum oxide reported in the literature. Pr. Nauk. Inst. Gor. Politech. Wroc 95, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmulski M, 2018. The pH dependent surface charging and points of zero charge. VII. Update. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 251, 115–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasucka P, Pan B, Ok YS, Mohan D, Sarkar B, Oleszczuk P, 2021. Engineered biochar–A sustainable solution for the removal of antibiotics from water. Chemical Engineering Journal 405, 126926. [Google Scholar]

- Leng L, Wei L, Xiong Q, Xu S, Li W, Lv S, Lu Q, Wan L, Wen Z, Zhou W, 2020. Use of microalgae based technology for the removal of antibiotics from wastewater: A review. Chemosphere 238, 124680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Yu W, Guo L, Wang Y, Zhao S, Zhou L, Jiang X, 2021. Sorption of sulfamethoxazole on inorganic acid solution-etched biochar derived from alfalfa. Materials 14, 1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Wang JJ, Zhou B, Awasthi MK, Ali A, Zhang Z, Gaston LA, Lahori AH, Mahar A, 2016. Enhancing phosphate adsorption by Mg/Al layered double hydroxide functionalized biochar with different Mg/Al ratios. Science of the Total Environment 559, 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Wang Z, Zhao X, Li X, Xie X, 2018. Magnetic biochar-based manganese oxide composite for enhanced fluoroquinolone antibiotic removal from water. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25, 31136–31148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian F, Sun B, Chen X, Zhu L, Liu Z, Xing B, 2015. Effect of humic acid (HA) on sulfonamide sorption by biochars. Environmental Pollution 204, 306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Xu W.-h., Liu Y.-g., Tan X.-f., Zeng G.-m., Li X, Liang J, Zhou Z, Yan Z.-l., Cai X.-x., 2017. Facile synthesis of Cu (II) impregnated biochar with enhanced adsorption activity for the removal of doxycycline hydrochloride from water. Science of the Total Environment 592, 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Guo X, Liu Y, Lu S, Xi B, Zhang J, Wang Z, Bi B, 2019. A review on removing antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes from wastewater by constructed wetlands: Performance and microbial response. Environmental Pollution 254, 112996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Liu Y, Wei J, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Xing L, Li J, 2021. Enhanced removal of doxycycline by iron modified sludge derived hydrother-mal biochar: adsorption properties and the effect of Cu (II) coexisting. DESALINATION AND WATER TREATMENT 229, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Motsi T, Rowson N, Simmons M, 2009. Adsorption of heavy metals from acid mine drainage by natural zeolite. International journal of mineral processing 92, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nazari G, Abolghasemi H, Esmaieli M, Pouya ES, 2016. Aqueous phase adsorption of cephalexin by walnut shell-based activated carbon: A fixed-bed column study. Applied Surface Science 375, 144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Paumelle M, Donnadieu F, Joly M, Besse-Hoggan P, Artigas J, 2021. Effects of sulfonamide antibiotics on aquatic microbial community composition and functions. Environment International 146, 106198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Hu F, Zhang T, Qiu F, Dai H, 2018. Amine-functionalized magnetic bamboo-based activated carbon adsorptive removal of ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin: A batch and fixed-bed column study. Bioresource technology 249, 924–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senthilkumar R, Vijayaraghavan K, Thilakavathi M, Iyer P, Velan M, 2006. Seaweeds for the remediation of wastewaters contaminated with zinc (II) ions. Journal of hazardous materials 136, 791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao B, Dong D, Wu Y, Hu J, Meng J, Tu X, Xu S, 2005. Simultaneous determination of 17 sulfonamide residues in porcine meat, kidney and liver by solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Analytica Chimica Acta 546, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Zou W, Bian Y, Su F, Han R, 2011. Adsorption characteristics of methylene blue by peanut husk in batch and column modes. Desalination 265, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Imai T, Sekine M, Higuchi T, Yamamoto K, Kanno A, Nakazono S, 2014a. Adsorption of phosphate using calcined Mg3–Fe layered double hydroxides in a fixed-bed column study. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 20, 3623–3630. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Gao B, Yao Y, Fang J, Zhang M, Zhou Y, Chen H, Yang L, 2014b. Effects of feedstock type, production method, and pyrolysis temperature on biochar and hydrochar properties. Chemical Engineering Journal 240, 574–578. [Google Scholar]

- Taherymoosavi S, Verheyen V, Munroe P, Joseph S, Reynolds A, 2017. Characterization of organic compounds in biochars derived from municipal solid waste. Waste Management 67, 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Li Y, Zhan L, Wu D, Zhang S, Pang R, Xie B, 2022. Removal of emerging contaminants (bisphenol A and antibiotics) from kitchen wastewater by alkali-modified biochar. Science of The Total Environment 805, 150158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S-Q, Wang L, Liu Y-L, Ma J, 2020. Degradation of organic pollutants by ferrate/biochar: Enhanced formation of strong intermediate oxidative iron species. Water Research 183, 116054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Gao B, Morales VL, Chen H, Wang Y, Li H, 2013. Removal of sulfamethoxazole and sulfapyridine by carbon nanotubes in fixed-bed columns. Chemosphere 90, 2597–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar-Navarro E, Baena-Nogueras RM, Paniw M, Perales JA, Lara-Martín PA, 2018. Removal of pharmaceuticals in urban wastewater: High rate algae pond (HRAP) based technologies as an alternative to activated sludge based processes. Water research 139, 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan S, Wang S, Li Y, Gao B, 2017. Functionalizing biochar with Mg–Al and Mg–Fe layered double hydroxides for removal of phosphate from aqueous solutions. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 47, 246–253. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang S, 2016. Removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) from wastewater: a review. Journal of environmental management 182, 620–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Yang X, Xu Z, Hu W, Zhou Y, Wan Z, Yang Y, Wei Y, Yang J, Tsang DC, 2020. Fabrication of sustainable manganese ferrite modified biochar from vinasse for enhanced adsorption of fluoroquinolone antibiotics: effects and mechanisms. Science of The Total Environment 709, 136079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie M, Chen W, Xu Z, Zheng S, Zhu D, 2014. Adsorption of sulfonamides to demineralized pine wood biochars prepared under different thermochemical conditions. Environmental Pollution 186, 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan G, Viraraghavan T, Chen M, 2001. A new model for heavy metal removal in a biosorption column. Adsorption Science & Technology 19, 25–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Xue Y, Long L, Zeng Y, Hu X, 2018. Adsorptive removal of As (V) by crawfish shell biochar: batch and column tests. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25, 34674–34683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Song G, Lim W, 2020. A review of the toxicity in fish exposed to antibiotics. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 237, 108840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Wang X, Luo W, Sun J, Xu Q, Chen F, Zhao J, Wang S, Yao F, Wang D, 2018. Effectiveness and mechanisms of phosphate adsorption on iron-modified biochars derived from waste activated sludge. Bioresource Technology 247, 537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Wang D, Sun Z, Tang H, 2007. Adsorption of phosphate at the aluminum (hydr) oxides–water interface: Role of the surface acid–base properties. Colloids and Surfaces a: Physicochemical and engineering aspects 297, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Gao B, Chen H, Jiang L, Inyang M, Zimmerman AR, Cao X, Yang L, Xue Y, Li H, 2012. Adsorption of sulfamethoxazole on biochar and its impact on reclaimed water irrigation. J Hazard Mater 209, 408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Gao B, Inyang M, Zimmerman AR, Cao X, Pullammanappallil P, Yang L, 2011. Removal of phosphate from aqueous solution by biochar derived from anaerobically digested sugar beet tailings. Journal of hazardous materials 190, 501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Zhang Y, Gao B, Chen R, Wu F, 2018. Removal of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) and sulfapyridine (SPY) from aqueous solutions by biochars derived from anaerobically digested bagasse. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 25, 25659–25667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi S, Sun Y, Hu X, Xu H, Gao B, Wu J, 2018. Porous nano-cerium oxide wood chip biochar composites for aqueous levofloxacin removal and sorption mechanism insights. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25, 25629–25637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Gao B, 2013. Removal of arsenic, methylene blue, and phosphate by biochar/AlOOH nanocomposite. Chemical engineering journal 226, 286–292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Dong L, Yan H, Li H, Jiang Z, Kan X, Yang H, Li A, Cheng R, 2011. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions by straw based adsorbent in a fixed-bed column. Chemical engineering journal 173, 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Sun P, Wei K, Huang X, Zhang X, 2020a. Enhanced H2O2 activation and sulfamethoxazole degradation by Fe-impregnated biochar. Chemical Engineering Journal 385, 123921. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang Y, Ngo HH, Guo W, Wen H, Zhang D, Li C, Qi L, 2020b. Characterization and sulfonamide antibiotics adsorption capacity of spent coffee grounds based biochar and hydrochar. Science of The Total Environment 716, 137015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Yi S, Dong S, Xu H, Sun Y, Hu X, 2018. Removal of Levofloxacin from aqueous solution by Magnesium-impregnated Biochar: batch and column experiments. Chemical Speciation & Bioavailability 30, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Wang B, Wester AE, Chen J, He F, Chen H, Gao B, 2019. Reclaiming Phosphorus from Secondary Treated Municipal Wastewater with Engineered Biochar. Chemical Engineering Journal 362, 460–468. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Luo J, Liu C, Chu L, Ma J, Tang Y, Zeng Z, Luo S, 2016. A highly efficient polyampholyte hydrogel sorbent based fixed-bed process for heavy metal removal in actual industrial effluent. Water research 89, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Liu X, Xiang Y, Wang P, Zhang J, Zhang F, Wei J, Luo L, Lei M, Tang L, 2017. Modification of biochar derived from sawdust and its application in removal of tetracycline and copper from aqueous solution: adsorption mechanism and modelling. Bioresource technology 245, 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.